Abstract

Background:

Research suggests that lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) populations experience higher prevalence of school bullying than heterosexuals.

Objectives:

We examined if (a) verbal versus physical bullying were differentially associated with physical health among sexual minorities and (b) if sexual identity (i.e., homosexual [i.e., lesbian/gay] vs.bisexual) moderated the association of bullying on physical health.

Design:

LGB adults aged 18 to 66 years (n = 463) were recruited online. Participants reported high school experiences of verbal and physical bullying and physician-diagnosed health conditions.

Results:

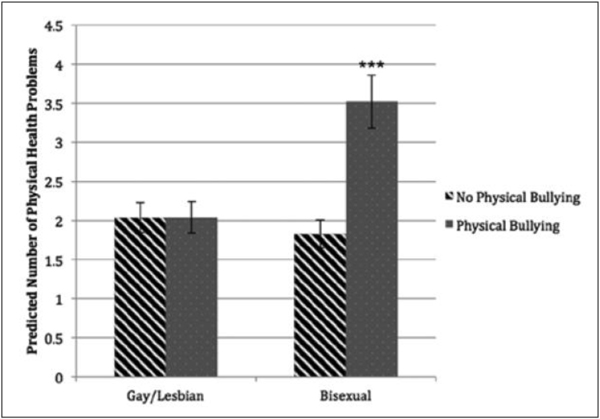

Physical and verbal bullying were related to physical health conditions (ps < .01). Physical bullying had a significant negative impact on physical health for bisexual persons (p < .001) but not for gay/lesbian persons.

Conclusions:

Experiencing bullying in high school was associated with physical health problems in adulthood. Bullying had a different relationship with health problems for bisexually identified individuals compared to lesbian/gay individuals. Future research should strive to disentangle potential differences in the relationship between bullying and health within sexual minority groups.

Keywords: bullying, physical health, bisexuality, lesbian, gay

Introduction

According to the National Crime Victimization Survey (U.S. Department of Justice, 2009), school-based victimization averages at around 29.0% for students in the United States. Bullying has become a major public health concern as researchers and the public recognize the lasting negative impacts that it can have on individuals (Furlong, Morrison, & Greif, 2003). There is a large body of evidence showing that individuals victimized by bullies in adolescence are at risk for mental health conditions and suicidal ideation (see Gini & Pozzoli, 2009, for review). Recent research shows that being a victim of bullying is also related to new-onset physical health problems. For example, Fekkes and colleagues conducted a prospective longitudinal study examining more than 1,000 children (ages 9–11) attending school in the Netherlands (Fekkes, Pijpers, Fredriks, Vogels, & Verloove-Vanhorick, 2006). They found an increased incidence of health problems (e.g., abdominal pain, headaches, tiredness) among children who were bullied when compared to their peers who were not bullied.

Although a nationally representative U.S. sample shows that about one third of adolescents have experienced some form of bullying in school (Nansel et al., 2001), research shows that bullying is even more prevalent among lesbian, gay, and bisexual (i.e., LGB or sexual minority) youth (Berlan, Corliss, Field, Goodman, & Bryn Austin, 2010; Hunt & Jensen, 2006; Kosciw, Greytak, Bartkiewicz, Boesen, & Palmer, 2012). For instance, in analyses of pooled Youth Risk Behavior Survey data from states that gathered information on sexual orientation, Kann et al. (2011) noted that significantly more LGB than heterosexual high school students reported being in a physical fight and missing school because they felt unsafe there. Recent evidence suggests that aspects of victimization such as frequency, duration, and severity increase the risk of negative health outcomes (Wilsnack, Kristjanson, Hughes, & Benson, 2012). Given recent evidence indicating that the prevalence of bullying among the LGB population is significantly higher than the non-LGB population (Berlan et al., 2010; Kann et al., 2011), this group may be at increased risk for health problems across the lifespan.

The majority of the studies about bullying among LGB populations have focused on mental health outcomes (e.g., Arseneault, Bowes, & Shakoor, 2010; Gruber & Fineran, 2008; Kaltiala-Heino, Rimpelä, Rantanen, & Rimpelä, 2000; Mishna, Newman, Daley, & Solomon, 2009; Sourander, Helstela, Helenius, & Piha, 2000). For example, researchers have noted higher depression scores, greater number of posttraumatic stress symptoms, and greater number of suicide attempts among LGB victims of bullying relative to those who did not report being bullied in school (Rivers, 2001a, 2004). Initial research on the impact of bullying victimization on physical health in general population studies provides strong evidence that bullying contributes to increased physical health problems (Fekkes et al., 2006; Gini & Pozzoli, 2009; Gruber & Fineran, 2008; T. Williams, Connolly, Pepler, & Craig, 1996; Wolke, Woods, Bloomfield, & Karstadt, 2001). Fekkes et al. (2006) found that children who were bullied in elementary school reported new cases of psychosomatic and psychosocial problems over time, such as anxiety, depression, feelings of tension or tiredness, bedwetting, sleep problems, gastrointestinal pain, and loss of appetite. Furthermore, being bullied contributes to a greater likelihood of engaging in health-risk behaviors such as smoking and alcohol use among adolescents relative to those who do not report being bullied (Mishna et al., 2009; Vieno, Gini, & Santinello, 2011). Following from the findings of general population studies, it is likely that bullying has the same negative impact on physical health among LGB individuals; however, it is unclear if these effects persist into adulthood. Studies show that many of the harmful effects of bullying, such as difficulty in forming adult relationships, lower self-esteem, and higher depression scores, can persist into adulthood (Carlisle & Rofes, 2007; Matsui, Kakuyama, Tsuzuki, & Onglatco, 1996). However, this has not been explored among LGB individuals specifically. Moreover, there may be specific characteristics of bullying, such as verbal or physical harassment, which may differentially influence long-term health effects. For the present study, we examined the impact of verbal and physical bullying on health among a sample of self-identified LGB individuals. We followed the definition of bullying used by the Gay, Lesbian, & Straight Education Network (Kosciw & Diaz, 2006), whereby verbal bullying was defined as any verbal harassment in high school, and physical bullying was defined as any physical harassment (pushed, tripped, had object thrown at them, etc.) in high school.

It is also important to note that many of the previous studies that have examined the impact of bullying on physical health did not control for potential demographic variables that may also contribute to poorer health. For instance, ethnic minorities are more likely to be bullied in school (Carlyle & Steinman, 2007; Siann, Callaghan, Glissov, Lockhart, & Rawson, 1994) and experience more health disparities then their White peers (D. R. Williams, 1997). Despite these findings, a recent meta-analysis highlighted that many studies examining bullying and health have not included race as a covariate when conducting their analyses (e.g., Gini & Pozzoli, 2009). The present study included a number of covariates, such as age, weight, race, gender, and engagement in health risk behaviors (i.e., drinking, smoking), to examine if there is a direct effect of bullying on physical health.

In a nationally representative sample, researchers discovered that verbal bullying was more common than physical bullying (Wang, Iannotti, & Nansel, 2009), and school children recognize the higher prevalence of verbal bullying than physical bullying (Byrne, 1999; Corsaro & Eder, 1993; Hazler, 1996; Hazler, Miller, Carney, & Green, 2001; Rigby, 1996; Smith, Madsen, & Moody, 1999). Despite the higher prevalence of verbal bullying in school, teachers perceive verbal bullying to be less severe than physical bullying (Craig, Henderson, & Murphy, 2000). Additionally, professionals who work with youths were less likely to categorize an event as bullying without the presence of physical victimization (Hazler et al., 2001). Teachers and professionals dealing with youths were also less likely to show concern and less likely to intervene in situations that involve a verbal confrontation (Craig et al., 2000; Hazler et al., 2001). Despite the common notion that verbal bullying is less severe than physical bullying, research has shown that verbal bullying can negatively impact mental and physical health (Gladstone, Parker, & Malhi, 2006; Janssen, Craig, Boyce, & Pickett, 2004; Nishina, Juvonen, & Witkow, 2005). For instance, Nishina et al. (2005) found that verbal bullying was related to a greater number of physical health symptoms, such as headaches and sore throat/coughs, among adolescents. The present study examined physical and verbal bullying separately to see if they independently associate with physical health, and in combination to assess the potential additive or synergistic association with physical health.

Little is known about the association of bullying with physical health among LGB individuals. Based on the current literature demonstrating the negative impact of bullying on health among heterosexual individuals (e.g., Gini & Pozzoli, 2009), we expected that bullying would be negatively associated with physical health among lesbian/gay individuals and bisexual individuals. Prior research on sexual minority populations has often examined LGB individuals as one combined group. It is becoming increasingly clear that there may be differential health risk profiles among sexual identity groups (homosexual [i.e., lesbian/gay] vs. bisexual; e.g., Balsam, Beauchaine, Mickey, & Rothblum, 2005). For example, bisexual individuals are often stigmatized not only by their heterosexual peers (Eliason, 1997; Herek, 2002) but also by their lesbian/gay peers (Hutchins, 2005; Weiss, 2004), resulting in a phenomenon called “double discrimination” (Mulick & Wright, 2002). Therefore, it is possible that membership within different sexual minority groups (i.e., lesbian/gay or bisexual) may moderate the effects of bullying on physical health. Consequently, we assessed potential differences in the association of bullying on physical health among lesbian/gay and bisexual groups separately.

Methods

Participants (n = 623) were recruited through an online data collection service, Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (MTurk; www.MTurk.com). MTurk is a crowdsourcing service, offering a pool of 200,000 workers to perform various tasks for payment (Ross, Irani, Six Silberman, Zaldivar, & Tomlinson, 2010). Anyone in the United States over the age of 18 with a social security number or an individual tax identification number can apply to become a worker for MTurk. Recently, MTurk has also become an increasingly popular tool used in social science research to recruit participants from a large population pool to gather data from diverse populations (Buhrmester, Kwang, & Gosling, 2011; Goodman, Cryder, & Cheema, 2012; Paolacci, Chandler, & Ipeirotis, 2010). Researchers recruit participants by posting information about their experiment on MTurk for workers to decide if they are interested in participating. Participants recruited through MTurk were given a link to a survey that was housed on an online site, SurveyMonkey, which is a web company used for social science data collection (www.surveymonkey.com). SurveyMonkey enforces a strict privacy policy to ensure that all data remain securely stored on their server. The hour-long survey contained three attention checks throughout the questionnaire that participants had to pass in order to be included in the data analysis. Each attention check required participants to click on a certain response to ensure that participants were paying attention to the content of the questions. One attention check was inserted one third of the way into the questionnaire, another was inserted two thirds of the way in the questionnaire, and the final attention check was inserted near the end of the questionnaire. An example attention check asked participants to select a specific term. Participants who did not select the correct term were removed from the analyses. We eliminated participants who failed any one of the three attention checks. This requirement resulted in the removal of 77 participants (12.4%), retaining a sample size of 546 participants. Since our analyses focused on LGB individuals, participants who identified as “questioning” and “mostly heterosexual” were excluded (n = 64). One participant did not complete this question and was subsequently removed from the analysis. Additionally, due to the small number of participants who identified with a gender other than female and male (n = 18), we also omitted gender minority participants from the analysis. This left an analytic sample of 463 participants.

To be eligible to participate in the study, participants were required to self-identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender (LGBT; i.e., “I consent to take this study, and I certify that I identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender). Respondents completed questionnaires about their experiences of bullying in high school and their history of physical health conditions. At the end of the questionnaire, participants were debriefed through an informational message and paid two dollars for completing the survey. This participant payment amount is comparable to other studies utilizing the MTurk service (Paolacci et al., 2010). Researchers have shown that compensation rates do not affect the quality of the data gathered on MTurk (Buhrmester et al., 2011).

Sexual identity was assessed using one item that asked participants to indicate which of the following options (i.e., mostly heterosexual, bisexual, gay, lesbian, questioning) describes their sexual identity. Due to the smaller number of mostly heterosexual and questioning participants, we omitted these groups from the analysis. Sexual identity groups were coded as lesbian/gay (i.e., homosexual) and bisexual. Gay/lesbian was coded as 0, and bisexual was coded as 1.

Participants indicated their gender (“What is your gender”) as female, male, transgender, transwoman, transman, other identified, or “other, please define.” Due to the small number of participants who indicated a gender category other than female and male, we omitted the gender minority groups from the analysis. Female was coded as 0, and male was coded as 1.

Two items developed by the Gay, Lesbian, & Straight Education Network (Kosciw & Diaz, 2006) were used to assess if participants were ever verbally harassed or bullied in high school and if they were ever physically bullied or harassed (pushed, tripped, had object thrown at them, etc.) in high school. A “yes” to either question was coded as 1, and a “no” to either question was coded as 0. Participants were also asked to indicate the frequency of their bullying experience on a scale of less than a few times per year, a few times per year, monthly, weekly, and daily.

Participants were asked to indicate if a physician had ever diagnosed them with any of 34 common health conditions (e.g., heart disease, asthma, gastrointestinal disease). This health survey was modeled after the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Center for Health Statistics annual National Health Interview Survey (NHIS; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2000) and was validated against the NHIS measure in a nationally representative sample (Silver et al., 2013). These variables were summed to create an overall health problems outcome variable ranging from 0 (no health problems) to 34.

Following other studies on physical health, we assessed key behavioral variables (i.e., heavy drinking, current smoking) and demographic characteristics (i.e., age, weight) known to affect health (Conron, Mimiaga, & Landers, 2010; Sturm, 2002). For the heavy drinking variable, we asked participants during the past 30 days, “How many days did you have 5 or more drinks (4 for women),” which constitutes an assessment of at-risk alcohol drinking according to the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (2004). For smoking, we asked participants to indicate if they smoke (0 = does not smoke, 1 = does smoke). Additionally, since some distinct gender differences have been shown in the characteristics of bullying and its impact on health-risk behaviors (Bontempo & D’Augelli, 2002), we included gender as a control variable. Race was also included as an additional control variable given substantial evidence demonstrating its association with physical health (e.g., D. R. Williams, 1997).

T-tests were used to compare mean differences between the bisexual and the lesbian/gay groups. Chi-square tests were used to compare categorical variables (e.g., race/ethnicity). A multiple regression model was used to examine the association of bullying on physical health. To simplify the analysis, race was recoded as a dichotomous variable where 0 represented White and 1 represented racial/ethnic minority individuals. To test if sexual identity moderated the association between bullying and physical health, an interaction term of bullying * sexual identity was created and included in the multiple regression model (Baron & Kenny, 1986). All analyses were conducted using PASW Statistics version 20. This study was approved by the institutional ethics board at the University of Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

Results

Of the 463 participants (M age = 29.44, range = 18–66, SD = 9.79), 265 identified as bisexual and 198 identified as lesbian/gay. Of the total sample, 260 participants were female and 203 participants were male. Table 1 shows the specific comparisons between bisexual and lesbian/gay groups on demographic, behavioral, and bullying variables. Lesbian/gay individuals were significantly older than bisexual persons (d = 3.45, p < .001) and reported higher educational attainment than the bisexual group. Of the participants who recalled a bullying experience, the majority (85.3% of verbally bullied, 92.3% of physically bullied) indicated that they were verbally or physically bullied a few times per year or more.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Gay/Lesbian and Bisexuals.

| Variable | Gay/Lesbian (n = 198) n (%) | Bisexuals (n = 265) n (%) |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Age (M, SD)*** | 31.72 (10.77) | 28.27 (8.90) |

| Race | ||

| Caucasian/White | 152 (76.8) | 200 (75.5) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 8 (4.0) | 8 (3.0) |

| Black/African American | 15 (7.6) | 17 (6.4) |

| Latino/Hispanic | 12 (6.1) | 23 (8.7) |

| Other | 11 (5.5) | 17 (6.4) |

| Income (M, in dollars) | 37023.85 (30176.16) | 31230.73 (2841.30) |

| Education** | ||

| High school/GED equivalent | 25 (12.8) | 48 (18.3) |

| Some post-secondary | 66 (33.7) | 88 (33.5) |

| Completed college/university | 72 (41.6) | 101 (38.4) |

| Master’s degree or higher | 33 (16.8) | 26 (9.9) |

| Weight (lbs) (M, SD) | 175.90 (58.22) | 169.04 (54.67) |

| Smoking | 77 (68.1) | 160 (60.4) |

| Drinking (M, SD) | 2.37 (4.69) | 2.05 (4.96) |

| Health Problems | 2.96 (2.87) | 3.04 (3.18) |

| Verbal Bullying | 122 (61.9) | 153 (58.2) |

| Physical Bullying | 58 (29.3) | 74 (27.9) |

Note. The total n differs due to nonresponses.

Difference is significant at p < .05.

Difference is significant at p < .01.

Difference is significant at p < .001.

The mean number of health problems was 2.91 (SD = 3.01). The most common health problems reported by the participants were allergies (38.1%), vision problems (29.9%), flu (29.3%), and sinus infections (24.7%). There was no significant difference in mean number of health problems between lesbian/gay and bisexual individuals. The distribution of the health problems variables had significant skew (skew = 1.69) and kurtosis (kurtosis = 4.17), so a square root transformation on the variable was calculated for multivariable analyses.

To examine the association between verbal bullying and physical health, a multiple regression model was constructed with verbal bullying as a predictor variable and age, weight, gender, smoking, heavy drinking, and sexual identity as covariates. Verbal bullying was a significant predictor of physical health problems (b = .31, p = .001; Model 2; Table 2). Based on the predicted values from the model, participants who experience verbal bullying report on average 0.95 more physical health problems relative to those who have not been verbally bullied. We found similar results for physical bullying, where physical bullying was also a significant predictor of physical health problems (b = .34, p = .001; Model 3; Table 2). Based on the model, participants who reported being physically bullied experienced, on average, 0.91 more physical health problems than those who do not report any physical bullying. Additionally, we included verbal and physical bullying simultaneously into the model to see if they independently contribute to predicting physical health problems. Despite the significant overlap between verbal bullying and physical bullying (r = .45, p < .001), both types of bullying independently predicted physical health problems (Model 4; Table 2), suggesting there may be cumulative effects of verbal and physical bullying on physical health.

Table 2.

The Association Between Verbal and Physical Bullying and Physical Health Among LGBs.

| Model 1 (n=380) | Model 2a (n=377) | Model 3a (n=380) | Model 4a (n=377) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Variable | b [95% CI] | p | b [95% CI] | p | b [95% CI] | p | b [95% CI] | p |

|

| ||||||||

| Age | .023 [.013, .032] | <.001 | .023 [.013, .033] | <.001 | .023 [.014, .033] | <.001 | .023 [.013, .033] | <.001 |

| Weight | .004 [.003, .006] | <.001 | .004 [.003, .006] | <.001 | .004 [.003, .006] | <.001 | .004 [.003, .006] | <.001 |

| Drinking | −.001 [−.020, .019] | .957 | .001 [−.019, .020] | .898 | −.002 [−.021, .018] | .876 | .000 [−.019, .019] | .987 |

| Raceb | −.092 [−.309, .124] | .402 | −.067 [−.283, .149] | .543 | −.034 [−.250, .183] | .761 | −.041 [−.257, .176] | .713 |

| Genderc | −.319 [−.518, −.120] | .002 | −.298 [−.495, −.101] | .003 | −.338 [−.534, −.141] | .001 | −.314 [−.511, −.117] | .002 |

| Smokingd | .250 [.050, .451] | .014 | .223 [.023, .422] | .029 | .263 [.065, .461] | .009 | .235 [.036, .434] | .021 |

| Sexual Identitye | .094 [−.101, .288] | .344 | .101 [−.092, .294] | .303 | .096 [−.096, .287] | .327 | .096 [−.096, .288] | .326 |

| Verbally Bulliedd | .311 [.123, .499] | .001 | .221 [.007, .435] | .056 | ||||

| Physically Bulliedd | .339 [.135, .544] | .001 | 39 [.008, .470] | .041 | ||||

Note. CI = confidence interval. The physical health outcome variable was subjected to a square root transformation.

Model includes control variables from Model 1.

Caucasian/White as reference.

Female as reference.

0 = no, 1 = yes.

0 = gay/lesbian, 1 = bisexual.

To examine possible moderating factors of sexual identity on health, a multiple regression model was constructed with age, weight, gender, sexual identity, drinking, race, and smoking as covariates, and we included a bullying *sexual identity interaction variable. Sexual identity did not moderate the association between verbal bullying and physical health as the verbal bullying * sexual identity interaction term was not significant. However, sexual identity did moderate the association between physical bullying and health (b = −.15, 95% confidence interval [CI] = [−25, −.05], p = .005). When separate models were run for lesbian/gay and bisexual groups, physical bullying was a significant predictor of negative health outcomes for the bisexual group (b = .31, 95% CI = [.17, .44], p <.001), but not for the lesbian/gay group (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Effect of physical bullying on physical health among LGBs.

Discussion

Building on previous studies showing the effects of bullying on mental health among LGB individuals (Arseneault et al., 2010; Gruber & Fineran, 2008; Kaltiala-Heino et al., 2000; Mishna et al., 2009; Sourander et al., 2000), these findings extend prior research by suggesting that there may be a similar relationship between bullying and physical health among LGB individuals.

Specifically, we found that even after adjusting for a number of demographic variables and health-risk behaviors, there was a significant impact of bullying on physical health among LGB individuals. This relationship was found for both verbal and physical bullying when examined separately and simultaneously. This suggests there may be a cumulative effect of verbal and physical bullying on physical health. In the present study, physical bullying had a significant impact on health for bisexual individuals but not for lesbian/gay individuals. The association of verbal bullying on health was equally negative for both sexual minority groups. From the current measures included in the study, we were unable to determine why there would be a difference in moderation between verbal bullying and physical bullying. It is possible that specific frequency of physical bullying, severity of physical bullying, and type of physical bullying (e.g., physical assault vs. sexual harassment or assault) may differ among persons based on sexual identity. This would be an avenue for future researchers to explore. It would also be useful for future studies to examine how bisexuals and gay/lesbians differ in how they cope with bullying to see if differences in coping may explain some of these discrepant effects of bullying on health.

Our data support findings from previous work showing that interpersonal violence victimization is associated with physical health of sexual minority persons (Brown et al., 2009; Felitti et al., 1998; Irish, Kobayashi, & Delahanty, 2010; Wegman & Stetler, 2009). Additionally, we provide preliminary evidence suggesting that differences within sexual minority groups may influence the effects of bullying on health. This analysis was possible because a sufficiently large number of gays, lesbians, and bisexuals were recruited. Our study comprised a greater proportion of bisexuals than is found in some other prior studies (e.g., Berlan et al., 2010), but the proportions are comparable to the rates from a nationally representative sample. From the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance data collected in the United States, Kann et al. (2011) found that the about 1.0% to 2.6% (median 1.3%) of students identified themselves as gay or lesbian, and about 2.9% to 5.2% (median 3.7%) of students identified themselves as bisexual. This would suggest that our proportion of bisexuals to gay/lesbians (57% and 43% of LGBS, respectively) is comparable to that of the nationally representative sample.

For the present study, we corroborated previous findings that verbal bullying was more common than physical bullying (e.g., Kann et al., 2011). However, we did not find differential effects of physical and verbal bullying on health, as both types of bullying were associated with physical health. This finding supports previous work indicating an association between verbal bullying and negative health outcomes (e.g., Gladstone et al., 2005). This suggests that teachers should be made more aware of the negative impact of verbal bullying and be encouraged to intervene in instances of verbal bullying. Our findings suggest that physical and verbal bullying independently associated with physical health. In this study, we examined only the general terms “verbal” and “physical” bullying. Further research is needed to examine the health effects of other types of bullying such as indirect bullying (i.e., gossiping), social ostracism, and cyber bullying (Campbell, 2005; Hoover, Oliver, & Thomson, 2003; Van der Wal, De Wit, & Hirasing, 2003).

Several studies have found that rates of lifetime victimization are higher for bisexual individuals than gay men and lesbian women (Austin et al., 2008; Balsam, Rothblum, & Beauchaine, 2005). Evidence suggests that bisexual individuals experience a higher prevalence of bullying in schools (Berlan et al., 2010). However, in our study, we did not find any differences between the prevalence of bullying between bisexual and lesbian/gay groups. This discordance in findings may suggest differences in measurement of bullying (Griffin & Gross, 2004; Smith et al., 1999; Vaillancourt et al., 2008). For example, in our study we specifically assessed verbal bullying and physical bullying separately, whereas Berlan et al. (2010) operationalized bullying more generally by asking participants how often they were bullied.

These results must be interpreted in light of several limitations. First, generalizability is limited due to the nature of the sample being gathered using convenience-based methods in an online community. While workers on MTurk may be representative of the Internet-using population, they are generally younger, more educated, and consist of more women than when compared to the U.S. population (Ross et al., 2010). Second, all of the measures used in the study were based on self-reports, allowing for the possibility of reporting errors and recall biases. This limitation is particularly salient for a sample such as ours where the age range is fairly wide, and memory tends to be influenced by age. In an effort to address this, we conducted analyses with age as a moderator and did not find any significant interaction between age and bullying. It does not appear that older or younger individuals are more prone to reporting bullying in this sample. Other efforts to reduce reporting bias included asking participants to indicate the health conditions they were diagnosed with by a physician rather than a self-diagnosis. Furthermore, retrospective recall for school bullying has been shown to be quite accurate (Rivers, 2001b).

Third, we did not assess the specific details of the participant’s bullying experiences, such as characteristics of the perpetrator, severity of the experiences, or reasons for being bullied. We also did not examine the contextual differences between participants that may influence the impact of bullying on physical health, such as differences in parental support and reasons for being bullied (e.g., Janssen et al., 2004; Ma, 2002; Smokowski & Kopasz, 2005). Given evidence illustrating the contextual and characteristic differences in bullying experiences, it would be useful for future researchers to examine how these differences may mediate or moderate the impact of bullying on physical health. For instance, some evidence suggests that the impact of bullying may be especially harmful to those who receive less social support from family and peers (Davidson & Demaray, 2007; Demaray & Malecki, 2002; Holt & Espelage, 2007; Rigby & Slee, 1999).

We were unable to further analyze subgroups. For example, there were too few “mostly heterosexual” participants to analyze their responses. The “mostly heterosexual” sexual orientation has recently become a more visible sexual minority group in LGBT research. For instance, evidence suggests that mostly heterosexual women experience higher rates of bullying than their exclusively heterosexual counterparts (Berlan et al., 2010). Further research has found substantial differences between mostly heterosexual women and exclusively heterosexual women (Hughes, Szalacha, & McNair, 2010). Similarly, future studies should also examine the prevalence and impact of bullying among gender minority groups (i.e., transgender individuals). Last, our study did not include a heterosexual comparison group. While we assume the effects of bullying on physical health for LGB individuals are similar to the effects found for heterosexual persons, we would need to conduct the present study with heterosexual participants using the same variables (e.g., same cumulative health index) in order to make an appropriate comparison between heterosexual and LGB groups. While there are studies that show victimization is equally harmful to heterosexuals and sexual minority groups (Hughes, McCabe, Wilsnack, West, & Boyd, 2010), one study has shown that the impact of bullying on physical health is more severe for members of sexual minority groups (Gruber & Fineran, 2008). Thus, it would be useful to gather a heterosexual comparison group to examine if there are any differences in the association of bullying on physical health.

Nevertheless, the prevalence of physical bullying and verbal bullying in our LGB sample were higher than estimates from nationally representative samples of students— a pattern that is consistent with previous findings that compared prevalence of bullying between heterosexual and LGB students (e.g., Berlan et al., 2010). Compared to a nationally representative U.S. sample (U.S. Department of Justice, 2009) where the rates of bullying were estimated to be 29% of the youth population, we noted prevalence of bullying among our LGB sample to range from 23.5% to 67.0%. Some of these differences in prevalence may be attributed to differences in how we define bullying compared to other studies. Therefore, it would be useful for future researchers to conduct the same study for heterosexuals using the same definition of bullying that we used in our study to see if the differences in prevalence remain.

The present study highlights several areas for future research. While many of the previous studies have examined the impact of school bullying on children’s health (e.g., Gini & Pozzoli, 2009), the present study demonstrates that the detrimental effects of bullying on physical health may persist into adulthood. Therefore, it is particularly important for schools to focus on the prevention of both verbal and physical bullying, particularly among sexual minority youth. Second, there is a dearth of research on the perpetrators of bullying. Examining why students bully and whether they also may experience detriments in physical health will be an important future contribution. Third, future research should examine potential moderators that may mitigate the effects of bullying on health in order to better inform schools about potential treatment strategies for bullying victims. While we find that bullying is associated with negative physical health outcomes in adulthood, our study does explore on possible mechanisms by which this may occur. Future studies should examine the different possible biopsychosocial pathways in which victimization experiences may influence physical health. Fourth, we illustrate the need for future researchers to examine differences within sexual minority groups. Historically, research has often combined LGBs into one sexual minority category, which may not accurately represent the experience of adversity among lesbian/gay and bisexual groups separately (Andersen & Blosnich, 2013). Our study is among the few that show the differential impact that victimization may have within sexual minority groups. Specifically, physical bullying had a significant effect on the physical health of bisexual respondents, but the same effect did not replicate for lesbian/gay individuals. Interventions with sexual minority populations should also pay particularly close attention to specific sexual minority group membership, since there are significant disparities within sexual minority groups.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Contributor Information

Christopher Zou, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

Judith P. Andersen, University of Toronto Mississauga, Ontario, Canada.

John R. Blosnich, University of Rochester, Rochester, NY, USA; VISN-2 Center of Excellence for Suicide Prevention, Canandaigua, NY, USA.

References

- Andersen JP, & Blosnich J (2013). Disparities in adverse childhood experiences among sexual minority and heterosexual adults: Results from a multi-state probability-based sample. PLOS One, 8(1), e54691. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arseneault L, Bowes L, & Shakoor S (2010). Bullying victimization in youths and mental health problems: “Much ado about nothing?” Psychological Medicine, 40, 717–729. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709991383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austin SB, Jun HJ, Jackson B, Spiegelman D, Rich-Edwards J, Corliss HL, & Wright RJ (2008). Disparities in child abuse victimization in lesbian, bisexual, and heterosexual women in the Nurses’ Health Study II. Journal of Women’s Health, 17, 597–606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balsam KF, Beauchaine TP, Mickey RM, & Rothblum ED (2005). Mental health of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and heterosexual siblings: Effects of gender, sexual orientation, and family. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 114, 471–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balsam KF, Rothblum ED, & Beauchaine TP (2005). Victimization over the life span: A comparison of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and heterosexual siblings. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73(3), 477–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, & Kenny DA (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1173–1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berlan ED, Corliss HL, Field AE, Goodman E, & Bryn Austin S (2010). Sexual orientation and bullying among adolescents in the growing up today study. Journal of Adolescent Health, 46, 366–371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bontempo DE, & D’Augelli AR (2002). Effects of at-school victimization and sexual orientation on lesbian, gay, or bisexual youths’ health risk behavior. Journal of Adolescent Health, 30, 364–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown DW, Anda RF, Tiemeier H, Felitti VJ, Edwards VJ, Croft JB, & Giles WH (2009). Adverse childhood experiences and the risk of premature mortality. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 37, 389–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhrmester M, Kwang T, & Gosling SD (2011). Amazon’s Mechanical Turk a new source of inexpensive, yet high-quality, data? Perspectives on Psychological Science, 6(1), 3–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne B (1999). Ireland. In Smith PK, Morita Y, Junger-Tas J, Olweus D, Catalano R, & Slee P (Eds.), The nature of school bullying: A cross-national perspective (pp. 112–127). New York, NY: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell MA (2005). Cyber bullying: An old problem in a new guise? Australian Journal of Guidance and Counselling, 15(1), 68–76. [Google Scholar]

- Carlisle N, & Rofes E (2007). School bullying: Do adult survivors perceive long-term effects? Traumatology, 13, 16–26. [Google Scholar]

- Carlyle KE, & Steinman KJ (2007). Demographic differences in the prevalence, co-occurrence, and correlates of adolescent bullying at school. Journal of School Health, 77, 623–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conron KJ, Mimiaga MJ, & Landers SJ (2010). A population-based study of sexual orientation identity and gender differences in adult health. American Journal of Public Health, 100, 1953–1960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corsaro WA, & Eder D (1993). Children’s peer cultures. Annual Review of Sociology, 16, 197–220. [Google Scholar]

- Craig WM, Henderson K, & Murphy JG (2000). Prospective teachers’ attitudes toward bullying and victimization. School Psychology International, 21(1), 5–21. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson LM, & Demaray MK (2007). Social support as a moderator between victimization and internalizing-externalizing distress from bullying. School Psychology Review, 36, 383–405. [Google Scholar]

- Demaray MK, & Malecki CK (2002). The relationship between perceived social support and maladjustment for students at risk. Psychology in the Schools, 39, 305–316. [Google Scholar]

- Eliason MJ (1997). The prevalence and nature of biphobia in heterosexual undergraduate students. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 26, 317–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fekkes M, Pijpers FIM, Fredriks AM, Vogels T, & Verloove-Vanhorick SP (2006). Do bullied children get ill, or do ill children get bullied? A prospective cohort study on the relationship between bullying and health-related symptoms. Pediatrics, 117, 1568–1574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, Williamson DF, Spitz AM, Edwards V, . . .Marks JS (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14, 245–258. doi: 10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00017-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furlong MJ, Morrison GM, & Greif JL (2003). Reaching an American consensus: Reactions to the special issue on school bullying. School Psychology Review, 32, 456–470. [Google Scholar]

- Gini G, & Pozzoli T (2009). Association between bullying and psychosomatic problems: A meta-analysis. Pediatrics, 123, 1059–1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gladstone GL, Parker GB, & Malhi GS (2006). Do bullied children become anxious and depressed adults? A cross-sectional investigation of the correlates of bullying and anxious depression. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 194, 201–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman JK, Cryder CE, & Cheema A (2012). Data collection in a flat world: The strengths and weaknesses of Mechanical Turk samples. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 26, 213–224. [Google Scholar]

- Griffin RS, & Gross AM (2004). Childhood bullying: Current empirical findings and future directions for research. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 9, 379–400. [Google Scholar]

- Gruber JE, & Fineran S (2008). Comparing the impact of bullying and sexual harassment victimization on the mental and physical health of adolescents. Sex Roles, 59(1–2), 1–13. doi: 10.1007/s11199-008-9431-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hazler RJ (1996). Breaking the cycle of violence: Interventions for bullying and victimization. Bristol, PA: Accelerated Development.

- Hazler RJ, Miller DL, Carney JV, & Green S (2001). Adult recognition of school bullying situations. Educational Research, 43, 133–146. [Google Scholar]

- Herek GM (2002). Heterosexuals’ attitudes toward bisexual men and women in the United States. Journal of Sex Research, 39, 264–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt MK, & Espelage DL (2007). Perceived social support among bullies, victims, and bully-victims. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 36, 984–994. [Google Scholar]

- Hoover JH, Oliver RL, & Thomson KA (1993). Perceived victimization by school bullies: New research and future direction. Journal of Humanistic Education and Development, 32(2), 76–84. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes T, McCabe SE, Wilsnack SC, West BT, & Boyd CJ (2010). Victimization and substance use disorders in a national sample of heterosexual and sexual minority women and men. Addiction, 105, 2130–2140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes T, Szalacha LA, & McNair R (2010). Substance abuse and mental health disparities: Comparisons across sexual identity groups in a national sample of young Australian women. Social Science & Medicine, 71, 824–831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt R, & Jensen J (2006). The experiences of young gay people in Britain’s schools. The School Report. Retrieved from https://www.stonewall.org.uk/documents/school_report.pdf

- Hutchins L (2005). Sexual prejudice: The erasure of bisexuals in academia and the media. American Sexuality Magazine, 3(4). Retrieved from http://ai.eecs.umich.edu/people/conway/TS/Bailey/Bisexuality/American%20Sexuality/American%20Sexuality%20magazine%20-%20The%20erasure%20of%20bisexuals.htm [Google Scholar]

- Irish L, Kobayashi I, & Delahanty DL (2010). Long-term physical health consequences of childhood sexual abuse: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 35, 450–461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssen I, Craig WM, Boyce WF, & Pickett W (2004). Associations between overweight and obesity with bullying behaviors in school-aged children. Pediatrics, 113, 1187–1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaltiala-Heino R, Rimpelä M, Rantanen P, & Rimpelä A (2000). Bullying at school—An indicator of adolescents at risk for mental disorders. Journal of Adolescence, 23, 661– 674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kann L, O’Malley Olsen E, McManus T, Kinchen S, Chyen D, Harris WA, & Wechsler H (2011, June). Sexual identity, sex of sexual contacts, and health-risk behaviors among students in Grades 9–12: Youth risk behavior surveillance, selected sites, United States, 2001–2009. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 60(7), 1–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosciw JG, & Diaz EM (2006). The 2005 National School Climate Survey: The experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender youth in our nation’s schools. New York, NY: GLSEN. [Google Scholar]

- Kosciw JG, Greytak EA, Bartkiewicz MJ, Boesen MJ, & Palmer NA (2012). The 2011 National School Climate Survey: The experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender youth in our nation’s schools. New York, NY: GLSEN. [Google Scholar]

- Ma X (2002). Bullying in middle school: Individual and school characteristics of victims and offenders. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 13(1), 63–89. [Google Scholar]

- Matsui T, Kakuyama T, Tsuzuki Y, & Onglatco M (1996). Long-term outcomes of early victimization by peers among Japanese male university students: Model of a vicious cycle. Psychological Reports, 79, 711–720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishna F, Newman PA, Daley A, & Solomon S (2009). Bullying of lesbian and gay youth: A qualitative investigation. British Journal of Social Work, 39, 1598–1614. [Google Scholar]

- Mulick PS, & Wright LW Jr. (2002). Examining the existence of biphobia in the heterosexual and homosexual populations. Journal of Bisexuality, 2(4), 45–64. [Google Scholar]

- Nansel TR, Overpeck M, Pilla RS, Ruan WJ, Simons-Morton B, & Scheidt P (2001). Bullying behaviors among US youth prevalence and association with psychosocial adjustment. Journal of the American Medical Association, 285, 2094–2100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. (2004). Binge drinking defined. NIAAA Newsletter. Retrieved from http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/Newsletter/winter2004/Newsletter_Number3.pdf

- Nishina A, Juvonen J, & Witkow MR (2005). Sticks and stones may break my bones, but names will make me feel sick: The psychosocial, somatic, and scholastic consequences of peer harassment. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 34(1), 37–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paolacci G, Chandler J, & Ipeirotis P (2010). Running experiments on Amazon Mechanical Turk. Judgment and Decision Making, 5, 411–419. [Google Scholar]

- Rigby K (1996). Bullying in schools and what to do about it. Bristol, PA: Jessica Kingsley. [Google Scholar]

- Rigby K, & Slee P (1999). Suicidal ideation among adolescent school children, involvement in bully-victim problems, and perceived social support. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 29, 119–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivers I (2001a). The bullying of sexual minorities at school: Its nature and long-term correlates. Educational and Child Psychology, 18(1), 32–46. [Google Scholar]

- Rivers I (2001b). Retrospective reports of school bullying: Stability of recall and its implications for research. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 19, 129–141. [Google Scholar]

- Rivers I (2004). Recollection of bullying at school and their long-term implications for lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals. Crisis, 25, 169–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross J, Irani I, Six Silberman M, Zaldivar A, & Tomlinson B (2010). Who are the crowdworkers? Shifting demographics in Amazon Mechanical Turk. Retrieved from http://www.ics.uci.edu/∼jwross/pubs/RossEtAl-WhoAreTheCrowdworkers-altCHI2010.pdf

- Siann G, Callaghan M, Glissov P, Lockhart R, & Rawson L (1994). Who gets bullied? The effect of school, gender and ethnic group. Educational Research, 36, 123–134. [Google Scholar]

- Silver RC, Holman EA, Andersen JP, Poulin M, McIntosh D, & Gil-Rivas V (2013). Mental and physical health effects of acute exposure to media images of the 9/11 attacks and the Iraq war. Psychological Science, 24, 1623–1634. doi: 10.1177/0956797612460406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith PK, Madsen KC, & Moody JC (1999). What causes the age decline in reports of being bullied at school? Towards a developmental analysis of risks of being bullied. Educational Research, 41, 267–285. [Google Scholar]

- Smokowski PR, & Kopasz KH (2005). Bullying in school: An overview of types, effects, family characteristics, and intervention strategies. Children & Schools, 27, 101–110. [Google Scholar]

- Sourander A, Helstela L, Helenius H, & Piha J (2000). Persistence of bullying from childhood to adolescence—A longitudinal 8-year follow-up study. Child Abuse & Neglect, 24, 873–881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturm R (2002). The effects of obesity, smoking, and drinking on medical problems and costs. Health Affairs, 21, 245–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2000). National Center for Health Statistics: National Health Interview Survey Questionnaire 2000. Hyattsville, MD: Author. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Justice. (2009). National Crime Victimization Survey: School Crime Supplement, 2009 (ICPSR28201-v1). Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research [Distributor], 2011–01-21. doi: 10.3886/ICPSR28201.v1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vaillancourt T, McDougall P, Hymel S, Krygsman A, Miller J, Stiver K, & Davis C (2008). Bullying: Are researchers and children/youth talking about the same thing? International Journal of Behavioral Development, 32, 486–495. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Wal MF, De Wit CA, & Hirasing RA (2003). Psychosocial health among young victims and offenders of direct and indirect bullying. Pediatrics, 111, 1312–1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vieno A, Gini G, & Santinello M (2011). Different forms of bullying and their association to smoking and drinking behavior in Italian adolescents. Journal of School Health, 81, 393–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Iannotti RJ, & Nansel TR (2009). School bullying among adolescents in the United States: Physical, verbal, relational, and cyber. Journal of Adolescent Health, 45, 368–375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wegman HL, & Stetler C (2009). A meta-analytic review of the effects of childhood abuse on medical outcomes in adulthood. Psychosomatic Medicine, 71, 805–812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss JT (2004). GL vs. BT: The archaeology of biphobia and transphobia within the US gay and lesbian community. Journal of Bisexuality,3(3–4), 25–55. [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR (1997). Race and health: basic questions, emerging directions. Annals of Epidemiology, 7, 322–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams T, Connolly J, Pepler D, & Craig W (2005). Peer victimization, social support, and psychosocial adjustment of sexual minority adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 34, 471–482. [Google Scholar]

- Wilsnack SC, Kristjanson AF, Hughes TL, & Benson PW (2012). Characteristics of childhood sexual abuse in lesbians and heterosexual women. Child Abuse & Neglect, 36, 260–265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolke D, Woods S, Bloomfield L, & Karstadt L (2001). Bullying involvement in primary school and common health problems. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 85, 197–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]