Abstract

Anxiety is a prominent and debilitating symptom in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) patients. Carriers of APOE4, the greatest genetic risk factor for late-onset AD, may experience increased anxiety relative to carriers of other APOE genotypes. However, whether APOE4 genotype interacts with other AD risk factors to promote anxiety-like behaviors is less clear. Here, we used open field exploration to assess anxiety-like behavior in an EFAD mouse model of AD that expresses five familial AD mutations (5xFAD) and human APOE3 or APOE4. We first examined whether APOE4 genotype exacerbates anxiety-like exploratory behavior in the open field relative to APOE3 genotype in a sex-specific manner among six-month-old male and female E3FAD (APOE3+/+/5xFAD+/−) and E4FADs (APOE4+/+/5xFAD+/−). Next, we determined whether circulating ovarian hormone loss influences exploratory behavior in the open field among female E3FAD and E4FADs. APOE4 genotype was associated with decreased time in the center of the open field, particularly among female EFADs. Furthermore, ovariectomy (OVX) decreased time in the center of the open field among female E3FADs to levels similar to intact and OVXed E4FAD females. Our results suggest that APOE4 genotype increased anxiety-like behavior in the open field, and that ovarian hormones may protect against an anxiety-like phenotype in female E3FAD, but not E4FAD mice.

Keywords: apolipoprotein E, Alzheimer’s disease, ovariectomy, open field, anxiety

Introduction

Although memory dysfunction is the predominant behavioral hallmark of Alzheimer’s disease (AD), anxiety is a frequent comorbidity (Ferretti et al., 2001; Porter et al., 2003). Indeed, although the primary thrust of much AD research has been to uncover underpinnings of memory dysfunction, less is known about factors contributing to anxiety in AD patients. Anxiety disorders and AD disproportionately affect females relative to males (Altemus et al., 2014; Launer et al., 1999), and female sex exacerbates anxiety in AD patients (Tao et al., 2018). Women who underwent bilateral oophorectomy prior to menopause experience increased risk for AD (Rocca et al., 2007) and are more likely to experience anxiety symptoms (Rocca et al., 2008), suggesting that removal of estrogens negatively impacts multiple psychological realms. APOE4 genotype, the primary genetic risk factor for late-onset AD (Ertekin-Taner, 2007), has also been linked to increased anxiety in male and female AD patients (Michels et al., 2012). Although female sex, APOE4 genotype, and ovarian hormone loss have all been independently linked to increased anxiety in AD patients, these factors have not been examined in concert in mouse models of AD.

Interestingly, previous evaluations of anxiety-like behavior in rodent models of AD have yielded inconsistent and contradictory results. In some cases, transgenics including APP/PS1 and 5xFAD mice, exhibited decreased or equivalent anxiety-like behavior in the open field or elevated plus maze relative to wild-type controls (Arendash et al., 2001; Jawhar et al., 2012; Radde et al., 2006). By contrast, increased anxiety-like behavior has also been reported, often in the same tasks or animal model that reportedly exhibited decreased anxiety-like behavior in previous studies (Flanigan et al., 2014; Lippi et al., 2018; Sterniczuk et al., 2010). Discordant findings in investigations of anxiety-like behaviors underscore the need for additional attention to be paid to modeling anxiety-like behaviors in rodent models of AD and determining how risk factors like APOE genotype, sex, and ovarian hormone loss influence these behaviors within these models.

Consistent with the human literature, male and female mice expressing APOE4 exhibit increased anxiety-like behavior relative to APOE3 carriers (Robertson et al., 2005; Siegel et al., 2012). However, whether this between-genotype difference persists in model in which mice also develop AD-like pathology remains an important question. In addition, although female sex increases risk for anxiety and for AD in humans, few existing studies evaluate sex differences in anxiety-like behavior in mouse models of AD. Unfortunately, many studies that include both males and females do not segregate data by sex, which could inadvertently occlude observation of sex differences in anxiety-like behaviors in these models. Given the differential contributions of sex, as well as APOE3 and APOE4 genotypes, to anxiety in human patients (Michels et al., 2012; Tao et al., 2018), examining how these factors contribute to anxiety-like behavior against a background of AD pathology is a crucial step towards targeting anxiety-like symptomology in disease treatments. In the present study, exploration in an open field was used as a measure of anxiety-like behavior, as less time spent in the center of the open field is thought to indicate increased anxiety (Seibenhener and Wooten, 2015). Here, we used a mouse model of AD designed to model APOE-associated AD risk to test the hypotheses that APOE4 genotype exacerbates anxiety-like behavior in the open field relative to APOE3 genotype, and that ovarian hormone loss acts synergistically with APOE4 to exacerbate anxiety-like behavior in the open field.

Methods

Subjects

APOE-TR+/+/5xFAD+/− (EFAD) mice co-express five familial AD mutations (APP K670N/M671L + I716V + V717I and PS1 M146L + L286V) under control of the neuron-specific mouse Thy-1 promoter, and human APOE3 or APOE4 (Youmans et al., 2012). Experimental mice were homozygous for human APOE3 (E3FAD) or APOE4 (E4FAD). EFAD mice were bred, weaned, and genotyped for APOE and 5xFAD status at the University of Illinois Chicago, (UIC; Animal use protocol 17-066) prior to being shipped to the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee (UWM) at 2 months of age, where they were aged to 6 months before behavioral testing (UWM animal use protocol 19-20-03). Mice were housed in groups of 3-5 per cage (at both UIC and UWM for Experiment 1a) or singly housed (Experiment 1b) and maintained on a 12 hr light/dark cycle with ad libitum access to food and water for the duration of the study. Mice were handled for 30 s/day for three days prior to behavior. Protocols and procedures followed the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the UIC Animal Care Committee and UWM Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Surgery

Mice in Experiment 1 did not undergo surgical procedures. Two weeks prior to behavioral testing, female E3FAD and E4FAD mice in Experiment 2 underwent bilateral ovariectomy to eliminate ovarian hormones, and were also implanted with bilateral stainless steel cannulae into the dorsal hippocampus (DH) as described previously (Lewis et al., 2008) for subsequent experiments not reported here. During the procedure, mice were anesthetized with isofluorane (5% for induction, 2% for maintenance) in 100% oxygen. For analgesia, mice received carprofen MediGel 1 day before and 1 day after surgery, and received a subcutaneous injection of 5 mg/kg Rimadyl at the start of the surgical procedure.

Open Field (OF)

Data were collected in a 5-minute trial, during which mice explored a novel empty square arena (60 cm x 60 cm x 47 cm). The arena was illuminated by standing lights to approximately 75 lux. A luxometer was used before training to verify that the four corners of the OF were evenly illuminated and within 5 lux of each other. OF was used to measure general locomotor activity and time spent in the perimeter as an indicator of anxiety-like behavior (Prut and Belzung, 2003). The arena was divided into 16 squares via an automated grid system using ANYmaze software (San Diego Instruments), which was also used to record data. Time in the center squares of the arena, distance travelled, and speed were recorded. More time in the center was indicative of low anxiety levels, and higher values for distance and speed indicated increased activity (Bailey and Crawley, 2009).

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 9 software. For Experiment 1, differences were assessed using two-way ANOVAs with sex and genotype as between-subject variables. For Experiment 2, differences were assessed using two-way ANOVAs with genotype and gonadal status as between-subject variables. Because APOE4 genotype and female sex are associated with greater anxiety in humans (Michels et al., 2012; Tao et al., 2018), we hypothesized that female E4FADs would exhibit the most anxiety-like behavior followed by female E3FADs and male E4FADs, and then male E3FADs. Due to these specific predictions, significant main effects were followed by planned Tukey’s post hoc comparisons. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05 for all statistical tests. Trends were determined by p < 0.10. Effect sizes were calculated using η2.

Results

Experiment 1: APOE4 genotype increases anxiety-like behavior relative to APOE3 genotype

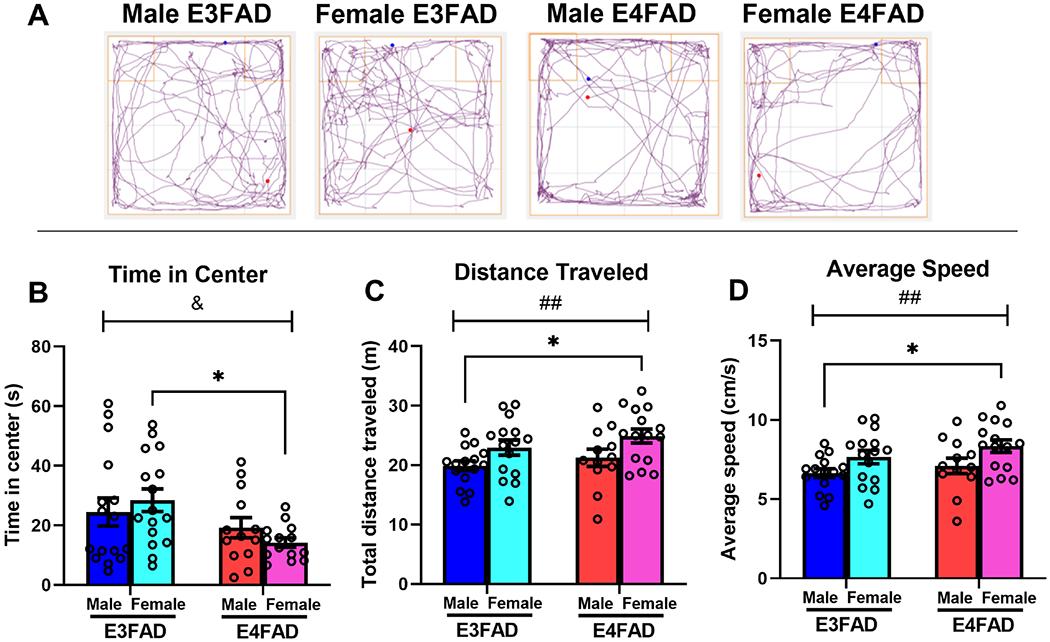

Given the prevalence of anxiety in AD patients (Ferretti et al., 2001; Porter et al., 2003), particularly APOE4 carriers (Michels et al., 2012), anxiety-like behaviors were measured in male and female E3FAD (n = 16, male E3FAD; n = 16, female E3FAD) and E4FAD mice (n = 13, male E4FAD; n = 14, female E4FAD) using the open field (OF).

E4FADs, regardless of sex, spent significantly less time in the center of the OF than E3FADs (Fig. 1B; genotype effect: F(1, 55) = 6.89, p = 0.01, η2 = 0.11). This effect was prominent in E4FAD females, such that female E4FADs spent significantly less time in the center than female E3FADs (p = 0.04). The main effect of sex (F(1,55) = 0.02, p = 0.89) and genotype x sex interaction (F(1,55) = 1.44, p = 0.24) were not significant.

Fig 1. E4FADs exhibit more anxiety-like behavior in the open field than E3FADs.

(A) Track plots illustrate representative patterns of movement in the open field. (B) E4FAD females spent less time in the center relative to E3FADs (&p < 0.05, main effect of genotype; * p < 0.05, female E4FADs vs female E3FADs). (C,D) Female E4FADs traveled further (##p < 0.01, main effect of sex; *p < 0.05, female E4FAD vs male E3FAD) and faster on average (##p < 0.01, main effect of sex; *p < 0.05, female E4FAD vs male E3FAD) than male E3FADs.

Females traveled further than males (Fig. 1C; F(1, 53) = 8.0 p = 0.007, η2 = 0.13). Female E4FADs traveled the furthest, moving longer distances than male E3FADs (p = 0.02). Average speed was also influenced by sex, such that females traveled faster than males (Fig. 1D; F(1, 53) = 8.07, p = 0.006, η2 = 0.13). As with distance traveled, female E4FADs traveled significantly faster than male E3FADs (p = 0.02). The main effects of genotype (F(1, 53) = 1.92, p = 0.17 for distance traveled; F(1, 53) = 2.01, p = 0.16 for average speed) and genotype by sex interactions (F(1, 53) = 0.06, p = 0.82, distance traveled; F(1, 53) = 0.08, p = 0.78 for average speed) were not significant for either measure.

Experiment 2: Ovariectomy increases anxiety-like behavior in E3FADs

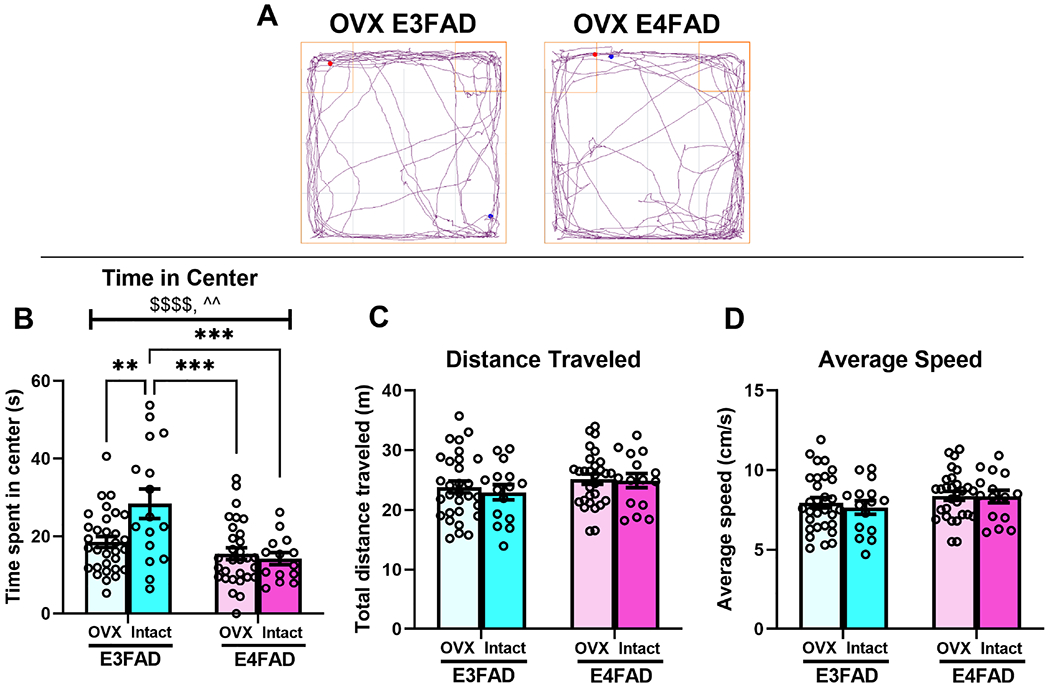

Because oophorectomy before menopause increases AD risk (Rocca et al., 2007), and estrogens are anxiolytic (Walf and Frye, 2006), we sought to determine whether loss of ovarian hormones facilitates increased anxiety-like behavior in the OF in female EFADs. Here, we hypothesized that female E4FADs would spend significantly less time in the center of the OF than every other group, and that OVX would exacerbate this effect. Thus, we tested whether bilateral ovariectomy resulted in decreased time spent in the center of the OF in the EFAD model by comparing anxiety indices of the intact female E3FAD and E4FADs from Experiment 1 to OVXed female E3FAD (n = 32) and E4FADs (n=31).

OVXed female EFADs spent significantly less time in the center of the OF relative to intact female EFADs (Fig. 2B; gonadal status effect: F(1,87) = 16.6, p < 0.0001, η2 = 0.15), and E4FADs spent less time in the center relative to E3FADs (Fig. 2B; genotype effect: F(1,87) = 4.14, p = 0.045, η2 = 0.04). These effects and their interaction (Fig. 2B; F(1,87) = 6.98 p = 0.01, η2 = 0.06 ) were driven by intact female E3FADs spending significantly more time in the center than every other group (p = 0.006 vs OVXed E3FADs; p = 0.0005 vs intact E4FADs; p = 0.0002 vs OVXed E4FADs). Importantly, no differences were observed between OVXed E3FAD and E4FAD females, or intact and OVXed E4FADs, suggesting that OVX induces an E4FAD-like OF phenotype in female E3FADs. For distance traveled and average speed, two-way ANOVAs yielded no significant main effects or interactions, suggesting that all groups traveled similar distances at similar speeds.

Fig. 2. Ovariectomy induces an APOE4-like anxiety phenotype in E3FAD females.

(A) Track plots illustrate representative patterns of movement in ovariectomized EFADs in the open field. (B) E3FAD females spent significantly more time in the center than E4FAD females (&p < 0.05, main effect of genotype), and intact E3FADs spent significantly more time in the center than OVXed EFADs ($$$p < 0.0001, main effect of OVX). Intact E3FADs spent significantly more time in the center relative to every other group (^^p < 0.01, significant interaction; **p < 0.01 vs OVXed E3FADs, ***p < 0.001 vs intact and OVXed E4FADs). (C,D) Distance traveled and average speed did not differ among female EFADs regardless of genotype or gonadal status.

Discussion

Given the prevalence of anxiety in AD patients (Ferretti et al., 2001), understanding whether genetic or sex-specific factors contribute to anxiety-like symptoms is crucial for development of therapeutics. The present study tested whether APOE4 genotype, female sex, and ovarian hormones contribute to increased anxiety-like behavior in a mouse model of AD designed to reproduce APOE-associated disease risk against a background of AD-like pathology. We hypothesized that the APOE4 genotype in this model would be associated with decreased time spent in the center of the OF relative to the APOE3 genotype, and that OVX would be anxiogenic for OF behaviors. Results indicate that APOE4 genotype was anxiogenic in the OF relative to APOE3 genotype, as was ovariectomy in female APOE3 homozygotes. These data provide new insights into factors that may contribute to anxiety in women with AD and suggest that hormone therapy may help alleviate anxiety in some female patients.

In male and female mice expressing human APOE, APOE4 carriers exhibit more anxiety-like behavior than APOE3 carriers (Robertson et al., 2005; Siegel et al., 2012). Data from human patients with probable AD mirror findings from animal models, in that APOE4 is anxiogenic relative to APOE3 (Robertson et al., 2005). These findings are consistent with our data demonstrating that E4FADs spent less time in the center of the OF compared to E3FADs, although this effect appears to be driven largely by female E4FADs. Others have found the APOE4 genotype to be anxiogenic in males in the elevated plus maze (Robertson et al., 2005). However, our results suggest minimal differences in OF behavior between male E3FAD and E4FADs, underscoring the need to use multiple behavioral tasks to provide a more complete understanding of how different APOE genotypes influence anxiety-like behaviors. Although the sex x genotype interaction was not significant, the markedly reduced center time for female E4FADs relative to E3FADs suggests that female sex may exacerbate anxiety-like behavior in APOE4 carriers.

We also found that female EFADs were more active than male EFADs, regardless of genotype, which is consistent with reports that female rodents are more active than males (Beatty, 1979; Rosenfeld, 2017). Although female E4FADs were the most active, they also spent the least amount of time in the center of the OF, suggesting that anxiety about being in a novel environment may have resulted in rapid circling of the periphery in an attempt to escape.

Our results demonstrating that OVXed E3FADs were more anxious than intact E3FADs, and similarly anxious to E4FAD females, are consistent with data demonstrating that OVX increases anxiety-like behavior (de Chaves et al., 2009; Schoenrock et al., 2016). However, we saw no decrease in time spent in the center of the OF in OVXed E4FADs relative to intact E4FADs. This similarity may be attributed to the detrimental impact of APOE4, such that the already low amount of time spent in the center of the OF in E4FAD females prevented OVX from further decreasing this measure. Given that intact female E3FADs spent more time in the center of the OF than OVXed female E3FADs, our data suggest a neuroprotective role for ovarian estrogens against anxiety-like behaviors. If validated in future studies with other anxiety-like behaviors, then these findings may suggest that both ovarian status and APOE genotype should be taken into careful consideration when weighing treatment options for AD patients.

Future work should also examine whether estrogen replacement is anxiolytic in E3FADs and E4FADs, and in APOE3 and APOE4 human carriers. Here we employed only one method of assessing anxiety-like behaviors and examining additional indices of anxiety would provide a more complete understanding of contexts under which APOE4 and hormone loss are anxiogenic. Two important potential confounds must be considered in future experiments examining effects of OVX on anxiety-like behaviors in EFAD mice. First, mice from Experiment 2 underwent surgical procedures, whereas mice from Experiment 1 did not. However, two weeks elapsed between surgery and behavioral testing, which allowed for full recovery prior to OF and should have mitigated any lasting effects from surgery. Nevertheless, sham OVX and intracranial surgeries would serve as important controls in future work to support a causative role of OVX and rule out any detrimental effects of cannulation surgery on brain structures involved in modulating anxiety. Second, mice from Experiment 1 were group housed, whereas mice from Experiment 2 were singly housed. It is possible that group housing protected against anxiety-like behaviors in E3FADs, and that the anxiety-like phenotype present in OVXed E3FADs cannot be fully attributed to OVX. However, because mice were only singly housed for one week prior to testing, chronic or long-lasting effects of single housing, which is known to increase anxiety-like behaviors, is unlikely to have affected OF exploration in the present experiment. Nevertheless, disentangling the effects of single versus group housing in future work would strengthen the conclusion that OVX is responsible for an increased anxiety-like phenotype in E3FADs.

Given results showing a benefit for the potent estrogen 17β-estradiol (E2) on cognition and anxiety-like behaviors, E2 may also be therapeutic for anxiety in AD patients (Walf and Frye, 2006). Furthermore, researchers should explore whether timing of administration following gonadectomy impacts the ability of E2 to decrease anxiety-like behavior, given the critical window for estrogen replacement therapy for other cognitive behaviors. However, whether estrogen replacement therapy may resolve behavioral symptomology of AD in APOE4 carriers remains controversial and deserves further study. In addition, although the results of the present study suggest a detrimental role for APOE4 in promoting anxiety-like behavior in the open field and a neuroprotective role for ovarian estrogens against anxiety-like behavior in the open field, future work must be conducted to rule out possible contributions of experimental confounds related to housing or surgery on such behaviors.

Highlights.

APOE4 genotype decreased time spent in the center of an open field

Ovariectomy decreased center exploration time in APOE3+ females

Estrogens may reduce anxiety-like behavior in APOE3+ but not APOE4+ females

Future work should rule out potential confounds related to housing or surgery

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the primary support of an inaugural Sex and Gender in Alzheimer’s grant (SAGA-17-419092) from the Alzheimer’s Association for this work. Support for the Frick lab was also provided by R01MH107886, 2R15GM118304-02, an 1F31MH118822-01A1 to LRT, and the UW-Milwaukee Office of Undergraduate Research. Additional support for the LaDu lab was provided by R01AG056472, R01AG057008, UH2/3NS100127, R56AG058655, philanthropic support from Lou and Christine Friedrich, and UIC institutional funds.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declarations of Interest

K.M.F. is a co-founder of, and shareholder in, Estrigenix Therapeutics, Inc., a company which aims to improve women’s health by developing safe, clinically proven treatments for the mental and physical effects of menopause. She also serves as the company’s Chief Scientific Officer. The other authors have no actual or potential conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Altemus M, Sarvaiya N, Epperson CN, 2014. Sex differences in anxiety and depression clinical perspectives. Front Neuroendocrinol 35, 320–330. 10.1016/j.yfrne.2014.05.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alzheimer’s Association, 2021. 2021 Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen K, Launer LJ, Dewey ME, Letenneur L, Ott A, Copeland JR, Dartigues JF, Kragh-Sorensen P, Baldereschi M, Brayne C, Lobo A, Martinez-Lage JM, Stijnen T, Hofman A, 1999. Gender differences in the incidence of AD and vascular dementia: The EURODEM Studies. EURODEM Incidence Research Group. Neurology 53, 1992–1997. 10.1212/wnl.53.9.1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arendash GW, King DL, Gordon MN, Morgan D, Hatcher JM, Hope CE, Diamond DM, 2001. Progressive, age-related behavioral impairments in transgenic mice carrying both mutant amyloid precursor protein and presenilin-1 transgenes. Brain Research 891, 42–53. 10.1016/S0006-8993(00)03186-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey KR, Crawley JN, 2009. Anxiety-related behaviors in mice, in: Buccafusco JJ (Ed.), Methods of Behavior Analysis in Neuroscience, Frontiers in Neuroscience. CRC Press/Taylor & Francis, Boca Raton (FL). [Google Scholar]

- Beatty WW, 1979. Gonadal hormones and sex differences in nonreproductive behaviors in rodents: organizational and activational influences. Horm Behav 12, 112–163. 10.1016/0018-506x(79)90017-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Chaves G, Moretti M, Castro AA, Dagostin W, da Silva GG, Boeck CR, Quevedo J, Gavioli EC, 2009. Effects of long-term ovariectomy on anxiety and behavioral despair in rats. Physiol Behav 97, 420–425. 10.1016/j.physbeh.2009.03.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ertekin-Taner N, 2007. Genetics of Alzheimer’s disease: a centennial review. Neurol Clin 25, 611–667, v. 10.1016/j.ncl.2007.03.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferretti L, McCurry SM, Logsdon R, Gibbons L, Teri L, 2001. Anxiety and Alzheimer’s disease. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 14, 52–58. 10.1177/089198870101400111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flanigan TJ, Xue Y, Kishan Rao S, Dhanushkodi A, McDonald MP, 2014. Abnormal vibrissa-related behavior and loss of barrel field inhibitory neurons in 5xFAD transgenics. Genes Brain Behav 13, 488–500. 10.1111/gbb.12133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jawhar S, Trawicka A, Jenneckens C, Bayer TA, Wirths O, 2012. Motor deficits, neuron loss, and reduced anxiety coinciding with axonal degeneration and intraneuronal Aβ aggregation in the 5XFAD mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging 33, 196.e29–40. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2010.05.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph R, Gallagher RE, 1980. Gender and early environmental influences on activity, overresponsiveness, and exploration. Dev Psychobiol 13, 527–544. 10.1002/dev.420130512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Launer LJ, Andersen K, Dewey ME, Letenneur L, Ott A, Amaducci LA, Brayne C, Copeland JR, Dartigues JF, Kragh-Sorensen P, Lobo A, Martinez-Lage JM, Stijnen T, Hofman A, 1999. Rates and risk factors for dementia and Alzheimer’s disease: results from EURODEM pooled analyses. EURODEM Incidence Research Group and Work Groups. European Studies of Dementia. Neurology 52, 78–84. 10.1212/wnl.52.1.78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MC, Kerr KM, Orr PT, Frick KM, 2008. Estradiol-induced enhancement of object memory consolidation involves NMDA receptors and protein kinase A in the dorsal hippocampus of female C57BL/6 mice. Behav Neurosci 122, 716–721. 10.1037/0735-7044.122.3.716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippi SLP, Smith ML, Flinn JM, 2018. A novel hAPP/htau mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease: Inclusion of APP with tau exacerbates behavioral deficits and zinc administration heightens tangle pathology. Front Aging Neurosci 10, 382. 10.3389/fnagi.2018.00382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michels A, Multhammer M, Zintl M, Mendoza MC, Klünemann H-H, 2012. Association of apolipoprotein E ε4 (ApoE ε4) homozygosity with psychiatric behavioral symptoms. J Alzheimer’s Dis 28, 25–32. 10.3233/JAD-2011-110554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter VR, Buxton WG, Fairbanks LA, Strickland T, O’Connor SM, Rosenberg-Thompson S, Cummings JL, 2003. Frequency and characteristics of anxiety among patients with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 15, 180–186. 10.1176/jnp.15.2.180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prut L, Belzung C, 2003. The open field as a paradigm to measure the effects of drugs on anxiety-like behaviors: a review. Eur J Pharmacol 463, 3–33. 10.1016/s0014-2999(03)01272-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radde R, Bolmont T, Kaeser SA, Coomaraswamy J, Lindau D, Stoltze L, Calhoun ME, Jäggi F, Wolburg H, Gengler S, Haass C, Ghetti B, Czech C, Hölscher C, Mathews PM, Jucker M, 2006. Abeta42-driven cerebral amyloidosis in transgenic mice reveals early and robust pathology. EMBO Rep 7, 940–946. 10.1038/sj.embor.7400784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson J, Curley J, Kaye J, Quinn J, Pfankuch T, Raber J, 2005. ApoE isoforms and measures of anxiety in probable AD patients and Apoe−/− mice. Neurobiol Aging 26, 637–643. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2004.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocca WA, Bower JH, Maraganore DM, Ahlskog JE, Grossardt BR, de Andrade M, Melton LJ, 2007. Increased risk of cognitive impairment or dementia in women who underwent oophorectomy before menopause. Neurology 69, 1074–1083. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000276984.19542.e6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocca WA, Grossardt BR, Maraganore DM, 2008. The long-term effects of oophorectomy on cognitive and motor aging are age dependent. Neurodegener Dis 5, 257–260. 10.1159/000113718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfeld CS, 2017. Sex-dependent differences in voluntary physical activity. J Neurosci Res 95, 279–290. 10.1002/jnr.23896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenrock SA, Oreper D, Young N, Ervin RB, Bogue MA, Valdar W, Tarantino LM, 2016. Ovariectomy results in inbred strain-specific increases in anxiety-like behavior in mice. Physiol Behav 167, 404–412. 10.1016/j.physbeh.2016.09.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seibenhener ML, Wooten MC, 2015. Use of the open field maze to measure locomotor and anxiety-like behavior in mice. J Vis Exp 52434. 10.3791/52434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel JA, Haley GE, Raber J, 2012. Apolipoprotein E isoform-dependent effects on anxiety and cognition in female TR mice. Neurobiol Aging 33, 345–358. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2010.03.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon P, Dupuis R, Costentin J, 1994. Thigmotaxis as an index of anxiety in mice. Influence of dopaminergic transmissions. Behav Brain Res 61, 59–64. 10.1016/0166-4328(94)90008-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterniczuk R, Antle MC, LaFerla FM, Dyck RH, 2010. Characterization of the 3xTg-AD mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease: Part 2. Behavioral and cognitive changes. Brain Research 1348, 149–155. 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.06.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao Y, Peters ME, Drye LT, Devanand DP, Mintzer JE, Pollock BG, Porsteinsson AP, Rosenberg PB, Schneider LS, Shade DM, Weintraub D, Yesavage J, Lyketsos CG, Munro CA, 2018. Sex differences in the neuropsychiatric symptoms of patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen 33, 450–457. 10.1177/1533317518783278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teri L, Ferretti LE, Gibbons LE, Logsdon RG, McCurry SM, Kukull WA, McCormick WC, Bowen JD, Larson EB, 1999. Anxiety of Alzheimer’s disease: prevalence, and comorbidity. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 54, M348–352. 10.1093/gerona/54.7.m348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walf AA, Frye CA, 2006. A review and update of mechanisms of estrogen in the hippocampus and amygdala for anxiety and depression behavior. Neuropsychopharmacol 31, 1097–1111. 10.1038/sj.npp.1301067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youmans KL, Tai LM, Nwabuisi-Heath E, Jungbauer L, Kanekiyo T, Gan M, Kim J, Eimer WA, Estus S, Rebeck GW, Weeber EJ, Bu G, Yu C, LaDu MJ, 2012. APOE4-specific changes in Aβ accumulation in a new transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer disease. J Biol Chem 287, 41774–41786. 10.1074/jbc.M112.407957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]