Summary

The thermal stability of the catalysts is of particular importance but still a big challenge for working under harsh conditions at high temperature. In this study, we report a strategy to improve the thermal stability of the ceria-based catalyst via introducing Sn. XRD, Rietveld refinement, and other characterizations results indicated that the formation of Sn-Co solid solution plays a key role in the thermal stability of the catalyst. The developed ternary 3%Co/Ce0.5Sn0.5O2 catalyst not only exhibits outstanding thermal stability and resistance to SO2 and H2O for soot oxidation from diesel vehicle exhaust but also remains extraordinary thermal stability for CO oxidation. Remarkably, even after thermal aging at 1000°C, it still possessed high catalytic activity similar to that of the fresh catalyst.

Subject areas: Chemistry, Catalysis, Thermal property, Materials characterization

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

The developed 3%Co/Ce-Sn catalyst processes extraordinary thermal stability

-

•

The Sn species could restrain the aggregation of Co active component

-

•

The Sn-Co solid solution plays a key role in improving the thermal stability

-

•

The 3%Co/Ce-Sn catalyst exhibited perfect and stable resistance to H2O and SO2

Chemistry; Catalysis; Thermal property; Materials characterization

Introduction

With the rapid development of catalytic science and technology, catalytic materials are applied widely in environment, devices, biomedicine, and so on. During these applications, the catalytic materials are placed under all kinds of harsh conditions, such as high temperature environment and so forth. Therefore, thermal stability is often a crucial feature determining the practical application of catalysts (Xu et al., 2018; Yang et al., 2019; Liu et al., 2018; Yan et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2017).

To improve the thermal stability of the catalysts, great efforts have been devoted. For example, Xu et al. reported a novel entropy-driven strategy to stabilize Pd single atom on the high-entropy fluorite oxides, which exhibited excellent resistance to thermal and hydrothermal degradation (Xu et al., 2020). In addition, modifying with dopants is also applied to resist the sintering of active components. For the three-way catalysts (TWCs) applied in the gasoline engine aftertreatment, Zr is added into CeO2 to resist the aggregation of active components (Pt, Pd, and Rh) and stabilize the ability of oxygen storage (Farrauto et al., 2019; Monte et al., 2004). Compared with gasoline engines, diesel engines are widely used owing to high fuel efficiency, durability, and excellent dynamic performance. Yet, the development of aftertreatment catalysts with excellent thermal stability still remains a huge challenge in diesel emission control. When the DPF is regenerated to remove the collected particulate matter, the peak temperature inside the DPF can even reach 1000°C (Guo and Zhang, 2007; Yu et al., 2013a, 2013b). Thus, not only high catalytic activity but also good thermal stability is essential for the aftertreatment catalysts, such as CO oxidation and soot oxidation catalysts. For instance, a MnOx-CeO2-Al2O3 catalyst for soot oxidation reported by Wu et al. (2011) exhibited good thermal stability, due to the introduction of stabilized Al2O3 and its maximum soot oxidation only shifted upward by 53°C after aging treatment at 800°C for 20 h. In addition, Zr doping has been reported to be able to improve the thermal stability of CeO2 calcined at 1000°C, but the T50 of soot oxidation for the obtained Ce-Zr mixed oxide was only about 20°C lower than that without a catalyst (Atribak et al., 2008).

Above all, the development of the catalysts with excellent thermal stability is still urgently needed for industrial catalytic application, especially for those involving high-temperature environment. However, the previously reported aftertreatment catalysts usually cannot hold their activity after thermal aging even at 800°C. Therefore, the thermal stability of this type of catalysts remains a formidable challenge.

In our previous development of the catalysts for selective catalytic reduction of NOx with NH3 (NH3-SCR), it was found that SnO2 can remarkably promote a Ce-W mixed oxides catalyst for sintering resistance at high temperatures, which was related to the preservation of highly dispersed Ce-W species induced by Sn (Liu et al., 2021). In addition, it was reported that doping Sn could also improve the oxygen storage capacity (OSC) of CeO2-based materials because the reversible Sn4+ ⇋ Sn2+ redox process involves two electrons transfer (Liu et al., 2015; Mukherjee et al., 2018). For instance, Chang et al. found Sn-modified MnOx-CeO2 catalysts presented nearly 100% NOx conversion at 110°C–230°C, which is associated with that doping of Sn can promote the formation of oxygen vacancies and facilitate NO oxidation to NO2 (Chang et al., 2013). In Sasikala’s work, it was found that a Ce-Sn mixed oxide exhibited better catalytic activity for CO oxidation reaction as comparing with their pure oxides due to a synergetic effect between Ce and Sn (Sasikala et al., 2001). Therefore, Sn is very attractive for the development of the catalysts with excellent activity and thermal stability. Herein, we report a facile strategy to develop outstanding thermally stable non-noble catalyst via introducing Sn. A series of Ce1-xSnxO2 supports with different Ce/Sn molar ratios were prepared by a co-precipitation method, and then Co was loaded on the optimal Ce0.5Sn0.5O2 support (Figure S1) by the impregnation method. All catalysts were calcined at 700°C for 3 h. Meanwhile, the optimal 3%Co/Ce0.5Sn0.5O2 catalyst (Figure S2) was calcined at 500, 700, 900, and 1000°C for 3 h for the thermal stability tests.

Results and discussion

Figure 1 displays a series of elemental mapping images of the catalysts aging at different temperatures. As shown in Figure 1A, with the increase of aging temperature, Co3O4 phase over the 3%Co/CeO2 catalyst was aggregated, indicating that aging treatment has a negative effect on the 3%Co/CeO2. Yet, the introduction of Sn could restrain the aggregation of Co3O4, as confirmed by the elemental mapping and TEM imagines in Figures 1B, S3, and S4. In addition, the surface areas values of the as-prepared catalysts are presented in Table S1. The results showed that the specific surface areas of all the catalysts decreased with the increase of aging temperatures. Yet, after thermal aging at high temperatures (900 and 1000°C), the developed ternary 3%Co/Ce0.5Sn0.5O2 catalyst exhibited larger surface area than 3%Co/CeO2, indicating that the addition of Sn had a positive effect on the specific surface area.

Figure 1.

Element distributions measurements

EDS elemental mapping images of the (A) 3%Co/CeO2 and (B) 3%Co/Ce0.5Sn0.5O2 catalysts at different aging temperatures.

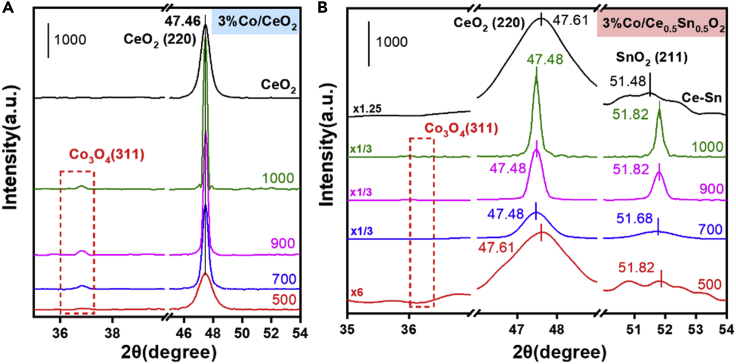

The crystal structures of the 3%Co/CeO2 and 3%Co/Ce0.5Sn0.5O2 catalysts subjected to different aging temperatures were examined by XRD (Figures 2, S5, and S6). For the 3%Co/CeO2 catalyst calcined at 500°C, it exhibited the structures of cubic fluorite CeO2 (PDF#43-1002), and no peaks of any Co species were observed. Figure 2A shows that there is no shift for the peak of (220) crystal face of CeO2 in the 3%Co/CeO2 catalyst, in comparation with the pure CeO2 sample. These results indicated that Co species were highly dispersed on the CeO2 surface rather than existing as Ce-Co solid solutions (He et al., 2018; Venkataswamy et al., 2015). Moreover, when the aging temperature increased to 700, 900, and 1000°C, cubic Co3O4 phase was detected, and the crystallite size of Co3O4 calculated by the Scherrer formula (in Table S1) also increased gradually for the 3%Co/CeO2 catalyst (shown in Figure 2A), which can be attributed to the sintering of the active Co component.

Figure 2.

XRD analysis

XRD patterns of (A) 3%Co/CeO2 and (B) 3%Co/Ce0.5Sn0.5O2 catalysts at different aging temperatures.

Amazingly, as presented in Figures S2B and S5B, no peaks of the Co3O4 phase were found for the 3%Co/Ce0.5Sn0.5O2 catalyst, even after thermal aging at 1000°C. The patterns of 3%Co/Ce0.5Sn0.5O2 catalyst calcined at 700°C (shown in Figure S6A) mainly showed the typical peaks of CeO2 (PDF#43-1002) and SnO2 (PDF#41-1445). Figures S6B and S6C depict the enlarged drawing of XRD patterns, corresponding to the (220) facet of CeO2 and the (211) facet of SnO2 in the Ce0.5Sn0.5O2 and 3%Co/Ce0.5Sn0.5O2 catalysts. With the addition of Co, the peak of the (211) facet of SnO2 shifted to higher diffraction angle, indicating the formation of Sn-Co solid solution. Yet, the peak of the (220) facet of CeO2 shifted to lower diffraction angle, which could be due to the occurrence of Sn phase segregation from Ce-Sn solid solution (see Figures S7 and S8A in supplemental information). Figure 2B showed that the peak of the (220) facet of CeO2 in aged 3%Co/Ce0.5Sn0.5O2 shifted to lower diffraction, while the peak of the (211) facet of SnO2 still located at higher diffraction angle than the Ce0.5Sn0.5O2 catalyst, which suggested the still existence of Sn-Co solid solution. In addition, a new phase of Co2SnO4 was detected for the 3%Co/Ce0.5Sn0.5O2 catalyst aging at 900°C and 1000°C (Figure S9), which further indicated that Co preferred to interact with Sn species.

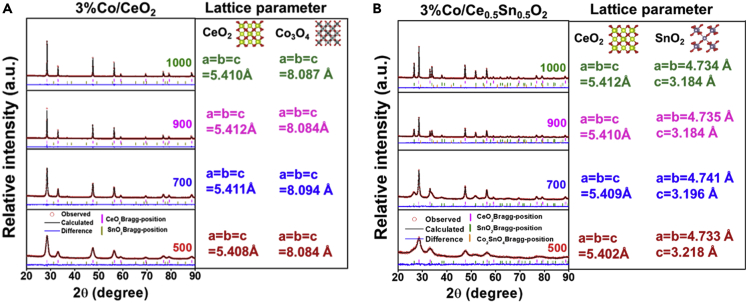

Rietveld refinement was performed using Fullprof Suite to obtain precise lattice parameters (Rodriguez-Carvajal, 1993), and the results are described in Figures 3 and S8. Figure 3A shows the refined XRD patterns of the 3%Co/CeO2 catalysts aging at different temperature and the a, b, and c values of CeO2 were almost equal to the pure CeO2 sample (shown in Figure S8A), which further revealed that Co3O4 ought to exist mainly as dispersed crystallites rather than Ce-Co solid solutions. As shown in Figure S8B, the c value of SnO2 in 3%Co/Ce0.5Sn0.5O2 catalyst was smaller than that in Ce0.5Sn0.5O2, while the a, b, and c values of CeO2 were slightly larger than those of the Ce0.5Sn0.5O2 catalyst. These results indicated that the Co was doped to SnO2 instead of CeO2 lattice. Thus, the Sn-Co solid solution formed through the replacement of Sn4+ (0.071 nm) by smaller Co3+ (0.061 nm). The lattice parameters of CeO2, SnO2, and Co2SnO4 in the aged 3%Co/Ce0.5Sn0.5O2 catalysts obtained by Rietveld refinement are shown in Figure 3B. The c values of SnO2 in the aged 3%Co/Ce0.5Sn0.5O2 are still smaller than that in the Ce0.5Sn0.5O2 catalyst (shown in Figure S8A). It suggested that Sn-Co solid solution was not destroyed by high-temperature treatment. Additionally, the Co2SnO4 phase was also identified by Rietveld refinement, and the results are shown in Figure S8C. The above results indicated that the introduction of Sn could improve the thermal stability via the formation of Sn-Co solid solution to restrain the aggregation of Co3O4.

Figure 3.

Rietveld refinement of XRD patterns

Rietveld refined XRD patterns of the (A) 3%Co/CeO2 and (B) 3%Co/Ce0.5Sn0.5O2 catalysts at different aging temperatures.

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) technology was employed to explore the surficial properties of the as-prepared catalysts, and the results are shown in Figures 4 and S10. As the aging temperature increases, the proportion of Co2+/Co3+ and Ce3+/Ce4+ on the surface of the 3%Co/CeO2 catalyst gradually decreased. As is well known, the higher the Ce3+ and Co2+ concentration in these samples, the more oxygen defects are generated (Zhao et al., 2019; Liu et al., 2009). Therefore, the surface oxygen defects associating with the Co2+ and Ce3+ of the 3%Co/CeO2 catalyst gradually disappeared, with the increase of aging temperature (Zhao et al., 2019; Cui et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2018; Ren et al., 2019). Figure S10 showed that the O 1s spectra of all catalysts can be deconvoluted into two kinds of O species, with the peak at higher binding energy being attributed to the surface oxygen species (Oα) and the peak at lower binding energy being ascribed to the lattice oxygen species (Oβ) (Xu et al., 2020; Ren et al., 2019; Sellers-Anton et al., 2020). The ratio of Oα/Oβ over the 3%Co/CeO2 catalyst decreased obviously with the increase of aging temperature. Yet, after introducing the Sn, the amount of surface Co2+, Ce3+, and Oα for the catalysts aged at different temperatures did not change significantly. In addition, the results of H2-TPR (Figure S11) showed that with the addition of Sn, the H2 consumption significantly increased, which indicated that Sn addition is beneficial to the formation of active oxygen species.

Figure 4.

Analysis of the surficial properties

The ratios of Co2+/Co3+, Ce3+/Ce4+, and Oα/Oβ ratios of as-prepared catalysts at different aging temperatures.

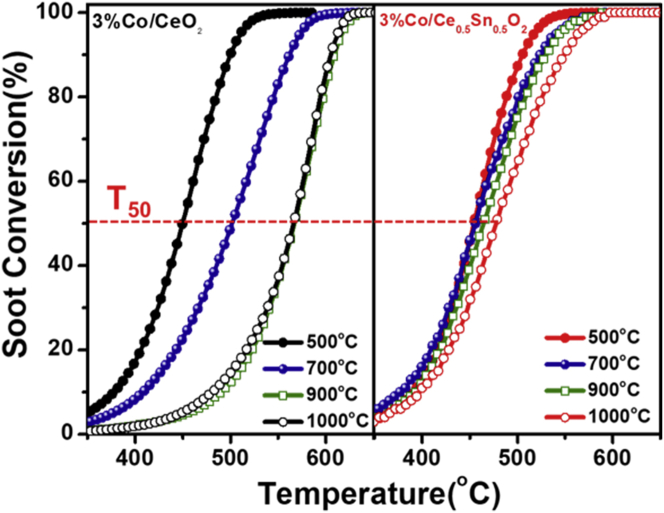

According to the above characterization results, the addition of Sn can protect the active Co component of the 3%Co/Ce0.5Sn0.5O2 catalyst via the formation of Sn-Co solid solution, and the aged catalysts exhibited similar amounts of surface Oα with the fresh one. Surface-active oxygen species play a significant role in many heterogeneous catalytic reactions, including solid-solid-gas and gas-gas-solid reactions. For solid-solid-gas reaction, soot oxidation is a typical represent and the catalyst would undergo high-temperature oxidation process in the actual application. Thus, we tested the catalytic performance of soot oxidation for the catalysts to verify whether the catalyst with Sn introduction possess stable catalytic activity. As shown in Figure 5, the 3%Co/Ce0.5Sn0.5O2 catalyst indeed exhibited extraordinarily thermal stability, with high soot conversion activity still maintaining even after aging at 1000°C, indicating its high resistance to thermal shock. For a comparative study, we tested the soot oxidation performances of the 3%Co/CeO2 catalyst aged at different temperatures. The results showed that the soot combustion temperature over the 3%Co/CeO2 catalyst increased sharply with the increase of aging temperature, while that over 3%Co/Ce0.5Sn0.5O2 did not show a noticeable increase after aging at different temperatures from 500°C to 1000°C. In addition, even after 1000°C aging, the CO2 selectivity of the 3%Co/Ce0.5Sn0.5O2 catalyst was still nearly 100%, while that of the 3%Co/CeO2 catalyst decreased remarkably (Figure S12). These results indicate that Sn plays a key role in the thermal stability of the 3%Co/Ce0.5Sn0.5O2 catalyst. As we all know, the presence of sulfur compounds in diesel fuels and water vapor in the exhaust gas is almost unavoidable. Therefore, tolerance of the SO2 and H2O in diesel exhaust also plays an important role in the application of a soot oxidation catalyst. Figures S13 and S14 showed that the 3%Co/Ce0.5Sn0.5O2 catalyst possess high and stable resistance to H2O and SO2, which was of extraordinary importance for its practical application.

Figure 5.

Soot conversion of the catalysts with different aging temperatures during temperature-programmed oxidation of soot

Reaction conditions: 0.1% NO and 10% O2 balanced by N2, under loose contact mode, GHSV = 300,000 mL g−1·h−1, and heating rate = 10°C/min.

Moreover, there are also many gas-gas-solid reactions, in which the catalysts could be exposed to high-temperature conditions, such as catalytic elimination of emissions including CO, NO, HC, and so on from internal combustion engines. Therefore, CO-TPO experiment was also applied to further investigate whether the catalyst with doping Sn exhibited outstanding stability for CO oxidation, and the results are shown in Figure S15. It was found that the activity of 3%Co/CeO2 decreased gradually with the aging temperature increasing from 500°C to 1000°C. Yet, the 3%Co/Ce0.5Sn0.5O2 catalyst exhibited stable activity for CO oxidation, even after 1000°C aging (Figure S15B), which further confirmed that the introduction of Sn is the key to improve the stability of the catalyst.

Conclusion

In summary, we developed an extraordinary 3%Co/Ce0.5Sn0.5O2 catalyst with outstanding thermal stability. The characterization results indicated that the introduction of Sn species induced the formation of Sn-Co solid solution to restrain the aggregation of the Co active component. Moreover, the results of soot and CO oxidations further illustrate the addition of Sn can remarkably improve the stability of the 3%Co/CeO2 catalyst. This study offers an efficient strategy toward developing the catalyst with outstanding thermal stability. Further optimization of this catalyst and investigation of the reaction mechanism are underway.

Limitations of the study

In this work, it provides a new and efficient strategy toward developing the catalyst with excellent thermal stability. For the analysis of surficial properties of the as-prepared catalysts, only XPS was used. Based on previous studies, the Co 2p spectra were deconvoluted into Co 2+ and Co3+, and the O 1s spectra were deconvoluted into surface oxygen species (Oα) and lattice oxygen species (Oβ). More evidence of surficial properties, such as in situ XPS, in situ XAFS analysis and so on, is needed to further strengthen the conclusion. In addition, the reaction mechanism of soot and CO oxidation over the developed catalyst should be investigated in future work.

STAR★Methods

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| Ce(NO3)3·6H2O | Tianjin Fuchen Chemical Reagent Factory | CAS 10294-41-4 |

| SnCl4·5H2O | Shanghai Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd | CAS 10026-06-9 |

| Co(NO3)2·6H2O | Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd | CAS 10026-22-9 |

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Wenpo Shan (wpshan@iue.ac.cn)

Materials availability

Materials generated in this study will be made available on reasonable request, but we may require a payment or a completed Materials Transfer Agreement if there is potential for commercial application.

Method details

Catalyst preparations

The catalyst was synthesized by a co-precipitation method. Ce(NO3)3·6H2O and SnCl4·5H2O, with different Ce/Sn molar ratios (Ce : Sn=3:1 of 6 g Ce(NO3)3·6H2O and 1.61 g SnCl4·5H2O, Ce : Sn=1:1 of 6 g Ce(NO3)3·6H2O and 4.85 g SnCl4·5H2O, Ce : Sn=1:3 of 2.49 g Ce(NO3)3·6H2O and 6 g SnCl4·5H2O), were dissolved together in deionized water. Then the above aqueous solution was added dropwise into another mixed solution consisting of H2O : NH3·H2O : H2O2 = 4:4:1 (H2O=80 ml, NH3·H2O=80 ml, and H2O2=20 ml) under vigorous mixing. Next, the obtained suspension was ultrasonicated for 30 minutes, stirred for 1 hour, and washed to neutral pH. The as-prepared precipitate was dried at 110°C for 12 h, and then calcined at 700°C for 3 h in air. The catalysts were named as CexSn1-xO2, which did not mean the Ce and Sn species existing as CeO2-SnO2 solid solution. CeO2 and SnO2 were also synthesized using the same method as reference samples.

Three different theoretical Co loadings, 1%, 3% and 5% with regards to the weight of the support (2 g), were used to investigate the effect of Co loading on the oxidation reaction. Co loading was performed via wetness impregnation with appropriate amounts of an aqueous solution of Co(NO3)2·6H2O (0.099 g Co(NO3)2·6H2O of 1%, 0.296 g Co(NO3)2·6H2O of 3%Co, and 0.494 g Co(NO3)2·6H2O of 5%). The obtained mixture was ultrasonicated for 30 minutes and stirred for 1 h. Then, the mixture was subjected to a rotary evaporation process to remove water. Finally, the obtained powders were dried at 110°C overnight, then the powders were calcined at 700°C for 3 h in air. For comparison, the 3%Co/CeO2 catalyst was synthesized using the same methods as above. The obtained catalysts were named as 1%Co/Ce0.5Sn0.5O2, 3%Co/Ce0.5Sn0.5O2, 5%Co/Ce0.5Sn0.5O2, and 3%Co/CeO2, respectively. In addition, the 3%Co/Ce0.5Sn0.5O2 and 3%Co/CeO2 catalysts were also calcined at 500, 900, and 1000°C for 3 h, respectively, for the thermal stability tests.

Characterizations of the catalysts

The X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns were obtained on an X'Pert PRO instrument with Cu Kα radiation (λ= 1.5418) at 40 kV and 40 mA. Data were collected between 2θ=10-90°, with a scan step of 0.07°.

The Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) method was applied to measure the specific surface areas of the samples via N2 adsorption-desorption isotherms at − 196°C using an ASAP 2020N autoscore surface analyzer. The pore volume and pore-size were obtained by the BJH method using the desorption branch.

The morphologies and element mapping of the as-prepared catalysts were obtained with a high-resolution transmission Tecnai FEI-F20 electron microscope.

X-ray photo electron spectroscopy (XPS) results of the catalysts were obtained on a scanning X-ray micro probe (ESCALAB250I, Thermo Fisher scientific) using Al K α radiation. All of the binding energies were calibrated using the C 1s peak (BE = 284.8 eV) as standard.

H2-TPR was performed using a Micromeritics Auto Chem II 2920 automatic chemical adsorption analyzer. After pre-treatment under 5% O2 balanced by He at 500°C for 1 h, the 100 mg sample was heated from room temperature to 900°C at a constant rate (10°C/min) in a U-shaped quartz reactor under 10% H2/Ar mixture gas (30 ml/min). The hydrogen consumption was monitored with a TCD detector, which was calibrated by the signal generated by the introduction of the known amounts of hydrogen.

Catalytic activity measurements

Printex-U (Degussa) was used as model soot, with particle size and specific surface area of 25 nm and 100 m2/g, respectively. The catalytic activity was evaluated by a temperature programmed oxidation reaction, which was carried out in a continuous flow fixed bed reactor consisting of a quartz tube with 5 mm inner diameter. To make evaluation conditions close to actual practice, the loose contact was employed. Under the loose contact, the catalyst and soot were mixed for 2 minutes with a spatula. The mass ratio of catalyst to soot was 10:1, then 110 mg of the admixture was added to 300 mg of quartz sand with particle size from 40 to 60 mesh, in order to reduce air resistance and guard against reaction run off.

The reaction gas, including 1000 ppm NO (when used), 50 ppm SO2 (when used), 10% O2, and 5% H2O (when used), with N2 as balanced gas, was flowed into the fixed bed reactor at a total flow rate of 500 ml/min. The reaction temperature was increased from room temperature to 700°C at a heating rate of 10°C/min, which was measured by a K-type thermocouple in the fixed bed reactor. The outlet gases in the soot catalytic oxidation process, such as CO2, CO, NO and NO2, were detected by an Antaris IGS (Thermo Fisher) equipped with a heated, low-volume multiple-path gas cell (2 m).

Soot conversion and CO2 selectivity were calculated as follows:

| (Equation 1) |

The catalytic activity was described by the values of T10, T50, and T90, which were defined as the temperatures at 10%, 50%, and 90% soot conversion, respectively.

| (Equation 2) |

Ai is the total peak areas of CO2 and CO at a given temperature, At is the total peak areas of CO2 and CO overall, AiCO2 is the total peak area of CO2 at a given temperature, and AiCO is the total peak area of CO at a given temperature.

The CO oxidation activities for the prepared catalysts were also evaluated in a continuous flow fixed bed reactor using 100 mg catalysts in a gas mixture of 0.4% CO/10%O2/N2 at a flow rate of 500 ml/min. The reaction temperature was increased from room temperature to 700°C at a heating rate of 10°C/min, which was measured by a K-type thermocouple in the fixed bed reactor. The outlet gases, such as CO2 and CO, were detected by an Antaris IGS (Thermo Fisher) equipped with a heated, low-volume multiple-path gas cell (2 m).

CO conversion was calculated as follows:

| (Equation 3) |

Quantification and statistical analysis

Our study doesn’t include quantification and statistical analysis.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (51822811, 51908532), the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDA23010201), and the Science and Technology Innovation “2025” major program in Ningbo (2020Z103).

Author contributions

M. Wang: Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing-Original Draft, Review and Editing; Y. Zhang: Formal analysis, Data Curation, Supervision, Writing-Review and Editing, Project administration; W. Shan: Formal analysis, Supervision, Writing-Review and Editing, Project administration, Funding acquisition; Y. Yu: Data Curation, Writing - Review and Editing; J. Liu: Formal analysis, Review and Editing; H. He: Resources, Supervision, Funding acquisition.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Published: April 15, 2022

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2022.104103.

Contributor Information

Yan Zhang, Email: yzhang3@iue.ac.cn.

Wenpo Shan, Email: wpshan@iue.ac.cn.

Hong He, Email: honghe@rcees.ac.cn.

Supplemental information

Data and code availability

Data reported in this paper will be shared by the lead contact upon reasonable request.

This study does not report original code.

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the Lead Contact upon reasonable request.

References

- Atribak I., Bueno-López A., García-García A. Thermally stable ceria–zirconia catalysts for soot oxidation by O2. Catal. Commun. 2008;9:250–255. [Google Scholar]

- Chang H., Chen X., Li J., Ma L., Wang C., Liu C., Schwank J.W., Hao J. Improvement of activity and SO2 tolerance of Sn-modified MnOx-CeO2 catalysts for NH3-SCR at low temperatures. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013;47:5294–5301. doi: 10.1021/es304732h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui B., Zhou L., Li K., Liu Y.Q., Wang D., Ye Y., Li S. Holey Co-Ce oxide nanosheets as a highly efficient catalyst for diesel soot combustion. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. 2020;267:118670. [Google Scholar]

- Farrauto R.J., Deeba M., Alerasool S. Gasoline automobile catalysis and its historical journey to cleaner air. Nat. Catal. 2019;2:603–613. [Google Scholar]

- Guo Z., Zhang Z. Hybrid modeling and simulation of multidimensional processes for diesel particulate filter during loading and regeneration. Numer. Heat Tr. A-Appl. 2007;51:519. [Google Scholar]

- He H., Lin X., Li S., Wu Z., Gao J., Wu J., Wen W., Ye D., Fu M. The key surface species and oxygen vacancies in MnOx(0.4)-CeO2 toward repeated soot oxidation. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. 2018;223:134–142. [Google Scholar]

- Liu C., Xian H., Jiang Z., Wang L., Zhang J., Zheng L., Tan Y., Li X. Insight into the improvement effect of the Ce doping into the SnO2 catalyst for the catalytic combustion of methane. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. 2015;176-177:542–552. [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., He G., Shan W., Yu Y., Huo Y., Zhang Y., Wang M., Yu R., Liu S., He H. Introducing tin to develop ternary metal oxides with excellent hydrothermal stability for NH3 selective catalytic reduction of NO. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. 2021;291:120125. [Google Scholar]

- Liu W., Chen Y., Qi H., Zhang L., Yan W., Liu X., Yang X., Miao S., Wang W., Liu C., et al. A durable nickel single-Atom catalyst for hydrogenation reactions and cellulose valorization under harsh conditions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018;57:7071–7075. doi: 10.1002/anie.201802231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X., Zhou K., Wang L., Wang B., Li Y. Oxygen vacancy clusters promoting reducibility and activity of ceria nanorods. J. AM. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:3140–3141. doi: 10.1021/ja808433d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monte R.D., Fornasiero P., Desinan S., Kašpar J., Gatica J.M., Calvino J.J., Fonda E. Thermal stabilization of CexZr1-xO2 oxygen storage promoters by addition of Al2O3: effect of thermal aging on textural, structural, and morphological properties. Chem. Mater. 2004;16:4273. [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee D., Devaiah D., Venkataswamy P., Vinodkumar T., Smirniotis P.G., Reddy B.M. Superior catalytic performance of a CoOx/Sn–CeO2 hybrid material for catalytic diesel soot oxidation. New J. Chem. 2018;42:14149–14156. [Google Scholar]

- Ren W., Ding T., Yang Y., Xing L., Cheng Q., Zhao D., Zhang Z., Li Q., Zhang J., Zheng L., et al. Identifying oxygen activation/oxidation sites for efficient soot combustion over silver catalysts interacted with nanoflower-like hydrotalcite-derived CoAlO metal oxides. ACS Catal. 2019;9:8772–8784. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Carvajal J. Recent advances in magnetic structure determination by neutron powder diffraction. Physica B. 1993;192:55–69. [Google Scholar]

- Sasikala R., Gupta N.M., Kulshreshtha S.K. Temperature-programmed reduction and CO oxidation studies over Ce–Sn mixed oxides. Catal. Lett. 2001;71:69–73. [Google Scholar]

- Sellers-Anton B., Bailon-Garcia E., Cardenas-Arenas A., Davo-Quinonero A., Lozano-Castello D., Bueno-Lopez A. Enhancement of the generation and transfer of active oxygen in Ni/CeO2 catalysts for soot combustion by controlling the Ni-ceria contact and the three-dimensional structure. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020;54:2439–2447. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.9b07682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkataswamy P., Rao K.N., Jampaiah D., Reddy B.M. Nanostructured manganese doped ceria solid solutions for CO oxidation at lower temperatures. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. 2015;162:122–132. [Google Scholar]

- Wang B., Zhang H., Xu W., Li X., Wang W., Zhang L., Li Y., Peng Z., Yang F., Liu Z. Nature of active sites on Cu–CeO2 catalysts activated by high-temperature thermal aging. ACS Catal. 2020;10:12385–12392. [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Luo S., Zhang M., Liu W., Wu X., Liu S. Roles of oxygen vacancy and Ox- in oxidation reactions over CeO2 and Ag/CeO2 nanorod model catalysts. J. Catal. 2018;368:365–378. [Google Scholar]

- Wu X., Liu S., Weng D., Lin F., Ran R. MnOx-CeO2-Al2O3 mixed oxides for soot oxidation: activity and thermal stability. J. Hazard. Mater. 2011;187:283–290. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2011.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu H., Zhang Z., Liu J., Do-Thanh C.L., Chen H., Xu S., Lin Q., Jiao Y., Wang J., Wang Y., et al. Entropy-stabilized single-atom Pd catalysts via high-entropy fluorite oxide supports. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:3908. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-17738-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu L., Liang H.W., Yang Y., Yu S.H. Stability and Reactivity: positive and negative aspects for nanoparticle processing. Chem. Rev. 2018;118:3209–3250. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan D., Chen J., Jia H. Temperature-induced structure reconstruction to prepare a thermally stable single-atom platinum catalyst. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020;59:13562–13567. doi: 10.1002/anie.202004929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X., Li Q., Lu E., Wang Z., Gong X., Yu Z., Guo Y., Wang L., Guo Y., Zhan W., et al. Taming the stability of Pd active phases through a compartmentalizing strategy. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:1611. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-09662-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu M., Luss D., Balakotaiah V. Regeneration modes and peak temperatures in a diesel particulate filter. Chem. Eng. J. 2013;232:541. [Google Scholar]

- Yu M., Luss D., Balakotaiah V. Analysis of flow distribution and heat transfer in a diesel particulate filter. Chem. Eng. J. 2013;226:68. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z., Zhu Y., Asakura H., Zhang B., Zhang J., Zhou M., Han Y., Tanaka T., Wang A., Zhang T., Yan N. Thermally stable single atom Pt/m-Al2O3 for selective hydrogenation and CO oxidation. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:16100. doi: 10.1038/ncomms16100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao M., Deng J., Liu J., Li Y., Liu J., Duan Z., Xiong J., Zhao Z., Wei Y., Song W., Sun Y. Roles of surface-active oxygen species on 3DOM cobalt-based spinel catalysts MxCo3–xO4 (M = Zn and Ni) for NOx -assisted soot oxidation. ACS Catal. 2019;9:7548–7567. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data reported in this paper will be shared by the lead contact upon reasonable request.

This study does not report original code.

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the Lead Contact upon reasonable request.