Abstract

Consumption of chloroquine (CQ) and subtherapeutic drug levels in blood are considered to be widespread in areas where malaria is endemic. A cross-sectional study was performed with 405 Nigerian children to assess factors associated with the presence of CQ in blood and to examine correlations of drug levels with malaria parasite species and densities. Infections with Plasmodium species and parasite densities were determined by microscopy and PCR assays. Whole-blood CQ concentrations were measured by high-performance liquid chromatography. Plasmodium falciparum, P. malariae, and P. ovale were observed in 80, 16, and 9% of the children, respectively, and CQ was detected in 52% of the children. CQ concentrations were >17 and <100 nmol/liter in 25% of the children, 100 to 499 nmol/liter in 14% of the children, and ≥500 nmol/liter in 13% of the children. Young age, attendance at health posts, and absence of parasitemia were factors independently associated with CQ in blood. With increasing concentrations of CQ, the prevalence of P. falciparum infection and parasite densities decreased. However, at concentrations corresponding to those usually attained during regular prophylaxis (≥500 nmol/liter), 62% of children were still harboring P. falciparum parasites. In contrast, no infection with P. malariae and only one infection with P. ovale were observed in children with CQ concentrations of ≥100 nmol/liter. These data show the high prevalence of subcurative CQ concentrations in Nigerian children and confirm the considerable degree of CQ resistance in that country. Subtherapeutic drug levels are likely to further promote CQ resistance and may impair the development and maintenance of premunition in areas where malaria is endemic.

Chloroquine (CQ) is one of the most widely consumed drugs (7). In 1988, an estimated 190 tons of CQ base were used in Africa alone (28). Self-medication, inadequate dosing, and subtherapeutic levels in blood are frequent and are believed to be predominant factors that contribute to CQ resistance in Plasmodium falciparum (25). However, data on actual CQ levels in residents of areas where malaria is endemic are scarce. The validity of history taking with respect to antimalarial drug usage is commonly low (17). Field methods for the detection of CQ in urine such as the Dill-Glazko test (13) suffer from poor sensitivity and specificity (21) and cannot quantify drug concentrations. Nevertheless, tests for detection of CQ in urine were found to be positive at hospital admission for 32% of patients in Malawi (17) and in 33% of patients in Zimbabwe (23). By applying high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), CQ was detected in the blood of up to 80% of schoolchildren in Tanzania, with the drug levels in the majority of children being too low to eliminate even CQ-sensitive parasites (9). The whole-blood CQ concentration required to suppress or eliminate P. falciparum is not well recognized. In adults, concentrations in whole blood of ≥500 nmol/liter are usually attained during prophylactic intake of 310 mg of chloroquine base/week (20). This concentration, however, may not be sufficient to protect individuals from infection with resistant parasites. In Nigeria, the efficacy of CQ has continuously declined in recent years, such that the cure rate at day 7 of treatment is 40% (5).

The present study was performed to assess the prevalence of CQ in whole blood and whole-blood CQ concentrations among children living in the area of Ibadan in southwest Nigeria. It aimed at examining patterns of CQ usage with respect to age, rural or urban residence, and the actual state of malarial infection. In addition, associations of residual CQ levels with plasmodial species and parasite densities were looked for.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population.

The study took place between December 1996 and May 1997 in the city of Ibadan, Nigeria, and the neighboring village of Abanla. Of 695 subjects enrolled in a survey on malariological indices (15), CQ and desethylchloroquine (DCQ) levels were measured in 405 children (222 males and 183 females; ages, 0.8 to 10 years) for whom parasite densities were known. Asymptomatic children were recruited from schools and vaccination programs in Abanla (n = 219) and from schools in Ibadan (n = 56). Children presenting with fever or a history of fever were recruited from health posts in Ibadan (n = 130). There were no clinical cases of severe malaria (cerebral involvement, overt anemia) in this study. Informed consent was obtained from the parents or guardians of the children included in the study. Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethical Committee of the University of Ibadan.

Laboratory examinations.

Blood was collected into EDTA- and sodium citrate-containing tubes, and the tubes were stored at 4°C. Malaria parasites were counted microscopically per 100 high-power (×1,000) fields of Giemsa-stained thick films. In addition, infections with P. falciparum, P. malariae, and P. ovale were diagnosed by nested PCR assays (22) after extraction of DNA from blood. Parasite densities were categorized as “negative,” “submicroscopic” (positive PCR result but negative blood film), “low” (≤1 parasite/high-power field [P/F]), and “moderate” (>1 P/F) (15).

Aliquots of citrate-anticoagulated blood of 100 μl were transferred onto chromatographic paper (ET 31 Chr; Whatman International, Maidstone, United Kingdom), allowed to dry, and stored at 4°C. The concentrations of CQ and DCQ were determined by a modified HPLC method (3). Drug concentrations in duplicate samples were measured and were corrected for dilution of the blood samples with 10% sodium citrate. The lower limit of determination was 17 nmol/liter for both CQ and DCQ.

Statistical analysis.

Frequencies were compared by χ2 tests, χ2 tests for trend (χ2trend), and Fisher's exact test, as applicable. In a multivariate analysis, age, study subgroups, and parasite densities were entered into a logistic regression model to estimate adjusted odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) for the presence of CQ in blood. For non-normally distributed values, Mann-Whitney U tests and Kruskal-Wallis tests were applied.

RESULTS

Malaria parasites.

Eighty percent (324 of 405) of the children harbored P. falciparum, while P. malariae was present in 16% (63 of 405) of the children and P. ovale was present in 9% (36 of 405) of the children. A total of 62% (252 of 405) of the children were exclusively infected with P. falciparum. Infections with mixtures of the following species were observed at the indicated rates: P. falciparum plus P. malariae, 9% (36 of 405); P. falciparum plus P. ovale, 2% (9 of 405); and all three organisms, 7% (27 of 405). Among the infected children, 25% (80 of 324) had submicroscopic infections, 39% (126 of 324) exhibited low parasite densities (≤1 P/F; median, 0.4 P/F; range, 0.01 to 1 P/F), and 36% (118 of 324) had moderate parasitemias (more than 1 P/F; median, 2.95 P/F; range, 1.1 to 50 P/F). The parasite densities and infecting parasite species differed among the three subgroups of children (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Parasite densities and parasite species in the study subgroups

| Subgroup | No. of subjects | Median age (yr range)a | % Subjects with the following parasite densities (no. with the indicated density/total no.)b:

|

% Subjects infected with the following parasite species (no. positive/total no. tested)c:

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Noninfected | Submicroscopic | ≤1 P/F | >1 P/F | P. falciparum | P. malariae | P. ovale | |||

| Abanla, schoolchildren and children in vaccination program | 219 | 4.0 (1–10) | 16 (36/219) | 15 (32/219) | 33 (73/219) | 36 (78/219) | 84 (183/219) | 26 (58/219) | 15 (33/219) |

| Ibadan, schoolchildren | 56 | 6.0 (3–8) | 18 (10/56) | 25 (14/56) | 37 (21/56) | 20 (11/56) | 82 (46/56) | 4 (2/56) | 5 (3/56) |

| Ibadan, health posts | 130 | 2.0 (0.8–9) | 27 (35/130) | 26 (34/130) | 25 (32/130) | 22 (29/130) | 73 (95/130) | 2 (3/130) | 0 (0/130) |

Difference between subgroups, P < 0.001.

Difference between subgroups, χ2 = 20.9 and P = 0.002.

Difference between subgroups for P. malariae, χ2 = 43.4 and P < 0.0001; difference between subgroups for P. orale, χ2 = 23.9 and P < 0.0001.

CQ and DCQ levels.

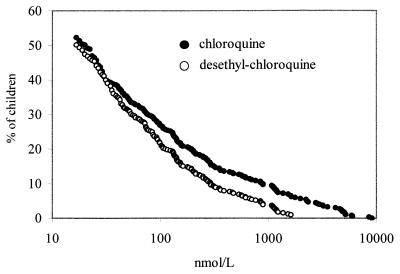

CQ and DCQ were detected in 52% (212 of 405) and 50% (203 of 405) of the children. Concentrations in whole blood ranged from 17 to 9,100 nmol/liter (median, 106 nmol/liter) for CQ and from 18 to 5,956 nmol/liter (median, 76 nmol/liter) for DCQ (Fig. 1). The mean ratio of the CQ concentration/DCQ concentration was 1.9 (range, 0.3 to 8.4; n = 199). CQ was more frequently found and concentrations were higher in children attending health posts than in schoolchildren from Ibadan or in those from the village (Table 2). CQ was especially prevalent in young children. With increasing age, both the proportion of children with CQ and the drug concentrations declined. CQ was more frequently detected in noninfected children than in infected ones (68 versus 48%; χ2 = 9.8; P = 0.002). Study subgroups, age, and parasite densities were independently associated with the presence of CQ in blood (Table 2).

FIG. 1.

Cumulative distribution of CQ and DCQ concentrations in whole blood of Nigerian children (n = 405).

TABLE 2.

Factors influencing the presence of CQ in blood and whole-blood CQ concentrationsa

| Factor | % CQ positive (no. positive/total no.)b | Adjusted OR (95% CI)c | P | Median (range) CQ concn (nmol/1)d |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | ||||

| 0–1 | 75 (55/73) | 1 | 183 (19–8,578) | |

| 2–3 | 55 (65/119) | 0.44 (0.2–0.9) | 0.02 | 136 (18–5,889) |

| 4–5 | 49 (47/96) | 0.36 (0.2–0.7) | 0.005 | 86 (17–6,011) |

| ≥6 | 38 (45/117) | 0.24 (0.1–0.5) | 0.0001 | 69 (18–9,100) |

| Study subgroup | ||||

| Abanla | 40 (88/219) | 1 | 75 (18–9,100) | |

| Ibadan, schoolchildren | 54 (30/56) | 2.12 (1.1–4.0) | 0.02 | 60 (17–3,200) |

| Ibadan, health posts | 72 (94/130) | 2.75 (1.7–4.5) | <0.0001 | 257 (18–8,578) |

| Parasite density | ||||

| None | 68 (55/81) | 1 | 152 (17–9,100) | |

| Submicroscopic | 70 (56/80) | 1.26 (0.6–2.6) | 0.52 | 136 (19–8,579) |

| ≤1 P/F | 42 (53/126) | 0.46 (0.2–0.9) | 0.01 | 59 (18–2,289) |

| >1 P/F | 41 (48/118) | 0.39 (0.2–0.7) | 0.004 | 117 (17–3,533) |

Univariate (χ2 tests) and multivariate analysis of factors associated with the presence of CQ in blood. For the presence of CQ in blood, 405 children were tested; for whole-blood CQ concentrations, 212 children were tested.

For age, χ2 = 25.2 and P < 0.0001; for study subgroup, χ2 = 33.8 and P < 0.0001; for parasite density, χ2 = 29.6 and P < 0.0001.

ORs are adjusted for age, study group, and parasite densities, as applicable.

For age, P = 0.046; for study subgroup, P < 0.0001; for parasite density, P = 0.04 (CQ concentrations were compared by Kruskal-Wallis tests).

Drug levels and parasite densities.

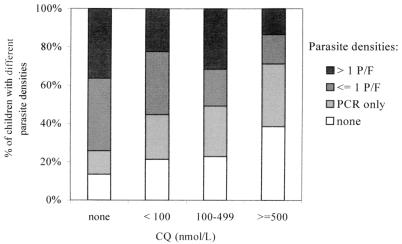

CQ concentrations were below 100 nmol/liter in 25% (103 of 405) of the children, in the range of 100 to 499 nmol/liter in 14% (57 of 405) of the children, and ≥500 nmol/liter in 13% (52 of 405) of the children. A total of 87% (167 of 193) of individuals without CQ were infected, whereas infection rates were 79% (81 of 103), 77% (44 of 57), and 62% (32 of 52) among individuals with CQ concentrations of <100, 100 to 499, and ≥500 nmol/liter, respectively (χ2trend = 15.3; P < 0.0001). Submicroscopic infections were more frequent in children with CQ (26%; 56 of 212) than among those without CQ (12%; 24 of 193 [χ2 = 11.6; P = 0.0007]). In contrast, the prevalences of low-level parasitemia (38%; 73 of 193) and moderate-level parasitemia (36%; 70 of 193) among children without CQ were reduced to 25% (53 of 212 [χ2 = 7.2; P = 0.007]) and 23% (48 of 212 [χ2 = 8.4, P = 0.004]), respectively, in individuals with the drug in their blood. Correspondingly, with increasing CQ concentrations, the proportion of submicroscopic infections increased (χ2trend = 13.6; P = 0.0002), and the proportions of low-level (χ2trend = 13.3; P = 0.0003) and moderate-level (χ2trend = 8.7, p = 0.003) parasitemias decreased (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Percentage of patients with the indicated parasite densities grouped according to whole-blood CQ concentrations (n = 405; χ2 = 43.9; P < 0.0001).

CQ and parasite species.

The highest CQ concentration in a child infected with P. falciparum was 8,578 nmol/liter. The corresponding levels were 62 nmol/liter in one child infected with P. malariae and 204 nmol/liter in another child with P. ovale parasitemia. Despite detectable CQ levels, 74% (157 of 212), 1.9% (4 of 212), and 1.4% (3 of 212) of the children harbored P. falciparum, P. malariae, and P. ovale, respectively, whereas 87% (167 of 193), 31% (59 of 193), and 17% (33 of 193) of the children without CQ in their blood harbored the species, respectively. Adjusted for age groups and study subgroups, CQ in blood was associated with the absence of (i) P. falciparum (OR, 1.9; 95% CI, 1.1 to 3.2; P = 0.03), (ii) P. malariae (OR, 16.6; 95% CI, 5.4 to 50.8; P < 0.0001), and (iii) P. ovale (OR, 9.1; 95% CI, 2.6 to 32.7; P = 0.0007). At a CQ level of ≥100 nmol/liter, only one child was infected by a malaria parasite other than P. falciparum (P. ovale [n = 1 of 109]; CQ concentration, 204 nmol/liter). Likewise, infections with mixtures of species were frequent in children without CQ in their blood, (34%; 66 of 193), were uncommon in those with concentrations of <100 nmol/liter (5%; 5 of 103), and were virtually absent from those with CQ at levels of ≥100 nmol/liter (0.9%; 1 of 109).

DISCUSSION

In this study, 52% of children had blood CQ levels above the lower limit of detection, and 80% were infected with P. falciparum. Taking into account the long terminal half-life of chloroquine of approximately 2 to 3 weeks (26) and the high rate of transmission of malaria parasites in the study area, it can be assumed that most of the P. falciparum strains in this population have been or are currently exposed to drug concentrations that are inadequate to eliminate the parasites. This constellation, namely, intense parasite transmission and the widespread presence of subcurative drug levels in blood, most likely constitutes a predisposing environment for the selection and spread of resistant P. falciparum strains (25). As resistance gradually expands and intensifies, it is also likely that the drug is taken more frequently and at higher doses. As a consequence, more intense drug pressure will then select for more resistant parasites.

The elimination of parasites is thought to be a function of both the peak drug concentration and the time span during which inhibitory levels are present (10, 19). In this cross-sectional study, a given CQ concentration could reflect recent intake or consumption of a higher dosage a longer time ago. Since the half-life of DCQ is longer than that of CQ (8), the relatively high mean ratio of the CQ concentration/DCQ concentration suggests that the majority of children had taken the drug recently before the blood collection. At concentrations that have been shown to be attained in whole blood during long-term chemoprophylaxis (≥500 nmol/liter) (20), 62% of children were found to be infected with P. falciparum in the present study. This closely matches the treatment failure rate of 60% of a recent clinical trial in Ibadan (5) and confirms the serious extent of CQ resistance in this area.

With increasing CQ concentrations, a shift from microscopically visible parasitemia toward submicroscopic infections and an absence of parasites was observed. In areas of holoendemicity, a certain percentage of actual infections can be detected only by PCR (12, 15). These submicroscopic infections may result from parasites that could not be cleared by drug or the host defense system but that remained present at a low level of multiplication from which they could recrudesce.

CQ caused a similar reduction in the proportions of low- and moderate-level parasitemias. It should be expected that the drug more easily eradicates smaller numbers than larger numbers of parasites. The effect of CQ on parasite numbers is not a linear one. Immunity, drug resistance, and fluctuations in parasite densities may be involved as well.

Independent of age, CQ was more frequently found in the blood of urban children than in the blood of children originating from the village, consistent with easier access to antimalarial agents in urban areas (18). The large number of blood specimens positive for CQ and the high drug levels in blood among children attending health posts reflect the common patterns of treatment at home and self-medication. This high rate of presumptive treatment of fever with CQ prior to the parasitological diagnosis of malaria, in addition to the effect of presumptive treatment in selecting for resistant parasite strains, can be a reason for additional CQ toxicity in such settings. Also, CQ consumption may partly explain the differences in parasitological indices between the three subgroups of children. For example, the lowest rate of use of CQ as well as the highest rate of infection, the highest parasite densities, and the highest prevalence of mixed species infections with mixtures of species, was observed among children from the rural village.

In comparison to data for Tanzanian schoolchildren assessed in 1988 (9), CQ levels in our study group were essentially higher. In Tanzania, only 9 and 2% of children had concentrations in whole blood of >100 and >500 nmol/liter, respectively, whereas 27 and 13% of the children in the present study had such concentrations, respectively. This could result from geographical differences in the rates of CQ intake, but it may also indicate the progression of CQ resistance in Africa and, subsequently, increasing rates of drug use during the last decade.

Age was a major determinant of blood CQ levels, as the highest prevalences and concentrations were seen among the youngest children. This age distribution of parasite prevalence and CQ concentration corresponds to the higher incidence and severity of malaria in that age group (11). It has been shown that, at equal dosages per body weight, plasma CQ concentrations are lower in young children than in older children and adults (14). Higher concentrations of CQ in young children could indicate the intake of fixed doses of the drug, e.g., one tablet in case of a fever, irrespective of age or weight. Recently, we have shown that the prevalence of P. falciparum, P. malariae, and P. ovale increases with age in this particular population, with the last two species being rare in children younger than 5 years of age (15). The common use of CQ, especially by young children, is likely to be responsible for this finding. Likewise, P. malariae and P. ovale infections, and thus infections with two and three species, were almost absent from children whose blood contained CQ at ≥100 nmol/liter. It has been suggested that infections with parasite strains other than P. falciparum could act as natural vaccines, preventing severe manifestations of P. falciparum infections (27). If that finding holds true, presumptive CQ treatment or prophylaxis might increase the risk for subsequent severe P. falciparum malaria.

A couple of other observations argue against the nonjudicious use of CQ. In infants, an increased rate of clinical malaria has been observed after the discontinuation of CQ chemoprophylaxis, indicating an impaired development or maintenance of immune protection during the period of chemoprophylaxis (16). Furthermore, asymptomatic, polyclonal P. falciparum infections appear to protect individuals against clinical disease from newly acquired infections (6). Correspondingly, mono- or oligoclonal P. falciparum infections may increase the risk of succeeding clinical malaria (1). Recent data indicate that the multiplicity of P. falciparum infections decreases in the presence of subcurative CQ levels (2). Long-lasting or recurrent CQ levels in blood could therefore be disadvantageous because of the elimination of persisting polyclonal infections that might be necessary to maintain protective immunity in regions where malaria is endemic.

The absence of severe malaria in the group of children with a high prevalence of residual CQ levels examined in the present study is seemingly in contrast to the hypothesis presented above. However, in a cross-sectional study, only a few clinical episodes and even fewer cases of severe malaria can be expected. This is particularly true for the children recruited at schools and vaccination programs. This study was not designed to provide information on the incidence of clinical malaria once CQ levels would have declined. Longitudinal studies may help to understand the complex interactions between the multiplicity of P. falciparum infections, immunity, and antimalarial drug use in residents of regions where malaria is endemic.

Due to the expansion of CQ resistance, the rate of mortality from malaria is increasing in Africa (4, 24). The widespread use of the drug, the large proportion of individuals with nonparasiticidal drug levels in their blood, and the almost uninhibited transmission are prerequisites for the further emergence of CQ resistance. The efficacy of CQ can now be envisaged to decline even more. So far, a drug as affordable and safe as CQ is not available. Consequently, to contain its efficacy in those areas that are not yet affected by CQ resistance, a specific diagnosis of malaria should precede specific treatment.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by the Volkswagen Foundation and by a grant from the Sonnenfeld Foundation to F.P.M.

We thank Lars Rombo for constructive comments on the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.al-Yaman F, Genton B, Reeder J C, Anders R F, Smith T, Alpers M P. Reduced risk of clinical malaria in children infected with multiple clones of Plasmodium falciparum in a highly endemic area: a prospective community study. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1997;91:602–605. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(97)90046-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beck H P, Felger I, Vounatsou P, Tanner M, Alonso P, Menendez C. Effect of iron supplementation and malaria prophylaxis in infants on Plasmodium falciparum genotypes and multiplicity of infection. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1999;93(Suppl. I):41–45. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(99)90326-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bergqvist Y, Frisk-Holmberg M. Sensitive method for the determination of chloroquine and its metabolite desethylchloroquine in human plasma and urine by high performance liquid chromatography. J Chromatogr. 1980;221:119–227. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(00)81013-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carme B, Yombi B, Bouquerty J C, Plassard H, Nzingnula S, Senga J, Akani I. Child morbidity and mortality due to cerebral malaria in Brazzaville, Congo. A retrospective and prospective hospital-based study. Trop Med Parasitol. 1992;43:173–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Falade C O, Salako L A, Sowunmi A, Oduola A M, Larcier P. Comparative efficacy of halofantrine, chloroquine and sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine for treatment of acute uncomplicated falciparum malaria in Nigerian children. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1997;91:58–62. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(97)90397-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Färnert A, Rooth I, Svensson Å, Snounou G, Bjorkman A. Complexity of Plasmodium falciparum infections is consistent over time and protects against clinical disease in Tanzanian children. J Infect Dis. 1999;179:989–995. doi: 10.1086/314652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Foster S. Economic prospects for a new antimalarial drug. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1994;88(Suppl.):55–56. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(94)90476-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gustafsson L L, Lindstrom B, Grahnen A, Alvan G. Chloroquine excretion following malaria prophylaxis. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1987;24:221–224. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1987.tb03165.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hellgren U, Ericsson Ö, Kihamia C M, Rombo L. Malaria parasites and chloroquine concentrations in Tanzanian schoolchildren. Trop Med Parasitol. 1994;45:293–297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hellgren U, Kihamia C M, Mahikwano L F, Björkman A, Eriksson Ö, Rombo L. Response of Plasmodium falciparum to chloroquine treatment: relation of whole blood concentrations of chloroquine and desethylchloroquine. Bull W H O. 1989;67:197–202. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Imbert P, Sartelet I, Rogier C, Ka S, Baujat G, Candito D. Severe malaria among children in a low seasonal transmission area, Dakar, Senegal: influence of age on clinical presentation. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1997;91:22–24. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(97)90380-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jarra W, Snounou G. Only viable parasites are detected by PCR following clearance of rodent malarial infections by drug treatment or immune responses. Infect Immun. 1998;66:3783–3787. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.8.3783-3787.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lelijveld J, Kortmann H. The eosin colour test of Dill and Glazko: a simple field test to detect chloroquine in urine. Bull W H O. 1979;42:477–479. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maitland K, Williams T N, Kotecka B M, Edstein M D, Rieckmann K H. Plasma chloroquine concentrations in young and older malaria patients treated with chloroquine. Acta Trop. 1997;66:155–161. doi: 10.1016/s0001-706x(97)00046-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.May J, Mockenhaupt F P, Ademowo O G, Falusi A G, Olumese P E, Bienzle U, Meyer C G. High rate of mixed malarial infections and submicroscopic parasitemia in South West Nigeria. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1999;61:339–343. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1999.61.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Menendez C, Kahigwa E, Hirt R, Vounatsou P, Aponte J J, Font F, Acosta C J, Schellenberg D M, Galindo C M, Kimario J, Urassa H, Brabin B, Smith T A, Kitua A Y, Tanner M, Alonso P L. Randomized placebo-controlled trial of iron supplementation and malaria chemoprophylaxis for prevention of severe anaemia and malaria in Tanzanian infants. Lancet. 1997;350:844–850. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)04229-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nwanyanwu O C, Redd S C, Ziba C, Luby S P, Mount D L, Franco C, Nyasulu Y, Chitsulo L. Validity of mother's history regarding antimalarial drug use in Malawian children under five years old. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1996;90:66–68. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(96)90482-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Plowe C V, Djimde A, Wellems T E, Diop S, Kouriba B, Doumbo O K. Community pyrimethamine-sulfadoxine use and prevalence of resistant Plasmodium falciparum genotypes in Mali: a model for deterring resistance. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1996;55:467–471. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1996.55.467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Richards W H G, Maples B K. Studies on P. falciparum in continuous cultivation. The effect of chloroquine and pyrimethamine on parasite growth and viability. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1979;73:99–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rombo L, Bergqvist Y, Hellgren U. Chloroquine and desethylchloroquine concentrations during regular long-term malaria prophylaxis. Bull W H O. 1987;65:879–883. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schwick P, Eggelte T A, Hess F, Tueumuna T T, Payne D, Nothdurft H D, von Sonnenburg F, Löscher T. Sensitive ELISA dipstick test for the detection of chloroquine in urine under field conditions. Trop Med Int Health. 1998;3:828–832. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.1998.00307.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Snounou G, Viriyakosol S, Zhu X P, Jarra W, Pinheiro L, do Rosario V E, Thaithong S, Brown K N. High sensitivity of detection of human malaria parasites by use of nested polymerase chain reaction. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1993;61:315–320. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(93)90077-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Taylor H G, Stein C M, Jongeling G. Drug use before hospital admission in Zimbabwe. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1988;34:87–90. doi: 10.1007/BF01061424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Trape J F, Pison G, Preziosi M P, Enel C, Desgrees du Lou A, Delaunay V, Samb B, Lagarde E, Molez J F, Simondon F. Impact of chloroquine resistance on malaria mortality. C R Acad Sci III. 1998;321:689–697. doi: 10.1016/s0764-4469(98)80009-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wernsdorfer W H. The development and spread of drug-resistant malaria. Parasitol Today. 1991;7:297–303. doi: 10.1016/0169-4758(91)90262-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wetsteyn J C, De Vries P J, Oosterhuis B, van Boxtel C J. The pharmacokinetics of three multiple dose regimens of chloroquine: implications for malaria chemoprophylaxis. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1995;39:696–699. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1995.tb05731.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Williams T N, Maitland K, Bennett S, Ganczakowski M, Peto T E, Newbold C I, Bowden D K, Weatherall D J, Clegg J B. High incidence of malaria in alpha-thalassaemic children. Nature. 1996;383:522–525. doi: 10.1038/383522a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.World Health Organization. Practical chemotherapy of malaria. WHO Technical Report Series No. 805. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1990. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]