Abstract

Increasing evidence implicates herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV1) in the pathogenesis of late-onset Alzheimer’s disease (AD). HSV1 has evolved highly sophisticated strategies to evade host immunosurveillance. One strategy involves encoding a decoy Fcγ receptor (FcγR), which blocks Fc-mediated effector functions, such as ADCC. Immunoglobulin GM (γ marker) allotypes, encoded by highly polymorphic IGHG genes on chromosome 14q32, modulate this immunoevasion strategy, and thus may act as effect modifiers of the HSV1-AD association. In this nested case-control human study, 365 closely matched case-control pairs—whose blood was drawn on average 9.6 years before AD diagnosis—were typed for GM alleles by a TaqMan® genotyping assay. APOE genotype and a genetic risk score (GRS) based on nine additional previously known AD risk genes (ABCA7, BIN1, CD33, CLU, CR1, EPHA1, MS4A4E, NECTIN2 and PICALM) were extracted from a genome-wide association study analysis. Antiviral antibodies were measured by ELISA. Conditional logistic regression models were applied. The distribution of GM 3/17 genotypes differed significantly between AD cases and controls, with higher frequency of GM 17/17 homozygotes in AD cases as compared to controls (19.8 vs. 10.7%, p = 0.001). The GM 17/17 genotype was associated with a 4-fold increased risk of AD (OR 4.142, p < 0.001). In conclusion, the results of this study demonstrate that immunoglobulin GM 17/17 genotype contributes to the risk of later AD development, independent of apolipoprotein ε4 genotype and other AD risk genes, and explain, at least in part, why every HSV1-infected person is not equally-likely to develop HSV1-associated AD.

Introduction

Late-onset Alzheimer’s disease (AD), the most common cause of major neurocognitive disorder in older adults, is a complex and progressive brain disorder. Both genetic and environmental factors have been implicated in the etiopathogenesis of this disease. Although the genome-wide association studies (GWAS) of AD have identified numerous susceptibility genes, the majority of the heritability of this disease remains unexplained. Additionally, the functional significance of most of the hitherto identified susceptibility genes in AD pathogenesis is not clear. A putative environmental (viral) factor, herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV1), which was implicated in AD pathogenesis over 30 years ago (1–3), has gained renewed significance as a result of some elegant studies in both man and mice. A very large nationwide (Taiwan), registry-based, matched retrospective cohort study found that patients with HSV infection had an almost 3-fold increased risk of developing major neurocognitive disorder relative to the non-HSV cohort, and the risk was highly reduced by anti-HSV medications (4), and prospective population-based cohort studies have confirmed an increased risk of later AD development associated with presence of anti-HSV antibodies, in particular among individuals carrying the APOE ε4 allele (5–9). Another study analyzed transcriptomes of brain samples from AD patients and controls from four different cohorts that were derived from different geographical regions in the USA. It reported increased abundance of herpesviruses, including HSV1, in AD brains (10). A recent murine study has shown that recurrent HSV1 infection induces virtually all hallmarks of AD—amyloid-β, tau, neuroinflammatory cytokines, and cognitive decline (11); similarly, in 3D brain-like tissue models, HSV1 infection induced a complete AD-like picture without any familiar AD genetic modifications (12). Another recent study indicated that HSV1 reactivation induces apoptosis in some trigeminal nerve cells, and hence that recurrent reactivation could result in nerve cell death more often than previously thought (13). Although these studies do not prove that HSV1 directly causes AD, they strongly suggest that the virus could induce AD-like changes and increase the risk of AD development in genetically predisposed individuals.

HSV1 is a common herpesvirus that persistently affects a majority of the world’s population (14). The question arises: How could such a common virus cause disease in only a subset of those infected? The answer probably lies in the presence of host genetic factors that act as effect modifiers of the HSV1-AD association.

HSV1 has evolved highly sophisticated strategies for decreasing the efficacy of the host immune response and interfering with viral clearance. One such strategy involves the generation of proteins with immune-evasion properties. Antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) is one of the most potent immunological mechanisms for killing virally infected cells. In ADCC, the host generated antiviral antibodies bind to their targets on the virus by their antigen-binding arm (Fab) and to the Fcγ receptors (FcγR) on effector cells (macrophages, natural killer cells) by their Fc arm. This bipolar binding facilitates the access of host’s killer/effector cells to the infected cells, making the latter vulnerable to attack. To evade the consequences of ADCC, HSV1 encodes FcγR-like glycoproteins (gE and gl) that bind to the Fc part of the antiviral antibodies and sterically hinder the access of host’s FcγR-expressing effector cells to the virally infected cells, essentially neutralizing an important arm of the host defense, resulting in survival advantage to the virus (15–17). This double binding of anti-HSV1 antibodies also results in internalization and degradation of antibodies in virus infected cells, leading to a clearance of specific antibodies (18).

Interestingly, GM (γ marker) allotypes (19), encoded by immunoglobulin heavy chain G (IGHG) genes on chromosome 14, modulate the HSV1 immunoevasion strategy. IgG1 proteins expressing GM 1,17 alleles have strikingly higher affinity for the HSV1 gE-gl complex (viral FcγR) than those expressing the alternative GM 1-,3 alleles (20). We previously hypothesized that because of their higher affinity to the decoy viral FcγR, subjects expressing the GM 1,17 alleles would be more likely to have their Fc domains scavenged and, therefore, would be expected to be immunologically less competent to eliminate the virus through ADCC and other Fc-mediated effector mechanisms, and be at an increased risk of developing HSV1-spurred diseases, including AD (21). This would predict a higher frequency of the GM 1,17 alleles in subjects with AD than in matched controls. In the current investigation, we tested this hypothesis in a nested case-control study, which included 365 pairs of AD cases and individually matched neurocognitive disorder-free controls, with DNA and plasma samples obtained on average 9.6 years before diagnosis.

Materials and Methods

Participants and procedures

This nested case-control study is based on samples donated to the population-based Biobank in Umeå, Sweden (Northern Sweden Health and Disease Study) (22), and has been described in greater detail in previous publications (7). Individuals who had previously donated samples to the Biobank, and who were later diagnosed with AD (see below) were matched 1:1, using a computerized procedure, by age, sex, sampling date and sub-cohort in the Biobank, to an individual that had not developed a major neurocognitive disorder up until the date of diagnosis of their corresponding case. Hence, for 365 closely matched case-control pairs, samples drawn on average 9.6 years before AD diagnosis, could be included in the present analysis.

The study was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Umeå, Sweden (09-190M and 2017/17-31).

AD diagnoses

Individuals with a clinical AD diagnoses established at the Memory Clinic at the University Hospital of Northern Sweden in Umeå, Sweden, were considered for inclusion in the data set, and included after careful review of the diagnostic procedures and AD diagnosis by an experienced specialist in geriatric medicine and after confirmation that samples for the individual and at least one suitable matching control could be found in the Biobank. The AD diagnoses were based on the criteria of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition (DSM-IV) and at least one brain imaging technique. The clinical diagnoses were also compatible with the NINCDS-ADRDA criteria. Controls were confirmed alive and free of major neurocognitive disorders at the date of diagnosis of their corresponding case using national registries.

Genotyping

GM 3/17

Genomic DNA prepared from stored blood were genotyped for the IgG1 markers GM 3/17 by a TaqMan® genotyping assay from Applied Biosystems Inc., described previously (23). Briefly, DNA at an amount of 50 ng was combined with qPCR mastermix (QuantaBio 5Prime Hot Master Mix, VWR Inc.), primer/probe mix and ultrapure water to a final volume of 20µl qPCR reaction mix. Cycling was performed on a Quantstudio5 platform (Thermo Fischer Scientific Inc.) following a program consisting of 3min 95C and 35 rounds of 20sec 95C+ 30sec 60C in the genotyping experiment type mode. Data were analyzed in the QuantStudio Design and Analysis Software v1.5.1 with the allelic discrimination computation activated.

APOE

APOE genotype and a genetic risk score (GRS) based on nine additional previously known AD risk genes (ABCA7, BIN1, CD33, CLU, CR1, EPHA1, MS4A4E, NECTIN2 and PICALM) were extracted from a genome-wide association study analysis (deCODE genetics, Reykjavik, Iceland), as described previously (8).

Serology

Sera were analyzed with ELISA for presence of anti-HSV1 IgG, anti-HSV2 IgG, anti-CMV IgG, anti-C. pneumonie IgG and anti-HSV IgM as previously described (7,24). In addition, semi-quantitative measurements were performed on anti-HSV IgG and anti-CMV IgG levels.

Statistics

SPSS Statistics, version 24 for Mac (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY), was used. AD cases and controls were compared using conditional logistic regression models to account for the 1:1 matching. Interaction variables for GM 17/17 homozygocity x APOE risk variant carriership (APOEε3/ε4, or APOEε4/ε4), and GM 17/17 homozygocity x GRS were included in the models to investigate their combined effects. A p-value < 0.05 was regarded as significant.

Results

Table 1 presents the baseline characteristics among AD cases and major neurocognitive disorder-free controls. As shown, there were no significant differences in the levels of anti-HSV IgG or presence of anti-HSV1 and anti-HSV IgM antibodies between AD cases and controls. Both GM and APOE genotype frequencies were in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium. As expected, increased prevalence of APOE risk variant carriership was found among AD cases, compared to controls (p < 0.001). The distribution of GM 3/17 genotypes differed significantly between AD cases and controls, with higher frequency of GM 17/17 homozygotes in cases as compared to controls (19.8 vs. 10.7%, p = 0.001), and, conversely, higher frequency of GM 3/3 homozygotes among controls (33.1% vs. 41.3%, p = 0.027). Since we were testing a specific one-tailed hypothesis, namely that the homozygosity for the GM 17 allele would be associated with the development of AD, no correction for multiple comparisons is warranted. However, these results would remain highly significant even if we apply the most conservative correction for multiple testing (p = 0.001 × 3= 0.003).

Table I.

Baseline characteristics among Alzheimer’s disease cases and major neurocognitive disorder-free controls

| Pairs, n | AD cases | Controls | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean ± SD | 365 | 61.2 ± 5.6 | 61.1 ± 5.6 | 0.245 |

| Male sex, n (%) | 365 | 92 (25.2) | 92 (25.2) | 1.00 |

| GM 3/17, n (%) | ||||

| GM 17/17 | 363 | 72 (19.8) | 39 (10.7) | 0.001 |

| GM 3/17 | 363 | 171 (47.1) | 174 (47.9) | 0.884 |

| GM 3/3 | 363 | 120 (33.1) | 150 (41.3) | 0.027 |

| Anti-HSV1 IgG carriership, n (%) | 354 | 323 (91.2) | 312 (88.1) | 0.215 |

| Anti-HSV IgG level, AU, mean ± SD (n)1 | 102.5 ± 21.4 (326) | 102.7 ± 21.9 (317) | 0.9122 | |

| Anti-HSV IgM carriership, n (%) | 354 | 27 (7.6) | 20 (5.6) | 0.371 |

| APOE risk variant carriership3, n (%) | 332 | 205 (61.7) | 80 (24.1) | <0.001 |

Abbreviations: AD, Alzheimer’s disease; SD, standard deviation; GM, γ-marker; HSV, herpes simplex virus; AU, arbitrary units; APOE, apolipoprotein E.

APOE ε3/ε4 or APOE ε4/ε4.

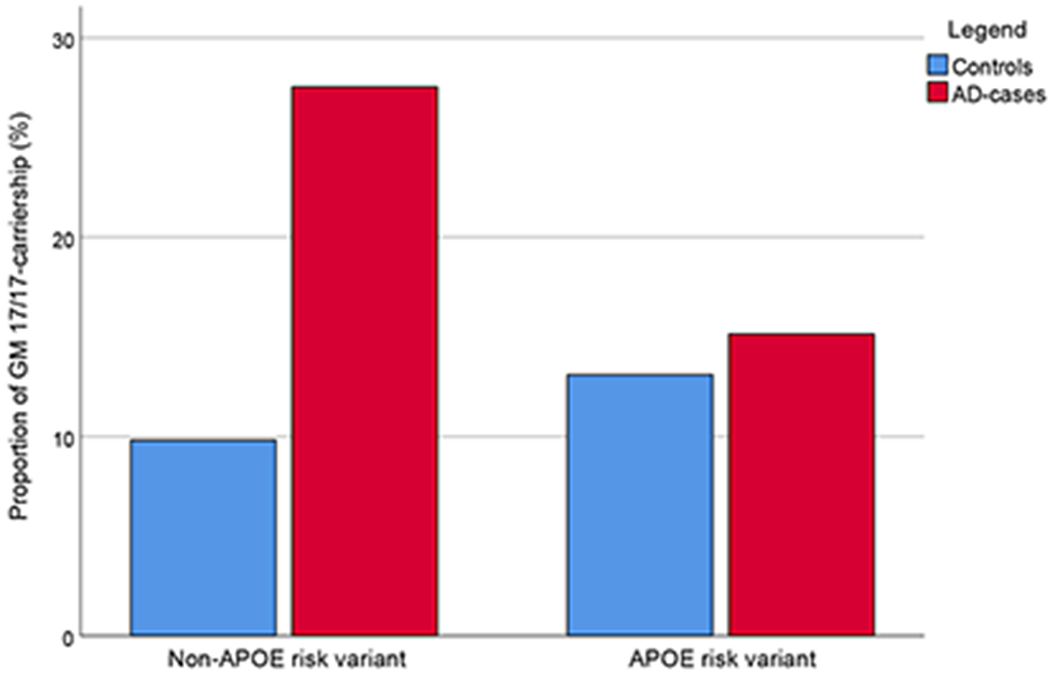

Table 2 presents the results of a multiple conditional logistic regression model with GM 17/17 carriership, APOE risk-variant carriership, and their interaction term (GM 17/17 x APOE risk variant carriership). In this model, the GM 17/17 variant was associated with a 4-fold increased risk of AD (OR 4.142, p < 0.001), adjusted for APOE risk-variant carriership and the interaction term. In addition, a negative interaction was found between GM 17/17 and APOE risk-variant carriership (OR 0.248, p = 0.007), indicating that the concomitant carriership of APOE risk-variants and GM 17/17 do not further increase the risk over having any of these factors alone. As shown in Figure 1, among carriers of an APOE risk variant (APOEε3/ε4, or APOEε4/ε4), the frequency of GM 17/17 homozygotes was similar in cases and controls, but among those without the APOE risk variants, subjects with the GM 17/17 genotype were very clearly over-represented among AD cases. [We have previously seen that the risk for APOEε2/ε4-carriers is very similar to APOEε3/ε3, and this was, therefore, not coded as a risk variant (8)]

Table II.

Conditional logistic regression model of Alzheimer’s disease risk with GM 17/17 carriership

| OR | 95 % CI | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| GM 17/17 carriership | 4.142 | 2.165 - 7.924 | <0.001 |

| APOE risk-variant carriership1 | 7.323 | 4.596 - 11.667 | <0.001 |

| GM 17/17 x APOE risk-variant carriership1 | 0.248 | 0.090 – 0.681 | 0.007 |

Abbreviations: GM, γ-marker; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; APOE, apolipoprotein E.

APOE ε3/ε4 or APOE ε4/ε4.

Figure 1.

Proportions of GM 17/17 carriership according to APOE risk variant (APOE ε3/ε4 or APOE ε4/ε4) carriership and Alzheimer’s disease-case or control status.

We have previously constructed a “genetic risk score”, based on nine other AD risk genes (ABCA7, BIN1, CD33, CLU, CR1, EPHA1, MS4A4E, NECTIN2 and PICALM), and confirmed that this risk score is associated with an increased AD risk in our study population (8). This genetic risk score did not interact with the GM 17/17 genotype and did not decrease its effect when added to the model (data not shown).

Table 3 presents comparisons of baseline characteristics between GM 17/17 carriers and non-carriers. As shown, the seroprevalence of HSV1 was similar in the two groups; however, GM 17/17 homozygous subjects had significantly lower levels of anti-HSV IgG antibody levels (95 vs. 104 AU, p = 0.003). To further explore the effects of GM17/17 carriership, APOE risk variant carriership and the GRS on HSV antibody parameters (anti-HSV IgG level and anti-HSV IgM carriership), multiple regression models (multiple linear and multiple logistic regression, respectively) were constructed with the antibody parameters as dependent variable and the three genetic factors as independent variables, for all anti-HSV1 IgG positive participants (AD cases and controls together). In these models, only GM17/17 carriership associated significantly with anti-HSV IgG level (unstandardized β −7.50, p = 0.003), and only APOE risk variant carriership significantly increased the probability of having anti-HSV IgM antibodies, indicating recent HSV reactivation (OR 2.97, p = 0.002 [there were 10.6% and 4.3% with anti-HSV IgM antibodies among anti-HSV1-positive APOE risk variant carriers and non-carriers, respectively]). The GRS did not associate with any of the antibody parameters. Additional analyses of anti-CMV IgG or anti-C. pneumonie IgG carriership or levels showed no significant difference between the GM 17/17 carriers and non-carriers (data not shown).

Table III.

Baseline characteristics among GM 17/17 carriers and non-carriers

| GM 17/17 carriers | GM 17/17 non-carriers | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean ± SD (n) | 61.4 ± 5.1 (111) | 61.1 ± 5.7 (617) | 0.645 |

| Male sex, n (%) | 27 (24.3) | 157 (25.4) | 0.802 |

| Anti-HSV1 IgG carriership, n (%) | 100 (90.9) | 541 (89.3) | 0.606 |

| Anti-HSV IgG level, AU, mean ± SD (n)1 | 95.4 ± 26.5 (100) | 104.0 ± 20.4 (541) | 0.003 |

| Anti-HSV IgM carriership, n (%) | 6 (5.5) | 41 (6.8) | 0.609 |

| APOE risk-variant carriership2, n (%) | 44 (41.1) | 258 (43.9) | 0.597 |

Abbreviations: GM, γ-marker; SD, standard deviation; HSV, herpes simplex virus; AU, arbitrary units; APOE, apolipoprotein E.

Discussion

The results presented here show a distinct association between homozygosity for the GM 17 allele and risk of developing AD. This is the first clear confirmation of this variant as a common and strong genetic risk factor for AD, previously hypothesized based on its known effects on the development of immunity towards HSV1. Thereby, the present results also provide further support for the involvement of HSV1 in AD development. Although we did not type for GM 1 and GM 21 alleles in this investigation, subjects positive for GM 17 are most likely positive for these determinants as well because there is almost absolute linkage disequilibrium among these alleles in Caucasians (19). So, the actual risk allele (s) may be any or all three alleles, or, another locus on chromosome 14 whose alleles are in linkage disequilibrium with GM alleles. The aim of this investigation was not a hypothesis-free global test involving all known GM alleles. Rather, we tested a specific hypothesis, which predicted that GM 17/17 genotype would have a higher frequency in AD patients than in matched controls (21). The hypothesis was based on the modulating influence of GM 3/17 alleles on an immunoevasion strategy of HSV1 (20). Thus, the results of this investigation not only identify a novel risk factor for AD, but also one whose potential functional significance in HSV1-associated AD is known.

In addition to the potential indirect influence of GM alleles on AD pathogenesis through their modulation of viral immunoevasion strategies described above, a direct role in the pathology of this disease could not be excluded. For instance, GM alleles could contribute to the microglia-mediated antibody-dependent cellular phagocytosis (ADCP) of β-amyloid in AD brains. Perhaps, GM 17-expressing anti-β-amyloid IgG antibodies have reduced affinity for the FcγRs expressed on microglia, resulting in reduced phagocytosis of β-amyloid plaques and their clearance from the brain. In support of this mechanism, we have shown that IgG antibodies expressing the GM 3 allele—an alternative to GM 17 and associated with relative protection from AD in this investigation—interacts with FcγR alleles expressed on effector cells and causes enhanced ADCC of HSV1-infected cells (25). Similar mechanisms are likely to be involved in ADCP as well. A range of microbial organisms—viruses, bacteria, and fungi—have been suggested to contribute to the infectious etiology of AD (26). Whether or not GM 3/17 alleles influence immunity to these pathogens warrants further investigation.

Subjects expressing the GM 17/17 genotype had significantly lower levels of anti-HSV IgG antibodies, in line with a potential increased clearance of antibodies through gE/gI-mediated binding and internalization. These subjects would be expected to be immunologically less competent to eliminate the virus and, therefore, be at an increased risk of HSV-spurred diseases. Our finding of a significant association between the GM 17/17 genotype and an increased risk of AD is consistent with this observation, and of the previously indicated involvement of HSV1 in AD pathogenesis. The GM 17/17 variant, as well as APOEε4 and other AD risk genes interacting with HSV1 carriage might together explain why some individuals carrying HSV1 do not and others do develop HSV1-associated AD in late in life. The genetic factors investigated in this study affected anti-HSV antibody parameters differently, and while GM 17/17 carriage associated with lower anti-HSV IgG level, APOEε4 carriage was associated with increased risk of reactivated infection (anti-HSV IgM presence) and the GRS did not affect any of the parameters measured. The potentially complex interactions between host genes, immune mechanisms and virus in the development of late consequences of infection should be explored in future studies. The properties of anti-HSV1 antibodies among GM 17/17 carriers and non-carriers should also be investigated in greater detail. The observed negative interaction between APOEε4 and GM 17/17 indicates that these strong genetic risk factors are by themselves, and independently, sufficient for a large increased risk for AD; but, for some reason, having both would not enhance the risk further. It should be noted, however, that the sample size is not sufficient for clarifying the full interaction effects matrix among the three variables (i.e. APOEε4, GM 17/17 and HSV1).

If GM genes are associated with AD, why have they not been detected by the GWAS of AD? The most likely reason is that they are not being evaluated by current GWAS. Although GM alleles are common—some with frequency >70%—none of the GWAS of AD, to our knowledge, included these determinants in their genotyping platforms. IgG gene segments harboring GM genes are highly homologous and apparently not amenable to the high throughput genotyping technology employed in GWAS. Furthermore, because these variants were not typed in the HapMap project, they cannot be imputed (27,28). Even in the 1000 Genomes project, the coverage of this region is very low, resulting in poor quality of imputation. Therefore, a candidate gene approach is necessary to elucidate the role of the immunoglobulin GM gene complex in the immunobiology of AD.

In a previous study of Italian AD subjects (23), we did not find a significant association between GM genotypes and AD, but the two studies ae not comparable. In addition to the differences in the geographic origin of the subjects and the experimental design (case-control vs. nested case-control), the previous study included only 56 AD patients (of which only 2 were GM 17/17 homozygotes), and thus it was probably underpowered to detect an association.

This investigation involved white/Caucasian subjects from Northern Sweden. Every major racial/geographic population group is characterized by a unique array of several GM haplotypes (19). The findings reported here need to be replicated in large multicenter, multiethnic cohorts. We hope these results would inspire further studies to investigate the role of hitherto understudied/neglected GM gene complex in the immunobiology of Alzheimer’s disease.

In conclusion, immunoglobulin GM 17/17 genotype contributes to the risk of later AD development, independent of apolipoprotein ε4 genotype and other AD risk genes. These results are in line with the increasing evidence of HSV1 as a potential cause of AD in genetically predisposed individuals.

Key Points.

GM 17/17 genotype was associated with a 4-fold increased risk of AD

Association is independent of apolipoprotein ε4 genotype and other AD risk genes

Results unify the viral (HSV1) and genetic etiologies of AD

Acknowledgments

Grant Support: The nested case-control study was conducted in the context of the CHANCES project, funded in the FP7 framework program of DG-RESEARCH in the European Commission. The study was further supported financially by grants from the US National Institutes of Health, Region of Västerbotten, Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation, Umeå University, Swedish Dementia Association, and the Swedish Alzheimer Fund. Some genotype information was extracted from a genome-wide association analysis provided by deCODE genetics, Reykjavik, Iceland.

References

- 1.Itzhaki RF 2018. Corroboration of a major role for herpes simplex virus type 1 in Alzheimer’s disease. Front. Aging Neurosci 10: 324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mangold CA, and Szpara ML. 2019. Persistent infection with herpes simplex virus 1 and Alzheimer’s disease—a call to study how variability in both virus and host may impact disease. Viruses Oct 20;11(10). pii: E966. doi: 10.3390/v11100966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ball MJ 1982. Limbic predilection in Alzheimer dementia: is reactivated herpes virus involved? Can. J. Neurol. Sci 9:303–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tzeng NS, Chung CH, Lin FH, et al. 2018. Anti-herpetic medications and reduced risk of dementia in patients with herpes simplex virus infections—a nationwide, population-based cohort study in Taiwan. Neurotherapeutics 15:417–429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Letenneur L, Peres K, Fleury H, et al. 2008. Seropositivity to herpes simplex virus antibodies and risk of Alzheimer’s disease: a population-based cohort study. PLoS ONE 3, e3637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lovheim H, Gilthorpe J, Adolfsson R, Nilsson LG, and Elgh F. 2015. Reactivated herpes simplex infection increases the risk of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 11: 593–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lovheim H, Gilthorpe J, Johansson A, Eriksson S, Hallmans G, Elgh F. 2015. Herpes simplex infection and the risk of Alzheimer’s disease: A nested case-control study. Alzheimers Dement. 11:587–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lopatko Lindman K, Weidung B, Olsson J, et al. 2019. A genetic signature including apolipoprotein Eepsilon4 potentiates the risk of herpes simplex-associated Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. (N. Y.) 5:697–704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lovheim H, Norman T, Weidung B, et al. 2019. Herpes simplex virus, APOEε4, and cognitive decline in old age: Results from the Betula cohort study. J. Alzheimers Dis 67: 211–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Readhead B, Haure-Mirande JV, Funk CC, et al. 2018. Multiscale analysis of independent Alzheimer’s cohorts finds disruption of molecular, genetic, and clinical networks by human herpesvirus. Neuron 99:64–82.e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Chiara G, Piacentini R, Fabiani M, et al. 2019. Recurrent herpes simplex virus-1 infection induces hallmarks of neurodegeneration and cognitive deficits in mice. PLoS Pathog. 15: e1007617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cairns DM, Rouleau N, Parker RN, et al. 2020. A 3D human brain–like tissue model of herpes-induced Alzheimer’s disease. Sci. Adv 6: eaay8828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Doll JR, Hoebe K, Thompson RL, and Sawtell NM. 2020. Resolution of herpes simplex virus reactivation in vivo results in neuronal destruction. PLoS Pathog. 16: e1008296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Olsson J, Kok E, Adolfsson R, Lövheim H, and Elgh F. 2017. Herpes virus seroepidemiology in the adult Swedish population. Immun. Ageing 14:10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frank I, and Friedman HM. 1989. A novel function of the herpes simplex virus type 1 Fc receptor: participation in bipolar bridging of antiviral immunoglobulin G. J. Virol 63:4479–4488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sprague ER, Wang C, Baker D, and Bjorkman PJ. 2006. Crystal structure of the HSV-1 Fc receptor bound to Fc reveals a mechanism for antibody bipolar bridging. PLoS Biol. 4(6):e148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lubinski JM, Lazear HM, Awasthi S, Wang F, and Friedman HM. 2011. The herpes simplex virus 1 IgG Fc receptor blocks antibody-mediated complement activation and antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity in vivo. J. Virol 85:3239–3249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ndjamen B, Farley AH, Lee T, Fraser SE, and Bjorkman PJ. 2014. The herpes virus Fc receptor gE-gI mediates antibody bipolar bridging to clear viral antigens from the cell surface. PLoS Pathog. 10: e1003961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oxelius VA, and Pandey JP. 2013. Human immunoglobulin constant heavy G chain (IGHG) (Fcγ) (GM) genes, defining innate variants of IgG molecules and B cells, have impact on disease and therapy. Clin. Immunol 149:475–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Atherton A, Armour KL, Bell S, Minson AC, and Clark MR. 2000. The herpes simplex virus type 1 Fc receptor discriminates between IgG1 allotypes. Eur. J. Immunol 30:2540–2547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pandey JP 2009. Immunoglobulin GM genes as functional risk and protective factors for the development of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimer’s Dis 17:753–756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hallmans G, Agren A, Johansson G, et al. 2003. Cardiovascular disease and diabetes in the Northern Sweden Health and Disease Study Cohort - evaluation of risk factors and their interactions. Scand. J. Public Health Suppl 61:18–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pandey JP, Kothera RT, Liu S, Costa AS, Mancuso R, and Agostini S. 2019. Immunoglobulin genes and immunity to HSV1 in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimer’s Dis 70:917–924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lovheim H, Olsson J, Weidung B, et al. 2018. Interaction between cytomegalovirus and herpes simplex virus type 1 associated with the risk of Alzheimer’s disease development. J. Alzheimers Dis 61: 939–945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moraru M, Black LE, Muntasell A, et al. 2015. NK cells and immunoglobulins interplay in defense against herpes simplex virus type 1: epistatic interaction of CD16A and IgG1 allotypes of variable affinity modulates antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity and susceptibility to clinical reactivation. J. Immunol 195:1676–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kumar D, Choi SH, Washicosky KJ, et al. Amyloid-β peptide protects against microbial infection in mouse and worm models of Alzheimer’s disease. Sci. Transl. Med 2016; 8: 340ra72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pandey JP 2010. Candidate gene approach’s missing link. Science 329:1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pandey JP 2010. Genomewide association studies and assessment of the risk of disease. N. Engl. J. Med 363:2076–2077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]