Abstract

Background—

More than 3 million individuals receive treatment for alcohol and/or substance use disorder (AUD/SUD) each year, yet there exists no standardized method for measuring patient success in treatment. Quantifying a more comprehensive assessment of treatment outcomes could identify the relative efficacy of different treatment strategies for individuals with AUD/SUDs, and help patients to identify, in advance, appropriate treatment options.

Methods—

This study developed and embedded patient-reported outcome measures into the routine clinical operations of a residential treatment program. Surveys assessed demographics, drug use history, physical and mental health, and quality of life. Outcomes were assessed among participants at admission (n=961) and in patients who completed the survey at time of discharge (n=633).

Results—

Past 30-day alcohol and/or opioid use at admission were correlated with worse self-reported physical and mental health, sleep, and quality of life, and greater negative affect and craving (ps<.05). Previous history of treatment and/or withdrawal management were associated with worse self-reported physical and mental health, quality of life, and increased craving (ps<.05). Physical and mental health improved across timepoints and was most pronounced when comparing persons receiving treatment for opioid use disorder (OUD) versus AUD, wherein persons with OUD had worse physical health at all time points, and greater sleep disturbance and negative affect at discharge (ps<.05).

Conclusion—

It is feasible to embed patient outcome monitoring into routine clinic operations, which could be used in the future to tailor treatment plans.

Keywords: substance use disorder, alcohol use disorder, residential, outcome, recovery

1. INTRODUCTION

In 2018, more than 20 million people over the age of 12 were diagnosed with a substance used disorder (SUD), the two most common being alcohol use disorder (AUD, 14.8 million) and opioid use disorder (OUD, 2 million).1 More than 3 million individuals are estimated to be receiving treatment for an AUD/SUD annually.1 The intensity of AUD/SUD treatment ranges from relatively infrequent outpatient visits to long-term inpatient/residential care and can include myriad programs ranging from individual or group counseling to medically supervised withdrawal management. The most commonly utilized treatment programs in the United States nationally are ambulatory non-intensive outpatient (48.4%), followed by 24-hour residential withdrawal management programs (16.4%), ambulatory intensive outpatient programs (12.5%), and short-term (<30 days) residential programs (9.4%).2

In addition to the diversity of treatments available, no standardized methods for assessing patient success exist and the vast majority of AUD/SUD outcome assessments are specific to outcomes for an individual drug; such outcomes have poor applicability to real-world treatment settings which generally treat a variety of AUD/SUDs concurrently and in persons presenting for the treatment of polysubstance use. A variety of composite AUD/SUD measures do exist, including the Addiction Severity Assessment Tool3, the Brief Addiction Monitor4, the Brief Treatment Outcome Measure5, the Maudsley Addiction Profile6, yet no one assessment has emerged as the clear standard for comprehensive monitoring of patients receiving treatment. The lack of standardization slows improvement of care strategies and makes it difficult for patients to understand the relative utility of different treatment approaches.7, 8 It also limits the understanding of how treatments may impact different domains of patient health (AUD/SUD, and non-AUD/SUD outcomes), and identification of which patient-specific factors (e.g., demographic, AUD/SUD experience) might be used to predict patient response to different treatment types. Moreover, many composite assessments are focused primarily on abstinence and/or socioeconomic indicators,9–11 which may be appealing because they are relatively objective and/or easily standardized, but can lead to discrepancies between a clinician or researcher’s assessment and the perceived experience of the patients themselves. The recent focus in clinical medicine on collecting patient-reported outcomes further supports the expansion of AUD/SUD assessment beyond objective measures such as urine drug screens to include self-reported benefits of treatment. These efforts have been shown to improve communication between patients and clinicians, and improve the quality of care being delivered.12–14 Only a few studies in the AUD/SUD field have reported on the use of comprehensive patient-reported outcomes.15

Quality of life (QOL) is an important patient-reported outcome for capturing changes in non-substance related outcomes among persons receiving treatment for AUD/SUD.16–17 QOL measures can be used to complement outcomes related to AUD/SUD to provide a holistic understanding of functioning among persons being treated for AUD/SUD18 and ultimately improve treatment strategies. The WHO defines QOL as “individuals’ perception of their position in life in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards and concerns”, and identify physical health, mental health, social relationships, and environment as important QOL domains.19 Additional AUD/SUD-specific QOL measures, such as craving, have been recommended to help further elucidate the recovery experience for persons with AUD/SUD.20–21

This study addressed these concerns by developing and embedding a comprehensive patient-reported outcomes assessment system that included information related to AUD/SUD as well as QOL, into the routine care operations of a 28-day residential AUD/SUD treatment clinic. Eight total outcome measures were used to assess physical health, mental health, sleep disturbance, craving, social function, mood, and general QOL at treatment entry and periodic follow-ups. We hypothesized this format would provide comprehensive evaluation of patient status while being feasible to conduct in a real-world treatment setting. The three primary aims of the current analyses are to 1) examine the association between these QOL outcomes and patient-specific factors at the time of admission, 2) assess for trends in these self-reported outcomes from admission to discharge (treatment effect), and 3) compare the outcomes in the context of AUD and OUD to understand if there are any meaningful differences between these large patient subgroups. These data will help inform the use of general outcomes for monitoring routine care of patients being treated for SUD.

2. METHODS

2.1. Treatment Setting

The setting for this study was a private 118-bed residential treatment program that provides >28-day inpatient care for adult (>18 years) men and women who have private or public insurance and presented for the treatment of AUD and/or SUDs. The program takes a holistic approach to promoting AUD/SUD abstinence by offering a variety of multi-modal, empirically-supported treatments that are customized for the needs of individual patients. Medical (including medically-supervised withdrawal), psychological and psychiatric, and spiritual care programs are provided, and services in place at the time of the survey included acupuncture managed withdrawal, acupuncture, art and music therapy, counseling (individual, group, family), drumming circle, fitness, massage, meditation, pain management, religious services, and yoga.

Patients were designated at admission to one or more of the following subprograms based upon their specific needs: primary treatment, relapse management (for readmissions), emerging adult, women’s extended care, emerging adult extended care, and pain recovery. Each respective subprogram shared a common core of therapies, namely 1–2x weekly individual counseling, 2–4x daily group counseling and/or 12-step meetings, and medical management of physical and psychiatric symptoms. Pharmacotherapy for AUD or OUD was provided depending on individual needs and may have included medical withdrawal management, acamprosate, disulfiram, naltrexone, and buprenorphine taper or maintenance.

2.2. Integration of Survey into Routine Operations

An informed consent was embedded into the standard intake documents to inform patients they would be asked questions during and after treatment, that they could choose whether to answer questions, and that there would be no consequences for not answering questions. Study questions were programmed as a web-based survey hosted on Qualtrics (Provo, UT) and were collected using iPad or related tablets. Patients were assigned a unique non-identifying number to aid tracking but were not asked to input any protected health information (PHI) or answer questions that would require prompt reporting (e.g., suicidality). Non-PHI demographic information was included in the survey for ease of future analyses (and to prevent the need to integrate the data with the electronic medical record). A brief training was incorporated into the beginning of the admission survey to inform patients how to complete different question types (e.g., sliding scale, multiple choice) and staff were available to assist patients as needed. Surveys were administered at admission and discharge and for quality control purposes, patients were asked at each survey time point whether they had experienced computer problems or had other reasons for why their data should not be used.

2.3. Outcome Assessment

2.3.1. Overview:

Data for these analyses were collected between July 2016 and May 2018. These analyses are conducted as part of a quality improvement project and only include data from persons aged 18 or older. Since data were collected as part of an internal quality monitoring program, compensation for survey completion was not provided.

The assessment battery was comprised of 62 questions pertaining to individual treatment experience (e.g., “did you utilize group counseling?”) and items from public domain measures; questions that had substantial overlap with other items were removed in the interest of brevity.

2.3.2. AUD/SUD Outcomes:

AUD/SUD was assessed using the Brief Addiction Monitor (BAM4), a 17-item, self-report measure that assessed past 30-day functioning using a 5-item (e.g., Excellent – Poor) ordinal scale. Domains evaluated include physical and mental health, sleep, mood, alcohol/substance use, craving, adequate income, social support, and satisfaction with recovery. Individual scale items pertaining to physical health, mood, sleep, and craving were evaluated here, with higher scores representing more severe problems. Since patients were receiving supervised, residential care, questions pertaining to AUD/SUD frequency were considered irrelevant and not included in the discharge survey.

2.3.3. QOL Outcomes:

QOL was assessed using the Global Health Scale (GHS) form from the Patient Reported Outcome Measurement System (PROMIS, NIH), a 10-question self-report measure that rates items on a 5-item (e.g., Excellent – Poor) ordinal scale. The PROMIS-GHS was modified here from the original 7-day period to reflect a 30-day period. Scores were converted to T-scores (normalized for comparison across populations), from which summary subscale ratings of quality of life, social functioning, physical health, and mental health were derived. Lower scores correspond to more severe problems.

2.4. Statistical Analyses

Demographic characteristics and AUD/SUD experience were examined descriptively and compared between patients who did (n=663) and did not (n=298) complete the discharge survey. Pearson correlations using admission data, controlled for age and gender, were used to examine whether any admission-level demographics (age, race, gender, marital status, employment, incarceration history) or AUD/SUD use history (number of self-reported past 30-day alcohol use, opioid use, treatment attempts, withdrawal management [“detoxification”] attempts) were correlated with BAM physical health, negative affect, sleep disturbance, and craving ratings and the PROMIS-GHS physical health, mental health, quality of life, and social functioning subscales. These data provided both a means to determine whether outcomes were consistent with expected norms, as well as insight into the issues faced by persons entering AUD/SUD treatment. Correlations were run using p-values set at 0.05 and then with Bonferroni-adjusted p-values of <.001.

Changes in functioning between admission and discharge were then evaluated within the subset of participants who completed the discharge assessment battery using a repeated measures analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) that controlled for age and gender22–24 and applied Greenhouse-Geisser corrections. Repeated measures ANCOVAs were used because parametric tests are often more robust in analyzing Likert scales that are ordinal, have 3–5 possible responses, and have an N>30.25–27 Finally, two-way repeated measures ANOCVAs were used to assess group differences and interactions among persons presenting with primary AUD or OUD at admission, using the same methods described but including primary drug as a between-subjects variable. All analyses were conducted using SPSS version 25 (IBM, Armonk, NY) and alpha levels were set to p<0.05.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Patient Characteristics

A total of 961 patients completed the admission survey, and 663 (69.0%) completed the discharge survey and were included in repeated measures analyses. Patients at admission were 65.2% male, 91.3% European ancestry, 38.2 average years of age (SD = 13.7), with 62.1% being employed (Table 1). Alcohol (68.6%) and opioid use (36.9%) were the most frequently endorsed primary SUDs at admission. Past 30 days frequency of use, as assessed using the BAM, for alcohol was 1–3 (15.7%), 4–8 (12.9%), 9–15 (21.4%), and 16–30 (50.0%) days and for opioids was 1–3 (32.2%), 4–8 (22.7%), 9–15 (18.9%), and 16–30 (26.2%) days.

Table 1.

Comparison of Patients Who Did and Did Not Complete Discharge Survey

| Total Sample (N=961) | Completed (N=663) | Did not complete (N=298) | p-valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic Characteristics | ||||

| Age in years (mean, SD) | 38.2 (13.7) | 38.7 (13.7) | 37.7 (13.6) | 0.322 |

| Male (%) | 65.2 | 63.2 | 67.2 | 0.19 |

| Race (%) | ||||

| White/Caucasian | 91.3 | 92.9 | 89.6 | 0.22 |

| Black/African American | 4.7 | 3.9 | 5.4 | |

| Other | 4.4 | 3.7 | 5.0 | |

| Hispanic Ethnicity (%) | 2.4 | 2.3 | 2.4 | 0.93 |

| Married (%) | 37.7 | 39.5 | 35.9 | 0.29 |

| Employedb (%) | 62.1 | 66.4 | 57.7 | 0.01 |

| Substance Use Characteristics | ||||

| Primary Substance Use (%) | ||||

| Alcohol | 68.6 | 73.0 | 64.1 | <.01 |

| Opioids | 36.9 | 33.4 | 40.3 | 0.05 |

| Cannabis | 19.4 | 17.9 | 20.8 | 0.3 |

| Cocaine | 17.7 | 17.6 | 17.8 | 0.96 |

| Stimulants | 6.8 | 6.9 | 6.7 | 0.9 |

| Treatments, # Lifetime (mean, SD) | 1.5 (2.3) | 1.5 (2.3) | 1.5 (2.2) | 0.89 |

| Withdrawal management, # Lifetime (mean, SD)c | 1.3 (2.2) | 1.4 (2.2) | 1.2 (2.2) | 0.33 |

| Anti-craving medications (%) | 32.6 | 35.0 | 30.1 | 0.2 |

| Family involved in recovery (%) | 23.8 | 22.3 | 25.2 | 0.42 |

| Cigarette smoker (%) | 62.2 | 60.0 | 64.4 | 0.04 |

| Cigarettes per day (mean, SD) | 13.0 (8.2) | 12.1 (8.4) | 13.8 (8.0) | 0.02 |

| Brief Addiction Monitor (mean, SD) | ||||

| Use (range 0–12) | 6.5 (3.0) | 6.6 (2.9) | 6.3 (3.1) | 0.14 |

| Risk (range 0–24) | 12.6 (4.0) | 12.5 (4.1) | 12.6 (3.9) | 0.77 |

| Protect (range 0–24) | 13.6 (4.3) | 14.1 (4.1) | 13.1 (4.4) | <.01 |

| General Health Characteristics | ||||

| EDd, days past 90 days (mean, SD) | 0.84 (1.8) | 0.73 (1.3) | 0.95 (2.2) | 0.06 |

| PROMIS Global Health (mean T score, SD) | ||||

| Mental Health | 38.0 (8.5) | 38.6 (8.5) | 37.3 (8.4) | 0.04 |

| Physical Health | 44.8 (7.7) | 45.2 (7.6) | 44.3 (7.8) | 0.08 |

Persons who did and did not complete discharge survey are compared using independent groups t-tests (continuous) and chi-squares (dichotomous)

Employed includes full-time, part-time, and active military

Withdrawal management was previously known as “detoxification”

ED=emergency department

Comparisons of patients who did and did not complete the discharge survey revealed persons who did not complete it were significantly more likely to not be employed, were less likely to present for alcohol treatment and more likely to present for opioid treatment, were more likely to smoke cigarettes and smoked more per day, had fewer protective factors, as rated by the BAM, and greater mental health severity as rated by the PROMIS-GHS compared to persons who completed both surveys. Patients not completing the discharge survey also trended towards having worse physical health ratings as assessed by the BAM and had spent more time in the emergency department in the 90 days preceding admission than those who did complete both surveys.

3.2. Correlates with AUD/SUD and QOL Measures at Time of Admission

Pearson’s correlation analyses conducted at the time of admission revealed that frequency of recent substance use, history of receiving AUD/SUD treatment, and/or medically-supervised withdrawal were correlated with ratings on the BAM and PROMIS-GHS outcomes (Table 2). Greater opioid use at admission showed the strongest correlation and was significantly correlated with more severe outcomes on all BAM and PROMIS-GHS measures evaluated. In contrast, greater alcohol use was significantly correlated with poorer ratings on the PROMIS-GHS mental health score, and several BAM ratings (e.g., physical health, mood, and cravings), but not PROMIS-GHS QOL, social functioning, or physical health scales. The total number of times the patient had been treated for AUD/SUD in their lifetime, and the number of times they had undergone supervised withdrawal were also associated with poor physical health, mental health, and craving on BAM and PROMIS-GHS scales, suggesting that more frequent interactions with AUD/SUD treatment was associated with a lower QOL at time of admission (Table 2). None of the demographic variables evaluated were significantly associated with BAM or PROMIS-GHS ratings.

Table 2.

Partial Correlations Between Substance Use Measures are Patient-reported Outcomes at Admission

| Lifetime Treatment (#) | Lifetime Withdrawal managementa (#) | Alcohol Use Frequency (past 30 days) | Opioid Use Frequency (past 30 days) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BAM Physical Health | 0.072 (.03) | 0.117 (<.001) | 0.072 (.028) | 0.146 (<.001) |

| BAM Sleep | 0.004 | 0.043 | 0.026 | 0.098 (.003) |

| BAM Mood | 0.091 (.005) | 0.094 (.004) | 0.122 (<.001) | 0.102 (.002) |

| BAM Cravings | 0.139 (<.001) | 0.126 (<.001) | 0.180 (<.001) | 0.182 (<.001) |

| PROMIS QOL | −0.116 (<.001) | −0.102 (.002) | −0.013 | −0.159 (<.001) |

| PROMIS Physical Health T-score | −0.113 (.001) | −0.131 (<.001) | 0.075 (.02) | −0.172 (<.001) |

| PROMIS Mental Health T-score | −0.109 (.001) | −0.101 (.002) | −0.082 (.013) | −0.125 (<.001) |

Values represent correlations and p-values in parentheses. Partial correlations adjusted for age and gender. P-values provided for outcomes significant at p<.05, Bonferroni adjusted p-values set threshold for significance at p<.001.

BAM = Brief Addiction Monitor; PROMIS = Patient Reported Outcome Measurement System; QOL = Quality of Life

Withdrawal management was previously known as “detoxification”

3.3. Differences Between Admission and Discharge

A repeated-measures ANCOVA, controlling for age and gender, found that between admission and discharge patients experienced a significant improvement in self-reported physical health (F1, 623 = 98.62, p<0.001), and a reduction in the number of days reporting sleep disturbance (F1,623 = 39.83, p<.001), negative affect (F1, 623 = 45.82, p<0.001), and drug/alcohol craving (F1, 623 = 85.15, p<0.001) as determined by the BAM (Figure 1). PROMIS-GHS physical (F1, 623 = 53.04, p<0.001) and mental (F1, 623 = 138.12, p<0.001) health T scores also significantly improved over time (Figure 2). Participants also self-reported an improvement in QOL (F1, 623 = 119.99, p<0.001) and social functioning (F1,623 = 31.44, p<0.001) (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Brief Addiction Monitor Outcomes.

Symptom resolution of Brief Addiction Monitor (BAM) outcomes for substance use disorder patients in a 28-day residential treatment program. Outcomes included physical health (upper left); negative affect (upper right); sleep disturbance (lower left); and craving (lower right). All outcomes used a 5-point Likert scale (0 to 4) with a higher score reflecting greater severity. Statistical testing consisted of Repeated-measures ANCOVAs controlling for age and gender. *** = p<0.001.

Figure 2. PROMIS Global Health Outcomes.

Symptom resolution of Patient Reported Outcome Measurement System (PROMIS) variables for substance use disorder patients in a 28-day residential treatment program. Outcomes included physical health (upper left); mental health (upper right); quality of life (lower left); and social functioning (lower right). Physical and mental health measurements were based on the associated PROMIS-Global Health Score T-score scoring system with higher score reflecting more optimal physical and mental health; dashed line reflects national norms. Quality of life and social functioning measurements were based on a 5-point Likert scale (1 to 5) with higher scores reflecting higher quality of life. Statistical testing consisted of Repeated-measures ANCOVAs controlling for age and sex. *** = p<0.001.

3.4. Difference Between Persons Being Treated for AUD and OUD

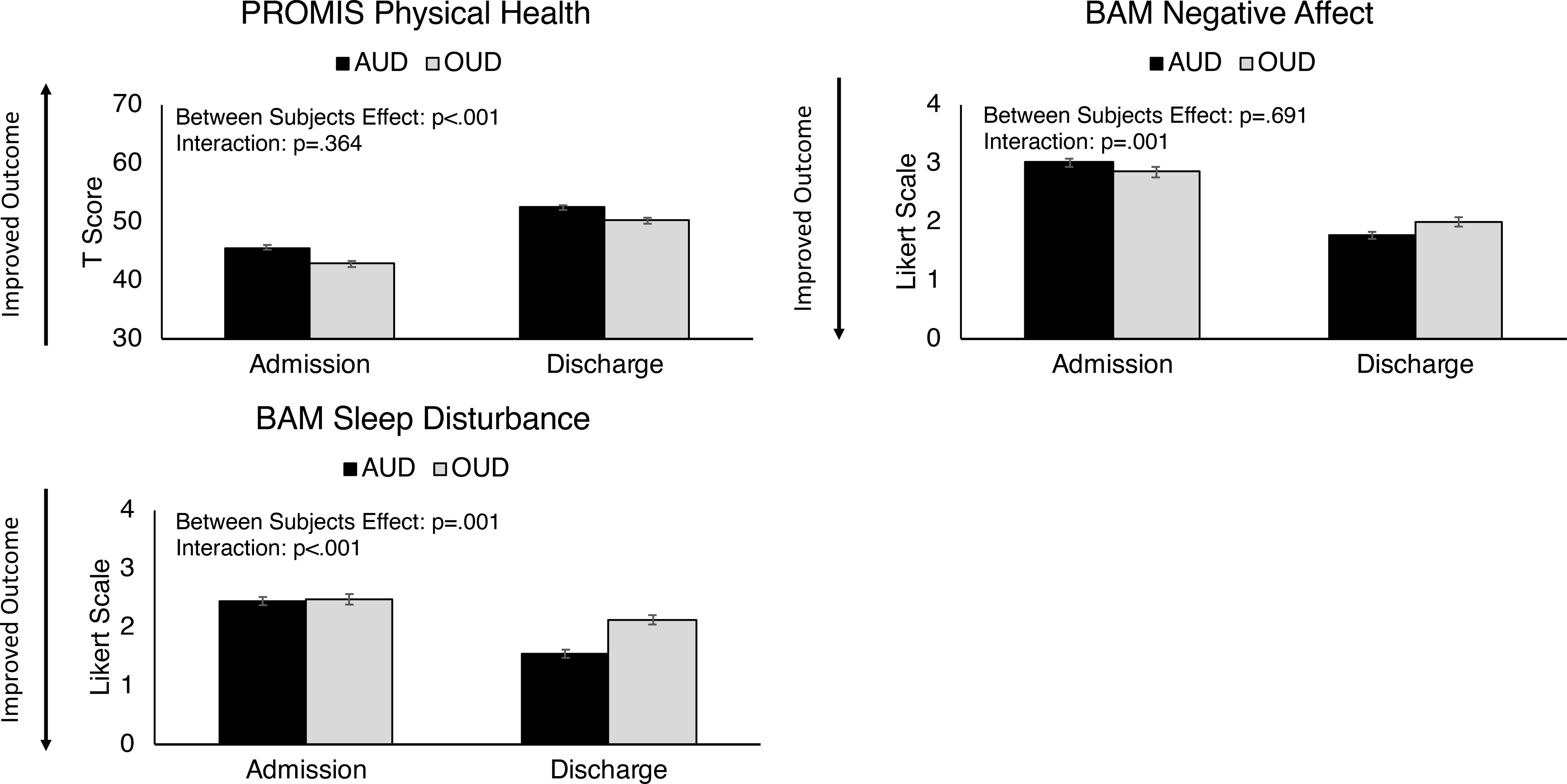

Differences in PROMIS-GHS and BAM outcomes between admission and discharge were further examined as a function of presenting with primary AUD (n=323) or primary OUD (n=208). Two-way repeated measures ANCOVAs, controlling for age and gender, revealed that persons with primary OUD reported worse physical health across time points as compared to persons with primary AUD (Figure 3). Group x time point interactions were also observed on BAM measures of sleep disturbance and negative affect, such that persons with primary OUD reported greater sleep disturbance and more negative affect than persons with primary AUD at discharge, suggesting that sleep disturbance and negative affect are more likely to be persistent issues in persons with OUD in residential treatment (Figure 3). No other significant main effects or interactions between these groups were observed.

Figure 3. Differences between AUD and OUD Patients.

Comparison of alcohol use disorder (AUD) and opioid use disorder (OUD) patients on Patient Reported Outcome Measurement System (PROMIS) and Brief Addiction Monitor (BAM) outcomes. Statistical analyses consisted of two-way repeated measures ANCOVAs examining between-group differences and interaction effects. Filled circles represent AUD time points and shaded squares represent OUD time points.

4. Discussion

This study developed and embedded a structured AUD/SUD and QOL-based outcomes assessment into the routine operations of a residential AUD/SUD treatment program. Data collected during admission and discharge were examined to evaluate the degree to which patient reports at admission reflected what might be expected (as evidence of assessment utility), and whether changes occurred as a function of time and primary substance (alcohol vs. opioids). The battery incorporated important patient-reported domains that extended beyond abstinence to include general functioning and QOL. Results revealed important differences in patients who did and did not complete the discharge survey, suggesting it may be possible to identify persons at risk for survey noncompliance at treatment presentation (e.g., persons presenting for treatment for opioids, or who were experiencing more mental health distress). The data revealed associations between greater physical and/or mental health problems on the PROMIS-GHS and more days of alcohol and/or opioid use prior to admission; significant improvements in QOL and mental health outcomes pre and post-treatment; and greater sleep disturbances and negative affect in persons presenting for OUD versus AUD treatment.

Despite lack of association between demographic variables and patient-reported ratings at admission, measures of drug use severity (e.g., history of prior treatment and withdrawal attempts, days of alcohol and/or opioid use) were associated with poorer functioning. The lack of association between baseline functioning and demographics with was surprising, however the homogeneity of the sample (primarily white, married, and employed) may explain those results. The lack of diversity in this sample limits evaluation of how social determinants of health may be associated with treatment outcomes.28 Nevertheless, evidence that greater severity of substance use at admission was associated with more severe problems is consistent with prior reports and provides insight into the issues faced by these patients that can be used to help direct treatment plans.29, 30 It should also be noted, however, that the magnitude of correlations were small. It is therefore possible that the large sample size led to some variables achieving statistical significance but not at a level that would be considered clinically significant; this is an empirical question that warrants more exploration.

Direct comparisons of patients who completed admission and discharge surveys revealed significant improvements in QOL. This is significant because while prior studies have examined QOL during recovery, these data reflect changes that occurred during treatment. This information could be used therapeutically to show patients changes over time and inform them of potential improvements. These data also examined which outcomes varied in persons presenting with primary AUD and OUD, two substances that produce physical dependence and represent a large percentage of treatment admissions. Analyses revealed differences in sleep disturbance, negative affect, and self-reported physical health. Notably, though persons with OUD and AUD entered treatment with similar sleep problems, sleep disturbance was greater in persons with OUD versus AUD. Persons with OUD also exhibited greater negative affect at discharge relative to persons with AUD, suggesting they may experience a more recalcitrant set of mental health issues than persons with AUD. Finally, persons with OUD reported worse physical health throughout the study compared with persons with AUD, although symptoms improved at a similar rate across groups. These data suggest that persons with OUD and AUD might benefit from different types and foci of care to support long-term recovery.

The strengths of this study included the embedding of data collection into routine clinical operations of a residential treatment clinic and a within-subject evaluation of a large subset of that sample who both assessments. The study also had some notable limitations. Though embedding the admissions and discharge data collection in routine clinical operations allowed for structure and optimized self-reporting, the data collection had to be intentionally brief in the context of a clinical visit, making it difficult to more thoroughly evaluate the trends observed in the data. The study would also be strengthened further with robust monitoring post-discharge to assess for persistent of treatment effects and relapse and other clinically-important outcomes. Current recommendations suggest following patients for up to 5 years post-treatment to assess the long-term effects, and future studies should aim to collect longitudinal data on patient across treatment settings.31, 32 The lack of AUD/SUD assessments at discharge prevented evaluation of changes in those domains and should be considered for future efforts to support comparison to non-residential treatment paradigms. Finally, the lack of integration of the survey and medical records prevents the reason for discharge from being evaluated, though comparisons of persons who did and did not complete the discharge survey did reveal meaningful risk factors for noncompliance that could be used clinically to improve completion rates.

5. Conclusion

This study adds to the limited empirical literature on the use of comprehensive outcomes assessments of persons receiving care for AUD/SUD. The initiation of the survey was prompted by a shift in the healthcare field towards value-based care, for which understanding the quality of care being provided is crucial. At that time, no model program existed and no commercially-available systems were available for use in AUD/SUD settings. This survey was designed to be brief, comprehensive, focused on patient-reported outcomes, and empirically-supported while also being operational in a real-world treatment program without the need for additional staff members, substantial training, or staff burden. Incorporation of an informed consent process into treatment admission, careful elimination of PHI and reportable items, and inclusion of important demographics into the survey to avoid merging the data with a medical record extends analyses opportunities. The ability to customize survey questions to specific treatment services will enable value-based care-level evaluations that will help the facility refine its offerings and begin customizing care to patients based upon collected evidence.

Since the launch of this survey, commercial vendors have begun to market outcome assessment options that offer an even more hands-off approach to programs interested in these evaluations. However, for programs interested in developing their own onsite survey programs, the information provided here outlines the key methods and outcomes used, as well as evidence that the data collected here conformed to expected norms, detected changes pre and post-treatment, and distinguished between different patient subpopulations. Future research that evaluates the relationship between individual therapeutic programs offered within the residential center, patient adherence to those programs, and corresponding changes observed in treatment outcomes, will be useful for refining and customizing treatment programs for patients. Ultimately, this study demonstrated feasibility of embedding a comprehensive patient-reported survey into routine clinical operations and found that quantifying symptom resolution during treatment can reveal important directions for future research on precision medicine in this population.

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff members at Ashley Addiction Treatment for their efforts in collecting these survey data.

Conflicts of Interest:

JGH and BS are employed by the facility, JF is on the board of trustees, and AH receives research funding from Ashley Addiction Treatment through his university. KED received salary support from Ashley Addiction Treatment to develop the survey outlined in this paper and in the past 3 years, KED has conducted unrelated consulting for MindMed, Inc, Canopy, and Beckley-Canopy.

References

- 1.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2019). Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (HHS Publication No. PEP19–5068, NSDUH Series H-54). Rockville, MD: Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality,Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Retrieved from https://www.samhsa.gov/dat [Google Scholar]

- 2.Treatment Episode Data Set: Admissions (TEDS-A-2017) | SAMHDA. Accessed May 9, 2020. https://www.datafiles.samhsa.gov/study/treatment-episode-data-set-admissions-teds-2017-nid18473 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Butler SF, Budman SH, McGee MD, Davis MS, Cornelli R, Morey LC. Addiction severity assessment tool: development of a self-report measure for clients in substance abuse treatment. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005. Dec 12;80(3):349–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cacciola JS, Alterman AI, Dephilippis D, Drapkin ML, Valadez C Jr, Fala NC, Oslin D, McKay JR. Development and initial evaluation of the Brief Addiction Monitor (BAM). J Subst Abuse Treat. 2013. Mar;44(3):256–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lawrinson P, Copeland J, Indig D. Development and validation of a brief instrument for routine outcome monitoring in opioid maintenance pharmacotherapy services: the brief treatment outcome measure (BTOM). Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005. Oct 1;80(1):125–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marsden J, Gossop M, Stewart D, Best D, Farrell M, Lehmann P, Edwards C, Strang J. The Maudsley Addiction Profile (MAP): a brief instrument for assessing treatment outcome. Addiction. 1998. Dec;93(12):1857–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deady M A Review of Screening, Assessment and Outcome Measures for Drug and Alcohol Settings. Network of Alcohol & Other Drug Agencies. Available at: https://www.drugsandalcohol.ie/18266/1/NADA_A_Review_of_Screening%2C_Assessment_and_Outcome_Measures_for_Drug_and_Alcohol_Settings.pdf; last accessed August 6, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Loflin MJE, Kiluk BD, Huestis MA, Aklin WM, Budney AJ, Carroll KM, D’Souza DC, Dworkin RH, Gray KM, Hasin DS, Lee DC, Le Foll B, Levin FR, Lile JA, Mason BJ, McRae-Clark AL, Montoya I, Peters EN, Ramey T, Turk DC, Vandrey R, Weiss RD, Strain EC. The state of clinical outcome assessments for cannabis use disorder clinical trials: A review and research agenda. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2020. Jul 1;212:107993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Edwards AC, Ohlsson H, Sundquist J, Sundquist K, Kendler KS. Socioeconomic sequelae of drug abuse in a Swedish national cohort. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2020. Jul 1;212:107990. Epub 2020 Apr 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gossop M, Marsden J, Stewart D, Rolfe A. Treatment retention and 1 year outcomes for residential programmes in England. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1999;57(2):89–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schuman-Olivier Z, Claire Greene M, Bergman BG, Kelly JF. Is residential treatment effective for opioid use disorders? A longitudinal comparison of treatment outcomes among opioid dependent, opioid misusing, and non-opioid using emerging adults with substance use disorder. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2014;144:178–185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frost MH, Bonomi AE, Cappelleri JC, Schünemann HJ, Moynihan TJ, Aaronson NK. Applying Quality-of-Life Data Formally and Systematically Into Clinical Practice. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 2007;82(10):1214–1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lohr KN, Zebrack BJ. Using patient-reported outcomes in clinical practice: challenges and opportunities. Qual Life Res. 2008;18(1):99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dassow PL. Measuring performance in primary care: what patient outcome indicators do physicians value? J Am Board Fam Med. 2007. Jan-Feb;20(1):1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pasareanu AR, Opsal A, Vederhus J-K, Kristensen Ø, Clausen T. Quality of life improved following in-patient substance use disorder treatment. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2015;13(1):35. doi: 10.1186/s12955-015-0231-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tiffany ST, Friedman L, Greenfield SF, Hasin DS, Jackson R. Beyond Drug Use: A Systematic Consideration of Other Outcomes in Evaluations of Treatments for Substance Use Disorders. Addiction. 2012;107(4):709–718. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03581.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garnick DW, Horgan CM, Acevedo A, McCorry F, Weisner C. Performance measures for substance use disorders--what research is needed? Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2012;7:18. doi: 10.1186/1940-0640-7-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Laudet AB. The Case for Considering Quality of Life in Addiction Research and Clinical Practice. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2011;6(1):44–55. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.WHO | The World Health Organization Quality of Life (WHOQOL). WHO. Available at: http://www.who.int/mental_health/publications/whoqol/en/; last accessed August 5, 2021 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tiffany ST, Wray JM. The clinical significance of drug craving. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2012;1248:1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sayette MA, Shiffman S, Tiffany ST, Niaura RS, Martin CS, Shadel WG. The measurement of drug craving. Addiction. 2000;95(Suppl 2):S189–S210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beekman ATF, Kriegsman DMW, Deeg DJH, van Tilburg W. The association of physical health and depressive symptoms in the older population: age and sex differences. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1995;30(1):32–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Conn V, Taylor SG, Abele PB. Myocardial infarction survivors: age and gender differences in physical health, psychosocial state and regimen adherence. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1991;16(9):1026–1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hopman WM, Harrison MB, Coo H, Friedberg E, Buchanan M, VanDenKerkhof EG. Associations between chronic disease, age and physical and mental health status. Chronic Diseases in Canada. 2009;29(2):10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mircioiu C, Atkinson J. A Comparison of Parametric and Non-Parametric Methods Applied to a Likert Scale. Pharmacy (Basel). 2017;5(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Norman G Likert scales, levels of measurement and the “laws” of statistics. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2010;15(5):625–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sullivan GM, Artino AR Jr. Analyzing and Interpreting Data From Likert-Type Scales. Journal of Graduate Medical Education. 2013;5(4):541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Swendsen J, Conway KP, Degenhardt L, et al. Socio-demographic risk factors for alcohol and drug dependence: the 10-year follow-up of the national comorbidity survey. Addiction. 2009;104(8):1346–1355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ciraulo DA, Piechniczek-Buczek J, Iscan EN. Outcome predictors in substance use disorders. Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2003;26(2):381–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McKay JR, Foltz C, Stephens RC, Leahy PJ, Crowley EM, Kissin W. Predictors of alcohol and crack cocaine use outcomes over a 3-year follow-up in treatment seekers. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2005;28(2, Supplement):S73–S82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.DuPont RL, Compton WM, McLellan AT. Five-Year Recovery: A New Standard for Assessing Effectiveness of Substance Use Disorder Treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2015;58:1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McLellan T What is recovery? Revisiting the Betty Ford Institute Consensus Panel definition: The Betty Ford Consensus Panel and Consultants. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2010;38(2):200–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]