Abstract

Our previous International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology report on the nomenclature and classification of adenosine receptors (2011) contained a number of emerging developments with respect to this G protein-coupled receptor subfamily, including protein structure, protein oligomerization, protein diversity, and allosteric modulation by small molecules. Since then, a wealth of new data and results has been added, allowing us to explore novel concepts such as target binding kinetics and biased signaling of adenosine receptors, to examine a multitude of receptor structures and novel ligands, to gauge new pharmacology, and to evaluate clinical trials with adenosine receptor ligands. This review should therefore be considered a further update of our previous reports from 2001 and 2011.

Significance Statement

Adenosine receptors (ARs) are of continuing interest for future treatment of chronic and acute disease conditions, including inflammatory diseases, neurodegenerative afflictions, and cancer. The design of AR agonists (“biased” or not) and antagonists is largely structure based now, thanks to the tremendous progress in AR structural biology. The A2A- and A2BAR appear to modulate the immune response in tumor biology. Many clinical trials for this indication are ongoing, whereas an A2AAR antagonist (istradefylline) has been approved as an anti-Parkinson agent.

I. Introduction

A decade has passed since our last International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology report on the nomenclature and classification of adenosine receptors appeared (Fredholm et al., 2011), after the first one in 2001 (Fredholm et al., 2001). The field has matured to the extent that the recommendations on the nomenclature stand firmly and require neither changes nor refinements. Substantial developments, however, took place (Fredholm et al., 2021), and these alone warrant a further update already. The adenosine A2A receptor (A2AAR) has become a test case for G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) structure elucidation, whereas structures of the adenosine A1 receptor (A1AR) have also become available. The structures have been obtained through either X-ray crystallography or a more recent development, cryo-electron microscopy (EM). These together constitute a huge variety, most of which were determined with different antagonist ligands, a few with agonistic ligands with or without (parts of the) G protein present, and one with a partial agonist. Secondly, the increasing awareness that the study of target binding kinetics reveals more details on the interaction between ligand and receptor has had its effect on the further and more detailed kinetic characterization of adenosine receptor ligands, both agonists and antagonists. Moreover, there is ample attention again for novel ligands interacting with adenosine receptors. Some of these newer and older ligands possess a preference for biased signaling (i.e., the preferred coupling to particular signaling pathways), most notably through different G proteins or β-arrestin. Furthermore, there is an in-depth analysis of the (patho)pharmacological aspects of adenosine receptors and their ligands, both in the periphery and the central nervous system (CNS), leading to an evaluation of the receptors’ relevance in diverse disease states including COVID-19 infection and in aging. The report is concluded with a (nonexhaustive) overview of the clinical trials with adenosine receptor ligands in the last ten years. Disappointing were the outcomes for A1AR partial agonists, with lack of efficacy in heart failure noted in advanced phase 2b clinical studies. On the other hand, an A2AAR antagonist was approved in the United States as a new anti-Parkinsonian drug, and the role of adenosine receptors in immunology has led to a surge of ongoing studies in immuno-oncology, particularly with A2AAR, A2BAR, or dual A2AAR/A2BAR antagonists.

II. Receptor Ligands (for Structures, See Figs. 1, 2, 3, and 5)

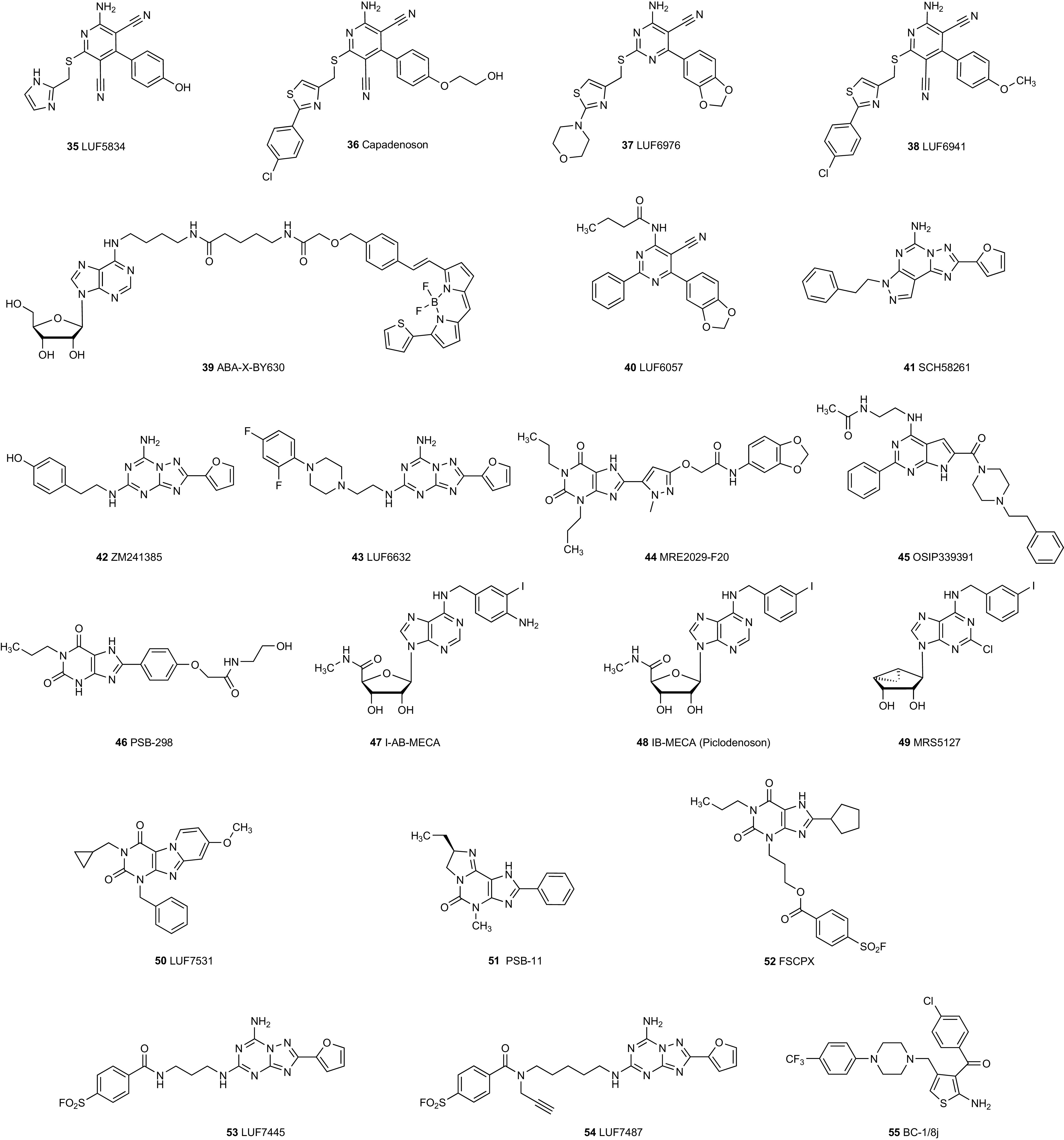

Fig. 1.

Selected ligands for studying ARs.

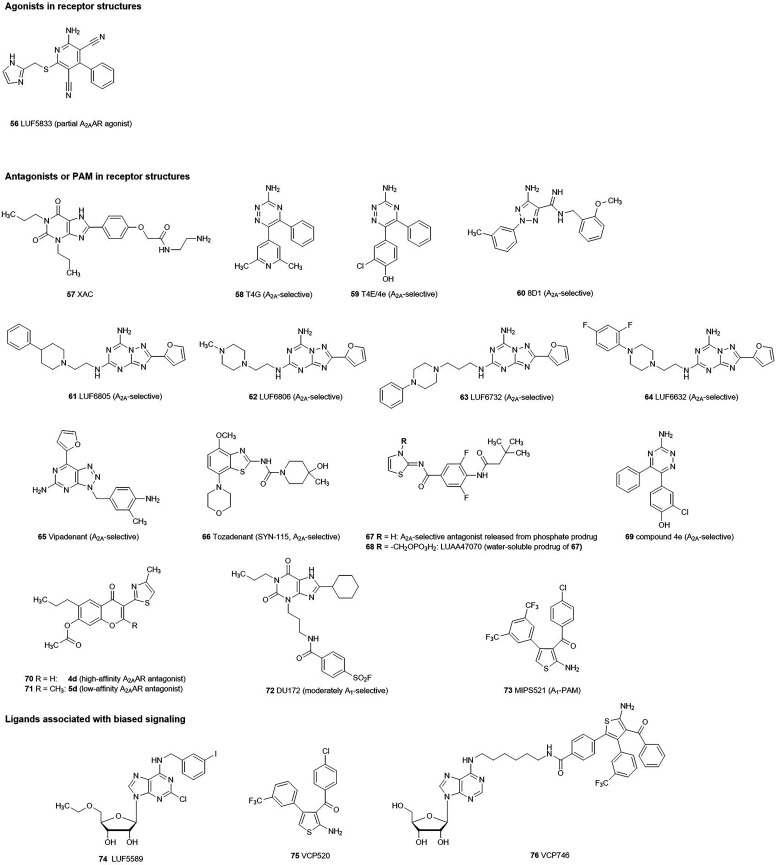

Fig. 2.

Ligands investigated in kinetic studies.

Fig. 3.

Ligands in 3D receptor structures and ligands in biased signaling studies. (Note: In 67 and 68, the X-ray structure of “LUAA47070” was not obtained with the prodrug LUAA47070 but with the A2AAR antagonist that is released from the prodrug upon hydrolysis.)

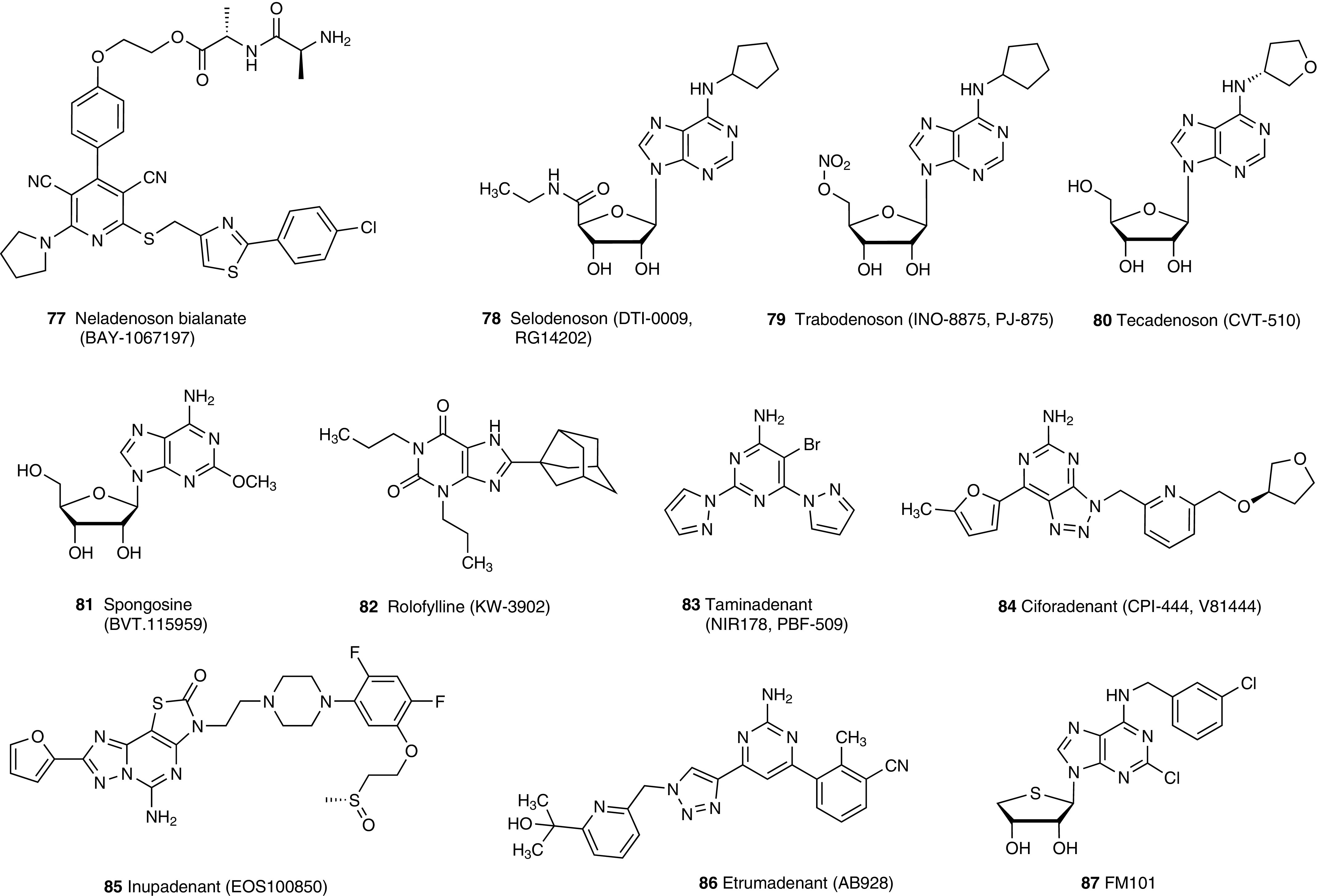

Fig. 5.

Ligands in clinical studies.

Adenosine receptors (ARs) have become established drug targets. Adenosine (1, Fig. 1) itself is used as an injectable diagnostic for cardiac imaging to dilate the coronary arteries via A2AAR activation of patients who cannot exercise on a treadmill (Singh and McKintosh, 2020). The short half-life of under 10 seconds prevents severe side effects of concomitant A1AR activation, such as cardiac block. Moreover, adenosine is applied in supraventricular tachycardia due to its antiarrhythmic effects (Singh and McKintosh, 2020). The A2AAR-selective agonist regadenoson (2, Table 1), used for the same purpose, displays a longer half-life of 2–3 minutes and is of benefit for patients who develop bronchospasms upon treatment with adenosine (Thomas et al., 2017; Patel and Alzahrani, 2020). The natural products caffeine (3) and theophylline (4), xanthine alkaloids present in plants (e.g., Coffea arabica and Camellia sinensis), are moderately potent, nonselective AR antagonists (see Table 2 for receptor affinities) that have been used for thousands of years (Daly, 2007; Müller and Jacobson, 2011b; van Dam et al., 2020). There is epidemiologic evidence linking coffee and tea consumption with different health benefits (Grosso et al., 2016; Poole et al., 2017; van Dam et al., 2020). Caffeine, probably the most widely applied psychoactive drug in the world and broadly used for recreational purposes, is therapeutically applied as a central nervous system (CNS) stimulant, for preterm infants to support breathing function, and in combination therapeutics with analgesics to treat pain and colds (Abo-Salem et al., 2004; Lipton et al., 2017; Alhersh et al., 2020; Evans et al., 2020; van Dam et al., 2020). Several ongoing clinical trials (see also Chapter VII) are evaluating caffeine for various indications including cognition, pain, obesity, cataract prevention, and others. Theophylline, which is less brain-permeant than caffeine, is used for the treatment of asthma, but due to its narrow therapeutic window and the availability of safer and more potent alternative therapeutics, it has lost its importance and nowadays serves as a third-line treatment of add-on therapy only (Barnes, 2003; Tilley, 2011; Journey and Bentley, 2020). Both caffeine and theophylline also interact with other targets (e.g., they inhibit phosphodiesterases), but many of these effects are only observed at high, nonphysiologic concentrations. Most of the desired effects of caffeine and theophylline can in fact be explained by a blockade of ARs. It has to be noted that both xanthine derivatives are about equally potent at all four human AR subtypes, but they are inactive at rodent A3ARs (see Table 2). The A2AAR-selective antagonist istradefylline (5), a xanthine derivative that is structurally derived from caffeine, has been approved for the treatment of Parkinson’s disease (PD) in combination with levodopa, initially only in Japan (in 2013) but now also in the United States (in 2019), whereas the approval process in Europe is in progress (Takahashi et al., 2018; Chen and Cunha, 2020; Jenner et al., 2021). Due to intensive research for several decades aimed at developing AR ligands, a large number of subtype-selective agonists and antagonists has been developed (for reviews, see Müller and Jacobson, 2011a; Jacobson and Müller, 2016; Jacobson et al., 2019; Jacobson et al., 2021). The rather modest success in drug approvals despite a large number of clinical trials discouraged scientists and pharmaceutical companies. However, the recent approval of the A2AAR antagonist istradefylline in the United States and, in particular, the ‘gold rush fever’ in immuno-oncology centered around adenosine as an immunosuppressant (Boison and Yegutkin, 2019; Borah et al., 2019; Allard et al., 2020; Willingham et al., 2020; Thompson and Powell, 2021) have newly energized and fueled the field.

TABLE 1.

Affinities of selected adenosine receptor agonists

| Ki or EC50 (nM)a | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | A2A | A2Bb | A3 | ||

| Nonselective Agonists | |||||

| 1 | Adenosinec | ca. 100 (h) 73 (r) |

310 (h) 150 (r) |

15,000 (h) 5,100 (r) |

290 (h) 6,500 (r) |

| 6 | NECA | 14 (h) 5.1 (r) 2.49 (m) |

20 (h) 9.7 (r) 43.4 (m) |

1,890 (h) 1,110 (r) 656 (m) |

25 (h) 113 (r) 13.2 (m) |

| A1AR-Selective Agonists | |||||

| 7 | CCPA | 0.83 (h) 1.3 (r) 0.269 (m) |

2270 (h) 950 (r) 988 (m) |

18,800 (h) 6,160 (r) 25.300 (m) |

38 (h) 237 (r) 15.6 (m) |

| 8 | 2′-MeCCPA | 3.3 (h) | 9,580 (h) | 37.600 (h) | 1.150 (h) |

| 9 | (S)-ENBA | n.d. (h) 0.34 (r) |

n.d. (h) 477 (r) |

n.d. | 282 (h) 915 (r) |

| A2AAR-Selective Agonists | |||||

| 10 | CGS21680 | 289 (h) 1800 (r) 961 (m) |

27 (h) 19 (r) 13.7 (m) |

>10,000 (h) >10,000 (r) >10,000 (m) |

67 (h) 584 (r) 93.0 (m) |

| 11 | UK-432,097 | n.d. | 4 | n.d. | n.d. |

| 12 | PSB-0777 | 541 (h) ≥10,000 (r) |

360 (h) 44.4 (r) |

>10,000 (h) | >10,000 (h) |

| 2 | Regadenoson | >10,000 (h) | 290 (h) | >10,000 (h) | >10,000 (h) |

| A2BAR-Selective (Partial) Agonist | |||||

| 13 | BAY 60-6583 | 387 (h) 514 (r) 351 (m) |

>10,000 (h) >10,000 (r) >10,000 (m) |

3–10 (h, EC50) 114 (h) 100 (r) 136 (m) |

223 (h) 2,750 (r) 3,920 (m) |

| A3AR-Selective Agonists | |||||

| 14 | Cl-IB-MECA (CF102, Namodenoson) |

220 (h) 280 (r) 35 (m) |

5360 (h) 470 (r) 290 (m) |

>10,000 (h) 1,210 (r) 44,300 (m) |

1.4 (h) 0.33 (r) 0.18 (m) |

| 15 | HEMADO | 330 (h) | 1200 (h) | >30,000 (h) | 1.10 (h) |

| 16 | MRS5698 | >10,000 (h) >10,000 (m) |

>10,000 (h) >10,000 (m) |

assumed to be inactive | 3.49 (h) 3.08 (m) |

h, human; Ki, inhibition constant; m, mouse; n.d., no data; r, rat.

adata (if available from Ki values from radioligand binding assays) are taken from the literature cited in the text.

bmost A2BAR data are from functional studies (cAMP accumulation).

cadenosine data are from functional studies (cAMP accumulation).

TABLE 2.

Affinities of selected, useful adenosine receptor antagonists

| Ki (nM)a | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | A2A | A2B | A3 | ||

| Nonselective Antagonists | |||||

| 3 | Caffeine | 44,900 (h) 41,000 (r) 50,700 (m) |

23,400 (h) 43,000 (r) 11,100 (m) |

33,800 (h) 30,000 (r) 23,000 (m) |

13,300 (h) >100,000 (r) >100,000 (m) |

| 4 | Theophylline | 6,770 (h) 14,000 (r) |

6,700 (h) 22,000 (r) |

9,070 (h) 15,100 (r) 5,630 (m) |

22,300 (h) >100,000 (r) |

| A1AR-Selective Antagonists | |||||

| 17 | DPCPX (CPX) | 3.0 (h) 0.50 (r) 0.413 (m) |

129 (h) 157 (r) 263 (m) |

51 (h) 186 (r) 86.2 (m) |

243 (h) >10,000 (r) >10,000 (m) |

| 18 | PSB-36 | 0.7 (h) 0.124 (r) 1.58 (m) |

980 (h) 552 (r) 697 (m) |

187 (h) 350 (r) 704 (m) |

2,300 (h) 6,500 (r) >10,000 (m) |

| 19 | SLV320 | 1.00 (h) 2.51 (r) |

398 (h) | 3,981 (h) 501 (r) |

200 (h) |

| A2AAR-Selective Antagonists | |||||

| 5 | Istradefylline (KW6002) | 841 (h) 230 (r) 438 (m) |

12 (h) 4.46 (r) 6.83 (m) |

>10,000 (h) 5,940 (r) 3,590 (m) |

4,470 (h) >10,000 (r) >10,000 (m) |

| 20 | MSX-3 / MSX-2 (Data are for MSX-2) |

2,500 (h) 900 (r) |

5.38 (h) 8.04 (r) |

>10,000 (h) | >10,000 (h) |

| 21 | Preladenant (SCH-420814) | >1,000 (h) >1,000 (h) 462 (m) |

0.9 (h) 0.986 (r) 0.241 (m) |

>1,000 (h) >1,000 (m) >1,000 (r) |

>1,000 (h) >1,000 (m) >1,000 (r) |

| 22 | Imaradenant (AZD4635) | 160 (h) | 1.7 (h) | 64 (h) | >10,000 (h) |

| A2BAR-Selective Antagonists | |||||

| 23 | MRS1754 | 403 (h) 16.8 (r) 1.45 (m) |

503 (h) 612 (r) >10,000 (m) |

1.97 (h) 12.8 (r) 3.12 (m) |

570 (h) >1,000 (m) >1,000 (r) |

| 24 | PSB-603 | >10,000 (h) >10,000 (r) 42.4 (m) |

>10,000 (h) >10,000 (r) >10,000 (m) |

0.553 (h) 0.355 (r) 0.265 (m) |

>10,000 (h) >10,000 (r) >10,000 (m) |

| 25 | PSB-0788 | 2,240 (h) 386 (r) 118 (m) |

333 (h) 1,730 (r) 235 (m) |

0.393 (h) 2.12 (r) 1.90 (m) |

>1,000 (h) >10,000 (r) >10,000 (m) |

| 26 | PSB-1115 | >10,000 (h) 2,200 (r) 591 (m) |

3790 (h) 24,000 (r) >10,000 (m) |

53.4 (h) 3,140 (r) 1,940 (m) |

>10,000 (h) >10,000 (r) >10,000 (m) |

| 27 | GS 6201 (CVT-6883) | 1,940 (h) | 3,280 (h) | 22 (h) | 1,070 (h) |

| 28 | BAY-545 | >1,000; 1,300 (h) n.d. (r) >6,700 (m) |

>1,000; 820 (h) 750 (r) 470 (m) |

59–97 (h) 280 (r) 400 (m) |

>10,000 (h) n.d. (r) >6,700 (m) |

| 29 | ISAM-140 | >1,000 (h) | >1,000 (h) | 3.49 (h) | >1,000 (h) |

| A3AR-Selective Antagonists | |||||

| 30 | MRS1523 | >10,000 (h) 15,600 (r) >10,000 (m) |

3660 (h) 2050 (r) >10,000 (m) |

>10,000 (h) >10,000 (r) >10,000 (m) |

18.9 (h) 113 (r) 731 (m) |

| 31 | MRE3008-F20 | 1200 (h) | 141 (h) | 2100 (h) | 0.82 (h) |

| 32 | PSB-10 | 1,700 (h) 805 (r) |

2,700 (h) 6,040 (r) |

30,000 (h) | 0.441 (h) 17,000 (r) |

| 33 | VUF5574 | ≥10,000 (r) | ≥10,000 (r) | n.d. | 4.03 (h) |

| 34 | MRS7591b | >10,000 (h) 590 (m) |

>10,000 (h) n.d. |

n.d. n.d. |

10.9 (h) 17.8 (m) |

h, human; Ki, inhibition constant; m, mouse; n.d., no data; r, rat.

adata are taken from the literature cited in the text.

bpartial agonistic activity if receptor is highly expressed.

This chapter will provide guidance in selecting tool compounds for research on ARs. Rather than presenting a comprehensive collection of AR ligands for which the reader be referred to previous review articles selected (Fredholm et al., 2011; Müller and Jacobson, 2011a; Jacobson and Müller, 2016; Jacobson et al., 2021), preferably well characterized ligands will be discussed that are recommended as tool compounds. Whenever possible, not only data for human ARs but also those for rat and mouse orthologs will be listed since considerable species differences have been observed in some cases, which are most pronounced for the A3AR subtype (Alnouri et al., 2015; Du et al., 2018). For most receptor subtypes, at least two different agonists and antagonists will be included. In addition, useful physicochemical and pharmacokinetic data have been collected if available.

A. Adenosine Receptor Agonists

The physiologic agonist adenosine (1) is more potent at A1-, A2A- and A3ARs than at A2BARs in most settings (see Table 1). However, reliable radioligand binding data cannot be obtained since adenosine is present in tissues, cells, and even cell membrane preparations and is constantly produced (e.g., from released ATP by ectonucleotidases) (Zimmermann, 2021). Therefore, it usually has to be removed, which is achieved by preincubation or addition of adenosine deaminase (ADA). Thus, ADA and its reaction product inosine are typically present during incubation with radioligand and test compound. ADA itself can allosterically modulate ARs (Gracia et al., 2013). In contrast to radioligand binding data, potencies determined in functional, G protein-dependent assays such as cAMP accumulation studies depend on receptor expression levels and receptor reserve, and concentration-effect curves are shifted to the left with increased receptor expression levels (Fujioka and Omori, 2012). Therefore, EC50 values of agonists obtained in different cellular systems are not comparable. As mentioned before, adenosine has a short half-life being metabolized by ADA or adenosine kinase (AdoK) after removal by cellular uptake through nucleoside transporters, which can additionally influence results. For that reason, metabolically (more) stable adenosine analogs have been developed. Nevertheless, it becomes increasingly clear that synthetic ligands do not necessarily induce the same effects at a certain receptor as the cognate agonist (e.g., regarding the activation of intracellular signaling pathways) (see also Chapter V). Therefore, if possible, adenosine should always be included in pharmacological studies besides more stable and selective synthetic agonists. The closely related adenosine analog 5′-N-ethylcarboxamidoadenosine (NECA, 6) cannot be metabolized by ADA or AdoK. Similar to adenosine, NECA is significantly more potent at A1-, A2A-, and A3ARs than at A2BARs. There is a lack of potent, selective, and fully efficacious A2BAR agonists; NECA is still one of the more potent full agonists at the A2BAR and represents a useful tool to study A2BARs in combination with selective antagonists for the other AR subtypes (Verzijl and IJzerman, 2011; Müller et al., 2018; Franco et al., 2021b).

Potent, truly selective A1AR agonists have been developed by N6-substitution of adenosine (see Table 1 and Fig. 2). 2-chloro-N6-cyclopentyladenosine (CCPA, 7) is suitable for rat and mouse studies, where it shows >100-fold selectivity versus the other AR subtypes, whereas it is less selective in humans versus the A3AR subtype (46-fold). For studies at the human A1AR, its 2′-methyl-substituted derivative 2′-MeCCPA (8) can be used, which is more selective (>300-fold) in humans (Franchetti et al., 2009). Data at rat and mouse ARs are not available for this compound. Another potent and selective A1AR agonist is (S)-ENBA (9), possessing a bulky bicyclo[2.2.1]hept-2-yl moiety at the N6-position that confers A1AR selectivity.

A2AAR-selective agonists have been obtained by introducing large, bulky substituents into the 2-position of adenosine or NECA, in some cases in combination with an additional bulky N6-substituent. Most of the developed compounds are only moderately selective in humans versus the A1- or A3AR subtypes. CGS21680 (10) is a potent and A2AAR-selective agonist in rat and mouse but shows only moderate selectivity in humans (vs. A1- and A3ARs; see Table 1). However, in some studies on mouse brain, 10 has been observed to additionally bind to A1ARs (Lopes et al., 2004). The reason for this observation is still unclear; one explanation could be the formation of heteromeric receptor complexes showing a different pharmacology. The 2,N6-disubstituted NECA derivative 11 (UK-432,097; Table 1) is potent at the human A2AAR and was reported to also be selective. Compound 11 is a relatively large and lipophilic molecule that is less water-soluble than other adenosine derivatives and analogs. It showed a long receptor residence time of 250 minutes at 5°C (see Table 3), which probably contributed to its successful cocrystallization with the human A2AAR (Xu et al., 2011). PSB-0777 (12), bearing a phenylsulfonate group, is well soluble in water and has been useful for injection or for local application in the gut since it is not perorally absorbed due to its negative charge. It shows high selectivity in rats but not in humans and is thus useful for studies in rodents. Regadenoson (2) is only moderately potent but selective in humans and is clinically used as a diagnostic (see above). Importantly, in tissues with higher A1AR versus A2AAR density such as the brain, (moderately selective) A2AAR agonists often bind to and activate A1AR rather than A2AAR (Zhang et al., 1994; Cunha et al., 1996; Halldner et al., 2004; Pliássova et al., 2020). Thus, potent and really selective A2AAR agonists to target central A2AARs are still required.

TABLE 3.

Association and dissociation rate constants of selected AR ligands

| Compound | Target (h, human; r, rat) |

Temp (°C) | kon (M−1·min−1) | koff (min−1) | RT (min) | Kinetic KD (nM)a | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7 | CCPA | hA1AR | 25 | 9.6 × 106 | 1.2 | 0.9 | 131 | (Guo et al., 2014b) |

| 6 | NECA | hA1AR | 25 | 9.0 × 105 | 0.47 | 2.1 | 522 | (Guo et al., 2014b) |

| 35 | LUF5834 | hA1AR | 25 | 2.0 × 108 | 0.92 | 1.1 | 4.6 | (Guo et al., 2014b) |

| 36 | Capadenoson | hA1AR | 25 | 2.4 × 107 | 0.036 | 28 | 1.5 | (Louvel et al., 2015) |

| 37 | LUF6976 | hA1AR | 25 | 3.9 × 108 | 0.87 | 1.1 | 2.2 | (Louvel et al., 2014) |

| 38 | LUF6941 | hA1AR | 25 | 2.6 × 106 | 0.0076 | 132 | 2.9 | (Louvel et al., 2015) |

| 39 | ABA-X-BY630 | hA1ARb | 37 | 2.6 × 107 | 2.0 | 0.5 | 77 | (May et al., 2010) |

| 17 | DPCPX | hA1AR | 25 | 1.4 × 108 | 0.21 | 4.8 | 1.5 | (Guo et al., 2013) |

| 17 | DPCPX | rA1R | 25 | 9.6 × 107 | 0.045 | 22.2 | 0.50 | (Guo et al., 2017) |

| 10 | CGS21680 | hA2AAR | 25 | 5.0 × 104 | 0.02 | 50.0 | 380 | (Guo et al., 2017) |

| 10 | CGS21680 | rA2AAR | 23 | 2.1 × 107 | 0.033 | 30.3 | 1.6 | (Guo et al., 2017) |

| 40 | LUF6057 | hA1AR | 25 | 4.8 × 108 | 3.0 | 0.3 | 6.3 | (Guo et al., 2013) |

| 6 | NECA | hA2AAR | 4 | 1.9 × 106 | 0.053 | 19 | 28 | (Guo et al., 2015) |

| 11 | UK432,097 | hA2AAR | 5 | 5.0 × 105 | 0.004 | 250 | 8.0 | (Guo et al., 2012) |

| 41 | SCH58261 | hA2AAR | 25 | 6.4 × 108 | 1.5 | 0.67 | 2.3 | (Dionisotti et al., 1997) |

| 42 | ZM241385 | hA2AAR | 4 | 1.3 × 108 | 0.014 | 71 | 0.11 | (Guo et al., 2014c) |

| 43 | LUF6632 | hA2AAR | 4 | 3.4 × 107 | 0.0031 | 323 | 0.091 | (Guo et al., 2014c) |

| 20a | MSX-2 | rA2AAR (brain striatal membranes) |

23 | 14.5 × 107 | 0.2839 | 3.52 | 1.95 | (Müller et al., 2000) |

| 6 | NECA | hA2BAR | 4 | n.d. | 2.201 | 0.45 | n.d. | (Hinz et al., 2018) |

| 23 | MRS1754 | hA2BAR | 25 | 2.2 × 107 | 0.027 | 37 | 1.2 | (Ji et al., 2001) |

| 44 | MRE2029-F20 | hA2BAR | 4 | 1.7 × 107 | 0.031 | 32 | 1.8 | (Baraldi et al., 2004) |

| 45 | OSIP339391 | hA2BAR | 22 | 9.5 × 107 | 0.039 | 26 | 0.41 | (Stewart et al., 2004) |

| 24 | PSB-603 | hA2BAR | 21 | 11.4 × 107 | 0.02279 | 44 | 0.652 | (Borrmann et al., 2009) |

| 46 | PSB-298 | hA2BAR | 25 | 3.76 × 107 | 0.9533 | 1.05 | 25 | (Bertarelli et al., 2006) |

| 47 | I-AB-MECA | hA3AR | 37 | 6.1 × 107 | 0.042 | 24 | 0.69 | (Gao et al., 2001) |

| 48 | IB-MECA | hA3AR | 10 | 3.5 × 107 | 0.011 | 95 | 0.30 | (Xia et al., 2018) |

| 14 | 2-Cl-IB-MECA | hA3AR | 10 | 2.4 × 107 | 0.0043 | 231 | 0.18 | (Xia et al., 2018) |

| 49 | MRS5127 | hA3AR | 25 | 2.4 × 108 | 0.51 | 2.0 | 2.1 | (Auchampach et al., 2010) |

| 16 | MRS5698 | hA3AR | 10 | 7.8 × 106 | 5.1 × 10−4 | 1961 | 0.068 | (Xia et al., 2018) |

| 31 | MRE3008-F20 | hA3AR | 4 | 7.6 × 107 | 0.042 | 24 | 0.55 | (Varani et al., 2000) |

| 50 | LUF7531 (cmpd 2) | hA3AR | 10 | 1.7 × 108 | 0.0036 | 315 | 0.021 | (Xia et al., 2017) |

| 51 | PSB-11 | hA3AR | 25 | 2.35 × 108 | 0.2082 | 4.80 | 0.46 | (Müller et al., 2002) |

n.d., no data.

a(kinetic) KD = koff/kon.

bwhole cells.

So far, potent and selective full agonists for the A2BAR are not available. BAY 60-6583 (13), a non-nucleoside aminopyridine derivative, behaves as a partial A2BAR agonist (Hinz et al., 2014) but was shown to act as an antagonist at other AR subtypes (Alnouri et al., 2015). In the presence of high adenosine concentrations, it can even inhibit A2BAR activation (Hinz et al., 2014; Alnouri et al., 2015). Data obtained with 13 are therefore difficult to interpret. BAY 60-6583 may induce a different A2BAR conformation than adenosine or NECA; for example, it has been shown that BAY 60-6583 does not induce calcium mobilization via A2BAR-mediated Gq protein activation in human embryonic kidney (HEK) cells with low endogenous A2BAR expression in contrast to adenosine or NECA (Hinz et al., 2014; Gao et al., 2018b). Thus, a potent, selective, efficacious, and unbiased A2BAR agonist is urgently needed. Instead of the partial agonist BAY 60-6583, the full, nonselective agonist NECA (6) may be used in the presence of antagonists for the other AR subtypes.

For the A3AR, potent and selective agonists are available. Cl-IB-MECA (14, CF102, namodenoson), a 2-chloro-N6-iodobenzyl-substituted methylcarboxamidoadenosine (MECA) derivative, is being evaluated in clinical trials for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). For pharmacological studies, especially in mice, the doses of 14 have to be carefully chosen in order not to activate the A1AR as well (see Table 1). HEMADO (15) is similarly potent and selective in humans. A potent and at the same time selective A3AR agonist, in human as well as in mouse, is MRS5698 (16).

B. Adenosine Receptor Antagonists

Many potent A1AR-selective antagonists have been developed based on caffeine and theophylline as lead structures, such as DPCPX (17, CPX) and PSB-36 (18) (Müller and Jacobson, 2011b). Whereas DPCPX shows only moderate selectivity in humans, PSB-36 is highly selective in all three species: human, rat, and mouse (Alnouri et al., 2015). SLV320 (19) is an A1AR antagonist with a 7-deaza-adenine core structure bearing a cyclohexyl moiety at the exocyclic amino function (Kalk et al., 2007). The compound is potent and selective in humans and displays similar potency in rat, but complete data in rat and mouse are not available.

The xanthine derivative istradefylline (5) was the first A2AAR antagonist to be approved as a drug (Shimada et al., 1992; Takahashi et al., 2018). Its potency and selectivity for the A2AAR is similar in human, rat, and mouse. Although it is highly selective versus the A2B- and A3AR subtypes, selectivity versus the A1AR is somewhat lower (50- to 70-fold) (see Table 2). Like many other A2AAR antagonists, it is moderately water-soluble. In addition, the double bond of its styryl residue can undergo light-induced E/Z-isomerization in dilute solution and is prone to light-induced dimerization in the solid state; therefore, it needs to be protected from light (Nonaka et al.,1993; Hockemeyer et al., 2004). The same is true for MSX-3 (20), a phosphate prodrug of MSX-2, which is, however, well soluble in water (Sauer et al., 2000; Faivre et al., 2018). The A2AAR selectivity of MSX-2 is higher than that of istradefylline (see Table 2). The nonxanthine A2AAR antagonist preladenant (21, SCH-420814) is one of the most potent and selective A2AAR antagonists. It has been evaluated in clinical trials for PD and was found to be well tolerated but did not show significant beneficial effects (Stocchi et al., 2017; LeWitt et al., 2020). As observed with istradefylline, the study design is most critical for these types of clinical PD studies and may have contributed to the negative outcome in the case of preladenant (Hauser et al., 2015). AZD4635 (22, imaradenant) is a potent A2AAR antagonist with moderate selectivity versus the A2B- and A3ARs subtypes. Despite its relatively low molecular weight (315.7 g/mol) the compound is not readily soluble in water.

In recent years many A2BAR-selective antagonists have been developed (Müller et al., 2018). The xanthine derivative MRS1754 (23) is a potent and selective A2BAR antagonist in humans but not in rats and mice, where it additionally blocks the A1AR (Kim et al., 2000; Alnouri et al., 2015). One of the most potent and selective A2BAR antagonists in all three species is the 8-sulfophenylxanthine derivative PSB-603 (24) (Borrmann et al., 2009; Alnouri et al., 2015). The compound is metabolically highly stable in human, rat, and mouse. Its main drawback, however, is its low water solubility. The related A2BAR antagonist PSB-0788 (25) (Borrmann et al., 2009; Alnouri et al., 2015) is better soluble, especially under weakly acidic conditions since it bears a basic nitrogen atom that can be protonated. However, it is less metabolically stable and therefore less suitable for in vivo studies. PSB-0788 is moderately selective for A2B- versus A1ARs in mouse (only about 60-fold) but highly A2BAR-selective in human and rat. PSB-1115 (26) was developed as an A2BAR antagonist with high water solubility due to its sulfonate group (Hayallah et al., 2002). Although the compound is potent and selective in human, it is not selective in rat and mouse and additionally blocks rodent A1ARs (see Table 2) (Alnouri et al., 2015). The xanthine derivative GS6201 (27, CVT6883) which shows good potency and selectivity for human A2BARs (Elzein et al., 2008), was evaluated in a phase 1 clinical trial for pulmonary diseases, but further development has not been reported (Kalla and Zablocki, 2009). The compound displayed a half-life of 4 hours and a peroral bioavailability of 35% in rat (Elzein et al., 2008); potency and selectivity in rodents have not been reported. BAY-545 (28) is a recently published A2BAR antagonist with a new scaffold identified by high-throughput screening, although its thienopyrimidinedione structure resembles the xanthine scaffold (Härter et al., 2019). The compound shows moderate affinity compared with other developed A2BAR antagonists and is more potent at human than at rat and mouse A2BARs. It is more than 10-fold selective in human but is nonselective in mouse and rat (Härter et al., 2019). Another novel scaffold, a pyrimido[1,2-a]benzimidazole, is represented by ISAM-140 (29), an A2BAR antagonist that shows high potency and selectivity in human. Unfortunately, data from other species are not available (El Maatougui et al., 2016). Subsequently, related dihydropyrimidine derivatives have been developed that are similarly potent and selective (Majellaro et al., 2021).

The A3AR typically shows large species differences for antagonists (Müller, 2003; Jacobson and Müller, 2016). Most published antagonists that are very potent at human A3ARs are inactive at the rodent (rat and mouse) orthologs. One of the best A3AR antagonists for rodent studies is MRS1523 (30). The compound is only moderately potent but very selective in human (>100-fold) and at least somewhat selective in rat (18-fold vs. A2A, >100-fold vs. the other AR subtypes) and mouse (at least 14-fold vs. the other subtypes) (van Rhee et al., 1996; Li et al., 1998; Müller and Jacobson, 2011a; Alnouri et al., 2015; Jacobson and Müller, 2016). Further potent A3AR antagonists, including MRE3008-F20 (31) (Baraldi et al., 2012; Borea et al., 2015), PSB-10 (32) (Ozola et al., 2003; Alnouri et al., 2015), and VUF5574 (33) (van Muijlwijk-Koezen et al., 2000) are highly potent and selective in human but virtually inactive at rodent A3ARs (see Table 2). As species differences are more pronounced for A3AR antagonists than for agonists, most of which are derivatives or analogs of adenosine, compounds with a truncated, furanyl, or carbocyclic moiety in place of the ribose ring of adenosine were investigated and optimized (Jeong et al., 2007; Lee et al., 2010; Nayak et al., 2014; An et al., 2020). Such adenosine analogs show reduced intrinsic activity or even block the receptors. Appropriate substitution on the adenine ring led to MRS7591 (34) showing high affinity for both human and mouse A3ARs and good selectivity in human (>1000-fold) (Tosh et al., 2020). Selectivity in mouse has only been assessed against the A1AR (33-fold). It has to be kept in mind that compound 50 behaved as a (weakly efficacious) partial agonist (Tosh et al., 2020).

C. Allosteric Modulators of Adenosine Receptors

The development of allosteric modulators for GPCRs in general is an emerging field of research (Müller et al., 2012; Gao and Jacobson, 2013; Wootten et al., 2013). Positive allosteric modulators (PAMs) increasing the potency or efficacy of agonists, and negative allosteric modulators (NAMs) acting as noncompetitive antagonists, have been reported for various AR subtypes, especially for the A1AR. The AR-PAMs that have been developed so far display only moderate potency or selectivity, and their usefulness is still unclear (Fredholm et al., 2011; Göblyös and IJzerman, 2011; Jacobson et al., 2011; Müller et al., 2012; Nguyen et al., 2016; Barresi et al., 2021). Interestingly, in a recent cryo-EM structure of the A1AR, a PAM (MIPS521) was found to be localized in an extrahelical domain (Draper-Joyce et al., 2021). MIPS521’s analgesic properties were evaluated in the same paper, reminiscent of earlier attempts to profile another PAM as a potential painkiller (Kiesman et al., 2009).

D. Inosine and Guanosine

Adenosine is metabolized to inosine by adenosine deaminases (ADA-1 and -2). Inosine has been reported by several groups to interact with ARs (e.g., with A2AAR and A3AR) but only at very high, nonphysiologic concentrations (>100 μM) (Welihinda et al., 2016). On the other hand, inosine (Lovászi et al., 2021) as well as the nucleoside guanosine (Di Liberto et al., 2016) clearly show pharmacological effects, at least some of which seemed to be exerted by interaction with GPCRs. However, it is unlikely that these effects are mediated by direct activation of ARs. As an example, the hypothermic effects of inosine disappear completely in mice lacking either all four ARs or the A3AR (Xiao et al., 2019). Alternatively, they may be due to inhibition of adenosine uptake through the equilibrative nucleoside transporter 1 (ENT1). Indirect effects are also conceivable (e.g., through allosteric modulation). Further research on inosine and guanosine as extracellular signaling molecules in their own right is warranted.

III. Receptor Binding Kinetics

It has been recognized in recent years that the study of target binding kinetics is crucial to reduce attrition rates in drug discovery (Copeland, 2016). Over the decades medicinal chemists have successfully synthesized lead compounds displaying high, often (sub)nanomolar affinity for a given target, including ARs. However, kinetic aspects of the ligand-receptor interaction have been studied in lesser detail. Although these can be very informative, the extra effort to obtain values for association (kon) and dissociation (koff) rate constants was and is substantial. This is because kinetic assays tend to be laborious although more efficient approaches (Guo et al., 2013) and methods are being developed, including scintillation proximity assays (Xia et al., 2016) and bioluminescence resonance energy transfer (BRET)-based ligand binding studies (Bouzo-Lorenzo et al., 2019; White et al., 2019). On the other hand, systematically evaluating the binding kinetics of a series of lead compounds that are otherwise chemically or biologically similar provides additional parameters for triage and advancement of molecules in the drug discovery process (Guo et al., 2016a; 2017). For instance, assessment of the lifetime of a ligand-receptor complex, coined residence time (RT = 1/koff) (Copeland et al., 2006), has been shown predictive for drug efficacy and selectivity, including on ARs (Swinney, 2006a,b; Guo et al., 2014a; Zhang, 2015; Tonge, 2018). Drugs with long target RT are likely to produce a longer duration of action by more gradually reducing the decline of target occupancy than those with short RT (Dahl and Akerud, 2013; de Witte et al., 2016). Furthermore, a direct correlation between receptor RT and functional efficacy has been observed in some cases (Sykes et al., 2009; Guo et al., 2012). A thorough review of the kinetic characteristics of AR ligands, both orthosteric ligands and allosteric modulators, has recently appeared (Guo et al., 2017); hence, we will only provide a concise summary and update here.

A. Orthosteric Ligands and Adenosine Receptor Binding Kinetics

In Table 3, kinetic data [association and dissociation rate constants, kinetic equilibrium dissociation constants (KD), and residence times] for (orthosteric) agonists and antagonists of the human adenosine receptors (hARs) are summarized. Their chemical structures, if not listed in Fig. 1, are assembled in Fig. 2. Most experiments were radioligand binding assays performed on membrane preparations, whereas lower than physiologic temperatures were employed in most cases due to practical limitations of the (radio)labeled probe used, such as a (too) fast dissociation at higher temperatures. There have been a few attempts to use surface plasmon resonance instrumentation for kinetic assays on hA2AR, but these have not become routinely available since solubilized and purified receptor material is needed (Bocquet et al., 2015; Errey et al., 2015).

It is often thought that association rate constants for bimolecular encounters readily reach high values that are diffusion-limited only (1010 ∼1011 M−1·min−1) (Smoluchowski, 1918; Alberty and Hammes, 1958). However, this is only true for reactant molecules that have isotropic reactivity, whereas the interaction between ligand and receptor, including ARs, is of a more constrained nature (e.g., due to the stereospecificity of recognition). This is obvious from Table 3, in which association rate constants vary from 5.0 × 105 (11, UK432,097) to 6.4 × 108 (41, SCH58261) M−1·min−1, an over 1000-fold difference but still far from diffusion control. The latter compound is another selective A2AAR antagonist that has been extensively characterized in rodents. Association rate constants appear correlated with the onset of clinical action, in vivo target occupancy, and target rebinding (Vauquelin, 2018). However, this has not been demonstrated for AR ligands yet.

The dissociation rate constants or, for convenience, residence times also vary significantly, up to >5000-fold. There are ligands with ultra-short residence times [e.g., only seconds for antagonists LUF6057 (40, A1AR) and SCH58261 (41, A2AAR)], whereas agonists UK432,097 (11, A2AAR), Cl-IB-MECA (14, A3AR), and MRS5698 (16, A3AR) as well as antagonists LUF6632 (43, A2AAR) and LUF7531 (50, A3AR) engage with the receptor for hours. In a recent study, Hothersall and coworkers (2017) identified UK432,097 analogs that displayed even longer target occupancy on hA2AAR. Differences in RT for a number of A2AAR antagonists have been linked to their differential modulation of the salt bridge strength between amino acids Glu169 and His264 in the egress pathway at the extracellular side of the receptor (Guo et al., 2016b; Segala et al., 2016).

B. Orthosteric Ligands Binding Covalently to Adenosine Receptors

Ligands that react covalently with ARs can be regarded as having infinite RT as long as the chemical bond between ligand and receptor “survives.” Over the decades, such ligands have been developed as probes mostly (e.g., to identify the molecular weight of AR molecules, block the physiologic function of ARs or, more recently, help in AR structure elucidation). It remains to be investigated whether such ligands might have relevant therapeutic value.

Thus, both chemoreactive and photoaffinity agonists and antagonists were synthesized in early A1AR studies and evaluated for their binding irreversibility using various assays and degrees of sophistication (Choca et al., 1985; Klotz et al., 1985; Earl et al., 1988; Patel et al., 1988; Stiles and Jacobson, 1988; Jacobson et al., 1989a; Boring et al., 1991; Scammells et al., 1994; Srinivas et al., 1996; Beauglehole et al., 2000; van Muijlwijk-Koezen et al., 2001; Jorg et al., 2016). Of these, FSCPX (52) has been most widely used, and a close derivative of it, DU172 (72) (Beauglehole et al., 2000), appeared crucial for the crystallographic structure elucidation of hA1AR (Glukhova et al., 2017) (Chapter IV). DU172, through its fluorosulfonyl moiety, forms a covalent bond with amino acid Y2717.36 at the extracellular end of the seventh transmembrane domain (TM7) of the receptor.

Likewise, similar efforts have been performed on A2AAR for agonists (Jacobson et al., 1989b; Barrington et al., 1990; Jacobson et al., 1992; Niiya et al., 1993; Luthin et al., 1995; Moss et al., 2014) and antagonists (Ji et al., 1993; Muranaka et al., 2017; Yang et al., 2017). One of the covalent antagonists, LUF7445 (53), was equipped with a click handle to act as a chemical probe (54, LUF7487) for A2AAR (Yang et al., 2018). This chemical biology approach allowed, among others, receptor visualization in hA2AAR-expressing cell membranes.

The A2BAR has not been subjected to covalent labeling yet, whereas the A3AR has been the target for such studies, sampling both irreversibly binding agonist (Ji et al., 1994) and antagonist ligands (Li et al., 1999; Baraldi et al., 2001; Yang et al., 2019).

C. Allosteric Ligands and Adenosine Receptor Binding Kinetics

Ligands binding to an allosteric site distinct from the AR orthosteric binding pocket (see also Chapter II) may influence the binding kinetics of orthosteric ligands. Indeed, on many occasions it has been shown that positive allosteric modulators (PAMs) for the A1AR retard the dissociation rate of orthosteric A1AR agonists, as summarized in a number of reviews (Göblyös and IJzerman, 2011; Kimatrai-Salvador et al., 2013; Guo et al., 2017). For instance, one of the more potent A1AR PAMs, BC-1/compound 8j (55) (Romagnoli et al., 2008), increased the residence time of CCPA up to 200-fold from 0.9 minutes (Table 2) to 172 minutes (Guo et al., 2014b). Unfortunately, the often modest, micromolar potency of PAMs and other allosteric ligands for ARs has so far precluded the assessment of the binding kinetics of these ligands per se.

D. Adenosine Receptor Target Binding Kinetics – Conclusions

Kinetic parameters are an additional factor in assessing the quality and nature of new chemical entities. Nearly all compounds in Table 3 have high affinity, but their kinetics can be very different. A striking example is the pair of LUF6976 (37, KD = 2.2 nM for A1AR, RT = 1.1 minutes) and LUF6941 (38, KD = 2.9 nM for A1AR, RT = 132 minutes), showing identical affinity but a more than 100-fold difference in residence time. Thus, many compounds are considered equivalent on the basis of affinity alone, whereas a further differentiation or even triage may be possible depending on their kinetic characteristics. For instance, A2AAR antagonists are currently in clinical trials as potential adjuvants in cancer immunotherapy (see Chapter VII) to block adenosine’s unwanted anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive effects (Hatfield and Sitkovsky, 2016). The local adenosine concentration in the tumor may be so high that short-RT antagonists cannot productively compete, whereas a long-RT antagonist may lead to sufficient target engagement even in the presence of elevated adenosine concentrations. Likewise, A2AAR antagonists have been developed for the treatment of PD in combination with levodopa/dopaminergic agonists, although clinical success has been limited so far (Morelli et al., 2009; Hickey and Stacy, 2012). In that setting, a compound with a long receptor RT could have some advantages, as it might yield a reduction in the “wear-off” effect (e.g., of levodopa in between doses) (Hickey and Stacy, 2012). Thus, information obtained from a kinetic perspective may provide additional rationales for the design of new AR ligands. At the same time, one needs to realize that pharmacokinetic aspects are also governing in vivo effects and that an integration of aspects of target binding kinetics and of pharmacokinetics is required (Daryaee and Tonge, 2019).

IV. Receptor Structures

Over the last decade, the elucidation of receptor architecture has been one of the hallmarks in GPCR research (Venkatakrishnan et al., 2013). The A2AAR was one of the first structures solved, through X-ray crystallography (Jaakola et al., 2008), and since then many adenosine receptor structures have been reported (see Table 4 and references therein). Typical characteristics of GPCRs such as their thermolability and fragility have dictated the use of highly engineered proteins and protein constructs for structure elucidation as well as of highly sophisticated technologies (Grisshammer, 2017). At least three approaches have been used widely. First, thermostabilization of GPCRs (Magnani et al., 2016), including the A2AAR, has yielded material sufficient for crystallization by combining amino acid mutations to raise the protein melting temperature. Secondly, fusion of the A2AAR with proteins that crystallize “easily,” such as T4 lysozyme (T4L) (Jaakola et al., 2008) or apocytochrome b562RIL (bRIL) (Liu et al., 2012), has been instrumental to generate crystalline material. Thirdly, complexation of the A2AAR with antibodies raised against epitopes of the receptor provided sufficient stability to render X-ray crystallography feasible (Hino et al., 2012). In recent years, cryogenic electron microscopy (EM), particularly single-particle cryo-EM (Cheng, 2018; Ceska et al., 2019), has been employed to study membrane protein structures as well, including agonist-bound structures of the A1AR (Draper-Joyce et al., 2018; 2021) and A2AAR (Garcia-Nafria et al., 2018) in complex with G protein variants.

TABLE 4.

Reported structures of adenosine receptor subtypes

| PDB | Engineering | Ligand | Resolution (Å) | Technique | Remarks | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A2AAR Antagonist Structures | ||||||

| 3PWH | TS | ZM241385 (42) | 3.3 | X-ray | (Dore et al., 2011) | |

| 3REY | TS | XAC (57) | 3.3 | X-ray | (Dore et al., 2011) | |

| 3RFM | TS | Caffeine (3) | 3.6 | X-ray | (Dore et al., 2011) | |

| 3UZA | TS | T4G (58) | 3.3 | X-ray | T4G: 6-(2,6-dimethylpyridin-4-yl)-5-phenyl-1,2,4-triazin-3-amine | (Congreve et al., 2012) |

| 3UZC | TS | T4E (59) | 3.3 | X-ray | T4E: 4-(3-amino-5-phenyl-1,2,4-triazin-6-yl)-2-chlorophenol | (Congreve et al., 2012) |

| 3EML | FP (T4L) | ZM241385 | 2.6 | X-ray | (Jaakola et al., 2008) | |

| 4EIY | FP (bRIL) | ZM241385 | 1.8 | X-ray | (Liu et al., 2012) | |

| 5UIG | FP (bRIL) | 8D1 (60) | 3.5 | X-ray | 8D1: 5-amino-N-[(2-methoxyphenyl)methyl]-2-(3-methylphenyl)-2H-1,2,3-triazole-4-carboximidamide | (Sun et al., 2017) |

| 5K2A | FP (bRIL) | ZM241385 | 2.5 | X-ray/SFX/XFEL, sulfur SAD phasing | SFX: serial femtosecond crystallography; XFEL: X-ray free-electron laser; SAD: single-wavelength anomalous diffraction | (Batyuk et al., 2016) |

| 5K2B | FP (bRIL) | ZM241385 | 2.5 | X-ray/SFX/XFEL, MR phasing | MR: molecular replacement | (Batyuk et al., 2016) |

| 5K2C | FP (bRIL) | ZM241385 | 1.9 | X-ray/SFX/XFEL, sulfur SAD phasing and phase extension | (Batyuk et al., 2016) | |

| 5K2D | FP (bRIL) | ZM241385 | 1.9 | X-ray/SFX/XFEL, MR phasing | (Batyuk et al., 2016) | |

| 5VRA | FP (bRIL) | ZM241385 | 2.4 | X-ray in situ | in situ: film sandwich plates at room temperature | (Broecker et al., 2018) |

| 5JTB | FP (bRIL) | ZM241385 | 2.8 | X-ray/I-SAD | I-SAD: iodide-single-wavelength anomalous diffraction | (Melnikov et al., 2017) |

| 5UVI | FP (bRIL) | ZM241385 | 3.2 | X-ray millisec | millisec: serial millisecond crystallography using synchrotron radiation | (Martin-Garcia et al., 2017) |

| 6AQF | FP (bRIL) | ZM241385 | 2.5 | X-ray | (Eddy et al., 2018b) | |

| 7RM5 | FP (bRIL) | ZM241385 | 2.8 | Microcrystal electron diffraction | (Martynowycz et al., 2021) | |

| 5NM2 | TS-FP (bRIL) | ZM241385 | 2.0 | X-ray millisec (cryo) | (Weinert et al., 2017) | |

| 5NLX | TS-FP (bRIL) | ZM241385 | 2.1 | X-ray millisec (room temp) | (Weinert et al., 2017) | |

| 5NM4 | TS-FP (bRIL) | ZM241385 | 1.7 | X-ray femtosec (room temp) | Serial femtosecond crystallography using XFEL | (Weinert et al., 2017) |

| 5MZJ | TS-FP (bRIL) | Theophylline (4) | 2.0 | X-ray | (Cheng et al., 2017) | |

| 5MZP | TS-FP (bRIL) | Caffeine (3) | 2.1 | X-ray | (Cheng et al., 2017) | |

| 5N2R | TS-FP (bRIL) | PSB-36 (18) | 2.8 | X-ray | (Cheng et al., 2017) | |

| 5IU4 | TS-FP (bRIL) | ZM241385 | 1.7 | X-ray | (Segala et al., 2016) | |

| 5IU7 | TS-FP (bRIL) | 12c (61, LUF6805) | 1.9 | X-ray | 12c: 2-(furan-2-yl)-N5-(2-(4-phenylpiperidin-1-yl)ethyl)[1,2,4]triazolo[1,5-a][1,3,5]triazine-5,7-diamine | (Segala et al., 2016) |

| 5IU8 | TS-FP (bRIL) | 12f (62, LUF6806) | 2.0 | X-ray | 12f: 2-(furan-2-yl)-N5-(2-(4-methylpiperazin-1-yl)ethyl)[1,2,4]triazolo[1,5-a][1,3,5]triazine-5,7-diamine | (Segala et al., 2016) |

| 5IUA | TS-FP (bRIL) | 12b (63, LUF6732) | 2.2 | X-ray | 12b: 2-(furan-2-yl)-N5-(3-(4-phenylpiperazin-1-yl)propyl)[1,2,4]triazolo[1,5-a][1,3,5]triazine-5,7-diamine | (Segala et al., 2016) |

| 5IUB | TS-FP (bRIL) | 12x (64, LUF6632) | 2.1 | X-ray | 12x: N5-(2-(4-(2,4-difluorophenyl)piperazin-1-yl)ethyl)-2-(furan2-yl)-[1,2,4]triazolo[1,5-a][1,3,5]triazine-5,7-diamine | (Segala et al., 2016) |

| 5OLG | TS-FP (bRIL) | ZM241385 | 1.9 | X-ray, soaking | soaking of ligand to displace theophylline in the crystals | (Rucktooa et al., 2018) |

| 5OLH | TS-FP (bRIL) | Vipadenant (65) | 2.6 | X-ray, soaking for 24 hr | (Rucktooa et al., 2018) | |

| 5OLO | TS-FP (bRIL) | Tozadenant (66) | 3.1 | X-ray, soaking for 24 hr | (Rucktooa et al., 2018) | |

| 5OLV | TS-FP (bRIL) | LUAA47070 (analog) (67/68) | 2.0 | X-ray, soaking for 24 hr | (Rucktooa et al., 2018) | |

| 5OLZ | TS-FP (bRIL) | 4e (69) | 1.9 | X-ray | 4e: 4-(3-amino-5-phenyl-1,2,4-triazin-6-yl)-2-chlorophenol | (Rucktooa et al., 2018) |

| 5OM1 | TS-FP (bRIL) | 4e | 2.1 | X-ray, soaking for 1 hr | (Rucktooa et al., 2018) | |

| 5OM4 | TS-FP (bRIL) | 4e | 2.0 | X-ray, soaking for 24 hr | (Rucktooa et al., 2018) | |

| 6LPJ/K/L | FP (bRIL) | ZM241385 | 1.8–2.0 | Serial femtosecond crystallography using XFEL | EROCOC17 + 4 as crystallization matrix | (Ihara et al., 2020) |

| 6ZDR | TS-FP (bRIL) | Chromone 4d (70) | 1.9 | X-ray | (Jespers et al., 2020) | |

| 6ZDV | TS-FP (bRIL) | Chromone 5d (71) | 2.1 | X-ray | (Jespers et al., 2020) | |

| 6GT3 | TS-FP (bRIL) | AZD4635 (22) | 2.0 | X-ray | (Borodovsky et al., 2020) | |

| 6S0Q | TS-FP (bRIL) | ZM241385 | 2.7 | Native SAD | SAD: single-wavelength anomalous diffraction | (Nass et al., 2020) |

| 3VG9 | antibody-stab | ZM241385 | 2.7 | X-ray | (Hino et al., 2012) | |

| 3VGA | antibody-stab | ZM241385 | 3.1 | X-ray | (Hino et al., 2012) | |

| A2AAR Agonist Structures | ||||||

| 2YDO | TS | Adenosine (1) | 3.0 | X-ray | (Lebon et al., 2011) | |

| 2YDV | TS | NECA (6) | 2.6 | X-ray | (Lebon et al., 2011) | |

| 4UG2 | TS | CGS21680 (10) | 2.6 | X-ray | (Lebon et al., 2015) | |

| 4UHR | TS | CGS21680 | 2.6 | X-ray | (Lebon et al., 2015) | |

| 3QAK | FP (T4L) | UK432097 (11) | 2.7 | X-ray | WT receptor | (Xu et al., 2011) |

| 5WF5 | FP (bRIL) | UK432097 | 2.6 | X-ray | D52N mutant | (White et al., 2018) |

| 5WF6 | FP (bRIL) | UK432097 | 2.9 | X-ray | S91A mutant | (White et al., 2018) |

| 5G53 | truncated and tagged WT | NECA (6) | 3.4 | X-ray | with engineered G protein (mini-Gs) | (Carpenter et al., 2016) |

| 6GDG | FP (thioredoxin) | NECA | 4.1 | cryo-EM | with engineered G protein (mini-Gs-β1γ2); also includes nanobody Nb35 | (Garcia-Nafria et al., 2018) |

| 7ARO | TS-FP (bRIL) | LUF5833 (56) | 3.1 | X-ray | LUF5833 is a partial agonist | (Amelia et al., 2021) |

| A1AR Antagonist Structures | ||||||

| 5N2S | TS | PSB-36 (18) | 3.3 | X-ray | (Cheng et al., 2017) | |

| 5UEN | FP (bRIL) | DU172 (72) | 3.2 | X-ray | (Glukhova et al., 2017) | |

| A1AR Agonist Structures | ||||||

| 6D9H | tagged WT receptor | Adenosine (1) | 3.6 | cryo-EM | with engineered Gi2 protein | (Draper-Joyce et al., 2018) |

| 7LD3/4 | tagged WT receptor | Adenosine (1) +/− MIPS521 (73) | 3.3–3.4 | cryo-EM | with engineered Gi2 protein | (Draper-Joyce et al., 2021) |

A. Resolution

The overall resolution of the AR crystal structures varies between 1.7 Å and 3.6 Å (see Table 4). A high resolution (lower Å values) provides more structural details, particularly the presence or absence of explicit water molecules. It has been shown that a minimum resolution of ∼3.0 Å is required to see any water molecules in a protein crystal structure, whereas on average one water molecule per amino acid residue can be detected at 2.0 Å (Carugo and Bordo, 1999). This means that most adenosine receptor crystal structures lack information on the role that water molecules play in ligand binding. However, >60 explicit water molecules are observed in the 1.8 Å resolution A2AAR-ZM241385 (42) complex (4EIY, Table 4), showing a wide distribution throughout the protein, including the ligand binding site, in which water molecules hydrogen-bond to both ligand and amino acid residues (Liu et al., 2012). In fact, the receptor structure is suggestive of a water-filled pore or channel. The channel has two bottlenecks around Trp2466.48 and Tyr2887.53, slightly less in size than the diameter of one water molecule. These amino acids are part of two general motifs related to GPCR activation, the “rotamer/toggle switch” and the NPxxY sequence, respectively. Interestingly, recent developments show that molecular dynamics and other calculations can make up for the absence of water molecules in a low-resolution protein structure (Matter and Gussregen, 2018). Due to its high resolution, the same 4EIY structure was the first to show the presence of an allosterically binding sodium ion, interacting in a cavity containing a strongly conserved aspartic acid (Asp522.50). As this domain is generic among most class A GPCRs, it is expected that other GPCRs bind sodium ions at this site as well (e.g., as was demonstrated for the human δ-opioid receptor) (Fenalti et al., 2014).

B. Ligand Binding Site

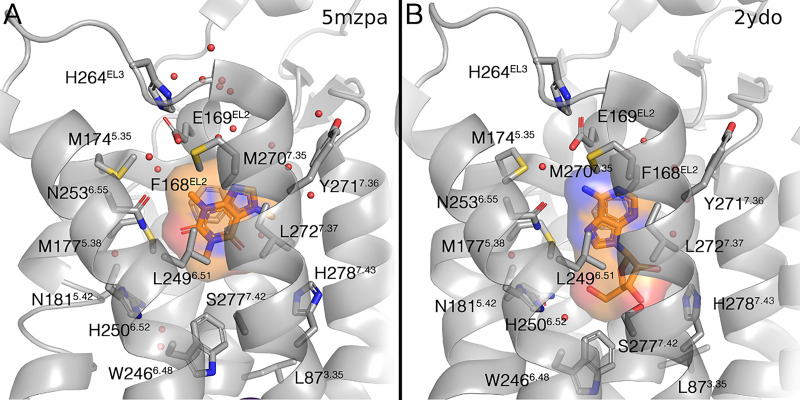

The ARs’ orthosteric binding site (i.e., the binding site for endogenous agonist adenosine) accommodates a range of ligands with diverse scaffolds and different sizes (see Table 4; Fig. 4). In fact, the A2AAR is the GPCR with the most structures available in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) (Vass et al., 2018), allowing an unprecedented view on the conformational flexibility of the ligand binding site.

Fig. 4.

Overview of the A2AAR binding site, showing the first frame of two movies: (A) antagonist (Supplemental Video 1) and (B) agonist (Supplemental Video 2). All residues within 2Å of a given ligand in an A2AAR structure were considered as the binding pocket, and this selection was maintained in all frames. The residues are labeled according to the wild-type (WT) sequence, and modifications made to the receptor (e.g., the thermostabilizing mutant S2777.42A) are not taken into account; note that no labeling is used in the supplemental movie files. The Ballesteros-Weinstein numbering is given in superscript. Ligands are shown in orange, with a volumetric occupancy surface-colored on the atom type. Water atoms in the binding site are shown as red dots, and the sodium ion (when present) as a purple sphere. If alternate coordinates were given in the extracted PDB file, the ‘A’ coordinates were maintained, except in the case of caffeine, in which case we generated two separate frames (referred to as 5mzpa and 5mzpb) to show the two binding modes in the crystal structure. Only distinctly different binding modes of ZM241385 (as present in 4EIY and 3PWH) are included in the movie.

In total >15 different antagonists have been cocrystallized with hA2AAR so far (Table 4), compared with just one structure with ZM241385 (PDB: 3EML) in the previous update. The receptor binding site appears flexible as these antagonists take slightly different positions therein (see Supplemental Video 1). The four agonists cocrystallized with hA2AAR until now (Table 4) all have a ribose moiety, pointing deeper into the ligand binding pocket and displacing explicit water molecules present in the antagonist-occupied receptor structures (see Supplemental Video 2). The agonist-bound structures crystallized in the absence of G protein are now regarded as representing intermediate states in the process of receptor activation. The presence of an engineered G protein makes the cytoplasmic end of TM6 move away considerably from the receptor core by ∼14 Å compared with the other agonist-bound structures, with little impact on the extracellular side of the receptor and the ligand binding pocket (Carpenter et al., 2016; Garcia-Nafria et al., 2018). This is most pronounced for the NECA (6)-bound cryo-EM structure with engineered G protein and nanobody Nb35 (Garcia-Nafria et al., 2018). The thermodynamic contributions of a single, conserved water molecule bridging the 2′-hydroxyl and 3-aza groups of adenosine were analyzed, which led to the design of a modified, potent agonist containing a mimic of this water (Matricon et al., 2020). Recently, the first X-ray structure of A2AAR with a nonriboside, 3,5-dicyanopyridine partial agonist (56, LUF5833) was reported (Amelia et al., 2021).

The structure elucidation of the hA1AR is another achievement. Two crystal structures of antagonist-bound receptor are available (Cheng et al., 2017; Glukhova et al., 2017), whereas one cryo-EM structure with an agonist (adenosine, 1) bound has been reported, the latter in the presence of an engineered Gi protein (Draper-Joyce et al., 2018). The latter structure was later complemented with a positive allosteric modulator, MIPS521 (73), as well, the binding site of which appeared to be extrahelically located involving TM domains 1, 6, and 7 (Draper-Joyce et al., 2021). In the antagonist structures, it was noted that there are differences in the extracellular loop regions, particularly the second one, relative to the hA2AAR structure. The ligand binding cavity is relatively wide, again in comparison with hA2AAR. Differences in pocket shape between the two receptors may determine selectivity more than the (very similar) amino acids lining the pockets. There is a tightening of the orthosteric binding site induced by an ∼4 Å inward movement of the extracellular ends of TMs 1 and 2 in the adenosine-bound, active structure compared with the antagonist-bound, inactive hA1AR. At the intracellular surface, the engineered G protein present causes a 10.5 Å outward movement of TM6 in the hA1AR, quite comparable to the similar large shift in active hA2AAR.

All agonists and antagonists are anchored by two amino acids in particular in both receptors [i.e., Asn2536.55 (numbering as in hA2AAR) and Phe168 in EL2]. A further summary of relevant amino acids for ligand binding, also focusing on selectivity issues between ARs, has been provided recently (Jespers et al., 2018).

C. NMR Studies

Although X-ray crystallography and cryo-EM methods provide important information on AR architecture, NMR spectroscopy has the potential to reveal additional structural dynamics data. Two main approaches have been used so far: 1) indole 15N-1H chemical shifts are monitored after introducing extrinsic (15N-labeled) tryptophan residues at relevant sites, or 2) by incorporating 19F reporter tags onto cysteine residues in the protein, 19F-1H resonances are assessed. In both cases, distinct conformational A2AAR states were observed upon interaction with G protein (Prosser et al., 2017; Huang et al., 2021), cations (Ye et al., 2018), full and partial agonists (Eddy et al., 2018a; 2021; Sušac et al., 2018), and allosteric modulators/sites (Eddy et al., 2018b). The next challenge will be to begin and address other aspects of AR dynamics and functioning, such as the impact of the lipid membrane environment (Guixà-González et al., 2017).

V. Cellular Pharmacology – Biased Signaling of Adenosine Receptors

Each GPCR potentially couples to multiple G proteins, as was demonstrated for the endogenous A2AAR (Cunha et al., 1999) and A2BAR (Gao et al., 2018b), and to non-G protein dependent pathways, such as β-arrestins (Michel and Charlton, 2018; Vecchio et al., 2018). In some cases, the net effect of each of these signaling cascades induced by the same endogenously expressed AR in different cells may be opposite, such as with the A2BAR (Gao et al., 2018b). In theory, the ability of a GPCR agonist to consistently distinguish among multiple intracellular signaling pathways provides advantages when used in a therapeutic mode if the preferred pathway is associated with the beneficial action at the receptor. Such an agonist is termed biased, which implies a nonequivalence in the potency or efficacy across the signaling pathways. In principle, side effects that are associated with the nonpreferred pathways would be avoided. Signaling bias might also affect the kinetics of GPCR trafficking, as internalized receptors can also signal, or gene transcription.

Biased signaling depends on multiple active GPCR conformations, each of which would couple to its own spectrum of second messenger pathways. Thus, biased agonists, also at ARs, achieve signaling selectivity by interacting with or stabilizing a subset of the possible active receptor conformations, and this subset has characteristic pharmacology distinct from other conformations of the same receptor (Verzijl and IJzerman, 2011). Biased agonism has been reported at adenosine A1-, A2B-, and A3ARs for both nucleoside agonists and two classes of non-nucleoside AR agonists, the 3,5-dicyanopyridines and 5-cyanopyrimidines (Langemeijer et al., 2013). Tissue-dependent A2AAR signaling was observed in neurons of different brain areas through engineered optogenetic signaling (Li et al., 2015). Inhibitors of GPCR signaling could be biased as well, for example, as shown for the A1AR using a suramin derivative (Kudlacek et al., 2002). Allosteric GPCR modulators, such as A1AR enhancers (PAMs) in the 2-amino-3-benzoylthiophene family or A3AR PAMs in the imidazoquinolinamine family, can show biased effects on agonist-induced signaling (Gao et al., 2011).

A1AR: In a broad screen of AR agonists, nucleoside agonist LUF5589 (74, 2-chloro-5′-O-ethyl-N6-(3-iodobenzyl)adenosine) tended toward a signaling bias for the Gi protein-dependent pathway in comparison with the β-arrestin pathway (Langemeijer et al., 2013). Biased agonism at the A1AR was also explored by Baltos and coworkers (2016). PAM VCP520 (75) potentiated A1AR agonist-induced Ca2+ mobilization more effectively than extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 activation (Valant et al., 2010). Identification of biased agonism (i.e., cardioprotective efficacy without hemodynamic side effect) associated with an A1AR PAM conjugated to an agonist, VCP746 (76), suggested that this bitopic ligand might be bridging orthosteric and allosteric sites on the receptor (Valant et al., 2014). A recent structure determined for A1AR (Glukhova et al., 2017) shows that it possesses at least one allosteric site, potentially the site that has been exploited to promote biased agonism (Valant et al., 2014).

A2AAR: The biased signaling of A2AAR is rather peculiar among ARs since it seems to be a property of the environment of the A2AAR, probably related to the numerous G protein-interacting proteins that are associated with A2AAR. In fact, at least six G protein-interacting proteins (actinin, calmodulin, NECAB2, translin-associated protein X, ARNO/cytohesin-2, and ubiquitin-specific protease-4) have been reported to interact with the long A2AAR C terminus (Keuerleber et al., 2011). The exploitation of constructs with an altered C-terminal tail revealed a biased A2AAR-mediated signaling with PSB-0777 (12) and LUF5834 (35) (Navarro et al., 2020). Also, inosine has been proposed to activate A2AAR in a biased manner in CHO-K1 cells heterologously expressing hA2AAR (Welihinda et al., 2016). Still, A2AAR agonists with biased properties have been scarcely explored, although they would be of clear interest to potentially optimize immunomodulatory functions without cytotoxic or vascular effects.

A2BAR: Nucleoside agonists distinguish among different G protein-dependent signaling pathways of the A2BAR (Gao et al., 2014). Extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 activation may result from β-arrestin mobilization or from Gq- or Gs-protein coupling. In fact, entirely different signaling pathways are activated depending on whether the receptor is endogenously occurring or introduced by transfection (Gao et al., 2018b). A2BAR activation in muscle and brown fat had a beneficial effect on energy expenditure and increased muscle mass, suggesting the application of selective A2BAR agonists that principally activate cAMP for treating obesity (Gnad et al., 2020). A2BAR activation also reduces cardiac fibrosis via the PKCδ to p38-MAPK pathway and protects the ischemic heart by stabilizing HIF-1α (Campos-Martins et al., 2021). Thus, translational opportunities are conceivable if selective and biased A2BAR agonists could be developed for these signaling pathways.

A3AR: Storme and coworkers (2018), using an engineered arrestin-reporter cell line, compared the Gi-dependent and β-arrestin2-dependent signaling of 19 nucleoside agonists at the A3AR to show a tendency toward weak bias for the G protein pathway in a few analogs. Similar conclusions were reported in an earlier study comparing known A3AR agonists (Gao and Jacobson, 2008), which noted differences in the kinetics of receptor activation.

VI. Pharmacology – Novel Developments

This chapter addresses select aspects of AR pharmacology. In this update, we focus on the therapeutic targeting of ARs and elaborate on their relevance in disease states. In the previous update, dimerization/oligomerization of ARs was particularly emphasized (Fredholm et al., 2011). This potentially critical variable to selectively modulate AR activity has been detailed in a number of recent reviews (Vecchio et al., 2018; Ferré and Ciruela, 2019; Franco et al., 2021a).

A. Therapeutic Targeting of Adenosine Receptors

Adenosine receptors have been targeted in the treatment of a number of (peripheral and CNS) diseases including PD, cardiac arrhythmias, asthma, and infant apnea (Kreutzer and Bassler, 2014). Adenosine receptors are also targeted for diagnostic studies of coronary circulation in individuals unable to manage a treadmill. Over the years, targeting adenosine receptors has been tested in animal models of diabetes, inflammatory diseases, wound healing, sickle cell disease, congestive heart failure, Alzheimer’s disease, depression, and grand mal epilepsies, as well as in human trials. Other potential disease targets for agents targeted to adenosine receptors have recently been identified. Below we identify some of the most promising applications for adenosine receptor agents described over the past 10 years (Borea et al., 2018). It should be kept in mind, however, that a knowledge gap exists between advanced animal studies, which are many, and the limited number of reports on native human cells and tissues. From a translational perspective toward successful clinical studies, it seems essential to close this gap.

B. Therapeutic Targeting of Peripheral Adenosine Receptors

1. Adenosine A1 Receptors and Congestive Heart Failure

Adenosine, generated within the kidney and acting at A1AR, induces vasoconstriction of afferent arterioles reducing renal blood flow and glomerular filtration rate (GFR), further stimulating renin release. Moreover, activation of A1AR increases proximal tubular reabsorption of sodium ions (Vallon et al., 2006). In congestive heart failure A1AR activation was postulated to play a role in the reduced GFR and sodium retention that characterize congestive heart failure, and it was suggested that blockade of A1AR could alleviate the symptoms of congestive heart failure by increasing GFR and promoting sodium elimination (Vallon et al., 2008). When tested in the clinic, however, short courses of rolofylline, a selective A1AR antagonist, provided no benefit in the treatment of congestive heart failure, and a number of patients suffered seizures, a known potential adverse effect of A1AR antagonists (Massie et al., 2010). Subsequently, it was noted that A1AR stimulation could enhance cardiac myocyte function by improving mitochondrial function and the function of the Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA2a), and the use of a partial agonist could potentially avoid the cardiac dysrhythmias induced by A1AR (full) agonists (Voors et al., 2018). Unfortunately, the partial A1AR agonist neladenoson (BAY1067197) did not improve exercise tolerance (see also Chapter VII) in patients with heart failure (Shah et al., 2019).

2. Adenosine A2A Receptors and Cancer

Severe impairment of the cellular immune system was first associated with deficiency of adenosine deaminase in 1972 (Giblett et al., 1972). Whereas adenosine deaminase deficiency is toxic to T cells, in many subsequent studies the immunosuppressive effects of adenosine at concentrations that are not toxic to T cells have been further confirmed. Moreover, the A2AAR has been implicated as the mediator by which adaptive immunity is suppressed (Huang et al., 1997), the T cell subtypes affected have been identified, and the intracellular signaling mechanisms have been investigated (Cronstein and Sitkovsky, 2017). The impact of A2AAR in cancer development is best heralded by the pioneering report in which melanoma and lymphoma cell lines were completely rejected in A2AAR knockout mice (Ohta et al., 2006) through a mechanism involving the control of the antitumor effects of CD8 T cells. Although it had previously been established that high concentrations of adenosine were present in the extracellular fluid of solid tumors (Blay et al., 1997), the significance of that finding was not fully appreciated until the report by Ohta and colleagues. Moreover, a number of more recent studies suggest that A2AAR antagonists interact with anti-PD1 and anti-CTLA4 therapy to further enhance tumor immunity and promote tumor regression (Iannone et al., 2014; Beavis et al., 2015; Gessi et al., 2017). Indeed, A2AAR antagonists bolster cytokine release by CAR-T cells increasing their antitumor efficiency (Beavis et al., 2017). Currently, a number of A2AAR, A2BAR, and dual antagonists are at various stages of clinical development (see Chapter VII) (Yu et al., 2020). In addition, other therapeutic approaches targeting adenosine production from adenine nucleotides by ecto-5′nucleotidase (CD73) are making their way to the clinic as well (Congreve et al., 2018).

3. Adenosine Receptors and Autoimmune and Inflammatory Diseases

The potential anti-inflammatory effects of adenosine, acting at A2AAR, have been known since 1983 (Cronstein et al., 1983). Subsequently adenosine, acting at both A2AAR and A3AR, was shown to mediate many of the anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive effects of low-dose methotrexate therapy, the gold standard in the therapy of rheumatoid arthritis and psoriasis (Cronstein and Sitkovsky, 2017). Administration of A2AAR agonists, although potentially useful for treatment of inflammatory diseases, would likely have too many side effects to be tolerated, mainly due to their strong hypotensive action, so other approaches have been taken. Thus, one approach has been to develop a prodrug of an A2AAR agonist that is liberated by the action of ecto-5′-nucleotidase (CD73). Such an agent was shown to suppress inflammatory arthritis in animal models (Flögel et al., 2012) and suggests a promising approach to development of new anti-inflammatory agents.

In contrast, A3AR agonists do not appear to have the same potential for systemic toxicity, as receptor expression is not as widespread as for the A2AAR. Thus, relatively selective A3AR agonists have been tested in both animal models and the clinic for their anti-inflammatory effects. Potential clinical utility with minimal toxicity has been reported for A3AR agonists in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, and liver conditions, and thus agents remain in development for the treatment of these autoimmune disorders (reviewed in Jacobson et al., 2018).

4. Adenosine Receptors and Infectious Diseases

The anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive effects of adenosine, acting at A2AAR, have not gone unnoticed by microorganisms. Thus, adenosine has been identified as a virulence factor in Candida albicans (Smail et al., 1992; Rodrigues et al., 2016), Staphylococcus aureus, (Thammavongsa et al., 2009), and Streptococcus suis (Liu et al., 2014) that mitigates the effects of the host immune and inflammatory response on these microorganisms. Leishmania amazonensis also exploits the adenosine system to elude detection by dendritic cells, in this case through A2BAR (Figueiredo et al., 2021). To date, A2AAR or A2BAR have not been targeted as a means to enhance host responses to microorganisms for the treatment of infectious diseases for resistant organisms.

In contrast, it is increasingly clear that much of the injury associated with infections comes as a result of the active host response to the infection with tissue damage in affected tissues, much like the tissue injury triggered by inflammatory and autoimmune diseases. First postulated as a potential therapy for COVID-19 pneumonia (Abouelkhair, 2020; Falcone et al., 2020), Correale and colleagues (2020) reported on the beneficial effects of administration of aerosolized adenosine in patients with COVID-19 pneumonia. They treated 14 patients with COVID-19 interstitial pneumonitis with aerosolized adenosine and observed improved oxygenation in 13 of 14 patients (compared with 7 of 52 control patients) and improved imaging studies, although the RNA load of SARS-CoV-2 increased in 13 of 14 patients. There was one death in the adenosine-treated patients compared with 11 of 52 patients in the historic control group. Bronchospasm was observed in one of the treated patients. The authors concluded that aerosolized adenosine might be a useful adjunct to other therapies for the treatment of SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia and might be similarly effective in other types of viral pneumonia. Although it is likely that the actions of adenosine in viral pneumonitis are mediated by the actions of an adenosine receptor, it is unclear which receptor(s) that might be, although the actions of A2AAR, A2BAR, and A3AR could account for the anti-inflammatory effects observed, as noted above.

5. Adenosine A2A Receptors and Retinal Disease

The retinopathy of prematurity is the most common cause of childhood blindness. A2AAR stimulation in the retina promotes retinal vascular overgrowth, and results of recent studies indicate that A2AARs play a significant role in the development of oxygen toxicity-induced retinal angiogenesis (Taomoto et al., 2000; Liu et al., 2010; 2017). Caffeine, which is commonly used to treat apnea in neonates, was recently shown to prevent oxygen toxicity-induced retinal angiogenesis in animal models and has been suggested as a therapeutic approach to prevent retinopathy of prematurity (Zhang et al., 2017), an effect mimicked by the selective antagonism of A2AARs (Zhou et al., 2018). The antagonism of A2AARs also emerges as a novel promising strategy to dampen the local inflammatory processes involved in the degeneration of ganglion neurons in ischemic eye diseases and glaucoma that are a prevalent cause of blindness in the elderly (Liu et al., 2016; Madeira et al., 2016; Boia et al., 2017). A1AR agonists, which prevent neuronal damage from pressure and ischemia in animal models, have been tested in the treatment of glaucoma but failed in phase 3 trials to reduce intraocular pressure better than placebo (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02565173).

6. Adenosine Receptors and Bone

Adenosine A1-, A2A-, and A2B-ARs play a role in regulating bone biology by modulating osteoclast differentiation and bone remodeling as well as osteoblast differentiation and production of new bone (Strazzulla and Cronstein, 2016). A1AR stimulation is required for osteoclast differentiation, and A1AR knockout mice have mild osteopetrosis (Kara et al., 2010a,b). In contrast, A2AAR and A2BAR stimulation diminish osteoclast differentiation and stimulate new bone formation by osteoblasts (Mediero et al., 2012b; 2013; 2015b; Corciulo et al., 2016). More importantly, an A1AR antagonist, an A2AAR agonist, or dipyridamole, which blocks adenosine uptake via the equilibrative nucleoside transport protein ENT1 (SLC29A1) and thereby increases extracellular adenosine levels, stimulate bone regeneration in critical bone defects, whether applied topically or as a coating for 3D-printed β-tricalcium phosphate scaffolds (Mediero et al., 2015b; Ishack et al., 2017). Currently, dipyridamole-coated scaffolds are undergoing preclinical testing for restoration of bone.

Despite the remarkable success of joint replacement therapy, approximately 25% of implanted hip and knee prostheses will require revision due to erosion of the bone surrounding the prosthesis (Bozic et al., 2010). Application of A2AAR agonists markedly 1) diminishes the inflammation due to prosthesis wear particles, the most common cause of bone destruction leading to prosthetic joint replacement, and 2) by inhibiting osteoclast differentiation, diminishes wear particle-induced bone destruction in a murine model (Mediero et al., 2012a). Moreover, weekly low doses of methotrexate, a commonly used anti-inflammatory drug that inhibits inflammation by increasing local adenosine concentrations, similarly alleviates wear particle-induced bone destruction in mice (Mediero et al., 2015a) by an A2AAR-dependent mechanism.

7. Adenosine Receptors and Cartilage

In recent studies in both mice (Corciulo et al., 2017) and humans (St Hilaire et al., 2011), premature development of osteoarthritis has been described, and in mice, loss of A2AARs leads to spontaneous development of osteoarthritis (Corciulo et al., 2017), indicating that endogenous adenosine production acts in an autocrine fashion to maintain chondrocyte homeostasis. Moreover, treatment of rats with post-traumatic osteoarthritis with intra-articular injections of liposomal adenosine preparations prevents progression of osteoarthritis (Corciulo et al., 2017). Similarly, loss of A3ARs leads to the development of osteoarthritis in mice (Shkhyan et al., 2018), and treatment of chemically induced osteoarthritis with an A3AR agonist inhibits development of osteoarthritis (Bar-Yehuda et al., 2009). These events suggest that targeting A2ARs or A3ARs in the joint may be useful approaches to the treatment of osteoarthritis, a disabling condition affecting as many as 150 million people worldwide.

8. Adenosine Receptors and Fibrosis

Fibrosis is a common condition in a number of organs, and recent studies indicate that blockade of A2AARs can diminish excessive fibrosis in the skin, liver, and other organs in response to injury, ionizing radiation, or exposure to toxins (Shaikh and Cronstein, 2016). Indeed, in recent studies, topical application of an A2AAR antagonist prevents both scarring and radiation fibrosis in the skin (Perez-Aso et al., 2012; 2016). In some organs, A2BAR blockade can also diminish fibrosis (Shaikh and Cronstein, 2016), but recent studies suggest that in Peyronie’s disease, which involves fibrosis of the shaft of the penis, A2BAR stimulation prevents myofibroblast production of collagen (Mateus et al., 2018), suggesting that an A2BAR agonist could prevent the development of Peyronie’s disease.

9. Adenosine A2A Receptors and Sickle Cell Disease