Abstract

As the coronavirus disease of 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic disrupted all aspects of life, parents have been subjected to more household and caregiving responsibilities and stressors. The purpose of this study is to investigate how hope, self-compassion, and perception of COVID-19 health risks influence parenting stress. In this cross-sectional study, a total of 362 parents living in the United States completed an online survey in July 2020. Multiple regression analyses revealed that higher levels of hope are related to lower levels of parenting stress. On the other hand, lower levels of self-compassion as indicated by higher scores on the subscales of isolation, self-judgment, and overidentification are related to higher levels of parenting stress. Further, testing positive for the coronavirus is positively related to parenting stress, whereas the belief that COVID-19 is a serious disease is negatively related to parenting stress. Findings also revealed the significant role of hope in moderating the relation between self-compassion and parenting stress. This study highlights the importance of nurturing and drawing from one’s own psychological resources to mitigate parenting stress, particularly in the context of a chronic source of stress like a pandemic. Implications for the counseling profession are discussed.

Keywords: parenting stress, hope, self-compassion, COVID-19 pandemic

Introduction

The spread of the coronavirus disease of 2019 (COVID-19) has disrupted all aspects of life since it was declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization in March 2020. Aside from examining its physiological health risks, researchers have also started identifying the effects of the pandemic on families’ mental health and well-being. Although the majority of the population from all sectors of society have been impacted by the pandemic, parents and caregivers face unique, and possibly greater challenges with increased caregiving and household responsibilities, increasing vulnerability to stress. Recent studies that explored the parenting experience during the pandemic found a host of negative mental health outcomes and undesirable parenting behaviors related to parenting stress (Gadermann et al., 2021; Goldberg et al., 2021; Horiuchi et al., 2020; Mikolajczak & Roskam, 2020; Miller et al., 2020; Weaver & Swank, 2021). Given the pandemic’s enormous toll on parents, as well as the limited access to support systems and other external resources, family counselors will benefit from identifying resources to assist clients who are parents in maximizing their own psychological resources to moderate the negative effects of stress on their parenting and well-being.

Theoretical Framework

This study is framed using a family systems theoretical perspective. Families are interdependent systems where what is occurring for one member of the family, such as stress and concern or changes in schooling, impacts the family as a whole, including dynamics and challenges (Ackerman, 1984; Kerr & Bowen, 1988). Yet families are goal-oriented systems that try to maintain equilibrium in the face of internal or external challenges and changes, trying to maintain existing boundaries and patterns. Ideally, family members must work together to make decisions and solve problems through communication and feedback loops to seek a balance between the changes and maintaining stability (Olson, 2000; Whitchurch & Constantine, 1993).

Parenting Stress

Parenting entails substantial demands and responsibilities, and stress is considered a regular part of the parenting experience (Deater-Deckard et al., 2017). According to Abidin (1992), parenting stress occurs when an individual perceives demands related to the parenting role as greater than their perceived competence or available resources. Some sources of parenting stress include family structure (e.g., number of children), employment demands and work stress, child temperament and problematic behaviors, household income (Schneewind et al., 2012; Warfield, 2005), as well as everyday tasks of parenthood (Crnic & Low, 1995).

Recent research in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic highlighted additional multiple stressors beyond parents’ control. For example, addressing the pandemic has necessitated drastic life changes such as staying at home and social distancing to help prevent the spread of the virus. Brown et al. (2020) purported that with limited outside social interaction and increased demands at home, parents may be especially vulnerable to stress and other mental health concerns. Concerns regarding the negative impact of the pandemic on finances, employment, and psychological health were also found to contribute to parenting stress (Chung et al., 2020). More importantly, the majority of parents in the United States identified having a family member get infected as a significant source of their stress (APA, 2020).

With school closures across the country, parents and children have also been abruptly subjected to home-based schooling (Janssen et al., 2020). This required parents to supervise their children, even if they are not necessarily prepared or equipped to teach them. These problems are magnified for families that experience challenges in accessing reliable internet connections and technological devices (Lee et al., 2021). In fact, in a survey of more than 3,000 adults in the United States, 71% responded managing distance learning is contributing to parenting stress (APA, 2020). The increased time of necessary parental supervision is especially difficult for employed parents who also had to deal with working remotely from home (Chung et al., 2020), as work and school hours greatly overlap. In addition, because there were also disruptions in childcare arrangements and other services and programs catering to children (Lee et al., 2021), parents are burdened by additional responsibilities without additional support. In all, adults with children were found to report more stress compared to adults with no children during the COVID-19 pandemic (APA, 2020; Goldberg et al., 2021).

Consistently, research has shown that parenting stress is related to a host of undesirable outcomes, both for the parent and the child (Morris et al., 2017). For example, higher parenting stress was found to predict more harsh and hostile parenting (Chung et al., 2020; Jackson et al., 2019). Consequently, greater reports of hostile parenting and punitive punishments were found to correlate with increased levels of externalizing behaviors among children (Bradley & Corwyn, 2007). Given these negative repercussions, it is important to examine different pathways that can help alleviate parenting stress. In the context of a pandemic where social interaction is limited and access to relevant services may be a challenge, enhancing one’s own psychological resources may be especially beneficial in helping manage parenting stress.

Self-Compassion and Parenting Stress

Derived from empathy, compassion includes having strong feelings related to the suffering of others, as well as a desire to alleviate someone’s pain (Fulton, 2018; Siegel & Germer, 2012). More specifically, self-compassion is “being open to and moved by one’s own suffering, experiencing feelings of caring and kindness toward oneself, taking an understanding, nonjudgmental attitude toward one’s inadequacies and failures, and recognizing that one’s own experience is part of the common human experience” (Neff, 2003, p. 224). Essentially, self-compassion is an effective regulation tactic to manage and cope with difficult situations, thoughts, and feelings (Berryhill et al., 2018).

Self-compassion is comprised of conceptually separate and reciprocally influencing elements which describe how individuals respond to suffering (with kindness towards self or judgment towards self), how they understand their difficulty (as a part of their humanness or as isolating), and how they pay attention to their pain (with mindfulness or overly identifying with their difficulty; Germer & Neff, 2019; Neff, 2016). Self-kindness acknowledges the interconnectedness of suffering as a part of the human experience. On the contrary, self-judgment increases negative feelings of isolation and abnormality. Humans are biologically social beings, and while self-kindness enhances benevolence towards the self, common humanity shines a light on the importance of the social connectedness fundamental to the human condition (Germer & Neff, 2019). Finally, to be self-compassionate we must recognize when feelings of pain arise. When attended to with a balanced awareness of mindfulness, we receptively pay attention to the present moment without judgment and can acknowledge that feelings of suffering exist without denying, resisting, or repressing them. Further, mindfully attending to our painful feelings encourages the separation of negative affect from interfering with how we view ourselves (Germer & Neff, 2019).

Existing literature suggests that self-compassion may be an effective target for increasing parenting quality and decreasing parental distress (Felder et al., 2016; Gouveia et al., 2016; Jefferson et al., 2020; Moreira et al., 2015; Psychogiou et al., 2016). Research has found that high parental self-compassion is associated with lower parental distress (Beer et al., 2013; Gouveia et al., 2016), lower parental depression (Felder et al., 2016), lower parental anxiety (Beer et al., 2013; Felder et al., 2016), lower levels of mothers’ child-directed criticism, and fewer distressed reactions from fathers to child negative emotions (Neff & Faso, 2015). Higher parental self-compassion is also associated with greater emotional resiliency and greater life satisfaction (Neff & Faso, 2015). Additionally, higher parental self-compassion is associated with decreased incidence of child emotional and behavioral concern (Beer et al., 2013; Psychogiou et al., 2016). Self-compassion has been found to mediate relationships between constructs related to parenting quality (Gouveia et al., 2016; Jefferson et al., 2020; Moreira et al., 2015, 2016).

Hope and Parenting Stress

Existing research suggests that hope can buffer against parental stress and parental maladjustment or well-being (Faso et al., 2013; Horton & Wallander, 2001; Mednick et al., 2007. Although several definitions and measurements exist (Schrank et al., 2008), the most prominent conceptualization of hope for the past two decades is Snyder’s hope theory which defines hope as “a positive motivational state that is based on an interactively derived sense of successful (a) agency (goal-directed energy), and (b) pathways (planning to meet goals)” (Snyder et al., 1991, p. 287). Pathway thinking refers to an individual’s belief that they are capable of formulating pathways for obtaining their goals. Agency thinking pertains to a person’s perceived ability to utilize these pathways to successful achieve their desired goals.

Hope contributes to resiliency and well-being by serving as a protective factor that can buffer against negative life events and adversity (Lopez, 2013). Among parents, hope is negatively associated with parental distress (Horton & Wallander, 2001), predictive of depressive symptoms and life satisfaction (Faso et al., 2013), and moderates the relationship between stress and parental maladjustment (Horton & Wallander, 2001). Parental hope and a growth mindset can also mediate the negative relationship between parental stress and children’s well-being (Lee, 2016).

Hope and Self-Compassion

Self-compassion encompasses an individual’s thoughts and emotions about the present (Neff, 2003) while hope involves cognitions about the self and the future (Snyder et al., 1991). Existing research has found that self-compassion is positively associated with hope (Umphrey & Sherblom, 2014) and predictive of life satisfaction (Neff & Faso, 2015). Furthermore, hope has been found to mediate the relationship between self-compassion and life satisfaction (Yang et al., 2016). Both hope and self-compassion are negatively associated with depression, stress, and anxiety (Todorov et al., 2019).

Given the foregoing, this study was conducted to test the following hypotheses:

The self-compassion subscales of self-kindness, common humanity, and mindfulness are negatively related to parenting stress;

The self-compassion subscales of self-judgment, isolation, and over-identified are positively related to parenting stress;

COVID-19 concerns are positively related to stress;

Hope is negatively related to parenting stress; and

With the role of hope as a protective factor, we also hypothesize that the influence of the self-compassion subscales and COVID-19 concerns on parenting stress will vary across different levels of hope.

Method

Participations and Procedures

An online self-administered questionnaire was used to recruit adults in the U.S. during July 2020. A total of 362 adults self-reported having at least one child under 18 years old in their household. Participants who completed the survey received a $10 gift card. The research procedure and survey instrument were approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at the university.

Participants consisted of males and females evenly with an age range of 20–46 years (M = 33.77). Approximately 80% of participants were married or partnered. A majority of participants had an associate degree or higher (67%) and reported a household income of $50,000 or higher (80%; Table 1).

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics of the Variables.

| Variable | M (SD) or % | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (female) | 53.9 | ||

| Age | 33.77 (4.97) | 20 | 46 |

| Marital status | |||

| Single | 20.4 | ||

| Married or partnered | 79.6 | ||

| Educational attainment | |||

| Less than a high school diploma | 0 | ||

| High school diploma or equivalent | 1.7 | ||

| Some college, no degree | 14.6 | ||

| Trade/vocational/technical degree | 16.3 | ||

| Associate degree | 22.4 | ||

| Bachelor’s degree | 34.5 | ||

| Master’s degree | 8.0 | ||

| Professional degree | 0.3 | ||

| Doctorate degree | 2.2 | ||

| Household income (US$) | |||

| 0–24,999 | 0.8 | ||

| 25,000–49,999 | 19.3 | ||

| 50,000–74,999 | 27.6 | ||

| 75,000–99,999 | 22.4 | ||

| 100,000–124,999 | 15.2 | ||

| 125,000–149,999 | 9.7 | ||

| 150,000 and up | 5.0 | ||

| Parenting stress | 50.82 (7.17) | 20 | 70 |

| Hope | 33.07 (6.54) | 15 | 48 |

| Self-kindness | 3.07 (0.54) | 1.80 | 4.80 |

| Humanity | 3.01 (0.57) | 1.25 | 5.00 |

| Mindful | 3.03 (0.56) | 1.50 | 5.00 |

| Self-judgment | 2.98 (0.54) | 1.20 | 4.60 |

| Isolation | 3.02 (0.61) | 1.00 | 4.75 |

| Overidentification | 2.91 (0.57) | 1.00 | 4.75 |

| Tested positive for COVID-19 | 4.4 | ||

| Knowing someone who tested positive for COVID-19 | 13.3 | ||

| Belief that COVID-19 is a serious disease | 4.16 (0.98) | 1 | 5 |

Note. Values do not add up to 100% due to missing responses.

Instruments

Parenting Stress

We used 18-items from the Parenting Stress Scale to measure positive components of parenting such as emotional benefits, self-enrichment, and personal development; as well as negative components including demands on resources, opportunity costs, and restrictions (Berry & Jones, 1995). Respondents rated each item on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Cronbach’s alpha for the current study was 0.65.

Hope

We used the Adult State Hope Scale (ASHS, Snyder et al., 1996) to measure a sense of hope amid the pandemic. The self-reported ASHS consists of three items accessing hope pathways (i.e., an individual’s belief that they are capable of formulating pathways for obtaining their goals) and three items accessing hope agency (i.e., a person’s perceived ability to utilize pathways to successful achieve their desired goals). Respondents rate each item on an 8-point Likert scale from 1 (definitely false) to 8 (definitely true). Responses are summed of all six items as their overall state of hope. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.83.

Self-Compassion

Self-compassion was measured using the 26-item Self-compassion Scale (SCS) (Neff, 2003). This scale measures the distinct and related dimensions of self-compassion: self-kindness, self-judgment, common humanity, isolation, mindfulness, and overidentification. Respondents rate each item on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (almost never) to 5 (almost always). For the subscales of self-kindness, common humanity, and mindfulness, higher scores indicate higher self-compassion; for the subscales of self-judgment, isolation, and overidentification subscales, higher scores indicate lower self-compassion. The original SCS has demonstrated sufficient reliability (a = 0.92), good test-retest reliability (r = .93), and convergent and discriminant validity (Neff, 2003). The Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of the subscales in the present study ranged from 0.44 to 0.57. While it has some psychometric limitations, the SCS was used as it addresses our description of self-compassion (Psychogiou et al., 2016; Williams et al., 2014).

COVID-19 Risk

Participants were asked about their personal experience amid the COVID-19 pandemic, including whether or not they tested positive for COVID-19, knowing someone tested positive, and believing COVID-19 is a serious disease.

Data Analysis

Descriptive analysis and correlation were applied to show the demographic distributions and relationships among variables (Table 2). A series of multiple regression analyses were performed to examine the relationship between self-compassion, hope, COVID-19 risk, and parenting stress. Slope analysis was further employed when moderating effects were detected among predicting variables. The statistical significance level was at the .05 level (p-value).

Table 2.

Correlations Among Variables in the Study.

| Predictors | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Parenting stress | – | |||||||||||||||

| 2. Gender | .110* | – | ||||||||||||||

| 3. Age | .020 | −.024 | – | |||||||||||||

| 4. Marital status | .159** | .257** | −.083 | – | ||||||||||||

| 5. Educational attainment | −.259** | .130* | .001 | .119* | – | |||||||||||

| 6. Household income | −.364** | .047 | −.209** | .075 | .410** | – | ||||||||||

| 7. Hope | −.227** | .093 | −.010 | −.007 | .267** | .300** | – | |||||||||

| 8. Self-kindness | .124* | .133* | .145** | .132* | .061 | −.056 | .259** | – | ||||||||

| 9. Humanity | .106* | .089 | .135* | .106* | −.061 | −.133* | .241** | .505** | – | |||||||

| 10. Mindful | −.007 | .098 | .194** | .060 | .138** | −.043 | .277** | .463** | .445** | – | ||||||

| 11. Self-judgment | .336** | .152** | .108* | −.027 | −.069 | −.183** | .116* | .297** | .329** | .279** | – | |||||

| 12. Isolation | .310** | .041 | .057 | −.149** | −.039 | −.167** | .043 | .264** | .196** | .194** | .470** | – | ||||

| 13. Overidentification | .336** | −.043 | .058 | −.012 | −.126* | −.244** | .041 | .311** | .319** | .204** | .508** | .472** | – | |||

| 14. Testing positive | .147** | −.025 | .113* | −.024 | −.092 | −.027 | .060 | −.031 | .002 | −.042 | .042 | .026 | .930 | – | ||

| 15. Knowing someone who tested positive | −.102 | −.001 | .061 | .097 | .072 | .069 | −.011 | .007 | −.013 | .036 | −.014 | −.060 | −.085 | .005 | – | |

| 16. Belief that COVID-19 is a serious disease | −.109* | −.006 | .080 | .147** | .071 | .107* | .191** | −.040 | −.113* | .038 | .009 | −.050 | −.017 | .048 | .096 | – |

Note. The following variables were dummy-coded: gender (0 = female; 1 = male); marital status (0 = single; 1 = married/partnered); variables 14–15 (0 = did not test positive/did not know anyone; 1 = tested positive; knew someone).

*p < .05; **p < .01.

Results

The first regression model with only the main effects showed that the predictor and control variables accounted for 38% of the variance on parenting stress. The regression model is also significant, F(16, 340) = 13.50, p < .001. Among the control variables, marital status was significantly related to parenting stress, such that those who are married or partnered reported greater parenting stress. Income was also negatively related to parenting stress. Parents testing positive in COVID-19 was also significantly related to increased levels of parenting stress. In the first regression model, as hypothesized, hope was negatively related to parenting stress. The self-compassion subscales of self-kindness, common humanity, and mindfulness were not significant, however, the self-judgment, isolation, and overidentification were significantly related to parenting stress in the expected direction. With the significant regression coefficients of self-judgment, isolation, and overidentification self-compassion subscales, we tested the moderating effects of hope on these three.

On the second regression model, the same control variables and main effects were entered, along with three potential interaction terms among the predictor variables: hope × self-judgment, hope × isolation, and hope × overidentification. The model remains to be significant, F(18, 338) = 13.52, p < .001, and accounted for 42% of the variance. In this second model, the results for the control variables and the remaining subscales of self-compassion (self-kindness, common humanity, and mindfulness) remained the same. Also, the self-compassion subscales of self-judgment, isolation, and overidentification and testing positive for COVID-19 remained significantly related to parenting stress. Interestingly, the belief that COVID-19 is a serious disease is negatively related to parenting stress. Further, the interaction terms hope × self-judgment and hope × overidentification are significantly related to parenting stress (Table 3).

Table 3.

Regression Coefficients (Unstandardized and Standardized), Standard Error Estimates, and Probability (p) Values for the Regression Coefficients in the Regression Model.

| Predictors | B | β | SE | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Constant) | 53.75 | 2.82 | <.001 | |

| Gender | 0.85 | 0.06 | 0.64 | .189 |

| Age | −0.03 | −0.02 | 0.07 | .665 |

| Marital status | 3.50 | 0.20 | 0.82 | <.001 |

| Educational attainment | −0.41 | −0.08 | 0.25 | .108 |

| Household income | −1.11 | −0.22 | 0.25 | <.001 |

| Hope | −0.13 | −0.12 | 0.06 | .020 |

| Self-kindness | 0.17 | 0.01 | 0.70 | .811 |

| Humanity | −0.96 | −0.08 | 0.67 | .151 |

| Mindfulness | −0.79 | −0.06 | 0.65 | .223 |

| Isolation | 1.77 | 0.15 | 0.62 | <.05 |

| Self-judgment | 2.18 | 0.16 | 0.72 | <.05 |

| Overidentification | 1.48 | 0.12 | 0.69 | <.05 |

| Testing positive | 5.68 | 0.16 | 1.52 | <.001 |

| Knowing someone who tested positive | −0.86 | −0.04 | 0.90 | .339 |

| Belief that COVID-19 is a serious disease | −0.79 | −0.11 | 0.33 | <.05 |

| Hope × isolation | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.09 | .929 |

| Hope × self-judgment | 0.28 | 0.15 | 0.10 | <.05 |

| Hope × overidentification | 0.20 | 0.11 | 0.10 | <.05 |

Note. The following variables were dummy-coded: gender (0 = female; 1 = male); marital status (0 = single; 1 = married/partnered); all predictors that were derived from scale scores were centered at the mean.

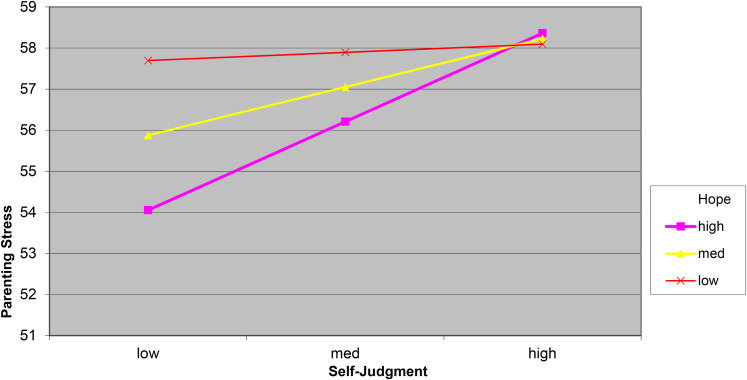

We then conducted a simple slopes analysis (Jose, 2013) to further understand the relation between self-judgment and parenting stress at different levels of hope. For participants with high (1 SD above the mean; slope = 3.99, t = 3.97, p < .05) and medium levels of hope (at the mean; slope = 2.18, t = 3.02, p < .05), the lower their self-judgment scores, the lower their parenting stress. The t-value for those with low levels of hope was not significant (1 SD below the mean; slope = 0.37, t = 3.97, p < .05), suggesting that when hope is low, parenting stress remains high on different levels of self-judgment. Figure 1 shows the interaction of hope and judgment on parenting stress.

Figure 1.

Relations among parenting stress, self-judgment, and hope.

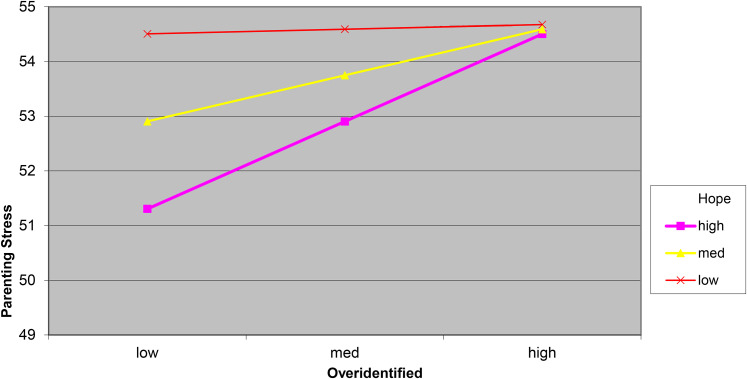

We did the same analysis to examine the relation between overidentification and parenting stress at different levels of hope and the results were similar. For participants with high (1 SD above the mean; slope = 2.80, t = 3.20, p < .05) and medium levels of hope (at the mean; slope = 1.47, t = 2.15, p < .05), lower overidentification scores are related to lower parenting stress. The t-value for those with low levels of hope was not significant (1 SD below the mean; slope = 0.15, t = .14, p < .88), meaning, when hope is low, parenting stress remains unchanged on different levels of overidentification. Figure 2 shows the interaction of hope and overidentification on parenting stress.

Figure 2.

Relations among parenting stress, overidentification, and hope.

Discussion

The current study aimed to examine psychological resources that may moderate the effects of stress on parenting and well-being. The work was framed using a family systems theoretical perspective, which notes that what happens with one member of the family impacts the whole, yet always trying to maintain equilibrium (Kerr & Bowen, 1988; Olson, 2000). A number of our hypotheses were supported by the statistical findings.

First, consistent with existing literature, findings showed a negative association between hope and parenting stress (Horton & Wallander, 2001). Our findings also add to the existing literature by identifying hope as a moderator between self-judgment or overidentification and parenting stress. For example, comparing parents with the same level of self-judgment scores, those with higher levels of hope tend to experience lower parenting stress. When an individual has low levels of hope, however, parenting stress remains high regardless of different levels of self-judgment or overidentification.

Our findings also support previous research which found higher self-compassion was associated with lower parental distress (Beer et al., 2013; Gouveia et al., 2016). Our results suggest individuals who are more self-compassionate and hopeful are less critical of themselves, are less likely to perceive current parenting challenges as personal failures, and are more confident in their ability to achieve future goals (Felder et al., 2016; Gouveia et al., 2016; Jefferson et al., 2020; Moreira et al., 2015; Neff et al., 2007; Neff & Faso, 2015; Psychogiou et al., 2016; Snyder et al., 1991).

In addition, findings also showed that household income is inversely related to parenting stress, suggesting that those with lower income experience higher levels of parenting stress. This is consistent with previous literature showing that lower-income parents are more susceptible to parenting stress. Economic pressure, such as job and food insecurity, has negative effects on parents’ emotions and behaviors, which then influence their parenting resources and strategies (Conger & Conger, 2002). Being married or having a partner was found to be related to increased levels of parenting stress, compared to being single. Although having a parenting partner is usually considered as an asset or a buffer against parenting stress (Solem et al., 2011; Webster-Stratton, 1989), it is plausible that the disruption in home and work set-up, caused by COVID-19 at the time of data collection, as well as the overall anxiety toward the pandemic, may result to more conflict or stress in the relationship (Luetke et al., 2020), and this can ultimately affect the parenting realm.

As expected, contracting COVID-19 is related to increased levels of parenting stress, similar to previous research (Brown et al., 2020; Chung et al., 2020). This may be due to the fact that the coronavirus spreads very easily and may be transmitted even by those who are asymptomatic (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2021). Indeed, in a study among nurses, 64% reported that they were concerned for the health and safety of their families (Arnetz et al., 2020). Although no study to our knowledge has specifically linked contracting COVID-19 to parenting stress among the general population, it is reasonable to deduce that parents falling ill may experience heightened stress.

Interestingly, the belief that COVID-19 is a serious disease is negatively related to stress, such that those who believe that it is serious tend to have lower levels of parenting stress. Although this may sound counterintuitive, we offer a plausible explanation for this finding. Although the subscale of common humanity did not significantly relate to parenting stress in the current study, common humanity emphasizes acknowledgment of the collective human experience of suffering, and these parents’ stress may be lowered because of their recognition that they are not alone in their parenting experience and transitions imposed by the pandemic. Therefore, for parents who consider COVID-19 as a serious disease, there may be more understanding of the challenges brought about by the pandemic, as well as support for safety guidelines and restrictions imposed by businesses and the government. This understanding and acceptance may leave less room for doubt and stress. The current dataset did not allow us to test for this, however, so it is recommended that future research further examine this conjecture.

Implications for the Counseling Profession

COVID-19 has presented new stressors and exacerbated existing stressors for many families. Given the pandemic’s enormous toll on parents, family counselors will benefit from identifying resources to assist clients who have children in maximizing their own psychological resources to moderate the negative effects of stress on their parenting and well-being. Our results suggest that fostering hopeful thinking about the future can help moderate stress, especially for those individuals who engage in self-judgment and overidentification.

Family counselors can teach skills to reduce self-judgment and therefore reduce parenting stress. Parents engaging in self-judgment may have negative self-talk, such as, “I’m a horrible parent,” and “I’m a failure as a parent.” Cognitive-behavioral strategies that identify and adjust maladaptive thought patterns can specifically reduce self-judgment. Self-judgment may be replaced with self-kindness and a kind and encouraging internal dialogue. Beyond solely ending self-criticism, self-kindness entails responding to ourselves as we would to a beloved friend or family member. By offering care, comfort, and nurturance, family members can develop skills to console themselves before moving to problem-solving, protecting, and fixing (Germer & Neff, 2019). For example, self-kindness includes compassionate self-talk such as, “This is really hard right now. I can take a break and care for myself in the moment.” In the context of family counseling, teaching self-kindness to multiple members of the family will reap even greater benefits for the individuals as well as the family system.

Another target of family counseling to reduce parenting stress is the mitigation of overidentification. Parents engaging in overidentification may ruminate and exaggerate their suffering. For example, a parent might believe, “I’m a total disappointment to my children.” Counselors can assist parents by replacing overidentification with mindfulness. Mindful attention to the present experience and not engaging in exaggeration nor judgment of thoughts and feelings. Like self-kindness, mindfulness requires the courage to avoid immediately fixing and problem-solving and instead of recognizing the emotions that arise (Germer & Neff, 2019). For example, “That was a difficult naptime and I’m frustrated and exhausted.” Promoting self-kindness and mindfulness strategies in family counseling can enhance the psychological flexibility necessary to manage a quickly changing environment (Weaver & Swank, 2021).

Limitations

This study has a few limitations. First, with data collected within a single timepoint and the correlational nature of the study, we are not able to establish temporal precedence. As such, we cannot make conclusions about the direction of the relations among the variables. Second, the alphas for the subscales of the SCS are relatively low. This scale is well established and have shown excellent validity and reliability estimates in previous studies (Neff, 2003), but it is possible that the low alphas were due to having fewer items on each subscale (4-5 items; Peterson, 1994). Also, we suspect that the timing and context of the pandemic when data was collected may have some influence on the participants’ responses on the self-compassion items. Lastly, as the data was collected during the early phase of the pandemic, we cannot generalize the findings and it is plausible that the responses on the measures we administered may have been different as the COVID-19 cases increased or decreased in different parts of the country.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: We thank the research support from the College of Education and Human Sciences at South Dakota State University (SDSU) and USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture (NIFA), Multi-state (#1016891) and Hatch (#1016822) project..

ORCID iDs: Aileen S. Garcia https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5623-5867

Erin S. Lavender-Stott https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4189-1121

References

- Abidin R. R. (1992). The determinants of parenting behavior. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 21(4), 407–412. 10.1207/s15374424jccp2104_12 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ackerman N. J. (1984). A theory of family systems. Gardner Press. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association (2020). Stress in America 2020: Stress in the time of COVID-19, Vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Arnetz J. E., Goetz C. M., Arnetz B. B., Arble E. (2020). Nurse reports of stressful situations during the COVID-19 pandemic: Qualitative analysis of survey responses. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(21), 1–12. 10.3390/ijerph17218126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beer M., Ward L., Moar K. (2013). The relationship between mindful parenting and distress in parents of children with an Autism Spectrum Disorder. Mindfulness, 4(2), 102–112. 10.1007/s12671-012-0192-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berry J. O., Jones W. H. (1995). The parental stress scale: Initial psychometric evidence. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 12(3), 463–472. 10.1177/0265407595123009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berryhill M. B., Harless C., Kean P. (2018). College student cohesive-flexible family functioning and mental health: Examining gender differences and the mediation effects of positive family communication and self-compassion. The Family Journal: Counseling and Therapy for Couples and Families, 26(4), 422–432. 10.1177/1066480718807411 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley R. H., Corwyn R. F. (2007). Externalizing problems in fifth grade: Relations with productive activity, maternal sensitivity, and harsh parenting from infancy through middle childhood. Developmental Psychology, 43(6), 1390–1401. 10.1037/0012-1649.43.6.1390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown S. M., Doom J. R., Lechuga-Pena S., Watamura S. E., Koppels T. (2020). Stress and parenting during the global COVID-19 pandemic. Child Abuse & Neglect, 110(January), 104699. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2021). CDC COVID Data Tracker.https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#cases_casesper100klast7days.

- Chung G., Lanier P., Wong P. Y. J. (2020). Mediating effects of parental stress on harsh parenting and parent-child relationship during coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic in Singapore. Journal of Family Violence, 1–12. 10.1007/s10896-020-00200-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger R. D., Conger K. J. (2002). Resilience in Midwestern families: Selected findings from the first decade of a prospective, longitudinal study. Journal of Marriage and Family, 64(2), 361–373. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2002.00361.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crnic K. A., Low C. (1995). Everyday stresses of parenting. In Bornstein M. H. (Ed.), Handbook of parenting (Vol. 4, pp. 243–268). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. 10.1038/clpt.1994.88 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Deater-Deckard K., Chen N., El Mallah S. (2017). Parenting stress. 10.1093/OBO/9780199828340-0142 [DOI]

- Faso D. J., Neal-Beevers A. R., Carlson C. L. (2013). Vicarious futurity, hope, and well-being in parents of children with autism spectrum disorder. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 7(2), 288–297. 10.1016/j.rasd.2012.08.014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Felder J. N., Lennon E., Shea K., Kripke K., Dimidjian S. (2016). Role of self-compassion in psychological well-being among perinatal women. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 19(4), 687–690. 10.1007/s00737-016-0628-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulton C. L. (2018). Self-compassion as a mediator of mindfulness and compassion for others. Counseling & Values, 63(1), 45–56. 10.1002/cvj.12072 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gadermann A. C., Thomson K. C., Richardson C. G., Gagné M., Mcauliffe C., Hirani S., Jenkins E. (2021). Examining the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on family mental health in Canada: Findings from a national cross-sectional study. BMJ Open, 11(1), 1–11. 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-042871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Germer C., Neff K. (2019). Teaching the mindful self-compassion program: A guide for professionals. The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg A. E., McCormick N., Virginia H. (2021). Parenting in a pandemic: Work–family arrangements, well-being, and intimate relationships among adoptive parents. Family Relations, 70(1), 7–25. 10.1111/fare.12528 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gouveia M. J., Carona C., Canavarro M. C., Moreira H. (2016). Self-compassion and dispositional mindfulness are associated with parenting styles and parenting stress: The mediating role of mindful parenting. Mindfulness, 7(3), 700–712. 10.1007/s12671-016-0507-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Horiuchi S., Shinohara R., Otawa S., Akiyama Y., Ooka T., Kojima R., Yokomichi H., Miyake K., Yamagata Z. (2020). Caregivers’ mental distress and child health during the COVID-19 outbreak in Japan. PLoS ONE, 15(12 December), 1–13. 10.1371/journal.pone.0243702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horton T. V., Wallander J. L. (2001). Hope and social support as resilience factors against psychological distress of mothers who care for children with chronic physical conditions. Rehabilitation Psychology, 46(4), 382. 10.1037/0090-5550.46.4.382 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson A. P., Choi J. K., Preston K. S. J. (2019). Harsh parenting and black boys’ behavior problems: Single mothers’ parenting stress and nonresident fathers’ involvement. Family Relations, 68(4), 436–449. 10.1111/fare.12373 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Janssen L. H. C., Kullberg M. L., Verkuil B., van Zwieten N., Wever M. C. M., van Houtum L. A. E. M., Wentholt W. G. M., Elzinga B. M. (2020). Does the COVID-19 pandemic impact parents’ and adolescents’ well-being? An EMA-study on daily affect and parenting. PLoS ONE, 15(10 October), 1–22. 10.1371/journal.pone.0240962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jefferson F. A., Shire A., McAloon J. (2020). Parenting self-compassion: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Mindfulness, 11(2), 2067–2088. 10.1007/s12671-020-01401-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jose P. E. (2013). ModGraph-I: A programme to compute cell means for the graphical display of moderational analyses: The internet version, version 3.0. Victoria University of Wellington. https://psychology.victoria.ac.nz/modgraph/. [Google Scholar]

- Kerr M. E., Bowen M. (1988). Family evaluation: An approach based on Bowen theory. Norton & Company. [Google Scholar]

- Lee C. S. (2016). The roles of hope and growth mind-set in the relationship between mothers’ parenting stress and children’s well-being. Indian Journal of Science and Technology, 9(47). 10.17485/ijst/2015/v8i1/108371 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S. J., Ward K. P., Chang O. D., Downing K. M. (2021). Parenting activities and the transition to home-based education during the COVID-19 pandemic. Children and Youth Services Review, 122, 105585. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez S. J. (2013). Making hope happen: Create the future you want for yourself and others. Simon and Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Luetke M., Hensel D., Herbenick D., Rosenberg M. (2020). Romantic relationship conflict due to the COVID-19 pandemic and changes in intimate and sexual behaviors in a nationally representative sample of American adults. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy, 46(8), 747–762. 10.1080/0092623X.2020.1810185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mednick L., Cogen F., Henderson C., Rohrbeck C. A., Kitessa D., Streisand R. (2007). Hope more, worry less: Hope as a potential resilience factor in mothers of very young children with type 1 diabetes. Children's Healthcare, 36(4), 385–396. 10.1080/02739610701601403 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mikolajczak M., Roskam I. (2020). Parental burnout: Moving the focus from children to parents. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 2020(174), 7–13. 10.1002/cad.20376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller J. J., Cooley M. E., Mihalec-Adkins B. P. (2020). Examining the impact of COVID-19 on parental stress: A study of foster parents. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 2020, 1–10. 10.1007/s10560-020-00725-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreira H., Carona C., Silva N., Nunes J., Canavarro M. C. (2016). Exploring the link between maternal attachment-related anxiety and avoidance and mindful parenting: The mediating role of self-compassion. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 89(4), 369–384. 10.1111/papt.12082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreira H., Gouveia M. J., Carona C., Silva N., Canavarro M. C. (2015). Maternal attachment and children’s quality of life: The mediating role of self-compassion and parenting stress. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24(8), 2332–2344. 10.1007/s10826-014-0036-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morris A. S., Robinson L. R., Hays-Grudo J., Claussen A. H., Hartwig S. A., Treat A. E. (2017). Targeting parenting in early childhood: A public health approach to improve outcomes for children living in poverty. Child Development, 88(2), 388–397. 10.1111/cdev.12743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neff K. D. (2003). The development and validation of a scale to measure self-compassion. Self and Identity, 2(2), 223–250. 10.1080/15298860390209035 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Neff K. D. (2016). The self-compassion scale is a valid and theoretically coherent measure of self-compassion. Mindfulness, 7(1), 264–274. 10.1007/s12671-015-0479-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Neff K. D., Faso D. J. (2015). Self-compassion and well-being in parents of children with autism. Mindfulness, 6(4), 938–947. 10.1007/s12671-014-0359-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Neff K. D., Kirkpatrick K. L., Rude S. S. (2007). Self-compassion and adaptive psychological functioning. Journal of Research in Personality, 41(2007), 139–154. 10.1016/j.jrp.2006.03.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Olson D. H. (2000). Circumflex model of marital and family systems. Journal of Family Therapy, 22(2), 144–167. 10.1111/1467-6427.00144 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson R. A. (1994). A meta-analysis of Cronbach’s coefficient alpha. Journal of Consumer Research, 21(2), 381–391. 10.1086/209405 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Psychogiou L., Legge K., Parry E., Mann J., Nath S., Ford T., Kuyken W. (2016). Self-compassion and parenting in mothers and fathers with depression. Mindfulness, 7(4), 896–908. 10.1007/s12671-016-0528-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneewind K. A., Reeb C., Saravo B. (2012). Sources of parental stress, dysfunctional parenting, children’s behaviour problems and buffering conditions in dual-earner families. Family Science, 3(2), 126–134. 10.1080/19424620.2012.707819 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schrank B., Stanghellini G., Slade M. (2008). Hope in psychiatry: A review of the literature. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 118(6), 421–433. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2008.01271.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel R. D., Germer C. K. (2012). Introduction. In Germer C. K., Siegel R. D. (Eds.), Wisdom and compassion in psychotherapy: Deepening mindfulness in clinical practice (pp. 1–6). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder C. R., Harris C., Anderson J. R., Holleran S. A., Irving L. M., Sigmon S. T., Yoshinobu L., Gibb J., Langelle C., Harney P. (1991). The will and the ways: Development and validation of an individual-differences measure of hope. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60(4), 570–585. 10.1037/0022-3514.60.4.570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder C. R., Sympson S. C., Ybasco F. C., Borders T. F., Babyak M. A., Higgins R. L. (1996). Development and validation of the State Hope Scale. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70(2), 321–335. 10.1037/0022-3514.70.2.321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solem M.-B., Christophersen K.-A., Martinussen M. (2011). Predicting parenting stress: Children’s behavioral problems and parents’ coping. Infant and Child Development, 20(2), 162–180. 10.1002/icd [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Todorov N., Sherman K. A., Kilby C. J., & Breast Cancer Network Australia. (2019). Self-compassion and hope in the context of body image disturbance and distress in breast cancer survivors. Psycho-oncology, 28(10), 2025–2032. 10.1002/pon.5187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umphrey L. R., Sherblom J. C. (2014). The relationship of hope to self-compassion, relational social skill, communication apprehension, and life satisfaction. International Journal of Wellbeing, 4(2), 1–18. 10.5502/ijw.v4i2.1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Umphrey L. R., Sherblom J. C., Swiatkowski P. (2020). Relationship of self-compassion, hope, and emotional control to perceived burdensomeness, thwarted belongingness, and suicidal ideation. Crisis: The Journal of Crisis Intervention and Suicide Prevention, 42(2), 121–127. 10.1027/0227-5910/a000697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warfield M. E. (2005). Family and work predictors of parenting role stress among two-earner families of children with disabilities. Infant and Child Development, 14(2), 155–176. 10.1002/icd [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver J. L., Swank J. M. (2021). Parents’ lived experiences with the COVID-19 pandemic. Family Journal, 29(2), 136–142. 10.1177/1066480720969194 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Webster-Stratton C. (1989). The relationship of marital support, conflict, and divorce to parent perceptions, behaviors, and childhood conduct problems. Journal of Marriage and Family, 51(2), 417–430. 10.2307/352504 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Whitchurch G. G., Constantine L. L. (1993). Systems theory. In Boss P., Doherty W., LaRossa R., Schumm W., Steinmetz S. (Eds.), Sourcebook of family theories and methods: A contextual approach (pp. 325–352). Plenum. [Google Scholar]

- Williams M. J., Dalgleish T., Karl A., Kuyken W. (2014). Examining the factor structures of the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire and the Self-Compassion Scale. Psychological Assessment, 26(2), 407–418. 10.1037/a0035566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y., Zhang M., Kou Y. (2016). Self-compassion and life satisfaction: The mediating role of hope. Personality and Individual Differences, 98, 91–95. 10.1016/j.paid.2016.03.086 [DOI] [Google Scholar]