Abstract

The pharmacokinetics of SCH 27899, a novel oligosaccharide compound of the everninomicin class with excellent activity against gram-positive strains, was studied with mice, rats, rabbits, and cynomolgus monkeys following intravenous administration as SCH 27899–N-methylglucamine–hydroxypropyl β-cyclodextrin. Concentrations of SCH 27899 in mouse serum, rat plasma, and rabbit serum were determined by a high-pressure liquid chromatography method on a poly(styrene-divinyl benzene) column, and those in monkey plasma were determined by a paired-ion chromatographic method. Plasma and serum concentrations of SCH 27899 exhibited a biexponential decline in all species following intravenous administration. The half-lives at β phase were 3.0 to 7.9 h in mice, rats, and rabbits and 24 h in cynomolgus monkeys. There was a linear relationship between the area under the curve extrapolated to infinity [AUC(I)] in mice and dose. Rabbits also exhibited dose proportionality in AUC(I). However, in rats, increasing the dose from 3 to 60 mg/kg of body weight resulted in a 49-fold increase in AUC(I). When the species was changed from mouse to rat, rabbit, or cynomolgus monkey, AUC(I) increased, whereas clearance (CL) decreased. It was concluded that the pharmacokinetics of SCH 27899 in animals varied with species; CL was the highest in mice and rats, followed by rabbits and cynomolgus monkeys.

SCH 27899, 56-deacetyl-57-demethyl-45-O-de(2-methyl-1- oxopropyl)-12O-(2,3,6-trideoxy-3-C-methyl-4-O-methyl-3- nitro-α-l-arabino-hexopyranosyl)-flambamycin 56-(2,4- dihydroxy-6-methylbenzoate), is a novel oligosaccharide compound of the everninomicin class (14, 15). It exhibits more potent antibacterial activity than clinafloxacin, teicoplanin, and vancomycin (7). SCH 27899 also shows excellent activity against fluoroquinolone-resistant strains (MIC at which 90% of the isolates are inhibited, 0.25 μg/ml) and all gram-positive strains resistant to vancomycin (MICs, ≤4 μg/ml). These in vitro data indicate that SCH 27899 could be useful against emerging gram-positive strains resistant to other contemporary antimicrobial agents.

Vancomycin has emerged as the dominant alternative therapy for serious infections caused by oxacillin-resistant staphylococci and any gram-positive infection observed in a patient with intolerance to β-lactams or macrolides. Furthermore, infections caused by enterococci that are resistant to penicillins are often treated with vancomycin (3, 5, 6, 10, 11, 13). However, this choice has been recently compromised by the rapidly increasing development of vancomycin resistance among enterococci (12). Therefore, it is important that a new compound, such as SCH 27899, be developed against these emerging gram-positive pathogens.

The objective of this study was to evaluate the pharmacokinetics of SCH 27899 in mice, rats, rabbits, and cynomolgus monkeys following intravenous administration.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Compound.

SCH 27899 (lot 23779-081-01) and SCH 9931 (internal standard) were supplied by Schering-Plough (Kenilworth, N.J.). Thiabendazole (internal standard) was obtained from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, Mo.). Acetonitrile (high-pressure liquid chromatography [HPLC] grade), ethyl acetate ammonium hydroxide (29%; American Chemical Society grade), ammonium phosphate (HPLC grade), ammonium acetate (HPLC grade), tetramethylammonium hydroxide (HPLC grade), methanol (HPLC grade), orthophosphoric acid (85%; HPLC grade), and water were obtained from Fisher Scientific Co. (Pittsburgh, Pa.).

Drug administration.

Charles River male mice (weighing 18 to 20 g) received an intravenous bolus dose (15, 30, or 45 mg of SCH 27899 equivalents/kg of body weight) of SCH 27899–N-methylglucamine–hydroxypropyl β-cyclodextrin (SCH 27899 · 3NMG · 5HPβCD). Blood samples (n = 3) were obtained predose and at 0.03, 0.08, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, and 24 h after drug administration by jugular incision immediately following euthanasia by cervical dislocation; blood samples were allowed to coagulate at room temperature. Serum samples were obtained following centrifugation at 4°C and stored at −20°C.

Charles River male rats (weighing 182 to 201 g) received an intravenous bolus dose (60 mg of SCH 27899 equivalents/kg) of SCH 27899 · 3NMG · 5HPβCB. Blood samples (n = 3) were collected predose and at 0.08, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, and 24 h postdose into heparinized tubes by cardiac puncture following anesthesia with ketamine. Plasma samples were obtained following centrifugation at 4°C and stored at −20°C.

New Zealand White male rabbits (weighing about 3 kg) received an intravenous bolus dose (3 or 15 mg/kg) of SCH 27899 · 3NMG · 5HPβCD. Blood samples (n = 4) were obtained predose and at 0.08, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 24, and 48 h postdose from the ear artery by means of a catheter and were allowed to clot. Serum samples were obtained following centrifugation at 4°C and stored at −20°C.

Male cynomolgus monkeys received an intravenous bolus dose (60 mg/kg) of SCH 27899 · 3NMG · 5HPβCD via the femoral vein. Blood samples (n = 6) were collected from the leg contralateral to the injection site leg predose and at 0.08, 0.5, 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 24, 48, 72, and 96 h postdose into heparinized tubes at 4°C and were stored at −20°C.

Determination of SCH 27899 in plasma and serum.

Concentrations of SCH 27899 in mouse serum, rat plasma, and rabbit serum were determined by an HPLC method (8). To a 0.2-ml aliquot of rat plasma were added 0.05 ml of internal standard (containing 2 μg of thiabendazole per ml), 0.05 ml of 50% acetonitrile (in water), and 1 ml of acetonitrile. The mixture was vortexed for 20 min and then centrifuged for 10 min. The organic layer was transferred to another tube and evaporated to dryness at 50°C. The residue was reconstituted in 0.4 ml of the HPLC mobile phase. A 0.1-ml aliquot of the mixture was injected into the HPLC system.

The HPLC system consisted of a Tosoh model TSK-6011 pump (Novex, San Diego, Calif.), a model AS8020 autosampler, and a model TSK-6041 tunable absorbance detector set at a wavelength of 300 nm. Separation was accomplished on a Hamilton 75 A [poly(styrene-divinyl benzene)] PRP-1 column (5-μm diameter; 150 by 4.1 nm; Hamilton Co., Reno, Nev.). The absorbance detector output was monitored with a model 3392-A integrator (Hewlett-Packard, Roseville, Calif.). The mobile phase (50 parts of acetonitrile, 5 parts of 0.2 M ammonium phosphate, and 45 parts of water, adjusted to pH 7.8) was delivered at 0.55 ml/min. All separations were carried out at ambient temperature.

There were good linear relationships between the peak height ratios (SCH 27899 versus internal standard) and the serum or plasma drug concentrations in mouse serum (0.5 to 10 μg/ml), rat plasma (0.2 to 100 μg/ml), and rabbit serum (0.5 to 50 μg/ml), with a correlation coefficient ranging from 0.9821 to 0.9999. The bias ranged from 0 to 11%, and the coefficient of variation (CV) also ranged from 0 to 11%, indicating acceptable accuracy and precision. The limits of quantitation (LOQ) were 0.5 μg/ml of mouse serum, with a bias of 2% and a CV of 7%; 0.2 μg/ml of rat plasma, with a bias of 2% and a CV of 4%; and 0.5 μg/ml of rabbit serum, with a bias of 2% and a CV of 4%.

Concentrations of SCH 27899 in monkey plasma were determined by a paired-ion chromatographic method. Ten microliters of 10% KOH was added to each milliliter of plasma. After mixing, 0.5 ml of internal standard solution (containing 20 μg of SCH 9931 per ml) was added and shaken for 1 min. Then, 4 ml of ethyl acetate was added and shaken for 10 min. After centrifugation, 3.5 ml of the supernatant was transferred to another tube and evaporated to dryness under a gentle stream of nitrogen. The residue was reconstituted with 0.4 ml of the HPLC mobile phase. A 20-μl aliquot was injected into the HPLC system.

The HPLC system consisted of a Waters model 6000A pump, a Lamda-Max model 480 UV spectrophotometer, a WISP model 712 automatic sample injector, and a BBC Goerz Metrawatt model SE120 recorder. An octyldecyl silane column (YMC A-313 S-5 200A) and an RP-18 (7 μC) guard column (Brownlee Labs) were used for the determination of SCH 27899 in monkey plasma. The mobile phase (80 parts of methanol and 20 parts of ion-pair medium) was delivered at 1 ml/min. The ion-pair medium consisted of 0.01 M tetramethylammonium hydroxide and 0.005 M ammonium acetate and was adjusted to pH 7.2 with acetic acid. The UV detector was set at 300 nm.

There was a good linear relationship between the peak height ratios (SCH 27899 versus internal standard) and the monkey plasma drug concentrations (1 to 100 μg/ml), with correlation coefficients ranging from 0.9958 to 0.9989. The bias ranged from 2 to 6%, and the CV ranged from 4 to 18%. The LOQ was estimated to be 1 μg/ml, with a bias of 6% and a CV of 18%.

Pharmacokinetic analysis.

Serum or plasma SCH 27899 concentrations above the LOQ were used for pharmacokinetic analysis (4). Values below the LOQ were designated zero (0 μg/ml). The model-dependent (compartmental) procedure was used for intravenous data to estimate the SCH 27899 concentration at time zero (the sum of two y intercepts), the distribution phase rate constant (α), the elimination phase rate constant (β), and the corresponding half-lives (0.693/α and 0.693/β). This data analysis involved fitting the individual or pooled serum or plasma SCH 27899 concentration-time data with a weighting factor of 1/Cpredicted2 to one- and two-compartment intravenous dosing models, using the nonlinear regression analysis program PCNONLIN (9). The Akaike information criterion, standard error of parameter estimates, and visual inspection of residual plots were used to select the optimal model to characterize the serum or plasma concentration-time profiles.

For pooled serum or plasma SCH 27899 concentration-time data (mice, rats, and rabbits), the area under the curve (AUC) extrapolated to infinity [AUC(I)] was calculated with the formula AUC(I) = A/α + B/β, where A and B are y intercepts and the corresponding rate constants are α and β, respectively.

For individual plasma SCH 27899 concentration-time data in monkeys, the area under the plasma concentration-time curve from time zero to the final quantifiable concentration-time point, AUC(tf), was calculated using the linear trapezoidal rule. The predicted concentration was used as the concentration at time zero. The value of AUC(tf) extrapolated to AUC(I) was calculated with the formula AUC(I) = AUC(tf) + Ctf/β, where Ctf is the estimated concentration determined from linear regression at time tf.

Total body clearance (CL) was calculated with the formula CL = dose/AUC(I). For interspecies pharmacokinetic scaling, CL values from various species were correlated with the body weight by use of the allometric equation CL = aWb, where W is body weight and a and b are the allometric coefficient and exponent, respectively (1, 2). By convention, body weight (kilograms) was considered the independent variable coefficient, and exponent values were estimated by the least-squares method from a log(CL)-versus-log(W) plot.

RESULTS

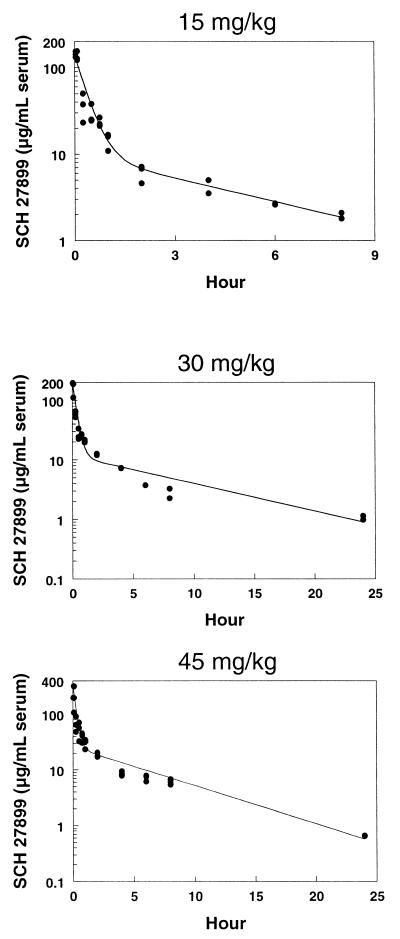

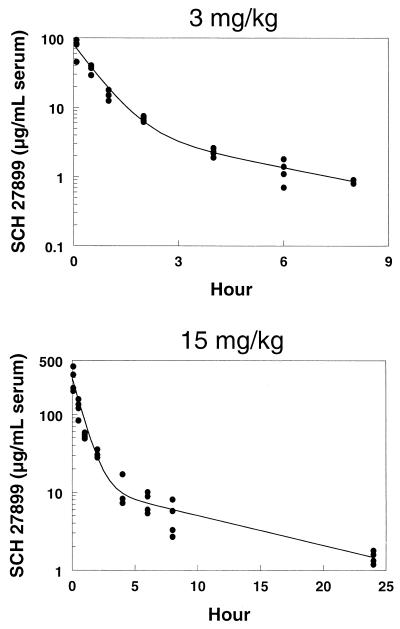

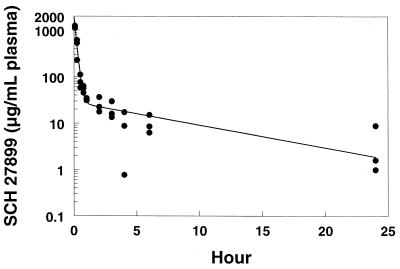

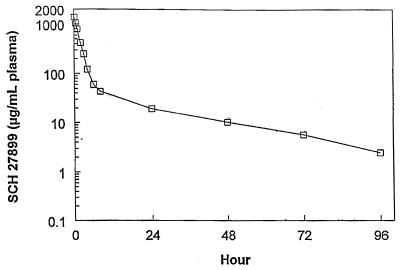

Serum concentrations of SCH 27899 in mice following intravenous doses of 15, 30, and 45 mg/kg and in rabbits following intravenous doses of 3 and 15 mg/kg are shown in Fig. 1 and 2, respectively. Plasma concentrations of SCH 27899 in rats and cynomolgus monkeys following intravenous doses of 60 mg/kg are shown in Fig. 3 and 4, respectively. The concentration-time data in all species studied exhibited a biexponential decline at all doses.

FIG. 1.

Serum concentration-time profiles in mice after intravenous administration of SCH 27899 · 3NMG · 5HPβCD at 15, 30, and 45 mg/kg.

FIG. 2.

Serum concentration-time profiles in rabbits after intravenous administration of SCH 27899 · 3NMG · 5HPβCD at 3 and 15 mg/kg.

FIG. 3.

Plasma concentration-time profiles in rats after intravenous administration of SCH 27899 · 3NMG · 5HPβCD at 60 mg/kg. Symbols: ●, actual data; –, predicted data.

FIG. 4.

Plasma concentration-time profiles in monkeys after intravenous administration of SCH 27899 · 3NMG · 5HPβCD at 60 mg/kg.

Pharmacokinetic parameters of SCH 27899 are summarized in Table 1. The half-lives at beta phase in mice, rats, and rabbits were similar, ranging from 3 to 8 h, whereas that in monkeys was much longer, with a mean of 23.9 h. After intravenous administration, the at half-life at α phase was short in all species: 0.1 to 0.5 h in mice, rats, and rabbits and 1.0 h in monkeys. In mice, there was a linear relationship (r2, 0.9992) between AUC and dose. In rabbits, there was also dose proportionality in AUC.

TABLE 1.

Pharmacokinetic parameters of SCH 27899 in mice, rats, rabbits, and cynomolgus monkeys following intravenous administration

| Species | Dose (mg/kg) | Mean valuea for:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| t1/2α (h) | t1/2β (h) | AUC(I) (μg · h/ml) | CL (ml/h/kg) | ||

| Mice | 15 | 0.23 | 3.31 | 89.9 | 167 |

| 30 | 0.20 | 6.49 | 164 | 183 | |

| 45 | 0.16 | 4.38 | 234 | 192 | |

| Rats | 60 | 0.11 | 6.16 | 570 | 105 |

| Rabbits | 3 | 0.43 | 3.04 | 69.6 | 43.1 |

| 15 | 0.50 | 7.88 | 347 | 43.3 | |

| Cynomolgus monkeys | 60 | 1.03 (11) | 23.9 (12) | 3,737 (19) | 16.7 (23) |

Numbers in parentheses are the percent CV of the pharmacokinetic parameters for six monkeys. In mice, rats, and rabbits, pharmacokinetic parameters were calculated from pooled concentration-time data; thus, no percent CV was calculated. t1/2α and t1/2β, half-lives at α and β phases, respectively.

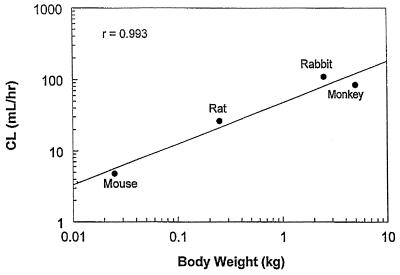

CL in both mice and rabbits appeared to be dose independent. There was a good linear relationship between CL and log(W), with an allometric coefficient of 47.5 (Fig. 5). The allometric exponent of 0.586 was slightly lower than the value (0.69) for the creatine CL body weight relationship.

FIG. 5.

Interspecies correlations of CL with body weight.

DISCUSSION

Concentrations of SCH 27899 in monkey plasma were determined by ion-pair chromatography, whereas concentrations of SCH 27899 in mouse serum, rat plasma, and rabbit serum were determined by an HPLC method with a polymeric HPLC column having a unique pH stability ranging from pH 1 to pH 13. Both methods have sufficient sensitivity, with LOQ of 1 μg/ml for ion-pair chromatography and 0.5 μg/ml for the HPLC method with a polymeric column.

The β-phase half-life determination for mice, rats, and rabbits may not be accurate due to the absence of concentration data beyond 8 h or between 8 and 24 h. Furthermore, the concentrations at different times were obtained from different animals. Nevertheless, the results of the present study indicate a β-phase half-life of 3.0 to 7.9 h for SCH 27899 in mice, rats, and rabbits. On the other hand, plasma samples from cynomolgus monkeys were obtained by serial bleeding, and there were several plasma collections well beyond 24 h (every 24 h up to 96 h after intravenous administration), yielding a reliable estimation of the β-phase half-life. It is apparent that the β-phase half-life in monkeys (24 h) was longer than that in mice, rats, and rabbits (3.0 to 7.9 h).

REFERENCES

- 1.Chung M, Radwanski E, Loebenberg D, Lin C, Oden E, Symchowicz S, Gural R P, Miller G H. Interspecies pharmacokinetic scaling of SCH 3434. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1985;15(Suppl. C):227–233. doi: 10.1093/jac/15.suppl_c.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dedrick R L. Animal scale-up. J Pharmacokinet Biopharm. 1973;1:435–461. doi: 10.1007/BF01059667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eliopoulos G M. Increasing problems in the therapy of enterococcal infections. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1993;12:409–412. doi: 10.1007/BF01967433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gibaldi M, Perrier D. Pharmacokinetics. 2nd ed. New York, N.Y: Marcel Dekker, Inc.; 1982. pp. 213–214. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jones R N, Sader H S, Erwin M E, Anderson S C. Emerging multiply resistant enterococci among clinical isolates. I. Prevalence data from 97 medical center surveillance study in the United States. Enterococcus Study Group. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 1995;21:85–93. doi: 10.1016/0732-8893(94)00147-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jones R N, Erwin M E, Anderson S C. Emerging multiply resistant enterococci among clinical isolates. II. Validation of the E test to recognize glycopeptide-resistant strains. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 1995;21:95–100. doi: 10.1016/0732-8893(94)00146-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jones R N, Barrett M S. Antimicrobial activity of Sat 27899, olyosaccharide member of the everninomycin class with a wide gram-positive spectrum. J Clin Microbiol Infect. 1995;1:35–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.1995.tb00022.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lin, C., C. Korduba, and D. Parker. Simple and sensitive high performance liquid chromatographic method for the determination of an everninomycin, SCH 27899, in rat. J. Chromatogr., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Metzler C M, Elfring G L, McEween A J. A package of computer programs for pharmacokinetic modeling. Bionetics. 1974;30:562–563. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nobel W C, Xitans Z, Gree R G A. Cotransfer of vancomycin and other resistance genes from Enterococcus faecalis NCTC 1220 to Staphylococcus aureus. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1992;93:195–198. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(92)90528-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sader H S, Pfaller M A, Tenover F C, Hollis R J, Jones R J. Evaluation and characterization of multiresistant Enterococcus faecium from twelve U.S. medical centers. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:2840–2842. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.11.2840-2842.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sanders W E, Jr, Sanders C C. Microbiological characterization of everninomycin B and D. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;6:232–238. doi: 10.1128/aac.6.3.232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schwalbe R S, Stapleton J T, Gilligan P H. Emergence of vancomycin resistance in coagulase-negative staphylococci. N Engl J Med. 1987;316:927–931. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198704093161507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weinstein M J, Luedeman G M, Oden E M, Wagman G H. Everninomycin, a new antibiotic complex from Micromonospora carbonacea. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1965;5:24–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weinstein M J, Wagman G H, Oden E M, Luedeman G M, Sloane P, Murawski A, Marquez J. Purification and biological studies of everninomycin B. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1966;5:821–827. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]