Abstract

Background:

There is a growing demand for community palliative care and home-based deaths worldwide. However, gaps remain in this service provision, particularly after-hours. Paramedicine may help to bridge that gap and avoid unwanted hospital admissions, but a systematic overview of paramedics’ potential role in palliative and end-of-life care is lacking.

Aim:

To review and synthesise the empirical evidence regarding paramedics delivering palliative and end-of-life care in community-based settings.

Design:

A systematic integrative review with a thematic synthesis was undertaken in accordance with Whittemore and Knafl’s methodology. Prospero: CRD4202119851.

Data sources:

MEDLINE, CINAHL, PsycINFO and Scopus databases were searched in August 2020 for primary research articles published in English, with no date limits applied. Articles were screened and reviewed independently by two researchers, and quality appraisal was conducted following the Mixed-Methods Appraisal Tool (2018).

Results:

The search retrieved 5985 articles; 23 articles satisfied eligibility criteria, consisting of mixed-methods (n = 5), qualitative (n = 7), quantitative descriptive (n = 8) and quantitative non-randomised studies (n = 3). Through data analysis, three key themes were identified: (1) Broadening the traditional role, (2) Understanding patient wishes and (3) Supporting families.

Conclusions:

Paramedics are a highly skilled workforce capable of helping to deliver palliative and end-of-life care to people in their homes and reducing avoidable hospital admissions, particularly for palliative emergencies. Future research should focus on investigating the efficacy of palliative care clinical practice guideline implementation for paramedics, understanding other healthcare professionals’ perspectives, and undertaking health economic evaluations of targeted interventions.

Keywords: Palliative care, terminal care, emergency medical services, ambulances, patient transfer, review

What is already known about the topic?

Global demand for palliative care is increasing and the reliance on exclusively specialist hospital-based care is becoming unsustainable. Community preferences also favour home-based deaths.

Paramedics are in a unique position to help deliver palliative and end-of-life care in the home, especially after-hours for palliative care emergencies. However, their role is traditionally limited to providing life-sustaining interventions for acute emergencies and conveyance to hospital.

No overview of the role paramedics play in delivering palliative and end-of-life care in community-based settings currently exists.

What this paper adds?

The findings of the review suggest paramedics can play an important role in providing emergency support to patients approaching end-of-life, help facilitate home-based deaths, and reduce avoidable hospital admissions where this is the patient’s preference.

The review identified untimely access to documented wishes, family discordance and the medico-legal ambiguity associated with palliative paramedicine as key barriers preventing paramedics from adopting a palliative approach to care.

Key enablers highlighted within the review include strengthening communication and support channels with multidisciplinary teams, targeted palliative care training for paramedics, partnering in care with families and palliative care specific clinical practice guidelines to broaden the current scope of practice.

Implications for practice, theory or policy

This review underscores the opportunities for health services to consider paramedic involvement in integrated models of community palliative care delivery, especially as an adjunct support in palliative emergencies in collaboration with other services.

Further research developing and evaluating systems to enable paramedics better access to patients documented palliative care plans, targeted palliative care training programmes and palliative care specific clinical practice guidelines is needed.

Introduction

Rationale

Global demand for palliative care is increasing due to an ageing population and the growing prevalence of chronic non-communicable disease, amongst other factors. According to the World Health Organization, approximately 40 million people require palliative care each year. 1 Within Australia, tertiary health services saw a 16.9% increase in palliative care hospitalisations between 2013/14 and 2017/18. 2 However, palliative and end-of-life care being provided exclusively by specialists in hospital settings poses unsustainable costs to health services worldwide. 3 Further, international literature suggests approximately two thirds of people want to die at home. 4

In order to meet the growing need for palliative care, reduce avoidable hospital admissions and better facilitate community preferences, early delivery and a multidisciplinary approach to palliative care service provision is required. 1 One interface capable of facilitating more home-based deaths is paramedicine. Paramedics are a unique workforce, attending to patients in the community 24-h a day 7 days a week, in the case of an emergency. However, their scope of practice has traditionally been limited to providing life-sustaining interventions for acute emergencies and conveyance to hospital.5–7 For patients who have a progressive life-limiting condition, an acute hospital admission may not be desired or the best setting in which to deliver appropriate palliative care.

Fortunately, global ambulance services are evolving in response to the growing prevalence of palliative care patients, although through different approaches and at varying speeds. Traditionally within Franco-German ambulance models 8 emergency medicine physicians provide the majority of prehospital care and are supported by paramedics, allowing for the development of specialist prehospital medical palliative care teams in countries such as Germany. 9 In contrast, Anglo-American ambulance models rely on paramedics providing care to patients with medical oversight. However, there is not a strict dichotomy between these two models. Specialised community paramedic roles are emerging in countries following a paramedic-led ambulance approach to facilitate holistic home-based palliative care, 6 and ambulance services world-wide are adopting clinical protocols to guide end-of-life care, 10 albeit in a variable manner. Other researchers have reviewed the attitudes and perceptions of paramedics delivering palliative care in community-based settings, 11 and provided practical strategies to integrate palliative care into prehospital models of care. 12 However, to our knowledge, no attempt has yet been made to review the evidence of palliative paramedicine in community-based settings. Consequently, a systematic integrative review was conducted, including diverse methodologies, to present a wide variety of perspectives on this aspect of care and contribute to future evidence-based practice of palliative paramedicine. 13

Objectives

This review aimed to systematically synthesise the empirical evidence of palliative paramedicine in community-based settings, answering the following research questions: what (1) is the known scope of practice of paramedics delivering palliative and end-of-life care, (2) are the perspectives of relevant stakeholders involved in paramedics delivering palliative and end-of-life care and (3) are the barriers and enablers experienced by relevant stakeholders when paramedics are delivering palliative and end-of-life care.

Methods

We conducted a systematic integrative review, allowing for inclusion of experimental and non-experimental studies, in accordance with Whittemore and Knafl’s 13 methodology. This type of review was chosen to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the role of paramedics delivering palliative and end-of-life care in community-based settings. The review protocol is registered with Prospero (registration number: CRD42021198518) and we adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines. 14

Search strategy

The preliminary search strategy was defined in June 2020 by one author (MJ), with assistance from a specialist librarian. Refinements were made by the broader research team and the systematic search was performed in August 2020, exploring the phenomenon of paramedics delivering palliative and end-of-life care in community-based settings.

Database searches

Systematic searches of primary research articles published solely in English due to funding constraints were performed in MEDLINE, CINAHL, PsycINFO and Scopus. No publication date range limits were applied in anticipation of the search deriving a small number of articles, given the novel nature of the topic.

The Medline search strategy was performed first, as illustrated in Table 1, and the search profile was adapted for subsequent databases.

Table 1.

MEDLINE search strategy.

| Search term | |

|---|---|

| #1 | emergency medical services/ or emergency medical dispatch/ or ‘transportation of patients’/ or ambulance diversion/ or ambulances/ |

| #2 | Emergency Medical Technicians/ |

| #3 | Patient Transfer/ |

| #4 | paramedic*.mp. |

| #5 | ambulance*.mp. |

| #6 | (prehospital or pre-hospital).mp. [mp=title, abstract, original title, name of substance word, subject heading word, floating sub-heading word, keyword heading word, organism supplementary concept word, protocol supplementary concept word, rare disease supplementary concept word, unique identifier, synonyms] |

| #7 | 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 |

| #8 | exp Terminal Care/ |

| #9 | Hospices/ |

| #10 | Legislation, Medical/ |

| #11 | advance care planning/ or advance directives/ or living wills/ |

| #12 | Attitude to Death/ |

| #13 | bereavement/ or grief/ or disenfranchised grief/ |

| #14 | life support care/ or advanced cardiac life support/ or advanced trauma life support care/ |

| #15 | Terminally Ill/ |

| #16 | (palliative or palliation).mp. [mp=title, abstract, original title, name of substance word, subject heading word, floating sub-heading word, keyword heading word, organism supplementary concept word, protocol supplementary concept word, rare disease supplementary concept word, unique identifier, synonyms] |

| #17 | SPCS.mp. |

| #18 | ((advance* or terminal) adj1 (illness* or care or directive*)).mp. [mp=title, abstract, original title, name of substance word, subject heading word, floating sub-heading word, keyword heading word, organism supplementary concept word, protocol supplementary concept word, rare disease supplementary concept word, unique identifier, synonyms] |

| #19 | (end adj2 life).mp. |

| #20 | (therapeutic* adj1 limit*).mp. |

| #21 | (document* adj2 wish*).mp. |

| #22 | 8 or 9 or 10 or 11 or 12 or 13 or 14 or 15 or 16 or 17 or 18 or 19 or 20 or 21 |

| #23 | 7 and 22 |

References and citations of included papers were additionally checked to ensure no relevant literature was missed.

Eligibility criteria

As illustrated in Table 2, articles were included if they presented empirical studies about paramedics delivering palliative and end-of-life care in community-based settings.

Table 2.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

| • English language and earliest records to present • Empirical studies in peer reviewed literature • Full-text available • Participants of any age or gender • Participants include patients, families and health professionals involved in the care provided and stakeholder experience of paramedics delivering palliative and end-of-life care • Palliative and end of life care delivered by paramedics in a prehospital community-based environment for example, home or residential aged care facility |

• Languages other than English • Non-empirical studies, editorials, opinion pieces and grey literature • Focus on health professionals other than paramedics delivering palliative and end-of-life care • Palliative and end-of-life care delivered outside of a prehospital community-based environment for example, hospital or hospice • Full-text not available |

Study selection

Upon excluding duplicate articles, two members of the research team (MJ and PV) independently screened the remaining titles and abstracts using the Covidence systematic review management software. 15 Full-text articles (n = 114) were independently assessed against the inclusion and exclusion criteria by the same team members, with a total of 23 articles identified for data extraction and quality appraisal.

Data extraction, analysis and synthesis

Data analysis and thematic synthesis were conducted by MJ, cross-checked by PV, and finalised by the broader research team. Whittemore and Knafl’s 13 methodology was adopted throughout, including (1) data reduction, (2) data display, (3) data comparison and (4) conclusion drawing. Firstly, data were reduced by dividing the studies into sub-groups according to type: qualitative; mixed-methods; quantitative non-randomised; and quantitative descriptive. A study-designed data extraction table was created to simplify data into a manageable framework. The table was piloted on five articles by one author; its rigor was then discussed amongst the broader research team and minor modifications were made to the table. 16 Data were extracted into the table on Excel for the remaining articles by one author, with 20% cross-checked by a second author and 100% interrater agreement achieved. The table displayed information on the author, country, study design, participants, setting, study aims, measures, study outcomes and results, and strengths and weaknesses (Table 3).

Table 3.

Data extraction.

| Author (country) | Study design | Participants | Setting | Study aims | Measures | Study outcomes/results | Quality appraisal score | Strengths and weaknesses |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carter et al. 17 (Canada) | Mixed methods study (QUAN + QUAL + QUAN) Evaluating patient, family and paramedic satisfaction of a paramedic capacity building programme, including: – A new palliative care specific clinical practice guideline – An updated database system – Training in palliative care and end-of-life care. |

Part A: Patients and families with paramedic palliative and end-of-life care encounters: Patient enrolment survey (n = 67) Patient interview (n = 18); Age (X = 78.4) Part B: Ambulance staff: Pre-intervention (n = 235) Post-intervention (n = 267) |

Two Canadian provincial ambulance services. | To determine the impact of the programme in two parts: Part A: Patient and family satisfaction Part B: Paramedic comfort and confidence with the delivery of palliative care support. |

Part A: Study-developed postal surveys and validated semi-structured interview guide modified for the ambulance context.

18

Part B: Validated pre versus post-intervention surveys using Likert scales. 19 |

Quantitative: Comfort with providing palliative care without transport improved post intervention (p ⩽ 0.001) as well as confidence in palliative care without transport (p ⩽ 0.001). Participants strongly agreed that all paramedics should be able to provide basic palliative care. Qualitative: Main themes include: – Fulfilling care wishes – Family/caregiver peace of mind – Feeling prepared for emergencies – Professionalism and compassion of paramedics – 24/7 availability – Relief of symptoms – A plea for programme continuation |

6 | Strengths: In-depth exploration of multiple key stakeholders’ perspectives on the impact of the programme; data saturation achieved. Weaknesses: Small sample size with early divergence of thematic saturation; time lapse between encounter and interview; low-moderate response rate to enrolment survey. |

| Hoare et al. 20 (UK) | Qualitative interviews (n = 6) of ambulance staff involved in the transfer of patients (case-patients) aged more than 65 years to hospital who died within 3 days of admission with either cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or dementia. | Ambulance staff: Paramedics (n = 2) Student paramedics (n = 3) Emergency care assistants (n = 1) |

Large English hospital. | To understand the role of ambulance staff in the admission to hospital of patients close to the end-of-life. | Semi-structured interviews using a study-developed interview guide. | Main themes include: – Limited availability and accessibility of additional care and support in the community – Ambulance staff having limited access to information on the patient and their condition – Perceived ambulance service emphasis on hospital care |

7 | Strengths: Detailed analysis on the role of ambulance staff transporting patients nearing end-of-life to hospital; case-patient sample reflective of national trends. Weaknesses: Small ambulance staff sample size affecting likelihood of saturation of themes. |

| Jensen et al. 21 (Canada) | Qualitative focus group interviews (n = 4) investigating ambulance staff perspectives of a paramedic capacity-building programme for Extended Care Paramedics, including: – Specialised training in geriatric assessments and management, end-of-life care, primary wound closure techniques and point of care testing – Medical oversight from a dedicated ambulance service online medical physician – Established offline clinical guidelines. |

Ambulance staff: (n = 21); Age (X = 41, SD = 6.93) Extended care paramedics (6) Extended care paramedic oversight physicians (3) Decision makers (5) Paramedics (6) Communication officers (1) |

One Canadian provincial ambulance service. | To learn of the experiences of those directly involved in various aspects of the programme: 1. What insights have been gained and lessons learned from the implementation and operation of the programme? 2. What are the experiences of Extended Care Paramedics in particular clinical situations, specifically end of life cases? |

Focus groups using a study-developed semi-structured interview guide. | Main themes include: – Programme implementation – Extended Care Paramedic process of care – Communications – End-of-life care |

7 | Strengths: Focus groups provided exploratory inquiry with interaction among the participants and facilitator. Weaknesses: Small sample size, although representative; potential for sensitive topics to be avoided by individuals in focus group settings. |

| Kirk et al. 22 (UK) | Quantitative descriptive survey distributed to paramedics across a large geographical area. | Ambulance staff: (n = 182); Age (X = 41) Entry-level paramedic (93) Senior/specialist paramedic (65) Advanced paramedic (24) |

One English ambulance service. | To investigate whether paramedics view end-of-life care as a key part of their role, their confidence in managing this aspect of clinical practice, and the underlying concerns of paramedics when managing end-of-life care. | Validated online survey tool including closed, Likert scale and multiple-choice questions. 23 | The majority of participants agree that end-of-life care is a key part of their role as a paramedic (n = 141, 78%). Many feel they need more education and poorly rate current training (n = 92, 51%). The majority of paramedics have medium to high confidence when dealing with end-of-life in clinical practice, with length of service and end of life experience being a key contributor. Significant concerns about documentation, litigation and perceived lack of communication between different healthcare services were expressed. | 6 | Strengths: Comprehensive sample size reflected varied demographics, allowing for analysis variance; piloted instrument. Weaknesses: Observational studies and interviews would gain more in-depth perspectives; non-random sampling; intervariability in staff categories; self-reported data. |

| Leibold et al. 24 (Germany) | Quantitative descriptive survey of paramedics across the country. | Ambulance staff: (n = 429); Age (X = 31) |

All German ambulance services. | To determine whether a paramedic’s decision-making in end-of-life situations is influenced by their religious beliefs, how they decide given the current judicial framework, and how they would decide were there legal certainty. | Study-developed and validated online questionnaire including yes/no interrogatives, Likert scale and open questions. | Religious paramedics would rather hospitalise a patient holding an advance directive than leave them at home (p = 0.036) and think death is less a part of life than the non-religious (p = 0.001). | 7 | Strengths: Literature review informed questionnaire; pilot phase of questionnaire ensured readability and appropriateness of content. Weaknesses: Reliability and validity were not applied; voluntary participation subject to bias; accurate response rate unknown; self-reported data. |

| Lord et al. 25 (Australia) | Retrospective cohort study of adult palliative and end-of-life patients receiving treatment from one ambulance service. | Adult patients attended by paramedics: (n = 4348); Age (X = 74) |

One Australian state ambulance service. | To describe the incidence and nature of cases attended by paramedics and the care provided where the reason for attendance was associated with a history of palliative care. | Electronic patient care records. | The most common paramedic assessments were ‘respiratory’ (20.1%), ‘pain’ (15.8%) and ‘deceased’ (7.9%); 74.4% were transported, with the most common destination being a hospital (99.5%). Of those with pain as the primary impression, 53.9% received an analgesic and 99.2% were transported following analgesic administration. Resuscitation was attempted in 29.1% of the 337 cases coded as cardiac arrest. Among non-transported cases, paramedics re-attended the patient within 24 h of the previous attendance for 9.6% of the cases. | 6 | Strengths: State-wide study allowing for broad representation; study design reduces sampling and recall bias; causality can be inferred. Weaknesses: Retrospective data; non-experimental design. |

| Lord et al. 26 (Australia) | Qualitative focus groups and interviews (n = 32) of paramedics employed by two ambulance services in Australia. |

Ambulance staff: (n = 32) |

Two Australian state ambulance services | To identify paramedics’ knowledge, beliefs and attitudes related to the care of patients requiring palliative care in community settings. | Focus groups and interviews using a study-developed semi-structured interview guide. | Main themes include: – Conflict in care goals – Legal issues – Access to information – Organisational policy and clinical practice guidelines |

6 | Strengths: Detailed analysis on the perspectives and experiences of paramedics delivering palliative and end-of-life care in the community. Weaknesses: Convenience sampling less optimal because it may have failed to capture important perspectives from difficult to reach paramedics. |

| McGinley et al. 27 (US) | Mixed methods study (QUAN + QUAL) applying a critical discourse analysis framework. | Ambulance staff: Survey participants (n = 239); Age (X = 35) Interview participants (n = 48); Age (X = 38) |

Five American ambulance services within one state. | To describe how medical orders inform ambulance services’ decision-making during emergencies involving people with intellectual disabilities who are nearing end-of-life. | Quantitative data collected through a study-developed cross-sectional survey. Qualitative interviews conducted utilising a study-developed demographic questionnaire and semi-structured interview guide. | Quantitative: 62.7% of participants had treated a person with intellectual disability who had medical orders directing end-of-life care. Qualitative: Main themes include: – Provider familiarity – Organisational processes – Sociocultural context |

6 | Strengths: Exploratory-descriptive study design employing iterative enquiry from three focal lengths; large sample size. Weaknesses: Purposive sampling open to subject bias; state-based laws not generalisable to an (inter)national context; study does not include the perspectives of people with intellectual disabilities or their caregivers. |

| Mott et al. 28 (Australia) | Quantitative descriptive survey of ambulance officers known to have had an interaction with one of the last 50 paediatric palliative care referrals. | Ambulance staff: (n = 22) |

One Australian state ambulance service. | To explore the experiences and attitudes of ambulance officers in managing paediatric patients with palliative care needs. | Study-developed questionnaire including yes/no interrogatives, option selections, Likert scale and free-text questions. | Many participants felt these cases were challenging, confidence levels varied, and staff counselling services were felt to be relevant by 50%. Ambulance officers were most likely to use correspondence provided by the family from their usual team as a guide for emergency management. 50% of the participants felt patients receiving paediatric palliative care should have a ‘not for resuscitation’ order. Respondents suggested officer support could be improved through increased patient documentation and promotion of existing officer supports. | 3 | Strengths: State-wide study allowing for broad representation. Weaknesses: Purposive sampling open to subject and recall bias; small sample size due to low completion rate; self-reported data. |

| Murphy-Jones and Timmons 29 (UK) | Qualitative interviews (n = 6) of active paramedics unknown to the primary author. | Ambulance staff: (n = 6) |

One English ambulance service. | To explore how paramedics make decisions when asked to transport nursing home residents nearing end-of-life. | Semi-structured interviews using study-developed questions and photo elicitation. | Main themes include: – Challenges in understanding patients’ wishes – Evaluating patients’ best interests – The influence of others on decision making |

7 | Strengths: Interviews included photo elicitation, prompting deeper and more insightful reflection; review of recorded data analysis decisions to enhance confirmability and dependability. Weaknesses: Small purposive sample size open to subject and recall bias; recruited from one site limiting transferability. |

| Patterson et al. 30 (UK) | Qualitative interviews (n = 10) of paramedics, extracted from a broader study exploring health and social care professionals’ experiences of data recording and sharing practices in end-of-life care. |

Ambulance staff: (n = 10) |

One English ambulance service. | To explore how access and quality of patient information affects the care paramedics provide to patients nearing end-of-life, and their views on a shared electronic record as a means of accessing up-to-date patient information. | Semi-structured interviews informed by a topic guide and revised after each interview to incorporate emerging lines of enquiry. | Main themes include: – Access to information on patients nearing end-of-life – Views on the proposed Electronic Palliative Care Coordination System |

7 | Strengths: In-depth exploration as part of a larger study considering multiple stakeholders’ experiences and perceptions. Weaknesses: Opportunistic sampling strategy; small sample size. |

| Pease et al. 31 (UK) | Mixed methods study (QUAN+QUAL+QUAN) evaluating paramedics’ perceived roles and challenges post-implementation of teaching sessions on: – Serious illness conversation/communication skills – Symptom control at end-of-life – Shared decision making. |

Ambulance staff: Paramedics (n = 218) Final year paramedic students (n = 150) |

Welsh national ambulance service. | To describe the delivery, outcomes and potential impact of a Serious Illness Conversation project on ambulance staff. | Qualitative data collected through participant statements. Quantitative data collected through a study-developed pre- and post-intervention questionnaire using a Likert scale assessing self-confidence, and review of patient care records relating to end-of-life care. | Quantitative: All six communication domains indicate statistically significant improvements in self-assessed confidence in communication domains post-training compared to pre-training (p < 0.001). Qualitative: Main themes include: – Ambulance staff role includes communication, support and practical medical care – Difficulty discussing death and dying and managing expectation. |

4 | Strengths: Exploratory three-stage study design; comprehensive sample size. Weaknesses: Self-rated measures surrogate indicators of outcome; sequential review of patient care records not specific to participants of the training. |

| Rogers et al. 32 (Australia) | Mixed methods study (QUAN + QUAL) identifying and measuring paramedics’ perspectives. | Ambulance staff: (n = 29); Age (X = 38) |

One Australian state ambulance service. | To identify paramedics’ perspectives and educational needs regarding palliative care provision; and investigate paramedics’ views about death and dying, their awareness of common causes of death in Australia, and opinions as to those for which a palliative approach is appropriate. | Piloted and validated qualitative and quantitative survey tool using Likert scales. 33 | Participants considered palliative care to be strongly focussed on end-of-life care, symptom control and holistic care. Educational needs identified were ethical issues, end-of-life communication and the use of structured patient care pathways. Cancer diagnoses were overrepresented as conditions considered most suitable for palliative care, compared with their frequency as a cause of death. Conditions often experienced in ambulance practice, including heart failure, trauma and cardiac arrhythmias were overestimated in their frequency as causes of death. | 7 | Strengths: Piloted and validated survey tool. Weaknesses: Low response rate; small sample size; self-reported data. |

| Stone et al. 34 (US) | Quantitative descriptive survey of paramedics across two states. | Ambulance staff: (n = 236); Age (X = 39) |

Two American ambulance services from two states. | To ascertain paramedics’ attitudes toward end-of-life situations and their frequency; to measure the frequency of end-of-life encounters; to compare paramedics’ preparation for end-of-life care during training; and to compare the importance paramedics place on end-of-life issues. | Validated paper survey tool using multiple choice and Likert scale questions. 35 | Participants perceived end-of-life related issues to be important; however, they do not feel adequately trained in these areas. 95% agreed that prehospital providers should honour advance directives; 59% felt that ambulance staff should honour verbal wishes to limit resuscitation on scene; 95% had questioned whether specific life support interventions were appropriate for terminal patients; and 26% reported having to use their own judgement recently to withhold or end resuscitation in a terminal patient. | 4 | Strengths: Two-step statistical analysis process. Weaknesses: Convenience sampling strategy; low response rate; small sample size; self-reported data. |

| Surakka et al. 36 (Finland) | Retrospective cohort study of patients registered for an end-of-life care at home protocol. | Adult patients attended by paramedics: (n = 252) (X = 76.5) | One Finnish ambulance service. | To evaluate a protocol for end-of-life care at home including pre-planned integration of paramedics and end-of-life care wards. | Electronic patient records, paramedic case-forms and death certificates. | Symptom control (38%) and transportation (29%) were the most common reasons for paramedic attendance. Paramedics visited 43% of patients in areas with 24/7 palliative home care services, in contrast to 70% without this provision. 58% of calls were completed out of hours and 31% of cases were resolved at home. Patients were transferred to pre-planned end-of-life care wards in 48% of cases compared to the emergency department in 16% of cases. 54% of patients died in end-of-life care wards where no 24/7 palliative care home service was available, in comparison to 33% where this service was available. | 6 | Strengths: Province-wide study allowing for broad representation; study design reduces sampling and recall bias; causality can be inferred. Weaknesses: Broader stakeholder opinions and alleviation of symptoms not evaluated. |

| Swetenham et al. 37 (Australia) | Mixed methods study (QUAN + QUAL) evaluating patient, carer and clinician perspectives of a pilot 24/7 emergency palliative care service programme managed by: – Expert phone advice from the specialist palliative care service; and – Face-to-face assessment and management carried out by Extended Care Paramedics. |

Patients attended by Extended Care Paramedics: (n = 40) Interviews: Carers (n = 24) Patients (n = 2) Surveys: Extended Care Paramedics (n = 22) |

One Australian state ambulance service and specialist palliative care service. | To explore the effectiveness of a rapid response programme working alliance between an ambulance service and specialist palliative care service, and whether it meets the expectations of patients, carers and clinicians. | Quantitative data collected through call log data, patients records and study-developed surveys. Qualitative data collected through open-ended study-developed interviews. | Quantitative: Forty Extended Care Paramedic palliative care visits were undertaken during the pilot period; 90% of patients who received an after-hours visit remained at their current site of care. Of the remaining 10%, 5% attended an emergency department and the other 5% were directly admitted to a hospice unit. Qualitative: Paramedics reported palliative care work as rewarding and contributing to job satisfaction; however, demanding and sometimes difficult to meet family expectations. Paramedics appreciated the support of the specialist palliative care service’s on-call telephone support. |

3 | Strengths: Broad exploration considering multiple stakeholders’ experiences and perceptions. Weaknesses: Data collection methodology lacking detail; qualitative data lacking thematic analysis; divergences and inconsistencies between quantitative and qualitative results not addressed. |

| Taghavi et al. 38 (Germany) | Quantitative descriptive survey to ambulance staff across two cities. | Ambulance staff: Paramedic (n = 704) Paramedic in practice (n = 24) |

Two German ambulance services from two cities. | To examine paramedics’ attitudes towards advance directives and end-of-life care. | Study-developed and validated questionnaire including total number, yes/no interrogatives, multiple choice, open answer and Likert scale questions. | 84% of participants considered cardiopulmonary resuscitation in end-of-life patients not useful, and 75% stated they would withhold if legally possible. Participants highlighted more extensive discussion of medico-legal matters concerning advance directives should be included in paramedic training programmes. Participants believed palliative crisis cards should be integrated into end-of-life care. | 7 | Strengths: High response rate (81%); comprehensive sample size reflected varied demographics; piloted survey tool. Weaknesses: No attempts to follow-up non-respondents. |

| Waldrop et al. 39 (US) | Qualitative interviews (n = 43) of ambulance staff actively working for the ambulance service who had previously completed a self-administered survey about end-of-life calls. | Ambulance staff: (n = 43); Age (X = 39) Emergency medical technician (n = 10) Paramedic (n = 33) |

One American ambulance service. | To explore and describe how prehospital providers assess and manage end-of-life emergency calls. | Interviews using a study-developed interview guide. | Main themes include: – Multifocal assessment – Family responses – Conflicts – Management of the dying process |

7 | Strengths: Data saturation achieved; rigour maintained by observer and interdisciplinary triangulation, memos and audit trail. Weaknesses: Recruited from one site limiting transferability. |

| Waldrop et al. 40 (US) | Cross-sectional survey of ambulance staff from one service. | Ambulance staff: (n = 178); Age (X = 34.1) Emergency medical technician (n = 76) Paramedic (n = 102) |

One American ambulance service. | To explore ambulance staff’s perceptions of end-of-life calls, the signs and symptoms of dying, and medical orders for life sustaining treatment. | Study-developed and validated survey tool, including closed and open-ended questions. | Participants reported frequent calls to nursing homes, 47.8% claiming every shift, and Medical Orders for Life Sustaining Treatment forms were seen infrequently by participants. However, when present wishes about intubation (74%), resuscitation (74%), life-sustaining treatment (72%) and cardiopulmonary resuscitation (70%) were identified. The most frequently observed signs and symptoms of dying were diagnosis (76%), hospice involvement (82%), apnoea (75%), mottling (55%) and shortness of breath (48%). | 7 | Strengths: High response rate yielding comprehensive sample size; survey tool piloted and validated. Weaknesses: No attempts to follow-up non-respondents; convenience sampling strategy; recruited from one site limiting generalisability. |

| Waldrop et al. 41 (US) | Cross-sectional survey to ambulance staff in one city. | Ambulance staff: (n = 178); Age (X = 34.1) Emergency medical technician (n = 76) Paramedic (n = 102) |

One American ambulance service. | To identify how ambulance staff learned about end-of-life care, their perceived confidence with and perspectives on improved preparation for such calls. | Study-developed survey, including multiple choice and open-ended questions. | Quantitative: Participants reported learning about medical orders through predominately formal means; however, experiential and self-directed learning was also recorded. 93% of participants were confident in upholding a medical order, 87% were confident in interpreting a medical order, and 87% were confident resolving conflict between differing patient and family wishes. Qualitative: Main themes include: – Prehospital provider education – Public education – Educating health care providers on scope of practice – Conflict resolution skills – Handling emotional families – Clarification of transfer protocols |

7 | Strengths: High response rate yielding comprehensive sample size; in-depth thematic analysis of open-ended questions. Weaknesses: No attempts to follow-up non-respondents; survey tool not piloted or validated; convenience sampling strategy; self-reported data; recruited from one site limiting generalisability. |

| Waldrop et al. 42 (US) | Qualitative interviews (n = 43) of active ambulance staff in one service. | Ambulance staff: (n = 43); Age (X = 39) Emergency medical technician (n = 10) Paramedic (n = 33) |

Two American ambulance services within one state. | To explore prehospital providers’ perspectives on how the awareness of dying and documentation of end-of-life wishes influence decision-making on emergency calls near the end-of-life. | Interviews using a study-developed interview guide. | Main themes include: – Awareness of dying wishes and documented Families were prepared but validation and/or support was needed in the moment. – Awareness of dying wishes, but undocumented Ambulance staff must initiate treatment and medical control guidance was needed. – Unaware of dying wishes and documented Families shocked and expected ambulance staff could stop the patient from dying. – Unaware of dying wishes and undocumented Families were unprepared, uncertain and frantic. |

7 | Strengths: In-depth exploration and thematic analysis of ambulance staff perspectives; rigour maintained by observer and interdisciplinary triangulation, memos and audit trail. Weaknesses: Recruited from two services, limiting transferability; additional perspectives would validate the experiences. |

| Wiese et al. 43 (Germany) | Quantitative descriptive survey of ambulance staff across two cities. | Ambulance staff: (n = 728) |

Two German ambulance services from two cities. | To determine paramedics’ understanding of their role in withholding or withdrawing resuscitation and end-of-life treatment of palliative care patients when an advance directive is present. | Study-designed survey including yes/no interrogatives, multiple choice, open and closed Likert scale questions. | Treating terminally ill patients presented an ethical problem for ambulance staff: if they honour a patient’s wishes they may violate juridical regulations. Participants stated that improved guidelines regarding end of life decision making and following advance directives is necessary; 46% of participants felt they required a greater level of competence concerning decisions to withhold or withdraw resuscitation in terminally ill patients with advance directives. | 7 | Strengths: High response rate (81%); comprehensive sample size reflected varied demographics; piloted survey tool. Weaknesses: No attempts to follow-up non-respondents. |

| Wiese et al. 44 (Germany) | Retrospective cohort study of all prehospital emergency physician-based resuscitations during cardiac arrest situations of out-of-hospital palliative care patients with advanced cancer where no curative therapeutic approach could be applied. | Palliative care patients in cardiac arrest attended by ambulance staff: (n = 88) |

Four German ambulance services. | To provide information about the strategic and therapeutic approach employed by Emergency Medical Teams in outpatient palliative care patients in cardiac arrest. | Standardised emergency medical documents, including hospital records. | Of the 88 patients analysed, the Emergency Medical Team began resuscitation in 78%. 11% showed a return of spontaneous circulation; however, none survived after 48 h. Advance directives were available in 43% of the cases. | 6 | Strengths: Study design reduces sampling and recall bias. Weaknesses: Data not generalisable beyond the German physician-based ambulance service model of care; retrospective data; non-experimental design. |

As data from quantitative, qualitative and mixed-methods studies were entered into the extraction table, a descriptive summary for data synthesis was necessary. 13 Primary quantitative studies did not meet the assumptions required for meta-analysis and therefore could not be combined statistically. 45 A thematic analysis was undertaken on the qualitative data and a constant data comparison method was employed across the data of all study types. Initially, data from the qualitative studies were coded and compared systematically through an iterative process to identify patterns, themes and relationships between the studies’ findings. This coding framework was then applied to the qualitative data of the mixed-methods studies. Themes were compared and contrasted, and higher-order themes were identified that incorporated sub-themes due to interrelated data. Finally, relevant quantitative findings were integrated into the themes in adherence with an integrative synthesis approach, 13 and conclusions were drawn across the entire data set.

Quality appraisal

All 23 studies were appraised for methodological quality by one team member, with 20% cross-checked by a second author and 100% interrater agreement achieved. The Mixed-Methods Quality Appraisal Tool (MMAT) was used to assess the quality of the articles given the integrative nature of the review: qualitative, quantitative and mixed-methods studies could all be appraised using the one tool. 46 Furthermore, a number of mixed-method reviews in the field of palliative care have recently used this tool to assess for quality,16,47,48 allowing comparability. The MMAT includes two general yes/no questions, followed by five study-specific yes/no questions, resulting in a maximum score of 7. The included studies had scores ranging between 3 and 7, with the majority scoring 6 or 7, thus indicating the inclusion of predominately high-quality studies.

Results

Study characteristics

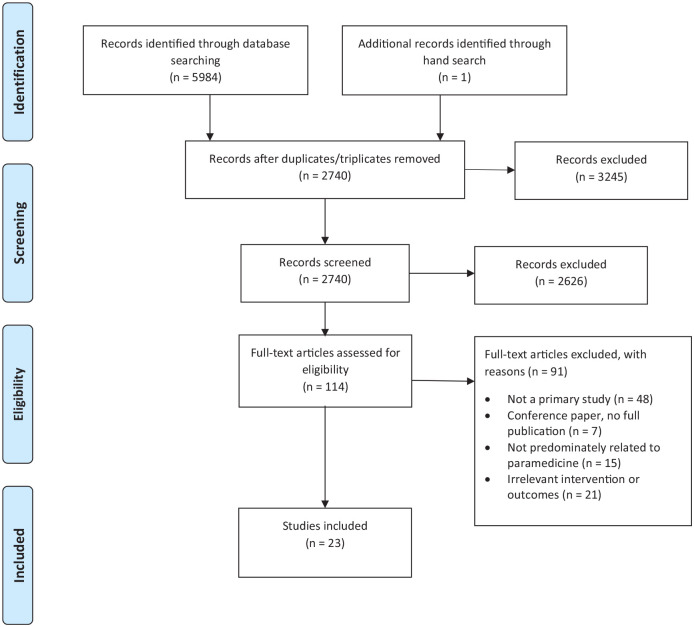

A total of 23 studies were included in the review, as illustrated in Figure 1 (PRISMA flowchart). The studies derived from Australia (n = 5),25,26,28,32,37 Canada (n = 2),17,21 Finland (n = 1), 36 Germany (n = 4),24,38,43,44 the United Kingdom (n = 5)20,22,29,30,31 and the United States (n = 6)27,34,39,40,41,42 between 2009 and 2020. Study methodologies varied and included qualitative (n = 7),17,20,26,29,30,39,42 quantitative non-randomised (n = 3),25,36,44 quantitative descriptive (n = 8)22,24,28,34,38,40,41 and mixed-methods studies (n = 5).17,27,31,32,37 Sample sizes of the included studies were between 5 and 4348 participants; the majority of participants were ambulance staff (n = 20),17,20–22,24,26–32,34,37–43 as well as patients (n = 4)25,36,37,44 and family members (n = 2).17,37

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart.

Each study broadly investigated the role of paramedics delivering palliative and end-of-life care in community-based settings. Studies were performed mainly in ambulance services (n = 21).17,21,22,24–32,34,36,38–44 However, one study took place in a hospital despite being focussed on community-delivery of care, 20 and another in an ambulance service partnering with a specialist palliative care service. 37 Four studies investigated the impact of palliative and end-of-life care training and education programmes,17,21,31,37 two studies considered palliative care patient hospital admissions,20,29 nine studies examined perceptions and attitudes towards palliative and end-of-life care,22,24,26,28,32,34,39–41 three studies observed the nature of palliative care cases attended by paramedics25,36,44 and five studies explored the role of medical orders and documentation on clinical decision making.27,30,38,42,43

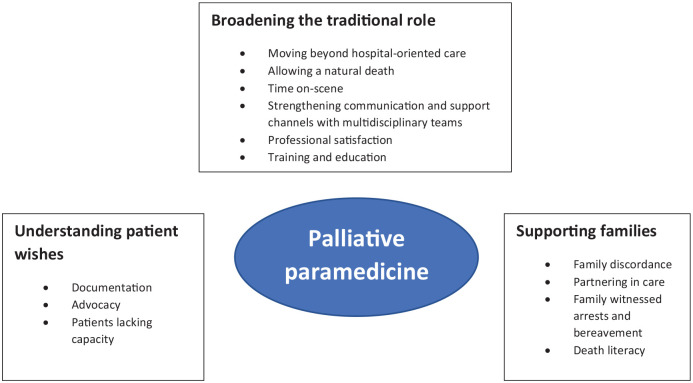

Main findings and key themes

Thematic analysis of the 23 included studies resulted in the following three main themes: (1) Broadening the traditional role, (2) Understanding patient wishes and (3) Supporting families. Each main theme is supported by sub-themes, as illustrated in Figure 2. Exemplar quotes from either original study participants or authors’ text were extracted to illustrate each theme.

Figure 2.

Palliative paramedicine.

Broadening the traditional role

All but one of the included studies explored the concept of broadening a paramedic’s role beyond the traditional scope.17,20–22,24–32,34,36–41,43,44 Seventeen recognised the multidimensional role paramedics play in providing care to patients nearing end-of-life, highlighting a strong desire amongst ambulance staff, family members and patients alike for paramedics to refocus their attention on holistic home-based management of palliative symptoms instead of hospital conveyance.20–22,24–29,31,32,36–39,41,43,44 One study called for a ‘change in practice, from quickly treating and transporting patients who are so acutely unwell, to remaining on-scene and supporting them through the dying process’. 21 However, another study recognised paramedics require specialised skills to successfully navigate the difficult and often uncertain circumstances associated with end-of-life care, including clinical confidence, an authoritative stance, rapid assessment, clear decision-making and strong communication skills. 41

According to a study investigating ambulance staff’s perceptions of end-of-life calls, the most frequently encountered symptoms of a dying patient include shortness of breath, dysphagia, unmanaged pain, and intractable nausea and vomiting, which are manageable for paramedics within the community. 40 These findings were supported by a retrospective cohort study evaluating paramedic attendance of patients with an end-of-life protocol. 36 However, despite many participants expressing concern over the level of suffering a palliative patient endures when undergoing life-prolonging treatment and transportation to hospital, four studies highlighted professional repercussions and fear of litigation as major barriers affecting a paramedic’s ability to move beyond hospital-oriented care.20,26,27,29 Other studies explored this further, recognising the ethical dilemma and apprehension paramedics face when resuscitating a palliative care patient – a default procedure in many clinical practice guidelines – and expressed a strong desire to facilitate natural death despite often lacking the legal latitude.24,34,38 One participant from a study investigating paramedics’ decision making during end-of-life emergencies involving people with intellectual disabilities proclaimed, ‘we’re doing lifesaving efforts because we’re following the law instead of what is ethical [and] morally right (paramedic)’. 27 Another study quantified the poor outcomes associated with prehospital end-of-life cardiopulmonary resuscitation, acknowledging only 2% of palliative patients survived following hospital discharge. 25

Comparatively, 21 studies highlighted enabling factors for broadening the traditional paramedic role, including increasing time on-scene,21,26,37 strengthening communication and support channels with multidisciplinary teams,17,20–22,24–29,31,36,37,40,41,43,44 and expanding palliative care training and education offerings to paramedics.17,21,22,24–26,28,30–32,34,38–41 Notably, in one study hospital-based death was reported for 54% of 252 patients in areas where paramedics did not have access to 24/7 palliative home care services, in comparison to 33% in areas where these services were available. 36 Paramedic length of service and end-of-life experience appeared to be other key factors facilitating paramedic confidence to treat a palliative patient. 22

An Australian study piloted an educational programme for extended care paramedics and connected them with a specialist palliative care service, resulting in the establishment of a collective 24/7 emergency response to palliative patients in the community. 37 This initiative fostered a strong mutual respect between the two clinical services, evidenced by ongoing collaborative training sessions and inter-professional teamwork. As a result, 90% of patients receiving the after-hours care remained at their home, avoiding hospitalisation. 37 Other studies supported these findings, acknowledging a change in paramedic scope of practice to enable better management of end-of-life patients required focussed educational interventions,21,22,25,26,28,31,34,38–41,43,44 improved access to equipment and anticipatory medications,30,31 strong linkages to palliative care specialist teams,22,24,25,27,28,31,37,39 and end-of-life care clinical practice guidelines to standardise practice.22,26,28,36

Lord et al.’s 2012 study reported on the limiting nature of existing clinical practice guidelines, highlighting ‘99% of the drugs we administer you need to take [the patient] to hospital. There is no “treat and release” (paramedic)’. Another study evaluated the use of a paramedic end-of-life protocol, which aimed to extend the role and scope of practice for paramedics managing palliative patients at home. 36 Within this study, 56% of patients required an unscheduled transfer, of whom only 14% were transported to the emergency department. 36 Comparatively, another study lacking such a protocol required an unscheduled transfer for 74% of the patients, of whom 99% went to the emergency department. 25 Equipping paramedics with the skills and resources to deliver effective palliative care also results in professional satisfaction, with participants from three studies remarking on the rewarding nature of providing good end-of-life care to patients and their families.17,32,37

Understanding patient wishes

Seventeen studies reported on understanding patient wishes as paramount to paramedics providing quality palliative care in community settings.20–22,24,26,27,29–31,34,38–42 As described by one study, central to this concept is the paramedic’s role as an advocate, upholding a patient’s dignity, respect and goals of care at all times. 31 Legible documentation that clearly outlines a patient’s preferences was highlighted as another key facilitator for paramedics.

However, a study exploring the experiences and attitudes of paramedics managing paediatric patients with palliative care needs highlighted that in participants’ experience most emergency care plans for this population do not include intervention limitations, such as ‘No cardiopulmonary resuscitation (No CPR) orders’. 28 This finding conflicted with the opinion of most participants: more than half expressed a view that all paediatric palliative care patients should have a ‘No CPR order’ in place to avoid the need for paramedics to provide distressing and potentially futile interventions to this vulnerable group. This common opinion amongst paramedics diverges from best practice family centred paediatric palliative care, whereby medical teams rarely implement a ‘No CPR’ order against parental wishes and highlights the need for specialist education and training for paramedics in this complex area of palliative care.

Field-based interpretation of documented wishes were cited by six studies as a source of difficulty and confusion amongst paramedics delivering palliative care.21,22,24,26,28,41 One study acknowledged documentation is often completed before a medical crisis rather than during an end-of-life emergency. 42 These processes may precipitate irrational planning, such as a patient documenting home-based death as their preference, which the family and patient may later be unable to tolerate or facilitate. In circumstances where aggressive care plans are in place one study reported on the notion of ‘flipping the plan’, whereby a paramedic revaluates the care plan on-the-spot and initiates a palliative approach in consultation with the family and clinical back-up. 21

Accessibility issues were cited by nine studies as another key barrier to fulfilling documented patient wishes.20–22,26,27,29,30,34,39 These studies recognised the prominence of incomplete and illegible documents, including one study reporting ‘nearly half of the participants have been unable to determine the authenticity of a written or verbal advance directive to withhold or withdraw interventions in the field’. 34 Four studies remarked on the large number of palliative patients without documented wishes who often encounter otherwise avoidable hospital admissions.20,22,27,30,44

Untimely access to documented wishes was reported as a prohibitive factor for paramedics seeking to understand patient wishes, leading many paramedics to initiate invasive treatment pathways and transportation to hospital.20,22,26,30,39,44 However, electronic health records were investigated by one study as an effective means for paramedics to access up-to-date patient information if relevant documentation was embedded, community palliative care team details were included and remote accessibility was supported by strong WIFI or telephone signal capability. 30

Patients lacking decision-making capacity was reported in four studies,27,29,39,42 highlighting the importance for paramedics identifying a proxy decision maker or legally appointed guardian in these circumstances. However, one study emphasised the legal duty of paramedics to honour patients’ rights to self-determination when they have capacity. 39

Finally, religiosity was reported to influence a paramedic’s interpretation of documentation and decision making. According to one study investigating this factor, paramedics considering themselves religious would rather hospitalise a patient holding a legally binding advance directive than leave them at home when compared to non-religious paramedics. 24

Supporting families

Families were a prominent theme in fourteen of the included studies,17,21,22,26,27,29,31,34,37,39–42 and partnering in care was often considered an integral consideration for paramedics delivering palliative and end-of-life care.17,21,22,27,31,34,37,40,42 One study highlighted the importance of conducting multi-focal assessments that include family relations when reviewing a palliative patient, allowing paramedics to explore the influence of family dynamics on the patient’s wellbeing and establish holistic pathways of care. 39 This concept was supported by five other studies, recognising families are often key decision makers in end-of-life situations and paramedics must establish a strong rapport to facilitate supported decision making.17,21,22,27,39,42

Interpersonal skills were highlighted as another key attribute of paramedics delivering effective palliative and end-of-life care: five studies recognised a paramedic’s clear communication of care options with families could achieve better outcomes for the patient, reduce avoidable hospitalisations and prevent unwanted resuscitation where possible.21,31,34,39,42 Another study reported the strong interrelationship between person-centred care and family guidance, noting family members felt a peace of mind when paramedics were strong communicators and could respect the patient’s goals of care, supporting families at home if a palliative crisis arose. 17

In contrast, family discordance was reported by nine studies as a significant barrier to paramedic practice of palliative and end-of-life care.22,26,29,31,37,39–42 More than half the participants in one study raised concerns over handling conflict between patients and family members, especially when there were inconsistent expectations of outcomes. 22 This comment was supported by three other studies recounting families calling ambulance teams to stop the dying process of their loved one, despite a palliative diagnosis and pathway already existing.31,39,42 In response to conflict, a study exploring paramedics’ decision making around transporting nursing home residents nearing end-of-life emphasised, ‘discord between individuals’ competing interests and that of the families (was) a process of negotiation’. 29

Family-witnessed cardiac arrests were reported as another significant challenge for paramedics responding to patients nearing end-of-life.37,39,40,42,44 One study described the emotional intensity and volatility of a palliative patient arresting as, ‘what might be considered routine in Emergency Medical Services’ but ‘the worst emergency in the world for the family’. 39 Four studies recognised psychosocial support as a critical component of a paramedic’s role in supporting end-of-life discussions and facilitating bereavement.37,39,41,42

Finally, five studies reported a greater need for patient and family death literacy to better facilitate a paramedic’s ability to provide palliative and end-of-life care in the community.22,26,39,41,42 A study exploring paramedics’ perspectives on how awareness of dying and documentation of end-of-life wishes influenced decision-making on emergency calls, concluded that families must be educated beyond medical decision-making to also comprehend the dying process, advance care planning and legal issues arising from documented medical orders. 42

Discussion

This systematic integrative review presents an overview of the literature on paramedics delivering palliative and end-of-life care in community-based settings. Key themes to emerge from the synthesis of studies include broadening the traditional role, understanding patient wishes and supporting families.

From our findings, paramedics consider palliative and end-of-life care an important and increasingly prevalent component of their scope of practice. This notion is supported by the World Health Organisation, which asserts specialist palliative care alone is insufficient to fulfil the growing demand and instead, requires an integrated approach from a multitude of clinical disciplines. 1 However, certain barriers exist which hinder a paramedic’s ability to provide optimal palliative care. Most notably, it has been emphasised that paramedic practice should no longer be constrained by traditional models of hospital-oriented care, and communication and support channels with multidisciplinary palliative care teams must be strengthened to improve paramedic end-of-life care capacity.

Palliative paramedicine should not replace existing specialist community palliative care teams in providing palliative care to community-based patients. Rather, the findings of this review position the role of a paramedic delivering palliative and end-of-life care as an adjunct service, especially after-hours, to existing community palliative care teams. Paramedics act as rapid responders at the patient’s residence, providing appropriate care when a palliative emergency arises ideally with back-up phone support from a suitable medical practitioner or palliative care service. Patterson et al.’s 30 study piloted a programme where paramedics had access to medical oversight from a dedicated ambulance service online medical physician at all times. Establishing liaison points like this could act as a key enabler in future palliative paramedicine practice, offering paramedics greater confidence and certainty to treat palliative patients during out-of-hours calls with the reassurance of multidisciplinary back-up.

Targeted palliative care education and training for paramedics was another key enabler identified in the review for improving paramedics’ capacity to deliver palliative and end-of-life care in the community. Paramedics frequently witness patients dying in their homes. However, findings from a 2021 study recognise existing education and system resources have largely failed to provide paramedics with the necessary tools to provide grief support to family members and others who are suddenly bereaved following a palliative emergency. 49 Increasing paramedics’ comfort and capacity for providing grief support, in addition to other core palliative care skills, will require an array of educational methodologies. Innovative models that focus on enabling paramedics to broaden their role as emergency clinicians providing community-based palliative and end-of-life care are already emerging. Some of these include educational partnerships with grief experts and other health professionals specialising in palliative care, 50 as well as clinical placements for health professionals in palliative care services. 51 These types of initiatives would need to be broadly integrated across ambulance service training programmes to better equip paramedics to deliver palliative and end-of-life care in the community.

Establishing a patient’s goals of care is regarded as a central component of best-practice palliative care, 52 and documented wishes were identified as a key enabler for paramedics to facilitate palliative care pathways in community-based settings. However, paramedics face ongoing difficulties in accessing, interpreting and implementing medical wishes, particularly when family discordance is apparent. Electronic palliative care coordination systems were proposed by one study as a potential solution. Providing paramedics with point of care access to an integrated medical record that is used across the health system for a particular district, including documentation about a patient’s palliative care plans where applicable, could significantly reduce documentation accessibility issues for paramedics. Further, such initiatives may foster stronger communication channels between ambulance services and other healthcare providers.

Overwhelmingly, participants wanted to facilitate a natural death for palliative patients and avoid aggressive pathways of care where possible. Accordingly, this requires skilled communication from paramedics to negotiate palliative approaches and alternative care trajectories with patients and their families. Fear of litigation is a major barrier preventing paramedics from pursuing a palliative pathway, especially when avoiding hospitalisation in favour of a home-based death for patients with no clear documentation. End-of-life care clinical practice guidelines were identified as a key enabler to standardising practice for paramedics, in addition to minimising the existing medico-legal ambiguity associated with paramedics’ provision of palliative care. These findings are supported by broader literature highlighting the clinical protocol-driven nature of paramedic practice.5,12,53

Paramedic autonomy of practice was also explored within the included studies. Stone et al.’s 34 study reported 26% of paramedic participants exercised their own judgement to withhold or end resuscitation on a terminal patient in recent times. This study raises the important question: how do paramedics balance individual judgement with clinical practice guideline adherence in precarious end-of-life situations? In these circumstances clinical back-up from ambulance appointed medical physicians could again offer paramedics greater certainty to adopt a palliative approach to care.

Importantly, none of the included studies investigated the efficacy of implementing a palliative care clinical practice guideline on paramedic scope of practice or patient outcomes. Furthermore, no study quantified the economic cost of their intervention. Nor were perspectives of other health professionals on the role of paramedics delivering palliative and end-of-life care investigated in any of the included studies. Given the significant investment required to upskill paramedics to deliver best-practice palliative and end-of-life care, in addition to the need to better integrate multidisciplinary approaches to palliative paramedicine, clinical practice guideline implementation studies, broader healthcare professional perspective analysis and health economic evaluations are warranted, and this highlights a current gap in empirical research on the topic.

Strengths and limitations

A key strength of this review was its systematic approach to identifying and synthesising empirical studies. The review was rigorously carried out, including a search of four databases and a comprehensive narrative synthesis of themes. Two independent researchers conducted the screening, data extraction and quality appraisal of studies, therefore reducing subjective selection bias. Some limitations were also present. Some of the qualitative studies were based on small sample sizes, which increased the risk of sample bias and reduced the likelihood of saturation of themes. Furthermore, only non-experimental studies were retrieved, despite the integrative approach. However, most of the included studies were considered of high quality, and the risk of any studies being overlooked was minimised due to no date limitations being applied to the search strategy.

Conclusion

Integrating palliative and end-of-life care into the provision of paramedic practice has gained considerable global attention in recent years. Overall, this review demonstrates the important role paramedics can play in facilitating home-based death and reducing avoidable hospital admissions. The known scope of palliative paramedicine was established, barriers and enablers of practice identified, and the perspectives of multiple stakeholders explored to reveal three key themes: broadening the traditional role, understanding patient wishes and supporting families.

Our findings have novel implications for a multitude of stakeholders. Paramedics are a highly skilled workforce capable of filling a gap in palliative and end-of-life care provision to people in their homes, especially after-hours for palliative emergencies when other community palliative care services are unavailable. However, a multi-faceted approach to palliative paramedicine is needed to enable optimal care. This review will be helpful to policy makers when developing models of integration between palliative care services. If they have not done so already, ambulance services should broaden their clinical practice to include palliative care specific guidelines, accompanied by education and practical training addressing the complexities and legalities of end-of-life care. Finally, palliative care researchers have scope to investigate wider health professional perspectives on the paramedic’s role in palliative care, as well as the efficacy and cost-effectiveness of targeted quality improvement programmes.

Footnotes

Authorship contributions: The search strategy was developed by MJ, PV, JC and PB in consultation with a specialist librarian. MJ carried out the search, and together with PV, screened the articles. MJ performed the data extraction and quality appraisal, which was cross-checked by PV. MJ conducted the thematic analysis, which was cross-checked by PV, and drafted the manuscript. All authors critically revised the manuscript, making substantial contributions and approving the final version.

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: MJ received personal PhD funding from the HammondCare Foundation and Sydney Vital Translational Cancer Research Centre.

ORCID iD: Madeleine L Juhrmann  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5500-4330

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5500-4330

References

- 1. World Health Organization. Palliative Care Key Facts, https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/palliative-care (2020). Accessed on 20 January 2021.

- 2. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Palliative care services in Australia. Canberra, Australia: AIHW, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sullender RT, Selenich SA. Financial considerations of hospital-based palliative care. Research Triange Park, NC: RTI Press, 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gomes B, Higginson IJ, Calanzani N, et al. Preferences for place of death if faced with advanced cancer: a population survey in England, Flanders, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Portugal and Spain. Ann Oncol 2012; 23: 2006–2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. O’Hara R, Johnson M, Siriwardena A, et al. A qualitative study of systemic influences on paramedic decision making: care transitions and patient safety. J Health Serv Res Policy 2015; 20: 45–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Long D. Paramedic delivery of community-based palliative care: an overlooked resource? Prog Palliat Care 2019; 27: 289–290. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Oosterwold J, Sagel D, Berben S, et al. Factors influencing the decision to convey or not to convey elderly people to the emergency department after emergency ambulance attendance: a systematic mixed studies review. BMJ Open 2018; 8. e021732–e021732. 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-021732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Al-Shaqsi S. Models of international emergency medical service (EMS) systems. Oman Med J 2010; 25: 320–323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wiese CHR, Bartels UE, Marczynska K, et al. Quality of out-of-hospital palliative emergency care depends on the expertise of the emergency medical team—a prospective multi-centre analysis. Support Care Cancer 2009; 17: 1499–1506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. McCormick G, Thompson S. The provision of palliative and end-of-life care by paramedics in New Zealand communities: a review of international practice and the New Zealand context. Whitireia Nurs Health J 2019; 26: 51–57. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pentaris P, Mehmet N. Attitudes and perceptions of paramedics about end-of-life care: a literature review. J Paramed Pract 2019; 11: 206–215. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lamba S, Schmidt T, Chan G, et al. Integrating palliative care in the out-of-hospital setting: four things to jump-start an EMS-palliative care initiative. Prehosp Emerg Care 2013; 17: 511–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Whittemore R, Knafl K. The integrative review: updated methodology. J Adv Nurs 2005; 52: 546–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009; 6: e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Veritas Health Innovation. Covidence systematic review software. Melbourne, Australia: Veritas Health Innovation. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Büchter RB, Weise A, Pieper D. Development, testing and use of data extraction forms in systematic reviews: a review of methodological guidance. BMC Med Res Methodol 2020; 20: 259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Carter AJE, Arab M, Harrison M, et al. Paramedics providing palliative care at home: a mixed-methods exploration of patient and family satisfaction and paramedic comfort and confidence. CJEM 2019; 21: 513–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Teno JM, Clarridge BR, Casey V, et al. Family perspectives on end-of-life care at the last place of care. JAMA 2004; 291: 88–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Walker M, Jensen JL, Leroux Y, et al. The impact of intense airway management training on paramedic knowledge and confidence measured before, immediately after and at 6 and 12 months after training. Emerg Med J 2013; 30: 334–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hoare S, Kelly MP, Prothero L, et al. Ambulance staff and end-of-life hospital admissions: a qualitative interview study. Palliat Med 2018; 32: 1465–1473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jensen JL, Travers AH, Marshall EG, et al. Insights into the implementation and operation of a novel paramedic long-term care program. Prehosp Emerg Care 2014; 18: 86–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kirk A, Crompton P, Knighting K, et al. Paramedics and their role in end-of-life care: perceptions and confidence. J Paramed Pract 2017; 9: 71–79. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mason SR, Ellershaw JE. Preparing for palliative medicine; evaluation of an education programme for fourth year medical undergraduates. Palliat Med 2008; 22: 687–692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Leibold A, Lassen C, Lindenberg N, et al. Is every life worth saving: does religion and religious beliefs influence paramedic’s end-of-life decision-making? A prospective questionnaire-based investigation. Indian J Palliat Care 2018; 24: 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lord B, Andrew E, Henderson A, et al. Palliative care in paramedic practice: a retrospective cohort study. Palliat Med 2019; 33: 445–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lord B, Récoché K, O’Connor M, et al. Paramedics’ perceptions of their role in palliative care: analysis of focus group transcripts. J Palliat Care 2012; 28: 36–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. McGinley J, Waldrop DP, Clemency B. Emergency medical services providers’ perspective of end-of-life decision making for people with intellectual disabilities. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil 2017; 30: 1057–1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mott C, Herbert A, Malcolm K, et al. Emergencies in pediatric palliative care: a survey of ambulance officers to understand the interface between families and ambulance services. J Palliat Med 2020; 23(12): 1649–1652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Murphy-Jones G, Timmons S. Paramedics’ experiences of end-of-life care decision making with regard to nursing home residents: an exploration of influential issues and factors. Emerg Med J 2016; 33: 722–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Patterson R, Standing H, Lee M, et al. Paramedic information needs in end-of-life care: a qualitative interview study exploring access to a shared electronic record as a potential solution. BMC Palliat Care 2019; 18: 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Pease N, Sundararaj J, O’Brian E, et al. Paramedics and serious illness: communication training. BMJ Support Palliat Care. Epub ahead of print 15 November 2019. DOI: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2018-001734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rogers IR, Shearer FR, Rogers JR, et al. Paramedics’ perceptions and educational needs with respect to palliative care. Australas J Paramed 2015; 12(5): 10.33151/ajp.12.5.218 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Eager K, Senior K, Fildes D, et al. The Palliative Care Evaluation Tool Kit: a compendium of tools to aid in the evaluation of palliative care projects. Centre for Health Service Development – CHSD, Wollongong, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Stone S, Abbott J, McClung C, et al. Paramedic knowledge, attitudes, and training in end-of-life care. Prehosp Disaster Med 2009; 24: 529–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Robinson K, Sutton S, von Gunten C, et al. Assessment of the education for physicians on end-of-life care (EPEC™) project. J Palliat Med 2004; 7: 637–645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Surakka L, Peake M, Kiljunen M, et al. Preplanned participation of paramedics in end-of-life care at home: a retrospective cohort study. Palliat Med 2021; 35(3): 584–591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Swetenham K, Grantham H, Glaetzer K. Breaking down the silos: collaboration delivering an efficient and effective response to palliative care emergencies. Prog Palliat Care 2014; 22: 212–218. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Taghavi M, Simon A, Kappus S, et al. Paramedics experiences and expectations concerning advance directives: a prospective, questionnaire-based, bi-centre study. Palliat Med 2011; 26: 908–916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Waldrop D, Clemency B, Lindstrom H, et al. “We are strangers walking into their life-changing event”: how prehospital providers manage emergency calls at the end of life. J Pain Symptom Manage 2015; 50(3):328–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Waldrop D, Clemency B, Maguin E, et al. Preparation for frontline end-of-life care: exploring the perspectives of paramedics and emergency medical technicians. J Palliat Med 2014; 17(3): 338–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Waldrop D, Clemency B, Maguin E, et al. Prehospital providers’ perceptions of emergency calls near life’s end. Am J Hosp Palliat Med 2015; 32: 198–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Waldrop D, McGinley J, Dailey M, et al. Decision-making in the moments before death: challenges in prehospital care. Prehosp Emerg Care 2019; 23: 356–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Wiese C, Taghavi M, Lindenberg N, et al. Paramedics’ ‘end-of-life’ decision making in palliative emergencies. J Paramed Pract 2012; 4: 413–419. [Google Scholar]