Abstract

Background

Cardiac injury has been linked to a poor prognosis during COVID-19 disease. Nevertheless, the risk factors associated are yet to be thoroughly investigated.

Objectives

We sought to compare demographical characteristics and in-hospital outcomes in patients infected by the SARS-CoV-2 with and without cardiac injury, to further investigate the prevalence of acute cardiac injury as well as its impact on their outcomes in COVID-19-patients.

Methods

We included in a retrospective analysis, all COVID-19 patients admitted between October first and December first, 2020, at the University Hospital Center of Oujda (Morocco) who underwent a troponin assay which was systematically measured on admission. The study population was divided into two groups: cardiac-injured patients and those without cardiac injury. Clinical, biological data and in-hospital outcomes were compared between the two groups.

Results

298 confirmed COVID-19 cases were included. Our study found that compared to non-cardiac-injured, cardiac-injured patients are older, with higher possibilities of existing comorbidities including hypertension (68 [42.2%] vs 40 [29.2%], P = 0.02), diabetes (81 [50.3%] vs 53 [38.7%] P = 0.044), the need for mechanical ventilation, ICU admission and mortality. A Cox proportional hazards regression analysis shows a significantly increased risk of death among cardiac-injured COVID-19-patients as compared to non-cardiac injured. (HR, 1.620 [CI 95%: 2.562-1.024])

Conclusion

Our retrospective cohort found that old age, comorbidities, a previous history of CAD, were significantly associated with acute cardiac injury. COVID-19 patients with acute cardiac injury are at a higher risk of ICU admission, and death.

Keywords: COVID-19, cardiology, biomarkers, mortality

Introduction

Cardiovascular complications are well described during the novel coronavirus disease 2019. 1 According to latest guideline, cardiac injury is defined as the elevation of troponin above the 99th percentile. 2 Recently several studies, reported cardiac injury as one of the major's COVID-19 pathogenic features.3–7 Elevated cardiac biomarkers mainly cardiac troponins are described in COVID-19-patients, especially critically ill. 4 In fact, the occurrence of cardiac injury in COVID-19-patients seems to be multifactorial. The exact pathogenesis of myocardial injury induced by the SARS-CoV-2 remains unknown. However, there are some possible mechanisms suggested. These include the myocardial inflammation and damage due to the invasion of the SARS-cov2 by binding to angiotensin converting enzyme-2 receptors. Besides, an indirect myocardial injury could be due to the increase of inflammatory cytokines TNF-α production secondary to the downregulation of ACE-2 by SARS-CoV2 infection and may alter the cardioprotective effects of angiotensin 1-7.8,9 Indeed, Cardiac injury is one of the causes of mortality and morbidity among COVID-19-patients.1,10] However, its exact prevalence remains unknown. Therefore, we sought to compare characteristics and outcomes of hospitalized patients infected by the SARS-CoV-2 with and without cardiac injury, to further investigate the prevalence of acute cardiac injury in COVID-19-patients as well as its impact on their outcomes.

Materials and Methods

Informed consent and approval from the local ethics committee were obtained for this retrospective study.

We included in the final analysis, all COVID-19-confirmed-patients admitted between October first and December first, 2020, presenting to a single center at the University Hospital Center of Oujda (Morocco) who underwent a troponin assay at the time of hospital admission. The troponin level was systematically measured on admission, and the diagnostic of COVID-19 infection was confirmed by a positive SARS-CoV-2 reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction test (RT-PCR).

The study population was divided into two groups: cardiac-injured patients and those without cardiac injury. The diagnostic of cardiac injury was defined according to latest guideline (>99th percentile upper reference). Our central laboratory performed the ultrasensible troponin Ic (CTnI) by using the analyzer automate Architect with a 99th percentile at 26 ng/mL. We excluded cases without high-sensitivity troponin I (hs-TNI).

We collected the demographic characteristics, clinical data, laboratory findings including cardiac biomarker (hs-TNI) measured on admission were collected. The radiologic assessment was performed by a computed tomography and we defined severe disease as >50% of lung parenchyma affected by COVID-19. The categorization as ICU-patient (intensive care unit) defined as patient who is admitted to the ICU at any time during hospitalization (directly or after clinical worsening in the ward) or ward-patient, the need for mechanical ventilation and the mortality were compared between the two groups.

Statistical Software SPSS version 21 was used for the statistical analysis. The study population was divided into two groups: cardiac-injured patients and non-cardiac injured patients. The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to assess the normal distribution of quantitative variables. We used non-parametric tests to analyze non-normally distributed variables expressed as median with interquartile range (IQR) while we normally distributed continuous variables were analyzed with the unpaired Student's t test and expressed as mean and standard deviation. Finally, we expressed categorical variables as frequency and percentages, the Pearson Chi Square test of Fisher's Exact test was used for the comparison between the two groups. Logistic regression analysis was performed to assess risk factors for cardiac Injury. A Cox proportional hazards regression analysis was also performed to determine factors associated with mortality. A two-tailed value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Study Population

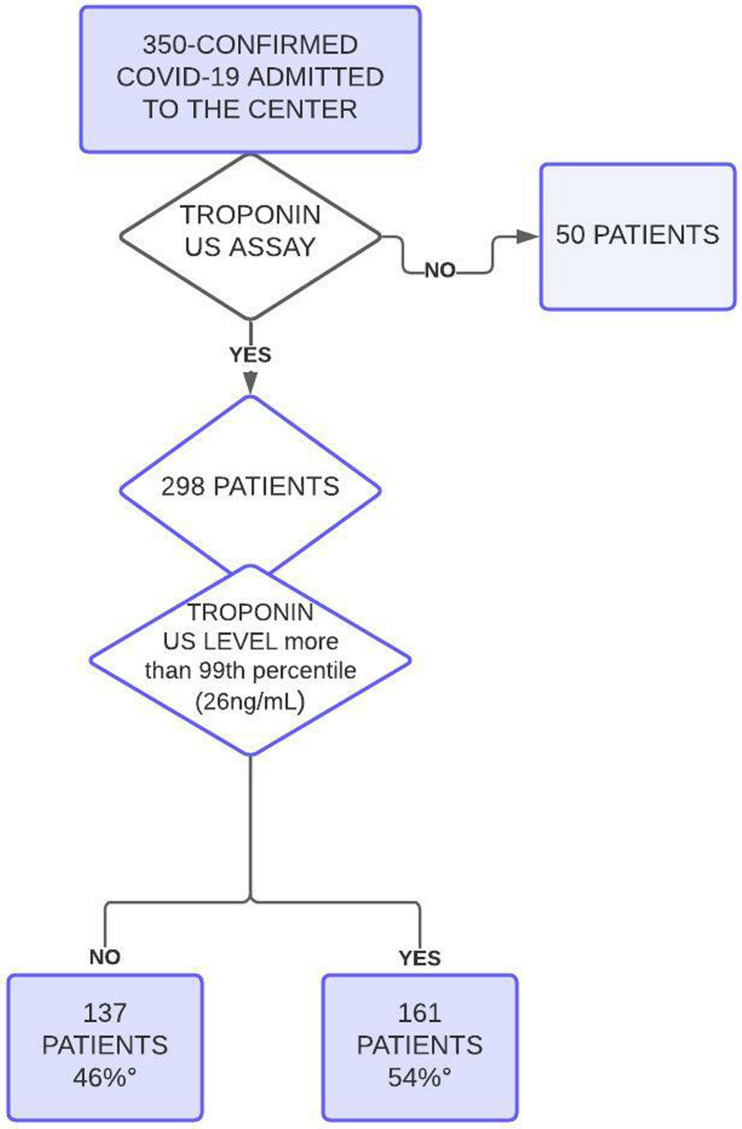

Three hundred and fifty (350) Confirmed COVID-19 patients were admitted to the center during this period and 298 underwent a troponin us assay from admission representing the final analysis sample divided into two groups: cardiac-injured patients were 161 patients (54%) and non-cardiac-injured were 137 patients (46%). A flow chart reporting numbers of individuals at each stage of study is represented in the Figure 1.

Figure 1.

A flow chart reporting numbers of individuals at each stage of study.

The mean age was 64.95 (SD 13.60) years and 182 (61.04%) were male. Common symptoms include fever (290 patients [97.31%]), cough, shortness of breath, were present in 273 patients (91.61%). Diarrhea (patients 26[8.72%]), chest pain (54 patients [18.12%]), and headache (50 patients [16.77%]), Hypertension (108 patients [36.2%]), diabetes (134 patients [45%]), and obesity (29 [10.9%] were the most common coexisting comorbidities. (Table 1)

Table 1.

Demographical characteristics and in-hospital outcomes of COVID-19 of the study population.

| Whole population N = 298 | Non-Cardiac injury N = 137 (46%) |

Cardiac injury n = 161 (54%) |

P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 64,95 (SD 13,60) | 62,04 (SD 13,63) | 67,34 (SD 13,1) | 0002* |

| Gender n (%) | ||||

| Males | 182 (61.04%) | 90 (65.69%) | (57.14%) | 0.366 |

| Females | 116 (37.6%) | 47 (34.30%) | 69 (42.85%) | |

| Hypertension n (%) | 108 (36.24%) | 40 (29.2%) | 68 (42.23%) | 0.02* |

| Smocking n (%) | 21 (7%) | 9 (6.5%) | 13 (8.1%) | 0.766 |

| Dyslipidemia n (%) | 18 (6%) | 9 (6.5%) | 9 (5.6%) | 0.579 |

| Diabetes n (%) | 134 (45%) | 53 (38.7%) | 81 (50.31%) | 0.044* |

| Previous history of CAD | 30 (10.1%) | 8 (5.8%) | 22 (13.7%) | 0.025* |

| Body Mass Index (BMI) kg/m2 | 25.60 (IQR 27.67-24) | 25 (IQR 27-24) | 26 (IQR 27.85-24) | 0.465 |

| Systolic pressure (mm hg) | 132 (IQR 145-120) | 130 (140-120) | 135 (IQR 147-120) | 0.894 |

| Oxygen saturation (%) | 80 (IQR 88.5-67) | 82 (IQR 90-75) | 75 (85-62) | 0.017* |

| Service of admission n (%) ICU Conventional wards |

224 (75.2%) 74 (24.8%) |

82(59.9%) 55 (40.1%) |

142 (88.2%) 19 (11.8%) |

<0.001* |

| Mechanical ventilation n (%) | 121 (44%) | 30 (21.9%) | 91 (56.5%) | 0.028* |

| Mortality n (%) | 134 (45%) | 32 (23.4%) | 102 (63.4%) | <0.001* |

| In-hospital stay (days) | 9 (IQR 13.5-5) | 8 (IQR 11-5) | 10 (IQR 15-5) | 0.077 |

ICU : intensive care unit

IQR : Interquartile Range

SD : Standard Deviation

CAD : coronary artery disease

Regarding clinical and demographical characteristics, cardiac-injured patients compared to non-cardiac-injured were older (mean [SD] age, [67.34 (SD 13.1) years versus 62.04 (SD 13.63) years)] years; P = 0.002), and more likely to have a coronary artery disease (CAD) (22 [13.7%] vs 8 [5.8%], P 0.025). However, there was no statistically significant difference for chest pain in patients with and without acute cardiac injury [21.73%] versus [10.94%], P = 0.078). Moreover, comorbidities, including hypertension (68 [42.2%] vs 40 [29.2%], P = 0.02), diabetes (81 [50.3%] vs 53 [38.7%] P = 0.044), were prevalent among cardiac-injured patients with COVID-19. (Table 1)

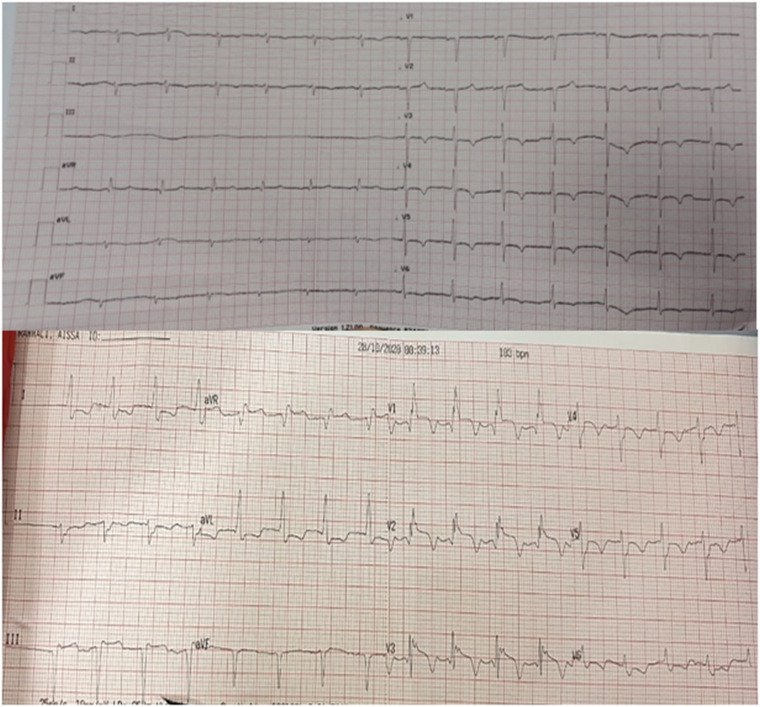

Among patients with acute cardiac injury, 24.3% underwent an electrocardiogram (EKG) after admission. This small number of EKG founded could be explained by the retrospective form of the study. Myocardial ischemia signs such as T-wave inversion and ST-segment depression were found. Figure 2 Illustrates the EKG of 2 patients with acute cardiac injury.

Figure 2.

Electrocardiogram (EKG) of two patients with acute cardiac injury.

Laboratory Findings

Regarding biological findings, cardiac-injured patients compared with non-cardiac-injured showed higher levels of hs-TNI: median (IQR) [116 (IQR 611-55.10)] versus 8 (IQR 15.35-3.36)]ng/L, N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP): median (IQR) [1541 (IQR 6411.5-749) versus 242.5 (IQR 407.57-80)] unite; C-reactive protein: mean (SD) [ 201.87 (SD 95.59) versus 159,01 (SD 99.24)] mg/L; D-dimers: median (IQR) [2.77 (IQR 13.66-0.67) versus 0.58 (IQR 3.35-0.245)], (all P < 0.001).

Otherwise, fibrinogen mean (SD) [5.69 (SD 2.04) versus 6.35 (SD 1.78)] P = 0.003)] g/L, lymphocytes cells median (IQR) [0.745.103 (IQR 1.13.103-0.51.103)] versus 0.87.103 (IQR 1.325.103-0.59.103) P = 0.024] were lower but platelets count: mean (SD) [250.45.103 (SD 244.21.103) versus 299.817.103 (SD 331.325.103), P = 0.006/0.153] were comparable between the two groups. The complete laboratory findings are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Biological characteristics of the study population.

| Whole population N = 298 | Non-Cardiac injury N = 137 (46%) | Cardiac injury n = 161 (54%) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| D-Dimer (ng/ml) | 1.23 (IQR 7.29-0.37) | 058 (IQR 3.35-0.245) | 2.77 (IQR 13.66-0.67) | <0.001 |

| Lactate Dehydrogenase (U/L) | 631 (IQR 872-413.5) | 523 (IQR 759.5-357.5) | 7495 (IQR 1003.75-496.5) | <0001 |

| Prothrombin time (%) | 71 (IQR 82-63) | 74 (IQR 85.5-68.5) | 68 (IQR 76-58.25) | <0.001 |

| Cephalin activated time | 1.08 (IQR 1.28-1) | 1.04 (IQR 1.17-1) | 1.14 (IQR 1.36-1) | <0.001 |

| International Normalized Ratio (INR) | 1.19 (IQR 1.28-1.09) | 1.16 (IQR 1.22-1.08) | 1.21 (IQR 1.33-1.14) | <0.001 |

| Fibrinogen (g/L) | 5.99 (SD 1.95) | 6.35 (SD 1.78) | 5.69 (SD 2.04) | 0.003 |

| White blood cells (elements/mm3) | 11.58.103 (IQR 16.41.103-7.91.103)) | 912.103 (IQR14.69.103-6,5.103) | 13.845.103 (18.495.103-9.5.103) | <0001 |

| Platelets cells (elements/mm3) | 273.93.103 (SD 288.013.103) | 299.817.103(SD 331.325.103) | 250.45.103 (SD 244.21.103) | 0.006 |

| Lymphocytes cells (elements/mm3) | 0,8.103(IQR 1,23.103-0,54.103) | 0,87.103(IQR 1325.103-0,59.103) | 0745.103(IQR 1,13.103-0,51.103) | 0024 |

| Ferritin (ng/mL) | 843 (IQR 1888-474) | 687 (IQR 1495,23-397) | 1185 (IQR 2515-565) | <0001 |

| Troponin us (ng/L) | 33 (IQR 141-8.75) | 8 (IQR 15.35-336) | 116 (IQR 611-55.10) | <0001 |

| Pro-BNP (pg/mL) | 825 (IQR 3162-232) | 2425 (IQR 407.57-80) | 1541 (IQR 6411.5-749) | <0001 |

| Urea (g/L) | 0,46 (IQR 0,75-0,34) | 0,38 (IQR 0.52-0.25) | 0.60 (IQR 1.11-0.41) | <0001 |

| Creatinine (mg/L) | 9.56 (IQR 13.35-7.24) | 796 (IQR 10.47-6.56) | 11.04 (IQR 19.79-8.16) | <0001 |

| Fast Blood Glucose (g/L) | 1.46 (IQR 207-112) | 1.32 (IQR 2.05-1.02) | 1.52 (IQR 2.08-1.15) | 0006 |

| C-Reactive Protein (mg/L) | 182 (SD 99.42) | 159.01 (SD 99.24) | 201.87 (SD 95.59) | 0001 |

| Procalcitonin (ng/mL) | 0.31 (IQR 1.2-0.13) | 0.15 (IQR 0.38-0.08) | 0.67 (IQR 3.18-0.26) | <0001 |

Radiological Findings

The overall study population underwent a computed tomography scan (CT). According to the CT scan findings, 206 patients (69.1%) had more than 50% of lung parenchyma affected by the COVID-19 pneumonia. Radiological findings showed that severe disease (>50% of lung parenchyma affected) was more prevalent in cardiac-injured-patients than non-cardiac-injured patients. (75.1% vs 62.1%, P <0.001)

Our main objective was to compare demographical characteristics between cardiac-injured and non-cardiac-injured patients. Of the whole population, a total of 134 patients (45%) died while 164 patients (55%) were discharged. The length of hospital stay was higher in cardiac-injured patients than non-cardiac-injured, but no statistically significant difference was observed: median (IQR) [10 (IQR 15-5) versus [8 (IQR 11-5) P = 0077). Compared with cardiac-injured, non-cardiac-injured patients were associated with intensive care unit admission [142 (88.2%) versus 82 (59.9%), P < 0.001] and required more invasive mechanical ventilation [91 (56.5%) versus 30 (21.9%); P = 0.028]. (Table 1).

Predictors for Cardiac Injury in Patients with COVID-19 Infection

In a multivariable analysis, age [odds ratio (OR), 1,05; 95% confidence interval (CI), 1.022–1.077], previous history of CAD (OR, 4.468; 95% CI, 1.598-12.489), elevated creatinine level at admission (OR, 1068; 95% CI, 1.016-1123) and elevated CRP at admission (OR, 1.004; 95% CI, 1.001-1.008) were found to be significantly associated with acute cardiac injury. Fibrinogen level at admission (OR, 0.742; 95% CI, 0.622-0.886) and admission oxygen saturation (OR, 0.958; 95% CI, 0.936-0.980) was significantly negatively associated with acute cardiac injury. Other background comorbidities were not found to be significantly associated with acute cardiac injury. The complete data regarding predictors acute cardiac injury in COVID-19 patients are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Risk Factors for Cardiac Injury According to Logistic Regression.

| Odds Ratio (OR) (95% CI) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.,05 (1.022-1.077) | <0.001* |

| Oxygen saturation | 0.958 (0.936-0.980) | <0.001* |

| Fibrinogen | 0.742 (0.622-0.886) | 0.001* |

| Creatinin | 1.068 (1.016-1.123) | 0.01* |

| Fast Blood glucose (FBG) | 0.849 (0.592-1.218) | 0.375 |

| C-Reactiv Protein (CRP) | 1.004 (1.001-1.008) | 0.024* |

| Procalcitonin | 1111 (0.994-1.242) | 0.063 |

| D-Dimers | 1.021 (0.993-1.049) | 0.148 |

| Gender | 1.170 (0.616-2.221) | 0.632 |

| Diabetes | 1.195 (0.571-2.501) | 0.635 |

| Hypertension (HTN) | 1069 (0.519-2200) | 0856 |

| Previous history of coronary artery disease (CAD) | 4.468 (1598-12.489) | 0.004* |

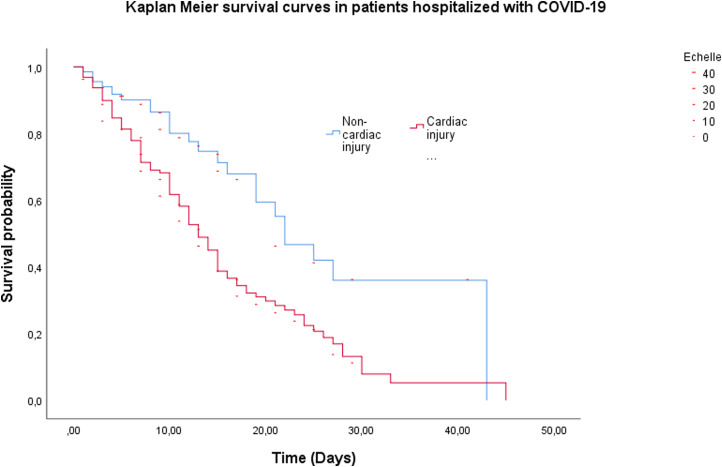

Factors Associated with Mortality

The overall mortality was 45%. The mortality rate was higher in cardiac-injured patients than non-cardiac-injured. (63.4% vs 23.4%, P < .001) (Table 1; Kaplan-Meier survival curves in Figure 3). A Cox proportional hazards regression analysis for the same association, adjusted for age, gender, comorbidities (previous history of CAD, diabetes mellitus, and hypertension), and admission creatinine, CRP and fibrinogen levels is presented in Table 4. The adjusted analysis shows a significantly increased risk of death among cardiac-injured COVID-19-patients as compared to non-cardiac-injured. (HR, 1620 [CI 95%: 2562-1024] P = 0039)

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves for cardiac-injued and non-cardiac-injured hospitalized patients with COVID-19.

Table 4.

Adjusted analysis for the association between cardiac injury and in-hospital mortality, and between acute cardiac injury and the composite of invasive ventilation support in patients hospitalized with COVID-19.

| Mortality | Composite outcomes of invasive ventilation support | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard Ratio (HR) (95% CI) | P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-Value | |

| Age | 1.009 (1.025-0.993) | 0.276 | 1.007 (1.025-0990) | 0.422 |

| Oxygen parameters | 0.989 (0.999-0.979) | 0.040* | 0.988 (0.998-0.977) | 0.019* |

| Systolic blood pressure | 0.994 (1.001-0.987) | 0.076 | 0.994 (1.002-0.986) | 0.132 |

| Acute cardiac injury | 1.620 (2.562-1.024) | 0.039* | 1.668 (2.692-1.033) | 0036* |

| Fibrinogen | 1.028 (1.142-0925) | 0611 | 1.047 (1.174-0.933) | 0435 |

| Creatinin | 1.007(1.017-0.997) | 0.185 | 0.999 (1.011-0.986) | 0829 |

| Fast Blood Glucose | 1.192 (1.501-0.946) | 0.137 | 1.216 (1.546-0.957) | 0.109 |

| C-Reactiv Protein | 1.002 (1.004-1.000) | 0.036* | 1.002 (1.004-0.999) | 0146 |

| Lactate Dehydrogenase | 1.001 (1.001-1.000) | <0.001* | 1.001 (1.001-1.000) | <0.001* |

| Lymphocyte cells | 1 (1.000-1.000) | <0.001* | 1.000 (1.000-1.000) | <0.001* |

| Procalcitonin | 0.993 (1.003-0.983) | 0.187 | 0.995 (1.006-0.984) | 0.414 |

| D-Dimers | 1.005 (1.017-0.993) | 0.419 | 1.004 (1.018-0.990) | 0.568 |

| Gender | 1.312 (1.927-0.893) | 0.167 | 1.498 (2.268-0.990) | 0.056 |

| Diabetes | 1.095 (1.757-0.683) | 0.706 | 0981 (1611-0597) | 0.939 |

| Hypertension | 0.691 (1.059-0.452) | 0090 | 0670 (1051-0427) | 0.081 |

| Previous history of Coronary Artery Disease | 0.674 (1.305-0.348) | 0.242 | 0.655 (1.307-0.328) | 0.230 |

Discussion

While cardiac injury has been linked to a poor prognosis during COVID-19 disease 2019, the risk factors associated have not been fully investigated. We performed a retrospective study of clinical features in patients infected by the SARS-CoV-2, to assess possible risk factors for acute cardiac injury during COVID-19 infection, as well as the patients’ outcomes.

Our study found a cardiac injury involvement of 54% (161/298) which is slightly higher than those reported in the literature.11,12 Indeed, acute cardiac injury in patients infected by the SARS-CoV-2 is more frequent than what was expected at the beginning of the outbreak. The actual incidence reported is slightly higher than the one reported at the beginning of the pandemic. For more explaining, in studies published on February 2020, Wang D et al reported 7.2% of patients developing acute cardiac injury among 138 hospitalized COVID-19-patients, with a prevalence of patients who received intensive care. (22.2%). 1 Consistently, Huang C et al reported approximately 12% of acute cardiac injury in patients infected by the SARS-CoV-2. 13 In a study published on March 2020, 19.7% of patients had cardiac injury. 14 Moreover, recent metanalysis reported in hospitalized patients with COVID-19, a cumulative incidence of acute cardiac injury about 15-24.4%.15,16 This could be explained by many factors including sample sizes and the phases of COVID-19 breakout.

Our COVID-19 retrospective cohort found that cardiac-injured patients are older. Other reports support our findings.1,14,17,18 Besides, old age has been associated with poor outcomes in COVID-19 infection. Although we did not find any association between gender and cardiac injury, other studies reported that male gender was a risk factor for cardiac damage.14,19 In addition, male gender has been previously associated with poor prognosis in COVID-19 patients. 20 However, further studies are needed to assess whether males are more likely to develop acute cardiac injury.

Our study found cardiac-injured patients with higher possibilities of existing comorbidities such as hypertension and diabetes, a previous history of CAD, the need for mechanical ventilation, ICU admission. Other reports support our findings.1,14,17 The possible mechanism is that hypertension-induced cardiac damage is associated with mitochondrial injury, which can be caused by SARS-COV-221,22 we also found that a previous history of CAD was an independent risk factor for cardiac injury. This is consistent with previous reports. 12 Nonetheless, further studies are needed to assess whether CAD or diabetes mellitus were independently associated with higher incidence of cardiac injury in patients infected by the SARS-CoV-2.

Our study revealed in cardiac-injured patients, coagulopathy with higher C-reactive protein, procalcitonin, D-dimer, prothrombin time, INR, blood urea and creatinine, and decrease of platelet counts. These laboratory findings are described in other reports.11–14,23 These results strengthen knowledge about the hypercoagulable state in COVID-19 with cardiac injury.

Recent large metanalysis reported the all-cause mortality of 72,6% (95% confidence interval, 9.21-32.57) in cardiac-injured COVID-19-patients and 14.5% in non-cardiac injured patients. 16 Consistently with previous studies,11–14,23 our study confirmed that cardiac-injured COVID-19-patients had a higher in-hospital mortality rate (63.4%) than those who did not develop cardiac injury (23.4%), (P < 0.001). To assess the implications of cardiac injury, we performed a multivariable Cox regression analysis which revealed that cardiac injury was independently associated with the mortality. (HR, 1.620 [CI 95%: 2.562−1.024]) (Table 4). When we used cardiac injury as a binary variable, it was also found to be an independent predictor for mortality (0.291 [0.600−0.141], P = 0.001). Other predictors such as oxygen parameter, LDH were also associated with mortality in at least one model.

Our study acknowledges some few limitations. First, it was a single-center study, and there may be selection bias. Secondly, we included only patients with troponin measurements and some laboratory studies, were not conducted on all patients in this study because due its retrospective type. Thus, their implication in incidence and predicting in-hospital mortality may have been underestimated. Furthermore, echocardiography test, which may have added etiologic and prognostic information was not performed in all hospitalized patients. Therefore, more prospective multi-centric clinical trials are needed to further validate these findings.

To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this is the first study in Morocco to assess the impact of cardiac injury and its associated biomarkers on mortality and other prognosis in COVID-19-patients.

Conclusion

Although the exact prevalence of acute cardiac injury in hospitalized patients infected by the SARS-CoV-2 is still not clearly defined, our retrospective cohort found that cardiac injury defined by elevation of hs cTnI at the time of the hospital admission, is an independent risk factor for in-hospital mortality. Old age, comorbidities, a previous history of CAD, elevated creatinine level and elevated CRP at admission were significantly associated with acute cardiac injury. COVID-19 patients with acute cardiac injury are at a higher risk of ICU admission, and death. Therefore, early prevention is needed to reduce adverse outcomes in these patients.

Acknowledgements

non applicable

Footnotes

Ethics Approval and Informed Consent: Approval from the local ethics committee was obtained.

Written informed consent was obtained from a legally authorized representative(s) for anonymized patient information to be published in this article.

Data Availability: Data are available from the corresponding author by request.

Author's Contribution: F. Laouan Brem: conception, literature review, analysis, data collection, writing- review & editing

C. Miri: conception, software, writing- review & editing.

H. Rasras: conception, software, writing- review & editing.

M. Merbouh: conception, software, writing- review & editing.

M.a. Bouazzaoui: conception, software, analysis.

H. Bkiyar: conception, methodology, supervision

N. Abda: conception, methodology, analysis, supervision

Z. Bazid: conception, methodology, supervision

N. Ismaili: conception, methodology, supervision

B. Housni: conception, methodology, supervision

N. El Ouafi : conception, methodology, supervision

Source of Financial Support: there's no financial support

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate: Acceptable

Consent for Publication: Acceptable

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs: Falmata Laouan Brem https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5742-0781

Manal Merbouh https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4117-9222

Miri Chaymae https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3752-0953

References

- 1.Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323(11):1061-1069. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. Erratum in: JAMA. 2021 Mar 16;325(11):1113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, et al. Fourth universal definition of myocardial infarction (2018). Circulation. 2018;138(20):e618 − ee651. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000617. Erratum in: Circulation. 2018 Nov 13;138(20):e652. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Latif F, Farr MA, Clerkin KJ, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of recipients of heart transplant with coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5(10):1165-1169. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.2159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arentz M, Yim E, Klaff L, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of 21 critically ill patients with COVID-19 in Washington state. JAMA. 2020;323(16):1612-1614. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aggarwal S, Garcia-Telles N, Aggarwal G, Lavie C, Lippi G, Henry BM. Clinical features, laboratory characteristics, and outcomes of patients hospitalized with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): early report from the United States. Diagnosis (Berl ). 2020;7(2):91-96. doi: 10.1515/dx-2020-0046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lala A, Johnson KW, Januzzi JL, et al. Prevalence and impact of myocardial injury in patients hospitalized with COVID-19 infection. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76(5):533-546. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.06.007. Epub 2020 Jun 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Han H, Xie L, Liu R, et al. Analysis of heart injury laboratory parameters in 273 COVID-19 patients in one hospital in wuhan, China. J Med Virol. 2020;92(7):819-823. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25809. Epub 2020 Apr 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gheblawi M, Wang K, Viveiros Aet al. Angiotensin-Converting enzyme 2: SARS-CoV-2 receptor and regulator of the renin-angiotensin system: celebrating the 20th anniversary of the discovery of ACE2. Circ Res. 2020;126(10):1456-1474. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.120.317015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Babapoor-Farrokhran S, Gill D, Walker J, Rasekhi RT, Bozorgnia B, Amanullah A. Myocardial injury and COVID-19: possible mechanisms. Life Sci. 2020;253:117723. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2020.117723. Epub 2020 Apr 28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1054-1062. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. Epub 2020 Mar 11. Erratum in: Lancet. 2020 Mar 28;395(10229):1038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.He X, Wang L, Wang H, et al. Factors associated with acute cardiac injury and their effects on mortality in patients with COVID-19. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):20452. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-77172-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fan Q, Zhu H, Zhao Jet al. Risk factors for myocardial injury in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in China. ESC Heart Fail. 2020;7(6):4108-4117. doi: 10.1002/ehf2.13022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020 Feb 15;395(10223):497-506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. Epub 2020 Jan 24. Erratum in: Lancet. 2020 Jan 30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shi S, Qin M, Shen B, et al. Association of cardiac injury with mortality in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in wuhan, China. JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5(7):802-810. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.0950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vakhshoori M, Heidarpour M, Shafie D, Taheri M, Rezaei N, Sarrafzadegan N. Acute cardiac injury in COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Iran Med. 2020;23(11):801-812. doi: 10.34172/aim.2020.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zou F, Qian Z, Wang Y, Zhao Y, Bai J. Cardiac injury and COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. CJC Open. 2020;2(5):386-394. doi: 10.1016/j.cjco.2020.06.010. Epub 2020 Jun 23. PMID: 32838255; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wei JF, Huang FY, Xiong TY, et al. Acute myocardial injury is common in patients with COVID-19 and impairs their prognosis. Heart. 2020;106(15):1154-1159. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2020-317007. Epub 2020 Apr 30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen L, Hu W, Guo X, et al. Association of coagulation dysfunction with cardiac injury among hospitalized patients with COVID-19. Sci Rep 2021;11(1): 4432. 10.1038/s41598-021-83822-9 doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-83822-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li J, Zhang Y, Wang F, et al. Cardiac damage in patients with the severe type of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). BMC Cardiovasc Disord 2020;20(1):479. 10.1186/s12872-020-01758-w doi: 10.1186/s12872-020-01758-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jin JM, Bai P, He W, et al. Gender differences in patients with COVID-19: focus on severity and mortality. Front Public Health. 2020;8:152. Published 2020 Apr 29. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2020.00152 doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eirin A, Lerman A, Lerman LO. Mitochondrial injury and dysfunction in hypertension-induced cardiac damage. Eur Heart J. 2014;35(46):3258-3266. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu436. Epub 2014 Nov 10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saleh J, Peyssonnaux C, Singh KK, Edeas M. Mitochondria and microbiota dysfunction in COVID-19 pathogenesis. Mitochondrion. 2020;54:1-7. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2020.06.008. Epub 2020 Jun 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xu H, Hou K, Xu Ret al. et al. Clinical characteristics and risk factors of cardiac involvement in COVID-19. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9(18):e016807. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.120.016807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]