Abstract

4D-CBCT is a powerful tool to provide respiration-resolved images for the moving target localization. However, projections in each respiratory phase are intrinsically under-sampled under the clinical scanning time and imaging dose constraints. Images reconstructed by compressed sensing (CS)-based methods suffer from blurred edges. Introducing the average-4D-image constraint to the CS-based reconstruction, such as prior-image-constrained CS (PICCS), can improve the edge sharpness of the stable structures. However, PICCS can lead to motion artifacts in the moving regions. In this study, we proposed a dual-encoder convolutional neural network (DeCNN) to realize the average-image-constrained 4D-CBCT reconstruction. The proposed DeCNN has two parallel encoders to extract features from both the under-sampled target phase images and the average images. The features are then concatenated and fed into the decoder for the high-quality target phase image reconstruction. The reconstructed 4D-CBCT using of the proposed DeCNN from the real lung cancer patient data showed (1) qualitatively, clear and accurate edges for both stable and moving structures; (2) quantitatively, low-intensity errors, high peak signal-to-noise ratio, and high structural similarity compared to the ground truth images; and (3) superior quality to those reconstructed by several other state-of-the-art methods including the back-projection, CS total-variation, PICCS, and the single-encoder CNN. Overall, the proposed DeCNN is effective in exploiting the average-image constraint to improve the 4D-CBCT image quality.

Index Terms—: 4D-CBCT, image enhancement, average-image constraint, deep learning, dual-encoder architecture

I. Introduction

Stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) imposes strict requirements on the target localization accuracy due to its tight planning target volume margin and high fractional dose. Conventional three-dimensional (3D-) cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) cannot capture the motion range of the tumor and thus is limited in localizing moving targets. In recent years, four-dimensional (4D-) CBCT has been developed as a powerful tool to provide respiration-resolved images for moving target localization [1, 2]. In the 4D-CBCT, projections are assigned to different bins according to the breathing signals. Then a series of 3D-CBCT, each of which represents a respiratory phase, are reconstructed from projections in the corresponding bins to generate phase-resolved 4D images. Due to the scanning time and imaging dose constraints in clinical practice, projections acquired for each respiratory phase are always under-sampled. Based on the under-sampled projections, CBCT images reconstructed using the clinical widely-used Feldkamp–Davis–Kress (FDK) [3] algorithm suffer from poor quality with severe streak artifacts, significantly affecting the visualization of small structures and tissue edges. Improving the quality of 4D-CBCT is essential to ensure the precision of moving target localization. To accomplish that, various methods have been developed in the past years.

Motion compensation-based methods have been developed to enhance the quality of 4D-CBCT. These methods build motion models to deform and superimpose other phases onto the target phase, thus addressing the under-sampling issue in each phase of the 4D-CBCT. Rit et al. [4] estimated the motion model based on prior 4D-CT, yielding a nearly real-time motion-compensated 4D-CBCT reconstruction. However, this method is susceptible to errors caused by the breathing patterns and anatomy variations between the planning 4D-CT and the onboard 4D-CBCT. To address this limitation, methods [5–7] have been proposed to estimate the motion models based on the acquired 4D-CBCT. In these methods, inter-phase deformations are iteratively solved on the intermediate images using deformable registration, which can be time-consuming and prone to deformable registration errors due to the degraded quality of the intermediate images. These limitations adversely affect the clinical utilities of the motion compensation-based methods.

The prior-deformation-based methods [8–12] have also been proposed to reconstruct the high-quality 4D-CBCT by deforming the corresponding prior 4D-CT. The deformation vector fields (DVFs) between the prior image and the onboard images are solved by matching the deformed-prior projections and the acquired projections while regularizing the DVF energy. Although these methods can reconstruct images with CT-like appearance, they have limited accuracy in handling cases with large anatomical changes between the prior images and the onboard images. Besides, the iterative optimization for DVF is time-consuming, which can take hours to reconstruct all phases in a 4D-CBCT.

In addition, the compressed sensing (CS) theory has long been developed to address the under-sampling issue in image reconstruction. In the CS-based methods, the medical images are assumed to be piecewise. Thus, based on the CS theory, the sparsity of the image gradients can be exploited to recover the images from far fewer projections than required by the Nyquist-Shannon sampling theorem. The total variation (TV), defined as the integral of the absolute gradient of the image, has been most commonly used as a regularization term in the CS-based reconstruction methods. Sidky et al. [13] proposed the ASD-POCS algorithm to minimize the image TV in a globally uniform manner. A main limitation of CS reconstruction is that it inevitably over-smooth the anatomical edges since medical images are not always piecewise. Although various edge-preserving strategies [14–18] have been introduced to adaptively adjust the TV regularization weights in the edge regions to alleviate the edge-smoothing, the performance of these methods was limited by the edge detection accuracy. Furthermore, these CS-based methods were optimized for the 3D reconstruction without exploiting the temporal redundancy in the 4D image acquisition. In a 4D-CT/CBCT scan, some structures remain stable with minimal changes from phase to phase. In the average images reconstructed from projections of all phases, volumetric information in the stable regions can be accurately reconstructed without under-sampling artifacts. Thus, the subtraction of the target phase image from the average image can cancel the stable structures. Based on this rationale, Chen et al. [19] introduced an average-image-constrained algorithm, named PICCS, for the 4D-CT reconstruction. It reconstructed the images by minimizing a weighted sum of the target phase image TV and the difference image (between the target phase image and the average image) TV. Although the weighted constraint on the difference image TV can significantly improve the quality of the stable regions, it can also introduce motion artifacts in the moving regions. Besides, due to the iterative reconstruction, PICCS is time-consuming, which limits its clinical utility.

In recent years, deep learning-based methods, especially the convolutional neural networks (CNNs), have demonstrated superior performance in under-sampled CT/CBCT reconstruction and enhancement [20–28]. Han et al. developed a residual CNN to remove the streak artifacts in the FDK-based under-sampled CT [20], and later they studied the alternative U-Net variants based on the theory of deep convolutional framelets to further improve the FDK-based under-sampled CT enhancement [21]. Zhang et al. [22] proposed a DenseNet and deconvolution-based network, achieving improvements in both structural similarity and intensity accuracy for the FDK-based under-sampled CT. Xie et al. [23] explored the effectiveness of the GoogLeNet in removing streak artifacts in the FDK-based under-sampled CT. We [24] introduced a symmetric residual CNN (SR-CNN) to enhance the edge information in the TV-based under-sampled CBCT images. Lee et al. [26] proposed a deep-neural-network-enabled sinogram synthesis method for sparse-view CT. Hu et al. [27] developed a hybrid-domain neural network to enhance the sparse-view CT reconstruction in both projection and image domains. Zhang et al. [28] enhanced the sparse-view CT using denoising autoencoder prior. However, when the projections get sparser, deep learning models have limited enhancing capability due to the degradation of the input images [24, 25].

Inspired by the PICCS, incorporating the average image features has a great potential to address the under-sampling and thus further improve the image-enhancing performance of the deep learning models. Therefore, in this study, we proposed a dual-encoder CNN (DeCNN) to realize the average-image-constrained 4D-CBCT reconstruction. In the proposed network, two parallel encoders were used to extract features from the average images and the under-sampled target phase images, respectively. Then the average image features and the under-sampled image features were concatenated at multi-scale levels and were fed to the decoder to generate the high-quality target images. To our knowledge, it is the first study to use CNNs to exploit the average-image constraint for the 4D-CBCT reconstruction. The proposed DeCNN was tested on real patient data. The results were evaluated in both qualitative and quantitative ways and were compared against several state-of-the-art methods, demonstrating the effectiveness of the proposed dual-encoder architecture in reconstructing high-quality 4D-CBCT.

II. Methods

A. Problem Formulation

Let x ∈ RM×N×L be the real-valued CBCT images with a dimension of M × N × L voxels reconstructed from the under-sampled projections assigned to the target phase, y ∈ RM×N×L be the average CBCT images reconstructed from all projections, and z ∈ RM×N×L be the corresponding ground truth images of the target phase. Then the problem can be formulated as finding a relationship between (x, y) and z so that

| (1) |

where f indicates the image reconstruction process that can be estimated by the deep learning model.

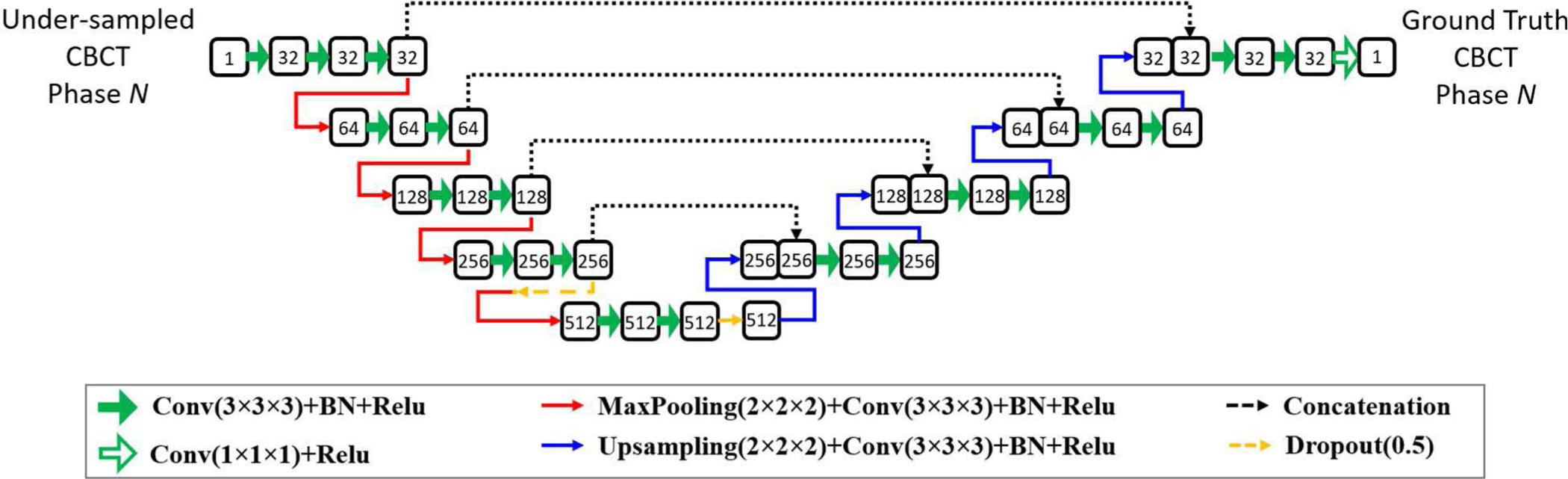

B. The architecture of the DeCNN

In this study, a multi-scale CNN with dual encoders was proposed to realize the average-image-constrained 4D-CBCT reconstruction. Figure 1 shows the architecture of the proposed DeCNN network. The two encoders extract features from the under-sampled target phase images and the average images, respectively. They had the same architecture but did not share weights. The encoders consisted of 4 scale levels, each of which had two chained convolutional blocks. The convolutional block was composed of one convolutional layer to extract the high-dimensional features, one batch normalization layer to standardize every mini-batch, and one activation layer (ReLU) to perform a nonlinear operation. Dropout layers were used in the latter scale levels of the encoders to avoid the model overfitting. The under-sampled image features and the average image features were concatenated at each scale level and were connected to the decoder for the high-quality target phase image reconstruction.

Fig. 1.

The architecture of the proposed DeCNN. Numbers in the rounded rectangles are the data channels.

C. Experiment Design

1). Model Training:

For the model training, we collected the 4D-CT data (containing 10 respiratory phases) of 25 patients with lung cancers from the public SPARE dataset, the public 4D-Lung dataset, and the public DIR-LAB dataset. And for the model validation, we collected 4D-CT data (containing 10 respiratory phases) of 3 patients with lung cancers from our institution under an IRB-approved protocol. In the model training process, 4D-CT containing 10 phases was used as the ground truth. For each simulated 4D-CBCT data, 360 uniformly distributed digitally reconstructed radiographs (DRRs) over 360° were simulated from the 4D-CT using the cone-beam half-fan geometry. Projection matrix size was set to 512 × 384, and the projection pixel size was set to 0.776mm×0.776 mm. The source-to-ioscenter distance was set to 100cm, and the source-to-detector distance was set to 150 cm, matching with the geometry of the clinical CBCT imaging systems for radiotherapy guidance. The 360 projections were binned into 10 phases with 36 uniformly distributed projections for each phase. Under-sampled images of each phase were reconstructed from the assigned projections, and the average images were reconstructed from all the projections using the FDK algorithm. All the image data were resampled to 256 × 256×96 voxels with resolutions of 1.5mm×1.5mm×2.0mm due to the memory limitation.

The end-of-expiration (EOE) phase or end-of-inspiration (EOI) phase of the 4D data was selected as the target phase. The under-sampled target phase images and the average images were fed into the proposed DeCNN, which was optimized by minimizing the mean squared error (MSE) between the predicted target phase images and the ground-truth target phase images. Optimizer was set to the “Adam” with a learning rate of 0.01. The batch size was set to 1 due to the memory limitation. Epoch number was set to 150. Validation data were used to determine the best checkpoint.

2). Model Evaluation on Patient Data:

4D-CT data (containing 10 respiratory phases) of 11 patients with lung cancers from our institution were enrolled in this study under an IRB-approved protocol. 4D-CBCT data were simulated from 4D-CT under various conditions. Note that the validation data were not included in this testing dataset. For each patient, the 4D-CBCT images were reconstructed phase by phase using the trained DeCNN.

a). Model Robustness against Dataset and Inter-patient Variability:

4D-CBCT data were simulated from 4D-CT following the same process as the training data. Aim of this study is to demonstrate that the proposed model trained on existing datasets can be used for data from a different dataset, and that the model trained on known patient structures can be used for unknown patient structure enhancement.

b). Model Robustness against Breathing Irregularity and Projection Noise Level:

Breathing patterns can vary from patient to patient and from fraction to fraction for the same patient. Thus, it is important for the model trained on uniform breathing curve to adapt 4D-CBCT with breathing variations. To this end, a breathing curve containing 36 breathing cycles acquired from a real patient using Varian RPM [29] was used to simulate the motions in 4D-CBCT. The projection simulation parameters followed the same process as the training data.

To validate the model robustness against projection noises, Poisson and normal distribution noises were incorporated in the projections. Noise signals were calculated as

| (2) |

where i and j denote the index of pixel in projection, I0 (the intensity of incident photons) was set to 105, σ2 is the variation level of normal distribution, and was set to 100.

3). Evaluation Metrics:

The 4D-CBCT images predicted by the proposed DeCNN were compared against the corresponding ground truth 4D-CT images phase by phase. The image quality of the predicted 4D-CBCT was visually inspected and was quantitatively analyzed using root mean squared error (RMSE), peak signal-to-noise ratio (PSNR), and structure similarity (SSIM) for different regions of interest (ROIs). RMSE, PSNR, and SSIM are defined as follows.

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

where ypre is the 4D-CBCT images reconstructed by algorithms, ygt is the ground-truth 4D-CBCT images, MAXgt is the maximum value of the ground-truth images, μpre is the average value of the ypre, μgt is the average value of the ygt, σpre−gt is the covariance of the ypre and ygt, σpre is the variance of the ypre, σgt is the variance of the ygt, c1 is set to 0.012 and c2 is set to 0.032.

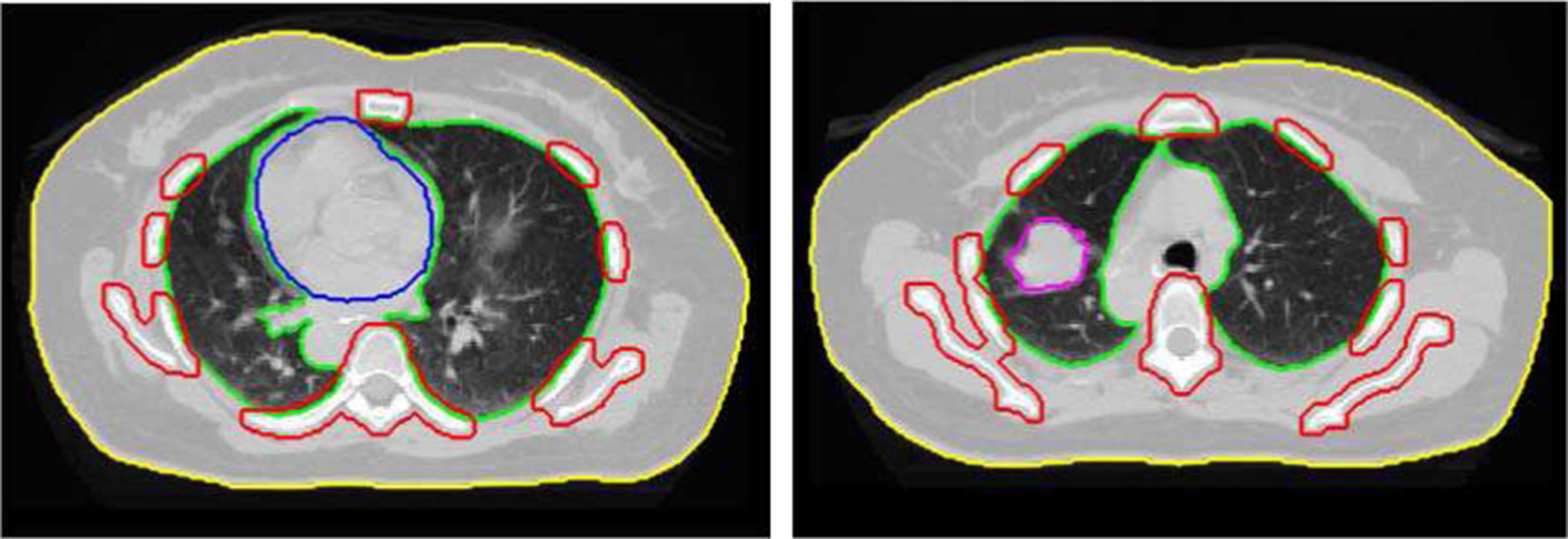

ROIs include the body, lung, heart, bone, and tumor. The body and lung regions were identified by a threshold of 800 HU and the image fill algorithm in Matlab. The bones were identified by a threshold of 1200 HU and the image fill algorithm with image dilation/erosion in Matlab. The heart and tumor were contoured by physicians on the corresponding free-breathing CT data. Representative slices of the ROIs are shown in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Representative slices of the regions-of-interest (ROIs). Yellow indicates the body, green the lung, blue the heart, red the bones, and magenta the tumor.

4). Comparison with State-of-the-art Methods:

The performance of the proposed DeCNN was compared with several methods, including (1) ASD-POCS [13], (2) PICCS [19], and (3) U-Net [30]. (1) ASD-POCS is an iterative reconstruction algorithm that reconstructs the under-sampled CBCT using the TV regularization. (2) PICCS exploits image gradient sparsity as well as the average image constraint when iteratively reconstructing the under-sampled CBCT. (3) The U-Net achieves state-of-the-art performance in the image reconstruction task and also acts as the comparison baseline to validate the superiority of the proposed dual-encoder architecture. The architecture of the U-Net is shown in Fig. 3. The U-Net has the same encoder and decoder architecture as the proposed DeCNN, but it has only one encoder for the under-sampled CBCT images.

5). Statistical Analysis:

Mann–Whitney U test was performed using Matlab 2019a to evaluate the differences between metrics of the proposed DeCNN and those of other methods mentioned in section II.C.4. A level of p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

III. Results

A. Image Quality

1). Evaluation on Different Datasets:

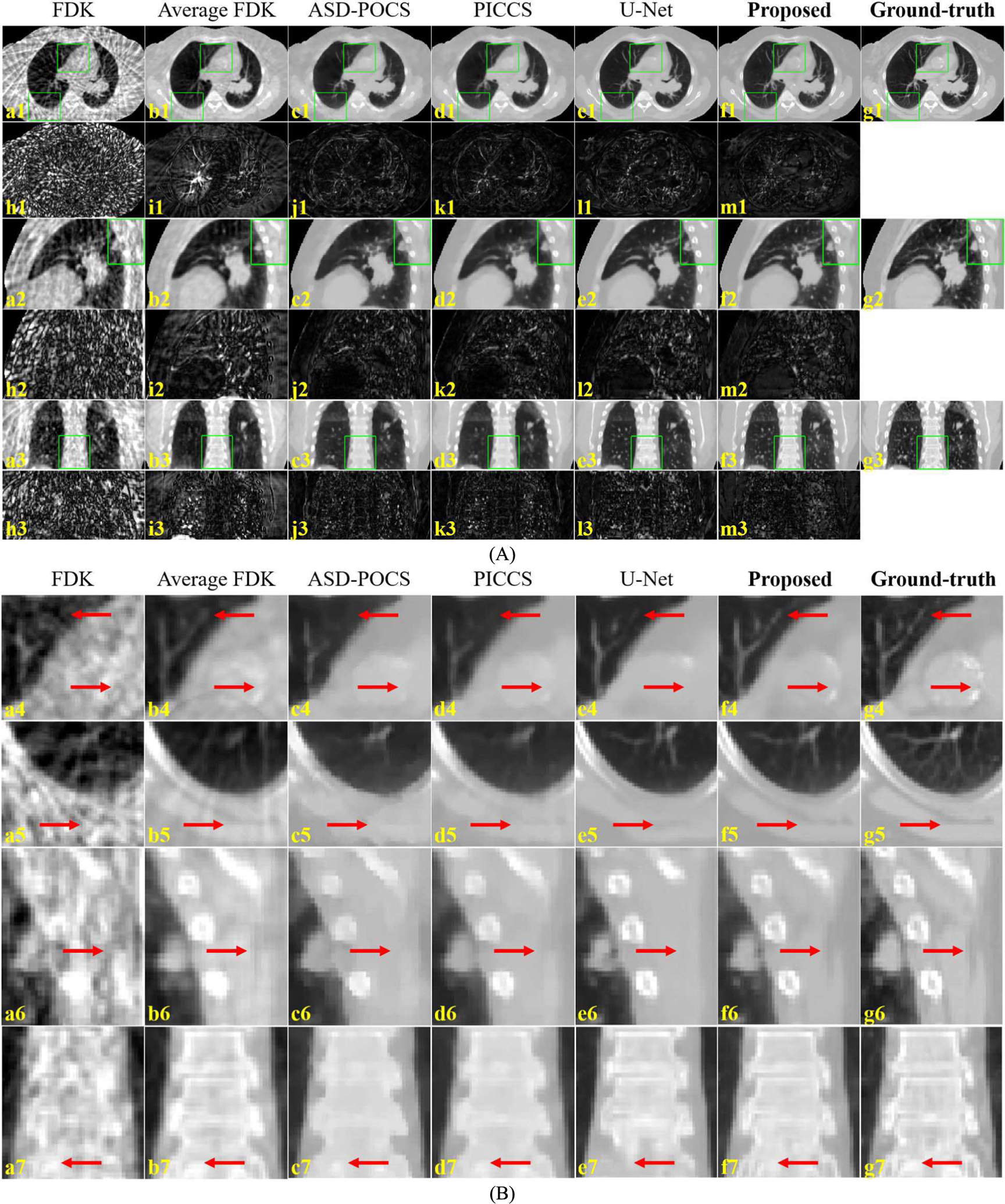

Fig. 4. shows the representative slices from phase 6 of the 4D-CBCT reconstructed by various algorithms. The average CBCT reconstructed from all projections using FDK showed less streaks and clear structures in stable regions, but it suffered from obvious motion blurriness near the pulmonary structures. Edges in the ASD-POCS were overall very blurred. PICCS alleviated the motion-induced blurriness but the pulmonary structures were still not clear. The U-Net well restored the pulmonary tissues, but there were some errors as indicated by the red arrows in the bone and soft tissue regions. The images reconstructed by the proposed DeCNN demonstrated an overall very good image quality with clear and accurate edges.

Fig. 4.

Representative slices (A) and ROIs (B) of the 4D-CBCT reconstructed by various algorithms. (a) and (c-f) are the CBCT images reconstructed by the FDK, ASD-POCS, PICCS, U-Net and the proposed DeCNN, respectively, (b) is the average CBCT reconstructed from all projections using FDK, (g) is the corresponding ground truth CT images, and (h-m) are the difference images between the (a-f) and (g). Display range is [−1000, 400] HU for the images (a-g), and [0, 400] for the difference images (h-m). Sub-figure (B) is the zoom-in views of the ROIs indicated by green boxes in sub-figure (A). Red arrows indicate image details for visual inspection.

Table. 1. shows the quantitative analysis of the 4D-CBCT images reconstructed by various algorithms. Metrics in Table 1 were calculated using all the phases in 4D-CBCTs from all the 11 testing patients. Compared with other methods, the proposed DeCNN demonstrated smaller intensity errors (lower RMSE), a higher ratio of the maximum signal power to the noise power (higher PSNR), and higher structural similarity (higher SSIM) in the body, lung, and bone regions. For the heart and tumor regions, although DeCNN showed relatively poorer intensity accuracy and/or lower max-signal-to-noise ratio than the iterative reconstruction algorithms, it demonstrated a higher structural similarity which is more favorable for visual inspection. The quantitative results further confirmed the advantages of the proposed dual-encoder architecture. All the p-values were less than 0.05, indicating that the metrics of the proposed DeCNN were significantly different from those of other methods.

TABLE I.

Quantitative analysis of the 4D-CBCT reconstructed by various algorithms.

| ASD-POCS | PICCS | U-Net | Proposed DeCNN | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RMSE | 0.025 ± 0.007 | 0.022 ± 0.006 | 0.020 ± 0.005 | 0.018 ± 0.004 |

| PSNR | 33.59 ± 2.11 | 35.22 ± 2.47 | 34.53 ± 2.19 | 35.31 ± 2.13 |

| SSIM | 0.892 ± 0.023 | 0.915 ± 0.019 | 0.932 ± 0.020 | 0.959 ± 0.012 |

| RMSE | 0.023 ± 0.005 | 0.020 ± 0.005 | 0.021 ± 0.004 | 0.018 ± 0.004 |

| PSNR | 33.90 ± 1.83 | 35.27 ± 2.18 | 33.72 ± 1.76 | 35.59 ± 1.87 |

| SSIM | 0.857 ± 0.025 | 0.883 ± 0.027 | 0.900 ± 0.022 | 0.924 ± 0.020 |

| RMSE | 0.015 ± 0.004 | 0.014 ± 0.004 | 0.017 ± 0.005 | 0.016 ± 0.006 |

| PSNR | 38.04 ± 1.81 | 38.82 ± 2.09 | 35.79 ± 2.99 | 37.89 ± 2.89 |

| SSIM | 0.948 ± 0.012 | 0.949 ± 0.012 | 0.983 ± 0.006 | 0.985 ± 0.005 |

| RMSE | 0.034 ± 0.009 | 0.027 ± 0.007 | 0.031 ± 0.007 | 0.025 ± 0.005 |

| PSNR | 30.50 ± 1.99 | 32.22 ± 2.15 | 30.41 ± 1.79 | 33.07 ± 1.72 |

| SSIM | 0.916 ± 0.018 | 0.949 ± 0.010 | 0.942 ± 0.016 | 0.974 ± 0.004 |

| RMSE | 0.023 ± 0.009 | 0.021 ± 0.008 | 0.023 ± 0.006 | 0.020 ± 0.004 |

| PSNR | 33.95 ± 2.68 | 35.81 ± 2.65 | 34.81 ± 1.85 | 35.54 ± 1.57 |

| SSIM | 0.958 ± 0.025 | 0.965 ± 0.020 | 0.967 ± 0.014 | 0.980 ± 0.005 |

Image intensities are normalized to [0, 1] to calculate the metrics. The results are presented in mean ± standard deviation.

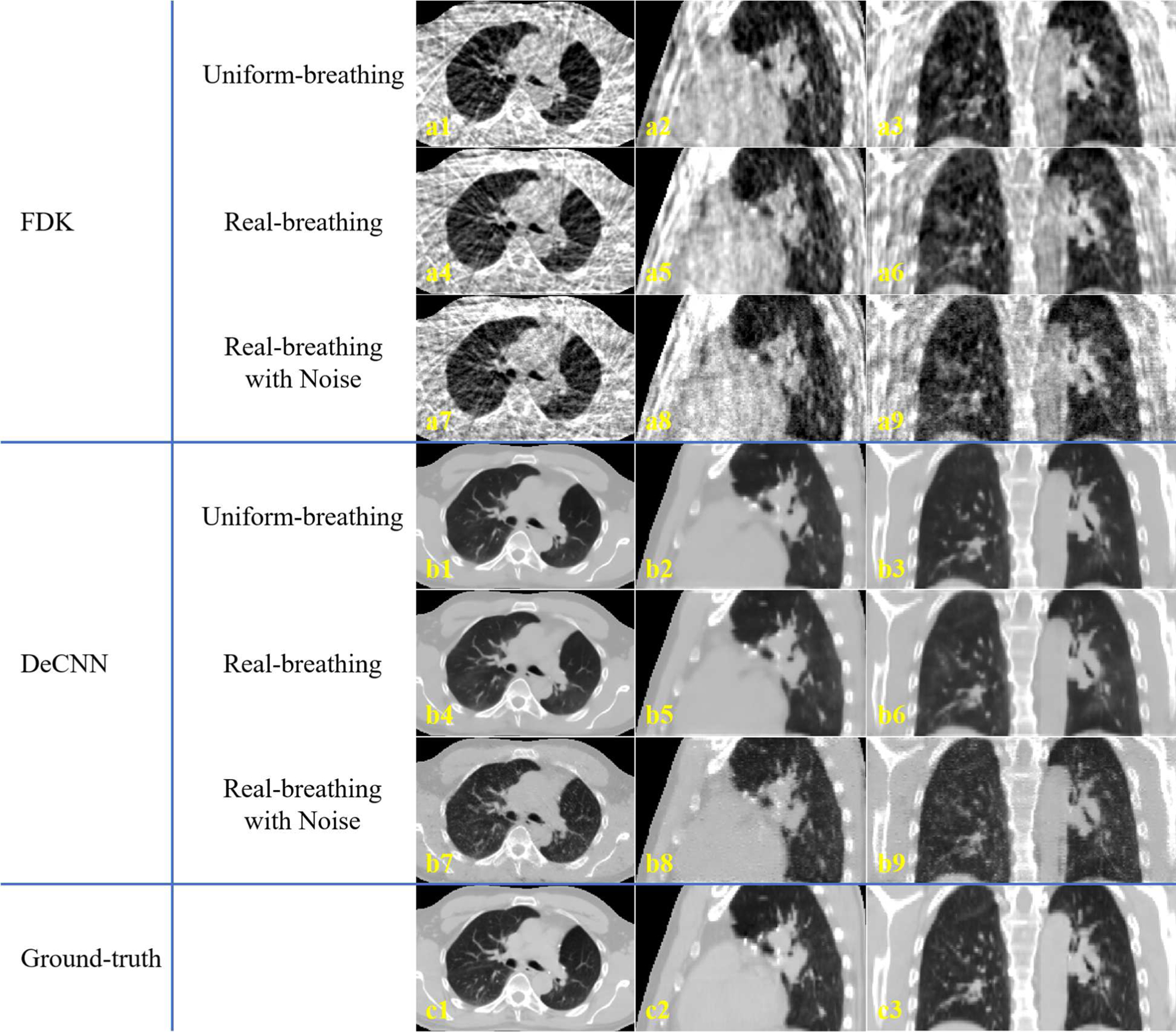

2). Evaluation on Breathing Irregularity and Projection Noise:

Fig. 5 shows the representative slices of the 4D-CBCT reconstructed by the proposed DeCNN using the uniform-breathing projections (training setting), the real-breathing projections (binned based on a real patient’s breathing curve), and the real-breathing projections with noises. Quantitative analysis is shown in Table 2. The real-breathing 4D-CBCT showed similar image quality to the uniform-breathing ones, indicating that the proposed DeCNN is robust against breathing irregularity. However, noises in projections degraded the input image quality, and thus degraded the prediction results.

Fig. 5.

Representative slices of the 4D-CBCT reconstructed by (a) FDK and (b) the proposed DeCNN from (1–3) uniform-breathing projections, (4–6) real-breathing projections, and (7–9) real-breathing projections with noises. (c) is the corresponding ground-truth images. Display range is [−1000, 400] HU.

TABLE II.

Quantitative analysis of the 4D-CBCT reconstructed under various conditions.

| Uniform breathing | Real breathing | Real breathing with noise | |

|---|---|---|---|

| RMSE | 0.018 ± 0.004 | 0.020 ± 0.005 | 0.025 ± 0.006 |

| PSNR | 35.31 ± 2.13 | 34.35 ± 2.19 | 32.38 ± 2.09 |

| SSIM | 0.959 ± 0.012 | 0.955 ± 0.013 | 0.910 ± 0.023 |

| RMSE | 0.018 ± 0.004 | 0.021 ± 0.005 | 0.027 ± 0.006 |

| PSNR | 35.59 ± 1.87 | 33.63 ± 2.14 | 31.70 ± 1.97 |

| SSIM | 0.924 ± 0.020 | 0.915 ± 0.021 | 0.839 ± 0.037 |

| RMSE | 0.016 ± 0.006 | 0.017 ± 0.006 | 0.022 ± 0.007 |

| PSNR | 37.89 ± 2.89 | 36.62 ± 2.82 | 33.34 ± 2.54 |

| SSIM | 0.985 ± 0.005 | 0.984 ± 0.006 | 0.959 ± 0.014 |

| RMSE | 0.025 ± 0.005 | 0.027 ± 0.006 | 0.033 ± 0.007 |

| PSNR | 33.07 ± 1.72 | 32.38 ± 1.76 | 29.84 ± 1.74 |

| SSIM | 0.974 ± 0.004 | 0.972 ± 0.004 | 0.943 ± 0.008 |

| RMSE | 0.020 ± 0.004 | 0.022 ± 0.005 | 0.031 ± 0.007 |

| PSNR | 35.54 ± 1.57 | 34.41 ± 1.83 | 30.56 ± 2.11 |

| SSIM | 0.980 ± 0.005 | 0.977 ± 0.006 | 0.954 ± 0.017 |

Image intensities are normalized to [0, 1] to calculate the metrics. The results are presented in mean ± standard deviation.

B. Runtime

The proposed DeCNN was implemented with the Keras (v2.2.4) framework and the TensorFlow (v1.11.0) backend. Both the model training and the model evaluations in this study were performed on a computer equipped with a GPU of NVIDIA Titan RTX (24GB memory), a CPU of Intel Xeon, and 32GB memory. The model training took about 51 hours. For the 4D-CBCT reconstruction, it took about 1.8 seconds to reconstruct images of one respiratory phase of dimension 256 × 256×96.

IV. Discussion

4D-CBCT plays an important role in the moving target localization in radiotherapy. However, due to the limitation of scanning time and dose, projections in each respiratory phase are intrinsically under-sampled, degrading the image quality. In this study, we proposed a deep learning-based method, named DeCNN, to improve the 4D-CBCT image quality with the average-image constraint. The proposed method adopted dual encoders to extract features both from the average images for the enhanced stable structures and from the target images for the accurate moving structures. Results demonstrated the effectiveness of the proposed method in reconstructing high-quality 4D-CBCT from 360 projections (36 projections for each phase). Besides, the DeCNN reconstructed the 4D-CBCT within 20 seconds and required no manually tuned parameters, making it very applicable in the clinical practice.

The proposed DeCNN demonstrated superior performance to previous methods, including the FDK, ASD-POCS, the PICCS, and the U-Net. FDK is widely used in the clinical 4D-CBCT reconstruction. It reconstructs images of each phase from the assigned projections. When the projections are under-sampled, images reconstructed using FDK suffer from severe streak artifacts, making the structure edges undistinguished. Reconstructing CBCT images from all projections using FDK, which is also referred to as the average FDK in this study, can address the under-sampling issue, and thus eliminates most streak artifacts and demonstrates clear structures in the stable regions. However, in the moving regions, such as the lung, structures are considerably blurred due to the respiration. Based on the compressed sensing theory, ASD-POCS uses the TV regularization to realize piecewise images, suppressing streaks, and noises. However, the assumption of image smoothness does not hold true for the medical images. Edges are essential to the medical images, but they lead to higher image gradients and are punished by the TV regularization during the iterative reconstruction. When the projections are getting sparser, the edges can hardly be distinguished from the streaks, and thus can be smoothed out. Some small structures can also be removed as streaks or noises. Based on the TV-regularized reconstruction, PICCS explores the temporal redundancy in the 4D imaging. In the 4D-CBCT average images, stable regions are reconstructed from all projections, and are clear and accurate. Therefore, PICCS exerts additional TV regularization on the difference image between the average image and the under-sampled image of the target phase. A hyper-parameter is used to balance the image TV and the difference image TV. In the pulmonary 4D-CBCT scans, structures move due to respiration. A higher weight on the difference image TV will improve the quality of the static regions, but it will also introduce severe motion blurriness in the pulmonary structures and lung boundaries. In this study, to balance the stable information and the motion accuracy, the weight for the image TV was set to 0.7, and the weight for the difference image TV was set to 0.3 for the PICCS reconstruction. As shown in the results in Fig. 4, the spines and surrounding areas showed clear and accurate edges since these regions mostly remain stable. But the pulmonary tissues showed marginal improvements compared to the ASD-POCS, because additional constraints on the average images do not contribute to the accuracy of the moving regions. The U-Net restored the volumetric information from the under-sampled images. It showed excellent performance in restoring the edge information. But there were some errors around the spines and soft tissues due to the severe streak artifacts in those regions in the input under-sampled images. All these errors were well corrected by the proposed DeCNN. DeCNN takes advantages of the U-Net in restoring the pulmonary tissues, and meanwhile extracts features from the average images to restore the stable parts. The weights between the under-sampled image features and average image features are learned in a dense adaptive manner during the training process. Results demonstrated the effectiveness of the proposed framework. Both the moving and stable regions showed clear and accurate edges.

Quantitatively, compared to previous methods, the proposed DeCNN showed significant improvements in SSIM for all the ROIs including body, lung, heart, bone, and tumor. In clinical practice, rigid registration is performed between CBCT and CT to determine the patient set up correction needed to align the treatment position to the planned position. However, besides rigid shifts and rotations, deformations always exist between CT and CBCT for lung patients. Therefore, manual registration is usually performed by physicians to verify the tumor coverage and the healthy tissue sparing. SSIM indicates the structural similarity with respect to the high-quality ground-truth images. It is more related to human visual inspection than intensity errors [24], which can better benefit the manual registration. Thus, such improvements are potential to improve the moving target localization accuracy using 4D-CBCT.

4D-CT image quality can vary from scanner to scanner and from patient to patient, and thus leads to the simulated 4D-CBCT of varied image quality. As demonstrated by results, the proposed DeCNN trained on the public datasets can well enhanced the 4D-CBCTs simulated from the patient 4D-CTs in our institution, indicating that the proposed model is robust against different datasets (scanners) and inter-patient variabilities.

In this study, the proposed model was trained on the 4D-CBCT reconstructed from projections binned based on a uniform breathing curve. The training process mainly aimed to have the model learn an under-sampling restoration patterns, without accounting for the breathing irregularity and the breathing pattern variations. However, breathing patterns can change from patient to patient, and even from fraction to fraction for the same patient. To validate the robustness of the proposed model against such breathing irregularity and pattern variations, we tested the DeCNN on the 4D-CBCT reconstructed from projections binned based on real patient’s breathing signals which is irregular and different from the training settings. As shown in results, the proposed DeCNN achieved similar image quality on the real-breathing 4D-CBCT to the quality on the uniform-breathing 4D-CBCT (the training setting). It indicated that the proposed model can handle the breathing irregularity and the breathing pattern variations.

In the clinical 4D-CBCT scanning, projections are contaminated with various noises which can degrade the input image for the model. However, the model trained on noise-free DRRs did not learn to correct the degradation introduced by noises. Consequently, the 4D-CBCT enhanced from the degraded input showed poor image quality. It is a general issue for deep learning-based methods that the variations from training data can degrade the model performance [31, 32]. Such degradation can be alleviated by advanced noise correction techniques.

Besides, in this study, the 4D-CBCT simulation did not account for the intra-phase motion. Evaluations on the clinical 4D-CBCT projections are warranted in future studies to further validate the effectiveness of the proposed model.

V. Conclusion

The proposed dual-encoder architecture demonstrated effectiveness in improving the 4D-CBCT image quality with the average-image constraint. The proposed DeCNN is effective and efficient in reconstruct 4D-CBCT with high image quality from only 360 projections over 36 breathing cycles, which significantly reduces the 4D-CBCT imaging dose and time and thus improves its clinical utility for the moving target localization.

Fig. 2.

The architecture of baseline U-Net for comparison. Numbers in the rounded rectangles are the data channels.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health under Grant No. R01-CA184173 and R01-EB028324.

Contributor Information

Zhuoran Jiang, Medical Physics Graduate Program, Duke University, 2424 Erwin Road Suite 101, Durham, NC, 27705, USA..

Zeyu Zhang, Medical Physics Graduate Program, Duke University, 2424 Erwin Road Suite 101, Durham, NC, 27705, USA..

Yushi Chang, Department of Radiation Oncology, Hospital of University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, 19104, USA..

Yun Ge, School of Electronic Science and Engineering, Nanjing University, 163 Xianlin Road, Nanjing, 210046, China..

Fang-Fang Yin, Department of Radiation Oncology, Duke University Medical Center, DUMC Box 3295, Durham, North Carolina, 27710, USA, and is also with Medical Physics Graduate Program, Duke University, 2424 Erwin Road Suite 101, Durham, NC 27705, USA, and is also with Medical Physics Graduate Program, Duke Kunshan University, Kunshan, Jiangsu, 215316, China..

Lei Ren, Department of Radiation Oncology, University of Maryland, Baltimore, MD, 21201, USA..

References

- [1].Sonke JJ, Zijp L, Remeijer P, and van Herk M, “Respiratory correlated cone beam CT,” Medical physics, vol. 32, no. 4, pp. 1176–1186, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Sonke J-J, Rossi M, Wolthaus J, van Herk M, Damen E, and Belderbos J, “Frameless stereotactic body radiotherapy for lung cancer using four-dimensional cone beam CT guidance,” International Journal of Radiation Oncology* Biology* Physics, vol. 74, no. 2, pp. 567–574, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Feldkamp LA, Davis LC, and Kress JW, “Practical cone-beam algorithm,” Josa a, vol. 1, no. 6, pp. 612–619, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- [4].Rit S, Wolthaus JW, van Herk M, and Sonke JJ, “On-the-fly motion-compensated cone-beam CT using an a priori model of the respiratory motion,” Medical physics, vol. 36, no. 6Part1, pp. 2283–2296, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Riblett MJ, Christensen GE, Weiss E, and Hugo GD, “Data-driven respiratory motion compensation for four-dimensional cone-beam computed tomography (4D-CBCT) using groupwise deformable registration,” Medical physics, vol. 45, no. 10, pp. 4471–4482, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Wang J, and Gu X, “Simultaneous motion estimation and image reconstruction (SMEIR) for 4D cone-beam CT,” Medical physics, vol. 40, no. 10, pp. 101912, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Brehm M, Paysan P, Oelhafen M, and Kachelrieß M, “Artifact-resistant motion estimation with a patient-specific artifact model for motion-compensated cone-beam CT,” Medical physics, vol. 40, no. 10, pp. 101913, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Zhang Y, Yin FF, Segars WP, and Ren L, “A technique for estimating 4D-CBCT using prior knowledge and limited-angle projections,” Medical physics, vol. 40, no. 12, pp. 121701, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Ren L, Zhang Y, and Yin FF, “A limited-angle intrafraction verification (LIVE) system for radiation therapy,” Medical physics, vol. 41, no. 2, pp. 020701, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Zhang Y, Yin F-F, Pan T, Vergalasova I, and Ren L, “Preliminary clinical evaluation of a 4D-CBCT estimation technique using prior information and limited-angle projections,” Radiotherapy and Oncology, vol. 115, no. 1, pp. 22–29, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Harris W, Zhang Y, Yin FF, and Ren L, “Estimating 4D-CBCT from prior information and extremely limited angle projections using structural PCA and weighted free-form deformation for lung radiotherapy,” Medical physics, vol. 44, no. 3, pp. 1089–1104, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Zhang Y, Yin F-F, Zhang Y, and Ren L, “Reducing scan angle using adaptive prior knowledge for a limited-angle intrafraction verification (LIVE) system for conformal arc radiotherapy,” Physics in Medicine & Biology, vol. 62, no. 9, pp. 3859, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Sidky EY, and Pan X, “Image reconstruction in circular cone-beam computed tomography by constrained, total-variation minimization,” Physics in Medicine & Biology, vol. 53, no. 17, pp. 4777, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Cai A, Wang L, Zhang H, Yan B, Li L, Xi X, and Li J, “Edge guided image reconstruction in linear scan CT by weighted alternating direction TV minimization,” Journal of X-ray Science and Technology, vol. 22, no. 3, pp. 335–349, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Tian Z, Jia X, Yuan K, Pan T, and Jiang SB, “Low-dose CT reconstruction via edge-preserving total variation regularization,” Physics in Medicine & Biology, vol. 56, no. 18, pp. 5949, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Liu Y, Ma J, Fan Y, and Liang Z, “Adaptive-weighted total variation minimization for sparse data toward low-dose x-ray computed tomography image reconstruction,” Physics in Medicine & Biology, vol. 57, no. 23, pp. 7923, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Lohvithee M, Biguri A, and Soleimani M, “Parameter selection in limited data cone-beam CT reconstruction using edge-preserving total variation algorithms,” Physics in Medicine & Biology, vol. 62, no. 24, pp. 9295, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Chen Y, Yin F-F, Zhang Y, Zhang Y, and Ren L, “Low dose CBCT reconstruction via prior contour based total variation (PCTV) regularization: a feasibility study,” Physics in Medicine & Biology, vol. 63, no. 8, pp. 085014, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Chen GH, Tang J, and Leng S, “Prior image constrained compressed sensing (PICCS): a method to accurately reconstruct dynamic CT images from highly undersampled projection data sets,” Medical physics, vol. 35, no. 2, pp. 660–663, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Han YS, Yoo J, and Ye JC, “Deep residual learning for compressed sensing CT reconstruction via persistent homology analysis,” arXiv preprint arXiv:1611.06391, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Han Y, and Ye JC, “Framing U-Net via deep convolutional framelets: Application to sparse-view CT,” IEEE transactions on medical imaging, vol. 37, no. 6, pp. 1418–1429, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Zhang Z, Liang X, Dong X, Xie Y, and Cao G, “A sparse-view CT reconstruction method based on combination of DenseNet and deconvolution,” IEEE transactions on medical imaging, vol. 37, no. 6, pp. 1407–1417, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Xie S, Zheng X, Chen Y, Xie L, Liu J, Zhang Y, Yan J, Zhu H, and Hu Y, “Artifact removal using improved GoogLeNet for sparse-view CT reconstruction,” Scientific reports, vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 1–9, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Jiang Z, Chen Y, Zhang Y, Ge Y, Yin F-F, and Ren L, “Augmentation of CBCT reconstructed from under-sampled projections using deep learning,” IEEE transactions on medical imaging, vol. 38, no. 11, pp. 2705–2715, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Zhao Z, Sun Y, and Cong P, “Sparse-view CT reconstruction via generative adversarial networks.” pp. 1–5.

- [26].Lee H, Lee J, Kim H, Cho B, and Cho S, “Deep-neural-network-based sinogram synthesis for sparse-view CT image reconstruction,” IEEE Transactions on Radiation and Plasma Medical Sciences, vol. 3, no. 2, pp. 109–119, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- [27].Hu D, Liu J, Lv T, Zhao Q, Zhang Y, Quan G, Feng J, Chen Y, and Luo L, “Hybrid-Domain Neural Network Processing for Sparse-View CT Reconstruction,” IEEE Transactions on Radiation and Plasma Medical Sciences, vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 88–98, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- [28].Zhang F, Zhang M, Qin B, Zhang Y, Xu Z, Liang D, and Liu Q, “REDAEP: Robust and enhanced denoising autoencoding prior for sparse-view CT reconstruction,” IEEE Transactions on Radiation and Plasma Medical Sciences, vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 108–119, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- [29].Shieh CC, Gonzalez Y, Li B, Jia X, Rit S, Mory C, Riblett M, Hugo G, Zhang Y, and Jiang Z, “SPARE: Sparse-view reconstruction challenge for 4D cone-beam CT from a 1-min scan,” Medical physics, vol. 46, no. 9, pp. 3799–3811, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Ronneberger O, Fischer P, and Brox T, “U-net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation.” pp. 234–241.

- [31].Papernot N, McDaniel P, and Goodfellow I, “Transferability in machine learning: from phenomena to black-box attacks using adversarial samples,” arXiv preprint arXiv:1605.07277, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- [32].Eykholt K, Evtimov I, Fernandes E, Li B, Rahmati A, Xiao C, Prakash A, Kohno T, and Song D, “Robust physical-world attacks on deep learning visual classification.” pp. 1625–1634.