Summary

Background

Mental health is a public health issue for European young people, with great heterogeneity in resource allocation. Representative population-based studies are needed. The Global Burden of Disease (GBD) Study 2019 provides internationally comparable information on trends in the health status of populations and changes in the leading causes of disease burden over time.

Methods

Prevalence, incidence, Years Lived with Disability (YLDs) and Years of Life Lost (YLLs) from mental disorders (MDs), substance use disorders (SUDs) and self-harm were estimated for young people aged 10-24 years in 31 European countries. Rates per 100,000 population, percentage changes in 1990-2019, 95% Uncertainty Intervals (UIs), and correlations with Sociodemographic Index (SDI), were estimated.

Findings

In 2019, rates per 100,000 population were 16,983 (95% UI 12,823 – 21,630) for MDs, 3,891 (3,020 - 4,905) for SUDs, and 89·1 (63·8 - 123·1) for self-harm. In terms of disability, anxiety contributed to 647·3 (432–912·3) YLDs, while in terms of premature death, self-harm contributed to 319·6 (248·9–412·8) YLLs, per 100,000 population. Over the 30 years studied, YLDs increased in eating disorders (14·9%;9·4-20·1) and drug use disorders (16·9%;8·9-26·3), and decreased in idiopathic developmental intellectual disability (–29·1%;23·8-38·5). YLLs decreased in self-harm (–27·9%;38·3-18·7). Variations were found by sex, age-group and country. The burden of SUDs and self-harm was higher in countries with lower SDI, MDs were associated with SUDs.

Interpretation

Mental health conditions represent an important burden among young people living in Europe. National policies should strengthen mental health, with a specific focus on young people.

Funding

The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation

Keywords: Young people, Mental health, Mental disorders, Self-harm, Substance use, Europe

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

The Global Burden of Disease Study (GBD) 2019 estimates on prevalence, incidence, mortality, Years Lived with Disability (YLDs), Years of Life Lost (YLLs) and disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) due to 369 diseases and injuries for 204 countries and territories became available in 2020. To complement GBD data, PubMed and Web of Science were searched for published papers on mental disorders in Europe and Google for gray literature in the public domain, as well as references in these papers and reports by November 2021, using the search terms “anxiety”, “alcohol use”, “attention-deficit disorder with hyperactivity”, “autism spectrum disorders”, “bipolar”, “burden”, “conduct disorder”, “depressive”,”depression”, “drug use”, “eating disorders”, ‘’epidemiology’’, “Europe”, “intellectual disability”, “mental disorders”, “mental health”, “prevalence”, “schizophrenia”, “self-harm”, “substance use”, “suicide”, “suicide attempt” and “trends”, without language or publication date restrictions. This literature was used as source of information for the references quoted in the study. Moreover, GBD 2019 estimates for mental disorders (MDs), substance use disorders (SUDs) and self-harm in 31 European countries (the 28 European Union (EU) countries [United Kingdom was still part of EU], plus Iceland, Norway, and Switzerland), sorted by country, sex and age groups (10-14, 15-19 and 20-24) were derived from 528 references. Earlier GBD studies have described mental health at a global level, and several national studies have described mental health in European countries. It is well recognized that mental health problems have increased in younger age groups. There was no previous comprehensive account of mental disorders in Europe, showing the development over time in different age groups, and in different parts of Europe. Self-harm has previously been analysed as an ‘injury’, and is included here as a mental disorder.

Added value of this study

This report describes the burden of mental conditions (i.e. MDs, SUDs and self-harm) in young people living in Europe, covering a 30-year period during which Europe faced profound political, social and demographic changes.It provides an overview of data sources used for epidemiological analyses. It describes variations in the prevalence of MDs and SUDs between 31 European countries, showing a lower burden of MDs in central and eastern Europe. Overall, the greatest burden is due to anxiety and depression. The report also describes changes in burden since 1990, with an increased burden due to disability from eating disorders and drug use disorders, and a decrease of idiopathic developmental intellectual disability, and alcohol use disorders. The burden of self-harm also decreased. The burden of SUDs and self-harm is higher in countries with lower development status as measured by the sociodemographic index (SDI). MDs are positively associated with SUDs.

Implications of all the available evidence

Mental health conditions in Europe represented a major health burden for younger people in the period 1990 to 2019, in terms of both disability and premature deaths. Given that these conditions often predict same or worse conditions in adulthood, and given that the estimated direct and indirect costs of these disorders are higher than those of chronic somatic diseases, our findings emphasise the need for policies to strengthen mental health in future years, with a specific focus on young people. The reported estimates of the burden and changes over time may be used by stakeholders to inform health planning. They also serve as an important point of reference when the full public health impact of the COVID-19 pandemic is assessed, in particularly in terms of the burden the pandemic has had on the mental health of young people in Europe.

Alt-text: Unlabelled box

Introduction

Mental health conditions (i.e. mental disorders (MDs), substance use disorders (SUDs) and self-harm behaviours) are important causes of disease burden among young people in high-income countries,1,2 with conduct disorder, depression and anxiety disorder ranking among the top ten causes of years lived with disability (YLDs).1,3 The importance of mental health as a public health issue among young people is not reflected in the allocated resources,4 and many mental health conditions remain undetected and unmanaged for a long time.5 European countries show a high heterogeneity in resource allocation for child and adolescent mental health services (CAMHS).6 Further, only 70% of European countries have an official national adolescent mental health policy.6

Mental health receives in general limited research investment and political support in comparison with other non-communicable diseases (NCDs),7 and the need for a greater investment in mental care and a more equal distribution of funding across European Union (EU) countries has been highlighted.8 Further, there is a need for representative population-based studies using defined diagnostic criteria and standardized methods to assess MDs among European young people. Such studies are crucial to determine the true magnitude of the problem as well as to identify risk and protective factors to inform early interventions aimed at preventing co-morbidity and consequent long-term disability.4,6,9 Finally, countries in EU and Schengen area differ in terms of socio-economic development. Studies have shown higher burden of mental health conditions in high income countries than in middle and low income countries.10 However, as all these countries in Europe are classified as high income countries, the sociodemographic index (SDI) may be a better measure used to compare levels of disease burden by socioeconomic development in this region.

The Global Burden of Disease (GBD) Study aims to provide information on global trends in the health status of populations and changes in the leading causes of disease burden over time by assessing prevalence, incidence, premature deaths and non-fatal health health loss or disability.3 GBD allows for a comparison of cause-specific disease burden over time and by country through the standardisation of data management and methods.

Since an increasing prevalence of mental conditions (i.e. MDs, alcohol and substance use disorders [SUDs] and self-harm) in young people is observed across several European countries,11 a deeper understanding of the disease burden associated with these disorders is necessary to inform future health planning for different countries’ health systems. Although the hypothesis of a rise of MDs related to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has not yet been sufficiently investigated, it has been claimed that an increase in mental distress may result in a rise of mental conditions over the next years.12 Although it is not clear to what extent data and methodology available in the GBD will be able to quantify the burden of mental conditions due to the COVID-19 outbreak,13 a pre-pandemic baseline on mental conditions among young people in Europe may be a useful point of reference when the full public health impact of the pandemic is assessed.

The aims of this study are: 1) to describe the prevalence, incidence, YLDs and YLLs of different MDs, SUDs and self-harm in males and females aged 10–14, 15-19 and 20-24 years, from 1990 to 2019 among 31 European countries; 2) to describe trends in the prevalence and incidence of these disorders across European countries over this 30-year period;and 3) to correlate the prevalence and incidence of these disorders with the SDI of each European country.

This manuscript was produced as part of the GBD Collaborator Network and in accordance with the GBD Protocol.

Methods

The Global Burden of Disease Study produces annual estimates on prevalence, incidence and mortality for 369 diseases and injuries. Each update incorporates new data and methodological improvements to provide stakeholders with the most up-to-date information for resource allocation decisions and are compliant with the Guidelines for Accurate and Transparent Health Estimates Reporting.14

The present study employed estimates from GBD 2019, which are available on the Global Health Data Exchange (GHDx).15 These estimates supersede those from previous rounds of GBD, since the estimates for the whole time series are updated on the basis of addition of new data and change in methods, where appropriate, at each iteration of the GBD study.3 Methods for the generation of GBD 2019 estimates are described in detail elsewhere,3 while the methodology for estimating the burden due to mental health conditions is briefly summarised here.

We provided results from 1990 to 2019 for 31 European countries: the 28 EU countries (the UK was still part of EU), plus Iceland, Norway and Switzerland, as part of Schengen area. The catchment population comprised young people between 10 and 24 years old,16 with a total number of 85 million subjects in 2019.

Data sources

The estimates were based on data on incidence and prevalence identified through systematic searches of published and unpublished documents, survey microdata, administrative records of health encounters, registries, and disease surveillance system that are catalogued in the Global Health Data Exchange website (http://ghdx.healthdata.org). We summarized these data sources for the 31 countries of interest, related to MDs, SUDs and self-harm in the 10-24 age range, in Appendix (Overview on data coverage).

GBD measures

We included the following measures of disease burden: prevalence (MDs and SUDs), incidence (self-harm,) YLDs, and YLLs. YLDs are years lived with disability (in which the disability equates to a fraction of a year lived in full health) and are the product of the prevalence and the disability weight of that condition. YLLs are years of life lost due to premature death, calculated as the difference between the corresponding standard life expectancy for that person's age and sex, and the age of actual death. Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) are the sum of YLDs and YLLs. DALYs were used only to provide the fraction of YLDs and YLLs for each disorder.

Prevalence was derived from estimates of point prevalence for all MDs and SUDs, with the exception of bipolar disorders, where one-year prevalence was applied.17 We used prevalence estimates for all conditions which usually last more than six months. This involved also SUDs, even if a small degree of them also contributed also to premature deaths. We used incidence estimates for self-harm, since the great majority of the burden due to self-harm was represented by YLLs due to fatal self-harm.18

Estimation of prevalence and incidence

Prevalence and incidence were modelled using DisMod-MR 2.1, a Bayesian meta-regression tool. Epidemiological data from different sources were pooled by DisMod-MR 2.1 with the goal of producing internally consistent estimates of prevalence, incidence, remission, and excess mortality by age, sex, location, and year.

Estimation of severity

Proportions of severity were calculated to reflect the different levels of disability, or sequelae, associated with a determinate disorder, eg, mild, moderate, and severe presentations. Severity proportions, as shown elsewhere,10 were applied to the total prevalent cases estimated by DisMod-MR 2.1 to obtain prevalence estimates for each level of severity.

Disability-weights

As described in detail in other studies based on GBD 2019,3,19 disability weights by condition were applied to estimate YLDs. These have been calculated through a series of severity splits, which definie the sequelae of a health condition as asymptomatic, mild, moderate, and severe. Disability weights derived from different international surveys, where a scale ranging from perfect health (0) to death (1) was used, adding also population health equivalence questions that compared the lifesaving benefits and the prevention programmes for several health states. The analysis of the surveys served for the relative position of health states to each other, while the population health equivalence questions were used to assess those relative positions as values on a scale ranging from 0 to 1. More information on the sequela-specific health state descriptions and on the disability weights analysis are described elsewhere.10

Adjustment for comorbidity

A simulation method based on simulated populations of individuals by location, age, sex, and year, was used to adjust for comorbidity, since the burden attributable to each cause in GBD was estimated separately. Individuals in each population were exposed to the independent probability of having a combination of different sequelae in GBD 2019. A comorbidity correction was then used to estimate the difference between the average disability weight of individuals experiencing one sequela and the multiplicatively combined disability weights of those experiencing more sequelae. Specific YLDs per location, age, sex, and year applied the average comorbidity correction calculated for each sequela.10

Uncertainty intervals

Uncertainty intervals (UIs) were used to describe the point estimates of uncertainty from model specification, stochastic variation, and measurement bias. UIs are based on 1000 draws from the posterior distribution of estimates. The point estimate is defined by the mean of the draws, while the the 95% UIs is represented by the 2·5th and 97·5th percentiles ranked estimates from the drawns.

GBD causes hierarchy

In GBD 2019, diseases and injuries and causes of death, were aggregated in three Level 1 causes (communicable, maternal, neonatal, and nutritional conditions; NCDs; and injuries), 22 Level 2 causes, 174 Level 3 causes, and 301 Level 4 causes.3

In this study, we included Level 2 (MDs and SUDs) and Level 3 causes, as follows:

-

•

MDs: anxiety disorders, attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), autism spectrum disorder (ASD), bipolar disorder, conduct disorder, depressive disorders, eating disorders, idiopathic developmental intellectual disability (IDID), schizophrenia, other mental disorders;

-

•

SUDs: alcohol use disorders, drug use disorders;

-

•

Self-harm.

Only for MDs, we also aggregate disorders as follows, to describing prevalence rates among the 31 countries of interest:

-

a)

Common MDs20: depressive and anxiety disorders;

-

b)

Severe MDs21: schizophrenia and bipolar disorders;

-

c)

“Other” MDs: Eating disorders, ASD, ADHD, Conduct disorders, IDID, Other mental disorders.

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV-TR) or the International Classification of Diseases – Tenth revision (ICD-10) criteria were used for definition of cases,19 as they were used by the majority of mental health surveys included in the Appendix.

Socio-demographic Index

the. SDI is a composite indicator of development status, built as the geometric mean of 0 to 1 indices of total fertility rate in women younger than 25 years, mean education for the population aged 15 years and older, and lag-distributed income per capita.3 We used the SDI for each of the 31 countries of this study.

Data presentation

For each country, cause and year, we report count, age rates per 100,000 population for age subgroups, and percentage changes from 1990 to 2019 for estimates of prevalence, incidence, YLDs, and YLLs, with 95% UIs,3. The Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) provided aggregated estimates for all 31 countries combined, since the standard GBD aggregate estimates are for the EU, and exclude the other Schengen area countries (i.e. Iceland, Norway and Switzerland) .. Results are presented by sex and age subgroups (10-14; 15-19 and 20-24 years). YLLs were calculated only for self-harm, eating disorders, alcohol use disorders and substance use disorders since these are the only causes considered causes of death in the WHO/ICD-system (https://www.who.int/standards/classifications).

We also reported the percentages of YLDs and YLLs of MDs, SUDs and self-harm in the 10-24 age groups compared to the all-causes GBD in the 31 European countries.

In addition, we performed Spearman rank-correlations to study the relation between SDI and prevalence rates of MDs and SUDs, and incidence rates of self-harm. We set P-value <0·05 as the threshold of statistical significance. These analyses were conducted with Stata/BE 17.0 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, USA).

Role of the funding source

The funder of the study had no role in study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation, or writing of the report. The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility to submit for publication.

Results

Prevalence of MDs, SUDs and incidence of self-harm

In 2019, there were 13·6 million (95% UI 15·5–11·9) young people in the 31 European countries with MDs, 3·2 (2·6–4·0) million with SUDs, and 75,770 (59,091–95,206) self-harmed. In terms of rates per 100,000 population, they were 16,983 (12,823 – 21,630), 3,891 (3,020 - 4,905), and 89·1 (63·8 - 123·1), respectively.

As shown in Table 1, the most prevalent condition in 2019 was anxiety disorders, in terms of both count (5·6 million;3·8-7·7 million cases) and rates (6·6; 4·9-8·4 cases per 100,000 population), with an increase of 4·7% (1·1–8·6) from 1990. A decrease of 7·5% (2·9–13·6) was found for alcohol use disorders from 1990. Self-harm decreased by almost 40% (36·3–42·6).

Table 1.

Prevalence, Incidence, Years Lived with Disability (YLDs) and Years’ Life Lost (YLLs) for mental disorders, substance abuse and self-harm in European Union, Iceland, Norway and Switzerland, years 1990-2019, both sexes, age 10-24, counts, rates and percentage change over time.

| Counts (95% Uncertainty Intervals) |

Rates per 100,000 population (95% Uncertainty Intervals) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1990 | 2019 | 1990 | 2019 | Change % | ||

| Mental disorders | ||||||

| Anxiety disorders | Prevalence | 6,659,301 (4,624,216; 9,783,510) | 5,582,658 (3,844,784; 7,748,341) | 6,155 (4,537; 8,109) | 6,567 (4,973; 8,360) | 4·7 (1·1; 8·6) |

| YLDs | 655,912 (399,848; 1,007,683) | 550,220 (333,975; 845,550) | 606·2 (392·3; 880·7) | 647·3 (432; 912·3) | 4·8 (0·9; 9) | |

| ADHD | Prevalence | 2,660,206 (1,820,396; 3,761,625) | 2,256,716 (1,526,534; 3,243,148) | 2,459 (1,786; 3,288) | 2,655 (1,975; 3,499) | 5·8 (1·3; 10·8) |

| YLDs | 32,448 (17364; 57,009) | 27,541 (14,629; 48,869) | 30 (17·0; 49·8) | 32·4 (18·9; 52·7) | 5·9 (0·4; 11·7) | |

| ASD | Prevalence | 612,121 (508,524; 731,129) | 506,530 (421,652; 602,444) | 566 (499; 639) | 596 (545; 650) | 3·4 (2·2; 4·6) |

| YLDs | 94,732 (61,013; 138,483) | 78,390 (50,592; 114,642) | 87·6 (59·9; 121) | 92·2 (65·4;123·7) | 3·4 (0·6; 6·1) | |

| Bipolar disorder | Prevalence | 883,032 (613,263; 1,212,260) | 718,481 (500,256; 831,600) | 816 (602; 1,060) | 845 (647; 1,061) | 1·6 (0·8; 4·5) |

| YLDs | 196,567 (103,423; 323,729) | 159,975 (84,636; 264,969) | 181·7 (101·5; 282·9) | 188·2 (109·5; 285·9) | 1·7 (-1·9; 5·4) | |

| Conduct disorders | Prevalence | 1,989,600 (1,381,925; 2,709,809) | 1,641,386 (1,140,564; 2,236,415) | 1,839 (1,356; 2,368) | 1,931 (1,475; 2,413) | 3·0 (2·0; 4·1) |

| YLDs | 241,387 (130,636; 393,196) | 199,195 (107,979; 324,790) | 223·1 (128·2; 343·7) | 234·3 (139·7; 350·4) | 3·1 (0·9; 5·3) | |

| Depressive disorders | Prevalence | 3,382,030 (2,530,390; 4,388,585) | 2,619,276 (1,883,469; 3,512,140) | 3,126 (2,482; 3,836) | 3,081 (2,436; 3,789) | -3·4 (-2·4; 8·8) |

| YLDs | 626,008 (386,014; 953,873) | 484,289 (289,832; 756,723) | 578·6 (378·7; 833·7) | 569·7 (374·9; 816·4) | -3·6 (-9·7; 3) | |

| Eating disorders | Prevalence | 646,946 (418,130; 961,896) | 595,413 (380,504; 894,360) | 598 (410; 841) | 700 (492; 965) | 14·9 (9·4; 20) |

| YLDs | 138,467 (75,902; 229,997) | 127,494 (69,672; 213,850) | 128·0 (74·5; 201) | 150·0 (90·1; 230·7) | 14·9 (9·4; 20·1) | |

| YLLs | 1031 (670; 1617) | 1075 (616; 1848) | 1·0 (0·6; 1·6) | 1·3 (0·7; 2·4) | 31·2 (2·0; 63·3) | |

| IDID | Prevalence | 789,007 (365,767; 1,212,592) | 438,934 (165,902; 713,992) | 729 (359; 1,060) | 516 (215; 770) | -31·5 (-43·3; -25·6) |

| YLDs | 35,359 (4,814; 61,565) | 20,263 (7,379; 36,522) | 32·7 (14·5; 53·8) | 23·8 (9·5; 39·4) | -29·1 (–38·5; 23·8) | |

| Schizophrenia | Prevalence | 100,919 (65,486; 148,235) | 76,806 (49,490; 113,744) | 93 (64; 130) | 90 (64; 123) | -5 (-7·47; -2·66) |

| YLDs | 67,121 (37,773;107,565) | 40,977 (21,084; 67,728) | 62 (37·1; 94) | 60·3 (37·3; 89·3) | -4·7 (-11·6; 1·5) | |

| Other mental disorders | Prevalence | 674,330 (424,980; 958,463) | 531,531 (335,250; 754,731) | 623 (417; 838) | 625 (434; 814) | -1·5 (-1·9; -1·1) |

| YLDs | 51,989 (26,609; 85,710) | 51,223 (28,859; 82,807) | 48·1 (26·1; 74·9) | 48·2 (27·3; 73·1) | -1·5 (-6·7; 3·7) | |

| Substance use disorders | ||||||

| Alcohol use disorders | Prevalence | 1,993,616 (1,261,281; 2,907,7949 | 1,480,042 (912,167; 2,196,529) | 1,843 (1,237; 2,541) | 1,741 (1,180; 2,370) | -7·5 (-13·6; -2·9) |

| YLDs | 204,105 (113,367; 335,338) | 151,473 (82,495; 254,273) | 188·6 (111·2; 293·1) | 178·2 (106·7; 274·3) | -7·6 (-13·8; -2·4) | |

| YLLs | 13,700 (11,175; 16676) | 7891 (5929; 10,313) | 12·7 (9·8; 16·4) | 9·3 (6·4; 13·3) | -37·5 (-41·3; -32·9) | |

| Drug use disorders | Prevalence | 2,309,892 (1,729,613; 3,077,292) | 1,827,533 (1,422,606; 2,350,350) | 2,135 2,690; 1,697 | 2,150 2,536; 1,840 | -0·9 (-7·5; 5·6) |

| YLDs | 229,235 (148,067; 329,472) | 214,408 (138,831; 307,728) | 211·9 (145·3; 288) | 252·2 (179·6; 332) | 16·9 (8·9; 26·3) | |

| YLLs | 83,639 (68028; 102,329) | 56,961 (42,081; 76,209) | 77·3 (59·5; 100·4) | 67·0 (45·4; 98·6) | -14·8 (-24·2; -2·8) | |

| Self-harm | ||||||

| Incidence | 124,715 (100,589; 152,872) | 75,770 (59,091; 95,206) | 115·3 (87·9; 150·0) | 89·1 (63·8; 123·1) | -39·3 (-42·6; -36·3) | |

| YLDs | 4,617 (3,017; 6,591) | 2,621 (1,696; 3,756) | 4·3 (3·0; 5·8) | 3·1 (2·2; 4·1) | -29·1 (-32·0; -26·0) | |

| YLLs | 543,528 (491816; 598905) | 271,675 (230,719; 319,118) | 502·4 (429·9; 587·6) | 319·6 (248·9; 412·8) | -27·9 (-38·3; -18·7) | |

YLDs, years lived with a disability; ADHD, Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder; ASD Autism spectrum disorders; IDID Idiopathic developmental intellectual disability.

Substantial differences in prevalence rates were observed in relation to sex. Anxiety, depressive and eating disorders were more prevalent among females than males, while the opposite was observed for ADHD, ASD, conduct disorders and“other MDs”, as well as alcohol and drug use disorders (Supplement Tables 1). In terms of age-groups, anxiety disorders, ADHD and conduct disorderswere the most prevalent disorders among males aged 10 to 14 years, while anxiety disorders had the highest prevalence among females in this age group. Anxiety disorders remained the most prevalent disorder both among aged 15 to 19 and 20 to 24 years and among males aged 15 to 19 . The most prevalent disorders among males aged 20 to 24 years were anxiety, alcohol and drug use (Supplement tables 2, 3 and 4).

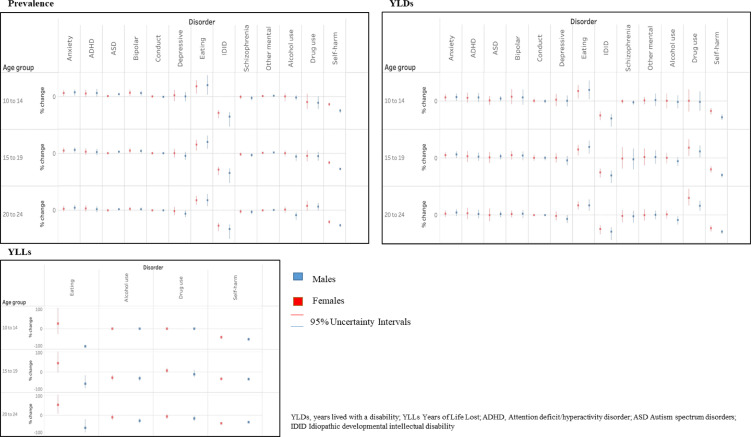

The largest changes in prevalence over time from 1990 were observed for eating disorders (+14·9%; 9·4–20), and IDID (–31·5%; 25·6–43·3) in both sexes combined (Table 1). Similar tendency in change of prevalence was observed when stratified by sex and age-groups (Figure 3, Supplement tables 2, 3 and 4).

Figure 3.

Prevalence for mental disorders, substance use disorders, and incidence for self-harm in European Union, Iceland, Norway and Switzerland, years 1990-2019, males and females, age 10-14, 15-19, 20-24 percentage change over time.

Prevalence of MDs, SUDs and incidence of self-harm by country

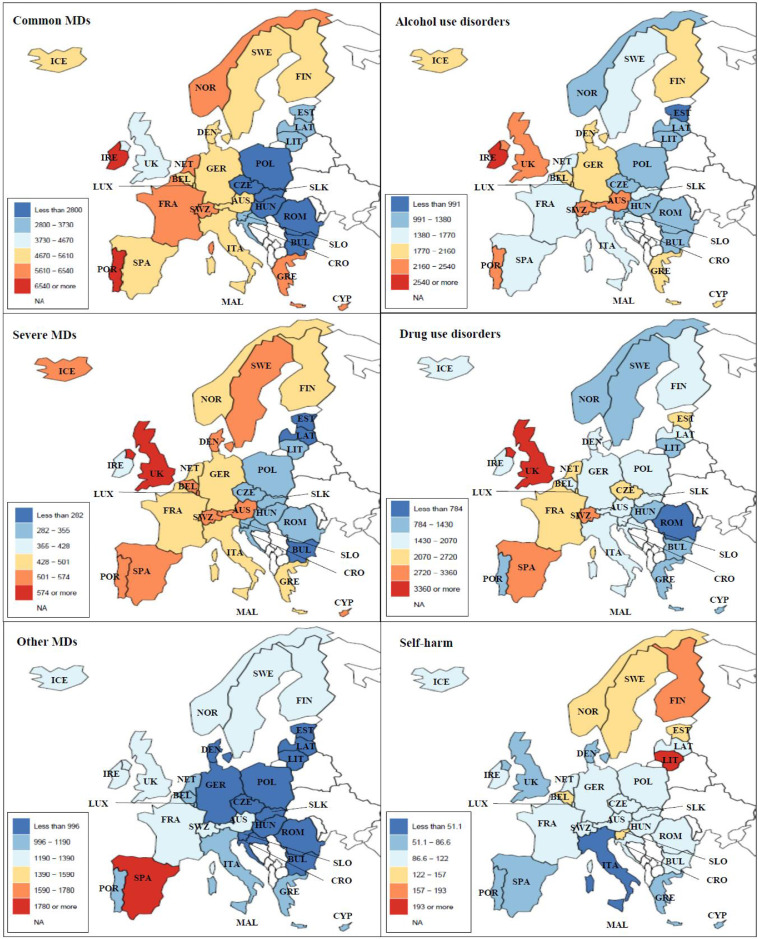

Central and eastern Europe (i.e. Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania. Slovakia and Slovenia) were generally characterized by lower prevalence rates of common and severe MDs and alcohol use disorders compared to the rest of Europe, while rates were more heterogeneous for the other conditions (Figure 1). During the 30-year period, higher MD rates were observed in Portugal and in Spain (around 20,000 per 100,000), while higher SUD rates were observed in Switzerland and UK (5500 or more per 100,000) (Supplement table 5 and 6). As summarized in Supplement table 7, the highest incidence rates of self-harm were in Lithuania (from 227·8 per 100,000 in 1990 to 207·1 in 2019) and in Finland (from 266·2 per 100,000 in 1990 to 185·8 in 2019).

Figure 1.

Prevalence per 100,000 population aged 10-24 years of common, severe and other mental disorders (MDs), alcohol and drug use disorders, and incidence rate of self-harm in 31 European countries, both sexes, age 10-24, year 2019.

Common MDs: anxiety and depressive disorders; Severe MDs: schizophrenia and bipolar disorder; Other MDs: eating disorders, attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder, autism spectrum disorder, conduct disorders, idiopathic developmental intellectual disability, other mental disorders.

YLDs of MDs, SUDs and self-harm

MDs were the leading cause of YLDs in all the 31 countries in 2019 (Supplement table 8), with anxiety and depressive disorders ranking between the first and the fourth position in each country (Supplement table 9).

In 2019, anxiety and depressive disorders were the leading causes of YLDs among mental health conditions, contributing to a total count of 550,220 (333,975 - 845,550) and 484,289 (289,832-756,723) YLDs, respectively. The greatest increases from 1990 were observed for eating disorders (+15%; 9·4–20·1), and for drug use (+17%; 8·9–26·3), while IDID (–29%; 23·8–38·5) and self-harm (-29·1; 32·0 - 26·0) greatly decreased (Table 1).

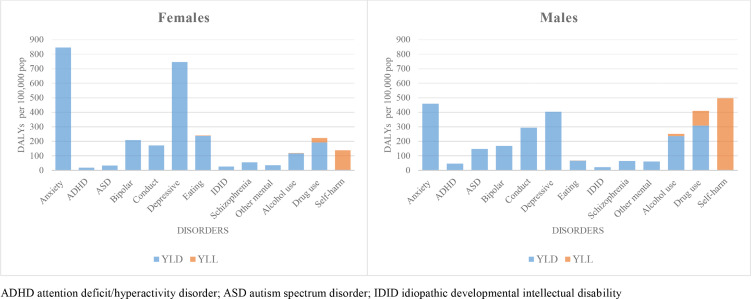

When comparing sexes, YLD rates in males were 4·5 times higher yhan in females for ASD and more than twice as high for ADHD while YLD rates in females were 3·5 times higher than in males for eating disorders and nearly twice as high for anxiety and depressive disorders. YLD rates for alcohol and drug use disorders were more than 1·5 times higher in males compared to females (Figure 2, Supplement table 1).

Figure 2.

Disability Adjusted Life Years (DALYs) divided in Years Lived with Disability (YLDs) and Years of Life Lost (YLLs) for mental disorders, substance use disorders and self-harm in 31 European countries, females and males, age 10-24, year 2019.

With regard to age groups, the highest YLD rates in 2019 in females aged 10 to 14 years were for anxiety disorders, and in males were for conduct and anxiety disorders. In the older age-groups, anxiety and depressive disorders had the highest level of YLD rates in both sexes, although they were higher among females. YLDs for alcohol and drug use disorders were quite low until 14 years old, and due to the age of onset used to model prevalence, they increased substantially from age 15, and had equivalently high levels of YLD rates of anxiety and depressive disorders in males aged 20 to 24 years (Supplement Tables 2, 3 and 4).

The largest increase in YLD rates from 1990 were found for eating disorders in both sexes and in all age groups, and for drug disorders from 15 years old. YLD rates due to IDID and self-harm decreased significantly in both sexes and in all age groups (Figure 3).

YLLs of eating disorders, SUDs and self-harm

Self-harm ranked as the first to the third cause of YLLs in all 31 countries in 2019 (Supplement table 10).

Among the mental health conditions, self-harm was the main contributor to YLL rates per 100,000 population (319·6 (248·9–412·8) in 2019) (Table 1), with rates almost four-times higher in males compared to females in 2019 (Figure 2; Supplement table 1). Drug use disorders were the second highest contributor of YLLs, especially in males (Table 1; Supplement table 1).

With regard to age groups, the highest YLL rates per 100,000 population in 2019 were found in males aged 20-24 years for self-harm (937·9; 863·5 - 1,019·3), and for drug use disorders (228·2; 184·3- 281·2)(Supplement Table 4).

YLL rates decreased from 1990 in all conditions considered (Table 1), except eating disorders in females, which increased by 42·6% (9·7-80·2) (Supplement table 1).

Correlation between SDI and prevalence rates of MDs, SUDs and self-harm, and between prevalence rates of MDs and SUDs

All 31 countries were included in high or high-middle SDI global quintiles. SDI varied from 0·59 (Portugal) to 0·82 (Norway) in 1990, and from 0·72 (Portugal) to 0·93 (Switzerland) in 2019. As shown in Table 2, SUDs and self-harm showed a significant correlation with growing SDI in 1990 which was still significant in 2019. Prevalence rates of MDs were significantly associated with those of SUDs in both years.

Table 2.

Spearman rank-correlation (coefficients and relative P-values) among prevalence of mental disorders, substance use disorders, incidence of self-harm and Social Demographic Index in the European Union, Iceland, Norway and Switzerland, years 1990-2019, both sexes, age 10-24. Significant results are highlighted in bold.

| 1990 |

2019 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spearman rank-correlation coefficient (P-value) | Spearman rank-correlation coefficient (P-value) | |||||

| MDs | SUDs | Self-harm | MDs | SUDs | Self-harm | |

| MDs | 1·0 | 1·0 | ||||

| SUDs | 0·54 (0·001) | 1·0 | 0·47 (0·008) | 1·0 | ||

| Self-harm | - 0·04 (0·80) | - 0·03 (0·86) | 1·0 | - 0·30 (0·10) | - 0·13 (0·47) | 1·0 |

| SDI | 0·16 (0·38) | 0·41 (0·02) | 0·37 (0·04) | 0·25 (0·17) | 0·35 (0·05) | 0·39 (0·03) |

MDs Mental disorders; SUDs Substance use disorders; SDI Socio Demographic Index.

Among countries with higher SDI, UK showed the highest level of SUDs, while Lithuania showed the greatest incidence of self-harm (Supplement figure 1 and 2). Regarding the correlation between SUDs and MDs, Central and Eastern Europe showed lower levels of MDs and somewhat of SUDs, while Spain was characterized by higher levels of both (Supplement Figure 3).

Discussion

Almost 17 million young people (19·8%) in these 31 European countries had a mental or substance use disorder in 2019. In total, mental conditions contributed to more than 1 million YLDs in 2019, and were the leading cause of disability among young people in most European countries. Prevalence of MDs increased from 1990 to 2019, while incidence of self-harm decreased by more than 20% in both sexes. Among MDs, the greatest increase was observed for eating disorders (15%), ADHD (6%) and anxiety (5%).

In the period 1990 to 2019, YLD rates due to eating disorders and drug use disorders increased in both sexes from age 10 and 15, respectively, while YLDs rates due to IDID decreased in both sexes and all age-groups. There were considerable sex differences: male/female ratio for ASD was 4·5:1, and almost 2:1 for ADHD and SUDs; conversely it was 1:3·5 for eating disorders and almost 1:2 for anxiety and depressive disorders.

Self-harm has been a leading cause of YLLs among yound people in most European countries since 1990, although a decrease of almost 30% was observed in the 30-year period.

Mental disorders

Previous findings at the global level indicated a heavy burden of MDs and subsequent disability in the young population.1,2,5,22 Given the high prevalence of common MDs and their burden in terms of disability in adulthood,9 these disorders are a key target for health policy and programme planning in the European agenda.11 There was a particularly strong increase in the occurrence of eating disorders, both in males and females across all age groups. Although it is uncertain to what extent these increasing rates were due a true rise in prevalence rather than changes in diagnostic practices or improved detection, it has been suggested that many individuals suffering from eating disorders still remain untreated in Europe.23 ADHD showed a 6% increase in prevalence from 1990. Although this may also be indication of an improvement in the detection of ADHD cases, care for this disorder should be enhanced, given that more than 60% of children diagnosed with ADHD have symptoms as adults.24 We found a 30% decrease of IDID, in terms of both prevalence and disability, which reflects the decrease in occurrence of intellectual disability observed in children under 5 years from 1990 to 2016 in Europe, probably related to an improvement in early detection and interventions among prematurely-born children.25

Emerging evidence has shown that socio-economic deprivation is an important determinant of many mental disorders such as schizophrenia, anxiety and depression, substance use disorders, and self-harm.11,26 In our study Portugal, having the lowest SDI during the 30-year period, also had the highest burden of MDs, perhaps implying some influence of lower socioeconomic conditions on MDs. In contrast, Central and Eastern European countries, where socioeconomic conditions improved from 1990,27 were characterized by lower MDs rates during this period. However, we found no correlation between MDs and SDI at country level in the present study. European countries, however, are all characterised by high SDI, which may have hindered the identification of significant differences between countries. Strong correlations were found in studies based on specific geographical areas with important differences in SDI, with high-income countries generally characterised by a higher burden due to MDs, in particular depression and anxiety.10,19,28 Other explanations for the heterogeneity across countries may be linked to the high degree of variations in epidemiological data, as acknowledged in our overview on data coverage. Estimates for Central and Eastern Europe were based on a mean of only 2·5 publications per country, which may have led to an underestimation of MDs in these countries.

Substance use disorders

Alcohol and drug use disorders represent a major burden on young people living in Europe, among the highest in the world.2 YLDs due to drug use disorders increased in both sexes from 15 years old. Cannabis use is widespread among European young people, along with the use of cocaine and ecstasy, leading to detrimental effects on their mental and physical health.11 Europe has high death rates caused by opioid dependence,29 which often starts during adolescence. Drug use was also responsible for almost 60,000 YLLs in 2019. Moreover, the burden attributable to SUDs represent an additional risk for other health problems later in life, such as injuries, self-harm, and somatic diseases. Although Central and Eastern Europe had the highest alcohol and drug attributable burdens30 a decreasing trend of alcohol use disorders in these countries was observed during the study period. This decline is in line with previous observations from European countries till 2014.31 It might be related to the implementation of evidence based public health policies, such as limiting the access to alcohol by raising the minimum legal age for drinking, increasing prices, or regulating advertisement in the media.11,31 However, there is still a high heterogeneity in policy measures,32 and countries with higher SDI have a greater burden.30

Self-harm

Self-harm was the third leading cause of DALYs among people aged 10-24 years worldwide in 2019 3 and it is among the five leading causes of young people's mortality in Europe.2,33 Many young people with suicidal behaviours are still not detected by health services,34 and only half of EU countries have agreements between school and health services to facilitate referrals to CAMHS and official guidelines for referring patients from primary care.6 However, we observed a drop in incidence and YLLs, in line with the one-third decrease in suicide rates between 2000 and 2017, previously described.11 This may reflect a positive effect of suicide prevention strategies or an improvement of health of the population 33, as well as an enhancement in help-seeking and service availability for adolescents. 6 34 High differences among countries suggest that self-harm is due to a complex interplay of specific factors related to each country, including social, economic, and cultural factors, and a different distribution of MDs and SUDs.33

Correlation between MDs and SUDs

It was somewhat expected to observe a significant correlation between MDs and SUDs in all 31 European countries. As previously highlighted,5,11,18,35,36 there is a strong correlation between MDs and SUDs in young people. A person-centred care approach to young people's needs might better manage the complex interactions of clinical and social factors underlying mental conditions, including substance use and self harm. Services for mental care for young people in Europe often do not match the epidemiological burden of these conditions,6 lack in specific tailored care pathways based on specific psychosocial needs, and lack in the connection with adult mental health services37 and social services.32

Strengths and limitations

The main strength of this study is giving an extensive account of mental health conditions in young people living in Europe, covering 30 years during which Europe faced profound political, social and demographic changes. This is also the first study analysing the extent of the burden of these conditions in young people in Europe. Previous studies at global level did not analyse specifically these disorders in young people, or were limited to MDs,3 not including SUDs and self-harm.10 Additionally, it provides an overview on data sources used for epidemiological analyses. A limitation is the lack of relevant data in some countries, particularly in Central and Eastern Europe, even though all these 31 countries are among those with the largest amount of data compared to other areas of the world.9,38

Other limitations should also be acknowledged. First, the study suffers from the general limitations of GBD studies, such as uncertainties in the determination and classification of non-fatal disorders, deriving from different data sources, and the uncertainty of some estimates, reflected by the width of the 95% UIs for certain disorders. Second, an underestimation of the true effect of mental health conditions may be due to the fact that self-harm is coded in GBD under injuries, while it is largely linked to MDs and SUDs. We included self-harm in our analyses, although it was not possible to calculate the attributable burden of suicide, which could have increased the overall burden of MDs and SUDs.18,39 This calculation is underway by IHME, using GBD 2020 estimates.10 However, we provided the correlation of self-harm with MDs and SUDs in our analyses, without finding significant correlations. This lack of association is consistent with recent findings that the majority of young people who self-harm do not have a mental disorder.40 Third, estimates on personality disorders are included in the broad group of other MDs, due to limited informing prevalence estimates.3 However, it would be suitable to include them in future GBD estimates, given a lifetime prevalence of personality disorder in the EU of more than four million people.9 Finally, SDI was chosen as a summary measure of a geography's socio-demographic development, while more precise measures could be used, such as the Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD), which includes several domains.41 However, IMD was not available for most of the countries of interest, and SDI is commonly used in GBD studies on large areas.3

Conclusions

The burden of mental and drug use disorders slightly increased from 1990, while alcohol use disorders and especially self-harm decreased among young people in Europe. It is concerning that all these conditions still represent a major health burden, especially in terms of disability, but also in terms of premature deaths.36 Given that young people's mental disorders often predict the same or worse conditions in adulthood,2,5 and a shift towards health loss due to NCDs has been observed,1 our findings support the assertion that mental conditions should be considered a core health challenge of the 21st century.9 Further, the estimated direct and indirect costs of these disorders are higher than those of chronic somatic diseases.7 There is a need to capture data more comprehensively to truly understand the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in Europe,11,12 since this study demonstrated a possible underestimation of the actual burden of mental conditions, owing to the paucity of data in Central and Eastern European countries, and the GBD classification of self-harm. Given all these factors, national policies should provide evidence-based preventive initiatives and accessible treatment for mental health disorders in young people.10,30,33,42

Declaration of interests

T W Bärnighausen reports Research grants from the European Union (Horizon 2020 and EIT Health), German Research Foundation (DFG), US National Institutes of Health, German Ministry of Education and Research, Alexander von Humboldt Foundation, Else-Kröner-Fresenius-Foundation, Wellcome Trust, Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, KfW, UNAIDS, and WHO; consulting fees from KfW on the OSCAR initiative in Vietnam; participation on a Data Safety Monitoring Board or Advisory Board with NIH-funded study “Healthy Options” as Chair, Data Safety and Monitoring Board (DSMB) for the German National Committee on the “Future of Public Health Research and Education”, Chair of the scientific advisory board to the EDCTP Evaluation, Member of the UNAIDS Evaluation Expert Advisory Committee, National Institutes of Health Study Section Member on Population and Public Health Approaches to HIV/AIDS (PPAH), US National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine's Committee for the “Evaluation of Human Resources for Health in the Republic of Rwanda under the President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR)”, University of Pennsylvania Population Aging Research Center (PARC) External Advisory Board Member; leadership or fiduciary role in other board, society, committee or advocacy group, paid or unpaid as Co-chair of the Global Health Hub Germany, initiated by the German Ministry of Health); all outside the submitted work. J S Chandan reports grants or contracts from the National Institute of Health Research and has been awarded funds from the NIHR and the Youth Endowment Fund, outside the submitted work. J J Jozwiak reports payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speaker's bureaus, manuscript writing or educational events from Teva, Amgen, Synexus, Boehringer Ingelheim, ALAB Laboratories, and Zentiva, all as personal fees and outside the submitted work. S V Katikireddi reports support for the present manuscript form Medical Research Council and the Scottish Government Chief Scientist Office as funding to their institution. J H Kauppila reports grants or contracts from The Finnish Cancer Foundation, and Sigrid Juselius Foundation as payments made to their institution, outside the submitted work. M Kivimäki reports grants or contracts form Wellcome Trust, UK (221854/Z/20/Z), and the Medical Research Council, UK (MR/R024227/1, MR/S011676/1) as the PI of research funding for their university, outside the submitted work. G Logroscino reports honoraria for lectures from Amplifon, outside the submitted work. J A Louriero reports support for the present manuscript from Fundação para a Ciência e Técnologia (FCT) under the Scientific Employment Stimulus [CEECINST/00049/2018]. A-F A Mentis reports grants or contracts from ‘MilkSafe: A novel pipeline to enrich formula milk using omics technologies’, a research co-financed by the European Regional Development Fund of the European Union and Greek national funds through the Operational Program Competitiveness, Entrepreneurship and Innovation, under the call RESEARCH - CREATE - INNOVATE (project code: T2EDK-02222), as well as from ELIDEK (Hellenic Foundation for Research and Innovation, MIMS-860); stock or stock options in a family winery; all outside the submitted work. M J Postma reports stock or stock options from Health-Ecore and PAG, outside the submitted work. N Steel reports grants from Public Health England to their institution, outside the submitted work. R M Viner reports payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers bureaus, manuscript writing or educational events from Canadian Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry for lecture on mental health aspects of COVID-19 pandemic; leadership or fiduciary role in other board, society, committee or advocacy group, paid or unpaid, as the President of Royal College of Paediatrics & Child Health, 2018-2021; all outside the submitted work.

Acknowledgments

Contributors

Please see appendix section for more detailed information about individual author contributions to the research, divided into the following categories: providing data or critical feedback on data sources; developing methods or computational machinery; providing critical feedback on methods or results; drafting the manuscript or revising it critically for important intellectual content; and managing the overall research enterprise. Members of the core research team for this topic area had full access to the underlying data used to generate estimates presented in this article. All other authors had access to and reviewed estimates as part of the research evaluation process, which includes additional stages of formal review.

Acknowledgements

T W Bärnighausen was supported by the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation through the Alexander von Humboldt Professor award, funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research. F Carvalho acknowledges support from Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia (FCT), I.P., in the scope of the project UIDP/04378/2020 and UIDB/04378/2020 of the Research Unit on Applied Molecular Biosciences - UCIBIO and the project LA/P/0140/2020 of the Associate Laboratory Institute for Health and Bioeconomy - i4HB; FCT/MCTES (Ministério da Ciência, Tecnologia e Ensino Superior) through the project UIDB/50006/2020. M Carvalho acknowledges the support from FCT in the scope of the project UIDP/04378/2020 and UIDB/04378/2020 of UCIBIO and the project LA/P/0140/2020 of i4HB. J S Chandan is funded on a lectureship post by the National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) and has been awarded funds from the NIHR and the Youth Endowment Fund. S Dias da Silva acknowledges the projects UIDP/04378/2021 and UIDB/04378/2021 of the Research Unit on Applied Molecular Biosciences–UCIBIO; the project LA/P/0140/2021 of the Associate Laboratory Institute for Health and Bioeconomy–i4HB; and TOXRUN – Toxicology Research Unit, University Institute of Health Sciences, IUCS-CESPU, Portugal. A J Ferrari is supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council Early Career Fellowship Grant APP1121516 and is employed by the Queensland Centre for Mental Health Research which receives core funding from the Queensland Department of Health. S V Katikireddi would like to acknowledge funding from a NRS Senior Clinical Fellowship (SCAF/15/02), the Medical Research Council (MC_UU_00022/2) and the Scottish Government Chief Scientist Office (SPHSU17). J H Kauppila reports research grants from Sigrid Jusélius Foundation and the Finnish Cancer Foundation. M Kivimaki was supported by the Wellcome Trust (221854/Z/20/Z) and the Medical Research Council, UK (MR/R024227/1, MR/S011676/1). M Kumar would like to acknowledge funding support from K43 TW010716-04/NIH Fogarty International Centre. T Lallukka is supported by the Social Insurance Institution of Finland (grant 29/26/2020). J A Loureiro was supported by Fundação para a Ciência e Técnologia (FCT) under the Scientific Employment Stimulus [CEECINST/00049/2018]. J J McGrath was supported by the Danish National Research Foundation (Niels Bohr Professorship), and is employed by The Queensland Centre for Mental Health Research which receives core funding from the Queensland Health. A-F A Mentis would like to acknowledge funding ‘MilkSafe: A novel pipeline to enrich formula milk using omics technologies’, a research co-financed by the European Regional Development Fund of the European Union and Greek national funds through the Operational Program Competitiveness, Entrepreneurship and Innovation, under the call RESEARCH - CREATE - INNOVATE (project code: T2EDK-02222), as well as from ELIDEK (Hellenic Foundation for Research and Innovation, MIMS-860) both outside the submitted work. J P Silva acknowledges support, through Portuguese national funds via FCT/MCTES, from grants number UIDP/04378/2021 and UIDB/04378/2021 of the Research Unit on Applied Molecular Biosciences (UCIBIO), and LA/P/0140/2021 of the Associate Laboratory Institute for Health and Bioeconomy (i4HB).

Data availability statement

To download the data used in these analyses, please visit the Global Health Data Exchange GBD 2019 website (http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-2019).

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.lanepe.2022.100341.

Appendix B. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Reiner RC, Jr., Olsen HE, Ikeda CT, et al. Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors in Child and Adolescent Health, 1990 to 2017: findings From the Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors 2017 Study. JAMA pediatrics. 2019;173(6) doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.0337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mokdad AH, Forouzanfar MH, Daoud F, et al. Global burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors for young people's health during 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet (London, England) 2016;387(10036):2383–2401. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00648-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet (London, England) 2020;396(10258):1204–1222. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30925-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kieling C, Baker-Henningham H, Belfer M, et al. Child and adolescent mental health worldwide: evidence for action. Lancet (London, England) 2011;378(9801):1515–1525. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60827-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Erskine HE, Moffitt TE, Copeland WE, et al. A heavy burden on young minds: the global burden of mental and substance use disorders in children and youth. Psychological medicine. 2015;45(7):1551–1563. doi: 10.1017/S0033291714002888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Signorini G, Singh SP, Boricevic-Marsanic V, et al. Architecture and functioning of child and adolescent mental health services: a 28-country survey in Europe. Lancet Psychiatry. 2017;4(9):715–724. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(17)30127-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Trautmann S, Rehm J, Wittchen HU. The economic costs of mental disorders: do our societies react appropriately to the burden of mental disorders? EMBO reports. 2016;17(9):1245–1249. doi: 10.15252/embr.201642951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Castelpietra G, Nicotra A, Pischiutta L, Gutierrez-Colosía MR, Haro JM, Salvador-Carulla L. The new Horizon Europe programme 2021–2028: should the gap between the burden of mental disorders and the funding of mental health research be filled? The European Journal of Psychiatry. 2020;34(1):44–46. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wittchen HU, Jacobi F, Rehm J, et al. The size and burden of mental disorders and other disorders of the brain in Europe 2010. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2011;21(9):655–679. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2011.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.GBD 2019 Mental Disorders Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of 12 mental disorders in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2021 doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00395-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.OECD European Union. Health at a Glance: Europe. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hafstad GS, Augusti EM. A lost generation? COVID-19 and adolescent mental health. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8(8):640–641. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00179-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Santomauro DF, Mantilla Herrera AM, Shadid J, et al. Global prevalence and burden of depressive and anxiety disorders in 204 countries and territories in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The Lancet. 2021 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02143-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stevens GA, Alkema L, Black RE, et al. Guidelines for Accurate and Transparent Health Estimates Reporting: the GATHER statement. Lancet (London, England) 2016;388(10062):e19–e23. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30388-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Global Burden of Diseases Results Tool; 2019. http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd;results;tool.

- 16.Sawyer SM, Afifi RA, Bearinger LH, et al. Adolescence: a foundation for future health. Lancet (London, England) 2012;379(9826):1630–1640. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60072-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Whiteford HA, Ferrari AJ, Degenhardt L, Feigin V, Vos T. The global burden of mental, neurological and substance use disorders: an analysis from the global burden of disease study 2010. PLoS One. 2015;10(2):14. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0116820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ferrari AJ, Norman RE, Freedman G, et al. The burden attributable to mental and substance use disorders as risk factors for suicide: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. PLoS One. 2014;9(4):e91936. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0091936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.The burden of mental disorders across the states of India: the Global Burden of Disease Study 1990-2017. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(2):148–161. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30475-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baxter AJ, Scott KM, Ferrari AJ, Norman RE, Vos T, Whiteford HA. Challenging the myth of an "epidemic" of common mental disorders: trends in the global prevalence of anxiety and depression between 1990 and 2010. Depress Anxiety. 2014;31(6):506–516. doi: 10.1002/da.22230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vigo D, Jones L, Thornicroft G, Atun R. Burden of Mental, Neurological, Substance Use Disorders and Self-Harm in North America: a Comparative Epidemiology of Canada, Mexico, and the United States. Can J Psychiatry. 2020;65(2):87–98. doi: 10.1177/0706743719890169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gore FM, Bloem PJ, Patton GC, et al. Global burden of disease in young people aged 10-24 years: a systematic analysis. Lancet (London, England) 2011;377(9783):2093–2102. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60512-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Keski-Rahkonen A, Mustelin L. Epidemiology of eating disorders in Europe: prevalence, incidence, comorbidity, course, consequences, and risk factors. Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 2016;29(6):340–345. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Faraone SV, Biederman J, Mick E. The age-dependent decline of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a meta-analysis of follow-up studies. Psychological medicine. 2006;36(2):159–165. doi: 10.1017/S003329170500471X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Olusanya BO, Davis AC, Wertlieb D, et al. Developmental disabilities among children younger than 5 years in 195 countries and territories, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. The Lancet Global Health. 2018;6(10):e1100–e1e21. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30309-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee SC, DelPozo-Banos M, Lloyd K, et al. Area deprivation, urbanicity, severe mental illness and social drift — A population-based linkage study using routinely collected primary and secondary care data. Schizophrenia Research. 2020;220:130–140. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2020.03.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Żuk P, Savelin L. Real convergence in central, eastern and south-eastern Europe. ECB occasional paper. 2018;(212) [Google Scholar]

- 28.The burden of mental disorders in the Eastern Mediterranean region, 1990-2015: findings from the global burden of disease 2015 study. Int J Public Health. 2018;63(Suppl 1):25–37. doi: 10.1007/s00038-017-1006-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Whiteford HA, Ferrari AJ, Degenhardt L, Feigin V, Vos T. The global burden of mental, neurological and substance use disorders: an analysis from the global burden of disease study 2010. PLoS One. 2015;10(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0116820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Degenhardt L, Charlson F, Ferrari A, et al. The global burden of disease attributable to alcohol and drug use in 195 countries and territories, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5(12):987–1012. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30337-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Inchley JC, Currie DB, Vieno A, et al. WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2018. Adolescent alcohol-related behaviours: trends and inequalities in the WHO European Region, 2002-2014. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Signorini G, Davidovic N, Dieleman G, et al. Transitioning from child to adult mental health services: what role for social services? Insights from a European survey. Journal of Childrens Services.

- 33.Naghavi M. Global, regional, and national burden of suicide mortality 1990 to 2016: systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. BMJ. 2019;364:l94. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kaess M, Schnyder N, Michel C, et al. Twelve-month service use, suicidality and mental health problems of European adolescents after a school-based screening for current suicidality. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Essau CA, de la Torre-Luque A. Comorbidity profile of mental disorders among adolescents: a latent class analysis. Psychiatry research. 2019;278:228–234. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2019.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vigo D, Thornicroft G, Atun R. Estimating the true global burden of mental illness. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3(2):171–178. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00505-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Signorini G, Singh SP, Marsanic VB, et al. The interface between child/adolescent and adult mental health services: results from a European 28-country survey. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2018;27(4):501–511. doi: 10.1007/s00787-018-1112-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Erskine HE, Baxter AJ, Patton G, et al. The global coverage of prevalence data for mental disorders in children and adolescents. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2017;26(4):395–402. doi: 10.1017/S2045796015001158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moitra M, Santomauro D, Degenhardt L, et al. Estimating the risk of suicide associated with mental disorders: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis. J Psychiatr Res. 2021;137:242–249. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2021.02.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Uh S, Dalmaijer ES, Siugzdaite R, Ford TJ, Astle DE. Two Pathways to Self-Harm in Adolescence. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2021;60(12):1491–1500. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2021.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Steel N, Ford JA, Newton JN, et al. Changes in health in the countries of the UK and 150 English Local Authority areas 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. The Lancet. 2018;392(10158):1647–1661. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32207-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.James SL, Castle CD, Dingels ZV, et al. Global injury morbidity and mortality from 1990 to 2017: results from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Inj Prev. 2020 doi: 10.1136/injuryprev-2019-043494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

To download the data used in these analyses, please visit the Global Health Data Exchange GBD 2019 website (http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-2019).