Abstract

Outbreaks of zoonotic diseases are accelerating at an unprecedented rate in the current era of globalization, with substantial impacts on the global economy, public health, and sustainability. Alien species invasions have been hypothesized to be important to zoonotic diseases by introducing both existing and novel pathogens to invaded ranges. However, few studies have evaluated the generality of alien species facilitating zoonoses across multiple host and parasite taxa worldwide. Here, we simultaneously quantify the role of 795 established alien hosts on the 10,473 zoonosis events across the globe since the 14th century. We observe an average of ~5.9 zoonoses per alien zoonotic host. After accounting for species-, disease-, and geographic-level sampling biases, spatial autocorrelation, and the lack of independence of zoonosis events, we find that the number of zoonosis events increase with the richness of alien zoonotic hosts, both across space and through time. We also detect positive associations between the number of zoonosis events per unit space and climate change, land-use change, biodiversity loss, human population density, and PubMed citations. These findings suggest that alien host introductions have likely contributed to zoonosis emergences throughout recent history and that minimizing future zoonotic host species introductions could have global health benefits.

Subject terms: Invasive species, Macroecology, Ecological epidemiology

Alien species invasions are thought to be important to zoonotic diseases through the introduction of both existing and novel pathogens to invaded ranges. Using data from 795 established alien animals and 10,473 zoonosis events worldwide, this study examines the role of alien zoonotic hosts on zoonosis emergences after accounting for climate, propagule pressure, global change and sampling bias.

Introduction

The rapid increase in zoonotic diseases (i.e., diseases caused by pathogens that are spread from animal to people, also known as zoonoses) poses a significant threat to the global economy, public health, and social stability1,2. Positive associations between alien animal host invasions and the incidence of zoonosis has long been of concern3–6, especially given recent increases in both alien species introductions7 and zoonoses, such as avian influenza, SARS, and COVID-198–11. Established alien species can contribute to zoonosis by increasing the abundance of existing pathogens and introducing novel pathogens12,13. In addition, most alien animal introductions are associated with human activities such as pet trade and aquaculture that may provide more contact opportunities between alien hosts and humans8. In recent years, there have been increasing reports linking alien host species with zoonoses. For example, invasive rats have contributed to the emergence of plague, murine typhus, scrub typhus, leptospirosis, and hantavirus hemorrhagic fever throughout the world14, introduced North American raccoons contributed to the emergence of West Nile virus and human roundworm infections in Europe15, the spread of alien mosquitos in Europe contributed to the emergence of chikungunya and dengue fever16, and alien lice and flea vectors have fomented epidemics of typhus and plague in established ranges13. Although these individual examples provide striking geographical and taxonomic evidence of the transmission of zoonoses by alien hosts6, there has not previously been a global synthesis of the role of established alien zoonotic hosts on zoonoses across a broad range of taxonomic groups.

Animal invasions and zoonosis emergences are often correlated with many cofactors, such as propagule pressure (a composite measure of the number of individuals released into a region)17; other global change factors, such as climate change18, biodiversity loss19, and land-use change20; human population density1; and disease and invasive species surveillance and research efforts21. However, few studies at the global scale, across host and parasite taxa, have controlled for these various cofactors to better isolate the unique contribution of established alien host species to zoonoses, hindering the development of effective regulations for alien species introductions and public health.

To address this knowledge gap, we use a global database of 10,473 zoonosis events since the year 1348 (compiled with the assistance of GIDEON)22 and evaluate the role of established alien zoonotic hosts on the number of zoonosis events across the globe, controlling for propagule pressure factors (non-zoonotic host introductions and human population density), climate (global environmental stratification, GenS), global change processes (climate change, land-use modification and biodiversity loss), native biodiversity, sampling effort (country surveillance capacity and reporting bias), and spatial autocorrelation (longitude and latitude of the geographic centroid of each administrative area) (Fig. 1). Importantly, a correlation between zoonosis events and zoonotic alien hosts might just be a product of areas with high propagule pressure having more introductions of both hosts and pathogens13,17. To address this potential issue, we first conduct an intensive literature review to identify each established alien species as a zoonotic or non-zoonotic host species. We then include non-zoonotic alien host richness as a positive control for propagule pressure that cannot directly increase zoonosis emergences. Thus, a significant effect of zoonotic alien host introductions on the number of zoonosis events when controlling for the number of non-zoonotic alien host introductions (and other covariates) would provide an estimate of the causal effect of established zoonotic alien host species on zoonosis independent of propagule pressure. Given that taxonomic groupings within classes of hosts can vary in contributions to zoonoses6,23–25, we also conduct additional analyses to identify which alien taxonomic groups seem to contribute most to past zoonosis events. Moreover, a correlation between alien species invasions and zoonosis events in space may be spurious if the disease occurred earlier than the alien animal arrivals. Therefore, we also conduct analyses to explore the relationship between species invasions and zoonosis events through time. Finally, we generate a global map showing where historical zoonoses were likely most influenced by alien host introductions, which might provide helpful insights into our understanding on the potential effects of alien animal invasions on future zoonosis emergences.

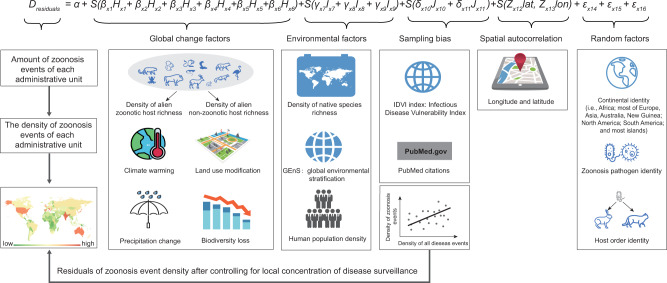

Fig. 1. Analysis diagram to estimate the effect of alien animal invasions on zoonosis emergences at the global scale.

The role of alien animal zoonotic hosts was determined by accounting for global change factors (Hx1-x6), environmental factors (Ix7-x9), sampling bias (Jx10,11), spatial autocorrelation (Llat, lon), and a lack of independence among zoonoses by treating pathogen, host order and continent as random factor intercepts (εx14-x16). Thin-plate spline smooths for each predictor variable are designated by S(), and α, β, γ, δ, and Z are constants (α is an intercept and β, γ, δ and Z represent the coefficient estimates of different predictor variables, and ε represents the random effects). Silhouettes were freely obtained from “islide” plug-in (https://www.islide.cc).

Here, after controlling for other variables, we show that number of zoonosis events increase with the richness of alien zoonotic hosts across mammalian (particularly three orders: Artiodactyla, Carnivora, and Rodentia), birds (particularly waterfowl, Galliformes, and Passeriformes), and Dipteran invertebrate host species both across space and through time. Importantly, we do not observe a significant effect of the alien non-zoonotic host species, indicating that our findings on the correlation between the number of zoonosis events and the number of zoonotic alien hosts are unlikely to be a byproduct of areas with high propagule pressure having more introductions of both hosts and pathogens.

Results

Global patterns of historical zoonoses and established alien zoonotic hosts

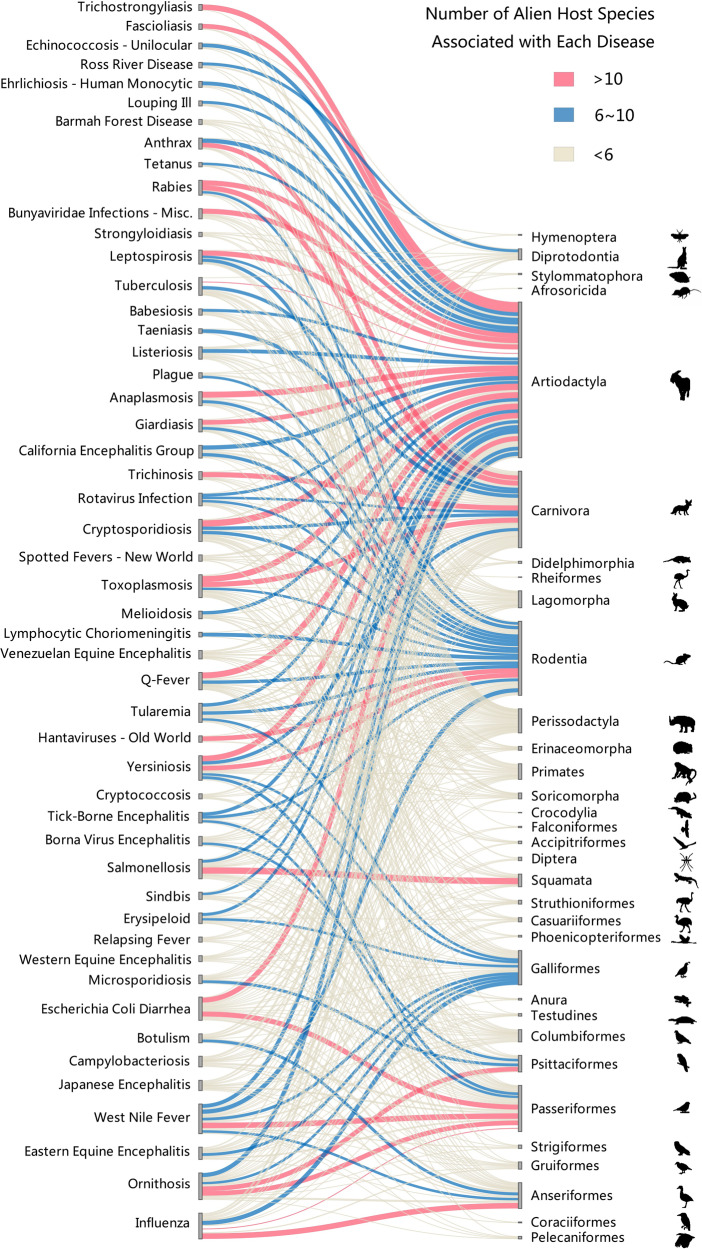

As alien species may carry both existing and novel pathogens and transmit them to local native species that can transmit them to humans6, our analyses included events caused by both re-emerging and novel zoonoses in each of a total of 201 countries or regions worldwide (Supplementary Data 1). Of the 10,473 events for 161 zoonoses reported from 1348 to 2020, 2970 events were caused by emerging diseases introduced to a new administrative unit and 7503 events were caused by re-emerging diseases that had been reported before. Overall, these zoonoses were most often associated with mammalian hosts, followed by avian, invertebrate, and herpetofaunal hosts (Supplementary Fig. 1A, Supplementary Data 2–4, note that some diseases may be carried by multiple host taxa). To calculate the number of zoonosis carried by the alien zoonotic hosts, we first obtained a total of 93,544 pathogen-alien host records from an intensive literature and database review (Supplementary Data 2). Using these records, we determined that at least 35.6% (283/795) of established alien animals are zoonotic hosts of one or more zoonoses and there is an average of 5.9 (±0.58, average ±S.E.) zoonoses per alien zoonotic host (Supplementary Data 3). The number of zoonoses varied among alien host taxa (Fig. 2), which was predominated by alien mammalian zoonotic hosts, especially from orders Artiodactyla (17.5 ± 3.70), Carnivora (12.2 ± 3.13), and Rodentia (8.9 ± 1.97), and by alien avian hosts, especially from waterfowl (4.1 ± 0.78), Galliformes (3.8 ± 1.05), and Passeriformes (2.5 ± 0.36), and by alien Dipterans (5.0 ± 0.58) for invertebrate-hosted zoonoses (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Associations between the zoonotic diseases reported by the GIDEON database and alien zoonotic hosts.

Bipartite network analysis shows the relatedness between the top 50 zoonoses with the largest number of alien zoonotic host species and the alien zoonotic host orders. The exact number of zoonotic diseases per alien zoonotic host is provided in Supplementary Data 3. Width indicates the number of zoonotic diseases carried by alien zoonotic host species in each order. The order of figure column is based on the default output of the R software to minimize the number of crossovers. Animal silhouettes were obtained from PhyloPic.

These zoonosis events most often occurred in Europe (3495 events), followed by Asia (2180), North America (2120), Africa (1301), South America (897) and Oceania (480, Supplementary Fig. 1B). In general, these zoonosis events were concentrated in higher latitudes, such as the United States and Western Europe (Supplementary Fig. 2). Across pathogens, zoonoses were largely caused by bacteria (4622) and viruses (4002), followed by parasitic animals (1621) and fungi (225, Supplementary Fig. 1B).

Spatial relationship between alien animal invasions and zoonotic diseases

We next used generalized additive mixed models (GAMMs) to examine the relationship between the number of zoonotic alien host species and zoonosis events in a region controlling for sampling efforts at species-, disease - and geographic-levels, administrative region size, alien non-zoonotic host introductions (i.e., propagule pressure control), and various other covariates, while treating continent (i.e., human settlement history), host order, and pathogen identity as random intercepts (to control for the lack of independence associated with these factors; Fig. 1). We applied Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) to select the most highly supported models (i.e., ΔAIC ≤ 2).

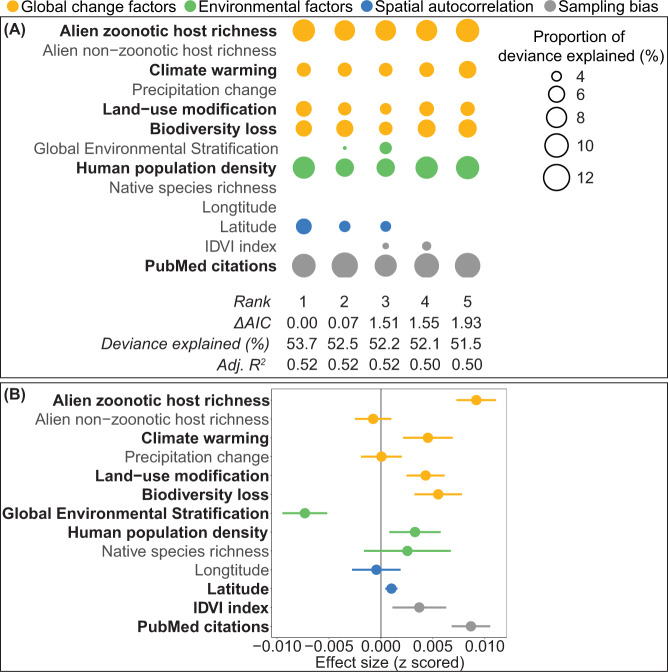

There were six variables that appeared in the top five most supported models: alien zoonotic host richness, human population density, biodiversity loss, temperature change, land-use change, and PubMed citations (Fig. 3A). The 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of the coefficients for these six predictors also did not overlap with zero in any model (Fig. 3B). In addition to alien host richness, human population size and PubMed citations explained the highest percentages of deviance in the number of zoonosis events, followed by the three global change factors (Fig. 3A). Most variables had nonlinear but generally positive relationships with the number of zoonosis events after accounting for other cofactors (Fig. 4). Although it was only included in three of the top five models, the latitude of a country was also a significant predictor of zoonosis events (Fig. 3A), with zoonosis events being more common in higher latitudinal areas (Supplementary Fig. 2). These results were independent of whether we used 10, 8, or 6 knots in the GAMM analyses (Supplementary Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Proportion of deviance explained and effect size of each predictor variable in model averaging analyses based on GAMMs.

Columns represent individual models and rows represent predictor variables, with smoothing function knot value = 10. Shown in bold are the variables that appear in all five of the most highly supported models in panel A and that have model-averaged 95% confidence intervals that do not overlap zero in panel B. The circle size in panel A represents the proportion of deviance explained by each predictor and any blanks indicate that the predictor is not included in the model. The panel B represents mean effect sizes with 95% confidence intervals of different predictor variables explaining the number of zoonosis events worldwide (n = 10,473, Supplementary Data 4).

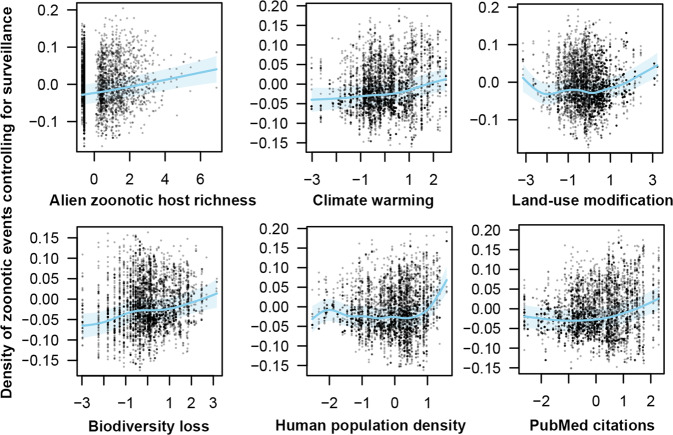

Fig. 4. Relationships of the six most important predictor variables with zoonosis emergences in the five highly supported models.

Scatter plots represent the partial residuals of each smoothed variable when controlling for other variables. Blue lines show the predicted function of each variable with mean and the shaded area as the 95% confidence band based on GAMMs. The dependent variable (zoonosis event density) is treated as the residuals of the fitted regression correlating the density of zoonosis events and the density of all disease events to account for the degree of overall disease surveillance (Supplementary Data 4). All predictor variables were standardized (to a mean of zero and standard deviation of one) before entering the model.

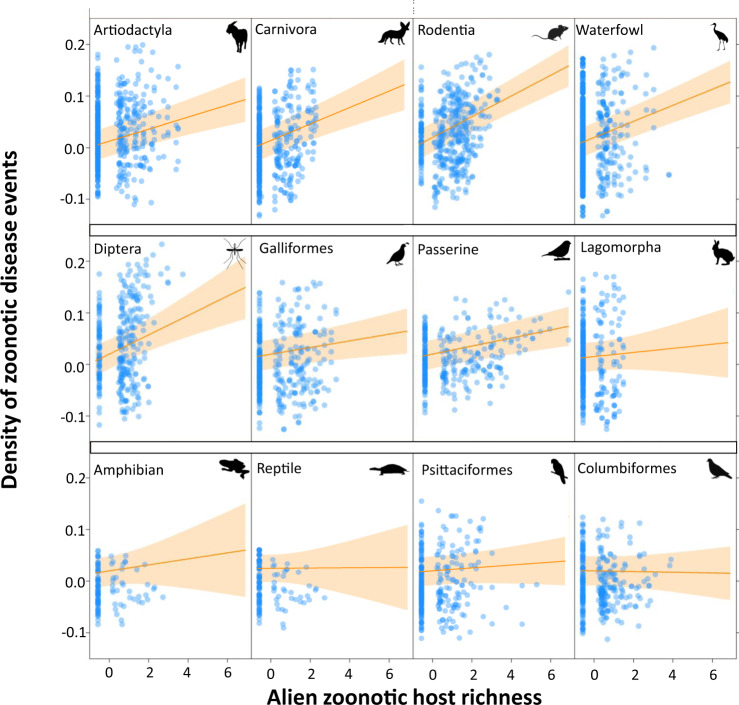

Next, we added to the model an interaction between host order and alien zoonotic host richness to test whether certain orders were more important contributors to emergences of zoonoses. The effects of alien zoonotic host richness for three mammalian orders (i.e., Carnivora, Effect size ± S.E.: 0.0150 ± 0.0028, P < 0.001; Artiodactyla, 0.011 ± 0.0023, P < 0.001; and Rodentia, 0.0197 ± 0.0021, P < 0.001), three avian groups (i.e., waterfowl, 0.0149 ± 0.0022, P < 0.001; Galliformes, 0.0059 ± 0.0024, P = 0.0134; and Passeriformes, 0.0082 ± 0.0019, P < 0.001), and order Diptera of the invertebrates (0.0151 ± 0.0053, P < 0.01) had significantly stronger associations with zoonosis events than other host groups (Columbiformes, −0.0043 ± 0.0032, P = 0.891; Lagomorpha, 0.0033 ± 0.0045, P = 0.462; Psittaciformes, 0.0027 ± 0.0028, P = 0.327; amphibians, 0.0061 ± 0.0062, P = 0.326; reptiles, 0.0007 ± 0.006, P = 0.902, Fig. 5).

Fig. 5. The relationship of alien zoonotic animal richness and the zoonosis emergences across alien host groups.

The strength of each host group is tested by including an interaction between the richness of alien zoonotic species with each of the 12 host orders identified as important in the GAMMs after accounting for other co-factors. Each host order had established alien populations in at least 50 administrative units. Lines show the predicted relationship between density of zoonotic disease events and alien zoonotic host richness, with mean and the shaded area as the 95% confidence band (Supplementary Data 4). All predictor variables were standardized (to a mean of zero and standard deviation of one) before entering the model. Animal silhouettes were obtained from PhyloPic.

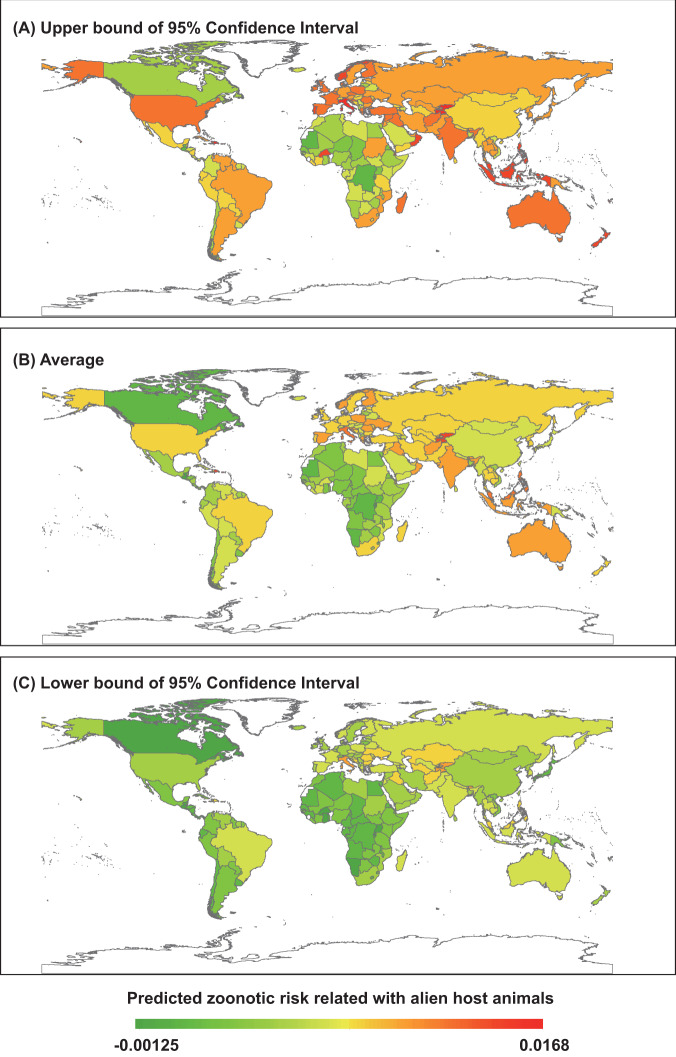

Finally, we plotted the estimated contribution of alien zoonotic host introductions to historical zoonosis events for each administrative unit globally predicted by the GAMMs with and without the alien zoonotic host (Fig. 6). This map suggests that zoonosis hotspots due to past alien zoonotic host introductions were most concentrated in Europe, Oceania, and the Caribbean islands (Fig. 6), which is largely consistent with the global hotspots of alien animal establishment26.

Fig. 6. Global map showing the potential contribution of alien zoonotic host introductions to zoonosis events of each administrative area at the global scale.

Maps are derived for predicted zoonosis events caused by alien host species and the relative risk is calculated by subtracting the GAMM fitted values excluding the zoonotic host introduction from those using all predictor variables in Supplementary Data 4.

Temporal relationship between alien animal invasions and zoonotic diseases

To verify that there was a positive association between alien host introductions and zoonosis events through time, we first conducted a multiple regression analysis where we treated year as the replicate, the number of zoonotic diseases as the dependent variable, and the number of zoonotic and non-zoonotic alien introductions as the independent variables. Model averaging analyses of the generalized additive models showed that the number of zoonosis events through time was positively correlated with the number of alien zoonotic host introductions through time (Estimate = 3.04, 95% CI = 2.23~3.85, P < 0.001, Supplementary Fig. 4), but was not correlated with the number of alien non-zoonotic host introductions (Estimate = 0.62, 95% CI = −0.69~1.94, P = 0.345). In addition, we also conducted breakpoint regression analyses to evaluate whether the breakpoints (when there is a sharp change in a response variable in time) for zoonosis events and introductions of zoonotic and non-zoonotic alien hosts tended to coincide in time. The number of zoonosis events increased sharply in 1962 (i.e., a breakpoint based on AICc), just two years after alien zoonotic host introductions sharply increased in 1960 (Supplementary Fig. 5A, B). In contrast, the breakpoint for non-zoonotic alien hosts was in 1948 (Supplementary Fig. 5C), which was far from the zoonosis breakpoint in 1962.

Discussion

The present study, to the best of our knowledge, provided the first comprehensive global evaluation of the relationship between alien species invasions and zoonotic disease emergences. Our literature and database review showed a high diversity of zoonoses with an average of ~5.9 diseases per alien zoonotic hosts. This is likely an underestimate as our criteria for zoonotic alien hosts were highly conservative (Supplementary Data 2). Given taxonomic and geographic biases in zoonosis sampling, there might be many unknown zoonotic hosts that have not yet been reported or studied27,28. Despite this, we tried to account for potential sampling biases in disease surveillance efforts and which species and geographic locations were studied to increase the robustness of our findings. We encourage future studies to further support or refute our findings with more zoonoses and host discoveries.

Consistent with our hypothesis, we showed that the richness of alien zoonotic hosts was indeed an important factor determining the number of zoonosis events. Comparatively, we did not find an important effect of the richness of non-zoonotic host on the emergence of zoonoses (Fig. 3), demonstrating that the correlation of zoonosis events with alien zoonotic hosts was not simply a by-product of anthropogenic-related propagule pressure. We also detected a close temporal relationship between zoonosis emergences and alien zoonotic host introductions. These results corroborate the spatial patterns and further bolster the hypothesis that alien species invasions have contributed to the increase of zoonosis events over the last sixty years.

Our study illustrated that alien species in certain mammalian orders, such as Carnivora, Artiodactyla, and Rodentia, were significantly associated with zoonosis events. This result is consistent with previous studies showing that mammalian orders Carnivora, Artiodactyla, and Rodentia are strongly associated with zoonotic diseases23,25. Orders Chiroptera and Primates were also previously shown to be associated with human zoonotic diseases23,25, but they were not included in our analyses because there are too few alien species from these orders. Many mammals have a predilection for human-dominated environments29,30 and are closely related to humans phylogenetically, both of which can facilitate spillover probabilities23. Within class Aves, there were significant associations between alien zoonotic host species introductions and zoonotic diseases for waterfowl (including five orders: Anseriformes, Gruiformes, Pelecaniformes, Phoenicopteriformes, Suliformes), and orders Galliformes and Passeriformes, but not Columbiformes and Psittaciformes (Fig. 5). Consistent with these findings, alien waterfowl can be carriers of cryptosporidiosis, giardiasis, and microsporidiosis8, and a recent global study showed that passerine species were highly associated with human-disturbed habitats, which may increase the probability of passerine-related zoonosis events30. We found that the invertebrate zoonoses were dominated by Dipteran-hosted diseases. As examples, the rapid expansion of Aedes and Anopheles mosquitoes has resulted in the worldwide transmission of various diseases, such as malaria, yellow fever, dengue, chikungunya and lymphatic filariasis31. We did not detect effects of alien herpetofauna host species on zoonotic diseases consistent with there only being a few zoonoses shared by humans and herpetofauna32 and the considerable physiological differences between herpetofauna and humans. Nevertheless, we suggest that the potential zoonotic risks from alien reptiles and amphibians should not be overlooked given continued alien reptile and amphibian introductions33 and an increasing frequency of direct contacts between herpetofauna and humans through the pet trade and aquaculture32.

Our analyses also unsurprisingly unveiled that human population density was positively associated with zoonotic diseases. Countries with higher human population densities may be likely to host more zoonoses, which has long been observed by epidemiologists1. Consistent with past studies21,34, we detected positive associations between the number of zoonosis events and both anthropogenic land-use transformation and changing temperatures. Anthropogenically influenced habitats can lead to more human-wildlife contacts that can facilitate spillover of zoonoses from wildlife to humans30. Similarly, insect vector-borne diseases can be favored in human-disturbed habitats where opportunities for human contact can increase35. Additionally, habitat modification can create more vacant niches, facilitating establishment of zoonotic host populations36. Changing temperatures can expand the distributional ranges of pathogens, making previously unsuitable regions habitable37, and can accelerate the development and increase the abundance, survival, and transmission rates of reservoir hosts or vectors38. We found that biodiversity loss rather than native host species richness was an important predictor of zoonosis events (Fig. 3), which was consistent with previous studies showing that there was no overall effect of biodiversity on zoonosis emergence at large spatial scales39,40 and that anthropogenic biodiversity loss rather than natural biodiversity gradients was key in driving zoonoses19,41.The important role of PubMed citations in explaining the number of zoonosis events in each administrative region confirmed that controlling for research effort or bias towards particular hosts and pathogens is important for understanding observed spatial patterns of disease1,21,28.

Our results provide quantitative, global, spatial, temporal, and multi-taxonomic evidence supporting the hypothesis that established alien species can promote zoonosis events across the planet. The detected associations between zoonosis events and climate change, land-use change, biodiversity loss, and introduced species also offer a deeper understanding of the potential responses of zoonosis emergences to ongoing global change and might help inform policy and regulatory recommendations targeted at both the control of zoonotic diseases and the mitigation of the effects of global change. The provided global map identifying the likely contribution of introduced species to historical zoonosis events (Fig. 6) offers a decision support tool for directing both surveillance and disease control efforts. Assuming a positive correlation between past and future hubs of zoonotic diseases, the hotspots identified on this map should serve as a preliminary prediction of the locations where future diseases associated with zoonotic host introductions are most likely to occur and where zoonosis surveillance might be most wisely targeted.

Methods

Disease data source

All analyses were conducted at the administrative level, and the exact list of known zoonotic diseases is recorded in the GIDEON database22. GIDEON is currently the most comprehensive and frequently updated infectious disease outbreak database reporting epidemics of human infectious diseases at the global scale and has been widely used in global zoonosis studies42,43 (Last access date, November 9, 2020). The administrative designations used in our analyses were based on the Global Administrative Areas (GADM) database (www.gadm.org, downloaded on November 8, 2020), which includes very detailed boundary data for global countries and major island groups.

Pattern and correlates of zoonosis events worldwide

Number of zoonosis events

GIDEON defines human infectious disease reservoirs as any animal, plant, or substrate supporting the survival and reproduction of infectious agents and promoting transmission to potential susceptible hosts. Its host category therefore includes all human-specific, zoonotic, multihost, and environmental agents. As our main aim was to test the role of established alien animal species in the emergence of zoonotic diseases, we focused on a total of 161 diseases specified in GIDEON’s host designations and definitions as nonhuman zoonotic (n = 115) and multihost (n = 46) diseases (Supplementary Data 1) and excluded diseases with human-specific hosts that do not need animals to persist or be transmitted. The infectious agents of nonhuman zoonotic diseases complete their entire lifecycle in nonhuman hosts but may have the potential to spillover and infect human populations. Infectious agents of multihost diseases can use both human and animal hosts for their development and reproduction. We measured the number of zoonosis events for each jurisdiction according to five host taxonomic groups: mammals, birds, invertebrates, reptiles and amphibians. These zoonoses were mainly caused by bacteria, viruses, parasitic animals and fungi. We excluded zoonoses from the Algae (3 diseases) due to low sample sizes in GIDEON.

Correlates of the number of zoonosis events

Climatic variables

Following a previous study21, we used global environmental stratification (GEnS) as a composite bioclimatic variable generated by stratifying the Earth’s surface into zones with similar climates44. The GEnS database was constructed based on a total of 125 strata across 18 global environmental zones with a spatial resolution of 30 arc seconds (equivalent to approximately 0.86 km2 at the equator). The values in GEnS range from 1 to 18 with a higher value indicating warmer and wetter conditions.

Human population density

We used human population density as one general anthropogenic factor reflecting propagule pressure and human-assisted pathogen movements1,21,45. Human population size data and the land area of each jurisdiction were collected from World Bank Open Data from 2011 to 2020 (available at https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.POP.TOTL, accessed on November 18, 2020). We then calculated the human population density using the human population size divided by the land area.

Native potential host richness and biodiversity loss

Data on the richness of native amphibians, birds, and mammals were derived from the Biodiversity Mapping website (https://biodiversitymapping.org/wordpress/index.php/home/, accessed on August 19, 2020), which were based on studies from Jenkins et al. (2013)’s and Pimm et al. (2014)46,47. The map of reptile diversity is based on an updated database of the global spatial distribution of reptiles48. All diversity maps for each taxon were generated through the calculation of grid-based richness at a spatial resolution of 10 km × 10 km in ArcGIS46. We did not include native invertebrate richness, as global maps for most invertebrate taxa are not yet available. For the loss of native biodiversity, we followed the previous study by first extracting the list of threatened species (NT, EN and VU categories evaluated by the IUCN Red List, access on May 10th, 2021)29, and then calculated the number of threatened species for each taxon distributes in each administrative unite as a proxy of biodiversity loss.

Richness of established alien zoonotic host species

We quantified the richness of established alien animal species from the five main taxonomic groups (mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians and invertebrates) based on 4,522 establishment events of 795 alien animals in each of 201 jurisdictions according to various databases. Data on 262 established alien reptiles and amphibians were compiled from multiple publications, including Kraus’s compendium49 and other recent updates50. Data on 337 established alien birds after removing all migratory bird species as vagrants were collected from the Global Avian Invasions Atlas (GAVIA)51, which is a comprehensive database of the global distribution of established alien birds. Data on 119 established alien mammals were obtained from the Introduced Mammals of the World database52 and the more recent update53. Data on 77 terrestrial alien invertebrates (66 insects and 11 other groups) across 7 taxa with native and invaded range information were obtained from the Global Invasive Species Database (GISD, http://www.iucngisd.org/gisd/, accessed on July 1, 2020). We calculated the richness of both zoonotic and non-zoonotic alien host species for each order. We first conducted an intensive literature review for each established alien species of each of the four taxa to determine whether they transmit pathogens to humans (Supplementary Data 2). The identification of zoonotic or non-zoonotic host may be influenced by under-sampling in the literature. We therefore incorporated the latest synthesis of human-infecting pathogens in the ‘CLOVER’ dataset to identify zoonotic and non-zoonotic animal hosts54. The CLOVER dataset compiled GMPD255, EID256, HP323 and Shaw57 databases and is currently the most comprehensive dataset on host-pathogen associations. Based on this information, we then categorized each alien species as a ‘zoonotic host’ or ‘non-zoonotic host’. The records of the established alien species were assigned to GADM jurisdictions, and we calculated the richness of the established alien zoonotic and non-zoonotic host species for each taxonomic group within each jurisdiction. In order to increase the statistical power, we conducted subsequent modeling analyses based on four mammalian orders (i.e., Carnivora, Cetartiodactyla, Lagomorpha, and Rodentia), five avian groups (i.e., waterfowl including five orders: Anseriformes, Gruiformes, Pelecaniformes, Phoenicopteriformes and Suliformes; Columbiformes, Galliformes, Passeriformes, Psittaciformes), the order Diptera of the invertebrates, and herpetofauna as a whole, which have established alien populations in at least 50 administrative units.

Climate change

We extracted historical monthly mean temperature and precipitation data recorded between 1901 and 2009 from the University of East Anglia Climate Research Unit (CRU, https://sites.uea.ac.uk/cru/, accessed on November 30, 2020)58. This database provides historical global-scale yearly climatic data with the finest resolution of 0.5° grids. We generated the temperature and precipitation values for all grids in each jurisdiction, calculated the slope of the temperature and precipitation for the time series of the years 1901 to 2009 for each grid and generated the averages based on all grids within each jurisdiction.

Anthropogenic land-use change

We downloaded global land-use data from the Anthromes v2 Dataset (Anthropogenic Biomes version 2, accessed on October 15, 2020) in ESRI GRID format59. We used the 1900 and 2000 data to calculate the temporal changes in land use. By using the reclassify and raster function in ArcGIS, we calculated the percentage of grids in which the land-use type changed to a more anthropogenically influenced type from 1900 to 2000 for each jurisdiction, including 15 scenarios: Wildlands to Seminatural, Wildlands to Rangelands, Wildlands to Croplands, Wildlands to Villages, Wildlands to Dense Settlements, Seminatural to Rangelands, Seminatural to Croplands, Seminatural to Villages, Seminatural to Dense Settlements, Rangelands to Croplands, Rangelands to Villages, Rangelands to Dense Settlements, Croplands to Villages, Croplands to Dense Settlements, and Villages to Dense Settlements.

Sampling effort, reporting bias and incomplete data

A potential issue in quantifying the effects of different predictor variables on the number of zoonosis events is the need to account for the differences in survey effort, reporting bias and incomplete disease data among regions1,21,28. There is a high probability that zoonosis discovery is spatially biased by uneven levels of surveillance across countries, as the global allocation of scientific resources has been focused on rich and developed countries. We thus included the Infectious Disease Vulnerability Index (IDVI), which is a comprehensive metric reflecting the demographic, health care, public health, socioeconomic, and political factors that may have an impact on the capacity of surveillance and detection of infectious diseases in each country60. Second, we followed the methods of a previous study21 to control for reporting biases. We incorporated PubMed citations per disease for each jurisdiction using a Python-based PubCrawler21. In addition, we added the longitude and latitude of the geographic centroid of administrative units to control for spatial autocorrelation as there would be a higher probability of having similar diseases in nearby than distant administrative units61.

Statistical analysis

The number of zoonosis events, native potential host richness, established alien animal richness and human population density were log-transformed to improve linearity. A potential issue in our data analysis is that the numbers of zoonosis events and the numbers of native and alien animal species are strongly influenced by geographical area, as larger countries or regions may host more native or alien animal species and more disease events. We therefore calculated the density of native or alien species richness and the number of zoonosis events using the total number divided by the geographical area of each jurisdiction. Furthermore, the number of zoonosis events may also be influenced by the degree of local disease surveillance. We thus obtained the residuals from a regression correlating zoonosis event density and all disease event density, and used them as the dependent variable for further analyses (Fig. 1). As some of our variables may be expected to be nonlinear, we performed generalized additive mixed model (GAMM) analyses following Mollentze & Streicker 2020’s framework25 to quantify the relationships between different predictor variables and the number of zoonosis events. We started with a full model with zoonosis event density controlling for overall disease surveillance as the response variable and 13 smoothed fixed effects (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Data 4): GEnS, human population density, density of native species richness, biodiversity loss, density of alien zoonotic host richness, density of alien non-zoonotic host richness, climate (temperature and precipitation) change, land-use change, IDVI, PubMed citations, longitude and latitude of geographic centroid of administrative units. The reason why we included the density of alien non-zoonotic host richness as a covariate is because this variable can serve as a positive control for propagule pressure, allowing us to more explicitly test whether zoonotic alien hosts contribute to zoonoses beyond propagule pressure associated with non-zoonotic alien hosts, which cannot directly increase zoonotic diseases. These predictor variables were not highly collinear as their correlation coefficients based on Pearson rank correlation analyses were all <0.65 (Supplementary Fig. 6). Because human history may have a great influence on disease outbreaks, as there may be more human pathogens on continents subject to earlier human settlement45, we followed this literature by including continental identity (i.e., Africa, region of origin and first settlements; most of Europe, Asia, Australia, New Guinea, by approx. 40,000–60,000 BP; North America, by approx. 15,000–25,000 BP; South America, by approx. 1000–5000 years after North America, i.e., 10,000–24,000 BP; and most islands, by approx. 1000–7000 BP) as a random intercept to control for potential pseudoreplication. In addition, to account for the lack of complete independence among disease events caused by the same pathogens or associated with the same introduced host orders (Fig.1), we included pathogen identity and host order as two additional random intercepts. We fitted all models using restricted maximum likelihood method and ranked all candidate models by the Akaike’s Information Criterion (AIC) theoretic approach25,62. Models including all possible combinations of the 13 predictor variables (total 213-1 = 8191 models) were ranked, and the models within 2 AIC unites (i.e., ΔAIC ≤ 2) compared with the top model were considered to be highly supported62. For each model, we computed the standardized estimates of the regression coefficients of the predictor variables with the 95% confidence intervals (CIs), and considered effects statistically significant when the 95% CIs did not overlap zero. In addition to variable significance, we also calculated the proportion of the deviance explained by each predictor variable by comparing the sub-models in the absence of the variable to the full model25. To better compare the coefficients of the different covariates, we standardized each of the predictor variables to a mean of zero and standard deviation of one before it was entered into the model63. Furthermore, we used different levels of thin-plate smoothers with 6, 8, and 10 knots for the fixed-effect variables in GAMMs25. As the results were similar regardless of which knot we used, we present the results from the analyses with 10 knots in the main text but provide the results with 6 and 8 knots in the supporting materials (Supplementary Fig. 3). All analyses were conducted in the gamm4, mgcv, visreg, dplyr, and MuMIn packages in R version 4.0.364 (Supplementary Notes).

To further test whether there are different responses of the zoonosis emergences among alien host groups, we fit an interaction between host order and alien species richness to investigate whether the effect of alien zoonotic host richness varied across taxonomic groups. Finally, to evaluate the potential contribution of alien zoonotic host introductions on historical zoonosis events for each administrative unit, we generated the fitted values along with 95% CIs of the number of zoonosis events in each administrative unit predicted by using the predictors in GAMMs, and subtracted the predicted values excluding zoonotic host introductions from those using all predictor variables.

The observed spatial correlation of zoonosis emergences with alien animal invasions might be problematic because there may be mismatch in the occurrence of alien animal invasions and zoonosis events in time. For instance, zoonosis events at a location might have occurred earlier than the alien animal invasions, which could not have caused the disease despite a strong spatial correlation. We therefore further explored the temporal relationship of alien zoonotic (and non-zoonotic) host introductions and zoonotic diseases over years. To achieve this, we collected the introduction time of each alien zoonotic and non-zoonotic host species in each country or region based on the alien avian introduction database and literatures from alien birds51,63, the Introduced Mammals of the World database52 for alien mammals, and the Global Invasive Species Database (GISD) for alien invertebrates. We obtained the number of new zoonosis events over time from the GIDEON database (Last access date, November 9, 2020), and calculated the number of zoonosis events in each year for different taxa. For each year, the number of new zoonosis events divided by the number of alien host introductions for each country or region was used to evaluate the magnitude of the relationship between alien zoonotic host introductions and the number of new zoonosis events. We then used two approaches to analyze their temporal relationships. Firstly, we conducted a generalized additive modeling analysis where we treated year as the replicate, and zoonotic and non-zoonotic alien introductions as the independent variables, and the number of zoonosis events as the dependent variable, to explore the general trend of alien animal host introductions and the number of zoonosis events along time. Additionally, we applied breakpoint regression analyses using the segmented package in R (Supplementary Notes). In these analyses, the identified the breakpoint reflects the year in which there was a rapid increase in the number of zoonotic or non-zoonotic host species or the number of zoonosis events. For these analyses, we fit the left-horizontal regression and two-slope regression that are widely used in ecological and biogeographical studies65, and applied an AIC-based approach to identify the optimal breakpoint year. We combined data across various host taxa for the temporal analyses because some orders had little data on the timing of alien species establishment.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Description of Additional Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32171657, 31870507) to X.L., the Third Xinjiang Scientific Expedition Program (Grant No. 2021xjkk0600) to Y.D., the Youth Innovation Promotion Association of Chinese Academy of Sciences (Y201920), and the Grant of High Quality Economic and Social Development in South Xinjiang (NFS2101) to X.L.

Author contributions

X.L. is the lead contact for this paper. X.L. conceived the project. X.L. and J.R.R. designed the study. X.L. and Q.H. supervised the project. L.Z., R.C., Y.X., X.L., L.H., J.L., X.W., X.Y., and Z.W. collected the data. X.L., L.Z., S.G., and Y.D. performed the data analyses. X.L., J.R.R. and L.Z. wrote the manuscript.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Hamish McCallum and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Data availability

The data used in this study are from existing datasets and are included in Supplementary Data 1-4. The exact list of known zoonotic pathogens and zoonoses at the administrative level is recorded in the GIDEON database (www.gideononline.com) (Last access date, November 9, 2020). The administrative designations used in our analyses are based on the Global Administrative Areas (GADM) database (www.gadm.org, downloaded on November 8, 2020). The alien host-pathogen association data are based on Gibb’s dataset (CLOVER_Associations_Initial.csv, 10.5281/zenodo.4435128) and other literatures in Supplementary Data 2. The Infectious Disease Vulnerability Index (IDVI) is from Moore et al. (2017) (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28845357/). We use global environmental stratification (GEnS, https://www.geoportal.org/) as a composite bioclimatic variable generated by stratifying the Earth’s surface into zones with similar climates. For the temperature and precipitation change variable, we extract historical monthly mean temperature and precipitation data recorded between 1901 and 2009 from the University of East Anglia Climate Research Unit (CRU, https://catalogue.ceda.ac.uk/uuid/3f8944800cc48e1cbc29a5ee12d8542d, accessed on November 30, 2020), and global land-use data from the Anthromes v2 Dataset (Anthropogenic Biomes version 2, https://ecotope.org/anthromes/v2/, accessed on October 15, 2020) in ESRI GRID format. Human population size data and the land area of each jurisdiction are collected from World Bank Open Data from 2011 to 2020 (available at https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.POP.TOTL, accessed on November 18, 2020). Data on the richness of native amphibians, birds, and mammals are derived from the Biodiversity Mapping website (https://biodiversitymapping.org/wordpress/index.php/home/, accessed on August 19, 2020) derived from Jenkins et al. (2013) (10.1073/pnas.1302251110) and Pimm et al. (2014) (https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.1246752). The latest map for the reptile species is from Roll et al. (2017) (10.5061/dryad.83s7k). The list of threatened species evaluated as NT, EN and VU used for calculating the loss of native biodiversity is extracted from the IUCN Red List (http://www.iucnredlist.org, access on May 10th, 2021). The established alien species list and the introduction time information used for the temporal analyses are based on Kraus’s (2009) compendium (https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-1-4020-8946-6_6) and Capinha et al. (2017) (10.1111/ddi.12617) for reptiles and amphibians, the Global Avian Invasions Atlas (GAVIA) (10.6084/m9.figshare.4234850) for established alien birds, Long’s (2003) book (https://ebooks.publish.csiro.au/content/introduced-mammals-world) and Capellini et al. (2015) (10.1111/ele.12493) for established alien mammals, and the Global Invasive Species Database (GISD, http://www.iucngisd.org/gisd/, accessed on July 1, 2020) for established alien invertebrates.

Code availability

The R code for running the analyses is provided in Supplementary Information file (Supplementary Notes).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Lin Zhang, Jason Rohr, Ruina Cui, Xuan Liu.

Contributor Information

Qin Hao, Email: haoqin@icdc.cn.

Xuan Liu, Email: liuxuan@ioz.ac.cn.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-022-29378-2.

References

- 1.Jones KE, et al. Global trends in emerging infectious diseases. Nature. 2008;451:990–U994. doi: 10.1038/nature06536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dobson AP, et al. Ecology and economics for pandemic prevention. Science. 2020;369:379–381. doi: 10.1126/science.abc3189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schindler S, Staska B, Adam M, Rabitsch W, Essl F. Alien species and public health impacts in Europe: a literature review. NeoBiota. 2015;27:1. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Young HS, Parker IM, Gilbert GS, Sofia Guerra A, Nunn CL. Introduced species, disease ecology, and biodiversity–disease relationships. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2017;32:41–54. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2016.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chinchio E, et al. Invasive alien species and disease risk: an open challenge in public and animal health. PLoS Pathog. 2020;16:e1008922. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1008922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schatz AM, Park AW. Host and parasite traits predict cross-species parasite acquisition by introduced mammals. P. Roy. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2021;288:20210341. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2021.0341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Seebens H, et al. Projecting the continental accumulation of alien species through to 2050. Glob. Change Biol. 2021;27:970–982. doi: 10.1111/gcb.15333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hulme PE. Invasive species challenge the global response to emerging diseases. Trends Parasitol. 2014;30:267–270. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2014.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nuñez MA, Pauchard A, Ricciardi A. Invasion science and the global spread of SARS-CoV-2. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2020;35:642–645. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2020.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stoett P, Roy HE, Pauchard A. Invasive alien species and planetary and global health policy. Lancet Planet. Health. 2019;3:e400–e401. doi: 10.1016/S2542-5196(19)30194-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ogden NH, et al. Emerging infectious diseases and biological invasions: a call for a One Health collaboration in science and management. Roy. Soc. Open Sci. 2019;6:181577. doi: 10.1098/rsos.181577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Conn DB. Aquatic invasive species and emerging infectious disease threats: A One Health perspective. Aquat. Invasions. 2014;9:3. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lounibos LP. Invasions by insect vectors of human disease. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2002;47:233–266. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ento.47.091201.145206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kosoy M, Khlyap L, Cosson JF, Morand S. Aboriginal and invasive rats of genus rattus as hosts of infectious agents. Vector Borne Zoonot. 2015;15:3–12. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2014.1629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beltrán-Beck B, García FJ, Gortázar C. Raccoons in Europe: disease hazards due to the establishment of an invasive species. Eur. J. Wildl. Res. 2012;58:5–15. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Medlock JM, et al. A review of the invasive mosquitoes in Europe: ecology, public health risks, and control options. Vector Borne Zoonot. 2012;12:435–447. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2011.0814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu X, Rohr JR, Li Y. Climate, vegetation, introduced hosts and trade shape a global wildlife pandemic. P. Roy. Soc. B-Biol. Sci. 2013;280:20122506. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2012.2506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carlson, C. J. et al. Climate change will drive novel cross-species viral transmission. Preprint at https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.01.24.918755v1 (2021).

- 19.Halliday FW, Rohr JR, Laine A-L. Biodiversity loss underlies the dilution effect of biodiversity. Ecol. Lett. 2020;23:1611–1622. doi: 10.1111/ele.13590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Faust CL, et al. Pathogen spillover during land conversion. Ecol. Lett. 2018;21:471–483. doi: 10.1111/ele.12904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Allen T, et al. Global hotspots and correlates of emerging zoonotic diseases. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:1124. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-00923-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yu VL, Edberg SC. Global Infectious Diseases and Epidemiology Network (GIDEON): a world wide web-based program for diagnosis and informatics in infectious diseases. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2005;40:123–126. doi: 10.1086/426549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Olival KJ, et al. Host and viral traits predict zoonotic spillover from mammals. Nature. 2017;546:646–650. doi: 10.1038/nature22975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Keesing F, Ostfeld RS. Impacts of biodiversity and biodiversity loss on zoonotic diseases. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2021;118:e2023540118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2023540118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mollentze N, Streicker DG. Viral zoonotic risk is homogenous among taxonomic orders of mammalian and avian reservoir hosts. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2020;117:9423–9430. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1919176117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dawson W, et al. Global hotspots and correlates of alien species richness across taxonomic groups. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2017;1:0186. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Albery GF, et al. The science of the host–virus network. Nat. Microbiol. 2021;6:1483–1492. doi: 10.1038/s41564-021-00999-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wille M, Geoghegan JL, Holmes EC. How accurately can we assess zoonotic risk? PLoS Biol. 2021;19:e3001135. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.3001135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johnson CK, et al. Global shifts in mammalian population trends reveal key predictors of virus spillover risk. P. Roy. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2020;287:20192736. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2019.2736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gibb R, et al. Zoonotic host diversity increases in human-dominated ecosystems. Nature. 2020;584:398–402. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2562-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bonizzoni M, Gasperi G, Chen X, James AA. The invasive mosquito species Aedes albopictus: current knowledge and future perspectives. Trends Parasitol. 2013;29:460–468. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2013.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pauwels, O. S. & Pantchev, N. Risks for human health related to invasive alien reptiles and amphibians. Invasive species and human health. 108–119 (Centre for Agriculture and Biosciences Int’l, Wallingford, UK, 2018).

- 33.Kraus F. Impacts from invasive reptiles and amphibians. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2015;46:75–97. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rohr JR, Cohen JM. Understanding how temperature shifts could impact infectious disease. PLoS Biol. 2020;18:e3000938. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.3000938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morand S, et al. Changing landscapes of Southeast Asia and rodent-borne diseases: decreased diversity but increased transmission risks. Ecol. Appl. 2019;29:e01886. doi: 10.1002/eap.1886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mweempwa C, et al. Impact of habitat fragmentation on tsetse populations and trypanosomosis risk in Eastern Zambia. Parasite Vector. 2015;8:406. doi: 10.1186/s13071-015-1018-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lafferty KD. The ecology of climate change and infectious diseases. Ecology. 2009;90:888–900. doi: 10.1890/08-0079.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ostfeld RS, Brunner JL. Climate change and Ixodes tick-borne diseases of humans. Philos. T. R. Soc. B. 2015;370:20140051. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2014.0051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Halliday FW, Rohr JR. Measuring the shape of the biodiversity-disease relationship across systems reveals new findings and key gaps. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:1–10. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-13049-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cohen JM, et al. Spatial scale modulates the strength of ecological processes driving disease distributions. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2016;113:E3359–E3364. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1521657113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Keesing F, et al. Impacts of biodiversity on the emergence and transmission of infectious diseases. Nature. 2010;468:647–652. doi: 10.1038/nature09575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hay SI, et al. Global mapping of infectious disease. Philos. T. R. Soc. B. 2013;368:20120250. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2012.0250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Murray KA, et al. Global biogeography of human infectious diseases. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:12746–12751. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1507442112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Metzger MJ, et al. A high-resolution bioclimate map of the world: a unifying framework for global biodiversity research and monitoring. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2013;22:630–638. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dunn RR, Davies TJ, Harris NC, Gavin MC. Global drivers of human pathogen richness and prevalence. P. Roy. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2010;277:2587–2595. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2010.0340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jenkins CN, Pimm SL, Joppa LN. Global patterns of terrestrial vertebrate diversity and conservation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:E2602–E2610. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1302251110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pimm SL, et al. The biodiversity of species and their rates of extinction, distribution, and protection. Science. 2014;344:1246752. doi: 10.1126/science.1246752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Roll U, et al. The global distribution of tetrapods reveals a need for targeted reptile conservation. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2017;1:1677–1682. doi: 10.1038/s41559-017-0332-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kraus, F. Alien Reptiles and Amphibians: A Scientific Compendium and Analysis. Invading Nature-Springer Series in Invasion Ecology4 (Springer, Dordrecht, 2009).

- 50.Capinha C, et al. Diversity, biogeography and the global flows of alien amphibians and reptiles. Divers. Distrib. 2017;23:1313–1322. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dyer EE, Redding DW, Blackburn TM. The global avian invasions atlas, a database of alien bird distributions worldwide. Sci. Data. 2017;4:sdata201741. doi: 10.1038/sdata.2017.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Long, J. Introduced mammals of the world (CSIRO PUBLISHING, 2003).

- 53.Capellini I, Baker J, Allen WL, Street SE, Venditti C. The role of life history traits in mammalian invasion success. Ecol. Lett. 2015;18:1099–1107. doi: 10.1111/ele.12493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gibb R, et al. Data Proliferation, Reconciliation, and Synthesis in Viral Ecology. Bioscience. 2021;71:1148–1156. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stephens PR, et al. Global mammal parasite database version 2.0. Ecology. 2017;98:1476–1476. doi: 10.1002/ecy.1799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wardeh, M., Risley, C., McIntyre, M. K., Setzkorn, C. & Baylis, M. Database of host-pathogen and related species interactions, and their global distribution. Sci. Data2, sdata.2015.49 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 57.Shaw LP, et al. The phylogenetic range of bacterial and viral pathogens of vertebrates. Mol. Ecol. 2020;29:3361–3379. doi: 10.1111/mec.15463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Harris I, Jones P, Osborn T, Lister D. Updated high‐resolution grids of monthly climatic observations–the CRU TS3. 10 Dataset. Int. J. Climatol. 2014;34:623–642. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ellis EC, Klein Goldewijk K, Siebert S, Lightman D, Ramankutty N. Anthropogenic transformation of the biomes, 1700 to 2000. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2010;19:589–606. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Moore M, Gelfeld B, Okunogbe A, Paul C. Identifying future disease hot spots: infectious disease vulnerability index. Rand Health Q. 2017;6:5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Albery, G. F. et al. Urban-adapted mammal species have more known pathogens. Preprint at https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.01.02.425084v1 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 62.Burnham, K. P. & Anderson, D. R. Model selection and multimodel inference: a practical information-theoretic approach. (Springer Verlag, 2002).

- 63.Redding DW, et al. Location-level processes drive the establishment of alien bird populations worldwide. Nature. 2019;571:103–106. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1292-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.R Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, 2020). www.R-project.org.

- 65.Lomolino MV, Weiser M. Towards a more general species-area relationship: diversity on all islands, great and small. J. Biogeogr. 2001;28:431–445. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Description of Additional Supplementary Information

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study are from existing datasets and are included in Supplementary Data 1-4. The exact list of known zoonotic pathogens and zoonoses at the administrative level is recorded in the GIDEON database (www.gideononline.com) (Last access date, November 9, 2020). The administrative designations used in our analyses are based on the Global Administrative Areas (GADM) database (www.gadm.org, downloaded on November 8, 2020). The alien host-pathogen association data are based on Gibb’s dataset (CLOVER_Associations_Initial.csv, 10.5281/zenodo.4435128) and other literatures in Supplementary Data 2. The Infectious Disease Vulnerability Index (IDVI) is from Moore et al. (2017) (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28845357/). We use global environmental stratification (GEnS, https://www.geoportal.org/) as a composite bioclimatic variable generated by stratifying the Earth’s surface into zones with similar climates. For the temperature and precipitation change variable, we extract historical monthly mean temperature and precipitation data recorded between 1901 and 2009 from the University of East Anglia Climate Research Unit (CRU, https://catalogue.ceda.ac.uk/uuid/3f8944800cc48e1cbc29a5ee12d8542d, accessed on November 30, 2020), and global land-use data from the Anthromes v2 Dataset (Anthropogenic Biomes version 2, https://ecotope.org/anthromes/v2/, accessed on October 15, 2020) in ESRI GRID format. Human population size data and the land area of each jurisdiction are collected from World Bank Open Data from 2011 to 2020 (available at https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.POP.TOTL, accessed on November 18, 2020). Data on the richness of native amphibians, birds, and mammals are derived from the Biodiversity Mapping website (https://biodiversitymapping.org/wordpress/index.php/home/, accessed on August 19, 2020) derived from Jenkins et al. (2013) (10.1073/pnas.1302251110) and Pimm et al. (2014) (https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.1246752). The latest map for the reptile species is from Roll et al. (2017) (10.5061/dryad.83s7k). The list of threatened species evaluated as NT, EN and VU used for calculating the loss of native biodiversity is extracted from the IUCN Red List (http://www.iucnredlist.org, access on May 10th, 2021). The established alien species list and the introduction time information used for the temporal analyses are based on Kraus’s (2009) compendium (https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-1-4020-8946-6_6) and Capinha et al. (2017) (10.1111/ddi.12617) for reptiles and amphibians, the Global Avian Invasions Atlas (GAVIA) (10.6084/m9.figshare.4234850) for established alien birds, Long’s (2003) book (https://ebooks.publish.csiro.au/content/introduced-mammals-world) and Capellini et al. (2015) (10.1111/ele.12493) for established alien mammals, and the Global Invasive Species Database (GISD, http://www.iucngisd.org/gisd/, accessed on July 1, 2020) for established alien invertebrates.

The R code for running the analyses is provided in Supplementary Information file (Supplementary Notes).