Abstract

For centuries, the study of traumatic brain injury (TBI) has been centred on historical observation and analyses of personal, social, and environmental processes, which have been examined separately. Today, computation implementation and vast patient data repositories can enable a concurrent analysis of personal, social, and environmental processes, providing insight into changes in health status transitions over time. We applied computational and data visualization techniques to categorize decade-long health records of 235,003 patients with TBI in Canada, from preceding injury to the injury event itself. Our results highlighted that health status transition patterns in TBI emerged along with the projection of comorbidity where many disorders, social and environmental adversities preceding injury are reflected in external causes of injury and injury severity. The strongest associations between health status preceding TBI and health status at the injury event were between multiple body system pathology and advanced age-related brain pathology networks. The interwoven aspects of health status on a time continuum can influence post-injury trajectories and should be considered in TBI risk analysis to improve prevention, diagnosis, and care.

Subject terms: Risk factors, Brain injuries, Epidemiology

Introduction

Health status has been traditionally considered to encompass different dimensions and has been defined by the World Health Organization as "a state of complete physical, mental, and social wellbeing, and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity"1. A recent discussion has highlighted the limitations of this definition and suggested that health status is rather a dynamic process that reflects a person's change, which is consistent with the life course perspective within an environment, and that the past influences the present2,3.

Research on the dynamic component of health status in traumatic brain injury (TBI), which refers to structural and/or physiological disruption of brain function due to an external force4, is rapidly developing in various contexts4–6. Recently, the view of TBI has shifted from that of an injury event, to a condition with lifelong consequences for both morbidity and mortality5,6. Furthermore, it has been proposed that TBI may not be a cause but rather an effect of multiple disorders associated with risk of falls and challenging behaviours, including epilepsy and substance-related disorders, among others5–8. With this in mind, recent advances have focused on the preventability of TBI following a head injury event and adverse TBI consequences6,9, which may be related to a wide range of risks within health status preceding the injury event, as well as the risk of an injury event itself 10,11.

The depiction of TBI as a disease process rather than an event has enhanced the understanding of health transition following the TBI event; however, the health status transition from the time preceding injury to an injury itself remains unclear, and the challenge of considering how health statuses of individual patients unfold differently over time remains. Some health-related conditions are chronic in nature and require continuous management13–15 at the time a person sustains an injury; in these situations, the disorder (e.g., cardiovascular, metabolic, and neurologic disorders) is more likely to be captured in the injury surveillance data, as these are considered in TBI management and care16. Other health-related conditions are temporal in nature (e.g., sprains and strains, acute intoxication, abuse) and may not be noted in the injury event but may increase the probability of an injury as a result of falls, such as among those with poor balance or confusion, thus reflecting changes at both the physiological and psychosomatic levels17,18. To complicate matters, most patients discharged directly from the emergency department (ED) receive a concussion diagnosis with non-specific complaints of headaches, dizziness, balance issues, and sensitivity to noise and light18–21. While the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score allows for a well-defined designation of TBI severity in more severe injury events that include a loss of consciousness and post-traumatic amnesia, this scale lacks sensitivity for milder injuries, such as concussion22. The GCS score is also inadequate to explain progressive symptom evolution from a relatively minor external physical force in patients who present with multiple disorders that require concurrent treatment at the time of the injury event23,24. Furthermore, disorders often coalesce with each other and with age-related factors and social adversities, which creates a vastly complex web of possible correlations to account for in the study of health status transition in TBI.

One method to increase confidence in the characterisation of health status transitions is to apply computational approaches to longitudinal health status data of patients with TBI both preceding and at the time of TBI diagnoses, and to compare these data with those of patients without TBI who are individually matched to TBI patients by sex, age, place of residence, and income level. This would allow health status to be studied in relation to the difference between the cohorts, and at two time points. In our recently published study6, we developed an algorithm to sequence thousands of diagnosis codes within the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) in 235,003 unique patients with TBI and the same number of patients without TBI, who visited ED or acute care hospitals over a decade. A total of 43 factors of health status from the five-years period preceding the TBI event that differentiated patients without a TBI were extracted and internally validated. Taking advantage of these 43 factors that describe the health status preceding TBI, here we first present a new analysis of data from the injury event, characterising health status of the same unique patients at the injury event. We then report associations between the factors of health status preceding TBI and that of an injury event, followed by portrayal of hierarchical clusters in data matrix of health status transitions, from time preceding injury to the injury event itself. We utilised the following steps in the analysis and validation process of the injury event phase and health status transition from the time of preceding injury to the TBI event phase: (1) determining the phase preceding TBI and the TBI event phase; (2) multiple testing to detect a set of definable health status patterns in TBI vs. non-TBI diagnoses; (3) factor analysis of health status patterns that are significantly related to TBI vs. non-TBI events; (4) a conditional logistic regression model and correlation matrix and hierarchical clustering using correlation-based distance to group health statuses at the TBI event; (5) health status transitions from the time preceding TBI6 to the TBI event, grouping all factors from each period into a single heatmap using agglomerative hierarchical clustering with interpretation of factors preceding and at the TBI event that are clustered together, to examine how many meaningful dimensions can be distinguished; and (6) internal validation of the results at each level analysis. Using this process, we confirmed that health status preceding injury is reflected in the injury event health status, and we provide evidence that health status preceding injury can explain the external cause of TBI and contribute to injury severity designation. These results provide a means to connect information on health status transitions in TBI and associated factors, from the time preceding injury to the injury event itself.

Methods

Population and health status data

We accessed the data from ICES25, which collects and stores health administrative data on publicly funded services provided to residents of Ontario, Canada, including information on acute care hospitalisations and ED visits. With nearly 14 million residents, Ontario is Canada's most populous province, comprising 43% of Canada's population26. Universal health care covers all medically necessary healthcare services at the point of care. The standardised discharge summary includes patient demographics and main and secondary diagnoses according to ICD-10 codes27. The ICD-10 codes consist of a combination of alphanumeric characters that characterise broad diagnosis categories. Each code is designed as an alphanumeric code and arranged hierarchically, with the code length ranging from 3 to 6 characters. The first three characters designate the category of the diagnosis, which is the same as the World Health Organisation's ICD-10 international standard for reporting diseases and health conditions28. The health service records data are linked deterministically at the individual level through a unique, encoded identifier based on name, sex, date of birth, and postal code. By applying unique de-identified health records, the health status trajectory of each patient can be tracked over time.

We used a previously established cohort of patients discharged between the fiscal years (defined as from April 1 to March 31) 2007/2008 and 2015/2016 from the ED (identified in the National Ambulatory Care Reporting System) and acute care (identified in the Discharge Abstract Database) with a diagnostic code for TBI (ICD-10 codes S02.0, S02.1, S02.3, S02.7, S02.8, S02.9, S04.0, S07.1, and S06)6; these patients comprised the TBI cohort in the present study. Patient demographics, main and secondary diagnoses, conditions, problems, or circumstances data27 were extracted for each individual patient. We selected a 10% random sample of patients discharged from the ED or acute care hospitals during the same study period for a reason other than TBI, and individually matched these to patients with TBI by sex, age, place of residence (urban vs. rural), and income quintile; these patients comprised the reference population6.

We followed previously published severity classifications29,30 to assign TBI injury severity. External causes of injury were determined using Centers for Disease Control (CDC) and Prevention major external cause of injury group codes, which were divided into falls, struck by/against an object, motor vehicle collision (MVC) and other causes31. We further identified assault-related TBI using ICD-10 codes specified by the CDC31. Sports-related injuries were identified based on the Association of Public Health Epidemiologists in Ontario (APHEO)32.

-

Step 1.

Determining the phase preceding TBI and the TBI event phase

The index date for patients with TBI was defined as their first occurrence of TBI over the study period, whereas, for the reference population, the index date was the midpoint of the ED or acute care visits. Data from 235,003 unique patients with TBI (and a same number of reference patients) were randomly split into training (50%; n = 117,689), validation (25%; n = 58,798), and testing (25%; n = 58,516) datasets. All analyses were completed and reported using the testing dataset, and the training and validation datasets were used for internal validation.

-

Step 2.Multiple testing to detect a set of definable health status patterns in TBI vs. non-TBI diagnoses

-

Health status preceding the injury eventWe evaluated the health status preceding a TBI event reported by previous studies6,33. From all the possible ICD-10 codes classifying patients' main and secondary diagnoses, a previous data mining and validation study identified 43 factors that were significantly overrepresented in patients with TBI compared to reference patients (individually matched based on sex, age, place of residence, and income quintile) within the 5 years preceding their TBI event. For details, please see the study6.

-

Health status at the injury eventTo identify health status at the TBI event and to gain insight into its observed correlations, we analyzed all ICD-10 codes depicted across the 10 and 25 diagnoses fields of the National Ambulatory Care Reporting System and the Discharge Abstract Database, respectively, for patients with TBI and reference patients at the index date. We converted all 2,600 codes into binary variables, except for provisional codes for research and temporary assignments, U98 and U99. The first three characters (one alphabetic and two numeric) of the ICD-10 comprised 2,600 distinct codes that defined specific diagnoses. These 2,600 binary ICD-10 code variables were tested for significant correlations with TBI diagnosis codes using a matched McNemar test with correction for multiple testing34. The Benjamini-Yekutieli method was applied to acquire a set of codes controlled at a False Discovery Rate (FDR) of 5%35,36. We identified ICD-10 codes that were associated with a TBI event, for which we then calculated odds ratios (ORs) to compare with the reference population (Supplementary File). To eliminate measurement artifacts, the procedure was first performed using the training dataset and then repeated using the validation dataset37. Only codes that were significant in both the training and validation sets were retained for further analysis.

-

-

Step 3.

Factor analysis of health status patterns that are significantly related to TBI vs. non-TBI events

To gain insight into the dimensionality structure of individual diagnosis codes, we performed factor analysis using principal components methods38. The optimal number of factors was determined by the breakpoint on the scree plot, eigenvalue, the greatest cumulative proportion of variance accounted for, and via a conditional logistic regression looped through all possible factors covering the largest area under the receiver operating characteristic curves39 (Supplementary Fig. 1, Supplementary Table 2).

-

Step 4.

Conditional logistic regression model and correlation matrix and hierarchical clustering

The conditional logistic regression model was built using binary factor-based scores40. Patients were assigned a score of one if they possessed any of the ICD-10 codes in the factor definition; otherwise, they were assigned a zero. These factor-based scores were used to calculate ORs and 95% confidence intervals from a conditional logistic regression model40 on the association between each factor and TBI, controlling for sex, age, rurality, and income in the testing dataset and then repeated in the training and validating datasets. To visualise the results of the factor analysis and conditional logistic regression model, a Pearson's correlation matrix was generated for all significant factors41, and hierarchical clustering was performed on similar group factors using correlation-based distance42 to identify groups of people with similar associative factors for TBI. To aid in the visualisation of clusters in the heatmap, clustering was performed using Ward (minimum variance) linkages43. The algorithms for these agglomerative clustering methods have been described elsewhere43.

-

Step 5.

Health status transitions from the time preceding TBI to the TBI event

To further expand our understanding of health status transitions from the time preceding TBI to the TBI event, we clustered all factors from each period into a single heatmap, where values of factors representing each time period were correlated. This was done using a Fisher transformation, which converted the correlations into "z-like statistics" 44. Next, factors preceding TBI were pooled into separate "injury severity" and "mechanisms of injury" event groupings.

-

Step 6.

Internal validation of the results

To determine the consistency of observed patterns, heatmaps were generated and compared between the training, validation, and testing dataset, with an FDR-corrected alpha set at 0.05. All correlations with adjusted p-values greater than 0.05 were set to 0 on the heatmaps, leaving only significant correlations with an FDR < 0.05.

All analyses were conducted using SAS software (version 9.410, SAS Inc., Cary, NC) and R (version 3.4.1.11, R Foundation for Statistical Computing; www.r-project.org). Figures were created using R (ComplexHeatmap and Wordcloud, R Foundation for Statistical Computing; www.r-project.org).

Ethical approval and informed consent

Approval: The study protocol was approved by the ethics committees at the clinical (University Health Network) and academic (University of Toronto) institutions. Accordance: All methods were carried out in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. Informed consent: This research utilised de-identified health administrative data with no access to personal information. No humans were directly involved in this study.

Results

Of the 58,516 patients in the testing dataset, 57% were male, and 43% were female. The most common TBI mechanisms were falls (n = 26,480 [45%]) and being struck by/against an object (n = 20,845 [36%]). Of all injuries, 25% were sports-related, and 10% were sustained in a MVC. Assaults accounted for 7% of TBIs. Injury severity was not established in 25,036 [43%] patients; most of these cases were recorded as concussion without a specified length of unconsciousness (ICD-10 code S06.0; Table 1 and Supplementary Table 3).

-

Step 1.

Determining the phase preceding TBI and the TBI event phase

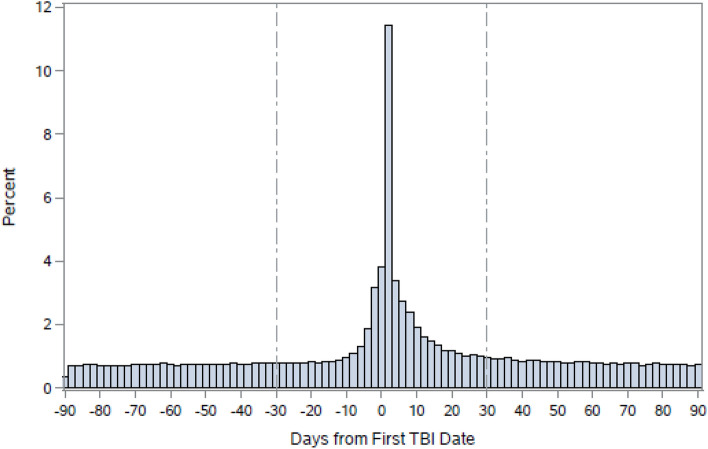

We found that ED and acute care visits prior to and following the TBI event (i.e., index date for TBI) followed a certain trend, whereby they appeared to plateau 30 days before and after the index date and remained largely unchanged after that (Fig. 1). Therefore, this 61-day period was defined as the TBI event window, whereas all ED and acute care visits within five years up to 30 days prior to a TBI event were considered to be the pre-injury phase. A similar procedure was performed for each patient in the reference population sample, with the exception that the midpoint of each patient's ED and acute care visits was selected as an index date.

-

Step 2.

Multiple testing to detect a set of definable health status patterns in TBI vs. non-TBI diagnoses

The matched McNemar tests were performed on the training dataset for 2,600 ICD-10 codes at the first three-character level, for patients with TBI and their matched reference patients, for significant associations with TBI diagnosis. The Benjamini-Yekutieli multiple testing, applied to acquire a set of codes controlled at a FDR of 5%, recognised 273 diagnoses codes that were significantly associated with TBI diagnosis (i.e., had an OR > 1). These codes were re-tested on the validation dataset, and 226 (83%) of them were internally validated (Supplementary Tables 3 and 4). Only codes that were significant in both the training and validation sets were retained for further factor analysis using the principal components method.

-

Step 3.

Factor analysis of health status patterns that are significantly related to TBI vs. non-TBI events

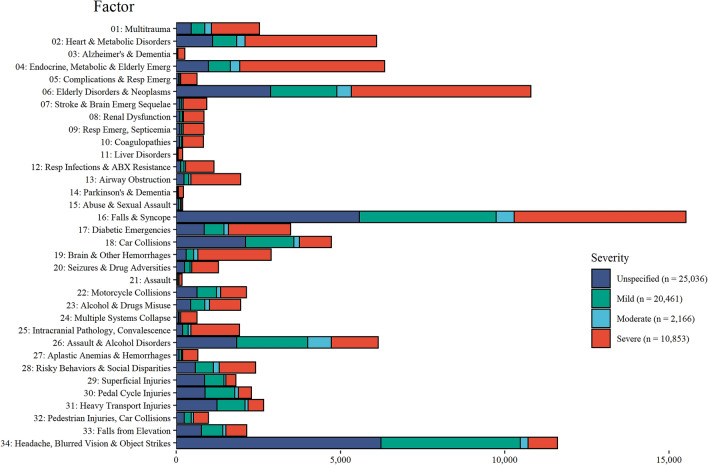

Factor analysis was applied to the training dataset. Of the 226 codes included in the analysis, 164 (73%) unique codes met the factor loading cut-off of 0.2 (Supplementary Fig. 2). For details on frequencies, ORs, and factor loadings of codes that met the factor analysis cut-off and codes that did not meet the cut-off, see Supplementary Tables 4 and 5, respectively. Using the breakpoints on the scree plots and the interpretability, 35 factors were selected. One factor (asphyxiation, suicide) had low frequencies in the reference population (< 6) and was excluded from further analyses. The remaining 34 factors were studied further. Figure 2 presents each factor by injury severity share.

Table 2 presents the descriptions, frequencies, ORs, and ICD-10 codes included for each of the 34 factors. Supplementary Table 4 presents factor loadings and detailed descriptions of each factor.

-

Step 4.

Conditional logistic regression model, correlation matrix, and hierarchical clustering

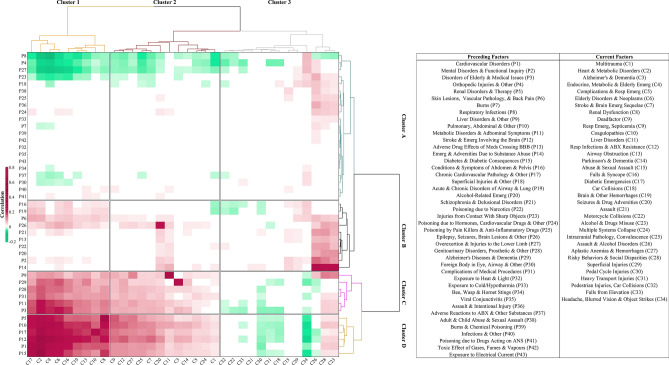

Heatmaps of factors preceding TBI and factors of the TBI event are presented in Fig. 3.

-

Step 5.

Health status transitions from the time preceding TBI to the TBI event

The strongest positive correlations between health status preceding TBI and health status at the injury event were between Cluster D and Cluster 1 (i.e., multiple body system pathology) and Cluster C and Cluster 2 (i.e., advanced age-related brain pathology). The multiple body system pathology was composed of endocrine system pathology, i.e., diabetes and diabetic emergencies (Factors P15 and Factor C17), cardiovascular system pathology (Factor P1 and Factor C2), alterations in renal and urinary tract function (Factor P5 and Factor C8 ), and brain haemorrhages and stroke (Factor P12 and Factor C19). The advanced age-related brain pathology consisted of liver disorders (Factor C11 and Factor P9), Alzheimer's disease and dementia (Factor P29 and Factor C3), and aplastic anaemias and haemorrhages and liver disorders (Factor P9 and Factor C27), among other advanced neurological sequelae.

Cluster B preceding TBI (i.e., poisons, drug overdose, social adversity) was strongly associated with multiple pathologies at the injury event (Clusters 1–3), including seizures and drug adversities (Factor P26 and Factor C20) and illnesses due to poisons and drug overdose (Factor P9 and Factor C23; Factor P13 and Factor C26). Weaker correlations were observed between multiple body system pathology (Cluster 1) and advanced age-related brain pathology at the injury event and Cluster A preceding injury (i.e., young age-related concerns), assault and intentional injury (Factors P28 and P36 and Factor C26), overexertion and superficial injuries, exposure to environmental adversities (i.e., burns, cold/hypothermia, exposure to heat/light), and lifestyle and adverse drug effect preceding injury (Factors P18, P7, P33, and Factors C23 and C28).-

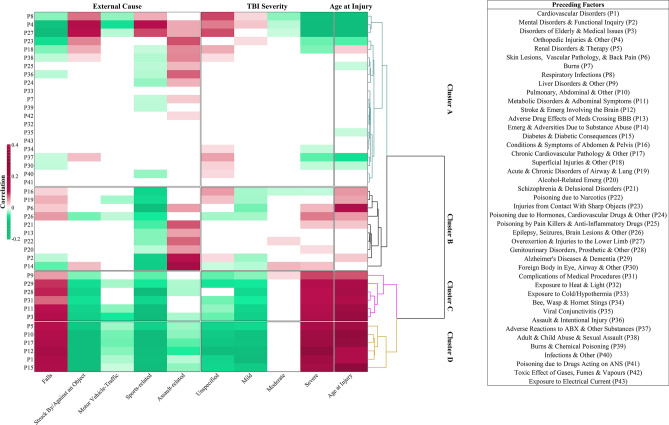

Health status preceding injury associates with injury severity and external causes of injuryMany of the health status factors preceding TBI showed a significant association with TBI severity, thereby likely contributing to the GCS score at the time of injury. For example, severe TBI and age at injury were characterized by a link to Clusters C and D preceding injury (i.e., multiple body system pathology and advanced age-related brain pathology, Fig. 4), which comprised metabolic disorders (Factors P9, P11, P15), neurological disorders (Factor P12), cardiovascular pathology (Factors P1 and P17), Alzheimer's disease and dementia (Factor P29), and disorders of older people (Factor P3). In contrast, respiratory infections, musculoskeletal (MSK) injuries, and overexertion in Cluster A (i.e., young age-related concerns, Factors P8, P4, and P27) preceding TBI were negatively correlated with severe TBI. A reverse health status association was observed for the mild and unspecified TBI severity, whereas moderate TBI severity showed positive correlations with the cluster of disorders associated with poisoning due to narcotics, substance abuse, and liver pathology preceding injury (Factors P22, P14, and P9). This clustering analysis was performed separately for the training, validation, and testing datasets, and consistent patterns in the clustering of health status factors with injury severity were observed across each dataset.External causes of injury were also distinguished by combined clusters of health status factors preceding TBI. Falls were characterised by a strong positive correlation with Clusters C and D (i.e., multiple body system pathology and advanced age-related brain pathology), mimicking the clusters associated with severe TBI, and a strong negative correlation with Cluster A (i.e., young age-related concerns), mimicking the clusters associated with mild and unspecified TBI severity. In contrast, struck by/against an object showed a strong positive correlation with Cluster A and negative correlations with Clusters C and D.A few patterns of weak negative correlations were observed between health status preceding TBI and MVC as an external cause of injury, whereas sport-related and assault-related causes of injury showed distinct positive correlations with health status preceding TBI. Meaningful observations included clustering of respiratory infections preceding injury with orthopaedic injuries and overexertion (Cluster A, Factors P8 with P4 and P27) in sport-related injury, and preceding injury poisoning by drugs and other substances, assault and abuse, and injuries from contact with sharp objects (Cluster B, Factors P23, P24, P36, and P38) with assault-related TBI.

-

-

Step 6.

Internal validation

To determine the consistency of the observed patterns, clustering analysis and heatmaps were generated and compared between the training, validation, and testing datasets. All reported results were confirmed in the training and validation datasets, and clusters and heatmaps were shown to be robust (Supplementary Figs. 2 and 3).

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients with a first traumatic brain injury-related visit in the ED or acute care and matched reference patients.

| Variables | Patients with TBI (N = 58,516) | Reference patients (N = 58,516) |

|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic characteristics | ||

| Sex, n (%) | ||

| Male | 33,379 (57) | 33,379 (57) |

| Female | 25,137 (43) | 25,137 (43) |

| Age at injury (years), mean (SD) | 36.23 (25.33) | 36.24 (25.32) |

| Income quintile, n (%) | ||

| Q1 (lowest) | 11,465 (20) | 11,465 (20) |

| Q2 | 11,540 (20) | 11,540 (20) |

| Q3 | 11,494 (20) | 11,494 (20) |

| Q4 | 12,182 (20) | 12,182 (20) |

| Q5 (highest) | 11,835 (20) | 11,835(20) |

| Rural residence | 9,084 (16) | 9,084 (16) |

| TBI-related characteristics | ||

| TBI main diagnosis, n (%) | 51,705 (88) | NA |

| Injury severity, n (%) | ||

| Unspecified | 25,036 (43) | NA |

| Mild | 20,461 (35) | NA |

| Moderate | 2,166 (4) | NA |

| Severe | 10,853 (19) | NA |

| Type of first healthcare entry, n (%) | ||

| Emergency Department | 48,142 (82) | NA |

| Acute Care | 4,147 (7) | NA |

| Emergency & Acute* | 6,227 (11) | NA |

| External Cause and Context of Injury, n (%)** | ||

| Sports injury | 14,472 (25) | NA |

| Assault | 4,359 (7) | NA |

| Falls | 26,480 (45) | NA |

| Motor vehicle collisions | 5,808 (10) | NA |

| Struck by/against | 20,845 (36) | NA |

| Other | 6,791 (12) | NA |

| Missing | 166 (0) | NA |

n/a = not applicable; TBI = traumatic brain injury; SD = standard deviation. Data given as mean (standard deviation) or n (%). *A patient had a transfer to either location on the same day. **A patient may have several designations (i.e., sports injury and struct by/against an object).

Figure 1.

A number of hospital visits surrounding the TBI index date. Reprinted from Mollayeva, T. et al.6. The figure was originally published under a CC BY license (Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License).

Figure 2.

Health status factors at the TBI event phase by injury severity in patients with TBI in Ontario, Canada 2002–2016. The total number of each health status factor in TBI event across the sample set (n = 58,516). Data are shown for each injury severity, coloured by mild, moderate, severe, and unspecified. Abbreviations: ABX = antibiotics; Emerg= emergency; Resp= respiratory

Table 2.

Factor analyses with ICD-10-CA codes, disease category and effect size (OR and 95% CI).

| Factor number | Short description | Category | ICD-10 codes | Frequency in cohorts | OR [95% CI] |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TBI | Ref | |||||

| Factor 1 | Multitrauma | Emergency Medicine | S36, S27, S37, T06, T79, S42, S26, S72 | 2535 | 749 | 3.49 [3.21–3.79] |

| Factor 2 | Heart & Metabolic Disorders | Cardiology | E78, I10, I48, Z95, I50, Z92, E03, E11 | 6095 | 3,787 | 1.97 [1.88–2.07] |

| Factor 3 | Alzheimer’s & Dementia | Neurology | F00, G30 | 267 | 79 | 3.41 [2.65–4.39] |

| Factor 4 | Endocrine, Metabolic & Elderly Disorder | Emergency Medicine/Geriatrics | I10, E87, E83, E22, F05, Z75, N17, F06, B96, I95, R41 | 6338 | 2,873 | 2.85 [2.70–3.00] |

| Factor 5 | Complications & Respiratory Disorders | Emergency Medicine | J95, Y84, J15 | 638 | 204 | 3.14 [2.68–3.68] |

| Factor 6 | Elderly Disorders & Neoplasms | Geriatrics | S72, F05, Z75, R41, F03, Z51, R29, W05, R26, W19, C79, Z74, W06 | 10,793 | 2,275 | 6.92 [6.54–7.31] |

| Factor 7 | Stroke & Brain Emerg Sequelae | Neurology/Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation | G81, R47, I63, I69, R13 | 929 | 322 | 2.96 [2.61–3.37] |

| Factor 8 | Renal Dysfunction | Nephrology | N17, Z99, N18, N08 | 845 | 439 | 2.00 [1.77–2.25] |

| Factor 9 | Respiratory Emergencies, Septicaemia | Emergency Medicine | N17, J17, A41, J96 | 844 | 378 | 2.32 [2.05–2.63] |

| Factor 10 | Coagulopathies | Haematology | Z92, Y44, D68 | 826 | 183 | 4.65 [3.95–5.48] |

| Factor 11 | Liver Disorders | Gastroenterology | K70, R18, K72, B18 | 198 | 71 | 2.79 [2.13–3.66] |

| Factor 12 | Respiratory Infections & ABX Resistance | Infectious Diseases | B96, B95, U82, A49, L89 | 1147 | 570 | 2.09 [1.88–2.31] |

| Factor 13 | Airway Obstruction | Emergency Medicine | Z51, R13, J96, L89, J69, W80 | 1956 | 771 | 2.70 [2.48–2.95] |

| Factor 14 | Parkinson’s & Dementia | Neurology | F02, G20, G31 | 221 | 50 | 4.42 [3.25–6.01] |

| Factor 15 | Abuse & Sexual Assault | Family medicine/ Psychiatry/Trauma | T74, Y07, Y05, Y06 | 196 | 15 | 13.07 [7.73–22.09] |

| Factor 16 | Syncope & Falls | Emergency Medicine/Mechanism | I95, W19, R55, W18, W01 | 15,516 | 3,106 | 6.79 [6.49–7.11] |

| Factor 17 | Diabetic Emergencies | Emergency Medicine | E11, N08, E14, R73, G63 | 3479 | 2,426 | 1.54 [1.45–1.63] |

| Factor 18 | Car Collision | External cause of injury | V43, V49, V48, V89, V47, T14, Z04, V58 | 4723 | 711 | 7.14 [6.58–7.75] |

| Factor 19 | Brain & Other Haemorrhages | Neurology | Z51, C79, I61, I60, G91, I62, G06, I67, Z54 | 2,887 | 744 | 4.24 [3.90–4.62] |

| Factor 20 | Seizures & Drug Adversities | Neurology/Pharmacology Emergencies | Y46, G40, T42, R56, G41, R27 | 184 | 288 | 4.56 [4.00–5.19] |

| Factor 21 | Assault | External cause of injury | X99, S21, S11, S15 | 178 | 33 | 5.39 [3.72–7.82] |

| Factor 22 | Motorcycle Accidents | External cause of injury | S42, V28, V29, V27, V23, V86, V22 | 2133 | 674 | 3.27 [3.00–3.58] |

| Factor 23 | Alcohol & Drugs Misuse | Psychiatry | Y90, R78, F10 | 1,960 | 435 | 4.66 [4.19–5.18] |

| Factor 24 | Multiple Systems Collapse | Emergency Medicine /Neurosurgery | G93, Z52, D65, E23, I46 | 629 | 76 | 8.28 [6.53–10.51] |

| Factor 25 | Intracranial Pathology, Convalescence | Emergency Medicine/Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation | S72, Z51, C79, I62, Z54, Z50 | 1925 | 363 | 5.75 [5.11–6.46] |

| Factor 26 | Assault & Alcohol Disorders | Psychiatry/ Population and Community Health/ Mechanism | F10, Y04, Y09, Y00, H05, H11, H53, Y08 | 6151 | 762 | 9.30 [8.58–10.09] |

| Factor 27 | Aplastic Anaemias & Haemorrhages | Haematology/Neurology | D46, D61, D69, D64 | 659 | 455 | 1.46 [1.29–1.65] |

| Factor 28 | Risky Behaviours & Social Disparities | Family Medicine/ Psychiatry/Population and Community Health | B18, F10, F14, F11, Z59, Z91, Z72, Z21 | 2417 | 694 | 3.64 [3.34–3.97] |

| Factor 29 | Superficial Injuries | Emergency Medicine | S30, S40, S70, S20, S10, S39 | 1,813 | 894 | 2.06 [1.90–2.23] |

| Factor 30 | Pedal Cycle Injuries | External cause of injury | V18, V19, T00, V13, V17 | 2292 | 514 | 4.64 [4.21–5.13] |

| Factor 31 | Heavy Transport Injuries | External cause of injury | V43, V44, V54, S19 | 2661 | 298 | 9.53 [8.42–10.79] |

| Factor 32 | Pedestrian Injuries, Car Crashes | External cause of injury | S15, V03, V09, T08, T02, I72 | 982 | 92 | 10.89 [8.78–13.52] |

| Factor 33 | Falls from Elevation | External cause of injury | W17, W13, W11, W12 | 2147 | 296 | 7.59 [6.70–8.59] |

| Factor 34 | Headache, Blurred Vision & Object Strikes | Neurology/Mechanism | R51, F07, G44, W22, Z02, W20 | 11,604 | 2,079 | 6.80 [6.45–7.16] |

ABX = antibiotics; CI = confidence interval; OR = odds ratio; TBI = traumatic brain injury; SD = standard deviation. Frequencies given as numbers.

Figure 3.

Cluster analysis and heatmap across 43 factors preceding TBI (y-axis) and 34 factors at the TBI event (x-axis). On the left y-axis, preceding injury clusters (Clusters A-D) are annotated for reference with the text. On the upper x-axis, TBI event clusters (Clusters 1–3) are likewise annotated. Annotations are presented as guidelines and are not definitive. Only internally validated factors in the testing and validation datasets are presented. In the heatmap, each colour represents a set of binned ranks in the heatmap, with green colours representing negative correlations and magenta colours representing positive correlations, adjusted for FDR. White fields represent non-significant correlations after adjustment for FDR.

Figure 4.

Cluster analysis and heatmap across 43 factors preceding TBI (y-axis) and mechanism, context of injury and TBI severity (x-axis). On the right y-axis, sample-based clusters are observed. Annotations are presented as guidelines and are not definitive. Only factors that were internally validated in the testing and validation datasets are represented. In the heatmap, each colour represents a set of binned ranks in the heatmap, with green colours representing negative correlations and magenta colours representing positive correlations, adjusted for FDR. White fields represent non-significant correlations after adjustment for FDR.

Discussion

In this paper, we described a method for aligning health status transition in TBI, a disorder of significant public health concern and a major cause of disability worldwide4,45. The methods presented here describe a non-hypothesis-driven approach for detecting health status at injury events and combining them with health status results preceding the injury. This approach offers an explanation for the challenges associated with injury diagnosis, classification, and surveillance, which can be confounded by population health heterogeneity and epigenetic ambiguity46. With these challenges in mind, we conducted an impartial and interpretable assessment of health status transitions in TBI accounting for 2,600 individual diagnoses encoded using the ICD-103 in a retrospective cohort of people of all ages, biological sex, socioeconomic standing, and place of living who had universally-funded access to healthcare. We internally validated our results and found them to be robust. We believe that the presented method to study health status transitions in TBI will spur the development of additional methods and prove useful for future analyses on health status transition after the injury event. Application of a health status transitions perspective to contextual injury event, and recognition that health status preceding injury makes a person more or less susceptible to TBI due to specific external cause of injury and developing a more or less severe TBI, entails new approaches to injury taxonomy, treatment and rehabilitation, and predictive classifications. This is important to avoid transition bias that can arise when people are prognostically different at the injury event phase because of their health status preceding injury. The results encourage dialogue among researchers, clinicians, and policymakers on health status transition perspective in TBI and other complex disorders and injuries.

Our results demonstrate that the transitions in health status from the time preceding injury and the injury event are depicted in the patterns of associations, external cause of injury and injury severity. We observed both hidden transitions, when the person's exposures preceding injury were not a constituent of the health status captured in the TBI event (i.e., exposures to gases and fumes, electrical currents, sharp objects, machinery, as shown by white fields in Figs. 3 and 4), as well as observed transitions, when the health status preceding injury was contained in the assessment of the injury event. Such transitions include cardiovascular, endocrine, metabolic, and neurological disorders, and disorders of the elderly, that were not resolute with time, and which were significantly reflected in the TBI event's external cause of injury and injury severity (magenta and green fields in Figs. 3 and 4). Together, these results suggest that patterns in the health status transition of patients with TBI emerge along the course of their comorbidity, which is consistent with previous reports45,47–51.

Our results suggest that many disorders preceding injury are reflected in external causes of injury and injury severity. Disorders clustering within the same external cause of injury and injury severity, as highlighted here, illuminate TBI as an event that is constructed within the context of health and social statuses, both formative and reflective6,52. For example, we observed that clusters composed of cardiovascular and metabolic disorders, stroke, dementia, and disorders of the elderly preceding TBI were strongly associated with falls and severe TBI. While the above disorders, individually, have long been known to be implicated in the risk of falls53–55, we demonstrated their formative links, both with other disorders and with TBI diagnosis. The association of Clusters C and D with TBI severity found here has significant diagnostic relevance. In this regard, both the depth and duration of coma following the injury event have been considered as an injury severity indicator using the GCS score56. While it has been previously suggested that GCS scores can be affected by intoxication, hypoxia, and hypotension, among other things57–59, the health status and age of patients presenting with these signs are not currently accounted for when determining injury severity. This has both clinical and policy implications, as there is a continuing debate over use of the GCS score in trauma patients of all ages, including preverbal children, to determine the time to extubation60, sedate60, and withdraw life support61, as well as intensive care stay duration62, rehabilitation63, discharge destination64, resource utilisation65, and litigation66.

A large number of patients with TBI in our sample (43%) did not have an established injury severity; most of these events were coded as concussions without a specified length of unconsciousness (S06.0 codes). The links between MSK illnesses preceding injury event and unspecified TBI severity sustained in a sports-related context have been described previously6; however their clustering on young age-related disorders (i.e., respiratory infections and adverse reaction to antibiotics (Factors P8 and P37), overexertion (Factor P27), adult and child abuse and assault (Factor P38), and foreign body in eye or airway (Factor P30) preceding injury) are novel findings. They may highlight the limitations of establishing level of responsiveness according to three aspects – eye-opening, motor, and verbal responses – in compromised person-environment and healthcare interactions, as well as a greater probability of an unwitnessed injury event in such interactions.

Finally, our results provide a basis for using pre-injury health status as an integral part of precision medicine and injury surveillance. We found clusters of factors associated with severe injury and those with mild injury severity and concussion. Factors clustering on moderate-to-severe TBI are composed of system-level disorders, poisons, and drug overdose, and those associated with mild TBI and unspecified injury severity (i.e., concussion codes) are composed of MSK-related injuries and respiratory illnesses. The external cause of injury, especially falls and struck by/against an object, nearly clustered in accordance to the severity, with falls linked to patients with system-level and neurological disorders and severe TBI, and being struck by/against an object linked to superficial injuries, overexertion, orthopaedic injuries, and mild TBI and concussions67,68. Notably, MVCs showed very few associations, all negative, the most significant of which, across clusters, were orthopaedic injuries, seizure disorders, and disorders of older people; these conditions linked to obstacles to, or lack of authorisation to operate a machinery69–71.

As presented in this research, we developed a feasible method to work with big data and complex clinical and public health topics in TBI simultaneously, which can be applied to other complex disorders and injuries. We have shown that it is possible to convert thousands of diagnoses encoded within the ICD-10 structure into hundreds of TBI-related diagnoses, and then further reduce these diagnoses into few dozens of factors that collectively explain the TBI event's significantly shared variance with factors preceding TBI. We created a procedure for visualised cluster analysis and heatmaps to accurately trace health status transitions and to detect and localise the clusters associated with the transitions. Encouraged by meaningful observations, we adapted and extended the analyses to external causes of injury and injury severity, and provided evidence that health status preceding an injury event is reflected in the injury event, as TBI-event health status and factors were implicated in the cause of injury and injury severity designation. Depending on the cluster and its formation, we anticipate that our analyses could offer new important information on injury severity in the case of falls and being struck by/against an object, and assault-related injury surveillance.

Despite the scientific and technological advances captured in this work, there are still questions to be addressed in future research. The data-driven approach we developed and the results are based on ED and acute care hospital records; there are still persons with TBI who may choose to be treated at a primary care facility within the healthcare system, which could be an additional source for coding injury and morbidity data. Primary care data should be explored in the future, given that hospital data tends to be efficient and does not always strive for completeness27,28. This is important for assault-related injury surveillance, as the ICD codes do not capture the victim/perpetrator relationship, e.g., TBIs due to intimate-partner violence. In Ontario, a code is mandatory only when the condition or circumstance exists at the patient's visit and is significant to the patient's treatment or care28. In the future, we plan further investigation and external validation of health status preceding injury, especially for circumstances not reflected in the TBI event window, but which were implicated in the external cause and severity of the injury, linking them to recovery and functional trajectory. In addition, we used the first three characters in the ICD-10, which designate the category of the diagnosis at the time preceding an injury event72. By using the whole sequence of codes instead of the first three characters, more data can be preserved for model testing, training, and validation; however, this necessitates a higher computing power to run the analyses72. Finally, despite the reliability/validity of ICES data on ED and acute care visits73,74, there may remain uncovered variation between Ontarians due to differences in access to care and help-seeking behaviours. This may be especially true for certain external causes of TBI, for example, assault related TBIs sustained in rural settings75. In an effort to mitigate this issue, we internally validated the results that emerged in the testing dataset using the training and validation datasets and detailed these results in the supplementary material of the manuscript. Nonetheless, future research would require ensuring generalizability by externally validating the described health status transitions using data from a patient population across Canada.

Implications for prevention

Primary prevention seeks to circumvent injury before it occurs by protecting persons and vulnerable groups among the population76. Secondary prevention involves early recognition and targeting conditions that have already produced pathological change77, to stop the adverse injury course. Tertiary and quaternary prevention involves treatment directed to prevent long-term complications and minimize disability78,79. This research focused on time preceding injury and injury event, shown diagrammatically in Fig. 4, and, therefore, allowing the discussion of primary and secondary prevention initiatives.

Advanced age-related brain pathology (Cluster D) and disorders associated with poisoning due to narcotics, substance abuse and liver pathology (Cluster B) preceding TBI could be targeted in primary prevention. These relevant clusters preceding injury were associated with severe TBI, multiple pathologies, and other neurological sequelae at the time of injury. Interventions focusing on balance, posture, and moving equipoise training in the elderly has shown to be accompanied by a decline in falls80–82. Aside from targeting postural instability due to age-related motor impairments, advanced age-related brain pathologies highlighted in this work have been reported to challenge the risk–benefit ratio balance of treatment options with links to falls83. There has been a recent call to utilise a minimally disruptive approach when deciding on pharmacological management of conditions of the elderly to reduce the likelihood of drug interactions and falls prevention84.

Raising awareness about the links between poisoning due to narcotics, substance abuse, and liver pathology (Cluster B) preceding injury and assault related TBI is important85. While the ability of healthcare providers to prevent or modify such behaviors has not been proven, it might be possible to direct medical effort to the prevention of alcohol and drug-associated problems and, by that, prevent injury, violence, and medical complications of drug abuse86. Early detection and interventions that have proven effective for addictions include brief counselling, referral to ambulatory and inpatient treatment programs, community organizations, and appropriate medication use for substance use withdrawal87–89. Likewise, screening for exposure to relationship violence (i.e., adult and child abuse and sexual assault) and developing long-term plans and referrals to appropriate community and governmental agencies may prevent assault related TBIs90.

Ideas for secondary prevention strategies emerged from the results of this research include attention to interventions directed on the risk associated with the loss of patient autonomy in severe TBI cases, strongly linked to multiple body system pathology both preceding and at the time of injury (Cluster C and Cluster 1). Experimental therapies that inhibit the release of excitotoxins that play an important role in secondary injury to attenuate cellular oxidative and metabolic stress might prove to be effective91. Likewise, because of the substantial risks of repeated TBIs and adverse TBI outcomes from unaddressed narcotics, substance abuse and liver pathology (Cluster B), healthcare adoption of a broad construction of health status transition, considering family and social environments of their patients, is key92. Routinely eliciting information about the home, work, and neighbourhood exposures, and documenting family and social circumstances93 can help direct secondary prevention interventions and recommendations, as individual patients' situations will dictate feasible targets to which primary care providers should be alerted, when intended to ameliorate the course of TBI.

In summary, advances in data-driven analysis reveal a remarkable extent of meaningful associations in health status in the time preceding and following a TBI event that direct ideas for primary and secondary prevention. Possible extensions to this line of research would involve detecting health status transitions from the event to post-injury phase that could support tertiary and quaternary prevention, with compelling injury surveillance and public health ramifications.

Clinical implications

The study results highlight clinical implications of health status transition in TBI, which necessitate integration of primary and secondary preventive practices into the care of individual patients. Despite challenges associated with limited reimbursement and time94, skepticism about patients' commitment to change95, and conflicting professional recommendations96,97, preventive practices fall under direct clinical provision of health promoting strategies and prophylactic treatment98.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The research reported in this presentation was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R21HD089106 and National Institute Of Neurological Disorders And Stroke of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01NS117921. The content is solely the authors' responsibility and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. This study contracted ICES Data & Analytic Services (DAS) and used de-identified data from the ICES Data Repository, which is managed by ICES with support from its funders and partners: Canada's Strategy for Patient-Oriented Research (SPOR), the Ontario SPOR Support Unit, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and the Government of Ontario. The opinions, results and conclusions reported are those of the authors. No endorsement by ICES or any of its funders or partners is intended or should be inferred. Parts of this material are based on data and information compiled and provided by CIHI. However, the analyses, conclusions, opinions and statements expressed herein are those of the author, and not necessarily those of CIHI. This work was funded in part by the Canada Research Chairs Program.

Glossary of terms

- Benjamini-Yekutieli procedure

A statistical procedure that controls the false discovery rate under arbitrary dependence assumptions.

- Cluster

A statistical classification technique in which a network of objects or points with similar characteristics are grouped in clusters

- Cluster analysis

A statistical classification technique for exploratory data analysis in which a set of objects with similar characteristics are grouped in clusters; in this work, the technique was used for grouping similar kinds of factors into respective categories

- Cluster heatmap

A visualization technique used to reveal hierarchical clusters in data matrix by drawing a rectangular grid corresponding to rows and columns and coloring the cells by their values in the data matrix; this technique has high data density and reveals clusters better than unordered heatmaps alone

- Discharge Abstract Database

Captures administrative, clinical, and demographic information on hospital discharges (including deaths, sign-outs, and transfers); data is received directly from acute care facilities or their respective health/regional authority or ministry/department of health

- Factor

A set of observed variables that have similar response patterns; they are associated with a hidden variable (called a confounding variable) that is not directly measured

- Factor analysis

A statistical technique that takes a mass of data and finds hidden patterns shows how those patterns overlap and what characteristics are seen in multiple patterns

- False discovery rate

A statistical method of conceptualizing the rate of type I errors in null hypothesis testing when conducting multiple comparisons

- Glasgow Coma Scale

A calculated scale that determines a patient's level of consciousness based on the best eye-opening response, the best verbal response, and the best motor response

- International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, with Canadian Enhancements

A coding system, developed by the World Health Organization that is used to classify diseases and related health problems (morbidity); includes enhancements developed by the Canadian Institute for Health Information for use in Canadian hospitals and other Canadian medical facilities

- Heatmaps

Depict relationships between two variables, one plotted on each axis; by observing how cell colors change across each axis, one can observe if there are any patterns in value for one or both variables

- National Ambulatory Care Reporting System

Contains data for all hospital-based and community-based ambulatory care: day surgery, outpatient and community-based clinics, emergency departments

- Traumatic brain injury

A disruption in the brain's normal function by a bump, blow, or jolt to the head or penetrating head injury

- Surveillance (in injury)

Refers to the ongoing collection of data describing the occurrence of, and factors associated with, injury

Author contributions

A.C., T.M., V.C. and M.D.E. conceived the original concept and initiated the work. M.D.E designed and optimized statistical analyses for this work. A.T. and M.S. carried out the analyses with the support of M.D.E. T.M. optimized reporting. All authors discussed the results biweekly and further steps for analyses and interpretation. T.M. wrote the manuscript. All authors read the paper and commented on the text.

Data availability

ICES is an independent, non-profit research institute funded by an annual grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (MOHLTC). As a prescribed entity under Ontario's privacy legislation, ICES is authorized to collect and use health care data for the purposes of health system analysis, evaluation and decision support. Secure access to these data is governed by policies and procedures that are approved by the Information and Privacy Commissioner of Ontario. The dataset from this study is held securely in coded form at the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences (ICES). While data sharing agreements prohibit ICES from making the dataset publicly available, access may be granted to those who meet pre-specified criteria for confidential access, available at www.ices.on.ca/DAS. The full dataset creation plan and underlying analytic code are available from the authors upon request, understanding that the computer programs may rely upon coding templates or macros that are unique to ICES and are therefore either inaccessible or may require modification.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-022-08782-0.

References

- 1.World Health Organization (1946). Preamble to the Constitution of the World Health Organization as adopted by the international health conference, New York, 19–22 June 1946. http://www.who.int/about/ definition/en/print.html

- 2.McCartney G, Popham F, McMaster R, Cumbers A. Defining health and health inequalities. Public Health. 2019;172:22–30. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2019.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huber, M. et al. How should we define health? BMJ (Clinical research ed.)343, d4163 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Maas AIR, et al. Traumatic brain injury: integrated approaches to improve prevention, clinical care, and research. Lancet Neurol. 2017;16(12):987–1048. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(17)30371-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borgen, I., Røe, C., Brunborg, C., Tenovuo, O., Azouvi, P., Dawes, H., Majdan, M., Ranta, J., Rusnak, M., Eveline, J., Tverdal, C., Jacob, L., Cogné, M., Steinbuechel, N. V., Andelic, N., & CENTER-TBI participants and investigators (2020). Care transitions in the first 6 months following traumatic brain injury: Lessons from the CENTER-TBI study. Annals of physical and rehabilitation medicine, S1877–0657(20)30217–7. Advance online publication. https://doi-org.myaccess.library.utoronto.ca/10.1016/j.rehab.2020.10.009

- 6.Mollayeva T, Sutton M, Chan V, Colantonio A, Jana S, Escobar M. Data mining to understand health status preceding traumatic brain injury. Sci. Rep. 2019;9(1):5574. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-41916-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Masel BE, DeWitt DS. Traumatic brain injury: a disease process, not an event. J. Neurotrauma. 2010;27(8):1529–1540. doi: 10.1089/neu.2010.1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gravesteijn, B. Y. et al. Collaborative European NeuroTrauma Effectiveness Research for Traumatic Brain Injury Collaborators. Toward a new multi-dimensional classification of traumatic brain injury: a collaborative european neurotrauma effectiveness research for traumatic brain injury study. J. Neurotrauma37(7), 1002–1010 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Weaver JL. The brain-gut axis: A prime therapeutic target in traumatic brain injury. Brain Res. 2021;1753:147225. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2020.147225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fatuki TA, Zvonarev V, Rodas AW. Prevention of Traumatic Brain Injury in the United States: Significance, New Findings, and Practical Applications. Cureus. 2020;12(10):e11225. doi: 10.7759/cureus.11225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O'Rand AM. Cumulative processes in the life course. In: Elder GH, Giele JZ, editors. The craft of life course research. Guilford; 2009. pp. 121–140. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seeking precision in public health. Nat. Med. 25(8), 1177 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Furman D, Campisi J, Verdin E, Carrera-Bastos P, Targ S, Franceschi C, Ferrucci L, Gilroy DW, Fasano A, Miller GW, Miller AH, Mantovani A, Weyand CM, Barzilai N, Goronzy JJ, Rando TA, Effros RB, Lucia A, Kleinstreuer N, Slavich GM. Chronic inflammation in the etiology of disease across the life span. Nat. Med. 2019;25(12):1822–1832. doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0675-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Salter MW, Stevens B. Microglia emerge as central players in brain disease. Nat. Med. 2017;23(9):1018–1027. doi: 10.1038/nm.4397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lehallier B, et al. Undulating changes in human plasma proteome profiles across the lifespan. Nat. Med. 2019;25(12):1843–1850. doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0673-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pugh MJ, et al. Complex comorbidity clusters in OEF/OIF veterans: the polytrauma clinical triad and beyond. Med. Care. 2014;52(2):172–181. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cimino AN, et al. The Effect of Intimate Partner Violence and Probable Traumatic Brain Injury on Mental Health Outcomes for Black Women. J. Aggr. Maltreatment Trauma. 2019;28(6):714–731. doi: 10.1080/10926771.2019.1587657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Langer KG. Early history of Amnesia. Front. Neurol. Neurosci. 2019;44:64–74. doi: 10.1159/000494953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Steyerberg, E. W. et al. CENTER-TBI Participants and Investigators. Case-mix, care pathways, and outcomes in patients with traumatic brain injury in CENTER-TBI: A European prospective, multicentre, longitudinal, cohort study. Lancet. Neurol.18(10), 923–934 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Cota MR, Moses AD, Jikaria NR, Bittner KC, Diaz-Arrastia RR, Latour LL, Turtzo LC. Discordance between documented criteria and documented diagnosis of traumatic brain injury in the emergency department. J. Neurotrauma. 2019;36(8):1335–1342. doi: 10.1089/neu.2018.5772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Williams SA, et al. Plasma protein patterns as comprehensive indicators of health. Nat. Med. 2019;25(12):1851–1857. doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0665-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sussman ES, Pendharkar AV, Ho AL, Ghajar J. Mild traumatic brain injury and concussion: Terminology and classification. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 2018;158:21–24. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-63954-7.00003-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rabinowitz AR, Li X, McCauley SR, Wilde EA, Barnes A, Hanten G, Mendez D, McCarthy JJ, Levin HS. Prevalence and predictors of poor recovery from mild traumatic brain injury. J. Neurotrauma. 2015;32(19):1488–1496. doi: 10.1089/neu.2014.3555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Polinder S, Cnossen MC, Real R, Covic A, Gorbunova A, Voormolen DC, Master CL, Haagsma JA, Diaz-Arrastia R, von Steinbuechel N. A multidimensional approach to post-concussion symptoms in mild traumatic brain injury. Front. Neurol. 2018;9:1113. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2018.01113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.ICES | Quality assessment of administrative data. Assessed April 15, 2021 at: https://www.ices.on.ca/flip-publication/quality-assessment-of-administrative/files/assets/basic-html/page8.html

- 26.Population and dwelling counts, for Canada, provinces and territories, 2016 and 2011 censuses. Statistics Canada. Assessed April 15, 2021 at: https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/dp-pd/hlt-fst/pd-pl/Table.cfm?Lang=Eng&T=101&SR=1&S=3&O=D#tPopDwell

- 27.The Canadian Coding Standards. Assessed April 15, 2021 at: https://secure.cihi.ca/estore/productSeries.htm?pc=PCC189

- 28.International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th Revision. Assessed April 15, 2021 at: https://icd.who.int/browse10/2019/en#/

- 29.Corrigan JD, Kreider S, Cuthbert J, Whyte J, Dams-O'Connor K, Faul M, Harrison-Felix C, Whiteneck G, Pretz CR. Components of traumatic brain injury severity indices. J Neurotrauma. 2014;31(11):1000–1007. doi: 10.1089/neu.2013.3145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gagné M, Moore L, Sirois MJ, Simard M, Beaudoin C, Kuimi BL. Performance of International Classification of Diseases-based injury severity measures used to predict in-hospital mortality and intensive care admission among traumatic brain-injured patients. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2017;82(2):374–382. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000001319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Coronado, V.G., Xu,L., Basavaraju, S.V. et al. Centers for disease control and prevention. Surveillance for Traumatic Brain Injury-Related Deaths - United States, 1997–2007/ 60(SS05); 1–32. Retrieved May 20, 2021 from: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/ss6005a1.htm [PubMed]

- 32.Association of Public Health Epidemiologists in Ontario. Recommended ICD-10-CA Codes for Injury Indicators. Assessed March 15, 2021 at: http://core.apheo.ca/index.php?pid=306

- 33.Mollayeva T, Hurst M, Chan V, Escobar M, Sutton M, Colantonio A. Pre-injury health status and excess mortality in persons with traumatic brain injury: A decade-long historical cohort study. Prevent. Med. 2020;139:106213. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2020.106213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ogura T, Yanagimoto T. Improving and extending the McNemar test using the Bayesian method. Stat. Med. 2016;35(14):2455–2466. doi: 10.1002/sim.6875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Benjamini Y, Yekutieli D. The control of the false discovery rate in multiple hypothesis testing under dependency. Ann. Stat. 2001;29(4):1165–1188. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hochberg Y, Benjamini Y. More powerful procedures for multiple significance testing. Stat. Med. 1990;9:811–818. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780090710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang S, Sarcevic A, Farneth RA, Chen S, Ahmed OZ, Marsic I, Burd RS. An approach to automatic process deviation detection in a time-critical clinical process. J. Biomed. Inform. 2018;85:155–167. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2018.07.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhao X, Guo J, Nie F, Chen L, Li Z, Zhang H. Joint principal component and discriminant analysis for dimensionality reduction. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2020;31(2):433–444. doi: 10.1109/TNNLS.2019.2904701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Martínez-Camblor P, Pardo-Fernández JC. Smooth time-dependent receiver operating characteristic curve estimators. Stat. Methods Med. Res. 2018;27(3):651–674. doi: 10.1177/0962280217740786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zetterqvist J, Vermeulen K, Vansteelandt S, Sjölander A. Doubly robust conditional logistic regression. Stat. Med. 2019;38(23):4749–4760. doi: 10.1002/sim.8332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Meunier B, Dumas E, Piec I, Béchet D, Hébraud M, Hocquette JF. Assessment of hierarchical clustering methodologies for proteomic data mining. J. Proteome Res. 2007;6(1):358–366. doi: 10.1021/pr060343h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Huang, Y., Chang, X., Zhang, Y., Chen, L., & Liu, X. (2020). Disease characterization using a partial correlation-based sample-specific network. Briefings bioinf., bbaa062. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43.Bu J, Liu W, Pan Z, Ling K. Comparative study of hydrochemical classification based on different hierarchical cluster analysis methods. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020;17(24):9515. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17249515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lambert A. Probability of fixation under weak selection: A branching process unifying approach. Theor. Popul. Biol. 2006;69(4):419–441. doi: 10.1016/j.tpb.2006.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thompson, P. M. et al. ENIGMA Consortium. ENIGMA and global neuroscience: A decade of large-scale studies of the brain in health and disease across more than 40 countries. Transl. Psychiatr.10(1), 100 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.Marois G, Aktas A. Projecting health-ageing trajectories in Europe using a dynamic microsimulation model. Sci. Rep. 2021;11(1):1785. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-81092-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Braveman, P., & Gottlieb, L. (2014). The social determinants of health: it's time to consider the causes of the causes. Public health reports (Washington, D.C.: 1974), 129 Suppl 2(Suppl 2), 19–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Chan V, Mollayeva T, Ottenbacher KJ, Colantonio A. Clinical profile and comorbidity of traumatic brain injury among younger and older men and women: A brief research notes. BMC. Res. Notes. 2017;10(1):371. doi: 10.1186/s13104-017-2682-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kaplan GB, Leite-Morris KA, Wang L, Rumbika KK, Heinrichs SC, Zeng X, Wu L, Arena DT, Teng YD. Pathophysiological bases of comorbidity: Traumatic brain injury and post-traumatic stress disorder. J. Neurotrauma. 2018;35(2):210–225. doi: 10.1089/neu.2016.4953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pugh MJ, Finley EP, Copeland LA, Wang CP, Noel PH, Amuan ME, Parsons HM, Wells M, Elizondo B, Pugh JA. Complex comorbidity clusters in OEF/OIF veterans: the polytrauma clinical triad and beyond. Med. Care. 2014;52(2):172–181. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Noyes ET, Tang X, Sander AM, Silva MA, Walker WC, Finn JA, Cooper DB, Nakase-Richardson R. Relationship of medical comorbidities to psychological health at 2 and 5 years following traumatic brain injury (TBI) Rehabil. Psychol. 2020 doi: 10.1037/rep0000366.Advanceonlinepublication. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Xiong C, Hanafy S, Chan V, Hu ZJ, Sutton M, Escobar M, Colantonio A, Mollayeva T. Comorbidity in adults with traumatic brain injury and all-cause mortality: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2019;9(11):e029072. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-029072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yang Y, Hu X, Zhang Q, Zou R. Diabetes mellitus and risk of falls in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Age Ageing. 2016;45(6):761–767. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afw140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.de Vries M, Seppala LJ, Daams JG, van de Glind E, Masud T, van der Velde N, EUGMS Task and Finish Group on Fall-Risk-Increasing Drugs Fall-risk-increasing drugs: a systematic review and meta-analysis: I. Cardiovascular drugs. J. Am. Med. Direct. Assoc. 2018;19(4):371.e1–371.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2017.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mehdizadeh S, Sabo A, Ng KD, Mansfield A, Flint AJ, Taati B, Iaboni A. Predicting short-term risk of falls in a high-risk group with dementia. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2020;22(3):689–695.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2020.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mehta R, Trainee GP, Chinthapalli K. Glasgow coma scale explained. BMJ Clin. Res. ed. 2019;365:11296. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l1296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.DiGiorgio AM, Wittenberg BA, Crutcher CL, 2nd, Kennamer B, Greene CS, Velander AJ, Wilson JD, Tender GC, Culicchia F, Hunt JP. The Impact of drug and alcohol intoxication on glasgow coma scale assessment in patients with traumatic brain injury. World Neurosurg. 2020;135:e664–e670. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2019.12.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yue JK, Robinson CK, Winkler EA, Upadhyayula PS, Burke JF, Pirracchio R, Suen CG, Deng H, Ngwenya LB, Dhall SS, Manley GT, Tarapore PE. Circadian variability of the initial Glasgow Coma Scale score in traumatic brain injury patients. Neurobiol. Sleep Circadian Rhythms. 2016;2:85–93. doi: 10.1016/j.nbscr.2016.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gang MC, Hong KJ, Shin SD, Song KJ, Ro YS, Kim TH, Park JH, Jeong J. New prehospital scoring system for traumatic brain injury to predict mortality and severe disability using motor Glasgow Coma Scale, hypotension, and hypoxia: a nationwide observational study. Clin. Exp. Emerg. Med. 2019;6(2):152–159. doi: 10.15441/ceem.18.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Coplin WM, Pierson DJ, Cooley KD, Newell DW, Rubenfeld GD. Implications of extubation delay in brain-injured patients meeting standard weaning criteria. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2000;161(5):1530–1536. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.5.9905102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Williamson T, Ryser MD, Ubel PA, Abdelgadir J, Spears CA, Liu B, Komisarow J, Lemmon ME, Elsamadicy A, Lad SP. Withdrawal of life-supporting treatment in severe traumatic brain injury. JAMA Surg. 2020;155(8):723–731. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2020.1790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Akavipat P, Thinkhamrop J, Thinkhamrop B, Sriraj W. Parameters affecting length of stay among neurosurgical patients in an intensive care unit. Acta Med. Indones. 2016;48(4):275–281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kouloulas, E. J., Papadeas, A. G., Michail, X., Sakas, D. E., & Boviatsis, E. J. (2013). Prognostic value of time-related Glasgow coma scale components in severe traumatic brain injury: a prospective evaluation with respect to 1-year survival and functional outcome. International journal of rehabilitation research. Internationale Zeitschrift fur Rehabilitationsforschung. Revue internationale de recherches de readaptation, 36(3), 260–267. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 64.Kim, D. Y., & Pyun, S. B. (2019). Prediction of functional outcome and discharge destination in patients with traumatic brain injury after post-acute rehabilitation. International journal of rehabilitation research. Internationale Zeitschrift fur Rehabilitationsforschung. Revue internationale de recherches de readaptation, 42(3), 256–262. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 65.Chan V, Mollayeva T, Ottenbacher KJ, Colantonio A. Sex-Specific predictors of inpatient rehabilitation outcomes after traumatic brain injury. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2016;97(5):772–780. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2016.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bertrand PM, Pereira B, Adda M, Timsit JF, Wolff M, Hilbert G, Gruson D, Garrouste-Orgeas M, Argaud L, Constantin JM, Chabanne R, Quenot JP, Bohe J, Guerin C, Papazian L, Jonquet O, Klouche K, Delahaye A, Riu B, Zieleskiewicz L, Lautrette A. Disagreement between clinicians and score in decision-making capacity of critically Ill patients. Crit. Care Med. 2019;47(3):337–344. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jørgensen TS, Hansen AH, Sahlberg M, Gislason GH, Torp-Pedersen C, Andersson C, Holm E. Falls and comorbidity: The pathway to fractures. Scand. J. Public Health. 2014;42(3):287–294. doi: 10.1177/1403494813516831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fasano A, Canning CG, Hausdorff JM, Lord S, Rochester L. Falls in Parkinson's disease: A complex and evolving picture. Movem. Disorders Offic. J. Movem. Disorder Soc. 2017;32(11):1524–1536. doi: 10.1002/mds.27195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Vaca FE, Li K, Tewahade S, Fell JC, Haynie DL, Simons-Morton BG, Romano E. Factors contributing to delay in driving licensure among U.S. high school students and young adults. J. Adolesc. Health. Offic. Publ. Soc. Adolesc. Med. 2021;68(1):191–198. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Willems LM, Reif PS, Knake S, Hamer HM, Willems C, Krämer G, Rosenow F, Strzelczyk A. Noncompliance of patients with driving restrictions due to uncontrolled epilepsy. Epilepsy & behavior : E&B. 2019;91:86–89. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2018.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lenardt MH, Garcia A, Binotto MA, Carneiro N, Lourenço TM, Cechinel C. Non-frail elderly people and their license to drive motor vehicles. Rev. Bras. Enferm. 2018;71(2):350–356. doi: 10.1590/0034-7167-2016-0675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mainor AJ, Morden NE, Smith J, Tomlin S, Skinner J. ICD-10 coding will challenge researchers: Caution and collaboration may reduce measurement error and improve comparability over time. Med. Care. 2019;57(7):e42–e46. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000001010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ishiguro, L., Saskin, R., Vermeulen, M. J., Yates, E., Gunraj, N., & Victor, J. C. (2016). Increasing Access to Health Administrative Data with ICES Data & Analytic Services. Healthcare Q. (Toronto, Ont.), 19(1), 7–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 74.Schull MJ, Azimaee M, Marra M, Cartagena RG, Vermeulen MJ, Ho M, Guttmann A. ICES: Data, discovery, better health. Int. J. Popul. Data Sci. 2020;4(2):1135. doi: 10.23889/ijpds.v4i2.1135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bang F, McFaull S, Cheesman J, Do MT. The rural-urban gap: differences in injury characteristics. Écart entre milieu rural et milieu urbain: différences dans les caractéristiques des blessures. Health promot. Chronic Disease Prevent. Canada Res. Policy Practice. 2019;39(12):317–322. doi: 10.24095/hpcdp.39.12.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.McClure RJ. Injury Prevention: Where to from here? Injury Prevent. J. Int. Soc. Child Adolesc. Injury Prevent. 2018;24(1):1. doi: 10.1136/injuryprev-2017-042695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Vella MA, Crandall ML, Patel MB. Acute management of traumatic brain injury. Surg. Clinics North Am. 2017;97(5):1015–1030. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2017.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zonfrillo MR. "Tertiary Precision Prevention" for concussion: Customizing care by predicting outcomes. J. Pediatr. 2016;174:6–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.04.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Norman AH, Tesser CD. Quaternary prevention: A balanced approach to demedicalisation. British J. General Practice J. R College Gener. Pract. 2019;69(678):28–29. doi: 10.3399/bjgp19X700517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Liu-Ambrose T, Davis JC, Best JR, Dian L, Madden K, Cook W, Hsu CL, Khan KM. Effect of a home-based exercise program on subsequent falls among community-dwelling high-risk older adults after a fall: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2019;321(21):2092–2100. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.5795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Perttila NM, Öhman H, Strandberg TE, Kautiainen H, Raivio M, Laakkonen ML, Savikko N, Tilvis RS, Pitkälä KH. Effect of exercise on drug-related falls among persons with Alzheimer's disease: A secondary analysis of the FINALEX study. Drugs Aging. 2018;35(11):1017–1023. doi: 10.1007/s40266-018-0594-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Barker, A. L., Morello, R. T., Wolfe, R., Brand, C. A., Haines, T. P., Hill, K. D., Brauer, S. G., Botti, M., Cumming, R. G., Livingston, P. M., Sherrington, C., Zavarsek, S., Lindley, R. I., & Kamar, J. (2016). 6-PACK programme to decrease fall injuries in acute hospitals: cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ (Clinical research ed.), 352, h6781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 83.Matchar DB, Duncan PW, Lien CT, Ong M, Lee M, Gao F, Sim R, Eom K. Randomized controlled trial of screening, risk modification, and physical therapy to prevent falls among the elderly recently discharged from the emergency department to the community: The steps to avoid falls in the elderly study. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2017;98(6):1086–1096. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2017.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ailabouni N, Mangin D, Nishtala PS. DEFEAT-polypharmacy: deprescribing anticholinergic and sedative medicines feasibility trial in residential aged care facilities. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2019;41(1):167–178. doi: 10.1007/s11096-019-00784-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Moore M, Winkelman A, Kwong S, Segal SP, Manley GT, Shumway M. The emergency department social work intervention for mild traumatic brain injury (SWIFT-Acute): A pilot study. Brain Inj. 2014;28(4):448–455. doi: 10.3109/02699052.2014.890746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Zatzick D, Russo J, Lord SP, Varley C, Wang J, Berliner L, Jurkovich G, Whiteside LK, O'Connor S, Rivara FP. Collaborative care intervention targeting violence risk behaviors, substance use, and posttraumatic stress and depressive symptoms in injured adolescents: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168(6):532–539. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.4784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Addison M, Mcgovern R, Angus C, Becker F, Brennan A, Brown H, Coulton S, Crowe L, Gilvarry E, Hickman M, Howel D, Mccoll E, Muirhead C, Newbury-Birch D, Waqas M, Kaner E. Alcohol Screening and Brief Intervention in police custody suites: Pilot cluster randomised controlled trial (AcCePT) Alcohol alcohol. (Oxford, Oxfordshire) 2018;53(5):548–559. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agy039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]