Abstract

The death of a loved one is extremely impactful. Although much of the focus now on helping people who are experiencing bereavement grief is oriented to distinguishing complicated from non-complicated grief for early pharmaceutical or psychiatric treatment, lay bereavement support comprises a more common and thus highly important but often unrecognized consideration. A wide variety of lay bereavement programs with diverse components have come to exist. This scoping research literature review focused on bereavement humor, one possible component. Humor has long been recognized as an important social attribute. Researchers have found humor is important for lifting the spirits of ill people and for aiding healing or recovery. However, humor does not appear to have been recognized as a technique that could benefit mourners. A multi-database search revealed only 11 English-language research articles have been published in the last 25 years that focused in whole or in part on bereavement humour. Although minimal evidence exists, these studies indicate bereaved people often use humor and for a number of reasons. Unfortunately, no investigations revealed when and why bereavement humor may be inappropriate or unhelpful. Additional research, multi-cultural investigations in particular, are needed to establish humor as a safe and effective bereavement support technique to apply or to use. Bereavement humor could potentially be used more often to support grieving people and bereaved people should perhaps be encouraged to use humor in their daily lives.

Keywords: Bereavement, Grief, Mourning, Humor, Laughter, Literature review

Few people escape the experience of grieving the death of a loved one (Wilson et al., 2018). Although much of the current academic literature on bereavement grief is oriented towards distinguishing complicated from non-complicated grief for early pharmaceutical and psychiatric treatment considerations (Moayedoddin & Markowitz, 2015; Wilson et al., 2020), lay bereavement support approaches comprise an important focus of attention as most grieving processes extend over months, if not years (Abeles et al., 2004; Wilson et al., 2018). This extended grief trajectory means that mourning is primarily, if not wholly, experienced outside of medical offices and healthcare facilities. It is not surprising then that a wide variety of lay bereavement support services and programs, often with varying components, have come to exist (Wilson et al., 2019). Evaluations of these generally indicate value in helping bereaved people understand, manage, or overcome their grief (Wilson et al., 2019). However, only a small proportion of mourners attend bereavement support programs (Wilson et al., 2018). It could be that specific components of these programs or other less formal activities should be considered then for their relevance in helping people as they progress through their grief journey.

Humor has long been recognized as an important social activity, although primarily for amusement purposes only (Warren & McGraw, 2016). Michel (2017) advised that “laughter is universal across human cultures” and that “humans start developing a sense of humor as early as 6 weeks old, when babies begin to laugh and smile in response to stimuli” (para. 3). Moreover, Polimeni and Reiss’ (2006) understanding of humor, that was gained through a historical assessment of its origin and uses, revealed that “humor is the underlying cognitive process that frequently, but not necessarily, leads to laughter” (p. 1). Regardless of these or other humor distinctions, researchers have discovered that humor can reduce stress among healthy people (Nezu et al., 1988). Humor can also lift the spirits of ill people (Beach & Prickett, 2017), and assist healing or recovery from an illness (Baik & Lee, 2014). Moreover, humor, joy, and positivity have often been advised to overcome life difficulties (Lu & Steele, 2019; Shifman & Lemish, 2010). Attention to humor appears to be growing now, possibly because of the COVID-19 pandemic, as illustrated by the first online World Laughing Championship, held on April 1st, 2021.

To date, humor has not been broadly recognized as a technique to lift the spirits of bereaved people. It is not even clear if humor is an appropriate approach for helping someone who is experiencing acute or resolving grief. Nor is it evident if grieving people use humor themselves to help others around them who are grieving or to help themselves as they experience their personal grief journey. In short, humor is not widely viewed now as a way for mourners to manage or overcome the pain and loss associated with the death of a loved one. Given the potential for humor to be a readily available, inexpensive, and helpful bereavement support modality, a research literature review was undertaken to determine the extent of research on bereavement humor, and explore and describe the research evidence available at this time.

Materials and Methods

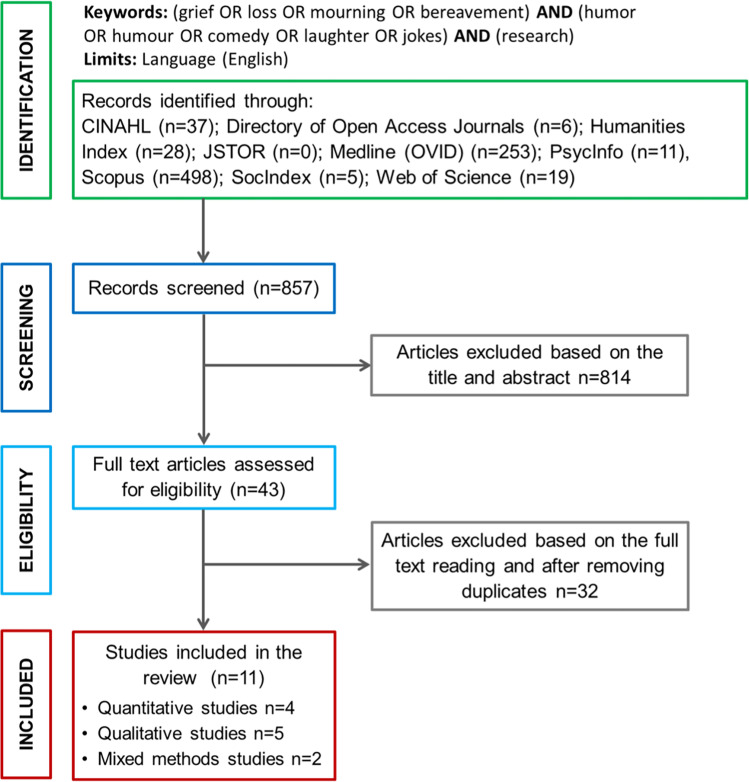

After consultation with a university librarian, nine academic library databases were searched for published English-language research reports with abstracts using the keywords “grief or loss or mourning or bereavement” and “humor or humour or comedy or laughter or jokes,” and “research.” These nine databases were considered the most likely to contain relevant research articles for review: CINAHL, Directory of Open Access (online) Journals, Humanities Index, Journal Storage (JSTOR), Medline (Ovid), PsychInfo, Scopus, SocIndex, and Web of Science. Reports of all kinds of research investigations were sought, in keeping with the established methodology of scoping literature reviews (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005; Whittemore & Knafl, 2005). As this project involved a systematic search for and analysis of published literature, it did not require research ethics committee approval to proceed.

Scoping reviews are a common type of literature review, although they are distinguished from other types as they gather and assess all types of research reports, and they typically focus on new topics or emerging questions of interest (Armstrong et al., 2011; Grant & Booth, 2009; Levac et al., 2010; Munn et al., 2018). Like other reviews, scoping reviews are done to assess how much research has already been done on a defined topic or question, and to determine what evidence and evidence gaps exist. However, scoping reviews do not include an assessment of the quality of the research articles that are identified for review, as all published research reports that are identified on a specific topic are considered likely to contain information of benefit. No efforts are made then to limit the review to only comprehensively-written reports of high-quality studies. Accordingly, this scoping review was carried out to identify all published English-language research reports that focused in whole or in part on bereavement humor, and explore and describe the findings to identify evidence and evidence gaps. No limit was placed on the year of publication, in keeping with our plan to scope the research conducted to date on bereavement humor. One final consideration is that this review only sought evidence on bereavement humor, as compared to humor associated with other challenging life events, such as divorce or retirement. It is possible that humor findings may be similar across them, but bereavement humor could be entirely distinct as humor is not generally associated with death, dying, or bereavement.

Each database was searched using the specified search terms, with varying numbers of potential articles for review identified in each database. All of the identified abstracts in each database were assessed for review inclusion or exclusion. Full papers were read whenever an abstract appeared to feature research that was focused, in whole or in part, on bereavement humor. All research publications that did not focus in whole or in part on post-death bereavement humor were rejected from review. Moreover, publications that did not describe a research investigation and reveal research findings were also rejected from review. However, as scoping reviews are undertaken on new or emerging topics or questions of rising interest, theory-based and other non-research papers were noted whenever they focused on bereavement humor and had content of relevance to building an understanding of bereavement humor. Each identified theory or non-research paper was assessed for informational relevance on a case-by-case basis, with the content of notable papers briefly outlined below.

A description of research and non-research findings in each database follows, in alphabetical order by database name. A PRISMA diagram (Fig. 1) was developed to reveal this search and selection process (Tricco et al., 2018). A table of research findings was also developed to highlight research information addressing the aim of this literature review (Table 1). Once compiled, the findings were subjected to content analysis, a process focused on identifying common and diverse or contradictory findings across the reviewed research articles. The findings from this content analysis were then used to identify evidence and evidence gaps.

Fig. 1.

Prisma Diagram of Search and Selection

Table 1.

Literature Review Findings

| Citation and country | Research Method | Research Findings on Grief and Humor |

|---|---|---|

| Brewer & Sparkes, 2011. UK. | Qualitative, 2-year ethnography study, with interviews of 13 young people who had been parentally bereaved to determine how they dealt with their grief. | Enjoyment (identified as having fun, a sense of humor, and laughing) was found to be 1 of 4 main ways that they dealt with their grief. Humor served many purposes, including “reducing distress, building rapport and enhancing mood…. Participants also used laughter as a tactic to prevent a serious subject becoming too difficult to discuss” (p. 288). Many also described being able to laugh at themselves (with no explanation of this finding or its value provided). One youth used humor in reaction to negative emotions and life difficulties. This use and other uses of humor were a way of distancing themselves from their feelings of loss, and also a way to help them make sense of their grief. Humor also strengthened relationships with other people. |

| Booth-Butterfield et al. (2014). USA. | Quantitative, survey completed by 484 people grieving the death of a spouse or parent primarily, average age 48.4. | Having a personal “humor orientation” was associated with a greater use of humor in coping with their grief; males were found to have a higher humor orientation trait than females. Having a humor orientation was also linked with more effective coping. Greater or more effective coping efforts were inversely associated with physical health problems and physiological problems. |

| Cadell. (2007). Canada. | Qualitative, grounded theory analysis of interview data from 15 caregivers of people who had died of AIDS to determine how they found meaning in their bereavement. | Humor was identified as a theme among other findings, with many people using humor. Humorous anecdotes were often provided about their caregiving and bereavement experiences. For some, however, laughter or humor symbolized the end of grief and thus a closure over a death. Humor also restored dignity and provided support as it was considered by them to be a coping mechanism that helped them as they did their AIDS work; this included dark humor used at times. Personal growth was evident and it was considered a positive outcome of caregiving. |

| Caplan et al. (2005). USA. | Qualitative, examination of journals written over 3 days by 41 older community-dwelling people following a major loss, often the death of a loved one. | Among all statements provided in the assessed journals, less than 1% were humorous. Instead, facts and feelings, as well as evaluative statements were often written. Themes of loss and themes of feeling were identified. Positive outlooks were evident among some participants, although humor or laughter was not often emphasized by these people. |

| Donnelly. (1999). Ireland. | Qualitative, 2-year ethnography study, to identify traditions associated with death and dying in rural west Ireland, with interviews of 30 local people who were asked to recall memories of care of the dying in their rural area. | Humor was often identified in the interviews as a common feature of death, dying, and bereavement; as illustrated by: “Humour. A striking feature of these interviews was the enthusiasm with which interviewees talked about what today might be considered inappropriate” (p. 60). Examples of humor that had been used by dying persons, family caregivers, and family members were provided to illustrate instances of humor and the use of humor in the community. This study revealed “the collective wisdom of lay people who were familiar with dying and death” (p. 61), with “humour never far away” (p. 57). |

| Kanacki. (2010). USA. | Qualitative, grounded theory study involving interviews of 25 elderly widows after spousal death (6 months to 10 years before) in a hospital or hospice to explore perceptions of end-of-life care. | This study identified a process or transition near the end of life where they and their dying spouse came to realize and accept the impending death. This study also identified laughter and humor could be of benefit after the death for widows during the bereavement process. However, this finding of post-death laughter and humor was said to need exploration in future studies. |

| Keltner & Bonanno. (1997). USA. | Mixed-methods, a questionnaire and then interviews of 39 bereaved people aged 21–50, who were interviewed 3–6 months after the death of their spouse to test if laughter was related to reduced distress and enhanced social relationships in post-death bereavement. | Laughter that took place during the interview was associated with reduced distress among those interviewed. Laughter could also be a way of acknowledging one’s own distress, and a way of recognizing distress in others. Laughter was also linked with an enhanced recollection of the deceased and then with enhanced relationships in the post-death period. Laughter and smiling could give observers the impression that the bereaved person was healthier, better adjusted, less frustrated, and more amusing than bereaved people who did not laugh or smile. Bereaved people who laughed and smiled were also more likely to be socially connected with other people. |

| Leaver & Highfield. (2018). Australia. | Mixed-methods, analysis of pre-birth ultrasounds and post-death funeral/ bereavement videos; quantitative analysis of the frequency and size of Instagram images and videos gathered in 2014. Qualitative analysis of 14 days of Instagram images and text, with coding of common elements. | Flower arrangements and other typical funeral icons were the most common posted images, with “some” humorous and ironic images posted as well. Selfies, showing smiling people at funerals and other post-death events, were often posted and these were thought to depict the message that the grieving person is coping well. However, the researchers believe a depth of feeling may also be shared through Instagram videos/images. Instagram was thus viewed as a possible avenue for understanding how death is discussed in social media. In social media, was most often a sharing of the grieving person’s emotional state, and not a eulogy or other focus on the deceased. The videos and images were mainly posted for the benefit of the bereaved persons, who shared their emotions. |

| Lund et al. (2009). USA. | Quantitative, with 292 recently bereaved person aged 50 or older in two USA locations, who were surveyed to gain their thoughts on the importance of daily positive emotions and to determine the existence of daily positive emotions in bereavement. | Most of the bereaved spouses rated both humor and happiness as being very important in their daily lives; with 75% experiencing humor, happiness, and laughter on a daily basis. The researchers stated that this finding of daily experiences of humor and happiness, given that most people were only four months bereaved, was unexpected. Daily humor, laughter, and/or feelings of happiness were strongly associated with lower levels of grief and depression. This was also found when subjects valued humor, laughter, or feelings of happiness. Black and Caucasian people more often valued and reported the experience of humor, laughter, and happiness as compared to Asians, Latinos, and Pacific Islanders. Blacks used humor early in the bereavement process, while other races may culturally discourage shows of enjoyment. When the death was expected, humor, happiness, and laughter were more commonly found. People who experienced and valued humor, laughter, and happiness had more positive grief adjustments. |

| Ong et al. (2004). USA. | Quantitative, with 34 recently bereaved older adults completing a questionnaire and daily diary entries for 98 days to learn how positive daily emotions impact depression and anxiety levels. | Daily positive emotions, including emotions that started immediately after the death, were critical for reduced post-death depression and anxiety. Each day that positive emotions were present, less depression and anxiety were evident. Correspondingly, for each day of fewer positive emotions, greater depression and anxiety were evident. Some widows had greater “humor coping” skills, with these persons also identified as having a resilience trait. These people were more resistant to stress and depression following the death. |

| Taylor et al. (2010). Australia. | Quantitative, a 2007 telephone-call population health survey completed by 3995 representative adults, some grieving the death of a loved one. | Responses to the question “What gets you through tough times?” varied but could be grouped into 14 subject-area categories. Among these, social supports was the most common category: 51.7% reported relying on family or self, 20.1% relied on friends and neighbors, and 17% reported positive personal emotional and philosophical strategies in use such as determination and humor. |

Results

CINAHL

Thirty-seven articles were identified as potentially relevant for review in the CINAHL database. All but four were immediately rejected, as they did not focus on post-death grief, such as Bouchard’s (2016) dissertation report that described compassion fatigue among emergency room nurses, with dark humor noted as a symptom of compassion fatigue. All articles that did not describe a research study and its findings were also rejected, although one article had notable content. Brass’s (2013) advisory article outlined ways to cope with a major life change or crisis, with laughter identified as a helpful coping activity.

After all of the research reports were assessed, three were retained for review (Brewer & Sparkes, 2011; Donnelly, 1999; Kanacki, 2010). Brewer and Sparkes’ (2011) study sought to determine how young people, who were parentally bereaved, dealt with their grief. Donnelly’s (1999) study identified traditions associated with death and dying in rural west Ireland. Kanacki’s (2010) dissertation study examined the experiences and needs of elderly widows after spousal death had taken place. The dissertation report was retained in its entirety, as a subsequent publication from it did not feature humor (Kanacki et al., 2012).

Directory of Open Access Journals

Six potential articles were identified for review in the Directory of Open Access Journals. None of the three theory or non-research articles had relevant content to report. One research report among the remaining three papers was retained, as it met the criteria for review. Taylor et al. (2010) studied what people do to get themselves through tough times, such as the death of someone important to them.

Humanities Index

The Humanities Index database revealed 28 potential articles for review. None of these were research reports, but four papers had notable content. Willett and Willett’s (2020) article explored the role of comedy in helping people make sense of their grief following a death, with death identified as a life tragedy. Sosa (2013) described humor as a means by which survivors in post-dictatorial Argentina gained an alternative source of remembrance of the dead, and with humor (including dark and bitter humor) having become a collective strategy in that country to cope with loss. Soares (2011) reviewed a book written by a woman who experienced the death of her mother as a child, with this book said to be “sprinkled” with humor, and with humor identified as one of many emotions co-mingled in that book. Macnab and Scherfig (2003) described a movie on death and bereavement that contained “unexpected” humor.

Journal Storage (JSTOR)

The JSTOR database revealed no potential articles for review. This finding was unexpected, as this database provides access to 12 million academic journal articles, associated with 2600 scholarly journals in the humanities, social sciences, and sciences.

Medline (OVID)

A total of 253 possible articles were identified for review in the Medline database. Many, however, were theory or non-research articles with no content relevant to this literature review. Similarly, most of the identified research articles focused on unrelated topics, although some did focus on humor for coping with adversity. For instance, one report was of an investigation that studied critical care nurses and their use of humor to enable their continued work in emotionally-demanding work settings (Cricco-Lizza, 2014). Another rejected research article described coping processes that foster accommodation to old-age losses, with these being losses other than bereavement (Thumala et al., 2020). However, that study found humor was critically important for dealing with old-age losses, and humor was used more often by people who had successfully accommodated old-age losses (Thumala et al., 2020). Another study report was rejected as it focused on dying processes in an Irish palliative care unit, with family members often using humor at this time (Donnelly & Donnelly, 2009). Moreover, a study of palliative care patients revealed they often used humor to help themselves raise and discuss major topics as they neared the end of life (Langley- Evans & Payne, 1997). Two additional humor research articles were also rejected as each study was not situated post-death, but instead highlighted humor before death (Beach & Prickett, 2017; Boots et al., 2015).

Six research reports among the 253 possible articles were found relevant for review, although two of these had already been identified in another database for review (Brewer & Sparkes, 2011; Donnelly, 1999). The four new research articles focused in whole or in part on bereavement humor (Cadell, 2007; Keltner & Bonanno, 1997; Lund et al., 2009; Ong et al., 2004). Cadell (2007) interviewed people to determine how they found meaning in their bereavement, a study that revealed humor was used. Keltner and Bonanno’s (1997) study tested humor as a method for reducing bereavement distress. Lund et al.’s (2009) survey sought to determine the incidence and importance of positive emotions (including humor) in bereavement. Ong et al.’s (2004) study examined how positive daily emotions (including humor) could impact depression and anxiety levels among bereaved individuals.

PsychInfo

Eleven potential articles to review were identified in the PsychInfo database. None of the theory or non-research articles had notable bereavement humor content. Three of the research articles were relevant for review, but all three had previously been identified and retained for review (Brewer & Sparkes, 2011; Cadell, 2007; Donnelly, 1999).

Scopus

A total of 498 articles were identified in the Scopus database for possible review. Many were rejected as they were not research study reports, but four theory or non-research papers were noted for having relevant content on bereavement humor. One described the joking that is done by attendees at African funerals and African funerals where comedians were increasingly appearing (Pype, 2015). Marmo’s (2010) article indicated that humor was often used by grieving family members; with humor easing tensions, reducing stress, and opening lines of communication among family members who are coping with a death. Moreover, in that paper, humor was said to help initiate a realization of one’s own death in the future (Marmo, 2010). Similarly, a report about the House of Being, a Holocaust-survivor combined geriatric center and memorial museum in Israel, discussed the common use of humor and the importance of humor for Holocaust descendants (Kidron, 2010). Basu (2007) provided an historical discussion about the first use of bereavement humor in mid seventeenth century England, and advised that this emergence of humor was a change from the status quo as it represented a democratic social development.

Three additional non-research Scopus articles were informative about humor in general. A theoretical article by Colin and Vives (2020) discussed the ability to laugh at oneself, a matter first highlighted by Sigmund Freud in 1927. Colin and Vives’ (2020) English-language abstract to a non-English paper concluded that “humor could be one of the most elaborated paths to psychic growth, which nevertheless does not neglect the painful aspects of external reality” (p. 399). Warner-Garcia (2014) discussed laughing that occurs whenever there is a disagreement between people, with humor identified then as “a social phenomenon and used as a resource for managing social relationships and identities. While it is often unplanned and uncensored, laughter is also strategically produced at particular moments to accomplish particular goals in interaction” (p. 157). Furthermore, Heath-Kelly and Jarvis’s (2017) discussion of humor highlighted it as a way to cope with a risk of death, including the death of others. Heath-Kelly and Jarvis (2017) also emphasized that humor customs change over time, with new opportunities for humor arising from social changes and developments in everyday life.

Most of the research articles revealed in the Scopus database search were rejected as they did not focus on the topic of post-death bereavement humor. Two, however, had notable humor content. Hussein and Aljamili’s (2020) research report discussed humor occurring in Jordan during the COVID-19 pandemic as a way of “softening the grim mood created by the Pandemic” (p. e05696). Hussein and Aljamili used Kress and Leeuween’s social semiotics approach to analyze specific semiotic patterns in COVID-related caricatures and memes in Jordanian social media to identify what humor types were present and to determine how humor was being helpful. A similar research exploration was conducted by Torres et al. (2020) who examined English and Tagalog COVID-related humor scripts on social medial platforms that had been posted to “soften grief, lighten mood, distract people from the struggle in accepting the new normal… (and) used as coping mechanism for the bad scenario experienced by many” (p. 138). Their study identified a diverse range of humor types, targets, subjects, and structures.

Four additional research articles were rejected from review as they did not feature post-death bereavement humor but they had some relevant content to note. One study report focused on the functional and dysfunctional use of humor by funeral professionals as they cope with constant exposure to death and bereavement (Grandi et al., 2019). A study of the use of humor in the classroom revealed it could be beneficial for student learning (Ramesh et al., 2011). Damianakis and Marziali (2011) focused on the use of humor by older community-living adults, with their study revealing four humor types, all of which contributed to sustaining positive social connections and assisted personal ability to accept age-related losses. Mir and Cots (2019) noted differences in Spanish and English humor associated with giving and receiving compliments.

Seven research reports among the 498 potential Scopus articles were found relevant for review, but four of these had already been identified (Brewer & Sparkes, 2011; Donnelly, 1999; Lund et al., 2009; Ong et al., 2004). Among the three new ones, one study focused on birth and grief expressions revealed in Instagram hashtags (Leaver & Highfield, 2018). Another study focused directly on the benefits of humor to aid grieving people (Booth-Butterfield et al., 2014). A third study report was retained as it focused on coping with losses (including the death of loved ones) in later life (Caplan et al., 2005).

SocIndex

Five potential articles for review were identified in the SocIndex database. Three of these were relevant research articles, but all three had previously been identified for review (Brewer & Sparkes, 2011; Cadell, 2007; Leaver & Highfield, 2018). The remaining two articles did not focus on bereavement humor.

Web of Science

Nineteen potential articles for review were identified in the Web of Science database. Four were research articles that had already been identified and retained (Brewer & Sparkes, 2011; Cadell, 2007; Donnelly, 1999; Leaver & Highfield, 2018). The remaining 15 research and theory or non-research articles were not relevant for review, including a previously identified study report that focused on palliative care patients and their personal use of humor as they neared the end of life (Langley- Evans & Payne, 1997).

Discussion of Findings across the Reviewed Research Articles

General Overview of Research

In total, 11 research articles were identified for review. Five of these 11 studies were qualitative in nature. Four others were quantitative in nature and two involved mixed-method approaches, where both qualitative and quantitative methods were used to gather and analyze the research data. As shown in Table 1, these 11 articles were published in the years 1997 through 2014, with 2 published in 2010. No escalation of interest in the topic of post-death bereavement humor was thus evident. Moreover, as no recent publications were found, this suggests that research and perhaps also clinical practice or lay attention has shifted away from bereavement humor. It is also possible though that the multi-year pandemic we are living through could increase societal use of and also research attention to humor.

The 11 research investigations conducted in whole or in part on bereavement humor were carried out in 5 developed countries; 6 studies having been done in the USA, 2 in Australia, and 1 each in England, Canada, and Ireland. Although not shown in the Table, the identified and noted non-research or theory articles were written by authors residing in these and a few other developed or developing countries. It is possible that additional studies have been conducted in other countries and the findings displayed in journals that do not use English language reporting. As such, post-death bereavement humor may be a worldwide social support and grief recovery consideration, although cultural differences are likely. This conclusion is supported by the view of Michel (2017), a humor expert, who advised that all human cultures have engaged in laughter and they continue to do so. However, what would be appropriate humor, particularly in various post-death scenarios, is likely to vary considerably across and even among cultural groups, as indicated by the findings of Lund et al. (2009), where black Americans differed in relation to bereavement humor from Americans with other ethnic or racial backgrounds.

Prevalence or Incidence Humor Findings

As illustrated in Table 1, humor was often identified as being commonly employed by bereaved people (Cadell, 2007). Lund et al.’s (2009) study of 292 recently-bereaved Americans aged 50 and older revealed a daily humor incidence of 75%. Similarly, Ong et al.’s (2004) American study showed daily positive emotions, including humor, were common among bereaved people in the first three months following the death of their spouse. A study conducted in Ireland also found bereaved Irish people commonly used humor after a death had occurred (Donnelly, 1999).

Not all studies established post-death bereavement humor as common, however. A large-scale Australian study found only 17% of survey responses to a question about what people do to help themselves in tough times (including the death of a loved one) illustrated positive emotional or philosophical strategies such as humor (Taylor et al., 2010). Another Australian study revealed that only “some” posted images of funerals and other post-death events had humor depicted in them in one form or another. Moreover, a USA study found only 1% of diary journal entries written over a 3-day period by older bereaved people could be classified as humorous (Caplan et al., 2005). The design of these studies may not have served to reveal or showcase bereavement humor, as compared to other research methods that highlight any types or instances of bereavement humor.

Additional differences in the use of humor were noted across the 11 reviewed research reports. For instance, a study in the USA established that post-death bereavement humor was more commonly employed by Black and Caucasian Americans than Americans with Asian, Latino, or Pacific Island backgrounds (Lund et al., 2009). Another American study found humor was more commonly used by grieving males than grieving females (Booth-Butterfield et al., 2014). Two additional American studies found bereavement humor was more commonly present when a death was expected as compared to sudden and unexpected (Kanacki, 2010; Lund et al., 2009). The findings from these four studies were all gained in the USA but they raise the possibility that humor differences related to race or culture, gender, and other influential factors exist in that country and in other countries. Moreover, they demonstrate that there is no universal appreciation of bereavement humor, which raises the issue that bereavement humor could be inappropriate and unhelpful at times.

Reasons for and Impact of Humor Findings

Table 1 outlines some reasons for the employment of bereavement humor, as well as some intended or identified impacts of bereavement humor. Two studies showed humor can reveal the grieving person is not unduly stressed or distressed (Brewer & Sparkes, 2011; Keltner & Bonanno, 1997). Two other studies showed humor can be a signal from the grieving person to other people that they have no need for support or for help (Keltner & Bonanno, 1997; Leaver & Highfield, 2018). Similarly, two studies revealed that when bereaved people use humor, this can be understood by others as meaning they are coping well in their grief (Leaver & Highfield, 2018; Ong et al., 2004). More commonly, post-death humor was found to be a signal that the bereavement grief is resolving or has already resolved (Booth-Butterfield et al., 2014; Cadell, 2007; Keltner & Bonanno, 1997). In contrast, two studies revealed humor can indicate that one’s grief is severe; with humor a signal of distress for other people to recognize (Leaver & Highfield, 2018), and to realize that the grieving person needs help (Keltner & Bonanno, 1997). As such, it is clear that bereavement humor is not a simply executed or simple to understand activity.

Yet, bereavement humor may be useful at times. One study found humor was used by bereaved people to avoid difficult topics or discussions with other people and to distance themselves from their own grief (Brewer & Sparkes, 2011). Humor was also deliberately used at times to keep a discussion from becoming too serious or hurtful (Brewer & Sparkes, 2011). Humor was thus identified as a technique that allowed bereaved people to temporarily avoid their grief and help them with the longer-term management of their grief (Brewer & Sparkes, 2011). Moreover, other people around them could use humor to avoid distressing the bereaved person (Brewer & Sparkes, 2011).

Humor Was Identified as Beneficial

All of the 11 reviewed research reports identified humor as a beneficial or positive activity. In addition to what was reported above as positive, three studies found humor could reduce anxiety and distress, and help to prevent physical illnesses or depression arising from severe or prolonged grief (Booth-Butterfield et al., 2014; Lund et al., 2009; Ong et al., 2004). Two additional study reports revealed bereavement humor was a way to build or strengthen relationships (Brewer & Sparkes, 2011; Keltner & Bonanno, 1997). Humor was also found to be a way of restoring the dignity of grieving people (Cadell, 2007), and to remember and honor the deceased person (Keltner & Bonanno, 1997). Moreover, humor was identified through three studies as a way of life that was in accordance with community values, including those arising from an historical closeness to death and dying which fostered a cultural or societal openness about death and dying (Donnelly, 1999; Leaver & Highfield, 2018; Lund et al., 2009). It is also notable that no unhelpful or negative aspects of bereavement humor were identified.

Review Limitations and Implications

Although this literature review found more theoretical and other non-research articles on the topic of bereavement humor than research articles, 11 research reports were located for review. Although the findings from these 11 studies generally demonstrate the importance of humor and the relevance of humor as an externally applied or personally-used grief intervention, the small amount of research on this topic is surprising. At this point in time, bereavement humor appears to comprise a largely unrecognized consideration for use by bereaved people and by their family members and friends; as well as grief/bereavement, hospice/palliative, gerontological/geriatric, and other care providers or researchers. The exception, perhaps, is Ireland, where humor was identified as a cultural icon; a socially-accepted way of acknowledging and living openly with death, dying, and bereavement (Donnelly, 1999). However, social customs are not static and so it is possible that the use of bereavement humor could have changed in the two decades since the Donnelly (1999) study was carried out.

One possible explanation for such a limited amount of research on bereavement humor is that only a few researchers over the years appear to have realized the importance of focusing on bereavement humor to either validate it or conversely to demonstrate when or how it is not useful and should therefore be avoided. This research gap could be a result of humor being widely viewed as inappropriate when people are suffering, such as when they are grieving the death of a loved one. Another limitation with our review is that we only sought English-language articles, which meant we did not capture what may be highly important international research studies and so did not gain additional multi-cultural views on bereavement humor. Regardless, with only 11 English-language published research reports appearing in the last quarter century, many researchers in recent decades, and certainly the last decade (as no recent publications were identified), do not appear to have been oriented to humor as being a readily accessible, inexpensive, and perhaps highly useful and reliable form of support for grieving people. Nor does it appear that there is much recognition that humor could be and perhaps is deliberately used by grieving people to help themselves or others.

Regardless, some evidence exists that bereaved people, family members, friends, and care providers use bereavement humor for a number of valid reasons, such as to reduce anxiety and depression, and also the physical, social, emotional, or mental sequelae of impactful long-term bereavement grief. This reveal demonstrated that bereaved people use humor for their own benefit, and they also use humor to reassure and support other people. As such, bereavement humor was identified as having potential positive effects. It is of concern though that the research to date is entirely lacking in relation to identifying, describing, and explaining inappropriate or unhelpful bereavement humor. Insights need to be gained so it is understood when and why bereavement humor should not be attempted. Research is also needed to highlight individual and other differences in the acceptability of bereavement humor, including cultural differences to ensure that humor findings from one country or ethnic group are not applied generally in the development of educational products or bereavement services and support programs.

Conclusion

This scoping literature review revealed grieving people can and do use humor, and that humor is employed to help bereaved people. Moreover, the findings indicate humor in the form of laughter, jokes, comedy, and other forms of levity may help people who are grieving. However, as this multi-database literature review only identified 11 published research reports that focused over the last quarter century in whole or in part on post-death bereavement humor, it must be recognized that minimal evidence was gained to solidify an understanding of the extent of bereavement humor use, identify common and less common roles of humor in post-death bereavement processes, determine what is appropriate versus inappropriate humor, and identify when humor is appropriate and when it is not. Research is thus needed to more clearly determine what types, when, and if humor is a safe and effective form of support to help bereaved people. It is possible that humor could be used more often to support grieving people and that bereaved people should be encouraged to use humor. Although no negative implications or impacts of humor were noted in the 11 reviewed research articles, future research needs to focus on this concern. Humor should never be considered a benign bereavement approach that can be broadly applied.

Acknowledgements

The authors appreciate the researchers and the writers who have contributed to an understanding of the value of bereavement humor.

Authors’ Contributions

DW – 1,2,3,4; KB – 2,3,4; AMC – 2,3,4; MK – 2,3,4; BEI – 1,2,3,4.

Data availability

Not applicable.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Declaration

Ethics Approval

Ethical approval was waived by the local Research Ethics Committee of the University of Alberta as this is a review of published literature.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Competing Interests

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication

All authors: 1) made substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data; or the creation of new software used in the work; 2) drafted the work or revised it critically for important intellectual content; 3) approved the version to be published; and 4) agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Donna M. Wilson, Email: donna.wilson@ualberta.ca

Kathleen Bykowski, Email: kbykowsk@ualberta.ca.

Ana M. Chrzanowski, Email: ana.chrzanowski@albertahealthservices.ca

Michelle Knox, Email: michelle.knox@ualberta.ca.

Begoña Errasti-Ibarrondo, Email: meibarrondo@unav.es.

References

- Abeles N, Victor TL, Delano-Wood L. The impact of an older adult’s death on the family. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2004;35(3):234–239. doi: 10.1037/0735-7028.35.3.234. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology. 2005;8(1):19–32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong R, Hall BJ, Doyle J, Waters E. ‘Scoping the scope’ of a Cochrane review. Journal of Public Health. 2011;33(1):147–150. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdr015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baik S, Lee D-Y. The effects of laughter therapy on perceived health status and helplessness in the elderly. International Journal of Applied Engineering Research. 2014;9(21):8399–8406. [Google Scholar]

- Basu, S. (2007). “a little discourse pro & con”: Levelling laughter and its puritan criticism. International Review of Social History, 52(SUPPL. 15), 95–113.

- Beach WA, Prickett E. Laughter, humor, and cancer: Delicate moments and poignant interactional circumstances. Health Communication. 2017;32(7):791–802. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2016.1172291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth-Butterfield M, Wanzer MB, Weil N, Krezmien E. Communication of humor during bereavement: Intrapersonal and interpersonal emotion management strategies. Communication Quarterly. 2014;62(4):436–454. doi: 10.1080/01463373.2014.922487. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boots LM, Wolfs CA, Verhey FR, Kempen GI, de Vugt ME. Qualitative study on needs and wishes of early-stage dementia caregivers: The paradox between needing and accepting help. International Psychogeriatrics. 2015;27(6):927–936. doi: 10.1017/S1041610214002804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouchard, L. (2016). Exploring compassion fatigue in emergency nurses [doctoral dissertation. University of Arizona]. A Campus Repository. Retrieved January 18, 2022 from https://hdl.handle.net/10150/622932

- Brass L. Can you cope? How to hang in there--no matter what comes your way. Vibrant Life. 2013;29(1):30–33. [Google Scholar]

- Brewer JD, Sparkes AC. Young people living with parental bereavement: Insights from an ethnographic study of a UK childhood bereavement service. Social Science & Medicine. 2011;72(2):283–290. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadell S. The sun always comes out after it rains: Understanding posttraumatic growth in HIV caregivers. Health & Social Work. 2007;32(3):169–176. doi: 10.1093/hsw/32.3.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caplan SE, Haslett BJ, Burleson BR. Telling it like it is: The adaptive function of narratives in coping with loss in later life. Health Communication. 2005;17(3):233–251. doi: 10.1207/s15327027hc1703_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colin M, Vives J-M. Laughing at ourselves: A study of the contortionist ego. L'Evolution Psychiatrique. 2020;85(3):399–406. doi: 10.1016/j.evopsy.2020.04.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cricco-Lizza R. The need to nurse the nurse: Emotional labor in neonatal intensive care. Qualitative Health Research. 2014;24(5):615–628. doi: 10.1177/1049732314528810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damianakis T, Marziali E. Community-dwelling older adults' contextual experiencing of humour. Ageing and Society. 2011;31(1):110–124. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X10000759. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Donnelly S. Folklore associated with dying in the west of Ireland. Palliative Medicine. 1999;13(1):57–62. doi: 10.1191/026921699675359029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnelly SM, Donnelly CN. The experience of the moment of death in a specialist palliative care unit (SPCU) Irish Medical Journal. 2009;102(5):143–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandi, A., Guidetti, G., Converso, D., Bosco, N., & Colombo, L. (2019). I nearly died laughing: Humor in funeral industry operators. Current Psychology, in press. 10.1007/s12144-019-00547-9

- Grant MJ, Booth A. A typology of reviews: An analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information and Libraries Journal. 2009;26(2):91–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heath-Kelly C, Jarvis L. Affecting terrorism: Laughter, lamentation, and detestation as drives to terrorism knowledge. International Political Sociology. 2017;11(3):239–256. doi: 10.1093/ips/olx007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hussein AT, Aljamili LN. COVID-19 humor in Jordanian social media: A socio-semiotic approach. Heliyon. 2020;6(12):e05696. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e05696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanacki, L. S. (2010). Shared presence: Caring for a dying spouse. Doctoral Dissertation. University of San Diego.

- Kanacki LS, Roth P, Georges JM, Herring P. Shared presence: Caring for a dying spouse. Journal of Hospice & Palliative Nursing. 2012;14(6):414–425. doi: 10.1097/njh.0b013e3182554a2c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Keltner D, Bonanno GA. A study of laughter and dissociation: Distinct correlates of laughter and smiling during bereavement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1997;73(4):687–702. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.73.4.687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidron CA. Embracing the lived memory of genocide: Holocaust survivor and descendant renegade memory work at the house of being. American Ethnologist. 2010;37(3):429–451. doi: 10.1111/j.1548-1425.2010.01264.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Langley- Evans A, Payne S. Light-hearted death talk in a palliative day care context. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1997;26(6):1091–1097. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.1997.tb00800.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leaver T, Highfield T. Visualising the ends of identity: Pre-birth and post-death on Instagram. Information, Communication and Society. 2018;21(1):30–45. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2016.1259343. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK. Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implementation Science. 2010;5(69):1–9. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-5-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu JH, Steele CK. ‘Joy is resistance’: Cross-platform resilience and (re)invention of black oral culture online. Information, Communication & Society. 2019;22(6):823–837. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2019.1575449. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lund DA, Utz R, Caserta MS, de Vries B. Humor, laughter, and happiness in the daily lives of recently bereaved spouses. Omega: Journal of Death and Dying. 2009;58(2):87–105. doi: 10.2190/OM.58.2.a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macnab G, Scherfig L. Killing me softly. Sight and Sound. 2003;13(12):24–25. [Google Scholar]

- Marmo J. Using humor to move away from abjection. Qualitative Inquiry. 2010;16(7):588–595. doi: 10.1177/1077800410372606. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Michel, A. (2017). The science of humor is no laughing matter. Retrieved January 18, 2022 from https://www.psychologicalscience.org/observer/the-science-of-humor-is-no-laughing-matter

- Mir M, Cots JM. The use of humor in Spanish and English compliment responses: A cross-cultural analysis. Humor. 2019;32(3):393–416. doi: 10.1515/humor-2017-0125. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moayedoddin B, Markowitz JC. Abnormal grief: Should we consider a more patient-centered approach? American Journal of Psychotherapy. 2015;69(4):361–378. doi: 10.1176/appi.psychotherapy.2015.69.4.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munn Z, Peters MDJ, Stern C, Tufanaru C, McArthur A, Aromataris E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology. 2018;18(1):1–7. doi: 10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nezu AM, Nezu CM, Blissett SE. Sense of humor as a moderator of the relationship between stressful events and psychological distress: A prospective analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1988;54(3):520–525. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.54.3.520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong AD, Bergeman CS, Bisconti TL. The role of daily positive emotions during conjugal bereavement. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2004;59(4):P168–P176. doi: 10.1093/geronb/59.4.P168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polimeni J, Reiss JP. The first joke: Exploring the evolutionary origins of humor. Evolutionary Psychology. 2006;4(1):347–366. doi: 10.1177/147470490600400129. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pype K. Funeral comedies in contemporary Kinshasa: Social difference, urban communities and the emergence of a cultural form. Africa. 2015;85(3):457–477. doi: 10.1017/S0001972015000224. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ramesh N, Ashok A, Varsha C, Ram N. Use of humour in orthopaedic teaching. Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research. 2011;5(8):1618–1623. [Google Scholar]

- Shifman L, Lemish D. Between feminism and fun(ny)mism. Analyzing gender in popular internet humor. Information, Communication & Society. 2010;13(6):870–891. doi: 10.1080/13691180903490560. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Soares J. Dead woman pickney: A memoir of childhood in Jamaica. Caribbean Quarterly. 2011;57(2):131–133. [Google Scholar]

- Sosa C. Humour and the descendants of the disappeared: Countersigning bloodline affiliations in post-dictatorial Argentina. Journal of Romance Studies. 2013;13(3):75–87. doi: 10.3167/jrs.2013.130307. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor M, Barr M, Stevens G, Bryson-Taylor D, Agho K, Jacobs J, Raphael B. Psychosocial stress and strategies for managing adversity: Measuring population resilience in New South Wales, Australia. Population Health Metrics. 2010;8:28. doi: 10.1186/1478-7954-8-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thumala D, Gajardo B, Gomez C, Arnold-Cathalifaud M, Araya A, Jofre P, Ravera V. Coping processes that foster accommodation to loss in old age. Aging & Mental Health. 2020;24(2):300–307. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2018.1531378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres JM, Collantes LM, Astrero ET, Millan AR, Gabriel CM. Pandemic humor: Inventory of the humor scripts produced during the COVID-19 outbreak. Asian EFL Journal. 2020;27(31):138–164. [Google Scholar]

- Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O'Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., …., Straus, S. E. (2018). PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(7), 467–473. 10.7326/M18-0850. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Warner-Garcia S. Laughing when nothing’s funny: The pragmatic use of coping laughter in the negotiation of conversational disagreement. Pragmatics. 2014;24(1):157–180. doi: 10.1075/prag.24.1.07war. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Warren C, McGraw AP. Differentiating what is humorous from what is not. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2016;110(3):407–430. doi: 10.1037/pspi0000041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittemore R, Knafl K. The integrative review: Updated methodology. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2005;52(5):546–553. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03621.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willett C, Willett J. The comic in the midst of tragedy's grief with Tig Notaro, Hannah Gadsby, and others. The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism. 2020;78(4):535–546. doi: 10.1111/jaac.12765. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson DM, Cohen J, MacLeod R, Houttekier D. Bereavement grief: A population-based foundational evidence study. Death Studies. 2018;42(7):463–469. doi: 10.1080/07481187.2017.1382609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, D. M., Darko, E. M., Kusi-Appiah, E., Roh, S. J., Ramic, A., & Errasti-Ibarrondo, B. (2020). What exactly is “complicated” grief? A scoping research literature review to understand its risk factors and prevalence. Omega, 30222820977305. Advance online publication. 10.1177/0030222820977305 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Wilson DM, Errasti-Ibarrondo B, Rodriguez-Prat A. A research literature review to determine how bereavement programs are evaluated. Omega – Journal of Death and Dying. 2019;68(4):347–366. doi: 10.1177/0030222819869492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World International Laughing Championship. (2021). Retrieved March 31, 2022 from https://www.worldlaughingchamptionship.com/

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Not applicable.