Abstract

Infection of the aorta continues to be a clinical challenge with high morbidity and mortality. The incidence varies between 0.6 and 2.6%. There has been a steady increase in graft infections, especially endograft infections, due to increased procedures (0.2 to 5%). Staphylococcus species remains the most common organism; however, gram-negative and rare causative agents are also reported. The clinical presentation can be very diverse and a high degree of suspicion is necessary to diagnose them. Sometimes, they may present as an emergency with rupture or fistulation. Diagnosis is based on a triad of clinical features, microbial cultures and imaging. Culture-specific antibiotics are mandatory during the entire course, but seldom cure alone. Surgical management remains the standard of care and involves an integrated approach involving debridement, reconstruction and use of adjuncts. Various aortic substitutes have been described with advantages and limitations. Pericardial tube grafts have emerged as a good option. Endo-vascular options are practiced mostly as a bridge to definitive surgery. A small role for conservative management is described. Aortic fistulation to the gut and airway carries a very high mortality. There are no large series in the literature to define guideline-directed treatment and most often it is a customized solution. The 30-day mortality remains close to 30%. Outcomes depend on multiple factors including patient’s age, the timing of presentation, diagnosis, causative organism, host status and the treatment strategy adopted.

Keywords: Aortic infections, Aortic graft infections, Omentopexy, Pericardial tube, Stent graft infections, Graft conservation

Introduction

There is no disease more conducive to clinical humility than aneurysm of the aorta

- Sir William Osler

Infections of the aorta have always been a challenge and continue to be despite advancements in diagnosis, antibiotics and surgical management. The mortality and morbidity continue to be high. Rapid strides in the field of interventions and vascular procedures have thrown open a new spectrum of problems and infections related to them.

The first-ever description of an infection in the vascular system was by Sir William Osler in 1885, when he described bead-like aneurysms in the aortic arch secondary to aortic valve vegetations and named it mycotic aneurysm—which was a misnomer as a vast majority of them were bacterial in origin and not fungal [1]. Infective aneurysms are a better nomenclature and can be caused by septic emboli, as described by Osler, and may also occur due to seeding on a pre-existing aneurysm, as described by Sommerville in 1959 [1, 2].

Most infected aneurysms are surgical emergencies and the incidence varies between 0.7 and 2.6% in different case series. Graft infections constitute ~ 0.2 to 5%. There has been an increased incidence after endovascular therapies, which contribute close to 0.7% of all infections and are a major clinical problem today [3]. Many of these patients are elderly with co-morbidities making it more complex. Almost all cases need aggressive surgical management in addition to an extended antibiotic regimen. There are no defined guidelines and treatment strategies have to be customized.

Aetiology, pathogenesis and bacteriology

The aetiology has changed significantly over the years. The vascular endothelium is relatively resistant to the primary seeding of micro-organisms. Direct microbial arteritis occurs in immunocompromised individuals, predisposed by some breach in the vessel wall, like an atherosclerotic plaque, which provides a nesting place for microbes (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Aetiology, causative agents and common location of different infections of the aorta (adapted from [4, 5])

Although there is no obvious gender predilection, Oderich et al. showed male preponderance [6]. They also mentioned in their series that 70% of patients with infections had comorbidities or immunocompromised status such as chronic kidney disease, diabetes mellitus, steroid use and other chronic illnesses. Approximately 50% of the patients have a history of recent infection at other sites in the body—pneumonia, urinary infection, cholecystitis, endocarditis, etc.—which predisposes the patient to infections of the aorta [6]. The original mycotic aneurysm defined and explained by Sir William Osler secondary to embolization constitutes less than 10% of all arterial infections [1, 7]. Most of them tend to form a saccular aneurysm or a pseudoaneurysm.

Infections on a pre-existing aneurysm are seen more commonly in large aneurysms, especially in the aorta with clots acting as a nidus. This again can be due to seeding or as a result of contiguous spread. Jarrett demonstrated bacterial growth in 4% of thrombi in asymptomatic degenerative aneurysms and suggested a correlation to an increased chance of rupture [8]. Muller et al., in 2001, substantiated the same demonstrating a 85% positive culture of the aneurysm sac among ruptured aneurysms [9]. Current literature suggests a polymicrobial infection of degenerative aortic aneurysms [10].

Secondary infections are the ones that occur due to interventions and invasion of vascular integrity. Iatrogenic/traumatic causes, secondary to invasive vascular procedures, are probably the most common causes of infections today. In the aorta, endovascular or surgical grafts are a significant cause and are a challenge to manage. The Canadian multicentre study reported an incidence of 0.2% for abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) open repair with synthetic grafts [11]. The cumulative incidence of aortic graft infections (AGI) at 2 years following open aortic procedures stands at around ~ 5% [12]. The incidence of infections in endovascular stent-grafts are said to be 1–5% and one of the common cause is contamination from the skin [5, 13]. Stent graft infection (SGI) was reported for the first time by Chalmers in 1993 [14]. SGI, as a complication of Thoracic Endo-Vascular Aortic Repair (TEVAR)/Endo-Vascular Aneurysm Repair (EVAR), is a well-known entity now and being increasingly reported. Although the incidence is low − 0.5 to 1.0%, the mortality rate remains high at 11% and 28–30% at 1 month and 1 year respectively, despite treatment [15–18]. Endovascular grafts take at least 6 years to form the neo-intima, thus making them susceptible to infection in the interim period [19, 20]. There have been reports of infected stent grafts causing contiguous infections into the spine and vice versa [15, 21].

The pores and the interstices of the grafts provide a more favourable nesting place for the bacteria to stay, colonize and form biofilms. Biofilms are a combination of extracellular matrix and microbes lining the surfaces like grafts rendering the organisms resistant [22]. Certain microbes have special characteristics; e.g., Staphylococcus species (sp.) form a glycocalyx that makes a strong bond with the graft surfaces [23]. Polyethylene Terephthalate (Dacron) is more prone for bacterial seeding than polytetrafluroethylene (PTFE) and is reported to be several times stronger. The net result is the activation of the inflammatory cascade impeding neutrophil function, vascular ingrowth and endothelialization. This forms the basis of vascularized pedicle as a treatment adjunct. Contamination during the procedure and post-procedure wound infection seems to be the major cause of graft/stent infections, rather than bacterial seeding. Emergency procedures and prolonged operative time have a direct relationship to the development of prosthetic infections. Mechanical erosion into the gut may be compounded by infection and is usually catastrophic.

The contiguous spread of infection from adjacent structures is another cause. Infections in the retroperitoneum/psoas/spine can infect the aorta. There have also been reports of infected aneurysms and stent grafts causing contiguous infections into the spine [15, 21]. More common is the infections of the aortic valve spreading and infecting the aortic sinuses and the left ventricular outflow tract, resulting in extensive root aneurysms and sometimes intra-cardiac communication.

Bacteriology

The microbial spectrum is wider than expected. The type of infection depends on multiple factors such as location, patient’s immune status, aetiology and presence of foreign material like grafts. Blood cultures are positive in 50–80% of cases and the positivity rate goes up on cultures of infected aortic/graft tissues [22].

Streptococcus, which used to be a major cause, today accounts for less than 10%. Staphylococcus sp. is the commonest organism today, ranging from 28 to 71% of all aortic infections; more so in the presence of prosthetic stent-graft reinforcing that skin contamination is a major source of infection [24]. MSSA (methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus) and MRSA (methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus) are more commonly associated with early graft infections, whereas CoNS (coagulase-negative Staphylococcus) is associated with late graft infections (Fig. 2) [22]. Infected aneurysms are also reported to be associated with vancomycin-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus (VISA) [24, 25].

Fig. 2.

Donut chart depicting the relative frequency of the pathogens causing the aortic graft infections (adapted from [22])

Salmonella sp. is associated with primary microbial arteritis as they can erode the intima. They are the most common aortic infections in east Asian population [26]. Gram-negative infections are uncommon, but lethal as they have a high chance of rupture and mortality (85%) [8]. Pseudomonas has an inherent ability to cause vascular necrosis by releasing enzymes like elastases and proteases. A polymicrobial cause should be suspected when a gram-negative organism is identified.

Other rare causative organisms include Clostridia, commonly Clostridium septicum, due to contiguous spread from the bowel affected with malignancy. Fungi such as Candida and Aspergillus have been reported in immunocompromised patients, but are rare. Mycobacterium tuberculosis is a very rare cause and few cases have been reported [27–29]. They are usually related to para-aortic nodes and cold abscess. An interesting association is with the Bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG) vaccine, used to treat bladder carcinoma, causing remote infections in the infrarenal aorta [30, 31]. Treponema pallidum once accounted for 50% of the aortic aneurysms [4]. Although syphilis is less frequently seen today, the emergence of multi-drug resistant strains may pose a significant problem in the future. There is a geographical distribution of the causative organisms, with more gram-positive agents in the west as compared to gram-negative in Asian countries, with some reports quoting up to 80% incidence of Salmonella sp. [26]. Rare infections are difficult to treat and have a high degree of rupture and death.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis involves an interplay of: (i) clinical features, (ii) laboratory investigations and (iii) imaging studies (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Venn diagram showing the triad of clinical features, laboratory investigations and imaging (ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; CRP, C-reactive protein; CT, computed tomography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; WBC, white blood cell; FDG-PET, fluoro-deoxy-glucose-positron emission tomography)

Clinical features

The clinical features of aortic infections depend on (a) location, (b) causative micro-organism and (c) duration. Many times, it may be non-specific and needs a high index of suspicion. Similar to any infective process, patients may present with constitutional symptoms, septic shock, a sudden increase in pain, pyrexia of unknown origin (PUO) or sudden collapse due to rupture. Although the disease process, such as an aortic aneurysm, may be asymptomatic, the majority with an ongoing infection will have symptoms. Oderich et al. followed up 43 such patients, out of which 93% were symptomatic and ~ 50% of these had ruptured [6]. Some patients may present with prolonged indolent systemic symptoms based on the virulence of the organism. Rupture of the aorta into a cavity is usually catastrophic. Infected aneurysms can also breach into the gut, depending on the site (aorto-enteric fistula (AEF) or aorto-oesophageal fistula) manifesting as gastro-intestinal bleed. They can also leak into the airways such as the bronchus (aorto-bronchial fistula (ABF)), presenting as haemoptysis. All the above clinical scenarios can be dramatic and if not treated immediately are usually fatal. Aneurysms of inflammatory aetiology should be differentiated from the infected ones based on investigations, as they are clinically indistinguishable.

Prosthetic graft and stent graft infection (SGI)

Aortic graft infection has been divided as “early” (within 4 months of intervention) and “late” (after 4 months) [23]. Early infections are hypothesised to be caused by direct inoculation of an organism (most commonly Staphylococcus aureus) during the surgery/endovascular intervention, whereas late infections usually result due to low virulence of the infective organisms (Streptococcus sp., Staphylococcus epidermidis, Candida sp., etc) and have a gradual subtle course [5, 22, 23, 32]. A majority of the aortic graft infections occur late with an average presentation at 40 months after implantation [23].

Li et al. in their meta-analysis of 402 patients with infections of the aorta, grouped their patients based on one of the three manifestations: (a) chronic low-grade sepsis, (b) severe sepsis and (c) gastrointestinal bleed [3]. Patients with graft infection of the thoracic aorta manifest with subcutaneous and sternal infection, recurring pericardial effusion and/or haemoptysis [32]. Abdominal aortic graft patients may present with vague abdominal symptoms, “unexplained sepsis” and ileus [23]. Gastrointestinal bleeding in the form of haematemesis, melaena or haematochezia in a patient with an aortic graft is considered to be a graft infection manifesting as AEF, unless ruled out. Although the incidence is low, if a gram-negative organism is seen on blood cultures, then an AEF should be suspected [22, 33]. Some of the complications of aortic graft infections include organ ischaemia, disruption of anastomotic suture line and abscess formation [22].

Post-inflammatory syndrome (PIS), which takes place in 30% of patients undergoing EVAR, should be kept in mind when treating a suspected case of SGI [34].

Laboratory investigations

Abnormal blood parameters can confirm the suspicion of infections of the aorta, aortic grafts and stents. These include raised leukocyte counts and other acute-phase reactants such as erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein (CRP) and procalcitonin. In the case of inflammatory aneurysms of the aorta, serial antinuclear antibody (ANA) and IgG4 titres are raised, helping us differentiate it from an infective aetiology [35].

Isolating the causative organism is crucial to treatment and outcome. Positive blood cultures in the presence of an aortic aneurysm (50–70% cases) is diagnostic of infective aetiology [36]. Cultures of excised arterial wall and explanted prosthesis maximize the chances of isolating the causative microorganism and should be the mainstay for guiding the antibiotic therapy [9]. A negative culture does not rule out an infection [36]. Organisms that are not cultivable in the laboratory pose additional diagnostic and treatment challenges.

Imaging

Ultrasound is usually the primary radiological investigation performed for abdominal aortic aneurysms. However, its overall effectiveness is limited due to location, bowel gas and poor delineation of anatomy concerning the aorta. Duplex Doppler helps to differentiate peri-graft fluid from anastomotic pseudoaneurysm and haematoma [23].

Computed tomography aortogram/angiography (CTA) is the investigation of choice for diseases involving the native aorta or graft with a 94% sensitivity and ~ 85% specificity [36, 37]. CTA findings in case of an aortic infection are regional lymph node enlargement, aortic rupture, mycotic aneurysm, pseudo-aneurysm, penetrating ulcer, impending rupture, intramural haematoma, aorto-enteric fistula (as evidenced by contrast leaking into the bowel during the arterial phase and pocket of air in the aneurysm), etc. Mycotic aneurysms are usually saccular and multi-lobulated. CTA also shows signs of graft infection such as (a) peri-graft air and/or fluid/abscess collection, (b) peri-graft soft tissue attenuation and (c) anastomotic aneurysm (Fig. 4a–c) [3, 32, 36]. Peri-graft fluid collection in the immediate postoperative period, after an endovascular procedure, is usually a normal finding and should be considered abnormal only if it occurs beyond 3 months of a procedure or increases over time. Vertebral osteomyelitis and spondylodiscitis are other manifestations of an infected stent graft, which shows up on CT as loss of vertebral height, end-plate with/without anterior vertebral body erosion and paravertebral abscesses [15, 23]. Another use of CT scan in conservative management of aortic infections can be CT-guided aspiration of peri-graft fluid to guide antimicrobial therapy. CT imaging also helps us in differentiating from inflammatory pathologies of the aorta wherein a “mantle sign” is demonstrated by a “thickened wall of the aortic aneurysm with periaortic inflammation and fibrosis” [24, 38].

Fig. 4.

a 3D reconstruction of a CT angiography which depicts a mycotic pseudoaneurysm (green arrow) in a patient 1 year after TEVAR for an infrarenal aortic aneurysm. b, c Contrast CT angiography images showing peri-graft air (red arrow) which is suggestive of an aortic infection ± aorto-enteric fistula (3D, 3-dimensional; CT, computed tomography; TEVAR, thoracic endo-vascular aortic repair)

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with gadolinium contrast is another useful imaging modality for infections of the aorta, though not frequently used. The advantage of MRI over a CTA is its ability to pick up even a small amount of periaortic/peri-graft fluid collection and that it can be used when contrast is contraindicated [36, 39]. MRI shows eccentric collection with low–medium signal intensity on T1-weighted images and high signal intensity on T2-weighted ones in the presence of graft infection [22]. Recent advances in MRI include the adoption of spinal MRI techniques such as 3-dimensional–multispectral imaging (3D-MSI) and other image acquisition techniques like Slice Encoding for Metal Artefact Correction (SEMAC), which reduces the artefacts due to the nitinol exo-skeleton of the stent grafts; however, studies for proving their advantage are yet to be reported [15].

White blood cell (WBC)/leukocyte nuclear scan is a diagnostic modality that complements CTA in post-procedure graft infections. The radionuclides used are gallium 67 citrate, indium 111 and technetium 99m. Indium-111 labelled WBC scan has a positive predictive value (PPV) of 80–90%. It helps demonstrate an unusual collection of leukocytes surrounding the graft. In the early postoperative period, it may show a false-positive result due to nuclear tracer uptake by the healing and inflamed tissue surrounding the graft. Its disadvantage is that it does not demonstrate anatomic details. The co-relation of CTA and WBC scan facilitates better diagnosis [22].

18-Fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography (FDG-PET): Combining 18-FDG-PET with CTA findings is the gold standard for prosthetic graft and stent graft infections with a PPV of ~ 97% and nearly equal negative predictive value [22, 40]. The problem of FDG-PET alone is the risk of a false-positive result, as it shows the inflammatory process.

In 2016, a consensus of experts for Management of Aortic Graft Infection Collaboration (MAGIC) published a formal “case definition” for the diagnosis of aortic graft infections (Fig. 5) [41].

Fig. 5.

Management of Aortic Graft Infection Collaboration (MAGIC) criteria for the diagnosis of Aortic Graft Infections (adapted from [41]) (AEF, aorto-enteric fistula; ABF, aorto-bronchial fistula; CTA, CT angiography; AGI, aortic graft infections; C, centigrade; FDG-PET, fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography; WBC, white blood cell; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; CRP, C-reactive protein)

Treatment

The management of infected aneurysms largely depends on the anatomic site, presentation, presence of systemic signs of sepsis and the causative organism. A proper early diagnosis with microbiology and imaging will help in planning the strategy and affect the outcome. The risk of rupture is not related to size in an infected aneurysm, and hence even a small aneurysm should be treated as a potentially life-threatening entity. Treatment strategies also vary depending on whether the infection involves the native aorta, prosthetic graft or an endo-stent. However, the principles of management are common and the definitive treatment is essentially surgical (Fig. 6).

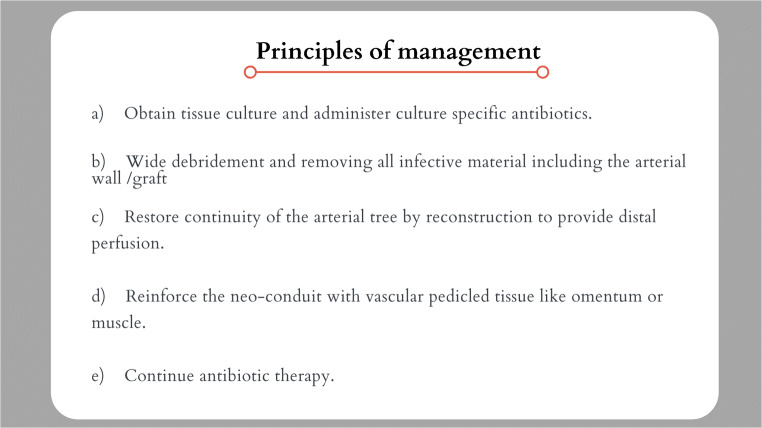

Fig. 6.

The principles of management of aortic infections

Preoperative antibiotic therapy

Antibiotics should be started as soon as a diagnosis is made pending cultures. There is no clear evidence to suggest an optimal duration. Many times the clinical status will warrant early surgery and waiting is not an option. However, in case the patient is stable, a few days of antibiotic therapy would be helpful. Hsu et al. reported a better outcome for patients with a longer duration of antibiotics before surgery [26, 42]. Kan et al. also reported better outcomes with at least a week of pre-procedure antibiotics in EVAR cases [43]. The answer probably is to balance the risk of waiting versus the risk of infection in the neo-conduit. A week of antibiotics before surgical intervention is probably beneficial, if the clinical situation permits.

Surgical treatment

Surgery forms the cornerstone of treatment. Proper planning and execution are very important for a good outcome.

Aims

Proper proximal and distal control have to be secured in an area relatively free from active infection, as the quality of tissue and extent of involvement of the vessel are difficult to judge.

Intraoperative cultures are mandatory. A gram stain during the procedure will help plan a graft substitute. However, a negative stain does not rule out an infection.

The key to prevent reinfection or persistence of infection is to perform an extensive debridement, as much as possible, and to remove all necrotic infected tissues adjacent to the aorta, including the arterial wall or graft as dictated.

Reconstruction can be performed at the same site with an in situ or an extra-anatomic graft to avoid the chances of neo-graft infection. Reconstruction largely depends on the anatomical site.

The substitutes available are antibiotic coated or soaked synthetic grafts, cryopreserved allografts and xeno-pericardial tube grafts, depending on the location and the micro-organism causing the infection.

Reinforcing with a vascularized pedicle (omentum or muscle) to promote neovascularity and for better antibiotic reach and healing.

Adjuncts like local irrigation, staged closure and antibiotic beads.

Aortic root/ascending aorta and arch

Ascending aorta is usually associated with infections involving the aortic root, aortic valve and aorto-ventricular junction. The principle of treatment remains the same, i.e. excision of all infected material, replacement of which may involve the root and the arch to a variable extent. Aneurysms involving the arch will need adequate cerebral protection strategy, as the procedure may be longer than anticipated. The choice of substitutes depends on the extent of infection and the clinical status of the patient. A standard Dacron conduit, or a bio-conduit, can be chosen, if the infection involves a limited portion of the root. In an active infection of ascending aorta or arch, a biological tissue conduit is preferred as a replacement.

Homografts are the conduit of choice in florid infection involving the root [19, 44]. Homografts have been associated with late calcification, anastomotic aneurysms and graft disintegrations. Despite these disadvantages, they are one of the best substitutes in acute active infective fields. Carrel et al., in a review of 103 implants, of which 78 were for infected prostheses, found operative mortality of 9% in an infected prosthesis, 30% in AEF and 0% in clean cases. The 5-year survival was > 50% in infected cases [45]. Khaladj et al. in their small series showed reasonable results with the use of homografts as a substitute in reoperations for infected ascending aortic grafts [46]. Long-term results have been sub-optimum. Freestyle porcine root has been used as a substitute for root and aortic-ventricular disruption and root abscesses. The disadvantage being that the length is short, which may need an extension with a synthetic or a pericardial tube. Carrel et al. have proposed the use of xeno-pericardial tubes created on the table with or without a valve, with very good results [47]. Graft infections in this area are lethal and the reoperations very complex. No clear guidelines are available and management is on a case-to-case basis following the broad principles.

Schafers et al. looked at their 20-year data on outcomes of reoperations of the root. In 50% of the patients, the indication was an infection. Hospital mortality was only 10%. They found that patients operated on for endocarditis had a very poor survival at 10 years and the attrition continued beyond the first 2–3 years, which could not be explained. The authors suggested that there could be a continuing negative impact of endocarditis due to some unidentified factors. At 15 years, survival was significantly worse for active endocarditis, with active infection being a major pre-operative predictor of poor outcome [48]. This observation makes an argument for using more biological conduits in this clinical situation, as degeneration may not be an issue. At the same time, it also raises the need to look at extended medical management. Reoperations should be supported with adjuncts like vascularized tissue cover (thymus/omentum), thorough antibiotic irrigation and prolonged antibiotics [49].

Thoracic aorta

Infections of the thoracic aorta are associated with high mortality, close to 50%. Staphylococcus sp. remains the most common causative agent and the rupture of the aorta is very common. Rupture or erosion into the airway or oesophagus is catastrophic and needs emergency salvage. Oderich et al. reported that the distribution of involvement of the descending aorta and thoracic/thoraco-abdominal aorta was nearly a third [6].

The surgical approach is determined by the location—most commonly a left thoracotomy or a thoraco-abdominal approach, depending on the extent. Sometimes a median sternotomy, left heart bypass and cerebrospinal fluid drainage may be needed. The basic principles are the same with wide excision and debridement, followed most commonly by an in situ graft reconstruction using an antibiotic-coated Dacron graft or a cryopreserved allograft, if available. Kieffer et al. described a technique called exclusion bypass where an ascending aorta to infra-renal/iliac reconstruction is done through the diaphragm and tunnelling the graft retro-peritoneally [50]. The distal arch and supra-coeliac aorta are then closed excluding it. That area is debrided and irrigated. Endovascular repairs have also been done recently, with extended antibiotic therapy, with a view to reducing the morbidity of surgery. Fistulation and rupture carry 85% mortality and may need a staged approach, with endovascular as a bridge, and a second stage to debride and perform a definitive repair.

Abdominal aorta

The infrarenal aorta is the most commonly affected. Abdominal infected aneurysms carry a mortality of 15–38%, a little less than the thoracic counterpart. The segment of the aorta adjacent to the renal and visceral vessels offers a special challenge. Infections without pre-existing aneurysm tend to occur in the posterior wall of the supra-coeliac aorta. In situ reconstruction is the preferred technique in the suprarenal segments. The substitute choices are cryopreserved allografts and antibiotic-coated Dacron grafts. Bisdas et al., in a study involving 110 patients operated on for mixed clinical spectrum of infected abdominal aorta, showed a 3-year survival of 81% and freedom from re-operation of 89% using cryopreserved homograft as a substitute [51]. Special to this situation is an option using the femoral and popliteal veins, called the neo-aortoiliac system (NAIS) and described by Clagett [52]. An extra-anatomic bypass is an option, with debridement of the primary site and closure of the aorta. Covering the neo-conduit with a vascularized tissue like omentum or muscle is universal. As the area involved is retro-peritoneal, the omentum offers a very simple and effective solution.

Reconstruction

In situ

In situ reconstruction means the removal of the infected vessel or graft and replacing with a neo-conduit in the same anatomical location. The other principles discussed remain the same. The substitutes available for in situ reconstruction are:

Antibiotic-treated Dacron grafts

Antibiotic treatment of the grafts was initiated, as the in situ grafts had a reinfection rate of ~ 20%. Rifampin is the preferred drug for treating the grafts because it is effective against both gram-positive and gram-negative organisms. Silver impregnation has also been tried. Some series reported a reduction in infection rates. Oderich et al. from Mayo Clinic reported a 0% of late graft reinfection in rifampin-soaked grafts [6]. They also reported its use in graft-enteric fistulae with low infection rates and 5-year survival of close to 60% and 10-year of 40%, with no late graft-related deaths [53]. Bandyk et al. showed high infection rates in MRSA and doubted its usefulness in high virulence strains [54].

Cryo-preserved allografts

Allografts are sourced from cadaveric donors and cryopreserved. They are limited in terms of availability and cost. They offer excellent results in terms of reinfection rates. Freedom from explant is 99% at 1 year and 88% at 5 years [55]. Peri-anastomotic haemorrhage and pseudoaneurysm are problems seen with allograft reconstruction. Haemorrhage is also an issue when used in the setting of a enteric fistula. Calcification is another major problem. Brown et al. reported a very low incidence of graft-related morbidity—11.8% in allograft related as compared to 50% in the case of the prosthetic graft [56].

Xeno-pericardial tube grafts

These offer a solution as a substitute in any part of the aorta, from root to the abdominal aorta. The xeno-pericardial patch is sewn over a chosen size of Hegar bougie and a tube is created [32, 45]. Commercially available bovine pericardial patches are used to make them on the table (Fig. 7). Even though the 30-day mortality was 30%, there was no graft-related reinfection or reintervention. Carrel et al. claim excellent results and mention that they have almost completely transitioned to using this as a substitute [45]. The advantage is that these can be used in any anatomical location and they also mention creating a bio-root with this by adding a bioprosthetic valve. These are hand sewn on the table and offer great flexibility and are also cost-effective. The size match is excellent as it is a custom fit. Kreibich et al. from Freiburg have also shown promising results with a 30-day mortality of 20% and 100% freedom from proven aortic reinfection at 18 months [57]. The same group presented the updated data on 42 patients at the 34th Annual Meeting (Virtual) of the European Association of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS), 2020 with a 14% 30-day mortality.

Fig. 7.

Intra-operative picture showing the reconstructed infra-renal aorta with a xeno-pericardial tube graft (courtesy of Dr.V.V. Bashi and Dr. A. Mohammed Idhrees)

Extra-anatomic bypass

The idea behind extra-anatomical bypass is to use the new conduit in a virgin territory so that the chances of reinfection are very less. Treating the primary site with extensive debridement and toileting is subsequently performed. The commonest extra-anatomic bypass is the axillo-femoral bypass used for infra-renal aneurysms. The aortic stump needs to be closed and reinforced with the omentum as stump blowouts are catastrophic, difficult to control and often fatal. Late aortic stump disruption is reported in ~ 15% of cases [58]. The advantage is that it can be staged with the bypasses done initially. The technique, even though it appears simple, is more morbid as the primary area still needs to be addressed. The infection rates reported are also in the order of up to 20%. This is probably useful when in situ reconstruction is not possible. Nevertheless, the utility of this technique is very limited in aortic infection, except for infra-renal aorta.

Endovascular repair

Endovascular grafting seems to be against the principles of surgery in an infected environment. However, at times, the location and anatomy may render surgery to be extremely challenging. Endovascular options seem to fill in this gap and are being increasingly used. The disadvantage is that locus of sepsis is not eradicated, and hence control of infection may be difficult. There have been reports of EVAR supported with local debridement and irrigation. The role is not very clearly defined, but may be useful as a salvage in case of an impending rupture, as a bridge to definitive repair. There are reports of infected aneurysm treated with EVAR alone and 2-year results comparable to open repair and in situ grafting [59].

Sedivy et al. reported a series of 32 such cases, which is probably the largest series [60]. Many of the series are small and centre-specific. To answer this question, the European multicentre collaboration retrospectively analysed results from 16 centres over 14 years. In this, 123 patients were followed up for 10 years and found a 1-year survival of 75%, 5-year survival of 55% and 10 years 41%. Mean antibiotic therapy was for 30 weeks. Early outcomes were excellent with a 30-day survival of 91%. Graft-related death was 19%, mostly occurring in the first year itself. They found a non-Salmonella sp. associated with poor long-term outcomes [61]. Many open repair series showed worse outcomes, with 30-day mortality close to 20–40%. Data on long-term follow-up is scarce.

Graft infection

The principles of management are similar to a native infection. The range of therapeutic options include (a) graft excision with extra-anatomic bypass, which can be staged or simultaneous; (b) graft excision with in situ bypass; (c) graft preservation with local therapy (Fig. 8). The choice depends on the clinical status. A meta-analysis involving 402 patients of SGI showed that surgical management fairs the best (out of which, 90% underwent surgical repair and 10% were managed conservatively). Patients with an AEF had the worst outcomes [3].

Fig. 8.

Options for aortic graft infections with respective pros and cons (adapted from [22])

Graft conservation

The idea of retaining an infected prosthesis may be an option in very select situations, such as single gram-positive organisms, limited peri-graft involvement, early infection and the absence of sepsis. This however will involve debridement, irrigation with an antiseptic solution, antibiotic beads cover and muscle/omental flap cover to gain local control (Fig. 9a, b). This method may find a place for endograft infections and there are some reports of a successful outcome. A recent study, published in 2016, showed reasonable results with this modality, provided the condition is picked up very early, i.e. less than 30 days [62]. However, the presence of erosion or fistulation to airway or enteric tracts, which 30% of endograft infections present with, is a contraindication. Goto and his group from Osaka presented at the 34th EACTS, 2020, the role of FDG-PET-guided management and made a recommendation that a standard uptake value(max) < 0.68 may be a consideration of antibiotic therapy alone.

Fig. 9.

a, b Intra-operative image of an extensive infection involving the ascending aorta prosthetic graft which was managed with graft conservation and omentopexy (courtesy of Dr. V.V. Bashi and Dr. A. Mohammed Idhrees)

Aorto-enteric and aorto-bronchial fistulae

Fistulation of infected aneurysms or grafts is a challenging scenario with very high mortality. Expeditious treatment is the need in such cases. The classical treatment is debridement, excision of the aneurysm or graft, reconstruction of the bowel (in AEF) or the airway (in ABF), reconstruction of the aorta, reinforcement with a vascularized pedicle and use of other adjuncts [63]. Despite this, operative mortality ranges from 30 to 60%. The most important factor is the meticulous repair of the gut, rather than the aorta.

Endovascular stenting has been more frequently used now in this situation to tide over the crisis and stage the definitive repair. It has also been used as a primary form of treatment, in addition to antibiotics, but with very poor outcomes. However, it is a good tool as a bridge to definite treatment.

Additional strategies

Local measures

A range of measures have been tried to reduce recurrence. Coselli et al. have used vancomycin and cephalosporin powder on the grafts [19]. A staged closure has been done with sponges soaked in 10% povidone-iodine for 48 h followed by reinforcement with a vascularized pedicle and closure. Post-procedure irrigation with 1% povidone-iodine for a few days has been done, while monitoring the iodine levels and hepatic enzymes to prevent iodine toxicity. This method has also been attempted now for EVAR graft conservation by image-guided catheters placed and then irrigation performed [64]. Gentamycin-impregnated fibrin glue has been used to seal dead spaces. Rifampin-soaked grafts have been discussed earlier. It is also prudent on the part of the surgeon not to use any foreign material, such as Teflon felt for reinforcing suture lines.

Vascularized pedicle

Local control of infection at the site is very important to prevent sepsis and re-infection. After debridement and reconstruction, coverage of the graft with vascularized pedicle has proven to decrease infections and improve outcomes. The most common vascularized pedicle is the omentum, which is based on the right gastroepiploic artery. It is easily accessible for abdominal and thoraco-abdominal aortic infections and can also be brought through the diaphragm to reach the ascending aorta. The omentum, “policeman of the abdomen”, has the innate ability to promote healing by increased oxygen delivery, enhancing immune response, scavenging the secretions, better antibiotic penetration and ability to fill the dead space. The value of this, more so in the setting of an airway or an enteric communication, is unparalleled. Interposing with the omentum aids sealing and rapid healing [65].

Yamashiro reported a significant drop in 30-day mortality (12.5% vs 50%) and improved survival at 5 years with omental wrap (84.6% vs 33.3%) [66]. The omentum can also be used to cover the aortic stump in case of an extra-anatomic bypass to prevent blowouts. When the omentum is not available, local coverage like the thymus or muscle flaps can also be used, e.g. the pectoralis, serratus anterior, latissimus dorsi, rectus abdominis and intercostal muscles [65].

Postoperative antibiotics

There is no clear consensus on the duration of postoperative antibiotic therapy. The general rule has been to give parenteral antibiotics for 6 weeks followed by long-term oral therapy. This has to be longer when a graft conservation approach has been adopted, especially in a patient with EVAR. Similar to patients with a prosthetic valve, a strategy of antibiotic prophylaxis during any intervention to prevent seeding may be an appropriate practice on a long-term basis. As a majority of the re-infections are seen in the first 6 months, and rarely after 1 year, the European multicentre study suggests oral antibiotic therapy for at least a year, especially in the settings of an EVAR [61].

Management algorithm

A combination of clinical features, laboratory investigations, microbial cultures and imaging helps establish a diagnosis. A high degree of clinical suspicion is paramount, especially in the setting of graft infections. Surgical treatment is almost always needed in some form. The management involves a multi-pronged approach and we propose this simple algorithm (Fig. 10).

Fig. 10.

Management algorithm—aortic infections

Conclusion

Infections of the aorta are a clinical challenge and continue to carry a high mortality. The most common cause currently is secondary to vascular interventions with Staphylococcus sp. being the commonest causative organism.

Antibiotics are probably best when given for a week prior to the surgery, if the clinical situation permits. The surgical process involves good exposure, thorough debridement of all infected material including the aorta or the graft and reconstruction with an appropriate substitute, preferably biological. In situ reconstruction is the preferred form in the aorta. However, extra-anatomic bypass may have to be done sometimes, with exclusion, but not with improved outcomes. The most important aspect is the use of a vascularized pedicle like the omentum to cover the neo-graft. Postoperatively, 6 weeks of antibiotics is universally agreed as a minimum requirement. Endovascular stent grafts have been used, especially with aortic fistulation, and have a role as a bridge to a more definitive procedure. In addition to a high 30-day mortality, reinfections and late mortality continue to persist despite all the advancements.

The most important goal eventually is to eradicate the infection and to prevent its persistence or recurrence. An integrated treatment strategy from early diagnosis, identification of the organism, administering specific antibiotics, reconstruction with a bio-conduit, covering the reconstructed area with vascularized pedicle, irrigation and complete course of post operative antibiotics are crucial for a favourable outcome.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Dr. V.V. Bashi and Dr. A. Mohammed Idhrees at the Institute of Cardiac & Advanced Aortic Diseases, Chennai, India, for sharing the intra-operative photographs.

Funding

None.

Declarations

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Osler W. The gulstonian lectures, on malignant endocarditis. Br Med J. 1885;1:467–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Sommerville RL, Allen EV, Edwards JE. Bland and infected arteriosclerotic abdominal aortic aneurysms: a clinicopathologic study. Medicine (Baltimore). 1959;38:207–21. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Li HL, Chan YC, Cheng SW. Current evidence on management of aortic stent-graft infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Vasc Surg. 2018;51:306–13. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Manzur MF, Han SM. FAW. Infected arterial aneurysms. In: Sidawy NA, Perler AB, editors. Rutherford’s Vasc Surg Endovasc Ther. 9th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2019. p. 588–602.

- 5.Wilson WR, Bower TC, Creager MA, et al. Vascular graft infections, mycotic aneurysms, and endovascular infections: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016;134:e412–60. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Oderich GS, Panneton JM, Bower TC, et al. Infected aortic aneurysms: aggressive presentation, complicated early outcome, but durable results. J Vasc Surg. 2001;34:900–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Dean RH, Waterhouse G, Meacham PW, Weaver FA, O’Neil JA. Mycotic embolism and embolomycotic aneurysms. Neglected lessons of the past. Ann Surg. 1986;204:300–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Jarrett F, Darling RC, Mundth ED, Austen WG. Experience with infected aneurysms of the abdominal aorta. Arch Surg. 1975;110:1281–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Müller BT, Wegener OR, Grabitz K, Pillny M, Thomas L, Sandmann W. Mycotic aneurysms of the thoracic and abdominal aorta and iliac arteries: Experience with anatomic and extra-anatomic repair in 33 cases. J Vasc Surg. 2001;33:106–13. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Marques da Silva R, Caugant DA, Eribe ERK, et al. Bacterial diversity in aortic aneurysms determined by 16S ribosomal RNA gene analysis. J Vasc Surg. 2006;44:1055–60. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Johnston KW. Multicenter prospective study of nonruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm. Part II. Variables predicting morbidity and mortality. J Vasc Surg. 1989;9:437–47. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Berger P, Vaartjes I, Moll FL, De Borst GJ, Blankensteijn JD, Bots ML. Cumulative incidence of graft infection after primary prosthetic aortic reconstruction in the endovascular era. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2015;49:581–5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Coselli JS, Spiliotopoulos K, Preventza O, de la Cruz KI, Amarasekara H, Green SY. Open aortic surgery after thoracic endovascular aortic repair. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2016;64:441–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Chalmers N, Eadington DW, Gandanhamo D, Gillespie IN, Ruckley CV. Case report: infected false aneurysm at the site of an iliac stent. Br J Radiol. 1993;66:946–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Mandegaran R, Tang CSW, Pereira EAC, Zavareh A. Spondylodiscitis following endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair: imaging perspectives from a single centre’s experience. Skeletal Radiol. 2018;47:1357–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Smeds MR, Duncan AA, Harlander-Locke MP, et al. Treatment and outcomes of aortic endograft infection. J Vasc Surg. 2016;63:332–40. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Cernohorsky P, Reijnen MMPJ, Tielliu IFJ, van Sterkenburg SMM, van den Dungen JJAM, Zeebregts CJ. The relevance of aortic endograft prosthetic infection. J Vasc Surg. 2011;54:327–33. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Vogel TR, Symons R, Flum DR. The incidence and factors associated with graft infection after aortic aneurysm repair. J Vasc Surg. 2008;47:264–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.LeMaire SA, Coselli JS. Options for managing infected ascending aortic grafts. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2007;134:839–43. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Faccenna F, Alunno A, Castiglione A, Carnevalini M, Venosi S, Gossetti B. Large aortic pseudoaneurysm and subsequent spondylodiscitis as a complication of endovascular treatment of iliac arteries. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2013;61:606–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.von der Höh NH, Pieroh P, Henkelmann J, et al. Spondylodiscitis due to transmitted mycotic aortic aneurysm or infected grafts after endovascular aortic aneurysm repair (EVAR): a retrospective single-centre experience with short-term outcomes. Eur Spine J. 2020. 10.1007/s00586-020-06586-2. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Antonello RM, D’Oria M, Cavallaro M, et al. Management of abdominal aortic prosthetic graft and endograft infections. A multidisciplinary update. J Infect Chemother. 2019;25:669–80. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Back RM. Graft infections. In: Sidawy NA, Perler AB, editors. Rutherford’s Vasc Surg Endovasc Ther. 9th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2019. p. 588–602.

- 24.Lin T-W, Kan C-D. Infected aortic aneurysms. In: Kirali K, editor. Aortic aneuryms. Rijeka, Croatia: InTech; 2017. p. 143–69.

- 25.Kuo CC, Wu V, Tsai CW, Chou NK, Wang SS, Hsueh PR. Fatal bacteremic mycotic aneurysm complicated by acute renal failure caused by daptomycin-nonsusceptible, vancomycin-intermediate, and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47:859–60. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Hsu RB, Tsay YG, Wang SS, Chu SH. Surgical treatment for primary infected aneurysm of the descending thoracic aorta, abdominal aorta, and iliac arteries. J Vasc Surg. 2002;36:746–50. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Choudhary SK, Bhan A, Talwar S, Goyal M, Sharma S, Venugopal P. Tubercular pseudoaneurysms of aorta. Ann Thorac Surg. 2001;72:1239–44. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Canaud L, Marzelle J, Bassinet L, Carrié AS, Desgranges P, Becquemin JP. Tuberculous aneurysms of the abdominal aorta. J Vasc Surg. 2008;48:1012–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Long R, Guzman R, Greenberg H, Safneck J, Hershfield E. Tuberculous mycotic aneurysm of the aorta: review of published medical and surgical experience. Chest. 1999;115:522–31. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Seelig MH, Oldenburg WA, Klingler PJ, Blute ML, Pairolero PC. Mycotic vascular infections of large arteries with Mycobacterium bovis after intravesical bacillus Calmette-Guerin therapy: case report. J Vasc Surg. 1999;29:377–81. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Harding GEJ, Lawlor DK. Ruptured mycotic abdominal aortic aneurysm secondary to Mycobacterium bovis after intravesical treatment with bacillus Calmette-Guérin. J Vasc Surg. 2007;46:131–4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Carrel T, Schmidli J. Management of vascular graft and endoprosthetic infection of the thoracic and thoraco-abdominal aorta. Multimed Man Cardiothorac Surg. 2011. 10.1510/mmcts.2010.004705. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Claeys KC, Heil EL, Pogue JM, Lephart PR, Johnson JK. The Verigene dilemma: gram-negative polymicrobial bloodstream infections and clinical decision making. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2018;91:144–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Arnaoutoglou E, Kouvelos G, Papa N, et al. Prospective evaluation of post-implantation inflammatory response after EVAR for AAA: Influence on patients’ 30 day outcome. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2015;49:175–83. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Ishizaka N, Sohmiya K, Miyamura M, et al. Infected aortic aneurysm and inflammatory aortic aneurysm-in search of an optimal differential diagnosis. J Cardiol. 2012;59:123–31. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Kim Y-W. Infected aneurysm: current management. Ann Vasc Dis.2010;3:7–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Khaja MS, Sildiroglu O, Hagspiel K, Rehm PK, Cherry KJ, Turba UC. Prosthetic vascular graft infection imaging. Clin Imaging. 2013;37:239–44. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Pennell RC, Hollier LH, Lie JT, et al. Inflammatory abdominal aortic aneurysms: a thirty-year review. J Vasc Surg. 1985;2:859–69. [PubMed]

- 39.Walsh DW, Ho VB, Haggerty MF. Mycotic aneurysm of the aorta: MRI and MRA features. J Magn Reson Imaging. 1997;7:312–5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Fukuchi K, Ishida Y, Higashi M, et al. Detection of aortic graft infection by fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography: comparison with computed tomographic findings. J Vasc Surg. 2005;42:919–25. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Lyons OTA, Baguneid M, Barwick TD, et al. Diagnosis of aortic graft infection: a case definition by the management of Aortic Graft Infection Collaboration (MAGIC). Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2016;52:758–63. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Lin CH, Hsu RB. Primary infected aortic aneurysm: clinical presentation, pathogen, and outcome. Acta Cardiol Sin. 2014;30:514–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Kan CD, Lee HL, Yang YJ. Outcome after endovascular stent graft treatment for mycotic aortic aneurysm: a systematic review. J Vasc Surg. 2007;46:906–12. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Vogt PR, Brunner-La Rocca HP, Carrel T, et al. Cryopreserved arterial allografts in the treatment of major vascular infection: a comparison with conventional surgical techniques. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1998;116:965–72. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 45.Carrel T, Englberger L, Schmidli J. How to treat aortic graft infection? With a special emphasis on xeno-pericardial aortic tube grafts. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2019;67:44–52. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 46.Khaladj N, Pichlmaier U, Stachmann A, et al. Cryopreserved human allografts (homografts) for the management of graft infections in the ascending aortic position extending to the arch. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2013;43:1170–5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 47.Carrel TP, Schoenhoff FS, Schmidli J, Stalder M, Eckstein FS, Englberger L. Deleterious outcome of No-React-treated stentless valved conduits after aortic root replacement: Why were Warnings ignored? J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2008;136:52–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 48.Heubner L, Schneider U, Giebels C, Karliova I, Raddatz A, Schäfers HJ. Early and long-term outcomes for patients undergoing reoperative aortic root replacement. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2019;55:232–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 49.Guenther SPW, Reichelt A, Peterss S, et al. Root replacement for graft infection using an all-biologic xenopericardial conduit. J Heart Valve Dis. 2016;25:440–7. [PubMed]

- 50.Kieffer E, Petitjean C, Richard T, Godet G, Dhobb M, Ruotolo C. Exclusion-bypass for aneurysms of the descending thoracic and thoracoabdominal aorta. Ann Vasc Surg. 1986;1:182–95. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 51.Bisdas T, Bredt M, Pichlmaier M, et al. Eight-year experience with cryopreserved arterial homografts for the in situ reconstruction of abdominal aortic infections. J Vasc Surg. 2010;52:323–30. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 52.Clagett GP, Valentine RJ, Hagino RT, et al. Autogenous aortoiliac/femoral reconstruction from superficial femoral-popliteal veins: feasibility and durability. J Vasc Surg. 1997;25:255–66. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 53.Oderich GS, Bower TC, Hofer J, et al. In situ rifampin-soaked grafts with omental coverage and antibiotic suppression are durable with low reinfection rates in patients with aortic graft enteric erosion or fistula. J Vasc Surg. 2011;53:99–106. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 54.Bandyk DF, Novotney ML, Johnson BL, Back MR, Roth SR. Use of rifampin-soaked gelatin-sealed polyester grafts for in situ treatment of primary aortic and vascular prosthetic infections. J Surg Res. 2001;95:44–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 55.Harlander-Locke MP, Harmon LK, Lawrence PF, et al. The use of cryopreserved aortoiliac allograft for aortic reconstruction in the United States. J Vasc Surg. 2014;59:669–74. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 56.Brown KE, Heyer K, Rodriguez H, Eskandari MK, Pearce WH, Morasch MD. Arterial reconstruction with cryopreserved human allografts in the setting of infection: A single-center experience with midterm follow-up. J Vasc Surg. 2009;49:660–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 57.Kreibich M, Siepe M, Morlock J, et al. Surgical treatment of native and prosthetic aortic infection with xenopericardial tube grafts. Ann Thorac Surg. 2018;106:498–504. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 58.Reilly LM, Altman H, Lusby RJ, Kersh RA, Ehrenfeld WK, Stoney RJ. Late results following surgical management of vascular graft infection. J Vasc Surg. 1984;1:36–44. [PubMed]

- 59.Kan CD, Lee HL, Luo CY, Yang YJ. The efficacy of aortic stent grafts in the management of mycotic abdominal aortic aneurysm-institute case management with systemic literature comparison. Ann Vasc Surg. 2010;24:433–40. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 60.Sedivy P, Spacek M, El Samman K, et al. Endovascular treatment of infected aortic aneurysms. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2012;44:385–94. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 61.Sorelius K, Mani K, Bjorck M, et al. Endovascular treatment of mycotic aortic aneurysms a European multicenter study. Circulation. 2014;130:2136–42. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 62.Umminger J, Krueger H, Beckmann E, et al. Management of early graft infections in the ascending aorta and aortic arch: A comparison between graft replacement and graft preservation techniques. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2016;50:660–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 63.Idhrees AM, Jacob A, Velayudhan BV. An aorto - Oesophageal fistula following endograft: sealing of fistulae with omentum and replacement of the aorta. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2018;26:516–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 64.Nakajima N, Masuda M, Ichinose M, Ando M. A new method for the treatment of graft infection in the thoracic aorta: In situ preservation. Ann Thorac Surg. 1999;67:1994–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 65.Coselli JS, Crawford ES, Williams TW, et al. Treatment of postoperative infection of ascending aorta and transverse aortic arch, including use of viable omentum and muscle flaps. Ann Thorac Surg. 1990;50:868–81. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 66.Yamashiro S, Arakaki R, Kise Y, Inafuku H, Kuniyoshi Y. Potential role of omental wrapping to prevent infection after treatment for infectious thoracic aortic aneurysms. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2013;43:1177–82. [DOI] [PubMed]