Abstract

The use of polymer additives that stabilize fluidic amorphous calcium phosphate (ACP) is key to obtaining intrafibrillar mineralization of collagen in vitro. On the other hand, this biomimetic approach inhibits the nucleation of mineral crystals in unconfined extrafibrillar spaces, that is, extrafibrillar mineralization. The extrafibrillar mineral content is a significant feature to replicate from hard connective tissues such as bone and dentin as it contributes to the final microarchitecture and mechanical stiffness of the biomineral composite. Herein, we report a straightforward route to produce densely mineralized collagenous composites via a surface-directed process devoid of the aid of polymer additives. Simulated body fluid (1× SBF) is employed as a biomimetic crystalizing medium, following a preloading procedure on the collagen surface to quickly generate the amorphous precursor species required to initiate matrix mineralization. This approach consistently leads to the formation of extrafibrillar bioactive minerals in bulk collagen scaffolds, which may offer an advantage in the production of osteoconductive collagen–apatite materials for tissue engineering and repair purposes.

Keywords: type-I collagen, mineralization, apatite, amorphous precursor, nanofibrous scaffolds

1. INTRODUCTION

Fibrillar collagen, particularly type I, is the primary organic constituent of specialized extracellular matrices such as bone and dentin. In such tissues, varied fibrillar arrangements of collagen combine with other matrix macromolecules to serve as a template for the mineralization of hydroxyapatite (HA), resulting in highly organized hybrid structures with outstanding mechanical properties.1,2

Due to the absolute relevance of the skeleton and dentition for a living organism, scientists have been long interested in unraveling and mimicking the process of biomineralization for tissue engineering and reparative medicine purposes.3,4 Reproducing this function of living organisms in the “dish” remains a continued challenge though, for it involves the interplay of multiple components with potentially relevant roles in the consolidation of the biomineral, including matrix vesicles,5 prenucleation clusters,6 and non-collagenous matrix proteins (NCPs).7

Collagen alone, as a template, is most likely not sufficient to initiate the nucleation of apatite to obtain crystals with peculiar size (nanoscopic), shape (plate-like), and alignment.8,9 For instance, when collagen scaffolds are exposed to solutions supersaturated toward calcium phosphate (CaP), the ions tend to precipitate randomly in the vicinity of the fibril web, leading to large extrafibrillar spherulites in the best scenario.10–12

The perspectives for an effective biomimetic model system changed after Olszta et al.13 proposed the mineralization of collagen via a polymer-induced liquid precursor (PILP). Polymer additives such as polyaspartate (pAsp) are used as nucleation inhibitors to stabilize a fluidic amorphous calcium phosphate phase in solution. The PILP phase infiltrates the compartments of a collagen fibril (e.g., gap regions), where it transforms into oriented apatite crystals, achieving intrafibrillar mineralization.14

While the PILP mechanism has proved a remarkable in vitro system for mimicking the intrafibrillar minerals of bone, it is not ideal for achieving extrafibrillar mineralization, i.e., the deposition of apatite nanocrystals between the collagen fibrils. Under optimal condition, the PILP phase tends to solidify strictly inside the collagen fibril, whereas preserving its fluidic character at the solution–fibril interface.15

Although intrafibrillar minerals amount to a distinctive bone feature, the relevance of the extrafibrillar inorganic content cannot be neglected. In vertebrae hard tissues, the mineral phase is also found on the collagenous matrix's surface (and filling in the spaces between the fibrils) to consolidate robust composites.2,16 Fundamentally, the extrafibrillar apatite contributes to both the microarchitecture and the high strength and toughness of native extracellular matrices.17–19 In dentin, the mineral phase takes up to ~ 50% by volume of the tissue (against ~ 30% of the collagenous matrix),20 implying that a considerable amount of minerals must reside outside the fibrils. In bones, extrafibrillar minerals are also present, even though there is some dispute as to whether they are predominantly outside or inside the collagen fibrils.21,22

Alternative mineralization approaches could offer advantages over reactions leading to strict intrafibrillar minerals, particularly when thinking about the production of densely mineralized scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. For instance, simulated body fluid (SBF) as an ion source is considered an attractive solution to promote the deposition of calcium phosphates on the surface of fibrillar collagen. Lamellar scaffolds and other collagen hydrogels have been mineralized by either direct immersion in SBF or co-precipitation of collagen and apatite in the solution.23–25 Despite great efforts to create these potential bone substitutes, it is unclear how closely the resulting collagen–apatite composites replicate the structural organization of natural bone in the nanoscale.

For presenting an ion composition nearly equal to that of the human blood plasma, SBF (or its multiples, e.g., 1.5× SBF) represents probably the most famous supersaturated solution to generate “bone-like” apatite in vitro.26,27 This serum-like solution is particularly suitable for predicting the apatite-forming ability of various kinds of biomaterials.28 When it comes to collagenous scaffolds though, the apatite activity in non-concentrated (1×) SBF seems minimal. In fact, mineralization studies commonly rely on concentrated versions of SBF to facilitate the precipitation of CaP and attain some degree of collagen mineralization.29,30 The use of modified SBF versions certainly renders the reactions less biomimetic compared to the original SBF immersion technique.

The present study reports an in vitro reaction using 1× SBF (the condition most similar to serum) as a crystalizing medium in conjunction with reconstituted collagen fibrils preloaded with amorphous CaP precursors after fibrillation. We demonstrate how a mineral induction step can enhance the apatite-forming ability of type-I collagen in non-concentrated SBF. This strategy proved to be useful to fabricate densely mineralized collagenous scaffolds – as opposed to strict intrafibrillar mineralization of single-layer collagen fibrils typically induced using polymer additives.

2. EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

2.1. Materials

The main reagent used in the synthesis of collagen fibrils was a commercial solution of soluble atelocollagen at 3 mg mL−1, PureCol type-I collagen solution (≥ 99.9%, Advanced Biomatrix, catalog 5005). All salts used for buffers and ionic solutions were of analytical grade, including calcium chloride (96%, Acros Organics, catalog 349615000); magnesium chloride (≥ 98%, Sigma, catalog M8266); potassium chloride (≥ 99.0%, Sigma, catalog P9541); sodium chloride (≥ 99.0%, Fisher Chemical, catalog S271–500); sodium bicarbonate (> 95%, Fisher Scientific, catalog S233–500); potassium phosphate dibasic (≥ 98%, Sigma Aldrich, catalog P3786); sodium phosphate dibasic (≥ 99%, Sigma Aldrich, catalog 795410); sodium sulfate (≥ 99.0%, Sigma Aldrich, catalog 239313); Tris Base (≥ 99.8%, Fisher BioReagents, catalog BP152–1). Other chemicals: TraceCERT calcium standard 1000 ppm (Sigma Aldrich, catalog 39865); perfectION calcium ion strength adjuster (METTLER TOLEDO, catalog 51344761); hexamethyldisilazane (98%, ACROS Organics, catalog AC120581000), glutaraldehyde solution 25% (Fisher BioReagents, catalog BP25481).

2.2. Synthesis of collagen fibril matrix

Type-I collagen fibrils were reconstituted in vitro from solubilized bovine collagen based on a reproducible protocol31 with modifications as follows. In a microfuge tube, three ingredients were combined and homogenized: 150 μL of ultrapure water, 500 μL of Na2HPO4 at 200 mmol L−1 (pH adjusted to 7 with HCl), and 250 μL of KCl at 400 mmol L−1. To the same tube, 100 μL of a commercial collagen monomer solution (3 mg mL−1 in 0.01 N HCl) were added and vortexed for a few seconds. This reaction mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 4 h under a gentle motion to enable the spontaneous assembly of banded collagen fibrils. Subsequently, the mixture was centrifuged at 9600 g for 10 min to recover the fibrils. As a result of the ultracentrifugation, a compact white sponge (a pellet) was formed at the bottom of the microfuge tube. A micropipette was utilized to dispose of the supernatant having the fibrils sponge inside the tube. Fresh ultrapure water (1 mL) was added to the tube to wash the specimen and eliminate excess salts. The tube was agitated manually by inverting it repeatedly during 15 s; then, the aqueous phase was disposed of with the aid of a micropipette, and the full washing step repeated again. To obtain a pristine collagen matrix, the fibrils sponge underwent the final steps of chemical fixation, dehydration and chemical drying, which are described in the Supporting Information, Table S1.

2.3. Mineralization protocol using SBF

SBF was selected as a biomimetic medium to assess the ability of type-I collagen to promote the formation of apatite in a serum-like environment. The 1× SBF used throughout this study was prepared according to a comprehensive protocol reported by Kokubo and Takadama28. The final solution had its pH adjusted to 7.4 at 36.5 °C and the expected ion concentrations (mmol L−1) are as follows: Cl−, 147.8; Na+, 142.0; K+, 5.0; HCO3−, 4.2; Ca2+, 2.5; Mg2+, 1.5; HPO4−2, 1.0; SO4−2, 0.5. For the mineralization experiment, fresh collagen fibrils matrices were produced as described above, except that the final steps of fixation, dehydration, and drying were intentionally skipped. Next, the collagen matrices were exposed to a sequence of ionic solutions (including SBF) aiming to promote the in-situ formation of apatite. Table 1 summarizes the proposed multistage protocol for the mineralization of fibrillar collagen using SBF as the crystallizing medium. To demonstrate the importance of the sequential steps of preloading (A–D) and apatite formation (E–F) described in Table 1, separate batches of fresh collagen matrices were subjected either to steps A–D or steps E–F (and then finished as in steps G–H). The materials obtained by conducting only specific parts of the mineralization protocol were compared to those obtained by following the protocol thoroughly.

Table 1.

Multistage protocol for mineralization of type-I collagen fibrils using simulated body fluid (SBF) as a crystallizing medium.

| Steps | Description | |

|---|---|---|

| PRELOADING | A | Soaking in 150 mM CaCl2 aqueous solution (1 mL, 5 min under agitation*) |

| B | Rinsing with ultrapure water (1 mL, 10 s under manual agitation) | |

| C | Soaking in 150 mM Na2HPO4 solution (1 mL, 5 min under agitation*) | |

| D | Rinsing with ultrapure water (1 mL, 10 s under manual agitation) | |

| APATITE FORMATION | E | Incubation in 1× SBF (1.5 mL, 1–4 d under agitation*)

|

| F | Rinsing with ultrapure water (1 mL, 10–20 s)

|

|

| FINISHING | G | Specimen dehydration: wash in graded series of ethanol–water solutions at 50%, 75%, 95% and twice 100% (1 mL, 15 min each) |

| H | Chemical drying: soak in pure HMDS† twice (~ 0.5 mL, 15 min each)

|

|

Smooth rocking motion in a rocker shaker.

HMDS, hexamethyldisilazane. Mineralized collagen fibrils did not undergo chemical fixation as part of the finishing steps because the mineral coating itself stabilizes the fibrils.

2.4. Characterization of the collagen–apatite composites

2.4.1. Scanning and transmission electron microscopy

The micromorphology of the mineralized collagen matrices was examined by field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM) on a JEOL JSM–IT500HR microscope operating in high vacuum mode. Topographic images were recorded with a secondary electron detector at an acceleration voltage of 5 kV. Prior to the FESEM analysis, the dried samples were carefully transferred to strips of conductive carbon double-sided sticky tape applied to aluminum specimen mounts. Lastly, the mounted samples were sputter-coated with a thin layer of platinum.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) micrographs were recorded on a JEOL JEM–1400Flash microscope equipped with a lanthanum hexaboride (LaB6) filament operating at 80–100 kV. Briefly, the specimens were submitted to the steps of chemical fixation with 2.5% glutaraldehyde (in 0.1 M phosphate-buffered saline) overnight at 4 °C, dehydration in graded series of ethanol, and embedding in LX112 epoxy resin. Ultra-thin sections (~ 70-nm thick) were obtained with a diamond knife in an ultramicrotome. The specimens were collected onto copper/rhodium mesh grids and lightly post-stained (with 2–3% aqueous uranyl acetate for ~2 min) prior to analysis and imaging.

2.4.2. Energy-dispersive spectroscopy

Energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) was used to evaluate semi-qualitatively the composition of the apatitic coatings on the fibrils' surface. The analysis was conducted using an Oxford Ultim Max EDS detector coupled to a JEOL JSM–IT500HR microscope operating at 15 kV. Layered Images (i.e., composite images created from both the electron and the X-ray map images) were built to reveal the distribution of chemical elements in the mineralized samples. Two different samples per group were considered in the acquisition of the map data.

2.4.3. Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy

Collagen fibrils mineralized in SBF for 0 h (control/as-synthesized fibrils), 24 h, 48 h, and 96 h were examined with respect to their chemical composition using Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy in conjunction with attenuated total reflectance (ATR). The tests were conducted in triplicates on a Thermo Scientific Nicolet iS5 spectrometer equipped with a Thermo Scientific iD5 ATR accessory. Each dry collagen sample was carefully placed on the top of the ATR's single-reflection Ge crystal, and then pressed for optimal contact using the accessory's pressure clamp (Supporting Information, Figure S1). Infrared absorbance spectra were recorded in the range of 1400–400 cm−1 at a resolution of 4 cm−1 using thirty-two accumulations.

2.5. Analysis of the mineralization medium

2.5.1. Calcium-selective electrode measurements

The decrease in the concentration of Ca2+ ions in the mineralization medium was monitored to assess the uptake of calcium by the collagen fibrils during the mineralization experiment. A fresh batch of collagen fibrils matrices was prepared for this experiment. All specimens underwent alternate soaking (steps A–D in Table 1) followed by cycles of incubation in SBF (1.5 mL) for a total of 96 h. At 24-h intervals, an aliquot of the medium was withdrawn to determine the calcium activity by using an ion-selective electrode (Mettler Toledo perfectION comb Ca2+) coupled to a multi-function potentiometer (Mettler Toledo SevenMulti). The medium was then completely exchanged by fresh SBF (1.5 mL) to enable another 24-h mineralization cycle (supporting both an optimal pH and the availability of critical ionic species throughout the experiment). Prior to the measurements, each sample was diluted 4× in ultrapure water to a final volume of 2 mL, and then mixed with a calcium ionic strength adjuster in the ratio of 50:1 by volume. The diluted samples were allowed to equilibrate through the electrode's membrane for at least 10 min before reading the conductivity. The values, registered in mV, were converted to concentration (ppm) by means of a calibration curve, which was generated using five standard solutions containing Ca2+ at 10, 50, 100, 200, and 500 ppm. The concentration of Ca2+ in the mineralization medium after any cycle was subtracted from the average concentration of the same ion in fresh SBF (daily control); the obtained values were used in the determination of the cumulative calcium uptake.

The mineralization medium was also analyzed by UV–Vis spectrophotometry, and the method details are given in the Supporting Information.

2.6. Data analysis

FESEM images were analyzed with the software Fiji32 to measure the diameter of the collagen fibrils before and after the extrafibrillar mineralization. At least one hundred sites were analyzed considering fibrils in three different images per group. The graphing and data analysis were conducted using the software Origin 2016.

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

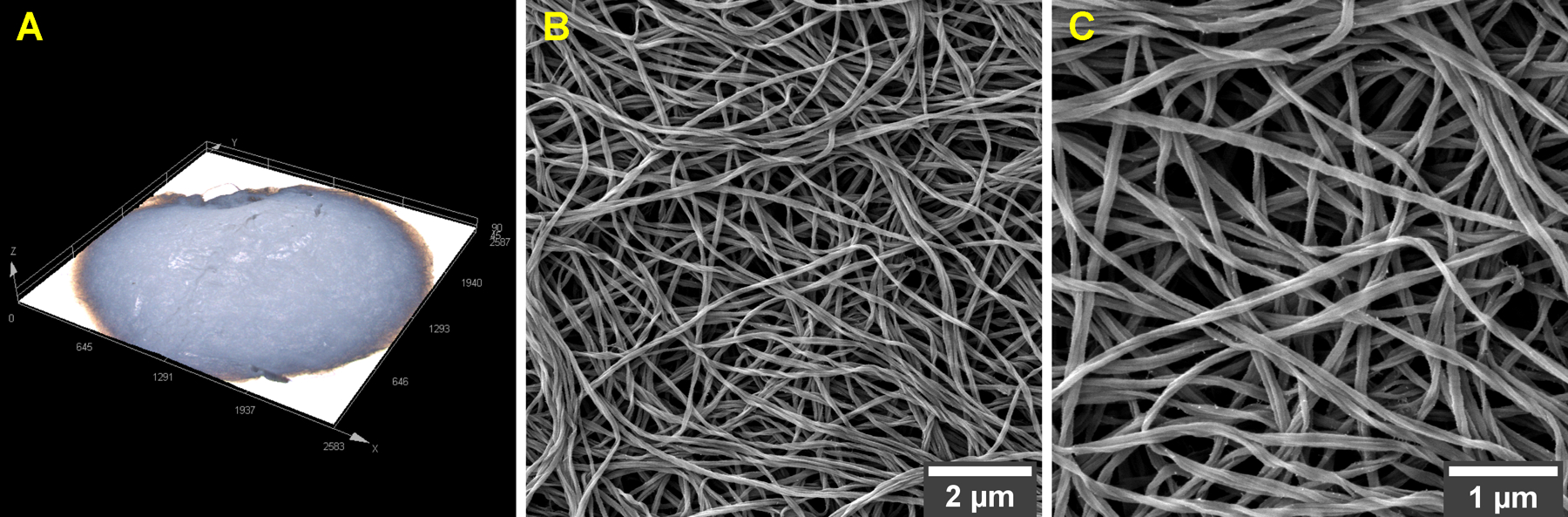

The fabrication of fibrous scaffolds for tissue engineering has been proposed by techniques such as electrospinning and sophisticated 3–D printing,33,34 but the scaffolding of collagen matrices has proved challenging.35 This study relied on a straightforward synthetic approach of nano-scaffold preparation by condensing collagen fibrils that had been assembled directly in microfuge tubes.31 The resulting collagen matrix appears like a sponge of millimetric dimensions (Figure 1A) that, in effect, is made up of a dense network of collagen fibrils with preserved interfibrillar spaces (Figure 1B,C). The random orientation of the nanofibrils resembles the arrangement of type-I collagen in the organic matrix of dentin, the mineralized tissue that forms the bulk of the tooth structure.2

Figure 1.

As-synthesized collagen matrix seen through (A) 3–D laser scanning microscopy and (B,C) FESEM at different magnifications. The high resolution FESEM images reveal a dense network of type-I collagen fibrils with preserved interfibrillar spaces. Magnifications, ×9500 (B) and ×20,000 (C).

To investigate the apatite-forming ability of type-I collagen, the in vitro fabrication of an isolated structural matrix was regarded as ideal to avoid bias arising from the complexity of native matrices. Collagen extracted directly from mineralized tissues (e.g., dentin) will inevitably carry intrinsic NCPs and residues of the mineral phase, adding extra variables to a mineralization study.3 By using standardized collagen matrices, our variables were limited to the strategy of delivery of calcium and phosphate ions to the fibrils, using ion-rich solutions and SBF.

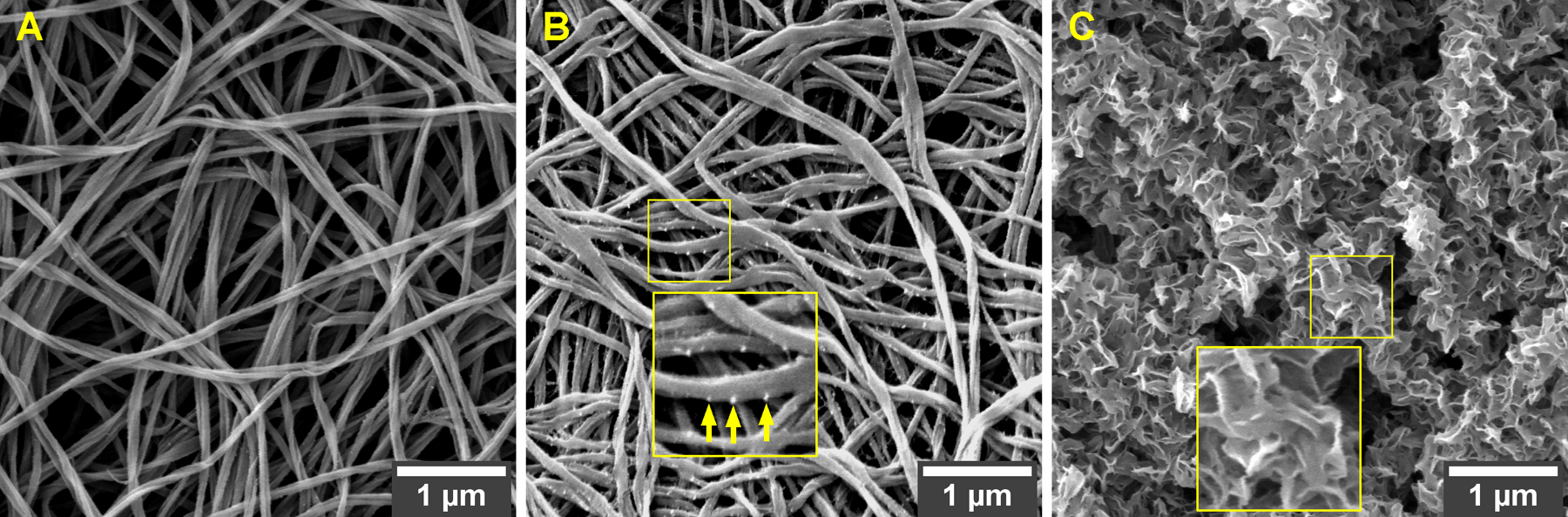

Extended (96-h) incubation in 1× SBF solely did not have any effect on the standard morphology of the as-synthesized collagen fibrils (Figure 2A). Presumably, the interface energy of the fibril–medium system was not low enough to enable the spontaneous nucleation of CaP from non-concentrated SBF.36 Characteristic nucleation sites appeared, though, on the surface of collagen fibrils that were soaked alternately for short periods (5 min) in solutions highly rich in calcium or phosphate ions (Figure 2B and Figure S3). In addition to the presence of nucleation sites, a pronounced contrast and fibrillar texture were observed in samples subjected to the alternate soaking. These surface alterations corroborate the successful loading of primary ionic species.37 Still, the exposure to calcium- and phosphate-rich solutions did not suffice to complete the formation of apatite nanocrystals on the surface of type I collagen (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

FESEM morphologies of collagen fibrils subjected to different mineralization approaches: (A) incubation in 1× SBF solely; (B) alternate soaking in calcium- and phosphate-rich ionic solutions solely; (C) alternate soaking followed by incubation in 1× SBF. Remarkable mineralization occurred only when the fibrils were incubated in SFB after an initial mineral induction (i.e., soaking in calcium- and phosphate-rich solutions). Arrows, nucleation sites. Magnification, ×20,000.

On the other hand, when collagen fibrils decorated with nucleation sites (i.e., fibrils subjected to alternate soaking in advance) were further incubated in SBF, a remarkable extrafibrillar mineralization was achieved (Figure 2C). A closer view of the apatitic coating’s texture reveals aggregates of plate-like crystals intimately associated with the fibrils (zoomed inset in Figure 2C). Similar plate-like morphology has been attributed to biomimetic apatites previously.38 Also, the crystals cover the fibrils in a continuous fashion, that is, gaps of bare collagen are not observed. What is particularly notable is that the dense mineralization pattern obtained with SBF differs from past reports stating that, in the absence of process-directing polymers, CaP will precipitate mostly as random, large extrafibrillar deposits on the fibrils network.8

The successful extrafibrillar mineralization evidenced in Figure 2C is accredited to the combination of two steps: (a) mineral induction via preloading and (b) apatite formation during incubation in SBF. A similar multistep approach has been adopted before in the mineralization of synthetic nanofibers relying on the SBF's potential to generate apatite.33 The mineral induction step, consisting in alternate exposure to high concentrations of Ca2+ and PO4−3 ions, is intended for increasing the local saturation within the porous matrix to induce a rapid emergence of reactive sites.39 On the fibrils' surface, it is possible to observe spherical aggregates (see arrows in Figure 2B), probably representing amorphous calcium phosphate (ACP) nuclei that facilitated a subsequent surface-directed mineralization process.6 To induce crystal growth and crystallization, these nuclei were further exposed to 1× SBF, a medium with an ionic composition and pH similar to blood plasma. It is known that preloading inert surfaces with precursor ions/ clusters augments substantially the SBF's ability to form apatite.36

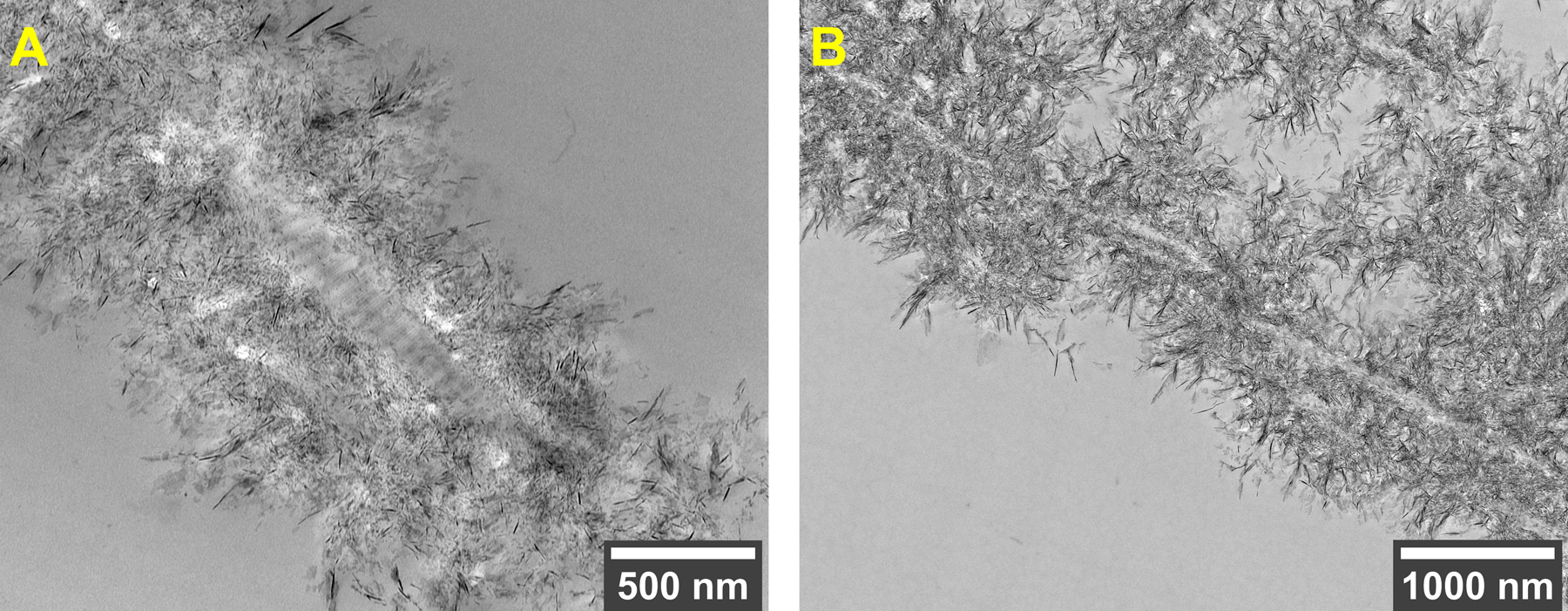

TEM micrographs provide a better understanding of the spatial relationship between the organic and inorganic components in the mineralized scaffold (Figure 3). Seamless integration between the apatitic coating and the collagen surface can be observed (Figure 3A). The apatite crystals grew to form aggregates of needle-like structures sheathing the collagen fibrils (Figure 3B). With a mineralization protocol devoid of process-directing polymers, we could not find proof of the presence of intrafibrillar minerals in the representative TEM images (Figure S4). On the other hand, collagen fibrils mineralized via the PILP mechanism did not show any evidence of extrafibrillar crystals (Figure S5). In the presence of pAsp, the mineral failed to form on the surface of the collagen fibrils – presumably due to the polymer's inhibitory property.

Figure 3.

TEM images of type-I collagen fibrils mineralized in 1× SBF following the mineral induction step (preloading). (A) Longitudinal section of a banded collagen fibril completely encased by extrafibrillar apatite crystals in intimate contact with the collagen structure. (B) At lower magnification, it is possible to observe a continuous fibril strand surrounded by in-situ mineralized apatite crystals, which appear as dark needles due to the high electron density of crystalline CaP. Specimens lightly post-stained with uranyl acetate. Direct magnification, ×15,000 (A) and ×8000 (B).

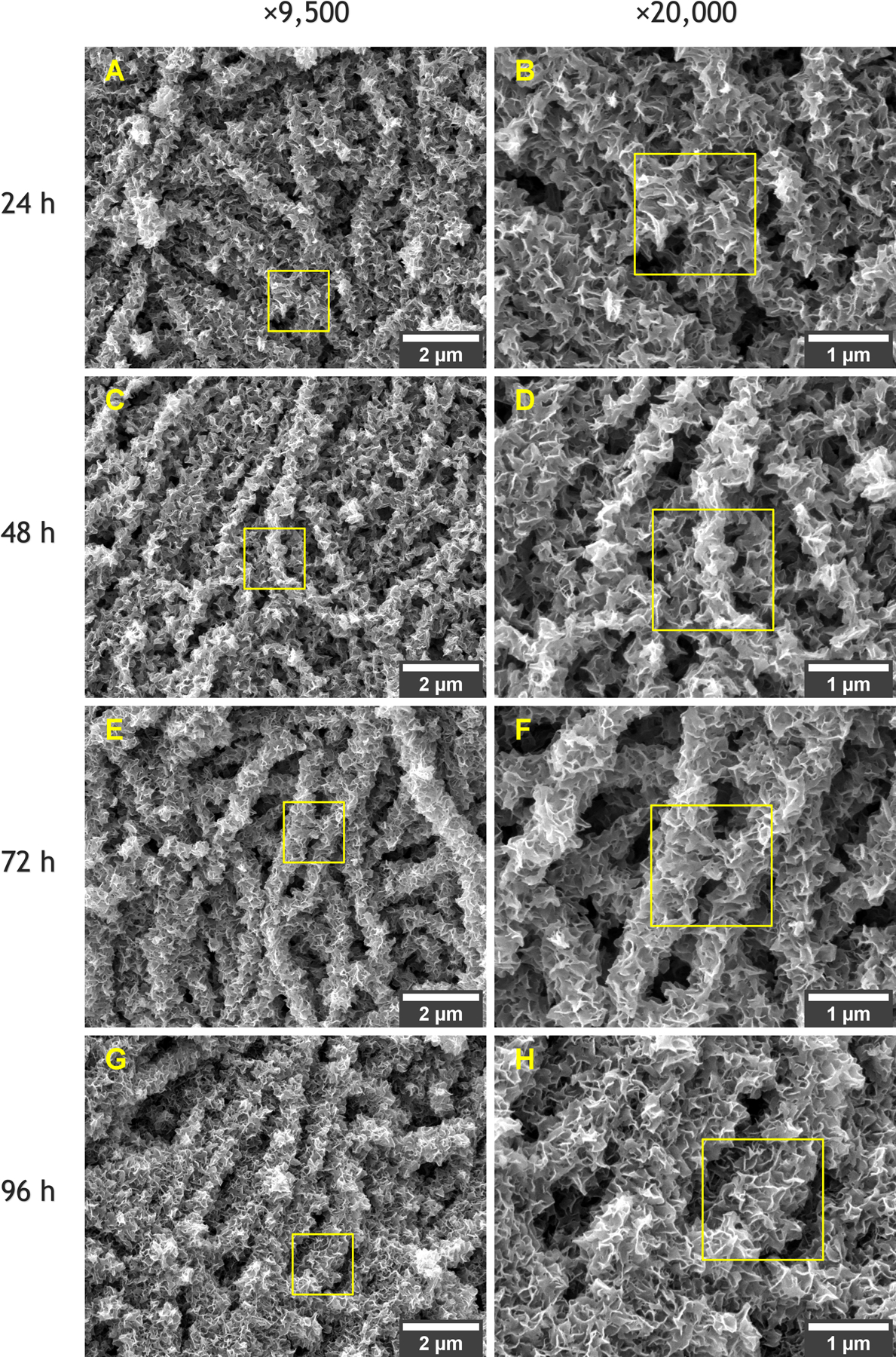

To evaluate the effect of time on the formation of apatite as an inorganic coating, collagen fibrils were incubated in 1× SFB for one to four days (a regimen of 24-h incubation cycles as described in Table 1). The FESEM images in Figure 4 illustrate the surface morphology of the apatitic coatings obtained after each day/cycle of incubation. A continuous lamellar texture was found after the first 24 h and persisted for all incubation times.

Figure 4.

FESEM morphologies of collagen fibrils mineralized in SBF after incubation for (A,B) 24 h, (C,D) 48 h, (E,F) 72 h, and (G,H) 96 h. Yellow squares highlight the transitions between magnifications of ×9500 and ×20,000 for the same detail.

It is possible to notice the evolution in the thickness of the inorganic coatings with time, which are particularly evident when comparing the mineralized fibrils after 24 h and 96 h of incubation in SBF. Figure 5 clarifies how the total incubation time affected the thickness of the fibrils due to the gradual deposition of apatite on the collagen surface. The average diameter of the control/as-synthesized collagen fibrils was 0.113 μm ± 0.01 and matches well with the typical diameter of type-I collagen reported in the literature.40 Compared to the control fibrils, extended incubation in SBF caused an increase in diameter of nearly 5× (24 h), 6× (48 h), 7× (72 h), and 8× (96 h) according to the results in Figure 5F.

Figure 5.

Histograms showing the statistical distributions of diameter of (A) the control/as-synthesized collagen fibrils and (B–E) fibrils mineralized in SBF after incubation for 24–96 h. (F) Evolution of the average diameter with time as a consequence of gradual mineralization of apatite around the fibrils. Extended incubation in SBF for 96 h promoted an eightfold increase in diameter compared to the control collagen fibrils.

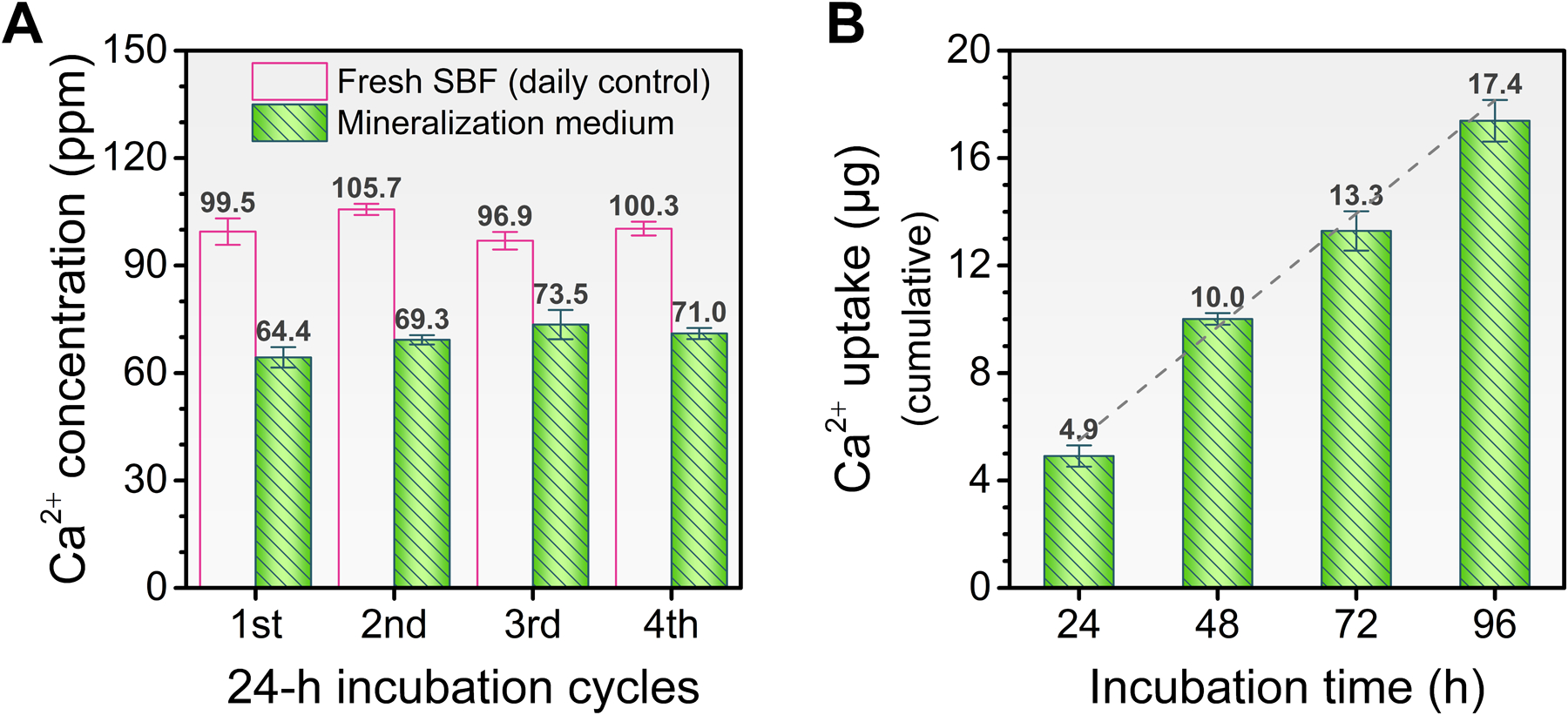

The daily increments in thickness of the apatitic coatings were accompanied by steady reductions in the concentration of Ca2+ in the crystallizing medium after each 24-h incubation cycle (Figure 6A). Accordingly, an increasing linear trend was observed for the cumulative Ca2+ uptake (Figure 6B), representing a progressive extrafibrillar mineralization. The analysis of the crystalizing medium also showed that the amount of apatite that precipitated in the bulk solution was negligible, corroborating the dominance of a surface-directed mineralization process (Figure S6).

Figure 6.

(A) Concentration of Ca2+ ions in the mineralization medium after each 24-h incubation cycle. (B) Cumulative uptake of Ca2+ ions from the mineralization medium according to the total incubation time. Continuous extrafibrillar mineralization is verified by an increasing linear trend (dashed line) in the Ca2+ uptake (from the media to the fibrils' surface) during the incubation in SBF.

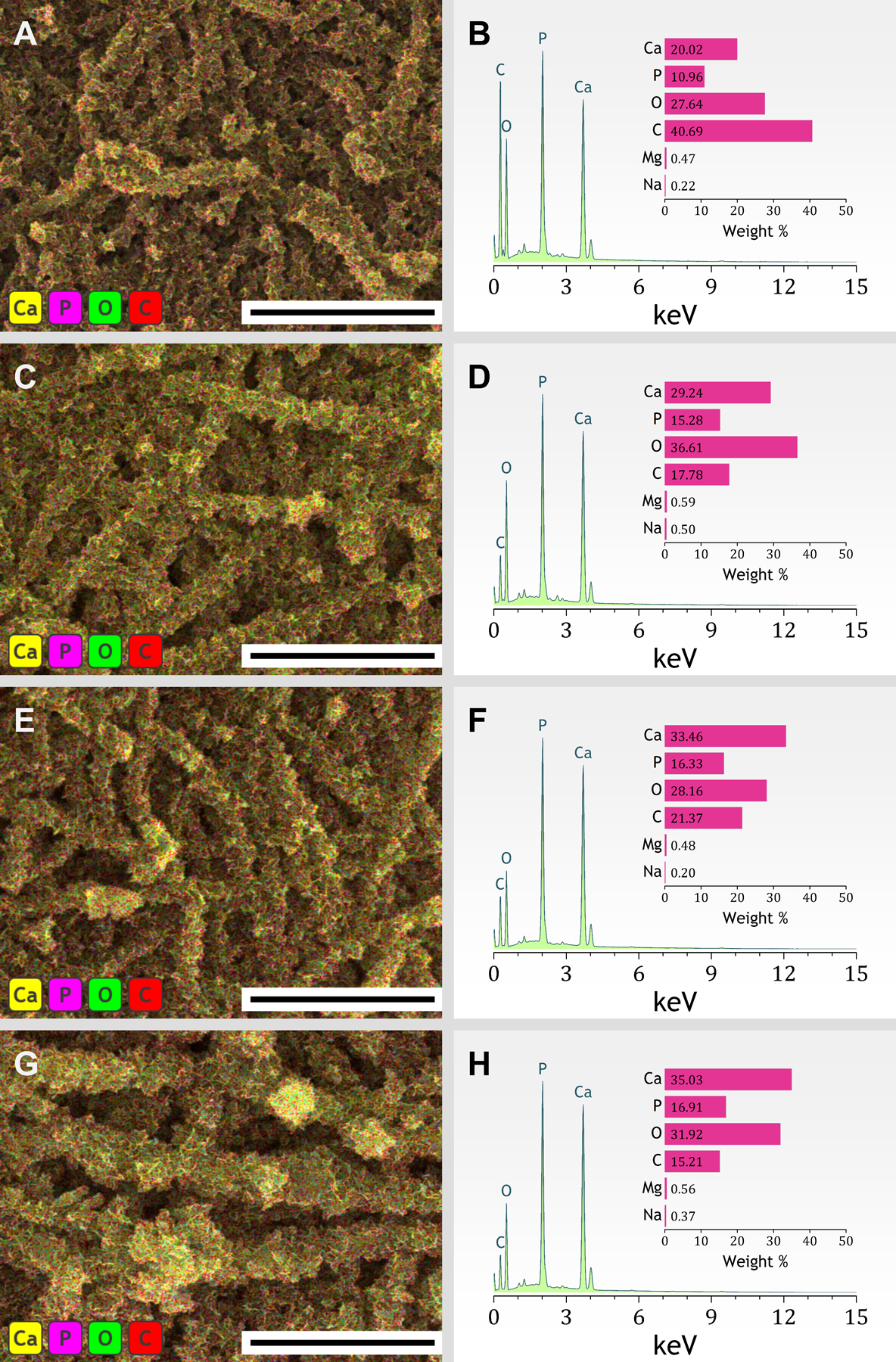

In terms of composition, the elemental mapping of microstructures by FESEM–EDS confirms that, after mineralization, all collagen matrices exhibited Ca, P and O as the most abundant elements on their surfaces (Figure 7). The averaged relative concentrations of elements are reported in the Supporting Information, Table S2. The predominance of the elements Ca, P, and O certifies that the mineral coatings developed around the fibrils are related to CaP (regardless of the incubation time). Also, the presence of C (> 15 wt.%) implies the formation of a carbonated (and thus non-stoichiometric) apatite, which is further reinforced by the identification of CO3−2 and PO4−3 stretch modes in the Raman spectrum of mineralized fibrils (Figure S7). Very low relative concentrations of Na (< 0.5 wt.%) and Mg (< 0.6 wt.%) are consonant with the composition of a bone-like apatite, as these cations are commonly found as impurities in the bone mineral.41

Figure 7.

(Left) Representative FESEM–EDS layered images and (right) EDS spectra of collagen fibrils mineralized in SBF for (A,B) 24 h, (C,D) 48 h, (E,F) 72 h, and (G,H) 96 h. Scale bars, 5 μm. Insets, relative concentration of the elements Calcium, Phosphorous, Oxygen, Carbon, Magnesium, and Sodium.

The elemental analysis using EDS also shows that an increase in incubation time resulted in collagen–apatite composites that possess higher calcium to phosphorus atomic ratios (Figure 8). After the first 24 h of incubation in SBF, the low Ca/P ratio (1.45 ± 0.05) suggests the early occurrence of metastable polymorphs such as ACP or octacalcium phosphate.8,26 The metastable precursor later transforms into a mineral exhibiting a Ca/P ratio of 1.61 ± 0.04 (and small amounts of Na and Mg as evidenced in Figure 7), which falls within the range of biological apatites.

Figure 8.

Effect of incubation time on the Ca/P atomic ratio of the apatitic coatings mineralized around the collagen fibrils. Extended incubation in SBF enabled the transformation of precursor species (lower Ca/P ratios) into a carbonated apatite with Ca/P ratio of 1.61 ± 0.04. TCP, tricalcium phosphate.

Biological apatites refer to calcium phosphate as the product of the biomineralization process, which depart in many respects from the model, stoichiometric HA.42 The latter has a known composition [Ca10(PO4)6(OH)2], standard Ca/P ratio of ~ 1.67, and is considered to be the highly stable and crystalline product of the precipitation of calcium and phosphate ions in solution. Due to the rich ionic composition of the native environment (blood serum), biological apatites undergo massive ionic exchanges – especially of OH or PO4 by CO3 – resulting in carbonated minerals that are less crystalline and stable than HA.43

Considering that the SBF's composition equates to that of the human blood serum, the formation of apatite in SBF will commonly reflect the characteristic impurity of a biological apatite.26 Note that inherent lower stability plays a critical role in the dissolution and formation of crystals in biological tissues.44 Thus, it should be taken as a desirable characteristic to mimic from bones in vitro. It is worthwhile to mention that reactions based on process-directing polymers (e.g., pAsp) typically result in the formation of a more crystalline (hydroxi)apatite, because the crystalizing medium containing the polymer additive is simplified.14,28 This particular fact represents a gap in understanding the interplay between the polymer-induced precursor phase and the extracellular fluid in the biomineralization process.

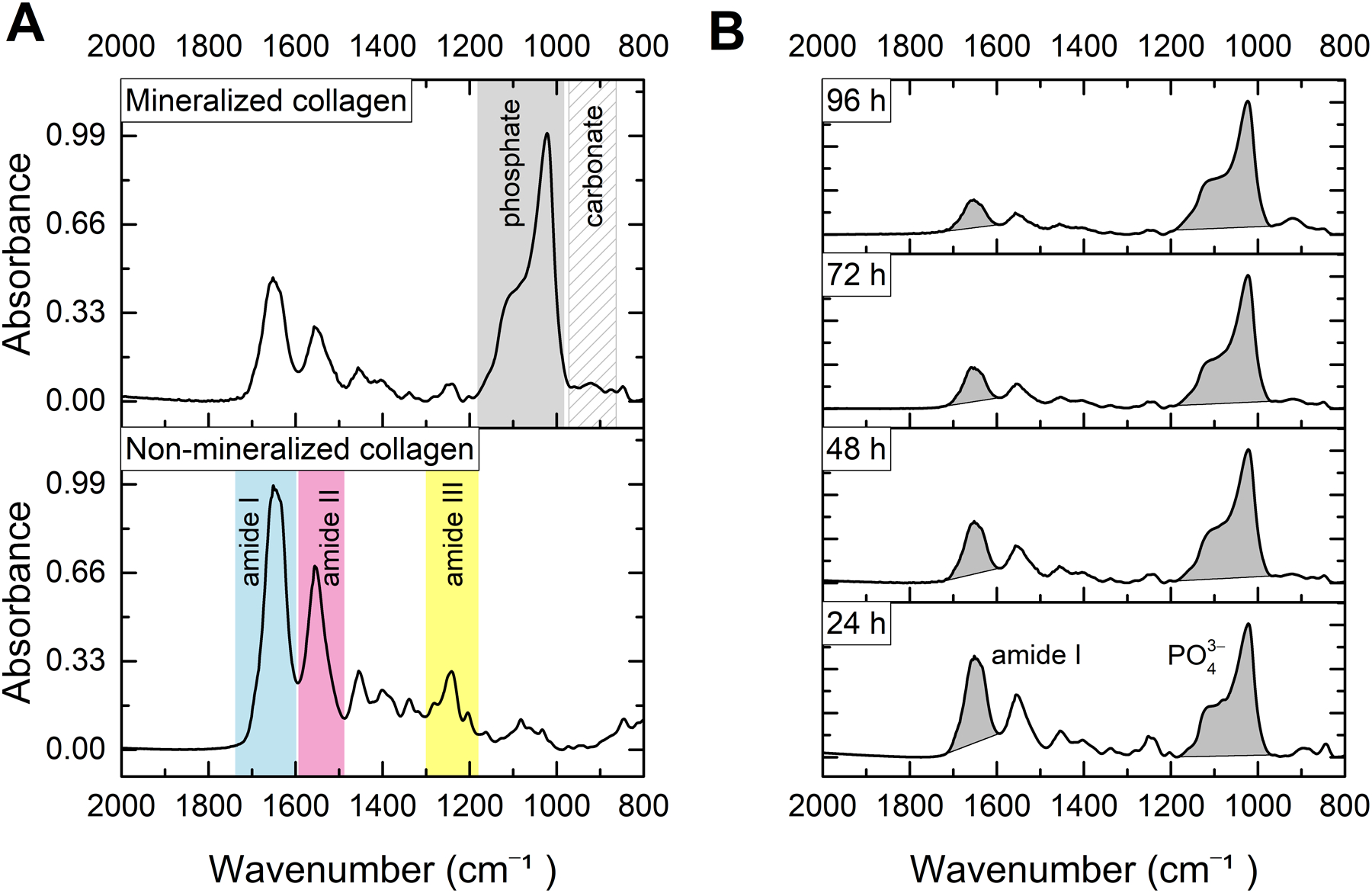

The compositional characterization of the mineralized scaffolds via infrared spectroscopy supports the development of a biomimetic mineral within the collagen network (Figure 9). The non-mineralized fibrous scaffold shows band characteristics of type-I collagen,45 including the prominent peak of amide I (C=O stretch) at ~ 1650 cm−1, amide II at ~ 1555 cm−1, as well as the moderate absorptions arising from amide III in the range of 1300–1180 cm−1 (Figure 9A). In mineralized samples, the main features of the collagen spectrum are preserved, but a distinctive peak appears at ~ 1022 cm−1 (Figure 9A) due to the v3 PO4 asymmetric stretch in the biomimetic crystals.46 After 96 h of mineralization, a thin band is also detected at ~ 875 cm−1 (see detail in Figure S8), which is assignable to HPO4 2− ions in nanocrystalline apatites.47 Extended incubation in SBF led to a decrease in the area of the amide I band as the collagen structure became less accessible with the thickening of the external apatitic coating (Figure 9B). Accordingly, the ratio (by area) of phosphate to amide I increased with the incubation time: 2.3 ± 1.3 (24 h); 5.1 ± 1.4 (48 h); 5.2 ± 1.5 (72 h); 5.7 ± 0.6 (96 h).

Figure 9.

FTIR–ATR analysis. (A) Absorbance spectra of nonmineralized and apatite-mineralized collagen fibrils. (B) Normalized spectra of collagen fibrils mineralized after incubation in SBF for 24–96 h. Extended incubation in SBF led to a decrease in the peak intensity of the amide I band as the collagen structure became less accessible with the thickening of the external apatitic coating.

Some past investigations involving SBF focused on the bioactivity or mechanical performance of the collagen–apatite struts, whereas little is available regarding the nucleation and growth of the mineral phase at the resolution of a collagen fibril.23,24 The present study sheds light on fundamental aspects (e.g., nucleation pathway, crystal morphology, and mineralization times) of the formation of CaP mineral phases in porous collagen scaffolds using 1× SBF. In brief, we demonstrate that the mineral induction step (i.e., preloading) can enhance the apatite-forming ability of type-I collagen in non-concentrated SBF, leading to a remarkable extrafibrillar mineralization pattern. The crystals formed as a continuous coating surrounding the collagen fibrils, instead of random spherulites.

Recently, Kim and collaborators30 had addressed a possible mechanism of nucleation of CaP in the unconfined extrafibrillar spaces (i.e., extrafibrillar mineralization) using 3× SBF. The authors concluded that the unconfined nucleation is favored in the absence of nucleation inhibitors (e.g., pAsp) and involves the aggregation of prenucleation clusters to form spherical ACP as an intermediate product. In our model system, the preloading step can be seen as a shortcut to obtain the spherical ACP nanoprecursors, which enable a subsequent mineralization of extrafibrillar crystals in the non-concentrated, less reactive SBF medium.

In terms of function, the thick crystalline coating synthesized in situ could offer protection and mechanical support for the delicate collagen structure due to the mechanical stiffness of apatite. Furthermore, a biocompatible scaffold covered with biomimetic apatite is expected to promptly adhere to living bone,26 which is a requisite for a bone graft material, for example.

We believe that the proposed mineralization protocol could help design collagen–apatite scaffolds that are osteoconductive and highly biocompatible. Repair of demineralized dentin, a leading topic in dental research,3 is another potential application that our group is currently investigating.

4. CONCLUSIONS

Reconstituted type-I collagen fibrils can induce per se the mineralization of apatite in SBF via a surface-directed process after preloading the fibrils with amorphous precursors. This quick mineral induction step leads to a remarkable extrafibrillar mineralization (aggregated apatite) in non-concentrated SBF – in contrast with reactions typically requiring modified SBF versions. Devoid of the need of NCPs analogs, the proposed protocol may offer an advantage in the development of densely mineralized collagen–apatite composites for bone tissue engineering and repair of extracellular matrix.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported by the São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP, grant # 2019/08586-0) and National Institute of Health (NIH, grant # R01DE028194). The careful laboratory assistance provided by Olivia Thomson and Figen Seiler (University of Illinois at Chicago, Research Resources Center, Electron Microscopy Core) was greatly appreciated. We are grateful to Morteza Rasoulianboroujeni for his help with the graphic design.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

Complementary methods, extra FESEM/ TEM analysis, UV–Vis spectrophotometry, and Raman spectroscopy.

REFERENCES

- (1).Weiner S; Wagner HD THE MATERIAL BONE: Structure-Mechanical Function Relations. Annu. Rev. Mater. Sci 1998, 28 (1), 271–298. 10.1146/annurev.matsci.28.1.271. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Bertassoni LE Dentin on the Nanoscale: Hierarchical Organization, Mechanical Behavior and Bioinspired Engineering. Dent. Mater 2017, 33 (6), 637–649. 10.1016/j.dental.2017.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Niu L; Zhang W; Pashley DH; Breschi L; Mao J; Chen J; Tay FR Biomimetic Remineralization of Dentin. Dent. Mater 2014, 30 (1), 77–96. 10.1016/j.dental.2013.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Leonor IB; Rodrigues AI; Reis RL Designing Biomaterials Based on Biomineralization for Bone Repair and Regeneration. In Biomineralization and Biomaterials; Elsevier, 2016; pp 377–404. 10.1016/B978-1-78242-338-6.00014-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Iwayama T; Okada T; Ueda T; Tomita K; Matsumoto S; Takedachi M; Wakisaka S; Noda T; Ogura T; Okano T; Fratzl P; Ogura T; Murakami S Osteoblastic Lysosome Plays a Central Role in Mineralization. Sci. Adv 2019, 5 (7), eaax0672. 10.1126/sciadv.aax0672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Dey A; Bomans PHH; Müller FA; Will J; Frederik PM; de With G; Sommerdijk NAJM The Role of Prenucleation Clusters in Surface-Induced Calcium Phosphate Crystallization. Nat. Mater 2010, 9 (12), 1010–1014. 10.1038/nmat2900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Gehron Robey P Noncollagenous Bone Matrix Proteins. In Principles of Bone Biology; Elsevier, 2008; pp 335–349. 10.1016/B978-0-12-373884-4.00036-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Gower LB Biomimetic Model Systems for Investigating the Amorphous Precursor Pathway and Its Role in Biomineralization. Chem. Rev 2008, 108 (11), 4551–4627. 10.1021/cr800443h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Nudelman F; Pieterse K; George A; Bomans PHH; Friedrich H; Brylka LJ; Hilbers PAJ; de With G; Sommerdijk NAJM The Role of Collagen in Bone Apatite Formation in the Presence of Hydroxyapatite Nucleation Inhibitors. Nat. Mater 2010, 9 (12), 1004–1009. 10.1038/nmat2875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Olszta MJ; Douglas EP; Gower LB Intrafibrillar Mineralization of Collagen Using a Liquid-Phase Mineral Precursor. MRS Proc. 2003, 774, O7.10. 10.1557/PROC-774-O7.10. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Tay FR; Pashley DH Guided Tissue Remineralisation of Partially Demineralised Human Dentine. Biomaterials 2008, 29 (8), 1127–1137. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Grue BH; Veres SP Use of Tendon to Produce Decellularized Sheets of Mineralized Collagen Fibrils for Bone Tissue Repair and Regeneration. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part B Appl. Biomater 2020, 108 (3), 845–856. 10.1002/jbm.b.34438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Olszta MJ; Odom DJ; Douglas EP; Gower LB A New Paradigm for Biomineral Formation: Mineralization via an Amorphous Liquid-Phase Precursor. Connect. Tissue Res 2003, 44 (1), 326–334. 10.1080/03008200390181852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Olszta MJ; Cheng X; Jee SS; Kumar R; Kim Y-Y; Kaufman MJ; Douglas EP; Gower LB Bone Structure and Formation: A New Perspective. Mater. Sci. Eng. R Reports 2007, 58 (3–5), 77–116. 10.1016/j.mser.2007.05.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Gower LB Biomimetic Mineralization of Collagen. In Biomineralization and Biomaterials; Elsevier, 2016; pp 187–232. 10.1016/B978-1-78242-338-6.00007-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Fratzl P; Gupta HS; Paschalis EP; Roschger P Structure and Mechanical Quality of the Collagen–Mineral Nano-Composite in Bone. J. Mater. Chem 2004, 14 (14), 2115–2123. 10.1039/B402005G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Pashley DH; Agee KA; Wataha JC; Rueggeberg F; Ceballos L; Itou K; Yoshiyama M; Carvalho RM; Tay FR Viscoelastic Properties of Demineralized Dentin Matrix. Dent. Mater 2003, 19 (8), 700–706. 10.1016/S0109-5641(03)00016-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Nair AK; Gautieri A; Chang S-W; Buehler MJ Molecular Mechanics of Mineralized Collagen Fibrils in Bone. Nat. Commun 2013, 4 (1), 1724. 10.1038/ncomms2720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Bedran-Russo AK; Pauli GF; Chen S-N; McAlpine J; Castellan CS; Phansalkar RS; Aguiar TR; Vidal CMP; Napotilano JG; Nam J-W; Leme AA Dentin Biomodification: Strategies, Renewable Resources and Clinical Applications. Dent. Mater 2014, 30 (1), 62–76. 10.1016/j.dental.2013.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Bertassoni LE; Habelitz S; Kinney JH; Marshall SJ; Marshall GW Jr. Biomechanical Perspective on the Remineralization of Dentin. Caries Res. 2009, 43 (1), 70–77. 10.1159/000201593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).McNally EA; Schwarcz HP; Botton GA; Arsenault AL A Model for the Ultrastructure of Bone Based on Electron Microscopy of Ion-Milled Sections. PLoS One 2012, 7 (1), e29258. 10.1371/journal.pone.0029258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Stock SR The Mineral–Collagen Interface in Bone. Calcif. Tissue Int 2015, 97 (3), 262–280. 10.1007/s00223-015-9984-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Al-Munajjed AA; Plunkett NA; Gleeson JP; Weber T; Jungreuthmayer C; Levingstone T; Hammer J; O’Brien FJ Development of a Biomimetic Collagen-Hydroxyapatite Scaffold for Bone Tissue Engineering Using a SBF Immersion Technique. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part B Appl. Biomater 2009, 90 (2), 584–591. 10.1002/jbm.b.31320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Hu C; Zilm M; Wei M Fabrication of Intrafibrillar and Extrafibrillar Mineralized Collagen/Apatite Scaffolds with a Hierarchical Structure. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part A 2016, 104 (5), 1153–1161. 10.1002/jbm.a.35649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Wang Q; Miao L; Zhang H; Wang SQ; Li Q; Sun W A Novel Amphiphilic Oligopeptide Induced the Intrafibrillar Mineralisation via Interacting with Collagen and Minerals. J. Mater. Chem. B 2020, 8 (11), 2350–2362. 10.1039/C9TB02928A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Kokubo T; Kim H-M; Kawashita M Novel Bioactive Materials with Different Mechanical Properties. Biomaterials 2003, 24 (13), 2161–2175. 10.1016/S0142-9612(03)00044-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Kokubo T; Yamaguchi S Simulated Body Fluid and the Novel Bioactive Materials Derived from It. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part A 2019, 107 (5), 968–977. 10.1002/jbm.a.36620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Kokubo T; Takadama H How Useful Is SBF in Predicting in Vivo Bone Bioactivity? Biomaterials 2006, 27 (15), 2907–2915. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Wang Y; Azaïs T; Robin M; Vallée A; Catania C; Legriel P; Pehau-Arnaudet G; Babonneau F; Giraud-Guille M-M; Nassif N The Predominant Role of Collagen in the Nucleation, Growth, Structure and Orientation of Bone Apatite. Nat. Mater 2012, 11 (8), 724–733. 10.1038/nmat3362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Kim D; Lee B; Thomopoulos S; Jun Y-S The Role of Confined Collagen Geometry in Decreasing Nucleation Energy Barriers to Intrafibrillar Mineralization. Nat. Commun 2018, 9 (1), 962. 10.1038/s41467-018-03041-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Loo RW; Goh JB; Cheng CCH; Su N; Goh MC In Vitro Synthesis of Native, Fibrous Long Spacing and Segmental Long Spacing Collagen. J. Vis. Exp 2012, No. e4417. 10.3791/4417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Schindelin J; Arganda-Carreras I; Frise E; Kaynig V; Longair M; Pietzsch T; Preibisch S; Rueden C; Saalfeld S; Schmid B; Tinevez J-Y; White DJ; Hartenstein V; Eliceiri K; Tomancak P; Cardona A Fiji: An Open-Source Platform for Biological-Image Analysis. Nat. Methods 2012, 9 (7), 676–682. 10.1038/nmeth.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Yu H-S; Jang J-H; Kim T-I; Lee H-H; Kim H-W Apatite-Mineralized Polycaprolactone Nanofibrous Web as a Bone Tissue Regeneration Substrate. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part A 2009, 88 (3), 747–754. 10.1002/jbm.a.31709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Wang C; Huang W; Zhou Y; He L; He Z; Chen Z; He X; Tian S; Liao J; Lu B; Wei Y; Wang M 3D Printing of Bone Tissue Engineering Scaffolds. Bioact. Mater 2020, 5 (1), 82–91. 10.1016/j.bioactmat.2020.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Lee A; Hudson AR; Shiwarski DJ; Tashman JW; Hinton TJ; Yerneni S; Bliley JM; Campbell PG; Feinberg AW 3D Bioprinting of Collagen to Rebuild Components of the Human Heart. Science (80-. ). 2019, 365 (6452), 482–487. 10.1126/science.aav9051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Bohner M; Lemaitre J Can Bioactivity Be Tested in Vitro with SBF Solution? Biomaterials 2009, 30 (12), 2175–2179. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Thula TT; Svedlund F; Rodriguez DE; Podschun J; Pendi L; Gower LB Mimicking the Nanostructure of Bone: Comparison of Polymeric Process-Directing Agents. Polymers (Basel). 2010, 3 (1), 10–35. 10.3390/polym3010010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Sadowska JM; Wei F; Guo J; Guillem-Marti J; Lin Z; Ginebra M-P; Xiao Y The Effect of Biomimetic Calcium Deficient Hydroxyapatite and Sintered β-Tricalcium Phosphate on Osteoimmune Reaction and Osteogenesis. Acta Biomater. 2019, 96, 605–618. 10.1016/j.actbio.2019.06.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Douglas TEL Biomimetic Mineralization of Hydrogels. In Biomineralization and Biomaterials; Elsevier, 2016; pp 291–313. 10.1016/B978-1-78242-338-6.00010-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Fratzl P Collagen: Structure and Mechanics, an Introduction. In Collagen; Springer US: Boston, MA; pp 1–13. 10.1007/978-0-387-73906-9_1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Rey C; Combes C Physical Chemistry of Biological Apatites. In Biomineralization and Biomaterials; Elsevier, 2016; pp 95–127. 10.1016/B978-1-78242-338-6.00004-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Elliott JC Calcium Phosphate Biominerals. Rev. Mineral. Geochemistry 2002, 48 (1), 427–453. 10.2138/rmg.2002.48.11. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Bigi A; Boanini E; Gazzano M Ion Substitution in Biological and Synthetic Apatites. In Biomineralization and Biomaterials; Elsevier, 2016; pp 235–266. 10.1016/B978-1-78242-338-6.00008-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Barrère F; van Blitterswijk CA; de Groot K Bone Regeneration: Molecular and Cellular Interactions with Calcium Phosphate Ceramics. Int. J. Nanomedicine 2006, 1 (3), 317–332. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Belbachir K; Noreen R; Gouspillou G; Petibois C Collagen Types Analysis and Differentiation by FTIR Spectroscopy. Anal. Bioanal. Chem 2009, 395 (3), 829–837. 10.1007/s00216-009-3019-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Tao J FTIR and Raman Studies of Structure and Bonding in Mineral and Organic–Mineral Composites; 2013; pp 533–556. 10.1016/B978-0-12-416617-2.00022-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Drouet C Apatite Formation: Why It May Not Work as Planned, and How to Conclusively Identify Apatite Compounds. Biomed Res. Int 2013, 2013, 1–12. 10.1155/2013/490946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.