Abstract

Increases in calorie consumption and sedentary lifestyles are fuelling a global pandemic of cardiometabolic diseases, including coronary artery disease, diabetes mellitus, cardiomyopathy and heart failure. These lifestyle factors, when combined with genetic predispositions, increase the levels of circulating lipids, which can accumulate in non-adipose tissues, including blood vessel walls and the heart. The metabolism of these lipids produces bioactive intermediates that disrupt cellular function and survival. A compelling body of evidence suggests that sphingolipids, such as ceramides, account for much of the tissue damage in these cardiometabolic diseases. In humans, serum ceramide levels are proving to be accurate biomarkers of adverse cardiovascular disease outcomes. In mice and rats, pharmacological inhibition or depletion of enzymes driving de novo ceramide synthesis prevents the development of diabetes, atherosclerosis, hypertension and heart failure. In cultured cells and isolated tissues, ceramides perturb mitochondrial function, block fuel usage, disrupt vasodilatation and promote apoptosis. In this Review, we discuss the body of literature suggesting that ceramides are drivers — and not merely passengers — on the road to cardiovascular disease. Moreover, we explore the feasibility of therapeutic strategies to lower ceramide levels to improve cardiovascular health.

The prevalence of obesity in the USA and most other locations globally is increasing rapidly, with nearly 70% of adults in the USA classified as being either overweight or obese by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention1. Overnutrition, sedentary behaviour and genetics contribute to the development of obesity and its comorbidities, including type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, coronary artery disease, cardiomyopathy and heart failure (HF). These cardiovascular disorders are major causes of morbidity and mortality in the general population and account for a staggering percentage of medical costs. New therapeutic approaches are needed to combat these costly and deadly diseases.

Excessive lipid deposition in non-adipose organs, such as blood vessel walls and the heart, contributes to the development of these cardiovascular disorders. In healthy tissues, free fatty acids are metabolized via β-oxidation to produce ATP. When caloric consumption exceeds demand, the excess free fatty acids are packaged onto a glycerol backbone to produce inert triglycerides, which can be safely stored in lipid droplets within the cells. Sometimes, however, these pathways become saturated, meaning that deleterious, bioactive lipids start to accumulate. These molecules disrupt heart and blood vessel function to drive the aforementioned diseases. Of the many lipid metabolites that accrue under these conditions, sphingolipids (such as ceramides) are particularly damaging to blood vessels and the heart.

Ceramides are formed by a ubiquitous biosynthetic pathway that starts with the condensation of palmitoyl-CoA and an amino acid (most often serine) to create a sphingoid backbone. This scaffold acquires an additional, variable fatty acid to become a ceramide, which is the base building block for complex sphingolipids. In addition to performing structural roles in cell membranes, ceramides function as intracellular signals of free fatty acid abundance, initiating responses that allow cells to cope with the lipid burden during physiological or nutritional stress. In the long term, these actions contribute to the pathophysiology of type 2 diabetes, fatty liver disease, hypertension, atherosclerosis and HF2-4. In humans, circulating ceramide levels have emerged as predictive biomarkers of cardiometabolic complications, including coronary artery disease, diabetes, HF, major adverse cardiac events and death5-24. In mice and rats, inhibition of ceramide biosynthesis ameliorates hallmark features of cardiometabolic disease, including insulin resistance, glucose intolerance, diabetes, atherosclerotic plaque formation, hypertension and HF25-30. Understanding the molecular mechanisms that control ceramide metabolism and action could reveal new therapeutic strategies for treating cardiometabolic disorders. In this Review, we provide perspectives on how ceramides contribute to cardiovascular dysfunction, focusing on their actions in two organs: the vascular endothelium and the heart.

Ceramide biosynthesis and metabolism

Ceramides are essential precursors of most of the complex sphingolipids, including sphingomyelins, glucosylceramides and sphingosine. These sphingolipids are localized in lipid bilayers, where they perform numerous structural functions31,32. Sphingomyelins are the most abundant sphingolipids in cells, whereas the less abundant ceramides and sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P) function as dynamic signalling molecules. In particular, ceramides are recognized to be central modulators of the cellular stress response33-35. The fundamental biosynthetic pathway that produces ceramides and other sphingolipids is operational in every tissue.

Sphingolipid synthesis starts in the endoplasmic reticulum with the condensation of palmitoyl-CoA and serine, a reaction that is catalysed by the multi-subunit and highly regulated enzyme complex serine palmitoyltransferase (SPT)36 (FIG. 1). Two essential subunits, SPTLC1 and SPTLC2, are required for enzyme function. Other subunits, such as SPTLC3, alter substrate specificity, allowing alternative fatty or amino acids to be incorporated to produce less abundant sphingolipid species37,38. In the canonical reaction, palmitoyl-CoA and serine are used as substrates to produce 3-ketosphinganine, which is rapidly converted into sphinganine by 3-ketosphinganine reductase.

Fig. 1 ∣. Pathways controlling ceramide levels in the cardiovascular system.

Schematic depiction of the major pathways controlling ceramide levels in the heart and vascular endothelium: de novo synthesis, hydrolysis of complex sphingolipids (for example, sphingomyelin hydrolysis) and the salvage pathway. 3KSR, 3-ketosphinganine reductase; CDase, ceramidase; CERS, ceramide synthase; DES1, dihydroceramide desaturase 1; SK, sphingosine kinase; SMase, sphingomyelinase; SMS, sphingomyelin synthase; SPT, serine palmitoyltransferase.

Ceramide synthases, which include six different family members (CERS1–CERS6) encoded by distinct genes, transfer a fatty acid from acyl-CoA to the sphinganine scaffold, forming dihydroceramide. The CERS enzymes differ according to tissue type and substrate specificity and account for much of the diversity in the sphingolipid family39 (TABLE 1). CERS2, which adds very-long-chain fatty acids (C20–C26) to the sphinganine scaffold, is abundant in many tissues, including the liver, kidneys and heart40. CERS4, which adds long-chain fatty acids (C18–C20), is abundant in the heart41. CERS5, which produces C14 and C16 ceramides, has also been implicated in the regulation of cardiac function42. CERS6, which also produces C14 and C16 ceramides, is upregulated in obesity and is most strongly implicated in the metabolic disturbances observed in adipose tissue and the liver43-47.

Table 1 ∣.

Comparison of ceramide synthases

| Ceramide synthase |

mRNA tissue expression |

Fatty acid substrate |

Pathologies associated with increased ceramide synthase activity |

|---|---|---|---|

| CERS1 | Brain, skeletal muscle | C18:0 | Skeletal muscle insulin resistance |

| CERS2 | Heart, liver, lungs, ubiquitous | C20:0 | Unknown |

| C22:0 | Cardiac mitochondrial dysfunction | ||

| C24:0 | Neutral/benign | ||

| C24:1 | Cardiac mitochondrial dysfunction | ||

| C26:0 | Unknown | ||

| CERS3 | Skin, testes | ≥C26:0 | Farber disease biomarker |

| CERS4 | Heart, lungs | C18:0 | Unknown |

| C20:0 | Lung cancer, heart failure | ||

| CERS5 | Heart, lungs, kidneys, ubiquitous | C14:0 | Unknown |

| C16:0 | Heart failure, apoptosis | ||

| CERS6 | Brain, adipose, liver, ubiquitous | C14:0 | Unknown |

| C16:0 | Heart failure, apoptosis, adipose tissue dysfunction, liver insulin resistance and liver fibrosis |

The final reaction in the ceramide biosynthesis cascade requires dihydroceramide desaturases (DES1 and DES2), which introduce an important double bond into the sphingoid backbone of the dihydroceramides to produce the ceramides48,49. DES1 is the major enzyme in most tissues, including those in the cardiovascular system, whereas DES2 is expressed predominantly in the skin, kidneys and intestines50.

The endoplasmic reticulum-derived ceramides can be transported to the Golgi apparatus, where they are converted into complex sphingolipids, including sphingomyelins, glucosylceramides and gangliosides. This step is facilitated by ceramide transport proteins, such as CERT1, which selectively direct ceramides to the sphingomyelin synthases51,52.

Ceramides can also be deacylated by a family of ceramidases, which liberate a fatty acid and release the sphingosine backbone. Sphingosine can be further processed by sphingosine kinases to produce S1P, which is mainly synthesized in red blood cells and the vascular endothelium53. Sphingosine can be converted back into ceramide by the aforementioned CERS enzymes. The complex sphingolipids (such as sphingomyelin) can be catabolized to regenerate ceramides during stress by sphingomyelinases54.

Ceramide and S1P have potent but opposing regulatory roles in numerous cell types55; Spiegel and colleagues first noted that the balance of ceramide to S1P functions as a cellular rheostat to dynamically regulate apoptosis versus growth, respectively, in human pro-myelocytic cell lines56. This dynamic regulation is also apparent in vascular endothelial cells (ECs), where ceramides block vasodilatation and exacerbate the risk of cardiovascular disease29,30,57,58, whereas S1P promotes vasodilatation and is atheroprotective59-61. Activation of adiponectin receptors tunes this rheostat, because these receptors increase the deacylation of ceramide and subsequent generation of S1P in numerous tissues62. This outcome is achieved because of the intrinsic ceramidase activity of the adiponectin receptors63,64. In total, >1,600 sphingolipids have been curated by the LIPIDMAPS consortium, and >4,800 are predicted to exist on the basis of computational modelling65.

Ceramides in the vascular endothelium

Blood vessel reactivity

The endothelium that lines the interior walls of arteries, veins and capillaries consists of ECs that attach to the basal lamina, structurally building the intima in blood vessels. The ECs are responsible for maintaining vascular homeostasis by sensing haemodynamic changes, such as shear stress and blood-borne substances (for example, hormones)66. In healthy conditions, ECs control the balance between vasorelaxation and vasoconstriction, anti-inflammation and pro-inflammation, and antioxidative and pro-oxidative stress by carefully titrating the synthesis of endothelium-derived relaxing and contracting factors. By far the most studied of these factors is nitric oxide (NO), which is released luminally and abluminally after its generation by endothelial NO synthase (eNOS; also known as NOS3)67. In many individuals with metabolic syndrome, ECs produce less NO in response to various stimuli (such as acetylcholine, bradykinin and EC shear stress)68. This phenomenon is observed in patients with hypertension or atherosclerosis and is an important feature of metabolic syndrome69,70.

Elevations in circulating lipid levels lead to the build-up of fatty deposits within the blood vessel lumen and the ectopic formation of ceramides within ECs (FIG. 2). EC-derived ceramides are potent regulators of vascular tone. In small coronary arteries from mice in vitro or in human cultured ECs, administration of ceramide analogues impairs EC-dependent vasorelaxation71, exacerbates vasoconstriction72 and decreases NO production73. Of note, short-chain ceramide analogues are not natural ceramides, but are rapidly deacylated and recycled into long-chain ceramides74. Alternative experimental interventions that also increase endogenous ceramide production in cells or tissues (such as by incubating ECs or isolated vessels with palmitate) recapitulate the effects of C2-ceramide administration by decreasing eNOS phosphorylation, eNOS activity and NO production29,30. Convincingly, inhibition of ceramide biosynthesis with the use of pharmacological agents (such as myriocin) or genetic modification (such as Des1 heterozygous knockout) restores eNOS activity, NO production and EC-dependent vasodilatation in these palmitate-treated samples as well as in mouse and rat models of obesity or hyperlipidaemia29,30,75. These studies indicate that endogenous ceramides contribute to the EC-dependent, NO-mediated arterial dysfunction that underlies cardiovascular disease.

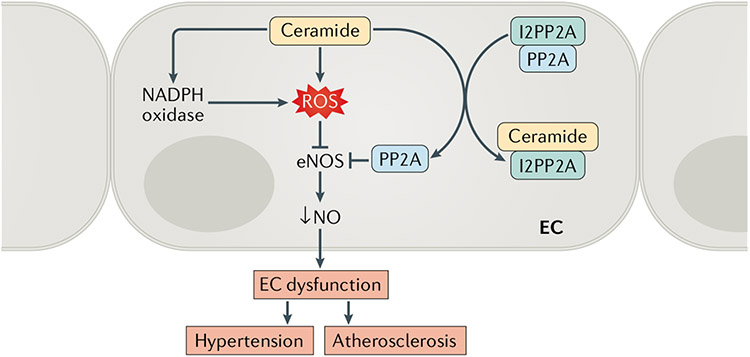

Fig. 2 ∣. Ceramide-induced endothelial cell dysfunction.

Endothelial cell (EC) dysfunction is an impairment of the vascular endothelium to regulate vascular homeostasis, mainly owing to the loss of nitric oxide (NO) bioavailability. Ceramides have been shown to decrease NO production by increasing the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and by activating protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A). The latter effect is as a result of the capacity of ceramides to dissociate the inhibitor 2 of PP2A (I2PP2A) from the PP2A, liberating the enzyme to act on cellular substrates, including endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS).

The enzymatic activity of eNOS is governed in large part by the phosphorylation of two residues: Thr495 and Ser1177. Phosphorylation of Ser1177 activates the enzyme, whereas phosphorylation of Thr495 is inhibitory76. Ceramide activates protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A), which dephosphorylates Ser1177 to diminish eNOS activity29,30,77. In vascular ECs, ceramide regulates PP2A by disrupting its interaction with inhibitor 2 of PP2A (I2PP2A), liberating PP2A from this repressive factor and increasing its access to various substrates58,78. This sequence of events leads to an increased association between PP2A and eNOS and a concomitant dissociation of eNOS from the activating kinase complex AKT–HSP90 (REFS29,30). Blocking PP2A activity ameliorates high-fat-induced or ceramide-induced endothelial dysfunction and hypertension in animal models29,30.

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) produced by NADPH oxidase also influence eNOS activity58,79. NADPH oxidase levels are elevated in animal models of hypertension, diabetes or atherosclerosis, leading to higher levels of ROS that contribute to EC-dependent vascular dysfunction80-82. Early in vitro studies found that the administration of ceramide analogues elevates ROS production, perhaps owing to NADPH oxidase activation, in animal and human ECs71,73. Moreover, NADPH oxidase inhibitors attenuated the ceramide-induced impairment of EC-dependent vasodilatation in bovine small coronary arteries in vitro71. A similar study found that overexpression of CuZn superoxide dismutase, which scavenges ROS, prevents ceramide-driven impairment of EC-dependent vasodilatation83. Curiously, our work has shown that ceramides promote the generation of superoxide anion, but several superoxide scavengers are unable to prevent ceramide actions on eNOS or NO in vitro29,30.

Multiple studies have also demonstrated that ceramides induce the production of ROS by disrupting the mitochondrial electron transport chain or induce apoptosis by altering the permeability of the mitochondrial outer membrane84. These mitochondrial effects of ceramides might also be relevant to EC survival, particularly in response to the inflammatory cytokine tumour necrosis factor (TNF). TNF increases the endogenous ceramide content of bovine and human ECs in vitro by activating sphingomyelinase or by stimulating de novo synthesis85,86. Inhibition of ceramide biosynthesis with the use of fumonisin B1, an inhibitor of ceramide synthases, protects bovine cultured cerebral artery ECs from TNF-induced or cycloheximide-induced cell death86. A summary of these cellular mechanisms is shown in TABLE 2.

Table 2 ∣.

Potential contributors to ceramide-induced vascular dysfunction

| Factor | Influence of ceramides | Effects | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|

| NADPH oxidase | Activation | ↑ROS, ↓eNOS, ↓NO | 71,73,79 |

| ROS | Increase | ↓eNOS, ↓NO | 81,82,178 |

| I2PP2A | Inhibition | ↑PP2A, ↓AKT–HSP90 complex, ↓eNOS, ↓NO | 29,73,77 |

AKT, RACα serine/threonine-protein kinase; eNOS, endothelial nitric oxide synthase; HSP90, heat shock protein 90; I2PP2A, inhibitor 2 of protein phosphatase 2A; NO, nitric oxide; PP2A, protein phosphatase 2A; ROS, reactive oxygen species.

Atherosclerosis

Atherosclerosis is a leading cause of death worldwide and the pathological basis of many cardiovascular disorders. The mechanisms of atherosclerosis progression have not been fully elucidated, but initially involve lipoprotein retention in the vascular intima. Entry of lipoproteins into the intima is associated with various factors, including lipoprotein size, charge and composition. The accumulated lipoproteins mainly consist of LDLs, which have a high affinity for proteoglycans, leading to increasing residence time in the intima87. When lipoproteins aggregate in the intima, ECs recruit monocytes, resulting in monocyte differentiation into macrophages and the formation of foam cells88. During atherosclerosis progression, ECs generate a large amount of ROS and limit NO bioavailability, which can exacerbate inflammatory responses and reduce EC-dependent vasodilatation.

Studies with large clinical cohorts reveal that serum ceramide levels are strong predictors of coronary artery disease7,11,15,17,89,90. Serum ceramide levels also predict atherosclerotic plaque instability16 and detrimental outcomes of coronary artery disease, including death15,91. Ceramides also accumulate in atherosclerotic plaques, where they have been implicated in the onset of lipoprotein aggregation92,93. Several studies have shown that ceramides have causal roles in atherosclerotic plaque formation, because inhibiting de novo ceramide synthesis alleviates lipid-induced atherogenic processes. For example, administration of the SPT inhibitor myriocin decreased plasma sphingolipid concentrations, including those of ceramide, and atherosclerotic lesion size in the aorta of atherosclerosis-prone Apoe−/− mice94-97. Similar protective effects are observed in Sptlc1 haplo-insufficient mice98. Treatment with myriocin not only is beneficial in reducing atherosclerosis but also improves insulin sensitivity and resolves hepatic steatosis in animal models25,99,100. However, regulating SPT activity by knocking out the gene or administering myriocin influences the production of nearly all sphingolipids; therefore, further work is required to differentiate between the specific effects of ceramide and those of complex sphingolipids (such as glucosylceramides or sphingomyelins).

Another approach to lowering ceramide levels is to target the enzyme DES1, which converts dihydroceramide to ceramide (FIG. 1). Inhibition of DES1 with a chemical inhibitor (fenretinide) or genetic modification protects mice from insulin resistance, hepatic steatosis and/or vascular dysfunction29,101-103. Fenretinide also prevents dyslipidaemia and hepatic steatosis in mice102,104. Surprisingly, treatment with fenretinide worsens atherosclerosis in mice, although it has been suggested that this effect is driven by the retinoid actions of the drug and is, therefore, independent of its effects on DES1 (REF.105). Consistent with this interpretation, whole-body deletion of Des1 in mice does not increase inflammation or promote splenomegaly, which were major features observed in fenretinide-treated animals101. Additional pharmacological and genetic studies are needed to determine the effects of DES1 inhibition on atherosclerotic plaque formation.

Jiang and colleagues investigated whether sphingomyelins, rather than ceramides, drive atherosclerosis106. The sphingomyelins are also independent markers of cardiovascular disease106. Jiang and co-workers explored whether inhibition of sphingomyelin production by sphingomyelin synthases (SMS1 and SMS2) might be a therapeutic approach to treat atherosclerosis. In mouse models, adenoviral-mediated overexpression of Sms1 and Sms2 increased plasma sphingomyelin levels and worsened atherosclerosis107-109. By contrast, SMS2 deficiency in mice attenuated atherosclerotic lesion formation and inflammatory responses110-112. Interestingly, inhibiting SMS1 elicited abnormalities, including metabolic dysfunction and inflammation113,114.

The studies described above demonstrate that lowering ceramide synthesis using pharmacological inhibitors or genetic engineering alleviates vascular dysfunction and atherosclerosis in animal models. Although many mechanisms have been identified, the full spectrum of events by which ceramides promote atherosclerotic plaque formation remains elusive. Nonetheless, the studies present exciting possibilities that lowering plasma ceramide levels could be an effective means of improving vascular health.

Role of ceramides in the heart

Heart failure

Despite the successes of certain glucose-lowering therapies for the management of diabetes and delaying or preventing cardiac complications, HF remains the major cause of death in patients with diabetes115. HF includes two major subtypes: HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF), which encompasses ischaemic and non-ischaemic HF and is characterized by dilated ventricles and systolic dysfunction, and HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), which is characterized by stiffened ventricles and diastolic dysfunction (FIG. 3). Through the 1990s, HFrEF accounted for 75% of all HF diagnoses but now accounts for only about 50%116. This change is because the incidence of HFpEF is increasing at alarming and accelerating rates117,118.

Fig. 3 ∣. Types of heart failure and the contribution of ceramides.

Heart failure (HF) with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) can be caused by ischaemic injury, such as myocardial infarction, and is characterized by dilated ventricles, apoptosis and replacement fibrosis. Ceramides can contribute to the development of atherosclerosis and ischaemic injury and also to cardiomyocyte apoptosis after myocardial infarction has occurred. HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) is caused by chronic systemic inflammation, often in the context of diabetes mellitus, hypertension, obesity and lipotoxicity, and is characterized by constricted ventricles and interstitial fibrosis. Ceramides are also associated with risk factors for the development of HFpEF and non-ischaemic HFrEF.

Although HFrEF and HFpEF have shared risk factors (such as diabetes), these subtypes of HF are distinguished by subtle cellular and molecular differences. HFrEF is often a result of ischaemic injury or chronic β-adrenergic signalling and is followed by cardiomyocyte apoptosis, inflammation and subsequent fibrotic repair; these cellular processes disrupt contractility of the left ventricle119. By contrast, HFpEF is preceded by chronic morbidities such as obesity, dyslipidaemia and hypertension and is caused by cardiac fibrosis in the absence of severe apoptosis, resulting in cardiac hypertrophy and left ventricular diastolic dysfunction119. Ceramides seem to be relevant to both of these conditions.

As noted previously, circulating ceramide levels are strong biomarkers of long-term cardiovascular outcomes13-16. Studies with heart biopsy samples indicate that ceramides, and the ceramide biosynthesis enzymes, also accumulate in the failing myocardium28. Patients with severe HFrEF often undergo surgery to receive a left ventricular assist device, which improves cardiac function and metabolism120-122. Placement of a left ventricular assist device reduces the levels of ceramides of nearly all chain lengths in the myocardium28. Curiously, women with HFpEF who underwent gastric bypass surgery had improved plasma ceramide profiles and cardiac function but no changes in myocardial ceramide content20. Therefore, ceramides are likely to influence cardiac function by mechanisms that are intrinsic (that is, intramyocardial) and extrinsic (such as via blood pressure regulation or dyslipidaemia) to the heart.

Targeting ectopic lipid accumulation might be a powerful approach to combating heart disease. In the CORONA trial123, statin therapy was associated with a 15–20% reduction in the risk of hospitalization for HF. Statins lower the circulating levels of many lipoprotein-bound lipids, including ceramides17. Therefore, the question arises as to whether ceramide-focused interventions might have additional protective effects. To specifically assess the role of lipids in the heart, Goldberg and colleagues studied genetically engineered mouse models of dilated lipotoxic cardiomyopathy27. The researchers generated mice with cardiac-specific overexpression of the gene encoding glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored human lipoprotein lipase (LplGPI), which liberates fatty acids from circulating lipoproteins and facilitates their incorporation into neighbouring tissue. LplGPI overexpression resulted in elevated cardiac ceramide levels and impaired function of the heart27. The intervention also downregulated the levels of glucose transporter 4 and upregulated markers of HF, such as atrial natriuretic peptide, B-type natriuretic peptide and pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase isoform 4. Administration of the SPT inhibitor myriocin to LplGPI-overexpressing mice improved cardiac systolic function and increased survival rates27.

Schulze and colleagues further investigated the role of ceramides in a mouse model of ischaemia-induced HF28. The researchers induced a myocardial infarction in mice by ligating the left anterior descending coronary artery, producing left ventricular dysfunction and progressive cardiac remodelling and dilatation28. Myriocin administration reduced ceramide levels in the heart and reduced ventricular remodelling and fibrosis in this model of HFrEF28. Similar results were found in Sptlc2+/− mice, which are deficient in the SPTLC2 subunit28. These data identify ceramides as a cardiotoxin that impairs heart function and suggest that ceramide-lowering interventions could have cardioprotective actions.

An alternative approach to lowering ceramide levels in the heart and plasma is to promote ceramide degradation (for example, via ceramidases). Adiponectin is a fat-derived hormone that promotes weight loss, increases insulin sensitivity, decreases inflammation and inhibits apoptosis124. Therefore, this adipokine has antidiabetic and cardioprotective actions. Adiponectin increases the ceramidase activity that is intrinsic to its two receptors, AdipoR1 and AdipoR2 (REFS62,64). Inhibiting acid ceramidase activity in mice after myocardial infarction worsened cardiac function, whereas increasing acid ceramidase activity improved cardiac function125, indicating the important role that ceramidase reactions have in HFrEF.

In addition to degrading ceramides, activating the ceramidase step leads to increased production of S1P, which might have cardioprotective actions. S1P signals through one of five receptor family members126. Studies using knockout mice implicate the S1P2 and S1P3 receptors as being potent mediators of cardioprotection after ischaemia–reperfusion injury, with a similar effect reported in human myocardial tissue126-130. An adiponectin–S1P axis is protective against cardiomyocyte cell death131,132.

Ceramide mechanisms that contribute to HF

One mechanism linking ceramides to impaired cardiomyocyte function relates to their actions in mitochondria, where they can impair energetics and ultimately induce apoptosis84 (FIG. 4). Accumulation of ceramides in the inner mitochondrial membrane disrupts electron transport chain activity, impairing respiratory capacity43-47-133-135. When ceramides accumulate in the outer mitochondrial membrane, they increase permeability to cytochrome c and initiate intrinsic apoptosis pathways136. Although many of the studies to dissect the mechanisms of these actions have been performed in other cell types, the actions seems to be highly relevant to cardiomyocytes137-141. For example, ceramide analogues are sufficient to induce apoptosis in cardiomyocytes138. Researchers have also confirmed that endogenous ceramides, induced by palmitate exposure, can drive apoptosis in this cell type139-141. Moreover, overexpressing SPTLC1 and/or SPTLC2 in AC16 human cardiomyocytes induces ceramide accumulation, impairs mitochondrial respiration and induces apoptosis28. Similarly, overexpression of Cers2 in mice elicited a similar spectrum of effects in cardiomyocytes142. Overexpression of Cers2 also increased ROS production, an effect that was exacerbated by delivering an excess of mitochondrial substrates and inhibited by blocking sphingolipid synthesis142. By contrast, inhibiting sphingolipid synthesis had no effect on superoxide-induced ROS, placing ceramide as an obligatory upstream mediator of ROS generation142.

Fig. 4 ∣. Mechanisms linking ceramides to heart failure.

Ceramides produced either de novo or by sphingomyelin (SM) hydrolysis by sphingomyelinase (SMase) have been implicated in several actions in cardiomyocytes that could contribute to heart failure. Through actions in mitochondrial membranes, ceramides alter cellular energetics, induce reactive oxygen species (ROS) formation and promote cytochrome c release to initiate apoptosis. Some researchers have speculated that upregulation of anti-apoptotic proteins, such as B cell lymphoma 2 (BCL-2), could minimize this action in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF). Ceramides have also been implicated in profibrotic pathways, such as the activation of cAMP-responsive elementbinding protein 3-like protein 1 (CREB3L1) to promote collagen deposition. FAT, fatty acid translocase (also known as platelet glycoprotein 4); HFrEF, heart failure with reduced ejection fraction; TNF, tumour necrosis factor.

Although intramyocardial levels of ceramides are high in animal models of HFpEF143, this form of HF occurs in the absence of severe apoptosis144. This observation might be explained by increased expression of anti-apoptotic proteins, such as B cell lymphoma 2 (BCL-2). Indeed, Dong and colleagues created a model of HFpEF that was associated with an increased expression of Bcl2 (REF.145). Moreover, studies in other cell and tissue types have shown that BCL-2 family members prevent ceramide-dependent apoptosis146-148. Additional work is warranted to understand the protection from apoptosis that occurs in the HFpEF syndrome.

An alternative mechanism linking sphingolipids to HF involves their regulation of autophagy, a highly coordinated process that prevents the accumulation of damaged molecules within the cell149. In an in vitro model of diabetic cardiomyopathy, myristate (C14:0) but not palmitate (C16:0) induced CERS6-dependent increases in autophagy that contributed to cardiomyocyte hypertrophy42.

Ceramides might also affect the heart through actions in other cell types. ECs make up the majority of the non-cardiomyocyte cells in the myocardium, and ECs are dysfunctional in both HFrEF and HFpEF. In particular, NO bioavailability is greatly attenuated in HFpEF150,151. Our studies suggest that, in patients with HFrEF, the placement of a left ventricular assist device improves coronary artery EC function152 and reduces serum ceramide levels (S.A.S., W.L.H., unpublished observations). As described previously, ceramides have important roles in ECs that might explain the attenuation of NO production in HFpEF.

HF is also accompanied by an inflammatory response that is characterized by the infiltration of macrophages and neutrophils into the myocardium151,153. The inflammatory cascade is another important step in the onset and progression of diastolic dysfunction. Ceramides contribute to these inflammatory processes, both as upstream regulators of cytokine production and as downstream effectors that mediate cytokine-induced stress responses154. Lowering ceramide levels in the heart (such as by overexpressing Asah1, encoding acid ceramidase) reduces macrophage infiltration in mouse models of myocardial infarction125.

Lastly, ceramides have emerged as potential inducers of fibrosis4, independent of their actions on preceding apoptosis events. For example, ceramides stimulate proteolytic processing of cAMP-responsive element-binding protein 3-like protein 1 (CREB3L1)155,156, a transcription factor that induces collagen production. An intricate mechanism has been described in which ceramides invert the topology of the inhibitory protein transmembrane 4 L6 family member 20 (TM4SF20); this inversion removes the inhibitory signal and allows CREB3L1 exposure to site-1 proteases155,156. Although these actions have not been explored in the heart, these and other mechanisms might explain how ceramides contribute to the fibrotic response that drives HFpEF.

Importance of ceramide chain length in cardiac dysfunction.

In tissues such as the liver and adipose tissue, long-chain C16:0 ceramide is deleterious, whereas very-long-chain ceramides (such as C24:0) are considered to be benign43,45-47,157-159. The C16-ceramides are thought to form unique platforms in membranes that initiate stress responses (for example, impaired mitochondrial respiration and apoptosis), whereas the very-long-chain ceramides lack these attributes. Consistent with this hypothesis, in the clinical CERT1 score, high levels of C16:0 ceramides increase the score (indicating a heightened risk of cardiac events), whereas elevated C24:0 levels decrease the score (indicating a diminished risk)5. Moreover, in humans with severe HFrEF, who have increased ceramide levels in the myocardium and plasma28, unloading the heart with the use of a left ventricular assist device improves heart function and restores physiological healthy C24:0 to C16:0 ratios21,160.

Notwithstanding the data above, studies in mice and cells have produced ambiguous results on which ceramide species are damaging to the heart. To test the idea that C16-ceramides are pathogenic in the heart, mice lacking CERS5, which together with CERS6 makes the C16-ceramides, were studied42. The researchers induced cardiomyopathy by feeding the mice a milk-fat-based diet and found that ablation of Cers5 negated certain elements of the condition, including cardiac autophagy and hypertrophy42. Surprisingly, however, the investigators concluded that C14-ceramides derived from myristate and produced by CERS5 — rather than the canonical C16-ceramides that are produced from palmitate and have been implicated in tissue dysfunction — were the damaging species. In a later study, the researchers evaluated the consequences of overexpressing Cers2 (encoding CERS2, which produces very-long-chain ceramides) in cardiomyocytes142. In these cell culture experiments, Cers2 overexpression selectively increased the levels of certain very-long-chain ceramides and induced mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress and cell death142. This result was surprising because studies in other tissues and cell types have indicated that these ceramide actions require CERS6 and the C16 acyl chain, whereas longer-chain ceramides are unable to alter mitochondrial function43,45-47,159.

Additional evidence suggests that sphingolipids with unusual sphingoid bases, such as those derived from the condensation of myristate (rather than palmitate) with serine, are important drivers of heart dysfunction161. The capacity of the SPT complex to use myristate as a substrate is influenced by the presence of the SPTLC3 subunit, which is abundant in rat cultured cardiomyocytes and mouse hearts161. Moreover, the d16-base sphingolipids that are derived from myristate comprised 30% of cardiomyocyte sphingolipids161. Lastly, these d16 sphingolipids were found to promote cell death161. These findings raise the interesting possibility that alternative sphingolipids might contribute to cardiomyocyte dysfunction.

Ceramide-related therapeutic targets

Since the early 1900s, plasma LDL-cholesterol levels have been considered to be the best biomarker for predicting cardiovascular events. This discovery triggered the development of LDL-cholesterol-lowering therapeutics, including statins, ezetimibe, proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) inhibitors and fenofibrates. Studies with these drugs have demonstrated that reductions in LDL-cholesterol levels effectively decrease the risk of cardiovascular events162,163. Although plasma ceramide levels have been identified as a strong predictor of cardiovascular disease, the effects of existing lipid-modifying drugs on sphingolipids, especially ceramides, have not been studied extensively. Treatment with either simvastatin or rosuvastatin can lower plasma ceramide levels by 20–30% compared with patients treated with ezetimibe or placebo, respectively17,164. Treatment with a PCSK9 inhibitor for 2–12 months was shown to reduce the plasma levels of several ceramides (~30% decrease), together with the expected lowering of plasma LDL-cholesterol levels165. Further studies are required to determine whether reductions in plasma ceramide levels make an important contribution to the effects of these existing drugs.

As noted previously, circulating ceramide levels are elevated in individuals with obesity, diabetes, cancer, hepatic steatosis, hypertension, HF or atherosclerosis. The diagnostic power of plasma ceramide levels seems to be similar to that of plasma LDL-cholesterol levels, to the extent that clinics have introduced diagnostic tests measuring plasma ceramide levels, owing to their utility in predicting insulin resistance, the severity of coronary artery disease, the incidence of major adverse cardiac events and death. In addition, the aforementioned studies in mice further indicate that ceramides have causal roles in these pathologies, suggesting that therapeutic strategies that lower plasma ceramide levels could be a good approach to combating these obesity-related disorders.

SPT, the initial enzyme in the de novo sphingolipid synthesis pathway, was the first enzyme to be seriously considered as a therapeutic target to lower plasma ceramide levels and treat cardiometabolic disease. Inhibiting the SPT enzyme decreases the levels of all sphingolipid species, including ceramides, sphinganine, dihydroceramides and sphingomyelins, in a wide variety of tissues. In mice, treatment with the irreversible SPT inhibitor myriocin prevents insulin resistance and diabetes, atherosclerosis, hypertension and HF25-29,166-168. Heterozygous Sptlc1-knockout mice have been shown to be protected from dyslipidaemia, atherosclerosis and HFrEF28,98. Unfortunately, attempts by pharmaceutical companies to generate safe SPT inhibitors have so far failed, largely owing to toxicity to the gut169. This toxicity is likely to be an on-target drug effect, because knockout mice lacking SPTLC2 subunits die shortly after gene ablation owing to disruption of the gut architecture170,171.

Other targets in the de novo ceramide biosynthesis pathway have also received attention as potential therapeutic targets. CERS6 has received considerable attention, largely because its ablation confers protection from insulin resistance and dyslipidaemia and improves mitochondrial function43,45,159. Studies on this target are ongoing.

DES1 catalyses the last step in the de novo ceramide biosynthesis pathway by inserting a crucial double bond into the backbone of dihydroceramides to produce the deleterious ceramides. Fenretinide, a retinoid that additionally has inhibitory actions against DES1, is insulin-sensitizing in humans and in obese mice102,104,172-174. Fenretinide also reduces blood pressure in hypertensive rats by attenuating inflammation175. However, fenretinide administration has been shown to worsen atherosclerosis, although it has been suggested that this effect is driven by the retinoid actions of the drug and is therefore independent of its effects on DES1 (REF.105). Future work is needed to determine the effects of DES1 inhibition on atherosclerotic plaque formation. Studies in mice further support the efficacy of this therapeutic strategy. Heterozygous Des1-knockout mice are protected from diet-induced vascular dysfunction29. Inducible depletion of DES1 from mice protects against glucose intolerance, insulin resistance and hepatic steatosis101. Therefore, ablation of Des1 ameliorates many of the metabolic disorders that increase the risk of heart disease101, but this approach has not yet been tested as a means of improving heart function.

Lastly, one might consider approaches to activate adiponectin receptors to catalyse ceramide deacylation. Indeed, we have previously found that adiponectin, by reducing cardiac ceramide levels, ameliorates HF driven by caspase activation in so-called HEART-ATTAC mice62. AdipoRon is a selective, orally active agonist of adiponectin receptors. Intraperitoneal delivery of AdipoRon in mice can rapidly lower ceramide levels in adiponectin-responsive tissues63. Subsequent in vitro studies in immortalized H9C2 rat cardiomyocytes, mouse primary cardiomyocytes and human vascular smooth muscle cells supported the utility of AdipoRon as a tool to combat ceramide-induced lipotoxicity and improve cardiometabolic health176,177.

Conclusions

Lipid-induced vascular and cardiac dysfunction are important components of the major comorbidities of diabetes, obesity and dyslipidaemia that reduce the quality and length of life. Among the various lipid species that accumulate in these diseased tissues, ceramides are highly pathogenic, because they elicit many of the tissue defects that underlie cardiovascular pathologies. Therapeutic strategies to lower plasma, vascular and cardiac ceramide levels hold enormous promise for treating a wide variety of cardiometabolic disorders, including hypertension, atherosclerosis, diabetes and HF. More work is needed in this promising area to understand the precise mechanisms controlling ceramide production and action and to identify therapeutic means of safely lowering ceramide levels to improve health.

Key points.

Ceramides have been shown to accumulate in many tissues, including blood vessels and the heart, in individuals with cardiovascular disease (such as hypertension, heart failure and atherosclerosis).

Serum ceramide levels are measured clinically as prognostic indicators of major adverse cardiovascular events.

Inhibiting ceramide biosynthesis in mice and rats prevents the development of hypertension, atherosclerosis, diabetes mellitus and heart failure.

Ceramides have pleiotropic actions that are relevant to metabolic disease, including inhibiting nitric oxide synthase, decreasing insulin sensitivity, altering mitochondrial bioenergetics, and inducing apoptosis and fibrosis.

Several enzymes that control ceramide production or metabolism have emerged as attractive therapeutic targets for treating a wide range of cardiometabolic pathologies.

Footnotes

Competing interests

S.A.S. is a consultant, co-founder and shareholder of Centaurus Therapeutics. The other authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Hales CM, Carroll MD, Fryar CD & Ogden CL Prevalence of obesity and severe obesity among adults: United States, 2017–2018. NCHS Data Brief, no. 360 (National Center for Health Statistics, 2020). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Summers SA, Chaurasia B & Holland WL Metabolic messengers: ceramides. Nat. Metab 1, 1051–1058 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Russo SB, Ross JS & Cowart LA in Sphingolipids in Disease. Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology vol. 216 (eds Gulbins E & Petrache I) 373–401 (Springer, 2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Poss AM & Summers SA Too much of a good thing? An evolutionary theory to explain the role of ceramides in NAFLD. Front. Endocrinol 11, 505 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hilvo M, Vasile VC, Donato LJ, Hurme R & Laaksonen R Ceramides and ceramide scores: clinical applications for cardiometabolic risk stratification. Front. Endocrinol 11, 570628 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hilvo M et al. Prediction of residual risk by ceramide-phospholipid score in patients with stable coronary heart disease on optimal medical therapy. J. Am. Heart Assoc 9, e015258 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Poss AM et al. Machine learning reveals serum sphingolipids as cholesterol-independent biomarkers of coronary artery disease. J. Clin. Invest 130, 1363–1376 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Poss AM, Holland WL & Summers SA Risky lipids: refining the ceramide score that measures cardiovascular health. Eur. Heart J 41, 381–382 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mantovani A et al. Association between increased plasma ceramides and chronic kidney disease in patients with and without ischemic heart disease. Diabetes Metab. 47, 101152 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mantovani A & Dugo C Ceramides and risk of major adverse cardiovascular events: a meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. J. Clin. Lipidol 14, 176–185 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mantovani A et al. Associations between specific plasma ceramides and severity of coronary-artery stenosis assessed by coronary angiography. Diabetes Metab. 46, 150–157 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mantovani A et al. Association between specific plasma ceramides and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein levels in postmenopausal women with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Metab. 46, 326–330 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anroedh S et al. Plasma concentrations of molecular lipid species predict long-term clinical outcome in coronary artery disease patients. J. Lipid Res 59, 1729–1737 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Havulinna AS et al. Circulating ceramides predict cardiovascular outcomes in the population-based FINRISK 2002 cohort. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol 36, 2424–2430 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Laaksonen R et al. Plasma ceramides predict cardiovascular death in patients with stable coronary artery disease and acute coronary syndromes beyond LDL-cholesterol. Eur. Heart J 37, 1967–1976 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cheng JM et al. Plasma concentrations of molecular lipid species in relation to coronary plaque characteristics and cardiovascular outcome: results of the ATHEROREMO-IVUS study. Atherosclerosis 243, 560–566 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tarasov K et al. Molecular lipids identify cardiovascular risk and are efficiently lowered by simvastatin and PCSK9 deficiency. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab 99, E45–E52 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peterson LR et al. Alterations in plasma triglycerides and ceramides: links with cardiac function in humans with type 2 diabetes. J. Lipid Res 61, 1065–1074 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peterson LR et al. Ceramide remodeling and risk of cardiovascular events and mortality. J. Am. Heart. Assoc 7, e007931 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mikhalkova D et al. Bariatric surgery-induced cardiac and lipidomic changes in obesity-related heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Obesity 26, 284–290 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lemaitre RN et al. Plasma ceramides and sphingomyelins in relation to heart failure risk. Circ. Heart Fail 12, e005708 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lemaitre RN et al. Circulating sphingolipids, insulin, HOMA-IR, and HOMA-B: the Strong Heart Family Study. Diabetes 67, 1663–1672 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cresci S et al. Genetic architecture of circulating very-long-chain (C24:0 and C22:0) ceramide concentrations. J. Lipid Atheroscler 9, 172–183 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Javaheri A, Allegood JC, Cowart LA & Chirinos JA Circulating ceramide 16:0 in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol 75, 2273–2275 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Holland WL et al. Inhibition of ceramide synthesis ameliorates glucocorticoid-, saturated-fat-, and obesity-induced insulin resistance. Cell Metab. 5, 167–179 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hojjati MR et al. Effect of myriocin on plasma sphingolipid metabolism and atherosclerosis in apoE-deficient mice. J. Biol. Chem 280, 10284–10289 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Park TS et al. Ceramide is a cardiotoxin in lipotoxic cardiomyopathy. J. Lipid Res 49, 2101–2112 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ji R et al. Increased de novo ceramide synthesis and accumulation in failing myocardium. JCI Insight 2, e82922 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang QJ et al. Ceramide mediates vascular dysfunction in diet-induced obesity by PP2A-mediated dephosphorylation of the eNOS-Akt complex. Diabetes 61, 1848–1859 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bharath LP et al. Ceramide-initiated protein phosphatase 2A activation contributes to arterial dysfunction in vivo. Diabetes 64, 3914–3926 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Merrill AH Jr. et al. Sphingolipids–the enigmatic lipid class: biochemistry, physiology, and pathophysiology. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol 142, 208–225 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hannun YA & Obeid LM Principles of bioactive lipid signalling: lessons from sphingolipids. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 9, 139–150 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nikolova-Karakashian MN & Rozenova KA Ceramide in stress response. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol 688, 86–108 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Obeid LM & Hannun YA Ceramide, stress, and a “LAG” in aging. Sci. Aging Knowl. Environ 2003, PE27 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hannun YA & Obeid LM The ceramide-centric universe of lipid-mediated cell regulation: stress encounters of the lipid kind. J. Biol. Chem 277, 25847–25850 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Merrill AH Jr. De novo sphingolipid biosynthesis: a necessary, but dangerous, pathway. J. Biol. Chem 277, 25843–25846 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Han G et al. Identification of small subunits of mammalian serine palmitoyltransferase that confer distinct acyl-CoA substrate specificities. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 8186–8191 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hornemann T et al. The SPTLC3 subunit of serine palmitoyltransferase generates short chain sphingoid bases. J. Biol. Chem 284, 26322–26330 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zelnik ID, Rozman B, Rosenfeld-Gur E, Ben-Dor S & Futerman AH A stroll down the CerS lane. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol 1159, 49–63 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Laviad EL et al. Characterization of ceramide synthase 2: tissue distribution, substrate specificity, and inhibition by sphingosine 1-phosphate. J. Biol. Chem 283, 5677–5684 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Levy M & Futerman AH Mammalian ceramide synthases. IUBMB Life 62, 347–356 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Russo SB et al. Ceramide synthase 5 mediates lipid-induced autophagy and hypertrophy in cardiomyocytes. J. Clin. Invest 122, 3919–3930 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hammerschmidt P et al. CerS6-derived sphingolipids interact with Mff and promote mitochondrial fragmentation in obesity. Cell 177, 1536–1552 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Peters F et al. Ceramide synthase 4 regulates stem cell homeostasis and hair follicle cycling. J. Invest. Dermatol 135, 1501–1509 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Turpin SM et al. Obesity-induced CerS6-dependent C16:0 ceramide production promotes weight gain and glucose intolerance. Cell Metab. 20, 678–686 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Raichur S et al. The role of C16:0 ceramide in the development of obesity and type 2 diabetes: CerS6 inhibition as a novel therapeutic approach. Mol. Metab 21, 36–50 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Raichur S et al. CerS2 haploinsufficiency inhibits β-oxidation and confers susceptibility to diet-induced steatohepatitis and insulin resistance. Cell Metab. 20, 687–695 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Michel C & van Echten-Deckert G Conversion of dihydroceramide to ceramide occurs at the cytosolic face of the endoplasmic reticulum. FEBS Lett. 416, 153–155 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Michel C et al. Characterization of ceramide synthesis. A dihydroceramide desaturase introduces the 4,5-trans-double bond of sphingosine at the level of dihydroceramide. J. Biol. Chem 272, 22432–22437 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Omae F et al. DES2 protein is responsible for phytoceramide biosynthesis in the mouse small intestine. Biochem. J 379, 687–695 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hanada K, Kumagai K, Tomishige N & Yamaji T CERT-mediated trafficking of ceramide. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1791, 684–691 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kumagai K & Hanada K Structure, functions and regulation of CERT, a lipid-transfer protein for the delivery of ceramide at the ER-Golgi membrane contact sites. FEBS Lett. 593, 2366–2377 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Venkataraman K et al. Vascular endothelium as a contributor of plasma sphingosine 1-phosphate. Circ. Res 102, 669–676 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hannun YA, Luberto C & Argraves KM Enzymes of sphingolipid metabolism: from modular to integrative signaling. Biochemistry 40, 4893–4903 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Newton J, Lima S, Maceyka M & Spiegel S Revisiting the sphingolipid rheostat: evolving concepts in cancer therapy. Exp. Cell Res 333, 195–200 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cuvillier O et al. Suppression of ceramide-mediated programmed cell death by sphingosine-1-phosphate. Nature 381, 800–803 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wende AR, Symons JD & Abel ED Mechanisms of lipotoxicity in the cardiovascular system. Curr. Hypertens. Rep 14, 517–531 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Symons JD & Abel ED Lipotoxicity contributes to endothelial dysfunction: a focus on the contribution from ceramide. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord 14, 59–68 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dantas AP, Igarashi J & Michel T Sphingosine 1-phosphate and control of vascular tone. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol 284, H2045–H2052 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Igarashi J & Michel T Sphingosine-1-phosphate and modulation of vascular tone. Cardiovasc. Res 82, 212–220 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kennedy S, Kane KA, Pyne NJ & Pyne S Targeting sphingosine-1-phosphate signalling for cardioprotection. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol 9, 194–201 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Holland WL et al. Receptor-mediated activation of ceramidase activity initiates the pleiotropic actions of adiponectin. Nat. Med 17, 55–63 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Holland WL et al. Inducible overexpression of adiponectin receptors highlight the roles of adiponectin-induced ceramidase signaling in lipid and glucose homeostasis. Mol. Metab 6, 267–275 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Vasiliauskaite-Brooks I et al. Structural insights into adiponectin receptors suggest ceramidase activity. Nature 544, 120–123 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Merrill AH, Dennis EA, McDonald JG & Fahy E Lipidomics technologies at the end of the first decade and the beginning of the next. Adv. Nutr 4, 565–567 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kruger-Genge A, Blocki A, Franke RP & Jung F Vascular endothelial cell biology: an update. Int. J. Mol. Sci 20, 4411 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Vallance P, Collier J & Moncada S Effects of endothelium-derived nitric oxide on peripheral arteriolar tone in man. Lancet 2, 997–1000 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Triggle CR & Ding H A review of endothelial dysfunction in diabetes: a focus on the contribution of a dysfunctional eNOS. J. Am. Soc. Hypertens 4, 102–115 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ross R Atherosclerosis–an inflammatory disease. N. Engl. J. Med 340, 115–126 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Higashi Y, Kihara Y & Noma K Endothelial dysfunction and hypertension in aging. Hypertens. Res 35, 1039–1047 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zhang DX, Zou AP & Li PL Ceramide-induced activation of NADPH oxidase and endothelial dysfunction in small coronary arteries. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol 284, H605–H612 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zheng T, Li W, Wang J, Altura BT & Altura BM Sphingomyelinase and ceramide analogs induce contraction and rises in [Ca2+]i in canine cerebral vascular muscle. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol 278, H1421–H1428 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Li H et al. Dual effect of ceramide on human endothelial cells: induction of oxidative stress and transcriptional upregulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Circulation 106, 2250–2256 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ogretmen B et al. Biochemical mechanisms of the generation of endogenous long chain ceramide in response to exogenous short chain ceramide in the A549 human lung adenocarcinoma cell line. Role for endogenous ceramide in mediating the action of exogenous ceramide. J. Biol. Chem 277, 12960–12969 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Chun L et al. Inhibition of ceramide synthesis reverses endothelial dysfunction and atherosclerosis in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract 93, 77–85 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Mount PF, Kemp BE & Power DA Regulation of endothelial and myocardial NO synthesis by multi-site eNOS phosphorylation. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol 42, 271–279 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Smith AR, Visioli F, Frei B & Hagen TM Age-related changes in endothelial nitric oxide synthase phosphorylation and nitric oxide dependent vasodilation: evidence for a novel mechanism involving sphingomyelinase and ceramide-activated phosphatase 2A. Aging Cell 5, 391–400 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Oaks J & Ogretmen B Regulation of PP2A by sphingolipid metabolism and signaling. Front. Oncol 4, 388 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sukumar P et al. Nox2 NADPH oxidase has a critical role in insulin resistance-related endothelial cell dysfunction. Diabetes 62, 2130–2134 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Rajagopalan S, Meng XP, Ramasamy S, Harrison DG & Galis ZS Reactive oxygen species produced by macrophage-derived foam cells regulate the activity of vascular matrix metalloproteinases in vitro. Implications for atherosclerotic plaque stability. J. Clin. Invest 98, 2572–2579 (1996). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hink U et al. Mechanisms underlying endothelial dysfunction in diabetes mellitus. Circ. Res 88, E14–E22 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Bryk D, Olejarz W & Zapolska-Downar D The role of oxidative stress and NADPH oxidase in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Postepy Hig. Med. Dosw 71, 57–68 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Didion SP & Faraci FM Ceramide-induced impairment of endothelial function is prevented by CuZn superoxide dismutase overexpression. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol 25, 90–95 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Funai K, Summers SA & Rutter J Reign in the membrane: how common lipids govern mitochondrial function. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol 63, 162–173 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Modur V, Zimmerman GA, Prescott SM & McIntyre TM Endothelial cell inflammatory responses to tumor necrosis factor α. Ceramide-dependent and -independent mitogen-activated protein kinase cascades. J. Biol. Chem 271, 13094–13102 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Xu J et al. Involvement of de novo ceramide biosynthesis in tumor necrosis factor-α/cycloheximide-induced cerebral endothelial cell death. J. Biol. Chem 273, 16521–16526 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Camejo G, Hurt-Camejo E, Wiklund O & Bondjers G Association of apo B lipoproteins with arterial proteoglycans: pathological significance and molecular basis. Atherosclerosis 139, 205–222 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ross R Atherosclerosis is an inflammatory disease. Am. Heart J 138, S419–S420 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Hilvo M et al. Development and validation of a ceramide- and phospholipid-based cardiovascular risk estimation score for coronary artery disease patients. Eur. Heart J 41, 371–380 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Mantovani A et al. Association of plasma ceramides with myocardial perfusion in patients with coronary artery disease undergoing stress myocardial perfusion scintigraphy. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol 38, 2854–2861 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Meeusen JW et al. Plasma ceramides. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol 38, 1933–1939 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Schissel SL et al. Rabbit aorta and human atherosclerotic lesions hydrolyze the sphingomyelin of retained low-density lipoprotein. Proposed role for arterial-wall sphingomyelinase in subendothelial retention and aggregation of atherogenic lipoproteins. J. Clin. Invest 98, 1455–1464 (1996). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Edsfeldt A et al. Sphingolipids contribute to human atherosclerotic plaque inflammation. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol 36, 1132–1140 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Park TS et al. Inhibition of sphingomyelin synthesis reduces atherogenesis in apolipoprotein E-knockout mice. Circulation 110, 3465–3471 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Park TS et al. Modulation of lipoprotein metabolism by inhibition of sphingomyelin synthesis in ApoE knockout mice. Atherosclerosis 189, 264–272 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Hojjati MR, Li Z & Jiang XC Serine palmitoyl-CoA transferase (SPT) deficiency and sphingolipid levels in mice. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1737, 44–51 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Glaros EN et al. Inhibition of atherosclerosis by the serine palmitoyl transferase inhibitor myriocin is associated with reduced plasma glycosphingolipid concentration. Biochem. Pharmacol 73, 1340–1346 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Li Z et al. Serine palmitoyltransferase (SPT) deficient mice absorb less cholesterol. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1791, 297–306 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Kasumov T et al. Ceramide as a mediator of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and associated atherosclerosis. PLoS ONE 10, e0126910 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Kurek K et al. Inhibition of ceramide de novo synthesis reduces liver lipid accumulation in rats with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Liver Int. 34, 1074–1083 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Chaurasia B et al. Targeting a ceramide double bond improves insulin resistance and hepatic steatosis. Science 365, 386–392 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Bikman BT et al. Fenretinide prevents lipid-induced insulin resistance by blocking ceramide biosynthesis. J. Biol. Chem 287, 17426–17437 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Mody N & McIlroy GD The mechanisms of fenretinide-mediated anti-cancer activity and prevention of obesity and type-2 diabetes. Biochem. Pharmacol 91, 277–286 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Koh IU et al. Fenretinide ameliorates insulin resistance and fatty liver in obese mice. Biol. Pharm. Bull 35, 369–375 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Busnelli M et al. Fenretinide treatment accelerates atherosclerosis development in apoE-deficient mice in spite of beneficial metabolic effects. Br. J. Pharmacol 177, 328–345 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Jiang XC et al. Plasma sphingomyelin level as a risk factor for coronary artery disease. Arterioscler.Thromb. Vasc. Biol 20, 2614–2618 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Wang X, Dong J, Zhao Y, Li Y & Wu M Adenovirus-mediated sphingomyelin synthase 2 increases atherosclerotic lesions in ApoE KO mice. Lipids Health Dis. 10, 7 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Zhao YR, Dong JB, Li Y & Wu MP Sphingomyelin synthase 2 over-expression induces expression of aortic inflammatory biomarkers and decreases circulating EPCs in ApoE KO mice. Life Sci. 90, 867–873 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Dong J et al. Adenovirus-mediated overexpression of sphingomyelin synthases 1 and 2 increases the atherogenic potential in mice. J. Lipid Res 47, 1307–1314 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Liu J et al. Sphingomyelin synthase 2 is one of the determinants for plasma and liver sphingomyelin levels in mice. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol 29, 850–856 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Liu J et al. Macrophage sphingomyelin synthase 2 deficiency decreases atherosclerosis in mice. Circ. Res 105, 295–303 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Fan Y et al. Selective reduction in the sphingomyelin content of atherogenic lipoproteins inhibits their retention in murine aortas and the subsequent development of atherosclerosis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol 30, 2114–2120 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Li Z et al. Impact of sphingomyelin synthase 1 deficiency on sphingolipid metabolism and atherosclerosis in mice. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol 32, 1577–1584 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Yano M et al. Increased oxidative stress impairs adipose tissue function in sphingomyelin synthase 1 null mice. PLoS ONE 8, e61380 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Kenny HC & Abel ED Heart failure in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Circ. Res 124, 121–141 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Tsao CW et al. Temporal trends in the incidence of and mortality associated with heart failure with preserved and reduced ejection fraction. JACC Heart Fail. 6, 678–685 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.van Heerebeek L & Paulus WJ Understanding heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: where are we today? Neth. Heart J 24, 227–236 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Oktay AA, Rich JD & Shah SJ The emerging epidemic of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Curr. Heart Fail. Rep 10, 401–410 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Simmonds SJ, Cuijpers I, Heymans S & Jones EAV Cellular and molecular differences between HFpEF and HFrEF: a step ahead in an improved pathological understanding. Cells 9, 242 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Chokshi A et al. Ventricular assist device implantation corrects myocardial lipotoxicity, reverses insulin resistance, and normalizes cardiac metabolism in patients with advanced heart failure. Circulation 125, 2844–2853 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Kato TS et al. Effects of continuous-flow versus pulsatile-flow left ventricular assist devices on myocardial unloading and remodeling. Circ. Heart Fail 4, 546–553 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Khan RS et al. Adipose tissue inflammation and adiponectin resistance in patients with advanced heart failure: correction after ventricular assist device implantation. Circ. Heart Fail 5, 340–348 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Rogers JK et al. Effect of rosuvastatin on repeat heart failure hospitalizations: the CORONA trial (Controlled Rosuvastatin Multinational Trial in Heart Failure). JACC Heart Fail. 2, 289–297 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Wang ZV & Scherer PE Adiponectin, the past two decades. J. Mol. Cell Biol 8, 93–100 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Hadas Y et al. Altering sphingolipid metabolism attenuates cell death and inflammatory response after myocardial infarction. Circulation 141, 916–930 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Means CK & Brown JH Sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor signalling in the heart. Cardiovasc. Res 82, 193–200 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Vessey DA, Li L, Kelley M & Karliner JS Combined sphingosine, S1P and ischemic postconditioning rescue the heart after protracted ischemia. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 375, 425–429 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Vessey DA, Li L, Kelley M, Zhang J & Karliner JS Sphingosine can pre- and post-condition heart and utilizes a different mechanism from sphingosine 1-phosphate. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol 22, 113–118 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Vessey DA, Kelley M, Li L & Huang Y Sphingosine protects aging hearts from ischemia/reperfusion injury: superiority to sphingosine 1-phosphate and ischemic pre- and post-conditioning. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev 2, 146–151 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Hofmann U et al. Protective effects of sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor agonist treatment after myocardial ischaemia-reperfusion. Cardiovasc. Res 83, 285–293 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Botta A, Elizbaryan K, Tashakorinia P, Lam NH & Sweeney G An adiponectin-S1P autocrine axis protects skeletal muscle cells from palmitate-induced cell death. Lipids Health Dis. 19, 156 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Botta A et al. An adiponectin-S1P axis protects against lipid induced insulin resistance and cardiomyocyte cell death via reduction of oxidative stress. Nutr. Metab 16, 14 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Gudz TI, Tserng KY & Hoppel CL Direct inhibition of mitochondrial respiratory chain complex III by cell-permeable ceramide. J. Biol. Chem 272, 24154–24158 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Di Paola M, Cocco T & Lorusso M Ceramide interaction with the respiratory chain of heart mitochondria. Biochemistry 39, 6660–6668 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Zigdon H et al. Ablation of ceramide synthase 2 causes chronic oxidative stress due to disruption of the mitochondrial respiratory chain. J. Biol. Chem 288, 4947–4956 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Obeid LM, Linardic CM, Karolak LA & Hannun YA Programmed cell death induced by ceramide. Science 259, 1769–1771 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Tippetts TS et al. Cigarette smoke increases cardiomyocyte ceramide accumulation and inhibits mitochondrial respiration. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord 14, 165 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Bielawska AE et al. Ceramide is involved in triggering of cardiomyocyte apoptosis induced by ischemia and reperfusion. Am. J. Pathol 151, 1257–1263 (1997). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Hickson-Bick DL, Buja LM & McMillin JB Palmitate-mediated alterations in the fatty acid metabolism of rat neonatal cardiac myocytes. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol 32, 511–519 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Sparagna GC, Hickson-Bick DL, Buja LM & McMillin JB A metabolic role for mitochondria in palmitate-induced cardiac myocyte apoptosis. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol 279, H2124–H2132 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Sparagna GC, Hickson-Bick DL, Buja LM & McMillin JB Fatty acid-induced apoptosis in neonatal cardiomyocytes: redox signaling. Antioxid. Redox Signal 3, 71–79 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Law BA et al. Lipotoxic very-long-chain ceramides cause mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and cell death in cardiomyocytes. FASEB J. 32, 1403–1416 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Basu R et al. Type 1 diabetic cardiomyopathy in the Akita (Ins2WT/C96Y) mouse model is characterized by lipotoxicity and diastolic dysfunction with preserved systolic function. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol 297, H2096–H2108 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Loffredo FS, Nikolova AP, Pancoast JR & Lee RT Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: molecular pathways of the aging myocardium. Circ. Res 115, 97–107 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Dong S et al. microRNA-21 promotes cardiac fibrosis and development of heart failure with preserved left ventricular ejection fraction by up-regulating Bcl-2. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol 7, 565–574 (2014). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Allouche M et al. Influence of Bcl-2 overexpression on the ceramide pathway in daunorubicin-induced apoptosis of leukemic cells. Oncogene 14, 1837–1845 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Ganesan V & Colombini M Regulation of ceramide channels by Bcl-2 family proteins. FEBS Lett. 584, 2128–2134 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Decaudin D et al. Bcl-2 and Bcl-XL antagonize the mitochondrial dysfunction preceding nuclear apoptosis induced by chemotherapeutic agents. Cancer Res. 57, 62–67 (1997). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Zhang J Autophagy and mitophagy in cellular damage control. Redox Biol. 1, 19–23 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Schiattarella GG et al. Nitrosative stress drives heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Nature 568, 351–356 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Franssen C et al. Metabolic comorbidities associated with endothelial inflammation and reduced no-bioavalability as a novel paradigm for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol 63, A970 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 152.Symons JD et al. Effect of continuous-flow left ventricular assist device support on coronary artery endothelial function in ischemic and nonischemic cardiomyopathy. Circ. Heart Fail 12, e006085 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Hulsmans M et al. Cardiac macrophages promote diastolic dysfunction. J. Exp. Med 215, 423–440 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Albeituni S & Stiban J Roles of ceramides and other sphingolipids in immune cell function and inflammation. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol 1161, 169–191 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Ye J Transcription factors activated through RIP (regulated intramembrane proteolysis) and RAT (regulated alternative translocation). J. Biol. Chem 295, 10271–10280 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Chen Q et al. Inverting the topology of a transmembrane protein by regulating the translocation of the first transmembrane helix. Mol. Cell 63, 567–578 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Raichur S Ceramide synthases are attractive drug targets for treating metabolic diseases. Front. Endocrinol 11, 483 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Hla T & Kolesnick R C16:0-ceramide signals insulin resistance. Cell Metab. 20, 703–705 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Turpin-Nolan SM & Bruning JC The role of ceramides in metabolic disorders: when size and localization matters. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol 16, 224–233 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Lemaitre RN et al. Circulating very long-chain saturated fatty acids and heart failure: the cardiovascular health study. J. Am. Heart Assoc 7, e010019 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Russo SB, Tidhar R, Futerman AH & Cowart LA Myristate-derived d16:0 sphingolipids constitute a cardiac sphingolipid pool with distinct synthetic routes and functional properties. J. Biol. Chem 288, 13397–13409 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Simons LA An updated review of lipid-modifying therapy. Med. J. Aust 211, 87–92 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163.Wang N et al. Intensive LDL cholesterol-lowering treatment beyond current recommendations for the prevention of major vascular events: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised trials including 327 037 participants. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 8, 36–49 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164.Ng TW et al. Dose-dependent effects of rosuvastatin on the plasma sphingolipidome and phospholipidome in the metabolic syndrome. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab 99, E2335–E2340 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165.Ye Q, Svatikova A, Meeusen JW, Kludtke EL & Kopecky SL Effect of proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 inhibitors on plasma ceramide levels. Am. J. Cardiol 128, 163–167 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 166.Reforgiato MR et al. Inhibition of ceramide de novo synthesis as a postischemic strategy to reduce myocardial reperfusion injury. Basic Res. Cardiol 111, 12 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 167.Ussher JR et al. Inhibition of serine palmitoyl transferase I reduces cardiac ceramide levels and increases glycolysis rates following diet-induced insulin resistance. PLoS ONE 7, e37703 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]