Abstract

Background:

Palliative patients frequently express a desire to die. Health professionals report uncertainty regarding potential risks of addressing it.

Aim:

We aim to evaluate effects of desire to die-conversations on palliative patients.

Design:

Within a prospective mixed-methods cohort study, we trained health professionals in dealing with desire to die. Afterwards, they held conversations about it with patients. Effects on depressiveness, hopelessness, wish to hasten death, death anxiety, patient-health professional-relationship, and will to live were evaluated at baseline (t0), 1 (t1), and 6 weeks afterwards (t2). Results were analyzed descriptively.

Setting/participants:

From April 2018 to March 2020, 43 health professionals asked 173 patients from all stationary and ambulatory palliative care settings (within 80 km radius) for participation. Complete assessments were obtained from n = 85 (t0), n = 64 (t1), and n = 46 (t2).

Results:

At t1, patients scored significantly lower on depressiveness (med = 8, M = 8.1, SD = 5.4) than at t0 (med = 9.5, M = 10.5, SD = 5.8) with Z = −3.220, p = 0.001 and Cohen’s d = 0.42. This was due to medium-severely depressed patients: At t1, their depressiveness scores decreased significantly (med = 9, M = 9.8; SD = 5.1) compared to t0 (med = 14, M = 15.2; SD = 3.9) with Z = −3.730, p ⩽ 0.000 and Cohen’s d = 1.2, but others’ did not. All other outcomes showed positive descriptive trends.

Conclusions:

Desire to die-conversations through trained health professionals do not harm palliative patients. Results cautiously suggest temporary improvement.

Keywords: Cohort studies, palliative care, suicidal ideation, communication, desire to die**

What is already known about the topic?

Patients in palliative care frequently express a desire to die that rarely leads to a request for medical aid in dying.

Fearing to cause harm, health professionals report uncertainty regarding proactively approaching the topic with their patients.

Suicidology research suggests that there is no iatrogenic risk in asking about suicidality, but it remains unclear whether this analogy holds for non-psychiatric palliative patients with or without a desire to die.

What this paper adds?

Independent of age, gender, diagnoses, and current desire to die, open conversations about desire to die through trained health professionals do not harm palliative patients.

Desire to die conversations might lead to an at least temporary improvement in patients with medium to severe depression.

Implications for practice, theory, or policy?

Health professionals can feel encouraged to promote an open and respectful atmosphere of conversation about existential issues at the end of life including possible desire to die.

Introduction

Burden from serious health-related suffering in life-limiting illnesses is estimated to double by 2060, 1 calling for an expansion of palliative care that provides relief for all affected patients independent from diagnosis. 2 In these patients, desire to die is a common reaction to physical, psychological or spiritual suffering. 3 Depending on the study, 12%–45% of patients receiving palliative care experience a temporary and up to 10%–18% report a stable and lasting desire to die.4,5 Desire to die is not to be equated with suicidal tendencies, seeking assistance in suicide or by institutions providing euthanasia, as these are only some of many possible manifestations. 3 Desire to die can be ambivalent and dynamic: we conceptualize its different types along a continuum of increasing suicidal pressure, with acceptance of death without a wish to hasten it on the one end and acute suicidality on the other. 3 Therefore, desire to die is a broad phenomenon, encompassing suicide but not limited to it. Desire to die can be associated with negative health outcomes; with depression and hopelessness being the strongest predictors of a wish to hasten death in a sample of metastatic cancer patients. 6 Other risk factors include physical symptom burden, death anxiety, and social isolation, while strong and reliable relationships both to loved ones and health professionals can be protective. 6 These factors do not necessarily constitute psychiatric diagnoses and desire to die is not limited to psychiatric patients, although psychiatric diagnoses are often correlated with it. 5 Desire to die can also be a way of coping with a serious life-threatening disease and approaching death.

Health professionals are regularly confronted with palliative patients’ desire to die and report uncertainty regarding an adequate response. 7 Conversations about it are often avoided due to perceived taboos surrounding the topic, for example, fear of causing or increasing suicidality. 14 Moreover, starting conversations about medical assistance in dying is forbidden in some jurisdictions, such as Victoria (Australia)—a heavily criticized regulation. 8 This contrasts a societal shift toward demands for a self-determined end of life: the last decades saw a trend toward more liberal regulations regarding medical aid in dying worldwide, for example, in Canada, USA, The Netherlands, Belgium, Swiss, or Germany. 9 With these changes, the numbers of requests for medical aid in dying are rising as well. 9 They might also lead to more patients expressing a desire to die openly and health professionals will have to lead conversations on such potential desires.

Suicidology studies repeatedly confirm no heightened iatrogenic risk from asking patients about suicidality, 10 but alleviated burden and a stronger relationship between health professionals and patients. 3 A study with oncological patients suggests applicability to the wish to hasten death: when assessed through a short, semi-structured interview on hospital admittance, 94.8% of the 193 interviewed patients reported being asked about a wish to hasten death as not upsetting. 11 Despite these promising results, the effects of open, proactive conversation about desire to die as a broader phenomenon then the wish to hasten death has yet to be evaluated for patient-relevant-outcomes in palliative care.

We aimed to address this issue by developing a clinical approach for dealing with desire to die and train health professionals from all palliative care settings in its use.12,13 By evaluating the effect of desire to die-conversations by health professionals on patients of multiple diagnoses and in various care settings, we aimed to explore whether proactively addressing desire to die is harmful.

Methods

Procedure

This paper presents quantitative data collected within the third phase of a three-phase sequential mixed methods study. 12 Further results of the project have been published elsewhere.13,14

Within study phase 1, the clinical approach on dealing with desire to die was developed.12,13 Subsequently, in phase 2, health professionals from all palliative care settings within a radius of 80 km were invited to take part in multi-professional 2-day trainings. 15 The training curricula included sessions on theoretical background, functions and forms of desire to die, reflection of own attitudes as well as a practical communication training (role play), supported by the clinical approach. Details on development, structure and content of the training are reported elsewhere. 15 In phase 3 of the study, the trained health professionals were asked to recruit patients receiving palliative care from their personal practice. Upon initial interest in participation, the research team approached patients, provided them with information about the study and sought their written informed consent. “End-of-life-communication” was presented as the study topic and the term “desire to die” was avoided to minimize bias. During the entire process, measures were taken to cushion emerging patient distress or potential suicidality in the context of the evaluation procedure: the research team maintained close contact with recruiting health professionals and gave feedback (with patient consent) should patients exhibited intense emotional distress at a visit. Additionally, patients were encouraged to call at any time if they experienced distress caused by the evaluation. Internal clinical and psychiatric expertise was available for consultation in critical cases.

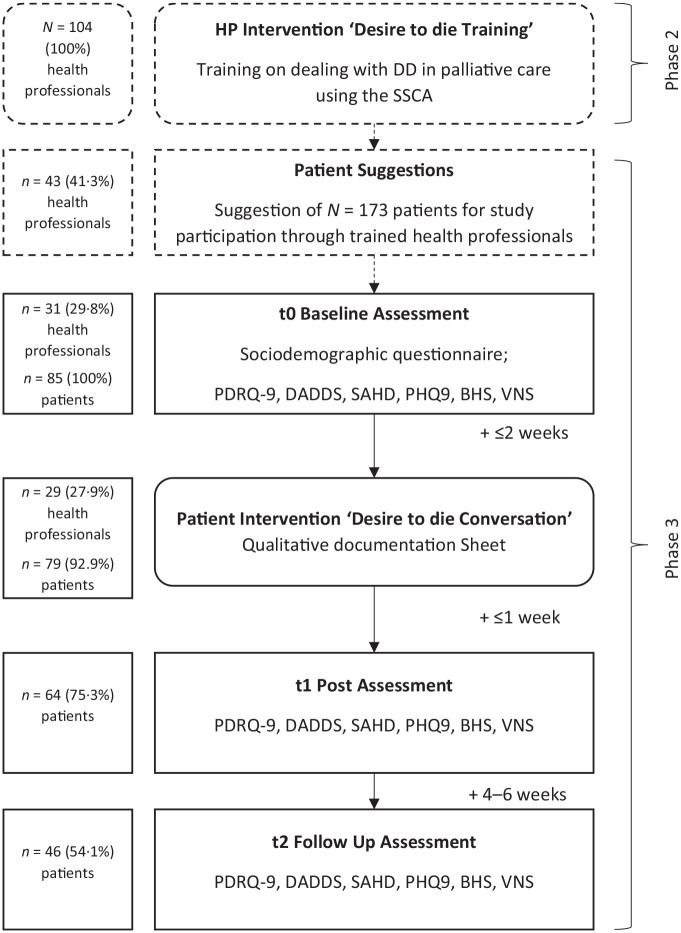

At baseline (t0), patients reported sociodemographic data and answered (validated) questionnaires (see section Material). After successful completion of baseline assessment, the study team informed the recruiting health professional who was then required to have a single desire to die-conversation with the patient within the next 2 weeks. This intervention was designed to be a semi-standardized, though open conversation adaptable to the health professionals’ style and circumstances. No pre-formulated phrases were provided, but desire to die had to be topic of the conversation. Health professionals filled out a documentation sheet of the conversation and sent it to the research team which then went on to perform two post-assessments at 1 (t1) and 6 weeks (t2) afterward. For procedure details, see Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Procedure and attrition flowchart.

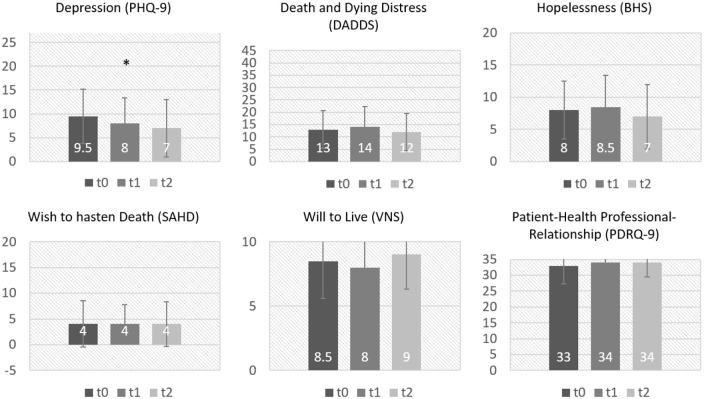

Figure 2.

Median and standard deviation of all main outcomes.

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS Statistics 25. 16 Research was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the University of Cologne (#17–265) and the study was registered in the German Clinical Trials Register (DRKS00012988; registration date: 27.9.2017). We followed the STROBE Reporting Guideline.

Sampling

We followed a convenience sampling strategy to encourage health professionals to consider as many patients as possible for a discussion about desire to die. Other reasons for the sampling strategy included that recruiting of large samples in palliative care settings is known to be difficult due to gate keeping by health professionals and patients’ fast deterioration of physical and mental health. 17 We instructed trained health professionals about inclusion criteria for recruiting patients and provided flyers with information about the study for approaching them. Inclusion criteria for patients were

(1) prognosis of death within 3–12 months (assessed by the “surprise question” 18 )

(2) adult (older than 18 years)

(3) patient informed consent

(4) cognitive ability to participate, according to health professionals estimation

(5) German language ability.

We aimed at recruiting patients of all ages, genders, ethnicities, types of medical diagnosis, and care settings to gather a heterogeneous sample.

Material

Assessment of patient relevant outcomes

Recent literature shows correlation of different aspects of experience in patients receiving palliative care with the development of a desire to die; these aspects served as our patient-relevant outcomes. To evaluate effects of a desire to die conversation on these outcomes, we used five validated questionnaires and one Visual Numerical Scale (VNS). For further details, see Table 1.

Table 1.

(Validated) questionnaires used for evaluation of desire to die conversation.

| Construct | Questionnaire | Psychometric properties | Structure |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient-Health Professional-Relationship | Patient Doctor Relationship Questionnaire (PDRQ-9)* | Good psychometric properties 19 | 9 items; 5-point Likert scale; Scores: 0–35 |

| Depression | Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9)* | Good psychometric properties, sensitivity for change, and is widely used in palliative care samples 20 | 9 Items; 4-Point Likert scale; Scores: 0–27 |

| Hopelessness | Beck Hopelessness Scale (BHS)* 21 | Validated in various subgroups of the German general population 22 | 20 Items; Dichotomous true- or false-answers Scores: 0–20 |

| Death and Dying Distress | Death and Dying Distress Scale (DADDS)* | Validated for patients with advanced cancer 23 | 20 Items; 5-Point Likert scale; Scores: 0–75 |

| Desire to die | Schedules of Attitudes Toward Hastened Death (SAHD-D)* | Validated in German samples of patients receiving specialized palliative care 24 | 20 Questions; Dichotomous yes- or no-answers Scores: 0–20 |

| Will to live | Visual Numerical Scale | / | Single-item Visual Numerical Scales (VNS); Scores: 0–10 |

Validated German Version.

As patients in advanced stages of disease are often unable to fill out questionnaires, we administered them in form of a standardized quantitative procedure: The researchers read the instructions and questions aloud to the patients, who gave their answers verbally.

Statistical analysis

Analysis focused on the change in patient-reported outcomes from t0 to t1 and t0 to t2, respectively. We analyzed data with the non-parametric Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney-Test with significance level of 5% for changes from t0 to t1 and t0 to t2. Additional explorative subgroup analyses by age, gender, diagnosis, existing desire to die and whether it was addressed proactively (by health professional) or reactively (by patient) followed. We used the same tests for exploratory subgroup analyses of the main outcomes and analyzed socio-demographic data descriptively. As reported in our study protocol, the intended sample size was N = 300 to detect even small within-group effects (Cohen’s d < 0.2 for the whole group and Cohen’s d < 0.5 for subgroups of n = 40). 12 All patients with a valid assessment at t0 (baseline), t1, and t2 (post-intervention) were included for analysis.

Results

Between April 2018 and March 2020, 42 health professionals suggested 173 patients for study participation, n = 85 of them attended baseline assessment. Reasons for non-participation were patient death or patient’s refusal, for example, due to other priorities in the last phase of life. Intended sample size was not met, yet power was found to be sufficient for detection of large effects. 12 For n = 79 of these patients, health professionals documented a desire to die-conversation. These conversations had a mean duration of 43 min (range: 1–120) and often ended in initiation of therapeutic measures (e.g. involving a psychologist) or patients’ preferred mode of care either at home or in an institution (e.g. a hospice). For the post-assessments, n = 64 and n = 46 patients completed t1 and t2, respectively. This yields an overall drop-out rate (from t0 to t2) of 73.4% which was due either to patient wish (31.4%), patient death (54.3%), deterioration in physical and/or mental health (8.6%) or unknown (5.7%).

Sample

Patients were 50 women and 35 men with a mean age of 69.1 years (SD = 12.5). According to recruiting health professionals, 22% of them had a DD. For detailed information on the patient sample, see Table 2.

Table 2.

Patient characteristics.

| Characteristic | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Diagnosis | |

| Oncological | 54 (63) |

| Neurological | 12 (14) |

| Geriatric/multimorbid | 7 (6) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) | 7 (8) |

| Other | 5 (6) |

| Mortality(upon study completion) | |

| Deceased | 45 (53) |

| Alive | 15 (18) |

| Not determinable | 25 (29) |

| Care setting | |

| Outpatient care at home | 30 (35) |

| Palliative care station | 16 (19) |

| Residential care | 16 (19) |

| Hospice | 11 (13) |

| Other | 12 (14) |

| Education | |

| Higher education | 12 (14) |

| Secondary school | 67 (82) |

| No finished education/no information provided | 6 (7) |

| Occupation before illness | |

| Yes | 47 (55) |

| No | 37 (43) |

| No information provided | 1 (2) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Born in Germany | |

| Yes | 78 (92) |

| No | 7 (8) |

| German native speaker | |

| Yes | 77 (91) |

| No | 2 (2) |

| No information provided | 6 (7) |

| Desire to die | |

| As judged by the HP during conversation | |

| Patient has a DD | 19 (22) |

| Patient has no DD | 60 (71) |

| No information provided | 6 (7) |

| Who addressed desire to die in conversation? | |

| Proactively addressed by HP | 60 (71) |

| Reactively addressed by patient | 18 (21) |

| No information provided | 7 (8) |

Patient-relevant outcomes

Data were not normally distributed according to Kolmogorov-Smirnov, so we evaluated differences in distributions using the two-tailed Wilcoxon signed-rank test (paired data) or Mann-Whitney U-test (unpaired data), respectively. At t1 after the conversation, patients reported significantly lower depression scores (med = 8, M = 8.1, SD = 5.4) than at baseline (med = 9.5, M = 10.5, SD = 5.8) with Z = −3.220, p = 0.001, and Cohen’s d = 0.42. Lower scores for death and dying distress, hopelessness and desire to die were not significant, as were higher scores for will to live and patient-doctor-relationship (see Figure 2). There was no deterioration in any of the outcomes measured.

Exploratory subgroup analyses

Exploratory subgroup analyses revealed no significant effects of age (⩾65 vs <65), gender (female vs male), the two largest groups of diagnoses (oncological vs neurological) and desire to die (present vs absent). Additionally, we conducted a more thorough exploration of the changes in depression from t0 to t1 and t0 to t2. To strengthen the clinical relevance of our findings, we split the sample along a known cut-off into two groups with either a high (⩾10; “medium-severe depression”) or low (<10; “mild-moderate depression”) expression. 25 Looking at changes in depression median, scores decreased significantly for patients with medium-severe depression from t0 (med = 14, M = 15.2; SD = 3.9) to t1 (med = 9, M = 9.8; SD = 5.1) with Z = −3.730, p ⩽ 0.000 and Cohen’s d = 1.2. It is noteworthy to add that in this group, decrease in depression narrowly missed significance at t2 with p = 0.051, despite small group sizes. There was no significant decrease in depression for the mild—moderately depressed.

Discussion

Main findings

Desire to die is frequent in patients receiving palliative care, yet is insufficiently addressed by health professionals, often due to fear of an iatrogenic risk for their patients. 7 Within the scope of our sample, our study nevertheless provides first data to empirically support that proactively addressing desire to die does not harm. Over a period of up to 6 weeks after a conversation, patients reported no significant changes, but also no deterioration on any of the examined outcomes. Yet, trends are pointing toward potentially relieving effects of a desire to die-conversation in patient depressiveness.

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

Instead of one question about distress, 11 we assessed the effects of desire to die-conversations through validated questionnaires of patient-reported outcomes: Depression was the only outcome with statistically significant improvement for the whole sample. As depression is a major influencing factor for developing a wish to hasten death, 6 reducing it through conversation might act therapeutically significant. This effect only holds for patients with medium-severe depression, suggesting either potential floor effects or a specific benefit for only patients with highly burdensome depression. However, data on other depression treatments patients might have received at the time of study was not available, allowing a chance of bias in individual cases.

No other change in outcomes reached significance, yet some descriptive patterns emerged. The expression of wish to hasten death and will to live remained stable, suggesting that these phenomena occur simultaneously. It also underlines that reducing a wish to hasten death is not necessarily needed to reduce patient suffering in the form of depression. If a desire to die merely suggests an acceptance of death, its reduction might not even be desirable: a desire to die can serve as a positive means to remain in control of one’s life. 3 Hopelessness showed descriptive trends for improvement as well. In our sample of patients near death, certain BHS-items on hopes for the future were deemed inappropriate. Therefore, the BHS had the highest number of missing values. This is in line with known criticisms, so future studies might benefit from using the BHS-short. 26 Over all assessment points, our patient sample scored relatively low on death and dying distress, indicating a floor effect. Together with the ceiling effect behind the stable high of therapeutic alliance, this might indicate a selection bias. It might also imply that health professionals consider a good patient-relationship as prerequisite to a desire to die-conversation. 7

The latter indicates gate-keeping: despite advice to ask all palliative patients for participation, health professionals might have felt reluctant to ask patients they did not deem as stable. Therefore, conclusions from our data about patients with a worse mental health status that usually report desire to die more frequently have to be interpreted with caution. 5

Interpretation of our results at t2 and the results from our subgroup analyses are limited by small sample size, caused by drop-out, a problem frequent in palliative care research. 17 Especially interpretation of effectiveness in our subgroup analyses may be further compromised, since direction of changes in group distribution of mild-moderate and medium-severe depressed patients remained statistically inconclusive.

Strengths and weaknesses in relation to other studies

Research in the adjacent fields of psychiatry and suicidology established that asking about suicidal ideation and suicidality does not cause iatrogenic risk for patients. 10 These results applied to desire to die in palliative patients only in analogy, as patients receiving palliative care are in the unique situation of suffering from a life-limiting disease. Our results therefore suggest that there is no specific iatrogenic risk of proactively addressing desire to die for palliative patients in our sample. In palliative care research, a recent study about the clinical evaluation of the wish to hasten death in oncology patients proposed similar results. 11 Our findings compliment, but exceed those in two relevant aspects:

Our results are generalizable for the whole desire to die-phenomenon, of which the wish to hasten death is only one possible expression. This is relevant since desire to die expressing the acceptance of death without the wish to hasten it or simply a tiredness of life is much more common than a wish to hasten death. 3

Our patient sample allows for a generalization to all diagnoses requiring palliative care. Not only oncological patients frequently report desire to die, but desire to die and suicidality are common in neurological or multimorbid geriatric populations as well. 27

However, we aimed for, but did not achieve heterogeneity regarding patient ethnicity, since used questionnaires were only validated in German and health professionals did not suggest non-native German patients. This limits our interpretation to German native speaking patients.

Practical implications

The majority of patients expressing a desire to die will not die from medical aid in dying. 3 However, with contemporary trends toward more liberal related regulations in numerous countries, an expansion of cases deemed eligible for these practices can be observed. 28 Currently, the debate mainly revolves around the practical realization of such requests and its regulations. Here, we suggest to start conversation about desire to die as the first intervention before any others.

In Germany, the German Palliative Care Guideline for Patients with Incurable Cancer even added the proactive addressing of desire to die as a recommendation following expert consensus. 3 Carefully and respectfully exploring the background and function of a desire to die might allow the health professional to suggest therapeutic measures to date unknown to the patient. It has been shown that most patients receiving palliative care barely know related services or alternatives to assisted suicide or euthanasia. 29 Moreover, they are often not well informed about these requested practices either. Of course, the respective legal framework affects these conversations: Patient expectancies and physician possibilities likely shape content and structure of desire to die-conversations. And yet, accepting desire to die as a possible way of dealing with a life-limiting disease and not as an immediate call to hasten death allows health professionals to take a step back.

Within the framework of our study, trained health professionals held desire to die-conversations supported by our clinical approach.13,15 Addressing the topic without prior training might cause adverse outcomes, as inadequate communication can cause heightened fear and stress in patients. 30 A communicative approach to desire to die that is teachable and adaptable is a practical, low-cost intervention that can meet the growing demand to adequately deal with the phenomenon.

Future research should focus on the beneficial effect on patients within methodically rigorous study designs using control groups but also optimize training modules for health professionals.

Footnotes

Author contributions: RV is principal investigator and responsible for funding acquisition, study design, project management, data analysis, supervision, and dissemination and is responsible for writing (review and editing). As guarantor, he takes full responsibility for the work and the conduct of the study, had access to data and controlled the decision to publish. KB contributed to recruitment, data collection, data analysis, and dissemination and is responsible for writing the original draft. TD contributed to data collection, data analysis and dissemination, and contributed to writing. CR and LG contributed to recruitment, data collection, data analysis, and dissemination. KS-H is responsible for data analysis and software and contributed to writing. KK is principal investigator and responsible for funding acquisition, study design, project management, recruitment, data collection, data analysis, dissemination, and writing.

Data sharing statement: Data cannot be shared publicly because participants were guaranteed protection of personal data within the confines of the German data protection act. Data are available from the University of Cologne, Medical Faculty, Department of Palliative Medicine, Cologne, Germany (contact via kathleen.bostroem@uk-koeln.de) for researchers who meet the criteria for access to confidential data.

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: KB, TD, CR, LG, KS and KK declare no support from any organization for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous 3 years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work. RV reports grants from the Federal Ministry of Education and Research during the conduct of the study. Grants from the Federal Joint Committee (G-BA) Germany, Innovation Fund; Federal Ministry of Education and Research; EU—Horizon 2020; Robert Bosch Foundation; Trägerwerk Soziale Dienste in Sachsen GmbH; Association Endlich Palliativ & Hospiz e.V.; Ministry of Labor, Health and Social Affairs of North Rhine-Westphalia; German Cancer Society, Association of the Scientific Medical Societies, German Cancer Aid; Ministry of Culture and Science of North Rhine-Westphalia; personal fees from AOK Health Insurance; German Cancer Society/National Health Academy (NGA); MSD Sharp & Dome; Hertie Foundation and Roche Germany.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was funded by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (01GY1706).

ORCID iDs: Kathleen Boström  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3159-6535

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3159-6535

Kerstin Kremeike  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4316-2379

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4316-2379

References

- 1. Sleeman KE, de Brito M, Etkind S, et al. The escalating global burden of serious health-related suffering: projections to 2060 by world regions, age groups, and health conditions. Lancet Glob Health 2019; 7(7): e883–e92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. New Engl J Med 2010; 363(8): 733–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Leitlinienprogramm Onkologie DK. Palliativmedizin für Patienten mit einer nicht-heilbaren Krebserkrankung – Langversion 2.2, https://www.leitlinienprogrammonkologie.de/fileadmin/user_upload/Downloads/Leitlinien/Palliativmedizin/Version_2/LL_Palliativmedizin_Langversion_2.2.pdf (2020, accessed 6 January 2021).

- 4. Chochinov HM, Wilson K, Enns M. Desire for death in the terminally ill. Am J Psychiatr 1995; 152(8): 1185–1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wilson KG, Dalgleish TL, Chochinov HM, et al. Mental disorders and the desire for death in patients receiving palliative care for cancer. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2016; 6(2): 170–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rodin G, Lo C, Mikulincer M, et al. Pathways to distress: the multiple determinants of depression, hopelessness, and the desire for hastened death in metastatic cancer patients. Soc Sci Med 2009; 68(3): 562–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Galushko M, Frerich G, Perrar KM, et al. Desire for hastened death: how do professionals in specialized palliative care react? Psychooncology 2016; 25(5): 536–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Willmott L, White B, Ko D, et al. Restricting conversations about voluntary assisted dying: implications for clinical practice. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2020; 10(1): 105–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dierickx S, Cohen J. Medical assistance in dying: research directions. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2019; 9(4): 370–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. DeCou CR, Schumann ME. On the iatrogenic risk of assessing suicidality: a meta-analysis. Suicide Life Threat Behav 2018; 48(5): 531–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Porta-Sales J, Crespo I, Monforte-Royo C, et al. The clinical evaluation of the wish to hasten death is not upsetting for advanced cancer patients: a cross-sectional study. Palliat Med 2019; 33(6): 570–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kremeike K, Galushko M, Frerich G, et al. The DEsire to DIe in palliative care: optimization of management (DEDIPOM) – a study protocol. BMC Palliat Care 2018; 17(1): 30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kremeike K, Frerich G, Romotzky V, et al. The desire to die in palliative care: a sequential mixed methods study to develop a semi-structured clinical approach. BMC Palliat Care 2020; 19: 49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kremeike K, Dojan T, Rosendahl C, et al. “Withstanding ambivalence is of particular importance – “controversies among experts on dealing with desire to die in palliative care. PLoS One 2021; 16(9): e0257382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Frerich G, Romotzky V, Galushko M, et al. Communication about the desire to die: development and evaluation of a first needs-oriented training concept – aa pilot study. Palliat Support Care 2020; 18: 528–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. IBM Corp. IBM SPSS statistics for Windows. version 25.0 ed. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Aktas A, Walsh D. Methodological challenges in supportive and palliative care cancer research. Semin Oncol 2011; 38(3): 460–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Downar J, Goldman R, Pinto R, et al. The “surprise question” for predicting death in seriously ill patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. CMAJ 2017; 189(13): E484–E493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Van der Feltz-Cornelis CM, Van Oppen P, Van Marwijk HW, et al. A patient-doctor relationship questionnaire (PDRQ-9) in primary care: development and psychometric evaluation. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2004; 26(2): 115–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chilcot J, Rayner L, Lee W, et al. The factor structure of the PHQ-9 in palliative care. J Psychosom Res 2013; 75(1): 60–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Krampen G. Skalen zur Erfassung von Hoffnungslosigkeit (H-Skalen). Deutsche Bearbeitung und Weiterentwicklung der H-Skala von Aaron T. Beck. Testmappe. Göttingen: Hogrefe, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kliem S, Lohmann A, Mößle T, et al. Psychometric properties and measurement invariance of the Beck hopelessness scale (BHS): results from a German representative population sample. BMC Psychiatry 2018; 18(1): 110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Krause S, Rydall A, Hales S, et al. Initial validation of the death and dying distress scale for the assessment of death anxiety in patients with advanced cancer. J Pain Symptom Manag 2015; 49(1): 126–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Voltz R, Galushko M, Walisko J, et al. Issues of “life” and “death” for patients receiving palliative care-comments when confronted with a research tool. Support Care Cancer 2011; 19(6): 771–777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med 2001; 16(9): 606–613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Perczel Forintos D, Rózsa S, Pilling J, et al. Proposal for a short version of the Beck hopelessness scale based on a national representative survey in Hungary. Community Ment Health J 2013; 49: 822–830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Strupp J, Ehmann C, Galushko M, et al. Risk factors for suicidal ideation in patients feeling severely affected by multiple sclerosis. J Palliat Med 2016; 19(5): 523–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chambaere K, Vander Stichele R, Mortier F, et al. Recent trends in euthanasia and other end-of-life practices in Belgium. N Engl J Med 2015; 372(12): 1179–1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Taber JM, Ellis EM, Reblin M, et al. Knowledge of and beliefs about palliative care in a nationally-representative U.S. Sample. PLoS One 2019; 14(8): e0219074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Fallowfield LJ, Jenkins VA, Beveridge HA. Truth may hurt but deceit hurts more: communication in palliative care. Palliat Med 2002; 16(4): 297–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]