Abstract

Objective:

Cardiac ischemia during daily life is associated with an increased risk for adverse outcomes. Mental stress is known to provoke cardiac ischemia and is related to psychological variables. In this multicenter cohort study, we assessed whether psychological characteristics were associated with ischemia in daily life.

Methods:

This study examined patients with clinically stable coronary artery disease (CAD) with documented cardiac ischemia during treadmill exercise (N=196, mean age = 62.64, SD = 8.31 years; 13% women). Daily life ischemia (DLI) was assessed by 48-hour ambulatory ECG monitoring. Psychological characteristics were assessed using validated instruments to identify characteristics associated with ischemia occurring in daily life stress.

Results:

High scores on anger and hostility were common in this sample of patients with CAD and DLI was documented in 83 (42%) patients. However, the presence of DLI was associated with lower anger scores (OR 2.03; 95% CI, 1.12–3.69), reduced anger expressiveness (OR 2.04; 95% CI, 1.10–3.75), and increased ratio of anger control to total anger (OR 2.33; 95% CI, 1.27–4.17). Increased risk for DLI was also associated with lower hostile attribution (OR 2.22; 95% CI, 1.21–4.09), hostile affect (OR 1.92; 95% CI, 1.03–3.58), and aggressive responding (OR 2.26; 95% CI, 1.25–4.08). We observed weak inverse correlations between DLI episode frequency and anger expressiveness, total anger, and hostility scores. DLI was not associated with depression or anxiety measures. The combination of the constructs low anger expressiveness and low hostile attribution was independently associated with DLI (OR=2.59; 95% CI, 1.42–4.72

Conclusion:

In clinically stable patients with CAD, the tendency to suppress angry and hostile feelings, particularly openly aggressive behavior was associated with DLI. These findings warrant study in larger cohorts and intervention studies are needed to ascertain whether management strategies that modify these psychological characteristics improve outcomes.

Keywords: Anger, Coronary Disease, Hostility, Ischemia

Introduction

Cardiac ischemia during daily life (DLI), most of which is asymptomatic or unrecognized by patients with coronary artery disease (CAD), has been associated with an increased risk of adverse outcomes[1–5]. In the Psychophysiological Investigations in Myocardial Ischemia (PIMI) project, mental stress ischemia predicted increased mortality risk[4], which was confirmed in a subsequent meta-analysis[5]. Substantial cross-sectional and prospective epidemiological research has long suggested that certain emotions and behaviors may be associated with ischemic heart disease (IHD). Specifically, hostility and depression have been associated with an increased risk for CAD events[6]. Both acute arousal and hostility have been linked to sudden cardiac death and myocardial infarction (MI)[7,8]. Moreover, evidence suggests that anger suppression (versus anger expression) is linked to increased carotid arterial stiffness and subclinical CAD[9,10].

Likewise, substantial evidence has linked certain psychological constructs and the interpersonal conflict model to CAD. Patients within the high hostility and social defensiveness construct exhibited greater perfusion defects with exercise, higher severity of coronary obstructions, more frequent ischemia on ambulatory monitoring, and the most severe mental stress-induced myocardial ischemia (MSMI) [11,12]. In some studies, the combination of high defensiveness and high hostility predicted greater cardiovascular disease risk. In others, high defensiveness in combination with low hostility trait/anxiety predicted greater heart rate stress reactivity[11,12]. Thus, the role of a psychological profile characterized by subsets of hostility and anger in the manifestations of ambulatory silent DLI requires further investigation.

More recently, among women with suspected ischemia and no obstructive CAD, psychological stress was associated with CAD risk factors and symptoms[13]. There is also growing interest in mental stress-induced cardiac ischemia as a marker of cardiovascular vulnerability to emotional stress[14,15]. Ambulatory electrocardiographic (AECG) analysis reveals asymptomatic ischemia in patients with MSIMI. In contrast, exercise testing does not appear to differentiate patients who experience ischemic abnormalities during daily life stressors on AECG[16]. Additionally, in younger patients with CAD, MSIMI is associated with angina frequency[17] and more than doubling of risk for major adverse cardiovascular events, including mortality[5]. The ability of such mental stressors to induce ischemia is impressive as those stressors used in laboratory studies are usually shorter in duration and less intense than real-life psychological stressors.

Hence, the psychological and physiological characteristics of ischemia-susceptible patients and links between these characteristics and ischemia occurring during daily life situations are still not well-defined. Investigation of these links was one goal of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute-sponsored PIMI project[16]. The current study was designed to investigate relationships between patients’ psychological characteristics, identified by psychological testing and DLI during AECG monitoring.

Methods

The PIMI study was conducted between 1998 and 2002. Its protocol has been described in detail elsewhere[16] and essential features are summarized below. Each institutional review committee for the protection of human subjects approved the protocol, and each patient gave written informed consent before study participation.

Patients Selection Criteria

Clinically stable patients were eligible if they had: 1) evidence of CAD, based upon either a coronary angiogram showing ≥50% diameter reduction in at least one major artery or documented prior MI; 2) had an ischemic ECG response during treadmill exercise; and 3) were without cardiac or neuropsychiatric medications during 48-hour AECG monitoring. Exclusions included age >80 years, pregnancy, MI within three months, percutaneous coronary intervention within six months, previous thoracotomy, unstable angina, other serious illness, neurologic disease, ECG abnormalities known to interfere with ST-segment analysis, and the need for digitalis, psychotropic drugs, antidepressants, sympatholytics, angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors, central acting α-agonists, analgesics, β-blockers or corticosteroids. Patients qualified when the above criteria were satisfied, and their ischemic exercise ECG response was confirmed by ECG Core Laboratory review to be ≥1 mm horizontal or downsloping ST-segment depression from the baseline that persisted in at least 3-consecutive complexes.

Clinical and AECG Assessment

The site physician-investigator and study coordinator reviewed the objectives and procedures with the patient. Clinical evaluation included baseline demographic data, a physical exam, an assessment of historical factors that included chest pain (Rose Questionnaire)[11] and angina (Anginal Syndrome Questionnaire)[18] and a neurologic examination. All clinical data were obtained at protocol-scheduled visits using standardized forms. Evaluation for DLI was done by AECG monitoring using two 24-hour recordings from two leads. Techniques used for monitoring and criteria for assessing ischemia from these recordings have been published[19]. A DLI episode was defined by AECG Core Laboratory review of the AECG as a period with horizontal or downsloping ST-segment shift ≥1 mm from the baseline that persisted for ≥1 minute.

Psychological and Mental Stress Assessment

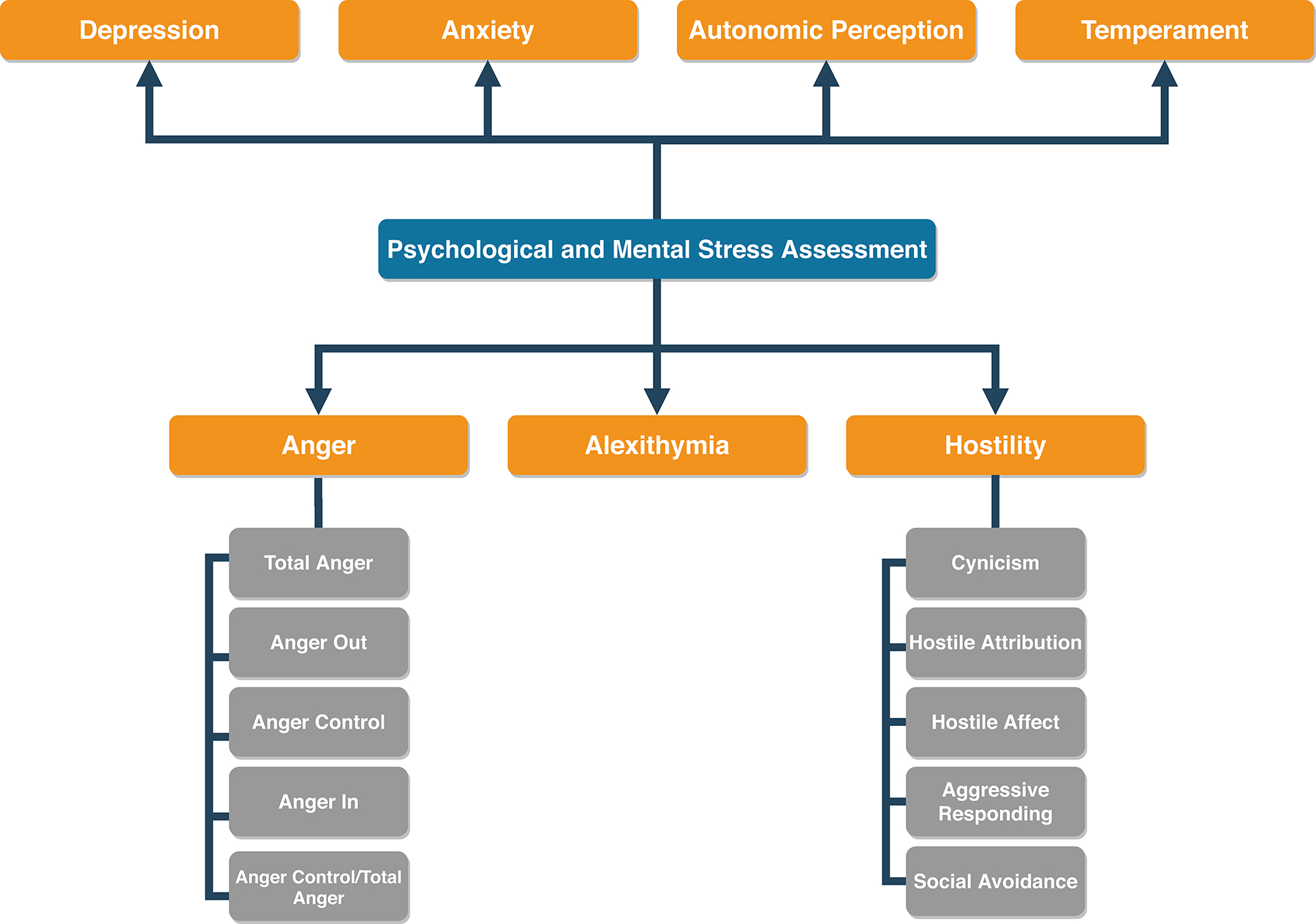

Psychological data were collected through self-administered questionnaires using previously validated instruments. As one primary goal of PIMI was to evaluate psychosocial domains predictive of the occurrence and symptomatic expression of ischemia provoked by exercise and mental stress in patients with CAD, we explored associations between each psychologic measure and DLI. Conceptually, we initially assumed that all of these measures could increase the risk for DLI and therefore intended to explore these associations.

Furthermore, many studies evaluated components of type A behavior among patients with CAD[20,21]. The most pathogenic features were a combination of aggravation, irritation, anger, and impatience or also referred to as hostility. These form the critical core components of measures of emotional distress in many patients with CAD. Also, preliminary evidence demonstrated that patients with the combined construct of high hostility and social desirability “defensive hostile” had the greatest perfusion defects as measured by exercise testing[22]. Similarly, a psychological profile characterized by hostility, anger, and emotional reactivity has been associated with an increased risk of MI and sudden death[23]. Additionally, patients with such psychologic profile and CAD tend to underreport symptoms during provocative testing and appear less likely to experience angina during exercise testing[24]. Hence, we sought to explore hypothetical constructs of combinations of anger and hostility subsets to determine the role of such psychological profiles and their relationship with silent ambulatory DLI. We hypothesized that participants with evidence of silent ischemia during daily life might be distinguished by certain psychological measures and a psychological profile of combinations of anger and hostility subsets (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Daily Life Ischemia Model: an Analysis from the Psychophysiological Investigations in Myocardial Ischemia (PIMI).

Cardiac ischemia during daily life is a predictor of adverse outcomes that include increased all-cause mortality. The pathophysiologic mechanisms responsible for ischemia during daily life are complex and usually multifactorial. Increases in myocardial oxygen demand with limitations in myocardial oxygen delivery are overarching concepts. Evidence for increased sympathetic nervous system activation (both central and cardiac), obstructive atherosclerotic plaque, coronary microvascular dysfunction, and vasospasm are well documented, often in combination, within most cases with daily life ischemia. Accordingly, we hypothesized that certain psychophysiological signals are key in ischemia during daily life, and they arise from the combination of a number of stressors. These involve anger, depression, anxiety, among many others. This current analysis found that a key independent predictor was a combination of constructs relating to low anger expressiveness and low hostile attribution.

Abbreviations: MVO2, Myocardial oxygen consumption; MO2, Myocardial Oxygen.

All psychological measures had excellent internal consistency. These included measures of depression (Beck Depression Inventory; Cronbach’s α = 0.91)[25,26], anxiety (Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory; Cronbach’s α >0.80)[27,28], anger (Spielberger Anger Expression; Cronbach’s α >0.86)[29], hostility (Cook-Medley Hostility Scale; Cronbach’s α = 0.86)[30,31], alexithymia (Toronto Alexithymia Scale; Cronbach’s α = 0.76)[32,33], a modified autonomic perception questionnaire (Cronbach’s α = 0.83–0.89)[34–37], and a temperament character inventory (harm-avoidance, reward-dependence, and novelty-seeking; Cronbach’s α = 0.74–0.82)[38,39].

Components of hostility included subsets derived by Barefoot et al. from the Cook-Medley Hostility Scale[19]. They were: cynicism (13-items), reflecting negative beliefs about trustworthiness or qualities of people in general (e.g., “I think that most people would lie to get ahead”); hostile attribution (12-items), reflecting suspicion that others intend to harm the respondent (e.g., “I tend to be on my guard with people that are more friendly than I had expected”); hostile affect (5-items), admissions of negative emotions concerning others (e.g., “Some of my family have habits that bother and annoy me very much”); aggressive responding (9-items), reflecting a tendency to use or endorse aggression when coping with problems (e.g., “I have at times had to be rough with people who were rude or annoying”); and social avoidance (4-items), reflecting a preference to withdraw from social contact (e.g., “No one cares that much about you”).

The components of anger were derived from the anger expression scale developed by Spielberger et al. [29]. In addition to total anger, subscales related to “anger out” (tendency to express anger verbally or physically) and “anger control” (efforts to control angry feelings and reactions by avoiding verbal or physical aggression (e.g., “I control my behavior” and “I try to be tolerant and understanding”). Anger control was also expressed as a proportion of total anger (i.e., anger control ratio) by the ratio of anger control score/total anger score. “Anger in” is the tendency to hold in or suppress angry feelings (e.g., “I boil inside, but I do not show it” and “I am angrier than I am willing to admit”) (Figure 1).

Figure 1:

Summary of psychological and mental stress assessment methods. Psychological data were collected through self-administered questionnaires using previously validated measures.

Statistical Analysis

Baseline characteristics were summarized as means, medians, or percentages where appropriate. We used Chi-Square and Wilcoxon rank tests to assess differences between categorical and continuous variables. Each patient was categorized according to the presence or absence of DLI based on the AECG Core Laboratory analysis by staff, who were masked to all other patient data. To account for variation in the total number of hours of recording over two days of ambulatory monitoring, the total number of ischemic episodes was adjusted for the total recording duration and expressed as the number of ischemic episodes per 24 hours. Spearman rank correlation coefficients were used to examine the relationship between psychological test scores of hostility and anger.

Univariate analysis of the relationship between DLI and clinical, historical, and psychological characteristic scores determined the prevalence of DLI in patients with each characteristic present or absent. For psychological characteristics, the prevalence of DLI was compared between those scoring low (<median) and high (>median) because of skewed (non-normal) score distributions of the psychological measures. Baseline variables passing this preliminary screen at P-value <0.10 were considered in a stepwise multivariate logistic regression analysis. Thereafter, based on the univariate model results and the correlation coefficients matrix, we created several hypothetical constructs for exploring combinations of two measures (anger and hostility) associated with DLI that were also entered into the multivariate analysis. These constructs used the four possible combinations of patients having low (<median) and high (>median) scores on the measures of interest. To assess for collinearity, we used the correlation coefficients matrix and the ‘COLLIN’ option in SAS to evaluate collinearity diagnostics[40,41]. The odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated for both the univariate and multivariate models and a P-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were done using SAS version-9.4.

Results

Data were available for all 196 patients, with an age range of 41–80 years. The majority were men (87%), most had a history of chest pain (83%), and 36% reported symptoms consistent with angina within the previous three months. DLI was detected by AECG in 83 patients (42%); 34 of these had one ischemic episode, and 49 had two or more ischemic episodes/24-hours. Pertinent patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1. History of prior MI was marginally less prevalent in patients with DLI vs. no DLI (32% VS 67%; P = 0.058); other elements of the history did not predict DLI. Interestingly, DLI was not associated with exercise-induced chest pain, any angina, or angina occurring during the previous three months (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline Patient Characteristics and Daily Life Ischemia (DLI)*

| Total | No DLI | DLI | P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 196 | 113 (58) | 83 (42) | |

| Demographic | ||||

| Age (years) | ||||

| (41–49) | 17 (8.7) | 8 (7.1) | 9 (10.8) | 0.15 |

| (50–59) | 47 (24) | 31 (27.4) | 16 (19.3) | |

| (60–69) | 92 (47) | 47 (41.6) | 45 (54.2) | |

| (70–80) | 40 (20.4) | 27 (23.9) | 13 (15.7) | |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 170 (86.7) | 98 (86.7) | 72 (86.7) | 0.99 |

| Female | 26 (13.3) | 15 (13.3) | 11 (13.3) | |

| Race | ||||

| White | 171 (87.2) | 96 (85.0) | 75 (90.4) | 0.26 |

| Other | 25 (12.8) | 17 (15.0) | 8 (9.6) | |

| BMI (Kg/m2) | 28.9 ± 11 | 29.9 ± 13.9 | 27.5 ± 4.1 | 0.096 |

| Medical History | ||||

| Diabetes | 29 (14.8) | 17 (15.0) | 12 (14.5) | 0.97 |

| History of Smoking | 145 (78) | 79 (69.9) | 66 (79.5) | 0.13 |

| Alcohol | 128 (65.3) | 73 (64.6) | 55 (66.3) | 0.81 |

| Heart Failure | 6 (3.1) | 3 (2.7) | 3 (3.6) | 0.70 |

| Myocardial Infarction | 83 (42.4) | 56 (49.6) | 27 (32.5) | 0.058 |

| Hypertension | 93 (47.5) | 54 (47.8) | 39 (47.0) | 0.97 |

| Chest Pain | ||||

| Rose Questionnaire† | 163 (83.2) | 95 (84.1) | 68 (81.9) | 0.69 |

| Angina‡ | 70 (36) | 42 (37.2) | 28 (33.7) | 0.62 |

| Symptoms on QV, AECG or ETT§ | 106 (54.1) | 62 (54.9) | 44 (53.0) | 0.80 |

| Angina on ETT¶ | 90 (46) | 55 (48.7) | 35 (42.2) | 0.37 |

| Psychologic Measures | ||||

| CMS | 20.0 ± 8.43 | 21.3 ± 8.40 | 18.2 ± 8.20 | 0.011 |

| CYN | 6.9 ± 3.07 | 7.17 ± 3.00 | 6.5 ± 3.22 | 0.13 |

| HOSTATT | 4.0 ± 2.63 | 4.4 ± 2.71 | 3.5 ± 2.43 | 0.017 |

| HOSTAFF | 1.9 ± 1.41 | 2.2 ± 1.50 | 1.7 ± 1.30 | 0.014 |

| AGGRESS | 3.6 ± 1.75 | 3.8 ± 1.80 | 3.3 ± 1.70 | 0.037 |

| SOCAVOID | 1.3 ± 1.00 | 1.5 ± 1.00 | 1.2 ± 0.92 | 0.088 |

| HOST Other | 2.2 ± 1.40 | 2.3 ± 1.40 | 2.0 ± 1.40 | 0.14 |

| AXOUT | 14.0 ± 3.62 | 14.4 ± 4.00 | 13.1 ± 3.00 | 0.008 |

| AXIN | 15.3 ± 3.83 | 15.5 ± 4.00 | 14.9 ± 3.61 | 0.26 |

| AXCON | 25.8 ± 4.97 | 25.2 ± 5.21 | 26.6 ± 4.50 | 0.053 |

| AX | 19.3 ± 9.40 | 20.8 ± 10.45 | 17.4 ± 7.31 | 0.009 |

| AXRATIO | 0.36 ± 0.10 | 0.35 ± 0.11 | 0.38 ± 0.09 | 0.045 |

Abbreviations: AGGRESS, Aggressive Responding; AX, Anger; AXCON, Anger Control; AXIN, Anger In; AXOUT, Anger Expressiveness; AXRATIO, Anger Control Ratio; BMI, Body Mass Index (Kg/m2); CI, Confidence Interval; CMS, Cook Medley Hostility Scale; CYN, Cynicism; DLI, Daily Life Ischemia; ETT, Treadmill Exercise Testing; HOSTAFF, Hostile Affect; HOSTATT, Hostility Attribution; HOST, Hostility; N, Number; OR, Odds Ratio; QV, Qualifying Visit; SD, Standard Deviation; SOCAVOID, Social Avoidance.

Data are expressed as N (%) or as mean ± Standard Deviation.

History of chest pain ever from Rose Questionnaire.

History of angina in three previous months.

Symptoms compatible with angina based on history, during AECG monitoring, or ETT at qualifying visit.

Angina reported during qualifying visit.

When psychologic scores were assessed, patients with DLI had lower scores on the hostility scale (18.2 vs. 21.3) (P = 0.011) attributable to the following subsets: hostile attribution (3.5 vs. 4.4) (P = 0.017), hostile affect (1.7 vs. 2.2) (P = 0.014), and aggressive responding (3.3 vs. 3.8) (P = 0.037), compared to patients without DLI. Similarly, compared to patients without DLI, patients with DLI scored lower on the total anger scale (17.4 vs. 20.8) (P = 0.009) and the subscale of anger expressiveness, measuring tendencies to express anger outwardly (13.1 vs. 14.4) (P = 0.008). Conversely, patients with DLI had a slightly higher anger control (25.2 vs. 26.6) (P = 0.053) and anger control ratio (0.35 vs. 0.38) (P = 0.045) (Table1). No other psychological test differences were found comparing scores of those with and without DLI (Table S1, Supplemental Digital Content).

In the anger and hostility correlation matrix, all inter-correlations were statistically significant, but the r values were moderate, suggesting these measures reflect some, but not all, of the same aspects of coping with anger (Table 2). When assessing various constructs using combinations of anger and hostility scores, 55% of the patients identified with low (<median) anger expressiveness and low hostile attribution had DLI. In the univariate analysis, this construct remained the best predictor of DLI in those <median age as well as those >median age (data not shown).

Table 2.

Spearman’s Correlation Coefficients (r values) between psychological Measures of Hostility (HOST) and Anger (AX)

| Median Score ± IQR | HOSTATT | HOSTAFF | AGGRESS | AXOUT | AXIN | AXCON | AX | AXRATIO | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hostility Attribution (HOSTATT) | 4.0 (4.0) | 1.00 | |||||||

| Hostile Affect (HOSTAFF | 2.0 (2.0) | 0.54 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Aggressive Responding (AGGRESS) | 3.0 (3.0) | 0.44 | 0.44 | 1.00 | |||||

| Anger Out (AXOUT) | 14.0 (5.0) | 0.31 | 0.32 | 0.45 | 1.00 | ||||

| Anger In (AXIN) | 15.0 (4.0) | 0.33 | 0.40 | 0.33 | 0.26* | 1.00 | |||

| Anger Control (AXCON) | 26.5 (7.0) | −0.30 | −0.40 | −0.32 | −0.51 | −0.24† | 1.00 | ||

| Anger (AX) | 19.0 (14.0) | 0.45 | 0.51 | 0.49 | 0.75 | 0.63 | −0.82 | 1.00 | |

| Anger Control Ratio (AXRATIO) | 1.4 (2.0) | −0.42 | −0.49 | −0.45 | −0.70 | −0.54 | 0.90 | −0.98 | 1.00 |

All P < 0.001, except * = 0.0004, and † = 0.0007. Median score represents the median score of the psychological measure in the corresponding row.

Abbreviations: AGGRESS, Aggressive Responding; AX, Anger; AXCON, Anger Control; AXIN, Anger In; AXOUT, Anger Out; AXRATIO, Anger Control Ratio; HOSTAFF, Hostile Affect; HOSTATT, Hostility Attribution; IQR, Interquartile Range (estimated 25% in both directions of the median)

Similarly, in the univariate logistic regression analysis, only prior MI was associated with lower risk of DLI (OR 0.49; 95% CI, 0.27–0.88) (P = 0.020); other elements of the history did not predict DLI. When assessing psychological scores categorically, univariate logistic regression analysis identified elevated risk for DLI to be associated with low (<median) scores on the total anger scale (OR 2.03; 95% CI, 1.12– 3.69) (P = 0.020), and the anger expressiveness subscale (OR 2.04; 95% CI, 1.10–3.75) (P = 0.020), (Table 3). Contrariwise, reduced risk for DLI was associated with low (<median) scores on anger control (OR 0.52; 95% CI, 0.29–0.93) (P = 0.030), and the anger control ratio (OR 0.43; 95% CI, 0.24– 0.79) (P = 0.005). For hostility measures, increased risk for DLI was also associated with low hostile attribution (OR 2.22; 95% CI, 1.21–4.09) (P = 0.010), hostile affect (OR 1.92; 95% CI, 1.03–3.58) (P = 0.040), and aggressive responding (OR 2.26; 95% CI, 1.25–4.08) (P = 0.006) scores. All other psychological scores did not predict DLI.

Table 3.

Univariate Analysis of Patient Psychological Characteristics and Daily Life Ischemia (DLI)*

| Total | No DLI | DLI | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 196 | 113 | 83 | |||

| Beck | ||||||

| ≤4 | 102 | 56 (50.0) | 46 (55.4) | 1.27 | 0.72–2.24 | 0.42 |

| >4 | 94 | 57 (50.0) | 37 (44.6) | |||

| CMS | ||||||

| ≤20 | 107 | 55 (48.7) | 52 (62.6) | 1.77 | 0.99–3.15 | 0.060 |

| >20 | 89 | 58 (51.3) | 31 (37.4) | |||

| CYN | ||||||

| ≤7 | 109 | 60 (53.0) | 49 (59.0) | 1.27 | 0.72–2.26 | 0.46 |

| >7 | 87 | 53 (47.0) | 34 (41.0) | |||

| HOSTATT | ||||||

| ≤4 | 121 | 61 (54.0) | 60 (72.3) | 2.22 | 1.21–4.09 | 0.010 |

| >4 | 75 | 52 (46.0) | 23 (27.7) | |||

| HOSTAFF | ||||||

| ≤2 | 130 | 68 (60.2) | 62 (74.7) | 1.92 | 1.03–3.58 | 0.040 |

| >2 | 66 | 45 (39.8) | 21 (25.3) | |||

| AGGRESS | ||||||

| ≤3 | 104 | 50 (44.2) | 54 (65.1) | 2.26 | 1.25–4.08 | 0.006 |

| >3 | 92 | 63 (55.8) | 29 (34.9) | |||

| SOCAVOID | ||||||

| ≤1 | 121 | 65 (57.5) | 56 (67.5) | 1.53 | 0.85–2.77 | 0.17 |

| >1 | 75 | 48 (42.5) | 27 (32.5) | |||

| HOST Other | ||||||

| ≤2 | 128 | 69 (61.1) | 59 (71.1) | 1.57 | 0.86–2.88 | 0.17 |

| >2 | 68 | 44 (38.9) | 24 (28.9) | |||

| AXOUT | ||||||

| ≤14 | 122 | 62 (54.9) | 60 (72.3) | 2.04 | 1.10–3.75 | 0.020 |

| >14 | 74 | 51 (45.1) | 23 (27.7) | |||

| AXIN | ||||||

| ≤15 | 111 | 60 (53.1) | 51 (61.4) | 1.41 | 0.79–2.51 | 0.31 |

| >15 | 85 | 53 (46.9) | 32 (38.6) | |||

| AXCON | ||||||

| ≤26.5 | 101 | 65 (57.5) | 36 (43.4) | 0.52 | 0.29–0.93 | 0.030 |

| >26.5 | 95 | 48 (42.5) | 47 (56.6) | |||

| AX | ||||||

| ≤19 | 112 | 56 (49.6) | 56 (67.5) | 2.03 | 1.12– 3.69 | 0.020 |

| >19 | 84 | 57 (50.4) | 27 (32.5) | |||

| AXRATIO | ||||||

| ≤1.42 | 97 | 65 (57.5) | 32 (38.6) | 0.43 | 0.24– 0.79 | 0.005 |

| >1.42 | 99 | 48 (42.5) | 51 (61.4) |

Abbreviations: AGGRESS, Aggressive Responding; AX, Anger; AXCON, Anger Control; AXIN, Anger In; AXOUT, Anger Expressiveness; AXRATIO, Anger Control Ratio; CI, Confidence Interval; CMS, Cook Medley Hostility Scale; CYN, Cynicism; DLI, Daily Life Ischemia; HOSTAFF, Hostile Affect; HOSTATT, Hostility Attribution; HOST, Hostility; N, Number; SOCAVOID, Social Avoidance.

Data are expressed as N (%); psychological test scores are expressed as ≤ or > the median group score; P-value from univariate logistic regression analysis comparing low (<median) vs. high (>median) scores.

Multivariate stepwise regression analysis, where variables with P-value≤0.1 from the univariate analysis were allowed to enter the model and stay, identified history of MI and higher aggression score as associated with lower risk of DLI, while higher anger control ratio was associated with lower risk of DLI (Table 4, Model 1). There was no significant interaction between DLI and age (Pinteraction=0.9). When the various combinations of anger and hostility scores were added to the model, however, the low anger expressiveness-low hostility attribution construct was the only independent predictor of risk for DLI (OR 2.59; 95% CI, 1.42–4.72) (P = 0.002), compared to the other three constructs of anger expressiveness and hostility attribution (Table 4, Model 2).

Table 4.

Multivariable Stepwise Logistic Regression Odds Ratios for Daily Life Ischemia

| Odds Ratio | 95% CI | P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | |||

| Aggression Score >3 | 0.53 | 0.28–0.99 | 0.004 |

| Anger Control Ratio >1.42 | 1.80 | 0.96–3.35 | 0.067 |

| History of Myocardial Infarction | 0.49 | 0.27–0.90 | 0.024 |

| Model 2 | |||

| Low Anger Expressiveness & Low Hostility Attribution | 2.59 | 1.42–4.72 | 0.002 |

| History of Myocardial Infarction | 0.55 | 0.30–1.01 | 0.054 |

CI, Confidence Interval

Discussion

In this study, we explored associations between psychological characteristics and DLI in patients participating in the PIMI project. We hypothesized that certain psychological variables and/or constructs, namely anger, and hostility, would be associated with ischemia during the stressors occurring throughout daily life in susceptible patients. PIMI had a cohort of clinically stable CAD patients with evidence of functionally severe CAD that was capable of resulting in exercise-induced ischemia. Interestingly, we observed that risk for DLI was about two-fold higher among patients with lower total anger and anger expressiveness scores. The risk for DLI was halved in patients with lower anger control scores.

Ischemia occurring during daily life results from increased cardiac oxygen demand and limited cardiac oxygen supply related to the overall functional severity of CAD. The latter includes the anatomic severity of the obstructive CAD and disordered reactivity of the larger coronary arteries and coronary microcirculation and downstream functional implications for the myocardium[2]. While mental stressors have been shown to provoke ischemia and coronary artery constriction in certain individuals, our understanding of psychological features that increase certain patients’ susceptibility to mental stress is incomplete[42,43]. The precise mechanisms for the association between mental stress-induced ischemia and adverse outcomes are unclear. Prior evidence indicates that mental stress can cause coronary vasoconstriction, increased heart rate-blood pressure product, resulting in increased myocardial oxygen demand-supply mismatch[44]. Other evidence includes abnormal vasomotion secondary to endothelial dysfunction[45], sympathetic nervous system activation with exaggerated peripheral microvascular tone[46], and vasoconstriction of even normal-appearing coronary artery segments[47].

Average hostility scale scores of patients participating in PIMI as a group are very high, as usually observed in a CAD population[48]. Thus, the cohort we studied would be expected to have relatively frequent experiences of anger and hostility. Although hostility scores of patients participating in PIMI who experienced DLI were lower than hostility scores of patients who did not experience ischemia, they were high compared with the general population’s mean hostility scores. These data also indicate that lower hostility subscales, specifically hostile attribution, hostile affect, and aggressive responding, are associated with elevated risk for DLI. Remarkably, DLI was neither associated with depression nor anxiety measures in these patients without overt psychiatric illness requiring the continuation of medications. The construct that includes suppressed hostility and anger expression is an important independent risk factor for DLI as found in the multivariate analysis. The latter construct appears related, at least in part, to efforts to control hostile or angry feelings and reactions by avoiding the open expression of irritation and aggression.

Previous reports indicate that differences between the frequency of anger self-reported by patients with CAD and by an individual they choose as “someone who knows you well” (e.g., spouse/friend) are common and generally in the direction of more anger being reported by the spouse/friend[49]. Such differences may be due to “denial” by the patient and have been suggested to predict ischemia-related outcome events (death, myocardial infarction, or revascularization) at five years follow-up[49]. Accordingly, the possibility that our patients’ under-reported anger must be entertained. Such a propensity could be motivated by the stigma associated with such behavior or other factors not yet understood. Unfortunately, information on the importance of denial became available after PIMI was designed, so ratings of the anger level displayed by the patient could not be obtained from significant others. However, our results of high “suppressed anger” and low self-reported hostility are consistent with this possibility.

As discussed, our results suggest that anger control and suppressed hostility patterns are associated with a high risk for DLI but not with anger in, anxiety, or depression. The hostility attribution subscale is a measure of the cognitive component of hostility, reflecting the patient’s suspicion that others intend to do harm. These patients, with a tendency to extend an effort to control angry feelings and behaviors, may be more at risk for the conditions underlying DLI and its association with adverse outcomes than those who hold feelings of anger in, express them outwardly, withdraw, or harbor grudges (Figure 2). The significance of the associations with DLI, a marker for functionally severe CAD and increased risk of adverse outcomes[1–3], and the psychological profile we observed is underscored by a reported association between hostility subscales with rapid atherosclerosis progression[50]. Several long-term follow-up studies had demonstrated that high levels of hostility were associated with an elevated risk of adverse cardiovascular outcomes and vice versa[51]. Also, previous studies examining the relationship between hostility and DLI found that high levels of hostility were associated with a greater duration of DLI [52], and CAD with subtle differences between men and women.[53] Higher CAD risk was conferred with indirect expression of antagonism in women and overt expression of anger in men.[53] Additionally, anger expression style predicted the development of hypertension over 4-years of follow-up in initially normotensive men[54].

Whether constructive or destructive, the type of anger expression is known to play a role in CAD progression. Among individuals followed for 10-years, constructive anger expression was associated with a lower risk of incident CAD (hazard ratio [HR] 0.58; 95% CI, 0.43–0.80; P <0.001), only in men[22]. The same was not true for destructive anger expression (HR 1.31; 95%CI, 1.03–1.67; P =0.03)[22]. Thus, the type of anger might have a role in our study, where low expression of constructive anger by our predominantly male cohort might have led to more severe CAD and DLI. Lastly, some treatments have been suggested to modify relationships of ischemia with anger to reduce acute events. Antianxiety psychotherapy and medications may reduce DLI, and antidepressants could have a favorable risk/benefit profile in IHD[55,56]. These drugs, if indicated, must be used with caution, considering possible side effects.

Some limitations of our study should be noted. First, the sample size was relatively small, short (48-hours) AECG monitoring time due to patients’ burden, fewer women, and patients were selected to have CAD plus exercise-induced ischemia. Our results may differ with other selection criteria. Second, the lower hostility scores of patients showing DLI could reflect a survival effect, namely that the most vulnerable patients (those whose hostility was most toxic) may already have died, thus tending to lower the mean score of this subgroup. The data illustrate uncertainties inherent in extrapolating from longitudinal studies in a general population and cross-sectional data (i.e., PIMI) from a selected population or specific patients. Interestingly, it’s also worth noting that a prior PIMI mortality study showed no association between mortality rates among patients participating in PIMI and psychological characteristics (depression, anxiety, or anger) that have been reported to predict cardiac events[11]. Third, the finding that prior MI was associated with reduced risk for DLI in the univariate analysis suggests that those without MI may have more functional myocardium at risk to develop DLI than those with a prior MI. Nevertheless, the low hostility and low anger expressiveness construct was significantly associated with DLI after adjusting for history of prior MI in the multivariate analysis. Fourth, we did not obtain diary information that would have enabled assessing the perception of anger while the AECG was recorded. A detailed diary might have helped to determine whether anger was provoked or suppressed during daily life situations that were associated with ischemia. Additionally, we used stepwise regressions that may not be universally preferred. Finally, mechanisms through which psychological factors affect the development of chronic atherosclerosis, chronic ischemia, and related adverse outcomes, including myocardial dysfunction[2] may be different from those affecting acute ischemia. Thus, it is extremely important to better understand the long-term associations among psychological profiles, the presence of ischemia, and clinical outcomes.

Among a cohort of patients with clinically stable CAD, those enrolled in PIMI had high hostility scores, as usually observed in CAD populations[48]. Thus, these patients would be expected to experience anger and hostility relatively frequently. Nonetheless, those with DLI have lower scores of hostility, total anger, and anger expressiveness than those without DLI. Of these patients, those who suppressed such feelings more often tended to have a larger number of DLI episodes, perhaps secondary to the cardiovascular effects of suppressed emotional arousal. These findings appear to be related to high anger control and a low tolerance toward open expression and aggression. Our results extend previous observations to support suggestions that anger and hostility are important independent variables that interact with processes modulating the functional severity of IHD. Screening for mental stress and stress expression during routine cardiac outpatient evaluation may help control residual angina in patients with stable IHD on optimal medical therapy. The clinical importance of these findings warrants further investigation in a larger study with a prospective design to modify these psychological constructs.

Supplementary Material

Disclosures:

Osama Dasa; Ahmed N. Mahmoud; Peter G. Kaufmann; Mark Ketterer; Kathleen C. Light; James Raczynski; David Sheps; Peter H. Stone; Eileen Handberg have nothing to disclose.

Carl J. Pepine reports funding from the National Institute of Health (NIH)/ National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute N01-HV-91–05R01; R01HL146158 01, R01HL090957; NIH/National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences UL1 TR001427; United States Department of Defense

W811XWH-17-2-0300; the McJunkin Family Foundation Trust; and the Gatorade Trust.

This work was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute through contracts

HV 18114, HV 18119, HV 18120, HV 18121, and HV 28127. Criticon Corporation provided automated blood pressure monitoring equipment. Support for electrocardiographic data collections was provided, in part, by Applied Cardiac Systems, Laguna Hills, California; Marquette Electronics, Milwaukee, Wisconsin; Mortara Instruments, Milwaukee, Wisconsin; and Quinton Instruments, Seattle, Washington.

Abbreviations:

- AECG

Ambulatory Electrocardiogram

- DLI

Daily Life Ischemia

- CAD

Coronary Artery Disease

- CI

Confidence Interval

- ECG

Electrocardiogram

- HR

Hazard Ratio

- IHD

Ischemic Heart Disease

- OR

Odds Ratio

- PIMI

Psychophysiological Investigations in Myocardial Ischemia

- MSIMI

Mental Stress-Induced Myocardial Ischemia

References

- 1.Pepine CJ, Sharaf B, Andrews TC, Forman S, Geller N, Knatterud G, Mahmarian J, Ouyang P, Rogers WJ, Sopko G, Steingart R, Stone PH, Conti CR. Relation between clinical, angiographic and ischemic findings at baseline and ischemia-related adverse outcomes at 1 year in the asymptomatic cardiac ischemia pilot study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997. Jun 1;29(7):1483–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pepine CJ, Petersen JW, Bairey Merz CN. A microvascular-myocardial diastolic dysfunctional state and risk for mental stress ischemia: A revised concept of ischemia during daily life. Vol. 7, JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging. Elsevier Inc.; 2014. p. 362–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gill JB, Cairns JA, Roberts RS, Costantini L, Sealey BJ, Fallen EF, Tomlinson CW, Gent M. Prognostic Importance of Myocardial Ischemia Detected by Ambulatory Monitoring Early after Acute Myocardial Infarction. N Engl J Med. 1996. Jan 11;334(2):65–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sheps DS, McMahon RP, Becker L, Carney RM, Freedland KE, Cohen JD, Sheffield D, Goldberg AD, Ketterer MW, Pepine CJ, Raczynski JM, Light K, Krantz DS, Stone PH, Knatterud GL, Kaufmann PG. Mental stress-induced ischemia and all-cause mortality in patients with coronary artery disease: Results from the Psychophysiological Investigations of Myocardial Ischemia study. Circulation. 2002. Apr 16;105(15):1780–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wei J, Rooks C, Ramadan R, Shah AJ, Bremner JD, Quyyumi AA, Kutner M, Vaccarino V. Meta-analysis of mental stress-induced myocardial ischemia and subsequent cardiac events in patients with coronary artery disease. In: American Journal of Cardiology. Elsevier Inc.; 2014. p. 187–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vaccarino V, Badimon L, Bremner JD, Cenko E, Cubedo J, Dorobantu M, Duncker DJ, Koller A, Manfrini O, Milicic D, Padro T, Pries AR, Quyyumi AA, Tousoulis D, Trifunovic D, Vasiljevic Z, de Wit C, Bugiardini R. Depression and coronary heart disease: 2018 position paper of the ESC working group on coronary pathophysiology and microcirculation. Eur Heart J. 2019. Jan 28; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chida Y, Steptoe A. The Association of Anger and Hostility With Future Coronary Heart Disease. A Meta-Analytic Review of Prospective Evidence. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009. Mar 17;53(11):936–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Todaro JF, Con A, Niaura R, Spiro A, Ward KD, Roytberg A. Combined effect of the metabolic syndrome and hostility on the incidence of myocardial infarction (The Normative Aging Study). Am J Cardiol. 2005. Jul 15;96(2):221–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Matthews KA, Owens JF, Kuller LH, Sutton-Tyrrell K, Jansen-McWilliams L. Are hostility and anxiety associated with carotid atherosclerosis in healthy postmenopausal women? Psychosom Med. 1998;60(5):633–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anderson JC, Linden W, Habra ME. Influence of apologies and trait hostility on recovery from anger. J Behav Med. 2006. Aug 15;29(4):347–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jorgensen RS, Abdul-Karim K, Kahan TA, Frankowski JJ. Defensiveness, Cynical Hostility and Cardiovascular Reactivity: A Moderator Analysis. Psychother Psychosom. 1995;64(3–4):156–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Larson MR, Langer AW. Defensive hostility and anger expression: Relationship to additional heart rate reactivity during active coping. Psychophysiology. 1997. Mar;34(2):177–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gomez MA, Bairey Merz CN, Eastwood J, Pepine CJ, Handberg EM, Bittner V, Mehta PK, Krantz DS, Vaccarino V, Eteiba W, Rutledge T. Psychological stress, cardiac symptoms, and cardiovascular risk in women with suspected ischemia but no obstructive coronary disease (INOCA). Stress Health. 2020. Jan 20; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arri SS, Ryan M, Redwood SR, Marber MS. Mental stress-induced myocardial ischaemia. Heart. 2016. Mar 1;102(6):472–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wokhlu A, Pepine CJ. Mental Stress and Myocardial Ischemia: Young Women at Risk. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016. Sep 24;5(9). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaufmann PG, McMahon RP, Becker LC, Bertolet B, Bonsall R, Chaitman B, Cohen JD, Forman S, Goldberg AD, Freedland K, Ketterer MW, Krantz DS, Pepine CJ, Raczynski J, Stone PH, Taylor H, Knatterud GL, Sheps DS. The psychophysiological investigations of myocardial ischemia (PIMI) study: Objective, methods, and variability of measures. Psychosom Med. 1998;60(1):56–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pimple P, Shah AJ, Rooks C, Douglas Bremner J, Nye J, Ibeanu I, Raggi P, Vaccarino V. Angina and mental stress-induced myocardial ischemia. J Psychosom Res. 2015. May 1;78(5):433–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Greene AF, Schocken DD, Spielberger CD. Self-report of chest pain symptoms and coronary artery disease in patients undergoing angiography. Pain. 1991;47(3):319–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pepine CJ, Geller NL, Knatterud GL, Bourassa MG, Chaitman BR, Davies RF, Day P, Deanfield JE, Goldberg AD, McMahon RP, Mueller H, Ouyang P, Pratt C, Proschan M, Rogers WJ, Selwyn AP, Sharaf B, Sopko G, Stone PH, Conti CR. The Asymptomatic Cardiac Ischemia Pilot (ACIP) study: Design of a randomized clinical trial, baseline data and implications for a long-term outcome trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1994;24(1):1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Friedman M, Powell LH, Thoresen CE, Ulmer D, Price V, Gill JJ, Thompson L, Rabin DD, Brown B, Breall WS, Levy R, Bourg E. Effect of discontinuance of type A behavioral counseling on type A behavior and cardiac recurrence rate of post myocardial infarction patients. Am Heart J. 1987. Sep 1;114(3):483–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Friedman M, Thoresen CE, Gill JJ, Ulmer D, Powell LH, Price VA, Brown B, Thompson L, Rabin DD, Breall WS, Bourg E, Levy R, Dixon T. Alteration of type A behavior and its effect on cardiac recurrences in post myocardial infarction patients: Summary results of the recurrent coronary prevention project. Am Heart J. 1986. Oct 1;112(4):653–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Davidson KW, Mostofsky E. Anger expression and risk of coronary heart disease: Evidence from the Nova Scotia Health Survey. Am Heart J. 2010. Feb;159(2):199–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dembroski TM, MacDougall JM, Costa PT, Grandits GA. Components of hostility as predictors of sudden death and myocardial infarction in the Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial. Psychosom Med. 1989. Oct;51(5):514–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Siegel WC, Hlatky MA, Mark DB, Barefoot JC, Harrell FE, Pryor DB, Williams RB. Effect of Type A behavior on exercise test outcome in coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol. 1990. Jul 15;66(2):179–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beck AT, Steer RA, Carbin MG. Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory: Twenty-five years of evaluation. Clin Psychol Rev. 1988. Jan 1;8(1):77–100. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. BDI-II. Beck Depression Inventory. 2nd ed. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vagg PR, Spielberger CD. State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory™ Interpretive Report (STAXI-2: IR™) Client Information Name: Sample Client. 1986.

- 28.Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RL, Lushene RE. State-Trait Anxiety (STAI) Manual. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Spielberger CD, Johnson EH, Russell SF, Crane RJ, Jacobs GA, & Worden TJ. The experience and expression of anger: Construction and validation of an anger expression scale. In: Chesney MA, Rosenman RH Ed, editor. Anger and hostility in cardiovascular and behavioral disorders. Washington DC: Hemisphere Publishing Corp; 1985. p. 5–30. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barefoot JC, Dodge KA, Peterson BL, Dahlstrom WG, Williams RB. The Cook-Medley hostility scale: Item content and ability to predict survival. Psychosom Med. 1989;51(1):46–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cook WW, Medley DM. Proposed hostility and Pharisaic-virtue scales for the MMPI. J Appl Psychol. 1954;38(6):414–8. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sifneos PE, Apfel-Savitz R, Frankel FH. The phenomenon of “alexithymia”. Observations in neurotic psychosomatic patients. Psychother Psychosom. 1977;28(1–4):47–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Taylor GJ, Bagby RM, Ryan DP, Parker JD. Validation of the alexithymia construct: a measurement-based approach. Can J Psychiatry Rev Can Psychiatr. 1990. May;35(4):290–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Freedland KE, Carney RM, Krone RJ, Case NB, Case RB. Psychological determinants of anginal pain perception during exercise testing of stable patients after recovery from acute myocardial infarction or unstable angina pectoris. Am J Cardiol. 1996. Jan 1;77(1):1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Freedland KE, Carney RM, Krone RJ, Smith LJ, Rich MW, Eisenkramer G, Fischer KC. Psychological factors in silent myocardial ischemia. Psychosom Med. 1991;53(1):13–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mandler G, Mandler JM, Uviller ET. Autonomic feedback: The perception of autonomic activity. J Abnorm Soc Psychol. 1958;56(3):367–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shields SA, Simon A. Is Awareness of Bodily Change in Emotion Related to Awareness of Other Bodily Processes? J Pers Assess. 1991. Aug 1;57(1):96–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Otter C, Huber J, Bonner A. Cloninger’s Tridimensional Personality Questionnaire: Reliability in an english sample. Personal Individ Differ. 1995. Apr 1;18(4):471–80. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Garcia D, Lester N, Cloninger KM, Robert Cloninger C. Temperament and Character Inventory (TCI). In: Zeigler-Hill V, Shackelford TK, editors. Encyclopedia of Personality and Individual Differences [Internet]. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2017. [cited 2021 Jul 29]. p. 1–3. Available from: 10.1007/978-3-319-28099-8_91-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Collinearity in regression: The COLLIN option in PROC REG [Internet]. The DO Loop. [cited 2021 Aug 4]. Available from: https://blogs.sas.com/content/iml/2020/01/23/collinearity-regression-collin-option.html

- 41.Collinearity diagnostics: Should the data be centered? [Internet]. The DO Loop. [cited 2021 Aug 4]. Available from: https://blogs.sas.com/content/iml/2020/01/29/collinearity-diagnostics-centering.html

- 42.Buckley T, Hoo SYS, Fethney J, Shaw E, Hanson PS, Tofler GH. Triggering of acute coronary occlusion by episodes of anger. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2015. Dec 1;4(6):493–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mostofsky E, Penner EA, Mittleman MA. Outbursts of anger as a trigger of acute cardiovascular events: a systematic review and meta-analysis†. Eur Heart J. 2014. Mar 3;35(21):1404–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Krantz DS, Burg MM. Current Perspective on Mental Stress–Induced Myocardial Ischemia. Psychosom Med. 2014. Apr;76(3):168–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sherwood A, Johnson K, Blumenthal JA, Hinderliter AL. Endothelial Function and Hemodynamic Responses During Mental Stress. Psychosom Med. 1999. Jun;61(3):365–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Myocardial Ischemia During Mental Stress: Role of Coronary Artery Disease Burden and Vasomotion | Journal of the American Heart Association [Internet]. [cited 2021 Aug 5]. Available from: https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/full/10.1161/JAHA.113.000321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Arrighi JA, Burg M, Cohen IS, Kao AH, Pfau S, Caulin-Glaser T, Zaret BL, Soufer R. Myocardial blood-flow response during mental stress in patients with coronary artery disease. The Lancet. 2000. Jul 22;356(9226):310–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Barefoot JC, Dahlstrom WG, Williams RB. Hostility, CHD incidence, and total mortality: A 25-year follow-up study of 255 physicians. Psychosom Med. 1983;45(1):59–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ketterer MW, Huffman J, Lumley MA, Wassef S, Gray L, Kenyon L, Kraft P, Brymer J, Rhoads K, Lovallo WR, Goldberg AD. Five-year follow-up for adverse outcomes in males with at least minimally positive angiograms: Importance of “denial” in assessing psychosocial risk factors. J Psychosom Res. 1998. Feb;44(2):241–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wong JM, Na B, Regan MC, Whooley MA. Hostility, health behaviors, and risk of recurrent events in patients with stable coronary heart disease: findings from the Heart and Soul Study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2013. Sep 30;2(5):e000052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Haukkala A, Konttinen H, Laatikainen T, Kawachi I, Uutela A. Hostility, anger control, and anger expression as predictors of cardiovascular disease. Psychosom Med. 2010;72(6):556–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Player MS, King DE, Mainous AG, Geesey ME. Psychosocial factors and progression from prehypertension to hypertension or coronary heart disease. Ann Fam Med. 2007. Sep;5(5):403–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Siegman AW, Townsend ST, Civelek AC, Blumenthal RS. Antagonistic behavior, dominance, hostility, and coronary heart disease. Psychosom Med. 2000. Apr;62(2):248–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kubzansky LD, Park N, Peterson C, Vokonas P, Sparrow D. Healthy psychological functioning and incident coronary heart disease: The importance of self-regulation. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011. Apr;68(4):400–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Piña IL, Di Palo KE, Ventura HO. Psychopharmacology and Cardiovascular Disease. Vol. 71, Journal of the American College of Cardiology. Elsevier; USA; 2018. p. 2346–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jiang W, Velazquez EJ, Kuchibhatla M, Samad Z, Boyle SH, Kuhn C, Becker RC, Ortel TL, Williams RB, Rogers JG, O’Connor C. Effect of escitalopram on mental stress-induced myocardial ischemia: Results of the REMIT trial. JAMA - J Am Med Assoc. 2013. May 22;309(20):2139–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.