Keywords: angiotensin II, hypertrophy, nephrectomy, renal blood flow

Abstract

Although the molecular and functional responses related to renal compensatory hypertrophy after unilateral nephrectomy (UNX) has been well described, many aspects of these events remain unclear. One question is how the remaining kidney senses the absence of the contralateral organ, and another is what the role of the renin-angiotensin system is in these responses. Both acute anesthetized and chronic unanesthetized experiments were performed using the angiotensin II type 1 receptor blocker losartan and the renin inhibitor aliskiren to determine the contribution of the renin-angiotensin system to immediate changes and losartan for chronic changes of renal blood flow (RBF) and the associated hypertrophic events in male Sprague-Dawley rats. Chronic experiments used implanted RBF probes and arterial catheters for continuous data collection, and the glomerular filtration rate was determined by noninvasive transcutaneous FITC-sinistrin measurements. The results of the acute experiments found that RBF increased nearly 25% (4.6 ± 0.5 to 5.6 ± 0.6 mL/min/g kidney wt) during the first 15 min following UNX and that this response was abolished by losartan (6.7 ± 0.7 to 7.0 ± 0.7 mL/min/g kidney wt) or aliskiren (5.8 ± 0.4 to 6.0 ± 0.4 mL/min/g kidney wt) treatment. Thereafter, RBF increased progressively over 7 days, and kidney weight increased by 19% of pre-UNX values. When normalized to kidney weight determined at day 7 after UNX, RBF was not significantly different from pre-UNX levels. Semiquantification of CD31-positive capillaries revealed increases of the glomeruli and peritubular capillaries that paralleled the kidney hypertrophy. None of these chronic changes was inhibited by losartan treatment, indicating that neither the compensatory structural nor the RBF changes were angiotensin II type 1 receptor dependent.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY This study found that the immediate increases of renal blood flow (RBF) following unilateral nephrectomy (UNX) are a consequence of reduced angiotensin II type 1 (AT1) receptor stimulation. The continuous monitoring of RBF and intermittent measurement of glomerular filtration rate (GFR) in conscious rats during the 1-wk period of rapid hypertrophy following UNX provided unique insights into the regulation of RBF and GFR when faced with increased metabolic loads. It was found that neither kidney hypertrophy nor the associated increase of capillaries was an AT1-dependent phenomenon.

INTRODUCTION

Compensatory renal hypertrophy of the remaining kidney following unilateral nephrectomy (UNX) is imperative for the long-term maintenance of body fluid and electrolyte homeostasis. These mechanisms are important in many circumstances such as kidney donations for transplants, surgical ablations of renal tumors, and in various kidney diseases leading to reduced nephron numbers (1–4). Following UNX in male rats, nearly all of the rapid changes have been found to be due to tubular hypertrophy (3, 5), although in young rats as much as a 20–30% increase in cell number (6). The debate over how the remaining kidney detects the absence of the contralateral kidney and the mechanistic determinants of these compensatory responses has been of interest and studied for decades (3, 4, 7). Among the many proposed and much debated theories underlying many of these hypotheses is the evidence of increases of renal blood flow (RBF) (8, 9) and glomerular filtration rate (GFR) (10–12), which imposes increased tubular metabolic transport workloads related to enhanced tubular delivery of Na+, amino acids, lipids, or other substances. Others have examined factors related to reduced excretion of nitrogenous wastes as well as responses of the autonomic nervous system, endocrine responses, and intrarenal trophic factors and inhibitors (13, 14).

Compensatory renal hypertrophy is a complex and poorly understood process, and there are varying degrees of support for each of the proposed theories. One of the major questions that remains is what initially “triggers” the hemodynamic and tubular changes that follow UNX. This requires studies that can track moment-to-moment changes in these variables immediately following UNX and can continuously track the hemodynamic and GFR changes during the following days and weeks in the conscious state. In the present study, we hypothesized that the rapid reduction of circulating renin upon removal of a single kidney would result in immediate vascular dilation of the remaining kidney and thereby represent the initial signal for the hypertrophic events that follow. The contribution of angiotensin II (ANG II) was determined by comparing this response in the presence and absence of the ANG II type 1 (AT1) receptor blocker losartan. Aliskiren, a renin inhibitor, was also assessed for the acute phase response. Experiments were carried out in anesthetized Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats to obtain high-resolution temporal hemodynamic responses immediately following UNX using ultrasonic flow probes around the renal artery of the remaining kidney, and changes in GFR were determined at 20-min intervals by clearance of FITC-sinistrin (Fresenius Kabi, Linz, Austria). Since it is not possible to perform a nephrectomy in the absence of anesthesia, experiments first characterized these immediate events in anesthetized rats.

Another group of SD rats was surgically instrumented to measure the chronic changes of RBF and GFR that occur following UNX in normal rats and those treated chronically with losartan. Rats were chronically instrumented 7–10 days before UNX with implanted arterial catheters and ultrasonic flow probes to obtain continuous 24 h/day recordings of arterial pressure and RBF before and for 1 wk after UNX. Intermittent measurements of GFR were made in unanesthetized rats by determining the clearance of injected FITC-sinistrin by a transdermal optical LED device affixed to the back of the rat (15, 16). Histological experiments were carried out comparing the removed right kidneys with those of hypertrophied left kidneys at the end of the 7-day study to characterize the capillary microvascular density of glomerular and cortical peritubular capillaries.

METHODS

Animals

Male SD rats were purchased from Envigo (Indianapolis, IN) and housed in environmentally controlled rooms with a 12:12-h light-dark cycle. Rats had free access to Purina diet and water ad libitum. All protocols were approved by the Medical College of Wisconsin’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Acute RBF Measurement

SD rats (7 wk of age) were anesthetized with ketamine (20 mg/kg) and thiobutabarbital (25 mg/kg) and placed on temperature-controlled (37°C) surgical tables. PE-240 catheters were inserted into the tracheas to maintain respiration. PE-50 catheters were inserted into the left femoral vein for infusion and the left femoral artery to measure blood pressure (BP). PE-10 catheters were inserted into ureters bilaterally to collect urine from each kidney. The right kidney was placed in a kidney cup, and a 3-0 silk suture was placed loosely around the right renal artery and vein. Although evidence does not support the involvement of the sympathetic nervous system in the hemodynamic or hypertrophic responses following UNX (17), we nevertheless denervated the left kidney to eliminate any potential contributions of afferent or efferent neural signaling in the observed responses. As previously described, the left renal artery was exposed and denervated by swabbing 5% phenol and 70% ethanol (18), and an ultrasonic flow probe (Transonic System) was placed around the left renal artery. Left RBF and BP were measured and recorded by data-acquisition systems (Dataq). Saline containing 2.0% BSA was infused from the femoral vein catheter at a rate of 1.0 mL/100 g body wt/h. Following a 30-min equilibration period, either vehicle (saline control), 10 mg/kg of losartan (19), or 3 mg/kg of aliskiren (20) was injected intravenously, and monitoring was continued for another 60 min with the final two 15-min period averages used to represent baseline control values. The ligature around the right renal vessels was then firmly tied, and the right kidney was removed (UNX). RBF and BP were then continuously measured for 75 min.

Acute GFR Measurement

GFR was measured in the separate group of rats by FITC-sinistrin clearance as previously described (21). The surgical preparation was same as the description in Acute RBF Measurement. The left renal artery was denervated as described in Acute RBF Measurement. FITC-sinistrin (2 mg/mL) was dissolved in BSA saline and infused at 1.0 mL/100 g body wt/h. Following a 30-min equilibration period, urine was collected bilaterally from each kidney at 20-min intervals with 50 µL of blood collected for analysis from the arterial catheter at the 10-min midpoint of each urine collection period. After two 20-min periods of the baseline urine and blood collection, the right kidney was removed and the urine and blood were continuously collected for another 60 min. Fluorescent levels of FITC-sinistrin in the plasma and urine were determined using SPECTRAFluor Plus (TECAN, Männedorf, Switzerland) with an excitation wavelength of 485 nm and an emission wavelength of 530 nm.

Chronic RBF Measurement

The chronic RBF measuring system was custom built in our laboratory as described in previous studies (22–29). SD rats (5 wk old) were placed in the Raturn (BASi) designed to prevent twisting of the flow probe cable by moving counterclockwise to the motion of the rat. One week was given to acclimate to the motion of the cage before the implantation of the flow probe (Transonic). Rats were anesthetized with isoflurane, and before rats awakening, buprenorphine (0.09 mg/kg body wt) was injected subcutaneously. An arterial catheter was implanted for 24 h/day recordings of arterial pressure as we have previously described (22–28). The left renal artery was exposed and denervated by swabbing 5% phenol and 70% ethanol (18) along the vessel before placing the ultrasonic flow probe around the vessel. The connector cable was fixed to the abdominal wall, routed subcutaneously to the nap of the neck, and exteriorized along with the arterial catheter through a protective cantilevered tube at the top of the circular Plexiglas cage. The arterial catheter was attached to a swivel device, and the flow probe cable was connected to the flowmeter (model T402, Transonic). Following surgery, 0.5 g of hazelnut paste (Nutella, Ferrero USA) was administered immediately following surgery and every 12 h thereafter for 3 days. During the remainder of the one 7- to 10-day recovery period, Nutella was offered as a daily treat that rats eagerly consumed to which losartan (10 mg/kg) was added to the diet of half of the rats (losartan potassium, Sigma-Aldrich). Blood was then sampled from the femoral arterial catheter on days 3 and 4 after the start of losartan for the analysis of plasma renin activity (PRA). PRA was measured by ELISA (No. 80970, Crystal Chem, Elk Grove, IL).

Nephrectomy of the right kidney was then performed via a flank incision under isoflurane anesthesia on day 6 after the start of losartan. The entire procedure averaged 30 min with rapid awakening from the isoflurane, and the rat was then returned to its home cage for continued monitoring of RBF and mean arterial pressure (MAP). Blood was drawn via the femoral arterial catheter at 6 h, 24 h, day 3, and day 7 after nephrectomy. After 7 days of recording, the rat was anesthetized with isoflurane for the removal of the left kidney without flushing, which was hemisectioned and fixed with 10% neutral-buffered formalin for histological analyses and then divided into the cortex and medulla for RNA and protein analyses.

Chronic GFR Measurement

Chronic GFR was measured in a separate group of conscious, unrestrained rats using a miniaturized optical LED device affixed to the back of the rat that transcutaneously exited FITC-sinistrin at 480 nm and a photodiode that detected the emitted light at 521 nm as we have previously described (16, 30). Briefly, for 5-wk-old male SD rats, a femoral venous catheter was implanted and the left renal artery was denervated in advance. On the day of recording of GFR, a rodent jacket containing the device (diodes, microprocessor, and batteries) and optical components was affixed to a depilated region of the rat’s back. A bolus injection of FITC-sinistrin (15 mg/100 g body wt, dissolved in 0.5 mL sterile isotonic saline) was then administered via the femoral venous catheter. Measurements of FITC-sinistrin elimination were recorded every second from the cutaneous diodes for more than 120 min. GFR (mL/min/100 g body wt) was defined as 21.33 mL/100 g body wt, the conversion factor calculated by Friedemann et al. (31), divided by FITC-sinistrin half-life (min). GFR was measured 2 days before UNX and on days 2, 5, and 9 and then extended to day 14 to determine, since few changes occurred over the first week following UNX.

Morphometric Measurements of the Kidney and Glomeruli

Sections of kidneys collected on day 7 after UNX, which were hemisectioned parallel to the long axis, fixed and then paraffin embedded, were sectioned at a thickness of 4 μm and stained with Masson trichrome. The slides were scanned with a NanoZoomer digital slide scanner (Hamamatsu, Bridgewater, NJ), and the length of the major axis of the kidney was measured under the program of NDP.view2 (Hamamatsu). In each slide, at least 70 glomeruli were manually picked up under the NDP.view2 software, and glomerulus size including Bowman’s capsule was measured (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Examples of the measurements of the kidney major axis and glomerular size. Masson trichrome staining was used. Scale bars = 4 mm for the top image and 100 μm for the bottom image.

Semiquantification of Glomerular and Peritubular Capillary Density

Glomerular and cortical peritubular capillary density was determined using anti-CD31 (anti-endothelial cell) antibody (Cat. No. AF3628, R&D Systems, 1:100), which provided a clear visualization of the vascular endothelium and was semiquantified by Elements software (Nikon). Since the slides were not uniformly stained, a threshold value was set for each slide, and those vessels exhibiting a stronger signal than the threshold value were considered positive for staining. Specifically, glomerular capillary density was expressed by dividing the CD31-positive staining area with the total glomerular area in at least 50 glomeruli in each kidney. Peritubular density was similarly calculated after the glomerulus was masked, and the peritubular vessel area was determined in 20 random frames in the cortex as shown in Fig. 2 and in 10 random frames in the outer medulla.

Figure 2.

Examples of CD31 staining. Brown stains denote the CD31-positive area in the top image. When we measured peritubular capillary density, the glomerulus and larger vessels were manually masked as shown in light blue in the bottom image. Red stains denote the positive area above a set threshold. Scale bars = 100 μm.

Statistical Analysis

Rats were randomly allocated to each group. About 10% of the rats dropped out of the study due to poor postoperative recovery and were not included in the analysis. Analysis of tissue samples was performed blindly. Continuous values are presented as means ± SE. Statistical comparisons were made using ANOVA followed by a Holm-Sidak’s post hoc test for multiple between-group comparisons. P values of <0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

Immediate RBF and Arterial Pressure Responses to UNX in Vehicle- and Losartan-Treated Rats

The hemodynamic consequences of rapid removal of the right kidney upon RBF to the remaining kidney and MAP were determined as represented in a single rat in Fig. 3A. Shown are the pulsatile responses of RBF (mL/min) and arterial pressure (mmHg) immediately following UNX. RBF increased progressively over the first 15 min, whereas arterial pressure tended to fall. Average RBF and MAP responses of vehicle-treated rats (n = 7) compared with losartan- (n = 8) and aliskiren-treated rats (n = 6) are shown in Fig. 3, B and C. Since the timing and pattern of change were of special interest, RBF values were normalized to the combined average control value of both vehicle- and losartan- or aliskiren-treated rats. As shown in Table 1 and Fig. 3B, RBF measured continuously was significantly elevated in vehicle-treated rats as early as 15 min following UNX and continued to rise before reaching a plateau of 5.6 ± 0.6 mL/min/g kidney wt (24.2 ± 4.7%) above the pre-UNX control value of 4.6 ± 0.5 mL/min/g kidney wt. In contrast, RBF rose only slightly in losartan- or aliskiren-treated rats, although pre-UNX control RBF was higher than in vehicle-treated rats (6.7 ± 0.7 or 5.8 ± 0.4 vs. 4.6 ± 0.5 mL/min/g kidney wt). Changes in MAP are presented as percent changes to the control period in Fig. 3C to facilitate comparative differences between the vehicle- and losartan-treated groups. Pre-UNX levels of MAP in vehicle-treated rats averaged 104 ± 3 mmHg, in losartan-treated rats averaged 94 ± 2 mmHg (P < 0.05), and in aliskiren-treated rats averaged 100 ± 4 mmHg. Overall, immediately following UNX, there was a tendency for MAP to decrease in vehicle-treated rats and to increase in losartan- or aliskiren-treated rats, although these variations were not statistically significant. However, given the consistent increase of RBF in the vehicle-treated group, the calculated renal vascular resistance (RVR) was significantly reduced following nephrectomy. In the losartan- and aliskiren-treated groups, RBF remained unchanged following UNX with no change observed in the calculated RVR (Fig. 3D).

Figure 3.

Immediate renal blood flow (RBF) and arterial pressure responses to unilateral nephrectomy (UNX). A: representative RBF and blood pressure data (n = 1). B: change in RBF after UNX from the baseline expressed as a percentage. C: change in mean arterial pressure after UNX from the baseline expressed as a percentage. D: change in renal vascular resistance after UNX from the baseline expressed as a percentage. White circles indicate the vehicle-treated group (n = 6), black circles indicate the losartan-treated group (n = 8), and gray circles indicate the aliskiren-treated group (n = 6). Data are presented as means ± SE of every 15 min. *P < 0.05 vs. baseline (−15 to 0 min); †P < 0.05 vs. vehicle (Holm-Sidak’s test).

Table 1.

Immediate response of MAP and RBF after unilateral nephrectomy

| MAP, mmHg |

RBF, mL/min/g kidney wt |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Veh | Los | Ali | Veh | Los | Ali | |

| −30 to −15 min | 104 (3) | 94 (3) † | 97 (4) | 4.5 (0.6) | 6.6 (0.7) | 5.8 (0.4) |

| −15 to 0 min | 104 (3) | 94 (2)† | 100 (4) | 4.6 (0.5) | 6.7 (0.7) | 5.8 (0.4) |

| 0 to 15 min | 105 (3) | 96 (2) | 105 (4)* | 5.1 (0.6)* | 7.0 (0.7) | 5.6 (0.4) |

| 15 to 30 min | 104 (2) | 98 (2)* | 103 (4) | 5.6 (0.6)* | 7.0 (0.7) | 6.0 (0.4) |

| 30 to 45 min | 102 (2) | 95 (3) | 102 (4) | 5.6 (0.6)* | 7.0 (0.7) | 6.1 (0.4) |

| 45 to 60 min | 102 (2) | 96 (2) | 102 (4) | 5.6 (0.6)* | 7.1 (0.7) | 6.0 (0.4) |

| 60 to 75 min | 103 (2) | 96 (2) | 102 (4) | 5.8 (0.7)* | 7.0 (0.7) | 6.0 (0.4) |

Values are means (SE). Nephrectomy was done at 0 min. Ali, aliskiren; MAP, mean arterial pressure; min, number of minutes after nephrectomy; RBF, renal blood flow; Veh, vehicle; Los, losartan.

*P < 0.05 vs. −15 to 0 min;

†P < 0.05 vs. Veh (Holm-Sidak’s test).

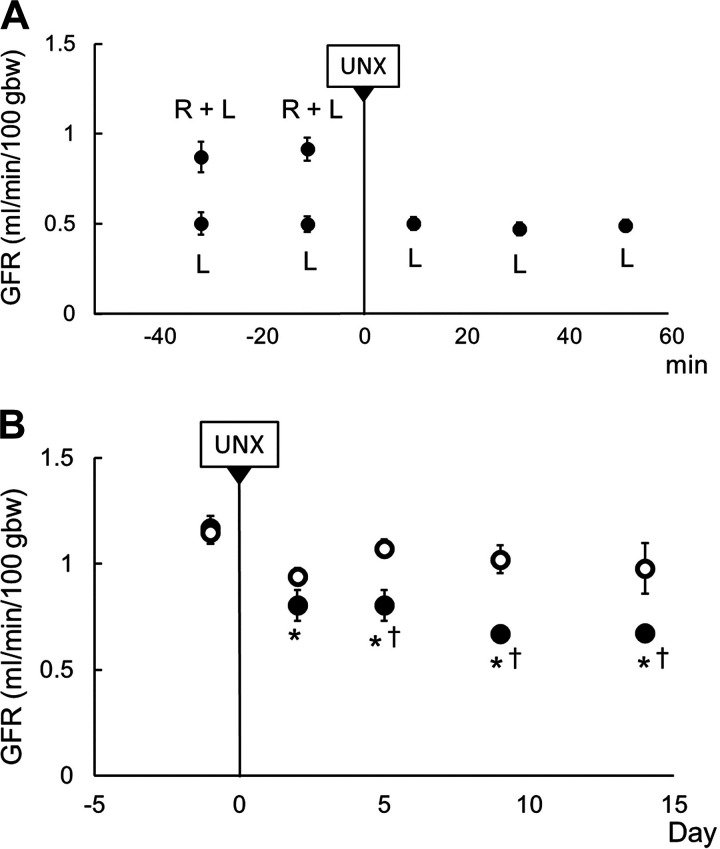

Immediate and Chronic GFR Responses Following UNX in Normal SD Rats

Figure 4A shows the changes in whole body GFR before (right kidney + left kidney) and following UNX (left kidney) determined by separate bilateral ureteral urine collections in anesthetized rats (n = 12). Total body clearance of FITC-sinistrin (e.g., GFR) was reduced to nearly half [0.91 ± 0.06 (right kidney + left kidney) to 0.50 ± 0.04 (left kidney) mL/min/100 g body wt] during the initial 15 min following UNX. No changes were observed in the remaining left kidney during the 60 min following UNX despite the increase of RBF.

Figure 4.

Immediate and chronic glomerular filtration rate (GFR) responses to unilateral nephrectomy (UNX). A: immediate change of GFR presented as means ± SE of every 20 min, n = 12. B: chronic changes of GFR at days 2, 5, 9, and 14 after UNX. White circles indicate the sham group (n = 5) and black circles indicate the UNX group (n = 8). *P < 0.05 vs. before UNX; †P < 0.05 vs. sham (Holm-Sidak’s test). gbw, grams body weight; L, remaining left kidney; R, removed right kidney.

Figure 4B shows whole body GFR data obtained in unanesthetized UNX or sham-prepared rats as determined by the net clearance of FITC-sinistrin (GFR). Following UNX, GFR of UNX rats (n = 7) decreased from 1.17 ± 0.17 to 0.80 ± 0.07 mL/min/100 g body wt (P < 0.05) as determined on the second day following surgery and remained at these levels, representing a 32% reduction from control over a 2-wk period.

Chronic Renal Hemodynamic Experiments Following UNX

Figure 5A shows the continuous (24 h/day) recording of MAP and RBF in a representative single SD rat before and after UNX. The recording was interrupted for 30 min during the removal of the right kidney, whereas the rats were briefly anesthetized with isoflurane and given 0.09 mg/kg body wt buprenorphine and then returned to their home cage to resume recording. As shown in this individual rat, RBF and MAP were increased following UNX. Table 2 shows average daily 24-h MAP, RBF, and calculated RVR determined before (control) and after UNX in vehicle- and losartan-treated rats. In vehicle-treated rats, MAP progressively rose from 113 ± 1 to 119 ± 1 mmHg at day 4 (P < 0.05) and then plateaued, whereas in losartan-treated rats, MAP remained within 3 mmHg of the control value throughout the study (control: 105 ± 2 mmHg compared with 108 ± 2 mmHg at day 7). Average daily RBF (not adjusted for kidney weight) of both vehicle- and losartan-treated rats gradually rose from 6.4 ± 0.8 to 9.1 ± 0.7 mL/min (P < 0.05) and from 6.8 ± 0.5 to 9.8 ± 0.6 mL/min (P < 0.05), respectively, by day 7 after UNX. Calculated RVR determined as average 24-h MAP/RBF was significantly reduced (P < 0.05) by day 2 after UNX in vehicle-treated rats and by day 4 in losartan-treated rats.

Figure 5.

Chronic change in renal blood flow before and after unilateral nephrectomy (UNX). A: representative renal blood flow and blood pressure data (n = 1). B: 24-h average of mean arterial pressure data before UNX (Pre UNX) and 7 days after UNX (Post UNX). C: 24-h average of renal blood flow data normalized by kidney weight before and 7 days after UNX. Means ± SE and individual data are presented. D: 24-h average of renal vascular resistance normalized by kidney weight before and 7 days after UNX. E: plasma renin activity of the vehicle-treated group (n = 7). Means ± SE and individual data are presented. *P < 0.05 vs. Pre UNX; †P < 0.05 vs. Veh (Holm-Sidak’s test). gkw, grams kidney weight; Los, losartan-treated group (n = 6); Veh, vehicle-treated group (n = 7).

Table 2.

Twenty-four hour/day average of MAP, RBF, and RVR after unilateral nephrectomy

| MAP, mmHg |

RBF, mL/min |

RVR, mmHg/mL/min |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Veh | Los | Veh | Los | Veh | Los | |

| Control | 113 (1) | 105 (2)† | 6.4 (0.8) | 6.8 (0.5) | 19.2 (2.3) | 15.9 (1.5) |

| Day 1 | 116 (1) | 105 (3)† | 6.8 (0.7) | 7.1 (0.4) | 18.4 (2.1) | 15.0 (0.9) |

| Day 2 | 114 (2) | 105 (2)† | 7.4 (0.7)* | 7.6 (0.5) | 16.2 (1.5)* | 14.1 (1.0) |

| Day 3 | 116 (2) | 107 (2)† | 7.7 (0.6)* | 7.8 (0.4)* | 15.6 (1.3)* | 13.8 (0.6) |

| Day 4 | 119 (2)* | 109 (2)† | 8.2 (0.7)* | 8.3 (0.5)* | 15.1 (1.2)* | 13.2 (0.5)* |

| Day 5 | 119 (2)* | 108 (2)† | 8.6 (0.7)* | 8.8 (0.6)* | 14.4 (1.2)* | 12.4 (0.6)* |

| Day 6 | 119 (2)* | 109 (2)† | 9.0 (0.7)* | 9.6 (0.5)* | 13.8 (1.1)* | 11.5 (0.4)* |

| Day 7 | 119 (1)* | 108 (2)† | 9.1 (0.7)* | 9.8 (0.6)* | 13.7 (1.1)* | 11.2 (0.5)* |

Values are means (SE). Control, prenephrectomized control period; Los, losartan; MAP, mean arterial pressure; RBF, renal blood flow; RVR, renal venous resistance; Veh, vehicle.

*P < 0.05 vs. control;

†P < 0.05 vs. Veh (Holm-Sidak’s test).

Figure 5, B–D, shows a different picture of these hemodynamic responses to UNX, which emerged when 24-h average (pre-UNX: on the day before UNX, post-UNX: on day 7) RBF was factored by the hypertrophic response of the remaining left kidney. Figure 5B shows average 24-h MAP in vehicle- and losartan-treated rats. A moderate but significant increase of MAP was observed in vehicle-treated rats, rising from 113 ± 1 to 119 ± 1 mmHg (P < 0.05) following UNX. MAP of losartan-treated rats averaged 105 ± 2 mmHg during the control period and was slightly increased at day 7 (108 ± 2 mmHg) following UNX. Most importantly, Fig. 5C shows RBF data when normalized by kidney weight (pre-UNX determined by the right kidney weight upon removal) and the left kidney weight determined at day 7 after UNX. When factored by the increased left kidney weight that occurred following UNX, RBF appeared unchanged at day 7 in vehicle-treated rats (6.2 ± 0.7 to 6.7 ± 0.5 mL/min/g kidney wt) and in losartan-treated rats (7.1 ± 0.5 to 7.5 ± 0.5 mL/min/g kidney wt). RVR also remained unchanged when factored by the increased kidney weights of these rats (Fig. 5D). This parallel increase of RBF and kidney weight and the observation that losartan did not change this relationship suggest that neither compensatory renal hypertrophy nor the changes in RBF and RVR were affected by inhibition of the AT1 receptor.

PRA was not determined during the first 60 min following UNX to avoid removal of blood (∼200 µL) required for the assay, which could alter renal hemodynamic events. Removal of nearly 50% of the major source of circulating renin with UNX together with the finding that losartan or aliskiren pretreatment prevented the observed increase of RBF indicates the importance of the renin-angiotensin system (RAS) in these hemodynamic responses. Chronically, plasma renin levels determined 24 h following UNX (1.5 ± 0.2 ng/mL/h) did not differ from those obtained before surgery and remained at these normal levels throughout the week, indicating that the remaining kidney rapidly compensated for the loss of the contralateral kidney (Fig. 5E). As anticipated, PRA of the losartan-treated group was very elevated (>63 ng/mL/h on the standard curve; data not shown). It may be noted that blood samples obtained in the 5- to 6-h period following UNX were extremely variable and could not be usefully interrupted.

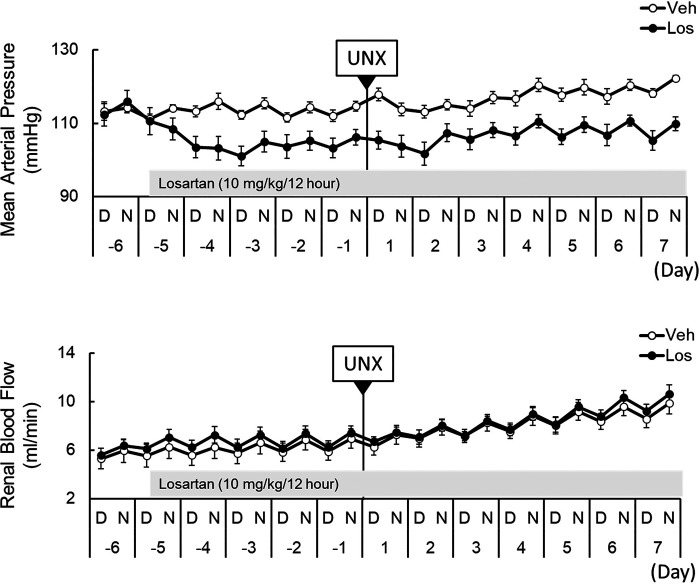

Effects of UNX Upon Arterial Pressure and RBF Diurnal Rhythms Following UNX

Figure 6 shows 12-h average levels of simultaneously recorded MAP and RBF of the left kidney in normal SD rats before and following UNX, in the absence and presence of losartan. Although the present study was not intended to address mechanisms of circadian rhythms, these data are the first observations of the effects of UNX upon the diurnal rhythm of RBF and the effects of losartan upon these daily cycles. Presented are the average 12-h dark period (night) and inactive 12-h light period (daytime). Several interesting features were observed. First, a close parallelism of MAP and RBF was apparent in normal rats during the pre-UNX period. Second, UNX resulted in no detectable disruption of the diurnal patterns of RBF in vehicle-treated rats (n = 7). The pattern of MAP was lost during the first day following UNX, but thereafter the synchronized rhythms of both MAP and RBF returned to normal pre-UNX levels. Third, losartan treatment resulted in no alterations of diurnal rhythms of either MAP or RBF, although clear reductions of MAP (∼10 mmHg, P < 0.05) and increased RBF were apparent throughout the study.

Figure 6.

Effects of unilateral nephrectomy (UNX) upon arterial pressure and renal blood flow diurnal rhythms following UNX. Progressive changes of 12-h averages of mean arterial pressure and renal blood flow are presented as means ± SE. D, daytime; Los, losartan-treated group (n = 6); N, nighttime; Veh, vehicle-treated group (n = 7).

Kidney Size and Weight Responses Following UNX in Vehicle- and Losartan-Treated Rats

Figure 7A shows changes of the length of the major axis (see Fig. 1) of the right kidneys at the time of UNX and that of the remaining left kidneys on day 7 following UNX. The vehicle-treated group increased from 16.9 ± 0.4 to 20.1 ± 0.6 mm (P < 0.05) and the losartan-treated group increased from 16.3 ± 0.4 to 19.1 ± 0.3 mm (P < 0.05). Figure 7B shows a comparison of the weights and sizes of the nephrectomized right kidneys to the remaining left kidneys of vehicle- and losartan-treated rats on day 7 following UNX. The ratio of the kidney weights to the body weight of vehicle-treated rats increased from 4.41 ± 0.14 to 5.59 ± 0.09 g kidney wt/kg body wt following UNX (n = 7, P < 0.05), and a similar increase was observed in losartan-treated rats (4.49 ± 0.17 to 5.50 ± 0.10 g kidney wt/kg body wt, n = 6, P < 0.05). Figure 7C shows the average area of the glomerulus, which was significantly increased in both the vehicle-treated group (0.0113 ± 0.0006 vs. 0.0127 ± 0.0005 mm2) and losartan-treated group (0.0115 ± 0.0005 vs. 0.0126 ± 0.0001 mm2), with no significance between vehicle- and losartan-treated groups. There is, therefore, no evidence from these analyses that the enlargement of the kidney and glomeruli following UNX is dependent upon AT1 receptor-mediated pathways. Kidney size was also measured on day 2 following UNX in another group of rats (Fig. 8), and it was found at this early time point following UNX that the kidney-to-body weight ratio increased from 4.15 ± 0.12 to 4.58 ± 0.12 g kidney wt/kg body wt in vehicle-treated rats (n = 6, P < 0.05) and from 4.09 ± 0.10 to 4.62 ± 0.09 g kidney wt/kg body wt in losartan-treated rats (n = 6, P < 0.05), with no statistical difference between the groups.

Figure 7.

Change in kidney size and vasculature 7 days after unilateral nephrectomy (UNX). A: average length of the kidney major axis (in mm). B: average kidney weight [in grams kidney weight (gkw)]/body weight [in kg body weight (kgbw)]. C: average glomerular size (in mm2). D: average glomerular CD31-positive area (in μm2). E and F: average cortical CD31-positive area (in %; E) and average medullary CD31-positive area (in %; F) presented as means ± SE and individual data. Means ± SE and individual data are presented. *P < 0.05 vs. Pre UNX (Holm-Sidak’s test). Los, losartan-treated group (n = 6); Pre UNX, before nephrectomy; Post UNX, 7 days after nephrectomy; Veh, vehicle-treated group (n = 7).

Figure 8.

Kidney size 2 days after unilateral nephrectomy (UNX). Average kidney weight [in grams kidney weight (gkw)]/body weight [in kg body weight (kgbw)] is presented as means ± SE and individual data. Means ± SE and individual data are presented. *P < 0.05 vs. Pre UNX (Holm-Sidak’s test). Los, losartan-treated group (n = 6); Pre UNX, before nephrectomy; Post UNX, 2 days after nephrectomy; Veh, vehicle-treated group (n = 7).

Glomerular and Peritubular Capillary Density in Vehicle- and Losartan-Treated Rats

Figure 7D shows average endothelial marker CD31-positive glomerular area determined in ∼50 glomeruli of each kidney. Following UNX, by day 7, the average glomerular CD31-positive area of the remaining kidney was significantly increased in both the vehicle-treated group (3,434 ± 310 vs. 4,046 ± 364 μm2) and losartan-treated group (3,389 ± 135 vs. 3,975 ± 145 μm2). No difference was observed between the groups. Figure 7, E and F, shows the effects of UNX upon peritubular capillary density in the cortex and outer medulla determined at day 7 after UNX in vehicle- versus losartan-treated rats. Peritubular capillary density was unchanged in either the cortex or outer medulla despite hypertrophy of the area, suggesting that the capillary network spread in parallel with the kidney hypertrophy. Losartan again had no effect on either glomerular or peritubular capillary density.

DISCUSSION

The present study focused on the complex mechanisms responsible for kidney hypertrophy following UNX. The main goal of the study was to determine the involvement of the RAS in the initiation of hemodynamic changes observed in the remaining kidney following UNX and then in the ensuing days as the remaining kidney undergoes hypertrophy. The study determined the immediate 30-min responses of MAP, RBF, and GFR to UNX in anesthetized rats. The following events associated with the hypertrophic response of the remaining kidney were determined in chronically instrumented unanesthetized rats.

Several novel observations resulted from the results of the present study. First, it was clearly established that the rapid increase in RBF following UNX was the consequence of the reduction of the intrinsic AT1 receptor-mediated control of RVR. The reported half-life of 4–14 min of circulating renin (32) coincided with the rate of rise of the RBF of the remaining kidney following UNX. In the presence of the AT1 receptor antagonist losartan, there was no acute increase in RBF following UNX. Second, following the initial rapid increase of RBF, the kidney blood flow rose progressively during the week following UNX, which was not AT1 dependent. Third, this was associated with an increase in the microvascular density of the glomerulus and the peritubular microvessels of the cortex and outer medulla. Fourth, the immediate 50% reduction of total GFR following UNX was followed by a return to 70% of pre-UNX levels during the first week following UNX, which was consistent with the increase of glomerular capillary density observed at day 7, which is not AT1 receptor dependent.

Role of the RAS in the Immediate Increase of RBF Following UNX

Evidence of a circulating factor being importantly involved in the acute phases of kidney hypertrophy was initially obtained from a parabiotic study in rodents (33). Kidney hypertrophy and cell proliferation were observed after the injection of serum from nephrectomized rats (34). These and other similar observations led to the “renotrophic” theory of hypertrophy (14). It was logical to propose that the rapid reduction of PRA following UNX was the circulating factor responsible for the rapid increase of RBF since RAS inhibition is known to increase RBF in anesthetized rats (35). The present study found that the rapid increase of RBF following UNX did not occur when rats were pretreated with either losartan or aliskiren, which is best explained by a reduction of circulating renin and reduced AT1 receptor stimulation within the remaining kidney. If other mechanisms were contributing to this increase of RBF in addition to the reduction of circulating ANG II, one would expect to see some increase of RBF in losartan- or aliskiren-treated rats. Alternatively, one could argue that the kidney was maximally vasodilated in the presence of these drugs. This we believe is unlikely, since RBF of anesthetized rats has been reported to increase to levels exceeding 55% of the control with other vasodilator agents such as observed with inhibitors of 20-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid and epoxyeicosatrienoic acids (36), whereas a 28% increase was observed in the present study in response to UNX. These data support our conclusion that the fall of plasma ANG II is the mechanism responsible for the immediate increase of RBF following UNX.

Lack of RAS Involvement in the Chronic Increases of RBF Following UNX

In contrast to the critical role of the RAS in immediate renal hemodynamic responses following UNX, a reduction of the RAS does not appear to be responsible for the sustained and progressive increase of RBF in the week following UNX, nor is the RAS responsible for the hypertrophy of the kidney observed at days 2 and 7 following UNX (Figs. 7B and 8). At both the early and later time points, losartan-treated rats exhibited the same increases of RBF and kidney hypertrophy as untreated rats. Curiously, the literature is conflicting on the issue of hypertrophy with some concluding that RAS inhibition prevents hypertrophy (37, 38), whereas others are consistent with our observations that RAS inhibition has no effect on hypertrophy (39).

Possible Mechanisms Responsible for a Progressive Increase of RBF and Reduced RVR

The slow progressive rise of RBF during the first week following UNX has not been previously observed since continuous flow monitoring has not been carried out. The possibility that this may be the consequence of increased capillary vascularity in the remining kidney was examined. It was found that capillary density in both the glomeruli and cortical peritubular regions were elevated relative to the hypertrophic response of the kidney whereby capillary density remained unchanged per unit area. Accordingly, the total area occupied by the capillaries in both glomerular and peritubular capillaries was significantly increased enabling greater blood flow to the kidney cortex, as shown in Fig. 6. Importantly, neither the increase of RBF nor the enhanced capillary density was affected by chronic losartan treatment. The morphological changes related to the increased capillary density were not determined. Olivetti et al. (40) speculated that the increase in capillaries in the glomerulus could be explained by an increase in length, whereas Nyengaard (41) attributed it to an increase in branching.

Stimulation of nitric oxide (NO) production is required for hypertrophic and angiogenic responses following UNX. A rapid increase of RBF following UNX with increased vascular endothelial shear stress may stimulate intrarenal NO production (42). Chronic NO synthase inhibition with N-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester was found to blunt increases of RBF following UNX in rats (9). Knock out of endothelial NO synthase in mice eliminated renal hypertrophy following UNX (8), and NO is well known to play a critical role in angiogenesis (43). We propose that since NO is generated by increased shear stress, an increase in NO could be the consequence of the rapidly increased RBF, which would be absent with RAS inhibition and also had no effect on the observed progressive increase of RBF during the 7 days following UNX.

Chronic elevation in intrarenal NO production remains a viable hypothesis to explain the chronic increases of RBF following UNX, although it is likely that other mechanisms are also involved. Sterile inflammatory responses in the remaining kidney with activation of Nod-like receptor protein 3 has been reported to promote angiogenesis (44, 45). Stimulation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-α also stimulated by increased filtration of amino acids activates mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) complex 1 (mTORC1), which, in turn, stimulates angiogenesis (46, 47).

Metabolic Mechanisms Related to Tubular Hypertrophy

One clearly sustained stimulus for tubular hypertrophy following UNX is the increased metabolic load and stress placed upon the nephrons of the remaining kidney since total GFR returns to nearly 70% of the original total GFR within 2 days whereby single-nephron GFR must be considerably elevated. The proximal tubules reabsorb 60–65% of the filtered Na+ load and with greater filtration more is actively absorbed, requiring a sustained increase of ATP to fuel basolateral Na+-K+-ATPase. Associated mitochondrial energy and reactive oxygen species (ROS) production could thereby play an important role in the hypertrophic response. We have studied kidney oxidative stress in SD rats following unilateral UNX by three-dimensional fluorescence cryoimaging (48). At 3 days following UNX, FAD was increased with a resulting reduction of the redox ratio (NADH/FAD), which occurs as a consequence of increased production of ROS. Elevations of renal tissue H2O2 were also found to directly activate mTORC1 (49, 50), and the anabolic signaling pathways for tubular hypertrophy can be mediated by mTORC1 (47). An increased delivery of amino acids as a consequence of increased single-nephron GFR was found to activate phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, which is known to activate the mTORC1 pathway (47). Current evidence, therefore, indicates that increased workloads imposed on the remaining proximal tubules following UNX activate ROS/mTOR signaling pathways controlling the cell cycle and the hypertrophic response.

Immediate and Chronic GFR Responses to UNX

As expected, total body GFR was reduced to half of the normal in the 30-min period following UNX (Fig. 4). When determined in unanesthetized rats during day 2 following UNX, we observed that GFR was already on an average at a level that was 70% of the prenephrectomy level and remained at these values over the following 2 wk. There has been a diverse range of values reported from data obtained from rat studies ranging from 36% to 97% (51–56) of the sham GFR, but studies obtained in humans have been quite consistent with the compensatory levels that were found to be 65–75% of prenephrectomy GFR (57–59), similar to the compensation found in the present study. We attribute the variations in the rodent data to the effects of anesthesia and surgical stress under which these rats were studied. None of the reported values were determined in the unanesthetized state. The exception to this was a study by Schock-Kusch et al. (56), who developed the transcutaneous techniques applied in the present study. These investigators compared measurements of transcutaneous and plasma elimination kinetics of FITC-sinistrin in freely moving healthy rats and found by both techniques that GFR returned to nearly 75% of sham GFR values. Of relevance, all the human GFR studies were conducted in the absence of anesthesia. The effects of anesthesia and surgical manipulations with accompanying stimulation of sympathetic nervous system and other hormonal systems are recognized to have confounding effects on GFR (60). The present study was the only one to sequentially follow changes of GFR in the same rat before and after UNX, and it found that the compensation largely occurred during the first 2 days and remained at these levels of GFR for 2 wk thereafter. This is in contrast to the progressive rise of GFR reported when groups of anesthetized rats were studied at similar intervals (52).

Effects of UNX Upon Arterial Pressure and RBF Diurnal Rhythms Following UNX

The components of the RAS, such as angiotensinogen, ANG II, and AT1 receptor proteins, increase and peak at the same time as BP and urinary protein excretion during the resting phase of the diurnal cycle (61). The circadian rhythm of the intrarenal RAS may lead to renal damage and hypertension and alterations of diurnal BP variation (62). The role of RAS in the “nondipping” phenomena of BP observed in diabetes and hypertension has also been of considerable interest (63). Twenty-four-hour ambulatory BP monitoring recordings compared the effects of telmisartan in patients classified by dipper status (extreme dippers, dippers, nondippers, and reverse dippers) and found that telmisartan treatment normalized the circadian BP pattern to a dipper profile in a larger proportion of patients and reduced the early morning systolic BP surge in high-risk patients (64). The present observations are interesting in several ways. First, in a normal rat, the diurnal rhythms of BP and RBP are closely aligned. In contrast to the acute autoregulated responses of the kidney where the constancy of RBF in face of changes of BP, in the chronic state within the small increases and decreases of BP the RBF changes in parallel with BP. Second, this diurnal rhythm is not chronically altered following UNX and during the period of kidney hypertrophy. Third, it is apparent that the diurnal rhythm of BP and RBF is not modified or dependent on changes of the RAS or more specifically AT1 receptor-mediated pathways.

Limitations

Chronic sequential measurements in the unanesthetized state over prolonged periods provide the most meaningful physiological data. However, it is important to recognize that sufficient time must be allowed to recover from the effects of anesthesia and surgery and reach a normal physiological state. In the present study, it was not possible to nephrectomize the rats in the absence of anesthesia, so the immediate RBF responses were obtained under anesthesia and surgical conditions. Compared with the groups that were instrumented and studied before UNX and then after recovery, we found a disruption of the diurnal rhythms of RBF and BP during the first several days, so the data obtained in this interval must be viewed in this context.

Conclusions

We conclude that an immediate reduction of RVR following UNX is triggered by the rapid reduction of circulating renin-angiotensin. The rapid increase of RBF seen immediately after UNX is blocked by losartan and aliskiren. Progressive increases of RBF and the enhanced GFR of the remaining kidney are associated with kidney hypertrophy and unrelated to angiotensin stimulation of AT1 receptor pathways since losartan has no effect on these chronic adaptations. Tubular and glomerular hypertrophy are accompanied by angiogenic increases of glomerular and peritubular microvascularity, which account, in part, for the progressive increases of RBF observed during the first week following UNX. It appears that these responses are driven by physical factors and enhanced metabolic needs placed upon the glomeruli and tubules as single-nephron GFR increases to compensate for net loss of total body GFR. Despite many studies in this field, the molecular details of these mechanisms remain an enigma and are likely determined by multiple interacting pathways.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grants P01HL116264 and RO1HL137748.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

S.S. and A.W.C., Jr. conceived and designed research; S.S., C.Y., and T.K. performed experiments; S.S. analyzed data; S.S., C.Y., T.K., and A.W.C., Jr. interpreted results of experiments; S.S. prepared figures; S.S. drafted manuscript; C.Y., T.K., and A.W.C., Jr. edited and revised manuscript; S.S., C.Y., T.K., and A.W.C., Jr. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are grateful to the Children’s Hospital and Health System Research Institute Histology Core in the Medical College of Wisconsin for immunostaining. We thank Camille Taylor for PRA measurements.

REFERENCES

- 1.Preisig P. Renal hypertrophy and hyperplasia. In: The Kidney: Physiology and Pathophysiology (3rd ed.), edited by Seldin DW, Giebisch G.. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, 2000, vol. 1, p. 727–748. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brenner BM. Remission of renal disease: recounting the challenge, acquiring the goal. J Clin Invest 110: 1753–1758, 2002. doi: 10.1172/JCI17351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fine LG, Norman J. Cellular events in renal hypertrophy. Annu Rev Physiol 51: 19–32, 1989. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.51.030189.000315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hostetter TH. Progression of renal disease and renal hypertrophy. Annu Rev Physiol 57: 263–278, 1995. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.57.030195.001403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wesson LG. Compensatory growth and other growth responses of the kidney. Nephron 51: 149–184, 1989. doi: 10.1159/000185282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnson H, Roman JV. Compensatory renal enlargement. Am J Pathol 49: 1–13, 1966. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rojas‐Canales DM, Li JY, Makuei L, Gleadle JM. Compensatory renal hypertrophy following nephrectomy: when and how? Nephrology (Carlton) 24: 1225–1232, 2019. doi: 10.1111/nep.13578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nagasu H, Satoh M, Kidokoro K, Nishi Y, Channon KM, Sasaki T, Kashihara N. Endothelial dysfunction promotes the transition from compensatory renal hypertrophy to kidney injury after unilateral nephrectomy in mice. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 302: F1402–F1408, 2012. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00459.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sigmon DH, Gonzalez-Feldman E, Cavasin MA, Potter DL, Beierwaltes WH. Role of nitric oxide in the renal hemodynamic response to unilateral nephrectomy. J Am Soc Nephrol 15: 1413–1420, 2004. doi: 10.1097/01.ASN.0000130563.67384.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fine LG, Badie-Dezfooly B, Lowe AG, Hamzeh A, Wells J, Salehmoghaddam S. Stimulation of Na+/H+ antiport is an early event in hypertrophy of renal proximal tubular cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 82: 1736–1740, 1985. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.6.1736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Salehmoghaddam S, Bradley T, Mikhail N, Badie-Dezfooly B, Nord E, Trizna W, Kheyfets R, Fine L. Hypertrophy of basolateral Na-K pump activity in the proximal tubule of the remnant kidney. Lab Invest 53: 443–452, 1985. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pollock CA, Field MJ. Compensatory renal hypertrophy: tubular cell growth and transport studied in primary culture. Nephron 64: 615–620, 1993. doi: 10.1159/000187410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klein TW, Gittes RF. The three-kidney rat: renal isografts and renal counterbalance. J Urol 109: 19–27, 1973. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(17)60336-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Obertop H, Malt RA. Lost mass and excretion as stimuli to parabiotic compensatory renal hypertrophy. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 232: F405–F408, 1977. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1977.232.5.F405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schock-Kusch D, Sadick M, Henninger N, Kraenzlin B, Claus G, Kloetzer H-M, Weiss C, Pill J, Gretz N. Transcutaneous measurement of glomerular filtration rate using FITC-sinistrin in rats. Nephrol Dial Transplant 24: 2997–3001, 2009. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfp225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Evans LC, Ryan RP, Broadway E, Skelton MM, Kurth T, Cowley AW Jr.. Null mutation of the nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate–oxidase subunit p67phox protects the Dahl-S rat from salt-induced reductions in medullary blood flow and glomerular filtration rate. Hypertension 65: 561–568, 2015. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.04468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mackovic-Basic M, Fan R, Kurtz I. Denervation inhibits early increase in Na+-H+ exchange after uninephrectomy but does not suppress hypertrophy. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 263: F328–F334, 1992. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1992.263.2.F328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nakanishi K, Mattson DL, Gross V, Roman RJ, Cowley AW Jr.. Control of renal medullary blood flow by vasopressin V1 and V2 receptors. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 269: R193–R200, 1995. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1995.269.1.R193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peng Y, Knox FG. Comparison of systemic and direct intrarenal angiotensin II blockade on sodium excretion in rats. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 269: F40–F46, 1995. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1995.269.1.F40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wood JM, Schnell CR, Cumin F, Menard J, Webb RL. Aliskiren, a novel, orally effective renin inhibitor, lowers blood pressure in marmosets and spontaneously hypertensive rats. J Hypertens 23: 417–426, 2005. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200502000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shimada S, Hirose T, Takahashi C, Sato E, Kinugasa S, Ohsaki Y, Kisu K, Sato H, Ito S, Mori T. Pathophysiological and molecular mechanisms involved in renal congestion in a novel rat model. Sci Rep 8: 16808, 2018. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-35162-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mori T, Cowley AW Jr.. Role of pressure in angiotensin ii-induced renal injury. Hypertension 43: 752–759, 2004. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000120971.49659.6a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mori T, Polichnowski A, Glocka P, Kaldunski M, Ohsaki Y, Liang M, Cowley AW Jr.. High perfusion pressure accelerates renal injury in salt-sensitive hypertension. J Am Soc Nephrol 19: 1472–1482, 2008. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007121271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Polichnowski AJ, Cowley AW. Pressure-induced renal injury in angiotensin II versus norepinephrine-induced hypertensive rats. Hypertension 54: 1269–1277, 2009. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.139287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Polichnowski AJ, Jin C, Yang C, Cowley AW Jr.. Role of renal perfusion pressure versus angiotensin II on renal oxidative stress in angiotensin II-induced hypertensive rats. Hypertension 55: 1425–1430, 2010. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.151332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Evans LC, Petrova G, Kurth T, Yang C, Bukowy JD, Mattson DL, Cowley AW Jr.. Increased perfusion pressure drives renal T-cell infiltration in the dahl salt-sensitive rat. Hypertension 70: 543–551, 2017. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.117.09208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shimada S, Abais-Battad JM, Alsheikh AJ, Yang C, Stumpf M, Kurth T, Mattson DL, Cowley AW Jr.. Renal perfusion pressure determines infiltration of leukocytes in the kidney of rats with angiotensin II-induced hypertension. Hypertension 76: 849–858, 2020. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.120.15295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Polichnowski AJ, Griffin KA, Picken MM, Licea-Vargas H, Long J, Williamson GA, Bidani AK. Hemodynamic basis for the limited renal injury in rats with angiotensin II-induced hypertension. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 308: F252–F260, 2015. [Erratum in Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 308: F796, 2015] doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00596.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bell TD, DiBona GF, Biemiller R, Brands MW. Continuously measured renal blood flow does not increase in diabetes if nitric oxide synthesis is blocked. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 295: F1449–F1456, 2008. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00004.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cowley AW Jr, Ryan RP, Kurth T, Skelton MM, Schock-Kusch D, Gretz N. Progression of glomerular filtration rate reduction determined in conscious Dahl salt-sensitive hypertensive rats. Hypertension 62: 85–90, 2013. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.113.01194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Friedemann J, Heinrich R, Shulhevich Y, Raedle M, William-Olsson L, Pill J, Schock-Kusch D. Improved kinetic model for the transcutaneous measurement of glomerular filtration rate in experimental animals. Kidney Int 90: 1377–1385, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2016.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim S, Iwao H, Nakamura N, Ikemoto F, Yamamoto K. Fate of circulating renin in conscious rats. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Physiol 252: E136–E146, 1987. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1987.252.1.E136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lytton B, Schiff M, Bloom N. Compensatory renal growth: evidence for tissuespecific factor of renal origin. J Urol 101: 648–652, 1969. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(17)62395-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lowenstein LM, Stern A. Serum factor in renal compensatory hyperplasia. Science 142: 1479–1480, 1963. doi: 10.1126/science.142.3598.1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fenoy FJ, Scicli G, Carretero O, Roman RJ. Effect of an angiotensin II and a kinin receptor antagonist on the renal hemodynamic response to captopril. Hypertension 17: 1038–1044, 1991. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.17.6.1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Walkowska A, Červenka L, Imig JD, Falck JR, Sadowski J, Kompanowska-Jezierska E. Early renal vasodilator and hypotensive action of epoxyeicosatrienoic acid analog (EET-A) and 20-HETE receptor blocker (AAA) in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Front Physiol 12: 622882, 2021. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2021.622882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mok K-YK, Sandberg K, Sweeny JM, Zheng W, Lee S, Mulroney SE. Growth hormone regulation of glomerular AT1 angiotensin receptors in adult uninephrectomized male rats. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 285: F1085–F1091, 2003. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00383.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wight J, Bassett A, Le Carpentier J, El Nahas A. Effect of treatment with enalapril, verapamil and indomethacin on compensatory renal growth in the rat. Nephrol Dial Transplant 5: 777–780, 1990. doi: 10.1093/ndt/5.9.777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Valentin J-P, Sechi LA, Griffin CA, Humphreys MH, Schambelan M. The renin-angiotensin system and compensatory renal hypertrophy in the rat. Am J Hypertens 10: 397–402, 1997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Olivetti G, Anversa P, Rigamonti W, Vitali-Mazza L, Loud AV. Morphometry of the renal corpuscle during normal postnatal growth and compensatory hypertrophy. A light microscope study. J Cell Biol 75: 573–585, 1977. doi: 10.1083/jcb.75.2.573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nyengaard JR. Number and dimensions of rat glomerular capillaries in normal development and after nephrectomy. Kidney Int 43: 1049–1057, 1993. doi: 10.1038/ki.1993.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pittner J, Wolgast M, Casellas D, Persson AEG. Increased shear stress–released NO and decreased endothelial calcium in rat isolated perfused juxtamedullary nephrons. Kidney Int 67: 227–236, 2005. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00073.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ghimire K, Altmann HM, Straub AC, Isenberg JS. Nitric oxide: what’s new to NO? Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 312: C254–C262, 2017. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00315.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Weinheimer-Haus EM, Mirza RE, Koh TJ. Nod-like receptor protein-3 inflammasome plays an important role during early stages of wound healing. PLoS One 10: e0119106, 2015. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0119106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kielstein JT, Veldink H, Martens-Lobenhoffer J, Haller H, Perthel R, Lovric S, Lichtinghagen R, Kliem V, Bode-Böger SM. Unilateral nephrectomy causes an abrupt increase in inflammatory mediators and a simultaneous decrease in plasma ADMA: a study in living kidney donors. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 301: F1042–F1046, 2011. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00640.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Deng Y, Han X, Yao Z, Sun Y, Yu J, Cai J, Ren G, Jiang G, Han F. PPARα agonist stimulated angiogenesis by improving endothelial precursor cell function via a NLRP3 inflammasome pathway. Cell Physiol Biochem 42: 2255–2266, 2017. doi: 10.1159/000479999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen J-K, Nagai K, Chen J, Plieth D, Hino M, Xu J, Sha F, Ikizler TA, Quarles CC, Threadgill DW, Neilson EG, Harris RC. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase signaling determines kidney size. J Clin Invest 125: 2429–2444, 2015. doi: 10.1172/JCI78945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mehrvar S, Foomani FH, Shimada S, Yang C, Zheleznova NN, Mostaghimi S, Cowley AW, Ranji M. The early effects of uninephrectomy on rat kidney metabolic state using optical imaging. J Biophotonics 13: e202000089, 2020. doi: 10.1002/jbio.202000089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kumar V, Kurth T, Zheleznova NN, Yang C, Cowley AW Jr.. NOX4/H2O2/mTORC1 pathway in salt-induced hypertension and kidney injury. Hypertension 76: 133–143, 2020. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.120.15058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kumar V, Wollner C, Kurth T, Bukowy JD, Cowley AW Jr.. Inhibition of mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 attenuates salt-induced hypertension and kidney injury in dahl salt-sensitive rats. Hypertension 70: 813–821, 2017. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.117.09456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hayslett JP. Functional adaptation to reduction in renal mass. Physiol Rev 59: 137–164, 1979. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1979.59.1.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Katz A, Epstein F. Relation of glomerular filtration rate and sodium reabsorption to kidney size in compensatory renal hypertrophy. Yale J Biol Med 40: 222–230, 1967. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dicker S, Shirley D. Mechanism of compensatory renal hypertrophy. J Physiol 219: 507–523, 1971. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1971.sp009675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Larsson L, Aperia A, Wilton P. Effect of normal development on compensatory renal growth. Kidney Int 18: 29–35, 1980. doi: 10.1038/ki.1980.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Veitch MR, Thai K, Zhang Y, Desjardins JF, Kabir G, Connelly KA, Gilbert RE. Late intervention in the remnant kidney model attenuates proteinuria but not glomerular filtration rate decline. Nephrology (Carlton) 26: 270–279, 2021. doi: 10.1111/nep.13828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schock-Kusch D, Xie Q, Shulhevich Y, Hesser J, Stsepankou D, Sadick M, Koenig S, Hoecklin F, Pill J, Gretz N. Transcutaneous assessment of renal function in conscious rats with a device for measuring FITC-sinistrin disappearance curves. Kidney Int 79: 1254–1258, 2011. [Erratum in Kidney Int 80: 432, 2011] doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lenihan CR, Busque S, Derby G, Blouch K, Myers BD, Tan JC. Longitudinal study of living kidney donor glomerular dynamics after nephrectomy. J Clin Invest 125: 1311–1318, 2015. doi: 10.1172/JCI78885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gourishankar S, Courtney M, Jhangri GS, Cembrowski G, Pannu N. Serum cystatin C performs similarly to traditional markers of kidney function in the evaluation of donor kidney function prior to and following unilateral nephrectomy. Nephrol Dial Transplant 23: 3004–3009, 2008. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfn114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kwon HJ, Kim DH, Jang HR, Jung S-H, Han DH, Sung HH, Park JB, Lee JE, Huh W, Kim SJ, Kim Y-G, Kim DJ, Oh HY. Predictive factors of renal adaptation after nephrectomy in kidney donors. Transplant Proc 49: 1999–2006, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2017.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kleinjans JC, Smits JF, Kasbergen CM, Van Essen H, Struyker-Boudier HA. Evaluation of renal function during intrarenal norepinephrine infusion in conscious rats. Ren Physiol 7: 243–250, 1984. doi: 10.1159/000172944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ohashi N, Isobe S, Ishigaki S, Yasuda H. Circadian rhythm of blood pressure and the renin–angiotensin system in the kidney. Hypertens Res 40: 413–422, 2017. doi: 10.1038/hr.2016.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Isobe S, Ohashi N, Fujikura T, Tsuji T, Sakao Y, Yasuda H, Kato A, Miyajima H, Fujigaki Y. Disturbed circadian rhythm of the intrarenal renin-angiotensin system: relevant to nocturnal hypertension and renal damage. Clin Exp Nephrol 19: 231–239, 2015. doi: 10.1007/s10157-014-0973-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Larochelle P. Circadian variation in blood pressure: dipper or nondipper. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 4: 3–8, 2002. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-6175.2002.01033.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gosse P, Schumacher H. Effect of telmisartan vs. ramipril on ‘dipping’ status and blood pressure variability: pooled analysis of the PRISMA studies. Hypertens Res 37: 151–157, 2014. doi: 10.1038/hr.2013.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]