Abstract

Many intellectual disability disorders are due to copy number variations, and to date there have been no treatment options tested for this class of diseases. MECP2 duplication syndrome (MDS) is one of the most common genomic rearrangements in males and results from duplications spanning the methyl-CpG binding protein 2 (MECP2) gene locus. We previously showed that antisense oligonucleotide (ASO) therapy can reduce MeCP2 protein amount in an MDS mouse model and reverse its disease features. This MDS mouse model, however, carried one transgenic human allele and one mouse allele, with the latter being protected from human-specific MECP2-ASO targeting. Because MeCP2 is a dosage-sensitive protein, the ASO must be titrated such that the amount of MeCP2 is not reduced too far, which would cause Rett syndrome. Therefore, we generated a “MECP2 humanized” MDS model that carries two human MECP2 alleles and no mouse endogenous allele. Intracerebroventricular injection of the MECP2-ASO efficiently downregulated MeCP2 expression throughout the brain in these mice. Moreover, MECP2-ASO mitigated several behavioral deficits and restored expression of selected MeCP2-regulated genes in a dose-dependent manner without any toxicity. Central nervous system administration of MECP2-ASO is therefore well tolerated, beneficial, and provides a translatable approach that could be feasible for treating MDS.

One Sentence Summary:

This study demonstrates that antisense oligonucleotides (ASO) are efficacious and safe in a humanized mouse model of MECP2 duplication syndrome.

Introduction

Methyl-CpG binding protein 2 (MeCP2), an epigenetic regulator that is crucial for normal brain function (1), is a dosage-sensitive protein involved in two devastating childhood disorders (2). Loss-of-function mutations in MECP2 cause Rett syndrome (RTT) (OMIM 312750), while duplication of the region on chromosome Xq28 spanning MECP2 (3–6) causes MECP2 duplication syndrome (MDS) (OMIM 300260). RTT affects ~1 in 10,000 females and is characterized by 6–18 months of normal development followed by a period of regression that includes deceleration of head growth, loss of acquired motor, language, and social skills, and the development of hand stereotypies, breathing difficulties, seizures, autonomic dysfunction, and anxiety (7–9). MDS is one of the most common sub-telomeric genomic rearrangements in males, accounting for ~1% of X-linked cases of intellectual disability (10). MDS manifests almost exclusively in males and is characterized by infantile hypotonia, intellectual disability, anxiety, motor dysfunction, epilepsy, recurrent respiratory tract infections and premature death (11–13); triplications cause an even more severe phenotype (5, 14).

We recently demonstrated that the MDS-like phenotype can be reversed in adult symptomatic mice when MeCP2 protein concentration is normalized either genetically or using MECP2-specific antisense oligonucleotides (MECP2-ASO) that are administered gradually in the brain (15). ASOs are small modified nucleic acids that can selectively hybridize with the transcripts from a target gene and silence it. When the ASO-RNA heteroduplex is formed, the endogenous nuclease, RNase H1, recognizes it and cleaves the targeted transcript (16, 17). ASO treatment has many advantages for neurological disorders, including high target specificity, limited toxicity, extended half-life and precise dosing. To date, ASOs have reversed the disease phenotype in several mouse models, including those for Spinal Muscular Atrophy (SMA) (18, 19), Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) (20, 21), Myotonic Dystrophy Type 1 (DM1) (22), Huntington Disease (23, 24), Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) (25), Angelman syndrome (26), and spinocerebellar ataxia types 1 (SCA1) and 2 (SCA2) (27, 28). More importantly, ASOs have proven safe in recent clinical trials in ALS patients (29), and an ASO-based therapy for infants with SMA (Nusinersen) has recently been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (30).

ASOs seem an excellent choice of approach for MDS, but for one challenge: a MECP2-ASO would target both MECP2 alleles and knocking down the amount of MeCP2 below wild-type could cause RTT symptomatology. Therefore, in preparation for clinical studies aimed to test MECP2-ASOs as a potential therapy for MDS, we need to ensure that the ASO dosage can be reliably titrated. To this end, we generated and validated a “humanized” mouse model of MDS that has two human MECP2 alleles and no mouse allele. Then, we used our humanized MDS mouse model to examine the ASO distribution in the brain following an acute injection (as would be the case in humans). We assessed the pharmacodynamics of ASO-mediated MeCP2 downregulation and evaluated the molecular and behavioral response to determine if the acute ASO therapy can rescue features of the MDS mice in a dose-dependent manner without secondary toxicity.

Results

Generation and characterization of a “MECP2 humanized” mouse model for MECP2 duplication syndrome

To generate a “MECP2 humanized” mouse model of MDS, we used two human MECP2 transgenic mouse lines as breeders: (1) Mecp2-/y; MECP2-TG1 (C57BL/6), which carries a copy of human MECP2 allele on a mouse Mecp2 null background, and (2) Mecp2−/−; MECP2-GFP (FVB), which carries a copy of human MECP2 allele fused in its C-terminus to GFP, on a mouse Mecp2 null background. By crossing these two lines, we generated F1 hybrid mice of 3 different genotypes: two single human allele genotypes—Mecp2 -/y; MECP2-TG1 (hMECP2) and Mecp2 -/y; MECP2-GFP (hMECP2-GFP)—and one double human allele genotype (Mecp2 -/y; MECP2-TG1; MECP2-GFP (hDup)) (Fig. 1A). We performed quantitative RT-PCR using RNA from the adult mouse cortex (Fig. 1B) and found that the human MECP2 mRNA transcript in hMECP2-GFP animals is expressed at a similar amount as endogenous mouse Mecp2 in naïve wildtype (WT) mice, but it is higher in hMECP2 animals (intermediate between naïve WT and hDup). Similar results were found using primers specific for MECP2-e1 and MECP2-e2 isoforms (fig. S1A). SDS-PAGE followed by Western blot shows that both MeCP2 and MeCP2-GFP can be detected in hDup mice (Fig. 1C, fig. S1B). The MeCP2-GFP appears to give lower signal, most likely because of inefficient antibody detection of C-terminally tagged MeCP2, as previously reported (31, 32). Importantly, this MeCP2-GFP allele functions as a wild-type allele and shows normal survival on a null background (33). Fluorescent immunostaining confirmed that hDup mice express both MECP2 alleles across different brain regions, and both alleles co-localize with heterochromatin-dense foci marked by DAPI staining (Fig. 1D-F).

Fig. 1. Generation and characterization of a humanized MECP2 duplication mouse model.

(A) Breeding scheme to generate humanized MECP2 duplication mice. Breeders: hMECP2 - mice with a transgenic human MECP2 allele, and null for the mouse endogenous Mecp2 (C57Bl/6 background). hMECP2-GFP - mice with a transgenic human MECP2 allele fused in the C-terminus to GFP, and null for the mouse endogenous Mecp2 (FVB/N background). Progeny: hDup – mice with both transgenic human MECP2 alleles and null for the mouse endogenous Mecp2 (C57Bl/6 x FVB/N F1 hybrid background). (B) RT-qPCR with common primers for mouse and human MECP2 mRNA shows expression in the cortex. Naïve WT mice have the same C57Bl/6 x FVB/N F1 hybrid background. (n=5). (C) Western blot using specific anti-MeCP2 or anti-GFP antibodies in cortical samples. (D) Immunostaining on hippocampal slices of the two single-human MECP2 allele genotypes. The anti-MeCP2 antibody cannot detect the hMECP2 allele when fused to GFP (hMECP2-GFP). Scale bar=100µm. (E) Immunostaining on hDup mice brain slices shows similar expression and localization of the two different human alleles across different brain regions. Hipp: hippocampus, Cb: cerebellum, CTX: cortex, Hypo: hypothalamus, ChPlx: choroid plexus. Scale bar=100µm. (F) High magnification shows both human MeCP2 alleles co-localize with heterochromatin-dense foci in hDup mice. Scale bar=10µm. (G) Elevated Plus Maze measures the anxiety-like behavior in hDup mice. n=23 for hMECP2-GFP and n=18 for hDup. (H) Open Field Assay tests the activity of the 8-week-old hDup mice. n=23 for hMECP2-GFP and n=18 for hDup. (I) Accelerated Rotarod assay shows the motor behavior in 8-week-old hDup mice. n=22 for hMECP2-GFP and n=16 for hDup. D1T1, day 1/trial 1. All data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by Fisher’s LSD post hoc test, except for the rotarod test that was analyzed by two-way ANOVA with repeated measures. Data are presented as mean ± s.e.m. *P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001.

To further validate our new humanized mouse model of MDS (hDup), we phenotyped a new cohort of male hDup mice using a battery of behavioral tests and compared their phenotypes to those of male hMECP2-GFP mice. Each of the two single-allele humanized mice showed similar behavioral profiles as naïve WT mice (fig. S1C). We chose hMECP2-GFP mice as the control group for further behavioral studies because their MECP2 RNA expression was similar to that in naïve WT mice (Fig. 1B). Compared to 8-week-old hMECP2-GFP mice, age-matched hDup mice displayed increased anxiety (Fig. 1G), normal locomotor activity in the open field test with a trend towards decreased exploratory behavior as measured by rearing episodes (Fig. 1H), increased latency to fall on the accelerated rotarod (Fig. 1I) and increased brain weight (fig. S1D). Social deficits were not detected in hDup mice using the three-chamber and partition tests (fig. S1E, F). Also, at this age, we did not see abnormalities in the electroencephalographic (EEG) recordings of hDup mice (fig. S1G), an age-related phenotype that we previously reported in 9-month-old MECP2-Tg1 of pure FVB background mice (15). Altogether, these abnormalities recapitulate many of the features of established MDS mouse models and MDS in human patients.

Distribution of ASO and effectiveness of MECP2 knockdown in the CNS

We treated 8-week-old mice with a bolus injection of MECP2-ASO stereotaxically targeted to the right lateral ventricle of the brain (Fig. 2A). Two weeks later we stained brain sagittal sections with an ASO-specific antibody. We chose the bolus-injection strategy over the infusion used in our previous study, as bolus injection is the preferred administration protocol in the clinic (31,32). Both control-ASO and MECP2-ASO were widely distributed across the mouse brain (Fig. 2B). To measure the effectiveness of a single dose of 250µg MECP2-ASO, we micro-dissected seven brain regions for analysis of MECP2 expression two weeks after intracerebroventricular (icv) administration. MECP2 mRNA was significantly knocked down in seven brain regions (P<0.0001) (Fig. 2C), and the amount of MeCP2 protein was significantly lowered everywhere (P<0.05) except the cerebellum (Fig. 2D). This indicates that the ASOs are widely distributed across the brain and can effectively knock down MeCP2 protein concentration.

Fig. 2. Widespread distribution of ASO and MeCP2 knock-down in the brain after acute bolus ASO injection.

(A) A single dose of 250µg MECP2-ASO was injected stereotaxically in the right lateral ventricle of 8 to 9-week-old hDup mice. Mouse brain tissue was dissected two weeks after injection. (B) Immunostaining using a specific antibody against the ASO backbone shows the distribution of both control-ASO and MECP2-ASO in the brain. (C) RT-qPCR shows MECP2 mRNA expression in seven brain regions two weeks after a single 250µg dose of MECP2-ASO. Hipp: hippocampus, Ob: Olfactory bulb, Bs: brainstem, Hypo: hypothalamus, Cb: cerebellum, Amy: Amygdala, Str: Striatum, Ctx: Cortex (n=5–6). (D) Quantification of western blot assay shows MeCP2 protein concentration in all brain regions except the cerebellum. Hipp: hippocampus, Ob: Olfactory bulb, Bs: brainstem, Hypo: hypothalamus, Cb: cerebellum, Amy: Amygdala; Str: Striatum; Ctx: Cortex (n=4–5). All data were analyzed by two-tailed t-test. Data are presented as mean ± s.e.m. *P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001.

ASO dose-dependent knockdown of MeCP2 in the CNS

We next performed a dose-response study to determine if we could titrate MeCP2 knockdown. Mice were treated with a single bolus injection of MECP2-ASO or control-ASO in the right lateral ventricle of the brain. Two weeks later, we analyzed MECP2 mRNA expression (Fig. 3A) and MeCP2 protein amount (Fig. 3B,C) in the cortex by RT-qPCR and Western blot, respectively, and found dose-dependent knock-down with increasing amounts of ASO. The highest dose, 500 µg, reduced MECP2 mRNA slightly below normal expression.

Fig. 3. Dose optimization of MECP2-ASO.

(A) RT-qPCR quantification shows MECP2 mRNA expression after MECP2-ASO treatment (cortex, n=5–6). (B) Western blot of MeCP2 protein expression at different ASO doses. (C) Quantification of western blot shows MeCP2 protein amount after the injection of 250µg and 500µg doses (n=5). (D) RT-qPCR shows IFN-γ mRNA expression in blood following acute intracerebral ASO injection (n=5). All data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by Fisher’s LSD post hoc test. Data are presented as mean ± s.e.m. *P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001. hMECP2-GFP; ctrl - hMECP2-GFP mice injected with control-ASO. hDup; ctrl - hDup mice injected with control-ASO. hDup; 150µg - hDup mice injected with 150µg MECP2-ASO. hDup; 250µg - hDup mice injected with 250µg MECP2-ASO. hDup; 500µg - hDup mice injected with 500µg MECP2-ASO.

Finally, we measured interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) mRNA in the blood, which has been reported to be reduced in both MECP2 transgenic mice and human patients (34). We found IFN-γ mRNA to be reduced in hDup mice and restored after ASO treatment (Fig. 3D).

Pharmacodynamics of MECP2-ASO following intracerebroventricular administration

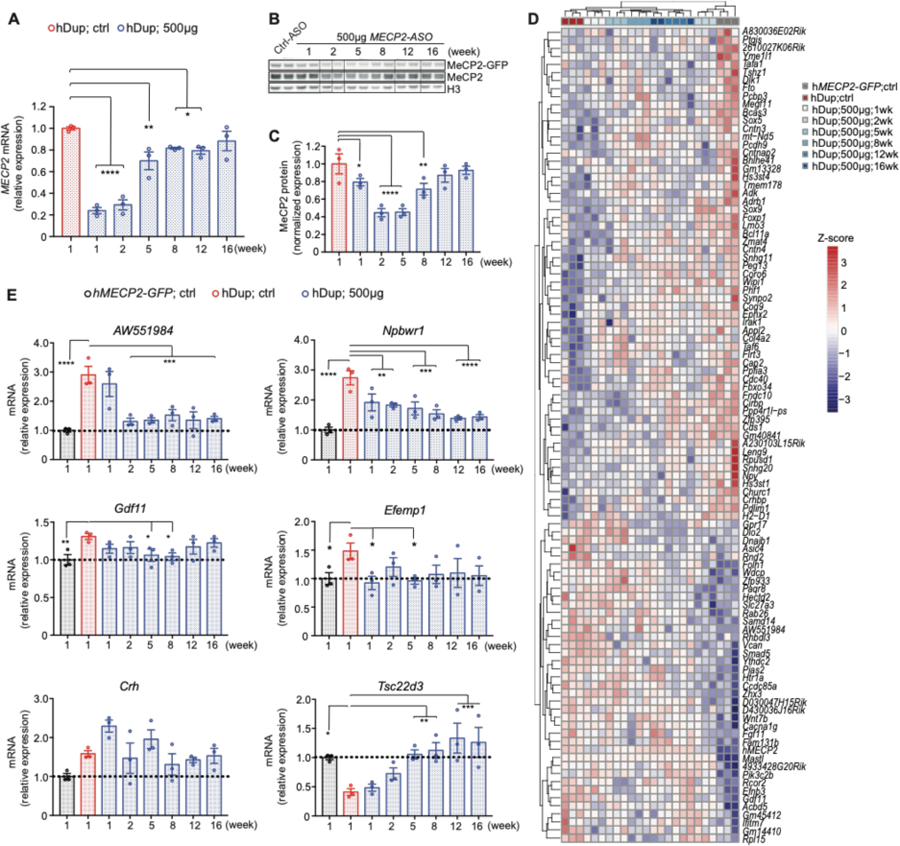

To better understand the dynamics of MeCP2 knockdown after a single-bolus intracerebral injection of ASO, we performed pharmacodynamic (PD) experiments using both 250µg and 500µg MECP2-ASO doses over a period of 16 weeks. 8 to 9-week-old mice were stereotaxically injected with MECP2-ASO in the right lateral ventricle of the brain and MECP2 expression was analyzed at different time points by RT-qPCR and Western Blot (fig. S2A-B, Fig. 4). MECP2 mRNA was knocked down within one week after treatment and started to return back to pre-treatment amount after five weeks. In contrast, MeCP2 protein concentration reached a nadir at two weeks after injection and started to return to pretreatment amount at eight weeks; there is a clear temporal difference in mRNA and protein expression response to the ASO treatment (Fig. 4A-C), with the protein knockdown being both later and milder than the mRNA knockdown. To verify this result, we performed a pharmacodynamic experiment on mice bearing a single human MECP2 allele (fig. S2C-D), which showed a similar trend.

Fig. 4. Pharmacodynamics of MECP2-ASO treatment.

(A) Pharmacodynamics of MECP2 mRNA after 500µg MECP2-ASO treatment, by RT-qPCR (cortex, n=3). (B) Western blot shows the MeCP2 response to 500µg MECP2-ASO at different time points after treatment (n=3). (C) Pharmacodynamics of MeCP2 protein after 500µg MECP2-ASO treatment, by densitometric analysis of western blot in (B). (cortex, n=3). (D) RNA-seq shows gene expression profile at different time points after 500µg MECP2-ASO treatment. (cortex, n=3) (E) RT-qPCR shows pharmacodynamics of selected MECP2-regulated genes (n=3) in response to MECP2-ASO treatment. All data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by Fisher’s LSD post hoc test. Data are presented as mean ± s.e.m. *P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001.

Dysregulation of MeCP2 protein amount alters the expression of many genes (35). To analyze the response of MECP2-regulated genes to the ASO treatment, we performed RNA-sequencing at multiple timepoints on hippocampal tissue following ASO treatment (Fig. 4D). Unbiased clustering analysis shows that the abnormal transcriptomic profile of hDup mice is rescued 2 weeks after the treatment. Long-term partial rescue of the gene expression was observed at 5 weeks and until 16 weeks after the treatment as the transcriptomic profile does not cluster with the control-ASO treated mice. Not surprisingly, at one week after treatment, where MeCP2 protein concentration has not been normalized, the gene expression is close to control-ASO treated hDup mice. Furthermore, close examination of RNA expression of selected genes that are consistently misregulated in MDS (15, 36) revealed partial or total normalization, with each gene having its own particular response to the treatment (Fig. 4E).

Reversal of behavioral and molecular phenotypes after ASO treatment in humanized MDS mice

To test whether normalizing MeCP2 protein concentration affects the behavioral phenotype of the humanized MDS mice, we injected hDup mice (8 to 9 weeks old) with either 250µg or 500µg MECP2-ASO in the right lateral ventricle and performed a series of behavioral tests at two time points, 5 weeks and 9 weeks after ASO administration. While none of the behaviors was rescued by 5 weeks (fig. S3A-C), there was a dose-dependent improvement in humanized MDS mice at 9 weeks after the injection. In the open field test, hDup mice displayed normal locomotor activity but reduced exploratory behavior (rearing), which was rescued by 500µg MECP2-ASO treatment (Fig. 5A). In the fear conditioning test, hDup mice displayed an abnormal increase in fear learning in both context and cue paradigms. The abnormal contextual learning was normalized by the 500µg MECP2-ASO treatment, and we observed a trend to improvement in the cued learning (Fig. 5B). In the accelerating rotarod test, both MECP2-ASO doses reversed the prolonged latency to fall from the rotating rod (Fig. 5C). In the elevated plus-maze test, hDup mice showed increased anxiety-like behavior, which was not rescued by ASO treatment (Fig. 5D). The greater brain weight was also not improved by MECP2-ASO treatment (fig. S3D). Finally, the expression of select MeCP2-regulated genes was rescued in the cortex by the MECP2-ASO treatment (Fig. 5E).

Fig. 5. MECP2-ASO treatment dose-dependently rescues behavioral and molecular deficits in humanized MECP2 duplication mice.

(A) Activity and exploratory (rearing) behavior of 17-week-old mice in the Open field assay nine weeks after ASO treatment. (B) Contextual and cued fear conditioning test for learning and memory 11 weeks after ASO treatment. (C) Motor coordination in the accelerated rotarod, 10 weeks after ASO treatment. D1, day 1. (D) Anxiety-like behavior measured by elevated plus maze test nine weeks after ASO treatment. (E) qRT-PCR shows the expression of selected MeCP2-regulated genes after the ASO 500µg dose treatment (n=5). All behavioral data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by Fisher’s LSD post hoc test. n = 15 for hMECP2-GFP; ctrl group; n = 13 for hDup; ctrl group; n = 14 for hDup; 250µg MECP2-ASO group; n = 13 for hDup; 500µg MECP2-ASO group. Rotarod test was analyzed by two-way ANOVA with repeated measures. n = 9 for hMECP2-GFP; ctrl group; n = 10 for hDup; ctrl group; n = 10 for hDup; 250µg MECP2-ASO group; n = 10 for hDup; 500µg MECP2-ASO group. Data are presented as mean ± s.e.m. *P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001. hMECP2-GFP; ctrl - hMECP2-GFP mice injected with control-ASO. hDup; ctrl - hDup mice injected with control-ASO. hDup; 250µg - hDup mice injected with 250µg MECP2-ASO. hDup; 500µg - hDup mice injected with 500µg MECP2-ASO.

Discussion

Using a new humanized mouse model of MDS, this study highlights the feasibility of titrating ASOs to decrease MeCP2 expression. We found that the expression of MECP2 RNA is downregulated more rapidly than protein concentration, possibly because of the relatively long half-life of MeCP2 (37). The longitudinal transcriptomic profiling we performed demonstrates the potential of the ASO treatment to reverse the molecular deficits underlying MDS pathology. The effect of the treatment on the expression of specific downstream MECP2-regulated genes is particularly interesting. The expression of Npbwr1 and Tsc22d3 slowly normalized, reaching a maximum effect at 12 weeks. In contrast, AW551984 and Efemp1 were quickly normalized after 1–2 weeks, and the effect was sustained for at least 16 weeks, even though MECP2 expression had returned to pre-treatment amount. Gdf11 behaved differently, becoming completely normalized early on at 5 weeks, but starting to return to abnormal expression from week 12 onward. The effect on Crh was more variable, resulting in a partial rescue at 12 weeks.

Characterization of the pharmacodynamics of important MeCP2-regulated genes might help in guiding future clinical interventions. For instance, based on the effect of the ASO treatment on MeCP2 expression over time (Fig. 4A-C), one might be tempted to administer a second dose of ASO s somewhere between 8 and 12 weeks after the first injection—but because the effect on some downstream genes takes longer to arise, a second dose at 8–12 weeks might bring their expression too much below or above normal. Therefore, when deciding on the frequency of the ASO delivery, the dynamics of the target protein as well as its downstream regulated genes should be both considered.

Variation in the expression dynamics of downstream genes could also provide insight into the potential primary and secondary targets of MeCP2. If a gene responds to MeCP2 downregulation immediately and tracks precisely with MeCP2 protein concentration, it is likely that it is a primary target.

Although the transcriptomic profile appears to be normalized 2 weeks after the ASO treatment, behavioral rescue was not achieved until 9 weeks after treatment. It is possible that the beneficial effect of MeCP2 downregulation on the global proteome and the neuronal circuits lags behind that of the transcriptome, taking more time to be reversed. Indeed, our previous study already demonstrated that it takes at least a month from the moment MeCP2 protein concentration is normalized to the behavioral rescue (15).

It is interesting that different behaviors responded at different ASO doses. A low dose rescued the abnormal latency to fall on the rotarod test, which could be related to repetitive movements or perseverative behavior in human patients. A higher dose was required to ameliorate learning deficits, however, it did not rescue anxiety-like behavior. Reversal of anxiety phenotype might require multiple dosages and chronic treatment, or a higher ASO dose. The highest safe dose of the specific ASO used in this study was limited to 500 µg. Therefore, moving forward to a clinical trial, further screening and testing will be needed to identify new clinical-grade high-efficacy ASOs. It is also possible that additional interventions such as supportive behavioral therapies might be needed to overcome anxiety encountered during critical periods in human patients.

The significance of the present study is four-fold. First, it sets the stage for a promising interventional approach for children with MDS by providing critical information on the way MECP2-ASOs work in vivo. Second, dosage-sensitive genes are involved in many neurodevelopmental disorders caused by either duplications and or a gain of function; this ASO approach could conceivably be applied to other dosage-sensitive genes. Third, this is the first pre-clinical study to test ASO effects on a dosage-sensitive protein in the context of human genes and not mouse genes. Pre-clinical studies should use animal models with the strongest possible construct and face validity. In the case of the new humanized MDS mouse model, it is clear how critical titration is for dosage-sensitive genes and that time is required to restore normal behavior without causing secondary toxicity. Fourth, changes in gene expression are the earliest demonstration of a response to therapy. The molecular changes appeared once the MeCP2 protein concentration normalized and preceded behavioral changes by almost 2 months. This is noteworthy in that it points to the value of using molecular data as an early biomarker for target engagement and dosing guidance. Interestingly, in our study, administration of the highest safe dose of 500µg MECP2-ASO did not have any apparent toxicity, even though the MECP2 mRNA was suppressed slightly below normal amount. Lastly, it was encouraging to see that IFN-γ expression was corrected in the blood after icv injection of the ASO, providing an avenue to interrogate peripheral markers while testing safety and dose optimization in humans.

Materials and Methods

Study design

The goal of our study is to set a stage for an interventional approach using antisense oligonucleotide treatment for children with MECP2 duplication syndrome. To do so, we first generated a humanized mouse model of MECP2 duplication syndrome that carries two copies of human MECP2 alleles without the endogenous mouse copy, by breeding two transgenic human MECP2 mouse lines. Our in-depth characterization of the mouse model includes the expression and localization of MeCP2 and a series of behavioral assays to measure locomotion, motor coordination, anxiety, social and learning behaviors. Distribution and effectiveness of intracerebroventricular injection of the MECP2-ASO were assessed biochemically and immunohistochemically throughout the brain. Further transcriptome analysis was conducted to assess the gene expression changes and their relationship to the pharmacodynamics of ASO-mediated MeCP2 downregulation. Dose-dependent molecular and behavioral rescue was demonstrated by biochemical and behavioral assays.

Animal care and related surgical procedures followed institutional guidelines and was conducted with approval of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Baylor College of Medicine. Animals were randomly selected using Excel software to generate a table of random numbers for all treatment studies. For all experiments, the individuals performing the behavioral and electrophysiological studies were blinded to the genotype or treatment. n values represent the number of animals in the experiment and were included in the figure legend.

Mouse generation

As a first step to generate transgenic mice carrying two alleles of human MECP2 and no endogenous mouse Mecp2 alleles, we eliminated the endogenous mouse allele from our transgenic lines MECP2Tg1 (C57Bl/6) (38) and MECP2-GFP (FVB /N) (39) by breeding them with Mecp2+/− females. Then, Mecp2-null; MECP2Tg1 and Mecp2-null; MECP2-GFP were mated to generate F1 hybrid mice with two copies of human MECP2 and their single MECP2 allele control littermates (see scheme in Figure 1).

Intracerebral injection of ASO

Animals were anaesthetized with a mix of ketamine 37.6 mg ml−1, xylazine 1.92 mg ml−1 and acepromazine 0.38 mg ml−1and placed on a computer-guided stereotaxic instrument (Angle Two Stereotaxic Instrument, Leica Microsystems) that is fully integrated with the Franklin and Paxinos mouse brain atlas through a control panel. Buprenorphine slow-release (1 mg kg−1) was injected subcutaneously 1 hr prior to the surgery. Meloxicam (5 mg kg−1) was administered subcutaneously 30 mins prior to the surgery, and for 3 consecutive postoperative days. After sterilizing the surgical site with betadine and 70% alcohol three times, a midline incision was made over the skull and a small hole was drilled through the skull above the right lateral ventricle. The coordinates used relative to bregma were: antero-posterior = 0.3 mm, medial-lateral= 1 mm, dorsal-ventral= −3 mm. A total dose of 150µg, 250µg or 500µg MECP2-ASOs or control-ASO was delivered using a Hamilton syringe connected to a motorized nanoinjector within 30 seconds. To allow diffusion of the solution into the brain, the needle was left in the site of injection for 5 min. The incision was manually closed with suture and 3M Vetbond tissue adhesive. Mice were monitored until they fully recovered, and monitoring continued for at least 3 days.

Brain lysates preparation and Western Blot

Brains were dissected and homogenized in cold lysis buffer (20mM Tris-HCl pH=8.0, 180mM NaCl, 0.5% NP-40, 1mM EDTA, 2% SDS, Complete Protease inhibitor, Roche). Lysates were rotated at room temperature for 20 min and then centrifugated at maximum speed for 20 min. The supernatant was then mixed with NuPAGE sample buffer, heated for 10 min at 95°C and run on a NuPAGE 4–12% Bis-Tris gradient gel with MES SDS running buffer (NuPAGE, Carlsbad, CA). Separated proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membrane using NuPAGE transfer buffer for 2.5h at 4°C. The membrane was blocked with 5% milk in TBS with 2% Tween-20 (TBST) for 1 hr and incubated with primary antibody overnight at 4°C. After three times of washing with TBST, the membrane was incubated with secondary antibody for 1–2h at room temperature followed by washing. Horseradish peroxidase (HRP) was detected using ECL detection kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Images were acquired by ImageQuant LAS 4000 (GE Healthcare). Antibodies used were: rabbit antiserum raised against the amino terminus of MeCP2 (1:5,000; Zoghbi laboratory), rabbit anti-H3 (1:5,000; Cell signaling, #4499), goat anti-rabbit HRP (1:20,000; Bio-rad). Vertical black line in the figure caption indicates image splicing.

RNA-seq

Library Preparation with polyA selection and HiSeq Sequencing

RNA library preparations and sequencing reactions were conducted at GENEWIZ, LLC. (South Plainfield, NJ, USA). RNA samples received were quantified using Qubit 2.0 Fluorometer (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and RNA integrity was checked using Agilent TapeStation 4200 (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, USA).

RNA sequencing libraries were prepared using the NEBNext Ultra RNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina using manufacturer’s instructions (NEB, Ipswich, MA, USA). Briefly, mRNAs were initially enriched with Oligod(T) beads. Enriched mRNAs were fragmented for 15 minutes at 94 °C. First strand and second strand cDNA were subsequently synthesized. cDNA fragments were end repaired and adenylated at 3’ends, and universal adapters were ligated to cDNA fragments, followed by index addition and library enrichment by PCR with limited cycles. The sequencing library was validated on the Agilent TapeStation (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, USA), and quantified by using Qubit 2.0 Fluorometer (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) as well as by quantitative PCR (KAPA Biosystems, Wilmington, MA, USA).

The sequencing libraries were clustered on a single lane of a flowcell. After clustering, the flowcell was loaded on the Illumina HiSeq instrument (4000 or equivalent) according to manufacturer’s instructions. The samples were sequenced using a 2×150bp Paired End (PE) configuration. Image analysis and base calling were conducted by the HiSeq Control Software (HCS). Raw sequence data (.bcl files) generated from Illumina HiSeq was converted into fastq files and de-multiplexed using Illumina’s bcl2fastq 2.17 software. One mismatch was allowed for index sequence identification.

RNAseq analysis

Adapter sequences were removed from raw sequencing reads using Trimmomatic (v0.36). Trimmed reads were then aligned to reference genome of GRCm38p6 (GENCODE vM18 Primary assembly) with the GRCh38 copy of MeCP2 added using STAR aligner (40) (v2.6.0a) at default parameters besides --limitOutSJcollapsed 3000000. Differential gene expression (DEG) analyses on the read counts were performed using DESeq2 (41) (v1.24.0) in an R environment. Genes with total read counts averaging less than 10 in at least half of the samples were filtered out from analysis. A gene is considered significantly changed if the false discovery rate (FDR) is less than 10%. Expression heatmap of the 101 genes significantly changed between hDup; control ASO treated mice and hMECP2-GFP; control ASO treated mice were plotted using pheatmap function in the R environment.

Gene expression analysis by qRT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from different brain regions of adult mice using Qiagen RNeasy Mini kit and 3 µg was used to synthesize cDNA by M-MLV reverse transcriptase (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). RT–qPCR was performed in a CFX96 Real-Time System (Bio-Rad) using PerfeCTa SYBR Green Fast Mix (Quanta Biosciences). Sense and antisense primers were selected to be located on different exons. The specificity of the amplification products was verified by melting curve analysis. All RT–qPCR reactions were conducted in technical triplicates and the results were averaged for each sample, normalized to GAPDH expression, and analyzed using the comparative ∆∆Ct method. The following primers were used in the RT–qPCR reactions: MECP2 (common to human and mouse): 5′-TATTTGATCAATCCCCAGGG-3′ (sense), 5′-CTCCCTCTCCCAGTTACCGT-3′ (antisense); MECP2-e1 (human-specific): 5′-AGGAGAGACTGGAAGAAAAGTC-3′ (sense), 5′-CTTGAGGGGTTTGTCCTTGA-3′ (antisense); MECP2-e2 (human-specific): 5′-CTCACCAGTTCCTGCTTTGATGT-3′ (sense), 5′-CTTGAGG GGTTTGTCCTTGA-3’(antisense); Gapdh (mouse-specific): 5’-GGCATTGCTCTCAATGACAA −3′ (sense), 5’-CCCTGTTGCTGTAGCCGTAT-3′ (antisense); AW551984 (mouse-specific): 5’-CATAAGAGATCCAGTGGCAC-3’ (sense), 5’-AGTTTAGGGTTGCAGACAC-3′ (antisense); Efemp1(mouse-specific):5’-GCGCTGGTCAAGTCACAGTA-3’ (sense), 5’-AAGCATCTGGGACAATGTCAC-3’(antisense); Oprk1(mouse-specific): 5’-CGATAGTCCTTGGAGGCACC-3’ (sense), 5’-GGACTGGGATCACAAAGGCA-3’ (antisense); Npbwr1(mouse-specific): 5’-TCTCTTACTTCATCACCAGCC-3’ (sense), 5’- GCATAGAGGAAAGGGTTGAG-3’ (antisense); Crh(mouse-specific): 5’- GGAGAAACTCAGAGCCCAAGTA-3’ (sense), 5’-GTTAGGGGCGCTCTCTTCTCC-3’ (antisense); Tsc22d3(mouse-specific): 5’-ACTGGATAACAGTGCCTCC-3’ (sense), 5’- TCAGGTGGTTCTTCACGAG-3’ (antisense); Gdf11(common to mouse and human): 5’- TAAGCGCTACAAGGCCAAC-3’ (sense), 5’- AGGGATCTTGCCGTAGATAA-3’ (antisense).

Immunofluorescence

Animals were anaesthetized with a mix of ketamine 37.6 mg ml−1, xylazine 1.92 mg ml−1 and acepromazine 0.38 mg ml−1, and transcardially perfused with 20 ml PBS followed by 100 ml of cold PBS-buffered 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA). The brains were removed and post-fixed overnight in 4% PFA. Next, brains were cryoprotected in 4% PFA with 30% sucrose at 4 °C for two days and embedded in Optimum Cutting Temperature (O.C.T., Tissue-Tek). Free-floating 40-µm brain sections were cut using a Leica CM3050 cryostat and collected in PBS. The sections were blocked for 1 h in 2 % normal goat serum, 0.3% Triton X-100 in PBS at room temperature. Sections were then incubated overnight at 4 °C with either rabbit anti-MeCP2 antibody (1:1,000; Cell Signaling) or rabbit anti-ASO antibody (1:10,000; IONIS Pharmaceuticals). The sections were washed three times for 10 min with PBS and incubated for 2 h at room temperature with goat anti-rabbit antibody (1:500; Alexa Fluor 488, Invitrogen, A-11034). Sections were washed again three times for 10 min with PBS and mounted onto glass slides with Vectashield mounting medium with DAPI (Vector Laboratories).

ASO synthesis

Ionis Pharmaceuticals synthesized MECP2-ASOs as previously described(42). ASOs consist of 20 chemically modified nucleotides (MOE gapmer). The central gap of 10 deoxynucleotides is flanked on its 5′ and 3′ sides by five 2′-O-(2-methoxyethyl) (MOE)-modified nucleotides. The backbone modifications from 5′ to 3′ are: 1-PS, 4-PO, 10-PS, 2-PO and 2-PS. Phosphorothioate (PS) modifications were replaced with native phosphodiester (PO) in the MOE wings to reduce the overall PS content of the ASO, since a fully modified PS ASO is not necessary for robust CNS activity. The sequence of MECP2-ASO is 5’-TATGGTTTTTCTCCTTTATT-3’.

Video-electroencephalographic monitoring

Mice were anesthetized with isoflurane and mounted in a stereotaxic frame (David Kopf Instruments). Under aseptic condition, each mouse was implanted with cortical recording electrodes (Teflon-coated silver wire, bare diameter 125 µm, A-M Systems) aimed at the subdural space of the somatosensory cortex (0.8 mm posterior, 1.8 mm lateral to bregma) and the frontal cortex (1.8 mm anterior, 1.5 mm lateral to bregma), respectively. The reference electrode was then positioned in the occipital region of the skull. The third recording electrode constructed with Teflon-coated tungsten wire (bare diameter 50 µm, A-M systems) was stereotaxically implanted in the CA1 of the hippocampus (1.9 mm posterior, 1.0 mm lateral, and 1.3 mm ventral to bregma) with reference to the ipsilateral corpus callosum for local field potential (LFP) recordings. All electrode wires were attached to a miniature connector (Harwin Connector). After 8–10 days of post-surgical recovery, cortical electroencephalogram (EEG) activity and hippocampal LFP (both high-pass filtered at 0.5 Hz and digitized at 5 kHz) as well as synchronized animal behavior were recorded by Sirenia Acquisition system (Pinnacle Technology, Inc, USA) in freely moving mice for over 24 hours. All the EEG/LFP recordings and coherent animal behavior were manually analyzed under Sirenia Acquisition 2.0.8.

Behavioral assays

All data acquisition and analyses were carried out by an individual blinded to the genotype and treatment. All behavioral studies were performed during the light period. Mice were habituated to the test room for 30 min before each test. All mice were 8–9 weeks of age when we injected ASO; age of mice tested in each assay is indicated in text or figure legend. At least one day was given between assays for the mice to recover. All the tests were performed as previously described (43) with few modifications.

Open field test

After habituation in the test room (150 lx, 60 dB white noise), mice were placed in the center of an open arena (40 × 40 × 30 cm), and their behavior was tracked by laser photobeam breaks for 30 min. General locomotor activity was automatically analyzed using AccuScan Fusion software (Omnitech) by counting the number of times mice break the laser beams (activity counts). In addition, rearing activity, the time spent in the center of the arena, entries to the center and distance travelled were analyzed.

Elevated plus maze

After habituation in the test room (700 lx, 60 dB white noise), mice were placed in the center part of the maze facing one of the two open arms. Mouse behavior was video-tracked for 10 min, and the time mice spent in the open arms and the entries to the open arms, as well as the distance travelled in the open arms, were recorded and analyzed using ANY-maze system (Stoelting).

Partition test for social interaction

This assay was performed as previously described (43) with a few modifications. Experimental mice were singly housed for 24 hr in standard cages with transparent perforated Plexiglas barrier that separates the cage into two compartments. An age- and gender-matched C57BL/6J partner was placed in the opposite side of the partition cage on the second day. Social interaction scoring was carried out on the third day allowing at least 18 hr co-housing of the experimental and partner mice. The amount of time the experimental mouse exhibited direct interest into the partner in a 5-minute period was recorded using a handheld computer (Psion), and analyzed using the Observer program (Noldus). Three different interaction paradigms were assessed sequentially: experimental mouse versus familiar partner (Familiar 1), experimental mouse versus novel partner (Novel), and experimental mouse versus familiar partner again (Familiar 2).

Fear conditioning

A delayed fear conditioning protocol was employed to evaluate hippocampus-dependent contextual fear memory and hippocampus-independent cue fear memory. On day 0 animals were trained in a mouse fear conditioning chamber with a grid floor that can deliver an electric shock (Med Associates, Inc.). This enclosure was located in a sound-attenuating box that contained a digital camera, a loudspeaker and a house light. Each mouse was initially placed in the chamber and left undisturbed for 2 min, after which a tone (30 s, 5 kHz, 80 dB) coincided with a scrambled foot shock (2 s, 0.7 mA). The tone/foot-shock stimuli were repeated after 2 min. The mouse was then returned to its home cage. The context test was assessed in 24 hours. The mice were placed in exactly the same environment and observed for 5 min. The cued fear test was assessed one hour after the context test. The mice were placed in a novel environment for 3 min, followed by a 3 min tone. Mouse behaviour was recorded and scored automatically by ANY-maze (Stoelting). Freezing, defined as the absence of all movement except for respiration, was scored only if the animal was immobile for at least 1 s. The percentage of time spent freezing during the tests serves as an index of fear memory.

Accelerating rotarod test

After habituation in the test room (700 lx, 60 dB white noise), motor coordination was measured using an accelerating rotarod apparatus (Ugo Basile). Mice were tested for four consecutive days, four trials each, with an interval of 60 min between trials to rest. Each trial lasted for a maximum of 10 min, and the rod accelerated from 4 to 40 r.p.m. in the first 5 min. The time that it took for each mouse to fall from the rod (latency to fall) was recorded.

Three-Chamber test

The three-chamber apparatus consists of a clear Plexiglas box (24.75 × 16.75 × 8.75) with removable partitions that separate the box into three chambers. In both left and right chambers, a cylindrical wire cup was placed with the open side down. Age and gender-matched C57Bl/6 mice were used as novel partners. Two days before the test, the novel partner mice were habituated to the wire cups (3 inches diameter by 4 inches in height) for 1 h per day. After habituation in the test room (700 lx, 60 dB white noise), mice were placed in the central chamber and allowed to explore the 3 chambers for 10 min (habituation phase). Next, a novel partner mouse was placed into a wire cup in either the left or the right chamber. An inanimate object was placed as control in the wire cup of the opposite chamber. The location of the novel mouse was randomized between left and right chambers across subjects to control for side preference. The mouse tested was allowed to explore again for an additional 10 min. The time spent investigating the novel partner (defined by rearing, sniffing or pawing at the wire cup) and the time spent investigating the inanimate object were measured manually.

Statistical analysis

GraphPad Prism 7 was used for statistical analysis. Statistical significance was set at P< 0.05 and data were plotted as means ± SEM. The number of animals (n) and the specific statistical tests for each experiment are indicated in the figure legends and supplementary table (Table S1). Two-tailed t tests were used when comparing two groups. One-way or two-way ANOVA followed by Fisher’s LSD post hoc test were used when comparing more than two groups. Sample size for behavioral studies was determined based on previous reports using transgenic mice with the same background. Mice were randomly assigned to vehicle or treatment groups using Excel software to generate a table of random numbers, and the experimenter was always blinded to the treatment. For behavioral assays, all population values appear normally distributed.

Supplementary Material

Fig. S1. Generation and characterization of a humanized MECP2 duplication mouse model

Fig. S2. Pharmacodynamics of 250µg of MECP2-ASO treatment

Fig. S3. MECP2-ASO treatment does not rescue abnormal behavior in humanized MECP2 duplication mice at an early time point

Table S1. Statistical significance for each figure

Acknowledgements:

We thank Yaling Sun for breeding the Mecp2+/− mice, and the behavioral core at Jan and Dan Duncan Neurological Research Institute for help with behavioral training.

Funding:

This project was funded by the NIH (5R01NS057819 to HYZ, 1F32HD100048–01 to SSB), the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HYZ), the Rett Syndrome Research Trust, The 401 project and the Baylor College of Medicine Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities Research

References

- 1.Guy J, Cheval H, Selfridge J, Bird A, The role of MeCP2 in the brain. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 27, 631–652 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chao HT, Zoghbi HY, MeCP2: only 100% will do. Nature neuroscience 15, 176–177 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meins M, Lehmann J, Gerresheim F, Herchenbach J, Hagedorn M, Hameister K, Epplen JT, Submicroscopic duplication in Xq28 causes increased expression of the MECP2 gene in a boy with severe mental retardation and features of Rett syndrome. J Med Genet 42, e12 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van Esch H, Bauters M, Ignatius J, Jansen M, Raynaud M, Hollanders K, Lugtenberg D, Bienvenu T, Jensen LR, Gecz J, Moraine C, Marynen P, Fryns JP, Froyen G, Duplication of the MECP2 region is a frequent cause of severe mental retardation and progressive neurological symptoms in males. Am J Hum Genet 77, 442–453 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.del Gaudio D, Fang P, Scaglia F, Ward PA, Craigen WJ, Glaze DG, Neul JL, Patel A, Lee JA, Irons M, Berry SA, Pursley AA, Grebe TA, Freedenberg D, Martin RA, Hsich GE, Khera JR, Friedman NR, Zoghbi HY, Eng CM, Lupski JR, Beaudet AL, Cheung SW, Roa BB, Increased MECP2 gene copy number as the result of genomic duplication in neurodevelopmentally delayed males. Genet Med 8, 784–792 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Friez MJ, Jones JR, Clarkson K, Lubs H, Abuelo D, Bier JA, Pai S, Simensen R, Williams C, Giampietro PF, Schwartz CE, Stevenson RE, Recurrent infections, hypotonia, and mental retardation caused by duplication of MECP2 and adjacent region in Xq28. Pediatrics 118, e1687–1695 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Amir RE, Van den Veyver IB, Wan M, Tran CQ, Francke U, Zoghbi HY, Rett syndrome is caused by mutations in X-linked MECP2, encoding methyl-CpG-binding protein 2. Nat Genet 23, 185–188 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lyst MJ, Bird A, Rett syndrome: a complex disorder with simple roots. Nat Rev Genet 16, 261–275 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leonard H, Cobb S, Downs J, Clinical and biological progress over 50 years in Rett syndrome. Nat Rev Neurol 13, 37–51 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lugtenberg D, Kleefstra T, Oudakker AR, Nillesen WM, Yntema HG, Tzschach A, Raynaud M, Rating D, Journel H, Chelly J, Goizet C, Lacombe D, Pedespan JM, Echenne B, Tariverdian G, O’Rourke D, King MD, Green A, van Kogelenberg M, Van Esch H, Gecz J, Hamel BC, van Bokhoven H, de Brouwer AP, Structural variation in Xq28: MECP2 duplications in 1% of patients with unexplained XLMR and in 2% of male patients with severe encephalopathy. European journal of human genetics : EJHG 17, 444–453 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lubs H, Abidi F, Bier JA, Abuelo D, Ouzts L, Voeller K, Fennell E, Stevenson RE, Schwartz CE, Arena F, XLMR syndrome characterized by multiple respiratory infections, hypertelorism, severe CNS deterioration and early death localizes to distal Xq28. American journal of medical genetics 85, 243–248 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ramocki MB, Tavyev YJ, Peters SU, The MECP2 duplication syndrome. American journal of medical genetics. Part A 152A, 1079–1088 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van Esch H, MECP2 Duplication Syndrome. Molecular Syndromology, (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Carvalho CM, Zhang F, Liu P, Patel A, Sahoo T, Bacino CA, Shaw C, Peacock S, Pursley A, Tavyev YJ, Ramocki MB, Nawara M, Obersztyn E, Vianna-Morgante AM, Stankiewicz P, Zoghbi HY, Cheung SW, Lupski JR, Complex rearrangements in patients with duplications of MECP2 can occur by fork stalling and template switching. Human molecular genetics 18, 2188–2203 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sztainberg Y, Chen HM, Swann JW, Hao S, Tang B, Wu Z, Tang J, Wan YW, Liu Z, Rigo F, Zoghbi HY, Reversal of phenotypes in MECP2 duplication mice using genetic rescue or antisense oligonucleotides. Nature 528, 123–126 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khorkova O, Wahlestedt C, Oligonucleotide therapies for disorders of the nervous system. Nat Biotechnol 35, 249–263 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bennett CF, Swayze EE, RNA targeting therapeutics: molecular mechanisms of antisense oligonucleotides as a therapeutic platform. Annual review of pharmacology and toxicology 50, 259–293 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Passini MA, Bu J, Richards AM, Kinnecom C, Sardi SP, Stanek LM, Hua Y, Rigo F, Matson J, Hung G, Kaye EM, Shihabuddin LS, Krainer AR, Bennett CF, Cheng SH, Antisense oligonucleotides delivered to the mouse CNS ameliorate symptoms of severe spinal muscular atrophy. Science translational medicine 3, 72ra18 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hua Y, Sahashi K, Rigo F, Hung G, Horev G, Bennett CF, Krainer AR, Peripheral SMN restoration is essential for long-term rescue of a severe spinal muscular atrophy mouse model. Nature 478, 123–126 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lagier-Tourenne C, Baughn M, Rigo F, Sun S, Liu P, Li HR, Jiang J, Watt AT, Chun S, Katz M, Qiu J, Sun Y, Ling SC, Zhu Q, Polymenidou M, Drenner K, Artates JW, McAlonis-Downes M, Markmiller S, Hutt KR, Pizzo DP, Cady J, Harms MB, Baloh RH, Vandenberg SR, Yeo GW, Fu XD, Bennett CF, Cleveland DW, Ravits J, Targeted degradation of sense and antisense C9orf72 RNA foci as therapy for ALS and frontotemporal degeneration. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 110, E4530–4539 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith RA, Miller TM, Yamanaka K, Monia BP, Condon TP, Hung G, Lobsiger CS, Ward CM, McAlonis-Downes M, Wei H, Wancewicz EV, Bennett CF, Cleveland DW, Antisense oligonucleotide therapy for neurodegenerative disease. The Journal of clinical investigation 116, 2290–2296 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wheeler TM, Leger AJ, Pandey SK, MacLeod AR, Nakamori M, Cheng SH, Wentworth BM, Bennett CF, Thornton CA, Targeting nuclear RNA for in vivo correction of myotonic dystrophy. Nature 488, 111–115 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carroll JB, Warby SC, Southwell AL, Doty CN, Greenlee S, Skotte N, Hung G, Bennett CF, Freier SM, Hayden MR, Potent and selective antisense oligonucleotides targeting single-nucleotide polymorphisms in the Huntington disease gene / allele-specific silencing of mutant huntingtin. Molecular therapy : the journal of the American Society of Gene Therapy 19, 2178–2185 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kordasiewicz HB, Stanek LM, Wancewicz EV, Mazur C, McAlonis MM, Pytel KA, Artates JW, Weiss A, Cheng SH, Shihabuddin LS, Hung G, Bennett CF, Cleveland DW, Sustained therapeutic reversal of Huntington’s disease by transient repression of huntingtin synthesis. Neuron 74, 1031–1044 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.DeVos SL, Goncharoff DK, Chen G, Kebodeaux CS, Yamada K, Stewart FR, Schuler DR, Maloney SE, Wozniak DF, Rigo F, Bennett CF, Cirrito JR, Holtzman DM, Miller TM, Antisense reduction of tau in adult mice protects against seizures. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience 33, 12887–12897 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meng L, Ward AJ, Chun S, Bennett CF, Beaudet AL, Rigo F, Towards a therapy for Angelman syndrome by targeting a long non-coding RNA. Nature, (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Scoles DR, Meera P, Schneider MD, Paul S, Dansithong W, Figueroa KP, Hung G, Rigo F, Bennett CF, Otis TS, Pulst SM, Antisense oligonucleotide therapy for spinocerebellar ataxia type 2. Nature 544, 362–366 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Friedrich J, Kordasiewicz HB, O’Callaghan B, Handler HP, Wagener C, Duvick L, Swayze EE, Rainwater O, Hofstra B, Benneyworth M, Nichols-Meade T, Yang P, Chen Z, Ortiz JP, Clark HB, Oz G, Larson S, Zoghbi HY, Henzler C, Orr HT, Antisense oligonucleotide-mediated ataxin-1 reduction prolongs survival in SCA1 mice and reveals disease-associated transcriptome profiles. JCI Insight 3, (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miller TM, Pestronk A, David W, Rothstein J, Simpson E, Appel SH, Andres PL, Mahoney K, Allred P, Alexander K, Ostrow LW, Schoenfeld D, Macklin EA, Norris DA, Manousakis G, Crisp M, Smith R, Bennett CF, Bishop KM, Cudkowicz ME, An antisense oligonucleotide against SOD1 delivered intrathecally for patients with SOD1 familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a phase 1, randomised, first-in-man study. The Lancet. Neurology 12, 435–442 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mercuri E, Darras BT, Chiriboga CA, Day JW, Campbell C, Connolly AM, Iannaccone ST, Kirschner J, Kuntz NL, Saito K, Shieh PB, Tulinius M, Mazzone ES, Montes J, Bishop KM, Yang Q, Foster R, Gheuens S, Bennett CF, Farwell W, Schneider E, De Vivo DC, Finkel RS, Group CS, Nusinersen versus Sham Control in Later-Onset Spinal Muscular Atrophy. N Engl J Med 378, 625–635 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bodda C, Tantra M, Mollajew R, Arunachalam JP, Laccone FA, Can K, Rosenberger A, Mironov SL, Ehrenreich H, Mannan AU, Mild overexpression of Mecp2 in mice causes a higher susceptibility toward seizures. Am J Pathol 183, 195–210 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Johnson BS, Zhao YT, Fasolino M, Lamonica JM, Kim YJ, Georgakilas G, Wood KH, Bu D, Cui Y, Goffin D, Vahedi G, Kim TH, Zhou Z, Biotin tagging of MeCP2 in mice reveals contextual insights into the Rett syndrome transcriptome. Nat Med 23, 1203–1214 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen L, Chen K, Lavery LA, Baker SA, Shaw CA, Li W, Zoghbi HY, MeCP2 binds to non-CG methylated DNA as neurons mature, influencing transcription and the timing of onset for Rett syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112, 5509–5514 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang T, Ramocki MB, Neul JL, Lu W, Roberts L, Knight J, Ward CS, Zoghbi HY, Kheradmand F, Corry DB, Overexpression of methyl-CpG binding protein 2 impairs T(H)1 responses. Sci Transl Med 4, 163ra158 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chahrour M, Jung SY, Shaw C, Zhou X, Wong ST, Qin J, Zoghbi HY, MeCP2, a key contributor to neurological disease, activates and represses transcription. Science 320, 1224–1229 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Samaco RC, Mandel-Brehm C, McGraw CM, Shaw CA, McGill BE, Zoghbi HY, Crh and Oprm1 mediate anxiety-related behavior and social approach in a mouse model of MECP2 duplication syndrome. Nat Genet 44, 206–211 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cheval H, Guy J, Merusi C, De Sousa D, Selfridge J, Bird A, Postnatal inactivation reveals enhanced requirement for MeCP2 at distinct age windows. Hum Mol Genet 21, 3806–3814 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Collins AL, Levenson JM, Vilaythong AP, Richman R, Armstrong DL, Noebels JL, David Sweatt J, Zoghbi HY, Mild overexpression of MeCP2 causes a progressive neurological disorder in mice. Hum Mol Genet 13, 2679–2689 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Heckman LD, Chahrour MH, Zoghbi HY, Rett-causing mutations reveal two domains critical for MeCP2 function and for toxicity in MECP2 duplication syndrome mice. Elife 3, (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dobin A, Davis CA, Schlesinger F, Drenkow J, Zaleski C, Jha S, Batut P, Chaisson M, Gingeras TR, STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 29, 15–21 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Love MI, Huber W, Anders S, Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol 15, 550 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Meng L, Ward AJ, Chun S, Bennett CF, Beaudet AL, Rigo F, Towards a therapy for Angelman syndrome by targeting a long non-coding RNA. Nature 518, 409–412 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chao HT, Chen H, Samaco RC, Xue M, Chahrour M, Yoo J, Neul JL, Gong S, Lu HC, Heintz N, Ekker M, Rubenstein JL, Noebels JL, Rosenmund C, Zoghbi HY, Dysfunction in GABA signalling mediates autism-like stereotypies and Rett syndrome phenotypes. Nature 468, 263–269 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1. Generation and characterization of a humanized MECP2 duplication mouse model

Fig. S2. Pharmacodynamics of 250µg of MECP2-ASO treatment

Fig. S3. MECP2-ASO treatment does not rescue abnormal behavior in humanized MECP2 duplication mice at an early time point

Table S1. Statistical significance for each figure