Abstract

For assessing a cancer treatment, and for detecting and characterizing cancer, Diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) is commonly used. The key in DWI’s use extracranially has been due to the emergence of of high-gradient amplitude and multichannel coils, parallelimaging, and echo-planar imaging. The benefit has been fewer motion artefacts and high-quality prostate images.Recently, new techniques have been developed to improve the signal-to-noise ratio of DWI with fewer artefacts, allowing an increase in spatial resolution. For apparent diffusion coefficient quantification, non-Gaussian diffusion models have been proposed as additional tools for prostate cancer detection and evaluation of its aggressiveness. More recently, radiomics and machine learning for prostate magnetic resonance imaging have emerged as novel techniques for the non-invasive characterisation of prostate cancer. This review presents recent developments in prostate DWI and discusses its potential use in clinical practice.

Introduction

Diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) utilises the random motion of water molecules and is a powerful tool that allows the calculation of the apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) maps, enabling qualitative and quantitative assessments of prostate cancer (PCa). 1 Indeed, the latest version of the Prostate Imaging Reporting and Data System (PI-RADS) v. 2.1 positions high b-value DWI as an important sequence. 2 However, high b-value DWI has a limited signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) in association with possible eddy current distortions by large diffusion sensitizing gradients. In addition, it is often difficult to achieve high spatial resolution and good contrast in signal intensity at the same time. To overcome these limitations, novel MR techniques have been invented and are now being used for prostate DWI. For quantitative assessment, ADC measurements are generally obtained using a monoexponential fit of the signal decay data at different b-values (Gaussian diffusion model). Recently, the non-Gaussian diffusion models have been proposed toward further improvement of quantitative assessments. This review presents recent developments in prostate DWI and discusses its potential use in clinical practice.

Role of diffusion-weighted imaging in the Prostate Imaging Reporting and Data System v. 2.1

The PI-RADS v. 2.1, the latest version published in 2019 by the European Society of Urogenital Radiology and American College of Radiology, declared DWI as an important prostate multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging (mp-MRI) component. 2 The PI-RADS v. 2.1 recommends DWI acquisition with at least two barn values set in predetermined ranges, including one low b-value set at 0–100 s/mm2 (preferably 50–100 s/mm2) and one intermediate b-value set at 800–1000 s/mm2. Additionally, the PI-RADS v. 2.1 describes high b-value (≥1400 s/mm2) DWI as mandatory, as it effectively suppresses the signal of normal prostatic tissue and emphasises the contrast between cancerous and non-cancerous lesions. 3–5

Prostate lesions scoring revisions and technical specifications modifications are included in the PI-RADS v. 2.1. Transition zone (TZ) lesions scoring was changed to scores 1–3. The previous score of 2 for typical benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) nodules is now scored as T2 weighted (T 2W). 2,6,7 The previous score of 3 for atypical nodules, mostly encapsulated or homogenous without encapsulation, are now scored T 2W score 2. Furthermore, lesions with a T 2W score of 2 can be upgraded to the PI-RADS assessment category 3 if they have a DWI score of ≥4 but not with a DWI score of 3 (mild/moderate restricted diffusion). The PI-RADS v. 2.1 addresses the lack of clarity in the DWI scores 2 and 3 definitions in the peripheral zone (PZ) and TZ in v. 2. This includes differentiating between “focal” and “indistinct” hypointense lesions on ADC maps and DWI. A score of 2 should be given to linear or wedge-shaped ADC-hypointense, or DWI-hyperintense lesions, which was the score given to formerly indistinct ADC-hypointense lesions. The DWI score of 3 criteria was revised slightly: the PI-RADS v. 2.1 scored the focal ADC-hypointense and/or focal DWI hyperintense lesions as 3. One of these sequences could mark signal intensities; however, they should not be marked in both sequences. The definition of “marked” was clarified as a distinct signal change compared with any other focus in the same zone. 7 Improvements in the scoring system’s diagnostic accuracy and inter-reader agreement have been reported with these scoring updates. 7–10

Recent techniques for prostate diffusion-weighted imaging

Computed diffusion-weighted imaging

As mentioned previously, DWIs with high b-values of over 1400 s/mm2 clearly differentiate between cancerous and background tissues to detect PCa. However, limited SNR and eddy current distortions might result from high b-value DWI due to large diffusion sensitising gradients. 11 Computed DWI (also known as calculated DWI or synthesised DWI) is a mathematical computation technique used to generate DWIs of any b-value using DWI data with at least two different b-values that improve the SNR of the image. 12,13 The computed DWI signal at b = bc can be obtained using the equation Sc = Sa exp (− [bc − ba] ADC), where Sc is the signal of the computed image with a b-value of c, and Sa is the signal of the acquired image with a b-value of a. ADC is calculated using the equation ADC = ln (Sa/Sb) / (ba − bb), using two measured DWI signals, Sa and Sb, based on a monoexponential model (MEM). The advantage of this technique is that higher b-values DW images can be obtained from lower b-values images, which are potentially less prone to artefacts. Therefore, a longer echo time for accommodating the strong gradient pulses for higher b-value acquisitions is avoided. Previous studies have shown that computed high b-value (≥1400 s/mm2) DWI with better image quality translated into improved diagnostic performance for PCa diagnosis than acquired lower b-value (i.e. b = 1000) DWI. 14,15 Indeed, the PI-RADS v. 2.1 recommends the use of computed high b-value DW images as a substitute for the acquired DW images in clinical practice. 2

Techniques for high spatial resolution diffusion-weighted imaging

Echoplanar imaging (EPI) is recommended for acquiring DWI of the prostate because of its relatively high SNR and insensitivity to motion artefacts. 2 However, it can suffer from technical challenges related to B0- and B1-field inhomogeneities and eddy currents that lead to anatomic distortion and susceptibility artefacts. 11 Additionally, EPI suffers from a low in-plane spatial resolution, even at 3 T. 16 The small cross-sectional size of the prostate requires a high spatial resolution to reduce partial volume effects to detect smaller focal tumours. Accordingly, small field of view (FOV) methods have been developed to obtain high in-plane spatial resolution and exclude unwanted regions that can cause artefacts (i.e. rectum filled with gas and/or metal from pelvic/hip surgeries). There are two approaches to small-FOV imaging. The first has the advantage of parallel radiofrequency (RF) transmission technology, which was developed to minimise dielectric effects at high fields. Separate transmitter waveforms can be exploited to achieve a shaped or focused excitation of a reduced volume. 17 Inner volume excitation uses either two or three perpendicularly applied RF pulses to excite voxels along their intersection. 18,19 A second technique utilises segmentation but in the other (read-out) encoding direction and can be used on its own 20 or in combination with a navigator echo for the correction of motion-induced phase errors or other sources of phase errors. 21 Outer volume suppression bands can also be used to null signals from tissues outside the desired imaging volume. A variant of inner-volume excitation was made available commercially by major vendors such as FOCUS (GE Healthcare, Chicago, USA), ZOOMit (Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany), and iZOOM (Philips Healthcare, Best, The Netherlands). 22 These sequences employ a special 2D RF excitation pulse that is spatially selective in both slice select and phase-encoding directions. It replaces the 1D slice-selective 90°-pulse used in conventional EPI sequences. Several studies have demonstrated that small FOV DWI of the prostate improves image quality than conventional DWI. 23,24

The parallel transmission technique (pTx) includes two-channel RF transmitter systems with the ability to independently adjust the phase and amplitude of each channel. This ability allows for patient- and volume-specific B1 shimming; thus, more homogeneous excitation is achieved within the FOV along with a reduction of artefacts related to field inhomogeneity. Thus, this approach has been recently applied to small FOV DWI, and it has been reported that small FOV DWI with two-channel pTx could reduce artefacts and improve image quality for prostate DWI at 3 T. 25,26

Multishot EPI enables shorter readout times, leading to a reduction in image distortions owing to field inhomogeneity. A small FOV enables a shorter EPI echo-train length by applying a spatially selective RF pulse to excite a limited FOV in the phase-encoding direction. Alternatively, multishot EPI acquires multiple shots, where each shot requires a shorter echo train with reduced readout time in the phase-encoding direction to reduce distortion artefacts. Therefore, the combination of small FOV and multi shot EPI enables DWI with higher spatial resolution and less distortion. 27,28 In recent studies, small FOV DWI with multishot EPI has been shown to provide improved DW image quality for PCa detection than conventional EPI. 29–35

Klingebiel et al 36 evaluated the objective and subjective image qualities of three different DWI sequences, including conventional single-shot EPI (ss-EPI), parallel transmit EPI (pTx-EPI), and readout-segmented multishot EPI (rs-EPI), in prostate MRI at 3 T for same patients. In this study, rs-EPI and pTx-EPI were superior to ss-EPI in terms of contrast intensity of PCa but inferior in terms of SNR. Subjective imaging parameters were superior to those of rs-EPI. The conclusion the authors have reached is that while pTx-EPI and rs-EPI may increase detection more easily, the acquisition time will also increase.

Computed DWI can also be applied to small-FOV DWI. 37 Computed DWI may compensate for the signal reduction of small FOV DWI and could be a useful addition to routine MRI examination to improve the diagnostic capability of PCa (Figure 1). 38

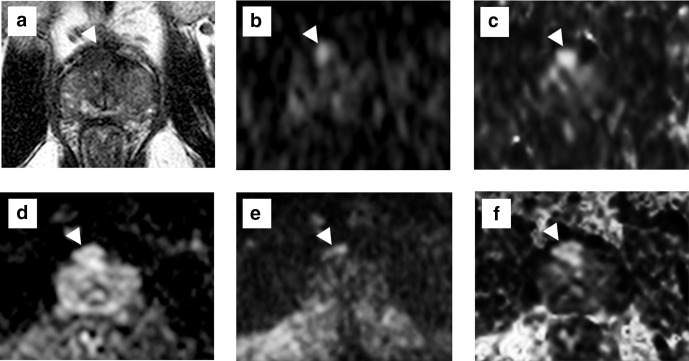

Figure 1.

Acquired and computed DWIs of a male with elevated PSA levels (6.3 ng ml−1). On T 2WI (a), a non-circumscribed and homogeneous hypo-intensity lesion is described in the dorsal TZ. The PI-RADS v. 2.1 category was 4. On the acquired b = 2000 s/mm2 DWI with a normal FOV (b, trimmed image) and on the computed b = 2000 s/mm2 DWI (generated from b = 0 and 1000 s/mm2) with a normal FOV (c, trimmed image), high-intensity lesions are depicted in the dorsal TZ. On the acquired b = 2000 s/mm2 DWI with a small FOV (d), the signal of the lesion is diminished than that with a normal FOV DWI. On the small FOV DWI with computed b = 2000 s/mm2 (generated from b = 0 and 800 s/mm2), the lesion is depicted more clearly than other images with high signal. The radical prostatectomy specimen showed a GS 7 (3 + 4) tumour in the anterior TZ, corresponding to high-intensity lesions on DWIs. DWI, diffusion-weighted imaging; FOV, field of view; PI-RADS, Prostate Imaging Reporting and Data System; PSA, prostate-specific antigen; T 2WI, T 2 weighted imaging; TZ, transition zone..

Gaussian and non-Gaussian models of diffusion-weighted imaging

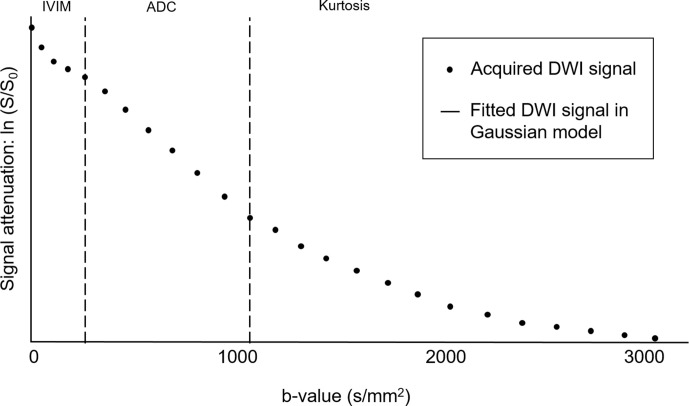

ADC quantification has been shown to be highly valuable for the diagnosis and characterisation of PCa. The ADC is usually lower in PCa than in benign prostate tissues, which is attributed to the increased cellularity of proliferating PCa and reduced water mobility in cancerous tissues. Moreover, ADCs have been reported to have a significant inverse correlation with the histopathological Gleason score (GS). 39–41 ADC measurements are generally obtained using a monoexponential fit of the signal decay data at different b-values (Gaussian diffusion model). Additionally, the assumption based on conventional DWI is not always accurate: water molecules experience different environments in tissues; hence, in vivo water diffusion is quite complicated and often presents non-Gaussian behaviour (Figure 2). In terms of signal intensity, signal attenuation is greater than expected at low b-values (≤200–300 s/mm²), whereas it is lower at larger b-values (≥1000–1500 s/mm²). 42 Accordingly, non-Gaussian diffusion models have been proposed, namely intravoxel incoherent motion (IVIM), stretched exponential model (SEM), and diffusion kurtosis imaging (DKI), to overcome the shortcomings of the Gaussian diffusion model. 43–49 However, according to the meta-analysis performed by Brancato et al 42 in 2019, the role of non-Gaussian diffusion models in the detection and characterisation of PCa aggressivenessis still not confirmed.

Figure 2.

Behaviours of the fitting DWI signals in the Gaussian model and acquired DWI signals. Under the monoexponential model based on the Gaussian model, a semilogarithmic plot of signal attenuation ln (S/So) vs b-values should be a straight line. However, the assumption of a Gaussian model is not always accurate. At low b-values (i.e. ≤200–300/mm2), signal attenuation is greater than expected owing to the IVIM effect from microscopic perfusion. At high b-values (≥1000–1500 s/mm2), signal attenuation is lower than expected owing to the Kurtosis effect. Non-Gaussian DWI models have been proposed to describe the deviation of the measured data from this expected line. ADC, apparent diffusion coefficient; DWI, diffusion-weighted imaging; IVIM, intravoxel incoherent motion.

Monoexponential model

The ADC from the MEM reflects the overall diffusion level under the assumption of the Gaussian diffusion process and is mainly attributed to cellular density. In the MEM, the ADC is generally a mean value related to diffusion. Since PCa is generally multifocal and diffuse, histogram-derived ADC parameters from monoexponential DWI have been introduced to not miss small lesions. According to Donati et al 50 , the ADC parameter which best correlates to the Gleason score is the 10th percentile ADC compared to other ADC parameters. This was determined after attaining ADC parameters using whole-lesion histograms. This suggests that for determining the difference between low-grade PCa and intermediate- or high-grade PCa with DWI, the 10th percentile ADC may be the best option.

Intravoxel incoherent motion

The IVIM model is a bicompartmental model that assumes the presence of two separate compartments: one tissue compartment and one blood compartment. In the IVIM model, f is the perfusion fraction, D is the molecular diffusion coefficient, and D* is the pseudo-diffusion coefficient. 51 Generally, D values would be lower than ADC values, as the perfusion component has been extracted. f is the microvascular volume fraction that is correlated with the fractional volume of capillary blood flow and blood vessel density. 15,52

While Pesapane et al 53 and Valerio et al 54 showed that the additional use of IVIM increased the performance of conventional T2/DWI for PCa detection, Kuru et al 55 proved that none of the IVIM parameters yielded a clear added value, which is similar to the findings reported by Feng et al. 56 In the characterisation of PCa aggressiveness, D seems to be the most performing IVIM parameter, 54–59 resulting lower in high-GS tumours than in low-GS tumours. One study 42 performed by Valerio et al 54 discovered that the value of D* was remarkably higher in high—than in low—GS PCa. In contrast, f could not distinguish the GS grades in all the reviewed studies. At the same time, another study done by Pesapane et al 53 found all three IVIM parameters were not helpful in determining the aggressive attributes of PCa.

Stretched exponential model

The SEM provides a more complete and accurate empirical description of water diffusion than MEM and IVIM. 60,61 The SEM offers parameters such as distributed diffusion coefficients (DDCs) and α values. The DDC shows the rate of signal decay with increasing b-values, and α describes the deviation of water diffusion from a single exponential decay. A strong correlation exists between DDC and ADC in tumours, 62,63 which is the composite of each ADC, weighted by the volume fraction of water molecules in each part of the continuous ADCs distribution. 64 Generally, tumours feature lower α values owing to the higher levels of intravoxel diffusion heterogeneity, as tumours have higher cellular and glandular pleomorphisms than non-cancerous tissues. Few studies have investigated the use of SEM in PCa diagnosis. 60 The study by Liu et al 60 indicated that DDC values were higher than ADC values in normal prostatic tissues but were lower than ADC values in PCa, and PCa features lower α values than both the PZ and central gland. According to Toivonen et al 65 , the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) was significant for the DDC, in the detection and characterization of PCa, resulting in a DDC and GS showed negative correlation, even though the diagnostic performance could not replace MEM.

Diffusion kurtosis imaging

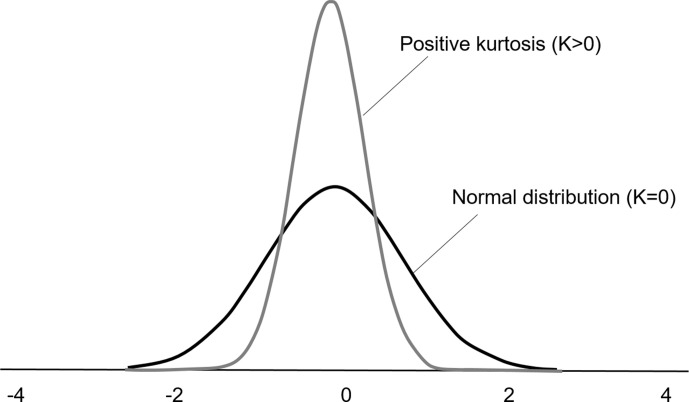

DKI uses a kurtosis-based diffusion model to characterise the multiexponential behaviour of diffusion decay. 66 In the DKI model, DK is the diffusion coefficient corrected for kurtosis, and K is the kurtosis coefficient (Figure 3). DK is referred to as a revisionary ADC, 42 leading to a similar trend of DK and ADC in PCa and non-cancerous tissues. Several previous studies revealed a significantly higher K value in PCa than in non-cancerous tissues, with an increasing trend in high GS lesions; however, there were different opinions regarding the added value offered using DKI for PCa diagnosis. Preliminary findings by Rosenkrantz et al 66 indicated a higher capability of the DKI model for distinguishing benign from malignant PCa lesions and distinguishing low-grade from high-grade PCa lesions when compared with the ADC using ROC analyses. They reported that higher K values indicate an increase in the microstructural complexity of PCa. However, later studies performed by other groups, 56,67–69 although their statistically significant test results were in accordance with the above-mentioned studies, revealed a sufficiently lower performance of DK or K than that of ADC in ROC analysis.

Figure 3.

Histogram descriptions of the kurtosis. A distribution with a higher kurtosis has a more peaked distribution than a normal distribution. By definition, the kurtosis of a normal distribution is K = 0. Diffusion in pure fluids is Gaussian; however, biological tissues are characterised by a positive diffusion kurtosis (K > 0) that occurs in the setting of non-Gaussian diffusion behaviour.

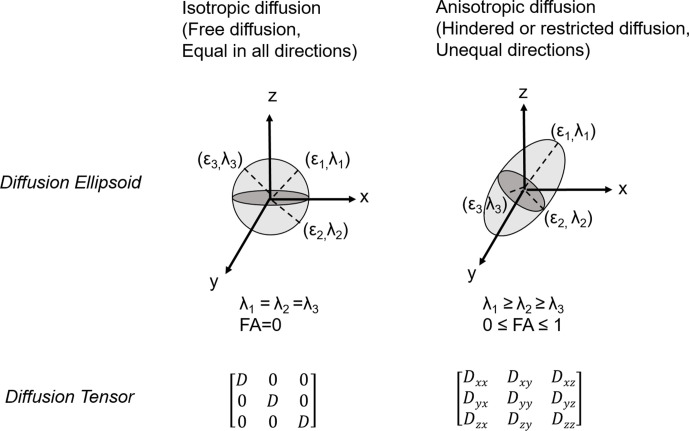

Diffusion-tensor imaging

Diffusion-tensor imaging (DTI) has recently gained attention in assessing PCa. Diffusion measurements is used in multiple (at least six) gradient directions for DT; it also enables fractional anisotropy (FA) of diffusion estimation. 70 71 Schemas of diffusion ellipsoids and tensor for isotropic and anisotropic diffusions are shown in Figure 4. The information on the organisational structure of prostate parenchyma could be provided DTI and FA quantification. FA was found to be positively correlated with GS, indicating the potential use of DTI in assessing PCa aggressiveness. 72 In a study performed by Hectors et al 70 , FA from DTI showed a negative correlation with the stromal fraction in the histopathological PCa tissue. Diffusion directionality in high-grade PCa was speculated to be induced by an increased number of cell membranes and intracellular viscosity. In contrast, water diffusion in benign PZ, mainly has glandular tissue and stroma, is isotropic. 73 The negative correlation between FA and the stromal fraction could be explained by generally less stroma found in high-grade PCa tumours. 74 Fewer significant correlations of DTI with tissue composition than monoexponential DWI was also reported.

Figure 4.

Schemas of diffusion ellipsoids and tensor for isotropic and anisotropic diffusions. The three-dimensional diffusivity is modelled as an ellipsoid whose orientation is characterised by three eigenvectors (ϵ1, ϵ2, ϵ3) and whose shape is characterised by three eigenvalues (λ1, λ2, λ3). In isotropic environments, water diffusion is the same in all different geometrical orientations, whereas in anisotropic environments, water diffusion is influenced by microstructures and nearby hindrances, which have the potential to direct water diffusion along certain defined trajectories, leading to different diffusion values in different directions. These ellipsoid models are fitted to a set of at least six non-collinear diffusion measurements by solving a set of matrix equations involving the diffusivities and requiring a procedure known as matrix diagonalisation.

Radiomics

Radiomics offers important benefits for tumour heterogeneity assessment and the potential quantitative measurements of intra- and intertumoral heterogeneities. Texture imaging is a mathematical model that allows grey-level intensity and pixels' position, arrangement evaluation, and the voxel intensities interrelation. High intratumoral heterogeneity tumours have shown an inferior prognosis, potentially reflecting intrinsically aggressive tumour biology. 75 76 Thus, in recent years, various cross-sectional imaging modalities have been used with texture analysis, and clinical applicability has been shown in detection, diagnosis, prognosis, characterisation, and response assessment of different cancers. 77 Recently, several researchers have reported the usefulness of machine learning models using texture features extracted from DWI and T 2WI for PCa detection or the evaluation of PCa aggressiveness. 78,79 Kwak et al 78 applied texture features based on T 2WI and DWI to a computer-aided diagnosis system for PCa detection. They reported that the area under the ROC curve (AUC) for distinguishing cancer from benign lesions was 0.83. Fehr et al 79 used software-based automatic classification of GS using the texture features of T 2WI and ADC. The authors reported an accuracy of 93% in the discrimination of GS (3 + 3)=6 vs GS ≥7 for the Recursive Feature Selection Support Vector Machine method using the synthetic minority oversampling technique (AUC of the same classifiers for PZ = 0.99). The same methods resulted in a 92% accuracy and an AUC of 0.99 for PZ in the discrimination of GS (3 + 4)=7 vs GS (4 + 3)=7. For the robustness of these methods, further validation studies in large cohorts are needed.

Conclusion

In summary, for the diagnosis and characterisation of PCa, many studies showed the advantages of DWI and ADC.. Advanced techniques have been proposed for improving the image quality of DWI. Parameters derived from both the Gaussian and non-Gaussian models are useful for characterising PCa from non-cancerous lesions. Machine learning models using texture features based on DWI have also been developed for PCa detection or evaluation of PCa aggressiveness. These recent techniques could be more significant tools in the diagnosis and characterisation of PCa in the future.

Footnotes

Acknowledgements: We would like to thank Editage for English language editing.

Contributor Information

Yoshiko Ueno, Email: yoshiu0121@gmail.com.

Tsutomu Tamada, Email: ttamada@med.kawasaki-m.ac.jp.

Keitaro Sofue, Email: keitarosofue@yahoo.co.jp.

Takamichi Murakami, Email: murataka@med.kobe-u.ac.jp.

REFERENCES

- 1. Kim CK, Park BK, Kim B. Diffusion-weighted MRI at 3 T for the evaluation of prostate cancer. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2010; 194: 1461–9. doi: 10.2214/AJR.09.3654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Turkbey B, Rosenkrantz AB, Haider MA, Padhani AR, Villeirs G, Macura KJ, et al. Prostate imaging reporting and data system version 2.1: 2019 update of prostate imaging reporting and data system version 2. Eur Urol 2019; 76: 340–51. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2019.02.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tamada T, Kanomata N, Sone T, Jo Y, Miyaji Y, Higashi H, et al. High B value (2,000 s/mm2) diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging in prostate cancer at 3 tesla: comparison with 1,000 s/mm2 for tumor conspicuity and discrimination of aggressiveness. PLoS One 2014; 9: e96619. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ueno Y, Kitajima K, Sugimura K, Kawakami F, Miyake H, Obara M, et al. Ultra-high b-value diffusion-weighted MRI for the detection of prostate cancer with 3-T MRI. J Magn Reson Imaging 2013; 38: 154–60. doi: 10.1002/jmri.23953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Katahira K, Takahara T, Kwee TC, Oda S, Suzuki Y, Morishita S, et al. Ultra-high-b-value diffusion-weighted MR imaging for the detection of prostate cancer: evaluation in 201 cases with histopathological correlation. Eur Radiol 2011; 21: 188–96. doi: 10.1007/s00330-010-1883-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Barrett T, Rajesh A, Rosenkrantz AB, Choyke PL, Turkbey B. PI-RADS version 2.1: one small step for prostate MRI. Clin Radiol 2019; 74: 841–52. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2019.05.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Byun J, Park KJ, Kim M-H, Kim JK. Direct comparison of PI-RADS version 2 and 2.1 in transition zone lesions for detection of prostate cancer: preliminary experience. J Magn Reson Imaging 2020; 52: 577–86. doi: 10.1002/jmri.27080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tamada T, Kido A, Takeuchi M, Yamamoto A, Miyaji Y, Kanomata N, et al. Comparison of PI-RADS version 2 and PI-RADS version 2.1 for the detection of transition zone prostate cancer. Eur J Radiol 2019; 121: 108704. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2019.108704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bhayana R, O'Shea A, Anderson MA, Bradley WR, Gottumukkala RV, Mojtahed A, et al. PI-RADS versions 2 and 2.1: interobserver agreement and diagnostic performance in peripheral and transition zone lesions among six radiologists. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2021; 217: 141–51. doi: 10.2214/AJR.20.24199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Urase Y, Ueno Y, Tamada T, Sofue K, Takahashi S, Hinata N, et al. Comparison of prostate imaging reporting and data system v2.1 and 2 in transition and peripheral zones: evaluation of interreader agreement and diagnostic performance in detecting clinically significant prostate cancer. Br J Radiol 2021;: 20201434. doi: 10.1259/bjr.20201434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Koh D-M, Blackledge M, Padhani AR, Takahara T, Kwee TC, Leach MO, et al. Whole-body diffusion-weighted MRI: tips, tricks, and pitfalls. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2012; 199: 252–62. doi: 10.2214/AJR.11.7866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Blackledge MD, Leach MO, Collins DJ, Koh D-M. Computed diffusion-weighted MR imaging may improve tumor detection. Radiology 2011; 261: 573–58. doi: 10.1148/radiol.11101919 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Maas MC, Fütterer JJ, Scheenen TWJ. Quantitative evaluation of computed high B value diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging of the prostate. Invest Radiol 2013; 48: 779–86. doi: 10.1097/RLI.0b013e31829705bb [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rosenkrantz AB, Chandarana H, Hindman N, Deng F-M, Babb JS, Taneja SS, et al. Computed diffusion-weighted imaging of the prostate at 3 T: impact on image quality and tumour detection. Eur Radiol 2013; 23: 3170–7. doi: 10.1007/s00330-013-2917-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ueno Y, Takahashi S, Kitajima K, Kimura T, Aoki I, Kawakami F, et al. Computed diffusion-weighted imaging using 3-T magnetic resonance imaging for prostate cancer diagnosis. Eur Radiol 2013; 23: 3509–16. doi: 10.1007/s00330-013-2958-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Farzaneh F, Riederer SJ, Pelc NJ. Analysis of T2 limitations and off-resonance effects on spatial resolution and artifacts in echo-planar imaging. Magn Reson Med 1990; 14: 123–39. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910140112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rieseberg S, Frahm J, Finsterbusch J. Two-Dimensional spatially-selective rf excitation pulses in echo-planar imaging. Magn Reson Med 2002; 47: 1186–93. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ma C, Xu D, King KF, Liang Z-P. Reduced field-of-view excitation using second-order gradients and spatial-spectral radiofrequency pulses. Magn Reson Med 2013; 69: 503–8. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Saritas EU, Cunningham CH, Lee JH, Han ET, Nishimura DG. Dwi of the spinal cord with reduced FOV single-shot EPI. Magn Reson Med 2008; 60: 468–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Yeom KW, Holdsworth SJ, Van AT, et al. Comparison of readout-segmented echo-planar imaging (EPI) and single-shot EPI in clinical application of diffusion-weighted imaging of the pediatric brain. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2013; 200: 437–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Porter DA, Heidemann RM. High resolution diffusion-weighted imaging using readout-segmented echo-planar imaging, parallel imaging and a two-dimensional navigator-based reacquisition. Magn Reson Med 2009; 62: 468–75. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Liney GP, Holloway L, Al Harthi TM, Sidhom M, Moses D, Juresic E, et al. Quantitative evaluation of diffusion-weighted imaging techniques for the purposes of radiotherapy planning in the prostate. Br J Radiol 2015; 88: 20150034. doi: 10.1259/bjr.20150034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Warndahl BA, Borisch EA, Kawashima A, Riederer SJ, Froemming AT. Conventional vs. reduced field of view diffusion weighted imaging of the prostate: comparison of image quality, correlation with histology, and inter-reader agreement. Magn Reson Imaging 2018; 47: 67–76. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2017.10.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Feng Z, Min X, Sah VK, Li L, Cai J, Deng M, et al. Comparison of field-of-view (FOV) optimized and constrained undistorted single shot (focus) with conventional DWI for the evaluation of prostate cancer. Clin Imaging 2015; 39: 851–5. doi: 10.1016/j.clinimag.2015.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Thierfelder KM, Scherr MK, Notohamiprodjo M, et al. Diffusion-Weighted MRI of the prostate: advantages of Zoomed EPI with parallel-transmit-accelerated 2D-selective excitation imaging. Eur Radiol 2014; 24: 3233–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rosenkrantz AB, Chandarana H, Pfeuffer J, et al. Zoomed echo-planar imaging using parallel transmission: impact on image quality of diffusion-weighted imaging of the prostate at 3T. Abdom Imaging 2015; 40: 120–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Saritas EU, Cunningham CH, Lee JH, Han ET, Nishimura DG. Dwi of the spinal cord with reduced FOV single-shot EPI. Magn Reson Med 2008; 60: 468–73. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chen N-K, Guidon A, Chang H-C, Song AW, Nan-kuei C, Arnaud G, Hing-Chiu C. A robust multi-shot scan strategy for high-resolution diffusion weighted MRI enabled by multiplexed sensitivity-encoding (MUSE. Neuroimage 2013; 72: 41–7. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.01.038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Korn N, Kurhanewicz J, Banerjee S, Starobinets O, Saritas E, Noworolski S. Reduced-FOV excitation decreases susceptibility artifact in diffusion-weighted MRI with endorectal coil for prostate cancer detection. Magn Reson Imaging 2015; 33: 56–62. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2014.08.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Fedorov A, Tuncali K, Panych LP, Fairhurst J, Hassanzadeh E, Seethamraju RT, et al. Segmented diffusion-weighted imaging of the prostate: application to transperineal in-bore 3T Mr image-guided targeted biopsy. Magn Reson Imaging 2016; 34: 1146–54. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2016.05.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Thierfelder KM, Scherr MK, Notohamiprodjo M, Weiß J, Dietrich O, Mueller-Lisse UG, et al. Diffusion weighted MRI of the prostate: advantages of zoomed EPI with parallel-transmit-accelerated 2D-selective excitation imaging. Eur Radiol 2014; 24: 3233–41. doi: 10.1007/s00330-014-3347-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Barth BK, Cornelius A, Nanz D, Eberli D, Donati OF. Diffusion-Weighted imaging of the prostate: image quality and geometric distortion of readout-segmented versus selective-excitation accelerated acquisitions. Invest Radiol 2015; 50: 785. doi: 10.1097/RLI.0000000000000184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rosenkrantz AB, Chandarana H, Pfeuffer J, Triolo MJ, Shaikh MB, Mossa DJ, et al. Zoomed echo-planar imaging using parallel transmission: impact on image quality of diffusion-weighted imaging of the prostate at 3T. Abdom Imaging 2015; 40: 120–6. doi: 10.1007/s00261-014-0181-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Donato F, Costa DN, Yuan Q, Rofsky NM, Lenkinski RE, Pedrosa I. Geometric distortion in diffusion-weighted MR imaging of the prostate-contributing factors and strategies for improvement. Acad Radiol 2014; 21: 817–23. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2014.02.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Brendle C, Martirosian P, Schwenzer NF, Kaufmann S, Kruck S, Kramer U, et al. Diffusion-weighted imaging in the assessment of prostate cancer: comparison of zoomed imaging and conventional technique. Eur J Radiol 2016; 85: 893–900. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2016.02.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Klingebiel M, Ullrich T, Quentin M, Bonekamp D, Aissa J, Mally D, et al. Advanced diffusion weighted imaging of the prostate: comparison of readout-segmented multi-shot, parallel-transmit and single-shot echo-planar imaging. Eur J Radiol 2020; 130: 109161. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2020.109161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Cho E, Lee JH, Baek HJ, Ha JY, Ryu KH, Park SE, et al. Clinical feasibility of reduced diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging with computed diffusion-weighted imaging technique in breast cancer patients. Diagnostics 2020; 10: 538. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics10080538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ueno YR, Tamada T, Takahashi S, Tanaka U, Sofue K, Kanda T, et al. Computed diffusion-weighted imaging in prostate cancer: basics, advantages, cautions, and future prospects. Korean J Radiol 2018; 19: 832–7. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2018.19.5.832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Nagarajan R, Margolis D, Raman S, Sheng K, King C, Reiter R, et al. Correlation of Gleason scores with diffusion-weighted imaging findings of prostate cancer. Adv Urol 2012; 2012: 1–5. doi: 10.1155/2012/374805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Turkbey B, Shah VP, Pang Y, Bernardo M, Xu S, Kruecker J, et al. Is apparent diffusion coefficient associated with clinical risk scores for prostate cancers that are visible on 3-T MR images? Radiology 2011; 258: 488–95. doi: 10.1148/radiol.10100667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Salami SS, Ben-Levi E, Yaskiv O, Turkbey B, Villani R, Rastinehad AR. Risk stratification of prostate cancer utilizing apparent diffusion coefficient value and lesion volume on multiparametric MRI. J Magn Reson Imaging 2017; 45: 610–6. doi: 10.1002/jmri.25363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Brancato V, Cavaliere C, Salvatore M, Monti S. Non-Gaussian models of diffusion weighted imaging for detection and characterization of prostate cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep 2019; 9: 16837. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-53350-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Rosenkrantz AB, Padhani AR, Chenevert TL, Koh D-M, De Keyzer F, Taouli B, et al. Body diffusion kurtosis imaging: basic principles, applications, and considerations for clinical practice. J Magn Reson Imaging 2015; 42: 1190–202. doi: 10.1002/jmri.24985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Toivonen J, Merisaari H, Pesola M, Taimen P, Boström PJ, Pahikkala T, et al. Mathematical models for diffusion-weighted imaging of prostate cancer using b values up to 2000 s/mm(2) : correlation with Gleason score and repeatability of region of interest analysis. Magn Reson Med 2015; 74: 1116–24. doi: 10.1002/mrm.25482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Rosenkrantz AB, Prabhu V, Sigmund EE, Babb JS, Deng F-M, Taneja SS. Utility of diffusional kurtosis imaging as a marker of adverse pathologic outcomes among prostate cancer active surveillance candidates undergoing radical prostatectomy. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2013; 201: 840–6. doi: 10.2214/AJR.12.10397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Jambor I, Merisaari H, Taimen P, Boström P, Minn H, Pesola M, et al. Evaluation of different mathematical models for diffusion-weighted imaging of normal prostate and prostate cancer using high b-values: a repeatability study. Magn Reson Med 2015; 73: 1988–98. doi: 10.1002/mrm.25323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Suo S, Chen X, Wu L, Zhang X, Yao Q, Fan Y, et al. Non-Gaussian water diffusion kurtosis imaging of prostate cancer. Magn Reson Imaging 2014; 32: 421–7. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2014.01.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Mazaheri Y, Afaq A, Rowe DB, Lu Y, Shukla-Dave A, Grover J. Diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging of the prostate: improved robustness with stretched exponential modeling. J Comput Assist Tomogr 2012; 36: 695–703. doi: 10.1097/RCT.0b013e31826bdbbd [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Liu X, Zhou L, Peng W, Wang H, Zhang Y. Comparison of stretched-Exponential and monoexponential model diffusion-weighted imaging in prostate cancer and normal tissues. J Magn Reson Imaging 2015; 42: 1078–85. doi: 10.1002/jmri.24872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Donati OF, Mazaheri Y, Afaq A, Vargas HA, Zheng J, Moskowitz CS, et al. Prostate cancer aggressiveness: assessment with whole-lesion histogram analysis of the apparent diffusion coefficient. Radiology 2014; 271: 143–52. doi: 10.1148/radiol.13130973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Le Bihan D, Breton E, Lallemand D, Grenier P, Cabanis E, Laval-Jeantet M. Mr imaging of intravoxel incoherent motions: application to diffusion and perfusion in neurologic disorders. Radiology 1986; 161: 401–7. doi: 10.1148/radiology.161.2.3763909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. He N, Li Z, Li X, Dai W, Peng C, Wu Y, et al. Intravoxel incoherent motion diffusion-weighted imaging used to detect prostate cancer and stratify tumor grade: a meta-analysis. Front Oncol 2020; 10: 1623. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2020.01623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Pesapane F, Patella F, Fumarola EM, Panella S, Ierardi AM, Pompili GG, et al. Intravoxel incoherent motion (IVIM) diffusion weighted imaging (DWI) in the periferic prostate cancer detection and stratification. Med Oncol 2017; 34: 35. doi: 10.1007/s12032-017-0892-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Valerio M, Zini C, Fierro D, Giura F, Colarieti A, Giuliani A, et al. 3T multiparametric MRI of the prostate: does intravoxel incoherent motion diffusion imaging have a role in the detection and stratification of prostate cancer in the peripheral zone? Eur J Radiol 2016; 85: 790–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2016.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Kuru TH, Roethke MC, Stieltjes B, Maier-Hein K, Schlemmer H-P, Hadaschik BA, et al. Intravoxel incoherent motion (IVIM) diffusion imaging in prostate cancer - what does it add? J Comput Assist Tomogr 2014; 38: 558–64. doi: 10.1097/RCT.0000000000000088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Feng Z, Min X, Margolis DJA, Duan C, Chen Y, Sah VK, et al. Evaluation of different mathematical models and different b-value ranges of diffusion-weighted imaging in peripheral zone prostate cancer detection using b-value up to 4500 s/mm2 . PLoS One 2017; 12: e0172127. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0172127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Yang DM, Kim HC, Kim SW, Jahng G-H, Won KY, Lim SJ, et al. Prostate cancer: correlation of intravoxel incoherent motion MR parameters with Gleason score. Clin Imaging 2016; 40: 445–50. doi: 10.1016/j.clinimag.2016.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Barbieri S, Brönnimann M, Boxler S, Vermathen P, Thoeny HC. Differentiation of prostate cancer lesions with high and with low Gleason score by diffusion-weighted MRI. Eur Radiol 2017; 27: 1547–55. doi: 10.1007/s00330-016-4449-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Bao J, Wang X, Hu C, Hou J, Dong F, Guo L. Differentiation of prostate cancer lesions in the transition zone by diffusion-weighted MRI. Eur J Radiol Open 2017; 4: 123–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ejro.2017.08.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Liu X, Zhou L, Peng W, Wang H, Zhang Y. Comparison of stretched-Exponential and monoexponential model diffusion-weighted imaging in prostate cancer and normal tissues. J Magn Reson Imaging 2015; 42: 1078–85. doi: 10.1002/jmri.24872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Li C, Chen M, Wan B, Yu J, Liu M, Zhang W, et al. A comparative study of Gaussian and non-Gaussian diffusion models for differential diagnosis of prostate cancer with in-bore transrectal MR-guided biopsy as a pathological reference. Acta Radiol 2018; 59: 1395–402. doi: 10.1177/0284185118760961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Bai Y, Lin Y, Tian J, Shi D, Cheng J, Haacke EM, et al. Grading of gliomas by using monoexponential, biexponential, and stretched exponential diffusion-weighted MR imaging and diffusion kurtosis MR imaging. Radiology 2016; 278: 496–504. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2015142173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Kwee TC, Galbán CJ, Tsien C, Junck L, Sundgren PC, Ivancevic MK, et al. Comparison of apparent diffusion coefficients and distributed diffusion coefficients in high-grade gliomas. J Magn Reson Imaging 2010; 31: 531–7. doi: 10.1002/jmri.22070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Bennett KM, Hyde JS, Schmainda KM. Water diffusion heterogeneity index in the human brain is insensitive to the orientation of applied magnetic field gradients. Magn Reson Med 2006; 56: 235–9. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Toivonen J, Merisaari H, Pesola M, Taimen P, Boström PJ, Pahikkala T, et al. Mathematical models for diffusion-weighted imaging of prostate cancer using b values up to 2000 s/mm(2) : correlation with Gleason score and repeatability of region of interest analysis. Magn Reson Med 2015; 74: 1116–24. doi: 10.1002/mrm.25482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Rosenkrantz AB, Padhani AR, Chenevert TL, Koh D-M, De Keyzer F, Taouli B, et al. Body diffusion kurtosis imaging: basic principles, applications, and considerations for clinical practice. J Magn Reson Imaging 2015; 42: 1190–202. doi: 10.1002/jmri.24985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Langkilde F, Kobus T, Fedorov A, Dunne R, Tempany C, Mulkern RV, et al. Evaluation of fitting models for prostate tissue characterization using extended-range B-factor diffusion-weighted imaging. Magn Reson Med 2018; 79: 2346–58. doi: 10.1002/mrm.26831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Roethke MC, Kuder TA, Kuru TH, Fenchel M, Hadaschik BA, Laun FB, et al. Evaluation of diffusion Kurtosis imaging versus standard diffusion imaging for detection and grading of peripheral zone prostate cancer. Invest Radiol 2015; 50: 483–9. doi: 10.1097/RLI.0000000000000155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Tamada T, Prabhu V, Li J, Babb JS, Taneja SS, Rosenkrantz AB. Prostate cancer: diffusion-weighted MR imaging for detection and assessment of aggressiveness-comparison between conventional and Kurtosis models. Radiology 2017; 284: 100–8. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2017162321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Hectors SJ, Semaan S, Song C, Lewis S, Haines GK, Tewari A, et al. Advanced diffusion-weighted imaging modeling for prostate cancer characterization: correlation with quantitative histopathologic tumor tissue Composition-A hypothesis-generating study. Radiology 2018; 286: 918–28. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2017170904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Shenhar C, Degani H, Ber Y, Baniel J, Tamir S, Benjaminov O, et al. Diffusion is directional: innovative diffusion tensor imaging to improve prostate cancer detection. Diagnostics 2021; 11: 563. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics11030563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Li L, Margolis DJA, Deng M, Cai J, Yuan L, Feng Z, et al. Correlation of Gleason scores with magnetic resonance diffusion tensor imaging in peripheral zone prostate cancer. J Magn Reson Imaging 2015; 42: 460–7. doi: 10.1002/jmri.24813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Kim CK, Jang SM, Park BK. Diffusion tensor imaging of normal prostate at 3 T: effect of number of diffusion-encoding directions on quantitation and image quality. Br J Radiol 2012; 85: e279–83. doi: 10.1259/bjr/21316959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Chatterjee A, Watson G, Myint E, Sved P, McEntee M, Bourne R. Changes in epithelium, stroma, and lumen space correlate more strongly with Gleason pattern and are stronger predictors of prostate ADC changes than cellularity metrics. Radiology 2015; 277: 751–62. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2015142414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Ueno Y, Forghani B, Forghani R, Dohan A, Zeng XZ, Chamming's F, et al. Endometrial carcinoma: MR imaging-based texture model for preoperative risk stratification-A preliminary analysis. Radiology 2017; 284: 748–57. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2017161950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Davnall F, Yip CSP, Ljungqvist G, Selmi M, Ng F, Sanghera B, et al. Assessment of tumor heterogeneity: an emerging imaging tool for clinical practice? Insights Imaging 2012; 3: 573–89. doi: 10.1007/s13244-012-0196-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Stoyanova R, Takhar M, Tschudi Y, Ford JC, Solórzano G, Erho N, et al. Prostate cancer radiomics and the promise of radiogenomics. Transl Cancer Res 2016; 5: 432–47. doi: 10.21037/tcr.2016.06.20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Kwak JT, Xu S, Wood BJ, Turkbey B, Choyke PL, Pinto PA, et al. Automated prostate cancer detection using T2-weighted and high-b-value diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging. Med Phys 2015; 42: 2368–78. doi: 10.1118/1.4918318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Fehr D, Veeraraghavan H, Wibmer A, Gondo T, Matsumoto K, Vargas HA, et al. Automatic classification of prostate cancer Gleason scores from multiparametric magnetic resonance images. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2015; 112: E6265–73. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1505935112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]