Abstract

Human carbonic anhydrase inhibitors (hCAIs) are a key therapeutic class with a multitude of novel applications such as anticonvulsants, topically acting antiglaucoma, and anticancer drugs. Herein, a new series of 4-anilinoquinazoline-based benzenesulfonamides were designed, synthesised, and biologically assessed as potential hCAIs. The target compounds are based on the well-tolerated kinase scaffold (4-anilinoquinazoline). Compounds 3a (89.4 nM), 4e (91.2 nM), and 4f (60.9 nM) exhibited 2.8, 2.7, and 4 folds higher potency against hCA I when compared to the standard (AAZ, V), respectively. A single digit nanomolar activity was elicited by compounds 3a (8.7 nM), 4a (2.4 nM), and 4e (4.6 nM) with 1.4, 5, and 2.6 folds of potency compared to AAZ (12.1 nM) against isoform hCA II, respectively. Structure-activity relationship (SAR) and molecular docking studies validated our design approach that revealed highly potent hCAIs.

Keywords: Quinazoline-benzenesulfonamide hybrids, Suzuki coupling, Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors, Molecular docking

1. Introduction

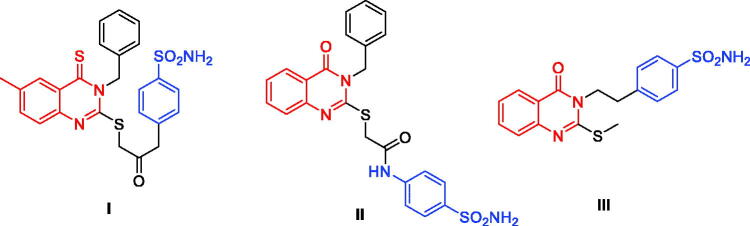

Carbonic anhydrases (CAs) are metalloenzymes responsible for converting CO2 to bicarbonate and proton in living organisms1. Human CAs of the α-class (α-CA) can be additionally grouped into sixteen isoforms that vary in cellular localisation, oligomeric structure, allocation in organs and tissues, kinetic properties, expression levels, and molecular characteristics2. Each isoform exhibits a specific subcellular localisation; CA I, II, III, VII, and XIII are cytosolic, CA IV, IX, XII, XIV, and XV are membrane-associated, while CA VA and VB are mitochondrial, and CA VI is secreted3–5. CAs are involved in a number of physiological activities such as breathing, pH regulation, bone resorption, ion transport, and gastric fluid secretion6. Consequently, CA inhibitors have become a leading therapeutic class in recent decades. Anticancer agents, anticonvulsants and topically acting antiglaucoma are some of the novel applications of CA inhibitors that have been reported2,7. Due to its expression in the endothelium of neovessels in melanoma, renal, lung, and oesophageal cancers, CA II is the most physiologically relevant isoform which was linked with various tumours including melanoma, oesophageal, renal, and lung cancers8. Inhibition of CA II also decreases angiogenesis via inhibition of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR) signaling9. The most common approach in designing CA inhibitors has been through the modulation of the ring directly bound to the zinc binding group (ZBG) or by attaching different “tails” to the aromatic ring as demonstrated by compounds I‒III (Figure 1)10–13.

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of potent quinazoline-based analogues as carbonic anhydrase inhibitors possessing primary sulphonamide (ZBG) moiety.

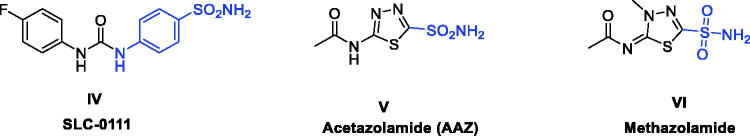

Sulphonamides are a well-known ZBG moieties possessing effective carbonic anhydrase inhibitory activities, compounds I–III (Figure 1)12. Aromatic sulphonamides are reported to be strong and specific inhibitors of CA isoforms and deemed to be promising leads for further modifications and development of more potent inhibitors13. However, the lack of selectivity in blocking distinct isoforms is a key downside of CAIs, which is caused by structural similarity and identical subcellular location of these isoforms, resulting in adverse side effects14. Among the studied sulphonamides, the primary sulphonamide is one of the most effective ZBG for designing carbonic anhydrases inhibitors. This is owing to structural features that make them optimal for binding to the Zn2+ ion in the active site cavity and surrounding residues15–17. The negatively charged nitrogen of SO2NH‒ binds to the positively charged metal ion substituting the physiological zinc-bound nucleophile, where the proton found on the coordinated nitrogen atom acting as an acceptor via being at H-bond distance to Thr199 OG1 atom16. Several sulphonamide-based carbonic anhydrase inhibitors are currently in clinical trial targeting various diseases, such as SLC-0111 (IV, Figure 2) which is currently in phase I clinical trials as for patients with advanced tumours18. Acetazolamide (V, Figure 2) and Methazolamide (VI, Figure 2) are two examples of sulphonamide-based drugs which are currently undergoing phase IV clinical trials as carbonic anhydrase I inhibitors19,20.

Figure 2.

Chemical structure of some of the small molecule inhibitors currently in clinical trials.

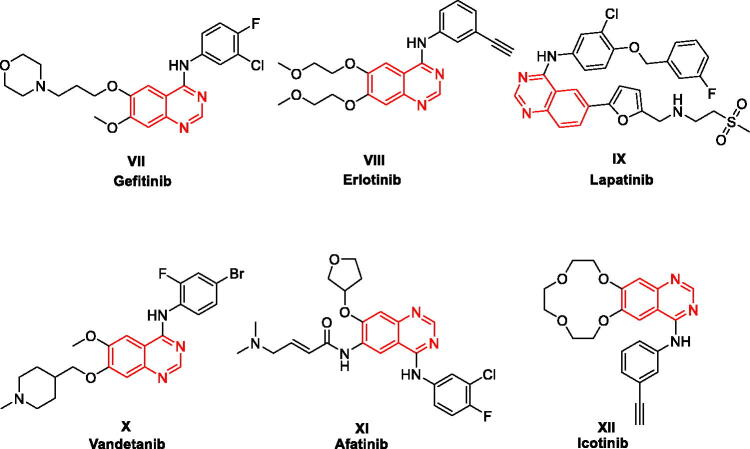

4-Anilinoquinazolines have been frequently explored as anticancer agents due to their reported inhibitory activity on various receptor tyrosine kinases, such as VEGFR-2 (Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2), EGFR (epidermal growth factor receptor), or receptor tyrosine-protein kinase erbB-2 (HER221,22. As illustrated in Figure 3, this heterocyclic class includes several approved drugs such as Gefitinib (Iressa®, VII), Erlotinib (Tarceva®, VIII), Lapatinib (Tykreb®, IX), Vandetanib (Caprelsa®, X), Afatinib (Gilotrif®, XI), and Icotinib (XII). Gefitinib (EGFR inhibitor) was approved by the FDA on May 2003 as a monotherapy to treat patients suffering from locally advanced or metastatic non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) following the failure of both platinum-based and docetaxel chemotherapies23. One year later, Erlotinib (EGFR inhibitor) was approved for treating NSCLC and in conjunction with gemcitabine for treatment of locally advanced, unrespectable, or metastatic pancreatic cancer24. In 2010, Lapatinib was approved for breast cancer treatment25. Lapatinib acts via inhibiting both HER2 and EGFR pathways and is utilised in combination therapies for HER2-positive breast cancer26. A year later, Vandetanib (a multi-kinase inhibitor) was approved as a treatment of metastatic medullary thyroid cancer27. Vandetanib exerts action through the inhibition of VEGFR, EGFR, and the RET-tyrosine kinase. Afatinib (EGFR/HER2 dual inhibitor) and Icotinib (EGFR inhibitor) were also approved for treatment of NSCLC28,29. These discoveries validate that 4-anilinoquinazoline is a privileged scaffold for developing anticancer drugs. Furthermore, the quinazoline ring was proved to be well-tolerated in the biological systems in terms of safety and potency30,31.

Figure 3.

FDA approved 4-Anilinoquinazolines tyrosine kinase inhibitors.

In the recent decade, some trials to develop quinazoline-based sulphonamides as CA inhibitors have been conducted. In 2014, a novel series of 2-substituted-mercapto-3-substituted-4(3H)-quinazolinones (I, Figure 1) was reported as α-carbonic anhydrases inhibitors from Vibrio cholerae32. Despite the high potency of these derivatives against Vibrio cholerae, they exhibited low inhibitory activity for the hCA I isoform (Ki range: 0.793–4.55 μM) and modest activity against the hCA II isoform (Ki range: 65.3 nM–0.114 μM). In the same year, another series of 4-oxoquinazoline containing a benzenesulfonamide moiety (II, Figure 1) was reported as a novel CA inhibitor against the protozoan enzyme of Trypanosoma cruzi33. The Oxoquinazoline (II) demonstrated moderate inhibition when tested against hCA I (Ki range: 86.5 nM– 5.43 μM) and a higher potency over hCA II isoforms. However, they have not been tested against the cancer-related hCA IX and XII isoforms.

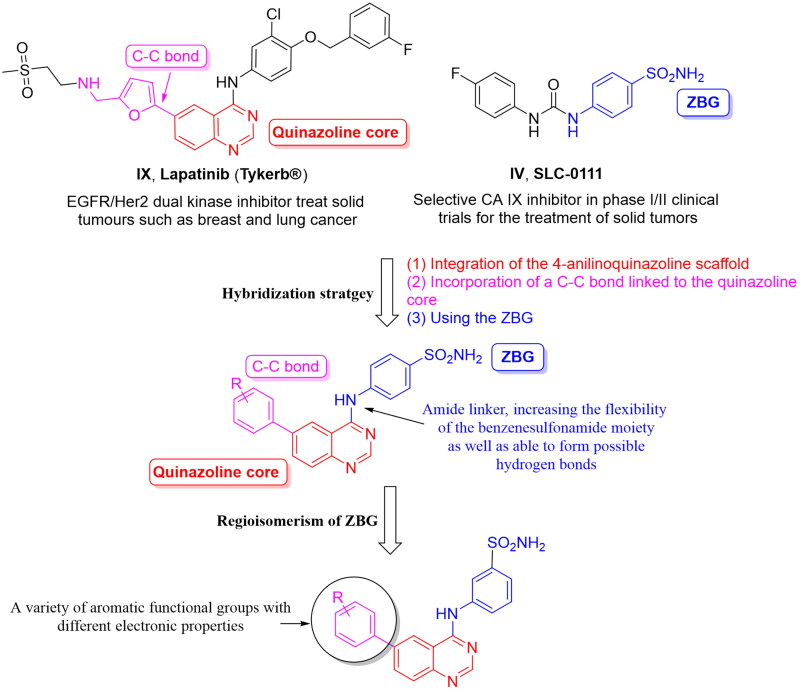

Resuming the efforts of developing effective quinazoline-based hCA inhibitors, a new series of novel 4-anilinoquinazoline-based sulphonamides were designed and synthesised (Figure 4). The effect of the aromatic substitutions at positions 4, 6 and 7 of the quinazoline core, as hCA inhibitor, is largely undiscovered. Therefore, a structural hybridisation strategy (Figure 4) was utilised through incorporating the benzenesulfonamide moiety of SLC-0111 (IV) at position 4 of the quinazoline ring. We have also incorporated various aromatic substitutions at positions 6 and 7 of the quinazoline scaffold including 3a, 4a‒f, 4h and 4j. These compounds tested the effects of different hydrophilic substitutions as in compounds 4b, 4d, 4h and 4j as well as the effect of hydrophobic substitutions as in compounds 3a, 4a, 4c, 4e and 4f. In addition to the difference in hydrophilicity and size of the substitutions, the substitutions chosen also possessed different electronic properties to establish key interactions within the roomy hCA binding sites. Thereafter, a regioisomerism strategy was applied to afford the meta-sulfamoyl ZBG derivatives, regioisomers 3b, 4i and 4k‒l. The hybridisation strategy incorporated the C-C bond from Lapatinib (IX) to attach the aromatic substitutions to increase the rigidity of the tail region in a similar manner to the Lapatinib. On the other hand, a flexible amino linker was used to link the quinazoline moiety with the sulphonamide moiety to increase the possibility of hydrogen bond formation as well as grant suitable flexibility to the sulphonamide region to bind easily with Zn metal of the active site.

Figure 4.

Design of the target hCAIs.

The target compounds designed herein were synthesised, characterised, and assessed for their hCA inhibitory activity against its four isoforms I, II, IX and XII. Then, the structure-activity relationship (SAR) was discussed. A molecular docking study was carried out to increase the understanding of the hCA inhibitory action of the target compounds.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Chemistry

2.1.1. General

In the conducted experiments all acquired solvents and reagents were applied without additional purification. Varian 400 MHz spectrometer (Varian Medical Systems, Inc., Palo Alto, CA, USA) was utilised to calculate the 1H NMR spectra with chemical shifts being measured in parts per million (ppm) and coupling constants in Hz. The high-resolution electrospray ionisation mass spectrometry (HR-ESIMS) data were assessed utilising a JMS–700 mass spectrometer (Jeol, Japan) or by HR-ESIMS data obtained via a G2 QTOF mass spectrometer. Reaction monitoring was carried out using TLC on 0.25 mm silica plates (E. Merck; silica gel 60 F254). Reverse-phase high performance liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC) was employed to determine the purity of the products, with the UV detector of the HPLC being set at 254 nm. The mobile phases employed were: (A) H2O containing 0.05% TFA and (B) CH3CN. The purity of the final compound was determined using a gradient of 75% B or 100% B in 30 min. The melting points were measured using a Fisherbrand digital melting point apparatus. Compounds 2a–b and 3a–d were synthesised as reported earlier34. The final target compounds were synthesised following the reported procedure of Suzuki cross-coupling reaction34.

4-((6-phenylquinazolin-4-yl)amino)benzenesulfonamide (4a)

Off-white solid, Yield: 35%, mp: 310‒312 °C, HPLC purity: 15 min, 98.56%, 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.14 (s, 1H), 8.85 (s, 1H), 8.66 (s, 1H), 8.21 (d, J = 12.0 Hz, 1H), 8.08 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 7.91–7.80 (m, 5H), 7.55 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 7.43 (t, J = 4.0 Hz, 1H), 7.29 (s, 2H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 158.09, 154.66, 149.76, 149.56, 142.71, 139.53, 138.85, 132.58, 129.50, 128.97, 128.47, 127.66, 126.75, 122.08, 120.95, 115.87. HRMS (ESI) m/z calculated for C20H17N4O2S [M + H]+: 377.1067, found: 377.1072.

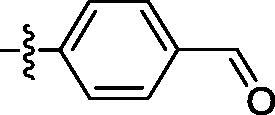

4-((6–(4-formylphenyl)quinazolin-4-yl)amino)benzenesulfonamide (4b)

Off-white solid, Yield: 46%, mp: 265‒267 °C, HPLC purity: 17 min, 94.26%, 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.20 (s, 1H), 10.08 (s, 1H), 8.97 (s, 1H), 8.68 (s, 1H), 8.30 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 8.13 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 8.10–8.04 (m, 4H), 7.92 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.84 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 7.28 (s, 2H). 13 C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 193.22, 158.23, 155.18, 150.20, 145.11, 142.58, 139.11, 137.24, 135.85, 132.56, 130.65, 129.19, 128.28, 126.78, 122.21, 115.88. HRMS (ESI) m/z calculated for C21H17N4O3S [M + H]+: 405.1016, found: 405.1021.

4-((6–(4-fluorophenyl)quinazolin-4-yl)amino)benzenesulfonamide (4c)

White solid, Yield: 26%, mp: 325‒327 °C, HPLC purity: 17 min, 95.19%, 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.13 (s, 1H), 8.82 (s, 1H), 8.66 (s, 1H), 8.19 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 8.07 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 7.95–7.79 (m, 5H), 7.39 (t, J = 12.0 Hz, 2H), 7.28 (s, 2H). 13 C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 163.87, 161.44, 158.07, 154.70, 149.55, 142.68, 138.98, 137.73, 136.04, 132.48, 129.74, 126.76, 122.08, 120.89, 116.46, 115.84. HRMS (ESI) m/z calculated for C20H16FN4O2S [M + H]+: 395.0973, found: 395.0977.

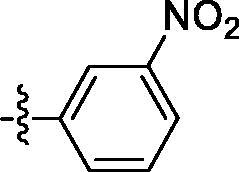

4-((6–(3-nitrophenyl)quinazolin-4-yl)amino)benzenesulfonamide (4d)

Off-white solid, Yield: 47%, mp: 335‒337 °C, HPLC purity: 17 min, 95.08%, 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.21 (s, 1H), 8.96 (s, 1H), 8.68 (s, 2H), 8.34–8.30 (m, 8.7 Hz, 3H), 8.07 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 7.93 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.87–7.81 (m, 3H), 7.29 (s, 2H). HRMS (ESI) m/z calculated for C20H16N5O4S [M + H]+: 422.0918, found: 422.0909.

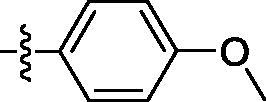

4-((6–(4-methoxyphenyl)quinazolin-4-yl)amino)benzenesulfonamide (4e)

Off-white solid, Yield: 40%, mp: 327‒329 °C, HPLC purity: 17 min, 96.57%, 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.10 (s, 1H), 8.78 (s, 1H), 8.64 (s, 1H), 8.17 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 8.07 (d, J = 12.0 Hz, 2H), 7.87‒7.80 (m, 5H), 7.27 (s, 2H), 7.10 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 3.82 (s, 3H). 13 C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 159.81, 157.97, 154.33, 149.23, 142.77, 138.90, 138.51, 132.25, 131.81, 128.81, 126.74, 122.04, 119.89, 115.91, 114.94, 55.74. HRMS (ESI) m/z calculated for C21H19N4O3S [M + H]+: 407.1172, found: 407.1171.

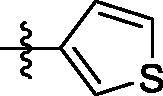

4-((6-(thiophen-3-yl)quinazolin-4-yl)amino)benzenesulfonamide (4f)

Off-white solid, Yield: 40%, mp: 259‒262 °C, HPLC purity: 15 min, 97.18%, 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.04 (s, 1H), 8.84 (s, 1H), 8.63 (s, 1H), 8.27 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 8.07 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 3H), 7.87–7.72 (m, 5H), 7.28 (s, 2H). 13 C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 157.96, 154.44, 149.43, 142.68, 140.98, 138.97, 133.82, 132.13, 128.92, 128.01, 126.86, 122.73, 122.08, 119.76, 115.88. HRMS (ESI) m/z calculated for C18H15N4O2S2 [M + H]+: 383.0631, found: 383.0626.

3-((6–(4-fluorophenyl)quinazolin-4-yl)amino)benzenesulfonamide (4g)

White solid, Yield: 54%, mp: 277‒279 °C, HPLC purity: 16 min, 100%, 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.16 (s, 1H), 8.86 (s, 1H), 8.65 (s, 1H), 8.37 (s, 1H), 8.24–8.17 (m, 2H), 7.99–7.86 (m, 3H), 7.65–7.57 (m, 2H), 7.42 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 4H). 13 C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 163.86, 161.42, 158.16, 154.75, 149.49, 144.89, 140.03, 137.67, 136.06, 132.38, 129.76, 128.96, 121.10, 120.87, 119.49, 116.46, 116.24, 115.75. HRMS (ESI) m/z calculated for C20H16FN4O2S [M + H]+: 395.0973, found: 395.0971.

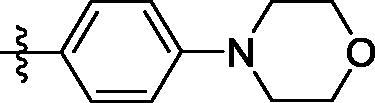

4-((6–(4-morpholinophenyl)quinazolin-4-yl)amino)benzenesulfonamide (4h)

Off- white solid, Yield: 42%, mp: 227‒229 °C, HPLC purity: 15 min, 95.27%, 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.12 (s, 1H), 8.78 (s, 1H), 8.65 (s, 1H), 8.20 (d, J = 12.0 Hz, 1H), 8.11 (d, J = 12.0 Hz, 2H), 7.87–7.81 (m, 5H), 7.30 (s, 2H), 7.12 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 3.79–3.77 (m, 4H), 3.23–3.21 (s, 4H).13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO- d6) δ 157.90, 154.12, 151.50, 149.07, 142.81, 138.86, 131.96, 129.71, 128.81, 128.16, 126.73, 122.03, 119.20, 115.79, 66.46, 48.48. HRMS (ESI) m/z calculated for C24H24N5O3S [M + H]+: 462.1594, found: 462.1592.

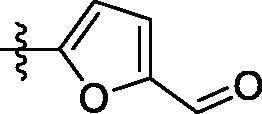

3-((6–(5-formylfuran-2-yl)quinazolin-4-yl)amino)benzenesulfonamide (4i)

Off-white solid, Yield: 28%, mp: 260‒262 °C, HPLC purity: 13 min, 95.09%, 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.38 (s, 1H), 9.69 (s, 1H), 9.08 (s, 1H), 8.67 (s, 1H), 8.35 (s, 2H), 8.19 (s, 1H), 7.92 (d, J = 12.0 Hz, 1H), 7.77 (d, J = 4.0 Hz, 1H), 7.62 (s, 2H), 7.48–7.39 (m, 3H). HRMS (ESI) m/z calculated for C19H15N4O4S [M + H]+: 395.0809, found: 395.0804.

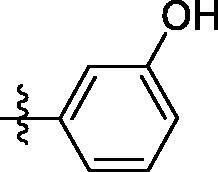

4-((7–(3-hydroxyphenyl)quinazolin-4-yl)amino)benzenesulfonamide (4j)

Yellow solid, Yield: 22%, mp: 312‒314 °C, HPLC purity: 13 min, 96.82%, 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.10 (s, 1H), 9.67 (s, 1H), 8.72–8.64 (m, 2H), 8.14 (d, J = 12.0 Hz, 2H), 7.97 (d, J = 12.0 Hz, 2H), 7.85 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 7.37–7.20 (m, 5H), 6.88 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H). 13 C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 158.44, 157.87, 155.14, 152.27, 145.32, 145.12, 142.84, 140.48, 140.28, 138.75, 136.71, 136.5, 130.55, 121.68, 118.48, 114.73, 114.22. HRMS (ESI) m/z calculated for C20H17N4O3S [M + H]+: 393.1016, found: 393.1009.

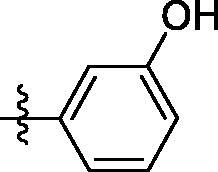

3-((7–(3-hydroxyphenyl)quinazolin-4-yl)amino)benzenesulfonamide (4k)

Off-white solid, Yield: 18%, mp: 302‒304 °C, HPLC purity: 15 min, 99.32%, 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.08 (s, 1H), 9.68 (s, 1H), 8.69–8.66 (m, 2H), 8.43 (s, 1H), 8.20 (s, 1H), 7.96 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 7.62–7.58 (m, 2H), 7.44–7.28 (m, 4H), 7.22 (s, 1H), 6.87 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H). HRMS (ESI) m/z calculated for C20H17N4O3S [M + H]+: 393.1016, found: 393.1010.

3-((6-phenylquinazolin-4-yl)amino)benzenesulfonamide (4l)

Off-white powder, Yield: 24%, mp: 327–329 °C, HPLC purity: 14 min, 99.81%, 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.16 (s, 1H), 8.89 (s, 1H), 8.65 (s, 1H), 8.37 (s, 1H), 8.24–8.21 (m, 2H), 7.91 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 3H), 7.60–7.57 (m, 4H), 7.50–7.40 (m, 3H). HRMS (ESI) m/z calculated for C20H17N4O2S [M + H]+: 377.1067, found: 377.1066.

2.2. Carbonic anhydrase inhibition study

The activity of the CA-catalyzed CO2 hydration reaction was evaluated employing an applied photophysics stopped-flow instrument. The indicator, Phenol red (at a concentration of 0.2 mM) was added to the CA-catalyzed CO2 hydration reaction after a period of 10–100 s. Phenol red functioned at an absorbance maximum of 557 nm, with 20 mM Hepes (pH 7.4) and 10 mM NaClO4 (to retain constant ionic strength)35. A CO2 concentration ranging between 1.7 and 17 mM was employed to evaluate the kinetic parameters and inhibition constants33. A minimum of six traces of the starting 5–10% of the reaction were analysed to measure the initial velocity for each inhibitor. In a similar manner, the uncatalyzed rates were evaluated and subtracted from the overall calculated rates36. Stock inhibitor solutions (10 mM) were prepared in distilled–deionized water, and dilutions up to 0.01 nM were prepared with distilled–deionized water after that. Preincubation of the inhibitor enzyme solutions at room temperature to enable the formation of the E-I complex was carried out for 15 min before starting the experiment. The inhibition constants were determined employing PRISM 3, while the kinetic parameters for the uninhibited enzymes were calculated using Lineweaver-Burk plots that comprise the mean of at least three separate measurements with errors ranging to ±5–10% of the stated values37,38.

2.3. Molecular docking study

The crystal structures of carbonic anhydrase isoforms hCA I (PDB code: 6Y00, resolution 1.37 Å)39, hCA II (PDB ID: 4BF1, resolution 1.35 Å)40, hCA IX (PDB code: 4Z0Q, resolution 1.45 Å)41 and hCA XII (PDB code: 1JD0, resolution 1.50 Å)42 were obtained from the Protein Data Bank (www.pdb.org). The downloaded crystal structure was prepared using the Schrodinger 2021 suite package’s preparation wizard with the default settings and pH value of 7.4. ChemDraw Professional 17.0 was employed to sketch the ligands, which were then exported in the structure data file format (SDF) and sent to the Ligprep module. The Schrodinger Ligprep module was then utilised in the ligand preparation process to further optimise the geometry. Glide’s extra precision module was used to dock the minimised ligands inside the binding cavity of the appropriate crystal structure, generating 10 poses per docked ligand. The pose with the most negative docking score was chosen to display.

3. Results and discussion

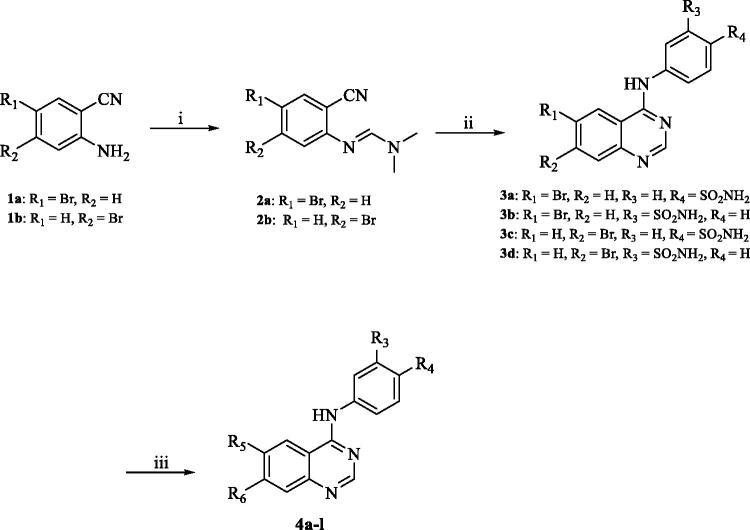

3.1. Chemical synthesis

Scheme 1 depicts the synthetic route utilised to produce the target compounds 4a–l. Refluxing of 2-amino-5-bromobenzonitrile (1a) or 2-amino-4-bromobenzonitrile (1b) with N,N-dimethylformamide dimethyl acetal (DMF-DMA) yielded intermediates 2a–b. Compounds 3a–d were synthesised by reacting the appropriate sulphonamide with the intermediates 2a–b in glacial acetic acid (GAA) under reflux. Using Suzuki reaction compounds 3a–d were subsequently reacted with the suitable boronic acid derivative employing the coupling catalyst Pd(amphos)C12 and the inorganic base T3P (propylphosphonic anhydride) dissolved in dioxane and water at 80 °C under pressure in the presence of nitrogen to produce compounds 4a–l. The chemical structures and purity of the synthesised target compounds were determined using NMR, HRMS, and HPLC analytical techniques43–45. The 1H NMR spectra of compounds 3a‒d exhibited a characteristic peak at the range of 7.20–7.50 ppm which can be attributed to the sulphonamide NH2 and a second peak at 10.10–10.30 ppm attributable to the NH of the amide group verifying the successful synthesis of the intermediates 3a–d from their parent compounds 2a–b. Suzuki cross-coupling reactions success was verified by the presence of the appropriate characteristic peaks in the 1H NMR spectra of compounds 4a–l. For example, compound 4b 1H NMR spectra was characterised by the appearance of a new singlet peak at 10.20 ppm attributable to the carbonyl moiety. Similarly, compound 4i was characterised by the appearance of new singlet peak at 10.38 ppm due to the carbonyl group of the tetrahydrofuran-2-carbaldehyde moiety. In a similar manner, the synthesis of compounds 4j and 4k was confirmed by the appearance of a singlet peak at 10.10 and 10.14 ppm, respectively, attributable to the hydroxy group of the phenol moiety. Compound 4e synthesis was confirmed by the presence of a singlet peak at 3.82 ppm attributable to the three hydrogens of the methoxy group. Likewise, the appearance of two multiple peaks in the aliphatic region of the 1H NMR spectrum of compound 4h attributable to the eight hydrogens of the morpholine ring confirmed its successful synthesis.

Scheme 1.

Reagents and conditions: (i) DMF-DMA, 100 °C, 1.5 h; (ii) appropriate aniline, GAA, reflux, 2 h; (iii) suitable boronic acid derivative, Pd(amphos)C12, T3P, dioxane, 80 °C, 2 h (For 4a–l, R5 and R6 are described in detail in Table 1).

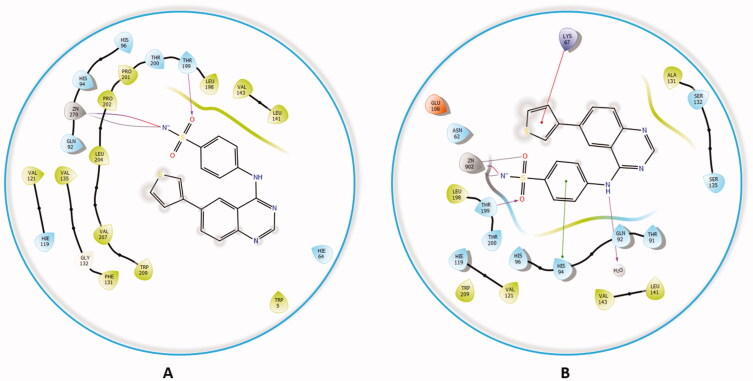

3.2. Carbonic anhydrase inhibition study

As indicated in Table 1, the biological evaluation of CA inhibitory activities of compounds 3a–b, 4a–l and AAZ as a standard inhibitor, was performed on a panel of four hCA isoforms by a stopped flow CO2 hydrase assay. This panel comprised the two ubiquitously expressed cytosolic hCA I and II isoforms, along with the two tumour-related transmembrane hCA IX and XII isoforms. With respect to the first cytosolic isoform (hCA I) the structural hybrid compounds 3a, 4e, 4f showed greater inhibitory activities when compared with the standard AAZ, which possessed an inhibition constant (Ki) of 250.0 nM, exhibiting inhibitory activity of 89.4, 91.2 and 60.9 nM, respectively. In all three compounds the substitution at the 6- position of the aromatic quinazoline ring was occupied by a hydrophobic substituent and the sulphonamide moiety was in the para position. Interestingly, compound 3a analogue, Compound 3b, with a meta-substituted sulphonamide, lost all activity against the first cytosolic isoform hCA I. Similarly, other quinazolines with a hydrophilic “tail” or a meta-substituted sulphonamides lost all inhibitory activity against hCA I. As such the SAR of the synthesised hybrids against the first cytosolic isoform (hCA I) can be summarised in Figure 5(A).

Table 1.

The inhibitory activity (Ki) of the synthesised hybrids against hCA I, II, IX and XII isoforms

| ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cpd | R3 | R4 | R5 | R6 | Ki (nM) |

|||

| hCA I | hCA II | hCA IX | hCA XII | |||||

| 3a | H | SO2NH2 | Br | H | 89.4 | 8.7 | 174.0 | 46.5 |

| 3b | SO2NH2 | H | Br | H | 7102 | 5758 | 95.3 | 39.4 |

| 4a | H | SO2NH2 |

|

H | 600.0 | 2.4 | 180.3 | 65.7 |

| 4b | H | SO2NH2 |

|

H | 650.7 | 303.8 | 86.9 | 67.4 |

| 4c | H | SO2NH2 |

|

H | 931.4 | 47.1 | 559.6 | 93.0 |

| 4d | H | SO2NH2 |

|

H | 588.2 | 55.7 | 265.3 | 90.7 |

| 4e | H | SO2NH2 |

|

H | 91.2 | 4.6 | 86.9 | 77.0 |

| 4f | H | SO2NH2 |

|

H | 60.9 | 37.1 | 86.5 | 89.5 |

| 4g | SO2NH2 | H |

|

H | 3125 | 231.0 | 229.0 | 30.5 |

| 4h | H | SO2NH2 |

|

H | 548.4 | 112.3 | 336.8 | 49.8 |

| 4i | SO2NH2 | H |

|

H | 5583 | 2419 | 487.9 | 52.7 |

| 4j | H | SO2NH2 | H |

|

361.3 | 66.3 | 244.8 | 66.7 |

| 4k | SO2NH2 | H | H |

|

4680 | 2525 | 90.3 | 69.7 |

| 4l | SO2NH2 | SO2NH2 |

|

H | 6565 | 678.3 | 88.8 | 89.4 |

| AAZ | – | – | – | – | 250.0 | 12.1 | 25.7 | 5.7 |

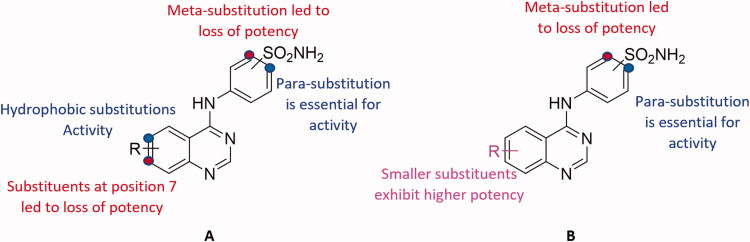

Figure 5.

The predicted SAR of the synthesised hybrids against hCA I (A) and hCA II (B) isoforms.

Similarly, compounds 3a, 4e and 4f showed potent inhibition for the physiologically dominant isoform hCA II with inhibitory concentrations of 8.7, 4.6 and 37.1 nM, respectively. Furthermore, compounds 4a, 4c and 4j exhibited inhibitory potent activities of 2.4, 47.1 and 66.3 nM, respectively. These results indicate that the positioning of the sulphonamide group is essential for determining the activity, with para-substituted sulphonamides being essential for activity. This conclusion was further verified by the loss of activity of compounds 3b, 4k and 4l when compared to their respective potent analogues 3a, 4a and 4j, respectively. Conversely, the nature of the aromatic substitution at positions 6 and 7 of the quinazoline ring, did not affect activity, with both hydrophilic and hydrophobic substitutions showing promising activity against hCA II isoform. However, the smaller substituents exhibited higher potency when compared to larger ones. The predicted SAR for the synthesised hybrids against hCA II isoform is illustrated in Figure 5(B).

All synthesised hybrid compounds demonstrated significant inhibitory activity for the tumour associated isoforms hCA IX and XII. Among the synthesised compounds, 4f exhibited the highest potency against hCA IX (Ki of 86.5 nM), while compound 3b was the most potent of the synthesised hybrids against hCA XII, with an inhibitory concentration of 39.4 nM.

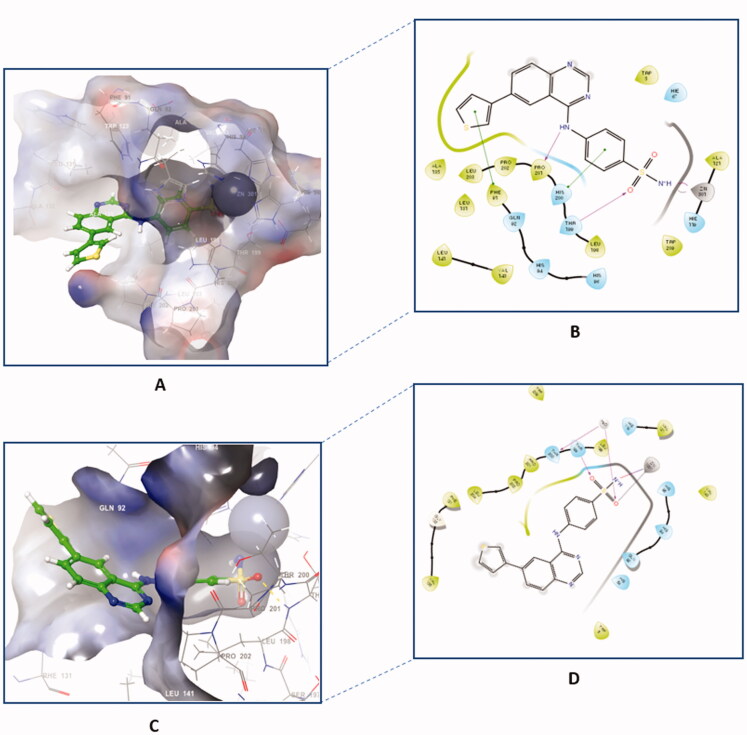

3.3. Molecular docking study

In computer-aided drug design research, the prediction of binding modes of a ligand and its proposed target, in addition to the correlation of the obtained scores with prospective activity, are all useful applications of molecular docking46. Another benefit of molecular docking studies is the ability to predict the effect of specific amino acid mutations on the activity profile of the ligand47. Furthermore, visualising the docking study’s consequent interactions assists future ligand modification, leading to compounds possessing improved binding characteristics48. Hence, the synthesised hybrids were subjected to a molecular docking study against hCA I, II, IX and XII isozymes to correlate the structural characteristic features with the reported inhibitory activity and examine the binding profile of the synthesised hybrids. Generally, the co-crystalized ligands in hCA isoforms I and II and IX exhibited the typical sulphonamide moiety pattern, where the sulphonamide moiety binds to the zinc(II) ion following the displacement of the metal-bound water molecule to establish the tetrahedral adduct with the zinc atom49.

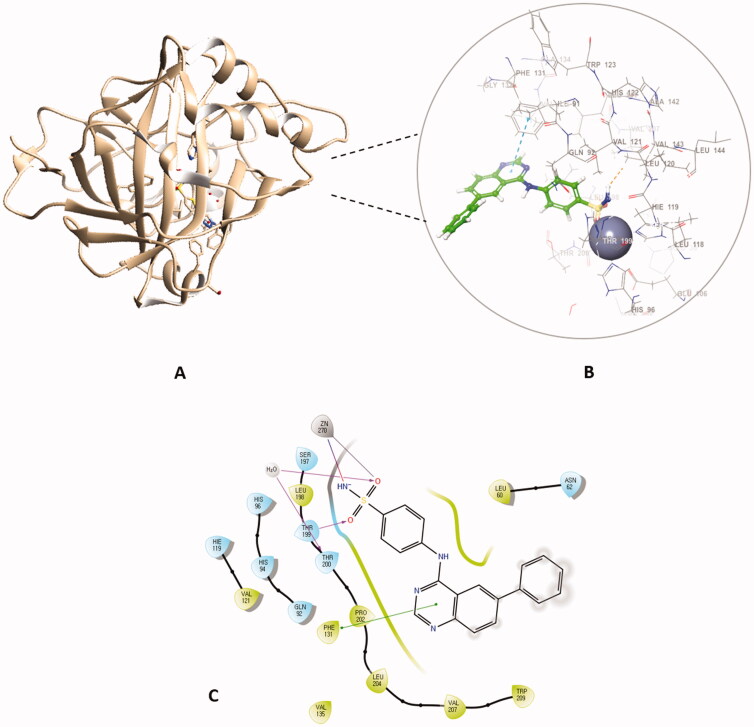

Out of the synthesised hybrids the compounds exhibiting the highest activity, compounds 4a and 4f, were subjected to a molecular docking study. Among the synthesised hybrids, compound 4f exhibited the highest potency against both the hCA I and IX isoforms with inhibitory activity of 60.9 nM and 86.5 nM, respectively. Compound 4f (60.9 nM), adhered to the general pattern of the benzenesulfonamide ring fitting deeply within the shallow CA active site through the anchoring the zinc atom in a characteristic manner for sulphonamide CAIs through an NH- and Zn2+ bond. In addition to the typical zinc metal-ligand interactions compound 4f formed a hydrogen bond between the carbonyl moiety of the sulphonamide moiety and THR199 of the active site (Figure 6(B)). Compound 4f exhibited another hydrogen bond between the amide moiety (NH) and PRO201 amino acid residues. Moreover, compound 4f established two π‒π interactions with PHE91 and HIS200 amino acid residues, further increasing the compound’s affinity to the active site. Compound 4f was equally potent against hCA IX, which was due to the formation of two metal interactions between the sulphonamide group and the zinc atom of the active site. Furthermore, compound 4f established a hydrogen bond with THR199 and weak hydrophobic interactions with the amino acid residues of the active site (Figure 6(D)).

Figure 6.

The binding patterns of compound 4f inside the binding cavity of hCAI and IX. (A) 3D model of the crystal structure of hCA I with compound 4f. (B) 2D interaction pattern of compound 4f with hCA I binding cavity. (C) 3D model of the crystal structure of hCA IX with compound 4f. (D) 2D interaction pattern of compound 4f with hCA IX binding cavity.

The docking of compound 4f against hCA II and XII isoforms revealed a similar interaction pattern, with the sulphonamide moiety fitted deeply inside the binding site groove. Furthermore, compound 4f established a hydrogen bond interaction with THR199 amino acid residue of hCA II and XII active sites (Figure 7), indicating that the formation of a hydrogen bond with THR199 is essential for the activity of carbonic anhydrase inhibitors. The potent inhibitory activity of compound 4f (Ki = 89.5 nM) can be further explained through the compound’s ability to establish an additional π-cation bond with LYS67 as well as a π-π stacking interaction with HIS94 (Figure 7(B)). The 2D interaction pattern of compound 4f with hCA II and XII is illuminated in Figure 7, while the corresponding 3D models are demonstrated in the Supplementary file (Figure S4.1‒2).

Figure 7.

The 2D interaction patterns of compound 4f with hCA II (A) and XII (B). Favourable interactions are colour coded as follows: purple‒hydrogen bond, grey‒metal bond, red‒π-cation interaction, green‒π‒π stacking interactions. The light green lines represent weak van der Waals interactions.

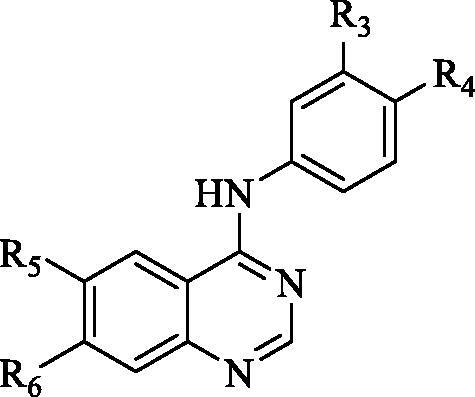

Comparably, compound 4a, which possessed the highest potency against the hCA II isoform (Ki = 2.4 nM) when docked in the active site hCA II, formed the typical metal interaction of the sulphonamide group with the Zn metal as well as a hydrogen bond with THR199 and π-π stacking interaction between the quinazoline ring and PHE131 (Figure 8). The interaction of compound 4a against the remaining isoforms is illustrated in the Supplementary file.

Figure 8.

The docked complex of compound 4a with hCA II isoform. (A) 3D model of the crystal structure of hCA II with compound 4a, (B) 3D docking pose of compound 4a, favourable interactions are exhibited as dashed lines: orange‒hydrogen bonds, blue‒π-π stacking, (C) 2D interaction pattern of compound 4a with hCA II binding cavity, favourable interactions are colour coded as follows: green‒π-π stacking, purple‒hydrogen bonds, grey‒metal interactions and light green‒weak van der Waals interactions.

4. Conclusion

Herein, the design, synthesis, and characterisation of a novel series of quinazoline-based sulphonamides were reported and their activities against hCA I, II, IX and XII isoforms were assessed. Most of the newly synthesised quinazoline sulphonamide hybrids efficiently inhibited the investigated hCA I, II, IX and XII, with inhibitory activity in the single digit nanomolar range. Among the synthesised compounds, compound 4f possessed the highest potency against hCA I and IX isoforms with a Ki of 60.9 nM and 86.5 nM, respectively. Against the hCA II isoform, compound 4a displayed the highest inhibitory activity of 2.4 nM. Compound 4g was the most potent inhibitor against hCA XII with Ki of 30.5 nM. Additionally, compounds 3a and 4b possessed single digit inhibitory activity against hCA II of 8.7 and 4.6 nM, respectively. Compounds 3a and 4e were able to inhibit hCA I at concentrations of 89.4 and 91.2 nM, which is more potent when compared to the inhibitory concentration of the standard Acetazolamide (250 nM). Furthermore, all tested compounds displayed potent activity against the hCA XII isoform, with inhibitory activities ranging from 30.5‒93 nM. The SAR of the synthesised hybrids were predicted based on the obtained biological data. Finally, a molecular docking study was conducted to provide insights on the binding interactions of the most potent compound for each tested hCA isoform.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

A.E. expresses his gratitude to the Korea Institute of Science and Technology (KIST) for partially supporting this work through the “2022 KIST School Partnership Project,” and he would like to thank the Technology Innovation Commercial Office (TICO) at Mansoura University for their highly effective contribution to the project’s success. M.H.A. would like to thank Taif University Researchers Project number (TURSP-2020/91), Taif University, Taif, Saudi Arabia.

Funding Statement

This study was supported by a National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean government (MSIT) [No. 2018R1A5A2023127] and the BK21 FOUR program funded by the Ministry of Education of Korea through NRF.

Disclosure statement

CT Supuran is Editor-in-Chief of the Journal of Enzyme Inhibition and Medicinal Chemistry. He was not involved in the assessment, peer review, or decision-making process of this paper. The authors have no relevant affiliations of financial involvement with any organisation or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

References

- 1.Supuran CT, Scozzafava A.. Carbonic anhydrases as targets for medicinal chemistry. Bioorg Med Chem 2007;15:4336–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Supuran CT. Carbonic anhydrases: novel therapeutic applications for inhibitors and activators. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2008;7:168–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Topal F, Aksu K, Gulcin I, et al. . Inhibition profiles of some symmetric sulfamides derived from phenethylamines on human carbonic anhydrase I, and II isoenzymes. Chem Biodivers 2021;18:e2100422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Durdagi S, Şentürk M, Ekinci D, et al. . Kinetic and docking studies of phenol-based inhibitors of carbonic anhydrase isoforms I, II, IX and XII evidence a new binding mode within the enzyme active site. Bioorg Med Chem 2011;19:1381–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nocentini A, Donald WA, Supuran CT.. Chapter 8 – human carbonic anhydrases: tissue distribution, physiological role, and druggability. In: Supuran CT, Nocentini A, eds. Carbonic anhydrases. Cambridge: Academic Press; 2019:151–185. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Quade BN, Parker MD, Occhipinti R.. The therapeutic importance of acid-base balance. Biochem Pharmacol 2021;183:114278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Supuran CT, Scozzafava A.. Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors and their therapeutic potential. Expert Opin Ther Pat 2000;10:575–600. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mohamed MM, Sloane BF.. Cysteine cathepsins: multifunctional enzymes in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2006;6:764–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Annan DA, Maishi N, Soga T, et al. . Carbonic anhydrase 2 (CAII) supports tumor blood endothelial cell survival under lactic acidosis in the tumor microenvironment. Cell Commun Signal 2019;17:169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cuffaro D, Nuti E, Rossello A.. An overview of carbohydrate-based carbonic anhydrase inhibitors. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem 2020;35:1906–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Awadallah FM, Bua S, Mahmoud WR, et al. . Inhibition studies on a panel of human carbonic anhydrases with N1-substituted secondary sulfonamides incorporating thiazolinone or imidazolone-indole tails. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem 2018;33:629–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Supuran CT. Experimental carbonic anhydrase inhibitors for the treatment of hypoxic tumors. J Exp Pharmacol 2020;12:603–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sanku RKk. Development and biological evaluation of carbonic anhydrase modulators as potential nootropics and anticancer agents. Ann Arbor: Temple University; 2018, pp. 154. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Supuran CT. Advances in structure-based drug discovery of carbonic anhydrase inhibitors. Expert Opin Drug Discov 2017;12:61–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Supuran CT. Exploring the multiple binding modes of inhibitors to carbonic anhydrases for novel drug discovery. Expert Opin Drug Discov 2020;15:671–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aggarwal M, Kondeti B, McKenna R.. Insights towards sulfonamide drug specificity in α-carbonic anhydrases. Bioorg Med Chem 2013;21:1526–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carta F, Supuran CT, Scozzafava A.. Sulfonamides and their isosters as carbonic anhydrase inhibitors. Future Med Chem 2014;6:1149–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McDonald PC, Chia S, Bedard PL, et al. . A phase 1 study of SLC-0111, a novel inhibitor of carbonic anhydrase IX, in patients with advanced solid tumors. Am J Clin Oncol 2020;43:484–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hampson AJ, Babalonis S, Lofwall MR, et al. . A pharmacokinetic study examining acetazolamide as a novel adherence marker for clinical trials. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2016;36:324–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yuan L, Wang M, Liu T, et al. . Carbonic anhydrase 1-mediated calcification is associated with atherosclerosis, and methazolamide alleviates its pathogenesis. Front Pharmacol, 2019;10:766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yu-Jing YJ, Zhang CM, Liu ZP.. Recent developments of small molecule EGFR inhibitors based on the quinazoline core scaffolds. Anticancer Agents Med Chem 2012;12:391–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Elkamhawy A, Farag AK, Viswanath AN, et al. . Targeting EGFR/HER2 tyrosine kinases with a new potent series of 6-substituted 4-anilinoquinazoline hybrids: design, synthesis, kinase assay, cell-based assay, and molecular docking. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 2015;25:5147–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cohen MH, Williams GA, Sridhara R, et al. . FDA drug approval summary: gefitinib (ZD1839) (Iressa) tablets. The Oncologist 2003;8:303–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johnson JR, Cohen M, Sridhara R, et al. . Approval summary for erlotinib for treatment of patients with locally advanced or metastatic non-small cell lung cancer after failure of at least one prior chemotherapy regimen. Clin Cancer Res 2005;11:6414–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cortazar P, Justice R, Johnson J, et al. . US Food and Drug Administration approval overview in metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:1705–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang D, Pal A, Bornmann WG, et al. . Activity of lapatinib is independent of EGFR expression level in HER2-overexpressing breast cancer cells. Mol Cancer Ther 2008;7:1846–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Degrauwe N, Sosa JA, Roman S, Deshpande HA.. Vandetanib for the treatment of metastatic medullary thyroid cancer. Clin Med Insights Oncol 2012;6:CMO.S7999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tan F, Shi Y, Wang Y, et al. . Icotinib, a selective EGF receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor, for the treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer. Future Oncol 2015;11:385–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yu HA, Pao W.. Targeted therapies: Afatinib-new therapy option for EGFR-mutant lung cancer. Nature Rev Clin Oncol 2013;10:551–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Asif M. Chemical characteristics, synthetic methods, and biological potential of quinazoline and quinazolinone derivatives. Int J Med Chem 2014;2014:395637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Elkamhawy A, Viswanath AN, Pae AN, et al. . Discovery of potent and selective cytotoxic activity of new quinazoline-ureas against TMZ-resistant glioblastoma multiforme (GBM). Eur J Med Chem 2015;103:210–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alafeefy AM, Ceruso M, Al-Tamimi A-MS, et al. . Quinazoline-sulfonamides with potent inhibitory activity against the α-carbonic anhydrase from Vibrio cholerae. Bioorg Med Chem 2014;22:5133–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alafeefy AM, Ceruso M, Al-Jaber NA, et al. . A new class of quinazoline-sulfonamides acting as efficient inhibitors against the α-carbonic anhydrase from Trypanosoma cruzi. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem 2015;30:581–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee K, Nada H, Byun HJ, et al. . Hit identification of a Novel quinazoline sulfonamide as a promising EphB3 inhibitor: design, virtual combinatorial library, synthesis, biological evaluation, and docking simulation studies. Pharmaceuticals. 2021;14:1247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maresca A, Temperini C, Vu H, et al. . Non-zinc mediated inhibition of carbonic anhydrases: coumarins are a new class of suicide inhibitors. J Am Chem Soc 2009;131:3057–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Menchise V, De Simone G, Alterio V, et al. . Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors: stacking with Phe131 determines active site binding region of inhibitors as exemplified by the X-ray crystal structure of a membrane-impermeant antitumor sulfonamide complexed with isozyme II. J Med Chem 2005;48:5721–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Margheri F, Ceruso M, Carta F, et al. . Overexpression of the transmembrane carbonic anhydrase isoforms IX and XII in the inflamed synovium. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem 2016;31:60–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bozdag M, Ferraroni M, Nuti E, et al. . Combining the tail and the ring approaches for obtaining potent and isoform-selective carbonic anhydrase inhibitors: solution and X-ray crystallographic studies. Bioorg Med Chem 2014;22:334–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ali M, Bozdag M, Farooq U, et al. . Benzylaminoethyureido-tailed benzenesulfonamides: design, synthesis, kinetic and X-ray investigations on human carbonic anhydrases. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:2560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Leitans J, Sprudza A, Tanc M, et al. . 5-Substituted-(1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)thiophene-2-sulfonamides strongly inhibit human carbonic anhydrases I, II, IX and XII: solution and X-ray crystallographic studies. Bioorg Med Chem 2013;21:5130–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Buemi MR, De Luca L, Ferro S, et al. . Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors: design, synthesis and structural characterization of new heteroaryl-N-carbonylbenzenesulfonamides targeting druggable human carbonic anhydrase isoforms. Eur J Med Chem 2015;102:223–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Whittington DA, Waheed A, Ulmasov B, et al. . Crystal structure of the dimeric extracellular domain of human carbonic anhydrase XII, a bitopic membrane protein overexpressed in certain cancer tumor cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:9545–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Elkamhawy A, Kim NY, Hassan AHE, et al. . Design, synthesis and biological evaluation of novel thiazolidinedione derivatives as irreversible allosteric IKK-β modulators. Eur J Med Chem 2018;157:691–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Park JE, Elkamhawy A, Hassan AHE, et al. . Synthesis and evaluation of new pyridyl/pyrazinyl thiourea derivatives: neuroprotection against amyloid-β-induced toxicity. Eur J Med Chem 2017;141:322–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Al-Sanea MM, Elkamhawy A, Zakaria A, et al. . Synthesis and in vitro screening of phenylbipyridinylpyrazole derivatives as potential antiproliferative agents. Molecules 2015;20:1031–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Macalino SJY, Gosu V, Hong S, Choi S.. Role of computer-aided drug design in modern drug discovery. Arch Pharm Res 2015;38:1686–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Guedes IA, de Magalhães CS, Dardenne LEJBr. Receptor-ligand molecular docking. Biophys Rev. 2014;6:75–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang J, Li Y, Yang Y, et al. . In silico research to assist the investigation of carboxamide derivatives as potent TRPV1 antagonists. Mol BioSystems 2015;11:2885–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shaldam M, Nocentini A, Elsayed ZM, et al. . Development of novel Quinoline-based sulfonamides as selective cancer-associated carbonic anhydrase isoform IX inhibitors. Int J Mol Sci 2021;22:11119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.