Abstract

Rationale and Objectives:

Tubular secretion plays an important role in the efficient elimination of endogenous solutes and medications, and lower secretory clearance is associated with risk of kidney function decline. We evaluated whether histopathologic quantification of interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy (IFTA) was associated with lower tubular secretory clearance in persons undergoing kidney biopsy.

Study Design:

Cross sectional

Settings and Participants:

The Boston Kidney Biopsy Cohort is a study of persons undergoing native kidney biopsies for clinical indications.

Exposures:

Semi-quantitively score of IFTA reported by two trained pathologists.

Outcomes:

We measured plasma and urine concentrations of nine endogenous secretory solutes using a targeted liquid chromatography mass-spectroscopy assay. We used linear regression to test associations of urine to plasma ratios (UPR) of these solutes with IFTA score after controlling for estimated GFR (eGFR) and albuminuria.

Results:

Among 418 persons, the mean age was 53 years, 51% were women, 64% were White and 18% were Black. The mean eGFR was 50 ml/min/1.73m2 and median album/creatinine ratio was 819 mg/g. Compared to individuals with ≤25% IFTA, those with >50% IFTA had 12 to 37% lower UPR for the all 9 secretory solutes. Adjusting for age, sex, race, eGFR and urinary albumin and creatinine attenuated the associations, yet trend of lower secretion across groups remained statistically significant (p for trend <0.05) for 7 of 9 solutes. A standardized composite secretory score incorporating UPR for all 9 secretory solutes using the min-max method showed similar results (p for trend <0.05).

Limitations:

Single time point and spot measures of secretory solutes

Conclusions:

Greater IFTA severity is associated with lower clearance of endogenous secretory solutes even after adjusting for eGFR and albuminuria.

Keywords: kidney tubule, secretion, clearance, solute, biomarker, biopsy, fibrosis, tubular atrophy, acute tubular injury

INTRODUCTION

For over 70 years, serum creatinine has remained the mainstay to estimate kidney function.1 An important limitation of serum creatinine and its derivative estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) equations is that serum creatinine may be low in persons with low muscle mass, especially in the elderly, thereby underestimating the severity of kidney disease.2 However, tubular cells perform several important functions, including reabsorption of filtered nutrients, production of key hormones, regulation of acid/base balance and secretion of endogenous toxins and medications. These tubular characteristics are unlikely to be fully accounted by measurements of GFR or albuminuria alone. There is an important need to develop a multidimensional approach to assess kidney functions beyond GFR and albuminuria.

The proximal tubules efficiently eliminate endogenous solutes and medications via energy dependent mechanisms that drive secretion through specialized transporters.3 Tubular secretory clearance can be assessed by the infusion of exogenous tracers, such as para-amino hippuric acid (PAHA) or mercaptoacetyltriglycine (MAG3). However, infusion studies are currently impractical for routine clinical care. Several endogenously producd small solutes are excreted primarily by tubular secretion and accumulate in the plasma of patients with end-stage kidney disease (ESKD).4 Many of these solutes are putative uremic toxins as described the European Uremic Toxin Work Group,5 are bound to plasma proteins, and therefore are not efficiently removal by glomerular filtration. Further, our groups had previously selected these organic solutes based on a review of medical literature indicating specificity for OAT1/3 transporters in the proximal tubules, an increase in circulating levels in rodent models following OAT1/3 knockout, a high degree of protein binding, low diurnal variation in plasma, and/ or higher kidney clearance rates than GFR or creatinine clearance.6 Low clearances of these secretory solutes are associated with greater risks of kidney disease progression independent of eGFR or albuminuria, which are traditional markers of glomerular filtration and injury. This indicates that secretion may provide novel insights into the health and function of the kidney above and beyond the standard clinical markers of kidney function.6 7

Interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy (IFTA) constitute the shared final pathway in nearly all forms of kidney disease,7-9 predicts progression to ESKD,10 and its severity is not entirely captured by eGFR or albuminuria.9 Thus IFTA is common and prognostically important, but invisible to clinicians, except in rare instances when without a biopsyies are performed. We hypothesized that biopsy evidence of IFTA severity would be associated with the kidney clearances of endogenous secretory solutes. Demonstrating this association between secretory solutes and IFTA may provide a non-invasive insight to tubule cell dysfunction with fibrosis.

METHODS

Study Population

The Boston Kidney Biopsy Cohort (BKBC) is a prospective cohort study of patients undergoing native kidney biopsy for clinical indications at three tertiary care hospitals in Boston, Massachusetts. The details have been published previously.11 Enrollment criteria included included adult patients (≥18 years andof age) who underwent a clinically indicated native kidney biopsy between September 2006 and June 2016. Exclusion criteria included severe anemia, pregnancy, the inability to provide consent, severe anemia, pregnancy and enrollment in competing studies. All participants provided written informed consent. The study protocol was approved by the Partners Human Research Committee (the Brigham and Women’s Hospital Institutional Review Board), and is in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

For the purpose of this analysis, the overall analytical sample pooled participants selected for two separate studies. 200 samples were randomly selected to evaluate the association of IFTA with secretory solute clearance (Study 1). 347 samples were selected as part of a separate study (Study 2) to evaluate the association of biopsy diagnosed kidney disease with secretory solute clearance. To be eligible for study 2, we selected pathologic diagnoses with at least ten occurrences. To improve statistical power, these 347 samples were combined with the 200 random samples that were selected to evaluate the association of IFTA with tubular secretion (Supplementary Figure 1). This resulted in an analytical cohort of 424 participants who were enrolled in the BKBC.

Histopathology Measures

Briefly, all biopsies were adjudicated under light microscopy by two kidney pathologists who provided semi-quantitative scores of kidney inflammation, fibrosis, vascular sclerosis, and tubular injury (Supplemental Table 1).11 The scoring system for individual histopathologic lesions was developed by the pathologists for use in this study on the basis of their review of the literature and clinical experience. Both pathologists reviewed the light microscopy slides alongside one another and verbally provided semiquantitative scores of kidney inflammation, fibrosis, vascular sclerosis, and tubular injury severity in the presence of A.S. and/or S.S.W. If they did not initially agree, the case was discussed in more detail to obtain consensus on individual histopathologic lesion severity.

The primary exposure was a standardized semi-quantitative assessment of IFTA (≤25%, 26 to 50%, and > 50%) assessed through trichrome-stained biopsies similar to that used in the Banff classification.12 In our cohort, only 4% of samples had no IFTA and therefore were combined with the group having ≤25% IFTA. To test the reproducibility of the adjudicated scores, study pathologists rescored 26 selected kidney biopsies several months after their initial review. The weighted kappa statistic for within reader variablitiy was was 0.72 (0.52–0.93) for IFTA. Scores were identical between pathologists in 8/10 biopsies differing by 1 category in the others. A secondary exposure was acute tubular injury (ATI), which was also semi-quantitatively scored into 4 categories (none, mild, moderate and severe).

Secretory solute measures

All BKBC participants provided a blood and spot urine sample on the day of the biopsy. We measured total concentrations of nine endogenous endogenous solutes suspected to be eliminated primarily by proximal tubular secretion: hippurrate, pyridoxic acid, isovalerylglycine, tiglylglycine, kynurenic acid, cinnamoylglycine, xanthosine, indoxyl sulfate, and p-cresol sulfate. Plasma samples underwent solid phase extraction after precipitation in organic solvent, and urine samples underwent two consecutive solid phase extractions (HLB or MCX μElution plates, Waters).13, 14 Reconstituted dried extracts were filtered through a large-pore filter plate (Millipore, MSBVN1210) to remove particulates before analysis by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (Shimadzu and Sciex). Data were normalized based on stable isotope-labeled solutes added to each well. Calibration was achieved by a single point calibration approach using pooled human serum and urine. All measurements greatly exceeded the lower limits of detection. Intra- and inter-assay coefficients of variation ranged from 3.4% - 14.5% in plasma and 4.5% - 10.1% in urine.

All plasma measurements represent total solute concentrations, not bound or unbound fractions. We calculated the urine to plasma ratio of each solute (UPR) as Ux/Px, where Ux represents the spot urine concentration of solute X, and Px represents the plasma concentration.

Covariates

We collected patient information at the biopsy visit, including age, race and sex. We measured serum cystatin-C concentrations using the Gentian assay and urine albumin and creatinine concentrations using standard chemistry reagents, on the Beckman DxC instrument. The CKD-Epi cystatin-C equation was used to estimate GFR.15

Statistical Analysis

We stratified participants by categories of IFTA score and reported means and frequencies as appropriate. We used linear regression to quantify differences in the UPR of each secretory solute across categories of IFTA and ATI; the lowest category of IFTA (≤25%) and ATI (none) served as the reference groups.12 To express results as proportionate differences we log-transformed the dependent variable, UPR, prior to entry into the model. We adjusted regression models for age, sex, race, eGFR, and the urine albumin and urine creatinine. We used a test-for-trend to compute p-values for differences in UPR across categories of IFTA and ATI.

To create a singular metric for expressing the individual UPRs, we first standardized each of these values to a common 1-100 scale using the min-max method where min (UPRx) represents the minimum measured UPR value for solute X in the study distribution, max (UPRx) represents the maximum value, and range (UPRx) represents the difference between the minimum and maximum values.

We then averaged these standardized UPR scores for of all nine solutes to create a composite secretion index. Finally, we compared the difference in composite secretion score within each of the IFTA categories compared to participants with <25% IFTA after adjusting for the covariates listed in the models above. A similar analysis was performed with ATI as our secondary exposure of interest. Models were adjusted identically as stated for the IFTA analyses. All statistical analyses were evaluated using the “R” statistical software (Vienna, Austria).

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics

Overall, 424 participants had serum and urine samples for measurement of secretory solutes. However, 6 were missing IFTA scores, resulting in a final analytical sample size of 418 (98.6%). A listing and frequency of the diagnosis among 347 participants chosen based biopsy criteria are listed in Supplementary Table 2. The mean (SD) age was 53 (17) years, 51% were women, 64% white and 18% African American (Table 1). The mean (SD) eGFR was 50 (33) ml/min/1.73m2 and median (Q1, Q3) urine albumin was 819 (160, 2584) mg/g of creatinine. The most common indications for kidney biopsy as described previously were proteinuria (60%), abnormal eGFR, (53%) and hematuria (27%).11 Persons with ≥50% IFTA had a higher prevalence of diabetes, lower eGFR and higher grade albuminuria compared with persons who had ≤25% or 26-50% IFTA. Of the 418 with available IFTA scores, 237 (57%) had ≤25%, 71 (17%) had 26-50%, and 110 (26%) had >50% IFTA. Of the 424 study participants, 11 did not have information on ATI. Among the remaining 413, 236 (57%), 113 (28%), 48 (12%) and 12 (3%) had no, mild, moderate and severe ATI, respectively.

Table 1:

Baseline characteristics of patients by categories of IFTA

| Parameter | All N=418 |

IFTA ≤25% N=237 |

IFTA 26-50% N=71 |

IFTA >50% N=110 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 53 (17) | 50 (15) | 58 (17) | 56 (16) |

| Female | 213 (51) | 125 (53) | 34 (48) | 54 (49) |

| Race | ||||

| White | 268 (64) | 146 (62) | 44 (62) | 78 (71) |

| African American | 76 (18) | 43 (18) | 14 (20) | 19 (17) |

| Asian | 39 (9) | 26 (11) | 8 (11) | 5 (5) |

| Other | 35 (8) | 22 (9) | 5 (7) | 8 (7) |

| Diabetes | 93 (22) | 25 (11) | 20 (28) | 48 (44) |

| Hypertension | 220 (53) | 95 (40) | 47 (66) | 78 (71) |

| Urine ACR, mg/g | 819 [160, 2584] | 707 [142, 2239] | 587 [111, 1886] | 1599 [249, 3517] |

| eGFR, ml/min/1.73m2 | 50 (33) | 64 (33) | 36 (21) | 27 (18) |

| eGFR < 60 ml/min/1.73m2 | 284 (68) | 115 (49) | 65 (93) | 104 (95) |

All values represented by n (%), mean (SD) or median [IQR]

CKD- chronic kidney disease, ACR- albumin to creatinine ratio, eGFR- estimated glomerular filtration rate

IFTA and secretory solute clearance

The baseline distribution of the nine log transformed secretory solute clearances is shown in Supplementary Figure 2. The UPR of individual secretory solutes were correlated with each other (range 0.51-0.84) and with eGFR (Supplementary Table 3) Compared to persons with ≤25% IFTA, the unadjusted UPRs were 54 to 70% lower across the various secretory solutes among those with IFTA >50% (Table 2). After adjusting for age, sex and race, this association remained essentially unchanged. Further adjustment for eGFR, urine albumin and urine creatinine attenuated these associations, but 7of 9 solutes remained statistically significantly lower in persons with greater IFTA scores (p for trend <0.05) (Table 2).

Table 2:

Association of IFTA severity with percent change in individual secretory solutes and composite score.

| Biomarker | Unadjusted | Adjusted for age, sex, race | Further adjusted for eGFR, urine creatinine and urine albumin |

p for trend |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤ 25% | 26 - 50% | > 50% | 26 - 50% | > 50% | 26 - 50% | > 50% | ||

| Cinnamoylglycine | ref | −51 (−65, −33) | −70 (−77, −61) | −49 (−63, −29) | −68 (−75, −57) | −3 (−25, 25) | −33 (−47, −15) | 0.001 |

| Hippurrate | ref | −54 (−64, −41) | −59 (−67, −49) | −51 (−62, −36) | −55 (−64, −44) | −30 (−44, −13) | −37 (−49, −23) | <0.001 |

| Indoxyl sulfate | ref | −51 (−63, −36) | −61 (−69, −50) | −49 (−61, −32) | −58 (−67, −47) | −13 (−30, 8) | −25 (−39, −9) | 0.004 |

| Isovalerylglycine | ref | −43 (−56, −26) | −57 (−65, −46) | −40 (−54, −21) | −54 (−63, −42) | 5 (−13, 26) | −15 (−28, 1) | 0.057 |

| Kynurenic acid | ref | −48 (−61, −31) | −67 (−74, −57) | −43 (−57, −24) | −63 (−71, −53) | 1 (−18, 23) | −35 (−46, −21) | <0.001 |

| P-cresol sulfate | ref | −43 (−58, −22) | −65 (−74, −55) | −41 (−57, −18) | −64 (−73, −53) | 2 (−23, 35) | −35 (−49, −15) | 0.001 |

| Pyridoxic acid | ref | −43 (−57, −26) | −64 (−72, −55) | −39 (−54, −20) | −61 (−69, −51) | 8 (−11, 30) | −28 (−39, −14) | <0.001 |

| Tiglyglycine | ref | −45 (−58, −27) | −58 (−67, −47) | −41 (−56, −23) | −55 (−64, −43) | 1 (−17, 22) | −19 (−32, −3) | 0.02 |

| Xansthosine | ref | −45 (−57, −29) | −54 (−63, −43) | −43 (−56, −27) | −51 (−60, −40) | −4 (−19, 13) | −12 (−24, 2) | 0.091 |

| Composite Secretory Index | ref | −48 (−60, −33) | −63 (−70, −54) | −45 (−57, −28) | −60 (−68, −50) | −11 (−29, 13) | −24 (−39, −6) | <0.001 |

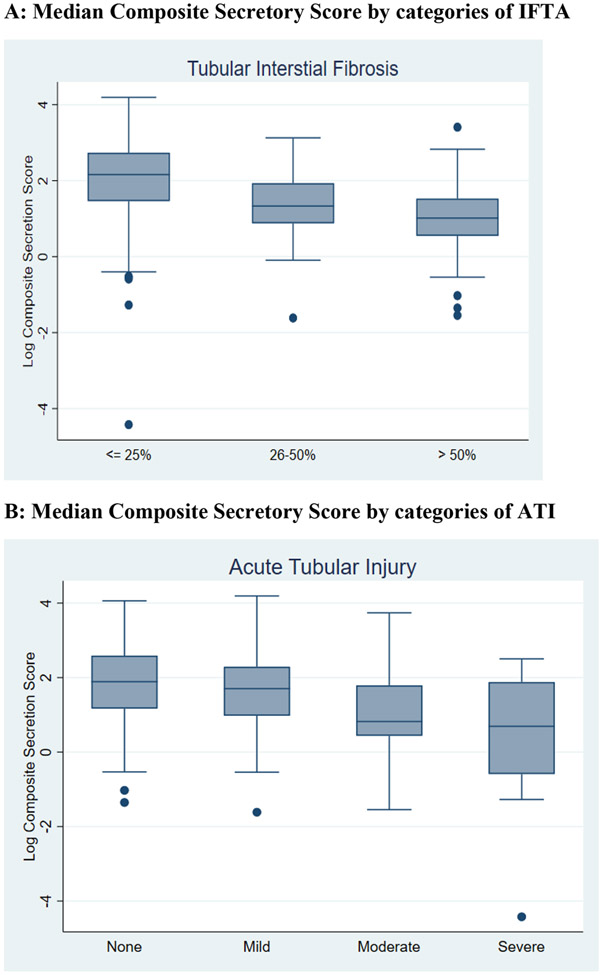

Figure 1 shows box plots for the log transformed median composite secretion index scores by categories of IFTA and ATI. Again, higher IFTA was associated with lower secretion when evaluated using the composite score. Similarly, higher IFTA was associated with lower secretory clearance of all individual solutes (Supplementary Figure 3). The composite secretion score was nearly 48% lower in the group with >50% IFTA compared to those with ≤25% IFTA. After adjustment for demographics, eGFR, urine albumin and urine creatinine, this association remained statistically significant (p for trend 0.002), showing a 24% lower composite secretion index in those with >50% IFTA compared to to those with ≤25% IFTA (Table 2).

Figure 1: Association of IFTA and ATI severity with median composite secretory score.

Figure 1 depicts the association between IFTA (panel A) and ATI (panel B) on the x-axis and log composite secretory score on the y-axis using a box and whisker plot. The line within the box represents the median composite score, with the upper and lower borders of the box indicating the 25th and 75th percentiles. The upper and lower limits of the whiskers indicate the 95% confidence intervals and the dots are outliers.

ATI and secretory solute clearance

Compared to participants with no ATI, severe ATI was associated with 43 to 54% lower UPR values. Adjustment for age, sex and race did not alter these associations. However, further adjustement for eGFR, urine albumin and urine creatinine resulted in attenuated associations which were no longer statistically significant for any of the individual solutes (p for trend > 0.05, Table 3). Greater severity of ATI was associated with a stistically signiciant lower composite secretion score (p<0.028).

Table 3:

Association of severity of acute tubule injury with percent change in individual secretory solutes and composite score.

| Biomarker | Unadjusted | Adjusted for age, sex and race | Further adjusted for eGFR, urine creatinine and urine albumin |

P for trend |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | Mild | Moderate | Severe | Mild | Moderate | Severe | Mild | Moderate | Severe | ||

| Cinnamoylglycine | ref | −51 (−65, −33) |

−70 (−77, −61) |

−51 (−65, −33) |

−49 (−63, −29) |

−68 (−75, −57) |

−49 (−63, −29) |

7% (−13, 31) |

−17% (−38, 11) |

−18% (−53, 42) |

0.328 |

| Hippurrate | ref | −54 (−64, −41) |

−59 (−67, −49) |

−54 (−64, −41) |

−51 (−62, −36) |

−55 (−64, −44) |

−51 (−62, −36) |

19% (−1, 43) |

23% (−5, 60) |

19% (−27, 94) |

0.481 |

| Indoxyl sulfate | ref | −51 (−63, −36) |

−61 (−69, −50) |

−51 (−63, −36) |

−49 (−61, −32) |

−58 (−67, −47) |

−49 (−61, −32) |

18% (−1, 40) |

1% (−22, 29) |

1% (−37, 62) |

0.864 |

| Isovalerylglycine | ref | −43 (−56, −26) |

−57 (−65, −46) |

−43 (−56, −26) |

−40 (−54, −21) |

−54 (−63, −42) |

−40 (−54, −21) |

6% (−8, 23) |

−19% (−35, −1) |

−24% (−48, 13) |

0.082 |

| Kynurenic acid | ref | −48 (−61, −31) |

−67 (−74, −57) |

−48 (−61, −31) |

−43 (−57, −24) |

−63 (−71, −53) |

−43 (−57, −24) |

7% (−9, 27) |

−4% (−24, 23) |

−17% (−47, 30) |

0.350 |

| P-cresol sulfate | ref | −43 (−58, −22) |

−65 (−74, −55) |

−43 (−58, −22) |

−41 (−57, −18) |

−64 (−73, −53) |

−41 (−57, −18) |

10% (−12, 39) |

5% (−25, 46) |

−10% (−51, 67) |

0.701 |

| Pyridoxic acid | ref | −43 (−57, −26) |

−64 (−72, −55) |

−43 (−57, −26) |

−39 (−54, −20) |

−61 (−69, −51) |

−39 (−54, −20) |

2% (−13, 18) |

−9 (−27, 13) |

−13% (−42, 31) |

0.408 |

| Tiglyglycine | ref | −45 (−58, −27) |

−58 (−67, −47) |

−45 (−58, −27) |

−41 (−56, −23) |

−55 (−64, −43) |

−41 (−56, −23) |

11% (−5, 29) |

−11% (−29, 11) |

−29% (−53, 8) |

0.060 |

| Xansthosine | ref | −45 (−57, −29) |

−54 (−63, −43) |

−45 (−57, −29) |

−43 (−56, −27) |

−51 (−60, −40) |

−43 (−56, −27) |

2% (−10, 16) |

2% (−16, 22) |

−24% (−47, 7) |

0.125 |

| Composite secretory index | ref | −48 (−60, −33) |

−63 (−70, −54) |

−48 (−60, −33) |

−45 (−57, −28) |

−60 (−68, −50) |

−45 (−57, −28) |

10% (−3, 26) |

−5% (−21, 14) |

−30% (−51, −1) |

0.028 |

DISCUSSION

In this large cohort of persons undergoing kidney biopsies for clinical indications, we found that greater severity of IFTA was associated with lower secretory solute clearance. These associations remained statistically significant after adjustment for age, sex, eGFR and albuminuria and urine creatinine. Results were similar for the association between ATI and composite secretion score, although the association with individual solutes was not statistically significant. These findings add to our knowledge of the relationship between markers of kidney tubule function and histopathology, and demonstrate that such associations are independent of glomerular markers of kidney function used in contemporary clinical practice.

The current clinical assessment of kidney function relies almost exclusively on markers of glomerular filtration and injury. Despite IFTA being prognostically important and hypothesized to be in a the final common pathway in the progression of CKD to ESKD, it is invisible in clinical practice except in instances when biopsies are performed. Identification of non-invasive, functional markers of tubular secretion reflecting IFTA may therefore provide a novel mechanism to evaluate progression of IFTA and its consequences. Plasma levels of a number of protein bound uremic toxins (PBUT) are elevated as CKD advances due to decrease in tubular secretion.16 Whether plasma to urine ratios of these mark worse overall kidney function, or whether these PBUTs play a causal role in further kidney function decline and the development of IFTA, remains to be determined.

Prior studies evaluating associations between biomarkers and kidney biopsy findings have primarily focused on earlier diagnosis of acute kidney injury (AKI), with some additional work in specific causes of CKD, including kidney transplant recipients or persons with glomerulonephritis.17-19 These studies have found correlations between several biomarkers [neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL), monocyte chemotactic protein 1 (MCP-1), liver-type fatty acid-binding protein (L-FABP) and kidney injury molecule 1 (KIM-1)] and the degree of fibrosis on biopsy, with some being associated with CKD progression.20 These markers focused primarily on tubule injury, inflammation, and fibrosis. Our study is unique in evaluating markers of secretion, thus giving us a potential estimate of tubule function and its relation to IFTA. Although not intended to replace a kidney biopsy, the use of novel biomarkers may aid in the non-invasive assessment of IFTA when a kidney biopsy is not possible.21 Whether secretory function testing will also aid in evaluating response to anti-fibrotic therapies,22 or surveillance of IFTA over time remain areas of future research.

Tubular secretion plays an important role in the excretion of a large number of drugs including penicillin, furosemide, chemotherapeutic drugs like cisplatin, direct oral anti-coagulants such as rivaroxaban, and many others. This occurs through coupled organic anion (OATs) and organic cation transporters (OCTs) in proximal tubule epithelial cells.23-25 Relative diminution of secretory function or competitive inhibition of these transporters by the use of multiple drugs may lead to drug-drug interactions and adverse events.26 Importantly, while excretion of these drugs is through secretion, their dosing is done by estimation of glomerular function or creatinine clearance. While tubular secretion decreases with lower GFR on average, there is considerable variability (sometimes as high as 90%) in tubule secretion at any given level of GFR.27 Recent evidence suggests that tubular secretion of solutes transported primarily through OATs is decreased out of proportion to glomerular filtration in AKI, with the fraction of free secretory solutes increased to levels seen in patients receiving chronic dialysis.28 Given that hospitalized patients may be receiving a number of medications which are dosed based on GFR, but are primarily secreted, loss of secretory function, and novel ways to measure it, may have important clinical implications for drug dosing and avoidance of adverse drug events.

The importance of assessing tubule function in addition to inury was previously demonstrated by studies utilizing furosemide as a stress test (FST). Furosemide is actively transported by the OATs in the proximal tubule into the tubular lumen in order to be excreted and tubular secretion is thus necessary for it to exert its natriuretic effect on the thick ascending limb. In the setting of early AKI, the FST, which measures the 2-hour urine output after a standardized dose of furosemide outperformed biochemical biomarkers for prediction of progressive AKI, need for dialysis, and inpatient mortality.29 Additionally, among patients undergoing kidney biopsy for clinical indiciations, the excretion of furosemide was found to be inversely correlated with severity of interstitial fibrosis.30 Taken together, these findings suggest that the non-invasive assessment of secretory makers may be important in bridging the gap between functional and anatomical changes in the setting of kidney injury. Our findings add to this knowledge by demonstrating that secretory solutes, reflecting proximal tubule function, are lower in the urine relative to plasma in the setting of greater histologic tubule damage, independent of GFR. Further studies are needed to evaluate the role of these biomarkers in the therapeutic monitoring and dosing of drugs like cisplatin, which in addition to being a tubular toxin, is also primarily eliminated by tubular secretion, and has a narrow therapeutic window. Clearly, both under-dosing and over-dosing of such medications carry considerable clinical risks.

In persons with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD), a disease arising from the kidney tubules, secretory solute excretion was lower compared to healthy controls and to those with CKD due to other causes who had a comparable eGFR.14 This discovery suggests that alterations in tubular functions may begin prior the development of overt kidney disease as measured by serum creatinine, and that there may be considerable heterogeneity in tubule function at any range of eGFR. Therefore, it seems plausible that diseases that predominantly affect the kidney tubules may affect tubular secretion earlier and to a greater extent than glomerular filtration. Further, in 3416 participants with CKD from the Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort study, lower kidney clearances of endogenous secretory solutes were associated with CKD progression and all-cause mortality, independent of eGFR and albuminuria.6 Higher secretory clearance of solutes has also been associated with lower uremic and heart failure symptoms,31 highlighting the importance of secretory clearance not just on kidney function but overall health. We evaluated a panel of 9 solutes, many of which were included in the above studies, thereby providing evidence that anatomic alterations may be associated with lower secretory solute clearance within the tubules, and may not captured by eGFR or albuminuria. Further research evaluating change in secretory solutes over time and their relationships with kidney and cardiovascular outcomes are needed.

Our study has a number of limitations. Despite the study cohort being diverse, it only included individuals who underwent biopsies for clinical indications with diseases that are not necessarily reflective of the majority of patients with CKD and patients with AKI. Given the relatively small numbers of biopsies from individual disease categories, we are unable to comment on whether histopathology is associated with secretory solutes across different diseases. Although measured concurrently, we collected urine and serum samples at only one time point at the time of the kidney biopsy and hence are unable to comment on the association between histopathology and change in secretory solutes over time. Additionally, we used spot urine samples to measure secretory clearance unlike prior studies that have used 24-hour urine collections. However, data suggest that spot serum and urine samples can give tubular secretion data similar to that using 24-hour urine samples.32 Further, given that 24-hour urine collections are not always practical, understanding associations between secretory solutes assessed through spot urine samples is important and clinically relevant. Finally, we do not have information on the intake of drugs such as certain antibiotics and anti-retroviral medications which may have an effect of tubular secretion.

Strengths of our study include its relatively large sample size for a study among patients undergoing kidney biopsies, enrollment across three different institutions, histopathology adjudicated by two expert pathologists who were blinded to the clinical diagnosis and laboratory variables, good intra-reader reliability of the histopathologic scores, standardized assessment of glomerular function using cystatin-C and albuminuria, and the use of a targeted LC-MS/MS procedure that was specifically developed for the secretory solutes of interest, which has been used in prior studies.

In conclusion, in a large cohort of patients undergoing kidney biopsy, we demonstrate that clearance of endogenous secretory solutes is inversely associated with the severity of IFTA and ATI, even after adjusting for markers of glomerular function and injury (eGFR and albuminuria). Measurement of endogenous markers of secretion in paired blood and urine holds promise to provide non-invasive insights to the presence and severity of IFTA, and holds promise for clinical use for monitoring treatments of CKD, and for improving drug dosing in the future.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study is supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants K23DK114556 to PSG, R01DK095374 to SW, K24DK103986 to BRK, R01DK098234, K24DK110427 and AHA 14EIA18560026 to JHI. The funders had no role in the stude design, stata collection, analysis, reportring or the decision to submit for publication.

We thank the members of the laboratory of S.S.W. for their invaluable assistance in the Boston Kidney Biopsy Cohort. Part of this work was presented as a poster at the 2020 American Society of Nephrology Kidney Week Reimagined Virtual Poster Session.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES: None

REFERENCES

- 1.Kassirer JP. Clinical evaluation of kidney function--glomerular function. N Engl J Med. 1971;285(7): 385–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Swedko PJ, Clark HD, Paramsothy K, Akbari A. Serum creatinine is an inadequate screening test for renal failure in elderly patients. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(3): 356–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nigam SK. What do drug transporters really do? Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2015;14(1): 29–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sirich TL, Aronov PA, Plummer NS, Hostetter TH, Meyer TW. Numerous protein-bound solutes are cleared by the kidney with high efficiency. Kidney Int. 2013;84(3): 585–590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Duranton F, Cohen G, De Smet R, et al. Normal and pathologic concentrations of uremic toxins. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;23(7): 1258–1270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen Y, Zelnick LR, Wang K, et al. Kidney Clearance of Secretory Solutes Is Associated with Progression of CKD: The CRIC Study. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020;31(4): 817–827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nath KA. Tubulointerstitial changes as a major determinant in the progression of renal damage. Am J Kidney Dis. 1992;20(1): 1–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ong AC, Fine LG. Loss of glomerular function and tubulointerstitial fibrosis: cause or effect? Kidney Int. 1994;45(2): 345–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rule AD, Amer H, Cornell LD, et al. The association between age and nephrosclerosis on renal biopsy among healthy adults. Annals of internal medicine. 2010;152(561-567). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Howie AJ, Ferreira MA, Adu D. Prognostic value of simple measurement of chronic damage in renal biopsy specimens. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2001;16(6): 1163–1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Srivastava A, Palsson R, Kaze AD, et al. The Prognostic Value of Histopathologic Lesions in Native Kidney Biopsy Specimens: Results from the Boston Kidney Biopsy Cohort Study. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018;29(8): 2213–2224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roufosse C, Simmonds N, Clahsen-van Groningen M, et al. A 2018 Reference Guide to the Banff Classification of Renal Allograft Pathology. Transplantation. 2018;102(11): 1795–1814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang K, Zelnick LR, Hoofnagle AN, et al. Differences in proximal tubular solute clearance across common etiologies of chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang K, Zelnick LR, Chen Y, et al. Alterations of Proximal Tubular Secretion in Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Inker LA, Schmid CH, Tighiouart H, et al. Estimating glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine and cystatin C. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(1): 20–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gryp T, De Paepe K, Vanholder R, et al. Gut microbiota generation of protein-bound uremic toxins and related metabolites is not altered at different stages of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2020;97(6): 1230–1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brunner HI, Bennett MR, Mina R, et al. Association of noninvasively measured renal protein biomarkers with histologic features of lupus nephritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64(8): 2687–2697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lertrit A, Worawichawong S, Vanavanan S, et al. Independent associations of urine neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin and serum uric acid with interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy in primary glomerulonephritis. Int J Nephrol Renovasc Dis. 2016;9: 111–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moledina DG, Hall IE, Thiessen-Philbrook H, et al. Performance of Serum Creatinine and Kidney Injury Biomarkers for Diagnosing Histologic Acute Tubular Injury. Am J Kidney Dis. 2017;70(6): 807–816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mansour SG, Puthumana J, Coca SG, Gentry M, Parikh CR. Biomarkers for the detection of renal fibrosis and prediction of renal outcomes: a systematic review. BMC Nephrol. 2017;18(1): 72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moledina DG, Parikh CR. Differentiating Acute Interstitial Nephritis from Acute Tubular Injury: A Challenge for Clinicians. Nephron. 2019;143(3): 211–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sharma K, Ix JH, Mathew AV, et al. Pirfenidone for diabetic nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;22(6): 1144–1151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bendayan R. Renal drug transport: a review. Pharmacotherapy. 1996;16(6): 971–985. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Berkhin EB, Humphreys MH. Regulation of renal tubular secretion of organic compounds. Kidney Int. 2001;59(1): 17–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fanos V, Cataldi L. Renal transport of antibiotics and nephrotoxicity: a review. J Chemother. 2001;13(5): 461–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Masereeuw R, Mutsaers HA, Toyohara T, et al. The kidney and uremic toxin removal: glomerulus or tubule? Semin Nephrol. 2014;34(2): 191–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Suchy-Dicey AM, Laha T, Hoofnagle A, et al. Tubular Secretion in CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;27(7): 2148–2155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.O’Brien FJ, Mair RD, Plummer NS, Meyer TW, Sutherland SM, Sirich TL. Impaired Tubular Secretion of Organic Solutes in Acute Kidney Injury. Kidney360. 2020;1(8): 724–730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koyner JL, Davison DL, Brasha-Mitchell E, et al. Furosemide Stress Test and Biomarkers for the Prediction of AKI Severity. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;26(8): 2023–2031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rivero J, Rodriguez F, Soto V, et al. Furosemide stress test and interstitial fibrosis in kidney biopsies in chronic kidney disease. BMC Nephrol. 2020;21(1): 87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang K, Nguyen M, Chen Y, et al. Association of Tubular Solute Clearance with Symptom Burden in Incident Peritoneal Dialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020;15(4): 530–538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Garimella PS, Li K, Naviaux JC, et al. Utility of Spot Urine Specimens to Assess Tubular Secretion. Am J Kidney Dis. 2017;69(5): 709–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.