Abstract

Objective:

To provide high-quality healthcare, it is essential to understand values that guide the healthcare decisions of older adults. We investigated the types of values that culturally diverse older adults incorporate in medical decision making.

Methods:

Focus groups were held with older adults who varied in cognitive status (mildly impaired versus those with normal cognition) and ethnicity (Hispanic and non-Hispanic). Investigators used a qualitative descriptive approach to analyze transcripts and identify themes.

Results:

Forty-nine individuals (49% with cognitive impairment; 51% Hispanic) participated. Participants expressed a wide range of values relating to individual factors, familial/cultural beliefs and expectations, balancing risks and benefits, receiving decisional support, and considering values other than their own. Participants emphasized that values are individual-specific, influenced by aging, and change throughout life course. Participants described barriers and facilitators that interfere or promote value solicitation and incorporation during medical encounters.

Conclusion:

Study findings highlight that in older adults with various health experiences, cognitive and physical health status, and sociocultural backgrounds, medical decisions are influenced by a variety of values.

Practical implications:

Clinicians should take time to elicit, understand, and reassess the different types of values of older adults.

Keywords: Health priorities, decision-making, elders/elderly, ethnic groups

1. Introduction

Patient values are influenced by multiple factors, including personal health beliefs, religiosity, race/ethnicity, social and family customs, and life-long experiences [1–3]. Soliciting and incorporating patient values and preferences in healthcare decisions are key components of patient-centered care [4]. Eliciting patient values promotes shared decision-making (SDM) between patients and clinicians and improves patient understanding, satisfaction, autonomy, and trust [5, 6].

Having a clinician who understands their patients’ values is one characteristic of optimal quality care for patients facing frailty [7]. Many older adults, including those with cognitive impairment, want to be involved in healthcare decision-making [8–10]. Yet, the process of decision-making with older adults frequently fails to focus on individual needs and preferences [9, 11–13]. Understanding the values that affect healthcare decisions is particularly important in aging populations, given the frequency with which older adults face medical decisions and challenges such as cognitive and functional decline and multi-morbidities. Soliciting older adults’ values plays an essential role in decision-making, particularly when competing risks and benefits are present or no best option is available [14]. Further, values can change and are impacted by changes in life priorities, disease stages, or external support [3]. Having older adults express their values when relatives are present can also help caregivers make patient-centered surrogate decisions if required in the future [15].

We aimed to identify the values that diverse older adults incorporate in medical decision-making, including older adults from different cultural backgrounds with and without mild cognitive impairment. We also aimed to investigate if reported values aligned with a published taxonomy of patient values at the point of care [3]. The ultimate goal was to understand the types of values that commonly influence older adults’ medical decision-making in order to guide clinical encounters by improving value solicitation, SDM, and potentially decisions made by surrogates on behalf of older adults.

2. Methods

2.1. Design

Focus groups were conducted to explore the values that older adults incorporate into medical decision-making. Focus groups were used to build synergy in expressed values, prompting participants to explore individual and shared perspectives while listening to the views of others. Identified themes were organized according to the draft taxonomy of patient values [3]. University of Florida (UF) (201802275) and Mount Sinai Medical Center (15–29-H-06) IRBs approved study conduct. The study used a waiver of documentation of informed consent. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research [16] are depicted in Supplemental file 1.

2.2. Conceptual Framework

The study used a taxonomy of patient values at the point of care published shortly before study design and funding as a framework [3]. The taxonomy outlines four categories of patient values impacting decision-making, with values reflecting “unique preferences, concerns, and expectations that each patient brings to a clinical encounter” [17]. While some research makes no distinction between values and preferences [18], for this study, values were conceptualized as patient views/characteristics influencing decision-making. This is distinct from preferences, where an individual voices a greater liking for one option over alternatives [19]. Global values reflect life priorities that impact all decisions, such as religious beliefs. Global values can also represent value traits, such as risk aversion or a desire to try the “new thing”. Decisional values are those most commonly discussed in SDM and involve values tied to diagnostic or therapeutic options such as efficacy, toxicity, quality of life, and cost. Situational values reflect context-specific factors that influence a decision differently now than in the past or future, such as an upcoming event (e.g. a wedding). External values reflect a patient’s choice to consider others’ values and preferences when making a decision, an approach that may be personal or cultural [3].

2.3. Population

Individuals were recruited from the 1Florida Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (ADRC) and from a behavioral intervention program for persons with mild cognitive impairment, called Physical Exercise And Cognitive Engagement Outcomes For Mild Neurocognitive Disorder (PEACEOFMND) (convenience sampling) [20]. Four distinct populations were recruited to form the following groups: 1) cognitively normal Hispanics, 2) Hispanics with mild cognitive impairment, 3) cognitively normal non-Hispanics, and 4) non-Hispanics with mild cognitive impairment. Self-reported ethnicity/race was used to identify potential participants and assign them to groups. All four groups were recruited through the 1Florida ADRC. Only non-Hispanics were recruited from PEACEOFMND. Cognitive status was based the parent study’s criteria. For PEACEOFMND, participants with mild cognitive impairment had a Clinical Dementia Rating [21] scale score ≤0.5 and Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status for Memory (TICS-M) [22] score ≥25; normal cognitive status required a TICS-M score ≥32 [20]. For 1Florida ADRC participants, mild cognitive impairment or cognitively normal assignment was made by a clinician or consensus panel following the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center protocol [23].

2.4. Recruitment

PEACEOFMND and 1Florida ADRC research personnel identified and contacted active participants via telephone. Interested individuals were able to ask questions during the call, later via telephone or email, and at focus groups prior to study activities. The informed consent document was available in English and Spanish. Participants verbally agreed to participate prior to focus group questions and recording.

2.5. Data collection

Investigators (MJA, AMK) drafted the semi-structured focus group guide. It was revised based on suggestions from neuropsychologists and Spanish-fluent investigators who interact heavily with older adults. The guide was pilot-tested with English and Spanish-speaking psychology doctoral students prior to finalization (Supplemental file 2). A bilingual Latina clinical psychology doctoral student (AMK) interested in cultural and patient-centered research moderated all focus groups. She received mentorship from a neurologist with qualitative research experience (MJA) focusing on patient engagement, communication, and SDM. A research assistant (AR) provided on-site assistance and was present for the focus groups but did not contribute to the discussion. AMK and AR did not previously interact with participants.

Focus groups took place in private conference rooms at the 1Florida ADRC site in Miami, Florida and at a UF-affiliated senior-living facility in Gainesville, Florida. After an introduction of the moderator and study goals, focus groups started with free discussion to explore values impacting participants’ medical decision-making. Conversations took place predominantly in Spanish and English for Hispanic and non-Hispanic groups, respectively. After free discussion, the moderator presented a vignette describing a common medical decision to stimulate additional discussion (Supplemental file 2). Finally, the moderator presented the types of taxonomy values to generate further discussion about value types affecting decision-making. A whiteboard was used to capture key terms and concepts provided by participants, allowing for visual cues to facilitate discussion. Interviews were audio recorded with participant knowledge. Participants received $25 gift cards at study conclusion.

2.6. Analysis

A professional service transcribed the discussions verbatim and translated Spanish discussions to English. Participant checking was not performed. Investigators used Microsoft Word® tables and a qualitative descriptive approach [24] to identify and organize themes. MJA and AMK independently double coded the first full transcript to develop a codebook using content analysis (open coding). Emerging themes were compared and discussed to reach consensus. AMK analyzed remaining transcripts using a constant comparative technique to identify all instances of the coding framework, identify items not corresponding to initial framework themes, and expand or merge thematic codes (axial coding). This was iteratively reviewed by MJA and consensus was achieved on themes, subthemes, and codebook revisions. Co-investigators gave feedback after initial analysis. After axial coding, investigators jointly identified themes that matched taxonomy categories and assessed whether certain themes expanded the value types or were not well-captured by the existing taxonomy.

Theme saturation for the overall study population was assessed by investigators during focus group conduct and again during analysis. Investigators did not plan for or assess theme saturation for individual subgroups. The aim of the current analysis was to understand values that diverse older adults use for medical decision-making, not between-group differences.

3. Results

3.1. Sample characteristics

Forty-nine individuals participated. Mean age was 72.6 (SD=6.9); 63% of participants were female (Table 1). Six focus groups were conducted at the ADRC site (2 Hispanic and 1 non-Hispanic with mild cognitive impairment, 2 Hispanic and 1 non-Hispanic cognitively normal) and two were conducted at the UF site (1 non-Hispanic with mild cognitive impairment, 1 cognitively normal-non-Hispanic). On average, six people participated in each group (range: 4–11). Focus groups were conducted October 2018-May 2019. Mean discussion duration was 54 minutes. The moderator noted that cognitively impaired individuals needed more prompting and help to stay on track, but all groups were able to discuss proposed topics. Participants confirmed taxonomy values but expanded on the values included in each category.

Table 1.

Participant demographics

| Hispanic | Non-Hispanic | Total (n = 49) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||

| CN (n = 10) | MCI (n = 15) | CN (n = 14) | MCI (n = 10) | ||

| Female, n (%) | 7 (70%) | 9 (60%) | 9 (64%) | 6 (60%) | 31 (63%) |

| Age (mean, SD) | 70.09 (7.08) | 73.04 (6.85) | 72.8 (7.13) | 74.04 (5.78) | 72.57 (6.91) |

| Edu (mean, SD) | 14.7 (2.75) | 14.9 (3.55) | 16.57 (2.71) | 15.5 (2.64) | 15.47 (2.99) |

Edu: Years of education; CN: Cognitively Normal; MCI: Mild Cognitive Impairment

3.2. Values corresponding to taxonomy

3.2.1. Global:

Participants reported that characteristic/personality traits, caregiver roles, preventative care, quality of life, and thinking about the future were global values impacting how they approached medical decisions (Table 2). Multiple participants referenced approaching decisions with optimism, including expecting positive outcomes and having faith in treatment efficacy. Several voiced religious beliefs impacting their approach to medical decision-making, although select individuals dissented:

Table 2.

Global values

| Theme | Exemplar Quotes |

|---|---|

| Religion/faith in God | And have faith in God. He’s the only one able to help us, right? (H-MCI-7) Well, my religion. . . is a global value for me. . . Infant stem-cells … if they found a cure but they killed the infants to do it, I just can’t imagine that . . . that’s a global value where those two things would so contradict each other that that, to me, is just unthinkable. . . You just can’t do anything that’s against what I believe like that. I just couldn’t. (NH-CN-17) |

| Familial responsibility | I was thinking of my daughters. . .So I didn’t think twice. In fact, I didn’t even talk about it with anyone. . . (H-CN-2) |

| Thinking about the future | Well, there is the philosophical attitude that you have towards life. That’s very important (H-CN-10) ... I think to let them know whether or not we want to be kept on life support and how long it would need to be. I mean, that would be something I think that you should talk over with your family . . . (NH-MCI-22) |

| Quality of life | If I have to sit in a wheelchair for the rest of my life, that’s better than the alternative of having no ability to interact meaningfully with other people (NH-MCI-21) Imagine you’re 65 and you’re still very young, but you’re having a horrible quality of life. . . sometimes you have to value the quality of life versus how many more years you’re going to live. . . Quality of life is very important to me. (H-CN-3) |

| Prevention-oriented | . . . I tend to want to focus on prevention as much as possible, things that will help prevent something from getting worse . . . (NH-CN-16) |

| Avoid undue harm | I suppose my global values would be - I think the only one that I sort of - “First, do no harm,” and maybe “Simple is better than complex.” (NH-CN-18) |

| Personality traits | So, character is something very ... is what will influence the most what decision you make and how you make it. (H-CN-11) I think that impacts the decision, I mean, the character you have, the way you are, how you see things, that is fundamental. (H-CN-13) Subtheme: Being Optimistic I have the same…ah…ideology... I always think, “I will do very well.” “I won’t have problems here”… I always try to have a positive attitude; it’ll be fine . . . I mean, I’m always very positive. (H-CN-5) I’m very positive, I believe in the power of thinking positively (H-MCI-6) Subtheme: Procrastinating I just put if off until I can’t put it off anymore (NH-CN-2) |

NH: Non-Hispanic, H: Hispanic, MCI: Mild cognitive impairment, CN: Cognitively normal

There are people who have very strong religious convictions. . . but I do not agree with that. (H-cognitively normal-11)

3.2.2. Decisional:

Participants reported decisional values including one’s personal and family medical history, how the decision (e.g. medication) might affect their ability to do their job, whether the treatment’s mechanism of action was plausible, potential side effects, and cost concerns (Table 3). Multiple participants described the importance of making decisions with balance. Participants also discussed the importance of weighing the different values and priorities involved in a decision, such as pain versus having a colostomy bag or whether in chemotherapy, “the cure is worse than the disease” (Table 3). Sometimes participants felt like they did not have much of a decision, either because there was only one good choice or no good options existed.

Table 3.

Themes expressed related to decisional values

| Theme | Exemplar Quotes |

|---|---|

| Side effects | If I read up on the side effects of it- I would see if maybe I could manage with an alternative drug, you know? (NH-MCI-11) Yeah, but if you were to sit down and read the side effects you would never take the medication, you would shoot yourself first, you know? (NH-MCI-10) and I began to read and after about a year of taking that medicine, how bad these medicines were…And I was the one who educated myself about it…and I stopped taking the medicine, I did it on my own, and I know it’s not the best thing, but I had already read enough to be sure I had to stop taking the medicine. (H-MCI-21) |

| Regarding medications | Well, I would go along with the brand name because you don’t know if that other drug, even though it would’ve been approved by the FDA. . .and I would ask my doctor obviously if I really needed that drug because it was a question of if I had a serious illness, whether it would be – this other drug would work. (NH-MCI-10) |

| Costs | I’m also interested in how to make a medical decision about the cost. (H-MCI-19) You can go to someone who charges you less (H-MCI-18) Then money issues too, because if it’s – if something’s going to be very expensive, and that would mean, “Well, how am I going to eat?” And many people go without proper healthcare because of the cost issue. (NH-CN-5) |

| Have to experience the situation to know what decision you would make | You know, I think that’s hard to answer unless you have the experience . . .I don’t think you can say, “I would do this or that” until you’re there and you have to make a decision (NH-MCI-24) |

| Making a decision with balance |

Subtheme: Decisions driven by health status, treatment options, risks, expectations, and side effects That’s the risk evaluation. I mean, what your expectation would be and probabilities and so forth and just making a decision. (NH-MCI-23) Subtheme: Deciding for/against treatment I mean, if they tell me I need chemotherapy, I say no. The only thing they can give us is artificial respiration, mouth to mouth, that’s all...(H-MCI-15) Subtheme: Cure or treatment worse than disease/illness Well, if the cure’s worse than the – sickness then I would – probably decide not to take it, not to take the cure. (H-MCI-8) |

| Mechanism of action of treatment is plausible | You just like to have a logical reason why it’s working, you know? (NH-CN-18) |

NH: Non-Hispanic, H: Hispanic, MCI: Mild cognitive impairment, CN: Cognitively normal

3.2.3. External:

Many participants described taking family members’ advice because of their long-standing relationship (e.g. spouses) or the family member’s honesty or medical experience (Table 4). Valuing the physician’s recommendation was an external value that guided many participants’ medical decision-making. A few participants expressed valuing the opinions of family members and physicians, but emphasized they were the ones making the final decision. Participants also described making decisions in order to benefit their families more than themselves, something that overlapped with global values (Table 2).

Table 4.

Themes expressed related to external values

| Theme | Exemplar Quotes |

|---|---|

| Taking advice of others |

Subtheme: Family’s advice My son’s – works here as a doctor. . . I just listen and I just do what I think is best for me. (NH-MCI-13) … now my current wife, she’s a retired physician,. . . so those things that I don’t really understand, she can interpret for me. (NH-MCI-20) I pay attention to her, after so many years of marriage, you have to learn to live together. And part of living together is accepting what they ask of me, and I know it’s for the sake of my health (H-CN-4) Subtheme: Clinician’s advice So, then I decided to come... here to the hospital which the doctor recommended me. So yeah, he’s been the one in charge. . .. (H-MCI-8) . . .but I keep up because I am aware of it and I do my...my...my...what the doctor tells me. (H-MCI-19). . . .if you have confidence in your physician, I think you’re - at least my general standpoint is I’m pretty much going to try what he prescribes. (NH-CN-15) |

| Considering others’ opinions and values alongside one’s personal values | When you have children, you usually consult at our age, even if you are the one who decides. (H-CN-11) |

| Making decisions out of concern for family | I think that this way of thinking that we all agree is very typical of our generation. Because the previous generation, our parents’ generation thought, I don’t worry, that’s my children’s thing, let them take care of it. Our generation is much more practical and we think more of those who are left behind. It’s an interesting difference that I find. (H-CN-3) |

NH: Non-Hispanic, H: Hispanic, MCI: Mild cognitive impairment, CN: Cognitively normal

3.2.4. Situational:

Situational was the taxonomy category mentioned least by participants. Few participants endorsed situational values such as delaying treatments or procedures until after a family wedding or election year.

. . . once I had a colonoscopy, and it was about fifteen days before my daughter got married, and I changed the date... I thought, well, nothing happens ever, but what if something happens and I mess up my daughter’s wedding? (H-cognitively normal-11)

… is there an election coming up? Do I need to put this particular procedure off until after November 8th… (NH-cognitively normal-3)

3.3. New emerging themes

3.3.1. Changing values over time:

Participants noted that values affecting medical decision-making were not constant. Experiences affecting their priorities included growing older in general, experiencing worsening health, having near-death experiences, and watching friends die. Many voiced thinking about death; reflections varied from death being an inevitable part of life to choosing how to die. Participants described worsening health or new diagnoses prompting them to make decisions about life changes and medications. Some voiced the importance of tests because they have reached a certain age, while others voiced they have to pick what symptoms are worth pursuing or should be considered normal as they age.

. . . is this something I want to pursue, or is this something that I don’t feel like pursuing… if you’re 50, you might feel a little differently about that. Maybe you’ll pursue that. At 70 or 80, you start making those decisions, because frankly, everything hurts, and you just - you’ve got to help your doctor along. Otherwise, you can be busy at tests all day long every day (NH-cognitively normal-18)

3.3.2. Preferences for the decision-making process:

Participants noted preferences relevant to value solicitation and the decision-making process. Preferences pertained to self (autonomy, empowerment), the clinician (compassion, professionalism, responsiveness, personal characteristics), the patient-clinician interaction partnership, and healthcare in general (Table 5). Participants described the advantages of knowing oneself, having support from others, self-educating, and making informed decisions. Participants voiced the importance of finding the right doctor and having a good relationship, versus challenges relating to distrusting their physician. Participants described a willingness to change doctors if dissatisfied and the value of getting second opinions. Participants valued physicians who had good bedside manners and communication skills, were receptive, and discussed alternative approaches. Participants preferred clinicians who were caring and made them feel valued and unique. Negative experiences related to clinicians focused on technology during medical visits (e.g. limited eye contact due to clinicians staring at computer screens) and poor communication between themselves and clinicians and between different medical team members. Some participants believed that knowing their physicians’ credentials and years of experience was important. Opinions differed as to whether a physician’s personal attributes (e.g., sex, gender, or heritage), beliefs, or lifestyle (ability to separate personal from professional life) should impact whether to stay with that physician. Some participants preferred older doctors who could relate better to their own experiences; others preferred younger doctors who would be available long-term. At the systems level, some participants described distrust of the medical system and pharmaceutical companies. Limited insurance coverage and online misinformation also hampered care.

Table 5.

Preferences related to value solicitation and decision-making

| Theme | Subthemes |

|---|---|

| Patient autonomy | Knowing oneself, self-advocating, self-educating, seeking support from others (family, support groups) |

| Patient empowerment | Being able to make informed decisions, willingness to change doctors, getting a second opinion |

| Clinician compassion | Being sensitive, personal |

| Clinician professionalism | Knowing the clinician’s credentials, considering the clinician’s healthcare system affiliation, clinician’s years of experience |

| Clinician’s responsiveness | Good bedside manner and communication skills, receptive, attentive, taking time with patient, discussing alternative approaches, being able to schedule an appointment without difficulty |

| Clinician personal characteristics | Demographics (sex, gender, heritage), beliefs, and lifestyle (ability to separate personal from professional life), age |

| Interaction partnership | Important to find the right doctor, having a good relationship with one’s doctor, treating, considering the patient as a person/uniquely, eye contact |

| Healthcare system | Integrated care settings (academic-medical center) |

3.4. Taxonomy feedback

Most participants felt that their values were adequately represented in the taxonomy. A few dissenting voices expressed that each person’s point of view was not captured. Some participants described that values represent a combination of factors, making it difficult to confine within specific categories. One theme not fully captured in the framework was quality of life. Although the original taxonomy included quality of life as a decisional value, many participants described quality of life as an overarching goal.

4. Discussion and Conclusion

4.1. Discussion

This study investigated the types of values influencing medical decision-making among a diverse sample of older adults. Participants expressed a wide range of values relating to individual factors, familial/cultural beliefs and expectations, and particular life experiences. When making medical decisions, older adults voiced the importance of social and decisional support from relatives and clinicians. Participants highlighted that medical decisions are unique; it is usually a combination of values and factors guiding decisions, rather than any one value at one given time. It was evident that values change throughout life course.

4.1.1. Comparison to published taxonomy

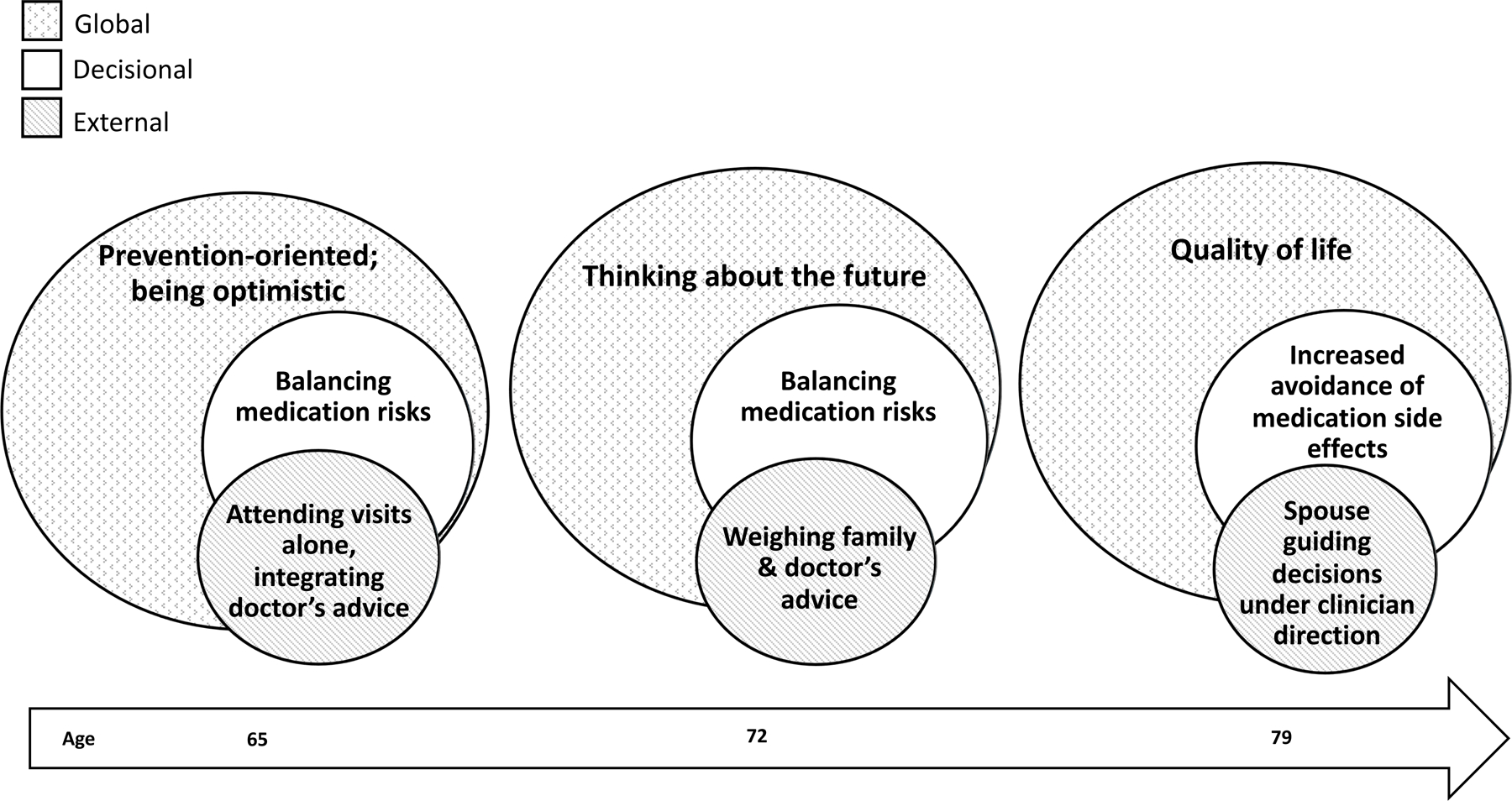

Focus groups themes generally supported the value taxonomy while expanding on examples originally considered within categories [3]. Participants’ global values encompassed those in the taxonomy (e.g. religious beliefs, personality) but also included themes reflecting older adults’ experiences and considerations (e.g. prevention, considering future/death). Decisional values included making decisions based off therapeutic options and outcomes, with many voicing concerns with medications’ side effects and efficacy. Further, decisional values captured needing to “make decisions with balance”, which was often associated with improving health/increasing longevity and avoiding age-related risks and/or complications. External values reflected the bidirectional influence between older adults and their relatives, but also desiring and relying on physician guidance, an external value not specifically included in taxonomy examples. Situational values were rarely described. Transient situations impacting medical decision-making may be less common among older adults, particularly for those navigating comorbidities and balancing multiple treatment regimens and side effects. These findings inform additional examples for existing taxonomy categories but also highlight that some values, particularly quality of life, may overlap multiple value categories. Throughout discussions of global, decisional, and external values, themes demonstrated that aging shapes preferences, values, and medical decision-making, reflecting values changing over time (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Example of how values change over time throughout late life.

While individual experiences and values varied, participants in this study suggested values change over time. For the exemplar individual presented in Figure 1, the overall focus shifted from disease prevention to an overarching focus on quality of life (i.e., global values). Based on interviews, when an individual is in earlier disease stages, they prioritize medication changes that balance side effects and treatment efficacy. Later in life, an individual may prioritize avoiding medication side effects when evaluating therapeutic options (i.e., decisional values). Similarly, many participants described valuing independence in medical decision making but desiring more family and clinician involvement in decision making encounters over time (i.e. external values).

These findings are consistent with approaches to values and preferences published since the taxonomy used for this study and subsequent to study execution [19, 25]. For example, a descriptive study using published taxonomies (including the one guiding the current study) and video-recordings of primary care visits found that within clinical encounters, patients mentioned life goals, philosophies, and broader contextual/sociocultural values (global values), as well as treatment-specific values (decisional values) [19]. External values were not mentioned, but these might not be explicitly stated in discussions with clinicians.

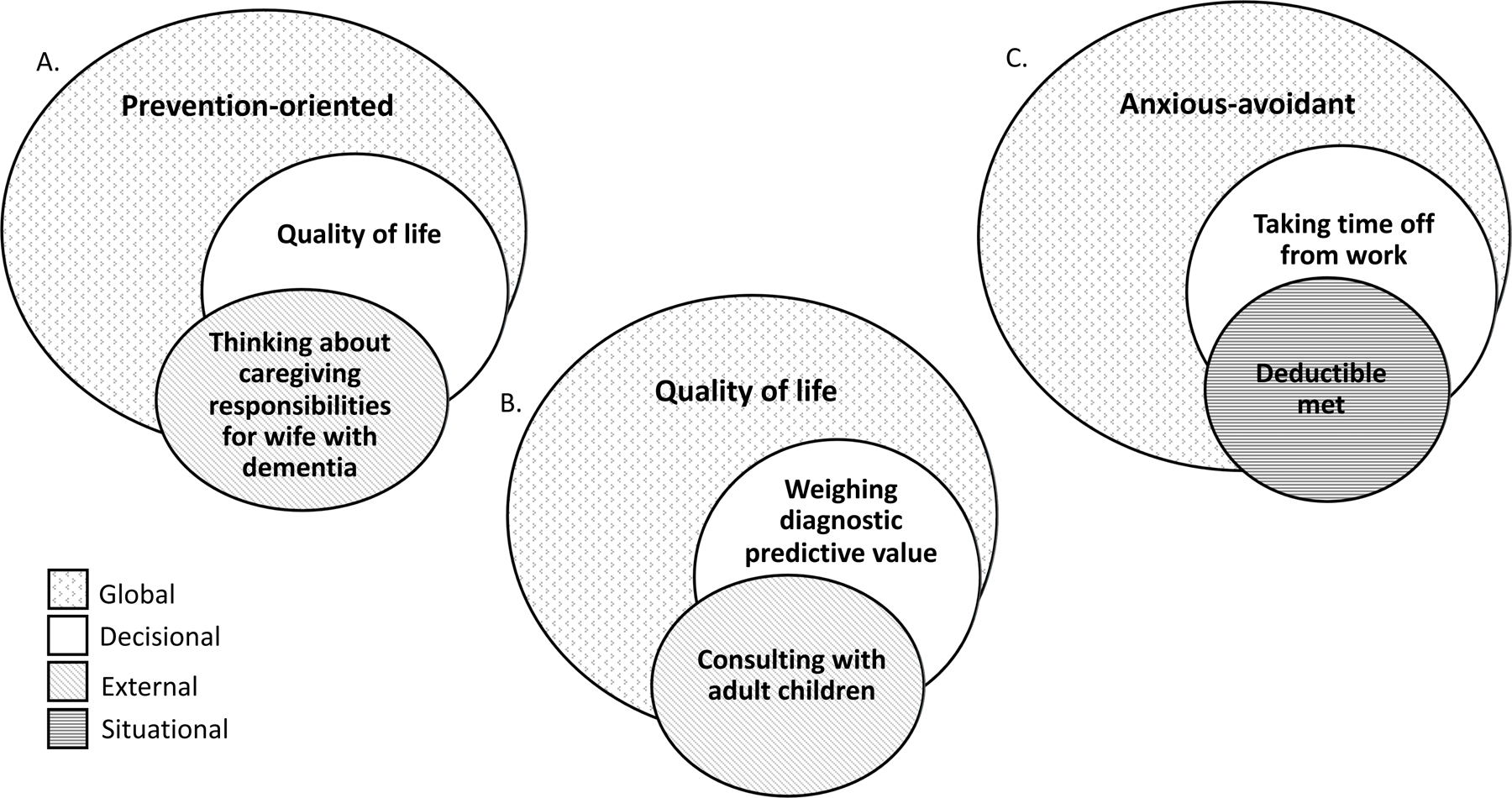

4.1.2. Emphasis on individualized approach

In line with existing research conceptualizing patient values and preferences [19, 25], the types of values expressed in our study were distinct yet interconnected. Participants expressed that values are specific to each individual and the decision-making context, making it difficult to categorize certain values into specific value types (e.g. quality of life) or approach older adults’ health concerns ubiquitously (Fig. 2). Prior studies also show that older adults want to be involved in their healthcare decisions and be treated uniquely, as a person, rather than a health problem [18].

Figure 2: Intersection of values across different individuals.

Person A’s global value is taking a prevention-oriented approach in all decisions. When faced with their doctor’s recommendation to undergo a routine screening procedure, Person A evaluates relevant risks, but values quality of life in the long run (i.e., decisional value) resulting from potentially identifying cancer early, while also balancing competing demands as a caregiver (i.e., external value).

Person B’s global value is prioritizing quality of life. When deciding to proceed with a screening procedure, they weigh the short-term deficit of quality of life associated with procedure (e.g. colonoscopy preparation), but value the high predictive value of the procedure (i.e., decisional value). They value their family’s opinion, so they seek advice before making a decision (e.g., external value).

Person C is anxious-avoidant for all non-emergency procedures (e.g., global value/characteristic). When their doctor recommends a screening exam, Person C further hesitates because they anticipate difficulties requesting time off from work (i.e., decisional value). Although both global and decisional values reflect hesitancy to undergo the diagnostic exam, Person C ultimately decides to proceed after realizing they’ve met their deductible (i.e., situational value).

4.1.3. Global values & changing over time

Prior studies identified life philosophies, socio-cultural background, and personal history as a category of patient values, [1, 18, 19] similar to global values represented in the taxonomy used in the current study. Specifically, current participants echoed the sentiments of avoiding suffering, not being a burden, religion, family obligations, and fatalism [1, 18, 19, 26, 27]. Participants reflected that values changed over time as a function of life experiences, health complications, and growing older in general. Although these experiences are not unique to older adults, older adults are at greater risk of experiencing the impact of common age-related changes (e.g., physical state changes, health complications, worsening chronic conditions) [28]. For several participants, values in life previously focused on extending life expectancy and shifted to prioritizing quality of life in older age. Longitudinal studies on how patient preferences change are lacking and our findings, along with others [28, 29], illustrate the need for reassessment of values during late life. Previous research offers a structured outline and phrasing to help solicit values pertaining to patient’s life priorities and desired quality of life [19, 25, 30].

4.1.4. Decisional values

Decisions with trade-offs can be challenging for older adults who often balance quality and quantity of life. Prior studies focused on cost-benefit analyses in the context of end-of-life preferences or life-threatening illness [31]. From a societal perspective, these topics may be challenging; some clinicians report difficulty communicating prognoses to older adults and concerns for patients’ reaction [32]. However, participants in our study openly discussed prioritizing quality of life, advanced care planning, and thinking about death and the future. When patients balance quality of life vs. increasing life expectancy, clinicians should help patients achieve their goals while disrupting quality of life as little as possible [33]. In these situations, clinicians should seek to understand why a patient may be prioritizing certain symptoms over others (Fig. 2). Knowing the patient’s values and preferences provides the context for understanding how a patient’s decision translates to daily functioning or their involvement in valued activities [34]. Pharmaceutical research with older adult populations should include functional and quality of life outcomes in addition to traditional efficacy measures. Additionally, more research is needed on how to best engage older adults when facing choices with multiple treatment options, life-long implications, and/or uncertain cost-benefit considerations [8, 35].

4.1.5. External values

Our findings support prior studies suggesting that older adults want their physicians’ input when making decisions, [8, 18] but that several contingencies are associated with taking their doctor’s recommendations. For example, trusting and feeling comfortable with the clinician was often voiced as being necessary to follow a doctor’s recommendation. These findings suggest that older adults value the perspective of clinicians but also value the quality of the relationship between them and the clinician [8]. Many participants in our study rejected taking a passive role in decision-making and stated that the “doctor knows best” mentality has diminished among their generation [8]. Our findings support that family members are often involved in healthcare decision of older adults. Participants described the involvement of adult children, spouses, and other relatives, particularly of those with healthcare backgrounds. More novel to this study is that several participants described serving in a caregiver role as an external value. This reflects the diverse health statuses and experiences of participants, contrasting prior studies focusing on older adults with life-threatening or chronic conditions [1, 31].

4.1.6. Preferences for the decision-making process

Although this study did not systematically assess preferences for the decision-making process, participants described experiences that promoted the integration of values in decision-making and conversely, experiences that interfered. Consistent with prior findings, participants emphasized preferring empathic, caring, and compassionate clinicians [18, 36]. Novel to our study was the identification of preferences pertaining to healthcare in general and those related to the clinician’s personal attributes. Reported barriers to the decision-making process (and by extension, incorporation of values into this process) included poor communication (e.g. using terminology that the patient doesn’t understand), body language (e.g. lack of eye contact), and interpersonal skills (e.g. hurried, robotic, not listening, and treating patients as numbers), also reported in other research [11, 36, 37]. Participants echoed previously reported concerns navigating healthcare with multiple physicians, concerns regarding insurance companies and healthcare systems, and the belief that doctors are motivated by financial gains [11, 30, 37].

4.1.7. Limitations

Study results may not be applicable to other geriatric populations, given that participants do not reflect the diversity found in the general population. We did not collect information regarding comorbidities or patient health status, beyond cognitive status. Participants were from one geographic region and were highly engaged and able to participate in research. All participants were exposed to a large medical/university system through research participation, with some receiving clinical care in this setting. Values and preferences relating to healthcare setting (e.g. convenient to go to one place for healthcare, obtaining care from a training hospital) and clinician credentials (e.g. considering healthcare system affiliation) may not generalize considering our sample’s educational attainment. Previous data suggests that higher education is associated with preferences for being actively involved in healthcare encounters [8]. The study was not designed to compare themes between different focus groups, as such, saturation of themes was likely not reached for any given subgroup. Despite limitations in generalizability, this study adds to the existing body of literature by emphasizing the heterogeneity of values held by a diverse sample in regard to various health experiences, cognitive and physical health status, and sociocultural backgrounds. Prior studies of older adult patient preferences often focus on a specific condition (e.g. diabetes or other life-threatening/chronic illnesses) or are restricted to a specific decision-making context (e.g. deprescribing) [1, 31, 37]. Unlike our study, ability to speak English is commonly an inclusionary criteria across qualitative studies in the U.S. Additionally, few studies have facilitated free discussion of values while also using a taxonomy to assess results.

4.2. Conclusion

This study emphasizes that older adults incorporate diverse values in medical decision-making that are informed by past experiences, age, and individual characteristics. Values are multifaceted, change with aging, and include considerations relating to quality of life, familial roles and influences, and balancing risks/benefits. Participants valued receiving advice from their clinicians and/or family. This study highlights the need for clinicians to query and respect individual beliefs and identify how social/cultural roles and external influences may impact patient decision-making. Participants emphasized the need for patient-centered approaches to engaging, eliciting and incorporating older adults’ values and priorities when making medical decisions, many of which focused on strong clinician-patient relationships and communication skills.

4.3. Practice Implications

Irrespective of care settings and specific decisions, clinicians should take time to elicit and understand the values older adults incorporate in decision-making. Some values described by current study participants, such as desiring input from their family and/or physicians, were not identified by a prior study reviewing transcripts of patient-clinician discussions occurring during routine clinical care [19]. Thus, clinicians may need to intentionally ask for patients to voice their specific values as part of clinical visits. Clinicians should reassess values over time, considering that values are likely to change during aging and throughout unique life circumstances. Given that older adults value their families’ input in decisions and that families may be needed for surrogate roles in cases of advancing cognitive impairment, clinicians should involve family members in value discussions when desired by their patients.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Older adults incorporate unique and multifaceted values in health decisions.

Values that influence medical decisions change with aging.

Values include consideration of familial roles and decisional support.

Older adults value quality of life and balance risks versus benefits.

Funding:

This study was funded through a pilot grant from the 1Florida ADRC (P50AG047266, P30AG047266).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest:

Andrea M. Kurasz: None

Glenn E. Smith: Smith receives research support from the 1Florida ADRC (P30AG047266) and the Florida Department of Health Ed & Ethel Moore research program.

Rosie E. Curiel: None

Warren W. Baker: None

Raquel C. Behar: None

Alexandra Ramirez: None

M.J. Armstrong: M.J. Armstrong receives grant support from the NIA (R01AG068128, P30AG047266), the Florida Department of Health (grant 20A08), and as PI of a Lewy Body Dementia Association Research Center of Excellence site. She has previously received grant support from ARHQ (K08HS24159) and NIA (P50AG047266) and compensation from the American Academy of Neurology for work as an evidence-based medicine methodology consultant. She is on the level of evidence editorial board for Neurology® and related publications (uncompensated) and receives publishing royalties for Parkinson’s Disease: Improving Patient Care (Oxford University Press, 2014).

References

- [1].Lee YK, Low WY, Ng CJ, Exploring patient values in medical decision making: a qualitative study, PLoS One 8(11) (2013) e80051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Hajjaj FM, Salek MS, Basra MK, Finlay AY, Non-clinical influences on clinical decision-making: a major challenge to evidence-based practice, J R Soc Med 103(5) (2010) 178–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Armstrong MJ, Mullins CD, Value Assessment at the Point of Care: Incorporating Patient Values throughout Care Delivery and a Draft Taxonomy of Patient Values, Value Health 20(2) (2017) 292–295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Barry MJ, Edgman-Levitan S, Shared decision making--pinnacle of patient-centered care, N Engl J Med 366(9) (2012) 780–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Bunn F, Goodman C, Russell B, Wilson P, Manthorpe J, Rait G, Hodkinson I, Durand M-A, Supporting shared decision making for older people with multiple health and social care needs: a realist synthesis, BMC geriatrics 18(1) (2018) 165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Shay LA, Lafata JE, Where is the evidence? A systematic review of shared decision making and patient outcomes, Med Decis Making 35(1) (2015) 114–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Cassel CK, Policy for an aging society: a review of systems, JAMA 302(24) (2009) 2701–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Bastiaens H, Van Royen P, Pavlic DR, Raposo V, Baker R, Older people’s preferences for involvement in their own care: a qualitative study in primary health care in 11 European countries, Patient Educ Couns 68(1) (2007) 33–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Miller LM, Whitlatch CJ, Lyons KS, Shared decision-making in dementia: a review of patient and family carer involvement, Dementia 15(5) (2016) 1141–1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Hamann J, Bronner K, Margull J, Mendel R, Diehl-Schmid J, Bühner M, Klein R, Schneider A, Kurz A, Perneczky R, Patient participation in medical and social decisions in Alzheimer’s disease, J Am Geriatr Soc 59(11) (2011) 2045–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Bynum JP, Barre L, Reed C, Passow H, Participation of very old adults in health care decisions, Med Decis Making 34(2) (2014) 216–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Kogan AC, Wilber K, Mosqueda L, Person-Centered Care for Older Adults with Chronic Conditions and Functional Impairment: A Systematic Literature Review, J Am Geriatr Soc 64(1) (2016) e1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Bogardus ST, Bradley EH, Williams CS, Maciejewski PK, van Doorn C, Inouye SK, Goals for the care of frail older adults: do caregivers and clinicians agree?, The American Journal of Medicine 110(2) (2001) 97–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Krahn M, Naglie G, The Next Step in Guideline Development: Incorporating Patient Preferences, JAMA 300(4) (2008) 436–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Butler M, Talley KMC, Burns R, Riley Z, Rothman A, Johnson P, Kane RA, Kane RL, Values of older adults related to primary and secondary prevention, Evidence Synthesis/Technology Assessment, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD, 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J, Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups, Int J Qual Health Care 19(6) (2007) 349–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Baker A, Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century, British Medical Journal Publishing Group 2001. [Google Scholar]

- [18].Bastemeijer CM, Voogt L, van Ewijk JP, Hazelzet JA, What do patient values and preferences mean? A taxonomy based on a systematic review of qualitative papers, Patient Educ Couns 100(5) (2017) 871–881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Rocque R, Chipenda Dansokho S, Grad R, Witteman HO, What Matters to Patients and Families: A Content and Process Framework for Clarifying Preferences, Concerns, and Values, Med Decis Making 40(6) (2020) 722–734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].De Wit L, O’Shea D, Chandler M, Bhaskar T, Tanner J, Vemuri P, Crook J, Morris M, Smith G, Physical exercise and cognitive engagement outcomes for mild neurocognitive disorder: a group-randomized pilot trial, Trials 19(1) (2018) 573–573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Morris JC, The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): current version and scoring rules, Neurology 43(11) (1993) 2412–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Welsh KA, Breitner JC, Magruder-Habib KM, Detection of dementia in the elderly using telephone screening of cognitive status, Neuropsychiatry, Neuropsychology, & Behavioral Neurology (1993). [Google Scholar]

- [23].Besser L, Kukull W, Knopman DS, Chui H, Galasko D, Weintraub S, Jicha G, Carlsson C, Burns J, Quinn J, Sweet RA, Rascovsky K, Teylan M, Beekly D, Thomas G, Bollenbeck M, Monsell S, Mock C, Zhou XH, Thomas N, Robichaud E, Dean M, Hubbard J, Jacka M, Schwabe-Fry K, Wu J, Phelps C, Morris JC, D.a.C.C.l.o.t.N.I.o.A.-f.U.S.A.s.D.C. Neuropsychology Work Group, Version 3 of the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center’s Uniform Data Set, Alzheimer disease and associated disorders 32(4) (2018) 351–358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Colorafi KJ, Evans B, Qualitative Descriptive Methods in Health Science Research, HERD 9(4) (2016) 16–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Vermunt NP, Harmsen M, Elwyn G, Westert GP, Burgers JS, Olde Rikkert MG, Faber MJ, A three-goal model for patients with multimorbidity: A qualitative approach, Health Expect 21(2) (2018) 528–538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Petrillo LA, McMahan RD, Tang V, Dohan D, Sudore RL, Older adult and surrogate perspectives on serious, difficult, and important medical decisions, Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 66(8) (2018) 1515–1523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Babulal GM, Quiroz YT, Albensi BC, Arenaza-Urquijo E, Astell AJ, Babiloni C, Bahar-Fuchs A, Bell J, Bowman GL, Brickman AM, Chetelat G, Ciro C, Cohen AD, Dilworth-Anderson P, Dodge HH, Dreux S, Edland S, Esbensen A, Evered L, Ewers M, Fargo KN, Fortea J, Gonzalez H, Gustafson DR, Head E, Hendrix JA, Hofer SM, Johnson LA, Jutten R, Kilborn K, Lanctot KL, Manly JJ, Martins RN, Mielke MM, Morris MC, Murray ME, Oh ES, Parra MA, Rissman RA, Roe CM, Santos OA, Scarmeas N, Schneider LS, Schupf N, Sikkes S, Snyder HM, Sohrabi HR, Stern Y, Strydom A, Tang Y, Terrera GM, Teunissen C, Melo van Lent D, Weinborn M, Wesselman L, Wilcock DM, Zetterberg H, O’Bryant SE, International R Society to Advance Alzheimer’s, A.s.A. Treatment, Perspectives on ethnic and racial disparities in Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias: Update and areas of immediate need, Alzheimer’s & dementia : the journal of the Alzheimer’s Association 15(2) (2019) 292–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Gonzalez AG, Schmucker C, Nothacker J, Motschall E, Nguyen TS, Brueckle MS, Blom J, van den Akker M, Rottger K, Wegwarth O, Hoffmann T, Straus SE, Gerlach FM, Meerpohl JJ, Muth C, Health-related preferences of older patients with multimorbidity: an evidence map, BMJ open 9(12) (2019) e034485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Fried TR, Byers AL, Gallo WT, Van Ness PH, Towle VR, O’Leary JR, Dubin JA, Prospective Study of Health Status PREFERENCES and Changes in PREFERENCES Over Time in Older Adults, Archives of Internal Medicine 166(8) (2006) 890–895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Tinetti ME, Costello DM, Naik AD, Davenport C, Hernandez-Bigos K, Van Liew JR, Esterson J, Kiwak E, Dindo L, Outcome Goals and Health Care Preferences of Older Adults With Multiple Chronic Conditions, JAMA Netw Open 4(3) (2021) e211271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Naik AD, Martin LA, Moye J, Karel MJ, Health Values and Treatment Goals of Older, Multimorbid Adults Facing Life-Threatening Illness, J Am Geriatr Soc 64(3) (2016) 625–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Schoenborn NL, Bowman TL II, Cayea D, Pollack CE, Feeser S, Boyd C, Primary Care Practitioners’ Views on Incorporating Long-term Prognosis in the Care of Older Adults, JAMA Internal Medicine 176(5) (2016) 671–678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Hoffmann T, Jansen J, Glasziou P, The importance and challenges of shared decision making in older people with multimorbidity, PLoS Med 15(3) (2018) e1002530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Lim C, Berry ABL, Hirsch T, Hartzler AL, Wagner EH, Ludman E, Ralston JD, “It just seems outside my health”: How Patients with Chronic Conditions Perceive Communication Boundaries with Providers, DIS (Des Interact Syst Conf) 2016 (2016) 1172–1184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].A.G.S.E.P.o.t.C.o.O.A.w. Multimorbidity, Guiding Principles for the Care of Older Adults with Multimorbidity: An Approach for Clinicians, Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 60(10) (2012) E1–E25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Vieder JN, Krafchick MA, Kovach AC, Galluzzi KE, Physician-patient interaction: what do elders want?, J Am Osteopath Assoc 102(2) (2002) 73–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Belcher VN, Fried TR, Agostini JV, Tinetti ME, Views of older adults on patient participation in medication-related decision making, J Gen Intern Med 21(4) (2006) 298–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.