Abstract

Purpose:

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) patients unfit for, or resistant to, intensive chemotherapy are often treated with DNA methyltransferase inhibitors (DNMTis). Novel combinations may increase efficacy. In addition to demethylating CpG island gene promoter regions, DNMTis enhance poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP1) recruitment and tight binding to chromatin, preventing PARP-mediated DNA repair, downregulating homologous recombination (HR) DNA repair and sensitizing cells to PARP inhibitor (PARPi). We previously demonstrated DNMTi and PARPi combination efficacy in AML in vitro and in vivo. Here we report a phase I clinical trial combining the DNMTi decitabine and the PARPi talazoparib in refractory/relapsed AML.

Experimental Design:

Decitabine and talazoparib doses were escalated using a 3 + 3 design. Pharmacodynamic studies were performed on Cycle 1 Days 1 (pre-treatment), 5 and 8 blood blasts.

Results:

Doses were escalated in seven cohorts [25 patients, including 22 previously treated with DNMTi(s)] to a recommended phase II dose combination of decitabine 20 mg/m2 intravenously daily for 5 or 10 days and talazoparib 1 mg orally daily for 28 days, in 28-day cycles. Grade 3–5 events included fever in 19 and lung infections in 15, attributed to AML. Responses included complete remission with incomplete count recovery in two patients (8%) hematologic improvement in three. Pharmacodynamic studies showed the expected DNA demethylation, increased PARP trapping in chromatin, increased γH2AX foci and decreased HR activity in responders. γH2AX foci increased significantly with increasing talazoparib doses combined with 20 mg/m2 decitabine.

Conclusions:

Decitabine/talazoparib combination was well tolerated. Expected pharmacodynamic effects occurred, especially in responders.

INTRODUCTION

The mainstay of remission induction therapy for acute myeloid leukemia (AML) for 50 years has been combination cytotoxic chemotherapy including the nucleoside analogue cytarabine and an anthracycline (1,2). Post-remission therapy may consist of high-dose cytarabine and/or allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HSCT). Survival has improved in younger adult patients overall, but not in those with prognostically unfavorable karyotypes or molecular abnormalities, nor in patients with advanced age or significant comorbidities. New therapies are needed for patients in groups with poor responses to cytotoxic chemotherapy and for those with AML resistant to, or relapsing after, initial therapy. These patients are currently often treated with DNA methyltransferase inhibitors (DNMTis).

The DNMTi decitabine (5-aza-2’-deoxycytidine) is a cytidine analog that is triphosphorylated and incorporated into DNA, covalently binds DNMTs into DNA at sites of DNA damage, inhibits DNA methylation and reverses DNA methylation-induced gene silencing (3). Decitabine was approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for treatment of myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), and a schedule of 20 mg/m2 intravenously (IV) daily for five days every 4 weeks was subsequently adopted (4,5). Decitabine also has efficacy in AML and is well tolerated, and therefore is also currently in widespread use to treat AML in previously untreated patients “unfit” for chemotherapy and patients with refractory or relapsed AML with low likelihood of response to intensive chemotherapy (6–11). The complete remission (CR) rate for previously untreated AML patients treated with the 5-day decitabine regimen is in the range of 25%, and median survival is in the range of 7 months (6–8). Decitabine has also been used in a 10-day regimen for AML, with a higher response rate and longer response duration in some reports (9–13). To improve responses, combinations of DNMTis and novel agents are being tested in clinical trials (1,2).

Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors have mainly been applied toward creating synthetic lethality in breast and ovarian cancers in patients with germline BRCA mutations and consequent homologous recombination (HR) defect, but combinations with DNMTis are being explored in sporadic cancers. The Rassool laboratory demonstrated that DNMTis enhance PARP1 recruitment and tight binding to chromatin, preventing PARP-mediated DNA repair and thus enhancing the efficacy of potent PARP inhibitors such as talazoparib and creating synergistic cytotoxicity in AML cells in vitro and in vivo (14). They subsequently showed that DNMTis also downregulate HR DNA repair, creating an HR defect that sensitizes cells to PARP inhibitors (15,16). Another group combined talazoparib, apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease 1 (APE1) inhibitor III and decitabine, demonstrating enhanced efficacy in AML, MDS and chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML) cells in vitro (17).

A phase I clinical trial of talazoparib in patients with solid tumors demonstrated good tolerability and established a dose of 1 mg orally daily as the recommended phase II dose (18). Talazoparib was subsequently approved at this dose for germline BRCA-mutated, HER2-negative locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer based on the EMBRACA phase III clinical trial (19). The only previous clinical trial of talazoparib in hematologic malignancies was a phase I trial testing doses of 0.1 to 2 mg daily, showing limited single-agent activity (20).

We designed and completed a phase I clinical trial combining decitabine and talazoparib in patients with relapsed or refractory AML, with correlative laboratory studies.

METHODS

Study design

This was a phase I clinical trial combining decitabine and talazoparib in patients with relapsed or refractory AML. The study (NCT02878785) was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki after approval by the ethics committees of participating centers. Written informed consent was obtained from each patient. The objectives were to determine the recommended phase II doses of decitabine and talazoparib in combination, to test for leukemia response, and to explore pharmacodynamic effects and cytogenetic and molecular predictors of response. Patients were enrolled at the University of Maryland Greenebaum Comprehensive Cancer Center (UMGCCC) and the University of Southern California Norris Comprehensive Cancer Center. Pathology and cytogenetic studies were performed at each institution. Doses were escalated using a 3 + 3 design, as detailed below. The study was monitored by the UMGCCC Data and Safety Monitoring and Quality Assurance Committee.

Patients

Eligible patients were ≥18 years with AML diagnosed by 2008 World Health Organization criteria (21), occurring de novo or following a prior hematologic disorder, including MDS, CMML or Philadelphia chromosome-negative myeloproliferative neoplasm, and/or therapy-related, and relapsed after, or refractory to, ≥1 prior therapy, and considered unfit for, or unlikely to respond to, cytotoxic chemotherapy. Previous cytotoxic chemotherapy had to have been completed ≥3 weeks before Day 1 of study treatment and all adverse events recovered to Grade <1. Previous DNMTi therapy for AML or for a prior hematologic disorder was allowed, also with last dose ≥3 weeks before Day 1 of study treatment. Previous allo-HSCT was allowed if patients were ≥60 days from stem cell infusion, did not have grade >1 graft-versus-host disease, and were ≥2 weeks off immunosuppressive therapy. Other requirements included ECOG performance status ≤2, AST(SGOT)/ALT(SGPT) ≤2.5 × institutional upper limit of normal (ULN), total bilirubin <ULN unless thought due to hemolysis or to Gilbert’s syndrome, and serum creatinine <ULN or creatinine clearance ≥60 mL/min.

Exclusion criteria included acute promyelocytic leukemia, known central nervous system leukemia, uncontrolled intercurrent illness or infection, known HIV infection and prior talazoparib treatment. Hyperleukocytosis with >50 × 109/L blasts was an exclusion; hydroxyurea was permitted for count control, but had to be stopped ≥24 hours before starting study treatment. Patients were withdrawn from the study if >50 × 109/L blasts occurred or recurred >14 days after starting study treatment.

Pre-treatment studies

Bone marrow (BM) aspirate and biopsy were performed within 14 days before starting protocol therapy. Cytogenetic analysis was performed in all 25 patients and myeloid mutation analysis in 24 patients as standard-of-care studies.

Treatment

Decitabine was administered IV daily for 5 days every 28 days, and for 10 days in the last cohort. Talazoparib was initiated orally daily for 28 days on Day 1 of Cycle 1. On days when both decitabine and talazoparib were given, decitabine was given after talazoparib to ensure simultaneous exposure to both drugs. Talazoparib was administered regardless of food intake.

Treatment continued on an ongoing basis until disease progression, intercurrent illness preventing further treatment, unacceptable adverse event(s) or patient or physician decision to stop.

Talazoparib was provided by Pfizer Inc. (New York, NY).

Dose escalation

The dose escalation schema for both drugs is shown in Table 1; dose combinations tested are in bold. Doses were escalated based on tolerability using a 3 + 3 design. Dose escalation decision rules are shown in Supplementary Table S1. Once the maximum tolerated dose (MTD) for decitabine combined with 0.25 mg talazoparib was established, the dose of talazoparib was escalated with the dose of decitabine fixed at the provisional MTD dose. Talazoparib was then tested with 10-day decitabine at MTD doses.

Table 1. Dose escalation schema.

The ‘outer layer’ of this nested dose escalation trial escalated the dose of the two drugs by sequentially going through dose levels 1–7 in the table using the standard algorithm of the 3+3 design. If the provisional MTD for decitabine in combination with 0.25 mg talazoparib had been dose level 1 or 2, one or the other of the ‘inner layers’ of the trial (a, b, c) would have been activated, escalating the dose of talazoparib with the dose of decitabine remaining fixed.

| Talazoparib po x 28 days | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.25 mg | 0.50 mg | 0.75 mg | 1.0 mg | ||

| Decitabine IV X 5 days | 10 mg/m 2 | 1 | 1a | 1b | 1c |

| 15 mg/m 2 | 2 | 2a | 2b | 2c | |

| 20 mg/m 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| Decitabine IV X 10 days | 20 mg/m 2 | 7 | |||

IV – intravenously

po – orally

Toxicity evaluation

Dose-limiting toxicities (DLTs) were evaluated in Cycle 1. Toxicities were evaluated according to National Cancer Institute (NCI) Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) Version 4.0. DLTs consisted of any of the following adverse events considered possibly, probably or definitely related to study therapy: 1) any grade 4 treatment-related non-hematologic toxicity, except for infection, fever, neutropenic fever or bleeding, which are expected in this patient population; 2) any grade 3 treatment-related non-hematologic toxicity not resolving to Grade ≤2 within 48 hours, except for infection, fever, neutropenic fever or bleeding; or 3) myelosuppression if absolute neutrophil count (ANC) <0.5 × 109/L and platelet count <20 × 109/L (untransfused) persisted on day 43, with BM cellularity ≤5% and no evidence of leukemia in BM.

Response assessment

Response definitions were according to the revised International Working Group (IWG) response criteria for AML (22). Other response endpoints, including achievement of hematologic improvement (HI), as defined by the 2006 modified IWG criteria for myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS), were also collected (23). BM aspirate and biopsy were performed between Days 25 and 29 of Cycle 1, as well as subsequent cycles unless blasts persisted in the peripheral blood (PB), until documentation of CR or CR with incomplete count recovery (CRi). BM aspirate and biopsy were also performed as needed to evaluate lack of count recovery (ANC <1 × 109/L and/or platelet count <50 × 109/L) by Day 43 in the absence of PB blasts.

Response duration was measured from the time criteria for CR or CRi were met until the first date that recurrent or progressive AML was objectively documented. Overall survival was measured from time of enrollment to time of death.

Management of hematologic toxicity

Timing of cycle initiation and decitabine and talazoparib dose levels starting with Cycle 2 were guided by ANC/platelet counts after the prior cycle and PB and/or BM blast percentage. Supplementary Table S2 shows dose modifications and delays based on Day ≥28 PB counts starting with Cycle 2.

The treating physician could also delay treatment on Day 29 of any cycle regardless of ANC/platelet counts and/or leukemic blasts if deemed in the patient’s best interest. Treatment was then resumed when deemed in the patient’s best interest to do so. Reasons for delaying and for restarting were documented in the medical record.

Gene mutation network analysis

To identify mutations that potentially correlated with patient responses, the network of gene mutations was analyzed, stratified by patient response, using igraph software (igraph.org). Gene mutation profiles were analyzed in patients with ≥2 mutated genes.

Samples for pharmacodynamic studies

PB samples were obtained for pharmacodynamic studies from patients with ≥20% blood blasts during Cycle 1 on Day 1 before treatment, then Day 5 one hour after completion of decitabine infusion, Day 8 any time, and Day 29 before Cycle 2 treatment. For patients receiving 10-day decitabine, sampling was on Day 1 before treatment, and Days 5, 8 and 10 one hour after completion of decitabine infusion, then 29. BM samples were collected at screening and on Day 25–29 of Cycle 1, before Cycle 2 treatment. A schematic of treatment and sample collection for the talazoparib and 5- and 10-day decitabine regimens is shown in Supplementary Figure S1.

Mononuclear cells (MNCs) were isolated from AML samples by density centrifugation over Ficoll-Paque (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO). Cells were counted on the Countess automated counter (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham MA). MNCs were viably cryopreserved in 95% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 5% dimethylsulfoxide for genome-wide DNA methylation analysis, the proximity ligation assay and measurement of γH2AX foci. MNCs were also centrifuged at 1500 rpm for 5 minutes and cell pellets were flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen for the HR activity assay and for RNA sequencing.

Genome-wide DNA methylation analysis

Genome-wide DNA methylation analysis was performed using described methodology (24,25). Raw IDAT files were loaded and processed by functions in minfi R package. Data were normalized by preprocess Quantile function. Probes with higher than 0.01 detection p-values, on sex chromosomes or overlapped with SNPs were filtered out. Differential methylation analysis was performed on M values by limma package with patient ID as a covariate. Differentially methylated positions (DMPs) are defined by <0.05 false discovery rate (FDR) values. Heatmaps were generated on z-score-normalized beta values of DMPs.

Proximity ligation assay

The proximity ligation assay (PLA) was used to determine whether PARP trapping was increased in chromatin fractions of AML blasts after decitabine and talazoparib combination treatment, compared with pre-treatment samples. The Duolink In Situ assay kit (Sigma) was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions (sigma.com/duolink). Briefly, viably frozen AML MNCs were processed as described above. Cells were incubated overnight at 4°C with 1:400 primary mouse anti-PARP1 (Sigma) and rabbit anti-H2Ax (Cell Signaling Technologies, Danvers, MA) antibodies, followed by three washes in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Secondary antibodies conjugated to PLA plus and minus probes were diluted 1:5 in antibody dilution buffer (included in kit) and slides were incubated for 1 hour at 37°C, followed by three washes in PBS. Ligation, amplification, and counterstaining were performed according to kit instructions. Slides were examined using a Nikon (Melville, NY) Eclipse 80i fluorescent microscope. Results were reported as average number of fluorescent spots per cell in each sample.

γH2AX foci

Viably frozen AML MNCs were thawed and cytospun in PBS onto glass slides for 5 minutes at 200 rpm on a Shandon Cytospin 4 (Thermo Fisher). Cells were fixed for 10 minutes in 4% paraformaldehyde, washed three times in Dulbecco’s PBS (DPBS), permeabilized for 10 minutes in permeabilization solution (50 mM NaCl, 3 mM MgCl2, 10 mM HEPES, 200 mM sucrose and 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS 1X) then in DPBS + 1% BSA, then blocked overnight in 10% FBS. Cells were incubated with 1:100 mouse monoclonal anti-γH2A.x antibody (Millipore Sigma, Burlington, MA) or isotype control for one hour at 37°C in DPBS-BSA, then washed, incubated with 1:200 Dylight 594-anti-mouse or 488-anti-rabbit antibody (KPL, Gaithersburg, MD) for one hour at 37°C, and counterstained with 0.3 μg/ml 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole, dihydrochloride (DAPI, Promega, Madison, WI) in mounting medium (Vectashield, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA).

Images were examined and acquired using a Nikon Eclipse 80i fluorescence microscope (100×/1.4 oil). For quantitation of foci, images from ≥50 cells/slide were captured using a charge-coupled device (CCD) camera and the imaging software NIS Elements (BR 3.00, Nikon). γH2AX foci contained within these imaged cells were counted and the data were expressed as numbers of foci per cell. Results were reported as mean number of foci/cell in each sample. Immunostaining was compared on MNCs from AML PB samples obtained on Day 1 pre-treatment and Days 5 and 8 following treatment.

Homologous recombination activity

Nuclear extracts were prepared using the Cell Lytic NuCLEAR Extraction Kit (Sigma-Aldrich) and dialysed for two hours using the Plus One Mini Dialysis Kit 1kDa (GE Healthcare) in dialysis solution (20 mM HEPES pH9, 100 mM KCl, 0.2 mM EDTA, 20% glycerol, 0.5 mM DTT, 0.1 mM PMSF). Protein content was quantified by Nanodrop and diluted to 0.5 μg/μl in DNase/RNase-free water. Diluted nuclear extracts were incubated with 5 μl each of dl-1 and dl-2 plasmid (Homologous Recombination Assay Kit, Norgen Biotek, Thorold, ON) in reaction buffer for 2 hours at 30°C. Plasmid DNA was recovered with the QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD), and the relative quantity of recombined product was determined with the quantitative real-time PCR CFX384 Real Time System (BioRad, Hercules, CA) using PCR primers spanning the repair site, normalized against amplification of a distant site (primers supplied by Norgen Biotek). PCR product band density of post-treatment samples (Days 5 and 8) was estimated relative to that of Day 1 (pretreatment) samples for each patient using Bio-Rad’s Quantity One Software. Day 5 and Day 8 samples were normalized to Day 1 (set at 1) and expressed as fold change in HR activity.

RNA sequencing

Libraries were prepared from 500 ng total RNA by the Van Andel Genomics Core using the Kapa RNA HyperPrep Kit with RiboseErase (v1.16) (Kapa Biosystems, Wilmington, MA) following manufacturer instructions. RNA was sheared to 300–400 bp. Prior to PCR amplification, cDNA fragments were ligated to IDT for Illumina TruSeq UD Indexed adapters (Illumina, San Diego CA, USA). Quality and quantity of the finished libraries were assessed using a combination of Agilent DNA High Sensitivity chip (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA), QuantiFluor® dsDNA System (Promega) and Kapa Illumina Library Quantification qPCR assays. Individually indexed libraries were pooled and 100 bp paired-end sequencing was performed on an Illumina NovaSeq6000 sequencer using an S4, 200 bp sequencing kit to an average depth of 40–50M reads per sample. Base calling was done by Illumina RTA3 and output of NCS was demultiplexed and converted to FastQ format with Illumina Bcl2fastq v1.9.0.

Statistical analysis

Assays were performed using three technical replicates from each sample and calculating the average value of resulting measure. Within-patient changes in biomarkers were evaluated using the non-parametric, paired observations, Student’s t-test or Wilcoxon signed rank test. Paired differences were obtained from Day 5 minus Day 1, Day 8 minus Day 1, and Day 8 minus Day 5. For dose levels 3, 4, 5, and 6, with a fixed decitabine dose of 20 mg/m2 IV X 5 days combined with increasing talazoparib doses of 0.25 mg, 0.5 mg, 0.75 mg and 1.0 mg orally x 28 days, we evaluated the presence of a dose-response relationship for talazoparib using the non-parametric Spearman’s Rank Correlation Coefficient, Rs, and tested the null hypothesis of Rs=0. Overall survival was estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method with the Mantel-Cox logrank test for differences between groups. Statistical analyses were conducted in IMB® SPSS® release 27.0.0 (released 2020, Armonk, NY: IBM Corp), and significance was defined as two-tailed p<0.05 for all comparisons except where explicitly noted.

Data Availability

The data generated in this study are not publicly available as information could compromise patient privacy, but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

RESULTS

Patients

A total of 25 patients, including 15 men and 10 women, with relapsed or refractory AML were enrolled on the study (Table 2). Pre-treatment characteristics are summarized in Supplementary Table S3. Median age was 70 (range, 37 to 89) years. AML was relapsed in 14 patients and refractory in 11. Karyotypes were complex in 8, and two had t(3;3). TP53 mutations were present in 6 of 24 patients with molecular studies completed, and ASXL1 mutations in 5 others. Importantly, 22 of 25 patients had been previously treated with decitabine and/or azacitidine; median number of courses received was 8 (range, 2–40). Thirteen had received decitabine; median number of decitabine courses was 3 (range, 2–32).

Table 2. Patient characteristics.

| Cohort | Patient | Age/ Sex | Karyotype | Mutations | Status | Prior DNMTi | WBC* | Cycles received | Response | Survival (mos) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 002 | 75F | Normal | NRAS | Ref | AZAx7 DACx3 |

2.5 | 2 | No | 2 |

| 003 | 64F | Complex | TP53 | Rel | DACx9 | 3.4 | 4 | No | 3.2 | |

| 005 | 78M | Normal |

FLT3-ITD

NPM1, SF3B1 WT1 |

Ref | AZAx12 DACx3 |

6.2 | 2 | No | 2.3 | |

| 2 | 006 | 75F | Complex |

ASXL1

IDH2, RUNX1 SRSF2 |

Ref | AZA x 5 | 1.4 | 6 | HI | 5.4 |

| 007 | 69M | Normal |

ASXL1

FLT3-ITD RUNX1 SRSF2 |

Ref | DACx3 | 12.2 | 7 | HI | 6.9 | |

| 008 | 89M | del(16) |

DNMT3A ETV6

PTPN11 SF3B1 |

Ref | AZAx37 DACx3 |

41.8 | 3 | No | 2.3 | |

| 3 | 012 | 37F | Complex | CEPBA, TP53 | Rel | None | 5.9 | 5 | HI | 8.3 |

| 013 | 69M | Normal |

ASXL1, IDH2

MPL, U2AF1 |

Ref | DACx32 | 34.6 | 3 | No | 3.6 | |

| 015 | 70M | Near-tetraploidy, t(3;3) |

TP53 | Ref | AZAx7 | 1 | 17 | No | 19.2 | |

| 4 | 020 | 87M | Normal | FLT3-ITD NPM1, TET2 | Rel | AZAx3 | 2.3 (HU) | 2 | No | 3.2 |

| 023 | 73M | Normal | TP53, ASXL1 DNMT3A | Rel | DACx16 | 1.8 | 1 | Died (sepsis) | 1 | |

| 025 | 45F | Complex | EED, SUZ12 | Rel | DACx2 | 18.2 | 2 | No | 5.2 | |

| 026 | 73M | Complex | TP53 | Ref | DACx2 | 0.6 | 2 | No | 5 | |

| 029 | 78M | t(4;7) |

ASXL1, GATA2, TET2

RUNX1 |

Rel | DACx16 | 2.0 | 2 | No | 2.8 | |

| 030 | 53F | t(3;3), -7 |

PTPN11

GATA2, ETV6 SF1 |

Rel | DACx4 | 48.1 (HU) | 1 | Died (sepsis) | 1 | |

| 031 | 86M | Normal |

ASXL1,

ZRSR2

STAG2, TET2 NRAS, KRAS ASXL2 |

Ref | AZAx4 | 22.6 (HU) | 7 | No | 7.9 | |

| 5 | 033 | 74M | del(5q) |

ASXL1, RUNX1

CEPBA

SRSF2, TET2 |

Rel | AZAx9 | 4 | 4 | No | 7.2 |

| 034 | 63F | inv(1) |

NPM1

DNMT3A NRAS |

Rel | DACx10 | 2.3 | 3 | CRi | 4.2 | |

| 036 | 63F | Normal | ND | Rel | AZAx? | 0.3 | 1 | ND | 2.4 | |

| 6 | 038 | 57F | Complex | None | Rel | AZAx6 | 1.6 | 2 | No | 14 |

| 040 | 55M | Complex | U2AF1, ETV6 | Ref | AZAx8 | 1.0 | 3 | No | 6.9 | |

| 041 | 73M | del(20q) | ND | Rel | DACx2 | 0.4 | 1 | No | 2.1 | |

| 7 | 042 | 71M | Normal | NPM1, DNMT3A, FLT3, TET2 KRAS, NRAS | Rel | None | 4.2 | 6 | CRi | 13.8 |

| 043 | 55M | t(8;21) | RAD21, TET2 CEBPA | Ref | AZAx9 | 9.8 | 2 | No | 4.2 | |

| USC-004* | 53F | Complex | TP53 , NF1 | Ref | None | 0.23 | 1 | No | 3 |

x106/ml Ref=Refractory; Rel=Relapsed; DNMTi=DNA methyltransferase inhibitor; AZA=azacitidine; DAC=decitabine

Dose escalation and adverse events

Decitabine and talazoparib doses were successfully escalated from Cohort 1 to Cohort 7 (Table 1), using a 3+3 design. In Cohort 4, the second patient died of sepsis on Day 26 of Cycle 1. Although this death was thought to be due to AML, rather than to treatment, it was considered a DLT, and the cohort was expanded. The sixth patient in Cohort 4 died of sepsis on Day 23 of Cycle 1, but this death was clearly attributable to AML, and was not considered a DLT. A seventh patient was added as a replacement. All other cohorts included only three patients. Based on the generally acceptable safety profile of the combination, the expansion of Cohort 6 was achieved by adding 3 patients receiving decitabine 20 mg/m2 daily for 10 days, rather than 5 days, and talazoparib 1 mg daily (“Cohort 7”). The MTD was not reached at dose level 6, so the RP2D of decitabine is 20 mg/m2 combined with a talazoparib dose of 1 mg. With zero of the six patients treated at the RP2D experiencing a DLT, we estimate the upper bound of the one-sided exact binomial 95% confidence interval at 39.3%.

Hematologic toxicities could not be assessed in the presence of persistent AML (Table 2). Grade 5 non-hematologic toxicities included lung infection/respiratory, sepsis and fungal infection, grade 4 included sepsis, respiratory, fever and transaminitis, and grade 3 included sepsis, respiratory and fever (Table 3). The most common grade 3–5 events were fever in 19 and lung infections in 15. Non-hematologic toxicities were all assessed as disease-related, rather than treatment-related.

Table 3. Non-hematologic adverse events.

| Grade | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Toxicity | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Respiratory | 3 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 2 |

| Infection, lung | 0 | 1 | 13 | 0 | 2 |

| Sepsis/bacteremia | 0 | 0 | 2 | 8 | 2 |

| Fungal infection | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Other infections | 0 | 5 | 8 | 0 | 0 |

| Fever | 1 | 1 | 17 | 2 | 0 |

| Intracranial bleed | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Pericardial tamponade | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Nausea | 5 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Vomiting | 7 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Diarrhea | 7 | 6 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Transaminitis | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Hyperbilirubinemia | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 0 |

| Elevated creatinine | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

Median number of courses received was 2 (range, 1 to 17).

Among 20 patients who received >1 treatment cycle, 15 initiated Cycle 2 on Day 29 of Cycle 1, 2 initiated on Day 36, after review of the Day 29 bone marrow, and 3 initiated on Days 38, 42 and 51, following delays due to infections/hospitalizations.

Treatment reponses

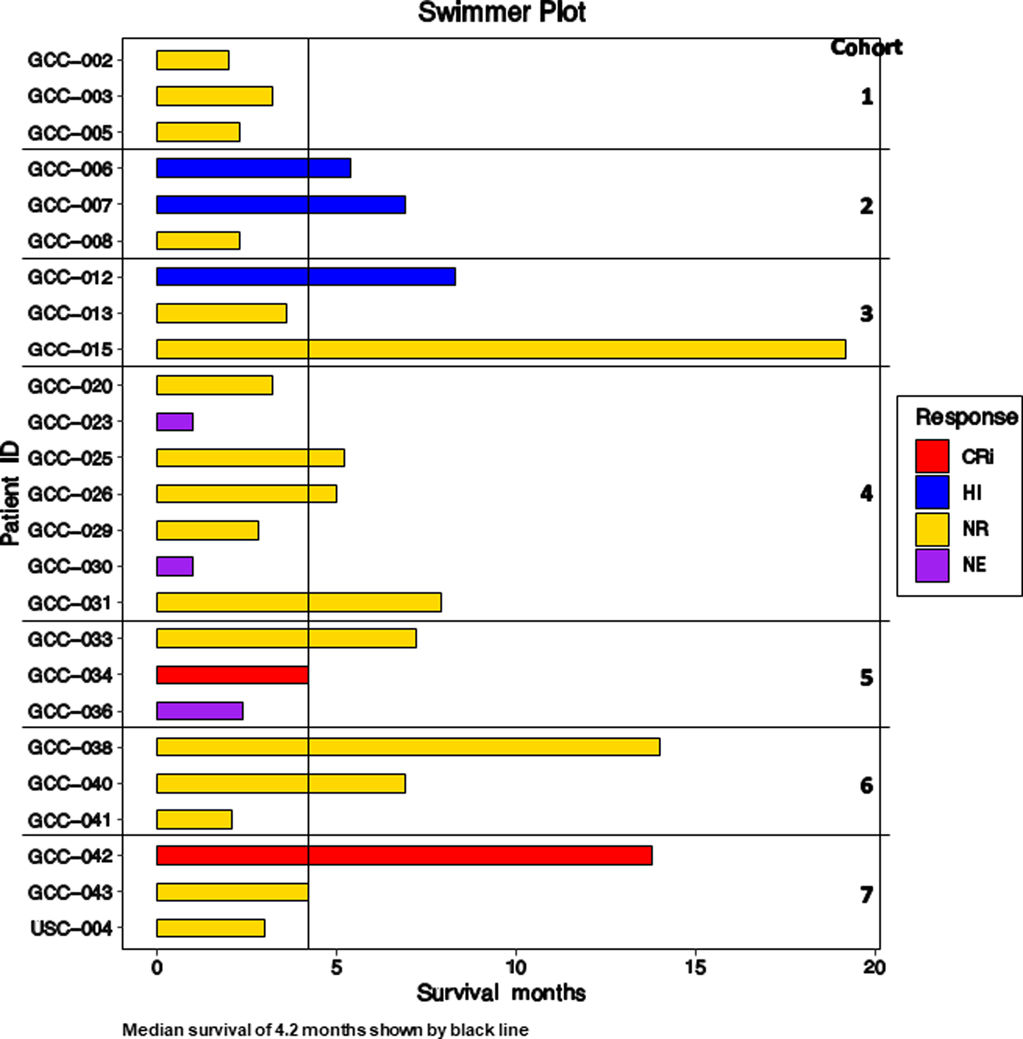

A swimmer plot for all patients is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Swimmer plot for all patients.

CRi = Complete remission with incomplete count recovery; HI = Hematologic improvement; NR = No response; NE = Not evaluable.

Responses included CRi in one patient in Cohort 5 and one in Cohort 7, and HI in two patients in Cohort 2 and one in Cohort 3. The Cohort 7 patient who achieved CRi and the Cohort 3 patient who achieved HI were two of the three patients in the study who were DNMTi-naïve.

The responding patient in Cohort 5 achieved CRi after 3 cycles, but had repeated infections while pancytopenic and opted to stop treatment. The responding patient in Cohort 7 achieved CRi after 2 cycles, then relapsed after completing 6 cycles. The patients with HI received 6, 7 and 5 cycles of treatment. The third patient in Cohort 3 did not meet criteria for response, but had stable disease through 17 cycles of treatment.

Response and survival did not correlate (Supplementary Figure S2). Median survival was 4.2 months overall; it was 3.2 months, 95% CI (2.8. 3.6) months, in non-responders, and 6.9 months, 95% CI (3.7, 10.1) months, in responders (p=0.26, Mantel-Cox logrank test).

Molecular features related to treatment response

NPM1, DNMT3A and NRAS mutations were present in blasts of both patients who achieved CRi, while ASXL1, RUNX1 and SRSF2 mutations were present in two of the three patients who achieved HI (Table 2 and Supplementary Figure S3). The third patient in Cohort 3, with the longest survival (Figure 1), had the t(3;3) cytogenetic abnormality and a TP53 mutation.

Pharmacodynamic effects

We expected that decitabine treatment would decrease genome-wide methylation. We also expected that decitabine and talazoparib treatment would increase PARP trapping in chromatin, measured in the PLA assay, that cytotoxic DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) would increase, shown by increased γH2AX foci/cell, and that HR activity would be downregulated by treatment.

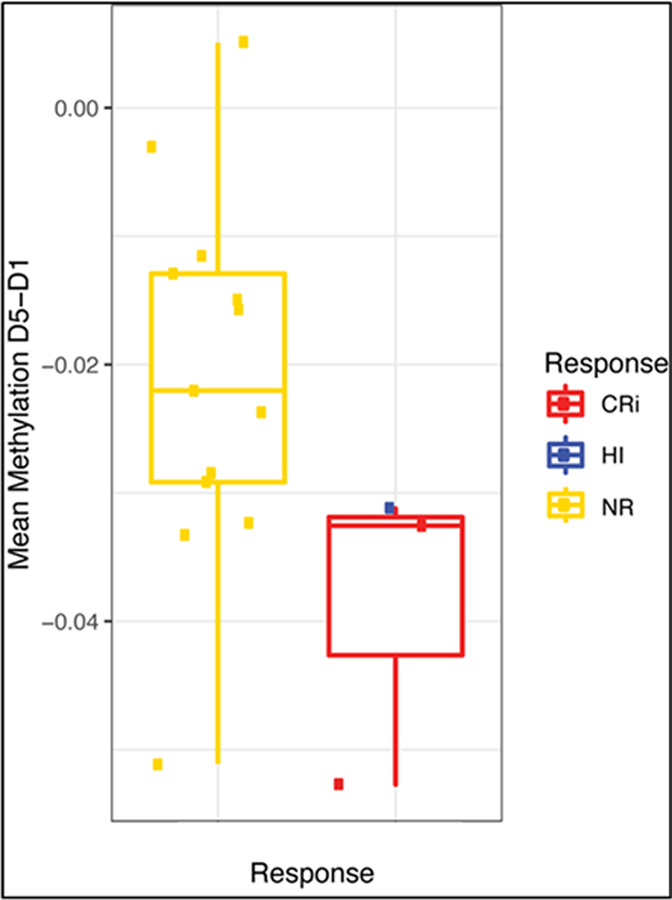

Genome-wide DNA methylation was measured in Cycle 1, Days 1 and 5 samples from 16 patients, including 3 who responded to treatment (2 CRi and one HI) and 13 who did not. A decrease in DNA methylation was found on Day 5, compared to Day 1; moreover, there was a trend toward greater decrease in treatment responders, compared to non-responders, albeit with small patient numbers (p=0.07, two-tailed t-test) (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Decrease in DNA methylation from Day 1 to Day 5 in Cycle 1 in treatment non-responders and responders.

Methylation, measured as described, was compared between Day 5 and Day 1 samples, and changes in methylation were compared between in treatment non-responders and responders. There was a trend toward greater decrease in treatment responders, compared to non-responders, albeit with small patient numbers (p=0.07, two-tailed t-test). CRi = Complete remission with incomplete count recovery; HI = Hematologic improvement; NR = No response.

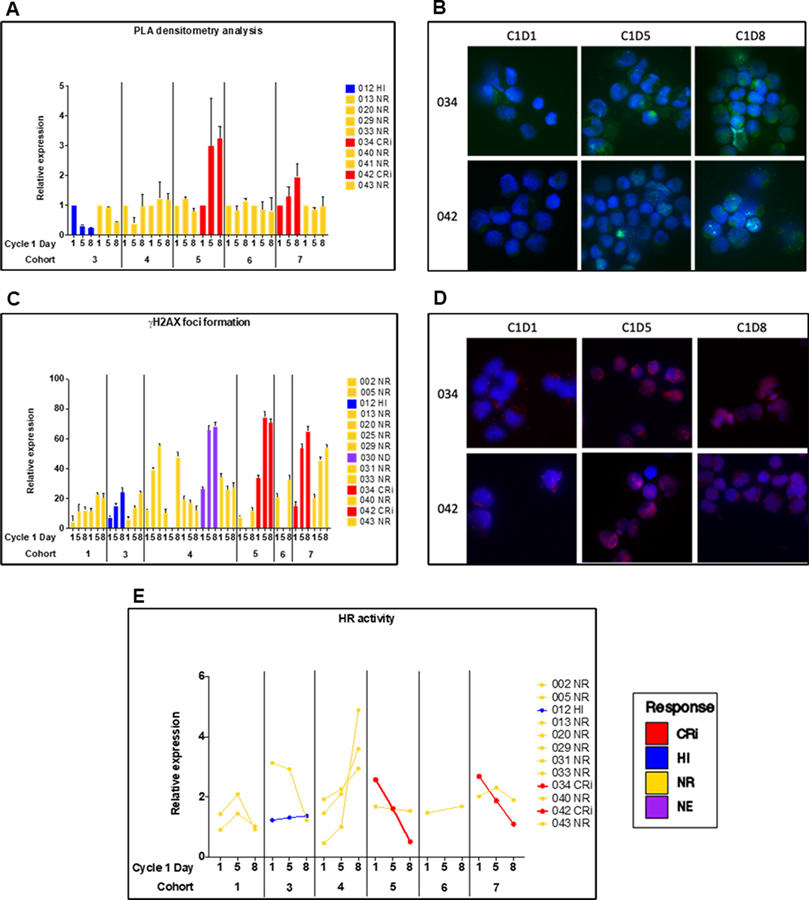

The PLA assay was performed on Cycle 1, Days 1, 5 and 8 samples from ten patients, including two each in Cohorts 3, 4, 5, 6 and 7. There was no statistically significant difference in PARP trapping between Days 5 and 8. Also, there was no statistically significant association between PARP trapping on Day 5 or Day 8 and talazoparib dose in patients treated with 20 mg/m2 decitabine IV X 5 days (Spearman’s rank correlation different from zero; p=0.6 at Day 5 and p=0.24 at Day 8). However, progressive increase in PARP trapping on Days 5 and 8 was seen in cells of Patients 034 and 042, who achieved CRi (Figure 3, A and B).

Figure 3.

Pharmacodynamic studies measuring PARP trapping and DNA damage and repair in samples from patients with Day 1 (pre-treatment) and Day 5 and 8 peripheral blood blasts. A. Proximity ligation assay (PLA) measuring PARP1 trapping at γH2AX foci. B. PLA data in patients who achieved CRi. C. γH2AX foci. D. γH2AX foci in patients who achieved CRi. E. Homologous recombination (HR) activity. CRi = Complete remission with incomplete count recovery; HI = Hematologic improvement; NR = No response; NE = Not evaluable.

Changes in γH2AX foci/cell were measured in 14 patients in Cohorts 1, 3, 4, 5, 6 and 7 (Figure 3C). Baseline levels were variable. A statistically significant increase in γH2AX foci/cell with treatment was seen from Day 1 to Day 5 (p= 0.016) and from Day 1 to Day 8 (p=0.003), and the 1-tailed Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test gave p=0.055 for the increase from Day 5 to Day 8 (Figure 3C). γH2AX expression was found to increase as a function of talazoparib dose in patients treated with 20 mg/m2 decitabine IV X 5 days (Spearman’s rank correlation different from zero; p=0.019) (Supplementary Figure S4). A dose-response analysis testing a possible association between the magnitude of the change within a patient on day 5 minus day 1 versus the dose of talazoparib found a positive association, but not statistically significant, Rs=0.47, p=0.20; a similar analysis of expression on Day 8 minus day 1 gave Rs=0.19, p=0.55. γH2AX foci/cell increased in cells of Patients 034 and 042, who achieved CRi (Figure 3, C and D), and also in some non-responders (Figure 3C). There was some support for an association between γH2AX foci on Day 5 and PARP1 trapping on Day 5 (RS=0.62, p=0.15) and Day 8 (RS=0.82, p=0.023).

HR activity was measured in PB MNC obtained on Days 1, 5 and 8 from 12 patients in Cohorts 1, 3, 4 5, 6 and 7 (Figure 3E). Pre-treatment (Day 1) HR activity was variable. There was no statistically significant change in HR activity between Days 1 and 5, Days 1 and 8, or Days 5 and Day 8. HR activity did decrease from Day 1 to Day 5 to Day 8 in cells of Patient 034 in Cohort 5 and Patient 042 in Cohort 7, both of whom achieved CRi, and also in cells of Patient 013 in Cohort 3, who did not respond to treatment, but not in cells of 7 other patients, one of whom achieved HI and 6 of whom did not respond to treatment.

While correlations are limited by small number of responders, serial samples from Patients 034 and 042, who achieved CRi, showed increase in PARP trapping in the PLA assay (Figure 3A,B), increased γH2AX foci/cell (Figure 3C,D) and decreased HR activity (Figure 3E) with treatment.

RNA sequencing

An overall predominance of pathways showing significant negative enrichment as opposed to positive enrichment was seen. Hallmark pathways analysis showed enrichment for genes that are downregulated in myc- and DNA repair-related pathways in post-treatment samples, compared with pretreatment samples, confirming decreased DNA repair post treatment (Supplementary Figure S5).

DISCUSSION

Based on our preclinical data demonstrating DNMTi enhancement of PARP1 recruitment and tight binding to chromatin (14) and downregulation of HR DNA repair (15), sensitizing cells to PARP inhibitors, we designed and completed a phase I clinical trial of the combination of the DNMTi decitabine and the PARP inhibitor talazoparib in patients with relapsed or refractory AML considered unfit for, or unlikely to respond to, cytotoxic chemotherapy. Doses of both decitabine and talazoparib were successfully escalated in seven cohorts including 25 patients to a recommended phase II dose combination of decitabine 20 mg/m2 intravenously daily for 5 or 10 days and talazoparib 1 mg orally daily for 28 days, in 28-day cycles. Grade 3–5 events included fever in 19 and lung infections in 15, both attributed to AML rather than to drug(s). The response rate to decitabine and talazoparib was low, with incomplete count recovery in two patients (8%) and hematologic improvement in three. Among the 25 patients enrolled on the trial, 22 had been previously treated with the DNMTis decitabine and/or azacitidine.

Importantly, pharmacodynamic studies in responding patients supported the proposed mechanisms of action of decitabine and talazoparib combination treatment, including enhanced PARP1 recruitment and tight binding to chromatin at DNA damage sites and prevention of PARP-mediated DNA repair, resulting in increased cytotoxic DNA DSBs (14), and DNMTi downregulation of HR DSB repair (15,26). Samples from the two patients who achieved CRi showed greater demethylation (samples in red, Figure 2), potentially suggesting greater sensitivity to decitabine. The predicted progressive increase in PARP trapping from pre-treatment (Day 1) to Day 5 to Day 8 of treatment was demonstrated in samples from the two patients who achieved CRi, shown in red in Figure 3A, using the PLA assay. Progressive increase in γH2AX foci from Day 1 to Day 5 to Day 8 was also seen in the two patients who achieved CRi, shown in red in Figure 3C, along with decrease in HR DNA repair activity in these two patients, shown in red in Figure 3E. These data support the proposed mechanism of action of decitabine and talazoparib combination treatment, although limited by the very small number of responders. However, the possibility also exists that the effects seen in the two responders occurred randomly.

We attribute the low response rate in our phase I trial to the fact that 22 of our 25 patients had been previously treated with the DNMTis azacitidine and/or decitabine. This contrasts with patients with solid tumors such as breast/ovarian, who do not receive hypomethylating agents as standard therapy. The amount of prior DNMTi therapy in our patients was variable, ranging from 2 to 40 cycles, with a median of 8 cycles, suggesting both primary and secondary resistance. There was a trend toward more DNA demethylation in patient samples on Day 5, compared to Day 1, in responders, compared to non-responders, albeit with small patient numbers, potentially suggesting greater sensitivity to decitabine in responders. Clinically, lack of response to decitabine following failure of azacitidine, consistent with our data here, has been documented in AML (27), MDS (27,28) and MDS/MPN (28) patients, with no responses in 9 AML patients and stable disease in 5 of 16 patients with MDS or MDS/MPN in our group’s series (27), and marrow CRs in three patients and HI in four among 36 patients with MDS or CMML in the other series (28). Nevertheless, we cannot say with certainty that the responses in our clinical trial were to the decitabine and talazoparib combination, and would not have occurred with decitabine alone.

Given the low response rate in this phase I trial, correlation of response with specific myeloid mutations or classes of mutations (2), including those predicted by preclinical data, is not possible. Nevertheless, it is notable that NPM1, DNMT3A and NRAS mutations were present in blasts of both patients who achieved CRi, while ASXL1, RUNX1 and SRSF2 mutations were present in two of the three patients who achieved HI. These observations suggest possible gene mutation analysis-guided selection of potential “good responders,” as supported by previous work (29).

Some myeloid mutations and cytogenetic changes have been identified as playing a role in PARP inhibitor sensitivity/resistance. Both IDH1/2 (30) and cohesin complex (31) mutations are associated with increased DNA damage and sensitivity to PARP inhibitors. TET2- or WT1-deficient cells rely on PARP1-mediated alternative non-homologous end-joining for DNA DSB repair, while PARP1 is downregulated in DNMT3A-deficient cells, correlating with sensitivity and resistance to PARP inhibitors, respectively (32). In AML with fms-like tyrosine kinase 3 internal tandem duplication (FLT3-ITD), FLT3 inhibitors downregulate DNA repair proteins and sensitize cells to PARP inhibitors (33). Finally, in AML with 3q21q26 chromosomal aberrations, overexpressing the MECOM (EVI1) gene, PARP1 upregulates EVI1 and PARP inhibitors reduce EVI1 expression and are cytotoxic (34). Patient 015, with stable disease through 17 cycles of decitabine and talazoparib therapy, had the t(3;3)(q21;q26) translocation.

We originally planned a phase I/II trial. Based on our phase I results, we would have restricted phase II testing to patients not previously treated with azacitidine or decitabine. However in the interim the Bcl-2 inhibitor venetoclax was found to significantly enhance efficacy of DNMTis in AML across clinical, cytogenetic and molecular subsets (35,36), leading to its FDA approval for this indication. Further testing of talazoparib with decitabine or azacitidine in AML should therefore incorporate venetoclax. Incorporation of venetoclax will require careful dose escalation due to concern for increased hematologic toxicity, though a more effective anti-leukemia regimen would ultimately lead to better hematologic recovery. Of note, the combination of oral decitabine and cedazuridine (ASTX727) and talazoparib is currently undergoing phase I testing in patients with triple-negative breast cancer or hormone-resistant/HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer in another VanAndel Institute - Stand Up to Cancer Epigenetics Dream Team cinical trial.

Supplementary Material

Statement of Translational Relevance.

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) patients unfit for, or resistant to, intensive chemotherapy often receive DNA methyltransferase inhibitors (DNMTis). Novel combinations are being developed to increase efficacy. DNMTis enhance poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP1) recruitment and tight binding to chromatin, preventing PARP-mediated DNA repair, and downregulate homologous recombination (HR) DNA repair, sensitizing cells to PARP inhibitor (PARPi). We previously demonstrated efficacy of DNMTi and PARPi combination in vitro and in vivo. Here we report a phase I clinical trial combining the DNMTi decitabine and the PARPi talazoparib in adults with refractory or relapsed AML. Decitabine and talazoparib were successfully escalated to full doses – 20 mg/m2 intravenously daily for 5 or 10 days and talazoparib 1 mg orally daily for 28 days, respectively, in 28-day cycles. Pharmacodynamic studies demonstrated the expected decreased DNA methylation, increased PARP trapping and γH2AX foci, and decreased HR activity, especially in responding patients.

Acknowledgments

Supported by Leukemia and Lymphoma Society Translational Research Grant TRP5885 (to FVR and MRB), NIH-NCI grant R01CA237311 (to BAY), the Van Andel Research Institute through the Van Andel Research Institute – Stand Up To Cancer Epigenetics Dream Team, NIH-NCI grant P30CA134274 and University of Maryland, Baltimore UMMG Cancer Research Grant #CH 649 CRF issued by the State of Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (DHMH) under the Cigarette Restitution Fund Program. Stand Up To Cancer is a division of the Entertainment Industry Foundation. The grant of the indicated Stand Up To Cancer Dream Team is administered by the American Association for Cancer Research, the Scientific Partner of SU2C.

The authors thank the patients and their families for their participation in the clinical trial, Gary A. E. Saum, B.A., for research coordination and data management, Vu Nguyen, B.S., for assistance with data management and Jean-Pierre Issa, M.D. for helpful discussions.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: F.V.R. and S.B.B. are co-inventors on US Provisional Patent Application Number 61/929,680 for the concept of the combination therapy.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kantarjian HM, Short NJ, Fathi AT, Marcucci G, Ravandi F, Tallman M, et al. Acute myeloid leukemia: Historical perspective and progress in research and therapy over 5 decades. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk 2021;21:580–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Döhner H, Weisdorf DJ, Bloomfield CD. Acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med 2015;373:1136–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jones PA, Taylor SM. Cellular differentiation, cytidine analogs and DNA methylation. Cell 1980;20:85–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kantarjian H, Oki Y, Garcia-Manero G, Huang X, O’Brien S, Cortes J, et al. Results of a randomized study of 3 schedules of low-dose decitabine in higher-risk myelodysplastic syndrome and chronic myelomonocytic leukemia. Blood 2007;109:52–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Steensma DP, Baer MR, Slack JL, Buckstein R, Godley LA, Garcia-Manero G, et al. Multicenter study of decitabine administered daily for 5 days every 4 weeks to adults with myelodysplastic syndromes: the alternative dosing for outpatient treatment (ADOPT) trial. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:3842–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cashen AF, Schiller GJ, O’Donnell MR, DiPersio JF. Multicenter, phase II study of decitabine for the first-line treatment of older patients with acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:556–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lubbert M, Ruter BH, Claus R, Schmoor C, Schmid M, Germing U, et al. A multicenter phase II trial of decitabine as first-line treatment for older patients with acute myeloid leukemia judged unfit for induction chemotherapy. Haematologica 2012;97:393–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kantarjian HM, Thomas XG, Dmoszynska A, Wierzbowska A, Mazur G, Mayer J, et al. Multicenter, randomized, open-label, phase III trial of decitabine versus patient choice, with physician advice, of either supportive care or low-dose cytarabine for the treatment of older patients with newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:2670–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blum W, Garzon R, Klisovic RB, Schwind S, Walker A, Geyer S, et al. Clinical response and miR-29b predictive significance in older AML patients treated with a 10-day schedule of decitabine. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010;107:7473–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ritchie EK, Feldman EJ, Christos PJ, Rohan SD, Lagassa CB, Ippoliti C, et al. Decitabine in patients with newly diagnosed and relapsed acute myeloid leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma 2013;54:2003–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bhatnagar B, Duong VH, Gourdin TS, Tidwell ML, Chen C, Ning Y, et al. Ten-day decitabine as initial therapy for newly diagnosed patients with acute myeloid leukemia unfit for intensive chemotherapy. Leuk Lymphoma 2014;55:1533–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bouligny IM, Mehta V, Isom S, Ellis LR, Bhave RR, Howard DS, et al. Efficacy of 10-day decitabine in acute myeloid leukemia. Leuk Res 2021;103:106524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stahl M, DeVeaux M, Montesinos P, Itzykson R, Ritchie EK, Sekeres MA, et al. Hypomethylating agents in relapsed and refractory AML: outcomes and their predictors in a large international patient cohort. Blood Adv 2018;2:923–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Muvarak NE, Chowdhury K, Xia L, Robert C, Choi EY, Cai Y, et al. Enhancing the cytotoxic effects of PARP inhibitors with DNA demethylating agents - A potential therapy for cancer. Cancer Cell 2016;30:637–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abbotts R, Topper MJ, Biondi C, Fontaine D, Goswami R, Stojanovic L, et al. DNA methyltransferase inhibitors induce a BRCAness phenotype that sensitizes NSCLC to PARP inhibitor and ionizing radiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2019;116:22609–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McLaughlin LJ, Stojanovic L, Kogan AA, Rutherford JL, Choi EY, Yen RC, et al. Pharmacologic induction of innate immune signaling directly drives homologous recombination deficiency. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2020;117:17785–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kohl V, Flach J, Naumann N, Brendel S, Kleiner H, Weiss C, et al. Antileukemic efficacy in vitro of talazoparib and APE1 inhibitor III combined with decitabine in myeloid malignancies. Cancers (Basel) 2019;11:1493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de Bono J, Ramanathan RK, Mina L, Chugh R, Glaspy J, Rafii S, et al. Phase I, dose-escalation, two-part trial of the PARP inhibitor talazoparib in patients with advanced germline BRCA1/2 mutations and selected sporadic cancers. Cancer Discov 2017;7:620–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Litton JK, Rugo HS, Ettl J, Hurvitz SA, Gonçalves A, Lee KH, et al. Talazoparib in patients with advanced breast cancer and a germline BRCA mutation. N Engl J Med 2018;379:753–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mufti GJ, Estey E, Popat R, Mattison R, Menne T, Azar J, et al. Results of a phase 1 study of BMN 673, a potent and specific PARP-1/2 inhibitor, in patients with advanced hematological malignancies. Haematologica 2014;99(suppl 1):33–4. [Google Scholar]

- 21.<v/>Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, Jaffe ES, Pileri SA, Stein H, et al. , editors. WHO classification of tumours of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues. Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2008. p. 109–38. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cheson BD, Bennett JM, Kopecky KJ, Büchner T, Willman CL, Estey EH, et al. International Working Group for Diagnosis, Standardization of Response Criteria, Treatment Outcomes, and Reporting Standards for Therapeutic Trials in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Revised recommendations of the International Working Group for Diagnosis, Standardization of Response Criteria, Treatment Outcomes, and Reporting Standards for Therapeutic Trials in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. J Clin Oncol 2003;21:4642–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cheson BD, Greenberg PL, Bennett JM, Lowenberg B, Wijermans PW, Nimer SD, et al. Clinical application and proposal for modification of the International Working Group (IWG) response criteria in myelodysplasia. Blood 2006;108:419–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fortin JP, Triche TJ Jr, Hansen KD. Preprocessing, normalization and integration of the Illumina HumanMethylationEPIC array with minfi. Bioinformatics 2017;33:558–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ritchie ME, Phipson B, Wu D, Hu Y, Law CW, Shi W, et al. limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res 2015;43:e47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tsai HC, Li H, Van Neste L, Cai Y, Robert C, Rassool FV, et al. Transient low doses of DNA-demethylating agents exert durable antitumor effects on hematological and epithelial tumor cells. Cancer Cell 2012;21:430–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Duong VH, Bhatnagar B, Zandberg DP, Vannorsdall EJ, Tidwell ML, Chen Q, et al. Lack of objective response of myelodysplastic syndromes and acute myeloid leukemia to decitabine after failure of azacitidine. Leuk Lymphoma 2015;56:1718–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harel S, Cherait A, Berthon C, Willekens C, Park S, Rigal M, et al. Outcome of patients with high risk myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) and advanced chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML) treated with decitabine after azacitidine failure. Leuk Res 2015;39:501–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nieborowska-Skorska M, Sullivan K, Dasgupta Y, Podszywalow-Bartnicka P, Hoser G, Maifrede S, et al. Gene expression and mutation-guided synthetic lethality eradicates proliferating and quiescent leukemia cells. J Clin Invest 2017;127:2392–2406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Molenaar RJ, Radivoyevitch T, Nagata Y, Khurshed M, Przychodzen B, Makishima H, et al. IDH1/2 mutations sensitize acute myeloid leukemia to PARP inhibition and this is reversed by IDH1/2-mutant inhibitors. Clin Cancer Res 2018;24:1705–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tothova Z, Valton AL, Gorelov RA, Vallurupalli M, Krill-Burger JM, Holmes A, et al. Cohesin mutations alter DNA damage repair and chromatin structure and create therapeutic vulnerabilities in MDS/AML. JCI Insight 2021;6:e142149.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maifrede S, Le BV, Nieborowska-Skorska M, Golovine K, Sullivan-Reed K, Dunuwille WMB, et al. TET2 and DNMT3A mutations exert divergent effects on DNA repair and sensitivity of leukemia cells to PARP inhibitors. Cancer Res 2021;81:5089–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maifrede S, Nieborowska-Skorska M, Sullivan-Reed K, Dasgupta Y, Podszywalow-Bartnicka P, Le BV, et al. Tyrosine kinase inhibitor-induced defects in DNA repair sensitize FLT3(ITD)-positive leukemia cells to PARP1 inhibitors. Blood 2018;132:67–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kiehlmeier S, Rafiee MR, Bakr A, Mika J, Kruse S, Müller J, et al. Identification of therapeutic targets of the hijacked super-enhancer complex in EVI1-rearranged leukemia. Leukemia 2021; 35:3127–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.DiNardo CD, Jonas BA, Pullarkat V, Thirman MJ, Garcia JS, Wei AH, et al. Azacitidine and venetoclax in previously untreated acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med 2020;383:617–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.DiNardo CD, Maiti A, Rausch CR, Pemmaraju N, Naqvi K, Daver NG, et al. 10-day decitabine with venetoclax for newly diagnosed intensive chemotherapy ineligible, and relapsed or refractory acute myeloid leukaemia: a single-centre, phase 2 trial. Lancet Haematol 2020;7:e724–e736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data generated in this study are not publicly available as information could compromise patient privacy, but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.