Abstract

In the present work, five novel non-fullerene acceptor molecules are represented to explore the significance of organic solar cells (OSCs). The electro-optical properties of the designed A–D–A-type molecules rely on the central core donor moiety associated with different halogen families such as fluorine, chlorine, and bromine atoms and acyl, nitrile, and nitro groups as acceptor moieties. Among these, M1 exhibits the maximum absorption (λmax) at 728 nm in a chloroform solvent as M1 has nitro and nitrile groups in the terminal acceptor, which is responsible for the red shift in the absorption coefficient as compared to R (716 nm). M1 also shows the lowest value of the energy band gap (2.07 eV) with uniform binding energy in the range of 0.50 eV for all the molecules. The transition density matrix results reveal that easy dissociation of the exciton is possible in M1. The highest value of the dipole moment (4.6 D) indicates the significance of M4 and M2 in OSCs as it reduces the chance of charge recombination. The low value of λe is given by our designed molecules concerning reference molecules, indicating their enhanced electron mobility. Thus, these molecules can serve as the most economically efficient material. Hence, all newly designed non-fullerene acceptors provide an overview for further development in the performance of OSCs.

1. Introduction

Organic-based non-fullerene acceptors (NFAs) have replaced outdated fullerene derivatives, and a new generation of n-type materials have been developed for obtaining high-performance organic photovoltaic cells (OPVs).1−4 The acceptor–donor–acceptor (A–D–A) design has been abundantly approved in the formation of low-band-gap NFAs. A suitable combination of acceptor and donor components can control the electrochemical and optical performances of A–D–A-type NFAs.5−9 Previously, a ladder-type donor (LD) and multi-fused rings of aromatic benzene and heteroatomic (selenophene and thiophene) rings were used to develop A–D–A NFAs. Moreover, the sp3-hybridized carbon bridge is an essential constituent to ring-lock where the contiguous rings in a cyclopentadienyl (CP) moiety were inserted into the multi-fused frameworks. For appropriate sufficient solubility, alkyl chains were also introduced. Also, besides this, the phenyl side chains and alkyl chain phenyl terminal have also been employed to exploit the molecular assembly of acceptors and to trigger the nanoscale morphology of active layers.10 The force planarization of one-dimensional LDs enables intramolecular D–A interactions, increases charge mobility, and extends effective conjugations. Broad research interest has been concentrated on developing symmetrical LDs flanked with aliphatic side substituents for fabricating new NFAs. The horizontal direction of a one-dimensional LD and its extending conjugation length is a straightforward strategy to strengthen π–π interactions and additional increasing π delocalization, resulting in charge mobility and better light-harvesting ability.10−18

Consequently, the high-performance A–LD–A NFAs have been achieved by reporting several one-dimensional hexacyclic, heptacyclic, octacyclic, non-acyclic, and decacyclic multi-fused-ring LDs. It was predicted that extending the conjugation and perpendicular directions of a linear LD from a two-dimensional (2D) LD could enhance the benefits of rigidification and chemical planarization. The devised molecular engineering strategy proves useful to build up efficient p-type polymers and n-type NFAs with improved photovoltaic characteristics. Moreover, the structure of the 2D ladder type is exciting and requires other design and synthesis methods.31−36

In 2013, first, a simplistic synthesis was proposed for angular-shaped 4,9-didodecylnaphthodithiophene (4,9-NDT) and its isomeric derivatives. 4,9-NDT, which consisted of the donor–acceptor copolymer, has shown high organic field-effect transistor mobility and good OPV performance. Recently, a new octacyclic ladder-type structure, NC, was synthesized, in which 4,9-NDT is a central core attached to two outer thiophenes and two carbon bridges are involved in a ring-locked conformation. The formylated NC was condensed with two FIC (1,1-dicyanamethylene-5,6-difluoro-3-indanone) acceptors to form an A–LD–A NFA, which is known as NC-FIC. However, unluckily, the OPV performance of the NC–FIC-based device was revealed to be moderate. Therefore, for property optimization, it was needed to modify the structure of NC. In 2016, the synthesis of a didodecyltetrathienonaphthalene (TTN) unit with stronger absorptivity and excellent solubility was first reported. When the 4,9-didodecyl NDT unit in NC is replaced with the 5,11-didodecyl TTN moiety, didodecyltetrathienonaphthalenyldi(cyclopentathiophene) (TC), a 2D ladder-type structure, is prepared.

In a previous work, condensation of the formylated TC with the FIC acceptor provided a 2D NFA called TC-FIC, taken as reference (R) in our study.10 The development from NC to TC awards TC-FIC many advantages in electronic and optical properties, as listed below: (1) this 2D conjugated TC enhances the electron-donating ability that produces substantial intermolecular charge transfer, which can be result in the broadening of absorption to the NIR region; (2) the two thiophene units stabilize the quinoidal form of the central LD in TTN, which are vertically fused, permitting π-electron delocalization more effectively; and (3) this longer π-system of TC might assist in intra- and intermolecular charge transportation. Using the reference molecule (R), we designed five new molecules with some push–pull groups that enhance the charge transfer properties of the designed molecules. The five molecules are designed through the replacement of the fluorine atom in the terminal of the reference with a nitro group, the structure denoted M1; with a chlorine atom, the structure denoted M2; with a cyano group, the structure denoted M3; with a bromine atom, the structure denoted M4; and with cyano and acyl groups, the structure denoted M5, which are shown in Figure 1. This investigation focuses on analyzing the effect of the halogen family on the subsequent core as the fluorine atom is very reactive and causes many environmental issues. Hence, using less toxic atoms can be more beneficial for the assembly of organic solar cells (OSCs).

Figure 1.

Representation of reference (R) and designed structures (M1–M5).

2. Computational Details

The theoretical study was conducted to select the best functional method of the density functional theory (DFT) to simulate the molar absorption coefficient of the reference R and five newly proposed NFA molecules (M1–M5). One of the most well-known, potent, and alluring programs is the Gaussian 09 package, which is used for all calculations in computational chemistry.11 Using the GaussView 6.0 program, three-dimensional (3D) structures of designed molecules were drawn,12 and their outputs were visualized.13 The diagrams of the optimized geometries and molecular orbitals were obtained using Avogadro software.14 Geometry optimization for the initial conformation analysis of designed molecules was conducted through the DFT, which ensures the minimum energy of simulated molecules. For the calculation of the absorption coefficient for the reference molecule, different methods of the DFT such as WB97XD,15 MPW1PW91,16 M06-2X,17 and B3LYP18 were used. MPW1PW91 provides a favorable interaction between the experimental and reported value.19 Thus, this method (MPW1PW91) was selected for further calculations of M1–M5. For electronic properties and optimization of the geometry, the 6-31G (d,p) functional that has been used frequently provides favorable results, and thus, this method is used for all theoretical calculations20 involving highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO)–lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) energy gaps, molecular orbitals energies, and their contribution toward electronic transitions, analyzing neutral molecules, and cation and anion calculations. UV–vis absorption spectra were analyzed for the optimized geometry of molecules for the electronic transitions in the gaseous and solvent phases by using the solvation model CPCM (conductor-like polarizable continuum model) with the chloroform solvent.21 For the analysis of the density of states (DOS), PyMOlyze22 software was used. These calculations were performed by dividing the molecules into different fragments that either include two parts (terminal, i.e., our acceptor, and the core, i.e., the donor fragment) or can be divided into three parts (donor, acceptor, and donor).

Reorganization energy (RE) can be classified into internal RE (λint) and external RE (λext). Internal RE is responsible for the abrupt change and is related to the internal geometry of the molecule, where the equations for their calculation are given below.

| 1 |

| 2 |

where  and

and  represent the energies of the neutral molecule

for anionic and cationic optimized structures, whereas E– and E+ are the calculated

energies of the anion and cation obtained from their respective optimized

geometry, respectively. Eo is the ground-state

neutral molecule energy. The convenient tool to estimate the nature

of transitions in the excited state is the transition density matrix

(TDM).23 TDM calculations were also used

to analyze excitation processes, particularly in light-harvesting

molecules.24 Multiwfn package25 was used for plotting the electron density map

(EDM) for reference and targeted molecules (M1–M5). The EDM shows that electron density resides at some specific points.

Thus, Multiwfn software supported us in studying the variations in

the electron localization.26

represent the energies of the neutral molecule

for anionic and cationic optimized structures, whereas E– and E+ are the calculated

energies of the anion and cation obtained from their respective optimized

geometry, respectively. Eo is the ground-state

neutral molecule energy. The convenient tool to estimate the nature

of transitions in the excited state is the transition density matrix

(TDM).23 TDM calculations were also used

to analyze excitation processes, particularly in light-harvesting

molecules.24 Multiwfn package25 was used for plotting the electron density map

(EDM) for reference and targeted molecules (M1–M5). The EDM shows that electron density resides at some specific points.

Thus, Multiwfn software supported us in studying the variations in

the electron localization.26

3. Results and Discussion

The ground-state geometries of our molecules, including a reference that consists of a central donor and two acceptor moieties with an A–D–A type configuration, are compiled in Figure 2. The reference molecule (R) was initially optimized using four methods: B3LYP, M06-2X, MPW1PW91, and WB97XD. These methods were used to select the best scheme for further calculations including optimization of M1–M5, estimation of the band gap and the distribution pattern of electrons around the HOMO–LUMO, and calculation of the DOS. For the reference molecule (R), λmax values were 768, 716, 530, and 567 nm according to B3LYP, MPW1PW91, WB97XD, and M06-2X, respectively. However, the experimental value of R was 719 nm. 716 nm was much closer to the experimentally determined value (719 nm), so the MPW1PW91 functional was chosen for more calculations for our considered molecules. The collected results of the absorption maxima of the reference molecule obtained from different methods of the DFT are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 2.

Ground-state structures for R, M1, M2, M3, M4, and M5.

Figure 3.

Comparison of absorption peaks for R at the 6-31G(d,p) basis set using different methods.

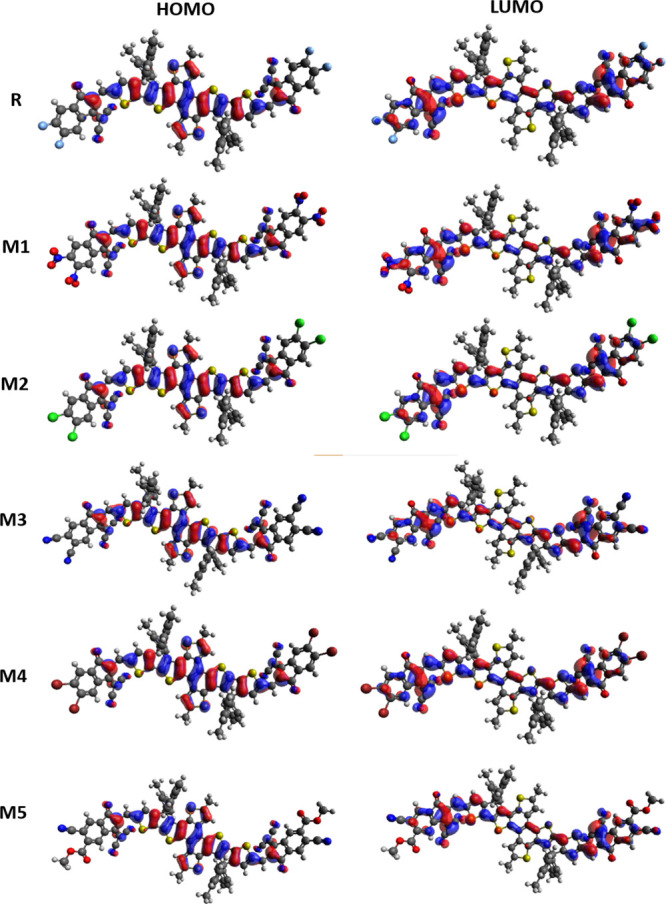

3.1. Frontier Molecular Orbital Analysis

Frontier molecular orbitals (FMOs) describe the electronic distribution of charges around the molecules. The electro-optical properties of our compounds have been investigated, which are related to the distribution pattern (Figure 4). The individual orbital energies of the HOMO, LUMO, and band gap for R were −5.60, −3.37, and 2.23 eV, respectively. The HOMO energies were found to be −5.96, −5.65, −5.94, −5.64, and −5.74 eV and the LUMO values were found to be −3.89, −3.45, −3.85, −3.44, and −3.58 eV for the considered molecules M1, M2, M3, M4, and M5, respectively. The corresponding band gaps were 2.23, 2.07, 2.20, 2.09, 2.20, and 2.16 eV for molecules R, M1, M2, M3, M4, and M5, respectively, which have been presented in Table 1. The comparative study of the HOMO–LUMO band gap revealed that molecules M1–M5 and R have the highest energy gap (2.23 eV), while M1 has the lowest energy gap (2.07 eV).

Figure 4.

FMOs of R and M1–M5 molecules at the ground state.

Table 1. Individual HOMO–LUMO and Band Gap Energies of R and M1–M5.

| molecule | HOMO (eV) | LUMO (eV) | band gap (eV) |

|---|---|---|---|

| R | –5.60 | –3.37 | 2.23 |

| M1 | –5.96 | –3.89 | 2.07 |

| M2 | –5.65 | –3.45 | 2.20 |

| M3 | –5.94 | –3.85 | 2.09 |

| M4 | –5.64 | –3.44 | 2.20 |

| M5 | –5.74 | –3.58 | 2.16 |

The best molecule concerning the band gap energy is the M1-designed molecule. The increasing order of the band gap was observed to be M1 < M3 < M5 < M4 = M2 < R. The band gap of M3 is more diminutive than that of M4 and M2 due to the high electron-withdrawing effect owing to the presence of nitrile groups (CN). In contrast, chlorine and bromine atoms showed the same values of the band gap. M4 = M2 have a higher band gap value than M3 and M5 due to less conjugation in the acceptor molecule (Figure 5a). Through structure visualization, it was noticed that the higher band gap of M2 and M4 than that of M1 and M3 is the consequence of nitrile and nitro groups. As M2 has the most negligible band gap value, it is indicated that the nitro group is a better acceptor than the nitrile group. The corresponding 3D HOMO, LUMO, and band gap spectra have been displayed in Figure 5b.

Figure 5.

(a) Graphical band energy alignments and (b) 3D graphical band energy distribution of R and M1–M5.

To support this evidence described by FMOs and to explore the electronic properties, the DOS analysis was carried out by using the same functional MPW1PW91 with the basis set 6-31G(d,p) for reference molecule R and other molecules M1–M5, as shown in Figure 6. The electronic distribution around the HOMO–LUMO is mainly affected by electron-withdrawing acceptor groups attached to the central core unit. In the case of R, the LUMO distribution suppresses over the central core and also on the acceptor units near the central cores. In M3, the whole electron density is present over the central donor moiety of the molecule at the HOMO, while at the LUMO, the whole density is shifted toward the acceptor moiety. Similarly, M4 and M5 showed the same trend as that of M3 in both the HOMO and LUMO. Hence, M1 showed the efficient charge distribution from donors to acceptors. This is due to the strong electron-withdrawing effect of nitro and nitrile groups compared to that of other attached atoms or groups.

Figure 6.

DOSs for M1, M2, M3, M4, M5, and R.

A better understanding of intramolecular charge transfer properties is possible through the molecular electrostatic potential (MEP). The results obtained by MEP calculations for all molecules are shown in Figure 7. It not only provides information about the charge transfer but also predicts the electrophilic and nucleophilic sites. The green region represents a center for both electrophilic attack and nucleophilic attack due to the equivalent electron density, whereas the yellowish region around some atoms such as sulfur in M1 and M3 is more nucleophilic in nature. M1 is far better than the others due to better availability for the nucleophilic and electrophilic reactions.

Figure 7.

MEPs of R, M1, M2, M3, M4, and M5.

3.2. Optical Properties

The MPW1PW91 functional, along with the basis set 6-31G(d,p), was used to calculate the optical properties of the reference and five newly developed acceptor molecules (M1–M5). The absorption spectra for these molecules were computed in the gaseous and solvent phases such as chloroform. The absorption maxima (λmax), oscillator strength (fo), excitation energy (ΔE), and transitions are given in Tables 2 and 3. The λmax values in the gas phase obtained from computational analysis 673, 728, 685, 721, 686, and 699 nm are the maximum absorption values shown by R, M1, M2, M3, M4, and M5, respectively. These computed results illustrated that λmax values for our molecules are more significant than that of the reference molecule as the reference molecule has the lowest value of λmax (673 nm) as compared to other molecules M1–M5 that have maximum absorption values of 728, 685, 721, 686, and 699 nm, respectively. The decreasing order of λmax among these molecules has the following sequence M1 > M3 > M4 > M2 > R > M5. From all the above discussion, we deduced that M1 has the highest λmax value. Therefore, slightly broad absorption spectra were obtained for M1 relative to those for R and all other molecules (M2–M4). The reason behind the higher values of λmax (728 nm) and the lower band gap (2.07 eV) of M1 is the involvement of the nitro and nitrile groups in the terminal side of the molecule.

Table 2. Calculated and Experimental Absorption Values, Transition Energy (ΔE) for the First Excited State (S0 → S1), Largest Oscillator Strength (fo), and % Configuration Interaction (C.I.) for R and M1–M5 at MPW1PW91/6-31G(d,p) in a Chloroform Solvent.

| molecule | calc. λmax (nm) | exp. λmax (nm) | ΔE | fo | transitions | % C.I. | μ (D) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R | 716 | 719 | 1.73 | 2.12 | H → L | 69 | 4.99 |

| M1 | 788 | 1.57 | 1.84 | H → L | 69 | 3.14 | |

| M2 | 732 | 1.70 | 2.19 | H → L | 69 | 4.15 | |

| M3 | 775 | 1.60 | 2.06 | H → L | 69 | 3.42 | |

| M4 | 732 | 1.69 | 2.22 | H → L | 69 | 4.58 | |

| M5 | 707 | 1.65 | 2.01 | H → L | 69 | 4.45 |

Table 3. Transition Energy (ΔE) for the First Excited State (S0 → S1), Largest Oscillator Strength (FO), and % Configuration Interaction (C.I.) for R and M1–M5 at MPW1PW91/6-31G(D,P) in a Gas Medium.

| molecule | calc. λmax (nm) | ΔE | fo | transitions | % C.I. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R | 673 | 1.84 | 1.88 | H → L | 70 |

| M1 | 728 | 1.70 | 1.73 | H → L | 70 |

| M2 | 685 | 1.81 | 1.97 | H → L | 70 |

| M3 | 721 | 1.72 | 1.88 | H → L | 70 |

| M4 | 686 | 1.81 | 2.01 | H → L | 70 |

| M5 | 699 | 1.77 | 1.94 | H → L | 70 |

The UV–vis spectrum was also computed in a solvent chloroform, revealing that M2 and M4 have the same absorption range. Both M2 and M4 exhibited the same maximum absorption value, that is, 732 nm, in chloroform. Moreover, the HOMO–LUMO energy gaps for M2 and M4 are precisely equal (2.20) owing to the same electron-withdrawing effect of acceptor moieties, which are bromine and chlorine atoms, respectively. Extended values of λmax were found to be more dominant for M1 and M3 as compared to that for M2 and M4 molecules, whereas M5 has an intermediate absorption among these molecules. The decreasing order of λmax in the gaseous phase for the reference and considered acceptors was found to be M1 > M3 > M5 > M4 > M2 > R. To a vast extent, this order of λmax is similar to the order of maximum absorptions calculated in chloroform, where M2 and M4 have the same absorption value, as shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Absorption spectra of M1–M5 and R in chloroform.

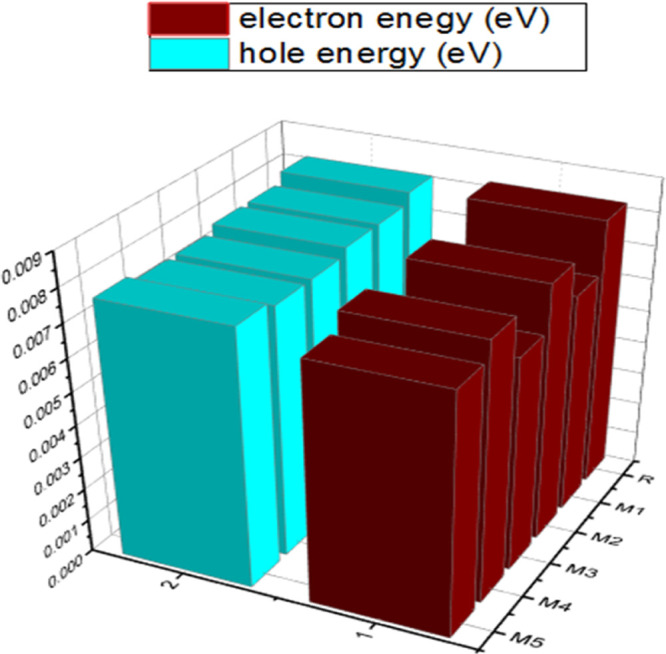

3.3. Reorganization Energy

The RE is a good factor that shows great potential for selecting the most efficient material for OSCs. RE is used to study the charge transfer properties of acceptor–donor units. There is a reverse relation between RE and charge transfer (transfer of electrons or holes). The lower the values of RE, the higher the charge transfer. The method used to estimate the RE for R and developed molecules (M1–M5) was MPW1PW91/6-31G(d,p), as shown in Figure 8. The estimated RE values are given in Table 4.

Figure 8.

3D graphical display of electron and hole energies of R and M1–M5.

Table 4. RE Values of R and M1, M2, M3, M4, and M5 at MPW1PW91 at the 6-31G(d,p) Level of Theory.

| molecule | λe (eV) | λh (eV) |

|---|---|---|

| R | 0.0082 | 0.0081 |

| M1 | 0.0067 | 0.0078 |

| M2 | 0.0078 | 0.0078 |

| M3 | 0.0065 | 0.0076 |

| M4 | 0.0078 | 0.0076 |

| M5 | 0.0073 | 0.0078 |

The results revealed that the RE of the electron–hole pair for newly developed molecules is in the order of M3 < M1 < M5 < M4 < M2 < R for electron mobility and M3 = M4 < M1 = M2 = M5 < R for hole mobility. M1, M2, M3, M4, and M5 showed lower λe than the R molecule. All these molecules exhibit higher electron mobilities corresponding to R. From the above, M3 has a shallow λe value (0.0065 eV), which means that M3 has the highest electron mobility. In contrast, a higher value of R (0.00815 eV) is responsible for low charge transfer. M2 and M4 have approximately equal λe values of 0.0078 and 0.0078 eV, respectively.

Also, the REs of the hole (λh) were found to be 0.0078, 0.0078, 0.0076, 0.0076, and 0.0078 eV for M1, M2, M3, M4, and M5, respectively. M3 and M4 exhibit a higher hole mobility due to the hole’s low (0.0076 eV) RE, whereas M1, M2, and M5 have less charge transferability due to the high λh value (0.0078 eV). This study may conclude that M3 with low λe and λh values showed that the nitrile group is important for designing the high-charge-mobility materials for a bright future for OSCs.31−38 In contrast, the nitro group is the second in terms of the charge transfer properties for charge conduction.

3.4. Dipole Moment

The dipole moment value is a crucial parameter to measure the solubility in the organic medium during the fabrication processes of OSCs. Solubility of molecules is a promising way to stimulate the self-assembly of molecules and enhance the crystallinity in thin films.27 Higher values of the dipole moment are responsible for higher solubility. It would give the best texture to the film. The current ground-state dipole moment was calculated using MPW1PW91/6-31G and is given in Table 2. The reported value of the dipole moment for reference R was found to be 4.99 D at the excited state. The present study revealed that dipole moments at the excited state are 3.14, 4.15, 8.50, 3.42, 4.58, and 8.04 D for the molecules of R and M1–M5, respectively. The decreasing order of dipole moments was observed to be R > M4 > M2 > M3 > M1 > M5. The comparison of dipole moments among the reference and considered molecules (M1–M5) showed that M1 has the lowest values of m compared to the remaining molecules. The higher values of m assist the self-aggregation within these molecules, while the opposite poles of neighboring molecules show high attraction toward each other in a thin film.

3.5. TDM and Binding Energy

The TDM is used to explain the connection of an exact excited-state molecule to a ground-state molecule due to the density matrix. In this study, these calculations were performed for R and five NFAs (M1–M5) that have been collected in Table 5. By using functional method MPW1PW91 along with the basis set 6-31G(d,p), TDM calculations were performed for the absorption and emission with the first single state in the gaseous phase, as shown in Figure 10. Hydrogen atoms show a minimal contribution in transition, which is why their effect is ignored in this study.

Table 5. Band Gap Energies [E(L–H)], First Transition Energies [E(opt)], and Binding Energies of R and Selected Molecules (M1–M5).

| molecule | E(L–H) (EV) | E(OPT) (EV) gaseous | E(OPT) (EV) chloroform | EB (EV) gaseous | EB (EV) chloroform |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R | 2.23 | 1.84 | 1.73 | 0.39 | 0.50 |

| M1 | 2.07 | 1.70 | 1.57 | 0.37 | 0.50 |

| M2 | 2.20 | 1.81 | 1.70 | 0.39 | 0.50 |

| M3 | 2.09 | 1.72 | 1.60 | 0.37 | 0.49 |

| M4 | 2.20 | 1.81 | 1.69 | 0.39 | 0.51 |

| M5 | 2.16 | 1.77 | 1.65 | 0.39 | 0.51 |

Figure 10.

TDM diagrams of R and M1–M5.

The designed molecules were divided into C (central core) and T (terminal part). By carefully examining TDM graphs, we concluded that the coherence of electrons was observed in the diagonal direction of M1–M5, but R showed a different behavior. The increasing order of interaction between this donor and acceptor was found to be M1 < M3 < M4 = M5 < M2 < R. According to this order, M3 has the lowest value of binding energy (0.49). These values showed weak interactions. Therefore, coupling between the electron and hole is minimal in M3 compared to that in the reference and other molecules. As a result, easy dissociation of the electron–hole pair takes place in M3, which enhances the transfer of charge.

Nevertheless, the difference in the binding energy of other molecules is not so high. Therefore, all our molecules have an almost equal dissociation energy with a ±0.01 difference. Finally, it can be concluded that all our molecules have potential for their application in OSCs due to the equal distribution of charges among the molecular network of each molecule.

Further, the binding energy in the gaseous form and chloroform showed that molecules M1 and M3 showed the lowest binding energy compared to R, M2, and M4. Low binding energy is responsible for easy excitation dissociation for efficient charge transfer. However, in chloroform, only M3 showed a lower binding energy than other molecules, but the difference is negligible. This indicates that all molecules have comparable binding energies.

3.6. Open-Circuit Voltage and Charge Transfer Analysis

To check the performance of OSCs, open-circuit voltage (Voc) is fundamental.39−44 The recombination of the device provides information about the saturation current and light generation that gives information about Voc, which is dependent on energy differences of the HOMO and LUMO of acceptor and donors. Our designed molecule was compared with a well-known polymer PCBM, an acceptor polymer.28 The Voc values for R, M1, M2, M3, M4, and M5 under the PBDB-T polymer were 1.69, 1.17, 1.61, 1.21, 1.62, and 1.78 V, respectively (Figure 11). Hence, the Voc values of these molecules are comparable with each other, but the highest Voc value was obtained for M5.

Figure 11.

VOC for R and M1–M5 with the PBDB-T polymer.

M1 interaction with donor polymer BPTB-T is investigated to visualize our engineered molecules’ charge transfer capabilities. Xu et al. (and others)10,29,30 recorded intermolecular interactions using the simulated and numerical methods in different phases where MPW1PW91/6-31G(d,p) functionals were employed that show a slight difference in the measured consequences.

Optimization of the BPTB-T polymer was performed using the same MPW1PW91/6-31G(d,p) level, as shown in Figure 12. Subsequently, thermal analysis was performed, and it was observed that high-temperature interactions with the donor polymer are nearly similar to that with the M1 acceptor of acceptable distance. This orientation is ideal for the transfer of charge and the phase of excitation. Figure 13 shows the pictographic view for the HOMO and LUMO of the M1–BPTB-T complex. The central region of the polymer is augmented by the ground-state electron density, which is transferred during excitation to the entire M1 molecule. Notably, the HOMO is situated over the polymer, while L is populated on molecule M1. In addition, the electrons are distributed from the BPTB-T donor polymer acceptor region to the M1 acceptor region. Consequently, our recipe is a better candidate for practical photovoltaic cell fabrication to provide optimum Voc.

Figure 12.

Optimized geometries of PBDB-T along with M1 at the MPW1PW91/6-31G(d,p) level.

Figure 13.

Electronic distribution on the HOMO and LUMO of PBDB-T in the presence of M1.

4. Conclusions

In the present study, we design five novel molecules based on NFAs (M1–M5) that consist of a central core donor that is peripherally attached to five acceptor groups from the halogen family and the nitro group. It has been investigated successfully that the introduction of these acceptor groups is a promising route to design effective NFAs. Therefore, in this study, we use the MPW1PW91 method and a 6-31G(d,p) basis set for the calculation of electronic characteristics, including open-circuit voltage, electron–hole charge mobility, absorption spectra, frontier orbital energies, dipole moment, and TDM for M1–M5 and R. Subsequently, these properties were successfully compared with those of the recently reported reference R, and an excellent coherence is found. From the present study, we concluded that all these designed NFAs give fruitful results compared to R. This work suggests that all these molecules have lower values of the energy gap, reorganization, and binding energy of exciton while representing higher values of λmax and dipole moment than that of R. From the comparative analysis of the acceptor groups in the designed molecules, it is evident that nitrile and nitro groups play a significant role in the overall optoelectronic properties of the molecules compared to the halogen family.

Acknowledgments

The author from King Khalid University extends his appreciation to the Deanship of Scientific Research at King Khalid University for support through the research project (RGP.2/156/42). The authors also acknowledge the computational facility support from the COMSAT Abbottabad, Pakistan, and the financial and technical support from the University of Okara, Pakistan.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- ul Ain Q.; Shehzad R. A.; Yaqoob U.; Sharif A.; Sajid Z.; Rafiq S.; Iqbal S.; Khalid M.; Iqbal J. Designing of Benzodithiophene Acridine Based Donor Materials with Favorable Photovoltaic Parameters for Efficient Organic Solar Cell. Comput. Theor. Chem. 2021, 1200, 113238. 10.1016/j.comptc.2021.113238. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shehzad R. A.; Iqbal J.; Khan M. U.; Hussain R.; Javed H. M. A.; Rehman A. U.; Alvi M. U.; Khalid M. Designing of Benzothiazole Based Non-Fullerene Acceptor (NFA) Molecules for Highly Efficient Organic Solar Cells. Comput. Theor. Chem. 2020, 1181, 112833. 10.1016/j.comptc.2020.112833. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hussain R.; Khan M. U.; Mehboob M. Y.; Khalid M.; Iqbal J.; Ayub K.; Adnan M.; Ahmed M.; Atiq K.; Mahmood K. Enhancement in Photovoltaic Properties of N,N-Diethylaniline Based Donor Materials by Bridging Core Modifications for Efficient Solar Cells. ChemistrySelect 2020, 5, 5022–5034. 10.1002/slct.202000096. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mehboob M. Y.; Khan M. U.; Hussain R.; Ayub K.; Sattar A.; Ahmad M. K.; Irshad Z.; Saira; Adnan M. Designing of Benzodithiophene Core-Based Small Molecular Acceptors for Efficient Non-Fullerene Organic Solar Cells. Spectrochim. Acta, Part A 2021, 244, 118873. 10.1016/j.saa.2020.118873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adnan M.; Mehboob M. Y.; Hussain R.; Irshad Z. Banana-shaped non-fullerene acceptor molecules for highly stable and efficient organic solar cells. Energy Fuels 2021, 35, 11496–11506. 10.1021/acs.energyfuels.1c01431. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Adnan M.; Mehboob M. Y.; Hussain R.; Irshad Z. In silico designing of efficient C-shape non-fullerene acceptor molecules having quinoid structure with remarkable photovoltaic properties for high-performance organic solar cells. Optik 2021, 241, 166839. 10.1016/j.ijleo.2021.166839. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mehboob M. Y.; Hussain R.; Irshad Z.; Adnan M. Enhancement in the photovoltaic properties of hole transport materials by end-capped donor modifications for solar cell applications. Bull. Korean Chem. Soc. 2021, 42, 597–610. 10.1002/bkcs.12238. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mehboob M. Y.; Hussain R.; Adnan M.; Irshad Z. End-capped molecular engineering of S-shaped hepta-ring-containing fullerene-free acceptor molecules with remarkable photovoltaic characteristics for highly efficient organic solar cells. Energy Technol. 2021, 9, 2001090. 10.1002/ente.202001090. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mehboob M. Y.; Hussain R.; Irshad Z.; Adnan M. Designing of U-shaped acceptor molecules for indoor and outdoor organic solar cell applications. J. Phys. Org. Chem. 2021, 34, e4210 10.1002/poc.4210. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chang S.-L.; Cao F.-Y.; Huang K.-H.; Lee W.-L.; Lee M.-H.; Hsu C.-S.; Cheng Y.-J. 2-Dimensional Cross-Shaped Tetrathienonaphthalene-Based Ladder-Type Acceptor for High-Efficiency Organic Solar Cells. J. Mater. Chem. A 2020, 8, 12141–12148. 10.1039/D0TA04240D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; pubs.rsc.org

- Frisch M. J.; Trucks G. W.; Schlegel H. B.; Scuseria G. E.; Robb M. A.; Cheeseman J. R.; Scalmani G.; Barone V.; Mennucci B.; Petersson G.; et al.. Gaussian 09; Revision D. 01; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford CT, 2009. See also URL http//www. gaussian. com.

- Dennington R. D.; Keith T. A.; Millam J.. GaussView 5.0; Gaussian. Inc.: Wallingford, 2008, p 340.

- Hanwell M. D.; Curtis D. E.; Lonie D. C.; Vandermeerschd T.; Zurek E.; Hutchison G. R. Avogadro: An Advanced Semantic Chemical Editor, Visualization, and Analysis Platform. J. Cheminf. 2012, 4, 17. 10.1186/1758-2946-4-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chai J.-D.; Head-Gordon M. Long-Range Corrected Hybrid Density Functionals with Damped Atom–Atom Dispersion Corrections. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2008, 10, 6615–6620. 10.1039/B810189B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; pubs.rsc.org

- Adamo C.; Barone V. Exchange functionals with improved long-range behavior and adiabatic connection methods without adjustable parameters: The mPW and mPW1PW models. J. Chem. Phys. 1998, 108, 664. 10.1063/1.475428. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y.; Verma P.; Zhang L.; Li Y.; Liu Z.; Truhlar D. G.; He X. M06-SX screened-exchange density functional for chemistry and solid-state physics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2020, 117, 2294–2301. 10.1073/pnas.1913699117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finley J. P. Using the Local Density Approximation and the LYP, BLYP and B3LYP Functionals within Reference-State One-Particle Density-Matrix Theory. Mol. Phys. 2004, 102, 627–639. 10.1080/00268970410001687452. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y.; Wang X.-Y.; Peng P.-X.; Wang X.-C.; Cao X.-Y.; Feng X.; Müllen K.; Narita A. Benzo-Fused Double [7]Carbohelicene: Synthesis, Structures, and Physicochemical Properties. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 3374–3378. 10.1002/anie.201610434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rassolov V. A.; Pople J. A.; Ratner M. A.; Windus T. L. 6-31G* basis set for atoms K through Zn. J. Chem. Phys. 1998, 109, 1223.M. R.-T. J. of chemical 10.1063/1.476673. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Klamt A.; Moya C.; Palomar J. A Comprehensive Comparison of the IEFPCM and SS(V)PE Continuum Solvation Methods with the COSMO Approach. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2015, 11, 4220–4225. 10.1021/acs.jctc.5b00601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amanullah; Ali U.; Ans M.; Iqbal J.; Iqbal M. A.; Shoaib M. Benchmark Study of Benzamide Derivatives and Four Novel Theoretically Designed (L1, L2, L3, and L4) Ligands and Evaluation of Their Biological Properties by DFT Approaches. J. Mol. Model. 2019, 25, 223. 10.1007/s00894-019-4115-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y.; Ullrich C. A. The Particle-Hole Map: A Computational Tool to Visualize Electronic Excitations. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2015, 11, 5838–5852. 10.1021/acs.jctc.5b00987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y.; Ullrich C. A. Time-Dependent Transition Density Matrix. Chem. Phys. 2011, 391, 157–163. 10.1016/j.chemphys.2011.02.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; Elsevier

- Lu T.; Chen F. Multiwfn: A multifunctional wavefunction analyzer. J. Comput. Chem. 2012, 33, 580–592. 10.1002/jcc.22885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irshad Z.; Adnan M.; Lee J. K. Efficient planar heterojunction inverted perovskite solar cells with perovskite materials deposited using an aqueous non-halide lead precursor. Bull. Korean Chem. Soc. 2020, 41, 937–942. 10.1002/bkcs.12092. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Takacs C. J.; Sun Y.; Welch G. C.; Perez L. A.; Liu X.; Wen W.; Bazan G. C.; Heeger A. J. Solar Cell Efficiency, Self-Assembly, and Dipole-Dipole Interactions of Isomorphic Narrow-Band-Gap Molecules. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 16597–16606. 10.1021/ja3050713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irshad Z.; Adnan M.; Lee J. K. Controlling phase and morphology of all-dip-coating processed HC (NH2) 2PbI3 perovskite layers from an aqueous halide-free lead precursor. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2022, 160, 110374. 10.1016/j.jpcs.2021.110374. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen G.; Chen W.-C.; Ji S.; Zhou P.; Cai N.; Zhan Y.; Liang H.; Tan J.-H.; Pan C.; Huo Y. Polymorphic Mechanoresponsive Luminescent Material Based on a Fluorene-Phenanthroimidazole Hybrid by Modulation of Intramolecular Conformation and Intermolecular Interaction. CrystEngComm 2020, 22, 2147–2157. 10.1039/d0ce00006j. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu W.; Ma X.; Son J. H.; Jeong S. Y.; Niu L.; Xu C.; Zhang S.; Zhou Z.; Gao J.; Woo H. Y.; Zhang J.; Wang J.; Zhang F. Smart Ternary Strategy in Promoting the Performance of Polymer Solar Cells Based on Bulk-Heterojunction or Layer-By-Layer Structure. Small 2022, 18, 2104215. 10.1002/smll.202104215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Z.; Wang J.; Wang Z.; Gao W.; An Q.; Zhang M.; Ma X.; Wang J.; Miao J.; Yang C.; Zhang F. Semitransparent Ternary Nonfullerene Polymer Solar Cells Exhibiting 9.40% Efficiency and 24.6% Average Visible Transmittance. Nano Energy 2019, 55, 424–432. 10.1016/j.nanoen.2018.11.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y.; Wang J.; Zhang Z.-G.; Bai H.; Li Y.; Zhu D.; Zhan X. An Electron Acceptor Challenging Fullerenes for Efficient Polymer Solar Cells. Adv. Mater. 2015, 27, 1170–1174. 10.1002/adma.201404317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan J.; Zhang Y.; Zhou L.; Zhang G.; Yip H.-L.; Lau T.-K.; Lu X.; Zhu C.; Peng H.; Johnson P. A.; Leclerc M.; Cao Y.; Ulanski J.; Li Y.; Zou Y. Single-Junction Organic Solar Cell with over 15% Efficiency Using Fused-Ring Acceptor with Electron-Deficient Core. Joule 2019, 3, 1140–1151. 10.1016/j.joule.2019.01.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y.; Zheng N.; Yu L.; Wen S.; Gao C.; Sun M.; Yang R. A Simple Phenyl Group Introduced at the Tail of Alkyl Side Chains of Small Molecular Acceptors: New Strategy to Balance the Crystallinity of Acceptors and Miscibility of Bulk Heterojunction Enabling Highly Efficient Organic Solar Cells. Adv. Mater. 2019, 31, 1807832. 10.1002/adma.201807832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y.; Yu L.; Chen L.; Han C.; Jiang H.; Liu Z.; Zheng N.; Wang J.; Sun M.; Yang R.; Bao X. Subtle Side Chain Triggers Unexpected Two-Channel Charge Transport Property Enabling 80% Fill Factors and Efficient Thick-Film Organic Photovoltaics. Innovations 2021, 2, 100090. 10.1016/j.xinn.2021.100090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adnan M.; Lee J. K. All Sequential Dip-Coating Processed Perovskite Layers from an Aqueous Lead Precursor for High Efficiency Perovskite Solar Cells. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 2168. 10.1038/s41598-018-20296-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adnan M.; Lee J. K. Highly Efficient Planar Heterojunction Perovskite Solar Cells with Sequentially Dip-Coated Deposited Perovskite Layers from a Non-Halide Aqueous Lead Precursor. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 5454–5461. 10.1039/c9ra09607h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adnan M.; Irshad Z.; Lee J. K. Facile All-Dip-Coating Deposition of Highly Efficient (CH3)3NPbI3-: XClxperovskite Materials from Aqueous Non-Halide Lead Precursor. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 29010–29017. 10.1039/d0ra06074g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adnan M.; Kim H. S.; Jeong H.; Ko H. M.; Woo S. K.; Lee J. K. Efficient Synthesis and Characterization of Solvatochromic Fluorophore. Bull. Korean Chem. Soc. 2017, 38, 1052–1057. 10.1002/bkcs.11219. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Adnan M.; Iqbal J.; Bibi S.; Hussain R.; Akhtar M. N.; Rashid M. A.; Eliasson B.; Ayub K. Fine Tuning the Optoelectronic Properties of Triphenylamine Based Donor Molecules for Organic Solar Cells. Z. Phys. Chem 2017, 231, 1127–1139. 10.1515/zpch-2016-0790. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmood A.; Yang J.; Hu J.; Wang X.; Tang A.; Geng Y.; Zeng Q.; Zhou E. Introducing Four 1,1-Dicyanomethylene-3-Indanone End-Capped Groups as an Alternative Strategy for the Design of Small-Molecular Nonfullerene Acceptors. J. Phys. Chem. C 2018, 122, 29122–29128. 10.1021/acs.jpcc.8b09336. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmood A.; Tang A.; Wang X.; Zhou E. First-Principles Theoretical Designing of Planar Non-Fullerene Small Molecular Acceptors for Organic Solar Cells: Manipulation of Noncovalent Interactions. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2019, 21, 2128–2139. 10.1039/c8cp05763j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irshad Z.; Adnan M.; Lee J. K. Simple preparation of highly efficient MAxFA1– xPbI3 perovskite films from an aqueous halide-free lead precursor by all dip-coating approach and application in high-performance perovskite solar cells. J. Mater. Sci. 2022, 57, 1–11. 10.1007/s10853-022-06867-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li J.; Sun C.; Tang A.; Zhang B.; Guo Q.; Zhou E.; Li Y. Utilizing an Electron-Deficient Thieno[3,4-: C] Pyrrole-4,6-Dione (TPD) Unit as a π-Bridge to Improve the Photovoltaic Performance of A-π-D-π-A Type Acceptors. J. Mater. Chem. C 2020, 8, 15981–15984. 10.1039/d0tc04601a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J.; Geng Y.; Li J.; Zhao B.; Guo Q.; Zhou E. A-DA′D-A-Type Non-Fullerene Acceptors Containing a Fused Heptacyclic Ring for Poly(3-Hexylthiophene)-Based Polymer Solar Cells. J. Phys. Chem. C 2020, 124, 24616–24623. 10.1021/acs.jpcc.0c07162. [DOI] [Google Scholar]