Significance Statement

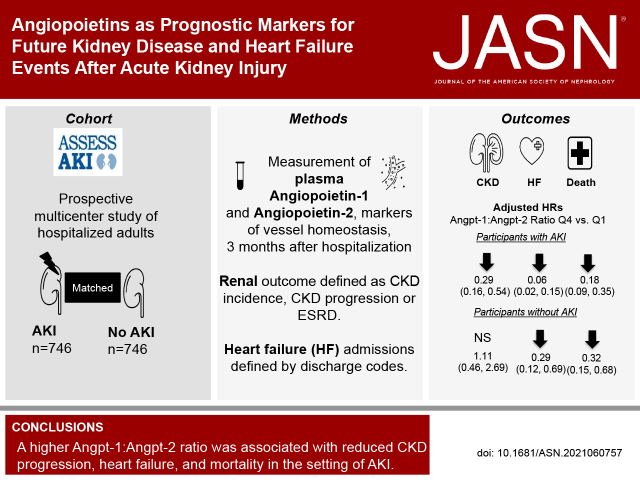

Mechanisms underlying long-term effects after AKI remain unclear. Because vessel instability is an early response to endothelial injury, the authors studied markers of blood vessel homeostasis (the plasma angiopoietins angiopoietin-1 and angiopoietin-2) in a multicenter prospective cohort that included 1503 adults, half of whom had AKI. Three months after hospitalization, the highest quartile of plasma angiopoietin-1:angiopoietin-2 ratio compared with the lowest quartile associated with 72% less risk of CKD progression, 94% less risk of heart failure, and 82% less risk of death among those with AKI; those without AKI exhibited similar but less pronounced reductions in risk of heart failure and mortality. Angiopoietins may serve as a common pathway to explain the progression of kidney and heart disease after AKI and may point to potential future interventions.

Keywords: angiopoietin-1, angiopoietin-2, acute kidney injury, chronic kidney disease, heart failure, mortality

Visual Abstract

Abstract

Background

The mechanisms underlying long-term sequelae after AKI remain unclear. Vessel instability, an early response to endothelial injury, may reflect a shared mechanism and early trigger for CKD and heart failure.

Methods

To investigate whether plasma angiopoietins, markers of vessel homeostasis, are associated with CKD progression and heart failure admissions after hospitalization in patients with and without AKI, we conducted a prospective cohort study to analyze the balance between angiopoietin-1 (Angpt-1), which maintains vessel stability, and angiopoietin-2 (Angpt-2), which increases vessel destabilization. Three months after discharge, we evaluated the associations between angiopoietins and development of the primary outcomes of CKD progression and heart failure and the secondary outcome of all-cause mortality 3 months after discharge or later.

Results

Median age for the 1503 participants was 65.8 years; 746 (50%) had AKI. Compared with the lowest quartile, the highest quartile of the Angpt-1:Angpt-2 ratio was associated with 72% lower risk of CKD progression (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 0.28; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.15 to 0.51), 94% lower risk of heart failure (aHR, 0.06; 95% CI, 0.02 to 0.15), and 82% lower risk of mortality (aHR, 0.18; 95% CI, 0.09 to 0.35) for those with AKI. Among those without AKI, the highest quartile of Angpt-1:Angpt-2 ratio was associated with 71% lower risk of heart failure (aHR, 0.29; 95% CI, 0.12 to 0.69) and 68% less mortality (aHR, 0.32; 95% CI, 0.15 to 0.68). There were no associations with CKD progression.

Conclusions

A higher Angpt-1:Angpt-2 ratio was strongly associated with less CKD progression, heart failure, and mortality in the setting of AKI.

AKI is a common complication across many inpatient settings and is linked to high morbidity and mortality.1,2 AKI is strongly associated with the future development of CKD, ESKD, and cardiovascular disease (CVD).3–6 Although there are common risk factors for AKI, CKD, and CVD, the link between AKI and long-term sequelae remains less understood, likely due to unclear underlying mechanisms and lack of early prognostic markers.

Studies using animal models have generally focused on the tubular epithelium to investigate the underlying mechanism behind AKI-to-CKD transition with less focus on the endothelium.7–11 Similarly, epidemiologic studies of AKI have mainly focused on markers of tubular injury and repair to explain long-term outcomes.12–15 More recently, there has been growing interest in the role of vessel repair in the transition from AKI to CKD and CVD.16–20 Studying pathways involved in vessel homeostasis and repair after AKI may allow a better understanding of the mechanisms shared between the kidney and the heart and the development of chronic sequelae in both organs.

The heart and kidneys are closely interrelated, with increased risk of heart failure (HF),21 myocardial infarction, and cardiovascular mortality in the setting of AKI.5,22 Legrand et al.23 proposed endothelial dysfunction as one of the key pathways involved in HF in the setting of AKI. Endothelial repair and vessel stability play an important role in maintaining cardiac and renal perfusion after injury.24–26 In HF, hypoxic injury promotes endothelial damage and vessel hyperpermeability, leading to cardiac myocyte apoptosis and eventual fibrosis.24,27 Similarly, in CKD, vessel destabilization increases renal peritubular capillary loss, which significantly correlates with an increase in kidney fibrosis.28–31 Vessel instability is an early response to endothelial injury that may reflect a shared mechanism and early trigger for both CKD and HF.24,25 To identify some of these early mechanisms, we studied the role of angiopoietins, markers of blood vessel homeostasis, in the primary outcomes of CKD progression and HF and the secondary outcome of all-cause mortality. We evaluated two markers in the angiopoietin family: angiopoietin-1 (Angpt-1) and angiopoietin-2 (Angpt-2). Angpt-1 maintains vascular quiescence, prevents vessel leakage, and promotes endothelial cell survival via activation of an endothelial cell receptor called Tie-2. Angpt-2 competitively inhibits the effects of Angpt-1 on Tie-2, leading to vessel instability and eventual capillary rarefaction.32,33 We aimed to evaluate the roles of angiopoietins using the Assessment Serial Evaluation and Subsequent Sequelae of Acute Kidney Injury (ASSESS-AKI) cohort,34 which enrolled patients with and without AKI who survived a hospital admission. We hypothesized that higher concentrations of Angpt-1 relative to Angpt-2 (as calculated by the Angpt-1:Angpt-2 ratio) would be associated with reductions in CKD progression, HF, and mortality with stronger associations in the setting of AKI. Given the observational nature of our study with measured and unmeasured confounding, we also set out to investigate the potential causal effect of angiopoietins on outcomes via the use of genome-wide association studies (GWASs). The purpose of this analysis was to identify variants that are associated with both angiopoietin concentrations and outcomes.

Methods

Study Participants and Outcome Definitions

This is an ancillary study from the ASSESS-AKI cohort, a multicenter, parallel, matched, prospective study of hospitalized adults with and without AKI.34,35 Participants were matched on center, preadmission CKD status, and an integrated priority score based on age, prior CVD or diabetes, preadmission eGFR, and treatment in the intensive care unit during the index hospitalization. Participants were followed from their index hospitalization for a median of 4.9 (interquartile range [IQR]: 3.6–6.0) years. We measured angiopoietins in patients enrolled from December 2009 to February 2015. We measured Angpt-1 and Angpt-2 concentrations in the plasma 3 months after hospitalization (Supplemental Figure 1) and at the time of index hospitalization (baseline level). The 3-month time point was selected based on preliminary data from a pilot case control study of 200 participants from ASSESS-AKI, which led us to hypothesize that vessel repair processes lasting months after injury may affect long-term outcomes more than at time of injury.

AKI at the index hospitalization was defined as ≥50% relative increase and/or an absolute increase ≥0.3 mg/dl in the peak inpatient serum creatinine concentration compared with outpatient, nonemergency department baseline value within 7–365 days before the index admission. During the same time period, a matched sample of hospitalized adults without AKI at the same sites were enrolled.

No AKI was defined as <20% relative increase or an absolute increase ≤0.2 mg/dl in the peak inpatient serum creatinine concentration compared with preadmission value. All patients had to have survived to the 3-month time point to be included in the study.35

We assessed the association of angiopoietins measured 3 months after hospitalization with the development of CKD progression, defined as incident CKD (without preexisting CKD at the index hospitalization, with ≥25% reduction in the eGFR from preadmission eGFR, and reaching CKD stage III or worse during follow-up), or progression of preexisting CKD (eGFR <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 at the index hospitalization with ≥50% reduction in eGFR from preadmission, or progression to CKD stage V, or development of ESKD, or receipt of a kidney transplant). HF admissions were defined by discharge codes for clinical HF and confirmed based on Framingham Heart Study clinical criteria ascertained from medical records.36 Two physicians independently adjudicated all hospitalization records for HF. CKD progression and HF were the primary outcomes. As a secondary outcome, we evaluated all-cause mortality, which was defined through surveys of participants or their proxies, review of medical records, and death certificates. Myocardial infarction events were also tracked in this study but given the small number of events we were unable to perform any analyses using this outcome.

Angpt-1 and Angpt-2 Measurements

Samples were centrifuged at 2000 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C, separated into 1-ml aliquots, and immediately stored at −80°C. Angpt-1 and Angpt-2 were measured simultaneously using the Meso Scale Discovery platform (Meso Scale Diagnostics, Gaithersburg, MD), which uses electrochemiluminescence detection combined with patterned arrays. The mean interassay coefficient of variation for Angpt-1 was 6.3% with a reportable range of 0.12–800 ng/ml. Twelve (1%) samples were below the lower limit of detection. The interassay coefficient of variation for Angpt-2 was 2.5%, with a detection range of 0.01–400 ng/ml and was determined by analyzing 5% of samples in duplicate on separate days. All laboratory personnel were blinded to the participants’ disease status and outcomes.

Cohort Genotyping

The Illumina Multi-Ethnic Global Array platform was used to genotype patients. We quality-filtered samples with a call rate <97%. We removed subjects for relatedness and subjects with genetic sex-gender discordance. We then used the single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) remaining after quality control for imputation of approximately 40 million single-nucleotide variants using the Michigan Imputation Server37 pipeline with the Haplotype Reference Consortium r1.1 2016 panel38 and Eagle v2.3 haplotype phasing.39 We included SNPs with an imputation quality r2 >0.3 and a minor allele frequency (MAF) >1% in subsequent analyses.

Statistical Analyses

Differences in clinical and demographic characteristics were evaluated by the Kruskal–Wallis test or chi-squared test for continuous or categorical variables, respectively. We divided the entire cohort into quartiles of Angpt-1, Angpt-2, and the Angpt-1:Angpt-2 ratio, and performed spline plot analysis to assess the linearity of the relationship between angiopoietins and outcomes. We used a Cox proportional hazard model to model the effects of covariates and quartiles of Angpt-1, Angpt-2, and the Angpt-1:Angpt-2 ratio (which was an a priori analysis given their known opposing physiology) on the primary outcomes of CKD progression and HF and on the secondary outcome of all-cause mortality in those with and without AKI. The proportional hazards assumption was evaluated by the Kolmogorov-type supremum test. We reported hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of the univariable and multivariable models. All inference testing was two-sided with a significance level of 0.05. Cox proportional hazard models were adjusted for the following: race, sex, age, body mass index (BMI), self-reported smoking status, self-reported history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), self-reported CVD (i.e., HF, myocardial infarction, stroke, or peripheral artery disease), self-reported diabetes, self-reported CKD, sepsis at index hospitalization, eGFR at 3-month visit after discharge (at time of biomarker measurement), urine albumin-creatinine ratio (UACR) at 3-month visit, and C-reactive protein (CRP) at 3-month visit. Additionally, we adjusted for baseline biomarker levels at index hospitalization. We also performed the analyses adjusting for Angpt-1 and Angpt-2 individually when assessing the associations between Angpt-2 and Angpt-1 and outcomes, respectively. For the outcome of HF, we performed a second multivariable model adjusting for N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) and troponin at 3-month visit. No imputations were done for missing covariates because rates of missingness were minimal and varied from 0% to 4.6% (Table 1). Because outcomes were time-to-event with right-censoring due to study withdrawal, or end of study follow-up, we did not have to account for potential missingness in the outcomes. We assessed the effect modification of AKI on the association between Angpt-1:Angpt-2 ratio and outcomes, and reported the interaction P values. We also evaluated a competing risk analysis for the outcomes of CKD progression and HF with death in those with and without AKI. Lastly, we performed a mediation analysis to assess how much of the relationship between AKI and outcomes appears to be mediated by Angpt-1 and Angpt-2.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the entire cohort and stratified by quartiles of angiopoietin ratios

| Participant Characteristics | All (n=1503) | Quartiles of Angpt-1:Angpt-2 Ratio | P value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quartile 1: Range 0.01–0.76 pg/ml (n=375) | Quartile 2: Range 0.76–1.91 pg/ml (n=376) | Quartile 3: Range 1.92–4.14 pg/ml (n=376) | Quartile 4: Range 4.23–24.46 pg/ml (n=376) | ||||

| Age, yr | 65.8 (56.6–73.9) | 67.7 (57.4–75.8) | 66.5 (57.8–73.6) | 66.15 (58.1–73.8) | 63.7 (54.2–71.9) | <0.001 | |

| Female sex | 555 (37) | 118 (31) | 141 (38) | 145 (39) | 151 (40) | 0.073 | |

| Black race | 196 (13) | 42 (11) | 51 (14) | 55 (15) | 48 (13) | 0.558 | |

| Hispanic/Latino ethnicity | 37 (2) | 7 (2) | 13 (3) | 14 (4) | 3 (1) | 0.030 | |

| Current or former smoker | 862 (57) | 250 (67) | 217 (61) | 213 (56) | 182 (49) | <0.001 | |

| Preadmission COPD | 329 (22) | 87 (23) | 90 (24) | 62 (16) | 90 (24) | 0.100 | |

| Preadmission CVD | 680 (45) | 222 (59) | 175 (47) | 161 (43) | 122 (32) | <0.001 | |

| Preadmission CKD | 594 (40) | 175 (47) | 150 (40) | 161 (43) | 108 (29) | <0.001 | |

| Preadmission diabetes | 642 (43) | 179 (48) | 172 (46) | 154 (41) | 137 (36) | 0.008 | |

| Preadmission hypertension | 1118 (74) | 285 (76) | 285 (76) | 285 (76) | 263 (70) | 0.074 | |

| Preadmission heart failure | 319 (21) | 104 (28) | 97 (26) | 76 (20) | 42 (11) | <0.001 | |

| Variables at index hospitalization | |||||||

| Sepsis | 143 (10) | 42 (11) | 37 (10) | 36 (10) | 28 (7) | 0.369 | |

| UACR, mg/g | 32.0 (12.5–88.4) | 39.7 (16.6–103.3) | 37.7 (15.6–96.2) | 28.2 (10.5–98.6) | 21.0 (10–59.2) | <0.001 | |

| AKI | 746 (50) | 213 (57) | 199 (53) | 174 (46) | 160 (43) | <0.001 | |

| AKI stage | No AKI | 757 (50) | 162 (43) | 177 (47) | 202 (54) | 216 (57) | 0.013 |

| Stage 1 | 539 (36) | 151 (40) | 143 (38) | 128 (34) | 117 (31) | ||

| Stage 2 | 114 (8) | 32 (9) | 34 (9) | 27 (7) | 21 (6) | ||

| Stage 3 | 93 (6) | 30 (8) | 22 (6) | 19 (5) | 22 (6) | ||

| Creatinine, mg/dl | 1.4 (1.0–2.0) | 1.5 (1.2–2.2) | 1.4 (1.0–2.1) | 1.3 (1.0–1.9) | 1.2 (0.9–1.7) | <0.001 | |

| CRP, mg/L | 100 (30.2–197.6) | 113.7 (40.1–210.5) | 110.9 (35.1–206.4) | 82.7 (18.7–183.2) | 87.5 (25.0–167.4) | 0.002 | |

| NT-proBNP, pg/ml | 1191 (351–3157) | 2397 (973–4576) | 1364.5 (504–3345) | 995.5 (281–2718) | 568 (202–1486) | <0.001 | |

| Troponin, ng/ml | 31.6 (13.6–203.6) | 86.3 (22.2–359.4) | 39 (15.3–251.2) | 26.9 (13.0–134.6) | 17.9 (10.5–54.2) | <0.001 | |

| Variables at 3-month visit after hospitalization | |||||||

| BMI, kg/m2 | 29.7 (25.8–35) | 29.7 (26–35.2) | 29.9 (26.1–35.8) | 29.6 (25.2–35.4) | 29.6 (25.9–34.1) | 0.607 | |

| UACR, mg/g | 14.4 (6.7–59.3) | 20 (8.3–110.1) | 18.3 (8.1–89.7) | 12.2 (6.25–44.1) | 10.0 (5.4–27.8) | <0.001 | |

| Creatinine, mg/dl | 1.0 (0.8–1.3) | 1.2 (0.9–1.5) | 1.0 (0.9–1.4) | 1.0 (0.9–1.3) | 1.0 (0.8–1.2) | <0.001 | |

| eGFR, ml/min per 1.73 m2 | 68.2 (50.2–89.1) | 60.2 (44.1–82.6) | 67.1 (49.6–89.4) | 68.1 (51.6–87.4) | 77.6 (60.1–93.1) | <0.001 | |

| CRP, mg/L | 3.6 (1.5–7.6) | 4.6 (2.2–9.8) | 3.6 (1.7–7.4) | 3.1 (1.2–7.3) | 3.2 (1.2–7) | <0.001 | |

| NT-proBNP, pg/ml | 290 (88–902) | 643 (217.5–1997) | 390 (114.5–1031.5) | 250 (96–708) | 125 (45–329) | <0.001 | |

| Troponin, ng/ml | 16.9 (10.4–28.7) | 20.8 (13.2–36.8) | 18.9 (10.9–30.1) | 16.8 (10.5–26.3) | 12.4 (7.9–20.8) | <0.001 | |

Results are presented as median (IQR) or count (percentage). At baseline, there were 12 participants with missing smoking status, 4 with missing COPD status, 3 with missing CVD status, 2 with missing hypertension status, 1 with missing heart failure status, 10 with missing UACR values, 59 with missing CRP values, 18 with missing NT-proBNP values, and 61 with missing troponin values. At 3 months, there were 2 patients with missing BMI values, 2 with missing UACR values, 22 with missing CRP values, 65 with missing NT-proBNP values, and 70 with missing troponin values.

Furthermore, we used a GWAS to identify genetic variants associated with Angpt-1 and Angpt-2 concentrations. We performed linear regressions with PLINK v1.90b2m40 using an additive genetic model with the common (MAF>0.01) imputed SNPs while adjusting for age, sex, center, and ancestry with 10 principal components (PCs). SNPs with Hardy Weinberg Equilibrium (HWE) P values <10−6 in the European ancestry subset of subjects were excluded. GWAS variants that were identified as significant (P<5 × 10−8) were subsequently analyzed with Cox proportional hazard models to model the effects of covariates and SNPs associated with angiopoietin concentrations on the primary and secondary outcomes. Cox proportional hazard models were adjusted for age, sex, center, and genomic variant PCs.

Lastly, we performed a mediation analysis to determine if angiopoietins explained a portion of the association between the GWAS variants identified and outcomes. Cox proportional hazard regression models were fit for the outcomes with the identified SNPs alone and with the SNPs and angiopoietins. We calculated the proportion of the effect explained by angiopoietins based on the change to the SNP regression coefficient after adding angiopoietin to the Cox regression model (SAS MEDIATE macro).41

Results

Baseline Characteristics of Participants

This study included 1503 participants with a median age of 65.8 (IQR: 57–74) years; 948 (63%) were men, and 196 (13%) were Black. Participants in higher Angpt-1:Angpt-2 ratio quartiles at 3 months were significantly younger in age, less likely to have preadmission CKD, CVD, diabetes, and HF, and less likely to have lower serum creatinine concentrations, UACR, and NT-proBNP and troponin concentrations at index hospitalization and 3 months after hospitalization (Table 1). Additionally, there was significantly less AKI in the highest quartile of Angpt-1:Angpt-2 ratio, and a similar pattern persisted with stages of AKI, with less stage 1 and stage 2 AKI among patients with higher quartiles of Angpt-1:Angpt-2 ratios. Baseline characteristics were similar when stratifying by quartiles of change in angiopoietin levels from baseline to 3-month visit (Supplemental Tables 1 and 2).

Angiopoietin Concentrations in Participants with and without AKI

The overall median concentrations of angiopoietins at 3 months in all participants (n=1503) were 4858 (IQR: 2201–8885) pg/ml for Angpt-1, 2217 (IQR: 1618–3381) pg/ml for Angpt-2, and 1.92 (IQR: 0.76–4.21) for Angpt-1:Angpt-2 ratio. Among those with AKI (n=746), Angpt-2 concentrations were significantly higher compared with those without, whereas Angpt-1:Angpt-2 ratios were significantly lower in participants with AKI compared with those without (Supplemental Table 3).

Associations between Angiopoietins and CKD Progression in Participants with AKI

The median time to CKD progression was 2.1 (IQR: 1.1–4.0) years. Among the 746 participants with AKI, 201 (27%) developed CKD progression after the measurement of angiopoietins 3 months after hospitalization, with 133 (66%) developing incident CKD, and 68 (34%) experiencing progression of preexisting CKD. Among those with CKD progression, Angpt-2 concentrations were higher and the ratio of Angpt-1:Angpt-2 was lower compared with those without CKD progression (Supplemental Table 3).

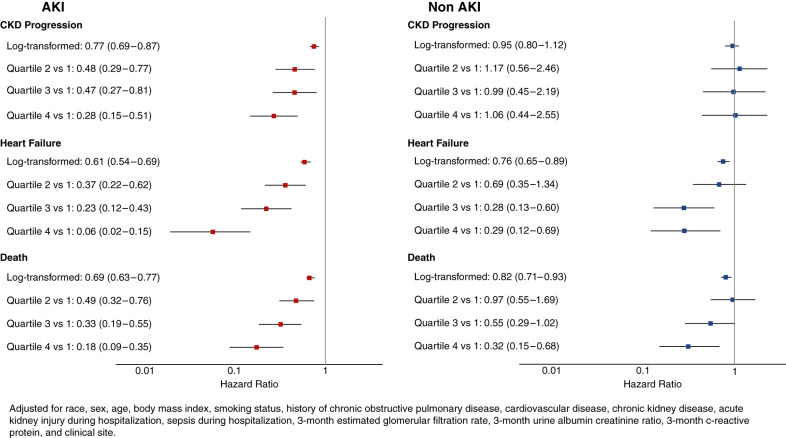

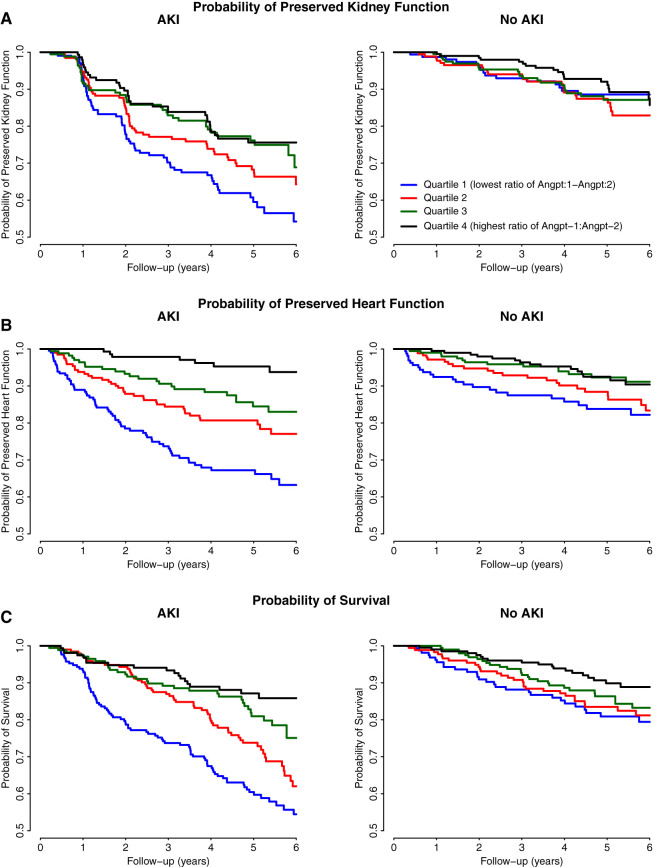

Compared with the lowest quartile (1st quartile), the highest quartile (4th quartile) of Angpt-1 was associated with a 55% lower risk of CKD progression, whereas the highest quartile of Angpt-2 was associated with approximately three times greater risk of CKD progression (Table 2). Compared with the lowest quartile, the highest quartile of Angpt-1:Angpt-2 ratio was associated with a 72% lower risk of CKD progression (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR]: 0.28; 95% CI, 0.15 to 0.51) (Figure 1). Overall, a higher Angpt-1:Angpt-2 ratio measured 3 months after hospitalization in patients with AKI was associated with a lower probability of future CKD progression over time (Figure 2). After adjusting for baseline angiopoietin levels, similar associations were identified (Table 2). Furthermore, when evaluating the associations of Angpt-1 with CKD progression while adjusting for Angpt-2 and vice versa similar associations were identified as those identified by the ratio. Spline plots of angiopoietins and the outcome of CKD showed a nonlinear relationship among those with and without AKI (Supplemental Figure 2).

Table 2.

Associations between angiopoietin quartiles and CKD progression

| Angiopoietins | Range (pg/ml) | Number of Events (%) | Mean (95% CI) Event Rate per 1000 PY | Unadjusted HR (95% CI) | Model 1: Adjusted HR (95% CI) | Model 2: Adjusted HR (95% CI) | Model 3: Adjusted HR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participants with AKI | |||||||

| Angpt-1 | |||||||

| Log2-transformed | 6.94–15.03 | 201/746 (27%) | 73 (63.6 to 83.8) | 0.96 (0.88 to 1.05) | 0.82 (0.71 to 0.95) | 0.83 (0.72 to 0.96) | 0.85 (0.73 to 0.99) |

| 1st quartile | 122.4–2186.9 | 56/187 (30%) | 83.9 (64.9 to 108.5) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) |

| 2nd quartile | 206.8–4841.3 | 49/194 (25%) | 68.3 (51.6 to 90.4) | 0.84 (0.57 to 1.23) | 0.68 (0.4 to 1.15) | 0.69 (0.41 to 1.18) | 0.72 (0.42 to 1.22) |

| 3rd quartile | 857.9–8823.3 | 51/190 (27%) | 71.2 (54.2 to 93.4) | 0.86 (0.59 to 1.27) | 0.59 (0.33 to 1.05) | 0.62 (0.35 to 1.1) | 0.66 (0.36 to 1.2) |

| 4th quartile | 925.1–33,501.3 | 42/161 (26%) | 68.3 (50.5 to 92.4) | 0.84 (0.56 to 1.25) | 0.45 (0.24 to 0.84) | 0.5 (0.27 to 0.92) | 0.52 (0.27 to 1) |

| Angpt-2 | |||||||

| Log2-transformed | 8.52–15.57 | 201/746 (27%) | 73 (63.6 to 83.8) | 1.54 (1.34 to 1.77) | 1.53 (1.25 to 1.86) | 1.5 (1.23 to 1.83) | 1.71 (1.31 to 2.22) |

| 1st quartile | 367.2–1614.9 | 26/144 (18%) | 42.4 (28.9 to 62.3) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) |

| 2nd quartile | 617.8–2216 | 35/170 (21%) | 48.2 (34.6 to 67.1) | 1.13 (0.67 to 1.88) | 1.38 (0.74 to 2.56) | 1.27 (0.68 to 2.35) | 1.49 (0.79 to 2.8) |

| 3rd quartile | 218.1–3372.5 | 54/190 (28%) | 73.9 (56.8 to 96.3) | 1.76 (1.1 to 2.83) | 1.50 (0.82 to 2.73) | 1.34 (0.73 to 2.46) | 1.68 (0.89 to 3.16) |

| 4th quartile | 381.7–48,651.1 | 83/228 (36%) | 126.7 (102.4 to 156.7) | 3.05 (1.95 to 4.79) | 3.06 (1.7 to 5.52) | 2.73 (1.5 to 4.95) | 3.96 (1.99 to 7.89) |

| Angpt-1:Angpt-2 ratio | |||||||

| Log2-transformed | −6.06–4.61 | 201/746 (27%) | 73 (63.6 to 83.8) | 0.87 (0.81 to 0.93) | 0.77 (0.69 to 0.87) | 0.79 (0.69 to 0.89) | |

| 1st quartile | 0.01–0.76 | 70/213 (33%) | 102.8 (81.4 to 130) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | |

| 2nd quartile | 0.76–1.91 | 58/199 (29%) | 76.1 (58.9 to 98.5) | 0.74 (0.52 to 1.06) | 0.49 (0.3 to 0.79) | 0.51 (0.31 to 0.84) | |

| 3rd quartile | 1.92–4.14 | 38/174 (22%) | 56.5 (41.1 to 77.6) | 0.56 (0.37 to 0.83) | 0.48 (0.28 to 0.84) | 0.52 (0.29 to 0.94) | |

| 4th quartile | 4.23–24.46 | 35/160 (22%) | 54.8 (39.3 to 76.3) | 0.53 (0.35 to 0.81) | 0.29 (0.16 to 0.54) | 0.34 (0.17 to 0.67) | |

| Participants without AKI | |||||||

| Angpt-1 | |||||||

| Log2-transformed | 6.94–15.14 | 92/757 (12%) | 26.8 (2.19 to 32.9) | 1.04 (0.91 to 1.18) | 1.01 (0.83 to 1.23) | 1.01 (0.82 to 1.23) | 1 (0.81 to 1.24) |

| 1st quartile | 122.4–2151.4 | 17/186 (9%) | 19.4 (12.1 to 31.3) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) |

| 2nd quartile | 2201.1–4848.8 | 35/179 (20%) | 44.7 (32.1 to 62.2) | 2.43 (1.36 to 4.34) | 1.73 (0.85 to 3.55) | 1.62 (0.79 to 3.36) | 1.68 (0.81 to 3.49) |

| 3rd quartile | 4867.9–8881.8 | 19/181 (10%) | 23.5 (15 to 36.9) | 1.36 (0.7 to 2.62) | 0.95 (0.4 to 2.27) | 0.92 (0.38 to 2.2) | 0.96 (0.39 to 2.32) |

| 4th quartile | 8885–36,044.5 | 21/211 (10%) | 21.8 (14.2 to 33.5) | 1.27 (0.67 to 2.42) | 0.80 (0.32 to 1.97) | 0.78 (0.31 to 1.94) | 0.82 (0.31 to 2.15) |

| Angpt-2 | |||||||

| Log2-transformed | 9.23–14.65 | 92/757 (12%) | 26.8 (2.19 to 32.9) | 1.41 (1.1 to 1.81) | 1.29 (0.93 to 1.8) | 1.26 (0.9 to 1.77) | 1.18 (0.76 to 1.85) |

| 1st quartile | 602.1–1613 | 19/229 (8%) | 17.4 (11.1 to 27.2) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) |

| 2nd quartile | 1619.5–2211.4 | 29/205 (14%) | 29.7 (20.6 to 42.7) | 1.67 (0.92 to 3.03) | 1.39 (0.68 to 2.83) | 1.31 (0.64 to 2.69) | 1.34 (0.65 to 2.79) |

| 3rd quartile | 2216.7–3365.7 | 21/181 (12%) | 27.5 (17.9 to 42.2) | 1.66 (0.88 to 3.14) | 1.34 (0.61 to 2.93) | 1.28 (0.58 to 2.8) | 1.27 (0.54 to 2.97) |

| 4th quartile | 3381–25,721 | 23/142 (16%) | 38.7 (25.7 to 58.3) | 2.35 (1.26 to 4.41) | 1.48 (0.67 to 3.28) | 1.34 (0.6 to 2.99) | 1.33 (0.51 to 3.47) |

| Angpt-1:Angpt-2 ratio | |||||||

| Log2-transformed | −5.53–4.84 | 92/757 (12%) | 26.8 (21.9 to 32.9) | 0.96 (0.85 to 1.08) | 0.95 (0.8 to 1.12) | 0.96 (0.8 to 1.16) | |

| 1st quartile | 0.02–0.73 | 17/162 (10%) | 23.8 (14.8 to 38.4) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | |

| 2nd quartile | 0.76–1.92 | 28/177 (16%) | 34.3 (23.7 to 49.7) | 1.45 (0.79 to 2.69) | 1.15 (0.54 to 2.41) | 1.22 (0.57 to 2.61) | |

| 3rd quartile | 1.92–4.21 | 25/202 (12%) | 27.4 (18.5 to 40.6) | 1.2 (0.64 to 2.25) | 0.94 (0.42 to 2.1) | 1.05 (0.45 to 2.46) | |

| 4th quartile | 4.21–28.66 | 22/216 (10%) | 22.3 (14.7 to 33.9) | 1.02 (0.53 to 1.94) | 1.11 (0.46 to 2.69) | 1.28 (0.49 to 3.32) | |

Log-transformed biomarkers can be interpreted as per doubling of biomarker. Model 1: adjusted for race, sex, age, BMI, smoking status, history of COPD, diabetes, CVD, CKD, sepsis during hospitalization, 3-month eGFR, 3-month UACR, 3-month CRP, and clinical site. Model 2: Model 1 plus Angpt-2 (for the exposure variable Angpt-1) and Angpt-1 (for the exposure variable Angpt-2). Model 3: Model 1 plus baseline angiopoietin levels at the time of hospitalization. PY, patient-year; ref, reference.

Figure 1.

Associations between the Angpt-1:Angpt-2 ratio and outcomes stratified by AKI status. AKI status significantly modifies the association between the Angpt-1:Angpt-2 ratio and the outcomes of heart failure (interaction P=0.01) and death (P=0.04). The interaction P value for CKD progression was P=0.20.

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier curves of the relationship between angiopoietin ratio quartiles and outcomes stratified by AKI. The Kaplan–Meier curves show a reduction in CKD progression (A), heart failure (B), and death (C) over time with increasing Angpt-1:Angpt-2 ratio quartiles in those with AKI more so than those without AKI.

Associations between Angiopoietins and HF in Participants with AKI

The median time to HF was 4.5 (IQR: 2.4–5.6) years. Among participants with AKI, 134 (18%) developed HF. Angpt-1 concentrations were lower and Angpt-2 concentrations were higher in those who developed HF compared with those who did not (Supplemental Table 3). The ratio of Angpt-1:Angpt-2 was lower in those who developed HF compared with those who did not.

Compared with the lowest quartile, the highest quartile of Angpt-1 was associated with a 71% less risk of developing HF (Table 3). In contrast, the highest quartile of Angpt-2 was associated with about 10 times the risk of developing HF. Furthermore, compared with the lowest quartile, the highest quartile of the Angpt-1:Angpt-2 ratio was associated with a 94% less risk of developing HF (aHR: 0.06; 95% CI, 0.02 to 0.15) (Figure 1). The associations of Angpt-1, Angpt-2, and the Angpt-1:Angpt-2 ratio with HF remained significant after the addition of NT-proBNP and troponin to the multivariable model (Table 3). A higher Angpt-1:Angpt-2 ratio measured 3 months after hospitalization in patients with AKI was associated with lower probability of future HF events over time (Figure 2). After adjusting for baseline angiopoietin levels, similar associations were identified (Table 3). Furthermore, when evaluating the associations of Angpt-1 with HF while adjusting for Angpt-2 and vice versa similar associations were identified as those identified by the ratio. Spline plots of angiopoietins and the outcome of HF showed a nonlinear relationship among those with and without AKI (Supplemental Figure 2).

Table 3.

Associations between angiopoietin quartiles and heart failure

| Angiopoietins | Number of Events (%) | Mean (95% CI) Event Rate per 1000 PY | Unadjusted HR (95% CI) | Model 1: Adjusted HR (95% CI) | Model 2: Adjusted HR (95% CI) | Model 3: Adjusted HR (95% CI) | Model 4: Adjusted HR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participants with AKI | |||||||

| Angpt-1 | |||||||

| Log2-transformed | 134/746 (18%) | 44.6 (37.7 to 52.9) | 0.84 (0.76 to 0.93) | 0.73 (0.62 to 0.86) | 0.77 (0.65 to 0.91) | 0.78 (0.66 to 0.92) | 0.8 (0.67 to 0.95) |

| 1st quartile | 46/189 (24%) | 61.4 (46 to 82) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) |

| 2nd quartile | 40/197 (20%) | 51.7 (37.9 to 70.5) | 0.85 (0.55 to 1.31) | 0.77 (0.45 to 1.33) | 0.87 (0.49 to 1.54) | 0.95 (0.53 to 1.7) | 0.9 (0.5 to 1.6) |

| 3rd quartile | 27/195 (14%) | 33.5 (23 to 48.8) | 0.54 (0.33 to 0.87) | 0.37 (0.19 to 0.72) | 0.39 (0.2 to 0.79) | 0.39 (0.2 to 0.79) | 0.44 (0.21 to 0.89) |

| 4th quartile | 21/165 (13%) | 31.2 (20.3 to 47.8) | 0.5 (0.3 to 0.86) | 0.29 (0.14 to 0.6) | 0.35 (0.16 to 0.74) | 0.38 (0.18 to 0.82) | 0.4 (0.18 to 0.87) |

| Angpt-2 | |||||||

| Log2-transformed | 134/746 (18%) | 44.6 (37.7 to 52.9) | 2.42 (2.03 to 2.88) | 2.4 (1.95 to 2.96) | 2.19 (1.73 to 2.78) | 2.16 (1.71 to 2.73) | 2.42 (1.78 to 3.29) |

| 1st quartile | 6/146 (4%) | 8.8 (3.9 to 19.5) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) |

| 2nd quartile | 18/171 (11%) | 22.9 (14.4 to 36.3) | 2.63 (1.03 to 6.71) | 2.44 (0.92 to 6.43) | 2.59 (0.9 to 7.45) | 2.41 (0.84 to 6.94) | 2.53 (0.87 to 7.35) |

| 3rd quartile | 30/195 (15%) | 37.3 (26.1 to 53.4) | 4.37 (1.79 to 10.66) | 3.56 (1.4 to 9.04) | 3.6 (1.3 to 9.95) | 3.28 (1.19 to 9.1) | 3.49 (1.23 to 9.86) |

| 4th quartile | 80/234 (34%) | 109.9 (88.2 to 136.8) | 13.22 (5.67 to 30.8) | 10.17 (4.12 to 25.13) | 9.35 (3.45 to 25.39) | 8.8 (3.24 to 23.87) | 8.63 (2.95 to 25.28) |

| Angpt-1:Angpt-2 ratio | |||||||

| Log2-transformed | 134/746 (18%) | 44.6 (37.7 to 52.9) | 0.7 (0.64 to 0.76) | 0.61 (0.54 to 0.69) | 0.66 (0.57 to 0.75) | 0.68 (0.58 to 0.79) | |

| 1st quartile | 65/213 (31%) | 88 (69 to 112.3) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | |

| 2nd quartile | 38/199 (19%) | 46.4 (33.8 to 63.7) | 0.51 (0.34 to 0.78) | 0.37 (0.22 to 0.62) | 0.41 (0.23 to 0.71) | 0.43 (0.25 to 0.76) | |

| 3rd quartile | 24/174 (14%) | 32.7 (21.9 to 48.8) | 0.36 (0.22 to 0.58) | 0.23 (0.12 to 0.43) | 0.32 (0.16 to 0.61) | 0.36 (0.18 to 0.72) | |

| 4th quartile | 7/160 (4%) | 9.8 (4.7 to 20.6) | 0.11 (0.05 to 0.24) | 0.06 (0.02 to 0.15) | 0.09 (0.03 to 0.23) | 0.11 (0.04 to 0.32) | |

| Participants without AKI | |||||||

| Angpt-1 | |||||||

| Log2-transformed | 77/757 (10%) | 22.3 (17.9 to 27.9) | 1.03 (0.89 to 1.19) | 0.96 (0.79 to 1.16) | 1.01 (0.81 to 1.26) | 1.02 (0.82 to 1.27) | 1.04 (0.82 to 1.31) |

| 1st quartile | 14/186 (8%) | 15.7 (9.3 to 26.5) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) |

| 2nd quartile | 27/179 (15%) | 34 (23.3 to 49.6) | 2.17 (1.13 to 4.15) | 1.99 (0.96 to 4.15) | 2.95 (1.28 to 6.76) | 1.91 (0.9 to 4.05) | 2.99 (1.29 to 6.93) |

| 3rd quartile | 18/181 (10%) | 22.5 (14.2 to 35.8) | 1.44 (0.71 to 2.92) | 0.94 (0.4 to 2.17) | 1.47 (0.58 to 3.78) | 0.91 (0.39 to 2.13) | 1.48 (0.57 to 3.87) |

| 4th quartile | 18/211 (9%) | 18.7 (11.8 to 29.6) | 1.2 (0.59 to 2.42) | 0.82 (0.33 to 2.02) | 1.17 (0.43 to 3.2) | 0.8 (0.32 to 1.97) | 1.24 (0.43 to 3.61) |

| Angpt-2 | |||||||

| Log2-transformed | 77/757 (10%) | 22.3 (17.9 to 27.9) | 2.61 (2.02 to 3.37) | 2.48 (1.83 to 3.36) | 1.57 (1.07 to 2.3) | 1.58 (1.08 to 2.32) | 1.66 (1.02 to 2.69) |

| 1st quartile | 9/229 (4%) | 8.1 (4.2 to 15.5) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) |

| 2nd quartile | 15/205 (7%) | 14.9 (9 to 24.7) | 1.84 (0.79 to 4.28) | 1.25 (0.51 to 3.1) | 1.22 (0.48 to 3.12) | 1.23 (0.5 to 3.04) | 1.25 (0.49 to 3.22) |

| 3rd quartile | 22/181 (12%) | 28.5 (18.7 to 43.2) | 3.63 (1.63 to 8.06) | 2.08 (0.86 to 5.01) | 1.85 (0.75 to 4.6) | 2.11 (0.88 to 5.1) | 1.95 (0.75 to 5.07) |

| 4th quartile | 31/142 (22%) | 56.1 (39.5 to 79.8) | 7.7 (3.56 to 16.65) | 5.49 (2.34 to 12.86) | 2.72 (1.06 to 6.98) | 5.45 (2.33 to 12.8) | 2.95 (1.02 to 8.55) |

| Angpt-1:Angpt-2 ratio | |||||||

| Log2-transformed | 77/757 (10%) | 22.3 (17.9 to 27.9) | 0.83 (0.73 to 0.93) | 0.76 (0.65 to 0.89) | 0.91 (0.76 to 1.09) | 0.94 (0.77 to 1.14) | |

| 1st quartile | 24/162 (15%) | 34.5 (23.1 to 51.5) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | |

| 2nd quartile | 23/177 (13%) | 27.9 (18.6 to 42) | 0.79 (0.44 to 1.43) | 0.69 (0.35 to 1.34) | 1.08 (0.51 to 2.27) | 1.1 (0.51 to 2.34) | |

| 3rd quartile | 15/202 (7%) | 16.1 (9.7 to 26.6) | 0.45 (0.23 to 0.88) | 0.28 (0.13 to 0.6) | 0.38 (0.16 to 0.9) | 0.4 (0.17 to 0.97) | |

| 4th quartile | 15/216 (7%) | 15 (9.1 to 24.9) | 0.42 (0.22 to 0.82) | 0.29 (0.12 to 0.69) | 0.5 (0.19 to 1.32) | 0.54 (0.19 to 1.52) | |

Model 1: adjusted for race, sex, age, BMI, smoking status, history of COPD, diabetes, CVD, CKD, sepsis during hospitalization, 3-month eGFR, 3-month UACR, 3-month CRP, and clinical site. Model 2: Model 1 plus NT-proBNP and troponin. Model 3: Model 2 plus Angpt-2 (for the exposure variable Angpt-1) and Angpt-1 (for the exposure variable Angpt-2). Model 4: Model 2 plus baseline angiopoietin levels. PY, patient-year; ref, reference.

Associations between Angiopoietins and All-Cause Mortality in Participants with AKI

The median time to death was 4.9 (IQR: 3.3–5.8) years. Among those with AKI, a total of 203 (27%) participants died. Angpt-1 concentrations were significantly lower and Angpt-2 concentrations were higher in those who died compared with those who did not (Supplemental Table 3). The ratio of Angpt-1:Angpt-2 was lower in those who died compared with those who did not.

The highest quartile of Angpt-1 was associated with 40% less risk of death, whereas the highest quartile of Angpt-2 was associated with about 5.5 times the risk of death (Supplemental Table 4). The highest quartile of Angpt-1:Angpt-2 ratio was associated with 82% less death (aHR: 0.18; 95% CI, 0.09 to 0.35) than the lowest quartile (Figure 1). A higher Angpt-1:Angpt-2 ratio 3 months after hospitalization in patients with AKI was associated with a lower probability of death over time (Figure 2). After adjusting for baseline angiopoietin levels, similar associations were identified (Supplemental Table 4). Furthermore, when evaluating the associations of Angpt-1 with mortality while adjusting for Angpt-2 and vice versa similar associations were identified as those identified by the ratio. Spline plots of angiopoietins and the outcome of mortality showed a nonlinear relationship among those with and without AKI (Supplemental Figure 2).

Relationship between Angiopoietins and Outcomes in Participants without AKI

Angiopoietins had no significant associations with CKD progression in participants without AKI (Figure 1). For the outcome of HF, the associations with angiopoietins in those without AKI were significant but lower than in participants with AKI, where the highest quartile of Angpt-1:Angpt-2 ratio was associated with 71% less risk of HF (aHR: 0.29; 95% CI, 0.12 to 0.69). Similarly, among those without AKI, angiopoietins had significant but lower associations with the outcome of mortality compared with those with AKI, where the highest quartile of Angpt-1:Angpt-2 ratio was associated with 68% less risk of death (aHR: 0.32; 95% CI, 0.15 to 0.68). Interaction P values of AKI and Angpt-1:Angpt-2 ratio were P=0.01 for HF, P=0.04 for mortality, and P=0.20 for CKD progression.

Competing Risk Analysis for the Outcomes of CKD Progression and HF with Death

In competing risk analysis, the association between Angpt-1:Angpt-2 ratio and CKD progression was attenuated but remained significant (Supplemental Table 5). In contrast, the associations between the quartiles of the Angpt-1:Angpt-2 ratio and CKD progression were not statistically significant.

When evaluating the outcome of HF, both log-transformed and quartiles of the Angpt-1:Angpt-2 ratio remained significant but the strength of the association was attenuated (Supplemental Table 6).

Mediation Analysis in Participants with AKI

In this mediation analysis, Angpt-1 did not significantly mediate the relationship between AKI and any of the outcomes (Supplemental Table 7), but the addition of Angpt-2 substantially explained the relationship between AKI and all three outcomes of CKD progression, HF, and death (9.2%, 42.2%, and 30.1%, respectively).

Associations between a GWAS Variant and Outcomes

Of the 1503 patients, 1290 had genotyping and angiopoietin data available. We analyzed 8,871,257 variants in regression analysis. The lambda was 1.024 indicating little residual population stratification. We identified one SNP meeting genome-wide significance (rs611475, chr11:117950796 (hg19), T>C, P=3.2 × 10−8, Beta=0.26 (95% CI, 0.17 to 0.36), MAF=0.16, imputation r2=0.98, HWE P=0.11) with Angpt-2 concentration (Supplemental Figure 3). This variant is located in an intron of the transmembrane protease, serine 4 (TMPRSS4) gene and explained 2.12% of the variability in Angpt-2 concentrations at 3 months (Supplemental Figure 4). There were no SNPs significantly associated with Angpt-1 concentrations or the Angpt-1:Angpt-2 ratio. In univariable analysis, the presence of more copies of the minor allele of rs611475 was also significantly associated with CKD progression (HR: 1.30; 95% CI, 1.05 to 1.62) and all-cause mortality (HR: 1.31; 95% CI, 1.04 to 1.65) but not with HF (HR: 0.93; 95% CI, 0.7 to 1.25). When adjusting for age, sex, center, and PCs, rs611475 remained significantly associated with CKD progression (aHR: 1.28; 95% CI, 1.02 to 1.60) and trended toward significance for all-cause mortality (aHR: 1.26; 95% CI, 1 to 1.58). There were no independent associations with HF (aHR: 0.95; 95% CI, 0.71 to 1.27). In mediation analysis we determined that 27% (95% CI, 8% to 61%) of the association between rs611475 and CKD progression was explained by Angpt-2 (Supplemental Figure 5). Furthermore, a regional association plot (Supplemental Figure 6) identified multiple SNPs in linkage disequilibrium with our index SNP (rs611475) that were nominally associated with Angpt-2 concentrations, supporting this loci as a protein quantitative trait loci for Angpt-2 concentrations.

Discussion

In this study, we explored the association of plasma angiopoietins, which are markers of vessel integrity and repair, in the setting of AKI with the primary outcomes of CKD and HF and the secondary outcome of mortality. We found that a higher Angpt-1:Angpt-2 ratio measured 3 months after hospitalization was associated with substantial reduction in CKD progression, HF, and mortality among participants with AKI compared with those without AKI. Lastly, an intronic TMPRSS4 variant was found to be associated with Angpt-2 concentrations and with CKD progression, suggesting an underlying relationship between the identified variant and CKD progression.

Angiopoietins are involved in endothelial cell responses to injury, which is imperative in kidney and heart disease progression as the endothelium and its protector, the pericyte, are crucial factors in the development of fibrosis.42–44 In the setting of AKI, there is endothelial cell activation with an increase in the release of Angpt-2.45–48 This overproduction of Angpt-2 relative to Angpt-1 leads to increased blood vessel permeability and peritubular capillary loss, promoting interstitial fibrosis.49–53 Conversely, targeted overexpression of Angpt-1 in the kidney has been shown to ameliorate interstitial fibrosis by reducing myofibroblast activation, collagen I accumulation, TGFβ upregulation, and by increasing peritubular capillary growth.54

Angiopoietins have similar effects in the heart and in the kidneys. Preclinical studies of both rat and mouse models have shown that inhibition of Angpt-2 ameliorates ischemia-reperfusion injury in the heart, whereas Angpt-2 overexpression increases cardiac fibrosis and vessel instability.55,56 In contrast, Angpt-1 protects against cardiac arteriosclerosis and cardiac myocyte apoptosis, leading to improved cell survival in rats.57 Our results reflect the known biology of the angiopoietin pathway and underscore its significance in the setting of human kidney and heart disease. The identified associations with CKD progression and mortality are also similar to prior published work by David et al. where higher levels of Angpt-2 were associated with higher mortality in the setting of CKD.58 Moreover, the associations of the angiopoietin pathway with CKD progression and HF were more notable among patients with AKI, which may reflect the triggering of repair pathways after injury. Ischemia-reperfusion injury has been shown to lead to increased concentrations of angiopoietins59 and may explain why we identified stronger associations with long-term outcomes in the setting of AKI. Furthermore, there is a dose-dependent response in angiopoietin levels to the severity of ischemic injury. It has been shown that there are higher levels of Angpt-2 with worsening stages of AKI, and lower levels of Angpt-1 with higher stages of AKI in critically ill patients.60 However, it is unclear if AKI at index hospitalization is what led to the increase in angiopoietin concentrations at 3 months versus recurrent AKI, which we did not evaluate in this study. It is important to note that angiopoietins had significant associations with outcomes independent of commonly used clinical markers such as baseline CKD, proteinuria, and eGFR at time of angiopoietin measurement for the outcome of CKD progression and troponin and NT-proBNP for the outcome of HF. Lastly, Angpt-1 appeared to mediate the relationship between AKI and outcomes, which may highlight a potential mechanistic role of angiopoietins in long-term sequelae after injury. However, it is important to note that we cannot infer causality from our findings.

We also identified a TMPRSS4 variant (rs611475) associated with higher risk of CKD progression, where 27% of this association appeared to be mediated by Angpt-2. rs611475 is a single-nucleotide variation (T/C) within an intron of TMPRSS4 (and the negative strand of SMIM35) with an MAF of 15%61; however, the effect of this variant on TMPRSS4 function or expression is not known. The TMPRSS4 gene encodes for a member of the serine protease family and the encoded protein is membrane bound with a glycosylated extracellular region containing the serine protease domain.62 Although TMPRSS4 may facilitate SARS-CoV-2 cellular entry,63 a role for TMPRSS4 in CKD progression has not been previously considered. Single-cell64 and single-segment65 RNA sequencing studies in mice have shown little expression of TMPRSS4 in renal epithelia, but higher levels of expression in infiltrating leukocytes and fibroblasts. Single-cell sequencing of human diabetic kidneys revealed a slight increase in TMPRSS4 in the loop of Henle compared with nondiabetic kidneys.66 High levels of TMPRSS4 are associated with poor prognosis in several types of cancer, where effects on cell proliferation, epithelial-mesenchymal transition, and mobility are reported.67 Further studies will be required to confirm the association of TMPRSS4 with progressive CKD and to elucidate the mechanistic pathways involved. Other SNPs have been identified to be associated with Angpt-2 concentrations and outcomes such as acute respiratory distress syndrome and AKI,68,69 but none of these SNPs were significantly associated with Angpt-2 concentrations in our genomic analysis. Given our small sample size and lack of a validation cohort, it is difficult to make strong inferences regarding our identified SNP and associations.

The identified associations between angiopoietins and AKI outcomes represent the initial building blocks for future studies investigating the role of therapeutic targeting of the angiopoietin pathway in improving outcomes after AKI. Either promoting the role of Angpt-1 and blocking Angpt-2 ameliorates kidney disease in animals by preserving peritubular capillaries and decreasing fibrosis.30,52,70 Currently, there are several phase I and phase II clinical trials targeting the angiopoietin pathway in different disease etiologies (Supplemental Table 8),71–75 but none are in the setting of AKI.

Our study has several strengths including its large, multicenter, prospective design and broad inclusion criteria, which limited selection bias, and enhanced the generalizability of our findings, allowing subgroup analyses. The prospective evaluation of the outcomes limited reverse causality and allowed accurate temporal assessments of the analyzed relationships. Given the extensive variable collection, we were able to account for multiple confounders to accurately assess the independent associations of angiopoietins and outcomes. Additionally, because of the carefully matched study design, we were able to study the prognostic value of angiopoietins among patients who had AKI and those who did not.

We also recognize that our study has a number of limitations. There was no external validation, which limits the accuracy of our findings.76 Given our observational study design, there may be unmeasured confounding, and despite adjusting for known comorbidities, there is still the potential that underlying illnesses confound the identified associations. To address this, we have shown that similar patient characteristics are present when stratifying by quartiles of angiopoietin levels at 3 months and when stratifying by quartiles of change in angiopoietin levels from baseline. This likely highlights that angiopoietins risk-stratify a group of patients with certain comorbidities and biochemical information. Our study does not address how phenotyping of AKI may have influenced our results, as these data were not available. Because we did not have pre-AKI measurements of angiopoietins, whether elevations in these markers preceded AKI remains unknown. The use of the ratio has been used in prior work in AKI,60,77 acute lung injury,78 and preeclampsia,79 but because the use of the ratio has not been established clinically, we also adjusted for each of the biomarkers. The adjusted analyses yielded similar results to using the ratio. Our study is also limited in that it does not address how the angiopoietin pathway interacts with other pathways. In future analysis, we will evaluate the effects of angiogenesis markers, such as vascular endothelial growth factor A, on the association between angiopoietins and outcomes. Additionally, the GWAS analysis was limited given lack of a validation cohort; given the small sample size we were unable to assess for group specific effects. However, the association analyses between rs611475 and CKD progression were adjusted for age, sex, center, and genomic variant PCs. The angiopoietin pathway is likely one of several vascular pathways involved in CKD progression and HF; hence, our study does not address other pathways involved in endothelial cell repair that may influence outcomes.80–83 Lastly, our study does not address recurrent AKI episodes, rehospitalizations, and other events after discharge that could have influenced the development of outcomes.

In conclusion, a higher Angpt-1:Angpt-2 ratio measured 3 months after discharge is strongly associated with a lower risk of developing CKD progression, HF, and death. These associations were stronger in the setting of AKI. Furthermore, a TMPRSS4 variant was associated with Angpt-2 concentrations and with CKD progression. Angiopoietins may elucidate a pathophysiologic pathway explaining the development of long-term sequelae after AKI for the purpose of implementing future interventions.

Disclosures

P.K. Bhatraju reports research funding with Roche Diagnostics. V.M. Chinchilli reports scientific advisor or membership with Allergan, AstraZeneca, Biohaven, Janssen, Regeneron, and Sanofi. S.G. Coca reports personal fees from Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, CHF Solutions, Quark, Relypsa, and Takeda; personal fees and other from ProKidney and pulseData; grants, personal fees, and other from RenalytixAI; consultancy agreements with 3ive, Axon, Reprieve Cardiovascular, and Vifor; ownership interest with pulseData and Renalytix; research funding with ProKidney, RRI, and XORTX; patents and inventions with Renalytix; scientific advisor or membership with Renalytix and Reprieve Cardiovascular; associate editor for Kidney360; editorial board for Kidney International, CJASN, and JASN. A.X. Garg reports research funding with Astellas and Baxter; editorial board for American Journal of Kidney Diseases and Kidney International; serving on the Data Safety and Monitoring Board for an anemia trial program funded by GlaxoSmithKline, as the medical lead role to improve access to kidney transplantation and living kidney donation for the Ontario Renal Network (government funded agency located within Ontario Health). A.S. Go reports research funding with Amarin Pharmaceuticals, Bristol Myers Squibb, CSL Behring, iRhythm Technologies, Janssen Research and Development, and Novartis. J. Himmelfarb reports consultancy with Akebia Therapeutics, Chinook Therapeutics, Maze Therapeutics, Pfizer, RenalytixAI, and Seattle Genetics; honoraria with various academic institutions for invited lectures; editorial boards for BMC Medicine and CJASN; scientific advisory board for Nature Reviews Nephrology; research grant support from Northwest Kidney Centers; and founder and equity holder of Kuleana Technology, Inc. C.-y. Hsu reports consultancy for legal cases involving kidney disease (acute or chronic) and on an ad hoc basis for companies regarding kidney disease; research funding with Satellite Healthcare; honoraria with Satellite Healthcare; and royalties from UpToDate. T.A. Ikizler reports consultancy agreements with Abbott Renal Care, Corvidia, Fresenius Kabi, ISN, La Renon, and Nestle; honoraria with Abbott Renal Care, Fresenius Kabi, International Society of Nephrology, La Renon, and Nestle; patents and inventions with Vanderbilt University School of Medicine; and scientific advisor or membership with Fresenius Kabi and Kidney International. J.S. Kaufman reports consultancy agreements with National Institutes of Health and National Kidney Foundation; ownership interest with Amgen; associate editor for American Journal of Kidney Disease; and steering committee chair for ASSESS-AKI, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disease (NIDDK). P.L. Kimmel reports co-editorship with Chronic Renal Disease Academic Press and Psychosocial Aspects of Chronic Kidney Disease; and royalties from Academic Press. K.D. Liu reports consultancy agreements with AM-Pharma, Biomerieux, BOA Medical, Durect, and Seastar Medical; stockholder with Amgen; editorial board for American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, American Journal of Kidney Diseases, and CJASN; scientific advisory board for the National Kidney Federation. S.M. Parikh reports consultancy to Johnson & Johnson; member of the scientific advisory board for Aerpio; consultancy agreements with Aerpio, Alkermes, Astellas, Cytokinetics, Hope Pharmaceuticals, Janssen, Leerink Swann, Mission Therapeutics, Mitobridge; ownership interest with Eunoia and Raksana; research funding with Baxter; honoraria with American Society of Nephrology; and scientific advisor or membership with JASN, Kidney360, and Raksana. C.R. Parikh reports member of the advisory board of and owns equity in RenalytixAI; consultant for Genfit and Novartis; research funding with NIDDK and National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute; and scientific advisor or membership with Genfit. W.B. Reeves reports ownership interest with Amgen. E.D. Siew reports consultancy agreements with Akebia Therapeutics; honorarium for an invited educational talk on AKI epidemiology at the DaVita Annual Physician Leadership Conference; editorial board for CJASN; and author for UpToDate (royalties). I.B. Stanaway reports ownership interest of Byrell Systems, LLC, registered in Washington State that is solely owned by him. H. Thiessen-Philbrook is statistical editor for Kidney360. F.P. Wilson reports consultancy agreements with Translational Catalyst, LLC; ownership of Efference, LLC; research funding with Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Vifor; editorial board for American Journal of Kidney Disease and CJASN; and board of directors for Gaylord Health Care; and medical commentator for Medscape. M.M. Wurfel reports consultancy agreements with Roche Diagnostics; research funding with Roche; and honoraria with Roche Diagnostics. All remaining authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

This work was supported by the American Heart Association (grant 18CDA34110151) and Yale O’Brien Center (pilot grant 5P30DK079310).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all of the ASSESS-AKI study participants, research coordinators, and support staff for making this study possible. The ASSESS-AKI was supported by cooperative agreements from the NIDDK (U01DK082223, U01DK082185, U01DK082192, and U01DK082183). We also acknowledge funding support from National of Institutes of Health (NIH) grants K23DK127154-01A1, R01HL085757, UH3DK114866, U01DK106962, and R01DK093770. The opinions expressed in this paper do not necessarily reflect those of the NIDDK, the NIH, the Department of Health and Human Services, or the government of the United States.

Author Contributions

S.G. Mansour designed the study, interpreted the data, and drafted and revised the paper; P.K. Bhatraju, I.B. Stanaway, Y. Jia, and H. Thiessen-Philbrook analyzed the data and revised the paper; W. Obeid measured the biomarkers and revised the paper; S.G. Coca, F.P. Wilson, A.S. Go, T.A. Ikizler, E.D. Siew, V.M. Chinchilli, C.-y. Hsu, A.X. Garg, W.B. Reeves, K.D. Liu, P.L. Kimmel, J.S. Kaufman, M.M. Wurfel, J. Himmelfarb, and S.M. Parikh revised the paper; C.R. Parikh supervised the study, interpreted the data, and revised the paper; and all authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

Supplemental Material

This article contains the following supplemental material online at http://jasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1681/ASN.2021060757/-/DCSupplemental.

Supplemental Table 1. Demographic and clinical characteristics of the entire cohort and stratified by quartiles of angiopoietin-1 delta.

Supplemental Table 2. Demographic and clinical characteristics of the entire cohort and stratified by quartiles of angiopoietin-2 delta.

Supplemental Table 3. Angiopoietin concentrations in participants.

Supplemental Table 4. Associations between angiopoietin quartiles and all-cause mortality.

Supplemental Table 5. Associations between angiopoietin quartiles and CKD progression (death as competing event).

Supplemental Table 6. Associations between angiopoietin quartiles and heart failure (death as competing event).

Supplemental Table 7. Mediation analysis to assess the effect of Angpt-1 and Angpt-2 on the relationship between AKI and outcomes.

Supplemental Table 8. Summary of human clinical trials intervening on the angiopoietin pathway.

Supplemental Figure 1. Study flow diagram.

Supplemental Figure 2. Spline plots between angiopoietins and outcomes.

Supplemental Figure 3. One single-nucleotide polymorphism was associated with angiopoietin-2 concentrations.

Supplemental Figure 4. Distribution of angiopoietin-2 concentrations in plasma and allele count of TMPRSS4 variant rs611475.

Supplemental Figure 5. Conceptual diagram of mediation analysis.

Supplemental Figure 6. Regional association plot.

References

- 1.Sawhney S, Marks A, Fluck N, Levin A, Prescott G, Black C: Intermediate and long-term outcomes of survivors of acute kidney injury episodes: A large population-based cohort study. Am J Kidney Dis 69: 18–28, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coca SG, Yusuf B, Shlipak MG, Garg AX, Parikh CR: Long-term risk of mortality and other adverse outcomes after acute kidney injury: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Kidney Dis 53: 961–973, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coca SG, Singanamala S, Parikh CR: Chronic kidney disease after acute kidney injury: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Kidney Int 81: 442–448, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Horkan CM, Purtle SW, Mendu ML, Moromizato T, Gibbons FK, Christopher KB: The association of acute kidney injury in the critically ill and postdischarge outcomes: A cohort study*. Crit Care Med 43: 354–364, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Odutayo A, Wong CX, Farkouh M, Altman DG, Hopewell S, Emdin CA, et al. : AKI and long-term risk for cardiovascular events and mortality. J Am Soc Nephrol 28: 377–387, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chawla LS, Eggers PW, Star RA, Kimmel PL: Acute kidney injury and chronic kidney disease as interconnected syndromes. N Engl J Med 371: 58–66, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fu Y, Tang C, Cai J, Chen G, Zhang D, Dong Z: Rodent models of AKI-CKD transition. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 315: F1098–F1106, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Venkatachalam MA, Weinberg JM, Kriz W, Bidani AK: Failed tubule recovery, AKI-CKD transition, and kidney disease progression. J Am Soc Nephrol 26: 1765–1776, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu J, Kumar S, Dolzhenko E, Alvarado GF, Guo J, Lu C, et al. : Molecular characterization of the transition from acute to chronic kidney injury following ischemia/reperfusion. JCI Insight 2: e94716, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dong Y, Zhang Q, Wen J, Chen T, He L, Wang Y, et al. : Ischemic duration and frequency determines AKI-to-CKD progression monitored by dynamic changes of tubular biomarkers in IRI mice. Front Physiol 10: 153, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ko GJ, Grigoryev DN, Linfert D, Jang HR, Watkins T, Cheadle C, et al. : Transcriptional analysis of kidneys during repair from AKI reveals possible roles for NGAL and KIM-1 as biomarkers of AKI-to-CKD transition. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 298: F1472–F1483, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sato Y, Yanagita M: Immune cells and inflammation in AKI to CKD progression. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 315: F1501–F1512, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jotwani V, Katz R, Ix JH, Gutiérrez OM, Bennett M, Parikh CR, et al. : Urinary biomarkers of kidney tubular damage and risk of cardiovascular disease and mortality in elders. Am J Kidney Dis 72: 205–213, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Parikh CR, Puthumana J, Shlipak MG, Koyner JL, Thiessen-Philbrook H, McArthur E, et al. : Relationship of kidney injury biomarkers with long-term cardiovascular outcomes after cardiac surgery. J Am Soc Nephrol 28: 3699–3707, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bolignano D, Lacquaniti A, Coppolino G, Donato V, Campo S, Fazio MR, et al. : Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL) and progression of chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 4: 337–344, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kramann R, Tanaka M, Humphreys BD: Fluorescence microangiography for quantitative assessment of peritubular capillary changes after AKI in mice. J Am Soc Nephrol 25: 1924–1931, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mansour SG, Zhang WR, Moledina DG, Coca SG, Jia Y, Thiessen-Philbrook H, et al. ; TRIBE-AKI Consortium : The association of angiogenesis markers with acute kidney injury and mortality after cardiac surgery. Am J Kidney Dis 74: 36–46, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vincent IS, Okusa MD: Biology of renal recovery: Molecules, mechanisms, and pathways. Nephron Clin Pract 127: 10–14, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schrimpf C, Xin C, Campanholle G, Gill SE, Stallcup W, Lin SL, et al. : Pericyte TIMP3 and ADAMTS1 modulate vascular stability after kidney injury. J Am Soc Nephrol 23: 868–883, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Basile DP: The case for capillary rarefaction in the AKI to CKD progression: Insights from multiple injury models. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 317: F1253–F1254, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Go AS, Hsu CY, Yang J, Tan TC, Zheng S, Ordonez JD, et al. : Acute kidney injury and risk of heart failure and atherosclerotic events. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 13: 833–841, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Damman K, Testani JM: The kidney in heart failure: An update. Eur Heart J 36: 1437–1444, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Legrand M, Rossignol P: Cardiovascular consequences of acute kidney injury. N Engl J Med 382: 2238–2247, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chistiakov DA, Orekhov AN, Bobryshev YV: Endothelial barrier and its abnormalities in cardiovascular disease. Front Physiol 6: 365, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hohenstein B, Hugo C: Peritubular capillaries: An important piece of the puzzle. Kidney Int 91: 9–11, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Basile DP, Friedrich JL, Spahic J, Knipe N, Mang H, Leonard EC, et al. : Impaired endothelial proliferation and mesenchymal transition contribute to vascular rarefaction following acute kidney injury. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 300: F721–F733, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gogiraju R, Bochenek ML, Schäfer K: Angiogenic endothelial cell signaling in cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure. Front Cardiovasc Med 6: 20, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bábíčková J, Klinkhammer BM, Buhl EM, Djudjaj S, Hoss M, Heymann F, et al. : Regardless of etiology, progressive renal disease causes ultrastructural and functional alterations of peritubular capillaries. Kidney Int 91: 70–85, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hellberg PO, Källskog OT, Ojteg G, Wolgast M: Peritubular capillary permeability and intravascular RBC aggregation after ischemia: Effects of neutrophils. Am J Physiol 258: F1018–F1025, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jung YJ, Kim DH, Lee AS, Lee S, Kang KP, Lee SY, et al. : Peritubular capillary preservation with COMP-angiopoietin-1 decreases ischemia-reperfusion-induced acute kidney injury. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 297: F952–F960, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Duffield JS: Cellular and molecular mechanisms in kidney fibrosis. J Clin Invest 124: 2299–2306, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Drost CC, Rovas A, Kusche-Vihrog K, et al. : Tie2 activation promotes protection and reconstitution of the endothelial glycocalyx in human sepsis [published correction appears in Thromb Haemost 119: e1, 2019 10.1055/s-0039-3400534]. Thromb Haemost 119: 1827–1838, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bilimoria J, Singh H: The angiopoietin ligands and Tie receptors: Potential diagnostic biomarkers of vascular disease. J Recept Signal Transduct Res 39: 187–193, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Go AS, Parikh CR, Ikizler TA, Coca S, Siew ED, Chinchilli VM, et al. ; Assessment Serial Evaluation, and Subsequent Sequelae of Acute Kidney Injury Study Investigators : The assessment, serial evaluation, and subsequent sequelae of acute kidney injury (ASSESS-AKI) study: Design and methods. BMC Nephrol 11: 22, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ikizler TA, Parikh CR, Himmelfarb J, et al. : A prospective cohort study of acute kidney injury and kidney outcomes, cardiovascular events, and death. Kidney Int 99: 456–465, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McKee PA, Castelli WP, McNamara PM, Kannel WB: The natural history of congestive heart failure: The Framingham study. N Engl J Med 285: 1441–1446, 1971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Das S, Forer L, Schönherr S, Sidore C, Locke AE, Kwong A, et al. : Next-generation genotype imputation service and methods. Nat Genet 48: 1284–1287, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McCarthy S, Das S, Kretzschmar W, Delaneau O, Wood AR, Teumer A, et al. ; Haplotype Reference Consortium : A reference panel of 64,976 haplotypes for genotype imputation. Nat Genet 48: 1279–1283, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Loh PR, Danecek P, Palamara PF, Fuchsberger C, A Reshef Y, K Finucane H, et al. : Reference-based phasing using the Haplotype Reference Consortium panel. Nat Genet 48: 1443–1448, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chang CC, Chow CC, Tellier LC, Vattikuti S, Purcell SM, Lee JJ: Second-generation PLINK: Rising to the challenge of larger and richer datasets. Gigascience 4: 7, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hertzmark EPM, Spiegelman D: The SAS MEDIATE Macro. 2012. Available at: https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/donna-spiegelman/software/mediate/. Accessed January 21, 2022

- 42.Humphreys BD, Lin SL, Kobayashi A, Hudson TE, Nowlin BT, Bonventre JV, et al. : Fate tracing reveals the pericyte and not epithelial origin of myofibroblasts in kidney fibrosis. Am J Pathol 176: 85–97, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zeng H, Li L, Chen JX: Overexpression of angiopoietin-1 increases CD133+/c-kit+ cells and reduces myocardial apoptosis in db/db mouse infarcted hearts. PLoS One 7: e35905, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Murray IR, Baily JE, Chen WCW, Dar A, Gonzalez ZN, Jensen AR, et al. : Skeletal and cardiac muscle pericytes: Functions and therapeutic potential. Pharmacol Ther 171: 65–74, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.He FF, Zhang D, Chen Q, Zhao Y, Wu L, Li ZQ, et al. : Angiopoietin-Tie signaling in kidney diseases: An updated review. FEBS Lett 593: 2706–2715, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Woolf AS, Gnudi L, Long DA: Roles of angiopoietins in kidney development and disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 20: 239–244, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ziegler T, Horstkotte J, Schwab C, Pfetsch V, Weinmann K, Dietzel S, et al. : Angiopoietin 2 mediates microvascular and hemodynamic alterations in sepsis. J Clin Invest 123: 3436–3445, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Frangogiannis NG: Cardiac fibrosis: Cell biological mechanisms, molecular pathways and therapeutic opportunities. Mol Aspects Med 65: 70–99, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fligny C, Duffield JS: Activation of pericytes: Recent insights into kidney fibrosis and microvascular rarefaction. Curr Opin Rheumatol 25: 78–86, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Maisonpierre PC, Suri C, Jones PF, Bartunkova S, Wiegand SJ, Radziejewski C, et al. : Angiopoietin-2, a natural antagonist for Tie2 that disrupts in vivo angiogenesis. Science 277: 55–60, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Parikh SM, Mammoto T, Schultz A, Yuan HT, Christiani D, Karumanchi SA, et al. : Excess circulating angiopoietin-2 may contribute to pulmonary vascular leak in sepsis in humans. PLoS Med 3: e46, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Loganathan K, Salem Said E, Winterrowd E, Orebrand M, He L, Vanlandewijck M, et al. : Angiopoietin-1 deficiency increases renal capillary rarefaction and tubulointerstitial fibrosis in mice. PLoS One 13: e0189433, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Choi YJ, Chakraborty S, Nguyen V, Nguyen C, Kim BK, Shim SI, et al. : Peritubular capillary loss is associated with chronic tubulointerstitial injury in human kidney: Altered expression of vascular endothelial growth factor. Hum Pathol 31: 1491–1497, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Singh S, Manson SR, Lee H, Kim Y, Liu T, Guo Q, et al. : Tubular overexpression of angiopoietin-1 attenuates renal fibrosis. PLoS One 11: e0158908, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Syrjälä SO, Tuuminen R, Nykänen AI, Raissadati A, Dashkevich A, Keränen MA, et al. : Angiopoietin-2 inhibition prevents transplant ischemia-reperfusion injury and chronic rejection in rat cardiac allografts. Am J Transplant 14: 1096–1108, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chen JX, Zeng H, Reese J, Aschner JL, Meyrick B: Overexpression of angiopoietin-2 impairs myocardial angiogenesis and exacerbates cardiac fibrosis in the diabetic db/db mouse model. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 302: H1003–H1012, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nykänen AI, Krebs R, Saaristo A, Turunen P, Alitalo K, Ylä-Herttuala S, et al. : Angiopoietin-1 protects against the development of cardiac allograft arteriosclerosis. Circulation 107: 1308–1314, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.David S, John SG, Jefferies HJ, Sigrist MK, Kümpers P, Kielstein JT, et al. : Angiopoietin-2 levels predict mortality in CKD patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 27: 1867–1872, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Khairoun M, van der Pol P, de Vries DK, Lievers E, Schlagwein N, de Boer HC, et al. : Renal ischemia-reperfusion induces a dysbalance of angiopoietins, accompanied by proliferation of pericytes and fibrosis. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 305: F901–F910, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Robinson-Cohen C, Katz R, Price BL, Harju-Baker S, Mikacenic C, Himmelfarb J, et al. : Association of markers of endothelial dysregulation Ang1 and Ang2 with acute kidney injury in critically ill patients. Crit Care 20: 207, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.dbSNP Short Genetic Variations: Reference SNP (rs) Report. rs611475 Web site. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/snp/rs611475. Accessed January 26, 2021.

- 62.de Aberasturi AL, Calvo A: TMPRSS4: An emerging potential therapeutic target in cancer. Br J Cancer 112: 4–8, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zang R, Gomez Castro MF, McCune BT, Zeng Q, Rothlauf PW, Sonnek NM, et al. : TMPRSS2 and TMPRSS4 promote SARS-CoV-2 infection of human small intestinal enterocytes. Sci Immunol 5: eabc3582, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Park J, Shrestha R, Qiu C, Kondo A, Huang S, Werth M, et al. : Single-cell transcriptomics of the mouse kidney reveals potential cellular targets of kidney disease. Science 360: 758–763, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lee JW, Chou CL, Knepper MA: Deep sequencing in microdissected renal tubules identifies nephron segment-specific transcriptomes. J Am Soc Nephrol 26: 2669–2677, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wilson PC, Wu H, Kirita Y, Uchimura K, Ledru N, Rennke HG, et al. : The single-cell transcriptomic landscape of early human diabetic nephropathy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 116: 19619–19625, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jianwei Z, Qi L, Quanquan X, Tianen W, Qingwei W: TMPRSS4 upregulates TWIST1 expression through STAT3 activation to induce prostate cancer cell migration. Pathol Oncol Res 24: 251–257, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Reilly JP, Wang F, Jones TK, Palakshappa JA, Anderson BJ, Shashaty MGS, et al. : Plasma angiopoietin-2 as a potential causal marker in sepsis-associated ARDS development: Evidence from Mendelian randomization and mediation analysis. Intensive Care Med 44: 1849–1858, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bhatraju PK, Cohen M, Nagao RJ, Morrell ED, Kosamo S, Chai XY, et al. : Genetic variation implicates plasma angiopoietin-2 in the development of acute kidney injury sub-phenotypes. BMC Nephrol 21: 284, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kim W, Moon SO, Lee SY, Jang KY, Cho CH, Koh GY, et al. : COMP-angiopoietin-1 ameliorates renal fibrosis in a unilateral ureteral obstruction model. J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 2474–2483, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hyman DM, Rizvi N, Natale R, Armstrong DK, Birrer M, Recht L, et al. : Phase I study of MEDI3617, a selective angiopoietin-2 inhibitor alone and combined with carboplatin/paclitaxel, paclitaxel, or bevacizumab for advanced solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res 24: 2749–2757, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Campochiaro PA, Khanani A, Singer M, Patel S, Boyer D, Dugel P, et al. ; TIME-2 Study Group : Enhanced benefit in diabetic macular edema from AKB-9778 Tie2 activation combined with vascular endothelial growth factor suppression. Ophthalmology 123: 1722–1730, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Campochiaro PA, Sophie R, Tolentino M, Miller DM, Browning D, Boyer DS, et al. : Treatment of diabetic macular edema with an inhibitor of vascular endothelial-protein tyrosine phosphatase that activates Tie2. Ophthalmology 122: 545–554, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Regeneron Pharmaceuticals : Anti-vasculaR Endothelial Growth Factor plUs Anti-angiopoietin 2 in Fixed comBination therapY: Evaluation for the Treatment of Diabetic Macular Edema (RUBY). Available at: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/study/NCT02712008. 2018. Accessed November 11, 2020

- 75.Pfizer Pharmaceuticals : Safety and PK study of CVX-060 in patients with advanced solid tumors. Available at: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00879684. 2015. Accessed November 11, 2020

- 76.Bleeker SE, Moll HA, Steyerberg EW, Donders AR, Derksen-Lubsen G, Grobbee DE, et al. : External validation is necessary in prediction research: A clinical example. J Clin Epidemiol 56: 826–832, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bhatraju PK, Zelnick LR, Herting J, Katz R, Mikacenic C, Kosamo S, et al. : Identification of acute kidney injury subphenotypes with differing molecular signatures and responses to vasopressin therapy. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 199: 863–872, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ong T, McClintock DE, Kallet RH, Ware LB, Matthay MA, Liu KD: Ratio of angiopoietin-2 to angiopoietin-1 as a predictor of mortality in acute lung injury patients. Crit Care Med 38: 1845–1851, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bolin M, Wiberg-Itzel E, Wikström AK, Goop M, Larsson A, Olovsson M, et al. : Angiopoietin-1/angiopoietin-2 ratio for prediction of preeclampsia. Am J Hypertens 22: 891–895, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bagshaw SM: Epidemiology of renal recovery after acute renal failure. Curr Opin Crit Care 12: 544–550, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Bienaimé F, Canaud G, El Karoui K, Gallazzini M, Terzi F: Molecular pathways of chronic kidney disease progression. Nephrol Ther 12[Suppl 1]: S35–S38, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Zhang WR, Parikh CR: Biomarkers of acute and chronic kidney disease. Annu Rev Physiol 81: 309–333, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Vallejo-Vaz AJ: Novel biomarkers in heart failure beyond natriuretic peptides - The case for soluble ST2. Eur Cardiol 10: 37–41, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.