Abstract

Background

Pre-COVID-19 research highlighted the nursing profession worldwide as being at high risk from symptoms of burnout, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and suicide. The World Health Organization declared a pandemic on 11th March 2020 due to the sustained risk of further global spread of COVID-19. The high healthcare burden associated with COVID-19 has increased nurses’ trauma and workload, thereby exacerbating pressure on an already strained workforce and causing additional psychological distress for staff.

Objectives

The Impact of COVID-19 on Nurses (ICON) interview study examined the impacts of the pandemic on frontline nursing staff's psychosocial and emotional wellbeing.

Design

Longitudinal qualitative interview study.

Settings

Nurses who had completed time 1 and 2 of the ICON survey were sampled to include a range of UK work settings including acute, primary and community care and care homes. Interviewees were purposively sampled for maximum variation to cover a broad range of personal and professional factors, and experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic, including redeployment.

Methods

Nurses participated in qualitative in-depth narrative interviews after the first wave of COVID-19 in July 2020 (n = 27) and again at the beginning of the second wave in December 2020 (n = 25) via video and audio platform software. Rigorous qualitative narrative analysis was undertaken both cross-sectionally (within wave) and longitudinally (cross wave) to explore issues of consistency and change.

Results

The terms moral distress, compassion fatigue, burnout and PTSD describe the emotional states reported by the majority of interviewees leading many to consider leaving the profession. Causes of this identified included care delivery challenges; insufficient staff and training; PPE challenges and frustrations. Four themes were identified: (1) ‘Deathscapes’ and impoverished care (2) Systemic challenges and self-preservation (3) Emotional exhaustion and (4) (Un)helpful support.

Conclusions

Nurses have been deeply affected by what they have experienced and report being forever altered with the impacts of COVID-19 persisting and deeply felt. There is an urgent need to tackle stigma to create a psychologically safe working environment and for a national COVID-19 nursing workforce recovery strategy to help restore nurse's well-being and demonstrate a valuing of the nursing workforce and therefore support retention.

Keywords: COVID-19; Nurse wellbeing; Mental health; Qualitative; Longitudinal, moral distress; Stigma; Burnout; Compassion fatigue; Psychological support

What is already known

-

•

Nurses worldwide are at increased risk of poor mental health and suicide, compared to other sections of the working population.

-

•

The COVID-19 pandemic has added extra pressures making already difficult working conditions for nurses even harder.

-

•

Nurses are at high risk of burnout, moral distress and compassion fatigue because of the intense emotional work that they do.

What this paper adds

-

•

COVID-19 brought significant systemic challenges and a significantly altered workscape which triggered emotional exhaustion, burnout and compassion fatigue resulting in impoverished care, moral distress and intention to leave.

-

•

Redeployment practices need careful management with sufficient training and the ability of staff to ask for help or raise concerns being paramount.

-

•

Stigmatisation of disclosure of poor mental health is prevalent, but nurses highlighted the importance of deriving support from self-developed social groups with others ‘who have been through the same thing.’

1. Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) declared a pandemic on 11th March 2020 (WHO, 2021). In the UK, there have been approximately four waves of COVID-19 since March 2020 with over 15,000 recorded deaths (ONS, 2021). The large numbers of cases and deaths in the UK have posed a major challenge to nurses and midwives working across the health and social care sector. Throughout this paper we use the generic term nurses to include registered nurses and midwives as well as student nurses.

Prior to the pandemic, there were already considerable demands on the global nursing workforce. These included long working hours, shift work, staff shortages, and sometimes challenging and distressing work. These working conditions left nursing staff at high risk of experiencing primary and secondary traumatic stress, burnout, compassion fatigue, and moral distress (Kinman et al., 2020; Morley et al., 2019). Data from the UK and USA shows that suicide rates in nurses exceed the national average, with 300 nurses in England and Wales taking their own lives between 2011 and 2017 (Kinman et al., 2020; Davis et al., 2021).

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the already poor state of some nurses’ mental health was further exacerbated by unprecedented demands and unfamiliar working conditions over a prolonged period of time (Kinman et al., 2020, West and Bailey, 2020). Our longitudinal three time point survey conducted over the first wave of the pandemic found that, even three months after the first wave had subsided, 30% of nurses reported symptoms consistent with PTSD (Couper et al., 2022). These findings align with many other studies (e.g. Ali et al., 2021; Greenberg et al., 2021). Research on healthcare professionals during COVID-19 shows a high incidence of depression, anxiety and insomnia (Lai et al., 2020; Lapum et al., 2020; Labrague and de los Santos, 2020; Ohta et al., 2020; Siddiqui et al., 2021). Limitations of these COVID-19 workforce studies to date include cross-sectional designs with many studies focusing on hospital nurses, particularly those working in Intensive Care Units (ICU). Indeed, our own initial survey findings highlighted the urgent need for qualitative research to understand the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on nurses in more depth, hence this study (Couper et al., 2022).

Concerns have been expressed that the COVID-19 pandemic may impact nursing staff retention negatively, thereby reducing care quality in the future (British Academy, 2021a). Ustun's (2021) international review highlighted the dire effects of pandemic working conditions with primary traumatic stress, secondary traumatic stress, job burnout, compassion fatigue and moral injury as the main impacts. Previous research has revealed relationships between staff wellbeing at work and patient experiences of care (NHS Health and Wellbeing, 2009; Maben et al., 2012). There was therefore a need to better understand nurse distress and the psychological health needs of nurses during COVID-19, and beyond. This study examining the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the psychological experiences of nurses from multiple settings and specialities during the trajectory of COVID-19 in the UK, is therefore, timely. It enables us to better understand in some depth the impact of this latest pandemic, to put in place recommendations and improve preparation for further pandemics to better safeguard the psychological wellbeing of nurses. In this study we use Warr's (1987) definition of wellbeing at work which encompasses individual subjective experiences at work (job dissatisfaction and positive and negative work-related affect) as well as psychological and physiological aspects of employee health at work (outcomes) for example job-related stress anxiety, burn out and exhaustion (Warr, 1987).

2. Methods

2.1. Aim

To explore the range of experiences of nurses working at the ‘frontline’ of the COVID-19 pandemic in the UK and the possible impacts on their psychosocial and emotional wellbeing.

2.2. Study design

We designed a longitudinal qualitative study to explore a range of nurses’ COVID-19 experiences over two time points. Philosophically, our study was underpinned by a social constructivist approach (Burr, 2015). We wanted to elicit stories that anchored people to events during the pandemic selecting the narrative interview method to generate such rich qualitative data (Hollway and Jefferson, 2013, 2005; Greenhalgh et al., 2005; Harding, 2006; Thomson et al., 2002; Rosenthal, 2004; Ramvi, 2015). In both the generation and the analysis of our qualitative data we were concerned with the notion of ‘Gestalt’, or the idea that ‘the whole is greater than the sum of its parts’ (Hollway and Jefferson, 2013:68). We thus took steps to protect the narrative arcs of participants and counteract data fragmentation through specific analysis techniques (see below) to explore changes across the two time points (Hermanowicz, 2013).

2.3. Sampling and recruitment

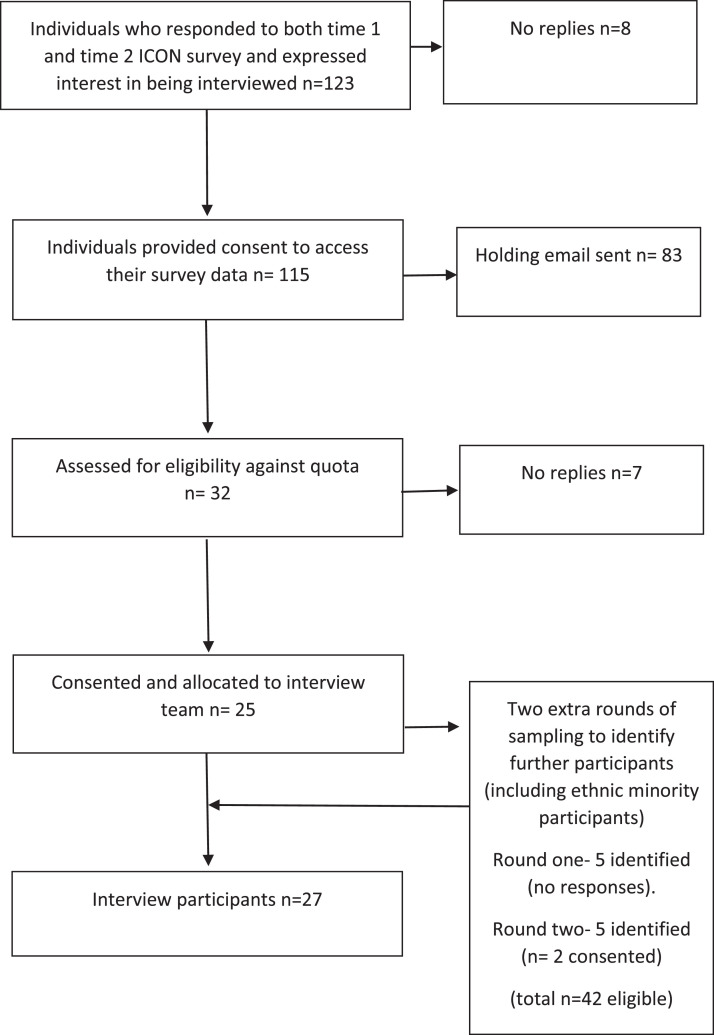

Interviewees (n = 27 time 1 and n = 25 time 2) were purposively sampled for maximum variation to gain a broad range of nurses of differing ages and experience, from differing grades, specialities settings and parts of the UK, using quota sampling (Robinson, 2014). The breadth of sampling was necessary to try and capture nurses’ UK COVID-19 experience where possible, in a range of care settings, taking account of regional variation in COVID-19 intensity and the range of nurses’ experiences at different grades, both in and outside ICU and to understand the impact of redeployment. We wanted to gather a range of narratives from across the UK about a unique historical event namely nurses’ experiences of the impact of working through the COVID-19 pandemic. Using the concept of "information power" to guide adequate sample size for qualitative studies (Malterud et al., 2016) data saturation was achieved. The participant sampling for this study included those who had completed both of the first two ICON national nurse and midwife surveys (April and May 2020) and who expressed an interest in being contacted to take part in further research (Couper et al., 2022). Of those contacted via email, 123 individuals expressed an interest in taking part. Following stratification based on purposive sampling criteria and sample quota (see Table 1 below for further details) 42 individuals were identified as eligible and invited to interview and in total 27 responded and took part (see Fig. 1 below).

Table 1.

Sample quota target list and sample representation.

| Target population / characteristic | Target quota of participants | Representation in sample |

|---|---|---|

| Self-identified as a member of an ethnic minority group | At least 5 | 3 |

| Work in social care (including care homes) | At least 3 | 1 |

| Work in the community or primary care | At least 5 | 5 |

| Work in ICU permanently (not redeployed) | At least 5 | 2 |

| Work in other acute care (not ICU) (including midwifery) | At least 5 | 5 |

| Have been redeployed | At least 10 (at least 3 of these to ICU) | 18 (7 of these to ICU) |

| Score highest on Depression Anxiety Stress Scales | At least 10 | 8 |

| Score lowest on Depression Anxiety Stress Scales | At least 10 | 5 |

| Work in mental health/ learning disability settings | At least 5 | 3 |

| Work as midwives | Up to 5 | 1 |

| Student nurses/ midwives | At least 5 | 0 |

| Live in Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales | Up to 5 from each area | 0 Northern Ireland 1 Scotland 1 Wales |

| Live in the regions of England (London and South East, North, Midlands, East of England, South of England and South West) | Up to 5 from each area | 7 London and South East 5 North 4 Midlands 2 East of England 5 South of England 2 South West |

Fig. 1.

Interview sampling diagram.

Sampling was not discrete as one individual participant could reside in multiple categories.

2.4. Data collection

In-depth qualitative narrative interviews were conducted with a purposive sample of nurses from England, Scotland and Wales, working in a range of settings after the first wave of COVID-19 in July 2020 (sample 1, n = 27). The same nurses were interviewed again during the second wave in December 2020 or January 2021 (n = 25). All interviews were conducted remotely via video and audio platforms. An interview topic guide was used loosely, was non-directive and covered a range of topics including exploring the impact of the pandemic on nurses’ psychological wellbeing (see supplementary file). As in narrative interviews the researchers invited participants to ‘‘tell me what happened’’ and allowed them to speak uninterrupted until their story ended (Greenhalgh et al., 2005). We used open-ended questions, elicited narratives and followed respondents ordering and phrasing to allow participants to discuss areas they perceived to be relevant (Hollway and Jefferson, 2013, 2005), using the interview topic guide as prompts only where needed (Greenhalgh et al., 2005). We did not wish to dictate that the narrative interview had to follow chronological order (e.g. Harding, 2006), thus interviews were flexible and not all questions in the topic guide were used with every individual. Longitudinal qualitative methods, in the form of repeat interviews, were used to identify and characterise personal trajectories as the pandemic progressed. The impact of working during COVID-19 on nurses’ practice over time was evaluated, through thorough probing, (Hermanowicz, 2013) as the stressors of working during the pandemic changed and was placed within the context of their working lives and lived experiences (Harding, 2006; Ramvi, 2016).

Four researchers (JM, RH, DK, BK) each interviewed five participants; interviewing the same participants at both time points to ensure continuity during the first and second waves of the interviews. (RA) interviewed seven participants during the first interview wave and (AC) interviewed five of these during the second wave (maternity leave prevented continuity). To ensure rigour the interviewers met regularly to discuss the narrative style of interviewing, the topic guide and the process and approaches taken to ensure consistency. The main strength of the narrative interview is its inherent subjectivity, which resonates with the nature of this qualitative research where the interviews were co-constructed with the interviewer. JM, RH, DK, BK are Professors of Nursing and (BK) worked clinically during the pandemic in ICU. All the team are female except (DK). All those who undertook interviews (AC, RA, JM, RH, DK, BK) are experienced qualitative researchers and have considerable experience in conducting interviews on distressing topics and approached interviewees sensitively, offering opportunities to pause or stop the interview if needed. A list of wellbeing resources and the opportunity to speak with a member of the research team after each interview was offered to participants to facilitate access to further support if needed, and the team supported each other with the emotional effects of interviewing which was at times demanding and distressing (Conolly et al., 2022).

Interview time for first and second wave interviews ranged from 45 to 90 min with one participant undertaking a further 90 min interview after her first interview to provide more details and clarification. All interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim, with all recordings and transcripts held securely on password-protected computers. The interviews were anonymised through the removal of identifying information and allocation of pseudonyms. (AC) initiated data analysis by becoming immersed in the data through reading interview transcripts.

2.5. Data analysis

We organised data for analysis in two ways, which overlapped. Firstly, to facilitate the organisation of the data (Elliott, 2018) we used NVivo12 to develop inductive codes and subsequent themes across each of the two datasets (first and second interviews). Our systematic production and application of emergent codes enabled the reflection of the view of participants in, what has been espoused to be, a traditional qualitative manner (Elliott, 2018). Secondly, to avoid fragmentation of the data, which can occur with systematic coding, we wrote participant interview summaries, or pen portraits (Hollway and Jefferson, 2013) to preserve each participant's narrative. Narrative analysis identifies segments of text that take the form of narrative, and examines structural and linguistic features to analyse how they support particular interpretations of the lived experience of a research participant (Riessman, 1993, Riessman, 2002). In this manner we tried to identify the story as a whole, rather than segments of text and used Muller's (1999) five overlapping stages of narrative analysis to guide the development of these pen portraits (Muller, 1999). Mishler (1999) argues that narrative is an umbrella term, which covers a large and diverse range of approaches. Our narrative approach had some overlap with the earlier coding and theme generation stage of the analysis and included reading and preliminary coding to gain familiarity; finding connections in the data through successive readings and reflection, searching the text and other sources for alternative explanations and confirmatory and disconfirming data and finally writing up an account of what has been learned, and illustrating (representing) the narrative arcs in the pen portraits, as well as selecting representative quotes (Hollway and Jefferson, 2013; Greenhalgh et al., 2005). Inter-rater reliability (Elliott, 2018) was achieved by AC leading the coding process with a sub-sample of transcripts selected for additional analysis by ER to challenge or corroborate and legitimate the codes (Charmaz, 2006; Mills et al., 2006). These primary level codes, were then collapsed into themes at a secondary level, thus themes were formed of the analysis of codes, rather than data (Elliott, 2018). The pen portraits, along with the secondary level themes, became essential tools to aid a holistic analysis of each participant (Hollway and Jefferson, 2013). As per longitudinal data analysis (Hermanowicz, 2013), each data set was subjected to within-wave analysis and data from each interview then compared with previous data from the same interviewee to facilitate both longitudinal and cross-sectional analysis. We report key differences between participants circumstances and perspectives between their first and second interviews in Table 2 below.

Table 2.

Demographics of participants and changed experiences over timea.

| Pseudonym | Age | Ethnicity | Pre-COVID role | Grade | DASS score | Redeployed In 1st wave | Accessed MH resources offered by Employers | Time off due to stress or COVID | 1st interview |

2nd interview |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Circumstances | Wellbeing / impacts of COVID-19 | Circumstances | Wellbeing / Impacts of COVID-19 | |||||||||

| Laura | 31–35 | White British | Hospital based | 6 | Mid | Yes – ICU | No | No | Just finished her redeployment to ICU | Angry, e.g. public wrongly wearing facemasks | She left the NHS after 1st wave, continued bank shifts | Stressed and angry |

| Camila | 46–50 | White British | Hospital based manager | 7 | High | Yes – green zonesb | Accessed counselling but not through her Trust | Yes with long-COVID | Just returned to pre-COVID role after redeployment to green (non-COVID) zones | Angry - particularly at the public for not wearing PPE | Returned to pre-COVID role Time off work helped her to recover | She was beginning to feel better |

| Sarah | 26–30 | White British | Hospital based | 5 | Mid | Yes – ICU | No, has accessed counselling via a charity | No | Just returned to pre-COVID role after ICU redeployment | Anxious and distressed | Returned to pre-COVID role. Ward re-configured & received promotion | Undervalued, sad and disappointed |

| Jo | 46–50 | White British | Hospital based clinical | 8a | High | Yes – ICU outreach | Yes accessed via Trust | No | Just returned to pre-COVID-19 role after redeployment | Felt useful but stressed | Returned to pre-COVID role | Stressed due to lack of doctors |

| Isla | 36–40 | Mixed multiple ethnicities | Private hospital | 6 | Low | No | No | No | Remained in pre-COVID role | Unhappy with treatment from employer | No second interview | No second interview |

| Rachel | 31–35 | White British | Research nurse | 7 | Low | Yes – ED | Used the Headspace app | No | Returned to pre-COVID role after redeployment to multiple locations | Felt anxious | Embarked on focused research and will not face further redeployment | Survivor guilt - leaving patients and colleagues |

| Becky | 46–50 | White British | Social care charity | 9 | Mid | No | No | No | Remained in pre-COVID role | Stressed, pressure managing staffs’ fears | She was promoted | Some people left - got rid of toxic culture which existed in first wave |

| Alison | 46–50 | White British | Mental Health(MH) community | 8a | Low | Yes, COVID ward, MH hospital | No | No | Just returned to her pre-COVID role after redeployment | Less autonomy; difficulty questioning decisions | Returned to pre-COVID role | Currently community work is isolating because of working from home |

| Tessa | 46–50 | White Irish | Hospital based | 7 | High | Yes – ICU | Used Headspace app & counselling | Time off due to stress | Just returned from her redeployment to ICU | Abandoned and less autonomy | Redeployed again - spent little time in her pre-COVID role since COVID onset | Angry, let down and stressed. Worried about career progression |

| Ellie | 31–35 | White British | Hospital based | 7 | Mid | Yes – ICU | Considering accessing counselling | No | Just returned to pre-COVID role from her redeployment | She liked the good team support and culture she had with colleagues | Redeployed to ICU again (Since COVID onset spent little time in pre-COVID role) | Anxious, upset and exhausted |

| Mary | 51–55 | White British | Hospital improvement | 7 | High | Yes – to green wardsb | No | No | Working in her pre-COVID role, redeployment did not last long- a few clinical shifts | Felt angry, e.g. public not wearing face masks properly | Spent a lot of time on the wards doing lots of improvement work | Has not felt well supported by managers which has been stressful |

| Peter | 20–25 | Not stated | Specialist role | 6 | Mid | Yes, infection control | No | No | Working in specialist setting | Stressed & anxious; raising concerns during COVID | He has left the NHS | Stressed before leaving. Job felt too political. |

| Mia | 56–60 | White British | Community | 6 | Low | No | No | No | She continued to work in her pre-COVID role | Stressed regarding conflicts with managers e.g. PPE donning | Continued to work in her pre-COVID role | Stress due to conflict between returning shielding staff & others |

| Sherie | 51–55 | White British | Hospital based | 6 | High | Yes – red COVID wardb | No | No | She was redeployed to a COVID ward | She felt distress, but also pride | Returned to pre-COVID role | Stressed, over-stretched, catching up backlog |

| Sophie | 46–50 | White British | Community nurse | 6 | Low | Yes –community team | No | No | Working on the different community team that she joined during COVID | Angry / Lack of autonomy / not well supported | She has stayed with the team she was redeployed to | Stressed, lack of meetings and training in procedures etc |

| Gaby | 56–60 | White British | Health visitor | 6 | Mid | Yes –community hospital | No | Yes | Off sick with long COVID after redeployment | Stressed, distressing and traumatic events | Returned to pre-COVID role | Felt traumatised. Declined further redeployment |

| Isabella | 51–55 | White British | Hospital based | 7 | High | Yes – ICU | Psychologist via a charity | No | Just returned to pre-COVID role after redeployment to ICU and other red wards | She felt very unsupported, encountered unsupportive teams, and found the work hard and distressing | Returned to pre-COVID role | She declined to be redeployed again. She felt less compassionate at work and irritable |

| Catherine | 41–45 | White British | Mental health unit | 9 | Mid | Yes- to aid clinical perspectives on MH | No | No | Mostly remained in her pre-COVID role with 1 or 2 days per week redeployed | Anxious regarding patients no longer receiving face-to-face support | Mostly remained in her pre-COVID role with 1 or 2 days per week redeployed | Main anxiety about mental health of staff |

| Sandra | 41–45 | White British | Hospital based | 7 | High | Yes – ICU | Yes – psychologist | No | Just returned to pre-COVID role after redeployment | She felt anxious and exhausted | She is back to her ICU outreach work | Stressed as she felt that her work had no impact |

| Helen | 46–50 | White British | Midwife unit | 7 | Mid | No | No | No | Continued in her pre-COVID role | Stressed regarding protocols and procedures which felt stressful | Continued in her pre-COIVD role | Stressed regarding procedures |

| Sue | 51–55 | White British | community hospital | 8a | High | No | No | No | Continued in her pre-COVID role | Distressed regarding relatives not visiting | Continued in her pre-COVID role | Felt angry and stressed |

| Saffron | 51–55 | White British | Hospital based | 8c | Low | Yes – some days in ICU | No | No | Mostly remained in pre-COVID role | Found redeploying staff stressful | Continued in her pre-COVID role | She worked constantly during pandemic and felt exhausted |

| Lara | 56–60 | White British | Bank staff in I.C.U. | 5 | Low | No | No | No | Worked as regular bank staff in ICU | She felt proud that she was doing her bit. | Continued to work as regular bank staff in ICU | She felt isolated and anxious, poor staffing was a massive issue |

| Lizzy | 56–60 | Mixed white & Asian | Community | 5 | High | No | Apps, yoga, counselling | Yes | Remained in pre-COVID role | Very anxious; pressured to work when wanted to shield on health grounds | No second interview | No second interview |

| Julia | 56–60 | White British | Mental Health nurse | 6 | High | Yes –MH centre | No | No | Returned to pre-COVID role | Stressed. Took on work that she did not feel trained to do | Returned to pre-COVID role Service was being reconfigured | Anxious. Her manager left and she felt unsupported |

| Amie | 56–60 | Mixed white & Asian | Manager in the community | 8b | Low | No | No | No | Remained in pre-COVID role | Stressed; numbers of deaths, PPE shortages bullying | Working in her pre-COVID role | Felt unsupported and bullied by her external managers |

| Louise | 46–50 | White British | Research nurse | 8b | Low | Yes –red & green wardsb | No | No | Returned to pre-COVID role | Witnessed distressing / traumatising events | Returned to her pre-COVID role | Stressed, declined further redeployment |

In the UK nurses have standardised grading with band 5 the entry level for registered nurses and band 6 for many registered midwives. Nurses who work at higher grades have achieved a higher level of seniority and greater pay. Participant's Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) scores taken from participant's responses in the ICON study, were used in the sampling criteria so were varied.

Green zones or wards were for COVID free patients and red zones or wards for COVID positive patients.

2.6. Rigour and ethical approval

We have reported important aspects of the study (research team, methods, context, findings, analysis and interpretation) and have provided an audit trail to allow judgement of trustworthiness. We have completed the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) (Tong et al., 2007) checklist for explicit and comprehensive reporting. Ethical approval was received from the University of Surrey ethical governance committee (FHMS 19–20 078 EGA CVD-19).

3. Results

3.1. Participants

Our 27 participants represented a range of geographical areas, ages, grades, professional experiences, and pandemic experiences (Table 2). All the participants were female, except for one, Peter. Nineteen were redeployed during the first wave of the pandemic either to Intensive care Units (ICU) (n = 9) or other COVID-19 ‘hotspot’ areas (n = 10). Four of these nurses were redeployed again in wave 2 of the pandemic. In this context being ‘redeployed’ means being assigned to perform a role in a new setting or area, (usually COVID-19 wards or intensive care units) during the pandemic, roles which are different to the one the nurses were usually employed to work in. Table 2 also details changes between interviews 1 and 2.

3.2. Findings

Following data analysis four themes were identified as outlined in Table 3

Table 3.

Can this table please be moved up - immediately after table 2 please- it is an intorduction to the themes in the findings yet comes half way through the findings section in the PDF proof. Thanks

| Theme | Sub themes | |

|---|---|---|

| (i) | ‘Deathscapes’ and impoverished care | Increased patient death; impoverished care; work left undone; Moral distress due to care delivery challenges. |

| (ii) | Systemic challenges and self-preservation | insufficient staff; insufficient training; speaking up and self-preservation; PPE challenges and frustrations. |

| (iii) | Emotional exhaustion | survival mode, burnout, compassion fatigue; intention to leave |

| (iv) | (Un)helpful support | accessing support, not talking to friends and family, staff networks and stigma |

3.2.1. ‘Deathscapes’ and impoverished care

3.2.1.1. Increased patient death

COVID-19 brought about a change in patient cohorts for most of our interviewees with many nurses unused to seeing so many critically ill patients and deaths. We use the term ‘deathscapes’ to conceptualise the environments these nurses worked in during the COVID-19 peaks, where patient turn-over is marked by high mortality rates (Maddrell and Sidaway, 2016; Thompson, 2012) but also where the effects of clinical input are limited and care was task orientated (Rowland, 2014). Most of the nurses we spoke to reflected on the increase in deaths:

Three of my patients died [one night], and one of them was younger than my mum and only eight years older than me, it was just horrible. And you go back the next day and you're just like, “What fresh hell am I in for now?”

Laura, redeployed ICU, interview 1

We were verifying eight deaths a night, that was unprecedented, you know, and that went on, it was just these massive amount of deaths.

Mia, community nurse, interview 1

For those who had their second interviews during a time of widespread local COVID-19 cases, high death rates ensued, but with a notable difference in the age of patients:

Its traumatising, you know, the things that you see and everybody is really sick, (…) a lot of people are young. Everybody has the same disease (…) there's just so much death.

Ellie, redeployed ICU, interview 2

Nurses who normally work in ‘deathscapes’, such as end of life care or ICU, may construct defence mechanisms, such as concentrating on one area of the patient's body, or organisational directives, to minimise the emotional impact of patient deaths (Mackintosh, 2007; Rowland, 2021). However, many of the nurses we spoke to were redeployed and unaccustomed to working with so many critically ill patients where death occurred frequently meaning that defence mechanisms were less developed, as we can see from Ellie's description of her experiences as ‘traumatising’. Repeated exposure to traumatic and distressing events without sufficient psychological preparation has been found to have a cumulative effect on nurses’ mental health making them vulnerable to post-traumatic stress (PTSD) (Kinman et al., 2020). Individuals with PTSD often re-live the traumatic event through nightmares and flashbacks, and may experience feelings of isolation, irritability and guilt.

3.2.1.2. Impoverished care

Nursing literature frequently alludes to the moral obligation for nurses to provide compassionate care (Maben et al., 2010). Patients trust that the goodwill and competence of healthcare professionals will ensure that high quality, or at least appropriate, care is provided (Baier, 1986; Peter, 2021). We use the term impoverished to mean diminished or depleted care or care made weaker or worse in quality as a result of the extreme conditions nurses’ encountered in the pandemic. In the early stages of the pandemic, many of the nurses we spoke to reported that the overwhelming demand and the sheer busyness of their work environments meant that their normal high standards of care were not being met:

One thing I did struggle with in the beginning was we were so busy, and people were so sick that some of the (not even) basic care (…) didn't get done (…) it upset me when I couldn't get someone to come and give me a hand to move someone who'd been incontinent or something.

Sherie, redeployed non-ICU, interview 1

Things like basic nursing care was out of the window. We had so many patients with grade 4 pressure ulcers, one so bad that actually he's still being seen, because he wasn't turned, because no-one had any time to turn […] and you felt, I kept people alive today, but I didn't care for them, I didn't nurse them.

Laura, redeployed ICU, interview 1

The delivery of nursing care during the first wave of the pandemic was highly altered in comparison to usual care delivery with essential but intimate care, often considered the essence of nursing (Maben et al., 2010), almost impossible to perform. Constraints, such as an excessive workload or a lack of resources, led some of our interviewees to suffer from moral distress, as increased workload and system enforced changes as a result of COVID-19 prevented them from providing the quality of care they wished to provide (Rushton, 2017; Morley et al., 2019).

3.2.1.3. Moral distress due to care delivery challenges

Moral distress has been defined as occurring when healthcare professionals are prevented from providing the quality of care they feel they should be providing due to constraints such as an excessive workload or a lack of resources (Rushton, 2017). For some of the nurses we spoke to, the care landscape during the first wave of COVID-19, was very challenging with patients being treated differently with care quality being poor and impoverished compared to usual care:

I was starting to realise (…) and [ask] “Why is this guy not being treated? Why is his fracture not being treated?” (…) we supported a lady who had COVID-19. She was recovering from it, and she had a fall (…) cracked her head, really quite a serious head injury. We sent her off to the local acute hospital, they sent her straight back, didn't even scan her, just sent her straight back. Didn't want to know, didn't want her there.

Gaby, redeployed non-ICU, interview 1

For Gaby, the lack of compassionate care, along with her perception of people not being treated and placed on an end of life pathway too readily (a subject Gaby talked at length about in her first interview) and doctors refusing to get close to patients (due to infection concerns), led her to comment in her second interview that she was ‘embarrassed’ about the care her patients had received whilst she was redeployed. Their treatment was greatly at odds with her nursing values which entailed always going ‘the extra mile’ (Gaby, interview2). Therefore, the distress Gaby described regarding the treatment her patients received can be viewed as moral in nature. During her second interview Gaby talked about her hope that relatives may begin to question patient deaths during the pandemic with subsequent investigations being launched. We found that for nurses who were redeployed, their care for patients during the pandemic was not the only cause of their anxiety.

3.2.1.4. Work left undone

For the nurses who were redeployed, or those whose normal services had reduced or closed, many voiced their concerns in their first interviews about patients they had left behind, who they would normally be able to assist. This sense of anxiety about what had happened to patients that they were not physically able to check on created residual guilt and anxiety:

I had nurses telling me that worked in the community that they were told to cleanse, and use that word, ‘cleanse their caseload’ of people. And it was… it was always that underlying fear of what are we going to find when this is over? (…) We're starting to see that, people that deteriorated and become far more psychotic than I've seen in 20 years (…) I found all of that really distressing because it feels like you're just completely powerless for making a difference or an impact. Like watching a car crash in slow motion.

Catherine, Mental Health nurse, interview 1

So, I had a couple of days to close my caseload […] and I had a mum who had just lost her baby at four weeks. And I had seen her in the street and she'd got the baby's ashes under the pram, and I said to her, “I'll come and see you”, and she was desperate for it, and I couldn't go, couldn't even get hold her of her to tell her I couldn't go.

Gaby, redeployed non-ICU, interview 1

The phrase ‘cleanse their caseload’ evokes troubling discourses around war and genocide and suggests a lack of compassion and care for patients or clients about to lose access to care. Such unprecedented times left managers with few alternatives but to streamline services and make staff available for the COVID-19 pandemic at short notice and often in an urgent panic. The moral distress caused by, in Gaby's case, being physically removed from her caseload due to redeployment, and in Catherine's case, having most of her service close or transitioning to a remotely operated mental health service, is evident. The external constraints placed upon these nurses left them unable to perform what they considered to be their moral duty to care for their patients.

3.3. Systemic challenges and self-preservation

3.3.1. Insufficient staff

In accordance with other literature regarding the pandemic (e.g. Ustun, 2021), the nurses we spoke to reported extra pressures due to shortages of suitably qualified staff:

There were six patients, and I was the only staff with ICU experience and I was in charge (…) I was looking after all six [patients] and then I had a cardiac arrest at the end of the shift where my patient died (…) It wasn't uncommon that you'd be the only person with ICU experience for a lot more than four patients (…) My worst shift, I had four patients on my own, four intubated patients on my own, standards say you should have one-to-one.

Laura, interview 1, redeployed ICU, interview1

Being in an unfamiliar environment or care system with concerns about lack of organisational support with a heavy workload can also be viewed as contributing to stress during the pandemic. These stressful aspects of working during the pandemic were not only present during the first wave of COVID-19 in the UK. During their second interviews (in second wave of COVID-19) many nurses described stressful staff shortages:

A fortnight ago we were short-staffed, you know? They'd promised us that the nurse in charge of each pod wouldn't have a patient and we'd (….) have somebody else to help out, you know? An auxiliary. Well, that's gone by the board, purely because we're so short-staffed they can't manage it. And it was really hard.

Lara, ICU bank staff, interview 2

During Lara's second interview she referred to high numbers of staff absences due to sickness caused by COVID-19 and stress that her hospital was experiencing, and this was something that most of our nurses reported experiencing during the second wave

3.3.2. Insufficient training, speaking up and self-preservation

The majority of the nurses who were redeployed in the first wave described feeling under pressure due to the lack of training they had received. For example, Isabella, an experienced nurse, redeployed to ICU, described asking a manager for help. She felt unable to undertake the task she was assigned to do because of her manager's ‘dismissive’ answer:

I haven't done that [ICU work] for 20 years, (…) she was so dismissive and I've got to ask her again and she was dismissive again I thought I'm just not going to go there, I'm just going to leave it (…) I know you're stressed but I've asked you how to do something safely and you've not given me [any information about] how to do it safely so I'm not going to do it because I think I'll do the wrong thing.

Isabella, redeployed ICU, interview1

As a redeployed nurse Isabella did not want to put herself in a position where she could have been blamed for doing the ‘wrong thing’. This suggests a lack of trust between existing and redeployed nurses which other data sources confirmed. In her second interview, Isabella reflected at length on the lack of autonomy she experienced when redeployed. Avoiding undertaking tasks that she did not feel prepared for, helped her regain some autonomy in a situation that felt very out of her control. When nurses were forced to carry out tasks for which they felt insufficiently trained, they experienced distress that their ‘PIN’ (registration personal identification number) may be endangered. Trying to speak up or raise concerns felt difficult as such concerns seemed to fall on deaf ears or marked them out as a troublemaker. This left nurses in an invidious position as many described raising concerns as acts of ‘moral duty’ to help ensure the best care for patients:

Unless people do speak up and say what problems, our management aren't going to know because they're not coming near the patients. They're sitting in their little ivory towers (…) I think you've actually got a moral duty, a professional duty as well to speak out. But it doesn't win you any favours.

Lara, ICU bank staff, interview2

In both her interviews, Lara's description of her managers as ‘totally invisible’ was repeated by many, but not all, interviewees, some of whom complained about managers and doctors not entering wards or GPs verifying deaths via video calls, due to contagion fears. Nurses described ‘shouting into the ether’ when raising concerns illuminating the powerlessness they felt during the pandemic. For some of the nurses we spoke to, PPE became the issue over which they felt compelled to raise concerns to managers. Nurses’ attitudes towards PPE are explored below.

3.3.3. Personal protective equipment (PPE) challenges and frustrations

Mistrust regarding the effectiveness of PPE was reported but some nurses who worked in ICU reported feeling safer, precisely because they worked in a ‘red’ (COVID-19) setting and therefore had the full complement of PPE. Working in a red setting meant that there was no ambiguity about whether patients may or may not have had COVID-19, all the nurses knew the status of their patient's which led them to feel safer:

The red (…) with COVID patients (..) you've got the highest level of mask on, the FFP3, scrubs, a full-length gown on top of that, two pairs of gloves, a visor and a hat. And then if you go near the patients, then you put another full-length gown on and a pinny on top of that, and possibly a third pair of gloves. So, I do feel really safe in that (…) But on the amber side (with) ordinary patients (…) you're just wearing your scrubs and just one of the surgical masks which aren't tight fitting and they, they would allow bugs to get through….

Lara, ICU bank staff, interview 1

Therefore, when allocated appropriately, PPE contributed to feelings of safety and wellbeing. However, the shortages of PPE that the UK NHS experienced during the first wave of the pandemic were mentioned by all nurses we spoke to. Sandra, did not experience a shortage of PPE herself but reflected on how a reduction in the level of PPE provided for a group of colleagues made her feel:

I can remember going to the wards one day and they were in full PPE looking after COVID patients on the ward, and the next day going on there and all being told to change to surgical masks, and I did feel really quite angry actually at the time, thinking that we were letting them down, to have given them full PPE and then take it away, you could see their fear and it morally didn't sit right.

Sandra, ICU, interview 1

For Sandra, removing full PPE from her colleagues was experienced as moral distress and involved anger, frustration and powerlessness. Our research accords with other studies (Lapum et al., 2020) which indicate distress was increased by mistrust in Governmental advice about levels of protection offered and requirement in different clinical situations. At the beginning of the first wave of the pandemic, our interviewees reported PPE becoming a site of conflict as different departments or services fought over scarce supplies. This seemed especially pronounced for community services who experienced difficulties accessing the required amounts of PPE. In her second interview Sue reflected on how upset that she was that her community service appeared to not be a priority in terms of PPE:

What little PPE they had, I might have alluded to before, it all went to the Acute Trust, not us.

Sue, community nurse, interview 2

This prioritisation of resources away from community contexts was felt keenly by all the community nurses we interviewed. By not making nurses’ health and safety a priority through disregarding procedures such as mask FIT tests, which many of our interviewees mentioned, or prioritising ICU nurses PPE requirements over nurses working in other clinical areas, the message was sent that ‘some lives appear to matter less’ (Maben and Bridges, 2020: 2743). Recent literature has linked a lack of PPE to low job morale, increase in COVID-19 infection rates, lack of motivation and absenteeism (Ustun, 2021). We now turn to explore the levels of exhaustion that many nurses reported.

3.4. Emotional exhaustion

The majority of the nurses reported increases in psychological problems such as sleep disturbances, higher rates of alcohol consumption and increases in unhealthy food consumption, which are all widely acknowledged as short-term physical symptoms of stress (Kinman et al., 2020). This was particularly relevant for the redeployed staff who frequently did not know where they would be based and had a variable daily workload.

3.4.1. Survival mode, burnout and compassion fatigue

Some of the nurses referred to operating ‘on autopilot’, as they coped with the chronic stress resulting from caring for COVID-19 patients and then having to get up to repeat the same actions the next day. The extra precautions the nurses took to prevent infecting their families with COVID-19, with many referring to showering at work or taking off their work clothes at the front door, became another thing to negotiate in their overwhelmingly busy schedules:

I felt like I was in survival mode, I'd come home, decontaminate in the porch, my family would go “how are you?” and I'd go “not crying”, they'd go “okay” and (…) I would get straight in the shower and I just would eat and go to bed and do it again, and be awake at 05.00 just kind of like thinking about it (…) so I think I just was on survival mode (…) and I was a bit shocked at how it affected me, I just thought what's the matter with me?

Isabella, redeployed ICU, interview 1

Nurses also described aspects of ‘burnout’ including emotional exhaustion, depersonalisation and a lack of effectiveness at work (Maslach and Jackson, 1986; Dall'Ora et al., 2020). Extreme exhaustion was mentioned by most of our interviewees and nurses described keeping going until ‘no longer needed’ at which point they would ‘fall apart’ (Tessa interview1). Others described how the experiences had taken their toll on their tolerance and on their own health:

One of my favourite phrases at the minute is, “I don't have any patience for patients at the minute” (…) and I've just got a bit of fatigue I think, I've got patient fatigue, ICU fatigue.

Laura, redeployed ICU, interview 1

She said, “You can't walk through water without getting wet”, and the little bits that you see and experience all day long will take its toll, (…) it's really helped put that into perspective, that actually you don't have a limitless supply (…) it does actually have a knock-on effect.

Sandra, ICU, interview 1

The image Sandra provided of the emotional toll of nursing under the duress of the pandemic, which she equated to walking through water, highlights the intense contact with patients, delivery of compassionate care, and emotional labour, involving both the performance of managed emotions to ease the fear and distress of their patients, whilst hiding other emotions expected of nurses (Hochschild, 2003; Kinman and Leggetter, 2016). Previous research has indicated that the performance of such emotional labour can threaten nurses’ wellbeing (Donoso et al., 2015). Laura's expression of ‘not having patience for patients’, and Sandra's reduced level of empathy, can be viewed as depersonalisation, where individuals develop an indifferent or distant attitude (Kilroy et al., 2020). This, along with emotional exhaustion, a state where one is emotionally and physically drained at work, are two of the core symptoms of burnout (Kilroy et al., 2020). Compassion fatigue has been conceptualised as arising from failed rescue-caretaking attempts (Valent, 2002) and is associated with low morale, social isolation, absenteeism and ultimately leaving the profession (Ustun, 2021). Nurses’ expressed intentions to leave their profession are now explored below.

3.4.2. Intention to leave

At second interview in December 2020/January 2021, some of the nurses recounted being asked by managers to be redeployed for a second time and actively declining for the ‘sake of my own personal and mental health’ (Isabella, second interview). The majority related stories of colleagues or friends who had now left the profession or were about to do so. Peter, who left his role after the first wave, and noted five colleague resignations, attributed the exodus to the lack of willingness of managers to embrace systematic changes:

[Managers] wanted you to prioritise going and telling people off for not wearing PPE, basically it became just a really unpleasant, untenable role, basically. And I do feel very annoyed that I've had to leave (…). We need to stop telling people off for things (…) the easiest option was to just move on.

Peter, redeployed non ICU, interview 2

A majority of the older nurses had recently re-evaluated their retirement options:

I've been looking a lot into my retirement and stuff (…) I'm not enjoying nursing.

Isabella, redeployed ICU, interview 2

The midwives that are coming up to retiring are definitely retiring, whereas before I think some of them would have stopped and stayed.

Helen, midwife unit, interview 2

The nurses we spoke to, who were over 45, expressed a wish to retire as soon as financially viable which supports Halter et al.’s (2017) assertion that job dissatisfaction, stress and burnout symptoms nurses experienced due to the pandemic increased their intention to leave (Halter et al., 2017).

3.5. (Un)helpful support

3.5.1. Not being able to talk about their experiences to friends or family

In contrast to other research (e.g. White, 2021), which highlighted family as a helpful support base, those we spoke to were unanimous in sometimes feeling unable to talk about their experiences with their partners, families or non-medically trained friends due to not wanting to worry them about their own safety, or trouble them with the distressing reality of COVID-19:

I didn't want to worry them (…) My kids love a gruesome orthopaedic injury that I might show them at home, but this was different, you know? So, I just didn't feel that it was fair to burden them with that, because then they're worrying for me as well.

Jo, redeployed ICU, interview 1

I didn't tell them for the, about the first six weeks I was working on a COVID-19 ward, which is terrible, but I chose not to (…) I thought it would make them feel much more anxious.

Alison, Mental Health nurse, interview 1

By withholding such information, these nurses were able to regulate their families’ emotional responses, although this may have increased their own emotional ‘burden’. Due to not sharing stories with family and friends, they instead described placing high value on sharing with like-minded colleagues who had been through the same experiences. This is explored below.

3.5.2. Staff networks as support

For most, the importance of staff networks, either virtual or face-to-face, had increased, and many described the support that they received, and were able to give to colleagues, as the main positive aspect of the pandemic. Many referred to an increased sense of support or ‘camaraderie’ (Mia, interview1):

At work I didn't [feel isolated] because everyone's here. And I've got two colleagues that I share the office with that, you know, if I was having a bad day I'd just say, and they would talk me through it.

Jo, redeployed ICU, interview 1

All nurses emphasised the benefits of being able to talk freely about their experiences and feelings with those who understood what they had gone through, i.e. co-workers which supports previous research (Kinman and Leggetter, 2016). For those who did not work in supportive teams, for example, Isabella, WhatsApp groups were established with like-minded individuals or others who had been redeployed to provide support:

I set up a little support group for the redeployed nurses (…) we called it the ‘redeployed survivors’ group’ where we were able to offload how we felt on a shift (…) it validated what you were feeling, that really helped.

Isabella, redeployed ICU, interview 1

For our participants, no barriers existed to accessing WhatsApp or Facebook groups as they were instantly available and could be accessed anonymously. They operated as a source of validation of their feelings, as Isabella suggests above. When members were feeling overwhelmed a colleague would listen, respond with supportive (and instant) messages and where appropriate direct them to other resources or services for support. Unlike these informal support groups, those offered by the NHS or their hospital employers tended to be characterised by the participants in terms of barriers to access, as explored below.

3.5.3. Accessing support and stigma

For the majority during the first wave, the support interventions that employers had made available, such as ‘wobble rooms’, counselling or psychologist sessions, were described as unappealing and mostly unused due to barriers such as time constraints. There was also some desire to try to forget the trauma of work while not on duty, and some sense that if they ‘took the lid off’ in the early days they would not be able to carry on and function:

Part of the reason is I think because initially [you're] so fatigued by everything that's going on, the last thing you want to do is talk to anybody else about it. Because for me it was a case of going home and trying to sort of… to leave it all behind at work (..) at the moment there's not enough time to process everything.

Sue, rehabilitation centre, interview 2

Others wanted to rest in their time away from work:

Everything would be on your day off and [people] they just wanted to be at home and catch up on cooking, cleaning (…), gardening, or just do nothing. So (…) you sort of needed your rest and to not think of work on your days off.

Sandra, redeployed ICU, interview 1

Whilst others felt that the national offer from the NHS of access to external counselling and support Apps was not what was needed:

I'd rather talk to my colleagues in ICU, who were there on the day six people died on me, than talk to a professional who I've never met or who doesn't really know what it was like.

Laura, redeployed ICU, interview 2

Stigma may also have been a factor in some not accessing counselling during the first wave. Previous literature (e.g. Lee et al., 2020) has highlighted stigma as one of the major barriers to seeking treatment via mental healthcare services for healthcare staff and could impede individuals from seeking support. Other participants referred overtly to the notion that nurses seeking counselling would be viewed as a ‘sign of weakness’:

[Counselling is] just like almost a sign of weakness I feel, (…) I think there's like an attitude in the NHS that you have to be strong and not show weakness and like not many people show that much emotion

Sarah, redeployed ICU, interview 1

Thus, Sarah hints at the stigmatisation regarding mental health in the NHS. Only two nurses at interview 1 had accessed counselling support. However, by the time our second interviews were conducted (5–6 months later) many more had actively sought out counselling predominantly through anonymous sources such as charities or Trade Unions. This exhibits a lack of trust in the confidentiality of resources linked to employers:

[I didn't want to] divulge information to my manager to then get referred, and I'd feel like (…) I was trying to ask for special treatment. (…) We've all been through the same thing, and I wouldn't want, like, to be judged on (…) me needing counselling but other people not needing it.

Sarah, interview 2

Sarah wanted to avoid any perceived stigmatisation or impact on her career and feared being judged by her colleagues but felt she had benefitted greatly from the counselling, frequently practicing the strategies suggested. Many nurses reported the importance of self-care through exercise, walking or time outside in nature as very beneficial. In this respect many were very self-reliant and did not take up the online support available in the Government's national NHS well-being offer. Some were actually unaware of the national offer, and as reported above, others actively rejected the mindfulness apps and other support in favour of the benefits of deriving support from self-developed social groups with others who had experienced similar processes and events to themselves.

4. Discussion

This study explored the impact of COVID-19 on frontline nurses’ emotional and psychosocial wellbeing. The nurses’ narratives conveyed the anxiety, frustration, guilt and inner turmoil they experienced, and continue to do so, as the trajectory of the pandemic progressed. Our findings accord with the recent British Academy (2021a) which states that there is ‘already evidence that the toll on [nurses’] mental wellbeing may also be considerable, with the potential for long-term scarring’. The terms moral distress, compassion fatigue, burnout and PTSD (Morley et al., 2019; Maslach and Jackson, 1986; Kinman et al., 2020, West and Bailey, 2020; Ustun, 2021) can be used to describe many of the emotional states conveyed by our interviewees. In terms of moral distress our work aligns with Liberati et al. (2021) research with mental health nurses during COVID-19. The majority of our participants experienced moral distress (Morley et al., 2019) as deeply traumatising due to compromises in terms of time and or resources or external constraints, making their care delivery less compassionate (Maben et al., 2012), and with some describing daily involvement in ‘deathscapes’ where task orientated behaviour was high, treatment options were limited and extremely high death rates were encountered (Maddrell and Sidaway, 2016; Rowland, 2014).

In the first wave, distress was caused by suboptimal PPE access, and similar to Lapum et al. (2020) research with nurses in Canada during COVID-19, meant that the scramble to access scarce PPE further exacerbated existing divisions between community and acute services. PPE supplies did however become less problematic during the second wave. Although some nurses viewed ‘speaking out’ as part of their moral duty towards their patients, many were more pragmatic, accepting limitations that existed during the pandemic. This acceptance became more prevalent as the pandemic progressed, which is unsurprising considering the complexities which surround ‘whistle-blowing’ with the risk of victimisation and ostracization and with the ongoing risk of organisations remaining deaf to staff raising concerns when things go wrong (Jones and Kelly, 2014).

There is a large body of evidence that supports the benefit of short-term psychological support which can be most effective when tailored to the individual (Mansell et al., 2020; Ustun, 2021; Fox et al., 2012) and which accentuates the value of social and peer support from colleagues to protect healthcare workers from the negative impact of emotional demands (e.g. Kinman & Leggetter, 2019). Our data highlights the importance of this form of support (face to face or virtually via WhatsApp or other social media groups) during the pandemic. In self-developed social media support networks, the nurses felt empowered to share their experiences with colleagues who had ‘been through the same thing’. In this respect our research disagrees with work such as Liberati et al. (2021) who argued informal social supports may be especially difficult to replace or replicate in pandemic conditions. Due to nurses’ reticence to approach managers about their problems, we advocate that short-term support needs moving outside of employers, into an autonomous, independent body which does not require referrals from managers to access. Our data further highlight the need for future research into interventions which are participatory in nature, focusing on cohorts of nurses who can use their ‘inside’ knowledge to act as ‘experts by experience’.

Previous research supports disclosure of mental health problems and a ‘failure to cope’ as stigmatising among healthcare staff (Lee et al., 2020; Ipsos Mori, 2009). Discourses and cultures around mental health stigma, which values nurses’ ability to cope, leave many healthcare workers not wishing to admit to poor mental health within the NHS (Kinman et al., 2020; Lee et al., 2020). Similar to Dykes et al.’s (2021) UK-based survey research, we found that nurses did not access support offered by employers during the pandemic (Dykes et al., 2021). Our data revealed a marked hesitancy to disclose ‘real’ problems to managers due to stigma or worries about being judged by colleagues suggesting in some settings it remains psychologically unsafe for staff to disclose mental health challenges, due to a perceived impact on their career. Some nurses in our study did report difficulties in revealing the extent to which they were struggling and seemed to delay accessing support until they deemed it absolutely necessary when they chose to access it via anonymous sources such as charities or Trades Unions.

5. Strengths and limitations

Our study has many strengths such as the longitudinal and in-depth study design and the use of narratives to gain participants’ perspectives and to place these into a biographical context. Participants frequently disclosed that they had not spoken to anyone else and reported that they found the process to be of great psychological benefit (for further details please see Conolly et al., 2022). Limitations include not reaching our stated sampling quotas for ethnic minorities, midwives, social care, or student groups.

6. Conclusion

Nurses reported being deeply affected by what they have seen and experienced and being forever-altered. It is clear that for these nurses, the impact of COVID-19 is felt at a deeply personal level and may persist. Among this cohort, many encountered extreme busyness in the services they returned to. While some mental health impacts may be short-term responses to the crisis, others have the potential for ‘long-term scarring in different groups’ (British Academy, 2021a: 43). Worldwide, the International Labour Organisation (ILO) and World Health Organisation (WHO) have both asked countries to formulate a new set of safety guidelines for health workers suffering from the impact of Covid pandemic (ILO, 2022). The guide produced by WHO and ILO emphasizes that continuous investment, training, monitoring and collaboration are essential for sustaining progress in implementing the suggested programmes which are to be actioned by governments, employers, workers and occupational health services. Within the UK, the British Academy has stated that “There is an urgent need to restore nurse well-being and develop a national COVID-19 nursing workforce recovery strategy focussing on valuing the nursing workforce and nurse retention” (British Academy 2021b:15).

This study has revealed the importance of providing support to nurses during and after the pandemic. We argue that Governmental provision, enshrined in policy and adequately resourced, should be provided to support nurses during and after the pandemic to ensure the future of nursing and the security of society. It is imperative that we address the likely mental health and linked retention crisis in the nursing workforce by providing the right support at the right time. We need to tackle stigma to create a psychologically safe working environment and listen well to what nurses need to recover. We have a duty as a society to take care of frontline staff who have experienced extreme stress and distress during this pandemic. It is also critical to avoid a mass nursing exodus, and any further deepening of recent UK and global workforce shortages, being exacerbated by this or future pandemics.

Authors' contributions

Jill Maben, Keith Couper, Ruth Harris, Daniel Kelly and Bridie Kent participated in the conception and initial design of the project and with Ruth Abrams, Anna Conolly and Emma Rowlands developed the data collection tools including the interview schedule. Jill Maben, Ruth Harris, Daniel Kelly, Bridie Kent, Ruth Abrams and Anna Conolly collected the data. Anna Conolly, Jill Maben and Emma Rowlands undertook the qualitative interview analysis. All authors were involved in the interpretation of the results. Anna Conolly and Jill Maben drafted the manuscript in dialogue with all authors, who significantly contributed sections, substantively revised drafts and approved the final manuscript.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported by the Burdett Trust for Nursing and the Florence Nightingale Foundation. The funders had no involvement in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Acknowledgments

The Impact of Covid on Nurses (ICON) survey study research group supported acquisition of funding and access to sample via the survey. This group comprises: Couper, K., Murrells, T., Sanders, J., Anderson, J., Blake, H., Kelly, D., Kent, B., Maben, J., Rafferty, A., Taylor, R., and Harris, R.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2022.104242.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- Ali S., Maguire S., Marks E., Doyle M., Sheehy C. Psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on healthcare workers at acute hospital settings in the South-East of Ireland: an observational cohort multicentre study. BMJ Open. 2021;10(12) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-042930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baier A. Trust and antitrust. Ethics. 1986;96:231–260. [Google Scholar]

- British Academy . Understanding the Long-Term Societal Impacts of COVID-19. The British Academy; London: 2021. THE COVID decade. [Google Scholar]

- British Academy . The British Academy, London; 2021. The COVID Decade Addressing the Long Term Societal Impacts of COVID 19. [Google Scholar]

- Burr V. Social Constructionism. Routledge; 2015. London. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K. Sage; London: 2006. Constructing Grounded Theory. [Google Scholar]

- Conolly A., Maben J., Abrams R., Rowland E., Harris R., Kelly D., Kent B., Couper K. Researching distressing topics ethically: reflections on interviewing nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2022 Under review. [Google Scholar]

- Couper K., Murrells T., Sanders J., Anderson J., Blake H., Kelly D., Kent B., Maben J., Rafferty A., Taylor R., Harris R. The impact of COVID-19 on the wellbeing of the UK nursing and midwifery workforce during the first pandemic wave: a longitudinal survey study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2022;127 doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2022.104242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dall'Ora C., Ball J., Reinius M., Griffiths P. Burnout in nursing: a theoretical review. Hum. Resour. Health. 2020;18(1) doi: 10.1186/s12960-020-00469-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis M., Cher B., Friese C., Bynum P. Association of US nurse and physician occupation with risk of suicide. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021 doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2021.0154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donoso L.M., Demerouti E., Hernández E.G., Moreno-Jiménez B., Cobo I.C. Positive benefits of caring on nurses’ motivation and well-being: a diary study about the role of emotional regulation abilities at work. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2015;52:804–816. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2015.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dykes N., Johnson O., Bamford P. Assessing the psychological impact of COVID-19 on intensive care workers: a single-centre cross-sectional UK-based study. J. Intens. Care Soc. 2021 doi: 10.1177/1751143720983182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott V. Thinking about the coding process in qualitative data analysis. Qualit. Rep. 2018;23(11):2850–2861. https://nsuworks.nova.edu/tqr/vol23/iss11/14 [Google Scholar]

- Fox J., Desai M., Britten K., Lucas G., Luneau R., Rosenthal M. Mental-health conditions, barriers to care, and productivity loss among officers in an urban police department. Conn. Med. 2012;76(9):525–531. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg N., Weston D., Hall C., Caulfield T., Williamson C., Fong K. Mental health of staff working in intensive care during Covid-19. Occup. Med. (Chic Ill) 2021;71(2) doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqaa220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenhalgh T., Russell J., Swinglehurst D. Narrative methods in quality improvement research. Qual. Saf. Health Care. 2005;14:443–449. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2005.014712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halter M., Boiko O., Pelone F., Beighton C., Harris R., Gale J., Gourlay S., Drennan V. The determinants and consequences of adult nursing staff turnover: a systematic review of systematic reviews. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2017 doi: 10.1186/s12913-017-2707-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding J. Questioning the subject in biographical interviewing. Sociol. Res. Online. 2006;11(3) https://www.socresonline.org.uk/11/3/harding.html [Google Scholar]

- Hermanowicz J. The Longitudinal Qualitative Interview. Qual. Sociol. 2013;36(2) doi: 10.1007/s11133-013-9247-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hochschild A.R. University of California Press; Berkeley: 2003. The Managed Heart: Commercialization of Human Feeling. [Google Scholar]

- Hollway W., Jefferson T. Panic and perjury: a psychosocial exploration of agency. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2005;44:147–163. doi: 10.1348/014466604X18983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollway W., Jefferson T. 2nd edition. Sage; London: 2013. Doing Qualitative Research Differently: Free association, Narrative and the Interview Method. [Google Scholar]

- International Labour Organisation (ILO) 2022. New ILO/WHO guide urges greater safeguards to protect health workers, Occupational Safety and Health for Health workers Press Release 21 February 2022. https://www.ilo.org/global/about-the-ilo/newsroom/news/WCMS_837406/lang–en/index.htm

- Mori Ipsos. Fitness to practise the health of healthcare professionals. Occup. Health (Auckl) 2009 [Google Scholar]

- Jones A., Kelly D. Deafening Silence? Time to reconsider whether organisations are silent or deaf when things go wrong. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2014;23:709–713. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2013-002718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilroy S., Bosak J., Flood P., Peccei R. Time to recover: the moderating role of psychological detachment in the link between perceptions of high-involvement work practices and burnout. J. Bus. Res. 2020;108:52–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.10.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kinman G., Teoh, K. Harriss, A. 2020. The Mental Health and Wellbeing of Nurses and Midwives in the United Kingdom, available at: The Mental Health and Wellbeing of Nurses and Midwives in the United Kingdom FINAL.pdf(Shared)- Adobe Document Cloud Accessed on December 19th, 2020.

- Kinman G., Leggetter S. Emotional labour and wellbeing: what protects nurses? Heathcare. 2016;4(89) doi: 10.3390/healthcare4040089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai J., Ma S., Wang Y., Cai Z., Hu J., Wei N., Wu J. Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 9. AMA Netw. Open. 2020;3(3) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labrague L., de los Santos J. COVID-19 anxiety among front-line nurses: predictive role of organisational support, personal resilience and social support. J. Nurse Manag. 2020;28:1653–1661. doi: 10.1111/jonm.13121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapum J., Nguyen M., Fredericks S., Lai S., McShane J. Goodbye ... Through a Glass Door”: emotional experiences of working in COVID-19 acute care hospital environments. Can. J. Nurs. Res. 2020;0(0):1–11. doi: 10.1177/0844562120982420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee E., Jeong Y., Yi J. Nurses’ attitudes toward psychiatric help for depression: the serial mediation effect of self-stigma and depression on public stigma and attitudes toward psychiatric help. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020;17:5073. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17145073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Liberati E., Willars J., Richards N., Scott D., Boydell N., Parker J., Pinfold V., Martin G., Dixon-Woods M. Experiences of NHS mental healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: qualitative study. BMC Psychiatry. 2021 doi: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-301568/v1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maben J., Bridges J. COVID-19: supporting nurses’ psychological and mental health. J. Clin. Nurs. 2020;29:2742–2750. doi: 10.1111/jocn.15307. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/jocn.15307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maben J., Adams M., Peccei R., Murrells T., Robert G. Poppets and parcels': the links between staff experience of work and acutely ill older peoples' experience of hospital care. Int. J. Older People Nurs. 2012 doi: 10.1111/j.1748-3743.2012.00326.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maben J., Cornwell J., Sweeney K. In praise of compassion. J. Res. Nurs. 2010;15(1):9–13. doi: 10.1177/1744987109353689. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mackintosh C. Protecting the self: a descriptive qualitative exploration of how registered nurses cope with working in surgical areas. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2007;44(6):982–990. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2006.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maddrell A., Sidaway J.D. Ashgate; Farnham: 2016. Deathscapes’: Spaces for Death, Dying, Mourning and Rememberance. [Google Scholar]

- Malterud K., Siersma V.D., Guassora A.D. Sample size in qualitative interview studies: guided by information power. Qual. Health Res. 2016;26(13):1753–1760. doi: 10.1177/1049732315617444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansell W., Urmson R., Mansel L. The 4Ds of dealing with distress – distract, dilute, develop, and discover: an ultra-brief intervention for occupational and academic stress. Hypthesis Theory. 2020 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.611156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maslach C., Jackson S.E. 2nd Edition. Consulting Psychologists Press; Palo Alto, California: 1986. Maslach Burnout Inventory Manual. [Google Scholar]

- Mills J., Bonner A., Francis K. The development of constructivist grounded theory. Int. J. Qual. Methods. 2006;5(1) doi: 10.1177/160940690600500103. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mishler E.G. Harvard University Press; Cambridge: 1999. Storylines. Craftartists’ Narratives of Identity. [Google Scholar]

- Morley G., Bradbury-Jones C., Ives J. What is ‘moral distress’ in nursing? A feminist empirical bioethics study. Nurs. Ethics. 2019:1–18. doi: 10.1177/0969733019874492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller J. In: Doing Qualitative Research. 2nd ed. Crabtree BF, Miller WL, editors. Sage; London: 1999. Narrative approaches to qualitative research in primary care; pp. 221–238. [Google Scholar]

- NHS Health and Wellbeing 2009. London: DoH (Chair Dr S Boorman). http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20130107105354/http:/www.dh. gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_108 799 (accessed 6 January 2021)

- Ohta R., Matsuzaki Y., Itamochi S. Overcoming the challenge of COVID-19: a grounded theory approach to rural nurses' experiences. J. Gen. Fam. Med. 2020;22(3):1–7. doi: 10.1002/jgf2.410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Office for National Statistics (ONS) 2021. Coronavirus (COVID-19) - Office for National Statistics (ons.gov.uk). https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/conditionsanddiseases

- Peter E. In: Place and Professional Practice. Andrews G., Rowland E., Peter E., editors. Springer; Switzerland: 2021. Safe, ethical professionals? Trust and the representation of nurses, work and places in the context of neglectful and dangerous practice; pp. 115–131. [Google Scholar]

- Ramvi E. I am only a nurse: a biographical narrative study of a nurse's self-understanding and its implication for practice. BMC Nurs. 2015;14:23. doi: 10.1186/s12912-015-0073-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riessman C.K. Sage Publications; Newbury Park, CA, London & New Dehli: 1993. Narrative Analysis. [Google Scholar]

- Riessman C.K. In: Handbook of Interview Research. Gubrium J., Holstein J., editors. Sage; Newbury Park: 2002. Analysis of personal narratives; pp. 695–710. [Google Scholar]