Abstract

Escherichia coli R170, isolated from the urine of an infected patient, was resistant to expanded-spectrum cephalosporins, aztreonam, ciprofloxacin, and ofloxacin but was susceptible to amikacin, cefotetan, and imipenem. This particular strain contained three different plasmids that encoded two β-lactamases with pIs of 7.0 and 9.0. Resistance to cefotaxime, ceftazidime, aztreonam, trimethoprim, and sulfamethoxazole was transferred by conjugation from E. coli R170 to E. coli J53-2. The transferred plasmid, RZA92, which encoded a single β-lactamase, was 150 kb in length. The cefotaxime resistance gene that encodes the TLA-1 β-lactamase (pI 9.0) was cloned from the transconjugant by transformation to E. coli DH5α. Sequencing of the blaTLA-1 gene revealed an open reading frame of 906 bp, which corresponded to 301 amino acid residues, including motifs common to class A β-lactamases: 70SXXK, 130SDN, and 234KTG. The amino acid sequence of TLA-1 shared 50% identity with the CME-1 chromosomal class A β-lactamase from Chryseobacterium (Flavobacterium) meningosepticum; 48.8% identity with the VEB-1 class A β-lactamase from E. coli; 40 to 42% identity with CblA of Bacteroides uniformis, PER-1 of Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and PER-2 of Salmonella typhimurium; and 39% identity with CepA of Bacteroides fragilis. The partially purified TLA-1 β-lactamase had a molecular mass of 31.4 kDa and a pI of 9.0 and preferentially hydrolyzed cephaloridine, cefotaxime, cephalothin, benzylpenicillin, and ceftazidime. The enzyme was markedly inhibited by sulbactam, tazobactam, and clavulanic acid. TLA-1 is a new extended-spectrum β-lactamase of Ambler class A.

The main mechanism of resistance to β-lactam antibiotics in members of the family Enterobacteriaceae is the production of β-lactamases (21, 35). Expanded-spectrum cephalosporins (cefotaxime, ceftazidime) have been specifically designed to resist degradation by the older broad-spectrum β-lactamases such as TEM-1, TEM-2, and SHV-1. With the use of these antibiotics in vivo, extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs) have been selected; these ESBLs most often are mutants of these older enzymes and carry a limited number of amino acid substitutions (G. Jacoby and K. Bush, http://www.lahey.org/studies /webt.htm). There is also a small but growing family of plasmid-mediated ESBLs that are not related to TEM or SHV β-lactamases, such as CTX-M (3–6, 10, 14, 15) and Toho (17, 23), that preferentially hydrolyze cefotaxime and that belong to Ambler class A. In addition, there has been a worldwide emergence of novel β-lactamases, mainly among members of the family Enterobacteriaceae, that hydrolyze expanded-spectrum β-lactams. While they maintain the main properties of the class A β-lactamases, they are not closely related to the TEM, SHV, or CTX-M families of β-lactamases. Most of these ESBLs are plasmid mediated and include the PER-1, PER-2, VEB-1, CblA, and CepA enzymes. These β-lactamases are not species specific, since they have also been isolated from clinically significant gram-negative species that are not members of the family Enterobacteriaceae. These new resistance genes can be disseminated within microbial populations by a variety of gene transfer mechanisms.

During 1992 and 1993, several multidrug-resistant clinical isolates of the family Enterobacteriaceae from different hospitals at Mexico City were identified as ESBL producers by their increased susceptibility to β-lactams in the presence of clavulanic acid (36). From these isolates, one group of strains produced a plasmid-mediated β-lactamase with a pI of 9.0 that was not related to the TEM or SHV family. One of these isolates, Escherichia coli R170, was used for the molecular characterization of the enzyme. In this work, we report on a new plasmid-mediated cefotaxime-hydrolyzing β-lactamase of Ambler class A, designated TLA-1.

(This study was presented at the 39th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, San Francisco, Calif., 26 to 29 September 1999.)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

E. coli R170 was isolated in 1991 from the urine of a hospitalized patient in Mexico City. The strain was identified as E. coli by using the API 20E system (BioMerieux). E. coli J53-2 (pro met Rifr) was the recipient strain for conjugal transfer and β-lactamase purification. E. coli DH5α was the host strain for the cloning experiments.

Conjugation.

Mating was performed as described by Miller (26) with strain J53-2. Mixed cultures (10:1, recipient:donor) were incubated at 30°C overnight. Transconjugants were selected on Luria agar supplemented with rifampin (100 μg/ml) and cefotaxime (1 μg/ml), and the plates were incubated at 37°C for 18 h.

Plasmid isolation.

To isolate large plasmids, DNA was extracted by the method described by Kieser (20). DNA was visualized after vertical electrophoresis in 0.7% agarose gels with 1× TBE (Tris-borate-EDTA) buffer at 150 V for 6 h. Bands were visualized by staining the gel with ethidium bromide. Plasmids RP4 (54 kb), R1 (92 kb), and pLac (152 kb) were used as molecular size markers. For small plasmids, the Wizard Plus SV minipreps DNA purification system from Promega was used.

Susceptibility testing.

The MICs of antibiotics were determined by the broth microdilution method with the combo 20 panel (Dade MicroScan) and by the agar dilution method in Mueller-Hinton agar by using current National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards recommendations (27). The organisms were grown overnight in Luria agar, diluted to a density of 107 CFU/ml in saline solution for use as an inoculum, and spotted with a Steers multiple inoculator (104 CFU per spot). The plates were incubated at 35°C for 18 h. The MICs were determined with the antibiotics alone or in combination with clavulanic acid at 2 μg/ml. The following antibiotics were provided as standard powders by the indicated laboratory suppliers: cefotaxime and cefpirome, Hoechst-Marion-Roussel, Romainville, France), ceftazidime (Glaxo Wellcome, Mexico City, Mexico), aztreonam and cefepime (Bristol-Myers Squibb, Mexico City, Mexico), and clavulanic acid (SmithKline Beecham Pharmaceuticals, Mexico City, Mexico).

Nucleic acid techniques and sequence analysis.

DNA isolation, restriction enzyme digestions, recombinant DNA manipulations, and transformation of plasmid DNA were performed as described by Sambrook et al. (34). The cefotaxime resistance gene was cloned as follows. Total DNA from the X170 transconjugant was partially digested with Sau3AI. The products obtained were separated in a sucrose gradient (40 to 10%). Fragments ranging in length from 10 to 5 kb were ligated into the BamHI site of vector pBGS18 (38), which carries a kanamycin resistance gene. Strain DH5α was transformed with the ligated DNA by electroporation, and transformants were selected on Luria agar supplemented with 1 μg of cefotaxime per ml. A transformant containing a plasmid with an 11-kb insert (pCA11000) was obtained. From this insert, a 3-kb fragment encoding a β-lactamase was subcloned with EcoRI-PstI into pBGS18, and the plasmid was named pCA3000. Sequencing of the DNA was performed with the Sequenase, version 2.0, from Amersham by primer walking (34). Analysis was performed with GCG software by searching sequence databases with the BLASTx program (EMBL, SwissProt, and PIR databases). Multiple alignment was performed with the Clustal W program (39).

Isoelectric focusing.

Sonic extracts of cultures and the partially purified enzyme were subjected to analytical isoelectric focusing over pH ranges of 3 to 9 and 8 to 10 by the method of Matthew et al. (25).

TLA-1 β-lactamase purification.

E. coli J53-2(pCA3000) was grown in 1 liter of Luria-Bertani broth with cefotaxime (1 μg/ml) at 37°C for 18 h. Bacterial cells were harvested by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. The pellet was washed with 10 mM Tris-HCl–30 mM NaCl (pH 8.0) and was centrifuged again for 10 min, and the pellet was suspended in 100 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.4). Cell-free extracts were obtained by sonication (20 cycles/min for 30 min; Sonifier 450; VWR Scientific) at 4°C. Cell debris was eliminated by centrifugation (120,000 × g 1 h at 4°C), and the supernatant was dialyzed overnight at 4°C against 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 6.2). The dialyzed extract was applied to a carboxymethyl-Sepharose CL-6B (Sigma Chemical) column equilibrated with 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 6.2). After the column was washed with the same buffer, protein elution was performed with a linear gradient of NaCl (0 to 1 M in the same buffer). Fractions containing the highest levels of β-lactamase activity, as tested with nitrocefin as the substrate, were pooled and dialyzed overnight at 4°C against 20 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.0). This sample was concentrated by ultrafiltration with Centriprep-10 membranes (Amicon, Lexington, Mass.), and the filtrate was stored at −70°C.

Kinetics study.

β-Lactamase activity for different substrates was measured by a spectrophotometric assay in a Beckman DU-7 spectrophotometer. The λmaxs of the substrates used were as follows: benzylpenicillin, 240 nm; cephaloridine, 300 nm; ceftazidime, 260 nm; aztreonam, 320 nm; cephalothin, 262 nm; cefotaxime, 260 nm; cefoxitin, 260 nm; imipenem, 297 nm; and cefepime, 258 nm. Clavulanic acid, sulbactam, and tazobactam inhibitors were provided by SmithKline Beecham Pharmaceuticals; Pfizer Inc., New York, N.Y.; and Wyeth, Mexico City, Mexico, respectively. The enzymatic activity was measured at room temperature by recording the decrease in absorbance of each antibiotic in 100 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) by using 1-ml quartz cells. The reaction was started with the addition of 5 μl of the partially purified enzyme (0.87 mg/ml). The initial velocities at different antibiotic concentrations displayed hyperbolic behavior kinetics. These data were fitted to the Michaelis-Menten equation and competitive inhibition equations by using the Enzfiter program written by Robin J. Leatherbarrow (Elsevier, 1987) or the programs developed by Cleland (11) in a BASIC version obtained from the author's laboratory. The determination of relative Vmax and Km/Vmax values was described previously (16). The inhibition and the Ki values for tazobactam, sulbactam, and clavulanic acid were determined by incubating the purified enzyme for 3 min with different concentrations of each inhibitor (0, 0.1, 0.5, 1, 5, 10, 20, and 30 μM) and then measuring the hydrolysis of nitrocefin at 487 nm. The protein concentration of the cell extracts and the concentration of the partially purified β-lactamase were determined by the procedure described by Lowry et al. (22).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The sequence of TLA-1 has been given the GenBank accession no. AF148067.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Plasmid profile and conjugal transfer of cefotaxime.

Agarose gel electrophoresis showed that clinical isolate E. coli R170 contained three plasmids of 150, 120, and 77 kb. The transfer of cefotaxime resistance to J53-2 correlated with the largest plasmid (150 kb). The frequency of transfer was 1.5 × 10−5 transconjugants per donor cell. The 150-kb conjugal plasmid was designated RZA92, and the transconjugant was designated X170. Resistance to β-lactams, kanamycin, tetracycline, streptomycin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and chloramphenicol was cotransferred.

Antimicrobial susceptibility.

By using the broth microdilution (MicroScan) panel, clinical isolate E. coli R170 was found to be resistant to ampicillin, cephalothin, cefazolin, cefpodoxime, ceftriaxone, cefuroxime, cefotaxime, ceftazidime, ceftibuten, aztreonam, cefpirome, cefepime, ciprofloxacin, and ofloxacin, but it was susceptible to amikacin, cefotetan, and imipenem. The MICs of some β-lactam antibiotics and clavulanic acid as the inhibitor for E. coli strains R170, X170, and DH5α(pCA3000) and the respective parental strains are shown in Table 1. These results were obtained by the agar dilution method. The MICs of cefotaxime, ceftazidime, and aztreonam for X170 and DH5α(pCA3000) were increased from <0.125 μg/ml (parental strains) to 64 to >256 μg/ml. Meanwhile, the MICs of cefpirome and cefepime were increased from <0.125 to 1 to 8 μg/ml. The activities of cefotaxime, ceftazidime, and aztreonam were decreased at least 4- to 256-fold in the presence of clavulanic acid. This effect was less marked with cefpirome and cefepime. The effect of the inhibitor against the clinical isolate was not as strong as that against the rest of the strains (four- to eightfold lower), probably due to presence of the second β-lactamase. We also detected changes in the outer membrane protein pattern of the clinical isolate (data not shown); this suggests that, in addition to β-lactamase production, changes in the permeability of the outer membrane could increase the resistance levels of to all antimicrobial agents tested (30).

TABLE 1.

Antimicrobial susceptibilities of the clinical isolate, transconjugant, recombinant clone, and parental strains by agar dilution

| Druga | MIC (μg/ml) for strain, recombinant (pI):

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli R170, (7.0, 9.0) | E. coli J53-2, X170 (9.0) | E. coli DH5α(pCA3000) (9.0) | E. coli J53-2 | E. coli DH5α(pBGS18) | |

| Cefotaxime | >256 | 128 | 128 | <0.125 | <0.125 |

| Cefotaxime-clavulanic acid | 64 | 2 | 0.125 | <0.125 | <0.125 |

| Ceftazidime | >256 | >256 | 64 | 0.125 | <0.125 |

| Ceftazidime-clavulanic acid | 64 | 4 | 0.5 | 0.125 | <0.125 |

| Aztreonam | >256 | >256 | 64 | <0.125 | <0.125 |

| Aztreonam-clavulanic acid | 32 | 2 | 0.250 | <0.125 | <0.125 |

| Cefpirome | 128 | 8 | 2 | <0.125 | <0.125 |

| Cefpirome-clavulanic acid | 16 | 0.250 | <0.125 | <0.125 | <0.125 |

| Cefepime | 64 | 4 | 1 | <0.125 | <0.125 |

| Cefepime-clavulanic acid | 16 | 0.125 | <0.125 | <0.125 | <0.125 |

| Imipenem | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

A fixed concentration of clavulanic acid (2 μg/ml) was used.

Cloning and sequence analysis.

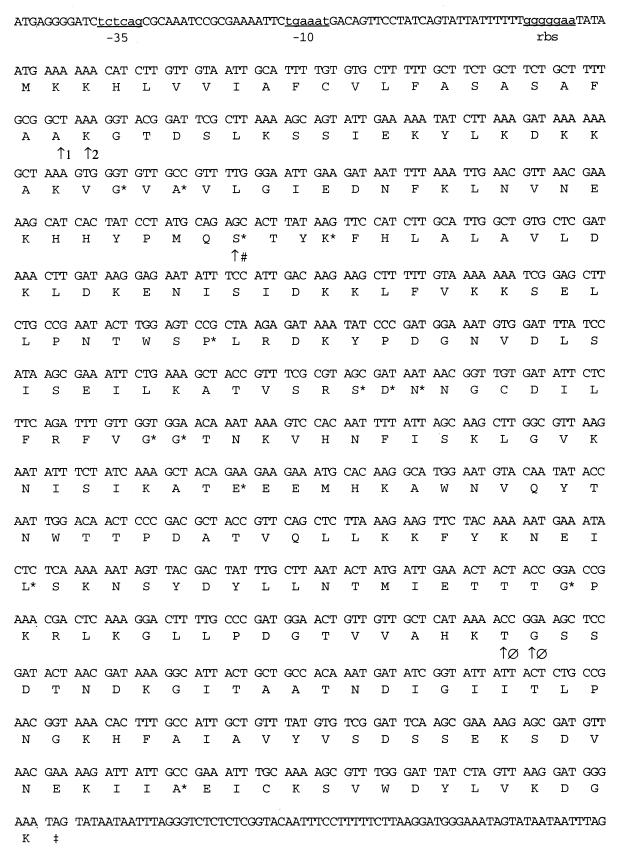

Restriction analysis of plasmid pCA3000 showed that the 3-kb insert had two HindIII sites. Then, the digestion of pCA3000 with HindIII and BamHI gave four fragments, fragments of 1.6, 1.4, and 0.050 kb and vector pBGS18. The two largest fragments were independently cloned in the same vector. In any of these recombinant plasmids, the β-lactamase activity and the resistance to cefotaxime were eliminated. These results suggested that at least one HindIII site was contained in the tla-1 gene. Sequencing and analysis revealed a new β-lactamase with an open reading frame of 906 bp with a 36% G+C content (Fig. 1). The enzyme coded by this gene was named TLA-1. A putative −35 and −10 promoter region was predicted with the program provided by Huerta et al. (A. M. Huerta, H. Salgado, F. Blattner, and J. Collado-Vides, personal communication). A putative consensus ribosome-binding site sequence (GGGGGAA) 4 bases upstream from the ATG codon was also predicted. Two possible signal peptide cleavage sites were predicted on the basis of the criteria established by Ambler et al. (2) and comparison with PER-1 and PER-2 protein sequences (12); one was found to be placed after Ala21, and the other was found to be placed after Gly23 (Fig. 1). For this reason the mature TLA-1 protein could be either 279 or 277 residues long, with a theoretical pI and molecular mass that was calculated as described by Bjellqvist et al. (8, 9) and that were approximately 8.98 and 31,271 Da, respectively, for the polypeptide of 279 residues.

FIG. 1.

Nucleotide sequence showing the coding region for tla-1 gene. The deduced amino acid sequence of tla-1 is shown below the nucleotide triplets. A possible promoter and the ribosome-binding site are underlined and are presented as lowercase letters. Several proposed sites for blaTLA-1 after multiple sequence alignments with the most closely related β-lactamases are shown. ∗, 100% conserved residues in the more related class A β-lactamases; ↑1, signal sequence cleavage site for Pseudomonas aeruginosa; ↑2, signal sequence cleavage site for Proteus mirabilis; ↑#, catalytic serine; ↑ø, substrate binding; ‡, stop codon.

TLA-1 identity with other β-lactamases.

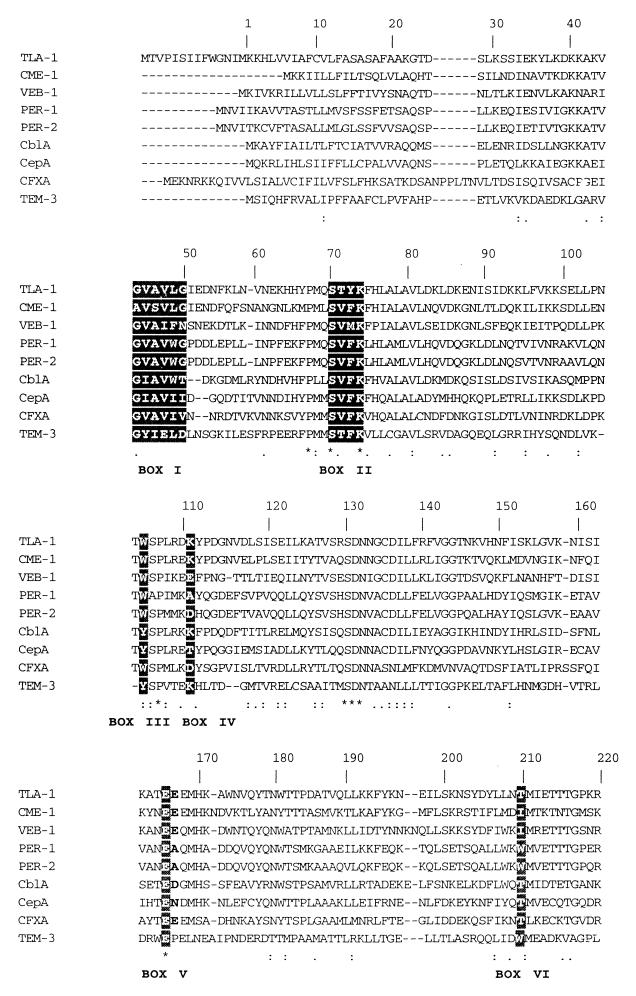

A search for protein sequences related to TLA-1 with BLASTx showed that TLA-1 belonged to the Ambler class A β-lactamases. Multiple alignment with the sequences with the highest scores and with TEM-3 showed that TLA-1 had the four conserved elements for class A β-lactamases according to Amber and colleagues (1, 2): the Ser-X-X-Lys consensus active-site serine residue at Ser70, the SDN loop at Ser130 (18), the conserved Glu166, and the KTG sequence at Lys234 (19). It is also relevant that in all the sequences shown in Fig. 2, an insertion of 7 amino acids was observed downstream from box VII (KTG) at about positions 251 and 257. It is noteworthy that the amino acid sequences of this region showed high degrees of identity between TLA-1 and CME-1 (33) and VEB-1 (31). Analysis of the blaTLA-1 gene showed that the TLA-1 β-lactamase was most closely related to CME-1 (33), with 50.1% identity, followed by VEB-1 (31) with 48.8% identity, CblA (37) with 42.5% identity, PER-1 (28) with 42.3% identity, PER-2 (7) with 41.7% identity, CepA (32) with 39.1% identity, CFXA (29) with 30% identity, and TEM-3 (24) with 30.2% identity.

FIG. 2.

Multiple alignment of the amino acid sequences of the closely related class A β-lactamases with that of TLA-1. Boxes I through VI correspond to those described by Joris et al. (19). The asterisks above the sequences indicate 100% conserved residues. Colons and periods indicate conserved and semiconserved residues, respectively. The lower trace represents the relative degree of conservation. TLA-1, E. coli (GenBank accession no. AF148067); CME-1, Chrysoebacterium meningosepticum (EMBL accession no. AJ006275); VEB-1, E. coli (EMBL accession no. O87489); PER-1, Pseudomonas aeruginosa (locus BLE1_PSEAE; SwissProt accession no. P37321); PER-2, Salmonella typhimurium (locus STBLAPER2; EMBL accession no. X93314); CBLA, Bacteroides uniformis (locus BLAC_BACUN; SwissProt accession no. P30898); CEPA, Bacteroides fragilis (GenBank accession no. L13472); CFXA, Bacteroides vulgatus (locus BLAC-BACVU; SwissProt accession no. P30899), TEM-3 (accession no. X64523). Gaps within the alignment are indicated by dashes.

Partial purification of TLA-1.

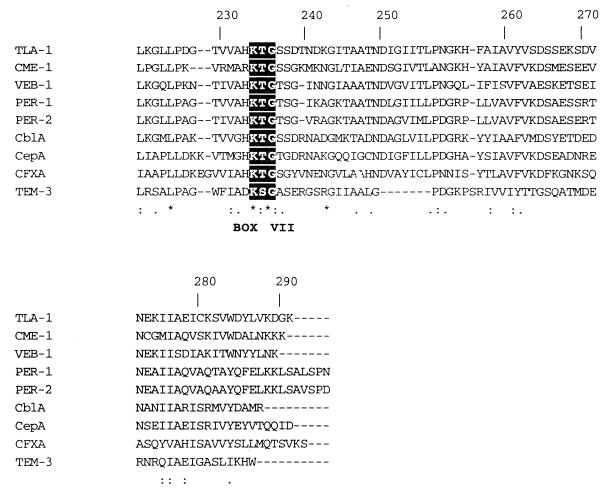

Enzyme purification was carried out by one-step cation-exchange chromatography. Electrophoresis by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis followed by Coomassie blue staining showed that most of the proteins were eliminated (Fig. 3, lane 2). This purification method yielded only one enriched band with a molecular mass of approximately 31,400 Da. Isoelectric focusing with nitrocefin as the substrate showed one band that corresponded to the calculated pI of 9.0 (data not shown). These results correlate with the predicted values for pI and molecular mass. The enzyme was purified 9.2-fold with a yield of 57%. The specific activity of partially purified β-lactamase was 3.02 U/mg (U is an international unit at 25°C) with cephaloridine as the substrate. This sample was used for the kinetic studies.

FIG. 3.

Gel electrophoresis of the partially purified β-lactamase TLA-1. Proteins were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (12% polyacrylamide) with Coomassie blue staining. Lane 1, E. coli J53-2(pCA3000) cell extract; lane 2, β-lactamase partially purified by cation-exchange chromatography; lane 3, molecular mass standards proteins. The migration position and molecular mass of markers proteins are shown at the right.

Kinetic study.

The results of the kinetic experiments of the TLA-1 β-lactamase for the β-lactams tested are described in Table 2. The TLA-1 β-lactamase was able to hydrolyze expanded-spectrum cephalosporins including ceftazidime and cefepime. The enzyme showed the highest level of activity (relative Vmax) against cephaloridine. However, the relatively high Km value for this substrate reduced the catalytic efficiency (Vmax/Km). One of the best substrates was cephalothin, which showed a higher affinity, and that high affinity in combination with the relative Vmax value resulted in the highest relative efficiency. By comparison of the results for TLA-1 with those for the CME-1 (33) and VEB-1 (31) β-lactamases, it is noteworthy that the efficiency pattern for TLA-1 was comparable to that for CME-1. Interestingly, the Km value for cefotaxime was very similar for the two enzymes. The hydrolytic activities against cephaloridine, ceftazidime, cefotaxime, cephalothin, and benzylpenicillin were similar for TLA-1, CME-1 (33), and VEB-1 (31). However, for ceftazidime, the Km of TLA-1 was the highest, resulting in a low relative catalytic efficiency. TLA-1 also showed good hydrolytic activity against aztreonam that, combined with a low Km, resulted in a relative catalytic efficiency similar to that observed with ceftazidime. These results correlate with the MIC data for ceftazidime and aztreonam (Table 1). TLA-1 had the highest Km and the lowest relative catalytic efficiency for cefepime compared to those for the other expanded-spectrum cephalosporins. This result suggested that the mechanism of resistance to cefepime was not due only to the activity of the β-lactamase. The hydrolytic activities of TLA-1 against imipenem and cefoxitin were not detectable. Similar to the situation observed with Toho-2 (17), the TLA-1 β-lactamase was more strongly inhibited by tazobactam than by clavulanic acid or sulbactam. In contrast, the VEB-1 β-lactamase was very susceptible to these inhibitors (31), while the Ki of CME-1 for clavulanic acid (33) was only 10 times lower than the Ki of TLA-1.

TABLE 2.

Kinetic parameters for TLA-1 β-lactamase for each β-lactam antibiotic and inhibitora

| Substrate | Km (μM) | Relative Vmaxb | Relative Vmax/Kmb | Ki (μM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benzylpenicillin | 36 ± 5.5c | 100 | 100 | |

| Cephalothin | 23 ± 4.1 | 83 | 130 | |

| Cephaloridine | 102 ± 13 | 238 | 84 | |

| Ceftazidime | 171 ± 38 | 110 | 22 | |

| Cefotaxime | 31 ± 9.8 | 97 | 113 | |

| Cefepime | 303 ± 63 | 44 | 5 | |

| Aztreonam | 58 ± 19 | 38 | 24 | |

| Cefoxitin | NDd | ND | ND | |

| Imipenem | ND | ND | ND | |

| Clavulanic acid | 3.36 | |||

| Sulbactam | 5.37 | |||

| Tazobactam | 0.69 |

Measurements were carried out in 100 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) at room temperature.

Values relative to the value for benzylpenicillin, which was set at 100.

Standard deviations are for triplicate determinations.

ND, not detectable; rates were too slow.

Because TLA-1 is a plasmid-mediated ESBL, it will be important to see if this gene is found in other members of the family Enterobacteriaceae. Further molecular epidemiology studies will be necessary to determine the dispersion of the blaTLA-1 gene in other multidrug-resistant clinical isolates.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are in debt to P. Bradford for meticulous review of the manuscript. We thank Zita Becerra and Teresa Rojas for technical assistance.

This study was supported in part by Federal Resources from Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología (CONACYT; grants 1892N-P and 212270-5-1915PM9507) and Instituto Nacional de Salud Pública.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ambler R P. The structure of β-lactamases. Philos Trans R Soc London Ser B. 1980;289:321–331. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1980.0049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ambler R P, Coulson A F W, Frère J, Ghuysen L, Joris B, Forsman M, Levesque R C, Tiraby G, Waley S G. A standard numbering scheme for class A β-lactamases. Biochem J. 1991;276:269–270. doi: 10.1042/bj2760269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bartélémy M, Péduzzi J, Bernard H, Tancrède C, Labia R. Close amino acid sequence relationship between the new plasmid-mediated extended-spectrum β-lactamase MEN-1 and chromosomally encoded enzymes of Klebsiella oxytoca. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1992;1122:15–22. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(92)90121-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bauernfeind A, Casellas J M, Goldberg M, Holley M, Jungwirth R, Mangold P, Röhnisch T, Schweighart S, Wilhelm R. A new plasmidic cefotaximase from patients infected with Salmonella typhimurium. Infection. 1992;20:158–163. doi: 10.1007/BF01704610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bauernfeind A, Grimm H, Schweighart S. A new plasmidic cefotaximase in a clinical isolate of Escherichia coli. Infection. 1990;18:294–298. doi: 10.1007/BF01647010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bauernfeind A, Stemplinger I, Jungwirth R, Ernst S, Casellas J M. Sequences of β-lactamase genes encoding CTX-M-1 (MEN-1) and CTX-M-2 and relationship of their amino acid sequences with those of other β-lactamases. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:509–513. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.2.509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bauernfeind A, Stemplinger I, Jungwirth R, Mangold P, Amann S, Akalin E, Ang O, Bal C, Casellas J M. Characterization of β-lactamase gene blaPER-2, which encodes an extended-spectrum class A β-lactamase. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:616–620. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.3.616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bjellqvist B, Basse B, Olsen E, Celis J E. Reference points for comparisons of two-dimensional maps of proteins from different human cell types defined in a pH scale where isoelectric points correlate with polypeptide compositions. Electrophoresis. 1994;15:529–539. doi: 10.1002/elps.1150150171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bjellqvist B, Hughes G J, Pasquali C, Paquet N, Ravier F, Sánchez J C, Frutiger S, Hoschstrasser D. The focusing position of polypeptides in immobilization pH gradients can be predicted from their amino acid sequences. Electrophoresis. 1993;14:1023–1031. doi: 10.1002/elps.11501401163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bradford P A, Yang Y, Sahm D, Grope I, Gardovska D, Storch G. CTX-M-5, a novel cefotaxime-hydrolyzing β-lactamase from an outbreak of Salmonella typhimurium in Latvia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:1980–1984. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.8.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cleland W W. Statistical analysis of enzyme kinetic data. Methods Enzymol. 1979;63:103–138. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(79)63008-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dalby R E. Leader peptidase. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:2855–2860. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb01844.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gazouli M, Legakis N J, Tzouvelekis L S. Effect of substitution of Asn for Arg-276 in the cefotaxime-hydrolyzing class A β-lactamase CTX-M-4. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1998;169:289–293. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1998.tb13331.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gazouli M, Tzelepi E, Sidorenko S V, Tzouvelekis L S. Sequence of the gene encoding a plasmid-mediated cefotaxime-hydrolyzing class A β-lactamase (CTX-M-4): involvement of serine 237 in cephalosporin hydrolysis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:1259–1262. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.5.1259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gniadkowski M, Schneider I, Palucha A, Jungwirth R, Mikiewicz B, Bauernfeind A. Cefotaxime-resistant Enterobacteriaceae isolates from a hospital in Warsaw, Poland: identification of a new CTX-M-3 cefotaxime-hydrolyzing β-lactamase that is closely related to the CTX-M-1/MEN-1 enzyme. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:827–832. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.4.827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Horii T, Arakawa Y, Ohta M, Ichiyama S, Wacharotayankum R, Kato N. Plasmid-mediated AmpC-type β-lactamase isolated from Klebsiella pneumoniae confers resistance to broad-spectrum β-lactams, including moxalactam. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:984–990. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.5.984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ishii Y, Ohno A, Taguchi H, Imajo S, Ishiguro M, Matsuzawa H. Cloning and sequence of the gene encoding a cefotaxime-hydrolyzing class A β-lactamase isolated from Escherichia coli. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:2269–2275. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.10.2269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jacob F, Joris B, Lepage S, Dusart J, Frère J. Role of the conserved amino acids of the ‘SDN’ loop (Ser130, Asp131, and Asn 132) in a class A β-lactamase studied by site-directed mutagenesis. Biochem J. 1990;271:399–406. doi: 10.1042/bj2710399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Joris B, Ledent P, Dideberg O, Fonze E, Lamotte-Brasser J, Kelly J A, Ghuysen J M, Frère J M. Comparison of the sequences of class A β-lactamases and of the secondary structure elements of penicillin-recognizing proteins. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1991;35:2294–2301. doi: 10.1128/aac.35.11.2294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kieser T. Factors affecting the isolation of CCC DNA from Streptomyces lividans and Escherichia coli. Plasmid. 1984;12:19–36. doi: 10.1016/0147-619x(84)90063-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Livermore D M. β-Lactamases in laboratory and clinical resistance. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1995;8:557–584. doi: 10.1128/cmr.8.4.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lowry O H, Rosebrough N J, Farr A L, Randall R J. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951;193:265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ma L, Ishii Y, Ishiguro M, Matsuzawa H, Yamaguchi K. Cloning and sequencing of the gene encoding Toho-2, a class A β-lactamase preferentially inhibited by tazobactam. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:1181–1186. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.5.1181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mabilat C, Lourencao-Vital J, Goussard S, Courvalin P. A new example of physical linkage between Tn1 and Tn21: the antibiotic multiple-resistance region of plasmid pCFF04 encoding extended-spectrum β-lactamase TEM-3. Mol Gen Genet. 1992;235:113–121. doi: 10.1007/BF00286188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matthew G, Hedges R, Smith J. Types of β-lactamases determined by plasmid in gram-negative bacteria. J Bacteriol. 1979;138:657–662. doi: 10.1128/jb.138.3.657-662.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miller J. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1992. pp. 82–85. [Google Scholar]

- 27.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility test for bacteria that grow aerobically. Approved standard M2-A6. Wayne, Pa: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nordmann P, Naas T. Sequence analysis of PER-1 extended-spectrum β-lactamase from Pseudomonas aeruginosa and comparison with class A β-lactamases. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38:104–114. doi: 10.1128/aac.38.1.104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Parker A C, Smith C J. Genetic and biochemical analysis of a novel Ambler class A β-lactamase responsible for cefoxitin resistance in Bacteroides species. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:1028–1036. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.5.1028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Piddock L J, Traynor E A. β-Lactamase expression and outer membrane protein changes in cefpirome-resistant and ceftazidime-resistant gram-negative bacteria. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1991;28:209–219. doi: 10.1093/jac/28.2.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Poirel L, Naas T, Guibert M, Chaibi E, Labia R, Nordmann P. Molecular and biochemical characterization of VEB-1, a novel class A extended-spectrum β-lactamase encoded by an Escherichia coli integron gene. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:573–581. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.3.573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rogers M B, Parker A C, Smith C J. Cloning and characterization of the endogenous cephalosporinase gene, cepA, from Bacteroides fragilis reveals a new subgroup of Ambler class A β-lactamases. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:2391–2400. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.11.2391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rossolini G M, Franceschini N, Lauretti L, Caravelli B, Riccio M L, Galleni M, Frère J M, Amicosante G. Cloning of a Chryseobacterium (Flavobacterium) meningosepticum cromosomal gene (blaACME) encoding an extended-spectrum class A β-lactamase related to the Bacteroides cephalosporinases and the VEB-1 and PER β-lactamases. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:2193–2199. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.9.2193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sanders C C, Sanders W E., Jr β-Lactam resistance in gram negative bacteria: global trends and clinical impact. Clin Infect Dis. 1992;15:824–839. doi: 10.1093/clind/15.5.824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Silva J, Aguilar C, Becerra Z, López-Antuñano F, García R. Extended-spectrum β-lactamases coded in clinical isolates of enterobacteria in Mexico. Microb Drug Resist. 1999;5:189–193. doi: 10.1089/mdr.1999.5.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Smith C J, Bennett T K, Parker A C. Molecular and genetic analysis of the Bacteroides uniformis cephalosporinase gene, cblA, encoding the species-specific β-lactamase. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38:1711–1715. doi: 10.1128/aac.38.8.1711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Spratt B G, Hedge P J, te Heesen S, Edelman A, Broome-Smith J K. Kanamycin-resistant vectors that are analogues of plasmids pUC8, pUC9, pEMBL8 and pEMBL9. Gene. 1986;41:337–342. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(86)90117-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thompson J D, Higgins D G, Gibson T J. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]