Abstract

We evaluated the virucidal efficacy of light-activated fluorinated TiO2 surface coatings on human norovirus and several surrogates (bacteriophage MS2, feline calcivirus (FCV), and murine norovirus (MNV)). Inactivation of viruses on surfaces exposed to a common fluorescent lamp was monitored and the effects of UVA intensity, temperature, and fluoride content were assessed. Destruction of RNA and capsid oxidation were evaluated for human norovirus inocula on the F-TiO2 surfaces, while contact with the F-TiO2 surface and exposure to residual UVA radiation of 10 μW cm−2 for 60 min resulted in infectivity reductions for the norovirus surrogates of 2–3 log10. Infectivity reductions on pristine TiO2 surfaces in identical conditions were over 2 orders of magnitude lower. Under realistic room lighting conditions, MS2 infectivity declined below the lower detection limit after 12 h. Reductions in RNA were generally low, with the exception of GII.4, while capsid protein oxidation likely played a larger role in infectivity loss. Inactivation of norovirus surrogates occurred significantly faster on F-TiO2 compared to pristine TiO2 surfaces. The material demonstrated antiviral action against human norovirus surrogates and was shown to effectively inhibit MS2 when exposed to residual UVA present in fluorescent room lighting conditions in a laboratory setting.

Keywords: F-TiO2, Human norovirus, Norovirus surrogates, Surface disinfection

1. Introduction

Human noroviruses are the cause of 80–90% of reported outbreaks of nonbacterial gastroenteritis worldwide [1]. The viruses are transmitted mainly through the fecal-oral route, including consumption of contaminated food and water [2–4]. Yet, numerous outbreaks occurring in public settings, such as cruise ships, nursing homes, hospitals, and daycare centers, strongly indicate that food is rarely the main vehicle; rather, high persistence, infectivity, and transmissibility collectively implicate contaminated surfaces as a main reservoir for the spread of NoVs [5–7]. Currently, strict compliance with hygiene practices such as the use of chemical disinfectants and hand washing is recommended to break the cycle of NoV transmission by inactivating or physically removing the virus particles from fomites or hands [8]. However, the resulting effects are transient, having no residual antimicrobial activity. Even if sufficient decontamination is achieved, surfaces are susceptible to re-contamination by contact with affected or asymptomatic carriers.

A variety of antimicrobial surfaces have been investigated for controlling surface-mediated transmission of pathogens, with the goal of providing continuous inactivation in order to alleviate the ephemeral effects of chemical cleaning [9,10]. Most technologies rely on leaching of chemical biocides from the surfaces, including silver ions [11], copper ions [12–14], quaternary ammonium compounds [15], and phenolic species (e.g. triclosan [16]). Although the overuse of organic biocides has been implicated in contributing to bacterial resistance [17], antimicrobial copper was recently demonstrated to effectively inactivate NoVs and degrade the genome, reducing the risk of horizontal gene transfer [18]. Nonetheless, copper metal is not suitable for all surfaces and more than one antimicrobial tool is generally needed to effectively control rapidly-evolving pathogenic threats.

Titanium dioxide (TiO2) has been the subject of profuse research on many fronts and is capable of inactivating a broad range of microorganisms via photocatalytic production of cytotoxic reactive oxygen species (ROS) – primarily ·OH. The mechanism of ·OH generation is well-known, involving oxidation of chemisorbed OH− by TiO2 valence band holes (h+) [19,20]. In pristine TiO2, h+’s are formed only by absorption of UVA photons (λ < 387 nm) which promote electrons from the valence band to the conduction band. This requirement of high energy photons has limited the applicability of TiO2 photocatalytic disinfection, particularly in indoor environments, and spurned the pursuit of doped TiO2 or other more sophisticated photocatalysts that can utilize visible-range photons to a greater extent [21–23]. In this work, we prepared TiO2 surfaces coatings that were modified using a simple solution fluorination process, and demonstrated its ability to utilize the residual UVA radiation present in indoor fluorescent lighting for rapid inactivation of NoV.

Surface-fluorinated TiO2 (F-TiO2) has been shown by several groups to produce ·OH under UVA exposure at a significantly higher efficiency than the unmodified catalyst [24–26]. Therein, a simple ligand exchange between fluoride anions and surface −OH groups is achieved by soaking TiO2 in a NaF solution, as in Reaction (1) [24,27,28].

| (1) |

| (2) |

Enhanced photocatalytic activity of F-TiO2 is likely due to several concurrent effects including reduced UV reflectance and more negative zeta potential promoting greater adsorption of certain molecules [26]. More importantly, −F promotes the degradation of organic molecules by free ·OH in bulk phase as in Reaction (2), rather than direct oxidation by h+ at the surface or chemisorbed ·OH [24]. Free radicals, which become air-borne or dissolved in water, have been previously shown to play a larger role in viral inactivation by TiO2, compared to heterogeneous oxidation on the catalyst surface [19].

In this study, we evaluated the photocatalytic inactivation of NoVs using pristine TiO2 and F-TiO2 films. The contact killing activities of these films were evaluated with three NoV surrogates: coliphage MS2, feline calicivirus (FCV), and murine norovirus (MNV). Antiviral performance of F-TiO2 film was conducted in a simulated workspace setting under realistic lighting conditions to better characterize its potential real-world application.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Viruses

A GI.1 norovirus positive fecal specimen was provided by Dr. Christine Moe at Emory University and a GII.4 norovirus-positive fecal specimen was obtained from a 2009 cruise ship outbreak of viral gastroenteritis. Bacteriophage MS2 (ATCC No. 15597-B1) was cultivated and assayed using Escherichia coli Famp (ATCC No. 700891) following the previously reported protocol [29]. The titer of the purified MS2 stock was approximately 1010 PFU mL−1. MNV (strain CW3), provided by Dr. Skip Virgin, Washington University School of Medicine (St Louis, Mo, USA), was propagated and assayed in RAW 264.7 cells (ATCC No. TIB-71, Manassas, VA). FCV strain F9 ATCC No.VR-782 was propagated and assayed in Crandell Reese Feline Kidney cells (CRfK ATCC No. CCL-94), as previously described [30]. The infectivity titers of MNV and FCV stocks were approximately108.0 and 108.9 PFU mL−1, respectively. Virus stocks were stored in aliquots at −80 °C, and each aliquot was thawed and further purified by centrifugation and/or filtration for each experiment.

2.2. TiO2 and F-TiO2 film preparation

TiO2 nanoparticles (P25, Degussa Co., Germany) were added to 500 g L−1 suspension of polyethylene glycol (PEG, 500 g L−1) at 10:1 w/w ratio and mixed for 30 min using a mortar and pestle. The resulting coating reagent was spread onto a glass plate, dried at room temperature, and calcined at 450 °C for 30 min to mineralize PEG. Surface-fluorinated TiO2 was prepared by immersing the TiO2-coated glass plate in a 30 mM NaF solution (pH 3.5, adjusted with HCl) for 30 min and then air-drying [24].

2.3. Surface inactivation experiment

Virus-contaminated surface coupons were prepared by depositing 25 μL of pooled (MNV/FCV) or each individual virus suspension (MS2, GI.1 or GII.4) on TiO2 or F-TiO2 films, and dried for 1.5 h at room temperature under dark. The sample surface was then exposed to a commercial fluorescent lamp (4 W, GE Co., USA). The light intensity was controlled by adjusting the distance between the lamp source and the sample and measured at a representative UVA wavelength of 365 nm using a UVX radiometer, equipped with a 365 nm UVA detector (UVP Co., Upland, CA). Visible range experiments were conducted by using UV cut-off filter (Optivex® UV glass filters, Pegasus lighting Co., USA) which blocks irradiation of UV fractions in lamp emission spectrum (<400 nm). After a predetermined time (up to 120 min), the coupons were vortexed for 1 min in 2 mL elution buffer (5% fetal bovine serum and 0.05% Tween 80® in distilled water). Eluted viruses were plaque-assayed (MS2, MNV, and FCV) or the RNA copy number was quantified (MS2, GI.1, and GII.4). To evaluate oxidative damage of the capsid proteins during virus inactivation, the concentration of oxidized proteins was assayed using the OxyELISA oxidized protein quantitation kit (Millipore Co.), following the manufacturer’s instructions. Protein concentration was standardized to 10 lg mL−1 by concentrating the harvested viruses using a stirred cell equipped with 1500 MWCO UF membrane (Amicon® Ultra, Millipore Co., Billerica, MA), followed by a Bradford quantification. Control experiments were performed using uncoated glass plates with light and coated glass without light. All experimental values reported herein were from averaging at least four replicate analyses of two independent experiments. Significant differences in viral reductions between different test conditions were assessed using the Student’s t-test.

2.4. Reverse transcription-PCR assays

Sample aliquots (100 μL) were incubated with 1 μL of RNase One™ Ribonuclease (Promega, Madison, WI) for 1 h at 37 °C, after which the reaction was stopped by adding 1 μL of RNase inhibitor (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Viral RNAs were then extracted using the MagMAX™−96 Viral RNA Isolation Kit (Ambion, Austin, TX) and the KingFisher® magnetic particle processor, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Oligonucleotide primers and probes for MS2, GI.1 norovirus, and GII.4 norovirus used in this study are listed in Table 1 [31–33]. Viral RNAs were quantified by Taq-Man-based real-time RT-PCR using the QuantiTect Probe RT-PCR kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) on an ABI 7500 platform (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) [8]. Reduction of viral RNA copy numbers was determined by calculating log10 (CtT − Ct0)/k, where CtT is the threshold crossing value (Ct) of viral RNA of a treated sample; Ct0 is the initial Ct-value of viral RNA of an untreated sample, and k is the slope of the linear regression for Ct-value versus the logarithm of the viral RNA copy numbers. Average slopes of the standard curves for MS2, GI.1, and GII.4 were −2.99 ± 0.10 (r2 ⩾ 0.950), −3.9 ± 0.10 (r2 ⩾ 0.969), and −2.96 ± 0.3 (r2 ⩾ 0.928), respectively.

Table 1.

Oligonucleotide primers and probes used in this study.

| Primer/probea | Sequence 5′ → 3′b | Product length | Positionc | Refs. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GI.1 | COG1F | CGY TGG ATG CGI TTY CAT GA | 85 | 5291 | [32,33] |

| COG1R | CTT AGA CGC CAT CAT CAT TYA C | 5375 | |||

| RING1c-probe | AGA TYG CGI TCI CCT GTC CA | 5340 | |||

| GII.4 | COG2F | CAR GAR BCN ATG TTY AGR TGG ATG AG | 98 | 5003 | [32,33] |

| COG2R | TCG ACG CCA TCT TCA TTC ACA | 5100 | |||

| RING2-probe | TGG GAG GGC GAT CGC AAT CT | 5048 | |||

| MS2 | MS2F | ATCCATTTTGGTAACGCCG | 68 | 2745 | [31] |

| MS2R | TGCAATCTCACTGGGACATAT | 2813 |

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Virus inactivation by F-TiO2 film

Fig. 1 shows the results of experiments performed to evaluate the effects of incident UVA intensity, fluoride concentration (i.e., in solution used for F-TiO2 preparation), and temperature on MS2 inactivation by the F-TiO2 film. Values of 10 μW cm−2, 30 mM, and 24 °C, respectively, were chosen as the baseline conditions for these parameters throughout this study. As seen in Fig. 1a, MS2 was inactivated more rapidly at higher light intensity. When the F-TiO2 coated coupons were irradiated with fluorescent light at 3.5 μW cm−2 in the UVA range, 1 log10 (90%) MS2 inactivation was achieved in approximately 42 min, whereas a similar level of inactivation was obtained after exposure for 15 min at 15 μW cm−2. The reduction of MS2 infectivity thus correlated with the square root of UVA intensity (r2 = 0.97; inset in Fig. 1a). Increasing the temperature from 12 °C to 32 °C resulted in a decrease in infectivity of MS2 on F-TiO2 coated coupons by 1.5–2.6 log10 PFU mL−1 (Fig. 1b). Additionally, altering the fluoride concentration of the NaF precursor solution from 10 to 30 mM led to a higher reduction of MS2 titers (1.89–2.6 log10 PFU mL−1 after 60 min exposure). When a cutoff filter was used to remove UVA radiation, exposure to the fluorescent light for 60 min did not have any effect on MS2 infectivity (Fig. 1d).

Fig. 1.

Effects of (a) incident UVA intensity, (b) temperature, and (c) fluoride concentration (in solution used for F-TiO2 preparation) on MS2 inactivation by the F-TiO2 film. Results in (d) confirms that viral photo-inactivation was solely due to photons in UVA region.

The positive effects of UVA intensity on photocatalytic inactivation of MS2 (Fig. 1a) coupled with the result obtained using a UV filter (Fig. 1d) confirm that the viruses are affected by UVA-initiated reactions. The observation of faster inactivation at higher temperatures (Fig. 1b) was consistent with previous studies which have shown that higher temperatures result in an increased production of (and reactivity of) ·OH [34]. Although the virucidal action of free radicals is not well documented in the literature, in bacterial inactivation, ·OH is known to damage cell walls/membranes or cause oxidation of coenzymes, thereby killing the microorganism [19,34–36]. Similar oxidative damages on viruses by ·OH are expected and, consistently, we observed that surface fluorination of the TiO2 coatings enhanced the photocatalytic MS2 inactivation by 4 times and resulted in over 2-log10 reduced infectivity of the three tested NoV-surrogate viruses after 60 min. According to previous studies, fluorination of TiO2 is thought to accelerate desorption of ·OH from the TiO2 surface, which would help to eliminate the diffusion limitations associated with degradation at the catalyst surface. This difference is speculated to be especially beneficial for virus inactivation, wherein a relatively substantial exposure to oxidants is required to rapidly affect the viral infectivity. It is also worth noting the results of Janczyk et al., who reported evidence of singlet oxygen (1O2) production by irradiated F-TiO2 [37]. While most literature has attributed photocatalytic enhancement upon surface fluorination to enhanced ·OH generation, photocatalytically produced 1O2 might have also contributed to the observed enhanced kinetics, as it is known to react strongly with proteins and to effectively inactivate viruses [38].

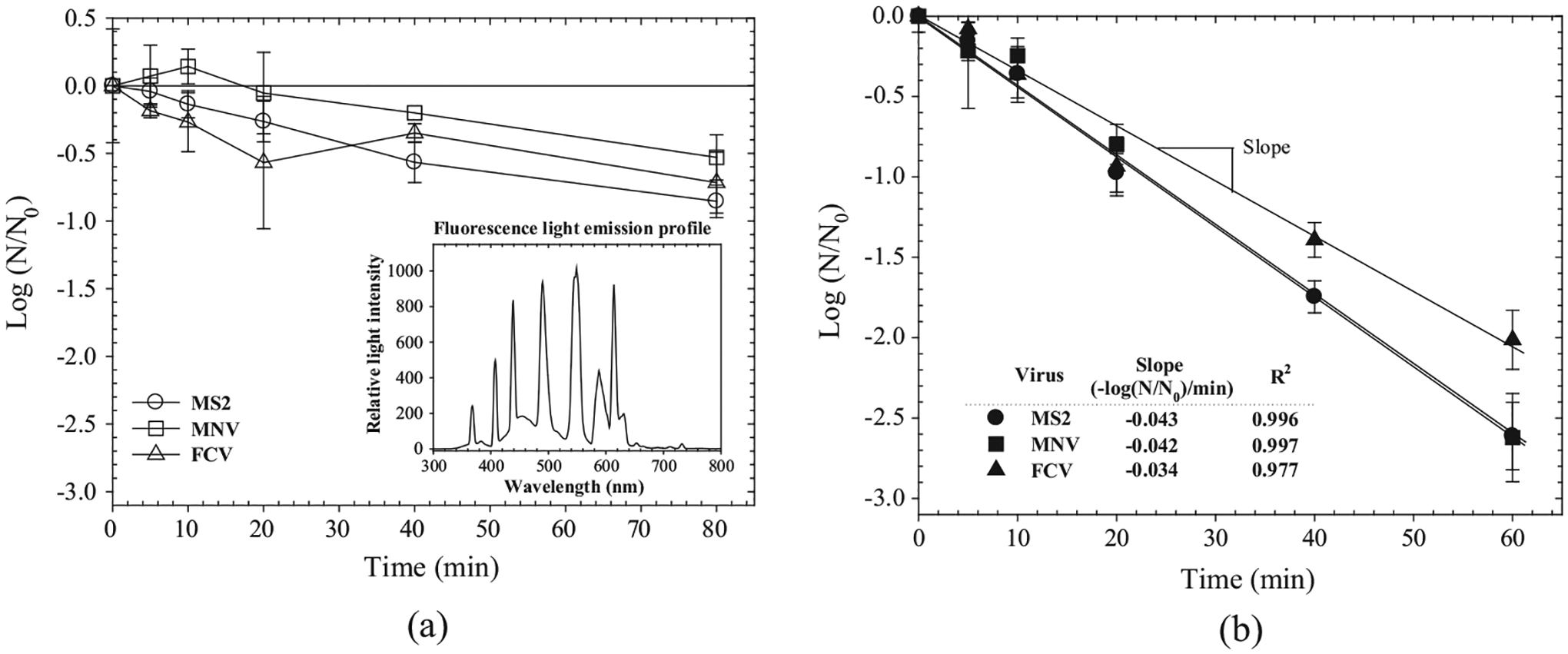

3.2. Inactivation kinetics of MS2, MNV and FCV

Inactivation kinetics of MS2, MNV and FCV on an unmodified TiO2 film is shown in Fig. 2a, along with the measured emission profile of the fluorescent lamp employed in this study. Analysis of the light-emission profile of fluorescent light showed that less than 5% (Relative light intensity: footnote of Fig. 2a) of fluorescent light had a wavelength of ⩽400 nm, attributed mainly to the mercury emission line at 365 nm. Exposure to fluorescence light for 80 min on TiO2 film reduced infectivity titers of MS2, FCV, and MNV by 0.85, 0.72, and 0.53 log10 PFU mL−1, respectively (Fig. 2a). Identical experiments conducted using F-TiO2 surfaces showed much faster kinetics, with an infectivity reduction of 2.6, 2.0, and 2.6 log10 PFU mL−1 for MS2, FCV and MNV, respectively, after 60 min (Fig. 2b). The results suggest that the F-TiO2 coating exhibited approximately 4 times faster inactivation performance against NoV surrogates compared to the pristine TiO2 coating. The extent of reduction of FCV at 60 min was 20% (as slope value in Fig. 2b) less than that of MNV and MS2 (p-values of 0.041 and 0.035, respectively).

Fig. 2.

Inactivation kinetics of MS2, MNV, and FCV deposited on a dry surface coated with (a) TiO2 and (b) F-TiO2 (UVA Intensity = 10 μW cm−2, Temp = 24 °C).

3.3. Inactivation mechanisms

When GII.1 and GII.4 were in contact with F-TiO2 film for 120 min under fluorescent light irradiation, reductions in RNA titers for GI.1 and GII.4 were 0.0 and 1.1 log10 PCR RNA copy number, respectively (Table 2). Similarly, even though the infectivity of MS2 on F-TiO2 film decreased by 3.6 log10 PFU mL−1 after 120 min at 10 μW cm−2 UVA, there were no significant reductions for MS2 RNA copy titer. In contrast, capsid proteins of MS2 and GI.1, which had been in contact with fluorescent light-activated F-TiO2 coated coupons for 60 min, were oxidized by 64% and 59% of total proteins, respectively, as shown in Fig. 3. In control tests performed on fluorescent light-exposed cover glass (no TiO2 coating), or on F-TiO2 film in dark conditions, oxidized protein concentrations were measured to be 0.5% and 0.6% of total proteins for MS2 and GI.1, respectively.

Table 2.

Surface inactivation kinetics of fluorescent TiO2 film on MS2, G1 and GII NoVs (UVA intensity = 10 μW cm−2, Temp = 24 °C).

| Exposure time (min)a | Reduction in infectivity (Log10 PFU) | Reduction in RNA titera (log10 RNA copy numbers) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MS2 | MS2 | GI.1 | GII.4 | |

| 0 | 0.0 ± 0.2 | 0.0 ± 0.2 | 0.0 ± 0.3 | 0.0 ± 0.5 |

| 30 | 1.3 ± 0.2 | 0.0 ± 0.3 | 0.0 ± 0.3 | 0.5 ± 0.3 |

| 60 | 2.6 ± 0.1 | 0.1 ± 0.4 | 0.0 ± 0.4 | 0.7 ± 0.4 |

| 120 | 3.6 ± 0.6 | 0.0 ± 0.6 | 0.0 ± 0.6 | 1.1 ± 0.6 |

Each value represents an average of six replicates from two independent experiments with standard deviation.

Fig. 3.

Concentrations of protein and oxidized protein of (a) MS2 and (b) GI.1 before and after F-TiO2 surface exposure to a fluorescent lamp.

The lack of reduction in viral RNA for MS2 and GI.1 suggests that infectivity loss was not directly related to RNA damage within our experimental time range. Rather, our observation that a > 59% of capsid proteins of these viruses were oxidized after 120 min indicates that the likely cause of inactivation is denaturation of capsid proteins, which are primarily responsible for the integrity of the virus and attachment to host cells. Consistently, Sano et al. reported that carbonyl-group formation, resulting from oxidation of capsid proteins by free chlorine, was correlated with the level of protein oxidation and possibly infectivity loss [39]. Overall, the broad spectrum of antiviral activity of activated F-TiO2 film and the similarity in the extent of oxidation damage of capsid proteins between GI.1 and MS2 suggest that F-TiO2 film is likely to result in rapid inactivation of human NoV as well via the photochemical production of ·OH and 1O2.

3.4. Practical approaches

Experiments were also performed to evaluate the virucidal activity of F-TiO2 film in a realistic office setting, wherein the UVA intensity from typical room lighting at the samples, placed on top of an office room table, was 2.4 μW cm−2. Initial infectious titer of coliphage MS2 was 8.2 log10 PFU mL−1. After 12 h of exposure, the infectivity of MS2 on F-TiO2 coated coupons declined below a lower level of quantification of plaque assay (3.1 log10 PFU) indicating inactivation great than 5.1 log10 PFU, while coliphage MS2 on cover glasses (no TiO2) remained significantly higher with only a reduction of 1.3 log10 from initial titers.

In fact, common fluorescent bulbs frequently produce minor emissions at 365 nm, with peaks at 378 and 313 nm also present in some products. The photocatalytic surface inactivation results obtained in a realistic office setting further validate the potential for F-TiO2 to prevent virus transmission in the indoor environment. However, antimicrobial efficacy is reliant upon the residual UVA emission commonly emitted by mercury-based fluorescent lamps. Other types of lighting that have no UVA emission lines, such as white light LED bulbs, are not expected to result in surface inactivation of viruses by F-TiO2. Nonetheless, given that most commercial buildings presently employ fluorescent room lighting, the photocatalytic F-TiO2 coatings demonstrated herein may offer a sustainable and effective means of reducing NoV transmission on fomites.

4. Conclusion

The virucidal efficacy of light-activated fluorinated TiO2 surface coatings on human norovirus and several surrogates (bacteriophage MS2, FCV, and MNV) were investigated. The data herein clearly suggest that the catalytic enhancement seen upon fluorination is of a magnitude large enough to render F-TiO2 effective in destroying viruses even under residual UVA emitted by fluorescent lighting.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Christine Moe for providing the Norwalk virus (GI.1) stool sample. This work was partly supported by the Korean National Research Foundation (Korean Ministry of Education, Science and Technology, Award NRF-2011-35B-D00020), the grant (14162MFDS973) from Ministry of Food and Drug Safety, Korea and Hwaseung T&C Co. in Korea. All authors report having no conflicts of interest.

References

- [1].Glass RI, Parashar UD, Estes MK, Norovirus gastroenteritis, New Engl. J. Med 361 (2009) 1776–1785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Kukkula M, Maunula L, Silvennoinen E, von Bonsdorff CH, Outbreak of viral gastroenteritis due to drinking water contaminated by Norwalk-like viruses, J. Infect. Dis 180 (1999) 1771–1776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Malek M, Barzilay E, Kramer A, Camp B, Jaykus LA, Escudero-Abarca B, Derrick G, White P, Gerba C, Higgins C, Outbreak of norovirus infection among river rafters associated with packaged delicatessen meat, Grand Canyon, Clin. Infect. Dis 48 (2009) (2005) 31–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Weinstein RA, Said MA, Perl TM, Sears CL, Gastrointestinal flu: norovirus in health care and long-term care facilities, Clin. Infect. Dis 47 (2008) 1202–1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Lopman B, Gastañaduy P, Park GW, Hall AJ, Parashar UD, Vinjé J, Environmental transmission of norovirus gastroenteritis, Curr. Opin. Virol 2 (2012) 96–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Teunis PF, Moe CL, Liu P, Miller SE, Lindesmith L, Baric RS, Le Pendu J, Calderon RL, Norwalk virus: how infectious is it?, J Med. Virol 80 (2008) 1468–1476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Cheesbrough JS, BarkessJones L, Brown DW, Possible prolonged environmental survival of small round structured viruses, J. Hosp. Infect 35 (1997) 325–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Hall AJ, Vinjé J, Lopman B, Park GW, Yen C, Gregoricus N, Parashar U, Updated norovirus outbreak management and disease prevention guidelines, MMWR Recom. Rep 60 (2011) 1–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Sattar SA, Promises and pitfalls of recent advances in chemical means of preventing the spread of nosocomial infections by environmental surfaces, Am. J. Infect. Control 38 (2010) S34–S40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Weber DJ, Rutala WA, Self-disinfecting surfaces, Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol 33 (2012) 10–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Kumar A, Vemula PK, Ajayan PM, John G, Silver-nanoparticle-embedded antimicrobial paints based on vegetable oil, Nat. Mater 7 (2008) 236–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Karpanen TJ, Casey A, Lambert PA, Cookson B, Nightingale P, Miruszenko L, Elliott TS, The antimicrobial efficacy of copper alloy furnishing in the clinical environment: a crossover study, Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol 33 (2012) 3–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Rai S, Hirsch BE, Attaway HH, Nadan R, Fairey S, Hardy J, Miller G, Armellino D, Moran WR, Sharpe P, Evaluation of the antimicrobial properties of copper surfaces in an outpatient infectious disease practice, Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol 33 (2012) 200–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Salgado CD, Sepkowitz KA, John JF, Cantey JR, Attaway HH, Freeman KD, Sharpe PA, Michels HT, Schmidt MG, Copper surfaces reduce the rate of healthcare-acquired infections in the intensive care unit, Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol 34 (2013) 479–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Murata H, Koepsel RR, Matyjaszewski K, Russell AJ, Permanent, non-leaching antibacterial surfaces—2: how high density cationic surfaces kill bacterial cells, Biomaterials 28 (2007) 4870–4879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Kalyon BD, Olgun U, Antibacterial efficacy of triclosan-incorporated polymers, Am. J. Infect. Control. 29 (2001) 124–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Dawson LF, Valiente E, Donahue EH, Birchenough G, Wren BW, Hypervirulent clostridium difficile PCR-ribotypes exhibit resistance to widely used disinfectants, PLoS ONE 6 (2011) e25754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Warnes SL, Keevil CW, Inactivation of norovirus on dry copper alloy surfaces, PLoS ONE 8 (2013) e75017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Cho M, Chung H, Choi W, Yoon J, Different inactivation behaviors of MS-2 phage and Escherichia coli in TiO2 photocatalytic disinfection, Appl. Environ. Microbiol 71 (2005) 270–275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Cates EL, Chinnapongse SL, Kim J-H, Kim J-H, Engineering light: advances in wavelength conversion materials for energy and environmental technologies, Environ. Sci. Technol 46 (2012) 12316–12328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Asahi R, Morikawa T, Ohwaki T, Aoki K, Taga Y, Visible-light photocatalysis in nitrogen-doped titanium oxides, Science 293 (2001) 269–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Hong YC, Bang CU, Shin DH, Uhm HS, Band gap narrowing of TiO2 by nitrogen doping in atmospheric microwave plasma, Chem. Phys. Lett 413 (2005) 454–457. [Google Scholar]

- [23].Yu JC, Ho W, Yu J, Yip H, Wong PK, Zhao J, Efficient visible-light-induced photocatalytic disinfection on sulfur-doped nanocrystalline titania, Environ. Sci. Technol 39 (2005) 1175–1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Park JS, Choi W, Enhanced remote photocatalytic oxidation on surface-fluorinated TiO2, Langmuir 20 (2004) 11523–11527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Tang J, Quan H, Ye J, Photocatalytic properties and photoinduced hydrophilicity of surface-fluorinated TiO2, Chem. Mater 19 (2007) 116–122. [Google Scholar]

- [26].Park H, Choi W, Effects of TiO2 surface fluorination on photocatalytic reactions and photoelectrochemical behaviors, J. Phys. Chem. B 108 (2004) 4086–4093. [Google Scholar]

- [27].Minero C, Mariella G, Maurino V, Pelizzetti E, Photocatalytic transformation of organic compounds in the presence of inorganic anions. 1. Hydroxyl-mediated and direct electron-transfer reactions of phenol on a titanium dioxide-fluoride system, Langmuir 16 (2000) 2632–2641. [Google Scholar]

- [28].Kim H, Choi W, Effects of surface fluorination of TiO2 on photocatalytic oxidation of gaseous acetaldehyde, Appl. Catal. B-Environ 69 (2007) 127–132. [Google Scholar]

- [29].Park GW, Boston DM, Kase JA, Sampson MN, Sobsey MD, Evaluation of liquid-and fog-based application of Sterilox hypochlorous acid solution for surface inactivation of human norovirus, Appl. Environ. Microbiol 73 (2007) 4463–4468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Park GW, Barclay L, Macinga D, Charbonneau D, Pettigrew CA, Vinje J, Comparative efficacy of seven hand sanitizers against murine norovirus, feline calicivirus, and GII. 4 norovirus, J. Food Prot 73 (2010) 2232–2238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Friedman SD, Cooper EM, Calci KR, Genthner FJ, Design and assessment of a real time reverse transcription-PCR method to genotype single-stranded RNA male-specific coliphages (Family Leviviridae), J. Virol. Methods 173 (2011) 196–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Hill VR, Mull B, Jothikumar N, Ferdinand K, Vinjé J, Detection of GI and GII noroviruses in ground water using ultrafiltration and TaqMan real-time RT-PCR, Food Environ. Virol 2 (2010) 218–224. [Google Scholar]

- [33].Kageyama T, Kojima S, Shinohara M, Uchida K, Fukushi S, Hoshino FB, Takeda N, Katayama K, Broadly reactive and highly sensitive assay for Norwalk-like viruses based on real-time quantitative reverse transcription-PCR, J. Clin. Microbiol 41 (2003) 1548–1557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Cho M, Chung H, Choi W, Yoon J, Linear correlation between inactivation of E. coli and OH radical concentration in TiO2 photocatalytic disinfection, Water Res 38 (2004) 1069–1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Kühn KP, Chaberny IF, Massholder K, Stickler M, Benz VW, Sonntag H-G, Erdinger L, Disinfection of surfaces by photocatalytic oxidation with titanium dioxide and UVA light, Chemosphere 53 (2003) 71–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Saito T, Iwase T, Horie J, Morioka T, Mode of photocatalytic bactericidal action of powdered semiconductor TiO2 on mutans streptococci, J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 14 (1992) 369–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Janczyk A, Krakowska E, Stochel G, Macyk W, Singlet oxygen photogeneration at surface modified titanium dioxide, J. Am. Chem. Soc 128 (2006) 15574–15575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Hotze EM, Badireddy AR, Chellam S, Wiesner MR, Mechanisms of bacteriophage inactivation via singlet oxygen generation in UV illuminated fullerol suspensions, Environ. Sci. Technol 43 (2009) 6639–6645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Sano D, Pintó RM, Omura T, Bosch A, Detection of oxidative damages on viral capsid protein for evaluating structural integrity and infectivity of human norovirus, Environ. Sci. Technol 44 (2009) 808–812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]