Abstract

Background

Interest in and use of co-production in healthcare services and research is growing. Previous reviews have summarized co-production approaches in use, collated outcomes and effects of co-production, and focused on replicability and reporting, but none have critically reflected on how co-production in applied health research might be evolving and the implications of this for future research. We conducted this scoping review to systematically map recent literature on co-production in applied health research in the United Kingdom to inform co-production practice and guide future methodological research.

Methods

This scoping review was performed using established methods. We created an evidence map to show the extent and nature of the literature on co-production and applied health research, based on which we described the characteristics of the articles and scope of the literature and summarized conceptualizations of co-production and how it was implemented. We extracted implications for co-production practice or future research and conducted a content analysis of this information to identify lessons for the practice of co-production and themes for future methodological research.

Results

Nineteen articles reporting co-produced complex interventions and 64 reporting co-production in applied health research met the inclusion criteria. Lessons for the practice of co-production and requirements for co-production to become more embedded in organizational structures included (1) the capacity to implement co-produced interventions, (2) the skill set needed for co-production, (3) multiple levels of engagement and negotiation, and (4) funding and institutional arrangements for meaningful co-production. Themes for future research on co-production included (1) who to involve in co-production and how, (2) evaluating outcomes of co-production, (3) the language and practice of co-production, (4) documenting costs and challenges, and (5) vital components or best practice for co-production.

Conclusion

Researchers are operationalizing co-production in various ways, often without the necessary financial and organizational support required and the right conditions for success. We argue for accepting the diversity in approaches to co-production, call on researchers to be clearer in their reporting of these approaches, and make suggestions for what researchers should record. To support co-production of research, changes to entrenched academic and scientific practices are needed.

Protocol registration details: The protocol for the scoping review was registered with protocols.io on 19 October 2021: https://dx.doi.org/10.17504/protocols.io.by7epzje.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12961-022-00838-x.

Keywords: Co-production, Co-creation, Applied health research, Scoping review

Background

Despite the lack of clarity around the definition, what it means in practice and what it comprises, enthusiasm for co-production in healthcare services and research is growing. The lack of clarity is evident in the plethora of terms in use. For example, within healthcare we witness services, programmes and interventions being “co-created”, “co-designed”, “co-evaluated” or “co-implemented”. This can involve stakeholder and public engagement through participation or involvement in any or all steps of the applied research cycle [1, 2]. All are regarded as processes of co-production, but the way they are enacted and operationalized varies depending on the purpose, what is being co-produced and by whom [3, 4]. Some of the ambiguity in co-production also comes from its unclear relationship with patient and public involvement/and engagement (PPI/E). For some, co-production represents enhanced PPI/E, a way to improve on its shortcomings by re-engaging with the principles of power-sharing, equality and social justice, and reinforcing the democratic right of citizens to influence healthcare [3, 5]. For others, co-production simply represents another way of consulting the public and service users to provide instrumental inputs into health and social care services and research, demonstrating a more technocratic rationale [6]. New experimental perspectives on co-production, which frame it as a generative process and a social space within which new interactions, insights and knowledge are produced, challenge conventional notions of engagement and involvement [4]. However, whilst new conceptualizations and discussion can help the approach and foundational principles to further develop and evolve, and more and different forms of co-production to emerge, this also adds to the uncertainty around its use.

The United Kingdom National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) recently embraced co-production as a means of improving public involvement in research, framing it as a more collaborative and egalitarian mode of involvement with values and principles for greater equality [7]. Unlike other funders of health research globally, NIHR insists on community involvement in research proposals, and it is a key criterion for funding [8]. Other funders have started to encourage co-production by providing flexible funding to cover costs of user-led research design and engagement [9] and funding research into best practice for community engagement [10]. In the United Kingdom context, some argue that the architecture of the new NIHR Applied Research Collaboration funding model enables authentic and visible co-production [11]. Others are more cautious, arguing that co-production can only be as successful as the system allows, and that traditional research structures often fail to facilitate effective public involvement, leading to co-opting of the term co-production without making a tangible difference [12, 13]. However, there are anecdotal stories of successful collaborative working from the previous NIHR funding model, Collaborations for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care (CLAHRC), where co-production projects added value and led to the implementation of novel services and interventions [14]. Success stories like these are not always published or reported on or described in a way that explicates how best to support researchers to co-produce applied health research or complex health interventions.

Recent systematic reviews of co-production have summarized the different co-production approaches in use and collated outcomes and effects of co-production, and some have focused specifically on replicability and reporting. Slattery et al. conducted a rapid overview of reviews, specifically of research co-design (defined as involvement of research users at the study planning phase only) and its effectiveness, and found that co-design is widely used but rarely reported or evaluated in detail [15]. Another review examining the use of experience-based co-design (EBCD) in health service improvement also found inconsistent reporting and variation in the use of the approach, leading the authors to argue for reporting guidelines to encourage consistency and to improve the potential of the approach [13]. Halvorsrud pooled effects data from co-creation projects in international health research and found moderate to small effects on a range of outcomes from different study designs and interventions, yet little evidence of longer-term effects of co-creation [16]. Acknowledging the lack of evidence of the impact of co-produced or co-created interventions in healthcare settings, some authors have reviewed the evidence on outcomes and factors influencing the quality and level of co-production and co-creation [17, 18]. These reviews found that studies of processes and factors influencing co-production dominated, and identified fewer studies evaluating clinical, service or cost outcomes.

While various aspects of co-production have been subject to more or less rigorous systematic reviews in the last 5 years, no reviews have targeted co-produced applied health research or the co-production of complex interventions (which is often the focus of applied research). Nor have previous reviews critically reflected on how co-production is conceptualized in applied health research, or how the principles are enacted, to draw out implications for the practice of co-production and for future research. Applied health research is becoming more collaborative, with patient and public groups increasingly engaged in research projects alongside academics and practitioners, and funders are gradually mandating the use of co-production principles. It is therefore timely to reflect on what has been learned about the practice of co-production in applied health research and help forecast the direction of future research.

We conducted a scoping review to systematically map recent literature on co-production in applied health research in the United Kingdom to inform co-production practice and guide future methodological research. The review was designed to answer the following questions:

What is the type and scope of literature on co-production in applied health research?

How is co-production conceptualized and understood?

How is co-production implemented in applied health research?

What lessons are there for co-production practice and future research, based on the current knowledge base?

Methods

We used established scoping review methods to systematically map the nature of the evidence, summarize practice, and identify gaps in the literature on co-production in applied health research [19, 20]. We had to streamline our approach to the study screening and selection process because of time and resource availability, and therefore followed accepted rapid review methods for single screening of titles and abstracts and independent verification of a sample of full-text articles [20]. We intentionally kept the review questions broad and open to generate breadth of coverage, and once we had a sense of the volume of literature, we set parameters to limit the number of studies to a manageable level. The protocol is published on protocols.io.

We define co-production as a way for academics, practitioners, and patients and the public to work together, sharing power and responsibility across the whole research cycle [7]. For the purpose of this scoping review, we have assumed that co-production happens at any or all stages of the research cycle, and so included reports using any of the plethora of terms in use including co-design, co-production, co-implementation, co-evaluation and co-creation.

Search strategy

We followed a standard approach to locate published literature in scoping reviews [21]. First, we listed key terms and synonyms relevant to each of the inclusion criteria (Table 1) and performed an initial high-level search of one relevant multidisciplinary database (ProQuest) using main keywords in the title. We analysed the text words used in the retrieved article titles and abstracts, then conducted a comprehensive search of five other relevant databases (CINAHL, Google Scholar, MEDLINE, Scopus, Web of Science) using all identified keywords and index terms. We conducted a separate search to ensure we identified co-production of complex health interventions as well as the broader applied health research literature. The third step involved searching all reference lists of retrieved articles to identify additional literature. An example search strategy can be found in Additional file 1. We downloaded all retrieved articles and managed the screening process in Mendeley.

Table 1.

Scoping review inclusion criteria

| Inclusion criteria | Definition | Synonyms and search terms |

|---|---|---|

| Participants | Any stakeholders involved in applied health research (e.g. researchers, patients, public) | Health research, applied health researcha, health, healthcare, health care, complex health intervention researchb |

| Intervention | Co-production approach or methodology | Co-production, co-produc*, co-design, co-creation, co-creat*, co-evaluation, co-evaluat* |

| Context | United Kingdom literature: research conducted in or relevant to United Kingdom context (e.g. systematic reviews that included studies conducted in the United Kingdom) | Limit = United Kingdom |

| Outcomes |

Definitions, typologies or conceptualization of co-production Key outcomes (conceptual, methodological, impact, health, experiential) Research implications |

|

| Type of literature | Any type of published literature including systematic reviews, literature reviews, empirical research (evaluations of co-production or co-produced intervention research), guidelines, opinion or comment pieces | |

| Language | English language only | Limit = English language |

| Date limits | From 2010 onwards, when “co-production” started to appear in the health literature |

Limit to year = “2010–2020” Subsequently limited to 2018–2020 given the large number of hits from initial searches |

aApplied health research aims to address the immediate issues facing the health and social care system, bringing research evidence into practice and influencing policy

bInterventions with multiple behavioural, technological and organizational interacting components and nonlinear causal pathways and components that act independently or interdependently

Study selection

We included any type of published literature (empirical research, reviews, guidelines, opinion pieces or commentaries) relevant to co-production in applied health research or complex intervention development that reported on a range of outcomes including conceptual, methodological, impact or health. We were interested in literature that included definitions or conceptualizations of co-production, as well as implications for future research. We intentionally included only papers reporting applied health research conducted in the United Kingdom—to keep the focus on learning within a specific context. Following the initial searches and familiarity with the extent of the literature, we refined our inclusion criteria. Our initial database searches included papers published from 2010 onwards, when “co-production” began to appear in the health literature and as a requirement of some funding schemes in the United Kingdom; we subsequently limited the date range to 2018–2020 due to the large number of hits and to keep the charting and summarizing steps manageable.

Based on established rapid review methods [20], one author (HS) applied the inclusion criteria to all titles and abstracts retrieved in the search. After excluding articles that did not meet the criteria, we retrieved full text copies of all remaining articles. One author screened these for inclusion (HS), and another author (LB) independently screened 25% of articles; discrepancies in include or exclude decisions were resolved by discussion.

Data extraction

We used a Microsoft Excel worksheet to chart the characteristics and record key information from the articles included in the review (e.g. author, year of publication, study design, health speciality, aim, intervention type, outcomes reported, implications for practice and research). The items and information to be collected from each article were piloted by two team members, and adjustments made to ensure it was fit for purpose and standard information could be extracted in the same way for each article. Charting was completed by three authors (CG, IH, AH) and an independent check of 25% of the articles was done by another author (HS).

Summarizing and reporting the findings

We used a descriptive-analytical method using the charted information as an overall framework for reporting across all included articles [19]. The resulting chart or evidence map shows the extent and nature of the literature on co-production and applied health research. Based on this map we developed a narrative summary, first describing the characteristics of the articles and scope of the literature (type, study design, health speciality, key outcomes reported), followed by a summary of conceptualizations of co-production and how co-production was implemented, as described in the articles. We extracted from the discussion section of each study any mention of implications for co-production practice or future research and conducted a content analysis of this information to identify lessons for the practice of co-production and themes for future methodological research. Reporting of the findings follows the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) format [22].

Findings

Description of included studies

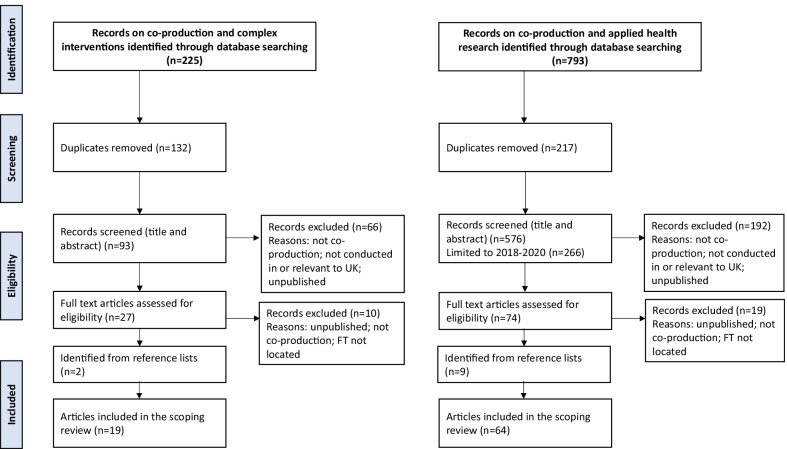

Database searching identified 793 records on co-production and applied health research and 225 on co-produced complex interventions (after limiting the search to 2018–2020). After removal of duplicates, there were 576 records on co-production and applied health research and 93 on complex interventions, of which we reviewed the full texts of 74 and 27, respectively. We excluded articles if they did not report on co-production, were not conducted in or relevant to the United Kingdom context, or were unpublished reports (Fig. 1). After including additional relevant articles identified from reference lists, n = 19 articles reporting co-produced complex interventions and n = 64 reporting co-production in applied health research met the inclusion criteria and were included in the scoping review.

Fig. 1.

Adapted Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow diagram of the search strategy

Scope of literature on co-production in applied health research

Table 2 summarizes the key characteristics of studies included in the scoping review. Nineteen reported co-produced complex interventions (N = 19) including intervention development or evaluation studies (n = 10), systematic reviews or evidence reviews (n = 3) and critical reflections or opinions (n = 6). The intervention studies mainly used descriptive study designs, including mixed-method observational studies that described the development of co-produced interventions or qualitative research that reported the process of co-producing an intervention and/or stakeholder views on the process. The systematic reviews or rapid evidence reviews synthesized empirical evaluations, processes and outcomes of co-production, and the critical reflections or opinion pieces described author experiences of co-producing interventions, or provided interpretations and conceptualizations of co-production.

Table 2.

Characteristics of included studies

| Author (year) | Lead organization/location | Aim | Study design/stakeholder type | Intervention reported | Health specialty | Outcomes of interest | Type of co-production used/methods | Co-production features/principlesa | Reports research or methodology gaps | Reports policy/practice implications | Funder or source of funding |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (i) Co-produced complex interventions (N = 19) | |||||||||||

| Intervention development or evaluation (n = 10) | |||||||||||

| Brookes [23] |

NHS Trusts Birmingham Nottingham |

To develop a reflective learning framework and toolkit for healthcare staff to improve patient, family and staff experience |

Observational/mixed-method Clinical and managerial staff, patients and relatives from acute medical units |

Patient experience and reflective learning (PEARL) toolkit—locally adaptable workplace-based toolkit with guidance on using reflective learning to incorporate patient and staff experience in routine clinical activities | Acute and intensive care |

Impact Barriers and facilitators of reflective behaviours Observations of capability, opportunity & motivation of staff Output reflective learning toolkit |

Co-design Meetings and workshops with all participants Reflection and discussion |

Sharing of power Joint decision-making Involvement at all project stages |

* | NIHR | |

| Buckley 2019 [24] |

University NW England |

To explore the preliminary effects and acceptability of a co-produced physical activity referral intervention | Evaluation | Physical activity referral intervention designed to support participants in making gradual and sustainable changes to their physical activity levels | Public health/health promotion |

Health Physical activity, cardiometabolic and anthropometric measures Impact Perception of the intervention vs usual care |

Co-design | NR | * | PhD studentship | |

| Buckley 2018 [25] |

University NW England |

To report process data from the participatory co-development phase of an exercise referral scheme (ERS) in a large city in NW England |

Qualitative/participatory research Multilevel: commissioners, general practitioners (GPs), health trainers, exercise referral practitioners, academics |

Physical activity referral intervention designed to support participants in making gradual and sustainable changes to their physical activity levels | Public health/health promotion |

Impact Challenges of co-production Output Factors to consider when translating evidence into practice in an exercise referral setting |

Service co-production Development group meetings Small group collaborative activities |

Sharing of power Respecting & valuing all contributions Ongoing dialogue Continuous reflection |

* | * | PhD studentship |

| Clayson 2018 [26] |

Community research organization Liverpool |

To create a working aide-mémoire, using accessible language, for the process of co-production research between academia and marginalized and stigmatized groups (e.g. people with lived experience of substance use recovery) |

Qualitative/ethnographic reflection Academic and community researchers |

Checklist to guide co-production | Addiction/substance use |

Methodological Problems and factors to ensure adherence to co-production principles |

Co-production Video diaries Blogs Recorded interviews Critical reflection |

Knowledge exchange Asset-sharing Respecting & valuing all contributions Joint decision-making Continuous reflection Involvement at all project stages |

* | * | NR |

| Davies 2019 [27] |

University London |

To report the development and components of a prototype website to support family caregivers of a person with dementia towards the end of life |

Observational/mixed-method Academics, health workers, carers, charity members with expertise in dementia |

Prototype website aimed at supporting family caregivers of someone with dementia towards the end of life in the United Kingdom | Older people/dementia |

Output Targets and components of the website |

Co-production Research development group meetings User testing in individual interviews |

Involvement at all project stages Including all perspectives |

* | NIHR | |

| Evans 2019 [25] |

University Swansea |

To report the method used by a group of patient and carer service users to develop and implement a model for involving public members in research |

Observational/mixed-method Patients with chronic long-term condition and carers |

Service Users with Chronic Conditions Encouraging Sensible Solutions (SUCCESS) model for co-production that involves service users from the start | Chronic illness |

Methodological Process of co-production Output Principles for involving service users |

Co-production One workshop with group work |

Including all perspectives Establishing ground rules Involving public members in research |

* | * | NIHR |

| Farr 2018 [28] |

University Bristol |

To examine patient and staff views, experiences and acceptability of a United Kingdom primary care online consultation system |

Evaluation/mixed-method GPs, practice nurses, practice managers, administrators, patients |

eConsult online consultation system for primary care | Primary care |

Impact Patient interaction with and use of eConsult; staff satisfaction; practice efficiency Health Consultation type and outcome |

Service co-production Used as a theoretical framework for analysis of interviews |

NR | * | * | NIHR |

| Gradinger 2019 [29] |

University NHS Trust Devon |

To report on the impact of two researchers in residence (RiR) working on care model innovations in an integrated care provider organization, as perceived by stakeholders |

Case study/mixed-method RiR, academics, quality improvement lead, managers, clinicians |

Two new care models: (1) Enhanced Intermediate Care Service and (2) co-located holistic link-worker Wellbeing Coordinators Programme | Social care |

Impact Stakeholder perceptions of impact; attributes and behaviours for effective interaction |

Co-production using embedded researchers Collaborative working |

Ongoing dialogue Building and maintaining relationships |

* | * |

Torbay Medical Research Fund Torbay & an NHS Foundation Trust supported by NIHR |

| Henshall 2018 [30] |

University West Midlands |

To improve quality and content of midwives’ discussions with low-risk women on place of birth |

Observational/mixed-method Academics, midwives, women’s representatives |

Place of birth intervention package | Maternal health |

Impact Midwives’ use and impact of package; knowledge and confidence in providing information to women |

Co-design Feedback visits to midwives (led by academics) Workshops with midwives and women’s reps (separately then together) |

Including all perspectives | * | * | NIHR |

| Hubbard 2020 [31] |

University Scottish Highlands |

To quickly develop an intervention to support people with severe mental ill health, that is systematic, and based on theory and evidence |

Observational/mixed-method Academics, health practitioners, charity representatives |

“Nature Walks for Wellbeing” Recently discharged mental health patients are supported to go on nature walks to support their long-term recovery |

Mental health |

Output Nature Walks for Wellbeing, a 60-min walk in a group Booklet outlining the importance of outdoor activity Text message once/week for the first 12 weeks post-discharge to support patients |

Co-production Meetings between academics and stakeholders |

Including all perspectives Joint decision-making Respecting & valuing all contributions |

* | * | Supported by NIHR |

| Systematic or evidence reviews or overviews (n = 3) | |||||||||||

| Lim 2020 [32] |

University Global |

To describe the process and outcomes of services or products co-produced with patients in hospital settings | Rapid evidence review | NA | Health services research |

Impact Co-production strategies and types Outcomes associated with co-produced interventions Methodological limitations within the co-production process |

Co-production (various) | NA | * | * | National Health and Medical Research Council Fellowship |

| O’Cathain 2019 [33] |

University England |

To review approaches to intervention development to identify the range of approaches available in order to help researchers to develop complex interventions | Systematic methods overview | NA | Health services research |

Output Creation of a taxonomy/guide for intervention development approaches |

Partnership approaches (incl co-production, co-creation, EBCD) | NA | * | Medical Research Council | |

| Smith 2018 [34] |

University United Kingdom |

To produce an updated synthesis of the co-creation and co-production evidence base in the United Kingdom by identifying empirical evaluations of policies, programmes, interventions and services which incorporated principles of co-creation and co-production | Rapid evidence review | NA | Health services research |

Methodological Definitions, objectives and methods used to evaluate co-created and co-produced policies, programmes and interventions |

Co-production Co-creation |

NA | * | NR | |

| Critical reflections or opinion (n = 6) | |||||||||||

| Locock 2019 [35] |

University England |

To examine the boundaries and commonalities between co-design approaches to incorporating user perspectives (in the context of designing biomedical research interventions) | Opinion | NA | Biomedical research |

Conceptual Identifying overlap between methods/concepts Ethical/conceptual underpinnings |

Co-production Co-design | NA | * | * | National Science Foundation |

| Madden 2020 [36] |

University York |

To explore how PPI and co-production were interpreted and applied in the development of a complex intervention on alcohol and medicine use in community pharmacies |

Critical reflection Pharmacists, patients, carers, PPI group, professional practice group, policy advisory group |

Community pharmacy: Highlighting Alcohol use in Medication appointments (CHAMP)-1 programme | Pharmacy |

Methodological Barriers/levers to co-producing an intervention in a NIHR research programme |

Co-production Workshops with pharmacists and patients Consultation with PPI and professional practice groups |

Patient perspective Skills & personal development Ongoing dialogue Involvement at all project stages |

* | * | NIHR |

| Ramaswarmy 2020 [37] |

University United Kingdom/global |

To describe how concepts drawn from the field of implementation science can be used to improve the consistency and quality of Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) implementation | Critical reflection | NA | Surgery |

Conceptual Overview of EBCD concepts in the implementation of ERAS service development |

EBCD Patient as co-creator of design process and services |

NR | * | NRb | |

| Raynor 2020 [38] |

University Leeds Bradford |

To examine the feasibility and acceptability of health service researchers co-leading EBCD in multiple healthcare settings as part of intervention development |

Critical reflection Patients, family/carers, health processionals |

“Improving the Safety and Continuity of Medicines management at Transitions of care” (ISCOMAT) was used as a case study | Health services research |

Methodological Feasibility, acceptability and barriers to intervention development using EBCD |

EBCD Interviews Patient & staff feedback events Joint feedback event Co-design group meetings |

Including all perspectives Involvement at all project stages Respecting & valuing all contributions |

* | NIHR | |

| Rousseau 2019 [39] |

University United Kingdom |

To describe and understand the views and experiences of developers and stakeholders about how design occurs in health intervention development | Qualitative reflection | NA | Health services research |

Methodological How design occurs in complex health intervention development |

Co-design | NA | * | Medical Research Council | |

| Young 2019 [40] |

University NHS Trusts Leicester Lancashire |

To describe the process used to co-produce progression criteria for a feasibility study of a complex health intervention |

Qualitative Patients, clinicians, academics |

NA | Health services research |

Methodological Outlining method of co-producing “progression criteria” within feasibility studies |

Co-production Individual discussion groups Mixed discussion groups (idea generation, voting, ranking, discussion) |

Sharing of power Respecting & valuing all contributions Including all perspectives Training and support |

* | NIHR | |

| Author (year) | Lead organisation /location | Aim | Study design /stakeholder type | Intervention reported | Health specialty | Outcomes of interest | Type of co-production used/methods | Co-production features/principles | Reports research or methodology gaps | Reports policy/practice implications | Funder or source of funding |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (ii) Co-production in applied health research (N = 64) | |||||||||||

| Intervention development or evaluation (n = 34) | |||||||||||

| Ali 2018 [41] |

University N England |

To develop a simple health literacy intervention aimed at supporting informed reproductive choice among members of UK communities practising consanguineous marriage |

Qualitative Researchers, product designer, community leaders, religious leaders, lay members, health professionals |

Information leaflets/material to enhance health literacy | Public health—reproductive health |

Output Information leaflets; audio and video clips on a local NHS website link |

Co-design Interviews, focus groups (with vignettes), participatory workshops |

Including all perspectives Respecting & valuing all contributions Ongoing dialogue Involvement at all project stages |

* |

NHS Leeds NIHR |

|

| Beal 2019 [42] |

For-profit company United Kingdom |

To share an approach to improve the quality of care and services in a secure mental health setting by valuing the contribution of family and friends |

Quality improvement Health workers, family and friends of people with mental ill health |

Carer toolkit | Mental health |

Methodological Ways to carry out co-production with family and friends; lessons learned Output Co-produced carer toolkit |

Co-production Workshops Co-presentation of outputs |

Working “with” families and friends | * | NR | |

| Bielinska 2018 [43] |

University NHS Trust London |

To co-design an interview topic guide to explore healthcare professionals’ attitudes towards future care planning with older adults in hospital |

Qualitative Patients, carers, health professionals |

An interview topic guide | Older people |

Methodological Benefits of multi-professional, patient and carer involvement in co-design Impact Understanding of hospital-based anticipatory decision-making |

Co-design Patient and carer panel |

NR | NR | ||

| Best 2019 [44] |

University Swansea/global |

To investigate the use of innovative teaching methods and share a four-step model, to promote the use of co-production in mental health practice |

Qualitative Lecturers, undergraduate and postgraduate students in nursing and social work, mental health service users |

A four-step model to help develop co-productive teaching methods | Mental health |

Output A four-step model to help develop co-productive teaching methods which ultimately empower students and service users |

Co-production World café |

Building relationships Respecting & valuing all contributions Joint decision-making Sharing of power |

* | * | NR |

| Bolton 2020 [45] |

University London |

To evaluate a community-organized health project by comparing results from two different designs—researcher-controlled and community-controlled |

Evaluation Communities, health professionals, academics |

Community-organized health project (Parents and Communities Together) | Public health/maternal and child |

Methodological Challenges of using researcher-controlled designs to evaluate community-led interventions Differences in results of the two evaluations |

Co-production Social support meetings Health education workshops |

Reciprocity Building relationships |

* |

Guy’s & St Thomas’ charity NIHR |

|

| Chisholm 2018 [46] |

NHS Trust London |

To explore the processes that facilitated EBCD with carer involvement |

Case study Service users, carers, health professionals |

Family and carer EBCD project | Mental health |

Impact Perceptions of the project and participation in it; factors that help and hinder progress; theoretical model of key processes |

EBCD Process-mapping Videos Co-design groups using role play |

NR | * | * | No funding |

| de Andrade 2020 |

University Scotland |

To explore how asset-based approaches and co-production could be used to engage “hard-to reach” communities |

Qualitative Community members, professional stakeholders (government, voluntary & third sector) |

Asset-Based Indicator Framework | Health research |

Impact Developed and critiqued participant-led frameworks for asset-based approaches to address health inequalities; co-production with Black minority ethnic groups |

Co-production Community-based participatory action research Action-research workshops with professionals and community members & professionals Video Reflexive journals |

NR | * | * | ESRC (Economic and Social Research Council) |

| Dent 2019 [47] |

NHS Trust Kent |

To examine the value of appreciative inquiry (AI) methodology in enabling co-productive work within mental health service development | Case study | Appreciative inquiry | Mental health services |

Impact Description of the use of AI; observations on its use in mental health service improvement |

Co-production The application of AI in co-production |

NR | * | * | NR |

| Eades 2018 [48] |

Charity NHS Mental Health Trust Berkshire |

To quantitatively measure any impact that independent mental health advocacy (IMHA) support had on patients’ self-determination |

Evaluation Patient volunteers resident in hospital |

An IMHA service | Mental health |

Health Psychological well-being and self-determination; autonomy, competence and relatedness Output Co-produced questionnaire |

Co-production Focus group with patient volunteers |

NR | NR | ||

| Farr 2019 [49] |

University Bristol |

To investigate the feasibility and acceptability of the pilot implementation of a co-designed care pathway tool (CPT) in professionals’ practice to co-produce care plans and enable efficient working |

Qualitative Service users, mental health practitioners, service development staff |

CPT | Mental health |

Impact On normalization process theory constructs Output an electronic CPT |

Co-design Iterative co-design and testing |

Used co-production principles (not elaborated) Training and support |

* |

NIHR Otsuka Health Solutions |

|

| Faulkner 2021 [50] |

Independent service user University London |

To inform researchers, practitioners and policy-makers about the value of user leadership in co-productive research with practitioners, particularly for a highly sensitive and potentially distressing topic |

Observational Service users, practitioners, academics |

User-led study “Keeping Control” | Mental health |

Conceptual Highlights the importance, achievements and benefits for all people involved in co-producing research Methodological Explores the methodological aspects of a user-led study investigating service user experiential knowledge |

Co-production User-led interviews with service users Focus groups with practitioners Social media discussion Stakeholder sense-making event |

Shared aims and values Joint decision-making Agreed co-production working principles (not elaborated) |

* | NIHR | |

| Gartshore 2018 [51] |

University London |

To explore the implementation and impact of a service user-led co-design intervention to improve user and staff experience on an adult acute psychiatric inpatient ward |

Evaluation (mixed-method) Service users, clinical and managerial ward staff |

EBCD quality improvement intervention on a mental health admission ward | Mental health |

Methodological Awareness of EBCD Impact Challenges and benefits of co-design; factors contributing to implementation of EBCD |

EBCD Observations and interviews with staff Videos of service user narratives Staff and joint staff & service user feedback events |

NR | * | NR | |

| Gault 2019 [52] |

University London |

To co-produce consensus on the key issues important in educating mental healthcare professionals to optimize mental health medication adherence in Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic (BAME) groups |

Qualitative Service users, carers, student nurses |

Educational intervention for mental healthcare professionals | Mental health |

Impact Users able to challenge original intention of the study Health Perceptions of factors enabling or disabling medication adherence Output Consensus on content and delivery of an educational intervention for health professionals |

Co-production Interviews with service users & carers Consensus workshop with users & carers |

NR | * | * | Health Innovation Network South London |

| Giebel 2019 [53] |

University Liverpool |

To assess the extent of public involvement, experiences of public advisers and resulting changes in the dissemination of the North-West Coast household survey |

Qualitative Public advisors, partner in local authorities and NHS Trusts, academics |

Dissemination of a household health survey | Health research |

Methodological Extent of public involvement; lessons for improving public involvement; experiences of involvement in dissemination of survey findings Impact Improved dissemination of survey results |

Co-production Focus group discussion Co-production workshop with public advisers, partners from local authorities and NHS Trusts, academics |

Support Respecting & valuing all contributions Transparency |

* | * | NIHR Wellcome Trust |

| Girling 2019 [54] |

University Newcastle |

To explore how young people presenting to youth justice services describe and understand their mental health needs, and to explore how EBCD could be applied to facilitate service developments |

Qualitative Service providers, academics |

EBCD intervention with young people who offend | Mental health |

Methodological Challenges in EBCD; effects of including first-hand experiences; shared experiences of challenges among researchers applying EBCD |

EBCD Interviews with staff and academics |

NR | * | * | NIHR |

| Halsall 2019 [55] |

NHS Trust Lancashire |

To address the challenges of co-production through use of social media by creating a Facebook forum for discussion and consultation |

Quality improvement Service users, health professionals |

Closed Facebook forum for members with either lived or professional experience of perinatal mental health issues | Mental health |

Methodological Perceptions of participation in the forum & how it shaped service developments |

Co-design Facebook forum to discuss service developments |

NR | NR | ||

| Horgan 2018 [56] |

University Ireland/global |

To develop an understanding of the potential contribution to mental health nursing education by those with experience of mental health service use | Qualitative | Co-produced mental health content for nursing students | Mental health |

Methodological Views on service user involvement in mental health nursing education; value of lived experience in improving mental health nurses education |

Co-production Focus groups |

Involvement at all project stages | * | Erasmus+ | |

| Horgan 2020 [57] |

University Ireland/global |

To develop standards to underpin expert-by-experience involvement in mental health nursing education based on lived experience of service use |

Qualitative Service users, nursing academics |

Standards for co-producing mental health nursing education | Mental health |

Methodological Enablers and barriers to involving experts by experience in nursing education; framework to support this involvement |

Co-production Focus groups Consensus-building discussion |

Involvement at all project stages Joint decision-making Continuous reflection |

* | Erasmus+ | |

| Hannigan 2018 [58] |

University Ireland |

To use a participatory health research approach to involve communities in examining the implementation of ethnic identifiers in primary care |

Qualitative Researchers, community members, decision-makers |

Ethnic identifiers in primary care | Public health |

Health Understanding and addressing inequalities among minority and majority ethnic groups in access to healthcare and health outcomes |

Co-construction Co-creation Participatory learning and action techniques Focus groups Interviews |

Involvement at all project stages Joint decision-making Sharing of power |

Health Research Board | ||

| Hundt 2019 [59] |

University Warwick |

To critically analyse the co-production of knowledge on healthcare with members of the public attending two research-based plays that were followed by post-show discussions with expert panellists |

Evaluation (mixed-method) Academics, health and social care professionals, service users, theatre directors and writers |

Two research-based plays on decision-making towards the end of life (Passing On) and mental health (Cracked) | Applied health research |

Impact Effect of dialogue between different stakeholders in co-production of knowledge; understanding of the health topics; views on inclusion of service users’ perspectives and experiences; enhanced public engagement |

Co-production Interviews Developmental drama workshops Discussion and debate |

NR | * | University, ESRC, Wellcome | |

| Leask 2019 [60] |

University Glasgow/global |

To identify a key set of principles & recommendations for co-creating public health interventions |

Case study End users, stakeholders, researchers |

To identify a key set of principles and recommendations for co-creating public health interventions | Public health |

Methodological Development of a framework of principles to facilitate co-creation Output Five key principles: framing the aim of the study; sampling; manifesting ownership; defining the procedure; and evaluating (process and intervention) |

Co-creation Action research reflective cycles conducted electronically and face to face |

Co-creation principles agreed | * | * | No funding |

| Litchfield 2018 [61] |

University Birmingham |

To use co-design principles to source, implement and evaluate improvements in the blood test and result communication process in United Kingdom primary care |

Evaluation (mixed-method) Staff and patients |

Interventions to improve the blood testing and result communication process | Primary care |

Methodological Situational and organizational barriers; participant experiences and influence on service improvement |

Co-design Focus groups with staff and patients mixed |

Co-design principles mentioned (not elaborated) | * | * | NIHR |

| Lloyd-Williams 2019 [62] |

University Liverpool |

To evaluate stakeholder involvement in the process of building a decision support tool |

Observational NHS commissioners, GPs, local authorities, academics, third-sector and national organizations |

NHS Health Check Programme | Health services research |

Impact Stakeholder views, experiences, expectations |

Co-production Iterative workshops e-platform |

Co-production principles mentioned (not elaborated) | NR | ||

| Luchenski 2019 [63] |

University London |

To explore involving nonacademic communities in co-developing research priorities, with particular emphasis on traditionally excluded groups |

Qualitative People with experience of exclusion, representatives from the NHS, charities, national, regional and local government and academic institutions |

An advocacy agenda for Inclusion Health | Health inequalities |

Methodological Making PPI more inclusive to excluded groups |

Co-production One-day event with inclusive, participatory and consensus-building activities |

Co-production approach mentioned (not elaborated) | * | * | University Grand Challenges |

| Marent 2018 [64] |

University Brighton/global |

To use a reflexive approach to evaluate a co-designed mHealth platform for HIV care |

Evaluation Clinicians, patients |

A digital HIV/AIDS support & self-management platform | HIV/AIDS |

Conceptual How a reflexive approach can generate understanding & anticipation towards a new intervention Output An mHealth platform for health monitoring |

Co-design Peer-led co-design workshops Interviews |

NR | * | * | EU |

| Miles 2018 [65] |

University London |

To discuss how “slow co-production” is an underused but valuable tool for co-production in healthcare design |

Qualitative Young people with sickle cell and their carers, healthcare providers |

This Sickle Cell Life: co-produced research to improve child-to-adult sickle cell patient care transitions | Health services research |

Methodological How slow co-production, with content led by priorities of patient, enables deeper insights and better service improvement |

Co-production Repeated interviews & participant diaries with young people Interviews with healthcare providers |

Involvement at all project stages | * | * | NIHR |

| O'Connor 2020 [66] |

University Edinburgh |

To explore the perspectives of stakeholders involved in co-designing a mobile application with people with dementia and their carers |

Qualitative People with dementia and their carers, a museum, a software company, and an NHS Trust |

App to support communication between carers and people with dementia (Innovate Dementia) | Older people |

Methodological Experiences of being involved in co-design Impact Value of the health app Health Health and well-being benefits |

Co-design Living laboratories Interactive co-design workshops |

NR | * | * | Burdett Trust |

| Pallensen 2020 |

University Ireland |

To evaluate stakeholder experiences of the co-design process |

Qualitative Researchers, healthcare providers, a patient representative |

Team-based Collective Leadership and Safety Culture (Co-Lead) programme to improve performance and patient safety | Health services research |

Methodological Expectations for and experiences of the process; positive aspects and challenges; decision-making process; learning and impact |

Co-design Workshops involving researcher inputs, experience-sharing and co-design |

Collective leadership | * | * | Irish Health Research Board |

| Patel 2018 [67] |

Public Health England London |

To pilot co-production, delivery and evaluation of oral care training for care home staff |

Qualitative Care home managers, residents and family members |

Oral health training DVD for care home staff; training resources; oral care support sessions | Older people |

Impact Oral health knowledge; views on training; areas for improvement |

Co-production Action research Questionnaire and interview with care home managers Informal discussions with residents and family |

Including all perspectives Respecting & valuing all contributions |

* | NR | |

| Ponsford 2021 [68] |

University London |

To describe the approach to co-producing two whole-school sexual health interventions for United Kingdom secondary schools |

Qualitative Researchers, secondary school staff and students, youth and policy and practitioner stakeholders in sexual health |

Positive Choices aimed at preventing unintended teenage pregnancy Project Respect aimed at preventing dating and relationship violence and sexual harassment in schools |

Adolescent health |

Output Two teacher-led, classroom-based sexual health interventions Methodological Description of stakeholder consultation to inform intervention development; challenges and dilemmas encountered; extent of co-production |

Co-production Consultation meetings with students and staff using small group working Meetings with youth group Meetings with policy-makers & practitioners |

NR | * | * | NIHR |

| Rodriguez 2019 [69] |

University Dundee |

To develop co-design, implement and evaluate a series of oral health workshops with young people experiencing homelessness |

Qualitative Nongovernmental organization managers and staff, practitioners, homeless young people |

Eight workshops raising health awareness, including oral health, mental health, substance abuse and healthy eating | Oral health |

Impact Changes in behaviour, knowledge, health literacy, engagement with service providers Methodological Workshop experience; common positive elements of workshops |

Co-design Action research Meetings Workshops Interviews |

Mutual trust Joint decision-making |

* | * | Scottish Government and Health Service Board |

| Scott 2020 [70] |

University Dundee |

To co-design and evaluate an animated film promoting oral health |

Evaluation (mixed-method) Parent–child dyads |

Short, animated film promoting oral health | Oral health |

Impact Oral health knowledge Feedback on film content, messages and visuals Output Short film promoting oral health |

Co-design Workshops including an activity sheet, ranking exercise and feedback on storyboards and animated films Interviews with parents Questionnaire |

Co-design and co-creation strategies mentioned (not elaborated) | * | * | Public Health England |

| Tribe 2019 [71] |

University London |

To discuss examples of co-produced mental health training, working with refugee or migrant community groups |

Qualitative Academics, practitioners, community workers |

Training for staff in a United Kingdom refugee community centre Training workshop in Sri Lanka to develop skills for coping while living in a war zone |

Mental health |

Health knowledge and well-being Impact Contribution of co-production and partnership working to knowledge and practice |

Co-production Meetings Workshop Interviews |

NR | * | NR | |

| Whitham 2019 [72] |

University Lancaster |

To discuss risks and benefits of co-designing tools for use by practitioners and implications for sustainability and impact of co-design initiatives |

Case study Health and social care staff and service uses |

Tools to improve difficult conversations in health and social care practice (Leapfrog tools) | Health and social care |

Output Conversation tools for use by practitioners Impact Risks and benefits of co-designing tools for use by practitioners; sustainability of co-design initiatives |

Co-design Participatory action research Tool co-design activities Sharing activities to disseminate tools Evaluation activities |

Including all perspectives Sharing of power |

* | * | Arts and Humanities Research Council |

| Systematic or evidence reviews or overviews (n = 10) | |||||||||||

| Ball 2019 [73] |

Nonprofit organization Cambridge |

To review the evidence base on patient and public involvement (PPI) in research, in order to determine what is known in and where there are gaps | Rapid evidence review | NA | Health services research |

Impact Challenges to PPI Impact of PPI |

Various | NA | * | THIS Institute | |

| Barnett 2020 [74] |

University United Kingdom/global |

To discuss key challenges relating to interdisciplinarity, epidemiology, participatory epidemiology, including the meaning of co-production of knowledge | Review | NA | Public health—One Health |

Conceptual Understanding what co-production means in relation to knowledge production in One Health Methodological Challenges in doing co-production working across disciplines and cultures |

Co-production | NA | * |

Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council UK Research and Innovation |

|

| Bench 2018 [75] |

University London |

To synthesize current evidence on best practice for PPI within critical care | Scoping review | NA | Critical care |

Impact Levels of involvement Involving critical care patients Barriers to/facilitators of PPI |

Various | NA | * | * | NIHR |

| Connolly 2020 [76] |

University W Scotland |

To learn how co-production and co-creation is understood, implemented and sustained within the health and social care system in Scotland | Rapid evidence review | NA | Health & social care services |

Impact Impacts pf co-production and co-creation on service improvements; evidence of effectiveness; barriers to & facilitators of co-production; sustainability of co-production and co-creation |

Co-production Co-creation in health & social care services |

NA | * | * | Scottish Improvement Science Collaborating Centre (SISCC) |

| Green 2020 [77] |

University Global |

To examine the use (structure, process and outcomes) and reporting of EBCD in health service improvement activities | Systematic review | NA | Health services research |

Methodological Use of EBCD (structure, process, outcome) Reporting of EBCD in health service improvement projects |

EBCD | NA | * | * | University |

| Halvorsrud 2021 [16] |

University NHS Trust London |

To investigate the effectiveness of co-creation/production in international health research | Systematic review | NA | Public health |

Impact Effects on health behaviours, service use and physical health Methodological Process elements in effective projects |

Co-creation Co-production |

NA | * | * | Lankelly Chase Foundation |

| Pearce 2020 [78] |

University United Kingdom/Australia |

To propose a new definition of co-creation of knowledge based on the existing literature | Literature Review | NA | Health research |

Conceptual New definition of co-creation of new knowledge for health interventions |

Co-creation | NA | * | * | Australian government scholarship |

| Sherriff 2019 [79] |

University Brighton |

To determine what is known about healthcare inequalities faced by LGBTI people, the barriers faced whilst accessing healthcare, and by health professionals when providing care, and examples of promising practice | Rapid reviews co-produced with LGBTI people | NA | Health inequalities |

Health Inequalities and barriers to accessing healthcare |

Co-production | NA | European Parliament | ||

| Slattery 2020 [15] |

University Global |

To identify the current approaches to research co-design in health settings and evidence of their effectiveness | Rapid evidence review | NA | Health services research |

Conceptual Co-design approaches and activities Methodological Effects of existing co-design approaches |

Co-design | NA | * | Transport Accident Commission | |

| Tembo 2019 [80] |

University Southampton |

To explore whether and how the public can be involved in the co-production of research commissioning early on in the process | Literature review | NA | Health research |

Conceptual Whether and how public can be involved in research commissioning Impact Challenges to public involvement in early phase of applied health research |

Co-production | * | * | NIHR | |

| Critical reflection or opinion (n = 20) | |||||||||||

| Beresford 2019 [81] |

University Essex |

To put public and user involvement in health and social care into broader historical, theoretical and philosophical context | Commentary | NA | Health research |

Impact Identifies four key stages in development of public participation in health and social care; barriers/challenges to public participation; successful participation in learning & training and in research knowledge production |

Co-production | NA | * | * | NR |

| Dowie 2018 [82] |

University London |

To elaborate the implementation of apomediative (“direct-to-consumer”) decision support tools—used by individuals to help make healthcare decisions for themselves—through the technique of multi-criteria decision analysis | Commentary | NA | Public health |

Conceptual Importance of shared decision-making between patient and professional about healthcare, through the use of decision support tools |

Co-creation of health by patient and health professional |

NR | No funding | ||

| Green 2019 [13] |

University Essex |

To offer a global and provocative perspective on participation as emancipatory and reformative vs participation as a servant to neoliberal capital forces | Commentary | NA | Health services research |

Conceptual Theoretical critique of participation in healthcare Methodological Evidence about the potential for participation and co-production; realities and challenges in achieving co-production; ways to facilitate co-production |

Co-production | NA | * | * | NR |

| Fletcher 2020 [83] |

University Edinburgh |

To analyse how health research regulation is experienced by stakeholders in the United Kingdom | Delphi survey | NA | Health research (regulation) |

Impact Direct experience of health research regulation by researchers, regulators and experts |

Co-production Mentioned as an outcome not a process |

NA | * | Wellcome Trust | |

| Hoddinott 2018 [84] |

University Scotland/United Kingdom |

To outline how researchers can involve patients in funding applications and pitfalls to avoid | Opinion | NA | Applied health research |

Conceptual Definitions of patient and public involvement, co-design, co-production Methodological How to involve patients in research; opportunities and pitfalls |

Co-production Co-design |

NA | * | * | No funding |

| Kaehne 2018 [85] |

University Lancashire |

To outline current thinking on co-production in health and social care, examine challenges in implementing genuine co-production | Commentary | NA | Health and social care |

Conceptual Definitions and explanations of co-production Methodological Establishing parameters of a co-production model; barriers to co-production in health and social care |

Co-production | NA | * | * | NR |

| Kislov 2018 [86] |

University Manchester |

To explore different definitions and types, tensions and compromises, and implications of, analyse the factors influencing, and share personal experiences of co-production | Qualitative/participatory | Interactive workshop | Applied health research |

Conceptual Definitions and types of co-production of evidence in applied health research Methodological Tensions and compromises of doing co-production; factors influencing processes and outcomes of co-production |

Co-production | NA | * | * | NR |

| Kislov 2019 [87] |

University Manchester |

To explore the processes, mechanisms and consequences of co-production between researchers and practitioners as an approach facilitating the implementation of research in healthcare organizations |

Case study Producers and users of applied health research |

Four applied health research projects | Applied health research |

Conceptual Definition of co-production approaches Methodological Compromises and negative consequences of co-production of applied health research |

Co-production | NA | * | * | NR |

| Lambert 2018 [88] |

University London |

To explore the development of co-production and service user involvement in United Kingdom university-based mental health research | Commentary | NA | Mental health |

Conceptual How co-production of mental health policy, practice and research is conceptualized Methodological Implications of co-production; reflection on the practice of research co-production (process, barriers, outcomes) |

Co-production | NA | * | * | NR |

| Langley 2018 [89] |

University Sheffield |

To explore the different domains of influence of collective making from a knowledge mobilization perspective | Commentary | NA | Health and social care |

Conceptual How the “collective making” co-design model contributes to co-creation of knowledge |

Co-creation Co-design |

NA | * | * | NIHR |

| Lignou 2019 [90] |

University Oxford |

To describe how a co-produced public health intervention was developed | Commentary | NA | Mental health |

Conceptual Explains the application of the concept of co-production to mental health research in four iterative steps |

Co-production | NA | * | * |

NIHR Wellcome |

| Metz 2019 [91] |

University London/US |

To draw out the learning and reflect on the wider co-creation literature and debates | Opinion | NA | Health services research |

Conceptual Clarifying and characterizing the use of “co-creation” |

Co-creation | NA | * | NR | |

| Norton 2019 [92] |

University Ireland |

To give guidance on how to implement co-production within Irish mental health services | Opinion | NA | Mental health |

Conceptual Definitions, types, principles and models of co-production; barriers to co-production; how to implement co-production |

Co-production | NA | * | * | NR |

| Palumbo 2018 [93] |

University Europe |

To conceptually explore the risks of value co-destruction in the patient–provider relationship and suggest a theoretical framework containing implementation issues of health services’ co-production | Commentary | NA | Health services research |

Conceptual Definition and distinction between individual and organizational health literacy Output Framework of factors for effective health services co-production—including individual and organizational health literacy |

Co-production | NA | * | * | NR |

| Realpe 2018 [94] |

University Coventry |

To establish a working definition of the co-production of health | Commentary | NA | Health and social care |

Methodological Model of the co-production of health in consultations Skills of clinicians and patients, and the context and outcomes of co-productive consultations |

Co-production | NA | * | NR | |

| Rose 2019 [95] |

University London |

To examine the concept and practice of co-production in mental health | Commentary | NA | Mental health |

Conceptual Historicizing co-production Methodological Context of co-production; positionality and co-production; privilege in knowledge generation |

Co-production | NA | * | * | Wellcome |

| Smith 2020 [96] |

University Newcastle |

To examine how Lean methods can be implemented and used to engage stakeholders in defining value and systems and processes in healthcare | Commentary | NA | Health services research |

Methodological Structured methods for co-production engaged stakeholders to articulate their own value perspectives |

Co-design | NA | * | NR | |

| Syed 2019 [97] |

Government Global |

To outline a framework for facilitating co-creation of public health evidence | Commentary | NA | Public health |

Methodological Definition of co-creation; barriers and facilitators in use of public health evidence Output Evidence-informed public health conceptual framework |

Co-creation | NA | NR | ||

| Thompson 2020 [98] |

University Edinburgh |

To describe what form co-production is taking and why in the context of NHS Scotland | Commentary with case study | NA | Health services research |

Methodological Examples of co-production within healthcare in Scotland Conceptual Co-production in governance arrangements |

Co-design Co-governance |

NA | * | * | No funding |

| Wolstenholme 2019 [99] | Professional clinical association | London | To discuss what co-production is and the impact it can have by drawing on a Twitter chat on co-production and management of acute and long-term stroke | Opinion | NA | Acute care |

Methodological Conditions for co-production to happen; activities that support co-production and co-creation; involvement of creative practitioners to improve co-creation process |

Co-production Co-creation |

NA | * | NR |

NA not applicable, NHS National Health Service

aCo-production principles and features as defined by NIHR (https://www.learningforinvolvement.org.uk/?opportunity=nihr-guidance-on-co-producing-a-research-project)

bNR not reported

* Indicates when a paper reports research or methodology gaps and/or policy/practice implications

In column 2, the underlined text highlights the type of organisation. In column 8, the underlined text highlights the type of co-production used

Papers reporting co-production in applied health research (N = 64) included intervention development or evaluation studies (n = 34), systematic, scoping or rapid evidence reviews or literature reviews (n = 10) and critical reflection or opinion pieces (n = 20). Most studies describing intervention development were qualitative and concerned co-designing or co-producing research methods or tools, or exploring the feasibility or acceptability of co-produced knowledge or service improvements. Evaluations reported on the mechanisms, approaches and forms of co-produced research projects, or measured impact or effects of co-produced interventions or projects. The systematic, scoping and rapid evidence reviews summarized best practice, definitions, implementation and sustainability, reporting and effects of co-produced research. The opinion and reflection papers tended to summarize historical or theoretical perspectives on co-production or user involvement in research, as well as outlining current thinking, literature and debates relating to co-designed or co-produced research, while others offered opinion on how to realize co-production and tips for effective co-production of services and research.

The included studies represent a broad spectrum of health specialities or disciplines. For those reporting co-produced complex interventions, many of the reviews and opinion pieces related to health services research or biomedical research, while the intervention development studies were situated in public health (n = 2), acute and intensive care (n = 1), addiction and substance misuse (n = 1), older people (n = 1), chronic illness (n = 1), primary care (n = 1), social care (n = 1), maternal health (n = 1) and mental health (n = 1). The studies reporting co-production in applied health research were related to health services research (n = 21), or were conducted within specific specialities such as mental health (n = 19), public health (n = 7), health and social care (n = 4), older people (n = 3), critical or acute care (n = 2), health inequalities (n = 2), oral health (n = 2), primacy care (n = 1), HIV/AIDS (n = 1), chronic illness (n = 1) or adolescent health (n = 1).

A range of outcomes were reported across all studies including conceptual (e.g. defining or explaining some aspect of co-production), methodological (e.g. focused on the process of designing or carry out co-production), impact (e.g. challenges, barriers and facilitators of co-production, acceptability, cost or effectiveness of co-produced research) and health (e.g. impact of co-produced interventions on health outcomes). Many studies resulted in tangible outputs or products including toolkits, models, frameworks or principles (see Table 2). Five studies concerned with applied health research described co-production as a means for “knowledge mobilization” or “knowledge transfer”, including co-produced dissemination activities [53], public engagement for better understanding of health topics [59], co-production for facilitating research implementation [87], use of co-design for knowledge mobilization [89] and co-creation of public health evidence [97].

Overall, nine studies (47%) reporting on co-produced complex interventions and 12 (19%) of those reporting co-production in applied health research were funded or supported by the NIHR. Other funding sources for studies of co-produced complex interventions included PhD studentships or fellowships (n = 3), National Health Service (NHS) Trusts (n = 1), Medical Research Council (n = 2) or National Science Foundation (n = 1), or the funding source was not reported (n = 3). Funders of co-production in applied health research included Wellcome (n = 4), charities (n = 4), Scotland or Ireland health boards (n = 4), European Union or Erasmus+ (n = 4), United Kingdom Research Councils (n = 3), university/Grand Challenges (n = 2), other government funding (n = 2) and single-study funding by an NHS Trust, an Academic Health Science Network (AHSN), Public Health England or private/commercial funding. Five applied health research studies did not receive funding and 23 did not report the funding source.

In most studies reporting on the development or evaluation of co-produced interventions, the lead organizations were universities (8/10 complex interventions and 27/34 co-produced applied interventions). Very few were led or co-led by NHS Trusts (2/10 complex interventions and 4/34 applied interventions) [23, 29, 43, 46, 47, 55], one study was led by a community organization [26], and two co-produced applied interventions were led by independent service users or service user charities [48, 50].

Conceptualization and implementation of co-production

Fifty-five papers referred to co-production either independently or in conjunction with other terms such as PPI/E, co-creation or co-design (see Additional file 2). Twenty-three papers were concerned with either co-design or EBCD, 12 used the term co-creation, and 10 mentioned PPI/E. Sixty-eight papers reported their research as a single methodology (e.g. co-production, co-design, EBCD or co-creation), with the remaining 16 using a combination of these terms to describe their work (e.g. co-production/co-creation, co-production/PPI, co-production/co-design or co-creation/co-design).

Some papers were very explicit in the definition of their chosen term, whereas others opted to describe the term using references from pre-existing literature. A commonly referred to definition was that of PPI as defined by INVOLVE, a national advisory group for PPI: research being carried out “with” or “by” members of the public rather than “to”, “about” or “for” them” [100]. In some instances a distinction was made between PPI/E and other co-activities based on the level of “active involvement” or the presence of a shared-power dynamic, with PPI/E being seen as a more passive or advisory role with a lower share of power and control [34, 88, 95]. A number of authors, however, seemed to use the two terms interchangeably [53, 75, 81].

Co-production was the most widely used term, referring to both the co-production of research and the co-production of services. The concept of shared power was widely used when describing co-production and what it means to health research or service development [42, 52, 101]. In these definitions, and indeed many others, co-production implied the involvement of a variety of stakeholder groups (e.g. services users, charity representatives, healthcare professionals and academics) in multiple stages of the research process. Others, however, used co-production as an umbrella term encompassing all aspects of additional stakeholder involvement whether that be throughout the process or in a single stage of the research cycle. In their rapid review evaluating hospital tools and services that had been co-produced with patients, Lim et al. included “co-production (e.g. co-production, co-design… [and] co-creation)” in their search terms [32], which highlights its use as a catch-all term.

Co-design was usually used to refer to stakeholder involvement in the design process of user-friendly tools, interventions or initiatives. Emphasis was placed on the value that “experts by experience” (e.g. patients, services users or clinicians) can bring to the design process as equal partners, beyond user involvement or consultation [102]. Stakeholder groups involved in these co-design projects included patients, carers, healthcare professionals, service users, local people and software or technology developers [13, 43, 46, 49, 51, 54, 61, 103]. Another frequently mentioned term was EBCD, which was defined by Chisholm as “a service design strategy that facilitates collaborative work between professional staff and service users toward common goals” in every stage of the design process [46]. EBCD appears to be more often applied to service development, while co-design is more often referred to in research.

Where it was possible to discern how the concepts were enacted, the type of methods reported in papers describing co-production or co-design included individual interviews, group workshops, reflection and discussion meetings, focus group discussions, social media forums, surveys, or a mix of these activities [47, 48, 52, 55, 62, 63, 84] (see Table 2). While some papers described specific activities and participatory approaches used in co-design or co-production workshops or meetings [25, 30, 70, 72, 104], most did not elaborate on their methods. In studies describing intervention development or evaluation, we looked for reference to principles of co-production or co-design (defined by the NIHR1) and how they were enacted. Of the studies reporting development of complex interventions (n = 10) and studies reporting development of applied interventions (n = 34), the principles described most frequently as key features of the projects were “including all perspectives”, “respecting and valuing all contributions”, “joint decision-making” and “involvement of stakeholders at all project stages”. Very few papers referred explicitly to “sharing of power” among stakeholders, or the principles of “reciprocity” and “building and maintaining relationships”. Fourteen of the applied research intervention studies did not mention co-production principles at all, and seven stated that co-production or co-design principles or approaches were used or agreed on, but specific features were not described (see Table 2).