Abstract

Aortic diseases located in the ascending aorta, aortic arch or proximal descending aorta often require more than one surgical intervention depending on the type of pathology and its extent as well as future anticipated aortic problems. These obstacles were tackled in 1983 by Hans Borst with the introduction of the classic elephant trunk (cET). This was an outstanding and straightforward procedure. Since then, the cET was very often the first surgical approach for patients with extensive aortic pathology of the ascending aorta and arch extending into the downstream aorta. Thirteen years later, Suto and Kato introduced the frozen elephant trunk (fET) which was later on perfectionized by industry and applied in various ways by many surgical groups worldwide. Comparing the cET with the fET raises a lot of difficulties. The lack of randomization and the presence of procedural and complication-related limitations for each technique do not allow for definitive conclusions about the ideal procedure to treat complex aortic pathology. It would be very short-sighted to close all future discussions about the subject with this statement of the Hannover group made in 2011. Since both techniques and its results cannot be compared statistically due to the heterogeneity of patient groups, the lack of randomization, the difference in type and extent of pathology, the differences in surgical techniques, the learning curve in gaining experience in both techniques, and the lack of reporting standards, no scientific conclusion can be drawn as to which technique is most successful. Comparisons may even be considered futile. It is the purpose of this paper merely to make a descriptive observation of both techniques, to discuss some important elements of interest and to give some constructive and useful criticism.

Keywords: Aorta, Aneurysm, Aortic dissection, Elephant trunk, Arch replacement, Aortic graft

Introduction

Complex diseases of the aortic arch extending upstream into the ascending aorta and/or downstream into the descending aorta are treated for almost half a century based on the superb concept of the cET described first by Borst et al. [1]. Since the introduction of endografts in aortic surgery, now more than two decades ago, the idea of the fET by Suto and Kato [2, 3] came into view. Both surgical techniques have their specific advantages and disadvantages but due to the diversification of patient clusters treated by cET or fET, it is nearly impossible to weigh both procedures against another with impartiality [4]. We will try to illuminate both approaches from a neutral point of view.

Treatment goals

The treatment goals are the same in both the classic elephant trunk (cET) and the frozen elephant trunk (fET), namely to treat combined ascending aorta, aortic arch, and descending and thoracoabdominal aortic disease and/or to anticipate future treatment of the descending or thoracoabdominal aorta in one or more surgical steps. Another important goal is to minimize potential complications during the second-stage intervention and by simplifying this procedure. The neighbourhood region of the origin of the left subclavian artery is crowded with vital anatomical structures (arterial and venous, important nerves (left recurrent laryngeal nerve and left phrenic nerve), bronchi, the oesophagus, the lymphatic duct) and these structures are often obscured by dense adhesions, sometimes enhanced by the use of extensive Teflon felt during the first procedure. The insertion of an elephant trunk, whether it is a cET or a fET, is an anticipation to potential future operations. This is recommended in any scenario of proximal ascending aortic repair where later secondary distal repair may be needed. It is even a class I level C recommendation [5]. Especially in the setting of acute dissection, we agree with Szeto [6] that a fET allows for a “smaller” operation with lower morbidity and mortality compared to a cET which has been associated with worse results. Both the cET and the fET succeed in avoiding damage to vital structures during the second stage. With the fET, however, it is possible to exclude all aortic pathology in a one-step operation as long as the aortic pathology is limited to the lower border of the fET. With the cEt, it is hardly possible to achieve this since it would require a different and much more invasive surgical approach with a clamshell incision or a sternotomy plus thoracotomy. This implicates that with the use of a cET, a future second-stage operation is inevitable. The cET can be prophylactic and curative but will never allow for a single-stage complete treatment: it always requires a second-stage operation. The fET on the other hand can be prophylactic such as in Marfan, acute type B dissections, or in situations where the descending aorta is moderately dilated and certainly will need further treatment in the future. It can also be curative such as in acute type A dissection, or in rupture of an aneurysm of the transition zone distal arch-proximal descending aorta.

Technical aspects

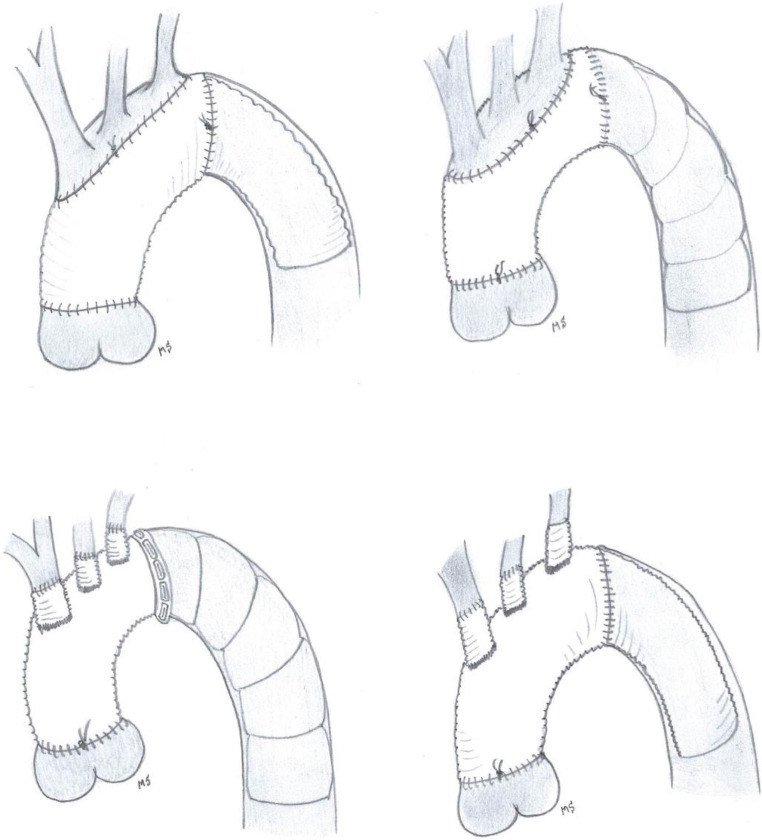

There are no standard surgical protocols for elephant trunk placement and most of the aortic centres have adopted their own surgical strategy over the years. The cET offers some technical possibilities varying from the classic, simple invagination and unfolding of a straight tube graft combined with an island technique for the arch vessel reimplantation to a quadruple branched graft with Siena collar, nowadays more often applied (Siena-Vascutek). This 4-branched graft facilitates vessel reimplantation. The first original technique of the insertion of a cET is very simple and straightforward; the latter (4-branched graft) is more complex because the operative field is more crowded and it demands for separate anastomoses of the arch vessels (Fig. 1). The performance of the distal anastomosis is comparable between the cET and the fET: a circumferential running suture or separate stitches can be used. In the first modification, a double-folded Dacron layer has to be sewn to the native aorta while it is only a single layer of Dacron when a quadruple branched graft is used. The additional use of Teflon, where and how much, remains at the discretion of each individual surgeon. We recommend to limit the use of Teflon as much as possible. Only if the tissues are extremely fragile, a small strip of Teflon may be used, always keeping in mind that Teflon causes awful adhesions making a reintervention in the same anatomical area much more hazardous. Moreover, Teflon felt obscures the bleeding sites making it even more difficult to put an extra targeted stitch. Bleeding at the distal anastomosis has always been a delicate point in the elephant trunk story, both with the classic and the frozen. Apart from the surgical technique (which kind of needle, suture, Teflon yes or no), the deep location of the distal anastomosis has often been blamed as a major concern of control of haemostasis. Initially, when the distal anastomosis was made just beyond the origin of the left subclavian artery, this area was at the end of surgery hardly reachable at all and it certainly was one of the major burdens. Nevertheless, it is possible after the finalization of this distal anastomosis to test it for bleeding before continuing with the other anastomoses. Therefore, one has to restart temporarily the distal body perfusion, mostly via the side arm of the prosthesis or, if this is not possible, via the main graft or retrogradely from the femoral artery (which is not desirable in the case of a cET to avoid trunk impaction). The proximalization of the distal anastomosis from beyond the left subclavian artery area towards the region between the left common carotid artery and the left subclavian artery or even more proximal has really made the technique easier as well as the control for bleeding. Undoubtedly, the manipulation and surgical dissection in the area of the distal aortic arch increase the risk of damaging the left recurrent laryngeal nerve with its negative respiratory and social consequences. The only consequence of the proximalization of the distal anastomosis is that one has to reimplant the left subclavian artery separately and oversew its native origin. As a consequence of the proximalization of the distal suture line, the risks of left recurrent laryngeal nerve damage have decreased substantially. Again this small improvement in the surgical technique yielding an important decrease in complications in both cET and fET is now translated as a class IIa recommendation [5]. Placing the distal anastomosis more proximal than classically described is attractive for several situations including difficulty reaching beyond the left subclavian artery, large aneurysmal size, aortic dissection, arch atheroma and connective tissue disorders.

Fig. 1.

The illustration shows some possibilities of both the cET and the fET: on the left in combination with the island technique, on the right with separate graft reimplantation

Trunk length

The length of the trunk can easily be determined and adapted by the surgeon using the cET, while it is fixed in the fET based on the commercially available sizes. Much has been written about the ideal trunk length in relation to the occlusion of intercostal arteries and the related spinal cord problems. We know from the meta-analysis of Tian et al. that there are certainly conflicting findings making the interpretation of the current clinical data difficult [7]. We agree with Svensson et al. [8] that 10 cm is more than enough using the cET. A shorter trunk will also facilitate the perfusion of both the true and false lumen in the case of chronic dissections. In the case of a fET, a distal landing zone of T7 or lower in combination with a previous abdominal aortic aneurysm repair seems to be a predictor for spinal cord injury [9]. Also Shrestha et al. reported that the optimal length of the fET should not exceed 10 cm [10]. Cerebrospinal fluid drainage related to the use of an elephant trunk is limited to postoperative spinal cord injury; it is not routinely used in a fully heparinized patient. It is clear that at the completion repair after previous cET or fET, the grasping of the trunk necessitates a minimal length of about 5 cm. This manoeuvre is easier with a fET than with a cET since one can more easily clamp the whole aorta around the trunk which is more hazardous in a cET.

Intraoperative temperature management and the risk of paraplegia

In cET as well as fET, cardioprotection as well as brain protection using antegrade selective cerebral perfusion is similar and there is no reason to adapt these protective methods depending on the type of elephant trunk used. Of course in all these interventions nowadays, continuous carbon dioxide flushing is used apart from selective antegrade perfusion to protect the brain. Having said this, it seems obvious that the intraoperative temperature management does not need to differ between cET and fET but in practice and from different papers it seems that there are significant differences between surgical centres and between surgeons. Most aortic centres actually use antegrade selective cerebral perfusion in aortic arch surgery in Europe and arrest circulation at “milder” temperatures, as a recent survey showed [11]. We and also the Leipzig group [12] are convinced that it is much safer to arrest the circulation at lower temperatures, e.g. 20 °C and only then install antegrade cerebral perfusion. This offers the advantage that the surgeon has a longer and safer time window to work in even with the use of antegrade cerebral perfusion. It is clear that at this lower temperature the metabolism of the distal organs including the spinal cord is decreased substantially. Keeping temperatures at a lower level has no impact on haemostasis as long as all anastomoses are performed meticulously. Despite the fact that the occurrence of spinal cord injury is multifactorial, this temperature shift could be an explanation of the much higher risk of spinal cord damage related to the fET. Leontyev et al. underscored this statement [12]. The reported incidence of permanent or transient ischaemic spinal cord injury after cET ranges between 0 and 2.8% [13–16] while in fET this incidence is substantially higher: up to 21.7% [17, 18] with outliers up to 24% [9, 19, 20]. Another possible explanation of the higher incidence of postoperative spinal cord injury related to fET is the fact that in chronic dissections the fET is always inserted into the true lumen, very often over a guide-wire placed retrogradely into the true lumen via femoral access. For decades in aortic surgery it has been a golden rule in chronic dissections to resect the web distally into the aorta or side branch and make an anastomosis to both lumina in order to perfuse both because major side branches can be dependent of the flow in one or another lumen. The obliteration of the false lumen as is deliberately performed in the fET might be a contributing factor to the higher incidence of spinal cord damage. This point was never really clarified in literature. We realize that other factors such as reduction of the body circulatory arrest via restarting lower body perfusion, maintenance of postoperative stable haemodynamics, glycemia and eventually cerebrospinal fluid drainage may play an important role in the avoidance of spinal cord injury related to the use of elephant trunks.

Most centres perform the distal anastomosis and then restart antegrade perfusion via the side arm in order to reduce distal organ ischemia. An alternative is to reimplant the left subclavian artery first, followed by the distal anastomosis and consequently restart antegrade body perfusion and rewarming. This may further enhance spinal cord perfusion via the left vertebral artery. Of course there are a lot of possible variants with regard to the sequence of the performance of the different anastomosis and the reimplantation of the different arch vessels. The aim should always be to minimize body and cardiac ischemic time with associated optimal brain protection.

Is the second stage easier after cET or fET? If the second stage is performed endovascularly, it seems obvious that the landing zone of an endograft into a stented and well-supported landing zone is easier and more reliable compared to an unsupported, free-floating, mobile and unstable graft [21]. With a free-floating cET, there is always a danger during the insertion of a distal thoracic endograft to push the floppy trunk cephalad and deploy the new device not in, but aside, the elephant trunk. Using metal clips or a pacing wire on the end of the free-floating trunk certainly will help to determine the exact position and cannulate the device [22] from below. With the fET, the contours and position of the trunk are obvious.

The clamping of a free-floating elephant trunk or a stented one during the second-stage repair has never been compared technically but there does not seem to be much difference. Both can be clamped with or without opening of the native aneurysmal aorta. The nitinol stent of the fET will resume its natural configuration after declamping. Sewing a new Dacron graft to a cET at the second-stage repair is straightforward. This is certainly more demanding in the case of a fET: one has to incorporate all layers including the native aneurysmal aorta eventually supported by extra Teflon. Certainly the Dacron of a fET is thinner than that of a cET with more stitch hole bleeding as a consequence. Resecting part of the cET of fET is possible before the end-to-end anastomosis with the Dacron polyester graft.

Discussion

The elephant trunk, as it was first described by Hans Borst [1] in the eighties, underwent a surgical and simultaneously a technical revolution. Major concerns related to the cET were the cumulative risk of two major surgical interventions, the interval mortality between the two stages and the fact that a large percentage of patients were lost to the second operation [23]. If the pathology is limited to the proximal descending aorta, the fET offers the major advantage that it does not necessitate a second-stage procedure. However, many other aortic diseases do require a second-stage intervention. Despite the fact that the question “will the elephant trunk become frozen?” was raised several years ago [24], at this moment, the answer to this problem is always yes. Several aortic centres of excellence have shown and illustrated with numbers that indeed the fET is freezing [21]. The Hannover group compared their results using the cET versus the fET. They found that in acute type A dissections the outcome was better using a fET compared to a cET [21].

Was it initially maybe interpreted as an industry-driven overuse of technology, it is clear by 2020 that the fET is in most cases the way to go. So also the answer to the question “Is a classical elephant trunk better than the frozen elephant trunk?” is probably no. Is it worse than the fET? The answer is also negative.

The fET may be a better indication in acute aortic dissections [6, 21] but in chronic situations it remains totally unclear [6]. Since the fET helps to expand the true lumen in the descending aorta, at least in its proximal part, it can prevent future aneurysmal dilatation in the downstream aorta [13]. Stent grafting will result in positive remodelling and resorption of the false lumen thrombus proximally as well as stabilization and expansion of the true lumen distally [21, 25, 26]. fET can also resolve malperfusion problems of the viscera due to accessory entry tears in the distal arch or proximal descending aorta [13]. Despite these facts, the decision to implant an elephant trunk in an acute type A dissection remains difficult since it is a more demanding and complex procedure in often very difficult circumstances in which survival of the patient may dominate the situation.

A second-stage completion procedure has a lower in-hospital mortality rate in patients who had a fET compared to those who had a cET which can be explained by the higher rate of endovascular completion in those having a fET procedure [27].

In order to reduce the initially too high complication rates especially spinal cord lesions and acute renal failure, we can make some suggestions. Part of the solution to these two problems does not lie in the surgical technique but in the temperature management. Arresting the body circulation at 20 °C nasopharyngeal temperature, as we always do in deep hypothermic circulatory arrest, will protect the kidneys and the spinal cord to such an extent that the dramatic and often deadly complications may be reduced substantially. Second, we think in chronic situations that the perfusion of both lumina remains essential to avoid spinal cord disasters. This demands for a resection of the intimal flap.

In patients with connective tissue disorders in which a continuous aortic dilatation is a commonplace and unmistakable fact, the use of stent grafts remain very debatable. But, if stent grafts can be fixated in non-dilatable proximal and distal aortic segments that have already been covered before with stented or non-stented Dacron tubes, there is no reason to avoid this non-invasive technique.

We think that the definitive selection between both techniques depends simply on a combination of the individual training program of the surgeon, the exposure intensity to the relative new technique, and the satisfaction or comfort after the implantation of the first few cases of the fET. Despite the fact that actually the fET is integrated into the aggregate of the cardiovascular techniques of major aortic centres, we still encounter surgeons and centres throughout all European countries in which this “modern” facility is not yet available or is embraced with a relative high resistance. This could be one of the reasons why surgeons still rely on the cET today.

It is clear that within the vertebrate animals the elephant and its trunk did not change or evolve over the last million years. The surgical elephant trunk procedure however evolved much faster than the animals proboscis and it was revolutionized in just a 40-year time period. Without any doubt, it will continue to be simplified to enhance applicability. Despite the fact that the fET has taken the lead, it does not mean that the cET should be dismissed completely from our mind. Its flexibility and simplicity to implant should be part of the armamentarium of each cardiovascular surgeon whether or not we are raised and trained in the era of stents and stent grafts. It remains the base of the fET. To quote Szeto [6], “Not all arch pathologies are the same and therefore should not be treated the same with a ubiquitous procedure; that is, the fET for all”. We need more investigations and studies to identify the appropriate patients before a widespread clinical use of the fET is acceptable. We repeat our earlier standpoint: acclaiming the fET as the first choice further requires objective results from randomized controlled trials [24].

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

Not applicable being a review article.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Borst HG, Walterbusch G, Schaps D. Extensive aortic replacement using ‘elephant trunk’ prosthesis. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1983;31:37–40. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Suto Y, Yasuda K, Shiiya N, et al. Stented elephant trunk procedure for an extensive aneurysm involving distal aortic arch and descending aorta. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1996;112:1389–90. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Kato M, Ohnishi K, Kaneko M, et al. New graft-implanting method for thoracic aortic aneurysm or dissection with a stented graft. Circulation. 1996;94(9Suppl):II188–93. [PubMed]

- 4.Ius F, Hagl C, Haverich A, Pichlmaier M. Elephant trunk procedure 27 years after Borst: what remains and what is new? Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2011;40:1–12. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Czerny M, Schmidli J, Adler S, et al. Current opinions and recommendations for the treatment of thoracic aortic pathologies involving the aortic arch: an expert consensus document of the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS) and the European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS) Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2019;55:133–162. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezy313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Szeto WY. Conventional versus frozen elephant trunk for complex aortic arch pathology: what should we be doing now? J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;149:1294–1295. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2015.02.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tian DH, Wan B, Di Eusanio M, Black D, Yan TD. A systematic review and meta-analysis on the safety and efficacy of the frozen elephant trunk technique in aortic arch surgery. Ann Cardiothorac Surg. 2013;2:581–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Svensson LG, Rushing GD, Valenzuela ES, et al. Modifications, classification, and outcomes of elephant-trunk procedures. Ann Thorac Surg. 2013;96:548–558. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2013.03.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Flores J, Kunihara T, Shiiya N, Yoshimoto K, Matsuzaki K, Yasuda K. Extensive deployment of the stented elephant trunk is associated with an increased risk of spinal cord injury. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2006;131:336–342. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2005.09.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shrestha M, Bachet J, Bavaria J, Carrel T, De Paulis R, Di Bartolomeo R, Etz C, Grabenwöger M, Grimm M, Haverich A, Jacob H, Martens A, Mestres C, Pacinic D, Resch T, Schepens M, Urbanski P, Czerny M. Current status and recommendations for use of the frozen elephant trunk technique: a position paper by the Vascular Domain of EACTS. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2015;47:759–769. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezv085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Paulis R, Czerny M, Weltert L, Bavaria J, Borger M, Carrel T, et al. Current trends in cannulation and neuroprotection during surgery of the aortic arch in Europe. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2015;47:917–923. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezu284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leontyev S, Borger MA, Etz CD, et al. Experience with the conventional and frozen elephant trunk techniques: a single-centre study. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2013;44:1076–1082. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezt252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Inoue Y, Matsuda H, Omura A, Seike Y, Uehara K, Sasaki H, Kobayashi J. Long-term outcomes of total arch replacement with the non-frozen elephant trunk technique for Stanford type A acute aortic dissection. Interact CardioVasc Thorac Surg. 2018;27:455–460. doi: 10.1093/icvts/ivy094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Safi HJ, Miller CC, Estrera AL, et al. Optimization of aortic arch replacement: two-stage approach. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007;83:S815–S818. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2006.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Palma JH, Almeida DR, Carvalho AC, Andrade JC, Buffolo E. Surgical treatment of acute type B aortic dissection using an endoprosthesis (elephant trunk) Ann Thorac Surg. 1997;63:1081–1084. doi: 10.1016/S0003-4975(97)00052-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Etz CD, Plestis KA, Kari FA, et al. Staged repair of thoracic and thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysms using the elephant trunk technique: a consecutive series of 215 first stage and 120 complete repairs. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2008;34:605–614. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2008.04.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leontyev S, Tsagakis K, Pacini D, Di Bartolomeo R, Mohr F, Weiss G, et al. Impact of clinical factors and surgical techniques on early outcome of patients treated with frozen elephant trunk technique by using EVITA open stent-graft: results of a multicentre study. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2016;49:660–666. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezv150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tian DH, Wan B, Di Eusanio M, Yan TD. Systematic review protocol: the frozen elephant trunk approach in aortic arch surgery. Ann Cardiothorac Surg. 2013;2:578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Miyairi T, Kotsuka Y, Ezure M, Ono M, Morota T, Kubota H, Shibata K, Ueno K, Takamoto S. Open stent-grafting for aortic arch aneurysm is associated with increased risk of paraplegia. Ann Thorac Surg. 2002;74:83–89. doi: 10.1016/S0003-4975(02)03602-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mizuno T, Toyama M, Tabuchi N, Wu H, Sunamori M. Stented elephant trunk procedure combined with ascending aorta and arch replacement for acute type A aortic dissection. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2002;22:504–509. doi: 10.1016/S1010-7940(02)00429-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shrestha M, Beckmann E, Krueger H, Fleissner F, Kaufeld T, Koigeldiyev N, Umminger J, Ius F, Haverich A, Martens A. The elephant trunk is freezing: the Hannover experience. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;149:1286–1293. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2015.01.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Greenberg RK, Haddad F, Svensson L, et al. Hybrid approaches to thoracic aortic aneurysms: the role of endovascular elephant trunk completion. Circulation. 2005;112:2619–2626. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.552398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Di Bartolomeo R, Murana G, Di Marco L, Pantaleo A, Alfonsi J, Leone A, Pacini D. Frozen versus conventional elephant trunk technique: application in clinical practice. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2017;51:i20–i28. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezw335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schepens MAMM. Will the elephant trunk become frozen? Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2011;40:11–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2011.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dohle D, Tsagakis K, Janosi RA, et al. Aortic remodelling in aortic dissection after frozen elephant trunk. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2016;49:111–117. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezv045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Inoue Y, Matsuda H, Omura A, Seike Y, Uehara K, Sasaki H, Kobayashi J. Comparative study of the frozen elephant trunk and classical elephant trunk techniques to supplement total arch replacement for acute type A aortic dissection. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2019;56:579–586. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezz104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rustum S, Beckmann E, Wilhelmi M, Krueger H, Kaufeld T, Umminger J, Haverich A, Martens A, Shrestha M. Is the frozen elephant trunk procedure superior to the conventional elephant trunk procedure for completion of the second stage? Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2017;52:725–732. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezx199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]