Abstract

Background

Pain, swelling and joint stiffness are the major problems following arthroscopic ACL reconstruction (ACLR) surgery that restrict early return to sports and athletic activities. The patients often receive prolonged analgesic medications to control the inflammatory response and resume the pre-injury activities. This systematic review aims to evaluate the safety and efficacy of intraarticular (IA) hyaluronic acid (HA) injection following ACLR.

Material and methods

A literature search of electronic databases and a manual search of studies reporting clinical effectiveness of IA HA following ACLR was performed on 1st November 2020. The quality of the methodology and risk of bias was assessed using the Cochrane Collaboration Risk of Bias Tool and Newcastle-Ottawa scale for randomized-controlled trial and prospective cohort studies, respectively.

Results

Of 324 studies retrieved, four studies (3 RCTs and one prospective cohort study) were found to be suitable for inclusion in this review. These studies had a low to moderate risk of bias. There were 182 patients in the HA group and 121 patients in the control group. The demographic characteristics of the patients were similar in all studies. The pooled analysis of studies evaluating pain at different follow up periods (2-week, 4–6 weeks, 8–12 weeks) after ACLR revealed no significant difference between the HA and control groups (p > 0.05). The knee swelling was significantly less in the HA group at two weeks (MD -7.85, 95% CI: [-15.03, −0.68], p = 0.03, I2 = 0%), but no such difference was noted after 4–6 weeks and 8–12 weeks. The functional outcome score was not significantly different between the groups (SMD 0.00, 95% CI: 0.38 to 0.38, p = 0.99, I2 = 0%).

Conclusions

Although the individual study demonstrated a short-term positive response regarding pain control and swelling reduction, the pooled analysis did not find any clinical benefit of IA HA injection following ACLR surgery.

Level of evidence

II.

Keywords: ACL, Arthroscopy, Knee, Hyaluronate, Viscosupplementation, Biologic therapy, Functional outcome, Postoperative pain

1. Introduction

Pain, swelling, and limited joint mobility following arthroscopic anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction (ACLR) surgery impair functional recovery.1,2 The surgical stimuli augment the inflammatory process in the knee joint. The synovial fluid also gets washed out and compromises the joint lubrication. In order to control pain and inflammation, physicians have used nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or pain-inhibiting substances in the form of oral or parenteral medications, perineural catheters, and infusion pumps for early recovery.3, 4, 5 Since the last decade, IA HA has gained popularity because of its viscoelastic properties enabling joint lubrication and shock absorption.6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13 Early viscosupplementation has also added advantages of inhibiting the joint inflammation in various ways; the macromolecular meshwork impedes the movement of neutrophils and other inflammatory cells, inhibits the production of arachidonic acid metabolites, impairs the oxidative stress, and inhibits the matrix metalloproteinase.8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13 Exogenous HA also stimulates endogenous HA production by paracrine effects.8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13 Few animal studies have documented favourable biomechanical and histological effects of HA on bone-tendon healing in ACLR.14,15 In a randomized controlled trial, Huang et al. reported better functional outcomes following multiple intraarticular (IA) HA instillation. At the end of one year, patients receiving HA had superior outcomes as evaluated using the Lysholm scoring system, ambulation speed, range of motion, and muscle peak torque.10 Chau et al. had similar observations, and they reported early resolution of pain and swelling with single IA HA administration.8 However, DiMartino et al. did not observe any improvement in clinical scores following HA administration compared to the control group who received normal saline.9 All these studies have different types and doses of HA with different administration protocol. It seems the role of IA HA following ACLR is still debated; hence, this systematic review was conducted to review studies evaluating the effectiveness of HA on pain, swelling, and functional outcomes. It was hypothesized that patients receiving IA HA following ACLR had better pain relief, lesser swelling and superior functional outcomes compared to the control group.

2. Material and methods

The guideline of Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) was followed to report this systematic review [Fig. 1].16 This systematic review has been registered in PROSPERO (CRD42020218372).

Fig. 1.

PRISMA Flow Diagram showing methods of study recruitment.

2.1. Search strategy

Two authors searched PubMed/Medline, Embase, and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials to retrieve articles related to viscosupplementation in ACL reconstruction. Any articles published until 1st November 2020 on this topic were searched using the following keywords: anterior cruciate ligament, ACL, anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction, ACLR, ligament reconstruction, knee ligament reconstruction, knee arthroscopy, hyaluronate, hyaluronic acid, sodium hyaluronate, viscosupplementation. The search was limited to the human being, but there was no language restriction. The abstract of the retrieved articles was assessed, and the full text of the selected studies was extracted. If the abstract was inadequate to give detailed information, the full text of the article was extracted for further analysis. A manual search of the bibliographic details was also performed to retrieve more articles. The authors discussed to solve any controversy related to study inclusion; however, a third author was consulted in case of disagreement.

2.2. Study eligibility criteria

The following inclusion criteria were proposed for this review: 1. the patients must have undergone arthroscopic ACLR using hamstring graft or BPTB graft; 2. the study must be a randomized controlled trial (RCT) or an observational study; 3. The study must have evaluated the pain scores and functional outcomes after intraarticular hyaluronic acid injection following ACLR; 4. The study must have reported at least 4 weeks of follow-up outcomes. The following studies were excluded: 1. if the patients had received additional steroid or other biologic therapy (platelet-rich plasma, mesenchymal stem cells preparation etc.); 2. If there were associated severe meniscal tear, chondral damage, concomitant other knee ligament injuries or osteoarthritis knee of Kellgren-Lawrence grades II, III, or IV.

2.3. Outcome measures

The primary objective of this review was to assess pain between HA and placebo group in the postoperative period of ACLR. The secondary objective was to evaluate swelling, range of motion (ROM), functional outcomes and adverse event/side effects of the drug.

2.4. Data collection

Two authors extracted the data (author, year of publication, study design, intervention, follow-up, and outcomes) from the studies. The opinion of a third author was sought in case there was any disagreement.

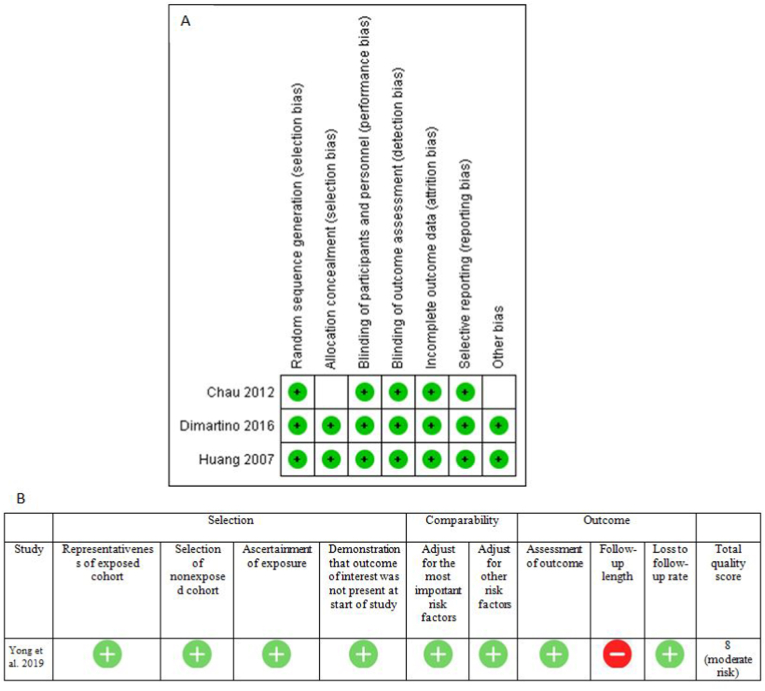

2.5. Methodological quality and risk of bias assessment

Two authors evaluated the methodological quality and risk of bias of the randomized controlled trial using the Cochrane Collaboration Risk of Bias Tool.17 This risk of bias assessment tool has seven components: random sequence generation (selection bias), allocation concealment (selection bias), blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias), blinding of outcome assessment data (detection bias), incomplete outcome data (attrition bias), selective reporting (reporting bias) and other bias.17 Each item is categorized as "high risk," "low risk," or "unclear risk." The quality of the prospective cohort studies was assessed using the Newcastle–Ottawa scale (NOS).18 The NOS uses a star system with a maximum of nine stars to evaluate a study in three domains (8 items): the selection of the study groups, the comparability of the groups, and the ascertainment of the outcomes of interest. Each item was allocated one star for low risk and no star for high risk. Studies that received a score of nine stars were considered as low risk of bias, seven or eight stars as moderate risk, and six or less as high risk of bias. In case of any disagreement between the two authors, a third author was consulted.

2.6. Statistical analysis

The data were pooled and analyzed with Review Manager (RevMan) V.5.3 software.19 The mean difference (MD)/standard mean difference (SMD) and 95% CI were estimated for continuous data. A P-value of ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant. The heterogeneity among the cohort studies was evaluated by Cochrane's Q (χ2 p < 0.10) and quantified by the I2-Higgins test. The I2 value of 25%, 50% and 75% was considered as low, moderate, and high grade of heterogeneity, respectively.20 The random-effects model was applied if the heterogeneity was above 50% (I2 >50%).21

3. Results

A total of 324 studies were retrieved after electronic and manual searches, of which four studies were found to be eligible for review [Fig. 1]. Three studies were randomized controlled trial,8, 9, 10 and one was a prospective cohort study.11 The demographic profiles, inclusion-exclusion criteria, and surgical details have been provided in Table 1. These RCTs have a low risk of bias except an unclear risk of bias in two domains (allocation concealment and other bias) of Chau et al.8 The study by Yong et al. had a moderate risk of bias as assessed using NOS [Fig. 2].11 There were 182 patients in the HA group and 121 patients in the control group. The number of male patients was around three times more than female patients (224 male and 79 females).

Table 1.

Details of the patients, intervention, outcome assessment and follow up.

| Study/year | Study design | Participants | Age/gender (M:F) | Injury to surgery | ACLR | Injection HA/placebo | Outcome assessment | Follow up | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chau 2012 | RCT | HA: 16 Control: 16 |

HA: 27 ± 6, 13/3 Control: 26 ± 7,15/1 |

HA: 18 Control: 16 (months) | Single-bundle reconstruction with a hamstring graft. | HA: 10 ml of sodium 0.5% hyalouronate (Viscoseal), one injection immediately after surgery Control: no injection |

Knee injury osteoarthritis outcome score (KOOS), ROM, Analgesic use, Knee circumference | 1d, 2d, 2wks, 6wks and 12 wks | Knee swelling and function were significantly better in the HA group for initial 2 days. There were no differences in pain, swelling, range of motion and function at 2,6 &12 weeks. Only one patient in the HA group had a limited ROM. No patient developed any adverse reaction. |

| Di Martino 2016 | RCT | HA: 30 Control: 30 |

HA: 30.2 ± 8.3, 25/5 Control: 30.8 ± 10.6, 23/7 |

HA: 8.2 ± 7.4 Control: 13.5 ± 8.5 (months) |

Hamstring tendons sutured together as a double-stranded graft | HA: 24 mg/3 mL (Hymovis) on next day of surgery Control: 3 ml NS | SF-36, International Knee Documentation Committee (IKDC), VAS for pain, VAS for general health status, and Tegner score, ROM |

15d, 30d, 60d, and 180d and 12 months | There were no differences in clinical scores between the groups. The HA group showed a better reduction in knee swelling at 60 days and better range of motion at 30 days in the postoperative period. No severe adverse events were documented after early viscosupplementation. |

| Huang 2007 | RCT | HA: 90 Control: 30 |

27.0 ± 8.4, 91:29 | 3 weeks to 6 months | BPTB graft | HA (16 mg, 6,000,000 da MW in 2 mL of buffered physiological NS (Synvisc): Gr I:at 4, 5 & 6 wks; Gr II: at 8, 9, 10 wks, Gr III: at 12, 13, 14 wks Control: NS at 4 wks |

Lysholm knee scoring scale (LKSS), ambulation speed (AS), ROM and muscle peak torque (MPT) | 4wks, 8wks, 12wks, 16 wks, 1 year | HA group demonstrated better function and muscle peak torque for initial two months of intraarticular HA instillation. However the persistent beneficial effect of HA at one year follow up was seen only in patients who received HA at 8 weeks or afterthat. |

| Yong 2019 | Prospective study | HA: 46 Control: 45 |

HA: 39.9 ± 6.2, 29:17 Control: 39.3± 6.0, 28:17 |

HA: 6.5 ± 1.5 d Control: 6.3 ± 1.7 d |

Autologous semi-tendon tendon and graciliis tendon, Rigid-fix | 25 mg/time, 1 week/time, first dose immeidtaely after surgery, continuous injection for 10 weeks (Shanghai Jingfeng Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., approval number: Sinopharm quasi H20000643) | Pain (VAS), Lysholm score, synovial fluid analysis (IL-1β, TNF-α, MDA, glutathione peroxide Enzyme), serum markers (serum indicators (osteocalcin, type I procollagen carboxy terminal peptide and bone alkaline Phosphatase) |

10 wks | Pain, function and inflammatory markers showed significant improvement in HA group at 10 weeks. |

D:days, wks: weeks, HA: hyaluronic acid, AS: ambulation speed, MPT: Muscle peak torque, ROM: range of motion.

Fig. 2.

Risk of bias assessment using Cochrane Collaboration Risk of Bias Tool (A) and Newcastle–Ottawa scale (B).

3.1. Characteristics of the patients

The patients in both HA and control groups were homogenous with regards to age, gender, BMI, and associated injury in the operated knee [Table 1]. The mean age was 31.42 ± 9.54 years. There were more male patients than female patients in all studies. None of the studies had recruited obese patients. Yong et al. recruited acute ACL injury (<2 weeks), whereas remaining all studies enrolled the chronic/subacute ACL tear (>3 weeks to years).8, 9, 10, 11

The study by Huang et al.10 completely excluded associated meniscal and chondral injuries, whereas Yong et al.11 did not mention it. The remaining two studies included associated meniscal surgery (partial meniscectomy). Chau et al.8 operated 17 patients (8 in HA and 9 in control), and DiMartino et al.9 operated 24 patients (11 in HA and 13 in control) with partial meniscectomy.

3.2. Types, doses, and protocol of HA administration

Two studies (Huang et al. and Young et al.) used multiple doses, and the other two studies (Chau et al. and DiMartino et al.) used one dose of HA following ACLR. Three studies used the injection immediately after surgery or on the next day of surgery; only one study used it after one month (Huang et al.). Chau et al. used Viscoseal, an intermediate molecular weight HA; DiMartino used Hymnovis, a highly viscoelastic, non-cross-linked low molecular weight HA (500–730 kDa), and Huang et al. used high molecular weight HA (Synvisc).

3.3. Rehabilitation program

The standard rehabilitation protocol was used in three studies (Chau et al., DiMartino et al., and Young et al.), whereas Huang et al. used accelerated ACL rehabilitation protocol. None of the studies used intraarticular analgesia or local anaesthesia. The NSAID was used in three studies for a limited time (5–10 days) for pain control,8, 9, 10 whereas the detail of analgesia was not mentioned in the study of Yong et al.11

3.4. Pain, swelling, ROM functional outcomes [Table 2]

Table 2.

Clinical outcome in HA and control group as evaluated at different time points.

| Study | Outcome | Group | Baseline | 2 wks | 4–6 wks | 8–12 wks | 4 m | 12 m |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chau 2012 | Pain | HA | 77.8 ± 16.5∗ | 61.5 ± 21.1 | 72.9 ± 15.0 | 82.6 ± 15.9 | ||

| Control | 88.3 ± 7.5 | 59.1 ± 14.6 | 72.2 ± 15.2 | 81.2 ± 10.1 | ||||

| Change In Knee Circumference(cms) | HA | 1.00 ± 1.6 | 0.64 ± 1.82 | 0.25 ± 1.4 | ||||

| Control | 1.85 ± 1.1 | 1.46 ± 1.9 | 0.5 ± 1.8 | |||||

| Full Range of Movement (No of Patients) | HA | 4 | 12 | 15 | ||||

| Control | 3 | 14 | 16 | |||||

| Di Martino 2016 | VAS For Pain | HA | 1.6 ± 2.2 | 1.8 ± 1.7 | 1.3 ± 1.8 | 0.7 ± 1.5 | 0.1 ± 0.5 | |

| Control | 2.1 ± 2.3 | 2.0 ± 1.7 | 0.9 ± 1.4 | 0.6 ± 1.4 | 0.2 ± 0.5 | |||

| IKDC Subjective Score | HA | 65.8 ± 16.2 | 90.8 ± 9.1 | |||||

| Control | 60.0 ± 17.3 | 91.5 ± 8.8 | ||||||

| Tegner Score | HA | 3.3 ± 1.2 | 6.0 ± 1.9 | |||||

| Control | 3.2 ± 1.3 | 6.1 ± 1.8 | ||||||

| Huang 2007 | Lysholm Knee Score | Group-I HA at 4 weeks |

33 ± 11 (30) | 8 wks: 45 ± 13 (30) a 12 wks: 53 ± 13 (29)a |

62 ± 14 (27) | 66 ± 12 (23) | ||

| Group-II HA at 8 weeks |

35 ± 13 (30) | 8 wks: 39 ± 10 (30) 12 wks: 61 ± 12 (30) a | 82 ± 13 (29) a | 86 ± 15 (25) a | ||||

| Group-III HA at 12 weeks |

34 ± 12 (30) | 8 wks: 38 ± 14 (30) 8 wks: 46 ± 13 (29) |

70 ± 14 (27) a | 72 ± 12 (23)∗ | ||||

| Group-IV (control) | 35 ± 14 (30) | 8 wks:39 ± 15 (30) 12 wks: 45 ± 16 (29) |

60 ± 13 (27) | 65 ± 14 (24) | ||||

| Yong 2019 | VAS Score | HA | 6.2 ± 1.2 | 1.8 ± 0.8a | ||||

| Control | 6.1 ± 1.4 | 3.5 ± 1.5 | ||||||

| Lysholm Score | HA | 45.4 ± 9.1 | 74.8 ± 11.3a | |||||

| Control | 45.2 ± 9 | 63.4 ± 10.5 |

clinically significant intergroup difference.

Pooled analysis of studies evaluating pain at different follow up periods (2-week, 4–6 weeks, 8–12 weeks) after ACLR revealed no significant difference between the HA and control groups (p > 0.05)(Fig. 3). The analysis showed significant heterogeneity among the studies for pain scores at 8–12 weeks (SMD -0.43, 95%CI: [-1.48, 0.62], p = 0.42, I2 = 91%). However, the heterogeneity could be reduced to 0% after excluding the data of Yong et al. (SMD 0.08, 95% CI: [-0.33, 0.49], p = 0.70, I2 = 0%)(Fig. 3). The knee swelling that was evaluated by measuring the knee circumference was significantly less in the HA group at two weeks (MD -7.85, 95% CI: [-15.03, −0.68], p = 0.03, I2 = 0%), but no such difference was noted after 4–6 weeks and 8–12 weeks (Fig. 4). The pooled analysis of the studies did not find a significant difference in the functional outcome scores between the HA and control groups (Fig. 5).

Fig. 3.

Forest plot diagram showing pain score at different times.

Fig. 4.

Forest plot diagram showing change in knee circumference at different times.

Fig. 5.

Forest plot diagram showing functional outcome following ACLR.

Chau et al. reported a significant reduction in pain and knee swelling for the initial two days following ACLR in the HA group. They reported a better functional outcome (KOOS) for this period. However, the trend of superior clinical outcomes in the HA group was not seen after 2, 6, and 12 weeks of follow up.8 The study by DiMartino et al. reported significant improvements in pain and all functional scores (IKDC, Tegner score) in both the groups (HA and control) after 6 and 12 months of ACLR, but the intergroup difference was not significant. The two objective methods of assessment, such as knee circumference difference at 2 months and ROM at one month was significantly better in the HA group.9

Huang et al. divided the HA treatment into three groups; the patients in each group received three injections at a one-week interval. The first group received the first injection after 4 weeks of ACLR, while the second and third groups received the first dose after 8 weeks and 12 weeks, respectively. The control group received three doses of IA normal saline commencing at 4 weeks. The authors reported a significant improvement in the Lysholm Knee Scoring Scale, ROM, ambulation speed, and isokinetic peak torque of knee flexion and extension in the HA group for a short period following the IA HA (at 1 and 2 months of injection). A persistent better outcome was observed in the HA group at one year, specifically in patients who received the HA injection at 8 weeks or later.10

Yong et al. reported better pain relief and functional scores at 10 weeks in patients who received IA HA than the control group. Around 98% of patients in the HA group and 82% of patients in the control group had a Lysholm score of >25% following ACLR. The authors reported a significantly lower level of synovial inflammatory markers in the HA group, but serum levels of bone and cartilage formation markers were elevated.11

3.5. Complications, side effects/adverse events of HA

There were no complications or side effects related to HA treatment in any of the studies.8, 9, 10, 11 Only one patient in the study of Chau et al. had a restriction of knee motion, but the reason was not mentioned.8

4. Discussion

Although few studies demonstrated a short-term benefit, the pooled analysis of the studies with regards to the postoperative pain scores, swelling and functional outcomes did not find any benefit of IA HA injection following ACLR. However, there was no report of any adverse effect following intraarticular administration of this drug.

Multiple factors can influence postoperative pain, inflammation, and functional recovery in ACLR.22 The demographic parameters, delay in surgery and associate menisco-chondral lesions are the major determinants.22,23 Accordingly, these parameters were discussed for all the studies. The age, sex and BMI of the patients in the included studies were similar and hence, unlikely to influence the outcomes. Yong et al. recruited acute ACL tear patients and reported a higher baseline pain scores (VAS 6.1 in control and 6.2 in HA) than DiMartino et al. (VAS 1.6 in HA and 2.1 in control), who included only chronic ACL tear.9,11 This trend of higher pain scores was even noted following ACLR surgery in acute tear. Yong et al. reported a mean VAS of 1.8 and 3.5 in the HA and control groups after 10 weeks.11 DiMartino et al. reported a lesser pain in both the groups after 8 weeks of surgery (VAS of 0.7 in HA and 0.6 in control, respectively).9 The included studies in this review were very particular about the patient selection with regards to associate menisco-chondral lesions; all such severe associate injuries were excluded.

The rheological property, resorption kinetics, and clinical effectiveness of HA are affected by the chemical modifications.24, 25, 26 The molecular weight of HA modulates the macrophage activation system.26 A low molecular weight HA (≤5 kDa) promotes the production of inflammatory mediators, whereas high molecular weight HA (>800kDA) inhibits the production of pro-inflammatory mediators. Two studies in this review used a single dose of non-cross-linked, highly viscous HA molecule that had longer intraarticular durability to minimize cost and infection risk.8,9 Contrary to it, multiple doses were used in other studies to provide a long-lasting effect.10,11 The study by DiMartino et al. did not observe a significant clinical improvement with a single dose and stressed on multiple HA doses.9 The rationale of IA HA instillation immediately following ACLR was based on its anti-inflammatory property and lubricating effect, but Huang et al. injected HA at the end of 4 weeks.10 They hypothesized that the early inflammatory response between 3 and 8 weeks of ACLR might be helpful for early vascularisation of the ACL graft and its healing.10 Therefore IA HA at four weeks failed to show the beneficial clinical effect in their study. They believed that HA administration at eight weeks is more suitable as the graft proliferation and cells migration occurs during that time. Few researchers believe that intraoperative use of HA could be affected by dilution because of the surgical bleed and residual normal saline retained inside the joint following knee arthroscopy.9 Injection on the first or second postoperative day following drain removal overcomes this problem and becomes more efficacious.10 The direct evidence of the anti-inflammatory property of IA HA was revealed by Yong et al., who observed a significant decrease in the synovial inflammatory markers.11

Despite heterogeneity in patient selection, HA formulation, and dosing schedule in the included studies, there were some improvement in the clinical parameters after IA HA injection. Chau et al. reported significant improvement in pain, swelling and function in the HA group for initial 2 days, but no such differences were observed afterthat. DiMartino et al. reported no differences in clinical scores between HA group and placebo group, however a better range of motion and swelling reduction was observed specifically at one month and two months follow up. Similarly, Yong et al. also reported better pain control and function at 10 weeks. All the above studies injected HA immediately after surgery or within two days of surgery. However, the study by Huang et al. injected HA after 4 weeks. They demonstrated significant improvement in function and muscle peak torque after one month and two months of IA HA injection. The beneficial effect of HA persisted at one year only in those patients who received the injection at 8 weeks or after that. All the reviewed studies documented an improvement in pain, swelling, and/or ROM either immediately following the HA injection or within 1–2 months follow up.8, 9, 10, 11 However, the improvement in pain, function and other clinical parameters at specific point of time is not uniform and hence, it is difficult to assess the benefit of HA following ACLR. The pooled analysis of the studies in this review did not find any difference between the HA and control groups with regards to pain scores, functional scores and knee swelling. It seems the IA HA in isolation is inadequate to negate the inflammatory response of the knee joint following ACLR.

The limitations of this review are a small sample size, limited studies, and non-uniform treatment. The number of doses, types of HA, and administration timing were different in the included studies. Limb alignment and the stability of the knee joint following ACLR have a significant impact on the outcomes; however, these factors were not analyzed in these studies. Also, the patient's perception or behaviour towards pain and rehabilitation has an essential role in the outcomes. The clinical recovery of ACLR is nearly always complete over a medium-term and long term period.27 Hence, the rationale of early viscosupplementation is to facilitate early recovery so that sports activity can be resumed promptly; accordingly, a follow-up period of one year in the included studies was adequate to look for the effectiveness of IA HA. However, none of the studies evaluated "return to sports activity or work" in the included studies.

Although the individual study demonstrated a short term benefit, this systematic review did not find any clinical benefit of IA HA injection following ACLR surgery. Small studies with variable injection protocol limit this interpretation. The researchers need to explore this drug further with better-designed trials to evaluate its efficacy in the postoperative period of ACLR.

Funding

None.

Ethical consideration

This systematic review has been registered in PROSPERO (Regd no.: CRD42020218372).

Declaration of competing interest

The authors of this manuscript declare that they have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Moller E., Weidenhielm L., Werner S. Outcome and knee-related quality of life after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a long-term follow-up. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2009;17:786–794. doi: 10.1007/s00167-009-0788-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Strum G.M., Friedman M.J., Fox J.M., et al. Acute anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Analysis of complications. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1990;253:184–189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Macdonald S.A., Heard S.M., Hiemstra L.A., et al. A comparison of pain scores and medication use in patients undergoing single-bundle or double-bundle anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Can J Surg. 2014;57(3):E98–E104. doi: 10.1503/cjs.018612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Williams B.A., Bottegal M.T., Kentor M.L., et al. Rebound pain scores as a function of femoral nerve block duration after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: retrospective analysis of a prospective, randomized clinical trial. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2007;32(3):186–192. doi: 10.1016/j.rapm.2006.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Williams B.A., Kentor M.L., Irrgang J.J., et al. Nausea, vomiting, sleep, and restfulness upon discharge home after outpatient anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with regional anesthesia and multimodal analgesia/antiemesis. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2007;32(3):193–202. doi: 10.1016/j.rapm.2006.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hempfling H. Intra-articular hyaluronic acid after knee arthroscopy: a two-year study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2007;15(5):537–546. doi: 10.1007/s00167-006-0260-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bellamy N., Campbell J., Robinson V., et al. Viscosupplementation for the treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;2:CD005321. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005321.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chau J.Y., Chan W.L., Woo S.B., et al. Hyaluronic acid instillation following arthroscopic anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a double-blinded, randomized controlled study. J Orthop Surg. 2012;20(2):162–165. doi: 10.1177/230949901202000205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Di Martino A., Tentoni F., Di Matteo B., et al. Early viscosupplementation after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44(10):2572–2578. doi: 10.1177/0363546516654909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang M.H., Yang R.C., Chou P.H. Preliminary effects of hyaluronic acid on early rehabilitation of patients with isolated anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Clin J Sport Med. 2007;17(4):242–250. doi: 10.1097/JSM.0b013e31812570fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yong L., Shuming G., Guangfei L., et al. Clinical value of knee arthroscopy combined with sodium hyaluronate in early anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. J Clin Surg. 2019;27(4):309–312. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Waddell D.D., Bert J.M. The use of hyaluronan after arthroscopic surgery of the knee. Arthroscopy. 2010;26:105–111. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2009.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Westrich G., Schaefer S., Walcott-Sapp S., et al. Randomized prospective evaluation of adjuvant hyaluronic acid therapy administered after knee arthroscopy. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ) 2009;38:612–616. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yucel I., Karaca E., Ozturan K., et al. Biomechanical and histological effects of intra-articular hyaluronic acid on anterior cruciate ligament in rats. Clin Biomech. 2009;24:571–576. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2009.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yagishita K., Sekiya I., Sakaguchi Y., et al. The effect of hyaluronan on tendon healing in rabbits. Arthroscopy. 2005;21:1330–1336. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2005.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hutton B., Wolfe D., Moher D., et al. Reporting guidance considerations from a statistical perspective: overview of tools to enhance the rigour of reporting of randomized trials and systematic reviews. Evid Base Ment Health. 2017;20:46–52. doi: 10.1136/eb-2017-102666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Higgins J., Green S.E. In: Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0, 2011. The Cochrane Collaboration, editor. 2011. www.cochrane-handbook.org [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wells G., Shea B., O'Connell D., et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomized studies in metaanalyses. http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp

- 19.Review Manager (RevMan) [Computer Program] Version 5.3 (2014) Copenhagen : The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration. Accessed on 19 December 2020.

- 20.Zlowodzki M., Poolman R.W., Kerkhoffs G.M., Tornetta P., 3rd, Bhandari M. International Evidence-Based Orthopedic Surgery Working Group. How to interpret a metaanalysis and judge its value as a guide for clinical practice. Acta Orthop. 2007;78(5):598–609. doi: 10.1080/17453670710014284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schmidt F.L., Oh I.S., Hayes T.L. Fixed- versus random-effects models in metaanalysis: model properties and an empirical comparison of differences in results. Br J Math Stat Psychol. 2009;62:97–128. doi: 10.1348/000711007X255327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rosso F., Bonasia D.E., Cottino U., et al. Factors affecting subjective and objective outcomes and return to play in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a retrospective cohort study. Joints. 2018;6(1):23–32. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1636931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Piasecki D.P., Spindler K.P., Warren T.A., et al. Intraarticular injuries associated with anterior cruciate ligament tear: findings at ligament reconstruction in high school and recreational athletes. An analysis of sex-based differences. Am J Sports Med. 2003;31(4):601–605. doi: 10.1177/03635465030310042101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Altman R.D., Manjoo A., Fierlinger A., et al. The mechanism of action for hyaluronic acid treatment in the osteoarthritic knee: a systematic review. BMC Muscoskel Disord. 2015;16(1):321. doi: 10.1186/s12891-015-0775-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Braithwaite G.J., Daley M.J., Toledo-Velasquez D. Rheological and molecular weight comparisons of approved hyaluronic acid products: preliminary standards for establishing class III medical device equivalence. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed. 2015;27(3):235–246. doi: 10.1080/09205063.2015.1119035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rayahin J.E., Buhrman J.S., Zhang Y., Koh T.J., Gemeinhart R.A. High and low molecular weight hyaluronic acid differentially influence macrophage activation. ACS Biomater Sci Eng. 2015;1(7):481–493. doi: 10.1021/acsbiomaterials.5b00181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marcacci M., Zaffagnini S., Giordano G., et al. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction associated with extra-articular tenodesis: a prospective clinical and radiographic evaluation with 10- to 13-year follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(4):707–714. doi: 10.1177/0363546508328114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]