Abstract

Background

The clinical trials industry in China has enjoyed robust growth; the demand for qualified personnel to conduct clinical trials with higher quality has increased. The Clinical Research Nurse has emerged as a new workforce in China.

Aims

This study aimed to examine the current work status of Clinical Research Nurses in China and to investigate their competencies in knowledge and behavior associated with this profession.

Methods

An online survey was analyzed. The current work status of Clinical Research Nurses in China was characterized. In addition, their competencies were self-assessed across nine competency categories and the “contribution to science” domain, based on the International Association of Clinical Research Nurses Scope and Standards of Practice.

Results

A total of 638 eligible questionnaires were included in the final analysis. Of whom, 98.28% (627/638) were females. The mean age was 35 years (range: 22–64 years). Over 80% of whom were working at the largest Chinese cities and the majority (78.2%) held a Bachelor’s degree in nursing. The average time of clinical research experience was 5.67 years. Three quarters of the 638 had an annual income of <150,000 Yuan RMB. The average weekly working time was 45.46 h; clinical trial-related work accounted for 62.68% of their workload. There were some gaps between the Clinical Research Nurses’ self-assessed competencies in knowledge and behavior, with the widest gaps along the ethical principles, leadership and professional development, protocol compliance, and document management categories.

Conclusion

This is the first large-scale survey of Clinical Research Nurses in China. Our results profile this emerging workforce as a population of young, moderately trained/experienced, predominantly female nurses working in the largest Chinese cities. They performed well on most knowledge/behavior parameters; still, gaps exist. Therefore, there is a pressing need to enhance professional education and training for Clinical Research Nurses in China.

Keywords: China, clinical research nurse workload, competency, job satisfaction, self-assessment, survey

Introduction

Clinical research is an important part of medical research; it is the foundation for establishing drug efficacy and safety and it is on the critical path of addressing unmet medical needs (Scavone et al., 2019). High-quality clinical research, especially in the successful conduct of clinical trials, a type of clinical research designed to evaluate and test new interventions such as pharmaceutical medications (US FDA, 2018), requires highly specialized and standardized management, as well as systematically trained research personnel (Bevans et al., 2011).

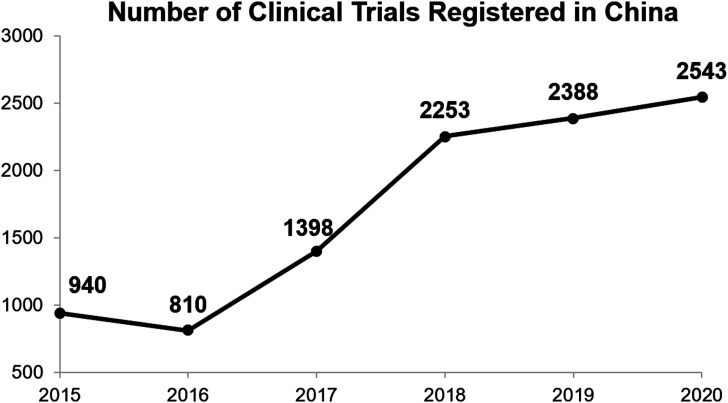

The annual number of clinical trials registered in China had mushroomed from 940 in 2015 to 2388 in 2019 (CDE, 2021; Figure 1), and continues to increase, despite the impact of the global COVID-19 pandemic starting in 2020 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Annual number of clinical trials registered in China from 2015 to 2020 (source: center for drug evaluation, national medical product administration, China; Chinadrugtrials. org.cn (2021) Total number of Registered China Drug Trials Up to Date. Available at: http://www.chinadrugtrials.org.cn/clinicaltrials.tongji.dhtml, accessed 28 Feb 2021). Each dot in the line graph and the associated number describe the number of clinical trials registered in China on any specific year (from 2015 to 2020).

In the “Announcement on Carrying out Self-inspection and Verification of Drug Clinical Trial Data” issued by the China Food and Drug Administration (CFDA, 2015; ([2015] No. 117) (Note: the CFDA later evolved to become National Medical Products Administration [NMPA], the regulatory authority of China), the CFDA initiated the most stringent data verification requirements and adherence to the principles of GCP in the modern history of the Chinese pharmaceutical industry. As a result, many sponsors, clinical research centers/hospital sites, and clinical research organizations (CROs) withdrew their new drug marketing authorization applications in fear of sub-standard data in the clinical trials that they had sponsored or partaken in leading to these applications would result in severe punishment upon unfavorable inspection outcome by the Center for Food and Drug Inspection (CFDI), a division of the CFDA. The impact of this event is so far-reaching, that it is widely known in the Chinese pharmaceutical industry as the “722 incident” as the announcement came out on July 22 (of 2015). In fact, as can be seen in Figure 1, the annual number of clinical trials registered in China declined from 940 in 2015 to 810 in 2016, the only year-to-year decline of this number ever, vividly showing the negative immediate impact of the “722 incident” on the clinical trials industry in China. However, after 2016, the number quickly rebounded and increased at a high slope, reflecting the favorable long-term impact of the “722 incident” as it created a higher quality standard for clinical trials conduct in China, which was well received by the industry, after the initial negative short-term influence in 2015/2016 (Figure 1).

With an increasing number of clinical trials and trial participants, rigorous requirements on clinical trial application and conduct, sophisticated scientific questions to be answered, and the use of high-tech electronic data collection instruments, the need for a highly specialized and trained research team becomes ever more indispensable (Cooke and Hilton, 2015; Eckardt et al., 2017). As a result, Clinical Research Nurses (CRNs), first appeared as a specialized member of a clinical research team in the 1910s (Rockefeller University Hospital, 2021) and usually referred to as the nursing staff engaged in clinical research, have emerged as a new workforce in China. In addition to providing nursing care, CRNs also serve as a member of the clinical research team through coordination and implementation of clinical trial procedures in human subjects (i.e., clinical research participants), while focused on maintaining the balance between participant protection and study protocol compliance (Hastings et al., 2012; IACRN, 2012; McCabe et al., 2019). Roles of CRNs are different from those of general nurses: CRNs are involved in clinical research-related activities and they focus on providing care to clinical research participants, whereas general nurses provide direct nursing care to all patients.

Although the CRN profession has been long established in western countries, it is relatively new in China, with its beginning dates to approximately 15 years ago, when Good Clinical Practice (GCP) standard first started to be widely implemented in clinical trials in China. Currently no national standards have been established for the scope of professional practice for CRNs in China. Therefore, many practicing nurses, hospital administrators, and clinical trials industry stakeholders remain unfamiliar with this emerging profession. To make things more complicated, the China healthcare system relevant to nursing practices has many characteristics that are unique to China.

In China, the human resources reporting relationship of CRNs in hospitals could be one of three: the nursing department, the clinical department, or the clinical trial office. In a typical Chinese hospital, from a human resources perspective, most nurses report to the hospital nursing department. Even though the nurse’s daily work is conducted at the various clinical specialty departments, such as cardiovascular, oncology, pulmonary diseases, and pediatrics, her/his reporting line is officially to the hospital nursing department (HND). In the present study, these nurses are categorized under the “hospital nursing department” or “HND.” In contrast, in some hospitals, there are some nurses who report directly to the medical doctors/physicians/medical staff administrators, these nurses are categorized under the “hospital clinical department” or “HCD.” Finally, in Chinese hospitals that conduct clinical trials, there are hospital clinical trial offices (HCTOs) that are responsible for the administration of these clinical trials. In some large hospitals with many clinical trial activities, CRNs report to the staff administrators at the HCTOs; we categorize these nurses under “hospital clinical trial office” or “HCTO.”

CRNs included in this study came from two main types of employment entity: site management organization (SMO, an organization that provides clinical trial related services to clinical sites) and hospital (which is further divided into three sub-entities, see Introduction above). Strictly speaking, SMO can offer only clinical research coordinators (CRCs) in China. However, the majority of these CRCs from SMOs have nursing background. Due to China’s current healthcare regulations, these CRCs cannot perform direct patient care, because the license of a Chinese nurse must be associated with an eligible employment entity, typically a hospital (but not a SMO). Therefore, this is different from that in many western countries (e.g., USA), where registered nurses could practice nursing as independent nurse practitioners. In effect, these CRCs from SMOs with a nursing educational background can do everything a hospital CRN could do, except for providing direct care of study participants (because they do not have effective nursing licenses). We believe that CRCs from SMOs represent one area with significant growth potential, as they could easily be converted to CRNs in the future if their employment is changed from SMOs to hospitals, or should policy governing nursing practices in China change. Therefore, we had intentionally included CRCs from SMOs in this survey and classify them under the “SMO” category and hereafter are referred to as CRNs as well.

Furthermore, the Chinese city tier system is also unique. Chinese cities are unofficially categorized into several tiers. Traditionally, Tier 1 cities are the largest and most affluent—often considered the megapolises of China. It is commonly believed that there are 4 such Tier 1 cities: Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, and Shenzhen. Cities referred to as “Tier 1.5” or “emerging first-tier” cities represent those that do not equal the traditional first-tier cities, but nevertheless stand out beyond other traditional Tier 2 cities. As the tiers progress, the cities decrease in size, affluence, and move further away from prime locations. Yicai Global, a Chinese news source, categorizes Chinese cities into six tiers using the five measures below: concentration of commercial resources; city’s pivotability; citizen vitality; lifestyle diversity; and flexibility in the future. The Yicai classification resulted in: 4 Tier 1 cities, 15 emerging Tier 1 cities, 30 Tier 2 cities, 70 Tier three cities, 90 Tier 4 cities and 129 Tier 5 cites (China Briefing, 2017; Wang et al., 2021).

Therefore, many questions about this growing profession remain: what do the demographics of the CRNs in China look like? Do these CRNs meet the needs of clinical trial conduct? Are standardized job qualifications, onboarding training and continuous professional education available for Chinese CRNs? Are their training materials developed and performance evaluated based on reliable evidence? Are CRNs satisfied with their own profession? Does the human resources reporting relationship influence the behavior and knowledge competencies of the CRNs?

To help answer these basic questions, we designed this study to investigate the current work status of CRNs in China by five dimensions: demographics of professional CRNs, their scope of practice, skills and training, job satisfaction, and collaboration with associated clinical research professionals. CRNs from four different types of employment entities (SMO, HND, HCD, and HCTO) were included in the study.

We hoped that by looking into the degree of current professional standardization, systematization, recognition and collaboration we could begin to explore the issues that existed in the current CRN practice and to support the advancement of the CRN profession in China. Meanwhile, this study could serve as a baseline and provide benchmarks in formulating industry norms for the CRN profession in China while improving industry standards for this profession in China in the future.

Methods

We designed a survey questionnaire based on the nine categories of competency requirements of the Oncology Clinical Trials Nurse (OCTN) Competencies model described by Oncology Nursing Society (ONS, 2016; authorization was obtained from ONS regarding the translation of contents into Chinese and the use for research purposes) as well as the competency requirements that relate to the “contribution to science” domain described by IACRN (American Nurses Association, 2016; Castro et al., 2011).

The questionnaire has three parts with a total of 43 questions (Table 1). Part 1 of the questionnaire covered the following five dimensions of CRN work status: demographics, scope of practice, skills and training, job satisfaction, and collaboration with associated clinical research professionals. Respondents were asked to provide information on their demographic and educational background, as well as experience and level of satisfaction in the profession of clinical research nursing.

Table 1.

Content of CRN questionnaire.

| Background information and professional experience | Gender (Q3), age (Q4), academic major and degree (Q5, Q6), city of employment (Q1), hospital grade and department of employment (Q2, Q7), years of experience as CRN (Q8), number of nurses and CRNs in hospital of employment (Q9, Q10), GCP training certificate (Q11), experience and level of personal interest in clinical trial trainings (Q12, Q13, Q14), weekly workload (Q15, Q16), previous and current participation in clinical trials (Q17, Q18), collaboration with CRC/CRA/investigators (Q19, Q20), current and desired annual income (Q21, Q22), and job satisfaction (Q23) | Q1–Q23 | |

| Competency self-assessment | Module 1 | Adherence to ethical standards | Q24–Q25 |

| Module 2 | Protocol compliance | Q26–Q27 | |

| Module 3 | Informed consent | Q28–Q29 | |

| Module 4 | Participant recruitment and retention | Q30–Q31 | |

| Module 5 | Management of clinical trial patients | Q32–Q33 | |

| Module 6 | Documentation and document management | Q34–Q35 | |

| Module 7 | Data management and information technology | Q36–Q37 | |

| Module 8 | Financial stewardship | Q38–Q39 | |

| Module 9 | Leadership and professional development | Q40–Q41 | |

| Module 10 | Contributing to the science (competency assessment of behavior only) | Q42 | |

| Open question | — | Why did you choose to be a CRN? | Q43 |

In Part 2 of the questionnaire, a total of 89 statement items were listed for self-assessment of competencies. Respondents were asked to assign a score to each of the statement items on a scale of 0–5, where 0 represented “no knowledge” or “never performed in practice,” and 5 represented “total comprehension” or “always performed in practice.” The first 9 modules were designed based on the ONS 2016 OCTN Competencies model. The 10th module of the competencies section of the questionnaire (i.e., contribution to science) was based on what was described in IACRN Clinical Research Nursing: Scope and Standards of Practice (American Nurses Association, 2016), Standard 13 “Evidence-Based Practice and Research: The clinical research registered nurse integrates evidence and research finding into practice.” We had chosen the top three criteria that we deemed most appropriate for the Chinese CRN population for assessing the competencies of contribution to science.

In Part 3 of the questionnaire, respondents were asked to provide answers to an open-ended question regarding why they had chosen CRN as a profession. Here, we intended to find out the motivations that drove the CRNs to this profession.

The original survey questionnaire used for the present study is in the Chinese language. The translated English version of the questionnaire is provided in supplementary material.

Based on the questionnaire, a web-based anonymous survey was conducted in individuals who attended or watched an online streaming of a 2-day clinical research nursing forum organized by the Fudan University Shanghai Cancer Center in June 2019. Before the forum, potential participants were required to scan a Quick Response (QR) code of the questionnaire and fill in the survey questionnaire online. A total of 387 potential participants responded to the survey before they were registered and granted access to attend the forum offline or watch its real-time online streaming. After the forum, a full recording of the forum was uploaded online, with the QR code presented along with the link to the recording. Respondents who scanned the QR code and filled in the questionnaire would be granted access to the recording. Another 432 viewers responded.

Results

A total of 819 potential CRNs responded to our survey. The returned surveys were screened according to the responders’ educational background and the nature of their daily work. To be eligible for inclusion in the final analysis of the present study, respondents must hold a diploma of secondary specialized school in nursing or higher and must be dedicating >50% of their work time to clinical trial-related activities. Of the 819 respondents, 638 (77.9%) met our definition/criteria for CRN, set a priori.

In terms of the type of their employment entity (i.e., human resources reporting relationship), the 638 CRNs came from 4 different types of entities: SMO (n = 84, 13.17%), HND (n = 265, 41.54%), HCD (n = 120, 18.81%), and HCTO (n = 169, 26.49%).

Demographics, background information and professional experience

Of the 638 CRNs included in the final analysis, 627 (98.28%) were females and only 11 (1.72%) were males. The mean age was 35 years (range: 22–64 years).

These 638 CRNs were working at 58 cities across China, most commonly in first-tier cities (49.37%) or emerging first-tier cities (30.41%) by definition of city tiers in China (Wang et al., 2021) (Table 2). In other words, these CRNs were mostly working in the largest Chinese cities with the highest socio-economic development level and future potential. The geographic distribution pattern of CRNs was different by the type of employment entity. CRNs from SMOs had the highest proportion (96.43%, 81/84) working at first-tier and emerging first-tier cities.

Table 2.

Number (%) of China CRNs by city tiers and by type of employment entity.

| Employment entity city tier | SMO (n = 84) | HND (n = 265) | HCD (n = 120) | HCTO (n = 169) | Overall (N = 638) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First-tier cities | 46 (54.76) | 143 (53.96) | 58 (48.33) | 68 (40.24) | 315 (49.37) |

| Emerging first-tier cities | 35 (41.67) | 72 (27.17) | 27 (22.5) | 60 (35.50) | 194 (30.41) |

| Second- and lower-tiers cities | 3 (3.57) | 50 (18.87) | 35 (29.17) | 41 (24.26) | 129 (20.22) |

The majority of CRNs in this study, 499 (78.21%), held a Bachelor’s degree in nursing, while 88 (13.79%) held an Associate Degree in nursing, and 44 (6.90%) had a Master’s degree or above. A higher proportion of CRNs working at HCTOs had academic qualifications of Bachelor’s degree or above, compared with those from the other three types of employment entity (Table 3).

Table 3.

Number (%) of China CRNs by educational background and by type of employment entity.

| Employment entity educational background | SMO (n = 84) | HND (n = 265) | HCD (n = 120) | HCTO (n = 169) | Overall (N = 638) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Master’s degree or above | 0 (0.00) | 18 (6.79) | 9 (7.50) | 17 (10.06) | 44 (6.90) |

| Bachelor’s degree | 65 (77.38) | 204 (76.98) | 95 (79.17) | 135 (79.88) | 499 (78.21) |

| Associate degree | 18 (21.43) | 40 (15.09) | 15 (12.50) | 15 (8.88) | 88 (13.79) |

| Other a | 1 (1.19) | 3 (1.13) | 1 (0.83) | 2 (1.18) | 7 (1.1) |

aOther included CRNs who held an associate degree in nursing but were pursuing a bachelor’s degree at the time of the survey, or those with a diploma of secondary specialized school in nursing.

The average time of research experience for the 638 CRNs was 5.67 years; however, two thirds of CRNs had clinical research experience of less than 6 years: <1 year (n = 139, 21.79%), 1–3 years (n = 132, 20.69%), 3–6 years (n = 147, 23.04%), 6–11 years (n = 126, 19.75%), 11–20 years (n = 73, 11.44%), and 20 years or more (n = 21, 3.29%). The average time of research experience was 3.24 years for SMO CRNs, 5.43 years for HND CRNs, 7.48 years for HCD CRNs, and 5.97 years for HCTO CRNs (Table 4).

Table 4.

Number (%) of China CRNs by years of research experience and by type of employment entity.

| Employment entity research experience | SMO (n = 84) | HND (n = 265) | HCD (n = 120) | HCTO (n = 169) | Overall (N = 638) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <1 year | 29 (34.52) | 67 (25.28) | 18 (15.00) | 25 (14.79) | 139 (21.79) |

| 1∼ <3 years | 18 (21.43) | 47 (17.74) | 14 (11.67) | 53 (31.36) | 132 (20.69) |

| 3∼ <6 years | 25 (29.76) | 63 (23.77) | 27 (22.50) | 32 (18.93) | 147 (23.04) |

| 6∼ <11 years | 11 (13.10) | 55 (20.75) | 34 (28.33) | 26 (15.38) | 126 (19.75) |

| 11∼ <20 years | 1 (1.19) | 22 (8.30) | 20 (16.67) | 30 (17.75) | 73 (11.44) |

| ≥20 years | 0 (0.00) | 11 (4.15) | 7 (5.83) | 3 (1.78) | 21 (3.29) |

| Average (year) | 3.24 | 5.43 | 7.48 | 5.97 | 5.67 |

Three quarters of the 638 CRNs had an annual income of ≤150,000 Yuan RMB (approximately US$23,000): 274 (42.95%) had an annual income of 100,000 to 150,000 RMB and 211 (33.07%) of <100,000 RMB. The desired annual income after 3 years fell mostly into the 150,000 to 200,000 RMB (n = 242, 37.93%) and 200,000 to 300,000 RMB (n = 210, 32.92%) categories. The distribution pattern of current and desired annual income was slightly different among CRNs working at different employing entities (Table 5).

Table 5.

Number (%) of China CRNs by current annual income/desired annual income after 3 years and by type of employment entity.

| Employment entity current annual income | SMO (n = 84) | HND (n = 265) | HCD (n = 120) | HCTO (n = 169) | Overall (N = 638) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <100,000 RMB | 48 (57.14) | 66 (24.91) | 37 (30.83) | 60 (35.50) | 211 (33.07) |

| 100,000–150,000 RMB | 28 (33.33) | 127 (47.92) | 49 (40.83) | 70 (41.42) | 274 (42.95) |

| 151,000–200,000 RMB | 6 (7.14) | 54 (20.38) | 25 (20.83) | 26 (15.38) | 111 (17.40) |

| 201,000–300,000 RMB | 2 (2.38) | 18 (6.79) | 9 (7.50) | 10 (5.92) | 39 (6.11) |

| 301,000–400,000 RMB | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 3 (1.78) | 3 (0.47) |

The 638 CRNs were working an average of 45.46 hours per week (Table 6). Clinical trial-related activities accounted for 62.68% of their weekly workload. Clinical trial-related work accounted for 51.98%–79.96% of the CRNs’ total workload, while workload that was unrelated to clinical research was 37.32% of total work hours per week. There were no obvious differences in weekly workload among CRNs from different types of employment entity. The average proportion of weekly workload unrelated to clinical research was higher for HND CRNs than for those working at other types of employment entity.

Table 6.

Average working hours per week and distribution of workload of China CRNs by type of employment entity.

| Employment entity working hours | SMO (n = 84) | HND (n = 265) | HCD (n = 120) | HCTO (n = 169) | Overall (N = 638) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average working hours per week (hour) | 46.68 | 44.38 | 46.20 | 46.04 | 45.46 |

| Distribution of workload type of workload | |||||

| Non-clinical trial related clinical work | 9.60% | 32.48% | 27.53% | 13.12% | 23.41% |

| Non-clinical trial related non-clinical work | 10.44% | 15.53% | 14.68% | 12.53% | 13.91% |

| Clinical trial related clinical operation work | 27.92% | 20.70% | 25.08% | 28.68% | 24.59% |

| Clinical trial related data entry and paperwork | 29.56% | 14.83% | 15.27% | 20.14% | 18.26% |

| Clinical trial related communication work | 22.49% | 16.45% | 17.44% | 25.54% | 19.84% |

A total of 59.56% (380/638) of CRNs in China had participated in international multicenter trials, and 65.67% had participated in oncology trials. The pattern of experience with various clinical trial types varied across the types of employment entity. For example, the highest proportion of CRNs from SMO had experience in international multi-center trials (80.95%) compared with those from hospital departments/offices (52.08%, 67.50%, and 55.03% from HND, HCD, and HCTO, respectively; Table 7).

Table 7.

Number (%) of China CRNs with clinical trial experience by clinical trial type and type of employment entity.

| Employment entity clinical trial type | SMO (n = 84) | HND (n = 265) | HCD (n = 120) | HCTO (n = 169) | Overall (N = 638) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global multi-center clinical trials | 68 (80.95) | 138 (52.08) | 81 (67.50) | 93 (55.03) | 380 (59.56) |

| Local multi-center clinical trials | 76 (90.48) | 201 (75.85) | 96 (80.00) | 133 (78.70) | 506 (79.31) |

| Oncology clinical trials | 62 (73.81) | 159 (60.00) | 90 (75.00) | 108 (63.91) | 419 (65.67) |

| Non-oncology clinical trials | 77 (91.67) | 143 (53.96) | 64 (53.33) | 129 (76.33) | 413 (64.73) |

The average number of clinical trials that each CRN had participated in was 9.62 (Table 8). On average, these CRNs had participated in 4.10 international multicenter trials, and 5.12 oncology trials. When classified by employment entity type, CRNs from HCTOs had participated in more clinical trials (12.83 on average) than those from the other three entities (8.11, 7.76, and 10.25 for CRNs at SMO, HND, and HCD, respectively). However, CRNs from HCDs were most experienced in oncology studies (7.23 on average) compared with those from the other three entities (3.03, 4.33, and 5.90 for SMO, HND, and HCTO, respectively; Table 8).

Table 8.

Average number of clinical trial participations of China CRNs by clinical trial type and type of employment entity.

| Employment entity clinical trial type | SMO (n = 84) | HND (n = 265) | HCD (n = 120) | HCTO (n = 169) | Overall (N = 638) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experience prior to survey | |||||

| Any clinical trials | 8.11 | 7.76 | 10.25 | 12.83 | 9.62 |

| Global multi-center clinical trials | 3.74 | 3.20 | 4.77 | 5.20 | 4.10 |

| Local multi-center clinical trials | 4.97 | 4.77 | 6.49 | 7.41 | 5.82 |

| Oncology clinical trials | 3.03 | 4.33 | 7.23 | 5.90 | 5.12 |

| Non-oncology clinical trials | 5.10 | 3.34 | 3.69 | 8.63 | 5.04 |

| Still ongoing at time of survey | 3.90 | 5.17 | 6.98 | 7.04 | 5.84 |

At the time of the survey, the average number of ongoing clinical trials/CRN was 5.84. Those from SMOs were involved in the least number of trials (3.90 on average), while those working at HCTOs were participating in the greatest number of ongoing trials (7.04 on average) (Table 8).

Most of the CRNs (≥77.50%) from all 4 employment entities had obtained their GCP training certification within the last 5 years (Table 9).

Table 9.

Number (%) of China CRNs since last time obtaining GCP training certificate by type of employment entity.

| Employment entity time of last GCP training certificate | SMO (n = 84) | HND (n = 265) | HCD (n = 120) | HCTO (n = 169) | Overall (N = 638) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Certification obtained ≤5 years ago | 77 (91.67) | 206 (77.74) | 93 (77.50) | 156 (92.31) | 532 (83.39) |

| Certification obtained >5 years ago | 7 (8.33) | 23 (8.68) | 13 (10.83) | 11 (6.51) | 54 (8.46) |

| Certification never obtained or no answer to this question | 0 (0.00) | 36 (13.58) | 14 (11.67) | 2 (1.18) | 52 (8.15) |

Higher proportions of CRNs from HCTOs had received frequent trainings (≥4 times during Years, 2016–2018, both voluntary and mandatory trainings) compared with those working at other employing entities (Table 10). In contrast, CRNs from SMO showed higher willingness to be trained, as the proportion of SMO CRNs who frequently participated in voluntary training (≥4 trainings during 2016–2018) was higher (64.28%) compared with CRNs from other employing entities (≤60.95%).

Table 10.

Number (%) of China CRNs who received trainings within 3 years (2016–2018) by frequency of mandatory/voluntary trainings and by type of employment entity.

| Employment entity Frequency of training |

SMO (n = 84) | HND (n = 265) | HCD (n = 120) | HCTO (n = 169) | Overall (N = 638) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of mandatory training | |||||

| ≤3 times | 48 (57.14) | 146 (55.09) | 53 (44.17) | 63 (37.28) | 310 (48.59) |

| 4–10 times | 29 (34.52) | 101 (38.11) | 46 (38.33) | 72 (42.60) | 248 (38.87) |

| >10 times | 7 (8.33) | 18 (6.79) | 21 (17.50) | 34 (20.12) | 80 (12.54) |

| Number of voluntary training | |||||

| ≤3 times | 30 (35.71) | 169 (63.77) | 54 (45.00) | 66 (39.05) | 319 (50.00) |

| 4–10 times | 30 (35.71) | 79 (29.81) | 43 (35.83) | 65 (38.46) | 217 (34.01) |

| >10 times | 24 (28.57) | 17 (6.42) | 23 (19.17) | 38 (22.49) | 102 (15.99) |

For their satisfaction when working with the key collaborators in clinical research: investigators, CRCs, and clinical research associates (CRAs), CRNs had the highest level of satisfaction with investigators (7.83), followed by with CRCs (7.61) and with CRAs (7.27). The satisfaction level working with collaborators varied by the type of employment entity, although the variance was mild (Table 11).

Table 11.

Degree of satisfaction of China CRNs with key research collaborators (on a scale of 0–10).

| Employment entity types of research collaborators | SMO (n = 84) | HND (n = 265) | HCD (n = 120) | HCTO (n = 169) | Overall (N = 638) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical research coordinator | 7.74 | 7.68 | 7.49 | 7.51 | 7.61 |

| Clinical research associate | 7.04 | 7.53 | 7.03 | 7.14 | 7.27 |

| Investigator | 7.61 | 7.93 | 7.79 | 7.80 | 7.83 |

Overall, CRNs in China had the highest level of satisfaction in the sense of accomplishment at work (7.34); they were least satisfied with their job income (6.15). CRNs’ satisfaction score varied by their types of employment entity. For example, for the sense of belonging parameter, CRNs of HCTO had the highest score on average, and those from SMO had the lowest score (Table 12).

Table 12.

Degree of satisfaction of China CRNs with various aspects of their job (on a scale of 0–10).

| Employment entity job satisfaction | SMO (n = 84) | HND (n = 265) | HCD (n = 120) | HCTO (n = 169) | Overall (N = 638) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sense of belonging | 6.89 | 7.13 | 7.03 | 7.21 | 7.10 |

| Sense of accomplishment | 7.27 | 7.21 | 7.33 | 7.57 | 7.34 |

| Room for career advancement | 6.55 | 6.41 | 6.18 | 6.38 | 6.38 |

| Income | 5.69 | 6.24 | 6.26 | 6.15 | 6.15 |

Self-assessed competencies

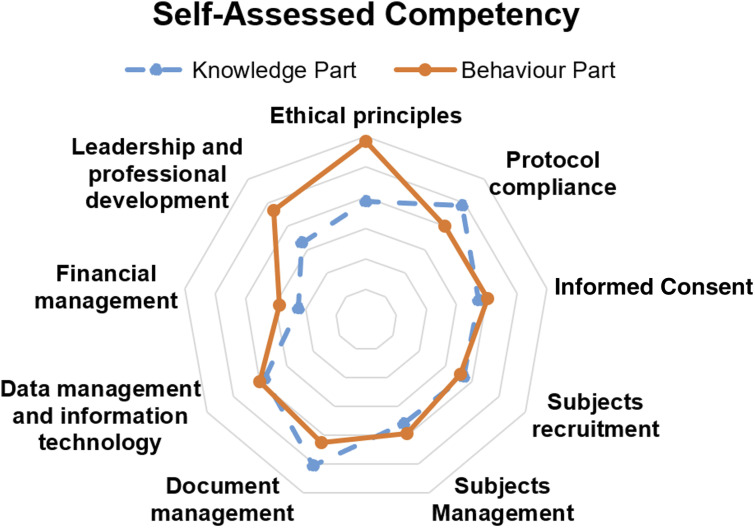

Based on the ONS 2016 competencies model, of the 638 CRNs included in this analysis, the mean score of self-assessed competency in knowledge was 68.99 on a 100-point scale, and the mean score of self-assessed competency in behavior was 70.67. CRNs assigned lower scores to knowledge than to behavior in modules of adherence to ethical standards, leadership and professional development, and financial stewardship. However, they assigned higher scores in knowledge than in behavior in modules of protocol compliance and documentation and document management (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Radar plot illustrating self-assessed knowledge and behavior competencies by CRNs (N = 638) in China based on a survey conducted in 2019. The survey questionnaire was based on the Oncology Nursing Society (2016) Oncology Clinical Trials Nurse Competencies Model (blue dotted line/dots represent self-assessed knowledge competency scores and orange solid line/dots represent self-assessed behavior competency scores. Nine categories from the ONS model were assessed: ethical principles, protocol compliance, informed consent, subjects recruitment, subjects management, document management, data management and information technology, financial management, and leadership and professional development).

As shown in Table 13, knowledge-behavior gaps existed in Chinese CRNs. In a few modules of the competency self-assessment, CRNs assigned higher scores to their competency levels in behavior than to those in knowledge. While the high scores of behavior observed in the module of ethical principles showed that CRNs were generally confident in adhering to ethical principles during clinical practice, lower scores of knowledge indicated that they considered themselves lacking of knowledge in terms of understanding the rational of these principles. For example, the average score of all the respondents' knowledge of “Belmont Report, etc.” was only 2.52 points (out of 5 points), and the average score of knowledge of “conflict of interest regulatory system and policy” was only 3.33 points (out of 5 points). Similar gaps were also observed in modules of leadership and professional development as well as financial management, which reflects a general lack of these contents in CRNs’ training in China.

Table 13.

Gaps between self-assessed competencies in knowledge and behavior among China CRNs.

| Employment entity competency | SMO (n = 84) | HND (n = 265) | HCD (n = 120) | HCTO (n = 169) | Overall (N = 638) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adherence to ethical standards | 15.19 | 7.12 | 8.23 | 12.52 | 9.82 |

| Leadership and professional development | 5.63 | 6.72 | 7.72 | 7.46 | 6.96 |

| Financial stewardship | 15.06 | −0.35 | 0.09 | 5.18 | 3.22 |

| Management of clinical trial patients | 6.22 | 0.12 | 0.99 | 2.44 | 1.71 |

| Informed consent | 5.10 | 0.09 | 3.41 | 0.80 | 1.57 |

| Data management and information technology | 2.71 | 0.54 | 1.51 | 0.54 | 1.01 |

| Participant recruitment and retention | 10.32 | −3.74 | −0.81 | −1.30 | −0.69 |

| Documentation and document management | −0.48 | −5.34 | −3.60 | −4.41 | −4.12 |

| Protocol compliance | −6.46 | −5.36 | −1.21 | −3.89 | −4.33 |

Note: each score = behavior score - knowledge score. Therefore, a positive number denotes that the CRN’s competency in behavior is greater than her/his competency in knowledge and vice versa.

On the other hand, gaps where confidence in behavior was lower than in knowledge were also observed. CRN-reported scores for the protocol compliance module showed lower confidence in behavior than in knowledge regarding their compliance to clinical study protocols, which may be due to that CRNs, compared with other members of clinical study team, had lower levels of involvement in “identifying the primary and secondary objectives and endpoints,” “contribute to discussion regarding feasibility of protocol implementation and give suggestions,” and “assist in developing protocol-specific process in the site.” Similarly, CRNs were less confident in behavior than in knowledge in terms of clinical research documentation and document management. For example, an average score of 3.58 points (out of 5 points) was reported by the CRNs regarding their competency in the behavior of “obtain and document all legal medical records and laboratory data for all participants as required,” while their knowledge of “institution’s electronic medical records” and “national and local requirements for medical record retention” scored 3.94 and 3.73 points, respectively. Regarding competency in the behavior of “educate other study team members and clinical staff regarding appropriate and accurate source documentation for participants,” an average score of 3.47 points (out of 5 points) was reported, while CRN respondents reported an average score of 3.65 points for their knowledge of “definitions of source documents and essential documents,” which may be because CRAs were usually responsible for this behavior.

For the contribution to science domain of the survey questionnaire, the authors selected three top competency standards from the IACRN′s Scope and Standards of Practice (American Nurses Association, 2016), Standards of Professional Performance for Clinical Research Nursing to assess CRNs’ awareness of science contribution in their behavior. There was no assessment on knowledge in this category. Overall, their self-assessed competencies in behavior of contribution to science were similar among the CRNs from the four types of employment entity, 61.43, 57.28, 62.61, 64.85, for CRNs from SMO, HND, HCD, and HCTO, respectively.

Motivation for choosing to be a CRN

The reasons that the CRNs chose to be in this profession varied widely. The answers to this free-text open question ranged from very haphazard ones such as “when I graduated from college, I did not know anything better and I just bumped into this profession,” “my supervisor assigned me to this job and I have to do it,” and “to make more money” to very methodological ones such as “to contribute to clinical research to improve the standard of healthcare by promoting the application of good innovative drugs and by preventing the harm to humans from bad drugs,” “I am hoping that by our dedicated work, to objectively characterize the efficacy and safety profiles of the drug, to help cancer patients live longer,” and “clinical nurses should not be limited to ordinary nursing practices, they should improve themselves by continuously learning to fully develop their potential, and maximize their contributions to society in general and patient care in particular”.

The most common reasons (≥10 respondents) for CRNs in China choosing CRN as their profession were: interest in clinical research/clinical trials (n = 131), expand on current responsibilities (n = 77), feels that this profession has great value and wish to make greater contributions to clinical research/new drug development/society (n = 57), would like to learn more about clinical research/new drug development/gain new knowledge (n = 54), there is no night shift/less pressure than practicing clinical nursing (n = 27), and feel that this profession has a bright future and followed the industry trend (n = 11).

Discussion

With a surge of the number of clinical trials conducted in China, more attention has been given to the roles and contributions of Chinese CRNs in providing safe and ethical protection for clinical trial participants while conducting high-quality clinical research activities in a protocol-compliant manner. Therefore, it is of vital importance to define the professional responsibilities and competencies of CRNs. As the first large-scale study in China to investigate the current work status and competencies of Chinese CRNs, this study may provide insight into and guidance for further advancement of this profession in China.

Our results showed that Chinese CRNs’ level of satisfaction was the highest when they collaborated with investigators, and lowest with CRAs. Also, variability was observed in CRNs from different types of employment entity regarding their overall level of job satisfaction on dimensions of sense of belonging, sense of accomplishment, room for career advancement, and income. CRNs from SMOs reported relatively lower scores regarding satisfaction levels of sense of belonging, sense of accomplishment and income; however, they were more confident in their future career prospect than CRNs employed by various hospital entities. Considering that the Chinese SMO industry started to emerge in 2008, requirements and rewards may be lower for CRNs from SMOs as they mostly provide study coordination services to clinical research sites and do not conduct direct patient care. However, it is reasonable to believe the growing clinical trials industry in China will lead to an increased demand for SMO services. On the other hand, HCTO CRNs had the highest level of satisfaction on parameters of senses of belonging and accomplishment.

Not surprisingly, the majority of the CRNs in our study were females. However, compared with the CRN workforce in the United States, where 80.8% of CRNs were females in 2020 (zippia.com, 2021), nearly 98.3% (627/638) of the CRNs in our study were females. We believe this reflects the different background gender makeup of the general nurse workforces in China and in the US. In China, only 2% of its nurse workforce were males in 2020 (baijiahao.com, 2020), compared with more than 9% of male nurses in the US in 2020 (Carson-Newman, 2021). Of note, in the 1970s, male nurses made up only 2% of the US nursing workforce. This supports our original hypothesis that the development state of the general nurse workforce and the emerging CRN workforce in China in certain aspects might mirror what was like in the US in the 1970s, when the CRN profession was still in its earlier stage of development there.

With a mean age of 35 years (range: 22–64 years), the China CRNs in our study were noticeably younger than those in the US (mean age: 44 years, zippia.com, 2021). On average, the China CRNs seemed to have a stronger educational background in nursing (78.2% in China versus 49% in the US with a Bachelor’s degree). However, a large proportion of China CRNs were relatively inexperienced: 22% had <1 year and 21% had 1 to <3 years of research experience. In comparison, many CRN jobs in the US require a minimum of 2 years of prior research experience, and often 4 years or more for oncology-related CRN positions (City of Hope, 2021; Abramson Cancer Center Clinical Research Unit, 2021). This discrepancy in education/knowledge and behavior might explain the relative wide gaps of China CRNs in the ethical principles, leadership and professional development, protocol compliance, and document management categories on the ONS 2016 competences model. Note, considering that only 14.5% of nurses in China completed undergraduate training in the year of 2016, the CRNs in China overall had a relatively higher level of education (National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China. 2017).

Like in the US, where most CRNs worked in large cities such as New York and Baltimore (zippia.com, 2021), over 80% of China CRNs in this study were working at the largest Chinese cities according to our survey. These results reflect the fact that clinical trials in China are mostly conducted in major cities where most top-grade hospitals are located. China has allowed more clinical trial centers to be established in second or third-tier cities to meet rising drug development needs; therefore, we expect the distribution of employment locations will further expand in the coming years. In addition, geographic distribution of CRNs in China was slightly different by type of employment entity. SMO had the highest proportion (96.43%, 81/84) of CRNs working at first-tier and emerging first-tier cities, because nearly all SMOs are based in top-tier Chinese cities.

Given the uniqueness of the organizational structure of nurses in Chinese hospitals, in designing the present study, we were interested in finding out if the human resources reporting relationship would influence the behavior and competencies of the CRNs. Our hypothesis was that it would, because the nurses with different HR reporting lines would be evaluated by different qualities by their line managers. And line managers working at the nursing department (mostly administrators with nursing background), clinical department (mostly physicians), and clinical trial office (mostly administrators with pharmacy or medical background with a heavy focus on clinical trials) have different priorities. Our study results seem to support our hypothesis. For example, we find that CRNs from the HCTOs obtained the highest scores on the self-assessed competencies scale, those CRNs from HCDs performed second best, and those from HNDs least. Thus, to advance the CRN occupation as a specialized nursing practice, nursing administrators/hospital management/national regulators should increase their awareness and recognition for the expertise, special requirements and needs for the CRN profession. We further observed that among CRNs from the 4 employment entities, greater proportions of HCTO CRNs had higher levels of education, received more GCP and clinical trial-related trainings, were more experienced in clinical research as shown by years of participation and numbers of clinical trials participated in, and they scored higher in self-assessed competencies. The reason could be that the specific job accountability of HCTO CRNs was to coordinate a larger number of clinical trials, which required them to be better trained and familiar with relevant knowledge of clinical research nursing.

One limitation of our study was our application of the ONS 2016 OCTN Competencies model to China CRNs, without fully validating this application. In fact, as far as the authors are aware, there is no other publication examining the role and competencies of CRNs in China. As a pioneer project, this study tried to reference what had been done elsewhere in designing our survey to gain the first glimpse of the CRN workforce in China. We believe that more targeted survey studies for the unique roles of CRN in China will follow.

In addition, the ONS model was designed for CRNs specializing in oncology clinical trials, whereas in our study, CRNs in both oncology and non-oncology were included. Whether the application of the ONS model to CRNs with a heterogenous background is appropriate and if the results could have been skewed remain unknown. Finally, we believe that the patient care in a clinical trial environment is fundamentally different from regular patient care. The former follows the clinical trial protocol requirements, manages only the trial-related patient care, while regular patient care is managed by regular clinical nursing in clinical trials in China. Thus, CRNs in China provide not only patient care, but also the study coordinator’s role significantly. Therefore, despite the above-mentioned limitations, we still believe that the ONS model is reasonably suited for this first large-scale research of the CRNs in China.

The results of our study highlight several areas for potential exploration in the China CRN industry to help improve the standard of this profession. As the first such study in China, it describes the baseline characteristics of the emerging CRN workforce in China. After adaption, further refinement, and validation, this type of survey could be repeated at certain intervals (e.g., every 5 years) in the future to evaluate and record the progression of the CRN profession in China, and how the result compares to its concurrent equivalents in other regions of the world.

Also, our study has identified several possible gaps between knowledge and behavior competencies among China CRNs. For example, we found that the China CRNs had the greatest gaps in knowledge/behavior competencies related to more abstract concepts, such as ethical principles, leadership and professional development, protocol compliance, and document management categories along the ONS 2016 competences model. However, in general they showed better balance between knowledge/behavior in the more tangible dimensions, such as data management and information technology, subjects recruitment, subjects management, informed consent, and financial management. This shows clearly where future training modules could potentially focus on to achieve the greatest efficacy in educating the China CRN workforce. In fact, the results of the self-assessed competency from this study have been used by one of the authors to guide the design of the first online and onsite training courses exclusively for CRNs in China to bridge the gaps between knowledge and behavior in CRN practice in China (Liu et al., 2020a); in addition, a consensus on the management of CRNs in China based on the results of the present study has been posted online (Liu et al., 2020b).

Last but not least, a careful examination of the motivations of the 638 CRNs in choosing this profession is revealing. Some became CRNs by chance, others by intentionally avoiding the pressure and troublesome work hours associated with regular clinical nursing. However, it is reassuring and even encouraging to observe that the greatest number of CRNs in China had chosen this profession by their interest in research and they were driven by a passion to make greater contributions to society in general and clinical research/new drug development in particular. It shows that overall, the current CRN workforce in China has a very healthy attitude toward this profession and further cultivation of their passion and talents by their management, hospital administrators, national regulators, and the clinical research industry stakeholders at large would bear fruits in the future.

Conclusion

In summary, as the clinical trials industry in China grew robustly in recent years, the demand for more qualified CRNs also rose. However, little research had been done to characterize the profile of the CRN workforce in China. To our best knowledge, this is the first large-scale survey of CRNs in China. Our study results depict the China CRN workforce that consists of predominantly female nurses working for either SMOs or for hospitals’ nursing departments, clinical departments, or clinical trial offices. The majority of these CRNs hold a Bachelor’s degree. They are mostly working in the largest cities in China where most clinical trial activities concentrate. Compared with CRNs in western countries, the China CRNs are younger and relatively inexperienced (especially in the knowledge domain). However, these China CRNs are overall well educated and very driven, aspiring for further professional career advancement. The results of the present study have already been used to design training courses for CRNs in China to bridge their gaps between knowledge and behavior.

Key points for policy, practice, and/or research

• CRNs in China were a relatively young population with a mean age of 35 years, mainly located at first-tier cities and emerging first-tier cities. Bachelor’s degree was the most common educational background for CRNs. The average years of research experience slightly differed among CRNs from different employment entities.

• The level of job satisfaction of CRNs was highest during their collaboration with investigators, followed by CRCs, trailed by CRAs. Overall, CRNs in China had the highest level of satisfaction with the sense of accomplishment at work, and lowest level with their job income.

• There were some gaps between the CRNs’ competencies in knowledge and behavior. Overall, the gaps were the widest along the ethical principles, leadership and professional development and the narrowest at data management and information technology.

• The most common reasons that the China CRNs had chosen this profession was “interest in clinical research/clinical trials,” “expand on current responsibilities,” and “feels that this profession has great value and wishes to make greater contributions to clinical search/new drug development.”

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr Yuan Sheng, Medical Writer, Pfizer China Medical Writing, for literature research, manuscript revision suggestions, and editorial assistance. No monetary transaction was involved.

Biography

Peng Hao, has more than 10 years’ experience in clinical trial management for over 200 clinical trials. Core member of International Association of Clinical Research Nurses Shanghai-China Chapter.

Linda Wu, Master of Science in Nursing, formerly the Founding Director of the Clinical Trial Center at Loma Linda University Health California USA. Co-chair of global development workgroup, International Association of Clinical Research Nurses.

Liu Yanfei, Master of Medicine, Associate Professor of Nursing, Director at the clinical trial office of Fudan University Shanghai Cancer Center with 17 years’ experience in clinical trial research management. Founder and President of International Association of Clinical Research Nurses Shanghai-China Chapter.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: This study was funded by Clinical Research Plan of SHDC (Shanghai Hospital Development Center, No. SHDC20CR4005B).

Ethics: This is a survey study, recorded information cannot readily identify the participant. Any disclosure of responses outside of the research would not reasonably place clinical research participant at risk. Therefore, the ethical permissions were not applicable.

References

- Abramson Cancer Center Clinical Research Unit (2021) Job Posting Clinical Research Nurse D (Abramson Cancer Center Clinical Research Unit) Job With University of Pennsylvania | 2007035. Available at: https://careers.insidehighered.com/job/2007035/clinical-research-nurse-d-abramson-cancer-center-clinical-research-unit-/ (accessed 20 August 2021). [Google Scholar]

- American Nurses Association (2016) IACRN Clinical Research Nursing: Scope and Standards of Practice Book. Silver Spring, MD: American Nurses Association. [Google Scholar]

- baijiahao.com (2020) How Does it Feel to be a Male Nurse in China? Available at: https://baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1671696216165201011&wfr=spider&for=pc (accessed 17 August 2021). [Google Scholar]

- Bevans M, Hastings C, Wehrlen L, et al. (2011) Defining clinical research nursing practice: results of a role delineation study. Clinical and Translational Science 4(6): p421–427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carson-Newman (2021) By the Numbers: Nursing Statistics 2021 . Available at: https://onlinenursing.cn.edu/news/nursing-by-the-numbers (accessed 17 August 2021). [Google Scholar]

- Castro K, Bevans M, Miller-davis C, et al. (2011) Validating the clinical research nursing domain of practice. Oncology Nursing Forum 38(2) pE72–E80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Drug Evaluation (CDE), National Medical Product Administration, China (2021) Available at: http://www.chinadrugtrials.org.cn/clinicaltrials.tongji.dhtml (accessed 14 March 2021).

- CFDA (2015) Announcement on Carrying Out Self-Inspection & Verification of Drug Clinical Trial Data No. 117 . Available at: http://www.mofcom.gov.cn/article/b/g/201509/20150901120479.shtml (accessed 11 March 2021). [Google Scholar]

- China briefing (2017) 2017 China City Business Charm Ranking . Available at: https://www.china-briefing.com/news/chinas-city-tier-classification-defined/ (accessed 20 August 2021). [Google Scholar]

- Chinadrugtrials.org.cn (2021) Total number of Registered China Drug Trials Up to Date. Available at: http://www.chinadrugtrials.org.cn/clinicaltrials.tongji.dhtml (accessed 28 February 2021). [Google Scholar]

- City of Hope (2021) Job Posting. Community Practice Clinical Research Nurse - S. Pasadena Job With City of Hope | 551484. Available at: https://jobs.sciencecareers.org/job/551484/community-practice-clinical-research-nurse-s-pasadena/ (accessed 20 August 2021). [Google Scholar]

- Cooke NJ, Hilton ML. (eds). (2015) Enhancing the Effectiveness of Team Science . Washington, DC: National Academies Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckardt P, Hammer MJ, Barton-Burke M, et al. (2017) All nurses need to be research nurses. Journal of Clinical and Translational Science 1(5): 269–270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hastings C, Fisher C, McCabe M. (2012) Clinical research nursing: a critical resource in the national research enterprise. Nursing Outlook 60(3): 149–156.e1-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Association of Clinical Research Nurses (2012) Enhancing Clinical Research Quality and Safety through Specialized Nursing practice. Scope and Standards of Practice Committee Report. Pittsburgh, PA: International Association of Clinical Research Nurses. Available at: https://iacrn.org/aboutus (accessed 23 August 2021). [Google Scholar]

- International Association of Clinical Research Nurses (2016) Clinical Research Nursing Scope and Standards of Practice . Silver Spring, MD: American Nurses Association. [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Liu X, Qiao J, et al. (2020. a) Clinical Research Nurse: Program for Improvement and Development of Professional Competencies . Available at: http://iacrn.cn/ (accessed 23 August 2021). [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Ge J, Zhao Q, et al. (2020. b) Consensus on the Management of Clinical Research Nurses in China (White Paper; Solicitation for Public Opinions) . Available at: http://iacrn.cn/ (accessed 23 August 2021). [Google Scholar]

- McCabe M, Behrens L, Browning S, et al. (2019) CE: original research: the clinical research nurse: exploring self-perceptions about the value of the role. Applied Neuropsychology Adult 119(8): 24–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China (2017) Yearbook of Health and Family Planning Statistics in China. Beijing, China: Union Medical University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Oncology Nursing Society (ONS) (2016) Oncology Clinical Trials Nurse Competencies . Available at: https://www.ons.org/sites/default/files/2018-10/Oncology_Clinical_Trials_Nurse_Competencies.PDF (accessed 28 February 2021). [Google Scholar]

- Rockefeller University Hospital (2021) Launching the Modern Field of Research Nursing . Available at: https://heilbrunnfamily.rucares.org/History (accessed 15 August 2021). [Google Scholar]

- Scavone C, di Mauro G, Mascolo A, et al. (2019) The new paradigms in clinical research: from early access programs to the novel therapeutic approaches for unmet medical needs. Frontiers in Pharmacology 10: 111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US FDA (2018) What are the different types of clinical research? Available at: https://www.fda.gov/patients/clinical-trials-what-patients-need-know/what-are-different-types-clinical-research (accessed 16 August 2021).

- Wang C, Shen J, Liu Y. (2021) Administrative level, city tier, and air quality: contextual determinants of hukou conversion for migrants in China. Computational Urban Science 1 6. [Google Scholar]

- Zippia.com. (2021) Clinical Research Nurse Demographics and Statistics In The US . Available at: https://www.zippia.com/clinical-research-nurse-jobs/demographics/ (accessed 17 August 2021). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.