Abstract

The in vivo pharmacodynamic activities of two glycylcyclines (GAR-936 and WAY 152,288) were assessed in an experimental murine thigh infection model in neutropenic mice. Mice were infected with one of several strains of Streptococcus pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, or Klebsiella pneumoniae. Most infections were treated with a twice-daily dosing schedule, with administration of 0.75 to 192 mg of GAR-936 or WAY 152,288 per kg of body weight. A maximum-effect dose-response model was used to calculate the dose that produced a net bacteriostatic effect over 24 h of therapy. This dose was called the bacteriostatic dose. More extensive dosing studies were performed with S. pneumoniae 1199, E. coli ATCC 25922, and K. pneumoniae ATCC 43816, with doses being given as one, two, four, or eight equal doses over a period of 24 h. The dosing schedules were designed in order to minimize the interrelationship between the various pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic parameters studied. These parameters were time above 0.03 to 32 times the MIC, area under the concentration-time curve (AUC), and maximum concentration of drug in serum (Cmax). The bacteriostatic dose remained essentially the same, irrespective of the dosing frequency, for S. pneumoniae 1199 (0.3 to 0.9 mg/kg/day). For E. coli ATCC 25922 and K. pneumoniae ATCC 43816, however, more frequent dosing led to lower bacteriostatic doses. Pharmacokinetic studies demonstrated dose-dependent elimination half-lives of 1.05 to 2.34 and 1.65 to 3.36 h and serum protein bindings of 59 and 71% for GAR-936 and WAY 152,288, respectively. GAR-936 and WAY 152,288 were similarly effective against the microorganisms studied, with small differences in maximum effect and 50% effective dose. The glycylcyclines were also similarly effective against tetracycline-sensitive and tetracycline-resistant bacteria. Time above a certain factor (range, 0.5 to 4 times) of the MIC was a better predictor of in vivo efficacy than Cmax or AUC for most organism-drug combinations. The results demonstrate that in order to achieve 80% maximum efficacy, the concentration of unbound drug in serum should be maintained above the MIC for at least 50% of the time for GAR-936 and for at least 75% of the time for WAY 152,288. The results of these experiments will aid in the rational design of dose-finding studies for these glycylcyclines in humans.

GAR-936 and WAY 152,288 are members of the class of glycylcyclines, a new group of antibiotics derived from minocycline. These drugs have potent activity against a variety of tetracycline-sensitive and tetracycline-resistant bacteria (1–3, 5, 8, 10, 14, 15).

The objective of the present study was to determine the effects of various dosing regimens on the in vivo efficacy of GAR-936 and WAY 152,288 and identify which pharmacokinetic or pharmacodynamic parameter best correlated with efficacy. The in vivo antibacterial activities of GAR-936 and WAY 152,288 against several isolates of common human pathogens (Streptococcus pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, and Klebsiella pneumoniae) were determined in the neutropenic murine thigh infection model. This infection model has been used for this purpose before (12) because it has the advantage of allowing quantitative measurements of bacterial numbers in the infected thigh muscle to be made.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacteria, media, and antibiotics.

Experiments were performed with the following bacterial strains: E. coli ATCC 25922 (American Type Culture Collection [ATCC], Rockville, Md.), K. pneumoniae ATCC 43816, E. coli 894 (tetracycline resistant), S. pneumoniae 1199 (tetracycline resistant), S. pneumoniae ATCC 10813, S. pneumoniae ATCC 49619, S. pneumoniae 1020 (tetracycline resistant), S. pneumoniae 1293 (tetracycline resistant), S. pneumoniae 1396 (tetracycline resistant), S. aureus ATCC 25923, S. aureus ATCC 33591 (methicillin resistant, tetracycline resistant), S. aureus ATCC 29213, and S. aureus WIS-2 (methicillin resistant, tetracycline sensitive).

All organisms except the S. pneumoniae isolates were grown, subcultured, and quantified in Mueller-Hinton broth and agar (Gibco, Middleton, Wis.). For the S. pneumoniae isolates, Mueller-Hinton agar with 5% sheep blood (Remel, Milwaukee, Wis.) was used.

The antibiotics used for MIC determinations and in vivo studies included doxycycline, minocycline, and the experimental glycylcyclines GAR-936 and WAY 152,288 (Wyeth-Ayerst, Wayne, N.J.). Antibiotics were diluted as recommended by the manufacturer. MICs and minimal bactericidal concentrations (MBCs) were diluted by standard microdilution procedures by using geometric twofold serial dilutions in Mueller-Hinton broth and agar, according to the guidelines set forth by the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (7).

Mouse preparation and infection.

Six-week-old, specific-pathogen-free female ICR/Swiss mice (weight, 23 to 25 g) were obtained from Harlan Sprague-Dawley (Madison, Wis.). The mice were rendered neutropenic (<100 neutrophils/μl) by injecting two doses of cyclophosphamide (Mead Johnson Pharmaceuticals, Evansville, Ind.) intraperitoneally 4 days (150 mg/kg) and 1 day (100 mg/kg) before the infection experiment.

Broth cultures of freshly plated bacteria other than pneumococci to be used for thigh muscle infection were grown to the logarithmic phase in Mueller-Hinton broth after overnight incubation in Mueller-Hinton broth at 35°C to an optical density at 580 nm of 0.3 (Spectronic 88; Bausch & Lomb, Rochester, N.J.). After a 1:10 dilution into fresh broth, 0.1 ml (∼106 CFU) was injected into the thighs of ether-anesthetized mice. For pneumococci, the inoculum for infection was prepared by swabbing a blood agar plate with confluent growth and suspending growth from the plate in 8 ml Mueller-Hinton broth after overnight incubation of the blood agar plate at 35°C in 5% CO2.

Antimicrobial treatment.

Mice were treated for 24 h with total doses in the following ranges: GAR-936 and WAY 152,288, 24 to 0.19 mg/kg of body weight/day for the experiments with the strains of S. pneumoniae and 192 to 0.19 mg/kg/day for experiments with all other strains. As reference drugs, doxycycline was used for infections with E. coli ATCC 25922 and minocycline was used for infections with S. pneumoniae ATCC 10813. Dosing regimens were selected by dividing 24-h total doses into individual doses to be administered at 3- to 24-h intervals. This method for determination of the pharmacokinetic parameter that best predicts the antibacterial efficacy has been validated previously (12). Antibiotics were administered subcutaneously in 0.2-ml volumes beginning 2 h after thigh inoculation. Control mice were killed for organism quantification at the following times: just before drug treatment for thigh infection and 24 h after the onset of therapy. To evaluate efficacy at the end of 24 h of therapy, we used two mice (four thighs) for each regimen.

Mouse thighs were removed and homogenized (Polytron tissue homogenizer; Kinematica, Luzern, Switzerland) in 10 ml of saline, serially diluted, and cultured quantitatively. The level of detection of this assay was 100 CFU/thigh. When no organisms were cultured from the thighs, the number of CFU was arbitrarily set at 100 for further calculations.

Efficacy was calculated by subtracting the mean log10 CFU per thigh for each treated mouse at the end of therapy from the mean log10 CFU per thigh for control mice at the end of therapy (24 h).

A slightly different treatment protocol was followed for a separate group of mice. Mice were divided into groups of five mice each. The mice were infected with S. pneumoniae ATCC 10813 as described above. In order to compare the results after 24 h of therapy with those after longer durations of therapy, this group of mice was treated for 5 days with GAR-936, with survival instead of number of CFU per thigh used as an endpoint. The dosages of GAR-936 used for this experiment were 0.084, 0.375, 1.5, and 6 mg/kg every 12 h.

Determination of in vivo PAE.

The postantibiotic effects (PAEs) of the glycylcyclines against S. pneumoniae ATCC 10813 and E. coli ATCC 25922 in vivo were determined by the method described by Vogelman et al. (13). The dose of the glycylcyclines used for this study was 3 mg/kg for mice infected with one of these two bacteria.

Drug kinetics.

Single-dose pharmacokinetic studies were performed with sera from thigh-infected mice with the following doses of GAR-936 and WAY 152,288: 48, 12, and 3 mg/kg. After administration of a single dose of the drug, the pharmacokinetics in serum were determined for a group of 18 mice. At consecutive time points between 15 min and 7 h (0.25, 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7 h) after administration of the antimicrobial agent, some of the mice were killed by exposure to 100% CO2. Blood samples were taken by cardiac puncture and were centrifuged at 1,500 × g for 10 min at room temperature, and the serum was removed; the drug concentration in the serum was then measured by a microbiological assay with Bacillus cereus as the test strain. The level of detection of this assay was 0.06 μg/ml. The correlation coefficient for this assay was higher than 0.995 on all occasions.

Pharmacokinetic constants (elimination rate constant [ke1], half-life [t1/2], maximum concentration [Cmax], apparent volume of distribution, and area under the concentration-time curve [AUC]) were calculated by using a one-compartment model with zero-order absorption and first-order elimination via nonlinear least-squares techniques. The AUC was determined by the trapezoidal rule. Steady-state times above the MIC were calculated with Excel97 (Microsoft, Redmond, Wash.). Pharmacokinetic constants were interpolated from values obtained in the actual studies for doses for which no kinetics were determined.

Statistical analysis.

A sigmoid dose-effect model (Emax model) was used to evaluate the impact of the dosing interval on efficacy. The model is described by the equation

|

1 |

where E is the observed effect (the difference in log CFU per thigh compared with that for controls at 24 h), D is the cumulative 24-h dose, Emax is a measure of relative efficacy indicated by the maximum antimicrobial efficacy attributable to the drug, ED50 is a measure of potency indicated by the dose that produces 50% Emax, and n is a function that describes the slope (4, 6, 11). All three parameters of the equation (Emax, ED50, and n) were calculated by using nonlinear least-squares regression techniques (Sigmastat; Jandel, San Rafael, Calif.).

To allow a more meaningful comparison of efficacy between antimicrobial agents, we calculated the dose of each antibiotic required to achieve no growth at 24 h compared with the numbers of CFU at the start of therapy by deriving the following equation from equation 1:

|

2 |

where E equals the difference between log10 CFU at the start of treatment and log10 CFU after 24 h in untreated mice. The calculated dose was called the bacteriostatic dose (BD).

In order to determine pharmacokinetic parameter-effect relations the pharmacokinetic parameters studied (log10 peak level in serum, log10 AUC, and duration of time that levels in serum exceeded a threshold concentration) were correlated with efficacy by using univariate nonlinear regression analysis (Sigmastat) as described previously (12). The log transformations of AUC and Cmax are required because in this way the observations follow a normal distribution.

RESULTS

In vitro studies.

Table 1 lists the organisms used and their susceptibilities to GAR-936, WAY 152,288, and minocycline. The MICs of GAR-936 and WAY 152,288 varied 30-fold, from 0.03 to 0.06 μg/ml for some strains of S. pneumoniae to 0.5 to 1 μg/ml for K. pneumoniae ATCC 43816 and S. aureus. The MBCs were usually 1 to 2 dilutions higher than the MICs except for those for K. pneumoniae ATCC 43816 and E. coli 894.

TABLE 1.

Organisms used and in vitro susceptibilities to GAR-936, WAY 152,288, and minocycline

| Organism | GAR-936

|

WAY 152,288

|

Minocycline

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIC (μg/ml) | MBC (μg/ml) | MIC (μg/ml) | MBC (μg/ml) | MIC (μg/ml) | MBC (μg/ml) | |

| S. pneumoniae ATCC 10813 | 0.12 | 0.25 | 0.12 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.5 |

| S. pneumoniae ATCC 49619 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.06 |

| S. pneumoniae 1199 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 4 | 8 |

| S. pneumoniae 1020 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 4 | 8 |

| S. pneumoniae 1293 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 4 | 8 |

| S. pneumoniae 1396 | 0.12 | 0.5 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 4 | 4 |

| S. aureus ATCC 25923 | 0.12 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.12 | ≥0.5 |

| S. aureus ATCC 33591 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 | 8 |

| S. aureus ATCC 29213 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.12 | 0.5 | 0.06 | ≥0.25 |

| S. aureus WIS-2 | 0.25 | 1 | 0.25 | 1 | 0.06 | ≥0.25 |

| E. coli ATCC 25922 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 |

| E. coli 894 | 0.12 | >8 | 0.25 | >8 | 8 | 8 |

| K. pneumoniae ATCC 43816 | 0.5 | >32 | 0.5 | >32 | 4 | 32 |

Pharmacokinetic studies.

Elimination t1/2s, Cmaxs, and AUCs for the three doses of the glycylcyclines are shown in Table 2. The pharmacokinetics were described by a one-compartment model due to the rapid absorption of the drug. The pharmacokinetics of both drugs appeared to be nonlinear, resulting in a higher apparent elimination t1/2 at a dose of 48 mg/kg.

TABLE 2.

Pharmacokinetic properties of the glycylcyclines in neutropenic mice infected with S. pneumoniae ATCC 10813

| Parameter | GAR-936 at dose (mg/kg) of:

|

WAY 152,288 at dose (mg/kg) of:

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 48 | 12 | 3 | 48 | 12 | 3 | |

| Cmax (μg/ml) | 11.1 | 2.5 | 0.42 | 8.6 | 4.6 | 0.8 |

| AUC0–∞a (μg · h/ml) | 36.5 | 8.07 | 0.68 | 38.6 | 12.0 | 2.08 |

| Elimination t1/2 (h) | 2.34 | 1.98 | 1.05 | 3.36 | 1.93 | 1.65 |

| Tmaxb (h) | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.25 |

AUC0–∞, AUC from time of administration to infinity.

Tmax, time after administration at which Cmax is reached.

Quantification of organisms.

Upon initiation of therapy, the mean log10 number of organisms in the thigh was 6.84 (standard deviation [SD], 0.38; median, 6.83; range, 6.29 to 7.92). After 24 h, the mean log10 number of organisms in control animals was 8.99 (SD, 0.56; median, 8.90; range, 7.82 to 9.97). Organisms in control animals grew by, on average, 2.16 log10 CFU/thigh (SD, 0.62 log10 CFU/thigh; median, 1.94 log10 CFU/thigh; range, 1.34 to 3.28 log10 CFU/thigh). Death occurred at 18 to 24 h after infection in most of the control animals infected with S. pneumoniae ATCC 10813 and K. pneumoniae ATCC 43816. Also, the thigh muscles of the deceased animals were used for quantitative cultures.

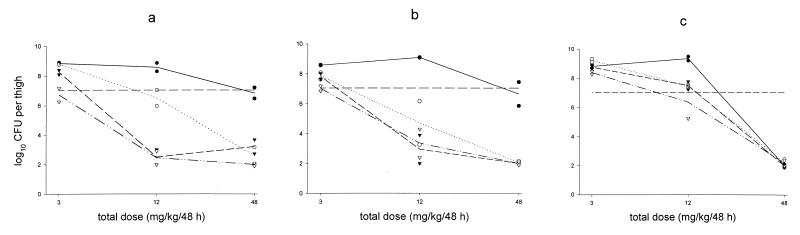

The reference drug doxycycline showed very little activity against experimental infections with E. coli ATCC 25922. With doses up to 40 mg/kg/day, the effect was less than bacteriostatic (data not shown). Minocycline was more effective against experimental infections with S. pneumoniae ATCC 10813. It had a maximum effect similar to that of the glycylcyclines (change of 7.3 log10 CFU), with an ED50 of 8.5 mg/kg/day. In a 48-h experiment in which the efficacies of GAR-936, WAY 152,288, and minocycline were compared, it was shown that the efficacies of GAR-936 and WAY 152,288 were dependent on the frequency of dosing, whereas with minocycline the total dose of the drug appeared to correlate better with efficacy (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Effects of various GAR-936 (a), WAY 152,288 (b), and minocycline (c) dosage regimens on the number of S. pneumoniae ATCC 10813 organisms in the neutropenic mouse thigh muscle infection model after 48 h of treatment. The dashed horizontal line represents the number of CFU per thigh at the start of treatment. ●, single dose; ○, once-daily dose; ▾, twice-daily dose; ▿, four-times-daily dose; ——, single dose; ······, once-daily dose; –––, twice-daily dose; —··, four-times-daily dose; —–, log CFU at start of treatment.

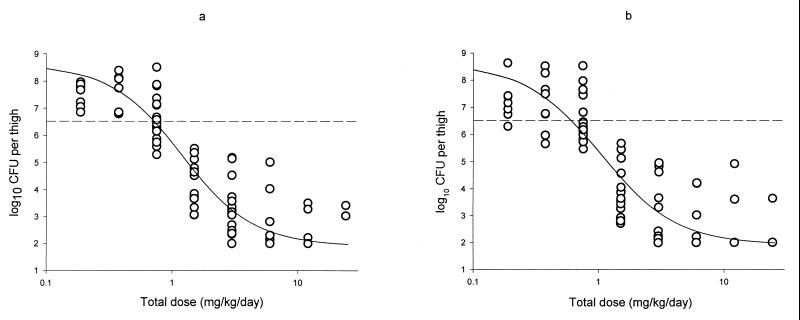

The dose-effect relationships of GAR-936 and WAY 152,288 against S. pneumoniae 1199 are shown in Fig. 2. As can be seen from Fig. 2, the two drugs behaved similarly pharmacodynamically, with comparable Emaxs and ED50s. The results of the dose-effect relationships of the glycylcyclines for the various organisms are shown in Table 3. It can be seen from Table 3 that the glycylcyclines were most effective against the various strains of S. pneumoniae, both tetracycline-sensitive and tetracycline-resistant strains, with bacteriostatic doses ranging from 0.8 to 5.9 mg/kg/day. Bacteriostatic doses for E. coli and S. aureus strains were up to 25-fold higher than those for S. pneumoniae (range, 4.3 to 23 mg/kg/day). The glycylcyclines were only marginally effective against K. pneumoniae ATCC 43816, with bacteriostatic doses ranging from 65 to 151 mg/kg/day.

FIG. 2.

Dose-effect relationship of the glycylcyclines GAR-936 (a) and WAY 152,288 (b) in an experimental thigh muscle infection with S. pneumoniae 1199 in neutropenic mice. Each point represents the results for a single mouse. The sigmoid curve represents the dose-effect curve established according to the Hill equation.

TABLE 3.

Dose-effect relationship of the glycylcyclines against various organisms, using a twice-daily dosing regimen

| Strain | Drug | Emaxa | ED50 (mg/kg/day) | BD (mg/kg/day) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. pneumoniae | ||||

| ATCC 10813 | GAR-936 | 7.3 | 1.6 | 1.4 |

| WAY 152,288 | 7.3 | 1.9 | 1.6 | |

| ATCC 49619 | GAR-936 | 5.0 | 1.7 | 2.0 |

| WAY 152,288 | 5.0 | 1.4 | 1.7 | |

| 1199 | GAR-936 | 6.6 | 1.1 | 0.8 |

| WAY 152,288 | 6.6 | 1.0 | 0.7 | |

| 1020 | GAR-936 | 5.3 | 2.3 | 2.6 |

| WAY 152,288 | 5.3 | 2.2 | 2.4 | |

| 1293 | GAR-936 | 6.8 | 3.5 | 3.0 |

| WAY 152,288 | 6.8 | 2.9 | 2.5 | |

| 1396 | GAR-936 | 6.2 | 9.6 | 5.9 |

| WAY 152,288 | 6.2 | 3.1 | 2.8 | |

| S. aureus | ||||

| ATCC 25923 | GAR-936 | 3.1 | 4.0 | 7.2 |

| WAY 152,288 | 3.5 | 4.0 | 4.3 | |

| ATCC 33591 | GAR-936 | 4.9 | 33 | 23 |

| WAY 152,288 | 5.6 | 39 | 23 | |

| ATCC 29213 | GAR-936 | 3.9 | 25 | 19 |

| WAY 152,288 | 4.4 | 22 | 12 | |

| WIS-2 | GAR-936 | 3.6 | 41 | 23 |

| WAY 152,288 | 3.2 | 26 | 16 | |

| E. coli | ||||

| ATCC 25922 | GAR-936 | 5.5 | 11 | 11 |

| WAY 152,288 | 5.5 | 11 | 6.2 | |

| 894 | GAR-936 | 5.3 | 5.8 | 7.5 |

| WAY 152,288 | 5.3 | 12 | 14 | |

| K. pneumoniae | ||||

| ATCC 43816 | GAR-936 | 4.4 | 115 | 151 |

| WAY 152,288 | 4.4 | 48 | 82 |

Emax is expressed as the log10 difference in numbers between control animals and treated animals.

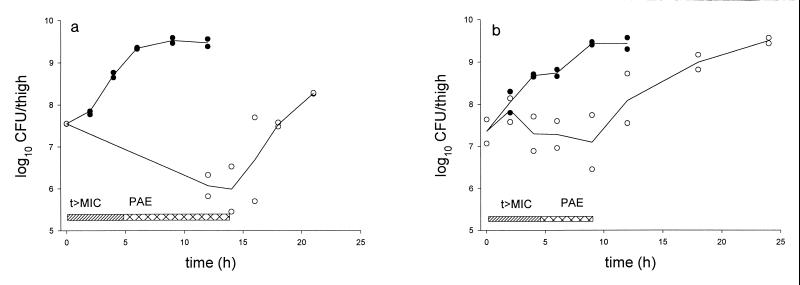

In the experiments for determination of the in vivo PAEs of the glycylcyclines at a dose of 3 mg/kg, GAR-936 exhibited PAEs of 8.9 and 4.9 h against S. pneumoniae ATCC 10813 and E. coli ATCC 25922, respectively, whereas WAY 152,288 exhibited PAEs against the two strains of 6.7 and 5.4 h, respectively. The PAE of GAR-936 against both organisms is depicted in Fig. 3. The maximum killing caused by this dose of GAR-936 was 1.6 log10 CFU for S. pneumoniae ATCC 10813 and 0.1 log10 CFU for E. coli ATCC 25922, whereas for WAY 152,288 these numbers were 2.0 and 0.5 log10 CFU, respectively.

FIG. 3.

In vivo PAE of GAR-936 after administration of 3 mg/kg subcutaneously to neutropenic mice infected with S. pneumoniae ATCC 10813 (a) and E. coli ATCC 25922 (b). t>MIC, period when an active concentration of GAR-936 is present; ●, untreated mice; ○, GAR-936-treated mice.

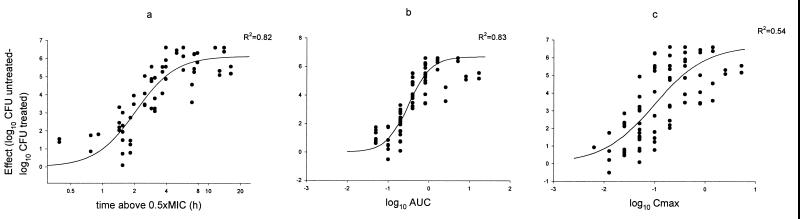

Correlation of pharmacokinetic parameters with efficacy.

An example of the evaluation of pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic parameters is shown in Fig. 4 for GAR-936 and S. pneumoniae 1199. The results of the studies for pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic parameters for each organism-drug combination are shown in Table 4. The pharmacokinetic parameter that correlated best with efficacy was the time above a certain factor times the MIC for five of the six organism-drug combinations studied. The magnitude of this factor varied from 0.5 to 4. The only exception to this observation was the combination of GAR-936 and S. pneumoniae 1199, for which both AUC and time above the MIC were important in predicting outcome (R2 = 0.83 and 0.82, respectively).

FIG. 4.

Relationship between pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic parameters and therapeutic efficacy of GAR-936 (free drug) against S. pneumoniae 1199 in the neutropenic mouse thigh muscle infection model (R2 = 0.82, 0.83, and 0.54 for panels a, b, and c, respectively). (a) time above the 0.5 × MIC versus effect. (b) Log AUC versus effect. (c) Log Cmax versus effect.

TABLE 4.

Nonlinear regression analysis of the results of the experimental thigh muscle infection on predictors of drug efficacya

| Microorganism | Drug | Parameter | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| S. pneumoniae 1199 | GAR-936 | AUC | 0.83 |

| S. pneumoniae 1199 | GAR-936 | Time above MIC | 0.82 |

| S. pneumoniae 1199 | WAY 152,288 | AUC | 0.77 |

| S. pneumoniae 1199 | WAY 152,288 | Time above 0.5× the MIC | 0.86 |

| E. coli ATCC 25922 | GAR-936 | AUC | 0.80 |

| E. coli ATCC 25922 | GAR-936 | Time above 0.5× the MIC | 0.93 |

| E. coli ATCC 25922 | WAY 152,288 | AUC | 0.56 |

| E. coli ATCC 25922 | WAY 152,288 | Time above 4× the MIC | 0.91 |

| K. pneumoniae ATCC 43816 | GAR-936 | AUC | 0.73 |

| K. pneumoniae ATCC 43816 | GAR-936 | Time above MIC | 0.76 |

| K. pneumoniae ATCC 43816 | WAY 152,288 | AUC | 0.83 |

| K. pneumoniae ATCC 43816 | WAY 152,288 | Time above MIC | 0.84 |

The predictors of drug efficacy were time that levels exceeded a certain fraction of the MIC and AUC.

Since maximum therapeutic efficacy can be expected if more than 80% of the Emax is achieved, we calculated the times above the MIC required to achieve this percentage of Emax. It appeared that for S. pneumoniae 1199, E. coli ATCC 25922, and K. pneumoniae ATCC 43816, the concentration of unbound drug in serum should be maintained above the MIC for at least 50% of the time for GAR-936 and for at least 75% of the time for WAY 152,288.

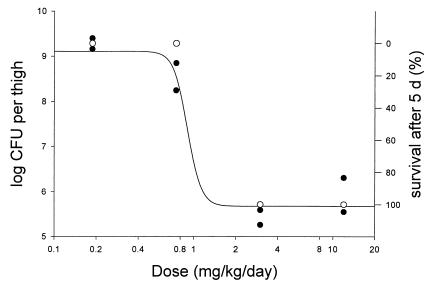

Survival studies.

The results of the experiments on the effect of prolonged treatment with GAR-936 on survival of mice with a thigh muscle infection caused by S. pneumoniae ATCC 10813 is shown in Fig. 5. In the same experiment a separate group of two mice was used for determination of the bacterial counts in the thigh. All untreated infected mice died within 24 h. Figure 5 therefore shows the relation between the effect on the numbers of bacteria in the thigh muscle after 24 h of therapy and survival.

FIG. 5.

Relation between effect of GAR-936 on number of CFU in the thigh after 24 h of therapy in a thigh muscle infection caused by S. pneumoniae ATCC 10813 in neutropenic mice and percent survival after 5 days (2) of treatment. The sigmoid curve represents the dose-effect curve according to the Hill equation. ●, mice for which the effect on the number of CFU was established; each point in the curve represents an individual mouse; ○, mice for which the survival percentage was established (five mice per group).

DISCUSSION

The glycylcyclines are derivatives of the tetracycline antimicrobial drug minocycline. The early glycylcyclines N,N-dimethylglycylamido-9-aminominocycline and 9-amino-6-demethyl-6-deoxytetracycline exhibited potent activity against many gram-positive and gram-negative aerobic and anaerobic bacteria (reviewed by Tally et al. [9]). It was especially encouraging that the early glycylcyclines were active in vitro against tetracycline-resistant bacteria due to efflux-based as well as ribosomal protection mechanisms of resistance. However, there are as yet no published in vitro data on the activities of GAR-936 and WAY 152,288 against large recent collections of bacteria.

The present study extends the early in vitro findings to the in vivo situation against minocycline-sensitive and -resistant bacteria. The present study shows that the glycylcyclines exhibited the most potent in vivo activities against isolates of S. pneumoniae, less potent activity against isolates of E. coli and S. aureus, and the least potent activity against an isolate of K. pneumoniae.

The activities against isolates of S. aureus are particularly noteworthy, because a relatively high Emax of 3.1 to 5.6 was achieved. This amounts to 1.2 to 3.0 log10 killing which is lower than what we previously achieved with beta-lactam antibiotics but higher than what was achieved with glycopeptides (unpublished data). Our findings are underscored by the results of Weiss et al. (W. J. Weiss, T. M. Murphy, S. M. Mikels, and J. Clegg, Abstr. 38th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. F-136, p. 267, 1998), who showed that GAR-936 at a twice-daily dose above 1 mg/kg showed efficacy superior to that of vancomycin at a twice-daily dose of 20 mg/kg in a rat model of endocarditis. Therefore, GAR-936 and WAY 152,288 are promising drugs for the treatment of staphylococcal infections.

The results of the present study show that both glycylcyclines exhibit time-dependent antimicrobial activity in vivo. However, due to the relatively long t1/2 and the long PAE, the AUC was also reasonably predictive, with slightly lower R2 values. The pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic analysis was hampered somewhat by the nonlinearity of the pharmacokinetics of both glycylcyclines. This is especially important for the lower doses, for which the pharmacokinetic parameters had to be extrapolated.

Preliminary results from pharmacokinetic studies of GAR-936 with volunteers have recently been published (G. Muralidharan, J. Getsy, P. Mayer, I. Paty, M. Micalizzi, J. Speth, B. Wester, and P. Mojaverian, Abstr. 39th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. F-416, p. 303, 1999). In contrast to our data for mice, the pharmacokinetics of GAR-936 in healthy volunteers were linear. After administration of an intravenous dose of 300 mg, the Cmax was 2.8 μg/ml, the volume of distribution was >10 liters/kg, and the terminal t1/2 was 36 h. The results of the present study indicate that in order to reach maximum efficacy, the time above a certain threshold concentration is the main parameter that should be taken into account. The t1/2 of GAR-936 in humans is long enough to support once-daily dosing. For maximum efficacy, effective concentrations should be maintained for 50 to 75% of the time. If 4× the MIC is taken as the target concentration, then a single intravenous dose of 300 mg achieves a concentration above 2 μg/ml 75% of the time. The theoretical breakpoint MIC would therefore be about 0.5 μg/ml. The exact optimal dosage schedule for treatment of infections in humans and the determination of susceptibility breakpoints can be given only after more pharmacokinetic and clinical data for these drugs in humans have become available.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by a grant from Wyeth-Ayerst Research, Pearl River, N.Y.

REFERENCES

- 1.Eliopoulos G M, Wennersten C B, Cole G, Moellering R C. In vitro activities of two glycylcyclines against gram-positive bacteria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38:534–541. doi: 10.1128/aac.38.3.534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goldstein F W, Kitzis M D, Acar J F. N,N-Dimethylglycyl-amido derivative of minocycline and 6-demethyl-6-desoxytetracycline, two new glycylcyclines highly effective against tetracycline-resistant gram-positive cocci. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38:2218–2220. doi: 10.1128/aac.38.9.2218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hamilton-Miller J M T, Shah S. Activity of glycylcyclines CL 329998 and CL 331002 against minocycline-resistant and other strains of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1996;37:1171–1175. doi: 10.1093/jac/37.6.1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holford N H G, Sheiner L B. Understanding the dose-effect relationship: clinical application of pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic models. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1981;6:429–453. doi: 10.2165/00003088-198106060-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kenny G E, Cartwright F D. Susceptibilities of Mycoplasma hominis, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, and Ureaplasma urealyticum to new glycylcyclines in comparison with those to older tetracyclines. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38:2628–2632. doi: 10.1128/aac.38.11.2628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leggett J E, Fantin B, Ebert S, Totsuka K, Vogelman B, Calame W, Mattie H, Craig W A. Comparative antibiotic dose-effect relations at several dosing intervals in murine pneumonitis and thigh-infection models. J Infect Dis. 1989;159:281–292. doi: 10.1093/infdis/159.2.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests that grow aerobically. 3rd ed. 1993. Approved standard. NCCLS document M7-A3. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, Pa. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nord C E, Lindmark A, Persson I. In vitro activity of DMG-MINO and DMG-DMDOT, two new glycylcyclines, against anaerobic bacteria. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1993;12:784–786. doi: 10.1007/BF02098471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tally F T, Ellestad G A, Testa R T. Glycylcyclines: a new generation of tetracyclines. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1995;35:449–452. doi: 10.1093/jac/35.4.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Testa R T, Petersen P J, Jacobus N V, Sum P E, Lee V J, Tally F P. In vitro and in vivo antibacterial activities of the glycylcyclines, a new class of semisynthetic tetracyclines. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:2270–2277. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.11.2270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Unadkat J D, Bartha F, Sheiner L F B. Simultaneous modeling of pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics with non-parametric kinetic and dynamic models. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1986;40:86–93. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1986.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vogelman B, Gudmundsson S, Leggett J, Turnidge J, Ebert S, Craig W A. Correlation of antimicrobial pharmacokinetic parameters with therapeutic efficacy in an animal model. J Infect Dis. 1988;158:831–847. doi: 10.1093/infdis/158.4.831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vogelman B, Gudmundsson S, Turnidge J, Leggett J, Craig W A. In vivo postantibiotic effect in a thigh infection in neutropenic mice. J Infect Dis. 1988;157:287–298. doi: 10.1093/infdis/157.2.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wexler H M, Molitoris E, Finegold S M. In vitro activities of two new glycylcyclines, N,N-dimethylglycyl-amido derivatives of minocycline and 6-demethyl-6-deoxytetracycline against 339 strains of anaerobic bacteria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38:2513–2515. doi: 10.1128/aac.38.10.2513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wise R, Andrews J M. The in vitro activities of two glycylcyclines. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38:1096–1102. doi: 10.1128/aac.38.5.1096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]