Abstract

Introduction

Pancreatic cancer is one of the deadliest cancers and pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) is recommended as the optimal operation for resectable pancreatic head cancer. Minimally invasive surgery, which initially emerged as hybrid-laparoscopy and recently developed into total laparoscopy surgery, has been widely used for various abdominal surgeries. However, controversy persists regarding whether laparoscopic PD (LPD) is inferior to open PD (OPD) for resectable pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) treatment. Further studies, especially randomised clinical trials, are warranted to compare these two surgical techniques.

Methods and analysis

The TJDBPS07 study is designed as a prospective, randomised controlled, parallel-group, open-label, multicentre noninferiority study. All participating pancreatic surgical centres comprise specialists who have performed no less than 104 LPDs and OPDs, respectively. A total of 200 strictly selected PD candidates diagnosed with PDAC will be randomised to receive LPD or OPD. The primary outcome is the 5-year overall survival rate, whereas the secondary outcomes include overall survival, disease-free survival, 90-day mortality, complication rate, comprehensive complication index, length of stay and intraoperative indicators. We hypothesise that LPD is not inferior to OPD for the treatment of resectable PDAC. The enrolment schedule is estimated to be 2 years and follow-up for each patient will be 5 years.

Ethics and dissemination

This study received approval from the Tongji Hospital Ethics Committee of Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, and monitor from an independent third-party organisation. Results of this trial will be presented in international meetings and published in a peer-reviewed journal.

Trial registration number

Keywords: Pancreatic disease, Pancreatic surgery, Clinical trials, Gastrointestinal tumours

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This trial aims to compare long-term safety of laparoscopic pancreaticoduodenectomy (LPD) and open PD (OPD) for resectable pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) treatment in a large multicentre setting and will provide evidence on performance of PDAC resection.

All participating pancreatic surgical centres are qualified with experienced surgeons who have performed no less than 104 LPDs and OPDs, respectively.

Each patient will attend a follow-up of at least 5 years to determine the study primary outcome, the 5-year overall survival rate, which is the most used indicator for describing cancer survival.

This is an open-label trial; accordingly, participants and clinicians will not be blinded to interventions.

The primary outcome of this trial will be derived from data acquired during the long-term follow-up, requiring high levels of follow-up compliance and challenging coordination between surgeons, oncologists, visitors and patients.

Introduction

Pancreatic cancer is a highly fatal malignancy with poor responses to therapy and is estimated to be the fourth leading cause of cancer mortality.1 Among all types of pancreatic cancer, the vast majority are pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC).2 Pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD), the standard procedure for resectable pancreatic head cancer, is considered as one of the subtlest abdominal surgical procedures, involving both difficult resection and complex reconstruction procedures.2 3 Compared with traditional open surgery, minimally invasive surgery (MIS) has several advantages, such as small incision, minimal intraoperative bleeding, and fast postoperative recovery, among others,4 which are essential factors promoting the development of surgical treatments. However, the long-term survival benefits of MIS in patients with cancer remains controversial. For example, minimally invasive radical hysterectomy showed poorer overall survival (OS) and disease-free survival (DFS) than open surgery for patients with early-stage cervical cancer.5

Since its inception by Gagner and Pomp, laparoscopic PD (LPD) has been increasingly performed owning to its potential technical advantages.6 7 As shown by the ISGPS Evidence Map of Pancreatic Surgery,8 an increasing number of studies, including four large-scale randomised controlled trials (RCTs), have reported the safety and feasibility of LPD for treatment of periampullary or pancreatic tumours.9–13 Our previous studies, including a multicentre RCT, indicated that LPD is a safe and feasible procedure associated with a shorter length of stay and comparable short-term outcomes to open PD (OPD) by highly experienced surgeons who have passed the learning curve.12 14 However, the application of LPD to PDAC treatment is concerning. Several studies have focused on the comparison of LPD and OPD for PDAC treatment and suggested that LPD was associated with equivalent oncologic outcomes and promising superior long-term survival outcomes compared with OPD.15 However, retrospective studies are associated with inherent limitations, including patient selection biases, missing or incomplete data and unaccounted-for variables, making results difficult to interpret definitively. No RCTs have investigated the effects of LPD and OPD on survival in patients with PDAC.

To explore the long-term safety and efficacy of LPD in patients with PDAC using high-level evidence, the Minimally Invasive Treatment Group in the Pancreatic Disease Branch of China’s International Exchange and Promotion Association for Medicine and Healthcare designs and conducts this prospective large-scale multicentre RCT to analyse outcomes of interest, immediately after the TJDBPS01 trial, which interpreted the safety and feasibility of LPD compared with those of OPD. Accordingly, this trial aims to compare the long-term oncological and short-term surgical outcomes of LPD and OPD performed by highly experienced surgeons that have surmounted the learning curve for PDAC treatment.

Methods and analysis

Trial design

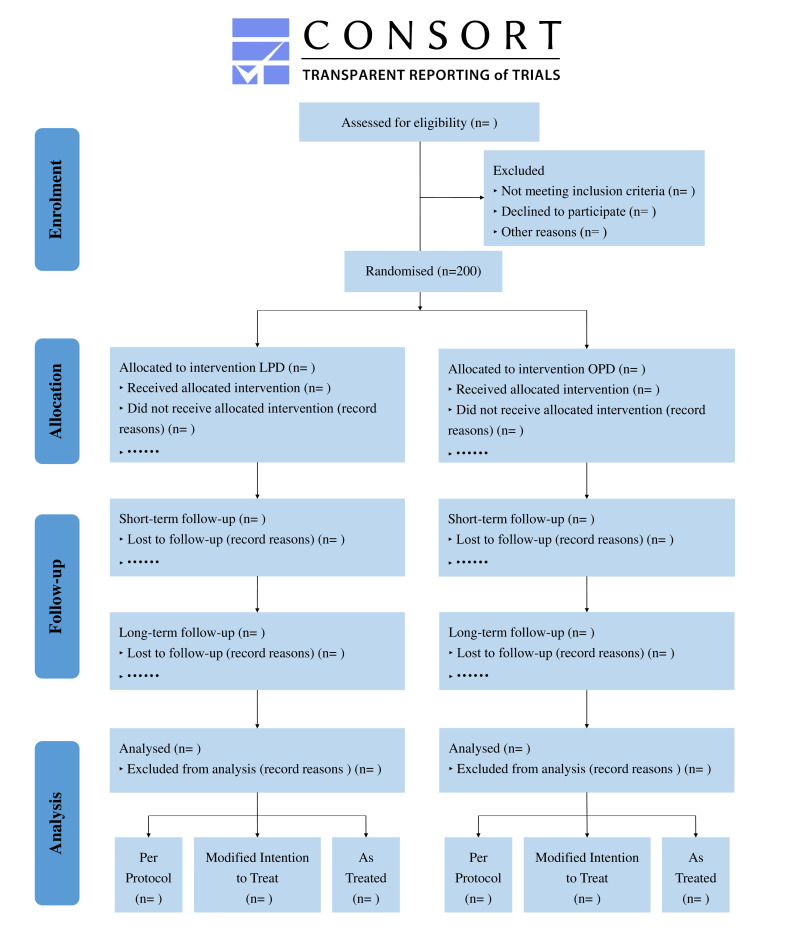

This trial is characterised as a prospective, multicentre, randomised controlled and open-label study comprising two parallel groups of patients undergoing OPD and LPD. Patients diagnosed with pancreatic malignant tumours requiring PD will be consecutively recruited. This study will be conducted at ten high-volume pancreatic surgery centres in China, with surgeries being conducted by experienced surgeons. After providing written informed consents, 200 patients will be preoperatively allocated in a 1:1 ratio to either the LPD or OPD arm. The recruitment duration is estimated to be 2 years and the follow-up duration will be 5 years. The primary endpoint of this trial is the 5-year OS rate. The study will be prepared, analysed and reported in accordance with the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) guidelines,16 as presented in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram for TJDBPS07. CONSORT, Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials; LPD, laparoscopic pancreaticoduodenectomy; OPD, open pancreaticoduodenectomy.

Qualifications of participating surgeons and centres

The responsible participating surgeons shall satisfy the following qualifications as previously described in the TJDBPS01 study12: (1) having completed no less than 104 cases of LPDs; (2) having completed no less than 104 cases of OPDs14 and (3) having completed trainings of the Tongji Hospital LPD training programme. Moreover, the participating centres shall perform more than 50 PDs annually. Surgeons willing to participate shall offer one recently unedited LPD and OPD surgery video, respectively, to the TJDBPS07 research council for evaluation. If the research council approves the surgical techniques, the surgeon and the centre will be permitted to participate in this study as a collaborator. Eligible patients will be discussed at regularly scheduled multidisciplinary team (MDT) meetings. Randomisation and assignment of a study-specific ID will be performed by the study sponsor.

Population and eligibility criteria

All adult patients indicated for elective PD because of a pancreatic mass will be screened for eligibility. Eligible patients will be assessed by the pancreatic MDTs of the participating centres. The MDTs should confirm that the pancreatic mass is highly suspected to be a pancreatic malignant tumour and of sufficient concern to require resection. Imaging data of contrast enhanced multi-thin sliced CT scan (1 mm) with or without endoluminal ultrasonography will be regarded as the standard evaluation for each PD candidate. The last CT imaging should be performed within 4 weeks before the surgery. Histological diagnoses of malignancies are encouraged to be acquired but not a necessity.17 All patients will sign the informed consent and be allowed to leave the trial at any time. The exact inclusion and exclusion criteria are below.

Inclusion criteria

Age between 18 years and 75 years.

Histologically confirmed PDAC or clinically diagnosed PDAC by an MDT without histopathologic evidence.

Patients feasible to undergo both LPD and OPD according to MDT evaluations.

Patients understanding and willing to comply with this trial.

Provision of written informed consent before patient registration.

Patients meeting the curative treatment intent in accordance with clinical guidelines.

Exclusion criteria

Patients with distant metastases, including peritoneal, liver, distant lymph node metastases and involvement of other organs.

Patients requiring left, central or total pancreatectomy or other palliative surgery.

Preoperative American Society of Anaesthesiologists (ASA) score ≥4.

History of other malignant disease.

Pregnant or breastfeeding women.

Patients with serious mental disorders.

Patients treated with neoadjuvant therapy.

Patients with vascular invasion and requiring vascular resection as evaluated by the MDT team according to abdominal imaging data.

Body mass index >35 kg/m2.

Patients participating in any other clinical trials within 3 months.

Endpoints

The primary endpoint of this trial is the 5-year OS rate, which is defined as the percentage of patients in this trial who are alive 5 years postoperatively (time frame: 5 years postoperatively).

Other crucial indicators are included as secondary endpoints, including (1) OS (ie, the interval between the day of surgery and the day of death for various reasons (time frame: 5 years postoperatively)); (2) DFS (ie, the interval between the day of surgery and the day of tumour recurrence (time frame: 5 years postoperatively); (3) 90-day mortality (ie, the percentage of patients who died within 90 days postoperatively). Mortality will be calculated by dividing the number of patients who died by the number of all patients undergoing surgical treatment; (4) complication rate (complications related to PD, including major complications with Clavien-Dindo ≥3,18 postoperative pancreatic fistula,19 postoperative bile leak,20 postpancreatectomy haemorrhage,21 delayed gastric emptying22 and chyle leak,23 are defined according to the International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery) (5) Comprehensive Complication Index24 (calculated as the sum of all complications that are weighted for their severity, available at www.assessurgery.com); (6) length of stay (ie, the number of nights spent in the hospital from the end of the surgical procedure until discharge or death) and (7) intraoperative indicators, including estimated blood loss and operation time.

Sample size

The sample size calculation was performed according to the primary endpoint, the 5-year OS rate, and the non-inferiority design of this trial. Assumptions were made based on a previous study by Kuesters et al,25 which compared LPD with OPD for PDAC treatment with the 5-year OS rate being 20% in the LPD group and 14% in the OPD group. Based on the 6% decrease in 5-year OS rate in the OPD group compared with the LPD group, the sample size required for each group was estimated to be 86 patients to achieve a non-inferiority limit of 10% at a one-tailed significance level of 2.5% with a power of 80% and a balanced design (1:1 ratio). Moreover, the primary analyses will be based on the modified intention-to-treat (mITT), per-protocol (PP) and as-treated (AT) sets. We aimed to reach a statistical power of 80% when analysing the smallest population, namely the PP set.

Patients converted from LPD to open surgery will not be included in the PP set. Patients will be randomised in a 1:1 manner to either the LPD or OPD arm, with the maximum conversion rate from LPD to OPD assumed to be 10%, resulting in a ratio of up to 9:10 in the PP set. To meet these assumptions, 83 patients in the LPD group and 91 patients in the OPD group will be needed for analysis using the one-sided t test at a one-sided significance level of 0.025. PASS V.15.0.5 will be used for the calculations. An additional 10% of patients will be needed to be randomised considering the non-resectable patients, patients withdrawing from the study, and patients lost to follow-up. Accordingly, 100 patients in the LPD arm and 91 patients in the OPD arm will be randomised. The randomisation ratio of this trial is 1:1, requiring 100 patients in each arm and 200 patients in total to be included for randomisation.

Patient timeline and description of trial visits

The study duration is estimated to be seven calendar years, with an enrolment schedule of 2 years and a follow-up period of 5 years for each patient. The end of the trial was defined as five calendar years since the last enrolled patient received surgery. This protocol is reported in accordance with the guidelines of the Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials (SPIRIT) (table 1, online supplemental file 1).26

Table 1.

Schedule of study enrolment, interventions, and assessments

| Time point | Study period | ||||||||||||||||

| Enrolment | Allocation | Treatment | Discharge | Post-allocation | Close-out | ||||||||||||

| Outpatient clinic /Admission | Before Surgery | Surgery | After Surgery | Month 1 (T1) |

Month 3 (T2) |

Month 6 (T3) |

Month 9 (T4) |

Month 12 (T5) |

Month 18 (T6) |

Month 24 (T7) |

Month 30 (T8) |

Month 36 (T9) |

Month 42 (T10) |

Month 48 (T11) |

Month 54 (T12) |

Month 60 (T13) |

|

| Enrolment | |||||||||||||||||

| Eligibility screen | × | ||||||||||||||||

| Informed consent | × | ||||||||||||||||

| Allocation | × | ||||||||||||||||

| Interventions | |||||||||||||||||

| LPD | × | ||||||||||||||||

| OPD | × | ||||||||||||||||

| Assessments | |||||||||||||||||

| Baseline characteristics | × | ||||||||||||||||

| Blood routine | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | |||

| Blood biochemistry | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | |||

| Tumour marker | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | |||

| Abdominal CT scan | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | |||

| Surgical record | × | ||||||||||||||||

| Postoperative record | × | ||||||||||||||||

| Pathological findings | × | ||||||||||||||||

| Adjuvant therapy | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | ||||

| Survival status | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | |||||

LPD, laparoscopic pancreaticoduodenectomy; OPD, open pancreaticoduodenectomy.

bmjopen-2021-057128supp001.pdf (76.9KB, pdf)

Data collection and assessment are recommended to be conducted at the responsible surgical centre. Baseline data will be collected during the screening/baseline visit, and surgical data will be collected intraoperatively and postoperatively.

Short-term follow-ups will be conducted 1 day, 1 week, 1 month, and 3 months postoperatively, and follow-up contents will include laboratory inspection indicators, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) score, Karnofsky Performance Scale (KPS) score, postoperative wound recovery, wound pain level, drainage of each drainage tube postoperatively, postoperative recovery (ie, time until getting out of bed, imported food, and so on), weight, adverse events, combined medication and postoperative complications.

Long-term follow-ups will be conducted every 3 months within the first postoperative year and every 6 months from the second postoperative year onwards. The following follow-up contents will be tracked and recorded: clinical evaluations including internal inspections (such as weight, KPS score and ECOG score), chemotherapy-related adverse events, imaging items to prove the existence of tumour recurrence or metastasis (record the date of recurrence, location and follow-up treatment), the date of death, and the cause of death (ie, disease-related or treatment-related mortality).

Randomisation and blinding

Eligible patients signed the informed consent form will be screened within 1 week prior to randomisation. Randomisation will be assigned on the day the preoperative evaluation is finished and the patient is diagnosed with PDAC, eligible for PD. We will employ a 1:1 randomisation pattern for arms A and B, stratified by participating centres. Random numbers will be generated by SAS software V.9.40 (SAS Institute) and randomisation will be performed through a centralised computer-generated system by providing random numbers using dynamic blocks. Within each block, randomisation is balanced, and every patient is assigned to a treatment using the randomisation scheme.

This is an open-label trial, and randomisation procedure and outcome will not be blinded to patients and surgeons. However, data collectors, outcome assessors and data analysts will be blinded during statistical analysis. Surgeons will not participate in the data collection process which will be conducted by an independent team. Analysis processes will be blinded, and the statistician will be provided with only group codes instead of group names.

Intervention

Surgical procedures need to comply with PD technique standards as previously described.27 Any appropriate changes in surgical procedures according to the surgeon’s own experience and preference are permitted, including changes in procedure order, surgical approach and anastomosis method. All changes will be recorded in the case report form.

Experimental intervention-LPD techniques

Patients will take a supine position and undergo general anaesthesia. Five trocars in total will be used. Routine and standard lymph node dissections will be maintained as recommended by guidelines. The pancreatic stump will be sent for quick frozen pathological examination intraoperatively; moreover, it is necessary to confirm that the pancreatic margin specimen is pathologically negative before digestive tract reconstruction. Surgeons will determine the reconstruction type according to their experiences and preferences. After reconstruction, two drainage tubes are routinely placed, with one near the anastomosis of the pancreaticojejunostomy and the other near the anastomosis of the bile jejunum.

Conversion to open surgery is defined as the use of any skin incision during LPD for other than trocar placement or surgical specimen removal. For cases of conversion, data will be analysed in the LPD group in an ITT manner. However, reasons for conversion shall be realistically registered and carefully recorded.

Control intervention-OPD techniques

Open surgery shall be performed by the same group of surgeons as LPD. Key steps are performed essentially as described in the LPD group. Methods used for reconstruction during OPD must be consistent with those during LPD in the same single centre.

Concomitant treatment

The TJDBPS07 trial follows TJDBPS01 which compared LPD and OPD; accordingly, the principles of perioperative management are similar to those previously described.27 Whatever medical devices and materials that are most used in daily practice of each participant centre can be used if recorded carefully in surgical records. Antibiotics are given to patients 30 minutes before skin incision and 2 hours after incision. Patient-controlled analgesia will be used to control postoperative pain. Time to remove the nasogastric tube depends on each patients’ situation evaluated by doctors of each participating centre; early removal is encouraged. The abdominal drains will be placed routinely for patients. The timepoint of drain removal depends on each patient’s manifestation, laboratory examination results (the concentration of drain fluid amylase (DFA) on postoperative days (PODs) 1 and 3), and imaging findings. In patients with a DFA concentration of less than 5000 U/L on POD 1, early drain removal at 72 hours is recommended. In patients with a DFA concentration of more than 5000 U/L on POD 1, drain removal will be decided by the corresponding surgeon according to the patient’s situation. Patients can be discharged if they meet the following discharge criteria: no need for intravenous infusion, well tolerance of oral solid or semisolid food, no need for intravenous analgesics, well wound healing, well tolerance of independent walking at least 250 m in a plain road, well major organ function with near-normal haematological parameters.

After surgical resection, patients pathologically diagnosed with PDAC will receive adjuvant chemotherapy according to the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guideline.28 Written informed consent for adjuvant chemotherapy should be obtained. Different regimens recommended in the aforementioned guideline are permitted, and the treatment duration is at the discretion of the responsible treating oncologist. Detailed information on adjuvant chemotherapy will be recorded. Relapse cases will be treated according to the recommendations of the NCCN guideline at the corresponding participating centres.

Data collection and management

All data will be collected using an electronic case report form. The datasets generated during the study will be stored in a local database, which is managed by the data collection group of Tongji Hospital. Investigators from each participating institution will have access to the data of their respective patients. All data are pseudonymised, and patient details are encoded.

Data collection will include variables related to patient demographics, intraoperative information, histopathological information, postoperative clinical findings, adjuvant chemotherapy and follow-up.

Patient demographics: age, gender, height (cm), weight (kg), smoking, drinking, main complaint, clinical diagnosis, comorbidities, surgical history, underlying malignant disease, ECOG score, ASA score, imaging results, preoperative blood samples (ie, haemoglobin level, white cell count, and granulocyte: lymphocyte ratio), plasma total bilirubin level, related tumour markers (ie, CA19–9, CA125 and carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA)), preoperative biliary drainage, and date of admission.

Intraoperative information: operation date, surgical approach (laparoscopic or open), conversion to open surgery, intraoperative death, texture of pancreas, diameter of the main pancreatic duct, placement of intra-abdominal drain, type of reconstruction, anastomosis approach (intracorporeal or extracorporeal), anastomosis performance (linear stapler, circular stapler, hand-sewn or combinations), total operative time, each anastomosis time (pancreaticojejunostomy, cholangiohepaticojejunostomy and gastroenterostomy), intraoperative complications, estimated blood loss and intraoperative blood transfusion.

Histopathological information: tumour location, tumour size, histological type, surgical margin status (R0 resection rates), number of lymph nodes, number of positive lymph nodes, depth of invasion (T classification), lymph node status (N classification) and American Joint Committee on Cancer staging.

Postoperative clinical findings: length of postoperative stay, postoperative blood transfusion, length of intravenous analgesic use, drain production and amylase, postoperative blood samples (ie, haemoglobin level, white cell count and granulocyte: lymphocyte ratio), plasma total bilirubin level, related tumour markers (ie, CA19–9, CA125 and CEA), date of patient mobilisation, date of liquid diet, date of drain removal, postoperative complication, reoperation, Clavien-Dindo grade, adverse event, cost of surgery and cost of hospitalisation.

Adjuvant chemotherapy: date of adjuvant chemotherapy, chemotherapy regimens, side effects, imaging results, haemoglobin level, white cell count and related tumour markers (ie, CA19–9, CA125 and CEA).

Follow-up: date of follow-up visit, patient status (alive, dead or lost to follow-up), ECOG score, KPS score, imaging results, related tumour markers (ie, CA19–9, CA125 and CEA), DFS and OS.

Risk of bias

All adult patients with pancreatic masses eligible for PD will be screened in all participating centres. The recruited patients will be expected to be generalisable and representative to the wider population. Standard randomisation will be conducted to ensure comparable baseline characteristics between each group. To minimise confounding, allocations will be stratified by centre.

The primary outcome of this trial is the 5-year OS rate, which is objective and will be obtained from the planned follow-up data. The participants, surgeons, and nursing staff will not be blinded to interventions due to the characteristics of this trial, which compares MIS and conventional open surgery. The responsible surgeons will not be involved in the postoperative management of patients and determination of patients’ discharge. Data collectors, outcome assessors, and data analysts will all be blinded to surgical techniques.

To minimise missing data bias, data for the primary outcome will be routinely collected and regularly reviewed.

Results of this trial will be reported in accordance with the CONSORT statement16 to minimise reporting bias. In addition, the trial protocol is reported according to the SPIRIT statement26 to assure full transparency throughout this trial and subsequent reporting.

Assessment of cross-over patients

Conversion from LPD to OPD is closely associated with intraoperative situations, including technical infeasibility and significant bleeding, which is unavoidable even for experienced surgeons who have passed the learning curves, making it impossible to eliminate conversion by modifying inclusion and exclusion criteria. The conversion rate in our previous trial comparing LPD and OPD for pancreatic or periampullary tumours was 4%.12 Considering the techniques complexity in LPD for PDAC, the maximum conversion rate within this trial is cautiously estimated to be 10%. Reasons for conversion will be recorded in detail and further evaluated in the subgroup analysis.

Statistical analysis

A statistical analysis plan will be developed and agreed on by the data collection group. All main statistical analyses will be performed according to an ITT principle, and the primary analysis will be based on the mITT, PP and AT set. Patients deemed unresectable intraoperatively or who do not receive surgical resection will not be considered in any of the analysis sets. The mITT set will comprise all patients in the group to which they were randomised regardless of the actual received surgery. The PP set will include patients without major protocol violations. Patients converted from LPD to OPD will not be included in the PP set. The AT set will be analysed with considerations of the actual treatment of patients, rather than their randomisation. For robust interpretation, the results of the three primary analysis sets should lead to similar conclusions; otherwise, possible reasons behind discrepancies must be discussed. OS and DFS will be analysed from the date of pancreatic resection to the date of death (for OS) or date of regional recurrence or systemic spread (for DFS). The OS and DFS curves for the entire follow-up period will be estimated according to Kaplan-Meier method and compared using a log-rank test. Time-specific OS and DFS probabilities at appropriate time points will be derived from the survival curves and the Greenwood estimate will be used to construct corresponding a 95% CI. HRs and two-sided 95% CIs will be estimated using a Cox regression model after confirming the proportional hazards assumptions.

In summary, continuous data will be presented as mean±SD and will be compared using Student’s t test or Mann-Whitney U test. Categorical variables will be compared using the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. Statistical analyses will be conducted using SAS software V.9.4 (SAS Institute). A p<0.05 (two-tailed) will denote statistical significance.

Monitoring

Throughout the trial, a trained, qualified and independent monitor will periodically visit each participating centre to randomly check protocol compliance, compliance with the inclusion and exclusion criteria, proper implementation, obtainment of informed consent forms, source data verification and reporting of serious adverse events. Adverse events will be graded using the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events V.5.0.29 The Hospital Ethical Committee and Chinese Clinical Trial Registry are responsible for collection and management of these data. Moreover, an independent agency will handle the auditing every month.

Discussion

The TJDBPS07 trial is designed as a prospective, multicentre, randomised controlled, and open-label trial to assess the long-term oncological and short-term surgical outcomes of LPD and OPD for PDAC treatment. The results of our TJDBPS01 trial suggested that LPD is a safe and feasible procedure for treating pancreatic or periampullary tumours, with comparable short-term outcomes to OPD in highly experienced hands.12 27 The TJDBPS07 trial follows TJDBPS01 and focuses on the comparison of LPD and OPD for treatment of resectable PDAC. In consideration of the complexity and difficulty of PD, surgeons participating in this trial are required to complete a structured training programme for LPD and pass the learning curve by finishing a minimum of 104 LPDs, as suggested by the results of a retrospective study on the learning curve for LPD in China.14

Minimally invasive surgeries have gained increasing popularity in recent years because they have shown some promise in improving perioperative outcomes.30 Nevertheless, their long-term effects on patients with malignant diseases require further exploration. Several RCTs focused on this topic and reported different conclusions. A study by Yu et al found that laparoscopic distal gastrectomy and open surgery had comparable DFS and OS in patients with locally advanced gastric cancer.31 Moreover, a study by Kitano et al concluded that laparoscopic D3 surgery was not inferior to open surgery in terms of OS in patients with stage II and III colon cancer.32 However, research by Ramirez et al suggested that for patients with early cervical cancer, minimally invasive radical hysterectomy resulted in lower rates of DFS and OS than open radical hysterectomy.5 The current guidelines of NCCN suggest that minimally invasive surgeries are feasible and safe for patients with hepatobiliary cancer,33 colon cancer,34 rectal cancer,35 ovarian cancer,36 cervical cancer37 and pancreatic cancer,28 among others. Meanwhile, many of these guidelines state that their long-term safety needed to be further evaluated in more high-quality researches.

With a 5-year survival rate of approximately 10%, the highly fatal pancreatic cancer is becoming an increasingly common cause of cancer-related mortality. Surgical resection represents the only chance of cure for patients with resectable pancreatic cancer.38 An increasing number of researchers are interested in the therapeutic effects of LPD on patients with PDAC in recent years,39 but there is still a lack of prospective research supporting its long-term safety in these patients. Available evidence is based on a few retrospective studies with limited quality.40 The data of 322 patients with PDAC (108 undergoing LPD and 214 undergoing OPD) demonstrated that LPD was technically feasible for PDAC treatment and was associated with better length of stay, postoperative recovery, and pursuing adjuvant treatment than OPD. This study simultaneously showed comparable OS but longer DFS in LPD than OPD,41 while other studies have indicated that the long-term survival and perioperative outcomes were comparable between LPD and OPD for treatment of selected PDAC patients.42–44 Considering the controversies among existing publications and limitations of observational studies, doctors and researchers in the field of PDAC emphasise the necessity and importance of large-scale multicentre RCTs.

In conclusion, the TJDBPS07 trial is a multicentre randomised controlled, non-inferiority trial investigating the long-term survival and the preoperative safety of LPD and OPD for resectable PDAC. This trial aims to evaluate differences in the 5-year OS rate between LPD and OPD for PDAC treatment. The results of this trial will provide high-level evidence for guiding the daily practice of PDAC management.

Trial status

The protocol of this trial was proposed by the investigator from Tongji Hospital, and the final version was approved by Tongji Institutional Review Board. The first enrolled patient has been given the randomised number in August 2019. All 10 centres are actively recruiting patients by the time this protocol is submitted. Recruitment will approximately be completed by March 2022.

Patient and public involvement

This trial will not involve either patients or the public in the design, recruitment, conduct of the study or measurement of outcomes. The trial results will not be notified to every single patient, while instead, the results will be presented in academic conferences, and disseminated via open-access and peer-reviewed journals. This trial will investigate patient-reported outcomes, using tools such as questionnaires about quality of life.

Ethics and dissemination

Each participant will sign an informed consent document before inclusion; this form is provided by a qualified team member and subsequently sent to and preserved by the data collection team. All participations are voluntary and have the right to withdraw from the study for any reason whenever they want to. If they do withdraw, they will still receive standard treatment according to local hospital procedures. The study will be conducted in accordance with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments.45 This trial was approved by Tongji Hospital Ethics Committee (approval number: TJ-IRB20190318) in March 2019. Local ethical approval was confirmed from each participating centre before recruiting at other centres. All authors have access to study data and reviewed and approved the final manuscript. The results of this trial will be presented in international meetings, and final trial results will be published in an open access, peer-reviewed journal.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the team of Prof. Ping Yin from the Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, School of Public Health, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, for the data monitoring and statistical support.

Footnotes

Contributors: RQ, MW and FZ obtained funding for the study. RQ, HZ and MW designed the study. XY, JiL, JuL, WZ, XC, DL, JhL, JdL, YL and RQ performed the operations. SP, TQ and TY drafted the manuscript. RQ, HZ and MW contributed to the critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content and approved the final version of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: The study was supported by grants from The National Natural Science Foundation of China (82073249, 81874205, 81773160), Tongji Hospital Clinical Research Flagship Program (2019CR203).

Disclaimer: The funder had no role in the design of the study, data collection, or writing this manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Consent obtained directly from patient(s)

References

- 1. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J Clin 2020;70:7–30. 10.3322/caac.21590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mizrahi JD, Surana R, Valle JW, et al. Pancreatic cancer. Lancet 2020;395:2008–20. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30974-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Are C, Dhir M, Ravipati L. History of pancreaticoduodenectomy: early misconceptions, initial milestones and the pioneers. HPB 2011;13:377–84. 10.1111/j.1477-2574.2011.00305.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zhang Y-H, Zhang C-W, Hu Z-M, et al. Pancreatic cancer: open or minimally invasive surgery? World J Gastroenterol 2016;22:7301–10. 10.3748/wjg.v22.i32.7301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ramirez PT, Frumovitz M, Pareja R, et al. Minimally invasive versus abdominal radical hysterectomy for cervical cancer. N Engl J Med 2018;379:1895–904. 10.1056/NEJMoa1806395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gagner M, Pomp A. Laparoscopic pylorus-preserving pancreatoduodenectomy. Surg Endosc 1994;8:408–10. 10.1007/BF00642443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Liu M, Ji S, Xu W, et al. Laparoscopic pancreaticoduodenectomy: are the best times coming? World J Surg Oncol 2019;17:81. 10.1186/s12957-019-1624-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Probst P, Hüttner FJ, Meydan Ömer, et al. Evidence map of pancreatic Surgery-A living systematic review with meta-analyses by the International Study group of pancreatic surgery (ISGPS). Surgery 2021;170:1517–24. 10.1016/j.surg.2021.04.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Palanivelu C, Senthilnathan P, Sabnis SC, et al. Randomized clinical trial of laparoscopic versus open pancreatoduodenectomy for periampullary tumours. Br J Surg 2017;104:1443–50. 10.1002/bjs.10662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Poves I, Burdío F, Morató O, et al. Comparison of perioperative outcomes between laparoscopic and open approach for pancreatoduodenectomy: the PADULAP randomized controlled trial. Ann Surg 2018;268:731–9. 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. van Hilst J, de Rooij T, Bosscha K, et al. Laparoscopic versus open pancreatoduodenectomy for pancreatic or periampullary tumours (LEOPARD-2): a multicentre, patient-blinded, randomised controlled phase 2/3 trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019;4:199–207. 10.1016/S2468-1253(19)30004-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wang M, Li D, Chen R, et al. Laparoscopic versus open pancreatoduodenectomy for pancreatic or periampullary tumours: a multicentre, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2021;6:438–47. 10.1016/S2468-1253(21)00054-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nickel F, Haney CM, Kowalewski KF, et al. Laparoscopic versus open pancreaticoduodenectomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Ann Surg 2020;271:54–66. 10.1097/SLA.0000000000003309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wang M, Peng B, Liu J, et al. Practice patterns and perioperative outcomes of laparoscopic pancreaticoduodenectomy in China: a retrospective multicenter analysis of 1029 patients. Ann Surg 2021;273:145–53. 10.1097/SLA.0000000000003190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chen K, Zhou Y, Jin W, et al. Laparoscopic pancreaticoduodenectomy versus open pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: oncologic outcomes and long-term survival. Surg Endosc 2020;34:1948–58. 10.1007/s00464-019-06968-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Moher D, Hopewell S, Schulz KF, et al. Consort 2010 explanation and elaboration: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ 2010;340:c869. 10.1136/bmj.c869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Asbun HJ, Conlon K, Fernandez-Cruz L, et al. When to perform a pancreatoduodenectomy in the absence of positive histology? a consensus statement by the International Study group of pancreatic surgery. Surgery 2014;155:887–92. 10.1016/j.surg.2013.12.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Clavien PA, Barkun J, de Oliveira ML, et al. The Clavien-Dindo classification of surgical complications: five-year experience. Ann Surg 2009;250:187–96. 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181b13ca2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bassi C, Marchegiani G, Dervenis C, et al. The 2016 update of the International Study Group (ISGPS) definition and grading of postoperative pancreatic fistula: 11 years after. Surgery 2017;161:584–91. 10.1016/j.surg.2016.11.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Koch M, Garden OJ, Padbury R, et al. Bile leakage after hepatobiliary and pancreatic surgery: a definition and grading of severity by the International Study group of liver surgery. Surgery 2011;149:680–8. 10.1016/j.surg.2010.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wente MN, Veit JA, Bassi C, et al. Postpancreatectomy hemorrhage (PPH): an international Study group of pancreatic surgery (ISGPS) definition. Surgery 2007;142:20–5. 10.1016/j.surg.2007.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wente MN, Bassi C, Dervenis C, et al. Delayed gastric emptying (DGE) after pancreatic surgery: a suggested definition by the International Study group of pancreatic surgery (ISGPS). Surgery 2007;142:761–8. 10.1016/j.surg.2007.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Besselink MG, van Rijssen LB, Bassi C, et al. Definition and classification of chyle leak after pancreatic operation: a consensus statement by the International Study Group on pancreatic surgery. Surgery 2017;161:365–72. 10.1016/j.surg.2016.06.058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Slankamenac K, Graf R, Barkun J, et al. The comprehensive complication index: a novel continuous scale to measure surgical morbidity. Ann Surg 2013;258:1–7. 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318296c732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kuesters S, Chikhladze S, Makowiec F, et al. Oncological outcome of laparoscopically assisted pancreatoduodenectomy for ductal adenocarcinoma in a retrospective cohort study. Int J Surg 2018;55:162–6. 10.1016/j.ijsu.2018.05.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chan A-W, Tetzlaff JM, Gøtzsche PC, et al. Spirit 2013 explanation and elaboration: guidance for protocols of clinical trials. BMJ 2013;346:e7586. 10.1136/bmj.e7586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zhang H, Feng Y, Zhao J, et al. Total laparoscopic pancreaticoduodenectomy versus open pancreaticoduodenectomy (TJDBPS01): study protocol for a multicentre, randomised controlled clinical trial. BMJ Open 2020;10:e033490. 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-033490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tempero MA, Malafa MP, Al-Hawary M, et al. Pancreatic adenocarcinoma, version 2.2021, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2021;19:439–57. 10.6004/jnccn.2021.0017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Common terminology criteria for adverse events (CTCAE) v5.0. Available: https://ctep.cancer.gov/protocoldevelopment/electronic_applications/docs/CTCAE_v5_Quick_Reference_8.5x11.pdf [Accessed 20 Jun 2020].

- 30. Gandaglia G, Ghani KR, Sood A, et al. Effect of minimally invasive surgery on the risk for surgical site infections: results from the National surgical quality improvement program (NSQIP) database. JAMA Surg 2014;149:1039–44. 10.1001/jamasurg.2014.292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Yu J, Huang C, Sun Y, et al. Effect of laparoscopic vs open distal gastrectomy on 3-year disease-free survival in patients with locally advanced gastric cancer: the CLASS-01 randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2019;321:1983–92. 10.1001/jama.2019.5359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kitano S, Inomata M, Mizusawa J, et al. Survival outcomes following laparoscopic versus open D3 dissection for stage II or III colon cancer (JCOG0404): a phase 3, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017;2:261–8. 10.1016/S2468-1253(16)30207-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Benson AB, D'Angelica MI, Abbott DE, et al. Hepatobiliary cancers, version 2.2021, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2021;19:541–65. 10.6004/jnccn.2021.0022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Benson AB, Venook AP, Al-Hawary MM, et al. Colon cancer, version 2.2021, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2021;19:329–59. 10.6004/jnccn.2021.0012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Benson AB, Venook AP, Al-Hawary MM, et al. Rectal cancer, version 2.2018, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2018;16:874–901. 10.6004/jnccn.2018.0061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Armstrong DK, Alvarez RD, Bakkum-Gamez JN, et al. Ovarian cancer, version 2.2020, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2021;19:191–226. 10.6004/jnccn.2021.0007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Koh W-J, Abu-Rustum NR, Bean S, et al. Cervical cancer, version 3.2019, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2019;17:64–84. 10.6004/jnccn.2019.0001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Neoptolemos JP, Kleeff J, Michl P, et al. Therapeutic developments in pancreatic cancer: current and future perspectives. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018;15:333–48. 10.1038/s41575-018-0005-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kang CM, Lee WJ. Is laparoscopic pancreaticoduodenectomy feasible for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma? Cancers 2020;12:3430. 10.3390/cancers12113430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Peng L, Zhou Z, Cao Z, et al. Long-Term oncological outcomes in laparoscopic versus open pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 2019;29:759–69. 10.1089/lap.2018.0683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Croome KP, Farnell MB, Que FG, et al. Total laparoscopic pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: oncologic advantages over open approaches? Ann Surg 2014;260:633-8; discussion 638-40. 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Stauffer JA, Coppola A, Villacreses D, et al. Laparoscopic versus open pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic adenocarcinoma: long-term results at a single institution. Surg Endosc 2017;31:2233–41. 10.1007/s00464-016-5222-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Zhou W, Jin W, Wang D, et al. Laparoscopic versus open pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: a propensity score matching analysis. Cancer Commun 2019;39:66. 10.1186/s40880-019-0410-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kwon J, Song KB, Park SY, et al. Comparison of minimally invasive versus open pancreatoduodenectomy for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: a propensity score matching analysis. Cancers 2020;12. 10.3390/cancers12040982. [Epub ahead of print: 15 04 2020]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. World Medical Association . World Medical association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA 2013;310:2191–4. 10.1001/jama.2013.281053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2021-057128supp001.pdf (76.9KB, pdf)