Abstract

Health systems offer unique opportunities for integrating services to promote early child development (ECD). However, there is limited knowledge about the implementation experiences of using health services to improve nurturing care and ECD, especially in Sub-Saharan Africa. We conducted a qualitative implementation evaluation to assess the delivery, acceptability, perceived changes, and barriers and facilitators associated with a pilot strategy that integrated developmental monitoring, nutritional screening, and early learning and nutrition counseling into the existing health facility– and community-based services for young children in rural Mozambique. We completed individual interviews with caregivers (N = 36), providers (N = 27), and district stakeholders (N = 10) and nine facility observational visits at three primary health facilities in October–November 2020. We analyzed data using thematic content analysis. Results supported fidelity to the intended pilot model and acceptability of nurturing care services. Respondents expressed various program benefits, including strengthened health system capacity and improved knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding nurturing care and ECD. Government leadership and supportive supervision were key facilitators, whereas health system resource constraints were key barriers. We conclude that health systems are promising platforms for supporting ECD and discuss several programmatic recommendations for enhancing service delivery and increasing potential impacts on nurturing care and ECD outcomes.

Keywords: early child development, health services, qualitative, implementation, evaluation, Mozambique

Graphical abstract:

We conducted a qualitative implementation evaluation to assess the delivery, acceptability, perceived changes, and barriers and facilitators associated with a pilot strategy that integrated developmental monitoring, nutritional screening, and early learning and nutrition counseling into the existing health facility– and community-based services for young children in rural Mozambique. We completed individual interviews with caregivers (N = 36), providers (N = 27), and district stakeholders (N = 10) and nine facility observational visits at three primary health facilities in October–November 2020. Results of thematic content analysis supported fidelity to the intended pilot model and acceptability of nurturing care services.

Introduction

In low- to middle-income countries (LMICs), 250 million children under 5 years of age (43%) are at risk of not attaining their developmental potential because of co-occurring risk factors, including poverty, malnutrition, infections, and suboptimal parenting practices.1 The burden of poor early child development (ECD) is greatest in Sub-Saharan Africa, where 66% of children are at risk.1 “Nurturing care” interventions—or those that support caregivers in providing good health, adequate nutrition, safety and security, responsive caregiving, and early learning opportunities—are effective for improving ECD outcomes.2, 3

Increasingly, multicomponent nurturing care intervention packages are being implemented in LMICs to address multiple risks and holistically promote ECD.4 These strategies most commonly integrate parenting and nutrition interventions—often delivered through home visits and/or community peer groups—under controlled conditions.5 A few noteworthy randomized trials have shown the effectiveness of integrating multi-input interventions within existing health services for improving ECD.6 Health system–based ECD interventions traditionally have utilized on one or two cadres of providers, in one particular setting, and through one primary modality to deliver services; for example, using nurses or paraprofessionals at health facilities7,8 or community health workers (CHW) to conduct home visits.9,10 Despite the emerging evidence supporting feasibility and effectiveness of such programs, there remains limited knowledge regarding how to optimize the integration and implementation of complex multi-input interventions across multiple health services and within the structures of the existing health system.11

In many LMICs, health systems have unique opportunities for delivering ECD services. They support multiple routine contacts for caregivers and young children spanning pregnancy and throughout the earliest years, involve a range of providers, offer a pyramid of services (e.g., universal and targeted), and often include services both at primary health facilities and in communities that collectively can be leveraged to promote ECD.12 Still, health systems innovations are required to scale-up and sustain the evidence-based nurturing care interventions.11, 13 Health system components that can be strengthened to support nurturing care and ECD include: (1) adopting multisectoral coordination (e.g., partnerships across health, nutrition, and social systems); (2) enhancing workforce training to deliver high-quality care (e.g., promotion of practice-based training, supportive supervision); (3) broadening data and evidence systems (e.g., integrating indicators within health management information system to track progress and quality improvements in ECD and parenting); (4) protected financing for sustainable and scaled-up ECD services; (5) advocacy and communication strategies to build demand for ECD services at the community, health system, and policy levels; and (6) creating an enabling policy environment that supports children and their caregivers.11, 12 However, there are few systems-strengthening models for promoting nurturing care and ECD within existing health and community systems in Sub-Saharan Africa.14 Evaluating the processes and experiences of stakeholders involved in implementing a health system–based ECD program model can help inform the potential of this strategy and more broadly guide improved implementation research and practice in LMICs.

In Mozambique, 52% of young children have poor cognitive and socioemotional development,15 and in Nampula Province specifically, 50% of children under 5 years of age are chronically malnourished.16 Over the past decade, the Ministry of Health (MoH) has made substantial investments toward integrating child nutrition services into primary healthcare services.17 More recently, in 2018, with the support of the Program for Appropriate Technology in Health (PATH), the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), other nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), and donors, the MoH introduced a pilot initiative in Monapo District of Nampula Province to integrate nurturing care interventions with a renewed focus on promoting ECD within existing facility- and community-based services: the Nurturing Care for ECD pilot.

Given the novelty of this pilot model for integrating parenting and ECD interventions into various existing health services, we sought to qualitatively investigate: (1) the roles and degree of engagement of providers and district governmental and nongovernmental stakeholders ; (2) the perceived acceptability of the pilot; (3) any changes at the health system, provider, and caregiver-levels; and (4) barriers and facilitators to implementation. By consolidating lessons learned through implementation of this pilot, we aimed to provide evidence for other program implementors and policymakers that may seek to integrate ECD promoting programs within health systems in LMICs. In addition, our study can inform other researchers about key elements, processes, and contexts that should be evaluated with respect to introducing nurturing care programs in real-world, low-resource settings and offer directions for future research to increase ECD program accessibility, coverage, scalability, and sustainability.

Methods

Study design

We conducted a qualitative implementation evaluation, drawing upon the theoretical dimensions represented in the RE-AIM implementation framework,18 which assesses the Reach, Adoption, Implementation, and Maintenance of interventions in real-world settings. To capture the diversity of perspectives spanning across various individuals involved in the pilot, we sampled district governmental and nongovernmental stakeholders, health facility and community providers, and caregivers. We triangulated information across their perspectives. The evaluation took place at three health facilities and their catchment areas in Monapo District, Mozambique that were prioritized by MoH and partners as the location for this pilot.

Nurturing Care for ECD pilot.

The Nurturing Care for ECD pilot was a collective action initiative that reinforced nurturing care interventions within existing health services. It was built on several years of national advocacy led by PATH, which resulted in the integration of developmental monitoring and counseling in key MoH guidelines and tools. The pilot brought together various stakeholders working in Monapo, including provincial and district health authorities; UNICEF; international NGOs such as PATH, ICAP, FHI 360 (through COVida and ALCANÇAR projects); and national NGOs, such as Associação dos Deficientes Moçambicanos (ADEMO), Associação de Educadores dos Consumidores de Água (AMASI), and h2n. PATH coordinated the partnership and provided technical oversight and support for MoH and partners.

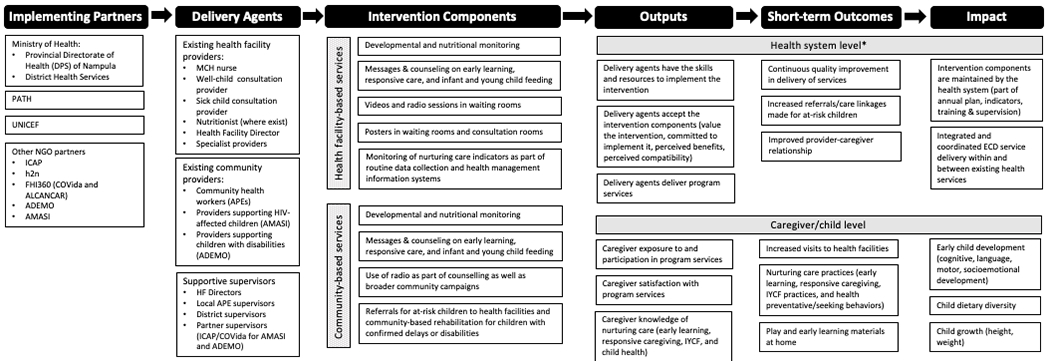

The pilot aimed to (1) strengthen the capacity of subnational health system actors to deliver quality developmental monitoring, nutritional screening, and counseling on early learning and nutrition; (2) increase families’ awareness of nurturing care services; (3) improve providers’ and caregivers’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices on nurturing care; and (4) ultimately contribute to improved ECD and nutrition outcomes in the first three years of life. The pilot involved health facility– and community-based components. See Figure 1 for the program theory of change.

Figure 1. Nurturing Care for ECD pilot: theory of change.

*The pilot’s focus at the health system level was to build health system capacity to train and support frontline workers to deliver nurturing care interventions.

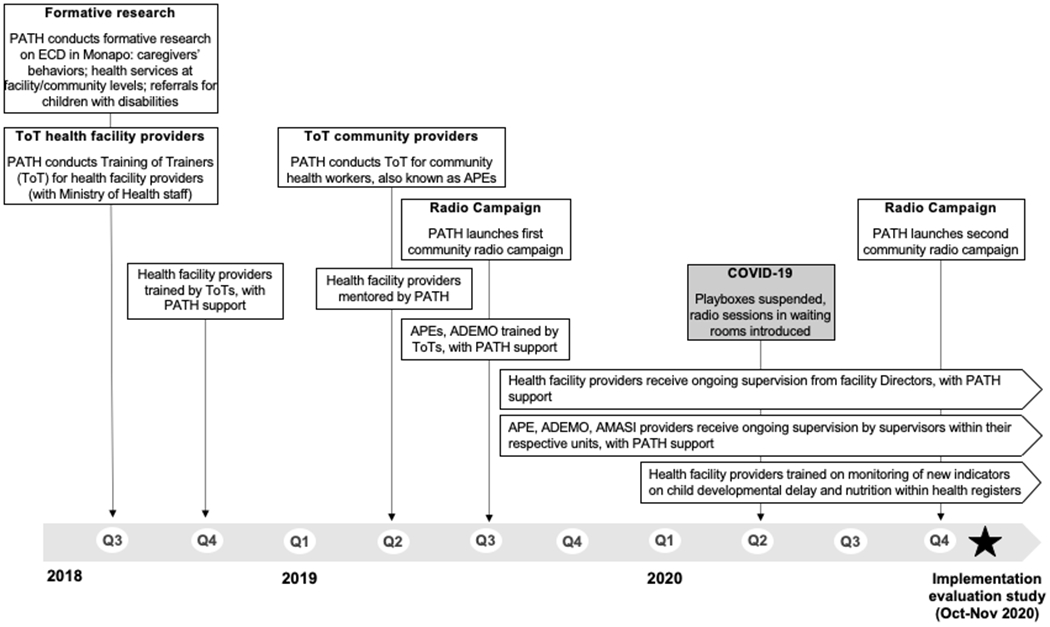

Figure 2 depicts the implementation timeline and when activities were gradually introduced beginning in mid-2018 and until the time of the evaluation. In 2020, COVID-19 caused some disruptions to routine services and necessitated some program modifications.

Figure 2.

The implementation timeline of program components introduced as part of the Nurturing Care for ECD pilot in Monapo District, Mozambique (2018–2020).

Health facility–based intervention components.

Health facility interventions leveraged low-intensity, universal (available to all families in the district) maternal and child health services: antenatal and postnatal care, and well- and sick-child consultations. PATH supported MoH to provide training, mentorship, and supportive supervision to health professionals in these touchpoints. Key programmatic activities that were supported included developmental monitoring and nutritional screening followed by the inclusion of a new ECD indicator within government well- and sick-child registers (i.e., the number of children with identified developmental delays); and counseling on early learning (on the basis of UNICEF/WHO’s Care for Child Development, which had already been adopted into MoH guidelines) and optimal maternal, infant and young child nutrition. Content on responsive caregiving was added in the latter half of the pilot to enhance providers’ capacity to support caregiver responsiveness and positive interactions with children. Visual aids (i.e., posters) on developmental milestones, age-appropriate play, and complementary feeding were newly introduced for providers to use during consultations.

Complementary awareness-generating interventions were also introduced in facility waiting rooms: posters of nurturing care messages; before COVID-19, playbox sessions with homemade toys; after COVID-19, replacing playbox sessions with radio sessions on nurturing care and COVID-19 that were broadcasted through portable radio sets; and screenings of locally produced videos on ECD and nutrition in two health facilities that had reliable electricity.

In addition to universal services, targeted services for children at risk of malnutrition and HIV also reinforced developmental monitoring and counseling through in-service trainings supported by PATH. Finally, specialist services for children with diagnosed delays or disabilities were also strengthened by introducing counseling on early learning and linking specialists with ADEMO community providers to improve referrals and follow-up.

Community-based intervention components.

At the community level, PATH strengthened the capacity of government CHWs (known as Agentes Polivalentes Elementares (APEs)) and ADEMO and AMASI providers. These community providers were prioritized due to their presence in the district, existing supervisory and remuneration structures, and readiness to integrate nurturing care interventions. In Monapo, APEs serve an average of 30 households per month and primarily provide services focused broadly on health promotion (e.g., antenatal and postnatal care) and disease prevention (e.g., management of childhood illness) to communities located near health facilities. However, the services provided by APEs are not standardized in terms of activities conducted, population coverage, or frequency or continuity of services for individual households. Although national APE training manuals had included developmental monitoring and counseling, this content has been rarely delivered before this pilot. PATH supported APEs by providing training on ECD and nutrition, relevant job aids, and including a developmental delay indicator in APE monitoring tools in coordination with provincial and district health authorities. Additionally, APE supervisors were supported quarterly to conduct supervision and review monitoring data.

In contrast to APEs who deliver universal and low-intensity services, AMASI and ADEMO provide indicated and targeted services that are more intensive for at-risk children or children with disabilities, respectively, by utilizing nonspecialist delivery agents supported by NGOs. AMASI providers primarily support HIV-affected children and visit approximately 20 households per month, biweekly, for about 6 months on average. PATH provided AMASI with short refresher trainings and quarterly supervision, as they had already received training from PATH on developmental and nutritional monitoring and counseling through an earlier project with COVida before 2018. ADEMO providers support children with disabilities and their families through early identification, referrals, counseling, and community-based rehabilitation. Each provider supports approximately 10 children through biweekly visits until they “graduate” by improvements in their condition or age. PATH supported ADEMO providers with training, weekly review meetings, and monthly supervision visits focusing on nurturing care.

Complementary awareness-generating interventions were also implemented at the community level: portable radios were given to community providers to broadcast nurturing care messages during home visits or group sessions; and district-wide mass media campaigns were disseminated in partnership with the NGO h2n to promote nurturing care and emphasize the continuity of services during COVID-19.

Sampling

The evaluation sample comprised caregivers, providers, PATH program staff, and relevant district government and nongovernmental stakeholders. We used a mixed-sampling framework: systematic sampling to recruit caregivers who utilized primary healthcare services and capture a breadth of user experiences; and purposive sampling to recruit providers and other respondents who had pertinent knowledge and experiences in delivering services to support children’s health and development.

To recruit caregivers, we used two sampling approaches. First, at each health facility in the month preceding data collection, providers prospectively assembled a list of all caregivers who had attended a child visit in the month preceding data collection. Using these lists, research assistants systematically sampled caregivers (i.e., selecting every third person from the list) and visited their households, where they conducted in-depth interviews until a total subsample of 6–7 parents was achieved per health facility catchment area. Second, we conducted three visits at each facility, where a research assistant conducted a 1-h observation of the health facility waiting area of the pediatric unit and completed a semistructured observation guide. Following the observation, the research assistant systematically sampled two caregivers (i.e., every other caregiver encountered) for “exit interviews.” Exit interviews with caregivers inquired about services received that day and were used to further triangulate information. Eligibility criteria for caregivers included: primary caregiver of a child <2.5 years of age who resided in the same household as the child, caregiver’s household was located within the catchment area of the health facility, and caregiver visited the health facility for child health service in the past month (or that day for exit interviews).

For providers, at each health facility, we purposively sampled two MCH nurses, one well-child consultation provider (preventive medicine technician focused on immunization and growth and developmental monitoring), one sick-child consultation provider (a general medicine technician focused on integrated management of childhood illnesses and growth and developmental monitoring), and the health facility director. For community providers, we purposively sampled three APEs, one AMASI provider, and one ADEMO provider per each facility catchment area.

Finally, we purposively sampled district/provincial stakeholders involved in supporting early child health and development: three PATH field staff involved in the pilot implementation, four district representatives from the MoH, and representatives from other technical partners (e.g., AMASI, ADEMO, and UNICEF).

Data collection

We developed three separate semistructured interview guides for use with caregivers, providers, and district stakeholders in accordance with the dimensions of the RE-AIM implementation framework. The health facility observation guide included open-ended questions about the environment, observed service delivery, and interactions between providers and caregivers. Data were collected by a team of four Mozambican research assistants, who had expertise in qualitative research and were bilingual in Portuguese and Makua or Portuguese and English and supervised by D.V., the research manager. A 5-day training was led by J.J. and D.V., which included three days of piloting the interview and observational guides in a non-study health facility catchment area and refining the interview guides based on daily discussions regarding the pilot data.

Interviews with caregivers were either scheduled in advance and conducted at the caregiver’s home or conducted at a private location at the health facility. Interviews with all other respondents were done in a private location, either at the health facility or a preferred location in the community. Interviews were audiorecorded, transcribed, and translated verbatim from Portuguese or Makua into English by the research assistants immediately after each interview. DV independently reviewed transcripts daily to ensure completeness and accuracy in transcription and translation. J.J. debriefed daily with the field research team to discuss field notes, any challenges encountered, any necessary refinements to the interview guides, and emerging findings, which enabled an assessment of whether data were reaching saturation or the point at which no new information was obtained.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using thematic content analysis. Each English transcript was independently coded, annotated, and analyzed using NVivo (Version 12) software by J.J., L.B., and M.N.A. First, an initial codebook was developed by J.J. based on the research questions, interview guides, and piloted and iteratively refined by L.B. and M.N.A. using three randomly selected caregiver transcripts. Second, the data analysts independently conducted line-by-line coding and documented memos for each transcript. Third, weekly meetings were held to confirm code agreement between the analysts, resolve disagreements, make codebook refinements, and discuss emerging themes. Finally, the analysts reviewed the codes to generate themes through a consensus-building process. The perspectives of the various respondent groups (and observation notes as relevant) were triangulated for each theme. Final themes were reviewed by all coauthors.

Study team

The study team comprised a collaborative and multidisciplinary team of individuals at Harvard, PATH, and Maraxis. This study was led by J.J. He and colleagues at Harvard have PhD-degree expertise in designing and evaluating nurturing care interventions. Although none of the Harvard team based in North America traveled to Mozambique because of the COVID-19 pandemic, J.J. was virtually engaged with the field research team daily throughout data collection. Data were collected by Maraxis, a local research firm that has prior experience conducting surveys and qualitative research focused on MCH in Mozambique. Maraxis colleagues had no experience implementing nurturing care interventions for ECD and played important roles as neutral interviewers and objective members of the study team. Based in Mozambique and the United States, colleagues at PATH designed the pilot, oversaw its implementation, and liaised with district officials and community leaders to prepare this study. Coauthors at PATH and Maraxis provided iterative feedback on the evaluation design and study tools that were developed by J.J. and L.B. While the analysis was independently led by Harvard researchers, coauthors at PATH and Maraxis reviewed and shared feedback on emerging themes, which helped contextualize results and enhance validity.

Ethics approvals

The research protocol for this study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and the Bioethics Committee of the MoH of Mozambique. Trained research assistants read aloud consent forms in Portuguese or Makua. Participants either provided their signatures or fingerprint to indicate consent.

Results

Sample characteristics

We interviewed a total of 73 respondents: 36 caregivers, 15 health facility providers, 12 community providers, and 10 district stakeholders. The sample was equally distributed across the three health facility catchment areas. Caregivers specifically included 32 mothers, three fathers, and one uncle who was the primary male caregiver and identified as the child’s “father.” Most caregivers were young adults (mean = 24 years; range 18–36 years) and had completed primary school (67%). Most children were under age of 12 months, and households had an average of 3–4 children. The average distance to the health facility was ~40 min (5 km). Most providers were women (70%), while most district stakeholders were men (90%). Nearly all providers (92%) and all district stakeholders completed secondary school or higher.

The findings are presented by the research question: (1) reported roles and engagement in the pilot, (2) acceptability, (3) perceived changes resulting from the pilot, and (4) implementation barriers and facilitators. Table 1 highlights the key findings.

Table 1.

Summary of main findings by program evaluation dimension (rows) and primary respondent groups (columns)

| District stakeholders (MoH, APE, ADEMO, AMASI, and UNICEF) | Providers (well-child and sick-child consultation providers, nurses, APE, ADEMO, and AMASI) | Caregivers | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Program engagement Listed in order of frequency mentioned |

Roles and responsibilities: - Training their colleagues to increase awareness and counseling for ECD - Strengthening systems to promote ECD (e.g., supervision, referrals, M&E) - Participation in the district and provincial technical working groups for ECD |

Messages promoted: - Nutrition, breastfeeding, and dietary diversity for young children - Maternal and child health - Developmental monitoring - Stimulation practices - COVID-19 prevention measures - Father involvement in nurturing care |

Messages received: - Nutrition, breastfeeding, and dietary diversity for young children - Maternal and child health - COVID-19 prevention measures - Developmental monitoring - Stimulation practices - Father involvement in nurturing care Most common sources of information: (1) health facility providers, (2) media, and (3) community-based providers |

| Acceptability | - Improved coordination and collaborations among various district stakeholders/partners - Raising awareness about ECD messages - Increased demand for ECD services in other districts |

- Satisfaction with the training and supervision received - Acceptability and usefulness of program content (i.e., nutrition and ECD) and other materials received |

- Nutrition and parenting messages were all described as useful - Satisfaction with interpersonal counseling received from health facility providers - Those who observed videos enjoyed them - Some dissatisfaction with long waiting times at health facilities |

| Perceived changes to the health system |

- Stronger partnerships among district stakeholders and partners - Improved referral processes - Increased capacities for monitoring and evaluation of children at-risk - More efficient health system operations and streamlining of child-centered services |

- More efficient health system operations and streamlining of child-centered services - Some reductions in waiting time (at well-child consultations in particular) - Improved referral processes - Increased awareness of the health system’s role in promoting ECD - Collection and monitoring of ECD indicators in health information system |

- N/A |

| Perceived changes to providers | - Increased knowledge of ECD - Increased appreciation for the links between ECD and nutrition - Enhanced training and supervision received by providers |

- Improved knowledge of ECD - Sensitization to the importance of nurturing care for ECD - Enhanced counseling skills - Increased number of responsibilities |

- N/A |

| Perceived changes to caregivers | - Improvements in some caregivers nurturing care behaviors (feeding practices and provision of homemade toys) | - Sensitization around various community health issues (e.g., decreasing stigmatization of HIV, addressing gender norms/male engagement) - Increased participation in child health services - Increased engagement of male caregivers in childcare - Improved child health outcomes - Increased identification of children at-risk (developmental or nutritional) |

- Improved care for child health and nutrition - Increased participation in child health services - Increased engagement of both male and female caregivers in play activities with and provision of toys for their children - Improved child nutrition and health outcomes (e.g., lower rates of malnutrition and illness) |

| Barriers/challenges | - Resistance to change among some providers and at health facility operations-level - Generally, long patient waiting lines at health facilities - Limited staff at health facilities - High staff turnover - Far distance between households and health facilities - Poverty (e.g., low financial resources, low providers salaries) |

- Inadequate resources to carry out responsibilities (e.g., infrastructure, personnel) - Increased responsibilities associated with the intervention and low motivation among some providers - Language barriers (i.e., no fluency in the local language) - Weak linkages between health facilities and community providers |

- Lack of money (e.g., cannot afford to buy medicine or nutritious food for children) - Some households are far from health facilities - Some messages cannot be understood by some caregivers (i.e., Portuguese language barrier or illiteracy) - Lack of male caregiver engagement in children’s health services - Limited presence of community providers (APEs, AMASI, ADEMO) in some communities |

| Facilitators | - Strong leadership and support from the district government | - Training to providers - Supervision to providers - Provision of materials and job aids (e.g., posters, pamphlets, diagnostic tools, and equipment) |

- Reinforcement of messages at both health facility and community levels - Messages that do not require financial input from caregivers - Community groups to discuss nurturing care with peers - Availability/use of local resources (e.g., surplus harvest from caregivers’ farms) |

Roles and engagement of respondents in the pilot (Table 2)

Table 2.

Pilot implementation fidelity: roles and engagement, messages delivered by providers, and exposure to services among caregivers

| Theme | Quote | Respondent |

|---|---|---|

| Roles and engagement of various respondents in the pilot | ||

| Integration of development monitoring as part of MoH trainings | We trained our staff to monitor women from their pregnancy phase and the monitoring of the child development till 5 years…We did not know that the psychomotor development starts from the womb and that this mother needs to talk from the womb till the child develops. | District representative for MCH at MoH |

| Providers use new materials and job aids to identify at-risk children | The difference now is that with RBC we never used to send children to the hospital, we did not have measuring tapes, we did not have manuals, we only had the experience to help that person who has disability. We used to help them with homemade materials for physiotherapy, but we never used to send anyone to the hospital. The difference we have now is that in PATH we have materials: manuals. Ok, we used to have manuals but it is different with PATH, because now we have credentials from the health facility, we have tape measure to measure the child to know if the child is malnourished, we have a form with all the important phases of life from 0 to 5 years, we also have tip-tap which we did not have before, we did not have radios for the people to listen to, all this. | ADEMO provider, community catchment area #2 |

| Community providers make referrals and support follow-up case management | Our activists serve as the link between the community and the health facility, even for the child’s family. It is the activist, who alerts the community there is a health problem and it is supposed to be solved at the health facility. There are cases considered as “lost cases”, where a family stopped going to the health facility, due to long distance from home to the hospital. For fear or lack of financial means, the activists identify that family and sensitize, and they go back to the hospital and even the health providers get surprised when they see them again, because they had already considered that as a lost case, maybe due to some challenges the family was not able to continue with the treatment and no one had gone to check on them…The activist is there to encourage the caregiver to continue with the treatment for her child. | ADEMO supervisor |

| Specific messages delivered by providers | ||

| Nutrition | One of my roles as a health provider is to ensure that the key messages are disseminated. Firstly, exclusive breastfeeding, this helps a lot, because if a child is not breastfed exclusively for six months, he/she has a risk of being malnourished and will also have a delayed development. This is the first message we are telling the community that the child should be exclusively breastfed. After 6 months, we have been undertaking live culinary demonstrations in the communities and here at the health facility. We have a specific day especially on Saturdays, where we undertake cooking demonstrations. These are some of the interventions as a provider of health we pass to the community. Key messages on exclusive breastfeeding. And after 6 months we demonstrate to the mother how she could prepare nutritious food for her child so that she/he could have a sound health. | Health facility Director, health facility #1 |

| Developmental monitoring | We use some materials to discover if the child is healthy or not. The material is always in my bag [reaches in bag, removes a soda can filled with some pebbles, and rattles it]. These are traditional materials from local resources. A child who is six months, when he/she wants to cry, we shake the can and we know that if the child hears, she/he will stop crying. We also monitor their development using an object we put in front of the baby, and we start moving the object and if the child if following with his/her eyes that object, then we know that the child is healthy depending on his/her age. If it is a child of 3 years, we use a ball, we take the ball and we start playing with the child [he also removes a ball made of local materials] and that is when I evaluate whether the child is healthy or not. | AMASI provider, community catchment area #3 |

| Father involvement in antenatal care and early child stimulation | I work with children and expectant mothers. First, my consultations with expectant mothers, where I counsel them and encourage them to bring their spouses during the consultations. I also counsel them on how the expectant mother should take care of her spouse and on the other hand how the spouse should take care of the expectant mother. I explain to them the importance of the father to be to speak to his child while still in its mother’s womb so that the child can learn to listen and hear his/her father’s voice that will help the child distinguish the voice in the future after the child is born. | Maternal and child health nurse #1, health facility #2 |

| Caregivers’ exposure to services | ||

| Posters on COVID, nutrition, and developmental milestones | At the hospital, I normally see a lot of images on the trees and the walls, I do not know how to read so that I can understand. I understood the drawing about Corona virus that shows washing of hands and use of mask. There is a drawing of a mother giving food her child, drawings of fruits that are good to give the baby. There is an image of child and the nurses explained that that image wanted to tell us that we should take our children all the time to the health facility. There is another one they explained that when the child completes 6 months without crawling, that child has a problem and from 9 months to so months, if a child does not to stand standing up using support, then there is a problem and we need to go for control. They talked also about social distancing because of Corona virus. | Mother #2, community catchment area #1 |

| Counseling from APEs about nutrition, WASH, and family planning | I have received some advice from them [APEs]. They talked about the care to be taken with children, how to maintain a healthy diet for the child, hygiene and how to treat the water, do family planning to avoid becoming pregnant while breastfeeding, continue to give the baby food mixed with peanuts and continue to give breast milk, giving fruits such as papaya, bananas, as this is good for the child’s health. If possible also cook an egg. | Mother #5, community catchment area #3 |

| Community radio about ECD and nutrition | Almost every day on the radio I listen to at the neighboring house or even on my phone, because here in the community they appear once a week on Fridays. I learned a lot of things, how to play with my son, how to take better care of my son, how to give the best food such as fruits and porridge mixed with peanuts….. [I learned how to make] cars using local materials and this helps my son to identify certain things and contributes to his mental health. I have put certain stones in a can and I start playing with it with my son. | Mother #5, community catchment area #3 |

District MoH and partners.

MoH staff described overseeing the implementation of ECD services delivered by facility and community providers, strengthening coordination and linkages between providers and between health facilities and community services, and providing technical support to facility providers (e.g., training on the identification of children with developmental delays). MoH officers also explained their role in training colleagues within their divisions through a “training-the-trainers” model to increase ECD knowledge.

ADEMO and AMASI district staff reported similar roles in training community providers about ECD, strengthening referral systems between facilities and communities, and increasing program monitoring activities. The UNICEF representative described a key coordinating role in the pilot and participation in a multisectoral district technical working group to promote ECD.

Providers.

All facility and community providers confirmed receiving training pertaining to ECD either from the government/MoH or PATH staff. Providers recalled learning about the importance of ECD and consistently emphasized training on the identification of children with developmental delays and malnutrition. Facility providers also emphasized training received on new monitoring and evaluation protocols integrated within existing data systems, and specifically regarding the documentation of children identified as at risk of developmental delays and malnutrition. Most providers also noted receiving new manuals, job aids, diagnostic tools (e.g., mid-upper arm circumference measuring tapes and toys to use for developmental monitoring), and portable radios to use in the facility waiting rooms or communities.

Providers also reported receiving technical assistance and supervision as part of the pilot. Facility providers mentioned receiving supervision primarily from the health facility director and the PATH district officer. Supervision for community providers varied by provider group but was commonly conducted by an individual from their own organization and the PATH district officer. All providers described receiving support ranging from on-the-job observations and feedback, coaching on how to overcome commonly encountered challenges, review of monitoring and evaluation forms. Providers reported at least monthly supervisory meetings, with ADEMO and AMASI providers reporting more frequent weekly supervisory meetings. However, one MCH nurse noted that there was a reduction in the frequency of supervision due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

PATH.

PATH staff explained their roles in leading training, providing technical assistance, and supporting government-led supervision of providers to increase knowledge and skills for promoting ECD within routine facility- and community-based services. They also highlighted an instrumental role in ECD advocacy at the district and provincial levels through partnerships with government, community provider groups, and other NGOs.

Messages delivered by providers (Table 2)

Providers reported promoting multiple nurturing care messages to caregivers, which most commonly focused on MCH (e.g., antenatal care, immunizations, HIV, and family planning), nutrition (e.g., exclusive breastfeeding and complementary feeding), and COVID-19 awareness and prevention. Although mentioned less frequently, the monitoring of child developmental status and/or counseling caregivers on the importance of early learning (e.g., stimulation and providing homemade toys) was still mentioned by the majority of providers.

In particular, despite all provider groups receiving the same training and support for integrating developmental monitoring and counseling for early learning as part of routine activities, different groups of providers emphasized certain ECD messages more than others. Among facility providers, developmental monitoring appeared to be more consistently delivered at sick-child than well-child consultations, which may be because the nature of the former often enabled a longer consultative time between providers and individual children. MCH nurses also reported emphasizing the importance of engaging fathers specifically in play and communication with the child and more generally in other childcare responsibilities such as accompanying their families to MCH visits.

Among community providers, ADEMO and AMASI providers again more consistently highlighted developmental monitoring/screening and, to a lesser degree, supporting early learning. Finally, APEs were the least consistent in their reporting of responsibilities with respect to ECD (i.e., developmental monitoring and early learning support). Instead, APEs more frequently mentioned promoting other topics, such as nutrition, MCH, WASH, and COVID-19. Nevertheless, when particularly asked to contrast whether and how counseling responsibilities and the content of messages/services delivered may have changed before and during the pilot, all provider groups (even those who may not have mentioned personally delivering ECD messages/activities) articulated a greater conceptual awareness of ECD and/or nutrition, and none described an elimination of prior routinely delivered services.

Caregivers’ exposure to services (Table 2)

Counseling from health facility providers.

Of all the program components, caregivers most strongly attributed learning about nurturing care from health facility providers. All caregivers reported receiving at least one nurturing care message during a facility-based consultation. Messages about exclusive breastfeeding and complementary feeding (e.g., preparing enriched porridge) were most recalled, followed by messages about MCH (e.g., child illness and family planning) and COVID-19 prevention measures (e.g., wearing masks and social distancing).

On the other hand, messages about ECD and activities to increase early learning opportunities were mentioned relatively less frequently and by roughly half of the caregivers. For example, some mothers recalled learning about the importance of communicating with their children beginning in the womb and making toys using household materials. It was unclear whether the other half of sampled caregivers never received such ECD messages during their recent health facility visit or if caregivers paid less attention and could not recollect these messages relative to the more consistently reported nutrition and health messages. In addition to early learning, a few caregivers highlighted the importance of providing a clean physical home environment for children to play and avoiding harsh discipline.

Media and visual resources at the health facility.

The second most common source of nurturing care messages was media at health facilities: TV, radio, and posters. Most caregivers mentioned hearing radio messages about COVID-19, nutrition, and early learning while waiting at the health facility. One mother mentioned how she learned about the role of fathers in stimulation from a radio message. Caregivers at only two of the three health facilities recalled hearing radio messages. Observational visits confirmed the presence of radios at two out of the three health facilities and their use during half of the observational visits. Observers confirmed that content of broadcasted radio messages focused on COVID-19 prevention and nutrition but also noted concerns about less-than-ideal placement and volume of radios.

Posters were another source of nurturing care messages reported by half of the caregivers. However, most caregivers only recalled posters about COVID-19. A few caregivers recalled observing posters pertaining to ECD milestones, fathers’ involvement in antenatal/childcare, dietary diversity, vaccinations, and a safe home environment for children. Notably, a few caregivers shared how the provider referred to and used posters during their consultation. Observational visits confirmed that most posters pertained to COVID-19, but posters with nurturing care messages (e.g., vaccination, nutrition, and stimulation) were also observed at all three facilities. Observers noted that most caregivers did not look at the posters, and providers did not direct caregivers’ attention to posters in the waiting areas.

Lastly, TV messages were the least commonly mentioned source of nurturing care messages. Only a few caregivers at one health facility reported observing videos. Nearly all caregivers at the other two health facilities did not recall seeing a TV at the health facility or reported the TV was turned off or was playing a nonintervention-related message (e.g., local news). Observers noted that two out of three health facilities (the same two where radios were observed) had a TV that was turned on and broadcasting messages at some point during one-third of observational visits. Observers noted that most caregivers did not watch the TV while it was broadcasting. Observers themselves could not clearly describe what was broadcasting due to the low sound and the loud surrounding noise in the waiting area.

Counseling from community providers.

Compared with facility-based sources, caregivers reported relatively less exposure to nurturing care messages from community sources. Only four caregivers mentioned an APE visit and highlighted messages about infant feeding, family planning, and COVID-19 prevention. None of these caregivers specifically mentioned receiving messages about ECD or early learning. Most caregivers had never heard of AMASI providers and were unfamiliar with their role in the community. Only two caregivers had experience with AMASI and detailed receiving messages on WASH, but not ECD-related messages. Only one caregiver was familiar with ADEMO because her neighbor received support from them.

Media campaigns in the community.

Finally, caregivers were least likely to describe exposure to nurturing care messages from media campaigns in the community. Although roughly half of the caregivers reported community or household radios as a source of information, most of them only recalled messages about COVID-19 prevention and not about nurturing care. A few caregivers reported hearing radio messages about ECD or nutrition at home or in the community.

Acceptability (Table 3)

Table 3.

Perceived acceptability of the pilot

| Theme | Quote | Respondent |

|---|---|---|

| ECD content (e.g., toys and stimulation) is of interest to district health officials | Particularly for me, what really impressed me was especially the toys [laughs…] We used to think that the toys can only be acquired from the shops, but with PATH, we have been explained that whatever we have, we could transform it into a toy for the child to play with. This is very positive and the community can do this but previous this information was not here. For us, a mother making a doll for a child was a taboo, but with this intervention, a mother can now play, there are toys for the children. This impressed me a lot. | District representative for MCH at MoH |

| Satisfaction with supervision received | We have [Dr. X] who is here and works with us directly here at the district level. He is one open person, very near to us that offers whatever support that we might need. He is always here at the health facility many times, he has been visiting various units, he also meets with me frequently, updating me of some issues he has noted for improvement in his technical backstopping role while leaving some recommendations for improvement. He also asks us to come up with solutions to certain issues that he has discovered or we have discovered on our end. [Dr. X] is very flexible and if I call him because I have an issue. | Health facility director, health facility #3 |

| Manual and screening tools are better quality | Here in ADEMO, we used to have manuals, but they were not as detailed as these ones we have received from PATH. The tools we received from PATH help us a lot because when we get to the community and discover problems around the disabled child, we are able to discover illnesses in children because the tools we are using are very explicit. Now we can make referrals for child quickly and improve the condition of that child very easily. | ADEMO provider, community catchment area #3 |

| Mothers enjoy learning about nutrition | They like hearing about how to feed your child. They always bring up the issue of child feeding during our discussions, saying that they do not have what is required to feed their children. We always tell them that it is not a matter of buying food from big shops and supermarkets for your child, you should make use of what you have at home and make it nutritive for your children. The caregivers are very engaged in such discussions. | Well-child consultation provider #1, health facility #3 |

| Satisfaction with providers’ counseling manners | I would go back to receive services from this provider because he served me well and respectfully. He even played with my son. He lifted him and made him stop crying when he was crying there inside. He never got angry with me or with my son. | Mother #1, community catchment area #2 |

All respondents underscored the importance of the pilot. District stakeholders emphasized how the pilot raised awareness about ECD, strengthened and improved coordination across existing services, and facilitated stronger multisectoral district-level partnerships. For example, a UNICEF representative described the positive collaborations formed across stakeholders traditionally working separately in health or nutrition around the shared interest to promote ECD and increased demand for ECD interventions in other districts resulting from the strong coordination through the pilot in Monapo.

Facility and community providers emphasized satisfaction with the trainings, supervision, and resources received. They unanimously perceived these inputs as enabling them to provide improved quality of care. Providers also emphasized the value and importance of promoting nutrition, ECD, and father involvement as part of their roles to support caregivers and young children. However, the specific emphasis and appreciation of ECD messages (e.g., inextricable links between nutrition and ECD) was expressed more strongly and consistently by facility providers than community providers. Furthermore, providers perceived messages about nutrition and ECD as acceptable, relevant, and useful to caregivers. Some providers noted that caregivers particularly enjoyed early learning messages like communicating and providing toys because they were new and easy to implement.

Likewise, caregivers expressed acceptability and satisfaction with messages and services received. They valued the nutrition and parenting messages and the positive interpersonal counseling skills of facility providers (e.g., empathy, clear explanations, and opportunity to ask questions). Among those who engaged with media, most expressed satisfaction and perceived media-based information as easy to understand and informative.

Among those who engaged with both facility- and community-based services, caregivers thought messages were coordinated and consistent between the two platforms. For example, one caregiver described how seeing a video about porridge preparation reminded her about receiving the same information from an APE. When asked to compare facility and community services, caregivers preferred facility counseling because facility providers had more patience, better interpersonal skills, and explained content more clearly.

Perceived changes to the health system, providers, and caregivers (Table 4)

Table 4.

Perceived changes as a result of the pilot

| Theme | Quote | Respondent |

|---|---|---|

| Perceived changes to the health system | ||

| Integrated and streamlined operations | Before I used to tend to the pediatric unit, and I used to wait for the [child health] cards. However after the training, we have created a “one stop shop” where all the technicians from CCD [sick-child provider], CCS [well-child provider], CCR [child-at-risk provider] meet together. We identify all the cards and after weighting the mothers and then send to respective sections. At the “one stop shop” area, everything is done including giving the children vitamin A, so if the child is here with a case of, for example, malnutrition, we undertake monitoring. This has changed and our work has been made a little bit easier. Everything is done at the “one stop shop,” and later they come to our [consultation] doors for specific cases. | Sick child consultation provider #1, health facility #2 |

| Increased referrals | First after the introduction of all these topics, we are now able to get a lot of referrals of mothers to the health facility. They say, “My child is not eating like he/she should eat.” We are having an influx of mothers consulting and this for us is good, because it shows that we are working. We are having a lot of referrals in this area, and this means they are also paying attention that if this child is not ok, he/she has to rush to the health facility before the condition worsens. Another success is on the side of the health worker that we are now paying attention from an integrated perspective instead of focusing one by one like nutrition or [developmental] delays. | Health facility director, health facility #1 |

| Reduced waiting time | They [caregivers] are very satisfied due to the reduction of waiting time and attendance. The time they take at the health facility has really reduced. They are happy because they no longer spend a whole day in the health facility during their consultations. They are now attended in one room regarding all the issues they bring with them to the health facility. There is no need to move around from one place to another. Once they are attended, they go back home early to continue with their other activities. | Maternal and child health nurse #1, health facility #1 |

| Perceived changes to providers | ||

| Increased knowledge about nurturing care | [Before the pilot] I did not have the knowledge of child simulation, their diet, how they should eat… Now with PATH, we learned about handwashing, tippy-taps, child feeding, how to stimulate the children, playing with their fathers. I did not have all these, that is the reason I am saying we have learned a lot of things through PATH. | ADEMO provider, community catchment area #2 |

| Capacity to carry out developmental monitoring as part of routine care | [Before the pilot] I was only dealing with the nutritional part, the pathology and the follow up. But I did not have that alerting signal, for example why is this child not sitting on its own and he/she is more than 6 months old. We used to take it lightly as we used to think that each child grows on its own speed and rate. For some children, it was alarming to see that even after 12 months they still could not walk. It was worrying but we did not know how to act. I had limitations and could only send the caregiver away because I did not have the proper diagnosis. I had no information on how to deal with such a situation… Now everything is integrated. It is very beautiful… Now I take a toy and give it to the child and assess if the child is able to sit on its own or he/she can reach the toy without difficulties and hesitation. I also carry the child on my lap and examine the neck whether the child can balance its own head without falling according to the age. | Well child consultation provider #1, health facility #3 |

| Perceived changes to caregivers/children | ||

| Increased parental engagement in providing homemade toys for children | [After the pilot] we managed to see in some of the houses some toys. In the community, parents often think that a toy is only the modern one that you can buy from the shop. But we had this opportunity [through the pilot] to demonstrate that even from the local materials, it is possible to make toys. [For example] a bottle of water could be used to make a toy car and the child could play with it. We realized that some of parents in the community are now starting to implement what they are learning from the talks at the hospitals and communities. | Head doctor, MoH representative |

| Father involvement in nurturing care | I now know that I need to make toys for my son, not to only be at the market undertaking business. I bought a mosquito net in order to protect him from malaria. I take him to the hospital always when he is not feeling ok. I made a ball for him and I normally see him running with the ball from one place to another. I help my wife to bath him and when I am at home. I make toys like a ball from plastic papers, parrot, toy car from reed, and I also make some dolls. | Father #1, community catchment area #3 |

| Improved child development and nutrition | Yes, there are changes. We have children who could not walk and today they are walking. There are children who could not sit and now they can. The malnourished children are now gaining the desired weight and growing well. | ADEMO provider, community catchment area #3 |

The pilot strengthened partnerships, with district stakeholders reporting that PATH’s technical support (e.g., training and supervision) helped improve quality in service delivery. Additionally, the pilot introduced more coordination and streamlining of services, whereby caregivers/children were triaged upon arrival to determine the most appropriate care. One provider described this as a more “child-centered” approach. This increased efficiency in service delivery contributed to reduced waiting times at health facilities, which providers perceived as another positive change in service delivery. The pilot also increased capacity for systems-level monitoring of children identified as at risk of potential delays and referrals made by community providers to facilities

District stakeholders and providers reported that the pilot increased provider knowledge of ECD and their appreciation of the links between ECD and nutrition and sensitized them to the importance of nurturing care to promote ECD. Most providers reported improved confidence, motivation, and counseling skills, which they attributed to the training and supervision received through the pilot. However, a few providers described an increased number of responsibilities, which was associated with more challenges.

The majority of respondents reported improved caregiver knowledge and practices of exclusive breastfeeding, age-appropriate complementary feeding, and toy making. Although fewer caregivers described this for themselves, providers reported greater caregiver engagement in child play and communication. MoH representatives highlighted increased health-seeking behaviors, particularly in the event of child illness or for children identified as at risk of malnutrition. A few providers and four male caregivers noted greater father involvement, describing examples of fathers becoming more attentive to their wives, spending more time caring for their children, and accompanying their wives and children to the health facility.

Finally, most respondents perceived positive impacts on child health and nutrition (e.g., children “gaining more weight” and “being sick less often”). A few caregivers also noted improvements in developmental outcomes, namely children were engaging more actively in play and becoming “more intelligent.” In addition, several providers and district stakeholders noted an increase in the early identification of children at risk and an overall reduction in cases of developmental delay.

Barriers and challenges (Table 5)

Table 5.

Barriers and facilitators to pilot implementation and nurturing care

| Theme | Quote | Respondent |

|---|---|---|

| Barriers | ||

| Limited staff availability | A challenge for some colleagues is they might know the information but maybe because of time limitation, they opt not to follow maybe when they look outside and see the long queue… We also have a lack of human resource in this area… There is only one nurse for pre-natal, maternity, family planning, all this, under the hands of a single nurse. Those with a good will undertake the work, however, the work could still be deficient. If there was a way if the personnel could be increased this would be very good. | Maternal and child health district lead, MoH |

| Reluctant attitudes by some providers | We are facing some situations that the integration of ECD is not progressing the way we would have liked it to be… If the health provider receives all this information but does not embrace it and does not really bother change his/her behavior to start implementing, then this will not function. There is an “I do not care attitude” by some health providers to understand the importance of incorporating such activities as a routine part of her/his work on a daily basis. | PATH district officer #1 |

| Far distance between communities and health facility | Distance [to health facility] is a major factor that makes it difficult for caregivers to complete proper follow-up for their children’s rehabilitation process. Most of the time caregivers do not return because of the distance from the community to the health facility. | Well-child consultation provider #1, health facility #3 |

| Lack of father involvement | Many men do not allocate time, and they think that this is the role of the woman only. However, the health of the child is important for both the mother and father and they should be both concerned. I think it is ugly. I think men should help their wives to take the child to the hospital. This is beautiful. They should dedicate some time. It is not good that the woman with two children – one on her hand or pregnant, and other baby on her back – going to the hospital. The husband should help. | Mother #2, community catchment area #1 |

| Facilitators | ||

| Strong government leadership | I think that the factors that enable our work to succeed in the district are involvement of the local leadership. I am referring to huge involvement of the district directorate of health with management of the services at the health facilities levels, such as the head doctor… The involvement of the health leaders, especially the local government, can sensitize the whole community, every political and decision-makers. | PATH district officer #1 |

| New materials/job aids received through pilot | In the past, I was just suspecting, seeing a thin child and I used to say that was because of nutrition, but now no. I have materials I can use to measure the children from 3 months to 5 years to see if the child is healthy and eating well or not. | APE #1, community catchment area #2 |

| Demonstrations during provider counseling | When the provider explains while at the same time showing you what they are talking about, it is easy to learn how to replicate. This very helpful for people like us who have a lot on our mind. | Mother #1, health facility #3 |

| Peer support | We are the 3 girls in this neighborhood that talk…We talk about family planning, we remind each other of the hospital visits and what we heard at the hospital. We give one another sweet potatoes, coconuts, and flour to make porridge for our children. | Mother #2, community catchment area #1 |

All respondents identified resource constraints as a cross-cutting barrier to program implementation and behavior change. For example, poverty contributed to structural health system challenges (e.g., high staff turnover) that, in turn, undermined program activities and quality of care. At the provider level, limited staff availability, increased responsibilities, and low provider salaries negatively affected providers’ work as they lacked essential resources to adequately fulfill their individual responsibilities. Poverty also constrained caregivers’ ability to seek healthcare and purchase necessary medication and nutritious foods for their children.

The geographical distance between households and health facilities was another challenge, which influenced coordination between health facility and community providers. Infrastructural, personnel, and communication constraints compromised referral processes for children who required further support and elicited broader concerns among providers about continuity of care for at-risk children. Poverty further exacerbated the geographical distance as a challenge for caregivers who lacked the money to pay for transport to/from health facilities and time to attend health facilities. Therefore, some caregivers were unable to follow through with referrals to the health facility. PATH staff also highlighted that negative attitudes (e.g., apathy and resistance) of some providers undermined integration of the pilot within health services. Finally, the scarcity of community providers was mentioned as a barrier to population coverage. Furthermore, the limited engagement of fathers in childcare (e.g., the lack of paternal accompaniment to child health visits) was noted as a hindrance for families and children to fully realize the benefits of the promoted parenting messages.

Facilitators (Table 5)

District stakeholders consistently highlighted that strong government leadership was key in mobilizing stakeholders and necessary for large-scale sustainable impacts on ECD. Facilitators at the provider level were the practical (e.g., provision of job aids) and technical (e.g., training and supervision) support received, though some providers desired additional support (e.g., more refresher trainings and feedback from supervisors) to provide better services to caregivers and children. Caregivers shared that the use of demonstrations and reinforcement of messages across facility and community providers made it easier for them to understand and try to change behaviors. Finally, social support was another important facilitator, with several caregivers and providers highlighting the positive ways through which fathers and other family members shared caregiving responsibilities to assist mothers. Some caregivers described meeting regularly with neighbors to discuss childcare, reminding each other of the messages received from healthcare providers, or sharing resources (e.g., vegetables from their gardens) for the benefit of the child.

COVID-19 influences on program implementation (Table 6)

Table 6.

COVID-19 influences on pilot implementation

| Theme | Quote | Respondent |

|---|---|---|

| Reduced trainings | When COVID-19 was announced, we had to stop all the trainings, we had to think differently on how to undertake on-the-job training in the COVID context. Taking into consideration that here in Monapo, the internet issue, technological issue a challenge, how to take on-the-job training with the providers in [community name #1], in [community name #2] where there is no electricity. Here in [community name #3], it is a little bit better, but how could we do for the other areas? These are some of the challenges that popped up that forced us to reconsider what was possible for the providers. | PATH district officer #1 |

| Reduced service delivery | For prenatal consultations, we used to have them on monthly basis. Currently we are having them once every three months, children with mental health issues we used to attend them every two weeks, but now we are doing it once per month. For serious malnutrition cases, we attended to them once per week but now we are having them every two weeks… there are those children who need our close monitoring, but this is not happening because of the pandemic. The child will have delays as a result of this situation. | Maternal and child health nurse #1, health facility #2 |

| Reduced duration of home visits | Before [COVID], we used to visit families’ households for about one hour to talk to the family and to sensitize. However, since we are in this pandemic era, things have changed… Now it is 15 or 20 minutes. | AMASI provider, community catchment area #3 |

| Fewer community group talks and more home visits | Before this time of this Corona virus, we used to convene people for meetings, we used to convene people for educational talks. But due to this Corona virus, I am doing a lot of house visits, house to house. I provide educational talk there, I undertake home visits there as well, I counsel there. | APE #2, community catchment area #1 |

| Suspension of play boxes at health facilities | Before we used to have toys here [at the health facility], and we would also counsel the caregivers to make toys at home using locally acquired material that they should bring to the health facility during consultations for their child use. They would bring dolls, shakers, and other toys that their children would use while waiting for their consultation or even during consultation… Year 2020 has been very different because we had to suspend the use of toys due to the current pandemic. | Well-child consultation provider #1, health facility #3 |

Providers and district stakeholders were asked to describe how the COVID-19 pandemic affected their responsibilities with respect to the pilot implementation. All respondents described substantial reductions, and even a temporary suspension, of many facility- and community-based activities (e.g., trainings, supervision, and service delivery), particularly at the start of the pandemic. By the time of this study, providers and PATH program staff reported resumption and successful delivery of most prepandemic services, albeit with several key adaptations, such as reduced frequency of consultations and mask mandates and social distancing at facilities. COVID-19 also led to the suspension of play boxes at facility waiting areas, which providers and district stakeholders described as an unfortunate adjustment to the original model. Community providers reported fewer and less frequent contacts with families, reducing the size of group counseling sessions or eliminating them altogether, and shifting to phone-based counseling. Several community providers and PATH staff also mentioned renewed efforts by PATH to distribute radios to community providers to use mass media as a delivery approach.

Discussion

We conducted a qualitative implementation evaluation to assess the delivery, acceptability, perceived changes, and barriers and facilitators associated with the Nurturing Care for ECD pilot. This pilot leveraged existing facility- and community-based services to introduce developmental monitoring and messages about early learning and responsive caregiving and strengthen support for nutrition in Monapo district, Mozambique. Through interviewing various respondents and conducting observations at facilities, we found evidence supporting fidelity to the intended model, generally high levels of engagement across respondents, and acceptability of integrating nurturing care within routine services for young children. We identified multiple achievements of this pilot for the health system, providers, and caregivers/children.

At the health system level, respondents reported enhanced supervision, more streamlined service delivery, reduced facility waiting times, increased referrals and identification of at-risk children, and support for monitoring of an indicator in the health information system regarding children identified with developmental delays. With technical and coordinating support from PATH, the pilot increased recognition and demand for ECD services delivered by existing personnel, strategically introduced new inputs (e.g., posters, radio, and video content) to support the promotion of ECD in health systems and facilitated new partnerships among district and provincial stakeholders. At the same time, systems-level implementation barriers were also identified, such as limited frontline workers, especially for delivering community-based services, and challenges in accessing care at facilities due to geographic distance and opportunity costs among caregivers.

At the provider level, the pilot increased knowledge and skills pertaining to nurturing care and the implementation of these services within routine activities. Providers valued the training, mentorship, supervision, and program materials they received. Although most providers shared positive perceptions of the pilot, health systems constraints were underscored again as negatively affecting some providers’ motivation and a sense of additional responsibilities that, in turn, affected quality of care. Health facility providers appeared to promote multiple aspects of nurturing care more consistently than community providers, with the least consistent integration of developmental monitoring and ECD-specific messages among APEs.

The less consistent focus on ECD messages relative to other nurturing care content—especially among community providers—could be due to the diverse responsibilities, expertise, and populations of beneficiaries served by the different cadre of providers.19 For example, ADEMO providers provided targeted support to persons with disabilities and likely have a stronger developmental background compared with APEs who deliver a wider range of universal services, spanning management of child illness, nutrition, WASH, and family planning.17, 20, 21 Compared with other community providers in Mozambique, APEs often have lower levels of education, less standardized supervision structures,22 and serve larger population catchments areas. Taken together, these factors likely contributed to the less regular implementation of nurturing care messages, particularly among APEs. In fact, a growing number of recent pilots—such as in Malawi23 and Brazil24—have identified similar workforce challenges as compromising the feasibility and effectiveness of using CHWs, particularly to deliver parenting interventions.

Caregivers were satisfied with the quality of services and described increased knowledge and practices about nurturing care, specifically with regards to nutrition, developmental milestones, and early learning activities. The high acceptability of the pilot model is likely due in part to the formative research conducted before the pilot, which has been underscored as an essential process of program implementation.25, 26 Early learning messages like parental communication and providing homemade toys for children were perceived as easy to implement and enjoyable by both caregivers and their children. Prior evaluations of parenting interventions have similarly highlighted that toy making and counseling on stimulation are especially of interest among providers and caregivers and identified this novelty factor as positively contributing to staff/participant engagement and program success.23, 27 Several respondents highlighted greater father involvement in child health services and engagement in learning activities with the child, suggesting a promising area for more explicit programming.28

On the basis of our results, we identified four areas that could be enhanced to improve future programming. First, counseling sessions with providers appeared more effective than media-based approaches on their own for promoting nurturing care. Inadequate adherence to protocols for media broadcasting and suboptimal placement led to relatively low media exposure. Specific technical support and monitoring of the implementation of the media-based program components may be needed to support broadcasting regularity, visibility/audibility, and to help improve uptake and maximize potential benefits. In addition, considering the shift to using outdoor facility waiting areas to mitigate COVID-19 risks, the outdoor placement of media should also be explored. Moreover, complementing the use of media with active counseling by providers can increase caregiver engagement with media and enhance complementarity to reinforce messages. In the Caribbean, Chang et al.7 created short videos of concrete stimulation activities that caregivers could try with their children and broadcasted these in the waiting areas of well-baby consultations. Following the videos, health aides facilitated a group discussion to demonstrate and provide further counseling, and nurses reinforced these messages in individual counseling sessions.

Second, while leveraging existing health system inputs can be cost-saving, systems strengthening is needed to address resource constraints like high staff turnover, large geographical and population catchment areas, and workforce and remuneration structures. As already mentioned, prior program evaluations have similarly identified workforce capacity challenges through using CHWs in particular to deliver parenting services.27, 29 Other interventions have partly addressed such system-level workforce challenges through “task sharing” or utilizing multiple providers to work together.7, 8, 30 Mobilizing and providing supportive supervision for lay workers can be a potential interim strategy for increasing workforce capacity while the government builds human resources capacity.31, 32 Considering some of these workforce constraints, greater investments in robust technical assistance will be needed to ensure a sufficient capacity of the workforce and health systems to deliver quality nurturing care services.33, 34 This includes regular refresher and on-the-job trainings and building the capacity of supervisors, such as through a “training-of-trainers” and “supervising-of-supervisors” model. Additionally, it is critical to provide support for high-quality data collection of monitoring and evaluation indicators and ensure data management systems that providers can easily access and use the collected data to inform programmatic activities for ECD. Such solutions are already being implemented in the pilot site to address high health staff turnover, including greater emphasis on on-the-job trainings for health facility providers, refresher trainings for community providers, and technical assistance that is provided by health facility directors to health facility providers.