The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in a significant increase in mortality with marked geographic variation across the United States.1 Although inherent biologic susceptibility and resilience may help explain a proportion of regional and sub-regional variation, there is emerging data supporting a powerful impact of social and environmental factors through incompletely defined mechanisms that may modulate host-virus interactions. Indeed, social vulnerability has been linked with all-cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality, and COVID-19 mortality in the United States.2 We sought to elucidate trends in excess all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in the COVID-19 era sorted by indexes of social vulnerability.

In this cross-sectional study, we analyzed deaths before (2019) and after (2020 to 2021) the COVID-19 pandemic. We linked all-cause and cardiovascular (International Classification of Diseases, Tenth revision, I00-I99) deaths at the county level, obtained from multiple cause of death files with the 2018 county-level Social Vulnerability Index (SVI), which integrates key social factors to determine the resilience of a community to encounter natural disaster.3 The SVI index ranges between 0 (least socially vulnerable) to 1 (most socially vulnerable). We divided counties into quartiles of SVI (<0.25, 0.25 to 0.50, 0.50 to 0.75, >0.75) and analyzed mean relative differences of cardiovascular and all-cause death counts in March 2020 to November 2020 and 2021 (postpandemic) versus the same period of 2019 (prepandemic). Analysis of variance was used to compare county-level mean relative differences across SVI quartiles. Spearman correlation test was used to evaluate the association between SVI and relative mean difference in county-level mortality.

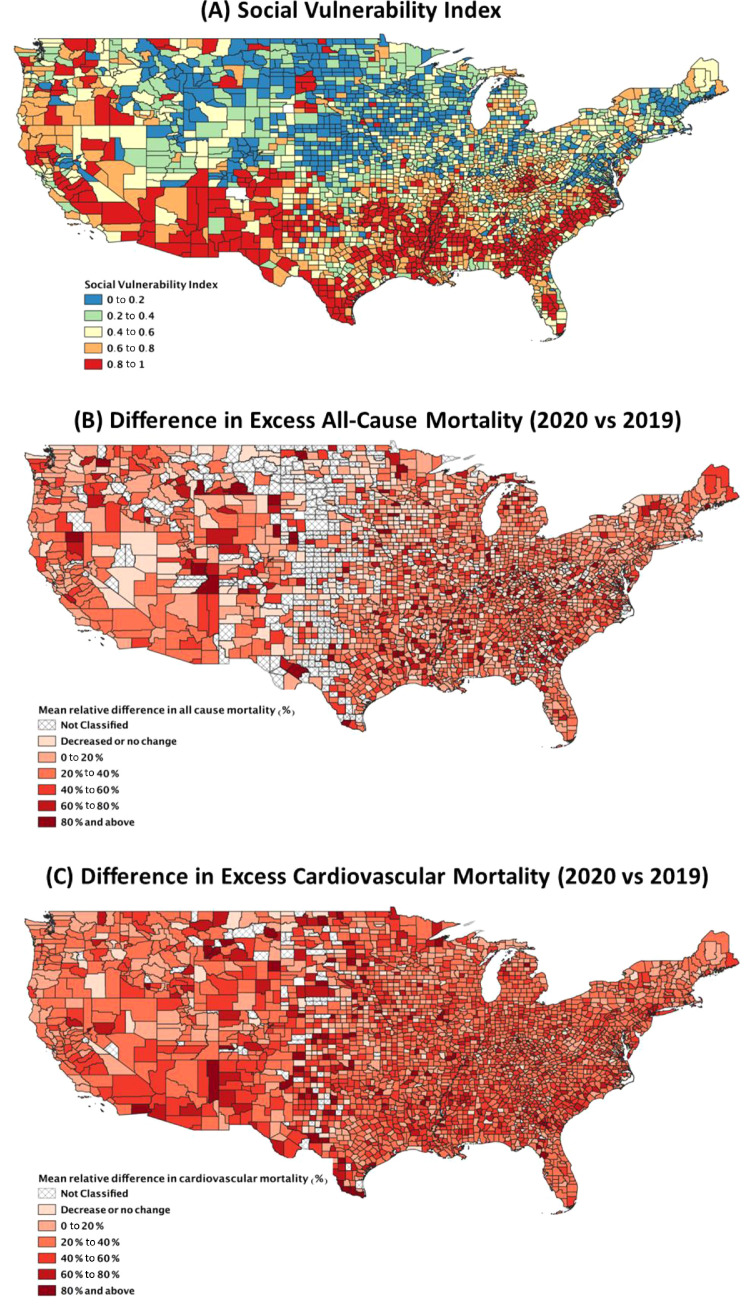

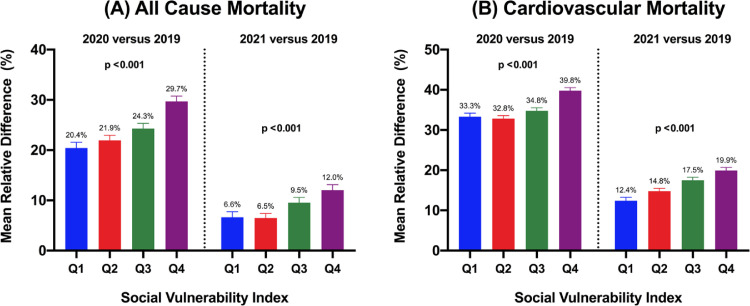

Compared with March 2019 to November 2019, there were 766,872 and 337,380 excess total deaths in 2020 and 2021, corresponding with 36% and 16% mean relative increase respectively, with substantial geographic variation across the United States (Figure 1 ). There was an increase in all-cause and cardiovascular disease (CVD) mortality in both years, with higher mean relative increases for CVD mortality when compared with all-cause mortality across all SVI quartiles. Counties in the most socially vulnerable (fourth quartile of SVI) had significantly higher mean relative increase in all-cause mortality, compared with the first quartile in both years (30% vs 20% in 2019, and 12% vs 6.6% in 2020, p <0.001, respectively). Mean relative increase in CVD mortality in the fourth quartile versus the first quartile were higher in 2020 than in 2021 (40% vs 33% in 2020, and 20% vs 12% in 2021, p <0.001, respectively). County-level SVI correlated with relative increase in all-cause (Spearman's ρ 0.13, p <0.001) and CVD mortality (Spearman's ρ 0.14, p <0.001) for 2020 versus 2019.

Figure 1.

Map of continental United States with (A) Social Vulnerability Index; (B) differences in excess all-cause mortality, and (C) difference in excess cardiovascular mortality.

Figure 2.

Mean relative difference in (A) all-cause mortality and (B) cardiovascular mortality in 2020 and 2021 compared with 2019. Q = quartile.

These data suggest an important impact of social vulnerability and both all-cause mortality and CVD mortality. Our findings are consistent with previous studies, showing that socioeconomically disadvantaged patients and other poorly defined factors conspire to predispose patients to excess risk of dying from COVID-19 infections.4 Additionally, socially vulnerable patients may have a higher impact of indirect effects of COVID-19, such as access to healthcare, financial toxicity, and psychosocial support. Although the mechanisms driving this disproportionate increase in risk are not fully understood, inequalities in living conditions, structural racism, and health literacy/advocacy may also play into susceptibility and resilience to the direct and indirect effects of COVID-19.

Our findings call for increased recognition and awareness of the continued problem of geographic disparities in mortality that have now been exacerbated by COVID-19. To realize equitable health for all, policy efforts, resources, and investment may all be needed to help mitigate the disproportionate societal vulnerability. Many co-morbid conditions (e.g., obesity, diabetes mellitus) that potentially exacerbate COVID-19 severity,5 are a consequence of an array of adverse sociodemographic factors that associate with social vulnerability. Important limitations of our analysis include population-level data that may not account for possible confounders, exposure misclassification, and the use of provisional mortality data for 2021.

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. United States COVID-19 cases and deaths by state over time columns in this dataset. Available at: https://data.cdc.gov/Case-Surveillance/United-States-COVID-19-Cases-and-Deaths-by- State-o/9mfq-cb36. Accessed on 03/01/2022.

- 2.Freese KE, Vega A, Lawrence JJ, Documet PI. Social vulnerability is associated with risk of COVID-19 related mortality in U.S. Counties with confirmed cases. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2021;32:245–257. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2021.0022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC/ATSDR Social Vulnerability Index. Available at: https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/placeandhealth/svi/index.html. Accessed on 03/01/2022.

- 4.Li AY, Hannah TC, Durbin JR, Dreher N, Mcauley FM, Marayati NF, Spiera Z, Ali M, Gometz A, Kostman JT, Choudhri TF. Multivariate analysis of black race and environmental temperature on COVID-19 in the US. Am J Med Sci. 2020;360:348–356. doi: 10.1016/j.amjms.2020.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Richardson S, Hirsch JS, Narasimhan M, Crawford JM, McGinn T, Davidson KW, the Northwell COVID-19 Research Consortium. Barnaby DP, Becker LB, Chelico JD, Cohen SL, Cookingham J, Coppa K, Diefenbach MA, Dominello AJ, Duer-Hefele J, Falzon L, Gitlin J, Hajizadeh N, Harvin TG, Hirschwerk DA, Kim EJ, Kozel ZM, Marrast LM, Mogavero JN, Osorio GA, Qiu M, Zanos TP. Presenting characteristics, comorbidities, and outcomes among 5700 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in the New York City area. JAMA. 2020;323:2052–2059. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]