Abstract

It has been shown in enterobacteria that mutations in ampD provoke hyperproduction of chromosomal β-lactamase, which confers to these organisms high levels of resistance to β-lactam antibiotics. In this study, we investigated whether this genetic locus was implicated in the altered AmpC β-lactamase expression of selected clinical isolates and laboratory mutants of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. The sequences of the ampD genes and promoter regions from these strains were determined and compared to that of wild-type ampD from P. aeruginosa PAO1. Although we identified numerous nucleotide substitutions, they resulted in few amino acid changes. The phenotypes produced by these mutations were ascertained by complementation analysis. The data revealed that the ampD genes of the P. aeruginosa mutants transcomplemented Escherichia coli ampD mutants to the same levels of β-lactam resistance and β-lactamase expression as wild-type ampD. Furthermore, complementation of the P. aeruginosa mutants with wild-type ampD did not restore the inducibility of β-lactamase to wild-type levels. This shows that the amino acid substitutions identified in AmpD do not cause the altered phenotype of AmpC β-lactamase expression in the P. aeruginosa mutants. The effects of AmpD inactivation in P. aeruginosa PAO1 were further investigated by gene replacement. This resulted in moderate-basal-level and hyperinducible expression of β-lactamase accompanied by high levels of β-lactam resistance. This differs from the stably derepressed phenotype reported in AmpD-defective enterobacteria and suggests that further change at another unknown genetic locus may be causing total derepressed AmpC production. This genetic locus could also be altered in the P. aeruginosa mutants studied in this work.

Most strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa produce an inducible, chromosomally encoded AmpC β-lactamase (24, 33, 34) belonging to molecular class C (1, 15) and to functional group 1 (3). Usually this enzyme is expressed at very low levels, but β-lactam inducers can raise these levels (23, 40). In the course of therapy, β-lactam antibiotics can select P. aeruginosa mutants that overproduce AmpC in the absence of inducers. Because these strains are resistant to most antipseudomonal penicillins and cephalosporins, treatment failure can result (26). Three phenotypes of altered AmpC expression have been found among clinical isolates of P. aeruginosa. They are moderate basal levels and constitutive β-lactamase expression, moderate basal levels and hyperinducible β-lactamase production, and high basal levels and constitutive β-lactamase expression (stably derepressed) (4, 34).

Chromosomal AmpC β-lactamases are also ubiquitous in enterobacteria, with the exception of salmonellae, and are inducible in all but Escherichia coli and shigellae (26). In species such as Citrobacter freundii and Enterobacter cloacae, three genes are involved in AmpC induction, a process that is intimately linked to peptidoglycan recycling (31). These genes are ampR, which encodes a transcriptional regulator of the LysR family; ampD, which encodes a cytosolic N-acetyl-anhydromuramyl-l-alanine amidase and specifically hydrolyzes 1,6-anhydromuropeptide; and ampG, which encodes a transmembrane protein and functions as a permease for 1,6-anhydromuropeptide, the signal molecule for induction of AmpC expression (6, 10, 12, 13, 17). Inactivation of ampD results in the cytoplasmic accumulation of 1,6-anhydromuropeptide and constitutive overproduction of AmpC (6, 12, 13, 21). In enterobacteria, as in P. aeruginosa, three phenotypes of altered AmpC expression have been associated with β-lactam resistance, and two of these phenotypes have been linked to mutations in ampD (2, 7, 16, 18, 34, 39).

The inducible expression of AmpC in P. aeruginosa is also under the control of the AmpR and AmpD regulators (19, 27). A putative ampG gene in P. aeruginosa PAO1 has been cloned recently and has been characterized by our group as well (T. Y. Langaee and A. Huletsky, Abstr. 97th Gen. Meeting Am. Soc. Microbiol., abstr. A-3, p. 1, 1997). Therefore, the genetic system which controls AmpC expression in P. aeruginosa appears to be similar to that of enterobacteria. However, the mutations which lead to the altered expression of AmpC in P. aeruginosa have not yet been identified. The aim of this study was to determine the genetic locus responsible for derepressed AmpC in P. aeruginosa by sequencing the ampD genes of selected laboratory mutants and clinical isolates having various levels of β-lactamase expression and comparing their sequences to that of wild-type ampD. We also report the results of studies of E. coli ampD mutants complemented by the ampD genes of these derepressed P. aeruginosa mutants.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

The strains and plasmids used in this study are described in Tables 1 and 2. E. coli strains JRG582 and STC172 and plasmid pEC1C were kindly provided by S. T. Cole (Institut Pasteur, Paris, France). Plasmids pUCP24 and pUCP26 (42) and plasmid pEX100T (36) were obtained from H. P. Schweizer (Colorado State University, Fort Collins). P. aeruginosa strains Ps50SAI+, Ps50SAI−con, M1405, M2297P, and M2297−con (5, 14, 22, 23) were kindly provided by D. M. Livermore (St. Bartholomew's and the Royal London School of Medicine and Dentistry, London, United Kingdom). Strain Ps50SAI−con is a spontaneous mutant of strain Ps50SAI−, which is an N-methyl-N′-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine (NTG) mutant of strain Ps50SAI+ (5). Strain PAO4254 (blaK) was provided from H. Matsumoto (Shinshu University School of Medicine, Matsumoto, Japan) and is a derivative of strain PAO1, which was obtained by NTG treatment as described by Matsumoto et al. (28). The altered phenotype of β-lactamase expression in strain PAO4254 has been associated with the genetic locus blaK (29) mapped to 26 min on the PAO1 chromosome (9). E. coli DH5α was used for transformation and propagation of recombinant plasmids.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristic(s)a | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| E. coli | ||

| DH5α | deoR supE44 Δ(lacZYA-argFV169) (φ80 dlacZΔM15) F−λ−hsdR17 (rK− mK+)recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thi-1 relA1 | 32 |

| JRG582 | Δ(ampDE)2 | 20 |

| STC172 | ampD11E+ | 11 |

| P. aeruginosa PAO1-D | ΔampD | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pEC1C | Cmr; ampC ampR from E. cloacae | 30 |

| pBGS19+ | Kmr; f1 Ori, lacPOZ | 38 |

| pUCP24 | Gmr; Ori, Ori1600, lacZα | 42 |

| pUCP26 | Tcr; Ori, Ori1600, lacZα | 42 |

| pEX100T | Cbr; T Ori, lacZα | 36 |

| pHUL4DE-2 | Kmr; ampDE region of P. aeruginosa PAO1 cloned into pBGS19+ | 19 |

| pHUL4DE-3 | Gmr; ampDE region of P. aeruginosa PAO1 cloned into pEX100T | This study |

| pHUL4DE-4 | Gmr; ampDE region of P. aeruginosa PAO1 containing the Gmr gene cloned into pEX100T | This study |

| pHUL4DE26 | Kmr; ampDE region of P. aeruginosa PAO1 cloned into pUCP26 | This study |

| pHUL4DE-M1 | Kmr; ampDE region of P. aeruginosa PAO4254 cloned into pBGS19+ | This study |

| pHUL4DE-M2 | Kmr; ampDE region of P. aeruginosa Ps50SAI+ cloned into pBGS19+ | This study |

| pHUL4DE-M3 | Kmr; ampDE region of P. aeruginosa Ps50SAI−con cloned into pBGS19+ | This study |

| pHUL4DE-M4 | Kmr; ampDE region of P. aeruginosa M1405 cloned into pBGS19+ | This study |

| pHUL4DE-M5 | Kmr; ampDE region of P. aeruginosa M2297P cloned into pBGS19+ | This study |

| pHUL4DE-M6 | Kmr; ampDE region of P. aeruginosa M2297−con cloned into pBGS19+ | This study |

Cb, carbenicillin; Cm, chloramphenicol; Gm, gentamicin; Km, kanamycin; Tc, tetracycline.

TABLE 2.

MICs of β-lactam antibiotics and specific activities of AmpC in P. aeruginosa and its mutant strains

| P. aeruginosa strain | β-Lactamase inducibility | Derivation | Reference(s) | MIC (μg/ml)

|

β-Lactamase activitya

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ampicillin | Cefotaxime | Noninduced | Inducedb | ||||

| PAO1 | Low basal level, inducible | Wild type | 512 | 32 | 7 ± 0.5 | 687 ± 32 | |

| PAO4254 (blaK) | Moderate basal level, hyperinducible | Laboratory | 29 | 2,048 | 32 | 80 ± 3 | 3,100 ± 96 |

| Ps50SAI+ | Low basal level, inducible | Clinical isolate | 5, 23 | 256 | 32 | 6 ± 0.4 | 1,300 ± 90 |

| Ps50SAI−con | High basal level, stably derepressed | Spontaneous mutant of Ps50SAI− | 14, 23 | 2,048 | 512 | 3,780 ± 150 | 5,900 ± 220 |

| M1405 | High basal level, stably derepressed | Clinical isolate | 22, 23 | 4,096 | 512 | 10,550 ± 350 | 12,650 ± 400 |

| M2297P | Low basal level, inducible | Pretherapy clinical isolate | 23 | 512 | 16 | 6 ± 0.2 | 1,840 ± 80 |

| M2297−con | High basal level, stably derepressed | Posttherapy clinical isolate | 23 | 2,048 | 512 | 8,200 ± 300 | 9,330 ± 320 |

Nanomoles of nitrocefin hydrolyzed per minute per milligram of protein.

Induction was carried out with 50 μg of cefoxitin/ml for 2 h.

All of the strains were grown in tryptic soy broth (TSB; Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) and on tryptic soy agar plates. When required, 100 μg of ampicillin/ml, 50 μg of kanamycin/ml, 30 μg of chloramphenicol/ml, 15 or 30 μg of tetracycline/ml, 200 μg of gentamicin/ml, and 4 or 50 μg of cefoxitin/ml (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) were added. Nitrocefin was obtained from Oxoid (Nepean, Ontario, Canada). T4 DNA ligase and the restriction endonucleases were obtained from New England Biolabs (Mississauga, Ontario, Canada). Recombinant DNA techniques were performed essentially by standard procedures (32). Plasmid DNA was isolated by using both the Wizard MiniPreps DNA purification system (Promega, Madison, Wis.) and Plasmid Midi kit (Qiagen, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada). Restriction fragments and PCR products were recovered from agarose gels with a QIAquick gel extraction kit (Qiagen). Restriction endonuclease digestions were performed under conditions recommended by the manufacturers.

Cloning and sequencing of the ampD and ampE genes from P. aeruginosa mutants.

Two oligonucleotide primers (AmpD-14 and AmpD-15) located upstream and downstream of the P. aeruginosa PAO1 ampDE operon were designed from its published sequence (19). Oligonucleotides were synthesized on a 394 DNA/RNA synthesizer (PE Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.). The sequences of these primers were as follows: AmpD-14, 5′-GGGAATTCCTTTCCTCGAAGCATGTCG-3′; and AmpD-15, 5′-GGGATAGAGTACGGTCTTC-3′. Amplification was performed with lysates of P. aeruginosa mutants (Table 2) prepared as previously described (19), with Pfu DNA polymerase (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.) in a Perkin-Elmer DNA thermal cycler. The cycling parameters were as follows: 95°C for 5 min and then 30 cycles of 94°C for 1 min, 54°C for 2 min, and 72°C for 3 min. Two independent PCRs were performed for each P. aeruginosa lysate. The amplified DNA fragments were cloned into the SmaI site of the pBGS19+ vector (38), and the resulting recombinant plasmids were named pHUL4DE-M1 to -M6, according to the strain origin, and transformed in E. coli DH5α (Table 1). One transformant from each PCR was selected.

Both strands of cloned DNA were sequenced by dideoxy nucleotide sequencing (35). The ABI PRISM dye terminator cycle sequencing kit, supplied with Ampli Taq DNA polymerase FS (PE Applied Biosystems) on a 373 DNA sequencer (PE applied Biosystems), was used. Universal, reverse, and internal oligonucleotide (AmpD-6 [5′-GCTACCAGGGCCACTGC-3′]) primers were used for sequencing. The dye terminator cycle sequencing and the synthesis of oligonucleotides were performed by the DNA Synthesis and Analysis Laboratory of Laval University (Pavillon Marchand, Université Laval, Ste-Foy, Québec, Canada).

Construction of the P. aeruginosa AmpD-defective mutant.

The gene replacement technique described by Schweizer (36) was used for construction of the P. aeruginosa PAO1 AmpD-defective mutant. First, the 2,091-bp HincII fragment containing ampD from the pHUL4DE-1 plasmid (19) was cloned into the SmaI site of pEX100T (36) to generate the pHUL4DE-3 plasmid. To construct the insertion plasmid, pHUL4DE-4, the ampD gene on pHUL4DE-3 was mutated by insertion of the 1,650-bp DraI fragment of pUCP24 (42) containing the Gmr-encoding gene into the unique NruI site in the ampD gene. The pHUL4DE-4 plasmid was transformed in the E. coli mobilizing strain S17-1 (37). This plasmid was then mobilized in P. aeruginosa PAO1, and recipient cells in which the ampD::Gmr gene had replaced the chromosomal ampD gene were selected by the method of Schweizer and Hoang (36).

To confirm the replacement of the ampD gene by the ampD::Gmr gene, chromosomal DNA from strain PAO1 and the PAO1 Gmr strain harboring a derepressed phenotype of AmpC expression was isolated and digested with PstI. Southern blot analysis of the digested chromosomal DNA fragments was performed by using the 1,379-bp internal ampD fragment from pHUL4DE-1 as a probe (data not shown).

Susceptibility test.

MICs of each antibiotic were determined by the microdilution method in TSB with an inoculum of 105 CFU per ml in multiple-well plates. The MIC was defined as the lowest concentration of antibiotic preventing growth after 18 to 24 h of incubation at 37°C.

Induction of β-lactamase.

Bacterial cells containing plasmids were grown in media containing appropriate plasmid selections to an optical density of 0.8 U at 420 nm and induced with cefoxitin. Cells were washed once and then resuspended in 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0). Crude extracts were prepared by sonication as previously described (41).

β-Lactamase assays.

β-Lactamase activity was determined by spectrophotometry following hydrolysis of nitrocefin, as previously described (41). Specific activity was expressed in nanomoles of nitrocefin hydrolyzed per minute per milligram of protein. All induction experiments were performed in duplicate, and the results presented are averages of two determinations.

Computer techniques.

Sequence analysis and alignment were performed by using the GCG software package of the University of Wisconsin Genetics Computer Group.

RESULTS

Phenotype of AmpC expression in P. aeruginosa mutants.

The P. aeruginosa strains used in this study exhibited three different phenotypes of β-lactamase expression and β-lactam susceptibility (Table 2) and were taken from clinical and laboratory sources. Strains Ps50SAI+ and M2297P showed the same phenotype of enzyme expression as wild-type PAO1, with low-basal-level and inducible β-lactamase production and low MICs of ampicillin and cefotaxime (5, 23). Strain PAO4254 had moderate-basal-level and hyperinducible β-lactamase production, and the MIC of ampicillin (fourfold), but not of cefotaxime, was higher. Finally, strains Ps50SAI−con, M1405, and M2297−con exhibited high-basal-level and constitutive β-lactamase production (stably derepressed) and a high level of resistance to both ampicillin and cefotaxime (4- to 32-fold increase in MIC) (14, 22, 23).

Sequence analysis of the ampD gene from P. aeruginosa mutants.

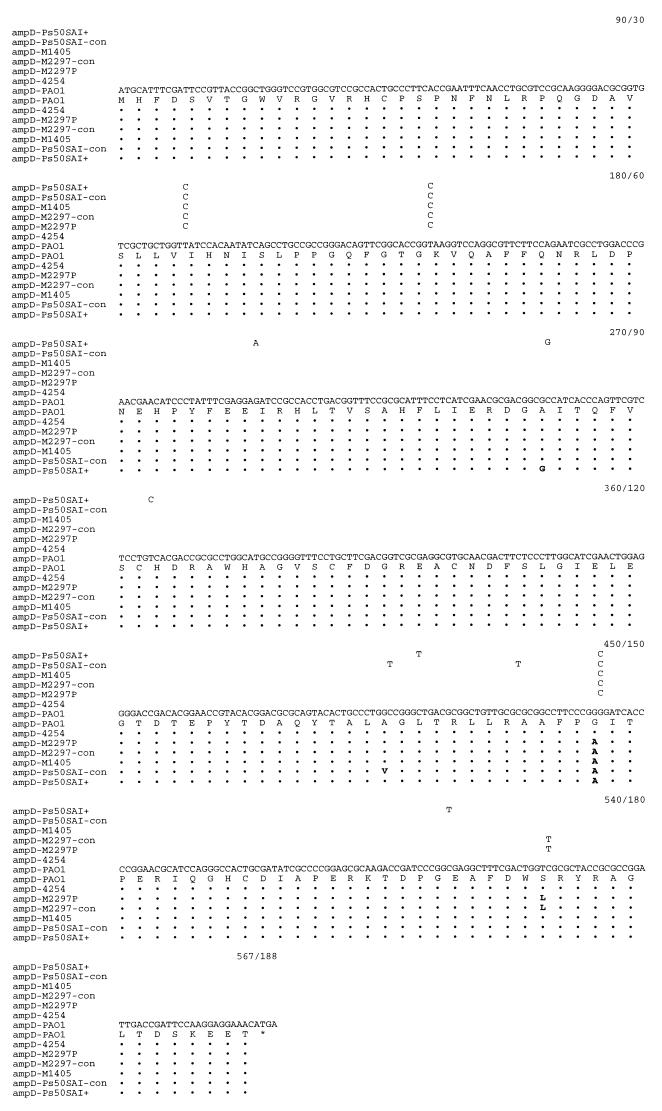

Figure 1 shows the nucleotide sequences and translated amino acids of the ampD gene from the P. aeruginosa mutants. When compared with wild-type PAO1, no nucleotide substitution could be identified within the promoter regions in any of the strains studied (data not shown). Eleven nucleotide substitutions, resulting in only four amino acid changes at positions 85, 136, 148, and 175, were found in the structural ampD genes. Two amino acid substitutions were specific to one strain: Ala-85 for Gly was unique to strain Ps50SAI+, and Ala-136 for Val was unique to strain Ps50SAI−con. The last two mutations were found in more than one strain: the Gly-148-for-Ala substitution was identified in strains M2297−con, M2297P, Ps50SAI+, and Ps50SAI−con, and the Ser-175-for-Leu change was found in both M2297−con and M2297P.

FIG. 1.

Sequence of the P. aeruginosa PAO1 wild-type ampD gene (19) aligned with the sequences of the ampD genes from six different clinical isolates or laboratory mutant strains of P. aeruginosa. The deduced amino acid sequences are shown underneath the nucleotides. Only the nucleotide and amino acid differences from wild-type ampD sequence are shown. The amino acid changes for mutants are indicated in boldface. The numbers at the end of each line represent the last nucleotide and amino acid, respectively.

Complementation of E. coli ampD mutants.

To determine the ability of the ampD genes of the P. aeruginosa mutants to complement E. coli ampD mutations, plasmids pHUL4DE-M1 to -M6 (carrying the ampDE region from the various P. aeruginosa mutants [Table 1]) were transformed in the moderate-basal-level and hyperinducible E. coli STC172 ampD mutant (11) containing plasmid pEC1C. Plasmid pEC1C carries the ampC and ampR genes of E. cloacae (30). Induction assays and MIC determination (Table 3) revealed that both wild-type ampD and ampD genes from mutant strains transcomplemented the E. coli ampD mutant, resulting in low levels of β-lactam resistance and wild-type β-lactamase expression (low basal level and inducibility). The basal and induced levels of enzyme activity for cells containing ampD from mutants, however, were in general either slightly lower or slightly higher than those for cells containing wild-type ampD.

TABLE 3.

MICs of β-lactam antibiotics and specific activities of E. cloacae AmpC in E. coli ampD mutants containing the ampDE genes of P. aeruginosa mutant

| Strain and plasmids | Relevant genotype | MIC (μg/ml)

|

β-Lactamase activitya

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ampicillin | Cefotaxime | Noninduced | Inducedb | ||

| STC172/pEC1C/pBGS19+c | ampC+ ampR+/ampD11E+ | 1,024 | 32 | 3,260 ± 190 | 23,490 ± 1,240 |

| STC172/pEC1C/pHUL4DE-2c | ampC+ ampR+/ampDEPAO1 | 128 | 1 | 113 ± 5 | 2,930 ± 199 |

| STC172/pEC1C/pHUL4DE-M1 | ampC+ ampR+/ampDE4254 | 128 | <2 | 32 ± 1 | 2,000 ± 60 |

| STC172/pEC1C/pHUL4DE-M2 | ampC+ ampR+/ampDEPs50SAI+ | 128 | <2 | 30 ± 1 | 200 ± 10 |

| STC172/pEC1C/pHUL4DE-M3 | ampC+ ampR+/ampDEPs50SAI−con | 512 | <2 | 20 ± 1 | 900 ± 4 |

| STC172/pEC1C/pHUL4DE-M4 | ampC+ ampR+/ampDEM1405 | 256 | <2 | 400 ± 20 | 800 ± 40 |

| STC172/pEC1C/pHUL4DE-M5 | ampC+ ampR+/ampDEM2297P | 256 | <2 | 20 ± 0.7 | 832 ± 50 |

| STC172/pEC1C/pHUL4DE-M6 | ampC+ ampR+/ampDEM2297P−con | 256 | <2 | 134 ± 6 | 2,100 ± 90 |

| JRG582/pEC1C/pBGS19+c | ampC+ ampR+/Δ(ampDE)2 | 1,024 | 64 | 103,280 ± 6,230 | 109,400 ± 7,110 |

| JRG582/pEC1C/pHUL4DE-2c | ampC+ ampR+/ampDEPAO1 | 128 | 8 | 414 ± 39 | 7,050 ± 400 |

| JRG582/pEC1C/pHUL4DE-M5 | ampC+ ampR+/ampDEM2297P | 256 | <2 | 60 ± 4 | 1,130 ± 70 |

| JRG582/pEC1C/pHUL4DE-M6 | ampC+ ampR+/ampDEM2297P−con | 256 | <2 | 105 ± 8 | 1,770 ± 80 |

Nanomoles of nitrocefin hydrolyzed per minute per milligram of protein.

Induction was carried out with 4 μg of cefoxitin/ml for 1 h.

Data from Langaee et al. (19).

Plasmids pHULDE-M5 and pHULDE-M6 containing the respective ampDE regions of strains M2297P and M2297−con were also transformed in the stably derepressed E. coli JRG582 ampD deletant containing plasmid pEC1C. The data showed that they both transcomplemented the ampD deletion to low β-lactam resistance and low basal levels of β-lactamase expression and inducibility. The basal and induced levels of enzyme activity in cells containing ampD from mutants were four- to sixfold lower, however, than those of cells containing wild-type ampD.

Complementation of the P. aeruginosa mutants with wild-type ampD.

The pHUL4DE26 plasmid (carrying the wild-type ampDE region of P. aeruginosa PAO1) was transformed in the one hyperinducible and three derepressed P. aeruginosa mutants to determine the capacity of wild-type ampD to transcomplement their mutations. This plasmid was constructed by cloning the 2.6-kb EcoRI fragment of plasmid pHUL4DE-PH (19) into the EcoRI site of plasmid pUCP26 (42). As can be seen in Table 4, the basal and induced levels of enzyme activity as well as the MICs of ampicillin and cefotaxime for mutant cells containing plasmid pHUL4DE26 were comparable to those of cells carrying either the control plasmid pUCP26 or no plasmid.

TABLE 4.

MICs of β-lactam antibiotics and specific activities of AmpC in P. aeruginosa mutants carrying wild-type ampDE and in AmpD-defective mutant

| Strain and plasmid | MIC (μg/ml)

|

β-Lactamase activitya

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ampicillin | Cefotaxime | Noninduced | Inducedb | |

| PAO1 | 512 | 32 | 7 ± 0.5 | 687 ± 32 |

| PAO1-D | 4,096 | 1,024 | 256 ± 14 | 5,560 ± 239 |

| PAO4254 | 2,048 | 32 | 80 ± 3 | 3,100 ± 90 |

| PAO4254/pUCP26 | 1,024 | 32 | 92 ± 5 | 2,875 ± 158 |

| PAO4254/pHUL4DE26 | 1,024 | 32 | 83 ± 4 | 2,288 ± 170 |

| Ps50SAI−con | 2,048 | 256 | 3,780 ± 150 | 5,900 ± 220 |

| Ps50SAI−con/pHUL4DE26 | 1,024 | 512 | 2,870 ± 192 | 3,397 ± 200 |

| M1405 | 4,096 | 512 | 10,550 ± 350 | 12,650 ± 400 |

| M1405/pHUL4DE26 | 2,048 | 512 | 7,286 ± 393 | 8,931 ± 518 |

| M2297−con | 2,048 | 512 | 8,200 ± 300 | 9,330 ± 320 |

| M2297−con/pHUL4DE26 | 1,024 | 512 | 6,949 ± 324 | 6,834 ± 513 |

Nanomoles of nitrocefin hydrolyzed per minute per milligram of protein.

Induction was carried out with 50 μg of cefoxitin/ml for 2 h.

Phenotype of the P. aeruginosa AmpD-defective mutant.

To determine the effects of the ampD mutation on β-lactam resistance and β-lactamase expression, a P. aeruginosa AmpD-defective mutant was constructed by gene replacement. The data revealed (Table 4) that inactivation of AmpD caused 6- and 32-fold increases in the MIC of ampicillin and cefotaxime, respectively, as well as a moderate-basal-level and hyperinducible phenotype of β-lactamase expression.

DISCUSSION

It was our intention to determine whether or not genetic alterations leading to the derepressed phenotypes of P. aeruginosa mutants could be linked to ampD. Four mutants were used: three expressed high basal levels of β-lactamase constitutively (stably derepressed) (M1405, M2297−con, and Ps50SAI−con), and one had moderate-basal-level and hyperinducible β-lactamase expression (PAO4254). The low-basal-level and inducible parent strains M2297P, Ps50SAI+, and PAO1 of mutants M2297−con, Ps50SAI−con, and PAO4254, respectively, were also characterized. It was previously confirmed that these strains produce only the AmpC β-lactamase (5, 23). The susceptibilities of the strains to ampicillin and cefotaxime were generally related to the basal (noninduced) level of AmpC activity, which reflects the degree of derepression. Despite this, the MIC of cefotaxime for strain PAO4254 which has a moderate basal level of enzyme activity (11-fold increase) was not higher than that of the low-basal-level wild-type strain PAO1, despite a 4-fold increase in the MIC of ampicillin. However, the data showed that an increase in the MIC of cefotaxime was observable only in strains with a stably derepressed phenotype, with a greater than 35-fold increase in the basal level of enzyme activity. This can be explained by the lower Vmax of AmpC for this antibiotic compared to that for ampicillin (25, 33).

Many substitutions were identified in the nucleotide and translated amino acid sequences of the ampD gene from the various P. aeruginosa mutants (Fig. 1). Some nucleotide substitutions which were present in both parent and mutant strains revealed that variations in the ampD gene sequences were strain dependent. More nucleotide changes were found in strains of the Ps50SAI series which could have resulted from the NTG treatment used to induce genetic changes (5). The Ser-175–Leu substitution in AmpD was specific to strains of the M2297 series, but since it was found in both strains M2297P and M2297−con, it cannot cause the stably derepressed phenotype of the latter strain. The Ala-136–Val substitution was unique to the stably derepressed strain Ps50SAI−con and could be associated with this phenotype. However, complementation studies showed that the ampDE locus of all of the strains studied transcomplemented the E. coli STC172 ampD mutation and E. coli JRG582 ampDE deletion to levels of susceptibility and enzyme activities both comparable to those of cells containing wild-type ampD. This strongly suggests that the ampD gene products of the derepressed strains have wild-type enzyme activity and cannot be at the origin of these phenotypes. The slight variations in the levels of enzyme activity among the different E. coli transformants could result from differences in codons due to the various nucleotide substitutions in ampD thus affecting the expression levels of this gene (8).

We also investigated whether the wild-type ampDE could complement mutations of the derepressed P. aeruginosa mutants and restore wild-type AmpC expression. The absence of complementation further confirms that mutations in these strains are not linked to the ampDE locus. The slight decreases in basal and induced levels of AmpC expression in P. aeruginosa mutants containing wild-type ampDE might result from overexpression of ampD, due to the presence of the pHUL4DE26 plasmid. Indeed, ampD encodes an N-acetyl-anhydromuramyl-l-alanine amidase which cleaves 1,6-anhydromuropeptide, the signal molecule for AmpC expression (10, 11, 14). An increase in AmpD would decrease the amount of 1,6-anhydromuropeptides in cells and reduce β-lactamase expression.

In enterobacteria, three out of four phenotypes of derepressed AmpC β-lactamase expression—hyperinducible (higher-basal-level and hyperinducible β-lactamase production), stably derepressed (high-basal-level and constitutive β-lactamase expression), and temperature sensitive (loss of inducibility at nonpermissive temperature)—have been associated with mutations in ampD (7, 16, 18, 39). The partially derepressed phenotypes (moderate-basal-level and hyperinducible β-lactamase expression) have not been associated with any alteration in ampD (39). Most mutations that completely inactivate AmpD and lead to stably derepressed phenotypes are caused by large deletions, but point mutations have also been associated with these phenotypes. We recently published an amino acid alignment of the AmpD proteins in which the conserved regions common to the AmpD proteins and cell wall hydrolases were highlighted (13, 19). According to the amino acid numbering of the AmpD proteins of this alignment, two of the point mutations (Val-37–Gly and Asp-169–Gly) identified in AmpD of stably derepressed mutants (39) are located beside highly conserved His-38 and Pro-170. Other mutations that give rise to hyperinducible phenotypes and partially inactivated AmpD activity have been located in other conserved regions of cell wall hydrolases (7, 16, 39). Two changes (Trp-99–Arg and Tyr-106–Asp) are located in the core region of these enzymes, while three others (Asp-125 for Gly, Asp-131 for Gly, and Ala-163 for Gly) are located outside of the core region (13, 19). In this study, contrary to what has been described in derepressed enterobacteria, all of the changes identified in AmpD of the P. aeruginosa mutants were associated with nonconserved amino acids (19). This can explain why, in these strains, AmpD has wild-type enzyme activity.

Since none of the mutations identified in ampD were associated with altered AmpC expression in the P. aeruginosa mutants, we investigated the effect of AmpD inactivation. An AmpD-defective mutant was constructed and was shown to exhibit a moderate-basal-level and hyperinducible β-lactamase expression which differs from the stably derepressed phenotype reported in enterobacteria (7, 16, 39). These data are in accordance with the recent work of Bagge et al. (N. Bagge, J. I. A. Campbell, O. Ciofu, T. Y. Langaee, A. Huletsky, and N. Høiby, Abstr. 99th Gen. Meeting Am. Soc. Microbiol., abstr. A-71, p. 15, 1999). Therefore, despite the close relationships among the various AmpC regulator genes (AmpR, AmpD, and AmpG) in P. aeruginosa and in enterobacteria (19, 27, 31; Langaee and Huletsky, Abstr. 97th Gen. Meeting Am. Soc. Microbiol., 1997), it seems that the induction systems of AmpC in these organisms are not exactly the same. In fact, the mutation frequency in P. aeruginosa is 10−7 for partial derepression, and it is 10−9 for full derepression, whereas in enterobacteria, the frequency of mutations for fully (stably) derepressed strains is 10−5 to 10−7 (26). Livermore (25) suggested that this difference could be due to the fact that in P. aeruginosa, the stably derepressed mutants may emerge via a second mutation in cells that are already partially derepressed. Data from Matsumoto also suggested that mutations in two loci in the PAO1 chromosome are necessary for complete derepression (H. Matsumoto, personal communication). Indeed, four loci on the PAO1 chromosome have been shown to affect AmpC induction (blaI, blaJ, blaK, and blaL) (9, 29). The blaI, blaJ, and blaK mutants have moderate-basal-level and hyperinducible β-lactamase expression, whereas the blaL mutant is noninducible (28; H. Matsumoto, personal communication). In this study, we showed that the blaK locus (in strain PAO4254) mapped to 26 min on the PAO1 chromosome (9) was not associated with ampD.

In this work, we clearly demonstrated that in some of the P. aeruginosa mutant strains studied, the derepressed phenotypes of AmpC expression were not associated with mutations in the ampDE locus. A recent study from Campbell et al. (4) also revealed that the altered AmpC expression in various isolates of P. aeruginosa from cystic fibrosis patients was not associated within the ampC-ampR locus. Therefore, although our data showed that inactivation of ampD results in partially derepressed AmpC expression, we suggest that further genetic change at another bla locus may be causing total derepressed AmpC production. This bla locus could also be involved in the derepressed phenotypes of some of the strains described in this study. The characterization of these bla loci is currently in progress.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank S. T. Cole for the gift of the E. coli strains and plasmids used for complementation work in this study and D. M. Livermore and H. Matsumoto for the gift of P. aeruginosa mutant strains. We also thank H. P. Schweizer for the gift of plasmids pUCP24, pUCP26, and pEX100T.

This work was supported by the Canadian Cystic Fibrosis Foundation and, in part, by the Canada's Networks of Centres of Excellence (CBDN).

REFERENCES

- 1.Ambler R P. The structure of β-lactamases. Philos Trans R Soc London Ser B. 1980;289:321–331. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1980.0049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bennett P M, Chopra I. Molecular basis of β-lactamase induction in bacteria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:153–158. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.2.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bush K, Jacoby G A, Medeiros A A. A functional classification scheme for β-lactamases and its correlation with molecular structure. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:1211–1233. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.6.1211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Campbell J I A, Ciofu O, Høiby N. Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from patients with cystic fibrosis have different β-lactamase expression phenotypes but are homogeneous in the ampC-ampR genetic region. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:1380–1384. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.6.1380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Curtis N A C, Orr D, Boulton M G, Ross G W. Penicillin-binding proteins of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Comparison of two strains differing in their resistance to β-lactam antibiotics. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1981;7:127–136. doi: 10.1093/jac/7.2.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dietz H, Pfeifle D, Wiedemann B. The signal molecule for β-lactamase induction in Enterobacter cloacae is the anhydromuramyl-pentapeptide. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:2113–2120. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.10.2113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ehrhardt A F, Sanders C C, Romero J R, Leser J S. Sequencing and analysis of four new Enterobacter ampD alleles. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:1953–1956. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.8.1953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gouy M, Gautier C. Codon usage in bacteria: correlation with gene expressivity. Nucleic Acids Res. 1982;10:7055–7074. doi: 10.1093/nar/10.22.7055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holloway B W, Zhang C. Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO. In: O'Brien S J, editor. Genetics maps. Locus maps of complex genomes. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. pp. 2.71–2.78. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Höltje J-V, Kopp U, Ursinus A, Wiedemann B. The negative regulator of β-lactamase induction AmpD is a N-acetyl-anhydromuramyl-l-alanine amidase. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1994;122:159–164. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1994.tb07159.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Honoré N, Nicolas M H, Cole S T. Regulation of enterobacterial cephalosporinase production: the role of a membrane-bound sensory transducer. Mol Microbiol. 1989;3:1121–1130. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1989.tb00262.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jacobs C, Huang L J, Bartowsky E, Normark S, Park J T. Bacterial cell wall recycling provides cytosolic muropeptides as effectors for β-lactamase induction. EMBO J. 1994;13:4684–4694. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06792.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jacobs C, Joris B, Jamin M, Klarsov K, VanBeeumen J, Mengin-Lecreulx D, van Heijenoort J, Park J T, Normark S, Frère J-M. AmpD, essential for both β-lactamase regulation and cell wall recycling, is a novel cytosolic N-acetylmuramyl-l-alanine amidase. Mol Microbiol. 1995;15:553–559. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jacobs J Y, Livermore D M, Davy K W M. Pseudomonas aeruginosa β-lactamase as a defence against azlocillin, mezlocillin and piperacillin. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1984;14:221–229. doi: 10.1093/jac/14.3.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jaurin B, Grundström T. AmpC cephalosporinase of E. coli K-12 has a different evolutionary origin from that of β-lactamase of the penicillinase type. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1981;78:4897–4901. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.8.4897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kopp U, Wiedemann B, Lindquist S, Normark S. Sequences of wild-type and mutant ampD genes of Citrobacter freundii and Enterobacter cloacae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:224–228. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.2.224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Korfmann G, Sanders C C. ampG is essential for high-level expression of AmpC β-lactamase in Enterobacter cloacae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1989;33:1946–1951. doi: 10.1128/aac.33.11.1946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Korfmann G, Sanders C C, Moland E S. Altered phenotypes associated with ampD mutations in Enterobacter cloacae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1991;35:358–364. doi: 10.1128/aac.35.2.358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Langaee T Y, Dargis M, Huletsky A. An ampD gene in Pseudomonas aeruginosa encodes a negative regulator of AmpC β-lactamase expression. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:3296–3300. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.12.3296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Langley D, Guest J R. Biochemical genetics of the alpha-keto acid dehydrogenase complexes of Escherichia coli K12: isolation and biochemical properties of deletion mutants. J Gen Microbiol. 1977;99:263–276. doi: 10.1099/00221287-99-2-263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lindberg F, Lindquist S, Normark S. Inactivation of the ampD gene causes semiconstitutive overproduction of the inducible Citrobacter freundii β-lactamase. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:1923–1928. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.5.1923-1928.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Livermore D M, Williams R J, Lindridge M A, Slack R C B, William J D. Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates with modified beta-lactamase inducibility: effects on beta-lactam sensitivity. Lancet. 1982;1:1466–1467. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(82)92474-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Livermore D M, Yang Y-J. β-Lactamase lability and inducer power of newer β-lactam antibiotics in relation to their activity against β-lactamase-inducibility mutants of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Infect Dis. 1987;155:775–782. doi: 10.1093/infdis/155.4.775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Livermore D M. Clinical significance of beta-lactamase induction and stable derepression in gram-negative rods. Eur J Clin Microbiol. 1987;6:439–445. doi: 10.1007/BF02013107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Livermore D M. β-Lactamases of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antibiot Chemother. 1991;44:215–220. doi: 10.1159/000420317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Livermore D M. β-Lactamases in laboratory and clinical resistance. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1995;8:557–584. doi: 10.1128/cmr.8.4.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lodge J, Busby S, Piddock L. Investigation of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa ampR gene and its role at the chromosomal ampC promoter. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1993;111:315–320. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1993.tb06404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matsumoto H, Ohta S, Kobayashi R, Terawaki Y. Chromosomal location of genes participating in the degradation of purines in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol Gen Genet. 1978;167:165–176. doi: 10.1007/BF00266910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Matsumoto H, Tazaki T. Chromosomal location of the genes participating in the formation of β-lactamase in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. In: Mitsuhashi S, editor. Drug resistance in bacteria. Tokyo, Japan: Japan Scientific Societies Press; 1982. pp. 207–211. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nicolas M-H, Honoré N, Jarlier V, Philippon A, Cole S T. Molecular genetic analysis of cephalosporinase production and its role in β-lactam resistance in clinical isolates of Enterobacter cloacae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1987;31:295–299. doi: 10.1128/aac.31.2.295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Normark S. β-Lactamase induction in Gram-negative bacteria is intimately linked to peptidoglycan recycling. Microb Drug Resist. 1995;1:111–114. doi: 10.1089/mdr.1995.1.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. pp. 1.21–1.101. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sanders C C. Chromosomal cephalosporinases responsible for multiple resistance to newer β-lactam antibiotics. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1987;41:573–593. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.41.100187.003041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sanders C C, Sanders W E., Jr β-Lactam resistance in gram-negative bacteria: global trends and clinical impact. Clin Infect Dis. 1992;15:825–839. doi: 10.1093/clind/15.5.824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sanger F, Nicklen S, Coulson A R. DNA sequencing with chain terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:5463–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schweizer H P, Hoang T T. An improved system for gene replacement and xylE fusion analysis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Gene. 1995;158:15–22. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00055-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Simon R, O'Connell M, Labes M, Pühler A. Plasmid vectors for the genetic analysis and manipulation of rhizobia and other gram-negative bacteria. Methods Enzymol. 1986;118:640–659. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(86)18106-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Spratt B G, Hedge P J, Teheesen S, Edelman A, Broome-Smith J K. Kanamycin-resistant vectors that are analogues of plasmids pUC8, pUC9, pEMBL8 and pEMBL9. Gene. 1986;41:337–342. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(86)90117-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stapleton P, Shannon K, Phillips I. DNA sequence differences of ampD mutants of Citrobacter freundii. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:2494–2498. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.11.2494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tausk F, Evans M E, Patterson L S, Federspiel C F, Stratton C W. Imipenem-induced resistance to antipseudomonal β-lactams in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1985;28:41–45. doi: 10.1128/aac.28.1.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Trépanier S, Prince A, Huletsky A. Characterization of the penA and penR genes of Burkholderia cepacia 249 which encode the chromosomal class A penicillinase and its LysR-type transcriptional regulator. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:2399–2405. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.11.2399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.West S E H, Schweizer H P, Dall C, Sample A K, Runyen-Janecky L J. Construction of improved Escherichia-Pseudomonas shuttle vectors derived from pUC18/19 and sequence of the region required for their replication in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Gene. 1994;148:81–86. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90237-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]