Abstract

In spring and fall 2020, most schools across the globe closed due to the ongoing threat of the COVID-19 pandemic. Online and remote learning (ORL) modalities were implemented to continue children’s education and development. Yet, the change in educational delivery increased parental responsibilities in cultivating their children. We examined the determinants related to students’ learning performance before and during the COVID-19 period in association with psychosocial behaviors (such as socialization, internalizing and externalizing behavior, and motivation) and other factors, including parents’ support received, the teaching modality, and access to digital resources. The current study included 80 parents of elementary and middle school children who completed an online survey. The results of the study indicated that more than double the normal time was spent by parents in supporting their children’s learning and development during the COVID-19 period. The factors of parental support and motivation were found the most effective contribution in the development of children’s positive emotions and learning attainment. It was indicated that academic performance, motivation to participate in learning, socialization, prosocial behavior, discipline, externalizing and internalizing behaviors decreased during the COVID-19 pandemic. Accordingly, teachers and educators should consider bridging or creating alternative performance recovery strategies and socioemotional development interventions for children and young adults.

Keywords: parental support, learning performance, socioemotional behavior, online and remote learning

Introduction

Since the first reported case of infection from the COVID-19 virus in Wuhan, China, the number of people contracting the virus has rapidly increased throughout the world. Accordingly, governments have implemented different strategies for controlling the disease through lockdowns, maintaining physical and social distancing, and using online learning as opposed to face-to-face learning for students. The COVID-19 virus has affected more than 190 countries and 1.57 billion students at all levels of education (United Nations, 2020). One outcome of these education-related changes for ∼90% of the student population (Giannini, 2020) is that many children and adolescents have experienced declines with their mental health and social skills as a result of isolation from peers and teachers in face-to-face settings (Gao et al., 2020; Lancker & Parolin, 2020). These negative outcomes hinder learning outcomes and physical growth (Lancker & Parolin, 2020) since socio-emotional development is closely connected with children’s externalizing and internalizing behavior that influences individual children’s academic performance (Campbell et al., 2016). This study seeks to examine the factors related to students’ learning performance before and during the COVID-19 period in association with psychosocial behaviors (such as socialization, internalizing and externalizing behavior, and motivation) and other factors, including parents’ support received, the teaching modality, and access to digital resources. The goal of this study is important to achieve because it explores the hidden factors connected with students’ learning performance and personal development before and during the COVID-19 period.

Outcomes Related to School Closures and Social Distancing

The association between school closures and a sudden shift to online modalities in the United States education system has impacted children's learning and development. The first recorded case of COVID-19 in the United States was on January 20, 2020, in the State of Washington, which was confirmed on January 22, 2020 (Harcourt et al., 2020). The effect of the nationwide spread of the COVID-19 virus was the state government issuance of temporary school closures for Washington State and New York mid-February 2020. Ohio, however, was the first state that decided to close its schools on a more long-term basis on March 12, 2020. Other states soon followed suit and announced statewide school closures (Education Week, 2020).

The school closure and social distancing during the COVID-19 pandemic impacted more than 55 million students nationwide by decreasing academic activities and limiting socialization with teachers and peers that support their mental, emotional, and social wellbeing (Garcia & Weiss, 2020). Another reality of the COVID-19 pandemic was the sudden first-time physical distancing teaching and learning practices. As with other changes, these changes can negatively influence children’s behavior. For instance, children suddenly lost access to in-person contacts and face-to-face learning environments, which negatively impacted their development of psychosocial and noncognitive skills such as empathy, self-control, social skills, creativeness, and so on (Garcia & Weiss, 2020). In addition, during the initial phase of the pandemic, many individuals experienced the loss of school meals, which increased parental burden as parents had to take extra measures to care for and educate their children.

Changes in Learning Modalities

The shift in the ORL modalities led to a decrease in potential learning competencies and development of the younger population (Lau and Lee, 2020; United Nations, 2020). For this study, the terms “online learning” and “remote learning” are used as an antonym for in-person learning. The pandemic forced schools to break the traditional teaching and learning strategies and continue to provide students access to education through an ORL environment. There are several issues with this learning modality that include potential negative impact on learners’ engagement level for learning, motivation, performance, and social moral development in their studies. For instance, an ORL modality provides less opportunities for interactions between teachers and students, which may increase confusion and lead towards frustration and demotivation of students (Dhawan, 2020). At the same time, one third of the world’s population does not have access to digital media and Internet infrastructures and thus are excluded from the learning opportunity provided only though remote learning (United Nations, 2020).

Although, there are different scientific discussions regarding the effectiveness of closing schools to control transmission of the disease, the impact of a school closure for a long period could be detrimental to the psychosocial development and academic performance of children and teenagers (Gassman-Pines et al., 2020; Golberstein et al., 2020; Lau & Lee, 2020). Physical distancing creates social isolation that can contribute to increases in mental health problems such as anxiety, stress, and depression (Leigh-Hunt et al., 2017), which directly impacts the learning performance of students.

Online Learning, Socioemotional Behavior, and Learning Performance

Access to Learning, Parental Support, and Learning Performance

The sudden transition to remote learning in the pandemic period creates challenges, especially in vulnerable communities (Kapasia et al., 2020). The decision to shut down schools directly impacted the face-to-face teaching learning modality, which forced parents to take more responsibility in their children’s learning and development. The ORL opportunity offered from schools especially affected poor children who had no Internet access and limited educational infrastructures at home (UN, 2020).

The ORL modality requires students to have access to supplementary materials such as computers and other digital devices. Similarly, young children need more parental support in online learning for their homework and assignments. Children from lower socio-economic status backgrounds are less likely to receive such parental support for their online learning (Andrew et al., 2020). Similarly, children from a higher economic status received more educational resources such as parents’ help in bringing books from libraries, parental support in technology for their learning as well as tutors and daycare centers (Jæger & Blaabæk, 2020). For instance, it was found that parents from higher economic status were checking out more learning materials from libraries to support their children’s learning. In this regard, the learning modality during the COVID-19 period emphasized the inequality in education (Jæger & Blaabæk, 2020). Hence, having little to no access to resources resulted in poor performance, which increased lower educational performance in future education and a higher risk for school dropout rates for children in poor households.

Research indicated that family characteristics such as income, occupation, and place of residence influences children’s learning (Eccles, 2005); however, in the COVID-19 environment, engagement in ORL is influenced by the access and adoption of technology and social interactions between teachers and peers that impact the students’ learning performance (Ewing & Cooper, 2021). Thus, in this study we will analyze the learning opportunities given to students at home, parental support, and children’s motivation level in virtual classrooms to understand children’s learning performance during the COVID-19 period, which will be measured through survey questionnaires answered by parents. Additionally, the characteristics of the ORL context is that learning consists of influencing factors that increase social interactions and increase parental support and children’s motivation during COVID-19 that are directly connected with children’s learning performance and personal development (Campbell et al., 2016). The focus of this study was to analyze parental support to measure children’s learning and development with comparative information before and after COVID-19 to predict the impact of COVID-19 in children’s learning and development in their lifespan development.

Socioemotional Behavior and Learning Performance

Students’ learning became heavily dependent on digital technology in the COVID-19 outbreak. The face-to-face discussions with peers and teachers through interactive daily classroom activities changed to an online pedagogy. ORL modality had various difficulties related to parents and students’ skills needed for the use of technology, the access to technology by students, supportive home environment, and technology infrastructure (i.e., access to computers, laptops, internet facilities, etc.). Development of socioemotional behavior is interconnected with environmental characteristics such as school-home environment, parental-teacher support, pedagogical approach, and interaction, and managing conflict and negativity (Campbell et al., 2016). In the COVID-19 context, when children experience negative problems, it leads to an increase in aggression, internalization and externalization behavior and impacts children’s developmental outcomes.

COVID-19 is known as a pandemic and most studies such as that of Li and Zhou’s (2021) have indicated that children exposed to pandemics experience the increment in externalizing and internalizing behaviors. It was stated that internalizing and externalizing problems significantly affect the elementary children’s learning attainment (Li & Zhou, 2021). The process of ORL modality proved to be challenging to parents and influenced their daily activities since they had to actively engage in their children’s learning. It led to psychosocial crisis related to stress, fear, anxiety, and depression with parents and students (Dhawan, 2020). Additionally, sitting in the same position for a long time while contributing to one-way online activities in COVID-19 demotivated students’ attention and caused them to feel bored during learning (Dhawan, 2020). While students interact freely in group settings with peers and teachers and actively participate in classes such as physical education during face-to-face learning, they usually sit in one position in online learning, even while participating in group discussions. Children’s externalizing and internalizing emotional competencies have been responsible for promoting school success, that might be reflected in the COVID-19 environment (Campbell et al., 2016).

Current Study

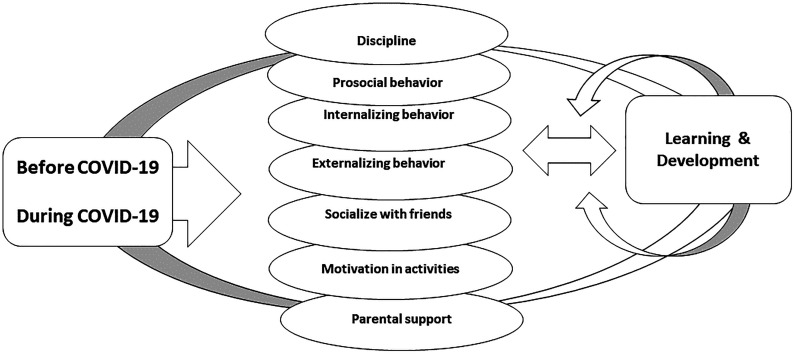

The main aim of this study is to examine the determinants related to students’ learning performance and personal development before and during the COVID-19 period in association with psychosocial behaviors (such as socialization, internalizing and externalizing behavior, and motivation) and other factors, such as parents’ support and students’ motivation in the teaching learning modality. This study examines parents’ thoughts on their children’s face-to-face learning before COVID-19 compared to the ORL modality implemented during COVID-19 to answer the following research questions (RQ1 and RQ2). This study was analyzed through parental views to examine parents’ involvement, motivation, socioemotional behavior of children during COVID-19. This study also analyzes the parental perspective to predict their children’s learning in the online modality and future lifespan trajectory (see Figure 1). Figure 1 illustrates the impact of the learning environment and socioemotional behavior displayed by children on children’s learning attainment and development. Based on the theoretical assumption of the presented model, the RQ1 and RQ2 were proposed for this study which will be elaborated further.

RQ1: What is the impact of online modality on students’ learning during COVID-19 and how is it influenced by parental support?

RQ2: Is there a difference in students’ socioemotional behaviors (such as socialization, internalizing and externalizing behavior, and motivation, etc.) before and during COVID-19?

Figure 1.

Impact of COVID-19 on children’s learning and socioemotional development.

Note. This model portrays how children’s learning and personal development is related to different variables listed above and it compares them before and during the COVID-19 period. Learning and development of children influences the different variables and vice versa, displaying a two-way relationship.

Method

Participants

This study included parents of elementary and middle school students. Parents were invited to complete online questionnaires. Participants were selected from different socio-economic and ethnic background groups from an area in the South-Central United States. The study included 80 participants. The average age of the participants was 42.06 (SD = 7.67) and 50% of the sample was female. Additionally, 30% of the participants were Asian-American, followed by 28.7% non-Hispanic White, 6% Latinos, 1.3% Black/African American, 1.3% Native American, and 23.8% were listed as “Other”. More details about the study sample are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for Study Sample (N = 80).

| Study variable | Study sample | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 42.06 (7.67) | |

| Gender | Male | 40 (50) |

| Female | 40 (50) | |

| Race | Black/African American | 1 (1.3) |

| Asian American | 24 (30.0) | |

| Native American | 1 (1.3) | |

| Latino/Latina | 6 (7.5) | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 23 (28.7) | |

| Other | 19 (23.8) | |

| Prefer not to answer | 6 (7.5) | |

| Relationship status | Single | 4 (5.0) |

| Married | 68 (85.0) | |

| Divorced | 2 (2.5) | |

| Widowed | 1 (1.3) | |

| Dating/not married | 3 (3.8) | |

| Education | 1–5 years college | 31 (38.8) |

| Undergraduate | 11 (13.8) | |

| Some graduate school | 1 (1.3) | |

| Graduate degree | 32 (40.0) | |

| Children | Number of kids | 2.1 (0.97) |

| Age of youngest kids | 8.7 (6.67) | |

| Age of oldest | 13.4 (8.5) | |

| Household income | <$25,000 | 3 (3.8) |

| $25,000–$49,999 | 20 (25.0) | |

| $50,000–$74,000 | 24 (30.0) | |

| $75,000–$99,000 | 16 (20.0) | |

| $100,000–$124,000 | 1 (1.3) | |

| $125,000–$149,000 | 7 (8.8) | |

| $150,000–$174,000 | 4 (5.0) | |

| $175,000–$200,000 | 1 (1.3) | |

| >$200,000 | 1 (1.3) | |

| Minutes spent educating children per day | During COVID19 | 124.8 (101.07) |

| Before COVID19 | 55.3 (50.03.9) |

Note. Quantitative information is presented as means with standard deviation in parentheses. Categorical information is presented as counts, with column percentages in parentheses.

Procedure

Parents of the children attending schools in South-Central United States were invited to complete and share an online survey with their friends and family members who also had children who studied in elementary and middle schools. Interested instructors at a South-Central United States university were invited to share a link to an online survey with their friends and family members. The online survey followed the snowball sampling procedure to identify additional participants. A total of 111 participants were contacted through the snowball sampling. However, a total of 80 participants (50% female) completed the survey questionnaires. Thirty-one participants were dropped as they did not complete the entire survey. When accessing the survey, participants were made aware of the qualifications, which were to have at least one child enrolled in elementary or middle school. The participants also had to be at least 18 years old and be a parent. The online survey took ∼20 min to complete. All elements of this research project were approved by the appropriate institutional review board.

Measures

Before and during COVID

Participants reported their observation about their children’s learning and other psychosocial developmental activities by drawing a comparison of the same activities done by the children before and during the COVID-19 period. Participants were asked to recall the amount of time spent in educational activities with their child before the pandemic and then to report the current time spent in educational activities. As well, parents reported their parental support, motivation and children’s behavior as related to questions of mental health or potential impact of the pandemic. Sample questions includes: “How many minutes on average per day do you spend helping educate your child(s) during the COVID-19 pandemic?” and “How many minutes on average per day did you spend helping to educate your child(s) before the COVID-19 pandemic?” Similarly, parents answered questions related to their children’s behavioral, social, and emotional development, such as: “How do you rate your child(s)’s externalizing (being mean, abrasive, anger, etc.), internalizing (i.e., being withdrawn, anxious, depressed, stressed etc.), prosocial behaviors (i.e., being helpful, following the rules, etc.) before the COVID-19 pandemic?” and “How do you rate your child(s)’s externalizing, internalizing, prosocial behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic?” Responses for each question ranged from 1 (very low or poor) to 7 (very good or high). The responses of the participants are presented in Table 2 as a means and standard deviation for the period before and during COVID-19.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics of Children’s Behavior Before and During COVID-19 (N = 80).

| Before and during COVID-19 (n = 80) | Before (Mean, SD) | During (Mean, SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Time spent to educate the children | 55.29 (50.03) | 124.77 (101.07) *** |

| Academic performance | 6.13 (0.77) | 5.36 (1.05) *** |

| Motivation in school activities | 6.09 (1.02) | 5.31 (1.35) *** |

| Socialize with friends | 5.32 (1.46) | 3.29 (1.50) *** |

| Externalizing behavior (mean, abrasive, etc.) | 4.62 (1.99) | 4.41 (1.65) |

| Internalizing behavior (withdrawn, stressed, anxious, etc.) | 4.60 (1.83) | 2.83 (1.63) *** |

| Prosocial behavior | 5.91 (1.04) | 5.10 (1.31) *** |

| Discipline | 4.28 (1.38) | 3.86 (1.47) |

Note. Comparative information is presented as means and standard deviation in different constructs to compare student behavior before and during COVID-19 period in the 7-point Likert scale, 1 = very poor/low and 7 = very high/good.

***p < .001; **p < .01; *p < .05.

Depression-Anxiety-Stress Scale

Parental well-being was captured on each daily online survey through the Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scales (DASS-21; Henry and Crawford, 2005). This 21-item scale contains seven items related to each of the aspects of well-being: depression, anxiety, and stress. Examples include “I felt down-hearted and blue” (depression), “I felt I was close to panic” (anxiety), and “I tend to over-react to situations” (stress). Responses ranged from 0 (did not apply to me at all) to 3 (applied to me very much, or most of the time). Internal consistency was acceptable for all three measures for each day (Cronbach’s alpha ranges: depression = 0.89; anxiety = 84; stress = 0.88).

Data Analysis

The study’s hypothesis focused on the impact of COVID-19 on the children’s learning performance and sociopsychological development in the period before and during COVID-19. To address the impact of COVID-19, paired sample t-tests and ANOVAs were conducted to compare the parents’ reports of children’s performance and sociopsychological development rated retrospective for before the pandemic and currently to assess current functioning. These analyses were conducted in relation to the time parents spent educating their children, their children’s academic performance, motivation, socialization, behavior, and discipline. Similarly, multiple regression analysis was conducted to determine the relationship between parental support, motivation and socioemotional development and children’s attainment in learning during COVID-19. Moderation effects were also analyzed through multiple regression analysis to find the relationship between parental support, parental motivation, and socioemotional behavior (prosocial, internalization, externalization, and discipline) and learning attainment during the COVID-19 period. To conduct moderation analyses, we followed the guidelines provided by Aiken and West (1991). For this analysis, parental support, parental motivation, and socioemotional behavior (prosocial, internalization, externalization, and discipline) were mean centered and included as predictors for learning attainment in this study.

Results

The paired sample t-tests were used to analyze the parents’ perspectives on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic regarding the stay-at-home order by comparing before and after COVID-19 on different areas related to children’s learning performance and sociopsychological development. The results of these analyses are presented in Table 2. Our analysis found supporting evidence for the research RQ1 and RQ2. The mean of the different questions related to the hypothesis during COVID-19 was statistically higher than in before COVID-19 period.

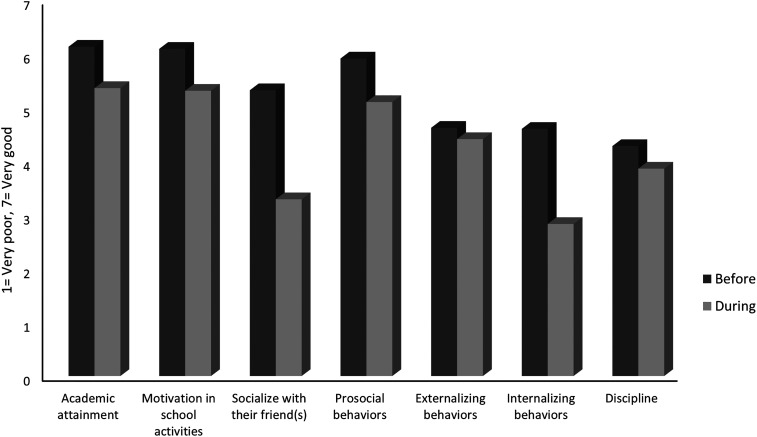

As anticipated, the time parents spent educating their children during COVID-19 was statistically significantly greater than the amount of time spent before COVID-19 (t(79) = 8.61, p = <.001, see Table 3). The result of the children’s academic performance during COVID-19 was also found to be significantly less than the mean of the academic performance before COVID-19 (M = 55.29, SD = 50.03, t(79) = −6.39, p = <.001). Children’s motivation in teaching learning activities during COVID-19 (M = 5.36, SD = 1.05) was found to be significantly less than the mean of the motivation in teaching learning before COVID-19 (M = 6.09, SD = 1.01, t(79) = −5.52, p = <.001). The regular contact and socialization with friends during COVID-19 (M = 3.29, SD = 1.49) was also significantly lower than the mean of the socialization and contact with friends before COVID-19 (M = 5.32, SD = 1.46, t(79) = −9.63, p = <.001). Similarly, prosocial behaviors such as being helpful and following rules during COVID-19 (M = 5.10, SD = 1.31) was also significantly lower than the mean of the prosocial behaviors before COVID-19 (M = 5.91, SD = 1.04, t(79) = −5.04, p = <.001). The details are presented in Table 3 and Figure 2.

Table 3.

Paired samples t-tests (N = 80).

| Before and during COVID-19 (n = 80) | Mean | SD | t |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time spent (minutes per day) | 69.45 | 8.07 | 8.61*** |

| Academic performance | −0.77 | 0.12 | 6.39*** |

| Motivation in learning activities | −0.78 | 0.14 | −5.52*** |

| Socialization with friends | −2.04 | 0.21 | −9.63*** |

| Externalizing behavior | −0.22 | 0.19 | −1.12 |

| Internalizing behavior | −1.77 | 0.33 | −5.38*** |

| Pro-social behavior | −0.81 | 0.16 | −5.04*** |

| Discipline | −0.42 | 0.28 | −1.44 |

Note. Paired sample t-test results are presented as means and standard deviation with t-test results in different constructs to measure the statistical significance before and during COVID-19 period.

***p < .001; **p < .01; *p < .05.

Figure 2.

Children’s learning attainment and psychosocial development before and during COVID-19.

Note. This figure displays academic performance, children’s motivation in school, socialization with their friends and prosocial behavior, discipline, externalizing and internalization behavior before and during the COVID-19 period (mean score by categories and based on the 7-point Likert scale, 1 = very poor/low and 7 = very high/good).

Parents reported that there was a decrease in academic performances, motivation to participate in school activities, communication with friends for socialization, and prosocial behavior for their children during the COVID-19 period. Parents also reported that there was a bigger communication gap with friends during the remote learning COVID-19 period, which influenced low socialization. Internalizing behaviors such as being withdrawn, anxious, depressed, and stressed was significantly poor during COVID-19 (M = 2.83, SD = 1.63) than the mean of the internalizing behaviors before COVID-19 (M = 4.60, SD = 1.83, t(79) = −5.38, p = <.001). Similarly, externalizing behaviors such as being mean, and abrasive before (M = 4.62, SD = 1.99) and during (M = 4.41, SD = 1.65, t(79) = −1.12, p = .266) the pandemic and following rules as a discipline before (M = 4.28, SD = 1.38) and during (M = 3.86, SD = 1.47, t(79) = −1.44, p = .153) the pandemic was not significantly different during the COVID-19 period (see details in Figure 2).

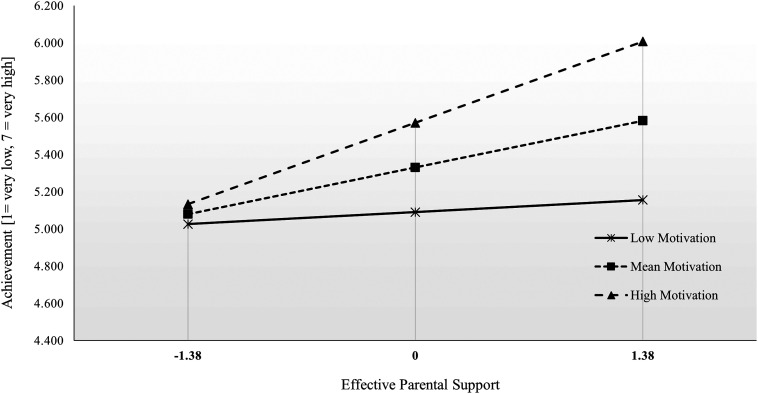

Parental support and motivation were positively associated with positive emotions on children, which pertains to better learning attainment for children. The overall moderation model between parental motivation and support on children’s learning attainment was significant, R2 = 0.189, F(3, 76) = 5.90, p = .001. Children’s learning attainment during the COVID-19 period was significantly predicted by parental support (b = 0.182, t(76) = 2.23, p = .03) and motivation (b = 0.178, t(76) = 2.18, p = .03), and the interaction between parental support and motivation significantly moderated the effect on children's learning attainment (b = 0.100, t(76) = 1.89, p = .06). Figure 3 shows that the interaction between effective parental support and motivation on children’s learning attainment indicates that a higher level of parental support and motivation increased the learning attainment of children during the COVID-19 period (Tables 4 and 5).

Figure 3.

Interaction between effectiveness of parental support and motivation on children’s attainments during COVID-19.

Note. The figure illustrated the significant moderation effect between effective parental support and level of motivation on children’s learning attainment.

Table 4.

Effect of Parental Support and Motivation on Children’s Learning During COVID-19.

| Variables | β | b (SE) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parental motivation | 0.230* | 0.178 (0.082) | .03 | 0.189 |

| Effect of parental support | 0.240* | 0.182 (0.082) | .03 | |

| Parental motivation × effect of support | 0.201 | 0.100 (0.053) | .06 |

Note. β = standardized regression coefficient, b = unstandardized regression coefficient, SE = standard error of unstandardized regression coefficient, = delta R square.

***p < .001, **p < .01, *p < .05.

Table 5.

Effect of Externalization and Internalization Behavior on Children’s Learning During COVID-19.

| Variables | β | b (SE) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Externalization behavior | −.386** | −0.259 (0.084) | .003 | 0.189 |

| Internalization behavior | .110 | 0.061 (0.063) | .332 | |

| Externalization × internalization | −.002 | −0.001 (0.039) | .990 |

Note. β = standardized regression coefficient, b = unstandardized regression coefficient, SE = standard error of unstandardized regression coefficient, = delta R square.

***p < .001, **p < .01, *p < .05.

Children's externalizing and internalizing behavior was significantly associated to children's learning attainment during the COVID-19 period. The overall moderation effect between externalizing and internalizing behavior on children's learning attainment was found to be significant, R2 = .189, F(3, 76) = 5.92, p = .001. Children’s learning attainment during the COVID-19 period was significantly predicted by externalizing behavior (b = −0.259, t(76) = −3.09, p = .003) but internalizing behavior did not account for significant amount of additional variance on children’s learning attainment (b = 0.061, t(76) = 0.98, p = .339).

Discussion

Educating children during the COVID-19 pandemic period is a challenging task for parents and teachers. Technology-based teaching strategies for children in early grades and teens was adopted in COVID-19 through a rapid transition in modality. This transition has been challenging for teachers, students, and parents in adjusting to the online pedagogy (Lau & Lee, 2020). The transition and drastic changes in the pedagogical modality raised issues regarding children and teens’ scholastic performances (Koskela et al., 2020), children’s social behaviors in interacting with teachers, families, and peers (Koh & Liew, 2020), and maintaining students’ interest in online classroom learning (Dhawan, 2020). Similarly, negative emotional development in the pandemic period were more likely to develop in children with less supportive relationships with peers, teachers, and those who did not enjoy class activities, resulting in lower-level performances (Campbell et al., 2016).

In this study, we explore these potential concerns by analyzing parents’ perceptions of the impact of COVID-19 on children’s school performances and psychosocial development before and during the COVID-19 period. The questions that were asked regarding children’s motivation on learning were: How motivated was your child(s) in school activities (such as classroom activities, homework) before the COVID-19 pandemic? And how motivated are your child(s) in school activities (such as Zoom class sessions, homework) during the COVID-19 pandemic? Based on the study results, children’s academic performances, motivation for participating in teaching learning activities performed through ORL, socialization with friends and prosocial behavior with parents and family members all decreased during the COVID-19 period when compared to before the pandemic. All emotional and social competencies are influenced by children’s harsh or disengaged parenting circumstances, parental caregiving, chronic poverty, family stress, and parent depression (Campbell et al., 2016). Children’s family and social context in the COVID-period and other factors such as ORL modality, learning environment, technological infrastructure, and social distancing with peers and teachers determined their long-term outcomes (Lau & Lee, 2020).

ORL modality increased parental responsibilities during COVID-19 to more than double the normal time that parents used to spend educating their children before the COVID-19 period. The main reason for the increase of parental responsibilities was due to the sudden school closure and shift from face-to-face learning modality to ORL. The study also found that more educated parents were more responsible and spent more time educating their children in the pandemic. Data shows that parents who had graduate degrees spent 159 min per day to help with their children’s learning while undergraduate parents spent 114 min, and parents with up to 5 years of college experience spent 85 min.

Thus, there is an indication that there was a close connection between parental education, parental support, and family socioeconomic level with children’s educational access and the quality of education (Bell & Wolfe, 2004) children received during the pandemic period. For instance, wealthy families spent more time in their children’s learning and their children had more access to educational resources as well as personal tutoring during the COVID-19 period to provide more support in their learning (Andrew et al., 2020). On the other hand, single parents who were responsible for working in a remote environment also had to do additional chores at home such as making meals for their children and supporting them in daily learning activities, making it hard for them to manage their own daily schedules (Koskela et al., 2020). The parents’ involvement increased due to the extra time they had to spend to prepare meals for their children whereas their children might have received meals from school meal programs before the pandemic.

This study found family education to be the predominant element in children’s education and learning during the COVID-19 period, which was similar to what Jæger and Blaabæk (2020) stated regarding how children from high socio-economic families had more access to learning materials and digital environment. Thus, both educational qualifications and social status of the family members caused lower performance of the children who did not have the same opportunities as those who come from a high socioeconomic status (Lau & Lee, 2020), leading to an inequality in education. The decreasing trend in learning and the lower level of motivation in ORL during COVID-19 challenged teachers and educators to amplify their teaching methods so they could improve their students’ performance. In this situation, teachers and educators should consider bridging or creating an alternative performance recovery strategy through various modalities.

During the COVID-19 period, ORL processes required children to be more engaged in educational activities with the help of parents in their learning processes. Thus, the questions asked for the parents in the survey were: How effective do you think your approach to educating your children is for their learning during COVID-19? And how engaged are your children when you spend time educating them? It was found that there was a lower level of satisfaction and motivation for children to engage with parental support during COVID-19. One of the stark reasons was the lack of sufficient skills in parents to teach their children in the online modality as well as children’s satisfaction and motivation exhibited for learning (Lau & Lee, 2020).

Children’s interest and attention in their learning, and direct feedback and support received from the school decreased during the remote learning period, which appeared to impact their performances and motivation for learning. This study found that parental support and motivation were the most influencing factors in developing positive emotions that affect children’s learning attainment (Bell & Wolfe, 2004; Lau & Lee, 2020). The result of the moderation effect of the parental support and motivation was the impact on children’s learning attainment during the COVID-19 period. This situation not only affected the children’s learning performance, but it might also impact children’s long-term educational journey (Campbell et al., 2016). It might be the cause behind children’s doubt and fear on their performances, leading towards socioemotional problems and such socioemotional competencies can be responsible in predicting academic performances (Denham, 2006).

The study also found that the academic progress and socioemotional development of children depends on effective interactions and positive engagement in learning activities with peers and teachers (Denham, 2006); however, parental support and motivation was found to be more important during the COVID-19 period. While some virtual classes helped children meet their peers and teachers and have discussions online, the long gap in physical contact with their peers lead the children towards social isolation and loneliness that potentially increased the risk of positive personal development (Loades et al., 2020) and a decrease in social opportunities, which may explain declines in children's psychological well-being and the quality of educational outcomes (Koskela et al., 2020).

Prosocial behaviors such as being helpful in parents’ daily routine was found to be lower during the COVID-19 period. The reason might be that staying at home every day within a small physical boundary was not a conducive environment for children to exhibit prosocial performances. Simultaneously, a lack in parents’ plans to engage children in different prosocial activities at home or conduct safe outdoor activities might have caused the decline in the cultivation of the children’s social responsibilities during the COVID-19 period. However, parents who succeeded in having their children engage in social activities found a positive benefit for their children that could be helpful for their well-being and may play a vital role in their future prosocial actions at the community level (Alvis et al., 2020).

The study indicated that internalizing behaviors such as being withdrawn, anxious, depressed, and stressed was reported to be higher during the COVID-19 period. However, externalizing behaviors, such as being mean and abrasive, as well as not following rules remained slightly lower during the COVID-19 period. The social distancing and loneliness may have triggered negative feelings from children that resulted in more mental health issues as a possible post-traumatic stress (Loades et al., 2020).

Social distancing and school closures resulted in a remote learning environment for students throughout the world. This situation demotivated children’s learning and development. This study found that children’s learning performances and motivation towards remote learning activities decreased during the COVID-19 period. Social distancing, isolation from peers and teachers, supportive home environment, access to digital learning, and consistent information technology infrastructures are the contributing factors involved in students' school performances and motivation during the pandemic. Having low learning motivation and performance might increase school dropout rates that can result in long-term personal development of children. Thus, further investigation will be needed to explore all these issues holistically.

Limatations and Conclusion

This study provides evidence for the improvement in learning for children in an online setting through detailed guidelines for parents. There are some limitations of this study that have been noted. Since the survey was conducted by using a snowball sampling procedure, it is not representative of the population. Similarly, the survey was conducted in the early stage of the COVID-19 period and participants were primarily parents of elementary and middle school children, which might limit the scope of the study. This study represents the homogenous population, particularly 59% of the participants were White Americans and Asian Americans.

Another limitation of the study is the lower number of participants in the study. The reason for that was because the study was designed to collect the parental perception on their children’s emotions and behaviors as well as issues faced before and during COVID-19, primarily during the earlier stage of the crisis. Given that many parents were tasked with assisting their own children’s education as well as navigate their own experience with COVID19, it is likely that many individuals could not find time to participate in this study, nor would they be motivated to participate. The main aim of this study is to collect immediate memorable comparative information regarding children. In this regard, this study was limited and included 80 participants. However, the result of the study will provide insight for future research.

Despite the limitations, this study examines the various impacts of COVID-19 in the perspective of parents. The study compares parents’ involvement in children’s ORL modality before and during COVID-19. Similarly, the study focuses on the children’s behavior and learning performances before and during COVID-19 such as their motivation on online learning, socialization with peers, externalizing, internalizing and prosocial behavior and discipline. The overall comparison of the study indicates that the children’s socialization process, prosocial, internalizing, and externalizing behavior, as well as need to follow discipline at home decreased during COVID-19.

The results of this study also highlighted that the time spent by parents on their children’s learning was closely connected with parental education. Those children who belonged in an educated family had a higher chance in receiving support from their parents. However, the results of this study highlighted that child were not motivated with just parent supported online learning when compared to face-to-face modes. The reason for the demotivation on the parent supported online learning might be due to an insufficient knowledge on their children’s subject matter and pedagogy. On the other hand, single parents have their own challenges related to having to complete multiple tasks at home such as their official work, food preparation, and other daily work. These reasons need to be explored in future studies to analyze challenges faced by the parents in the COVID-19 period.

Footnotes

Data Availability Statement: Data is available upon request from the first author.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Institutional Review Board Statement: The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of North Texas (IRB-20-266).

Informed Consent Statement: Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

ORCID iD: Bhoj B. Balayar https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0288-7448

References

- Aiken L. S., West S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Alvis L., Oosterhoff B., Shook N. J. (2020). Adolescents’ prosocial experiences during the covid-19 pandemic: Associations with mental health and community attachments. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/2s73n [Google Scholar]

- Andrew A., Catta S., Costas-Dias M., Farquharson C., Kraftman L., Krutikova S., Phimister A., Sevilla A. (2020). Learning during the lockdown: Real-time data on children’s experiences during home learning. IFS briefing note BN288. Institute for Fiscal Studies. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell M. A., Wolfe C. D. (2004). Emotion and cognition: An intricately bound developmental process. Child Development, 75(2), 366–370. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00679.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell S. B., Denham S.A., Howarth G. Z., Jones S. M., Whittaker J. V., Williford A. P., Willoughby M. T., Yudron M., Darling-Churchill K. (2016). Commentary on the review of measures of early childhood social and emotional development: Conceptualization, critique, and recommendations. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 45, 19–41. 10.1016/j.appdev.2016.01.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Denham S. A. (2006). Social-emotional competence as support for school readiness: What is it and how do we assess it? Early Education and Development, 17, 57–89. 10.1207/s15566935eed1701_4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dhawan S. (2020). Online learning: A Panacea in the time of COVID-19 crisis. Journal of Educational Technology Systems. 10.1177/0047239520934018 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eccles J. S. (2005). Influence of parents’ education on their children’s educational performance: The role of parent and child perceptions. London Review of Education. 10.1080/14748460500372309 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Education week (2020). The coronavirus spring: the historic closing of U.S. schools. A timeline. https://www.edweek.org/ew/section/multimedia/the-coronavirus-spring-the-historic-closing-of.html.

- Ewing L., Cooper H. B. (2021). Technology-enabled remote learning during covid-19: Perspectives of Australian teachers, students and parents. Technology, Pedagogy and Education, 30(1), 41–57. 10.1080/1475939X.2020.1868562 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gao J., Zheng P., Jia Y., Chen H., Mao Y., Chen S., Wang Y., Fu H., Dia J. (2020). Mental health problems and social media exposure during COVID-19 outbreak. PLoS ONE, 15(4), e0231924. 10.1371/journal.pone.0231924 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia E., Weiss E. (2020). COVID-19 and student performance, equity, and U.S. education policy. Economic Policy Institute. https://www.epi.org/publication/the-consequences-of-the-covid-19-pandemic-for-education-performance-and-equity-in-the-united-states-what-can-we-learn-from-pre-pandemic-research-to-inform-relief-recovery-and-rebuilding/.

- Gassman-Pines A., Ananat E. O., Fitz-Henley J., II (2020). COVID-19 and parent-child psychological well-being. Pediatrics, 146(4). 10.1542/peds.2020-007294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giannini S. (2020). Reopening schools: When, where and how? UNESCO. https://en.unesco.org/news/reopening-schools-when-where-and-how.

- Golberstein E., Wen H., Miller B. F. (2020). Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) and Mental Health for Children and Adolescents. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.1456.

- Harcourt J., Tamin A., Lu X., Kamili S., Sakthivel S. K., Murray J.…Thornburg N. J. (2020). Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 from Patient with Coronavirus Disease, United States. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 26(6), 1266–1273. 10.3201/eid2606.200516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Henry J. D., Crawford J. R. (2005). The short-form version of the depression anxiety stress scales (DASS-21): Construct validity and normative data in a large non-clinical sample. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 44(2), 227–239. 10.1348/014466505X29657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jæger M. M., Blaabæk E. H. (2020). Inequality in learning opportunities during covid-19: Evidence from library takeout. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility. 10.1016/j.rssm.2020.100524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapasia N., Paul P., Roy A., Saha J., Zaveri A., Mallick R., Barman B., Das P., Chouhan P. (2020). Impact of lockdown on learning status of undergraduate and postgraduate students during COVID-19 pandemic in West Bengal, India. Children and Youth Services Review, 116, 105194. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh J. X., Liew T. M. (2020). How loneliness is talked about in social media during COVID-19 pandemic: Text mining of 4,492 Twitter feeds. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.11.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koskela T., Pihlainen K., Piispa-Hakala S., Vornanen R., Hämäläinen J. (2020). Parents’ views on family resiliency in sustainable remote schooling during the COVID-19 outbreak in finland. Sustainability, 12(21), 8844. MDPI AG. 10.3390/su12218844. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lancker W. V., Parolin Z. (2020). COVID-19, school closures, and child poverty: A social crisis in the making. The Lancet. 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30084-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau H. E. Y., Lee K. (2020). Parents’ views on young children’s distance learning and screen time during COVID-19 class suspension in Hong Kong. Early Education and Development. 10.1080/10409289.2020.1843925 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leigh-Hunt N., Bagguley D., Bash K., Turner V., Turnbull S., Valtorta N., Caan W. (2017). An overview of systematic reviews on the public health consequences of social isolation and loneliness. Public Health, 152, 157–171. 10.1016/j.puhe.2017.07.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Zhou S. (2021). Parental worry, family-based disaster education and children’s internalizing and externalizing problems during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 10.1037/tra0000932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loades M. E., Chatburn E., Higson-Sweeney N., Reynolds S., Shafran R., Brigden A., Linney C., McManus M. N., Borwick C., Crawley E. (2020). Rapid systematic review: The impact of social isolation and loneliness on the mental health of children and adolescents in the context of COVID-19. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 10.1016/j.jaac.2020.05.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations (2020). Policy brief: the impact of COVID-19 on children. https://www.un.org/sites/un2.un.org/files/policy_brief_on_covid_impact_on_children_16_april_2020.pdf.