Abstract

Acute aortic syndrome is a broad clinical entity that encompasses several pathologies. Aortic dissection is a well-studied disorder, but the other most prominent disorders within the scope of acute aortic syndrome, penetrating aortic ulcer and intramural hematoma, are more nebulous in terms of their pathophysiology and treatment strategies. While patient risk factors, presenting symptoms, and medical and surgical management strategies are similar to those of aortic dissection, there are indeed nuanced differences unique to penetrating aortic ulcer and intramural hematoma that surgeons and acute care providers must consider while managing patients with these diagnoses. The aim of this review is to summarize patient demographics, pathophysiology, workup, and treatment strategies that are unique to penetrating aortic ulcer and intramural hematoma.

Keywords: Acute aortic syndrome, Penetrating aortic ulcer, Intramural hematoma

Introduction

Penetrating Aortic Ulcer (PAU) and Intramural Hematoma (IMH) are both part of a clinical spectrum of acute aortic syndromes (AAS) that can independently lead to aortic dissection (AD) in the ascending and descending aorta, yet have independent pathophysiological processes. [1] Their exact mechanisms are unclear, and ideal diagnostic modalities and management can differ. This review will highlight the key elements, clinical aspects, risk factors, necessary imaging, management strategies, and related outcomes distinguishing PAUs from IMHs.

Epidemiology

The reported incidence of AAS is approximately 2.6–3.5 cases per 100,000 person/year. [1] Within this spectrum of disease, it is estimated that PAU accounts for 2.3–7.5% of AAS. [2, 3] The term PAU was coined by Shennan in 1934, [4] but it was not until 1986 that Stanson and colleagues from the Mayo Clinic identified PAU as a unique clinical entity. [5] PAU is most commonly located in the descending thoracic aorta. One series of 388 patients identified PAU in the descending thoracic aorta in 62% of cases, the abdominal aorta in 31% or the aortic arch in 7%. [6] These lesions may often be identified incidentally in the absence of symptoms. [2] Risk factors for isolated PAU are comparable with risk factors for atherosclerotic vascular disease, including male gender, advanced age, history of tobacco use, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and coronary artery disease. [4, 7]

IMH accounts for 5–20% of the cases presenting with AAS [8] with incidence as high as 30% of AAS in studies from Asia. [2, 9] In a review of 1010 patients in the International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection (IRAD), IMH was present in 58 patients (5.7%). [10] Similar to patients with PAUs, those with IMH are typically older than patients with AD and both are most frequently found in the descending thoracic aorta and are less likely to extend to the abdominal aorta. An IMH has a variable course, and may progress to dissection or aneurysm formation, or may stabilize or resorb. [11–13] The location of IMH is a key risk factor, as IMH located in the ascending aorta is an independent risk factor for progression within 30 days of presentation. [14] Other predictors of complications in IMH are aortic diameter ≥ 50 mm, recurrent or persistent pain despite adequate medical treatment, presence of concomitant PAU or ulcer like projections in the involved segment, evidence of malperfusion, enlarging aortic diameter, maximum hematoma thickness (≥ 10 mm), or evidence of aortic root involvement, such as pericardial effusion, tamponade or aortic insufficiency. [4]

Pathophysiology

PAU is an atherosclerotic crater-like ulcer that invades the internal elastic lamina. While this process may lead to IMH formation in the medial layer of the aorta, PAU is an isolated finding in 20% of cases. [8] It is thought that in these cases of isolated PAU, chronic atherosclerotic disease and medial fibrosis surrounding the lesion may limit the transmission of blood into the medial layer, thus preventing the propagation of hematoma. The size of PAU may reach up to 2.5 cm in diameter and 3 mm in depth, [12] and may be solitary or multiple. Microscopically, ulcers characteristically have medial cholesterol deposition resulting in degeneration of the media. [12] PAU can be an asymptomatic phenomenon, with only 20–54% of patients demonstrating symptoms at presentation. [15] Patients can present with symptoms of chest, back, or abdominal pain which is thought to be due to the rapid stretching of the aortic adventitia resulting in stimulation of the aortic nerve plexus. Thoracic PAUs are more likely to be symptomatic than those found in the abdominal aorta. Rarely, PAUs develop thrombi on the surface of the ulcer, which may result in distal embolization. These are more frequently abdominal PAUs rather than thoracic. [16] In up to 40% of cases, PAU may progress to dissection or rupture. [17]

IMH, described first by Krukenberg in 1920, [18] is primarily accepted as a disease of the aortic media. The predominant theory of the mechanism of IMH formation is the rupture of vasa vasorum, a network of small vessels supplying the outer and middle aortic media, resulting in separation of layers of the media without an intimal defect, [1, 4, 8, 19–21] though this remains subject to debate due to the paucity of scientific data validating this mechanism. IMH has been described as a thrombosed false lumen of a short segment AD, but this remains controversial. IMH tends to be located in the outer media, closer to the adventitia than AD, which are ordinarily found in the inner media according to Uchida, et al. [22] Improvement of cross-sectional imaging technologies have allowed for higher-resolution imaging, thus yielding higher detection rates of smaller intimomedial tears. [23, 24] Furthermore, there are reports of iatrogenic IMH following endovascular instrumentation, which implies some plausible violation of the intima. [25] Regardless of mechanism, it is known that IMH results in medial degeneration and loss of elasticity, thus reducing the aorta’s innate resistance to hemodynamic stress and increasing risk of aneurysmal degeneration or dissection. [22, 26, 27]

Chronic hypertension is a condition that is present in the majority of patients with AAS and is associated with atherosclerosis of the vasa vasorum. Classically, in a patient experiencing a hypertensive crisis, systemic vasoconstriction occurs. At the level of the vasa vasorum, a reduction of blood flow can result in ischemia of the aortic media. [28] This mechanism is an accepted explanation for the development AD, but it does not fully support the proposed mechanisms of IMH formation. One histopathological study evaluating the role of the vasa vasorum in AD found a rather high rate of IMH in their case series, as 47% of specimens did not exhibit an entry tear [29]; their analysis showed that in 76% of specimens, the vasa vasorum exhibited changes consistent with chronic hypertension, such as muscular hyperplasia, elastosis, intimal fibrosis, luminar obstruction, tortuosity, and erythrocyte extravasation. These changes within the vasa vasorum have a major impact on the hemodynamic environment of the aortic media. Chronic hypertensive changes of the vasa vasorum reduces local blood flow, and thus leads to reduction of nutrient and oxygen delivery to the media. In this pathophysiologic model, ischemia of the aortic media results in necrosis of medial smooth muscle cells, medial thinning, and degradation of elastin in the media, thus increasing the risk of an acute aortic event. [30, 31]

Diagnosis and imaging

The diagnosis of PAUs and IMHs are mainly based on imaging modalities. Patients presenting with any AAS generally complain of severe chest or back pain, with variations in presenting signs and symptoms relating to involved arterial branches. [19] Differentiating PAU, IMH, and AD based on clinical findings alone is challenging, as there is significant overlap in symptoms. Initial workup in this setting will generally include an EKG and chest X-ray. An EKG will often rule out ischemia or infarction. Plain films of the chest can show widening of the mediastinum, but chest X-ray findings only have a sensitivity of 61–67% for acute aortic pathologies, [32] and should not be relied upon for definitive diagnosis. There is a good foundation of evidence that D-dimer levels of >500 μg/L are sensitive for an acute AD and IMH, and also have an excellent negative predictive value. [19] Interestingly, D-dimer has not been shown to be as effective in the diagnosis of PAU, with sensitivity and specificity of 64% and 67%, respectively.

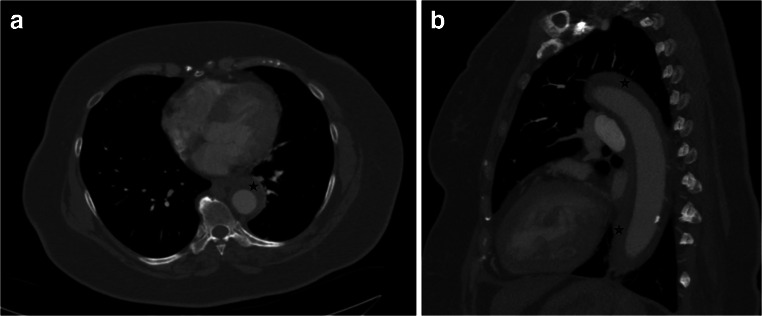

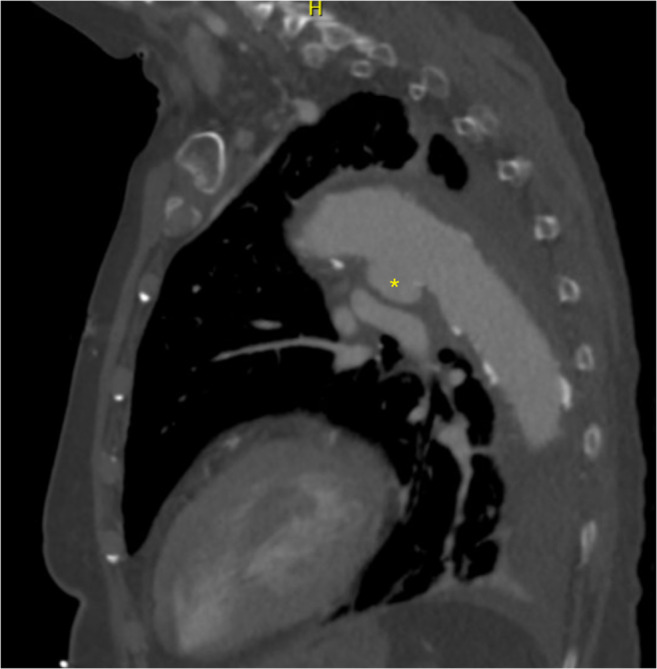

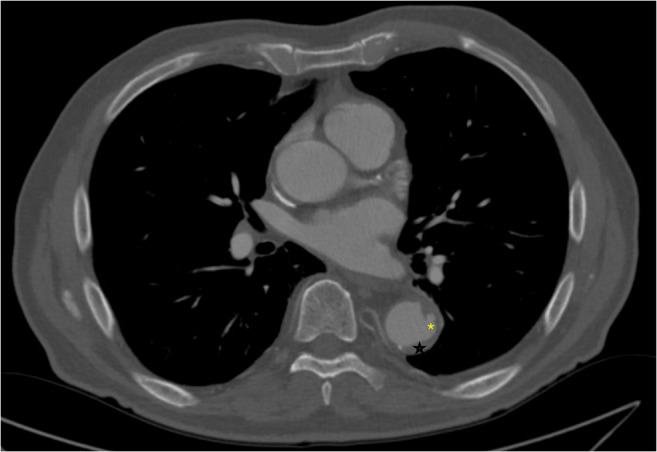

The above findings can aid in raising suspicion for AAS, but securing a diagnosis generally requires cross-sectional imaging. Computed tomography angiography (CTA) is usually the study of choice for identifying AAS, given expedient scanning time, easy accessibility, and superb sensitivity, specificity, and negative predictive value. [19, 33] PAU appears on CTA as a crater-like outpouching of contrast projecting into a thickened aortic wall (Fig. 1), often times with surrounding atherosclerotic changes. [2] IMH will usually appear as a uniformly hyperattenuated, non-enhancing crescentic thickening of the aortic wall >7 mm without a clear intimomedial flap (Fig. 2). [2, 22] As previously mentioned, PAU may lead to IMH, and thus both will coexist on the same imaging study (Fig. 3).

Fig. 1.

Sagittal section of a CT angiogram of the chest demonstrating penetrating aortic ulcer in segment 3 of the aorta, denoted by asterisk

Fig. 2.

Axial section of a CT angiogram of the chest demonstrating intramural hematoma, indicated by stars, at the level of T7 (a). Sagittal section of the same study (b)

Fig. 3.

Sagittal section of a CT angiogram of the chest demonstrating penetrating aortic ulcer (asterisk) at the level of T8 with associated intramural hematoma (star)

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is highly sensitive and specific for AASs, though is not as frequently utilized due to lower availability and slower scan time. MRI can be advantageous as ionizing radiation is not needed for image acquisition, nor is iodinated contrast. Furthermore, MRI is especially useful in identifying the chronicity of IMH. Early in the evolution of IMH, the hematoma shows iso-intensity on T1 imaging and hyper-intensity on T2 imaging. [34] However after the first 1–2 days, there is evolution to a hyper-intense signal in both T1 and T2 MRI images due to methemoglobin accumulation. [19] This contrasts with mural thrombus which is hypo-intense or iso-intense in both T1 and T2 images.

Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) serves as a useful tool in the early evaluation of patients with chest pain, but is limited in the diagnosis of AAS. TTE can identify aortic valve insufficiency and pericardial effusion, which may be sequelae associated with ascending aortic pathology. [19] In select circumstances, proximal AAS can be identified on TTE, but sensitivity is insufficient to effectively rule out AAS. [35] Transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) is clearly superior to TTE in the diagnosis of AAS. [36] When done well, PAU can be identified on TEE as a characteristic crater-like projection into the aortic wall, occasionally with surrounding atheromatous plaque as seen on CTA. [36] When false lumen flow is present, AD can clearly be differentiated from IMH, though the diagnosis becomes more difficult if AD with false lumen thrombosis is present. Despite its advantage over TTE, TEE is not without its limitations. TEE requires an experienced sonographer, adequate sedation, and tight blood pressure control in order to safely yield high-quality images. Furthermore, TEE is still subject to the same imaging artifacts as TTE, such as acoustic shadowing from surrounding structures, such as the trachea and mainstem bronchi. [2, 36]

Conventional angiography is rarely utilized as a primary diagnostic modality in the spectrum of AAS, as the above-mentioned non-invasive cross sectional imaging modalities have excellent sensitivity and specificity without the need for procedural resources. [37]

Treatment

Nonsurgical therapy

As with other forms of AAS, medical therapy to optimize blood pressure and heart rate, and reduce aortic wall stress is required to initially treat patients with PAU and IMH. Intravenous beta-blockers and non-dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers are used to keep the blood pressure between 100 to 120 mmHg, and heart rate between 60 and 80 bpm. [3, 12] Adequate pain control is also an important consideration, as uncontrolled pain may result in sympathetic nervous system-mediated heart rate increase. [3] As with AD, patients presenting with complicated type B PAU and IMH should be considered for surgical management. Complicated disease is indicated by persistent or recurrent pain despite adequate control of hypertension, uncontrolled hypertension, aortic expansion on repeat imaging, hemodynamic instability, organ ischemia, maximum aortic diameter > 55 mm and rupture. In addition, surgical repair is indicated for any of the following features: PAU base >20 mm and depth > 15 mm, IMH with significant periaortic hemorrhage. [3, 38, 39] A single-center retrospective study of 108 patients with either PAU (n = 53) or IMH (n = 55) compared the outcomes between patients receiving medical or surgical management, on the basis of ruptured state (defined as a realized rupture or impending rupture) or non-ruptured state. [40] In patients with either PAU or IMH who were triaged into the non-ruptured state group, 82% and 68% of patients, respectively, underwent initial medical management rather than surgical management. Survival to discharge in both groups was 100% if patients presented with a non-ruptured state. Conversely, of patients with either PAU or IMH presenting with a rupture state who were not candidates for surgical intervention due to age or comorbidities, none survived to discharge. It should be noted that as in AD, type A lesions should be considered for initial surgical management, while in type B lesions, medical management with serial imaging is appropriate in the absence of the above-described complicating features. [40, 41] Some studies have indicated, however, that while medically-managed type A lesions are at risk of complications, medical management can be a temporizing short-term measure for transfer to an appropriate specialty center for definitive surgical repair. [42]

Endovascular surgery

Ascending aorta and aortic arch

While open surgery remains the generally accepted standard for operative management of proximal IMH and PAU, novel techniques are currently under investigation. Thoracic endografts have been deployed in the ascending aorta in cases of AD with no mortality at 3 years of follow up. [43] In cases where there is aneurysm or dissection of branches of the arch, chimney and snorkel techniques have been established as technically feasible, [44] and light amplified by the stimulated emission of radiation (LASER) fenestration for left subclavian artery with subsequent stent placement can also be performed. [45] It should be noted, however, that the use of endovascular techniques for type A PAU and IMH have not been well studied and while these techniques could theoretically be utilized safely, disease-specific outcomes have not been defined and these interventions should be considered experimental or considered under compassionate use access.

Descending aorta

While medical management is critical in the early stabilization of symptomatic patients with PAU or IMH, definitive repair is often needed to optimize outcomes. As with AD, IMH and PAU with evidence of rupture or hemodynamic instability should prompt urgent intervention. When surgery is considered, endovascular techniques are considered first-line therapy. [41, 46] Given that PAU generally exists in short segments of aorta, complete coverage of the ulcer with a single stent graft is often feasible. [38] Conversely, greater length of coverage of the thoracic aorta is often necessary in treatment of IMH; one group reported an average of 2 stent grafts for complete coverage in a cohort of 44 patients. [45] Follow-up imaging of patients who underwent thoracic endovascular aortic repair (TEVAR) in this study had a marked decrease in the size of IMH on volumetric analysis, from 103 cm3 to 14 cm3. [45]

Open surgery

Ascending aorta

Most experts agree that symptomatic PAUs or IMHs in the aorta before the left subclavian artery (LSA) have a higher likelihood of progressing to dissection or rupture and should undergo surgical repair in an urgent or emergent basis. If a patient is stable with an IMH seen in the aorta proximal to the LSA, expert center management includes consideration of deferred open surgical repair for up to 72 h allowing time for optimization, advanced imaging, and the preferred team to assemble. [42] From a technical standpoint, the operative approach is the same as that of type A AD. [47]

Descending aorta

Due to the accessibility and comparative morbidity and mortality profile of TEVAR, PAU and IMH in the descending aorta are seldom treated with open surgery. There are unique considerations such as patient’s aortic anatomy or habitus that might preclude an endovascular approach to treatment, and in those very unique cases, open surgery may be considered. In patients with hemodynamic instability or evidence of rupture requiring urgent repair, an endovascular approach is still the technique of choice for surgical management. Mortality of open repair of type B IMH or PAU is 15.9% versus 7.2% for TEVAR in the acute phase of treatment. [48] Consensus guidelines suggest that endovascular surgery is the preferred strategy in descending aortic AAS when feasible. Open repair should be reserved for patients with acceptable peri-operative risk estimates of morbidity and mortality and those with unsuitable/limited endovascular options.

Summary

Penetrating Aortic Ulcer and Intramural Hematoma are both clinically complex and part of a clinical spectrum of acute aortic syndromes that can independently lead to aortic dissection in the ascending and descending aorta, and like aortic dissection, are lifelong disorders that affect the entire aorta. Treatment strategies include reduction in aortic wall stress and tailoring the surgical approach to the patient and lesion.

Funding

None.

Declarations

Drs. Warner and Bhamidipadi have no conflicts of interest pertinent to this manuscript. Dr. Abraham is a paid consultant for the Medtronic Aortic Advisory Board, a paid consultant as an Advanced Aortic Intervention proctor, and a paid consultant for WL Gore as a Clinical Events Committee member for the Gore Conformable Stent Graft Clinical Trial.

As a review manuscript, there were no human or animal subjects involved in our work, and thus, informed consent was not required.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Corvera JS. Acute aortic syndrome. Ann Cardiothorac Surg. 2016;5:188–193. doi: 10.21037/acs.2016.04.05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Evangelista A, Maldonado G, Moral S, et al. Intramural hematoma and penetrating ulcer in the descending aorta: differences and similarities. Ann Cardiothorac Surg. 2019;8:456–470. doi: 10.21037/acs.2019.07.05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Korepta LM, Aulivola B. Aortic intramural hematomas and penetrating aortic ulcerations: indications for treatment versus surveillance. Endovascular Today. 2020;19:78–82. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lansman SL, Saunders PC, Malekan R, Spielvogel D. Acute aortic syndrome. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;140:S92–S97. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2010.07.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stanson AW, Kazmier FJ, Hollier LH, et al. Penetrating atherosclerotic ulcers of the thoracic aorta: natural history and clinicopathologic correlations. Ann Vasc Surg. 1986;1:15–23. doi: 10.1016/S0890-5096(06)60697-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nathan DP, Boonn W, Lai E, et al. Presentation, complications, and natural history of penetrating atherosclerotic ulcer disease. J Vasc Surg. 2012;55:10–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2011.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cho KR, Stanson AW, Potter DD, Cherry KJ, Schaff HV, Sundt TM., 3rd Penetrating atherosclerotic ulcer of the descending thoracic aorta and arch. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2004;127:1393–1399. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2003.11.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sundt TM. Intramural hematoma and penetrating atherosclerotic ulcer of the aorta. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007;83:S835–S841. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2006.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ho HH, Cheung CW, Jim MH, et al. Type A aortic intramural hematoma: clinical features and outcomes in Chinese patients. Clin Cardiol. 2011;34:E1–E5. doi: 10.1002/clc.20481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Evangelista A, Mukherjee D, Mehta RH, et al. Acute intramural hematoma of the aorta: a mystery in evolution. Circulation. 2005;111:1063–1070. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000156444.26393.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nishigami K, Tsuchiya T, Shono H, Horibata Y, Honda T. Disappearance of aortic intramural hematoma and its significance to the prognosis. Circulation. 2000;102:III243–III247. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.suppl_3.iii-243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dev R, Gitanjali K, Anshuman D. Demystifying penetrating atherosclerotic ulcer of aorta: unrealised tyrant of senile aortic changes. J Cardiovasc Thorac Res. 2021;13:1–14. doi: 10.34172/jcvtr.2021.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alomari IB, Hamirani YS, Madera G, Tabe C, Akhtar N, Raizada V. Aortic intramural hematoma and its complications. Circulation. 2014;129:711–716. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.001809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nienaber CA, Richartz BM, Rehders T, Ince H, Petzsch M. Aortic intramural haematoma: natural history and predictive factors for complications. Heart. 2004;90:372–374. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2003.027615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Salim S, Machin M, Patterson BO, Bicknell C. The management of penetrating aortic ulcer. Hearts. 2020;1:5–13. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nickol J, Richards T, Mullins J. Cholesterol embolization syndrome from penetrating aortic ulcer. Cureus. 2020;12:e8670. doi: 10.7759/cureus.8670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.DeCarlo C, Latz CA, Boitano LT, et al. Prognostication of asymptomatic penetrating aortic ulcers: a modern approach. Circulation. 2021;144:1091–1101. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.121.054710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krukenberg E. Beitrage zur Frage des Aneurysma dissecans. Beitr Pathol Anat Allg Pathol. 1920;67:329–351. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ferrera C, Vilacosta I, Cabeza B, et al. Diagnosing aortic intramural hematoma: Current perspectives. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2020;16:203–213. doi: 10.2147/VHRM.S193967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ganaha F, Miller DC, Sugimoto K, et al. Prognosis of aortic intramural hematoma with and without penetrating atherosclerotic ulcer: a clinical and radiological analysis. Circulation. 2002;106:342–348. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000022164.26075.5a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chao CP, Walker TG, Kalva SP. Natural history and CT appearances of aortic intramural hematoma. Radiographics. 2009;29:791–804. doi: 10.1148/rg.293085122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goldberg JB, Kim JB, Sundt TM. Current understandings and approach to the management of aortic intramural hematomas. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014;26:123–131. doi: 10.1053/j.semtcvs.2014.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gutschow SE, Walker CM, Martínez-Jiménez S, Rosado-de-Christenson ML, Stowell J, Kunin JR. Emerging concepts in intramural hematoma imaging. Radiographics. 2016;36:660–674. doi: 10.1148/rg.2016150094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Uchida K, Imoto K, Karube N, et al. Intramural haematoma should be referred to as thrombosed-type aortic dissection. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2013;44:366–369. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezt040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Song J-K. Diagnosis of aortic intramural haematoma. Heart. 2004;90:368–371. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2003.027607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Coady MA, Rizzo JA, Elefteriades JA. Pathologic variants of thoracic aortic dissections. Penetrating atherosclerotic ulcers and intramural hematomas. Cardiol Clin. 1999;17:637–657. doi: 10.1016/s0733-8651(05)70106-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.von Kodolitsch Y, Csösz SK, Koschyk DH, et al. Intramural hematoma of the aorta.predictors of progression to dissection and rupture. Circulation. 2003;107:1158–1163. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000052628.77047.ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pereira AH. Rupture of vasa vasorum and intramural hematoma of the aorta: a changing paradigma. J Vasc Bras. 2010;9:57–60. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Osada H, Kyogoku M, Ishidou M, Morishima M, Nakajima H. Aortic dissection in the outer third of the media: what is the role of the vasa vasorum in the triggering process? Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2013;43:e82–e88. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezs640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baikoussis NG, Apostolakis EE, Papakonstantinou NA, et al. The implication of vasa vasorum in surgical diseases of the aorta. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2011;40:412–417. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2010.11.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Heistad DD, Marcus ML, Larsen GE, Armstrong ML. Role of vasa vasorum in nourishment of the aortic wall. Am J Physiol. 1981;240:H781–H787. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1981.240.5.H781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.von Kodolitsch Y, Nienaber CA, Dieckmann C, et al. Chest radiography for the diagnosis of acute aortic syndrome. Am J Med. 2004;116:73–77. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2003.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Evangelista A, Isselbacher EM, Bossone E, et al. Insights from the International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection: A 20-year experience of collaborative clinical research. Circulation. 2018;137:1846–1860. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.031264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sahn DJ, Goldberg SJ, Allen HD, et al. A new technique for noninvasive evaluation of femoral arterial and venous anatomy before and after percutaneous cardiac catheterization in children and infants. Am J Cardiol. 1982;49:349–355. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(82)90512-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Evangelista A, Flachskampf FA, Erbel R, et al. Echocardiography in aortic diseases: EAE recommendations for clinical practice. Eur J Echocardiogr. 2010;11:645–658. doi: 10.1093/ejechocard/jeq056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Evangelista A, Maldonado G, Gruosso D, et al. The current role of echocardiography in acute aortic syndrome. Echo Res Pract. 2019;6:R53–R63. doi: 10.1530/ERP-18-0058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nienaber CA. The role of imaging in acute aortic syndromes. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013;14:15–23. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jes215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Eggebrecht H, Plicht B, Kahlert P, Erbel R. Intramural hematoma and penetrating ulcers: indications to endovascular treatment. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2009;38:659–665. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2009.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jánosi RA, Gorla R, Tsagakis K, et al. Thoracic endovascular repair of complicated penetrating aortic ulcer: An 11-year single-center experience. J Endovasc Ther. 2016;23:150–159. doi: 10.1177/1526602815613790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chou AS, Ziganshin BA, Charilaou P, Tranquilli M, Rizzo JA, Elefteriades JA. Long-term behavior of aortic intramural hematomas and penetrating ulcers. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2016;151(361-72):373.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2015.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Oderich GS, Kärkkäinen JM, Reed NR, Tenorio ER, Sandri GA. Penetrating aortic ulcer and intramural hematoma. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2019;42:321–334. doi: 10.1007/s00270-018-2114-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Watanabe S, Hanyu M, Arai Y, Nagasawa A. Initial medical treatment for acute type A intramural hematoma and aortic dissection. Ann Thorac Surg. 2013;96:2142–2146. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2013.06.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li Z, Lu Q, Feng R, et al. Outcomes of endovascular repair of ascending aortic dissection in patients unsuitable for direct surgical repair. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68:1944–1954. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bosiers MJ, Donas KP, Mangialardi N, et al. European multicenter registry for the performance of the chimney/snorkel technique in the treatment of aortic arch pathologic conditions. Ann Thorac Surg. 2016;101:2224–2230. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2015.10.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lavingia KS, Ahanchi SS, Redlinger RE, Udgiri NR, Panneton JM. Aortic remodeling after thoracic endovascular aortic repair for intramural hematoma. J Vasc Surg. 2014;60:929–935. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2014.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Riambau V, Böckler D, Brunkwall J, et al. Editor's Choice - management of descending thoracic aorta diseases: Clinical practice guidelines of the European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS) Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2017;53:4–52. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2016.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Al Rstum Z, Tanaka A, Eisenberg SB, Estrera AL. Optimal timing of type A intramural hematoma repair. Ann Cardiothorac Surg. 2019;8:524–530. doi: 10.21037/acs.2019.07.08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Evangelista A, Czerny M, Nienaber C, et al. Interdisciplinary expert consensus on management of type B intramural haematoma and penetrating aortic ulcer. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2015;47:209–217. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezu386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]