Abstract

Imaging applications tailored towards ultrasound-based treatment, such as high intensity focused ultrasound (FUS), where higher power ultrasound generates a radiation force for ultrasound elasticity imaging or therapeutics/theranostics, are affected by interference from FUS. The artifact becomes more pronounced with intensity and power. To overcome this limitation, we propose FUS-net, a method that incorporates a CNN-based U-net autoencoder trained end-to-end on ‘clean’ and ‘corrupted’ RF data in Tensorflow 2.3 for FUS artifact removal. The network learns the representation of RF data and FUS artifacts in latent space so that the output of corrupted RF input is clean RF data. We find that FUS-net perform 15% better than stacked autoencoders (SAE) on evaluated test datasets. B-mode images beamformed from FUS-net RF shows superior speckle quality and better contrast-to-noise (CNR) than both notch-filtered and adaptive least means squares filtered RF data. Furthermore, FUS-net filtered images had lower errors and higher similarity to clean images collected from unseen scans at all pressure levels. Lastly, FUS-net RF can be used with existing cross-correlation speckle-tracking algorithms to generate displacement maps. FUS-net currently outperforms conventional filtering and SAEs for removing high pressure FUS interference from RF data, and hence may be applicable to all FUS-based imaging and therapeutic methods.

Keywords: autoencoder, CNN, deep learning, elastography, filtering, FUS, HIFU artifact, theranostics, therapeutics, U-Net

I. INTRODUCTION

FOCUSED ultrasound (FUS) is at the core of many ultrasonic imaging and therapeutic techniques. For example, various conditions can be treated using FUS ablation of the tissue, requiring precise positioning and imaging [1]. In many cases, ultrasound B-mode images are used to dynamically monitor therapy in-procedure. Additionally, the acoustic radiation force produced by a highly focused FUS transducer or imaging transducer can induce remote palpations, noninvasively probing the tissue. Ultrasound-based elasticity techniques use both high-frame rate images and radiation force to evaluate tissue elasticity for tissue characterization [2]– [4] or therapy monitoring [5], [6]. However, many of these techniques involve simultaneous FUS and imaging applications where simultaneous operation typically poses imaging challenge due to FUS-generated interference artifacts.

The artifact itself is caused by overlap and interference between the FUS and imaging beam. Especially at high FUS intensities, interference within the imaging transducer’s receive bandwidth creates artificial bright speckle in the B-mode images [7]. The FUS artifact appears at the center frequency and the harmonics, depending on the sensitivity of the imaging transducer bandwidth. Since the FUS pulse can be orders longer than an imaging pulse, the artifact can corrupt the entire RF data stack. Conventionally, the artifact can be mitigated through a combination of filters [8]. In Harmonic Motion Imaging, interference is removed through multiple notch filters or through low and high pass filters to retain only the central imaging frequency [2]. This, however, removes frequency information often degrading B-mode quality and the structure of speckle. More complex techniques that have been proposed as alternatives, such as adaptive filtering [9] or pulse inversion [10], requires changes to the transmit-receive scheme which may not be possible or may be time-consuming and inflexible in conventional clinically-available ultrasound systems.

Autoencoder networks have the capability to learn the underlying distribution or representative latent space of a given dataset. They involve using an encoder that maps input space to feature space, and a decoder that maps from feature space back to input space. All together, the autoencoder produces a reconstruction that attempts to minimize the reconstruction error [11]. Applications include, but are not limited to, image segmentation [12], image super resolution [13], anomaly detection [14], and image noise reduction [15]. The network is typically composed of a bottleneck that limits the amount of information that can propagates through the network, forcing the autoencoder to reconstruct the input with little redundancy. A specific autoencoder, the U-Net, has had recent success over traditional autoencoders through the addition of skip connections, which helps facilitate passing and concatenating textural information down the network to minimize reconstruction error. As a result, unique applications, such as removing ocean discoloration from underwater images have been invented [16].

The proposed objective of this study was to evaluate the usage of autoencoder networks to effectively eliminate FUS interference. FUS-net, a modified U-Net, reduces corrupted RF data to a latent space and reconstructs without FUS interference. We first compared the reconstruction performance of FUS-net against SAEs and then against conventional notch and state-of-the-art adaptive least means square (LMS) filtering. Lastly, we examined how conventional elastography estimation techniques performs on the network output. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first application of a convolutional U-Net autoencoder to FUS interference reduction.

II. PROPOSED ARCHITECTURE

The FUS artifact strongly corrupts the imaging frequency spectrum - seen as a large amplitude periodic signal in all transducer-element receive signal. In order to learn the latent representation of this artifact and remove it from the signal, we present FUS-net: a U-Net architecture comprised of CNN downsampling and upsampling layers. The proposed architecture is shown in Fig. 1. The input to the network is RF data from a single plane wave transmit (at various angles) and receive acquisition, with or without FUS interference. Symmetric filters (32, 64, 128, 256, 512 down; 512, 256, 128, 64, 32 up) were used to downsample and upsample the RF data. The downsampling layer is composed of 2 convolutional layers followed by a batched norm layer. Each convolutional layer uses a kernel size of 4×4 and even padding with zeros since input MxN dimensions are even. In Table II, the first convolutional layer uses strides of 1×1 to maintain input size with the addition of filters, the second convolutional layer in the downsampling or upsampling (Sequential) layer uses a stride of 2×2. The sequential layers were defined as a sequence of a strided down or upsampling layer, a batched normalization layer, a dropout layer (upsampling only), and an activation layer. The first three downsampling layers and all of the upsampling layers utilize a batched normalization layer. The upsampling layer takes in a concatenated input of the previous layer with its corresponding skip connection to two convolutional layers of the reversed filter order which are fed into a dropout layer, set to 30% dropout, before an activation layer. Lastly, all downsampling and upsampling layers use a leaky ReLu activation to mitigate the vanishing gradient. Since the input is not a square image as in conventional implementations of U-Nets, only 5 iterations of resampling was performed to ensure consistent dimensions; the deepest latent layer was reduced from a dimension size of [128 × 896 × 1] to [4 × 28 × 512]. The network output [128 × 896 × 1] and the ground truth RF data without FUS interference [128 × 896 × 1] was used to calculate the loss and update the weights. In this study, the weights were updated based on the loss, the structural similarity index (SSIM), and the multiscale structural similarity index (MS-SSIM) [17].

Fig. 1.

FUS-net autoencoder architecture for RF FUS filtering. The encoding (downsampling - red arrows) layers are displayed in blue and the decoding (upsampling - blue arrows) layers are indicated in gray. Skip connections and concatenations are indicated by green arrows. Filter sizes are indicated on the bottom and data dimension sizes are indicated at the top.

TABLE II.

FUS-NET PARAMETERS (FUNCTIONAL MODEL)

| Layer (type) | Output Shape | Param # | Connected to |

|---|---|---|---|

| input1 (InputLayer) | (None, 128, 896, 1) | 0 | |

| conv2d1 (Conv2D) | (None, 128, 896, 32) | 512 | input 1 |

| sequential1 (Sequential) | (None, 64, 448, 32) | 16512 | conv2d1 |

| conv2d2 (Conv2D) | (None, 64, 448, 64) | 32768 | sequential 1 |

| sequential2 (Sequential) | (None, 32, 224, 64) | 65792 | conv2d2 |

| conv2d3 (Conv2D) | (None, 32, 224, 128) | 131072 | sequential 2 |

| sequential3 (Sequential) | (None, 16, 112, 128) | 262656 | conv2d3 |

| conv2d4 (Conv2D) | (None, 16, 112, 128) | 524288 | sequential 3 |

| sequential4 (Sequential) | (None, 8, 56, 256) | 1048576 | conv2d4 |

| conv2d5 (Conv2D) | (None, 8, 56, 512) | 2097152 | sequential 4 |

| sequential5 (Sequential) | (None, 4, 28, 512) | 4194304 | conv2d5 |

| sequential6 (Sequential) | (None, 8, 56, 512) | 4196352 | sequential 5 |

|

concatenate1 (Concate- nate) |

(None, 8, 56, 768) | 0 | sequential6, sequential4 |

| conv2d6 (Conv2D) | (None, 8, 56, 512) | 6291456 | concat 1 |

| sequential7 (Sequential) | (None, 16, 112, 256) | 2098176 | conv2d6 |

|

concatenate2 (Concate- nate) |

(None, 16, 112, 384) | 0 | sequential7, sequential3 |

| conv2d7 (Conv2D) | (None, 16, 112, 256) | 1572864 | concat 2 |

| sequential8 (Sequential) | (None, 32, 224, 128) | 524800 | conv2d7 |

|

concatenate3 (Concate- nate) |

(None, 32, 224, 192) | 0 | sequential8, sequential2 |

| conv2d8 (Conv2D) | (None, 32, 224, 128) | 393216 | concat 3 |

| sequential9 (Sequential) | (None, 64, 448, 64) | 131328 | conv2d8 |

|

concatenate4 (Concate- nate) |

(None, 64, 448, 96) | 0 | sequential9, sequential1 |

| conv2d9 (Conv2D) | (None, 64, 448, 64) | 98304 | concat 4 |

| conv2d10 (Conv2D) | (None, 64, 448, 32) | 32768 | conv2d9 |

|

conv2dTrans1 (Conv2DTranspose) |

(None, 128, 896, 1) | 513 | conv2d10 |

| Total: 23,713,409 |

A stacked autoencoder network was used as a comparison to the optimal FUS-net architecture in this study and had the same input and loss calculation. The overall network was comprised of 3 downsampling layers and 3 upsampling layers of convolution with filter size 32, 64, and 128. The layers consisted of one convolutional layer followed by a max pooling layer to downsample or upsample. This specific SAE architecture performed better than a SAE with similar downsampling (strided convolutions instead of maxpooling) and upsampling layers and filters in FUS-net. The overall parameters and network summary for both networks can be found in Tables I and II.

TABLE I.

STACKED AUTOENCODER PARAMETERS (SEQUENTIAL MODEL)

| Layer (type) | Output Shape | Param # |

|---|---|---|

| input1 (InputLayer) | [(None, 128, 896, 1)] | 0 |

| conv2d1 (Conv2D) | (None, 128, 896, 32) | 320 |

| maxpool1 (MaxPooling2D) | (None, 64, 448, 32) | 0 |

| conv2d2 (Conv2D) | (None, 64, 448, 128) | 36992 |

| maxpool2 (MaxPooling2D) | (None, 32, 224, 128) | 0 |

| conv2dtrans1 (Conv2DTranspose) | (None, 32, 224, 128) | 147584 |

| upsample1 (UpSampling2D) | (None, 64, 448, 128) | 0 |

| conv2dtrans2 (Conv2DTranspose) | (None, 64, 448, 32) | 36896 |

| upsample2 (UpSampling2D) | (None, 128, 896, 32) | 0 |

| conv2d3 (Conv2D) | (None, 128, 896, 1) | 289 |

| Total: 222,081 |

III. MATERIALS AND METHOD

A. Dataset

The proposed network was trained and evaluated with 15,190 pairs of clean and artifact RF data acquired from mouse (n = 20) and human tissues (n = 2 volunteers) using a research vantage machine (Vantage-256, Verasonics, Bothell, WA, USA). The dataset is comprised of a total of 443 different views of the mouse sciatic nerve (longitudinal orientation) and the human median nerve (cross-sectional orientation)1. Additionally, 16 scans were acquired in a 5.5 kPa tissue mimicking phantom as a separate ”unseen” test set. All scans were acquired by placing the transducer system on a mechanical 3D positioner. All RF data was acquired with a 128 element, 18 MHz linear array transducer (L22–14vXL, Vermon, France).

Coherent compounding plane wave RF data was recorded with a 5 ms window surrounding a 1 ms FUS pulse at a PRF of 5 kHz and 5 angles (± 1° increments) [5]. Individual RF frames were then split and separated into data sets of 128 elements x 896 time sample arrays with and without FUS interference. To achieve greater deep-learning training performance, alternative images of the same structure (rotations, mirroring, shearing, and lighting) can be used to introduce variety in the dataset. To accomplish a similar task, we used different sonication angles, providing the network with the ability to generalize to various interference patterns and the flexibility for implementation regardless of angle. A 4-MHz, single-element FUS transducer was used to generate the FUS sonication and interference at derated pressures 1.3 to 31 MPa in mice and up to 20 MPa in humans. Particular attention was towards ensuring FUS artifact data was collected immediately after or before ground truth data at high frame-rates, under the assumption that tissue movement is minimal and subsequent speckle patterns between artifact and ground truth images are the same (minus the FUS artifact).

1). Animal Data:

Wild-type C57BL6 mice were anesthetized with isoflurane and their hind limbs were dehaired before applying degassed ultrasound gel. The transducer system (Fig. 2) was positioned above the hind limb and centered on the sciatic nerve. FUS exposure was equal to 1 to 2 ms and a range of peak positive pressures from 0 to 31 MPa peak positive were explored. Both left and right legs were imaged so that different orientations of the tissue were introduced into the data set. In total, 11330 sets of RF were used for both training and test sets.

Fig. 2.

Experimental dual-transducer setup. The FUS transducer emits a focal pulse at the center of the imaging transducer window. The imaging bandwidth of the receive is shown at the bottom and the generated RF stacks are on the right. B-mode images were beamformed using delay-and-sum. The example image is of the median nerve.

2). Human Data:

FUS RF data from human muscle and nerve tissue was acquired for greater generalization to different tissue types and eventual clinical translation. Exposure was limited to the subject by employing 1 – 2 ms pulses and limiting the peak pressure delivered so that the mechanical index (MI) was under 4.7. Degassed gel was used to couple the transducer system to the skin of the subjects. In total, 3860 data sets were divided into training and test sets.

B. Data pre-processing

Since RF is variable from one system to another, RF frames were pre-processed by scaling the minimum and maximum pixel value between −1 and 1. It may be advantageous in the future for a network to learn characteristics of RF data directly output by the ultrasound system, without normalization, for faster and real-time operation. After normalization, the RF data was separated into corrupted data with FUS interference and clean data without interference. Since it is not possible to acquire corrupted and clean frames of the exact same physical position of real scatterers, frames taken just before and after the FUS pulse were used as target frames (ground truth) to compare with frames with FUS interference with the assumption that high frame rates minimize movement from one acquisition to the next. Of course, simulated data or artificially corrupting data could be used to achieve the same scatterer position between the two data sets. However, we wanted the network to learn the real physical representation of interference and thus, real data was essential and could not be substituted for simulated data. An 80–20 training-test split was utilized and corrupted/clean RF pairs were zipped into a tensorflow dataset (TFdata) structure. Examples of input data for all data types can be seen in Figs. 2, 3, 7, and 8.

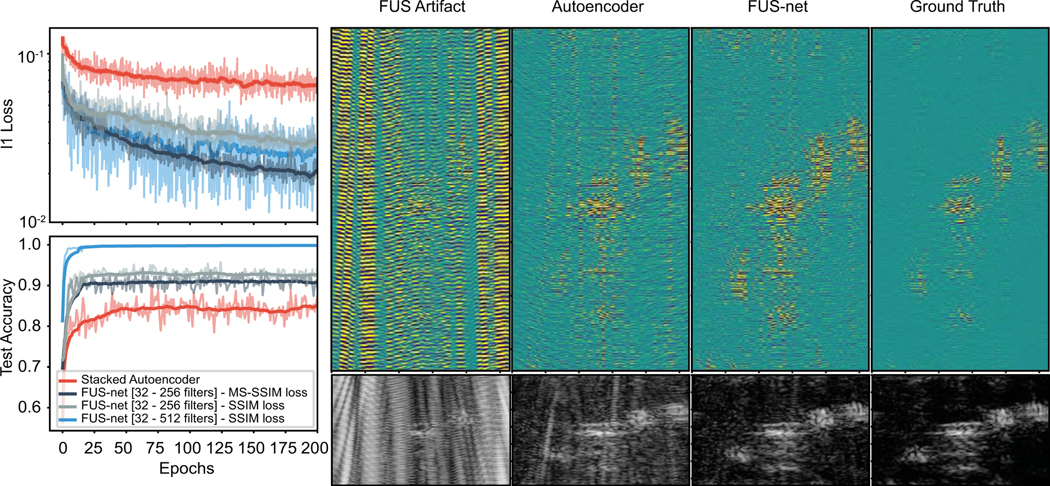

Fig. 3.

U-net performance vs SAE. Training loss and test accuracy for 200 epochs are shown on the left. Representative RF stacks are shown on the right for the FUS input, the SAE output, the U-net output, and the ground truth, respectively. Beamformed images of a human median nerve cross-section are shown below their indicated RF data stack.

Fig. 7.

Beamformed images of FUS-net, notch filtered, and adaptive LMS filtered murine (rows 1 & 2) and human muscle tissue (rows 3 & 4) under various pressure levels. (Rows 1 & 2) mouse hind limb at 1.3 MPa and 6.2 MPa, respectively. (Rows 3 & 4) human median nerve cross section at 10.2 MPa and. 18.7 MPa, respectively.

Fig. 8.

Sample filtered outputs from unseen FUS-corrupted RF data in tissue mimicking phantoms. FUS artifacts and corresponding ground truths are shown in the first two columns. Resultant images are beamformed from FUS-net, notch filters, and adaptive LMS outputs over pressure (rows). The last row shows representative zoomed regions of corresponding filter method outputs.

C. Loss

Appropriate loss functions are essential for a working network application, as evidenced by innovative deep learning networks, such as in GANs, created through clever loss paradigms. In the present study, two loss schemes were explored, loss alone and loss with image similarity (SSIM). We used the loss as defined in eq (1) [17]:

| (1) |

where p is a pixel in image P and N is the number of images in the dataset. x and y denote the generated RF data and ground truth ‘clean’ RF data, respectively.

We used the following SSIM:

| (2) |

Where μ and σ denote mean and variance or covariance, and C variables are constants for ensuring stability and avoiding when the denominator becomes 0. The left and right dot products are used to define variables in the (multiscale structural simularity) MS-SSIM equation:

| (3) |

M is the scale of the image set for structural similarity computation. Here α and β are set to 1. Image similarity can be used to measure loss on the visual perception of images rather than the pixel values. However, both loss functions have trade-offs compared to each other. Thus we adopted a loss function comprised of weighted values of each [17]:

| (4) |

where is the SSIM or the multi-scale MS-SSIM. α was an arbitrary weight set to a constant 0.8. SSIM was not implemented in the stacked autoencoder, therefore comparisons between the FUS-net and the SAE were performed using just the loss.

D. Training

Both the FUS-net and the SAE were trained by inputting corrupted RF data and conditioning the network to produce clean RF. In both cases, the batch size was set to 10 with a shuffle buffer size of 1000 (randomize batches of 1000 examples at a time). A random seed number (42) was set so that all weights, for each realization of training, was the same. For the SAE, the number of filters and the number of convolution and max pooling pairs were varied. For FUS-net, the number of filters and upsampling/downsampling pairs were varied. Both networks used an adam optimizer with a learning rate of 2e−4 and a β1 of 0.9.

The proposed network was implemented in Python 3 using Tensorflow 2.3 on an Nvidia K40 GPU (Nvidia, Santa Clara, CA) with 12 gb of RAM with a i7 processor (Intel, Santa Clara, CA). The training time for 200 epochs was 4 days, 8 hours, 19 minutes, 20 seconds. The SAE network took 6 hours, 29 minutes, and 30 seconds.

E. Notch and adaptive LMS filtering

Notch filters (second order butterworth) were set at the FUS peaks within the imaging transducer bandwidth (Fig. 2). Filter cutoff frequency was set at the full-width half-max (FWHM) value of the FUS peaks in the frequency spectrum. Adaptive LMS filtering in the same manner as [9] was implemented on RF data collected for each element channel. An interference signal comprised of a sinusoid with frequencies at the center (4 MHz) and harmonics (8, 12, 16, 20) within the bandwidth was calculated a priori. Then the signal was matched to the interference for each element and the resultant filtered signal was used for futher processing.

F. Contrast-to-noise evaluation

We adapted the definition from [18] to calculate the contrast-to-noise (CNR) of the median nerve:

| (5) |

Where Si is the signal mean in an ROI centered on the median nerve (ROI1), So is the signal mean in the ROI on outside of the nerve (ROI2), σi is the signal standard deviation in ROI1, and σo is the signal standard deviation in ROI2. We calculated the CNR for the ground truth image to baseline CNR measurements after filtering with FUS-net, notch filtering, and adaptive LMS filtering. Thus, we characterize filtering ability as ΔCNR in this study.

G. Displacement estimation

Displacement was induced by the applied radiation force within the focal volume of the FUS transducer [5]. The focal volume (0.2 × 1.0 mm) was positioned so that the maximum displacement occurs at the center of the imaging transducer focal volume. To calculate displacements, RF data stacks after FUS-net or comb notch-filtering, were first beamformed using conventional delay-and-sum (DAS) beamforming [5]. The RF signals were upsampled in the axial direction by a factor of 8 and fed into a 1D normalized cross correlation algorithm [19] with a window size of 120 pixels, an overlap of 95%, and a max search length of 10 pixels. The colormap indicates axial direction of tissue movement away (blue) and towards (red) the imaging transducer. Maps were overlaid onto the original B-mode for visualization on the underlying anatomy [5].

IV. RESULTS

A. FUS-net outperforms stacked autoencoders

loss during training and accuracy on the test data set were recorded for four network architectures (1 SAE and 3 variants of the FUS-net with different filter sets) (Fig. 3). Since filter numbers always increase or decrease by factors of two, the range noted in the figure indicates the number of layers and filter numbers for sequential layers in the FUS-net training (e.g. [32 – 512] is equivalent to 5 layers with filters 32, 64, 128, 256, and 512). Average loss and test accuracy values can be seen in table III. For both metrics and all loss function/filter combinations, FUS-net performed better than the stacked autoencoder in learning the underlying artifact distribution. The average accuracy for the SAE saturated at 84%, whereas FUS-net had at least 7% higher scores. Though the FUS-Net with 32–512 filters and SSIM loss did not reach as low of training loss as the MS-SSIM variant, it achieved the highest testing accuracy (99%). Interestingly, calculating the loss based on the multiscale SSIM had the lowest error but only reached an average 91% in testing accuracy. This may be due to the input data dimensions not being large enough, thus evaluating the MS-SSIM at inappropriate filter sizes for this type of dataset. Note, training for longer than 200 show little improvements in prediction accuracy and loss at the expense of increased computational time. Therefore, we chose to proceed with the network with upsampling and downsampling stacks from 32 to 512 filters and evaluated loss on SSIM to characterize FUS filtering. Example RF outputs from the SAE and the FUS-net are displayed in Fig. 3 on the right, between the input (FUS at 18.7 MPa) and the ground truth. Respective DAS-beamformed images are shown below the RF stacks.

TABLE III.

AVERAGE LOSS AND TESTING ACCURACY FOR DEEP LEARNING NETWORKS

| Network | Loss | Test Accuracy |

|---|---|---|

| Stacked Autoencoder | 0.067±0.007 | 0.8422±0.0217 |

| FUS-net (MS-SSIM; 32–256) | 0.021±0.002 | 0.9102±0.0124 |

| FUS-net (SSIM; 32–256) | 0.031±0.004 | 0.9261±0.0093 |

| FUS-net (SSIM; 32–512) | 0.027±0.007 | 0.9983±0.0003 |

B. FUS-net outperforms notch and adaptive filtering

Though the overall accuracy on the test set was around 99%, we explored whether there was a dependency of accuracy on the FUS pressure used. The MSE for FUS-net reconstructed, notch filtered, and adaptive LMS filtered RF, not in the training set, for pressures 1.3 to 20.5 MPa evaluated in muscle tissue (n = 60 to 140 for each pressure) are shown in Fig. 4. Pixel-by-pixel MSE was calculated comparing all reconstructed images to the corresponding clean RF image. FUS-net reconstructions consistently outperform both notch filter and adaptive LMS filter algorithms at all measured pressure levels. Notch filtered outputs have higher error due to elimination of all information at the notch frequencies, blurring the output image. LMS filtered B-modes had lower error than notch filtered images yet consistently higher than FUS-net reconstructed images. The effect spans over all pressure levels tested. The error from adaptive filtering may be due to the lag time for adaptively matching the noise signal to the RF data from each individual element, resulting in high error at the beginning of the RF trace and low error near the end [9]. Lastly, the computational time to reconstruct 100 images was compared across all three algorithms (Fig. 5). Notch filtering was the fastest, followed by FUS-net which was 40 times faster than adaptive filtering. This does not take into account the time for a priori calculation of the adaptive filtering matched signal.

Fig. 4.

Mean squared error between ground truth RF data vs. FUS-net (SSIM; 32–512), notch filter, and adaptive LMS outputs as a function of FUS pressure. 60 – 120 examples from each pressure in human muscle tissue from the test set were used to calculate MSE.

Fig. 5.

Computational time for FUS-net, notch, and adaptive filtering for 100 images. For FUS-net, the computational time represents prediction time. For notch and adaptive filtering, computational time represents filter application time.

Next, we evaluated how CNR changes over pressure for FUS-net, comb notch filtering, and adaptive LMS filtering by calculating the signal means and standard deviations for regions-of-interests (ROIs) inside and outside the median nerve [18]. Figure 6 depicts a representative image of the CNR-calculated regions and demonstrates how all three algorithms operate at increasing pressures. At pressures below 6.2 MPa, all algorithms effectively filter out FUS interference - maintaining CNR similar to clean, ground truth images. At pressures above 6.2 MPa, notch filtered results show decreased CNR compared to FUS-net. Even higher decrease in CNR is shown for adaptive LMS filtering, non-linearly decreasing as a function of pressure. FUS-net reconstructed images maintain high quality CNR regardless of the FUS pressure. These results can be seen qualitatively in Fig. 7. At pressures higher than 6.2 MPa, FUS artifacts affect the reconstructed images in both notch filtering and adaptive filtering. At higher pressures, large amplitude artifacts are shown throughout notch filtered images and near the top in adaptive LMS filtered images. Both of these sources of degradation explain the poor CNR performance over pressure. Additionally, notch filtering the ultrasound bandwidth effectively removes important speckle information, i.e., the speckle quality of the beamformed image is blurred. Even though notch filtering of FUS artifacts has lower MSE than the other two algorithms (Fig. 4), it maintains higher CNR compared to adaptive filtering. The elimination of specific frequencies and thus loss of information may explain this phenomenon. This is certainly not the case for FUS-net reconstructed images - the outputs maintain similar speckle quality to clean, ground truth images and as a result, maintain low MSE (Fig. 4).

Fig. 6.

CNR for FUS-net and notch-filtered B-mode images as a function of focal pressure. The image shown is of the human median nerve.

C. FUS-net can filter FUS interference in unseen phantom RF data

To demonstrate FUS-net performance in data the network has not previously seen, we collected RF data from new scans in tissue-mimicking phantoms, since the network has only been trained on in vivo data. Figure 8 illustrates the performance of FUS-net in filtering FUS interference compared to notch filtering and adaptive LMS. Across all pressure levels, FUS-net performs qualitatively better than the other two algorithms. Additionally, for notch and adaptive filtering, the speckle shape becomes more distorted and the speckle intensity diminishes in high pressure FUS conditions. In FUS-net recovered images, the speckle shows superior reconstruction. We compared the reconstructed output to the clean ground truth using both SSIM and MSE metrics. FUS-net was found to have higher SSIM and lower MSE than the other two filtering methods (Fig. 9). Adaptive filtering performed similarly in SSIM but had higher MSE, especially for higher FUS pressures. Notch filtering performed consistently worse than both algorithms.

Fig. 9.

SSIM and MSE evaluation for FUS-net, notch, and adaptive LMS filtering of unseen FUS-corrupted data in phantoms. (Top) Calculated SSIM between filter output and ground truth for pressures 6.26 – 18.74 MPa (n=30). (Bottom) Calculated MSE for filter output and ground truth for pressures 6.26 – 18.74 MPa (n = 30).

D. FUS-net filtered RF can be used for displacement tracking

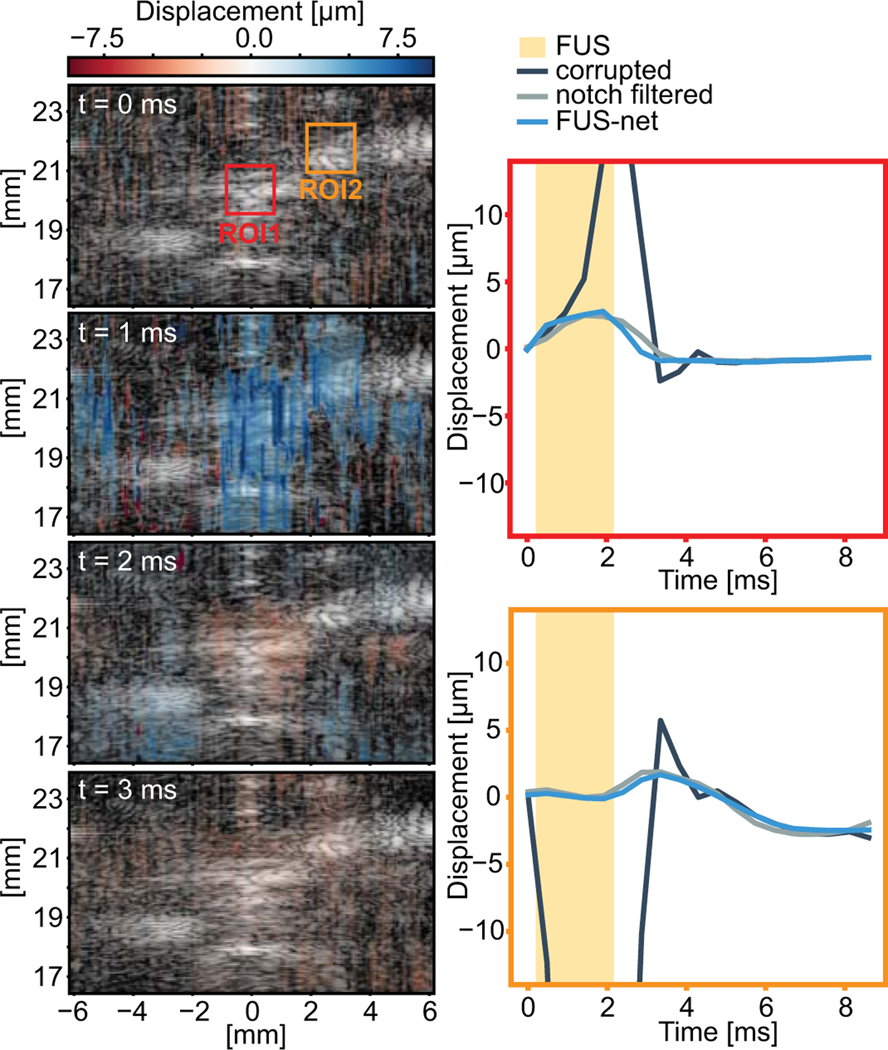

After establishing that it is possible to filter out the FUS interference using U-Nets and retain important B-mode image information, it remained to be seen whether it was possible to use these filtered RF stacks to measure displacement using conventional cross-correlation techniques. Fig. 10 shows a representative example of displacement measured from a 2 ms acoustic radiation force impulse at 10.2 MPa after FUS-net filtering2. The impulse is being delivered during the second frame. The average tracked displacement in the ROI1 (center) and ROI2 (4 mm away) boxes in the first frame are shown in the figures on the right for the original signal, the FUS-net filtered displacement, and conventional notch filtering. The ROIs here, in contrast to Fig. 6, were chosen so that displacement could be tracked in high echoic regions (the nerve and surrounding connective tissues). Without any filtering, FUS corrupts displacement measurements during the sonication. However, we observe that FUS-net or notch filters are capable of filtering and recovering displacement from the acoustic radiation focal pulse at the center of the beam and at 4 mm away.

Fig. 10.

Frame captures of FUS-net filtered displacement maps over time of a single acoustic radiation force pulse on the human median nerve. Positive displacement (away from the transducer) is in blue and negative (towards the transducer) is in red. Average displacement traces from the red and blue boxes in the first frame are on the right. Measured displacement for the same RF stack after FUS-net, notch, and no filtering are shown. The 2 ms FUS pulse was sonicated at t=0.

V. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

In this study, we explored the utility of U-Nets for filtering out FUS interference from ultrasound RF frames. FUS-net filtered RF frames reconstructed less noisy data than SAEs and had 15% higher test accuracy. Thus, FUS-net using filters between 32 and 512 was evaluated against current interference filtering algorithms. For all pressures studied, FUS-net performed better than notch filtering and adaptive LMS filtering in MSE, CNR, and speckle shape and quality. Additionally, it is four times faster than adaptive methods, albeit slower than comb notch filtering. However, light architectures being developed, such as tinyML [20], may facilitate real-time implementation of trained deep-learning networks. The concept of generalizability was explored by applying FUS-net to unseen tissue-mimicking phantom scans, demonstrating an improvement over other filtering techniques. This observation illustrates that FUS-net does indeed contain the representation of FUS interference in the latent space. Lastly, FUS-net applied to individual RF data was able to filter interference and track displacement in subsequent images.

A large consideration when choosing imaging and therapeutic FUS frequencies is the potential overlap between the high intensity FUS peaks (fundamental and subsequent harmonics) and the full-width half max sensitivity of the imaging transducer. Minimizing the overlap allows for more effective filtering. Though here we use a 18 MHz imaging transducer to image a 4 MHz FUS pulse, the use of a deep-learning-based approach for interference filtering potentially allows for any combination of imaging and FUS transducer, regardless of overlap. For our implementation of the adaptive LMS algorithm [9], both frequencies need to be known a priori and the matched therapeutic signal needs to be calculated beforehand, limiting the flexibility of the technique. However, since FUS-net is trained by propagating the FUS artifact through a bottleneck and loss is generated on the absence of the artifact, the true distribution of the FUS artifact can be learned within the latent space, given adequate numbers of training examples.

The proposed framework was then compared to comb notch filtering and adaptive LMS filtering at the fundamental frequency and harmonics of the FUS transducer frequency. At low pressures, both algorithms perform similarly. However, at higher intensities (greater than 6.2 MPa), errors between the reconstructed image and the ground truth increases. In all examples, FUS-net performs better than other filtering methods especially in areas with larger amplitude echoes from tissues like the nerve or skin. Areas low in echogenicity are more prone to errors. Moreover, since notch-filtering the RF data directly removes signal outside the notch frequency, image quality after beamforming is reduced and blurred. Images that are filtered using FUS-net retain similar speckle quality to the ground truth.

Lastly, the feasibility of estimating displacement using FUS-net filtered RF frames was explored. Displacement estimation using conventional cross correlation on RF stacks in the test set show that FUS-net stacks perform similarly to notch-filtered stacks. In addition to accurate displacement estimation, as was mentioned before, speckle quality of FUS-net images was higher than notch filtering - allowing for more accurate representation of tissue movement. Moreover, displacement dynamics, such as shear waves, are maintained after FUS-net filtering. Thus, it remains possible to adapt the network results to other ultrasonic applications, not limited to FUS surgical techniques, but also other elastography methods, such as shear wave imaging.

A. Limitations

Although the network results show higher quality B-mode images, there are trade-offs, such as in the ability to generalize to unseen examples. Though this study demonstrated filtering capabilities in never-before-seen phantom data, the accuracy on future examples will always be called into question. FUS-net may be capable of learning the underlying distribution of the FUS artifacts but they can only filter out distributions found in the training set which may not envelope all forms of FUS artifacts. It may not currently be possible to acquire the complete representation of the artifact for all frequencies and transducer combinations, but by increasing the variety of examples, we may be able to increase generalization. Using various arrangements other than the 18 MHz imaging and 4 MHz FUS configuration used in this study will add additional benefits. Alternatively, since these convolutional layers are acting only on image pixel data of the RF frames, it may help to incorporate a network that acts on time domain data to supplement reconstruction accuracy, similar to visual question answering networks [21]. There are also limitations in displacement imaging due to the operation on individual RF data. To effectively apply FUS-net output RF to displacement algorithms, it may be beneficial to modify the network to train on sequential RF data frames rather than single RF data so that coherent data is propagated through the training network, though this may increase network complexity. Lastly, conservative ultrasound parameters were used in human subjects to limit exposure to FUS; FUS-net may not currently operate at FUS intensities at surgical ablation or cavitation levels.

The training data used in this study spans several months of development of this FUS-imaging combination. Thus, we believe, under the assumption of imaging a 4 MHz FUS pulse with an 18 MHz imaging array, that the training set covers the ”true distribution” of the artifact for this system. This is bolstered by the use of real data rather than augmented data or adversarial examples that may not necessarily help the network learn the artifact distribution but rather an artificial implementation of interference. The details of an actual acquisition may not be maintained through synthetically-produced artifacts. Despite observations of FUS-net effectively filtering FUS artifacts on unseen data, further investigation must be conducted to assess whether this network can generalize without the assumption of our choices of frequencies since interference patterns may change. Thus, it may be useful to turn our attention towards more attention-based and/or graph-based networks.

B. Ethics

Careful thought should be paid to the use of deep learning, especially in medical applications where false negatives and false positives may radically change the outcome. Since U-nets have been shown to be great tools for image reconstruction and denoising, we based FUS-net on a U-net architecture as a preliminary investigation into ultrasound harmonic filtering. Future studies should compare the utility of recurrence or attention against the network presented here. Our choice of U-Net-based autoencoders over GAN-based reconstruction was made to force the network to reconstruct rather than generated data. Moreover, for generalization purposes, meta-learning methods [22] can be leveraged. Further confidence is instilled from the results presented in Fig. 7, 8, and 9; FUS-net was able to reconstruct on data and tissue types it had never seen before. Moreover, displacement traces were consistent with conventional displacement estimation by other non-deep learning methodologies. Therefore, with careful enough training, FUS-net can be applied to all FUS-based imaging methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute Of Biomedical Imaging And Bioengineering of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01EB027576. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Characterization, species type, and pressures for all files in the dataset can be found in the supporting documents/multimedia tab.

a Supplementary video is available in the supporting documets/multimedia tab.

Contributor Information

Stephen A. Lee, Columbia University, New York, NY 10032 USA.

Elisa E. Konofagou, Columbia University, New York, NY 10032 USA.

REFERENCES

- [1].Aslani P, Drost L, Huang Y, Lucht B, Wong E, Czarnota G, Yee C, Wan A, Ganesh V, Gunaseelan S, David E, Chow E, and Hynynen K, “Thermal therapy with a fully electronically steerable HIFU phased array using ultrasound guidance and local harmonic motion monitoring,” IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering, pp. 1–1, oct 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Han Y, Payen T, Wang S, and Konofagou E, “Focused ultrasound steering for harmonic motion imaging,” IEEE Transactions on Ultrasonics, Ferroelectrics, and Frequency Control, vol. 65, no. 2, pp. 292–294, feb 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Gennisson JL, Deffieux T, Fink M, and Tanter M, “Ultrasound elastography: Principles and techniques,” pp. 487–495, may 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Payen T, Oberstein PE, Saharkhiz N, Palermo CF, Sastra SA,Han Y, Nabavizadeh A, Sagalovskiy IR, Orelli B, Rosario V, Desrouilleres D, Remotti H, Kluger MD, Schrope BA, Chabot JA, Iuga AC, Konofagou EE, and Olive KP, “Harmonic motion imaging of pancreatic tumor stiffness indicates disease state and treatment response,” Clinical Cancer Research, vol. 26, no. 6, pp. 1297–1308, mar 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Lee SA, Kamimura HAS, Burgess MT, and Konofagou EE, “Displacement imaging for focused ultrasound peripheral nerve neuro-modulation,” IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging, vol. 39, no. 11, pp. 3391–3402, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Kovatcheva RD, Vlahov JD, Stoinov JI, and Zaletel K, “Benign Solid Thyroid Nodules: US-guided High-Intensity Focused Ultrasound Ablation—Initial Clinical Outcomes,” Radiology, vol. 276, no. 2, pp. 597–605, aug 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Wu CC, Chen CN, Ho MC, Chen WS, and Lee PH, “Using the Acoustic Interference Pattern to Locate the Focus of a High-Intensity Focused Ultrasound (HIFU) Transducer,” Ultrasound in Medicine and Biology, vol. 34, no. 1, pp. 137–146, jan 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Jeong JS, Chang JH, and Shung KK, “Pulse compression technique for simultaneous HIFU surgery and ultrasonic imaging: A preliminary study,” Ultrasonics, vol. 52, no. 6, pp. 730–739, sep 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Jeong JS, Cannata JM, and Shung KK, “Adaptive HIFU noise cancellation for simultaneous therapy and imaging using an integrated HIFU/imaging transducer,” Physics in Medicine and Biology, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Song JH, Yoo Y, Song TK, and Chang JH, “Real-time monitoring of HIFU treatment using pulse inversion,” Physics in Medicine and Biology, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Bengio Y, Courville A, and Vincent P, “Representation learning: A review and new perspectives,” 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Oktay O, Ferrante E, Kamnitsas K, Heinrich M, Bai W, Caballero J,Cook SA, De Marvao A, Dawes T, O’Regan DP, Kainz B, Glocker B, and Rueckert D, “Anatomically Constrained Neural Networks (ACNNs): Application to Cardiac Image Enhancement and Segmentation,” IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging, vol. 37, no. 2, pp. 384–395, feb 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Işil C, Yorulmaz M, Solmaz B, Turhan AB, Yurdakul C, Unl¨ u S,¨ Ozbay E, and Koç A, “Resolution enhancement of wide-field interferometric microscopy by coupled deep autoencoders,” Applied Optics, vol. 57, no. 10, p. 2545, apr 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].An J and Cho S, “Variational Autoencoder based Anomaly Detection using Reconstruction Probability,” Tech. Rep, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- [15].Vincent P, Larochelle H, Lajoie I, Bengio Y, and Manzagol PA, “Stacked denoising autoencoders: Learning Useful Representations in a Deep Network with a Local Denoising Criterion,” Journal of Machine Learning Research, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- [16].Hashisho Y, Albadawi M, Krause T, and Von Lukas UF, “Underwater color restoration using u-net denoising autoencoder,” in International Symposium on Image and Signal Processing and Analysis, ISPA, vol. 2019-Septe. IEEE Computer Society, sep 2019, pp. 117–122. [Google Scholar]

- [17].Zhao H, Gallo O, Frosio I, and Kautz J, “Loss Functions for Image Restoration With Neural Networks,” IEEE Transactions on Computational Imaging, vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 47–57, dec 2016. [Google Scholar]

- [18].Dahl JJ, Hyun D, Lediju M, and Trahey GE, “Lesion detectability in diagnostic ultrasound with short-lag spatial coherence imaging,” Ultrasonic Imaging, vol. 33, no. 2, pp. 119–133, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Luo J and Konofagou E, “A fast normalized cross-correlation calculation method for motion e ... - PubMed - N ... A fast normalized crosscorrelation calculation method for motion estimation . PubMed Commons,” IEEE transactions on ultrasonics, ferroelectrics, and frequency control, vol. 57, no. 6, pp. 1347–57, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Banbury CR, Reddi VJ, Lam M, Fu W, Fazel A, Holleman J,Huang X, Hurtado R, Kanter D, Lokhmotov A, Patterson D, Pau D, sun Seo J, Sieracki J, Thakker U, Verhelst M, and Yadav P, “Benchmarking tinyml systems: Challenges and direction,” 2021. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Antol S, Agrawal A, Lu J, Mitchell M, Batra D, Zitnick CL, and Parikh D, “VQA: Visual question answering,” Tech. Rep, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- [22].Zhou F, Wu B, and Li Z, “Deep meta-learning: Learning to learn in the concept space,” 2018. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.