Abstract

Connective tissue disorders (CTDs) are a group of genetically triggered diseases in which the primary defect involves collagen and elastin protein assembly with potential vascular degenerations such as thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm (TAAA) and dissection. These most commonly include Marfan syndrome, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, Loeys-Dietz syndrome, and familial thoracic aortic aneurysm and dissection. Open surgical repair represents the standard approach in this specific group of patients. Extensive aortic replacements are generally performed in order to reduce long-term complications caused by the progressive dilatation of the remnant aortic segments. In the last decades, endovascular interventions have emerged as a valid alternative in patients affected by degenerative TAAA. However, in patients with CTD, this approach presents higher rates of reinterventions and postoperative complications with a disputable long-term durability, and it is nowadays performed for very selective indications such as severe comorbidities and urgent/emergent settings. Despite a deeper knowledge of the pathophysiological mechanisms involved in CTD, improvements in medical therapy, and a multidisciplinary approach fully involved in the management of these usually frailer patients, this specific group still represents a challenge. Further dedicated studies addressing mid-term and long-term outcomes in this selected population are needed.

Keywords: Connective tissue disorder, Marfan syndrome, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, Loeys-Dietz syndrome, Thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm, Aortic dissection

Introduction

A connective tissue disorder is a genetic disease in which the primary target is either collagen or elastin protein assembly, disruption of which leads to an inherent predisposition to degeneration, loss of structural integrity, and consequent aneurysm formation or spontaneous vascular dissection and rupture. Thus, these heritable disorders of connective tissue can have severe vascular manifestations and are relevant causes of thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm development, especially in younger patients.

Connective tissue disorders

The index of suspicion of genetic connective tissue disorder, in young patients with non-atherosclerotic aortic aneurysms, should be very strong. Genetic evaluation is important for the definition of the familial risk of aortic aneurysm as well as for medical strategy and surgical timing for the repair. Different gene abnormalities are related to higher/lower risk for aortic enlargement/dissection, and should be detected in order to define the exact risk profile of the single patient. These most commonly include Marfan syndrome, Loeys-Dietz syndrome, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, and familial thoracic aortic aneurysm and dissection. The development of next-generation sequencing (NGS) genetic analysis has largely contributed to the genetic implementation among clinical practice.

Marfan syndrome (MFS)

| Epidemiology | From 1 in 5000 to 2–3 per 10,000 (1) |

|---|---|

| Genetic | Autosomal dominant |

| Mutation | Fibrillin-1 (FBN-1) |

| Clinical presentation | Aortic aneurysms and dissection. More than 30 signs are also variably associated with MFS with skeletal, cardiovascular, and ocular system involvement. All fibrous connective tissue can be affected |

| First described in | 1896 |

| Diagnosis | Clinical criteria (the Ghent nosology) |

People with MFS are usually tall and thin, with long arms, legs, fingers, and toes. The signs and symptoms can vary greatly, even among members of the same family, because the disorder can affect different areas of the body. Clinical signs may include tall and slender build, pectus excavatum, pectus carinatum, scoliosis, joint hypermobility, camptodactyly or clinodactyly, enophthalmos, and others (Fig. 1). All the different morphological characteristics of the MFS are described by the recently revised Ghent nosology [1]. But not in all patients an obvious phenotype can be detected, for example in younger patients, in which phenotype has not yet got time to manifest.

Fig. 1.

Clinical presentation of a patient with MFS. (A) The patient is very tall with long arms and legs, (B) with hindfoot deformity, (C) hand arachnodactyly, and (D) pectus carinatum deformity (MFS, Marfan syndrome)

Cardiovascular system

Mucopolysaccharide deposition in the valves may cause valve leaflet thickening and this is directly associated with valvular diseases. Mitral valve prolapse, regurgitation, and aortic valve incompetence are the most common causes of morbidity and mortality. Aortic valve incompetence usually arises in the context of a dilated aortic root. Myocardial infarction may occur, if an aortic root dissection occludes the coronary ostia. Risk factors for aortic dissection include aortic diameter greater than 5 cm, aortic dilatation extending beyond the sinus of Valsalva, rapid rate of dilatation (45% per year, or 1.5 mm/year in adults), and family history of aortic dissection.

Pregnancy in MFS

The risk of aortic dissection in pregnancy is increased, probably due to inhibition of collagen and elastin deposition in the aorta by the hyperdynamic hypervolemic circulatory state of pregnancy. Conditions such as gestational hypertension and pre-eclampsia may be additional risk factors. Aortic dissection occurs in around 4.5% of pregnancies in women with MFS and the risk is greater if the aortic root diameter exceeds 4 cm at the start of pregnancy, or if it dilates rapidly [2]. A more frequent monitoring of aortic diameter in pregnancy is advisable. In any case, it might suggest an increased risk of later aortic dissection/aortic root replacement. If the aortic root dilates to 5 cm during the pregnancy, consideration should be given to immediate aortic replacement.

Loeys-Dietz syndrome (LDS)

| Epidemiology | < 1 per 100.000 |

|---|---|

| Genetic | Autosomal dominant |

| Mutation | One of the five genes that encode for the receptors and other molecules in the transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) pathway |

| Clinical presentation | Aortic aneurysms and generalized arterial tortuosity. Hypertelorism, bifid/broad uvula, and cleft palate are other typical signs |

| First described in | 2005 |

| Diagnosis | Clinical triad (hypertelorism, cleft palate, or bifid uvula and aortic aneurysm) |

Most individuals with LDS have craniofacial features that include hypertelorism (widely spaced eyes) and a bifid or broad uvula. In a smaller percentage of individuals, craniosynostosis (premature fusion of the skull bones), cleft palate, and/or club foot are noted. Almost all patients show some type of abnormal skin findings including translucent skin, soft or velvety skin, easy bleeding, easy bruising, recurrent hernias, and scarring problems [3]. In the past, many individuals with LDS were mistakenly diagnosed with MFS.

Cardiovascular system

The most common and prominent finding is the dilatation of the aortic root at the sinuses of Valsalva, which if undetected leads to aortic dissection and rupture. These dissections have been described in patients as young as 3–6 months of age. Moreover, dissections have occurred at smaller diameters than those generally accepted at risk in MFS. In addition to the aortic root aneurysms, aneurysms throughout the arterial tree have been described, most prominently in the side branches of the aorta and the cerebral circulation. Finally, another striking finding is the presence of arterial tortuosity, which is usually most prominent in the head and neck vessels. Vertebral and carotid artery dissection and cerebral bleeding are common [4].

Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (EDS)

| Epidemiology | from 1:5000 to 1:25,000 |

|---|---|

| Genetic | Autosomal dominant |

| Mutation | COL3A1, rarely COL1A1 |

| Clinical presentation | Skin hyperextensibility, fragile and soft skin, delayed wound healing with formation of atrophic scars, easy bruising, and generalized joint hypermobility. Vascular EDS is characterized by arterial fragility |

| First described in | 1892 |

EDS is an inherited heterogeneous group of connective tissue disorders, characterized by abnormal collagen synthesis, affecting skin, ligaments, joints, blood vessels, and other organs. There are many subtypes of the disorder with classic EDS (types I and II) being the most common. It is important to identify the correct type because the natural history differs among the subtypes.

Cardiovascular system

Vascular EDS (previously known as EDS type IV) results from mutations in COL3A1, the gene that encodes the chains of type III collagen, and has the worst prognosis because of its association with severe and often fatal rupture of the bowel, other organs, and large arteries. Type III collagen is a major protein in the walls of blood vessels and hollow organs, which explains increased bruising, arterial and bowel fragility, and uterine, cervical, and vaginal fragility during pregnancy and delivery [5, 6].

Familial thoracic aortic aneurysm and dissection (TAAD) syndrome

This group includes all the familial syndromes, without specific identifiable genetic defects. Between 11 and 19% of patients referred for surgery with TAAD have first-degree relatives with either aneurysm or dissection [7]. Different mutations have been identified in the following:

TGFbR2, similar to LDS

Smooth muscle cell–specific myosin heavy chain 11, a protein involved in smooth muscle cell contraction

ACTA2, encoding smooth muscle–specific a-actin, also involved in vascular smooth muscle cell contraction.

Turner syndrome (TS)

TS is a neuro-genetic disorder characterized by partial or complete monosomy-X. It is associated with physical and medical features including estrogen deficiency, short stature, and increased risk of several diseases with cardiac conditions being among the most serious. Congenital and acquired heart conditions such as of the aorta and bicuspid aortic valves, mitral valve prolapse, hypertension, ischemic heart disease, and arteriosclerosis are frequently associated [8].

Bicuspid aortic valve

Bicuspid aortic valve is the most common congenital abnormality affecting the aorta, occurring in 1 to 2% of the population. This common congenital cardiac abnormality leads to an increased risk for ascending aortic aneurysm, dissection, and valvular aortic stenosis and regurgitation [7].

Imaging

Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) allows visualization of the aortic root and also of portions of the ascending aorta and the aortic arch.

Transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE) is also useful in aortic dissection and to evaluate the ascending and the descending aorta.

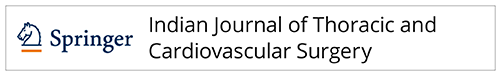

Computerized axial tomography (CTA) is the gold standard for patient with thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm (TAAA) and connective tissue disorders (CTDs). However, young patients with genetic aortic syndrome often need to be examined repeatedly over the course of their lives; therefore, an intravenous iodine-containing contrast agent with its associated collateral effects represents a drawback of this diagnostic method. Furthermore, the radiation dose to which patients are subjected is not negligible and associated with collateral effects. CTA represents the modality of choice also before surgical or endovascular repair. An accurate preoperative imaging is needed in all patients to precisely assess the aortic anatomy, fully evaluate the aortic main branches, and obtain information about the spinal cord vasculature, in order to plan the best individual surgical strategy. Post-processing of computerized tomography (CT) images using reformatting software and workstations allows to visualize possible specific morphologic issues related to aortic dissection, and may help a correct surgical planning. In particular, the dissecting lamella, which may have a tortuous path, can be correctly analyzed using oblique multiplanar reconstructions (MPRs), as shown in Fig. 2A. Maximum intensity projection (MIP) protocols should be avoided in case of dissection because of their ability to mask the dissecting lamella and parietal thrombus. Three-dimensional (3D) volume rendering plays a role in understanding the conformation of the entire dissection and the relative position of the visceral and renal vessels, in order to plan a tailored reimplantation strategy in Fig. 2B.

Fig. 2.

(A) Using a MPR, the curved path of the dilated dissected thoracic aorta is well reproduced and the true lumen and the false lumen are properly visualized. (B) 3D volume rendering plays a role in understanding the conformation of the entire dissection and the relative position of the visceral and renal vessels, in order to plan a tailored reimplantation strategy

Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) is characterized by a high diagnostic accuracy. However, the longer examination time of MRA in comparison to CTA represent a disadvantage. Literature has shown that electrocardiogram (ECG)-triggered non-contrast MRA is equal to contrast-enhanced MRA for measuring the aortic diameter in preventive care [9–11].

Dissections also occur in patients with genetic aortic syndromes with normal diameter; therefore, it is necessary to identify additional predictors for dissection, new hemodynamic parameters, and their effect on the vascular wall. Modern imaging methods like four-dimensional (4D) flow magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and pulse wave velocity (PWV) have a potential role to further improve individualized risk stratification in patients with genetic aortic syndromes [12–16].

In the pediatric population, the diagnosis of MFS remains difficult because many clinical manifestations are age-dependent and the Ghent criteria, usually used for adults, are not reliable in children. The orthopedic features of the disease are often clinically more evident in comparison to the other features. A recent study showed statistically significant correlation between the presence of pectus excavatum and Z-score ≥ 3 [17].

Aortic dimensions and management

Normal aortic diameter varies by age and sex and increases with age and height. The size of the aorta decreases with distance from the aortic valve. The normal diameter of the descending thoracic aorta is 2.5 ± 0.2 cm in men and 2.2 ± 0.2 cm in women [18]. The normal diameter of the infrarenal aorta is 2.0 ± 2 cm in men and 1.7 ± 1.5 cm in women.

Many scores have been identified to evaluate the aortic diameter, among them:

Aortic height index (AHI) AHI≈

The AHI was discretized by Zafar into 6 groups to assess the rate of adverse events at different aortic sizes [19]

Aortic Z-score (Z-score) is used in clinical trials to monitor the effect of medications on aortic dilation rate in MFS patients. Therefore, the aortic root diameter needs to be determined and expressed as a Z-score. The body surface area (BSA) was used to derive the “Z score” which represents a statistical index for evaluating aortic diameter [17].

Current guidelines also consider the aneurysm etiology and location, as these also impact the risk of rupture and dissection. According to current guidelines, repair for thoracoabdominal aneurysms is suggested for diameter ≥ 6 cm in case of degenerative aneurysms [20]. However, recent studies have shown that the risk of adverse aortic events in patients with TAAA increases at aortic sizes below this guideline-recommended threshold [21–24]. In case of genetically triggered TAAA instead, the threshold is lowered to a lower diameter according with the specific genetic disease. In case of MFS and EDS, the indication is lowered for a threshold diameter of 5 cm, while in case of LDS, repair is recommended at an aortic diameter of just 4.2 cm due to the especially aggressive behavior of this aortopathy [25].

Patients with CTD and thoracic aortic aneurysm (TAA)/TAAA and dissection frequently come with valvular lesions. The management of these patients is debated and could be difficult to understand the priority of one disease on another. At our knowledge, current literature does not report any randomized studies regarding this specific field. According to our standard clinical practice, a combined evaluation performed by vascular surgeons, cardio-thoracic surgeons, cardiologists, and cardiac anesthesiologists may be helpful in order to establish the correct timing. Notably, it may be considered that left heart valvular defects could be partially supported during an open thoracic or thoracoabdominal procedure throughout the left heart bypass.

A conservative approach could be performed in asymptomatic patients with an aneurysm that do not reach the dimensional threshold for repair:

-Measures to reduce cardiovascular risk, aggressive blood pressure control, and other measures to limit aneurysm expansion.

-Patient education regarding the symptoms and signs that may indicate the development of complications.

-Counselling for those suspected of having a genetically triggered disease. First-degree relatives of those with TAA disease should be screened, based on family studies demonstrating an approximately 20% chance of another first-degree relative having a TAA.

-Screening for associated aneurysmal disease.

-Serial imaging of the aneurysm to evaluate for expansion and changes in extent.

Patients with CTD and TAAA frequently present also valvular lesions. The management of these patients is debated and could be difficult to understand the priority of one disease on another. At our knowledge, current literature does not report randomized studies regarding this specific field. A combined evaluation performed by vascular surgeons, cardio-thoracic surgeons, cardiologists, and cardiac anesthesiologists may be helpful in order to establish the correct timing. Notably, it may be considered that left heart valvular defects could be partially supported during an open TAA or TAAA procedure throughout the left heart bypass (LHB).

Anesthesia in tissue disorder patients

In such patients, a more accurate preoperative screening with a detailed anesthesiological and surgical workup is recommended. These patients are complex with an increased risk of developing cardiovascular and respiratory complications. In the operating room, patients are carefully managed and positioned to avoid joint dislocations secondary to tissue laxity. Prominent skeletal abnormalities (kyphoscoliosis and micrognatia) may be responsible for difficult intubation procedures, together with an increased risk of subclinical cervical spine instability. If known, preoperatively elective fiber-optic intubation may be used [26]. Marfan patients have a high prevalence of pulmonary emphysema for which low inspiratory pressures and protective ventilation may be adopted: low tidal volumes (5–6 mL), small amount of positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP, 5–10 cmH2O), and limited inspiratory pressure plateau (< 35 cm H2O). Whenever one-lung ventilation is performed, dynamic hyperinflation is avoided.

Different parts of the cardiovascular apparatus are frequently involved in Marfan patients, and common findings are variable degrees of mitral regurgitation related to mitral valve prolapse and dilatation of the aortic root with or without aortic regurgitation. For such reason, intraoperative TEE monitoring is suggested when performing general anesthesia [27]. β-blockers are not discontinued prior to surgery in order to maintain a reduced aortic wall stress by decreasing both stroke volume and cardiac contractility [28, 29]. Furthermore, literature reported a beneficial impact of angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), when associated to β-blockers [30]. Other authors did not confirm these results [31]. However, ARBs administered before surgery may be responsible for deep hypotension during general anesthesia; therefore, withdrawal of such agents in the preoperative assessment should be evaluated case by case, weighting the risk of intraoperative hypotension against rebound hypertension.

Dural ectasia (DE) is a common finding in CTD, in Marfan patients ranging between 63 and 92%, and more frequently arising at the level of the lumbar vertebrae due to increased hydrostatic pressure of the cerebrospinal fluid on a weakened dura [32]. The presence of DE affects the quality of local anesthesia, higher volume of cerebrospinal fluid drainage (CSFD), in the lumbar theca may decrease the spread of local anesthetic when performing spinal anesthesia, while epidural anesthesia failure may be due to a decreased spread of local anesthetic due to an enlarged dural sac [33]. To overcome this risk, a lateral decubitus position (decreased DE in the needle insertion zone) and preprocedural ultrasound scanning of the spine represent valid approaches to determine the best space to insert the needle that are recommended. Although MRI may identify the patients with DE in whom epidural nerve block may fail, each patient responds in an unpredictable fashion to the local anesthetic.

CSFD is frequently used during TAAA open repair in order to reduce the risk of postoperative spinal cord ischemia. After patient sedation and prior to surgical incision, the dura is punctured with an introducer needle and a drainage catheter is inserted 8 to 10 cm beyond the tip of the needle into the subarachnoid space for the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) drainage. The CSF pressure monitoring is usually maintained during the first 48–72 h between 8 and 10 mmHg using an automatic system (LiquoGuard®—Möller Medical) allowing simultaneous CSF pressure measurements and CSF drainage by a closed system with dual pressure sensors with an electronically controlled peristaltic pump [34]. However, patients with CTD frequently come with skeletal abnormalities (scoliosis) that may represent a possible contraindication to CSFD placement. DE may represent another contraindication.

Treatment

The propensity to aortic dilation and dissection, in patients with CTD, underlines the importance of determining the most appropriate aortic repair to obtain the best short- and long-term outcomes.

Open surgical repair

One must consider the feeble nature of tissues in patients with CTD when reconstructing the aorta during aneurysm repair. A critical issue is linked to the fact that the primary goal of surgical treatment is to perform a complete aortic replacement leaving as little aortic tissue as possible, thus avoiding long-term complications due to progressive dilatations of the remnant aortic segments.

Surgical technique

The thoracic incision varies in length and level, depending on the aneurysm extent, but usually ranging between the 5th and 7th intercostal space. The posterior section of the rib, or its whole resection when needed, associated with a gentle and progressive use of the retractor, is useful to reduce thoracic wall trauma and fractures; antero-laterally, the incision curves gently as it crosses the costal margin, reducing the risk of tissue necrosis. The pleural space is entered after single right lung ventilation is initiated. Monopulmonary ventilation is maintained throughout thoracic aorta replacement. Paralysis of the left hemidiaphragm produced by its radial division to the aortic hiatus may contribute significantly to postoperative respiratory failure; hence, after thoracoabdominal incision, a limited circumferential section of the diaphragm is routinely carried out, sparing the phrenic center in order to reduce respiratory weaning time [35]. Due to an inflammatory reaction, pleural adhesions are quite common in CTD patients with previous thoracic surgical repair or in case of chronic aortic dissection; in these cases, it is important to perform a limited tissue dissection to minimize pulmonary bleeding.

Special care is taken during proximal neck exposition at the thoracic aortic level, and this can be supported using a vessel loop. The vagus nerve and the origin of the recurrent laryngeal nerve are identified, since they can be damaged during the exposition of the aortic isthmus and the clamping maneuvers. Often in CTD patients with previous thoracic or pericardial surgeries, there is a greater risk of complications during surgical isolation due to adhesions.

Identification and clipping of some “high” intercostal arteries can sometimes facilitate the preparation for the proximal anastomosis, thus reducing aortic bleeding. The upper abdominal aortic segment may be exposed via a transperitoneal approach; the retroperitoneum is entered lateral to the left colon so that the left colon, the spleen, and the left kidney could be medially rotated and retracted. A transperitoneal approach allows direct view of the abdominal organs and allows a prompt evaluation of their perfusion at the end of aortic repair.

Cross-clamping of the descending thoracic aorta leads to several hemodynamic disturbances, including severe afterload increase and organ ischemia. The technique for distal aortic perfusion with a LHB has proved to be extremely useful during aortic repair [36]. With the LHB, distal organ perfusion is maintained during the clamping time with concomitant reduction of the cardiac afterload. The LHB circuit includes an inflow cannula, an inline centrifugal pump without a cardiotomy reservoir or oxygenator, and an outflow cannula. Prior to LHB and aortic clamping, to reduce bleeding from the extensive tissue exposure, low-dose intravenous heparin is administered (70 UI/kg).

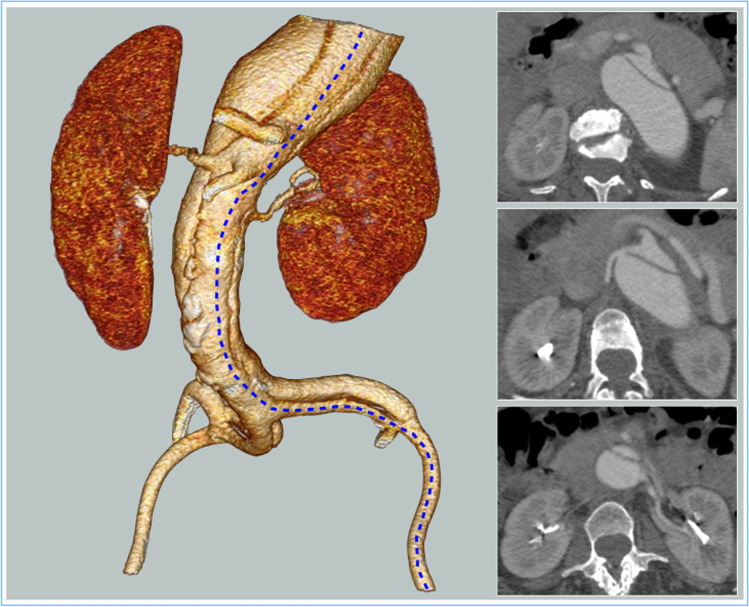

The inflow cannula is placed in the left superior pulmonary vein (20-French moldable cannula) to reach the left atrium and checked with TEE, and the arterial blood is then reinfused into the femoral artery. Especially in case of chronic aortic dissection, proximal cannulation of the aorta should be avoided in favor of atrial or pulmonary vein cannulation. The cannula for the outflow (14–16 French) is placed through an over-the-wire technique (0.035″) in the common femoral artery in order to reduce the risk of dissection during retrograde insertion of the cannula. It is secured with a purse-string suture and the artery is not occluded, allowing distal perfusion of the ipsilateral limb during assisted circulation. In case of concomitant dissection, a preoperative angio-CT evaluation is important to assess the involvement of the iliac arteries in order to choose the best femoral artery for the distal reperfusion (Fig. 3). A “Y” bifurcation is connected to the circuit and is provided with two occlusion/perfusion catheters (9 Fr) for selective perfusion of the visceral vessels.

Fig. 3.

Preoperative evaluation with angio-CT is important to assess the involvement of the iliac arteries by the dissection and the origins of the visceral vessels. The blue line on the 3D volume rendering underlines the partially compressed true lumen; on the axial scans, it is possible to observe the origins of the visceral and renal vessels from the true and false lumen

In case of concomitant aortic dissection, proximal aortic clamping is obtained between the left common carotid artery (LCCA) and the left subclavian artery (LSA), allowing to perform the proximal anastomosis at a healthier and less fragile aortic site. In few selected cases, when the location, extent, and severity of disease precludes placement of a proximal aortic clamp distally to the LCCA, hypothermic circulatory arrest may be performed to allow proximal anastomosis to be completed. Once the proximal aspect of the TAAA is isolated between clamps, the descending thoracic aorta is transected and separated from the esophagus. Due to the aortic wall weakness, a padded atraumatic clamp may be used to reduce the incidence of anterograde and retrograde dissection.

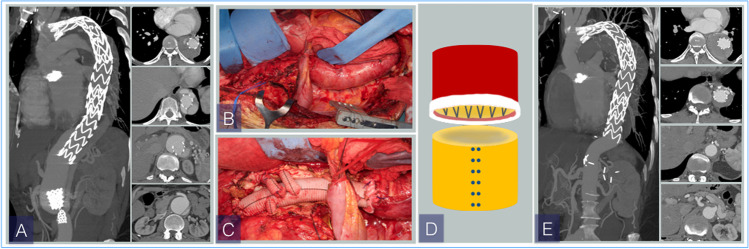

The proximal end of the graft is sutured to the descending thoracic aorta, usually using a 2/0 polypropylene in a running fashion, but in case of CTD, a 3/0 or 4/0 polypropylene may be preferred in order to reduce the tissue trauma. The anastomosis could also be reinforced with a Teflon felt, or even with a double-layer Teflon felt placed inside and outside the aortic wall as a “sandwich” (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Proximal anastomosis. (A) The proximal aortic clamp is placed between LCCA and LSA (blue arrow) after the left subclavian artery is selectively clamped (green arrow). The thoracic aorta is completely transected and the false (single asterisk) and the true (double asterisks) lumen are visualized. (B) The proximal end of the graft is sutured to the descending thoracic aorta with a 3/0 polypropylene running suture reinforced with a Teflon felt (blue arrows). LCCA, left common carotid artery; LSA, left subclavian artery

The clamp is then removed and reapplied onto the abdominal aorta above the celiac axis (sequential cross-clamping) and a longitudinal aortotomy is performed. Reimplantation of intercostal arteries to the aortic graft plays a critical role in spinal cord protection. Critical patent segmental arteries from T8 to L2 are temporarily occluded with Pruitt catheters to avoid blood steal phenomenon and then selectively reattached to the graft with bypasses. During TAAA open repair, especially in young patients, intercostal arteries are reattached to the aortic prosthesis whenever possible. However, in patients with CTD, the aortic wall could be extremely fragile and weakened by the genetic disease, in particular in patients with dissection. In these patients, intercostal artery reattachment could be counter-productive with subsequent bleeding issues. So, intercostal artery reattachment is performed only when the aortic tissue appears suitable for anastomosis, and the intraoperative evaluation of the aortic wall quality represents a key point in the decision-making process. The distal clamp is then moved below the renal arteries and the aneurysm is opened below the diaphragm. Visceral isothermic hematic perfusion is then maintained by the pump with irrigation-perfusion catheters of the same size (9 Fr) inserted selectively into the celiac trunk and the superior mesenteric artery. Selective cold perfusion of the renal arteries is performed with Custodiol (histidine-tryptophan-ketoglutarate) or cold crystalloid [37]. Specific attention must be paid when inserting the cannula in a visceral vessel that might be involved by dissection.

Two different techniques are used during open TAAA repair: the Crawford inclusion technique and the branched graft technique. The first technique is characterized by direct reimplantation of visceral and intercostal vessels in the aortic graft in the form of a Carrel patch; with the second technique instead, individual reconstructions of visceral vessels using branches of the prosthetic graft are performed [38, 39] (Fig. 5). In patients with CTD, the remnant aortic wall tissue of the aortic patches has a high risk of degeneration that can lead to further dilatation (18%) and possible reinterventions [40]. Thus, selective reattachments with individual bypass or multibranched grafts are preferred. In CTD patients, the take home message is to leave as little aortic tissue as possible.

Fig. 5.

Final reconstruction after open surgical repair of patients with CTD. (A) Visceral and renal vessels are selectively reattached using a multibranched graft. A selective bypass I was also performed to reattach a couple of critical intercostal arteries. (B) Selective reattachment of two couples of intercostal arteries using bypass. CTD, connective tissue disorder

Endovascular repair

As endovascular techniques have emerged in the last decade as first choice to treat several thoracic aortic pathologies, a word of caution must be spent regarding stent grafting in Marfan patients especially for what concerned the mid- and long-term outcomes. Endovascular approaches can have some advantages in elderly patients with medical comorbidities affected by CTD.

Considerations for the endovascular approach in CTD patients are as follows:

These characteristics suggest a prior surgical replacement of aortic segments in order to ensure adequate proximal and distal landing zones. Indeed, in literature, a “proactive approach” is proposed in which an elephant trunk or frozen elephant trunk is performed in CTD patients with indications for ascending aorta or aortic arch repair to obtain an adequate proximal landing zone if an endovascular procedure is eventually required [48] (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

(A) Preoperative angio-CT. Dissecting TAAA in a Marfan patient with previous ascending aorta and aortic valve replacement and TEVAR. The patient developed a distal progression of disease with type IB endoleak. (B) Surgical repair with multibranched graft and selective reattachment of visceral and renal vessels. In this case, the proximal end of the graft is sutured to the distal end of the previous stent graft using a 2/0 monofilament polypropylene running suture. (C) Postoperative angio-CT-3D volume rendering. CT, computerized tomography; TAAA, thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm; TEVAR, thoracic endovascular aortic repair

In CTD patients, the aortic disease progression might compromise the stability between the main endograft and bridging stents of the visceral arteries. In recent studies, MFS patients with aortic dissection were associated with a greater growth rate of aortic branches, so in case of endovascular repair of aortic aneurysms, the long-term fate of the stent branches is still a matter of debate [49]. Long-term data regarding this open issue is lacking in the literature. A recent study suggests that 20% of MFS patients will need some form of intervention on non-aortic arterial segments 5 to 6 years after their first aortic intervention [50].

However, in case of aortic rupture, endograft may be lifesaving in CTD patients. In patients undergoing previous cardiac surgery, Roselli et al. [51] proposed a preparatory approach placing elephant trunk or frozen elephant trunk reconstruction technique during the index aortic arch repair, to reduce the incidence of retrograde type A aortic dissection during endovascular descending aortic repair.

Hybrid approach

A hybrid approach has been proposed as an alternative treatment in patients with TAAA, especially in prohibitive high-risk patients. In the literature, experiences with TAAA hybrid repair in patients with CTD are limited to small series [52, 53]. Arnaoutakis et al. recently published a comparative study reporting results of open, hybrid, and endovascular treatment in patient with TAAA including both degenerative aneurysms and CTD [54]. While the 30-day mortality was higher in the hybrid group, the rate of permanent spinal cord injury (SCI) was not different among the three groups. A hybrid treatment may be cautiously used in patients with CTDs in very selective circumstances, especially in patients with frozen chest. However, with the hybrid approach, the peculiar possible complications related to the endovascular treatment (e.g., persistent stent graft radial forces in a genetically weakened aorta) should be considered in terms of long-term results and are also associated with an invasive surgical approach with visceral and renal vessel rerouting.

Recent evidences in literature

A recent systematic literature review included 28 studies about the treatment of TAAA in CTD patients, with 8 studies concerning open TAAA reconstruction characterized by direct reimplantation of visceral and intercostal vessels in the aortic graft in the form of a Carrel patch, 8 studies reporting open branched graft characterized by individual reconstructions of visceral vessels using branches of the prosthetic graft, and 12 studies on endovascular treatment of TAAA and dissections in patients with CTD. In this review, no fenestrated or branched endovascular aneurysm repairs (EVARs) were included and patients were treated by thoracic endovascular aortic repairs (TEVARs) and infrarenal EVARs. In this review, a significant number of endovascular procedures were for emergent repair.

Furthermore, significant rates of endograft-related complications and substantial need for secondary endovascular interventions and open conversions have been identified: in open aortic reconstruction with Carrel patch, paraplegia ranged from 0 to 6.5% and permanent renal failure from 0 to 13%; in open branched graft, from 0 to 9% (paraplegia) and 0–8% (permanent renal failure); in endovascular repair, from 0 to 3.3% for paraplegia and 0–6.7% for permanent renal failure [52].

Postoperative care

Postoperative monitoring greatly depends on the surgical procedure performed and on the preoperative status of the patient (in particular left ventricle size and function and aortic root size); therefore, intensive care is not strictly mandatory. Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) is sometimes a feature of Marfan patients, characterized by marked postural hypotension and reflex tachycardia. Such disorder can arise at any time in the natural history of MFS and requires well-known measures (such as gradual passage to a standing position) [50]. Volume expansion with crystalloids and vasopressors can be used. Another key aspect of the postoperative management of Marfan patients is pain relief.

Conclusion

Despite advances in the understanding of the pathophysiological mechanisms in the involvement of the aorta in patients with CTD, early diagnosis, control of potential underlying risks, and management remain a challenge. Open surgery repair is the standard approach to treatment of aortic disease in CTD patients in whom the use of multibranched grafts is preferred. Endovascular interventions may be cautiously used in patients with CTDs under selective circumstances.

Actually in literature, no systematic review regarding fenestrated and branched repair is available in this specific subpopulation of patient; further studies are needed to evaluate mid-term and long-term outcomes in patients with CTD treated by endovascular fenestrated and branched repairs. Regarding the health care system management for this condition, we consider it necessary to centralize the cases in high-volume centers and set up specialized “aortic team.”

Funding

None.

Declarations

Ethics committee approval

Not applicable.

Informed consent

Not applicable being a review article.

Conflict of interest

None.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

5/6/2022

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.1007/s12055-022-01368-5

References

- 1.Coelho SG, Almeida AG. Marfan syndrome revisited: From genetics to the clinic. Rev Port Cardiol (Engl Ed). 2020;39:215–226. doi: 10.1016/j.repc.2019.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cauldwell M, Steer PJ, Curtis SL, Mohan A, Dockree S, Mackillop L, et al. Maternal and fetal outcomes in pregnancies complicated by Marfan syndrome. Heart. 2019;105:1725–31. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2019-314817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.MacCarrick G, Black JH, 3rd, Bowdin S, et al. Loeys-Dietz syndrome: a primer for diagnosis and management. Genet Med. 2014;16:576–87. doi: 10.1038/gim.2014.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pan J, Lei L, Zhao C, Wen J, Qin F, Dong F. Clinical characteristics and survival of patients with three major connective tissue diseases associated with pulmonary hypertension: A study from China. Exp Ther Med. 2021;22:925. doi: 10.3892/etm.2021.10357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Malfait F, Wenstrup RJ, De Paepe A. Clinical and genetic aspects of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, classic type. Genet Med. 2010;12:597–605. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181eed412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Byers PH, Belmont J, Black J, et al. Diagnosis, natural history, and management in vascular Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2017;175:40–47. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.31553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goldfinger JZ, Halperin JL, Marin ML, Stewart AS, Eagle KA, Fuster V. Thoracic aortic aneurysm and dissection. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:1725–39. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hong D, Scaletta Kent J, Kesler S. Cognitive profile of Turner syndrome. Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2009;15:270–8. doi: 10.1002/ddrr.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.von Knobelsdorff-Brenkenhoff F, Gruettner H, Trauzeddel RF, Greiser A, Schulz-Menger J. Comparison of native high-resolution 3D and contrast-enhanced MR angiography for assessing the thoracic aorta. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2014;15:651–8. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jet263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Veldhoen S, Behzadi C, Derlin T, et al. Exact monitoring of aortic diameters in Marfan patients without gadolinium contrast: intraindividual comparison of 2D SSFP imaging with 3D CE-MRA and echocardiography. Eur Radiol. 2015;25:872–82. doi: 10.1007/s00330-014-3457-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bannas P, Groth M, Rybczynski M, et al. Assessment of aortic root dimensions in patients with suspected Marfan syndrome: intraindividual comparison of contrast-enhanced and non-contrast magnetic resonance angiography with echocardiography. Int J Cardiol. 2013;167:190–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2011.12.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang H-H, Chiu H-H, Isaac Tseng W-Y, Peng H-H. Does altered aortic flow in marfan syndrome relate to aortic root dilatation? J Magn Reson Imaging. 2016;44:500–8. doi: 10.1002/jmri.25174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Geiger J, Hirtler D, Gottfried K, et al. Longitudinal evaluation of aortic hemodynamics in Marfan syndrome: new insights from a 4D flow cardiovascular magnetic resonance multi-year follow-up study. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2017;19:33. doi: 10.1186/s12968-017-0347-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nollen GJ, Groenink M, Tijssen JG, Van Der Wall EE, Mulder BJ. Aortic stiffness and diameter predict progressive aortic dilatation in patients with Marfan syndrome. Eur Heart J. 2004;25:1146–1152. doi: 10.1016/j.ehj.2004.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Whitlock MC, Hundley WG. Noninvasive imaging of flow and vascular function in disease of the aorta. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015;8:1094–1106. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2015.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Williams JA, Loeys BL, Nwakanma LU, et al. Early surgical experience with Loeys-Dietz: a new syndrome of aggressive thoracic aortic aneurysm disease. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007;83:S757–63. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2006.10.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Maio F, Pisano C, Caterini A, Bertoldo F, Ruvolo G, Farsetti P. Marfan syndrome in children: correlation between musculoskeletal features and cardiac Z-score. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2021;30:301–305. doi: 10.1097/BPB.0000000000000798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pham MHC, Ballegaard C, de Knegt MC, et al. Normal values of aortic dimensions assessed by multidetector computed tomography in the Copenhagen General Population Study. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2019;20:939–948. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jez012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zafar MA, Chen JF, Wu J, et al. Natural history of descending thoracic and thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysms. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2021;161:498–511.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2019.10.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Riambau V, Böckler D, Brunkwall J, et al. Editor's choice - Management of descending thoracic aorta diseases: clinical practice guidelines of the European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS) Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2017;53:4–52. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2016.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim JB, Kim K, Lindsay ME, et al. Risk of rupture or dissection in descending thoracic aortic aneurysm. Circulation. 2015;132:1620–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.015177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mansour AM, Peterss S, Zafar MA, et al. Prevention of aortic dissection suggests a diameter shift to a lower aortic size threshold for intervention. Cardiology. 2018;139:139–46. doi: 10.1159/000481930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Trimarchi S, Jonker FHW, Hutchison S, et al. Descending aortic diameter of 5.5 cm or greater is not an accurate predictor of acute type B aortic dissection. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011;142:e101–7 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Rylski B, Munoz C, Beyersdorf F, et al. How does descending aorta geometry change when it dissects? Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2018;53:815–21. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezx292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dudzinski DM, Isselbacher EM. Diagnosis and management of thoracic aortic disease. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2015;17:106. doi: 10.1007/s11886-015-0655-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saeyeldin AA, Velasquez CA, Mahmood SUB, et al. Thoracic aortic aneurysm: unlocking the "silent killer" secrets. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2019;67:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s11748-017-0874-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weinstein SL, Zavala DC, Ponseti IV. Idiopathic scoliosis: long-term follow-up and prognosis in untreated patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1981;63:702–12. doi: 10.2106/00004623-198163050-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Helder MRK, Schaff HV, Dearani JA, et al. Management of mitral regurgitation in Marfan syndrome: Outcomes of valve repair versus replacement and comparison with myxomatous mitral valve disease. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014;148:1020–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2014.06.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cañadas V, Vilacosta I, Bruna I, Fuster V. Marfan syndrome. Part 2: treatment and management of patients. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2010;7:266–76 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Keane MG, Pyeritz RE. Medical management of Marfan syndrome. Circulation. 2008;117:2802–13. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.693523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chiu H-H, Wu M-H, Wang J-K, et al. Losartan added to β-blockade therapy for aortic root dilation in Marfan syndrome: a randomized, open-label pilot study. Mayo Clin Proc. 2013;88:271–6. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2012.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jondeau G, Milleron O, Boileau C. Marfan sartan saga, episode X. Eur Heart J. 2020;41:4188–4190. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baghirzada L, Krings T, Carvalho JCA. Regional anesthesia in Marfan syndrome, not all dural ectasias are the same: a report of two cases. Can J Anaesth. 2012;59:1052–7. doi: 10.1007/s12630-012-9778-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tshomba Y, Leopardi M, Mascia D, et al. Automated pressure-controlled cerebrospinal fluid drainage during open thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm repair. J Vasc Surg. 2017;66:37–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2016.11.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Engle J, Safi HJ, Miller CC, 3rd, et al. The impact of diaphragm management on prolonged ventilator support after thoracoabdominal aortic repair. J Vasc Surg. 1999;29:150–6. doi: 10.1016/S0741-5214(99)70356-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schepens MAAM. Left heart bypass for thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm repair: technical aspects. Multimed Man Cardiothorac Surg. 2016;2016:mmv039 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Tshomba Y, Kahlberg A, Melissano G, et al. Comparison of renal perfusion solutions during thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm repair. J Vasc Surg. 2014;59:623–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2013.09.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Carrel TP, Signer C. Separate revascularization of the visceral arteries in thoracoabdominal aneurysm repair. Ann Thorac Surg. 1999;68:573–5. doi: 10.1016/S0003-4975(99)00574-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Piazza KM, Black JH, 3rd, Glebova NO. Treatment of a complex thoracoabdominal aneurysm and dissection with a branched graft. JAAPA. 2015;28:44–9. doi: 10.1097/01.JAA.0000471608.54160.0d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dardik A, Perler BA, Roseborough GS, Williams GM. Aneurysmal expansion of the visceral patch after thoracoabdominal aortic replacement: an argument for limiting patch size? J Vasc Surg. 2001;34:405–9. doi: 10.1067/mva.2001.117149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Preventza O, Mohammed S, Cheong BY, et al. Endovascular therapy in patients with genetically triggered thoracic aortic disease: applications and short- and mid-term outcomes. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2014;46:248–53. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezt636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marcheix B, Rousseau H, Bongard V, et al. Stent grafting of dissected descending aorta in patients with Marfan’s syndrome: mid-term results. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2008;1:673–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2008.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Geisbüsch P, Kotelis D, von Tengg-Kobligk H, Hyhlik-Dürr A, Allenberg J-R, Böckler D. Thoracic aortic endografting in patients with connective tissue diseases. J Endovasc Ther. 2008;15:144–9. doi: 10.1583/07-2286.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Amako M, Spear R, Clough RE, et al. Total endovascular aortic repair in a patient with Marfan syndrome. Ann Vasc Surg. 2017;39:289.e9–289.e12. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2016.07.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Numata S, Tsutsumi Y, Ohashi H. Complications and surgical conversion after total aortic repair using endovascular repair in patients with Marfan syndrome. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2015;47:e155–7. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezu517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mohammadi S, Normand J-P, Voisine P, Dagenais F. Thoracic aortic stent grafting in patients with connective tissue disorders: a word of caution. Innovations (Phila). 2007;2:184–7. doi: 10.1097/imi.0b013e31815887e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Waterman AL, Feezor RJ, Lee WA, et al. Endovascular treatment of acute and chronic aortic pathology in patients with Marfan syndrome. J Vasc Surg. 2012;55:1234–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2011.11.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Squizzato F, Oderich GS, Bower TC, et al. Long-term fate of aortic branches in patients with aortic dissection. J Vasc Surg. 2021;74:537–546.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2021.01.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schoenhoff FS, Yildiz M, Langhammer B, et al. The fate of nonaortic arterial segments in Marfan patients. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2019;157:2150–2156. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2018.10.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Aru RG, Richie CD, Badia DJ, et al. Hybrid repair of Type B aortic dissection with thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysmal degeneration in the setting of Marfan syndrome. Vasc Endovascular Surg. 2021;55:619–622. doi: 10.1177/1538574420988279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Roselli EE, Idrees JJ, Lowry AM, et al. Beyond the aortic root: staged open and endovascular repair of arch and descending aorta in patients with connective tissue disorders. Ann Thorac Surg. 2016;101:906–12. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2015.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Di Marco L, Murana G, Leone A, et al. Hybrid repair of thoracoabdominal aneurysm: An alternative strategy for preventing major complications in high risk patients. Int J Cardiol. 2018;271:31–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2018.04.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Glebova NO, Cameron DE, Black JH., 3rd Treatment of thoracoabdominal aortic disease in patients with connective tissue disorders. J Vasc Surg. 2018;68:1257–1267. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2018.06.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Arnaoutakis DJ, Scali ST, Beck AW, et al. Comparative outcomes of open, hybrid, and fenestrated branched endovascular repair of extent II and III thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysms. J Vasc Surg. 2020;71:1503–1514. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2019.08.236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]