Abstract

Background

Clinical Research Nurses practice across a wide spectrum of roles and settings within the global research enterprise. Clinical Research Nurses working with clinical trials face a dual fidelity in their role, balancing integrity of the protocol and quality care for participants.

Aims

The purpose of this study was to describe Clinical Research Nurses’ experiences in clinical trials, educational preparation, and career pathways, to gain a deeper understanding of clinical research nursing contributions to the clinical research enterprise.

Methods

An internet-based survey was conducted to collect demographic data and free text responses to four open-ended queries related to the experience of nurses working in clinical trials research, educational preparation, and role pathways. Qualitative content analysis was used to analyze free text responses. The study was guided by the Clinical Research Nursing Domain of Practice and Duffy’s Quality Caring Model of relationship centered professional encounters.

Results

Forty clinical research nurses responded to the open-ended questions with themes related to dual fidelity to study participants and protocols, relationships and nursing care, interdisciplinary team membership and contributing to science, emerging from the data. Gaps in educational preparation and professional pathways were identified.

Conclusion

This study provides insights to unique clinical research nurse practice contributions in the clinical trial research enterprise within a context of Duffy’s Quality Caring Model.

Keywords: clinical research nurses, clinical research nurses role delineation, clinical trials, educational preparation, Quality Caring Model©, relationships, study coordinators

Introduction

Clinical Research Nursing is the specialized practice of professional nursing focused on maintaining equilibrium between care of the research participant and fidelity to the research protocol (IACRN, 2012). Although the need for clinical research nurses has surged to the forefront of public awareness during the COVID-19 pandemic, this nursing specialty has been supporting critical research for decades. Challenges during the pandemic included managing the worldwide crisis, gathering clinical data, designing treatments to mitigate or prevent acuity of the illness, and building a biorepository to understand symptom management and vaccine development. Consequently, the research community, including clinical research nurses, went into overdrive to develop lifesaving therapeutics and treatments. Hence, the pandemic of COVID-19, with the associated need for rapid research and clinical trials, accentuated the important contributions nurses specializing in Clinical Research Nursing make to public health. Other challenges in clinical research include increasing complexity of clinical research studies and challenging study populations (Getz & Campo, 2017).

An estimated 10,000 clinical research nurses (CRNs) are found working across a wide spectrum of roles and settings within the global clinical research enterprise (American Nurses Association and International Association of Clinical Research Nurses, 2016; Wallen and Fisher, 2018). Previous role delineation studies on CRNs have primarily focused on nurses working in acute care, dedicated research units, or clinic settings (Bevans et al., 2011; Castro et al., 2011; Ehrenberger and Lillington, 2004), yet many other professional settings exist. These settings include contract research organizations and biopharmaceutical companies where CRNs work as project managers, study monitors, auditors, and directors. Nurses have also held positions as medical science liaisons, monitors, and other professional roles within biotechnology or pharmaceutical company settings. Likewise, many nurses have also worked in regulatory and government agencies, as Food and Drug Administration (FDA) inspectors or commissioners and as project managers and clinical research educators in federal institutes. These complex research settings create the environment in which the CRN provides a critical linkage between the patient, family and the research team.

Clinical research nurse domain of practice

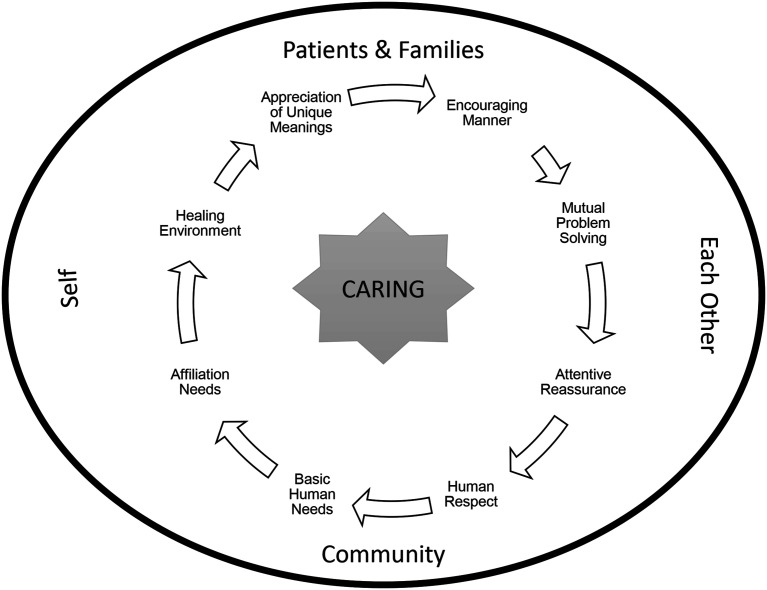

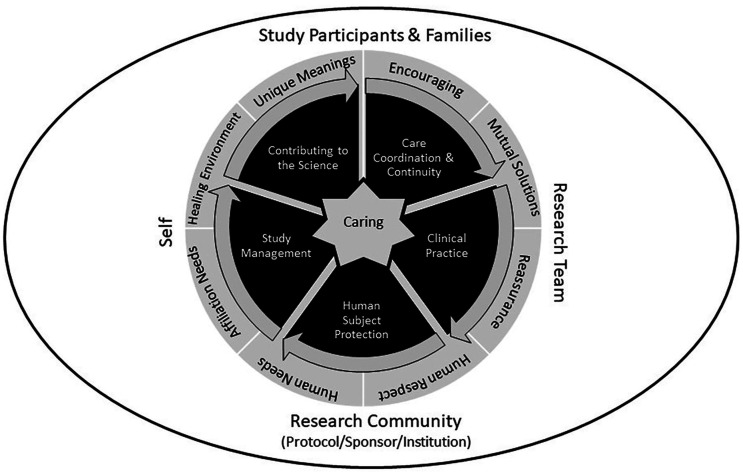

A team from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), Clinical Center, Nursing Department, defined the Clinical Research Nursing Domain of Practice (Figure 1) differentiating skillsets under five categories: (1) Care Coordination and Continuity; (2) Clinical Practice; (3) Human Subjects Protection, (4) Study Management, and (5) Contributing to the Science (CRN 2010 Domain of Practice Committee, 2009). This work led to the formation of the International Association of Clinical Research Nurses (IACRN), the development of the scopes and standards of practice for clinical research nurses, and the acceptance of the CRN specialty practice by the American Nurses Association (American Nurses Association and International Association of Clinical Research Nurses, 2016). Henceforth, research has been conducted on nursing roles in oncology (Purdom et al., 2017); nurses perceptions of their value to clinical research protocols and participant care (McCabe et al., 2019); and issues in isolation from other nurse colleagues, and stress in dichotomizing patient advocacy and protocol adherence (Hernon et al., 2020).

Figure 1.

Clinical research nursing domain of practice.

The setting for clinical trials research is multi-dimensional and includes broader interdisciplinary relationships and responsibilities with patients, clinical research teammates, investigators, other interdisciplinary teams, laboratories, ethical boards, research sponsors, and monitors. Moreover, CRNs are often responsible for multiple simultaneous and overlapping clinical trials (Gwede et al., 2005). Within the context of operationalizing clinical trials, CRNs consider the study participants (and their families) as their patient populations. Balancing clinical care, the clinical trial protocol boundaries, regulations, and bioethics, CRNs are dedicated to excellence in patient care and fidelity to the research. Though not working in the traditional clinic or bedside setting, CRNs very much identify as a nurse and feel strongly about their contributions to the care of participants and to innovative discoveries that prevent, treat, cure, or mitigate diseases.

Theoretical context

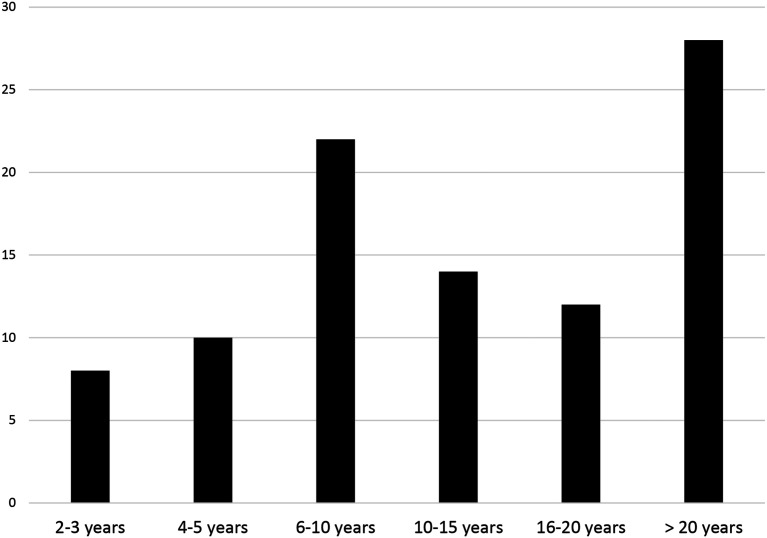

The CRN role in clinical trials operations and patient management fits naturally with the Quality Caring Model©, a theory developed by Joanne Duffy that was used to better understand nursing roles in terms of an evidence-based practice and nursing’s unique contributions (Duffy and Hoskins, 2003). The Quality Caring Model© comprises two types of caring relationships: independent relationships (nurse to patient/family; discipline-specific interventions), and collaborative relationships (nurse to other members of healthcare team; activities and responsibilities) (Figure 2). Similar to the role of nurses as described by Duffy, the focus of the CRN is on the patient from a clinical trial participant perspective and on the collaborative relationships with the research team in conducting the research.

Figure 2.

Duffy’s Quality Caring Model.

Source: Quality Caring Model©

This research focused on the role of CRNs working in clinical trials of investigational new drugs and devices. The purpose of this study was to explore the CRNs’ perceptions of their unique contributions to clinical trials research, their educational preparation, and progression pathways for their roles by telling their stories.

Methods

Sample and data collection

An online survey was conducted to explore nurses’ written descriptions of working and supporting clinical research utilized Qualtricsxm (Qualtrics, Provo, UT, version 9, www.qualtrics.com) internet-based survey platform. The survey tool was piloted with two volunteer participants to improve quality. Participants were invited via email through the International Association of Clinical Research Nurses (IACRN) membership listserv (approximately 360 members), and via social media (e.g., LinkedIn, and Twitter). A study flier, including a URL and QR code inserted in both email and social media invitations were accessible via computer and mobile technology. Members of the research team also informally shared the survey flier to CRN colleagues. Responses were anonymous. The first “question” of the survey was the informed consent form. By clicking “Yes,” participants were automatically advanced to Question two and the remainder of the survey or exited if “No” was clicked. The survey properties allowed participants to complete the survey in one sitting or to leave the survey at any time and return to it, picking up where they left off. The survey was launched during the Summer of 2019. The snowball approach precluded an ability to estimate an accurate denominator.

Participants

The survey was aimed at nurses working in clinical trials research. The two participation criteria were:

1. Licensed (Registered) Nurse (RN) whose role was to support clinical trials research with at least 2 years of experience in the clinical research nurse role, and

2. Willing and able to answer the qualitative questions in written English.

The authors were excluded from survey participation.

Data collection

The survey included a demographic section (12 objective questions), followed by four open-ended queries where participants were invited to share their “stories” as nurses working in support of clinical trials research and their educational preparation and role progression, via free text input (Table 1).

Table 1.

Open-ended survey queries.

| Queries about the CRN role | Queries about education and role progression |

|---|---|

| 1. Please tell us what being a nurse who supports clinical trials research means to you | 1. Please tell us your feelings about your educational preparation for your clinical research roles as a nurse |

| 2. Please tell us one story about a unique experience you have had as a nurse in a clinical trials research role | 2. Please describe your career progression from your first clinical research position as a nurse, to today |

We allowed 15,000 characters for each open-ended item (equivalent to 4.5 single-spaced pages each).

Data analyses

Descriptive statistics were used to organize and describe the characteristics of the survey respondents. Researchers used inductive content analysis to analyze participant open-ended written responses and identify themes or patterns (Hseih and Shannon, 2005). Working in pairs, two members of the study team used NVivo (QSR International, Pty Ltd, Version 12, 2018) and MS Excel® (Microsoft Corporation, MS Office, Version 2016) for initial independent coding of written participant responses. In a second review, the team sought to compare concurrence for common themes. A third review was conducted to determine thematic level of meaning units, and consolidate categories that were similar. The qualitative data were also circulated to additional team members to determine final consensus of meanings and themes.

Findings

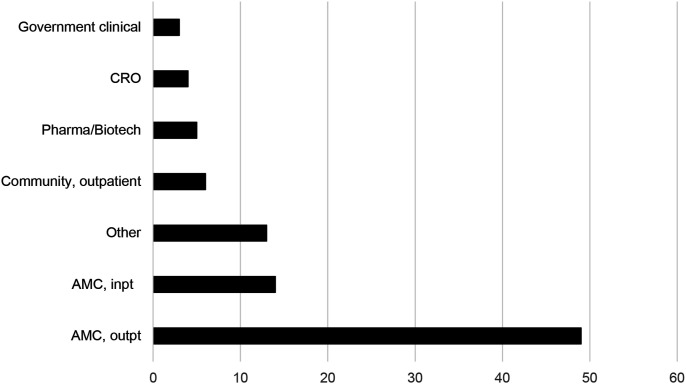

We expected a response rate of 50; however, we had an enthusiastic response of 100 respondents. Of those, 97 met entry criteria. The majority of respondents were female (90%). The sample consisted of individuals who were highly experienced in clinical trials research, the majority of whom (30%) had greater than 20 years of clinical trials experience, followed by 23% having 6–10 years of experience (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Years of experience working in clinical trials.

Respondents listed broad ranges of job titles. Of the 90 reported job titles, there were 65 unique titles. Similar titles were grouped together to facilitate role categories (Table 2). The most frequently reported title was Research Nurse/Clinical Research Nurse 30 (33.3%). Titles grouped as “Other” (7.8%) included: Biostatistician, Clinical Nurse Specialist, Clinical Research Associate, Coverage Analyst, Medical Data Review Manager, Protocol Interpreter, and Rural Nurse Specialist.

Table 2.

Frequency of job title categories.

| Job title category | Frequency | % |

|---|---|---|

| Research nurse/clinical research nurse | 30 | 33.3 |

| Research program manager/coordinator | 19 | 21.1 |

| Clinical research nurse coordinator | 14 | 15.6 |

| Project management | 8 | 8.9 |

| Other | 7 | 7.8 |

| Quality assurance | 4 | 4.4 |

| Research consultant | 3 | 3.3 |

| Research nurse practitioner | 3 | 3.3 |

| Research education nurse | 2 | 2.2 |

| Grand total | 90 | 100 |

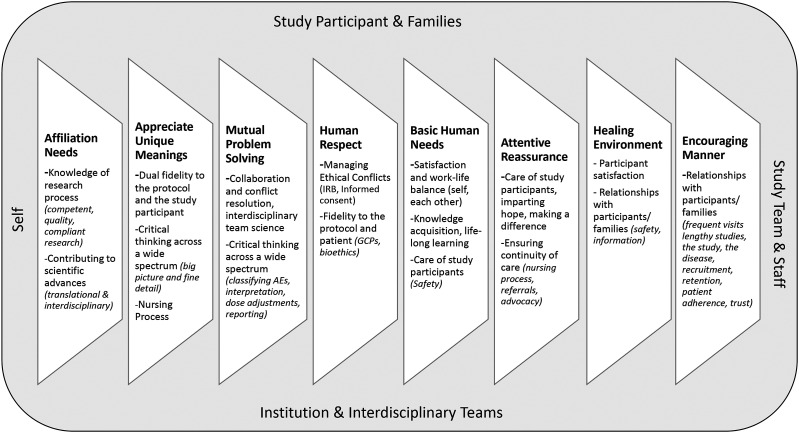

Participants worked in a variety of work settings (Figure 4), with most (52%) working in outpatient settings at academic medical centers (AMCs), followed by AMC inpatient (15%) (Figure 4). One indicated that they worked for the NHS Foundation Trust (United Kingdom) and another at a College of Nursing. No participants worked at US regulatory authorities (e.g., FDA) or non-clinical government agencies.

Figure 4.

Work settings of clinical trial nurse respondents.

Note: CRO = contract research organization; pharma/biotech = pharmaceutical or biotechnology companies; AMC= academic medical center; inpt = inpatient; outpt = outpatient.

Most respondents worked in the United States (84%) followed by UK (6%) and Ireland (4%). We also had a respondent from India and New Zealand. Those working in the United States lived primarily in the Northeast and Southeast with a decreasing frequency from the Midwest, West, and Southwest.

Clinical Research Nurse perception of role of the nurse in clinical trials

Themes that emerged from the data in response to the two open-ended questions, “Please tell us what being a nurse who supports clinical trials research means to you” and “Please tell us one story about a unique experience you have had as a nurse in a clinical trials research role” included (1) dual fidelity in the role, (2) unique contribution to research enterprise, and (3) impact on patients through relationships.

Forty-six respondents described that being a clinical research nurse conducting clinical trials means having opportunities to contribute to the clinical research enterprise and to new scientific advances through knowledge of the research process and nursing expertise in care of clinical research participants. They expressed their role in ensuring dual fidelity to the protocol and participant care and safety. Respondents expressed an additional added value by having critical thinking skills spanning an ability to grasp the “big picture” for the research aims and an ability to attend to fine detail, especially safety tracking. Further, they also expressed personal and professional satisfaction in their roles, being able to impart hope through this work and to nurture longer relationships with study participants throughout the life of a study. Respondents enjoyed opportunities for work-life balance, many shared work schedules being traditionally daytime work hours and that they had opportunities to be upwardly mobile through engagement with the clinical research teams.

Thirty respondents shared a story about their unique experiences as a clinical trials nurse. Respondents shared stories as adult and pediatric clinical trials nurses, as nurses working in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), oncology and cardiology research, and as nurses working across the spectrum of drug and device development processes and settings, including those who worked for sponsors and other biotechnology companies. Saturation of the common themes was reached at the 15th story. We included excerpts from the contributed stories to lend voice to the study participants (Table 3).

Table 3.

Story excerpts from CRN respondents.

| Duel fidelity to the protocol and to the patient | “I have two patients: the protocol and the participant in the trials.” |

| “Advocating for study participants and their families, ensuring the study is conducted in a way that will produce meaningful outcomes to a larger patient population.” | |

| “I am able to assess risk throughout the continuum of the protocol lifecycle and make impactful decisions to participant safety and data integrity.” | |

| “Bringing all of my nursing, science, and regulatory experience to operationalize clinical trials with the highest critical thinking, ethics, scientific thought processes and ethical and protective participant management skills.” | |

| “I had a participant suffer a serious adverse event that required hospitalization. The study was blinded and the inpatient staff and family wanted to have the study treatment un-blinded. The PI also felt this way—at least initially. The sponsor did not want to un-blind at this time….” “In the end the study was ended prematurely because of 2 patient deaths. There was a lot of balancing care of the participant and care of the protocol in this situation.” | |

| Relationships with participants and families | “As nurses we build important nurse: patient relationships affording education of patients about their disease, research and clinical expertise and care…. We are part of a clinical trial that changes people’s lives.” |

| “I am on the frontline of the future of medicine . . . I am always learning and improving the health and well-being of my patients…telling them that there is hope and almost always another choice.” | |

| “The mother pulled me aside and said...‘I have been so frightened about all of this for so long, about HCM (hypertrophic cardiomyopathy), about my son being sick and in a clinical trial, but after today I feel better informed about HCM, stronger about it and safe.’ ‘She cried and hugged me.’…I have been working with participants and their loved ones for the last two years. The process of informed consent combined with the extensive baseline visit for this study have presented the study team with opportunities to share their expertise and to begin to forge trusting relationships with the participating family.” | |

| “I’ve been able to play a part in providing patients something life changing through a clinical trial that they would not have gotten in any other way. Seeing what a positive change research can make in their lives is rewarding.” | |

| “I was working on a study with Autistic children and we were having difficulty getting a good clear EKG tracing, and to attempt them to stay still for 10 seconds was next to impossible. So with IRB permission, we had the parents at night place the child in the car, drove around and they drove to our parking lot. I got in the car with the portable EKG machine and while he was relaxed and falling asleep I placed the lead stickers to his chest . . . and got our clear EKG tracing.” | |

| “I met with the parents at the end of the participation in the study . . . each one sat with me, wanting to tell me their story of their lives before this oral medication and now. They had each been on continuous IV therapy and were able to be transitioned to one pill, twice a day.” | |

| “I had a premature infant with CMV in a study and was with the mother and father when they made the decision to withdraw support on a baby whose quality of life was rapidly worsening. I was able to see the joyful and sorrowful side of research but not saturate too much of it.” | |

| “An oncology patient with stage 4 bowel cancer. Over the next 5 years the pt (patient) would return anywhere from 1-3 times a week for treatment and then eventually enter long-term follow-up. What was supposed to be a poor prognosis turned into a miracle as the patient fully recovered from his colon cancer and 4-month ICU stay. Ten years later that patient is still alive and when I see him on campus he always stops and offers a warm hug and smile” | |

| “On a diabetes study that required the implantation of a device meant to deliver a glucose lowering drug to study subjects. Knowing what equipment would be needed and the ability to educate the subject and his wife to allay their fears and watch the subject for any untoward effects provided a smooth course for the subject.” | |

| Contributing to science and interdisciplinary systems | “I am on the cutting edge of discovery.” |

| “I am a nurse running trials that are curing hepatitis C. I never thought that was something that could happen. In 2003 I was told it was something that could come back at any time. Over the last few years and many drug formulations HCV is now a curable disease that is being treated with all oral medication Respondents shared stories as adult and pediatric clinical research nurses, as nurses working in HIV and oncology research, as nurses working across the spectrum of drug and device development process, and of CRNs who worked for sponsors and other biotech companies. . . I have expanded my role to work on other trials other than liver disease.” | |

| “I used to work in HIV research when there were almost no medications available and every participant was very very sick. Being involved in the first studies using drug combinations stands out as a turning point in my career.” | |

| I was able to give a Phase I drug for the first time in a human, EVER and continue to follow that patient through the entire study, as well as follow that study through to publication.” | |

| “One of our patients who had enrolled in an adjuvant chemotherapy trial for early stage breast cancer was denied coverage for the study drug (by their insurance company). I was forced to learn the details related to insurance coverage laws and exceptions to those laws . . . I was able to get the costs of care already received covered but the patient had to be taken off the trial. Since then we have worked as a team with the case manager to gain a better understanding of the implications of conventional vs research costs and to create educational materials to help inform patients about those implications.” | |

| “I am asked to review protocols from a nursing clinical perspective. Is something feasible? Are the visit windows wide enough?” | |

| “I was asked to support a cardiovascular device trial. The team had a need for someone with a clinical background to review medical records that were collected to support the study. As I reviewed these records, I discovered errors in the data that had been submitted by clinical trial sites. This turned out to be a widespread issue, and I suddenly found myself in a position where I was the only individual with the necessary background to understand what went wrong and to develop a plan to correct the problem.” “The study leadership team recognized the value of my contributions to the study, and invited me to be a co-author on the study’s primary manuscript….the paper was published in a top-tier medical journal. The experience helped to elevate the role of clinical research nurses in the organization. ..Many members of the organization came to understand the critical role of a nurse with a QA and compliance focus in clinical research.” | |

| “I was offered the opportunity to join a speaker’s bureau. . . . It eventually led to being a faculty for the NCI program on Community and Administrators Education on Clinical Trials. . . . Not only did the speaking experience help my career- it introduced me to many mentors outside my home location. Through my interactions I learned better ways of doing things, and gained more experience.” | |

| “In auditing a device clinical trial I noticed the lack of controls around a cardiac valve device made of porcine material, also not disclosed in the consent form. …the sponsor changed the ICF and device management across the sites.” |

The respondents' written narratives provided insights to the unique contributions of CRNs in clinical trials, not only in navigating the dual fidelity to the protocol and study participants, but nursing care of participants including a relationship between the patients and their caregivers in imparting hope, ensuring continuity of care during the study treatment and in long-term follow-up, and teaching. CRN stories further illustrated the range of critical thinking skills and expertise used in solution finding and contributions as members of interdisciplinary teams and to the science under study. CRNs working in clinical research enjoyed being on the cutting edge of research to make a difference for future patient groups and an autonomy in their practice that contributed to work satisfaction and work–life balance.

Clinical research nurse perceptions of educational preparation and role progression

Themes that emerged from the data in responses to the two questions: “Please tell us your feelings about your educational preparation for your clinical research roles as a nurse” and “Please describe your career progression from your first clinical research position as a nurse, to today” included: (1) lack of educational preparation for the role; (2) skills increased with experience, and (3) supervisory role emerged with experience.

Forty-five participants responded to the query about educational preparation. Data saturation was noted after the 10th sequential response. Generally, the respondents affirmed that their BSN education prepared them to give excellent care of patients and critical thinking skills. Most had no preparation in undergraduate school in subject matter related to clinical trials, and the CRN role. They “learned on the job” regarding new medical product development, or regulatory affairs topics. Moreover, they also learned from non-nurses who were either assisting with or external monitors of the clinical trial data.

Those with graduate-level nursing education had increasing knowledge of nursing research and research ethics but still felt they lacked an understanding of clinical trial research methods and clinical trials operations in that coursework. One student working at the National Institutes of Health Clinical Center relayed that they had many opportunities to learn more about clinical research at their institution, but the initial education was “on-the-job” training. Two participants shared that they had an MSN specifically in Clinical Research Management and later sought a terminal degree in clinical research. One respondent felt like they were a novice again when they transitioned from hospital nursing to a clinical research role, yet another stated that her work as an oncology nurse helped prepare her for the role.

A number of trends emerged from the descriptions of career paths reported by the respondents. Many of the respondents described their career trajectory starting at the bedside and moving upward into assistant management, management, supervisory or directors’ roles. An initial theme that emerged was that of the traditional career path upward movement and opportunities that were presented while expanding skills and knowledge as a research coordinator. Several respondents described their role and skills sets evolving to include research or data, quality, or safety monitoring with increasing responsibilities added over time. Skills within these roles included subject recruitment, data management, and data cleaning for sponsors.

Supervisory responsibilities reported with the upward movement into management positions included roles such as assistant nurse manager, nurse manager, and administration and director positions. The career paths demonstrated opportunities within the clinical research arena to apply learned skills from managing clinical trials to management of staff and resources necessary to run a research unit, teams, or department. Others mentioned management of research registries and repositories as well as clinical trials.

One participant shared the opportunity to move up to an Associate Director position in clinical research, managing budgets, and staff along with IRB responsibilities. Some of the research sites mentioned included hospital settings, CROs, and academic settings. Although the employment sites described varied, the skill sets seemed to be transferable to the different settings and built upon previous skills and knowledge as careers progressed.

Another trend noted was that several of the respondents were Quality Assurance (QA) Specialists or the QA nurse in their unit or hospital and participated in audits and data management. In addition to the trends noted in career path progression, the respondents also reported a variety of certifications obtained along the way ranging from certifications in research to certifications in specialty practice areas.

Overall, the responses to the question regarding career path progression were widely varied but were similar in that the skills and experiences obtained in the work setting often led to the next level of the career path (Table 4). Respondents described their career path as “typical” and “confidence building” as they moved to the next level. Another described the desire to stay on the research pathway as, “a feeling of making a difference and an opportunity to provide hope,” to patients that would not otherwise have this option.

Table 4.

Education and role progression.

| Lack of educational preparation for the role | “I didn’t know clinical research was an option in nursing school, which is really a shame because I went to a school linked with the organization I work for now. . . . The only way clinical research was mentioned was in terms of a nurse scientist performing nursing research.” |

| “Everything I know about clinical research I learned on the job.” | |

| “In my BSN – NONE! Though I did attend _____University for an MSN in Clinical Trials. This degree prepared me to take on many leadership roles and to advance my career into something that I would have ever imagined.” | |

| “I was fortunate to complete a MSN in Clinical Research Management early in my career. Subsequently I also completed a research doctorate in health sciences. I struggled to find a doctoral program that matched my career objectives…Most DNP programs were too focused on advanced clinical practice” | |

| Skills increased with experience | “When I took on a research role, I was the first research RN in my department and I was completely self-taught. I learned a lot from my first study monitor.” |

| “Transitioning to a research role was very difficult. Nothing in my past career or academic education prepared me for the job. I feel like I went from novice again overnight. . . . the transition occurred primarily through on the job training. It took a great deal of time.” | |

| “My career as an oncology nurse made it much easier to transition into this role.” | |

| Supervisory roll emerged with experience | “I came in knowing nothing about being a research nurse. I learned on the job. Now I have a position as a RN Project Manager where I lead, manage and guide the study teams to perform high quality research.” |

| “I started out as what we were calling a study coordinator, but I was basically a one nurse clinical trials show, doing all the work for clinical trials in my department. I also worked for several years part time for another department, managing research for investigators in several departments. Now I am called the Associate Director of Clinical Research in my department with the goal of setting up a departmental research structure, though I still handle a lot of task based work such as IRB applications, communications with other departments and sponsors, budgets, and patient care, in addition to supervising staff. I also do some work as a monitor on several investigator initiated studies throughout the hospital.” | |

| “I started as a clinical research nurse coordinator progressed into a research nurse supervisor and manager at an academic institution. Then I moved into administration as a clinical research director for a hospital system and finally a clinical trial manager, associate director for a Contract Research Organization (CRO).” |

Summary observations

Applying Duffy’s Quality of Caring Model©

Emerging from the data, Duffy’s theoretical model was aligned with the domains of practice which are well documented as a framework for the CRN within the literature. This model supports the relationships described by CRNs in the context of team science, adherence to the protocol and clinical care. These relationships included potential and enrolled study participants (patients) and their families, relationships as a contributor to interdisciplinary teams within the institution (investigators, clinical nurses, laboratory personnel, regulatory bodies, sponsors, monitors, government agencies, insurance companies), interdisciplinary teams outside of the institution (sponsors, monitors, government agencies), and their immediate clinical research staff (other CRNs, other study staff, regulatory coordinators, schedulers, institutional review boards, patient escort). Last, “relationship with self” included the themes of life-long learning, job satisfaction, and work–life balance were described by respondents and represent certain self-sustaining benefits as they progressed in their professional CRN roles.

We illustrate the relational aspects of quality caring associated with the work of Clinical Research Nurses based on our qualitative findings in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Quality caring factors and clinical research nursing roles.

Discussion and recommendations

This study gives voice to CRNs and provides insights into how CRNs make meanings of their clinical research profession. The qualitative questions were open-ended, asking participants to “tell us.” We avoided introducing bias, by not including language that suggested that written responses and stories were to highlight unique contributions or to ascribe value of the CRN role. Themes emerging from the meaning and story queries support the CRN Domain of Practice (CRN 2010 Domain of Practice Committee, 2009), Scopes, and Standards for Clinical Research Nursing (American Nurses Association and International Association of Clinical Research Nurses, 2016).

Recognized by the ANA as a specialty practice in nursing in 2016, CRNs have existed for decades making significant contributions to the clinical research enterprise. However, the role is rarely described in undergraduate nursing coursework as a possible career path (Galassi et al., 2014). CRNs are critical members of interdisciplinary teams and can work across varied settings. In addition to nursing knowledge, and clinical research expertise, the caring attribute of CRNs enables them to successfully navigate multiple relationships and systems to effectively and safety coordinate multiple clinical trials and simultaneously care for clinical research participants. The importance of continuing to further explore and define the role of the clinical research nurse is foundational to the research enterprise on several levels. For example, research teams are moving toward hiring less costly personnel to collect research data in order to reduce the expense of conducting clinical trials. This movement can clearly cause potential risk to the research participates in terms of monitoring for changes in clinical conditions as nurses are so highly trained to do (Jones et al., 2015; McCabe et al., 2019).

The Quality Caring model has been applied to various nursing roles in adult and pediatric settings (Edmundson, 2012; Meunier-Sham et al., 2019; O’Nan et al., 2014). We were able to attribute CRN roles to the eight quality caring behaviors described by Duffy and Hoskins (2003) and found it complementary to the existing CRN Domain of Practice (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Model of the clinical research nurse domain of practice in a quality caring context.

Study limitations

The limitations of this study included the snowball sampling recruiting CRNs from a professional association listserv and by using social media invitations. The respondents may be considered self-selected to get their voices heard and limited to those comfortable in written English. Moreover, the respondents were mostly performing their clinical research roles at academic medical centers (67%); therefore, there may be bias in the results. There was a greater than expected initial response rate; however, many more survey respondents contributed descriptive and demographic information, and did not complete the open-ended section suggesting survey fatigue or time conflicts. On average, 40 of the 97 respondents (approximately 41%) took the time to share their written stories in the open-ended section of the survey. The majority of participants resided in the eastern regions of the United States.

Recommendations

Future research should explore the unique education needs and contributions of CRNs. Additional research applying nursing theoretical models, such as Duffy’s Quality Caring Model should be performed, to gain deeper understanding of the CRN specialty practice. Research on CRN workload and self-care would also be beneficial. With the onslaught of COVID-19, additional role factors should be studied, such as safety of CRNs in the workplace during a global pandemic, team science, and opportunities for CRN innovations such as the use of telemedicine, electronic signature technology for clinical trial informed consents, and mobile technology for data collection and remote site monitoring visits.

Conclusion

This study collected qualitative survey responses from experienced clinical research nurses who were queried about their individual perceptions about the meaning of their CRN work, sharing a story from that work, and describing their career pathways and educational preparation. The Quality Caring Model© provides a systematic way to demonstrate the caring and relationship aspects of CRN roles in the context of complex clinical trials and interdisciplinary systems. COVID-19 has brought worldwide attention to the importance of bringing new treatments to the world in a timely manner through quality research. Clinical Research Nurses are key contributors to the outcomes of quality research exemplifying the caring and knowledge of the nursing profession.

Key points for policy, practice, and/or research

• Clinical Research Nurses make significant contributions to the care of patients and to the integrity of research in the context of complex clinical trials.

• Nursing academic education should incorporate more information about clinical trials research and the role of clinical research nurses.

• The Quality Caring Model provides a framework for illustrating the strength of nursing relationships with patients, with each other, with interdisciplinary team systems, and to the greater community.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge the IACRN Research Committee who encouraged us to develop and conduct this study and by the willingness of the IACRN to assist in circulating the study invitations to the membership. We also wish to acknowledge those who assisted us by sharing this study with other CRN colleagues so that we could get a wider response, and of course, the CRN survey participants who shared their stories.

Biography

Carolynn T Jones, DNP, MSPH, RN, FAAN, is Associate Professor of Clinical Nursing at The Ohio State University College of Nursing and the OSU Center for Clinical and Translational Science.

Catherine A Griffith, PhD, RN, is a Clinical Research Nurse in the Translational and Clinical Research Centers at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA.

Cheryl A Fisher, EdD, RN, is Associate Professor, Nursing Informatics, University of Maryland School of Nursing, Baltimore, MD, USA.

Kathleen A Grinke, MSN, RN, is a Clinical Research Nurse in the Translational and Clinical Research Centers at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA.

Rosemary Keller, PhD, RN, is a Global Development & Operations Clinician at Pfizer, Inc., Collegeville, PA, USA.

Hyacinth Lee, PhD, RN, oversees the day-to-day operations of the Translational Research Unit at the University of Washington Medical Center, Seattle, WA, USA.

Michelle Purdom, PhD, RN, is Vice President of Clinical Research and Operations for TG Therapeutics, Inc., New York, NY, USA.

Elyce Turba, MSN, RN, OCN, is a Clinical Research Nurse at Moffitt Cancer Center in Tampa Bay, FL, USA.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported in part by The Ohio State University, Center for Clinical Translational Science, grant number UL1TR002733 from the National Center for Advancing Clinical Translational Sciences (NCATS), National Institutes of Health (NIH) Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) program.

Ethics: This study was reviewed by our university’s IRB and designated as exempt.

ORCID iDs

Carolynn T Jones https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0669-7860

Catherine A Griffith https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3145-3649

Cheryl A Fisher https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2884-8113

Elyce Turba https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0346-667X

References

- American Nurses Association and International Association of Clinical Research Nurses (2016) Clinical Research Nursing: Scope and Standards of Practice. Silver Spring, MD: American Nurses Association. [Google Scholar]

- Bevans M, Hastings C, Wehrlen L, et al. (2011) Defining clinical research nursing practice: Results of a role delineation study. Clinical and Translational Science 4: 421–427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro K, Bevans M, Miller-Davis C, et al. (2011) Validating the clinical research nursing domain of practice. Oncology Nursing Forum 38: E72–E80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CRN 2010 Domain of Practice Committee (2009) Building the foundation for clinical research nursing: Domain of practice for the specialty of clinical research nursing. Available at: http://www.cc.nih.gov/nursing/crn/DOP_document.pdf (accessed 10 February 2022).

- Duffy JR, Hoskins LM. (2003) The quality-caring model: blending dual paradigms. Advances in Nursing Science 26: 77–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edmundson E. (2012) The quality caring nursing model: a journey to selection and implementation. Journal of Pediatric Nursing 27: 411–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrenberger HE, Lillington L. (2004) Development of a measure to delineate the clinical trials nursing role. Oncology Nursing Forum 31: E64–E68. DOI: 10.1188/04.ONF.E64-E68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galassi AL, Grady MA, O’Mara AM, et al. (2014) Clinical research education: perspectives of nurses, employers and educators. Journal of Nursing Education 53: 466–472. DOI: 10.3928/01484834-200140724-04 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Getz KA, Campo RA. (2017) Trends in clinical trial design complexity. Nature Reviews. Drug Discovery 16: 307. DOI: 10.0138/nrd.2017.65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwede CK, Johnsson DJ, Roberts C, et al. (2005) Burnout in clinical research coordinators in the United States. Oncology Nursing Forum 32: 1123–1130. DOI: 10.1188/05.onf.1123-1130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernon O, Dalton R, Dowling M. (2020) Clinical research nurses’ expectations and realities of their role: a qualitative evidence synthesis. Journal of Clinical Nursing 29: 667–683. DOI: 10.1111/jocn.15128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hseih H-F, Shannon SE. (2005) Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research 15(9): 1277–1288. DOI: 10.1177/1049732305276687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IACRN (2012) “Enhancing clinical research quality and safety through specialized nursing practice”. Scopes and Standards of Practice Committee Report. IACRN. [Google Scholar]

- Jones CT, Hastings C, Wilson LL. (2015) Research nurse manager perceptions about research activities performed by non-nurse clinical research coordinators. Nursing Outlook 63(4): 474–483. DOI: 10.1016/j.outlook.2015.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe M, Behrens L, Browning S, et al. (2019) The clinical research nurse: exploring self-perceptions about the value of the role. American Journal of Nursing 119: 24–32. DOI: 10.1097/01/NAJ.0000577324.10524.c9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meunier-Sham J, Preiss RM, Petricone R, et al. (2019) Laying the foundatinos for the national telenursing center: integration of the Quality Caring Model into TeleSANE practice. Journal of Forensic Nursing 15: 143–151. DOI: 10.1097/JFN.000000000000252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Nan CL, Jenkins K, Morgan LA, et al. (2014) Evaluation of Duffy’s Quality Caring Model on patients perceptions of nurse caring in a community hospital. International Journal for Human Caring 18: 27–34. DOI: 10.20467/1091-5710.18.1.27 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Purdom MA, Petersoen S, Haas BK. (2017) Results of an oncology clinical trial nurse role delineation study. Oncology Nursing Forum 44: 589–595. DOI: 10.1188/17.ONF.589-595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallen GR, Fisher CA. (2018) Chapter 39. Clinical research nursing: A new domain of practice. In: Gallin JI, Ognibene FP, Johnson LL. (eds) Principles and Practice of Clinical Research. 4th edition. Cambridge, MA: Academy Press, 671–686. [Google Scholar]