Abstract

Objectives

The Ontario Marginalization Index (ON-Marg) is an area-based measure used widely to measure health inequalities in Ontario. Recently, the index was updated for 2011 and 2016. The loss of the 2011 long-form census required the use of alternative data sources for the 2011 version. This paper describes the update of ON-Marg, assesses consistency in the indices across census years using Dissemination Areas, and examines associations between ON-Marg 2016 and four health and social outcomes to demonstrate its potential to measure health inequalities.

Methods

ON-Marg was created using factor analysis. Differences in quintile assignment was compared over time to assess whether the use of taxfiler, immigration, property assessment, and health card address data in 2011 affected consistency in measurement of marginalization. Inequalities in rates of overall mortality, gonorrhea incidence, mental health emergency department visits, and alcohol retail locations across quintiles of ON-Marg 2016 were quantified using the Relative Index of Inequality.

Results

Depending on the dimension, between 81% and 96% of DAs showed limited or no changes in quintiles of marginalization between 2006, 2011 and 2016. Of the 45–64% of DAs that did not change quintile between 2006 and 2016, 1.8% to 8.8% of DAs in 2011 differed by two or more quintiles. Findings showed significant differences in rates of health and social outcomes across quintiles of ON-Marg 2016, with strength and directionality varying by dimension of ON-Marg.

Conclusion

Alternative data sources did not substantially affect the consistency of the 2011 version of ON-Marg. The updated ON-Marg is a comprehensive tool that can be used to study health inequalities in Ontario.

Keywords: Health equity, Health status disparities, Health status indicators, Marginalization, Methods, Ontario / Epidemiology

Résumé

Objectifs

L’indice de marginalisation ontarien (indice ON-Marg) est un indicateur par secteurs largement utilisé pour mesurer les inégalités en santé dans la province. Il a récemment été mis à jour pour 2011 et 2016. Avec l’élimination du recensement long en 2011, il a fallu se tourner vers d’autres sources de données. Le présent article décrit la mise à jour de l’indice ON-Marg, évalue l’uniformité des indices d’un recensement à l’autre d’après les aires de diffusion, et examine les liens entre l’indice ON-Marg 2016 et quatre résultats en matière de santé et sur le plan social pour illustrer son potentiel à mesurer les inégalités en santé.

Méthodologie

L’indice ON-Marg a été créé selon les principes de l’analyse factorielle. Ont été comparés au fil du temps les écarts entre les quintiles pour évaluer si l’utilisation en 2011 des données des déclarants, d’immigration et d’évaluation foncière et celles des adresses des cartes Santé avait eu une incidence sur l’uniformité de la mesure de la marginalisation. Les inégalités quant au taux global de mortalité, à l’incidence de la gonorrhée, au nombre de visites dans les services d’urgence pour des raisons de santé mentale et à l’emplacement des magasins de vente au détail d’alcool par quintiles de l’indice ON-Marg 2016 ont été quantifiées au moyen de l’indice d’inégalité relative.

Résultats

Selon l’aspect, il y avait peu ou pas de changements dans 81 % à 96 % des aires de diffusion pour les quintiles de marginalisation de 2006, 2011 et 2016. Parmi les aires de diffusions qui n’ont pas changé de quintile de 2006 à 2016 (45 % à 64 % d’entre elles), on a observé un écart de deux quintiles ou plus en 2011 dans 1,8 % à 8,8 % des cas. L’étude témoigne d’un écart significatif dans les taux des résultats en matière de santé et sur le plan social pour l’ensemble des quintiles de l’indice ON-Marg 2016, la force et la direction variant en fonction de l’aspect.

Conclusion

L’utilisation d’autres sources de données n’a pas eu de grande incidence sur l’uniformité de la version 2011 de l’indice ON-Marg. La dernière version mise à jour est un outil complet pouvant servir à étudier les inégalités en santé en Ontario.

Mots-clés: Équité en santé, disparités de l’état de santé, indicateurs de l’état de santé, marginalisation, méthodes, Ontario/épidémiologie

Introduction

Reliable measurement of population health inequalities is foundational for efforts to understand and reduce them. Measuring differences in health across population groups is hampered, in many cases, by the inability to link health outcome data with socio-demographic characteristics such as income and ethnicity. Area-based deprivation indices (ABDI) have frequently been used to fill gaps in the availability of person-level socio-demographic data (Bryere et al., 2016). In particular, ABDIs can be used for surveillance purposes and to monitor health inequalities occurring in administrative health care records that contain limited individual-level socio-demographic data (Boyd et al., 2004; Forer et al., 2020; Moin et al., 2018; Rossen, 2014; Sánchez-Santos et al., 2013; Silverman et al., 2013; Tobias & Cheung, 2003).

The Ontario Marginalization Index (ON-Marg) is one such ABDI that has been widely used to understand how area-based marginalization drives health inequalities at the neighbourhood level in Ontario (Matheson et al., 2012a). ON-Marg was originally developed as a provincial-specific version of the Canadian Marginalization Index (Matheson et al., 2012b, c), a national census-based, geographically derived index of social and economic marginalization. ON-Marg provides measures of multiple axes of social stratification, and combines discrete, yet related, concepts into four dimensions of marginalization (Matheson et al., 2012a).

Since its creation in 2006, ON-Marg has been used extensively across Ontario in government, health care and public health organizations for research on health disparities, advocacy work, population health assessment and surveillance, and public health program planning and resource allocation (Lachaud et al., 2018; Peel, 2011; Simons et al., 2019). As population characteristics change over time, ON-Marg also requires updating to maintain its ability to provide accurate assessments of the distribution of marginalization in the province. In 2011, the Canadian federal government replaced the mandatory long-form component of the Canadian Census of Population with a voluntary National Household Survey (NHS). Previous versions of ON-Marg were created using Census variables. The voluntary nature of the NHS introduced the possibility that the use of these data would introduce non-response bias if sampled individuals who chose to respond were different from sampled individuals who chose not to respond. This concern especially impacted data quality for small-area geographies, which were used in previous census years to derive ON-Marg (Statistics Canada, 2011). For this reason, the 2011 update to ON-Marg does not use data from the NHS and instead uses alternative data sources to replace indicators formally based on the long-form census (LFC).

The purpose of this paper is to describe how the 2011 and 2016 iterations of ON-Marg were created and to determine whether ON-Marg 2011 produces measures of marginalization that are consistent with the 2006 and 2016 versions despite the change of data sources for some indicators. This paper will explore inequalities in rates of overall mortality, gonorrhea incidence, mental health emergency department (ED) visits, and alcohol retail locations to showcase how ON-Marg can be used for monitoring inequalities across a range of outcomes and administrative data sources.

Data and methods

Data sources

The Ontario Marginalization Index

The Ontario Marginalization Index is an Ontario-specific version of the Canadian Marginalization Index, a widely used ABDI that has been described elsewhere (Matheson et al., 2012a, b, c). Briefly, CAN-Marg was formulated by building on theoretical frameworks used to develop over 60 existing indices of social and material inequality. Using an expanded theoretical conceptualization of marginalization in contemporary society, the developers assembled a broad set of potential census indicators for inclusion in factor analysis with principal component method (Kim and Mueller, 1978a, b). Forty-two variables were identified from the Canadian Census of Population and reduced to 18 variables which loaded across four factors with eigenvalues greater than one. These four factors represent different dimensions of marginalization: (1) dependency, which identifies neighbourhoods with high proportions of seniors, children, and adults whose work is not compensated and/or unable to work due to disability; (2) ethnic concentration, which measures area-level concentrations of recent Canadian immigrants and/or people belonging to a “visible minority” group (defined by Statistics Canada as “persons, other than Aboriginal peoples, who are non-Caucasian in race or non-white in colour”); (3) material deprivation, which is conceptually connected to poverty and socio-economic position and associated with indicators of low income, educational attainment, quality of housing, and family housing characteristics; and (4) residential instability, which measures neighbourhood cohesiveness and volatility/fluidity, and is associated with indicators of housing types, population density, and family structure characteristics.

The 2001, 2006 and 2016 versions of ON-Marg are all derived using data from the Canadian census, while the 2011 version additionally includes four alternative non-census sources of routinely collected administrative data: (1) the Statistics Canada T1 Family File (T1FF), which provides information on income and employment characteristics of all Canadian residents collected from T1 income tax returns; (2) the Municipal Property Assessment Corporation (MPAC) residential housing and property characteristics database, which contains information from in-person assessments and permit applications collected to assess property values in Ontario; (3) the Registered Persons Database (RPDB), maintained by the Ontario Ministry of Health, which contains demographic and residential address information of all residents of Ontario who are eligible for Ontario Health Insurance Program; and (4) the Immigration, Refugee, and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) Permanent Resident Database, which contains administrative and demographic records on all immigrants to Canada from 1985 onwards. While ethnicity is not among the demographic data recorded in the IRCC database, immigrants were categorized as belonging to visible minority groups based on country of birth, mother tongue, and surname, following the procedures developed by Shah et al. (2010). These datasets were linked using unique encoded identifiers and analyzed at ICES.

Of the 18 variables used in the 2001, 2006 and 2016 versions of ON-Marg, seven were still available in the 2011 short-form census, while nine were reconstructed using the alternative data sources. Indicators included in ON-Marg and their data sources are listed in Table 1. Of note, measures of “proportion age 25+ without certificate, diploma or degree” and “proportion age 15+ unemployed” could not be replicated using available alternative data sources, and were not included in the 2011 version.

Table. 1.

Data source, factor loadings (FL), and correlations (R) for four dimensions of ON-Marg

| 2006 | 2011 | 2016 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data source | FL | R | Data source | FL | R | Data source | FL | R | |

| Dependency | |||||||||

| % seniors (aged 65+) | SFC | 85 | 0.9 | SFC | 89 | 0.93 | SFC | 90 | 0.93 |

| Dependency ratio (15–64/0–14, 65+) | SFC | 86 | 0.82 | SFC | 85 | 0.78 | SFC | 76 | 0.69 |

| Labour force participation (aged 15+)a,b | LFC | 80 | 0.82 | T1FF | 65 | 0.63 | LFC | 80 | 0.76 |

| Ethnic concentration | |||||||||

| % recent immigrants (within past 5 years) | LFC | 88 | 0.86 | IRCC | 86 | 0.91 | LFC | 85 | 0.82 |

| % visible minorityc | LFC | 92 | 0.86 | IRCC | 87 | 0.92 | LFC | 95 | 0.91 |

| Material deprivation | |||||||||

| % lone-parent families | SFC | 67 | 0.6 | SFC | 78 | 0.8 | SFC | 69 | 0.79 |

| % aged 25–64 without certificate/degree/diploma | LFC | 71 | 0.72 | LFC | 83 | 0.72 | |||

| % unemployed aged 15+ | LFC | 51 | 0.53 | LFC | 51 | 0.56 | |||

| % income from government transfer paymentsd | LFC | 68 | 0.74 | T1FF | 88 | 0.79 | LFC | 80 | 0.81 |

| % below low-income cut-off (LICO)e | LFC | 54 | 0.75 | T1FF | 83 | 0.9 | LFC | 34 | 0.64 |

| % dwellings needing major repairf | LFC | 60 | 0.54 | MPAC | 42 | 0.17 | LFC | 60 | 0.55 |

| Residential stability | |||||||||

| % living alone | SFC | 89 | 0.91 | SFC | 87 | 0.92 | SFC | 87 | 0.88 |

| % youth population aged 5–15 | SFC | 77 | 0.69 | SFC | 76 | 0.73 | SFC | 62 | 0.57 |

| Average number persons per dwellinga | SFC | 87 | 0.85 | SFC | 82 | 0.87 | SFC | 78 | 0.77 |

| % married/common-lawa | SFC | 62 | 0.83 | SFC | 60 | 0.76 | SFC | 66 | 0.8 |

| % multi-unit housing | LFC | 76 | 0.76 | MPAC | 71 | 0.72 | LFC | 88 | 0.86 |

| % dwellings owneda | LFC | 63 | 0.78 | MPAC | 59 | 0.73 | LFC | 77 | 0.87 |

| % residential mobility | LFC | 45 | 0.46 | RPDB | 49 | 0.51 | LFC | 75 | 0.69 |

Abbreviations: SFC, short-form census; LFC, long-form census; T1FF, T1 Family File; MPAC, Municipal Property Assessment Corporation; RPDB, Registered Persons Database

aVariables were reverse coded, and the inverse measure is included in the index

bMeasured as employment rate in 2011

cMeasured as visible minority immigrants in 2011

dMeasured as DA-level ratio of median income from government transfer payments to median total income in 2011

eMeasured as % below Low Income Measure (LIM) in 2011

fMeasured as % houses in fair or poor condition in 2011

Health and social outcomes

To demonstrate the potential for ON-Marg to measure health and social gradients across a range of outcomes, four indicators were selected to represent a broad spectrum of public health concerns, covering overall health, communicable diseases, mental health and built environment. Additionally, these indicators were chosen to show ON-Marg’s ability to measure inequalities using different types of data that are widely available and commonly used for public health surveillance in Ontario: vital statistics, reportable disease surveillance data, administrative health system records and retail location data.

The overall mortality rate was derived for 2015 from the Ontario Office of the Registrar General’s Vital Statistics Death Registry, which contains information on deaths in Ontario collected from death certificates completed by physicians. Incidence of gonorrhea in the years 2015–2017 was extracted from the integrated Public Health Information System (iPHIS), an Ontario Ministry of Health database containing information on cases of reportable diseases. The rate of mental health-related ED visits was derived for 2016 from the National Ambulatory Care Reporting System, an administrative health care data source which contains information on ambulatory visits, including emergency visits and other hospital-based outpatient clinic visits. Mental health-related visits were considered for the population 15 and older and include substance-related disorders, schizophrenia, delusional and non-organic psychotic disorders, mood/affective disorders, anxiety disorders, and selected disorders of adult personality and behaviour (see Appendix for ICD10 codes). Alcohol retail location data were obtained from the Liquor Control Board of Ontario (LCBO), the provincial Crown Corporation that retails and regulates the sale of alcohol in Ontario. Location data on 660 LCBO retail locations were extracted on January 9, 2019, and retail locations for 450 Brewer’s Retail Inc. (The Beer Store), 200 LCBO Convenience Outlets and 350 grocery stores authorized to sell beer, wine and cider were extracted on October 3, 2018.

In total, this analysis included 95,329 deaths, 217,683 ED visits, 19,117 gonorrhea cases and 1660 alcohol retail locations. All health and alcohol retail location data were geocoded to a 2016 census DA for the purpose of assigning a quintile of ON-Marg using the Statistics Canada Postal Code Conversion File Plus (PCCF+) version 7B.

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Board of St. Michael’s Hospital and the Ethics Review Board of Public Health Ontario.

Statistical analyses

Updating the Ontario Marginalization Index

The 2011 and 2016 versions of ON-Marg were derived by conducting factor analysis using available DA-level variables using PROC FACTOR in SAS 9.3. We assumed that the relationship between marginalization and the 18 variables used in the 2006 version of ON-Marg did not substantially evolve since 2006. The 2011 version was created using 16 available variables derived for 19,568 DAs. The 2016 version was created using 18 variables derived for 19,803 DAs. Factors were constructed using oblique rotation to allow for correlations among the resulting dimensions of marginalization. Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated to describe the strength of the association between each factor and indicators contributing to it. For each of the resulting factors, DAs were assigned into quintiles such that each group contains an equal number of DAs.

Assessing impact of alternative data sources in the 2011 Ontario Marginalization Index

To assess consistency over time, Statistics Canada Correspondence Files were used to link 2006, 2011 and 2016 DAs. DA geographies are updated by Statistics Canada with each census, and between 2006 and 2016 a small percentage of DAs were re-delineated in a way that makes it impossible to fairly compare how quintiles of ON-Marg were assigned for that area over time. For example, only those areas where one 2006 DA became one 2011 DA, or one 2006 DA became many 2011 DAs could be used to compare 2006 and 2011 versions of ON-Marg. Where one DA became many DAs in the following census year, all of the new DAs were assigned the quintile of the previous DA.

The differences in the ON-Marg quintile assigned to each DA were calculated to describe changes in ON-Marg between 2006 and 2011, 2011 and 2016, and 2006 and 2016. Differences between 2011 and 2016 were also calculated for the subset of DAs that were stable and did not change in the 10-year period between 2006 and 2016. Within this subset of stable Ontario geographies, deviations in ON-Marg assignment in 2011 would suggest that the use of alternative data sources produced anomalous results.

Additionally, consistency in the structure of the factors was assessed by comparing eigenvalues and proportion of variance explained by each factor. Factor loadings and correlations between indicators and their respective factors were measured over time to assess the consistency of the influence and representativeness of each indicator.

Measuring associations between ON-Marg and health and social outcomes

ON-Marg was used to assign each death, gonorrhea case, mental health ED visit, and alcohol retail location to the quintile of marginalization from 1 (low) to 5 (high) of the DA where the individual resided or the retail location was situated. Counts of these outcomes were then aggregated by quintile of ON-Marg, and quintile-specific rates per 100,000 population were calculated using the 2016 census population of each quintile for denominators. The quintile-specific rates of overall mortality, gonorrhea incidence and mental health ED visits were age-standardized to the 2011 Canadian census population to account for any age differences between quintiles of marginalization.

To quantify the direction and magnitude of inequalities in the rates of health and social outcomes across quintiles, the Relative Index of Inequality (RII) was calculated for each outcome and dimension of ON-Marg. Following the approach for analyzing data aggregated by socio-economic group proposed by Moreno-Betancur et al. (2015), we used a multiplicative Poisson regression model with age-group specific counts to estimate the RII. We derived the cumulative proportion of the population in each quintile (ordered from low to high), and used the midpoints of each quintile’s range as the independent variable, with the natural log of the population by age group and quintile as the model offset. The use of the log-link function allows the estimation of, in relative terms, the linear association between marginalization and each outcome across the entire distribution of marginalization. The RII represents the ratio of predicted value of the outcome in the hypothetical most marginalized individual (i.e., 100th percentile of the distribution) and the hypothetical least marginalized individual (i.e., 0th percentile of the distribution). A RII greater than 1 indicates a social gradient with higher levels of the outcome among the most marginalized, while the magnitude of the RII describes the strength of the relative change in the outcome across the distribution of marginalization.

Results

Updating Ontario Marginalization Index

Factor analysis was used to derive 2011 and 2016 versions of ON-Marg that contain the same four factors as earlier versions of ON-Marg. As shown in Table 1, factor loadings and correlations between the indicators and their respective marginalization dimension displayed stability across time, with the notable exception of the unavailability of suitable alternatives for the variables measuring “proportion age 25+ without certificate, diploma or degree” and “proportion unemployment 15+” in 2011. Variables measuring “proportion of homes needing major repair” and “labour force participation” had lower factor loadings with the alternative 2011 variables than the census-based 2006 and 2016 variables. The variable for “proportion low income” shifted across all time periods, where the highest loading was observed in 2011 and the lowest loading was observed in 2016. Factor loadings were higher in 2016 compared with 2006 and 2011 for “proportion multi-unit housing”, “proportion dwellings that are owned” and “proportion of residential mobility”, while “proportion youth population” scored lowest in 2016.

The factors themselves showed consistent eigenvalues, which are used to compute the proportion of variance of the input variables that can be explained by the resultant factors (Table 2). Residential instability consistently explained the largest proportion of variation out of the four dimensions, with diminishing variance explained by the material deprivation, dependency and ethnic concentration dimensions.

Table 2.

Eigenvalues and variance explained for the four dimensions of ON-Marg

| Marginalization dimension | 2006 | 2011 | 2016 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dependency | |||

| Eigenvalue | 1.85 | 1.68 | 1.89 |

| Proportion of variance explained | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.10 |

| Ethnic concentration | |||

| Eigenvalue | 1.48 | 1.36 | 1.53 |

| Proportion of variance explained | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.08 |

| Residential instability | |||

| Eigenvalue | 6.04 | 5.88 | 6.22 |

| Proportion of variance explained | 0.34 | 0.37 | 0.35 |

| Material deprivation | |||

| Eigenvalue | 3.18 | 3.15 | 3.16 |

| Proportion of variance explained | 0.18 | 0.20 | 0.18 |

Assessing consistency of the 2011 Ontario Marginalization Index

Of the Ontario DAs where an ON-Marg value could be calculated, the correspondence files allowed comparisons between the 2006 and 2011 versions of ON-Marg for 95.3% of DAs, between the 2011 and 2016 versions of ON-Marg for 98.3% of DAs, and between the 2006 and 2016 versions of ON-Marg for 93.7% of DAs.

Table 3 describes the proportion of DAs that changed quintile levels across years, and how large of a change was observed. Across all four dimensions, the majority of DAs either did not change, or changed by +/–1 quintile over the comparative census years. Between 4.0% and 19.3% of DAs changed by +/–2 or more quintiles, with the largest fluctuation observed in material deprivation between 2006 and 2011. Between 45.2% and 63.7% of DAs did not change quintiles between the 2006 and 2016 versions of ON-Marg. Of this subset of stable DAs, the 2011 version of the index differed by +/–2 or more quintiles for 1.8% of DAs for the dependency dimension, 3.8% of DAs for the ethnic concentration dimension, 8.7% of DAs for the material deprivation dimension, and 2.9% of DAs for the residential instability. The results do not show any directionality in the change of quintiles over time.

Table 3.

Quintile differences for four dimensions of ON-Marg between 2006, 2011, 2016 and only those DAs that did not change between 2006 and 2016

| a. Dependency | ||||

| Change in quintiles between 2006 and 2011 (% of DAs) (N = 18,773) | Change in quintiles between 2011 and 2016 (% of DAs) (N = 18,907) | Change in quintiles between 2006 and 2016 (% of DAs) (N = 18,778) |

Of DAs that did not change quintiles between 2006 and 2016: Change in 2011 (% of DAs) (N = 8629) |

|

| −4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 |

| −3 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 1.1 | 0.1 |

| −2 | 3.9 | 2.9 | 6.8 | 1.0 |

| −1 | 20.8 | 19.1 | 20.8 | 12.4 |

| No change | 53.7 | 56.2 | 45.9 | 74.2 |

| 1 | 17.5 | 18.0 | 18.6 | 11.7 |

| 2 | 3.2 | 3.3 | 5.7 | 0.6 |

| 3 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.9 | 0.1 |

| 4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.0 |

| ≥ +/− 2 | 7.9 | 6.8 | 14.7 | 1.8 |

| b. Ethnic concentration | ||||

| Change in quintiles between 2006 and 2011 (% of DAs) (N = 18,773) | Change in quintiles between 2011 and 2016 (% of DAs) (N = 18,907) | Change in quintiles between 2006 and 2016 (% of DAs) (N = 18,778) |

Of DAs that did not change quintiles between 2006 and 2016: Change in 2011 (% of DAs) (N = 10,032) |

|

| −4 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 |

| −3 | 0.4 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.1 |

| −2 | 3.6 | 2.9 | 3.4 | 1.3 |

| −1 | 17.9 | 17.0 | 16.7 | 14.8 |

| No change | 53.3 | 56.6 | 53.4 | 68.5 |

| 1 | 19.2 | 20.0 | 21.4 | 12.9 |

| 2 | 4.5 | 2.6 | 4.1 | 1.9 |

| 3 | 1.0 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.6 |

| 4 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| ≥ +/− 2 | 9.6 | 6.5 | 8.6 | 3.8 |

| c. Material deprivation | ||||

| Change in quintiles between 2006 and 2011 (% of DAs) (N = 18,773) | Change in quintiles between 2011 and 2016 (% of DAs) (N = 18,907) | Change in quintiles between 2006 and 2016 (% of DAs) (N = 18,778) |

Of DAs that did not change quintiles between 2006 and 2016: Change in 2011 (% of DAs) (N = 8507) |

|

| −4 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| −3 | 2.1 | 0.7 | 1.2 | 0.8 |

| −2 | 7.8 | 5.2 | 6.6 | 4.0 |

| −1 | 19.6 | 20.5 | 21.5 | 16.2 |

| No change | 41.0 | 47.6 | 45.2 | 57.6 |

| 1 | 20.1 | 19.4 | 18.5 | 17.5 |

| 2 | 7.3 | 5.4 | 5.7 | 3.4 |

| 3 | 1.5 | 0.9 | 1.1 | 0.4 |

| 4 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| ≥ +/− 2 | 19.2 | 12.4 | 14.8 | 8.7 |

| d. Residential instability | ||||

| Change in quintiles between 2006 and 2011 (% of DAs) (N = 18,773) | Change in quintiles between 2011 and 2016 (% of DAs) (N = 18,907) | Change in quintiles between 2006 and 2016 (% of DAs) (N = 18,778) |

Of DAs that did not change quintiles between 2006 and 2016: Change in 2011 (% of DAs) (N = 11,965) |

|

| −4 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 | |

| −3 | 0.1 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 0.0 |

| −2 | 2.1 | 2.9 | 1.9 | 0.7 |

| −1 | 19.8 | 15.2 | 17.1 | 15.7 |

| No change | 59.4 | 60.6 | 63.7 | 70.4 |

| 1 | 15.3 | 18.8 | 15.2 | 11.1 |

| 2 | 2.7 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 1.7 |

| 3 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.4 |

| 4 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| ≥ +/− 2 | 5.5 | 5.4 | 4.0 | 2.9 |

Measuring associations between ON-Marg 2016 and health and social outcomes

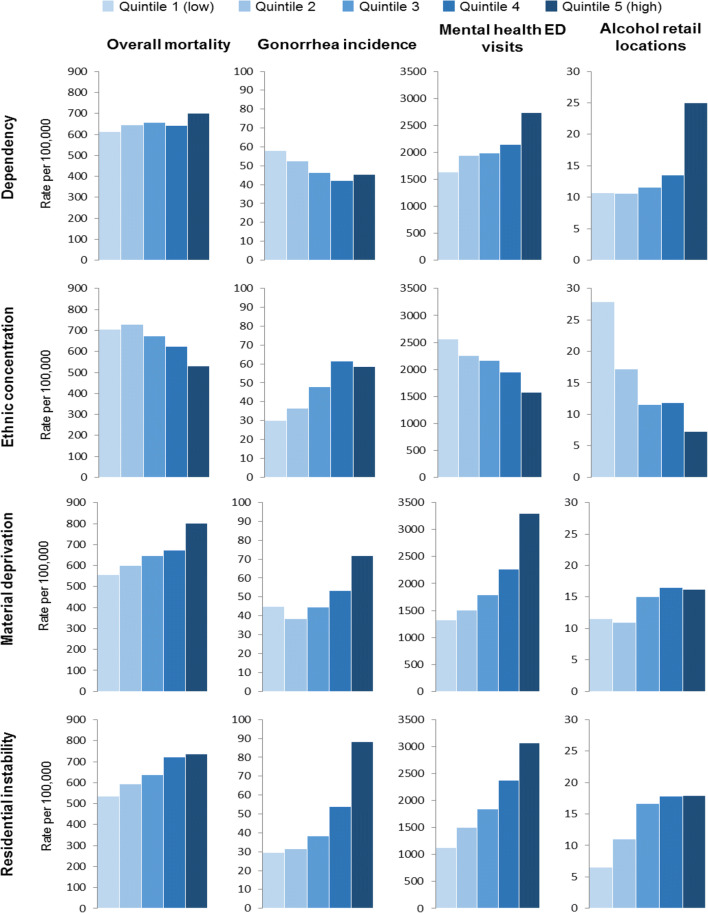

Rates of overall mortality, gonorrhea incidence, mental health ED visits, and alcohol retail locations, stratified by dimension and quintile of marginalization, are presented in Fig. 1. We found social gradients showing higher rates of a given outcome across increasing quintiles of marginalization in 12 of the 16 indicator and ON-Marg dimension combinations included in this analysis. Inverse gradients were found where rates of overall mortality, mental health ED visits and alcohol retail locations were lower across increasing quintile of ethnic concentration and the rate of gonorrhea incidence was lower across increasing quintile of dependency.

Fig. 1.

Rates of health and social outcomes across quintiles of and dimensions of the 2016 Ontario Marginalization Index: age-standardized overall mortality rates (2015), age-standardized gonorrhea incidence rates (2016), age-standardized mental health ED visits rates among age 15+ (2016), and offsite alcohol retail locations per 100,000 population (2018/2019)

The RII and 95% confidence intervals summarizing the inequalities in rates of the outcomes across quintiles of ON-Marg are presented in Table 4. Statistically significant RII values were found for all outcomes and dimensions, suggesting the differences observed in Fig. 1 represent meaningful social gradients and not random variability. The highest RII value, indicating the strongest positive association, was in the relationship between gonorrhea incidence and residential instability, while the smallest RII value of less than 1, indicating the strongest protective association, was in the relationship between per capita alcohol retail location and ethnic concentration.

Table 4.

Relative Index of Inequality (RII) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for rates of overall mortality, gonorrhea incidence, mental health ED visits, and alcohol retail locations for the four dimensions of the 2016 Ontario Marginalization Index

| Dimension of marginalization | Outcome | RII | 95% CI of the RII |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dependency | Overall mortality | 1.34 | (1.17 – 1.52) |

| Gonorrhea incidence | 0.65 | (0.56 – 0.76) | |

| Mental health ED visits | 1.83 | (1.60 – 2.09) | |

| Alcohol retail locations | 2.95 | (1.37 – 6.37) | |

| Ethnic concentration | Overall mortality | 0.65 | (0.59 – 0.71) |

| Gonorrhea incidence | 2.18 | (1.77 – 2.69) | |

| Mental health ED visits | 0.56 | (0.49 – 0.64) | |

| Alcohol retail locations | 0.19 | (0.11 – 0.34) | |

| Material deprivation | Overall mortality | 1.88 | (1.55 – 2.28) |

| Gonorrhea incidence | 1.93 | (1.58 – 2.35) | |

| Mental health ED visits | 3.33 | (2.69 – 4.13) | |

| Alcohol retail locations | 1.72 | (1.26 – 2.35) | |

| Residential instability | Overall mortality | 1.84 | (1.54 – 2.20) |

| Gonorrhea incidence | 4.93 | (3.86 – 6.28) | |

| Mental health ED visits | 3.64 | (2.85 – 4.65) | |

| Alcohol retail locations | 3.08 | (1.58 – 5.98) |

Discussion

This paper described the development of the 2011 and 2016 versions of the ON-Marg and assessed whether the change in data sources in 2011 affected the stability of the factorial structure and the consistency of DA-level measures of marginalization over time. Despite the loss of 2011 LFC data, we successfully created a 2011 version of ON-Marg by deriving similar measures from alternative administrative data sources for nine of the original 11 LFC indicators. The factor structure of the 2011 version is similar to the 2006 and 2016 versions, with the largest differences in the material deprivation dimension (e.g., inability to replace two indicators resulted in higher factor loading for some variables). With the return of the LFC in the 2016 census, ON-Marg used exclusively census data.

Linking DAs across time, we conducted an assessment of the consistency of ON-Marg quintiles across the 2006, 2011 and 2016 versions of ON-Marg. Due to natural shifts in demographic characteristics of DAs over time, some amount of change in the distribution of marginalization as measured by the index is expected. Indeed, between 2006 and 2016, 45.2% to 63.7% of DAs did not change quintiles, while 32.3% to 40.0% of DAs experienced a limited change of +/–1 quintile (Table 3). While shifting demographics are expected to cause some of the changes observed in 2011, the loss of the LFC in 2011 and the use of alternative data sources to measure certain variables mean that it is possible that changes observed in 2011 were affected by both real changes in patterns of marginalization in Ontario and changes in how variables were defined.

Of the subset of DAs that did not change quintiles between 2006 and 2016, 57.5% to 74.1% were assigned to the same quintile in the 2011 version of ON-Marg. A change of +/–1 quintile was observed for 24.1% to 33.8% of DAs, which is within the range of typical change observed across all DAs between 2006 and 2016, and as noted by other authors (Gamache and Hamel, 2017), is considered a limited change over time. More aberrant quintile assignment of ≥+/–2 quintiles was observed for only 1.8% to 8.7% of DAs, with the material deprivation dimension showing the least consistency in 2011. Caution should be taken when using ON-Marg 2011 at a subprovincial level to determine whether these outlier DAs are concentrated within subregions of interest and potentially impact the consistent measurement of marginalization in 2011 for a given area.

The analysis of associations between the dimensions of 2016 and the four health and societal outcomes shows how the index can be linked with a variety of data sources commonly used in public health surveillance in Ontario where data on socio-economic status (SES) are not available. This allows for measurement of health and social gradients across different dimensions of marginalization for a wide range of outcomes. In this way, ON-Marg allows researchers to explore how geographic variations in rates of an outcome are related to underlying social and economic marginalization, so that policy stakeholders better understand the potential mechanisms that drive health inequalities.

ON-Marg was associated with significant health and social gradients across quintiles of marginalization. We found material deprivation and residential instability to be positively associated with higher rates of overall mortality, gonorrhea incidence, mental health ED visits, and alcohol retail locations in Ontario. These trends reflect the literature about the impacts that both low SES (Bushnik et al., 2020; Kivimäki et al., 2020; Collins, 2016) and neighbourhood cohesion (Elliott et al., 2014; Robinette et al., 2013) have on health. While some research shows a curvilinear relationship between alcohol consumption and SES (Collins, 2016), we found a fairly step-wise gradient, possibly because retail locations are a measure of access rather than pure consumption. Alcohol access has been linked to alcohol harms in Ontario (Myran et al., 2019), and further investigation is required to differentiate patterns of alcohol access and use stratified by SES. The associations of ethnic concentration with lower rates of overall mortality, mental health ED visits and alcohol retail locations may reflect the “healthy immigrant effect” (Hansson et al., 2012; Lu and Ng, 2019). The positive association between ethnic concentration and incidence of gonorrhea and the negative association between dependency and gonorrhea both warrant additional research to better understand the nature of these relationships and potential public health implications (Zygmunt et al., 2020).

Limitations

This study is subject to some limitations. Without a 2011 long-form census to compare with, it is difficult to know whether changes in ON-Marg 2011 are related to changes in measurement, or real changes in the population. This analysis instead describes the overall consistency of ON-Marg by assessing DA-level changes in quintile assignment in the 2006, 2011 and 2016 versions of ON-Marg. Due to their small population size, individual DAs are susceptible to instability from random fluctuations related to population turnover, residential developments, and random rounding applied by Statistics Canada to protect confidentiality. This study groups DAs into quintiles, and does not consider the impacts of using other groupings (e.g., deciles) or factor scores directly. Additionally, by focusing on DAs without a quintile change between 2006 and 2016, this study has limited capacity to assess the impact that the 2011 alternative data sources had for areas which changed quintile between 2006 and 2016. Finally, our aspatial approach is not able to detect whether changes in 2011 are clustered at a subprovincial level, which may occur if factor scores in a given subgeography may have been strongly influenced by LFC indicators which were replaced or unavailable in 2011. Despite these challenges, this study is able to provide practical utility for ON-Marg users by clearly demonstrating that the use of alternative data sources does not cause a large number of Ontario DAs to produce unexpected quintile values in 2011.

There are limitations to consider when using ON-Marg to assess health and social inequalities. Due to misalignment of postal codes with DA boundaries, the PCCF+ relies on probabilistic matching to assign postal codes to a DA. Compared with urban areas, PCCF+ is generally less accurate in assigning DAs in rural areas where postal codes are large and more likely to match with multiple DAs (Pinault et al., 2020). Additionally, ON-Marg scores are not produced for every Ontario DA, due to incomplete census enumeration of areas that include Indigenous Reserves as well as data suppression rules used by Statistics Canada. As a result, rural and Indigenous populations in Ontario are not as well represented in ON-Marg. Finally, although the dimensions themselves are multi-faceted, the analyses presented here describe simple cross-sectional correlations between ON-Marg dimensions and health and social outcomes. Apart from age-standardizing the rates of health outcomes, no other variables were incorporated into this analysis, and further study may be required to fully understand how the dimensions of ON-Marg are related to inequalities in the rates of these outcomes.

Conclusion

While the 2011 version of ON-Marg comprises different measurement of some of the original variables derived in the other versions of the index, it is comparable with 2006 and 2016 in its dimensional structure. While there was some differentiation in quintile assignment across census years, a high degree of consistency was observed within all four dimensions. Patterns of immigration, language, ethnicity, household size and structure, and so forth are associated with health and/or health care outcomes. These patterns have changed substantially over time and are not fully captured in traditional deprivation indices. ON-Marg offers a more comprehensive conceptualization of the social forces and marginalization processes that shape the lives of Ontario residents. It is an empirically derived and theoretically informed tool that captures inequalities beyond the construct of deprivation.

Contributions to knowledge

What does this study add to existing knowledge?

This paper describes the creation of the 2011 and 2016 Ontario Marginalization Index.

The findings show that the use of alternative data sources in the 2011 version did not meaningfully impact its ability to consistently measure marginalization in Ontario.

What are the key implications for public health interventions, practice or policy?

The updated Ontario Marginalization Index is a powerful tool for measuring health inequalities that allows users to understand how geographic variations in health and social outcomes are related to underlying social and economic marginalization.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by Public Health Ontario, MAP Centre for Urban Health Solutions, St. Michael’s Hospital, and Dalla Lana School of Public Health, University of Toronto. The creation of the 2011 ON-Marg Index was supported by ICES, which is funded by an annual grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health (MOH) and the Ministry of Long-Term Care (MLTC). The opinions, results and conclusions reported in this article are those of the authors and are independent from the funding sources. No endorsement by ICES, MOH or MLTC is intended or should be inferred. Parts of ON-Marg 2011 are based on data and information compiled and provided by the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI) and Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC). However, the analyses, conclusions, opinions and statements expressed herein are those of the authors, and not necessarily those of MOH, MLTC, CIHI or IRCC. The authors wish to thank Gary Moloney for his contributions to ON-Marg 2016 and Aya Mahder Bashi for her contributions to the gonorrhea incidence analysis.

Availability of data and material

The Ontario Marginalization Index is available at https://www.publichealthontario.ca/en/data-and-analysis/health-equity/ontario-marginalization-index or http://www.ontariohealthprofiles.ca/onmargON.php. All other data used in this study are not publicly available.

Code availability

Not applicable

Appendix

Table. 5.

ICD-10 codes for selected mental illnesses

| Condition | ICD-10 code |

|---|---|

| Substance-related disorders | F10 – F19, F55 |

| Schizophrenia, delusional and non-organic psychotic disorders | F20 – F29 |

| Mood/affective disorders | F30 – F34, F38.0, F38.1, F38.8, F39, F53.0 |

| Anxiety disorders | F40, F41, F42, F43.0, F43.1, F43.8. F43.9, F93.0, F93.1, F93.2 |

| Selected disorders of adult personality and behavior | F60, F61, F62, F68, F69 |

Author contributions

TVI and FM conceived and drafted the manuscript. TVI created the analytic plan and ran all analyses. All the authors edited, critically reviewed and approved the final content of the manuscript.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Board of St. Michael’s Hospital (#16-016) and the Ethics Review Board of Public Health Ontario (#2016-016.03).

Consent to participate

Not applicable

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Trevor van Ingen, Email: trevor.vaningen@oahpp.ca.

Flora I. Matheson, Email: flora.matheson@unityhealth.to

References

- Boyd PA, Armstrong B, Dolk H, Botting B, Pattenden S, Abramsky L, et al. Congenital anomaly surveillance in England—ascertainment deficiencies in the national system. BMJ. 2004;330(7481):27. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38300.665301.3A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryere J, Pornet C, Copin N, Launay L, Gusto G, Grosclaude P, et al. Assessment of the ecological bias of seven aggregate social deprivation indices. BMC Public Health. 2016;17(1):86. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-4007-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bushnik, T., Tjepkema, M., & Martel, L. (2020). Socioeconomic disparities in life and health expectancy among the household population in Canada. Health Reports. Ottawa: Catalogue no. 82-003-X. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Collins SE. Associations between socioeconomic factors and alcohol outcomes. Alcohol Research: Current Reviews. 2016;38(1):83–94. doi: 10.35946/arcr.v38.1.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott J, Gale CR, Parsons S, Kuh D, Team HS. Neighbourhood cohesion and mental wellbeing among older adults: a mixed methods approach. Social Science & Medicine. 2014;107:44–51. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forer, B., Minh, A., Enns, J., Webb, S., Duku, E., Brownell, M., et al. (2020). A Canadian neighbourhood index for socioeconomic status associated with early child development. Child Indicators Research. 10.1007/s12187-019-09666-y.

- Gamache, P., & Hamel, D. (2017). The challenges of updating the deprivation index with data from the 2011 Census and the National Household Survey (NHS). Institut national de santé publique du Québec

- Hansson EK, Tuck A, Lurie S, McKenzie K. Rates of mental illness and suicidality in immigrant, refugee, ethnocultural, and racialized groups in Canada: A review of the literature. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2012;57(2):111–121. doi: 10.1177/070674371205700208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J., & Mueller, C. (1978a). Factor analysis: Statistical methods and practical issues. Sage Publications.

- Kim, J., & Mueller, C. (1978b). Introduction to factor analysis: What it is and how to do it. CA: Sage Publications.

- Kivimäki M, Batty GD, Pentti J, Shipley MJ, Sipilä PN, Nyberg ST, et al. Association between socioeconomic status and the development of mental and physical health conditions in adulthood: A multi-cohort study. The Lancet Public Health. 2020;5(3):e140–e149. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(19)30248-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachaud J, Donnelly P, Henry D, Kornas K, Fitzpatrick T, Calzavara A, et al. Characterising violent deaths of undetermined intent: A population-based study, 1999-2012. Injury Prevention. 2018;24(6):424–430. doi: 10.1136/injuryprev-2017-042376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu, C., & Ng, E. (2019). Healthy immigrant effect by immigrant category in Canada. Health Reports, Catalogue no. 82-003-X [DOI] [PubMed]

- Matheson, F. I., Dunn, J. R., Smith, K. L. W., Moineddin, R., & Glazier, R. H. (2012a). Ontario Marginalization Index user guide. Centre for Research in Inner City Health, St Michael’s Hospital.

- Matheson, F. I., Dunn, J. R., Smith, K. L. W., Moineddin, R., & Glazier, R. H. (2012b). Canadian Marginalization Index user guide. Centre for Research in Inner City Health, St Michael’s Hospital

- Matheson FI, Dunn JR, Smith KLW, Moineddin R, Glazier RH. Development of the Canadian Marginalization Index: A new tool for the study of inequality. Canadian Journal of Public Health. 2012;103:S12–S16. doi: 10.1007/BF03403823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moin, J. S., Moineddin, R., & Upshur, R. E. G. (2018). Measuring the association between marginalization and multimorbidity in Ontario, Canada: A cross-sectional study. Journal of Comorbidity, 8(1) 2235042X18814939. 10.1177/2235042X18814939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Moreno-Betancur M, Latouche A, Menvielle G, Kunst AE, Rey G. Relative index of inequality and slope index of inequality: A structured regression framework for estimation. Epidemiology. 2015;26(4):518–527. doi: 10.1097/ede.0000000000000311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myran DT, Chen JT, Giesbrecht N, Rees VW. The association between alcohol access and alcohol-attributable emergency department visits in Ontario, Canada. Addiction. 2019;114(7):1183–1191. doi: 10.1111/add.14597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peel Public Health. (2011). Health in Peel: Determinants and disparities. Region of Peel. https://www.peelregion.ca/health/health-status-report/determinants/pdf/MOH-0036_Determinants_final.pdf. Accessed 1 June 2020.

- Pinault L, Khan S, Tjepkema M. Accuracy of matching residential postal codes to census geography. Health Reports. 2020;31(3):3–13. doi: 10.25318/82-003-x202000300001-eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinette JW, Charles ST, Mogle JA, Almeida DM. Neighborhood cohesion and daily well-being: Results from a diary study. Social Science & Medicine. 2013;96:174–182. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.07.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossen LM. Neighbourhood economic deprivation explains racial/ethnic disparities in overweight and obesity among children and adolescents in the USA. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2014;68(2):123. doi: 10.1136/jech-2012-202245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Santos MT, Mesa-Frias M, Choi M, Nüesch E, Asunsolo-Del Barco A, Amuzu A, et al. Area-level deprivation and overall and cause-specific mortality: 12 years' observation on British women and systematic review of prospective studies. PLoS One. 2013;8(9):e72656–e72656. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0072656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah BR, Chiu M, Amin S, Ramani M, Sadry S, Tu JV. Surname lists to identify South Asian and Chinese ethnicity from secondary data in Ontario, Canada: A validation study. BMC Medical Research Methodology. 2010;10(1):42. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-10-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman JD, Hutchison MG, Cusimano MD. Association between neighbourhood marginalization and pedestrian and cyclist collisions in Toronto intersections. Canadian Journal of Public Health. 2013;104(5):e405–e409. doi: 10.17269/cjph.104.4053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons E, Dell SD, Moineddin R, Toe T. Neighborhood material deprivation is associated with childhood asthma development: Analysis of prospective administrative data. Canadian Respiratory Journal. 2019;2019:6808206. doi: 10.1155/2019/6808206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada. (2011). Income reference guide national household survey. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 99-014-X2011006.

- Tobias MI, Cheung J. Monitoring health inequalities: Life expectancy and small area deprivation in New Zealand. Population Health Metrics. 2003;1(1):2. doi: 10.1186/1478-7954-1-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zygmunt A, Tanuseputro P, James P, Lima I, Tuna M, Kendall CE. Neighbourhood-level marginalization and avoidable mortality in Ontario, Canada: A population-based study. Canadian Journal of Public Health. 2020;111(2):169–181. doi: 10.17269/s41997-019-00270-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The Ontario Marginalization Index is available at https://www.publichealthontario.ca/en/data-and-analysis/health-equity/ontario-marginalization-index or http://www.ontariohealthprofiles.ca/onmargON.php. All other data used in this study are not publicly available.