Abstract

Introduction

To report two cases of Acute Macular Neuroretinopathy (AMN) presented as the first stage of SARS-CoV-2 infection in two European countries during the third wave of pandemic viral infection in the early months of 2021.

Observations

A unilateral case of type 1 AMN in a man and a bilateral case of type 2 AMN in an otherwise heathy patients were reported. Sudden onset of paracentral scotoma characterized the cases with no systemic symptoms. Structural optical coherence tomography (OCT) shows multifocal middle and inner retinal hyperreflective infarctions. OCT-Angiography showed the presence of hypoperfusion of the deep capillary plexus (DCP) corresponding to the hyperreflective lesions visible on structural OCT, confirming the diagnosis.

Conclusions and importance

Type 1 and type 2 AMN may be the first stage of SARS-CoV-2 infection. We suggest testing all patients with AMN for SARS-CoV-2. In our cases, the natural history of AMN associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection was similar to already described cases of AMN.

Keywords: Acute Macular Neuroretinopathy, paracentral acute middle maculopathy, SARS-CoV-2 infection, optical coherence tomography angiography, optical coherence tomography angiography

Introduction

Acute macular neuroretinopathy (AMN), described by Bos and Deutman in 1975,1,2 is a rare disease of the outer retina predominantly affecting young-to-middle-aged healthy females and characterized by the sudden appearance of one or more paracentral scotomas.

With the advent of more sophisticated retinal imaging modalities, two types of AMN were classified by Sarraf et al. in 2013, depending on the structural OCT location of the lesion: either above (type 1) or below (type 2) the outer plexiform layer (OPL). 3 Type 1 AMN is also called paracentral acute middle maculopathy (PAMM). 3

While the exact pathophysiology of AMN is still unknown, it is thought to be due to an ischemic insult at the level of the deep retinal capillary plexus (DCP). 4 AMN was reported to occur after the consumption of oral contraceptives, 2 post-viral illness, trauma, anemia, thrombocytopenia, and also after routine influenza vaccination.1,4,5

For over a year now, the new severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) pandemic has drastically changed peoples’ lives across the globe, and a multitude of systemic and organ-specific manifestations have been associated with infection by the virus. 6 Regarding the retina, these appear in the form of microvascular, ischemic or inflammatory events.7,8 In addition, these microvascular alterations seem to occur even in the absence of overt retinal pathology, as demonstrated by decreased vessel density in optical coherence tomography angiography (OCTA) in patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection.9–11

Here, we describe here a series of three eyes of two patients with AMN concomitant to SARS-Cov-2 infection, along with their multimodal imaging characteristics, including OCTA.

Observations:

Case #1

A 27-year-old Caucasian man presented with an acute onset of unilateral dyschromatopsia and paracentral scotoma in his left eye (LE), with no other systemic symptoms. His past medical history was unremarkable: he takes no medication, and he denied any eye trauma. The patient, a bar worker, had had several interpersonal contacts without personal protective equipment (PPI) over the preceding weeks. At presentation, best corrected visual acuity (BCVA) was 20/20 in both eyes.

An ophthalmic examination consisting of fundoscopy, OCT, and OCTA was performed (Figure 1). Fundus examination showed a subtle yellowish perifoveal halo in the perifoveal area of the LE. OCTA showed the presence of hypoperfusion of the DCP corresponding to the hyperreflective lesions on structural OCT (Figure 1 a and b, d and e).

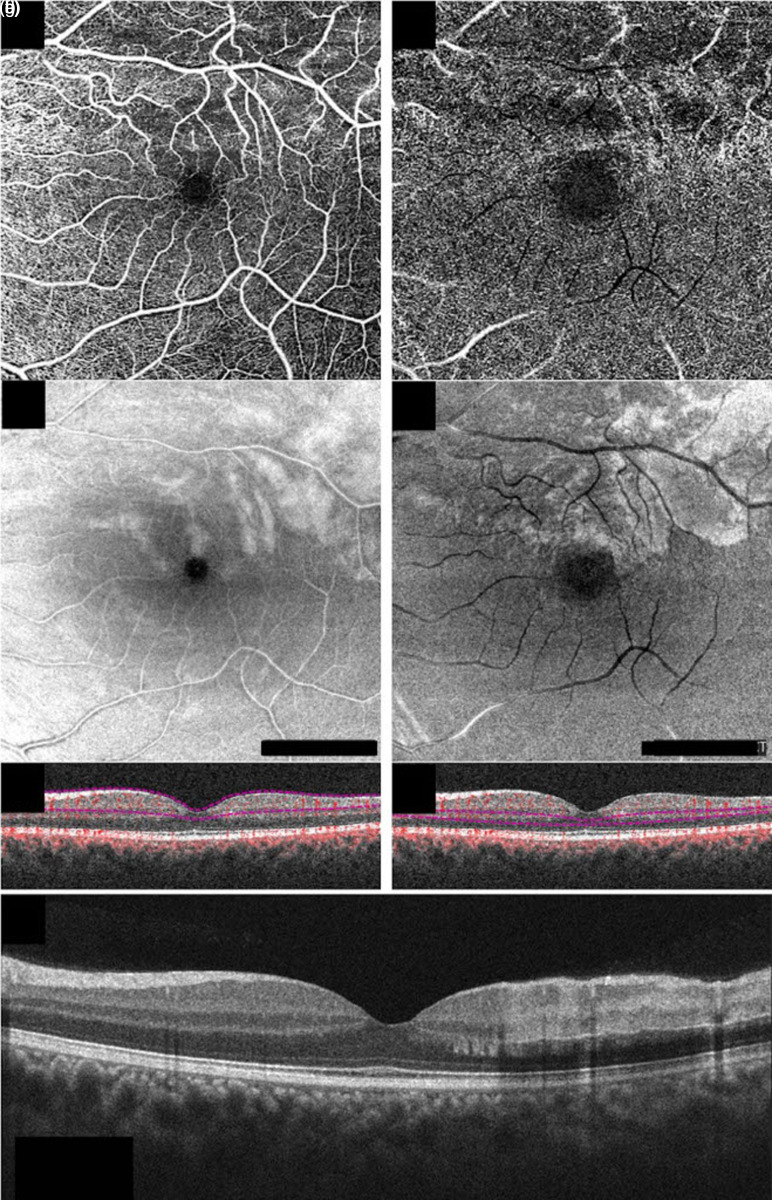

Figure 1.

Structural optical coherence tomography (OCT) and OCT-angiography (OCTA) of the left eye in case #1 at the baseline En-face 6 × 6 OCTA, en-face structural OCT, and b-scan OCT with flow of the superficial capillary plexus (a, b, and c, respectively) and the deep capillary plexus (d, e, and f, respectively) showing the presence of hypoperfusion especially in the deep capillary plexus (d), corresponding to the lesions on en-face structural OCT (e). Structural b-scan OCT passing through the fovea (g), showing the presence of multifocal middle and inner retinal hyperreflective infarctions (Angioplex cirrus 5000, Carl Zeiss Meditec, Inc, Dublin, California, USA).

Structural OCT revealed the presence of multifocal middle and inner retinal hyperreflective infarctions (Figure 1 c, f, g).

A diagnosis of type 1 AMN (i.e. PAMM) was performed on the basis of pathognomonic OCTA and OCT lesions. On the advice of the ophthalmologist, the patient performed blood tests and a complete screening for coagulation abnormalities, along with testing for SARS-CoV-2 infection. Laboratory investigations revealed slight elevation of liver enzymes and hypertriglyceridemia, compatible with moderate alcohol consumption. The C-reactive protein level and platelets count were slightly elevated. Coagulation testing detected markedly decreased free protein S levels (28.3%, normal laboratory range >72.2%). COVID-19 infection was confirmed by PCR testing with nasopharyngeal swab and progressed in a paucisymptomatic form.

The patient was re-evaluated two weeks later, and his symptoms partially resolved without any treatment (Figure 2).

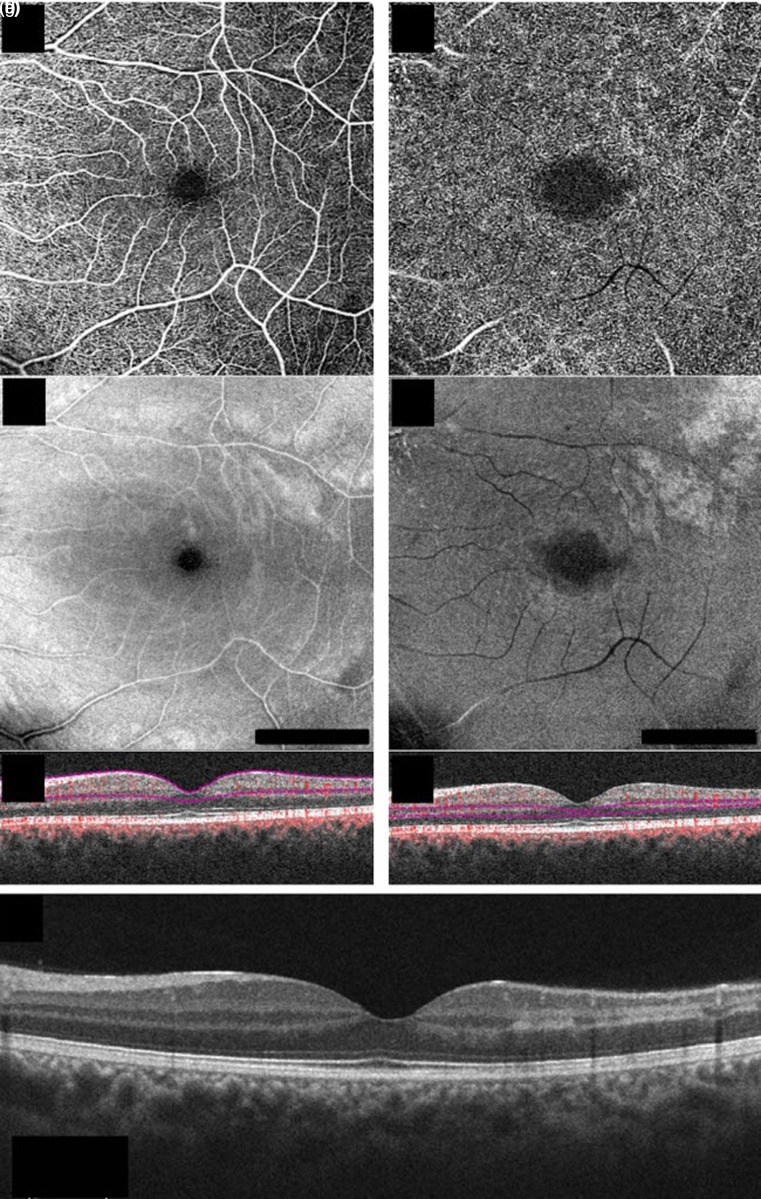

Figure 2.

Structural optical coherence tomography (OCT) and OCT-angiography (OCTA) of the left eye in case #1 at 2-week follow-up. En-face 6 × 6 OCTA, en-face structural OCT, and b-scan OCT with flow of the superficial capillary plexus (a, b, and c, respectively) and the deep capillary plexus (d, e, and f, respectively), showing the improvement of hypoperfusion in both plexuses. Structural b-scan OCT passing through the fovea (g) showing improved multifocal middle and inner retinal hyperreflective infarctions (Angioplex cirrus 5000, Carl Zeiss Meditec, Inc, Dublin, California, USA).

Case #2

A 37 -year-old healthy female was referred in April 2021 for classic clinical manifestation of AMN (paracentral scotoma). As pro forma, a PCR test for SARS-CoV-2 was performed. At first ophthalmological consultation, patient's BCVA was 20/20 in both eyes with hyperopic correction.

The patient was healthy with no previous significant systemic or ophthalmic history. Anterior segment examination and tonometry were normal.

Color confocal retinal image (CRI) shows an alternated foveal reflex without hemorrhages (Figure 3 a and b). Structural OCT disclosed features of AMN in both eyes, such as hyper-reflective infarction that involved the OPL and outer nuclear layer (ONL), with associated disruption of the inner/outer segment (IS/OS) and outer segment/retinal pigment epithelium (OS/RPE) layers consistent with type 2 AMN (Figure 3 c and d). In order to limit contact while awaiting the PCR results, first author decided not to perform visual field or other ancillary tests.

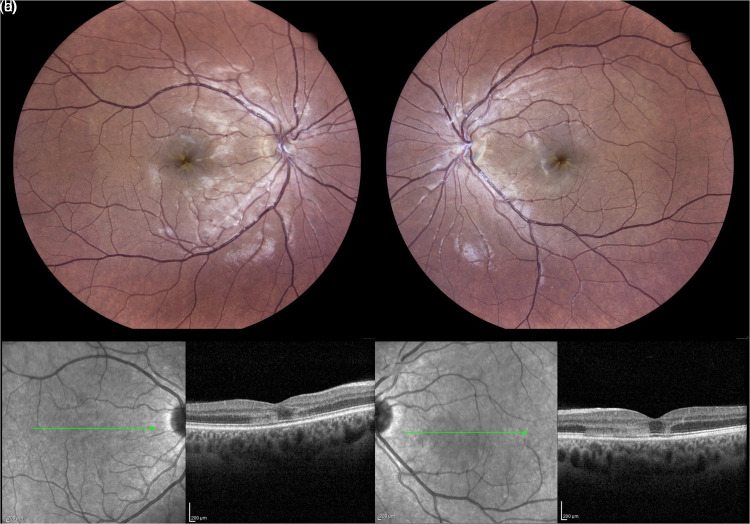

Figure 3.

Multimodal imaging of case #2 at baseline. Color confocal retinal image (CRI) (EIDON, Centervue, Italy) shows an alternated foveal reflex without hemorrhages in both eyes (a-b). Structural optical coherence tomography (OCT) disclosed features of Acute Macular Neuroretinopathy (AMN) in both eyes, such as hyper-reflective infarction involving the outer plexiform layer (OPL) and the outer nuclear layer (ONL) with associated disruption of the inner/outer segment (IS/OS) and outer segment/retinal pigment epithelium (OS/RPE) layers consistent with a type 2 Acute Macular Neuropathy (AMN) (c-d). (Heidelberg Engineering, Heidelberg, Germany).

Patient was followed weekly. PCR for SARS-CoV-2 disclosure for active SARS-CoV-2 infection revealed she had few systemic symptoms. At last follow-up (month one), PCR for SARS-CoV-2 was negative, BCVA was stable at 20/20 in both eyes, and scotoma r was reduced. CRI results were unmarkable, and OCT shows resolution of infarction, localized atrophy of ONL and a compromised OS/RPE (Figure 4 a to d). OCTA of the DCP shows a parafoveal flow void (Figure 4 e and f).

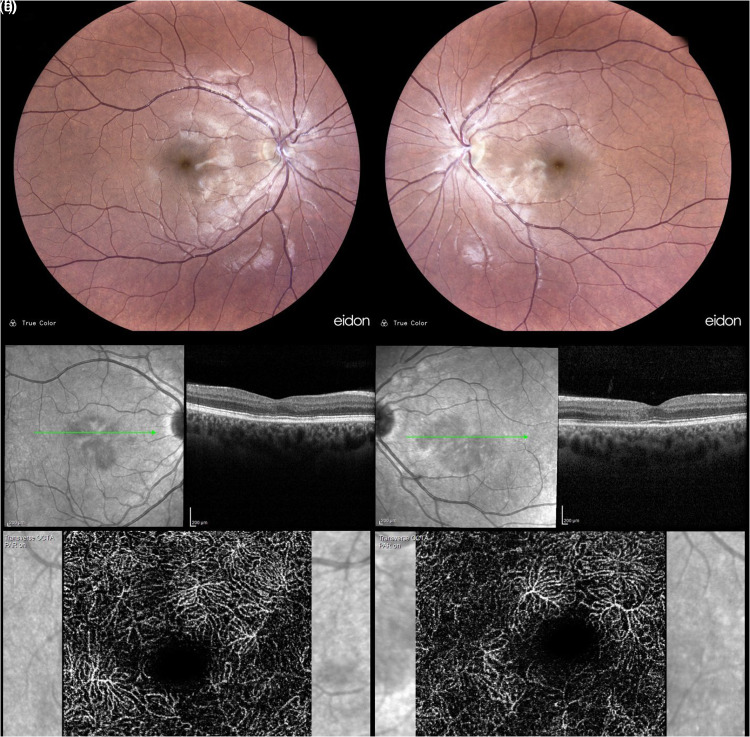

Figure 4.

Multimodal imaging of case #2 at month 1 follow-up. Color confocal retinal image (CRI) (EIDON, Centervue, Italy) returned unmarkable (a-b), and OCT shows resolution of infarction, localized atrophy of ONL, and a compromised OS/RPE (c-d). OCTA of the DCP shows a parafoveal flow void (e-f) Spectralis HRA + OCT (Heidelberg Engineering, Heidelberg, Germany).

Discussion

In this report, we observed that two cases of AMN (type 1 in one eye and type 2 in two eyes) are the first stage of SARS-CoV-2 infection. The report suggests an association between this rare retinal inflammation and the prodromal phase of SARS-CoV-2 infection.

To date, only a few cases of association between AMN and SARS-CoV-2 have been published. Two of them referred to elderly patients (70 years old).12,13 Another report concerned two younger patients; 14 however, the above-mentioned cases report AMN following COVID infection and symptomatology, while we reported two cases in which the AMN represent a prodromal manifestation of SARS-CoV-2 infection.

The rationale of the association between AMN and SARS-CoV-2 infection arises from the fact that AMN has already been associated with viral infections5–15) and SARS-CoV-2 has already been associated with retinal microvascular alteration.16,17 An original article has recently suggested that Protein S deficiency (as found in case #1) could be capable of increasing susceptibility to thrombosis. 18 Unfortunately, protein S levels are not available for case #2. Another hypothesis has been proposed by Padhy et al. concerning the role of the D-dimer. 19 This hypothesis needs confirmation by further studies. Moreover, the natural history of our patients did not differ from other reports regarding the association between AMN and viral infections.

Our report has several limitations, the first of which is linked to the very small study population. Although AMN is a rare retinal inflammation, SARS-CoV-2 infection has been diagnosed in several million patients, creating an unlikely statistical association. Second, concerning the visual symptoms: in order to avoid potential virus spread, we did not perform visual field tests to confirm the symptoms. Third, concerning visual prognosis, we report two cases with a one-month follow-up, but late damages could appear in the future. However, the OCT-A images showing hypoperfusion of both plexuses support the hypothesis of ischemic lesion already described lesions associated with AMN. Although retinal vascular events are relatively rare in young patients, there is no definitive evidence that the observations in this report are linked to SARS-CoV-2. Given the high incidence of SARS-CoV-2 during the pandemic, a report of only 2 cases of retinal ischemia without providing definitive evidence to link both findings remain speculative. Moreover, in the recently published manuscript by Fonollosa et al., 20 concerning retinal vascular occlusions in thirty-nine patients, the authors underlined that they did not find unquestionable link between SARS-CoV-2 infection and their cases. Lastly, we cannot be sure that prodromal symptoms such as headaches are not already present in the patients, as they are quite frequent among workers. Finally, we described only speculative association between AMN and SARS-CoV-2 and not a certain link.

In conclusion, we report three cases of AMN (type 1 in one eye and type 2 in two eyes) during the first stage of SARS-CoV-2 infection in order to emphasize that any apparently healthy patient should test for SARS-CoV-2 if they present type 1 or type 2 AMN.

Vittorio Capuano, Paolo Forte, Riccardo Sacconi, Alexandra Miere, Carl-Joe MEHANNA, Caterina Barone: none.

Eric H. Souied is a consultant for: Allergan Inc (Irvine, California,USA), Bausch And Lomb (Rochester, New York, USA), Bayer Shering-Pharma (Berlin, Germany), Novartis (Basel, Switzerland).

Francesco Bandello is a consultant for: Alcon (Fort Worth,Texas,USA), Alimera Sciences (Alpharetta, Georgia, USA), Allergan Inc (Irvine, California,USA), Farmila-Thea (Clermont-Ferrand, France), Bayer Shering-Pharma (Berlin, Germany), Bausch And Lomb (Rochester, New York, USA), Genentech (San Francisco, California, USA), Hoffmann-La-Roche (Basel, Switzerland), Novagali Pharma (Évry, France), Novartis (Basel, Switzerland), Sanofi-Aventis (Paris, France), Thrombogenics (Heverlee,Belgium), Zeiss (Dublin, USA).

Footnotes

Consent: Informed consent was obtained from the patients for publication of related image and case description.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs: Paolo Forte https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1762-3506

Riccardo Sacconi https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2891-2012

Alexandra Miere https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4123-8210

Carl-Joe Mehanna https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6758-7972

Francesco Bandello https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3238-9682

Giuseppe Querques https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3292-9581

References

- 1.Bhavsar KV, Lin S, Rahimy E, et al. Acute macular neuroretinopathy: a comprehensive review of the literature. Surv Ophthalmol 2016; 61: 538–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bos PJM, Deutman AF. Acute macular neuroretinopathy. Am J Ophthalmol 1975; 80: 573–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sarraf D, Rahimy E, Fawzi AA, et al. Paracentral acute middle maculopathy: a new variant of acute macular neuroretinopathy associated with retinal capillary ischemia. JAMA Ophthalmol 2013; 131: 1275–1287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu JC, Nesper PL, Fawzi AA, et al. Acute macular neuroretinopathy associated with influenza vaccination with decreased flow at the deep capillary plexus on OCT angiography. Am J Ophthalmol Case Reports 2018; 10: 96–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shah P, Zaveri JS, Haddock LJ. Acute macular neuroretinopathy following the administration of an influenza vaccination. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging Retina 2018; 49: e165–e168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ramos-Casals M, Brito-Zerón P, Mariette X. Systemic and organ-specific immune-related manifestations of COVID-19. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2021: 6–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zapata MÁ, Banderas García S, Sánchez-Moltalvá A, et al. Retinal microvascular abnormalities in patients after COVID-19 depending on disease severity. Br J Ophthalmol 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sim R, Cheung G, Ting D, et al. Retinal microvascular signs in COVID-19. Br J Ophthalmol 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Turker IC, Dogan CU, Guven Det al. et al. Optical coherence tomography angiography findings in patients with COVID-19. Can J Ophthalmol 2021; 56: 83–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hazar L, Karahan M, Vural E, et al. Macular vessel density in patients recovered from COVID 19. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther 2021; 34: 102267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abrishami M, Emamverdian Z, Shoeibi N, et al. Optical coherence tomography angiography analysis of the retina in patients recovered from COVID-19: a case-control study. Can J Ophthalmol 2021; 56: 24–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aidar MN, Gomes TM, de Almeida MZH, et al. Low visual acuity due to acute macular neuroretinopathy associated with COVID-19: a case report. Am J Case Rep 2021; 22:e931169. Published 2021 Apr 30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Preti RC, Zacharias LC, Cunha LP, et al. Acute macular neuroretinopathy as the presenting manifestation of COVID-19 infection. Retin Cases Brief Rep 2021. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Virgo J, Mohamed M. Paracentral acute middle maculopathy and acute macular neuroretinopathy following SARS-CoV-2 infection. Eye (Lond )2020; 34: 2352–2353. Epub 2020 Jul 3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shields RA, Oska SR, Farley ND, et al. Influenza-Induced acute macular neuroretinopathy with cerebral involvement in a ten-year-old boy. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging Retina 2020; 51: 293–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gonzalez-Lopez JJ, Felix Espinar B, Ye-Zhu C. Symptomatic retinal microangiophaty in a patient with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): single case report. Ocul Immunol Inflamm 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.González-Zamora J, Bilbao-Malavé V, Gándara E, et al. Retinal microvascular impairment in COVID-19 bilateral pneumonia assessed by optical coherence tomography angiography. Biomedicines 2021; 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lemke G, Silverman GJ. Blood clots and TAM receptor signaling in COVID-19 pathogenesis. Nat Rev Immunol 2020; 20: 395–396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Padhy SK, Dcruz RP, Kelgaonkar A. Paracentral acute middle maculopathy following SARS-CoV-2 infection: the D-dimer hypothesis. BMJ Case Rep 2021; 14: e242043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fonollosa A, Hernandez-Rodriguez J, Cuadros C, et al. Characterizing COVID-19-related retinal vascular occlusions a case series and review of the literature. Retina Journal 2022; 42(3): 465–475 doi: 10.1097/IAE.0000000000003327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]