Abstract

Introduction

Literature suggests couple-based interventions that target quality of life and communication can lead to positive outcomes for patients with cancer and their partners. Nevertheless, to date, an intervention to address the needs of Latino families coping with advanced cancer has not been developed. Meta-analytic evidence suggests that culturally adapted evidenced-based intervention targeting a specific cultural group is four times more effective. Our goal is to culturally adapt a novel psychosocial intervention protocol entitled ‘Caregivers-Patients Support to Latinx coping advanced-cancer’ (CASA). We hypothesised that combine two evidence-based interventions and adapting them, we will sustain a sense of meaning and improving communication as patients approach the end of life among the patient–caregiver dyad.

Methods and analysis

To culturally adapt CASA, we will follow an innovative hybrid research framework that combines elements of an efficacy model and best practices from the ecological validity model, adaptation process model and intervention mapping. As a first step, we adapt a novel psychosocial intervention protocol entitled protocol entitled ‘Caregivers-Patients Support to Latinx coping advanced-cancer’ (CASA). The initial CASA protocol integrates two empirically based interventions, meaning-centred psychotherapy and couple communication skills training. This is an exploratory and prepilot study, and it is not necessary for a size calculation. However, based on recommendations for exploratory studies of this nature, a priori size of 114 is selected. We will receive CASA protocol feedback (phase 1b: refine) by conducting 114 questionnaires and 15 semistructured interviews with patients with advanced cancer and their caregivers. The primary outcomes of this study will be identifying the foundational information needed to further the develop the CASA (phase IIa: proof-of-concept and phase IIb: pilot study).

Ethics and dissemination

The Institutional Review Board of Ponce Research Institute approved the study protocol #1907017527A002. Results will be disseminated through peer-reviewed publications.

Keywords: mental health, oncology, cancer pain, palliative care

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study will allow the development of the patients–caregiver psychotherapy intervention to support Latinx patients and caregivers coping with advanced cancer.

The major strength of this study is its purpose to not solely translate a previously tested English language intervention, but also to adapt it culturally.

We will not measure our participants’ access to technology (ie, telephone, internet or computer), limiting our ability to assess some information on access to technology for the implementation phase.

Introduction

Patients with advanced cancer and informal caregivers

As the number of cancer diagnoses increases, informal caregivers (often family members) play an essential role in providing care throughout the cancer trajectory.1 2 Significant numbers of patients with advanced cancer and their families emphasise the need for increased attention to end-of-life care.3 Caregivers often assume the role without the necessary skills to help them address complex needs of a patient with cancer.4–8 Consequently, they can experience a substantial caregiving burden that negatively impacts family function (ie, communication, conflict and cohesion) and the patients’ physical, emotional and social well-being.6 9–12

Impact of cancer on family caregiver’s well-being

A substantial body of research has examined how caregiving processes are linked to the emotional health of family caregivers.13 Researchers continue to investigate how poor mental functioning in family caregiving among Latinx may affect patients’ outcomes; however, it is equally important to attend to the well-being of family caregivers. A consistent pattern of unmet need,14 15 and impact on mental functioning have been identified in recent year.16 Findings indicate that Latinx-caregivers ethnicity is associated with higher levels of clinically significant depression,16 and more caregiving demands are associated with higher levels of caregivers’ feelings of burden and psychological distress.17 Compounding this problem, Latinx contextual and cultural influences on caregivers present an unmet need for emotional support,18 especially when Latinx individuals are less likely to have adequate access to culturally congruent psychosocial interventions.19–30 Latinx cancer research had identified the psychosocial need of Latinx caregivers and described the importance of including psychosocial content related to communication and spirituality.31–33

Contribution of caregivers to patient’s well-being

The contribution of family caregivers to their patient’s well-being has been evident, and several indirect partner effects are also apparent in the literature. Specifically, for Latinx, both patients and caregivers had significant direct and indirect actor effects (through family conflict) of perceived stress on depression and anxiety. Caregivers’ stress was predictive of patients’ depression and anxiety through survivors’ increased perceptions of family conflict.34 A culturally centred intervention for Latinx patients should include a family-centred (partners and other family members) approach to determine the content and goals of care preferred in Latinx families coping with cancer.35–37

Latinx patients and caregiver dyadic

Latinx have a higher intensity (ie, hours per week and help with activities of daily living) of caregiving than non-Latinx whites and Asians.38 Our preliminary data show that 86% of Latinx patients with advanced cancer reported low family function, and those with low family cohesiveness had higher depression and anxiety levels. Several studies show that low family function negatively impacts the cancer illness trajectory (ie, adherence, depression, poor prognostic and stress).39–41 Patients with advanced cancer and their families experience significant distress in four domains: physical, psychological, social and spiritual.42–44 These domains are often summarised by the term ‘quality of life (QOL)’. QOL, spirituality and reduction of distress are essential goals of cancer care.45 A meta-analysis and systematic review found that Latinx patients with cancer show worse distress, depression and overall health-related quality of life (HRQOL) than other minority patients and whites.46 Similarly, Latinx patients report higher levels of burden, depression and physical health problems than patients of other ethnicities.47 48 Therefore, addressing family issues is crucial in the adjustment and well-being of Latinx with advanced cancer and their informal caregivers.

Cultural adaptation of evidence-based practice

Cultural adaptations of interventions for ethnic minority groups are feasible and acceptable.49–52 Meta-analytic evidence suggests that culturally adapted interventions targeting a specific cultural group (eg, Puerto Ricans as part of the Latinx community) are four times more effective than those provided to various cultural backgrounds, and twice as effective as English interventions if conducted in the participants’ native language (if other than English).49–52 The literature suggests that behavioural interventions must be culturally adapted for cultural groups by following the phases of information gathering, preliminary design, preliminary testing and final trial to reduce health disparities.52

The conceptual framework

Our conceptual framework, grounded in theory, developed by Dr. Breitbart, aims to target specific psychospiritual needs of patients with advanced cancer.53 Its primary goal is to help patients enhance a sense of meaning, peace and purpose as they approach end of life. The intervention focuses on assisting patients in identifying sources of meaning in their lives despite their diagnosis. In addition to its effectiveness with non-Latino whites, Dr. Costas-Muñiz demonstrated the acceptability and feasibility of meaning-centred psychotherapy (MCP) for Latinx patients with advanced cancer.31 32 Preliminary findings suggested that Latinx with advanced cancer identified family and communication issues as crucial in adjusting to their cancer diagnosis and well-being.31 32 Further, we identified evidence of communication skill training that indicated that communication skills for couples improve family communication dynamics, especially among Latinx families,54 and there are data on the effectiveness of couple communication skills traing (CCST) in Caucasian couples; however, literature is absent about effectivity in Latinx coping with advanced cancer.50 These findings indicate the need to explore the integration of CCST (components) for patients dealing with advanced cancer to an MCP.

Objectives

The purpose of this study is to culturally adapt and integrate (1) MCP and (2) CCST a novel psychosocial intervention protocol entitled ‘Caregivers-Patients Support to Latinx coping advanced-cancer’ (CASA). The CASA intervention aims to improve the QOL and spiritual well-being of patients with advanced cancer and their informal caregivers. This paper describes the conceptual framework used for the cultural adaptation process, initial phases and future plans.

Methods and analysis

This significant milestone for forward movement lead to the initial CASA protocol integration of two empirically based interventions, MCP and CCST, with the goals of (1) helping patients and caregivers sustain or enhance a sense of meaning and (2) improving communication to improve health-related outcomes. We hypothesised that helping patients and caregivers sustain a sense of meaning and improving communication as patients approach the end of life among the patient–caregiver dyad will improve spirituality and communication and, in turn, improve QOL. This is an exploratory study and prepilot study, and its treatment components including (MCP and CCST) will be adapting and forward movement by the findings and grounding in theory. For the pilot phase, we will easily translate and adapt the intervention for Latinx sample living in the USA by conducting a pilot study in Puerto Rico and New York; see phase IIb: pilot study.

The unifying theoretical framework of the culturally adapted evidence-based practice,55–58 ecological validity model (EVM),56 developed by Dr. Guillermo Bernal, the cultural adaptation process model (CAPM),57 and intervention mapping,59 provide viable approaches to treating ethnic minorities and culturally diverse groups. According to EVM, to adapt an intervention for a new cultural group, seven dimensions need to be addressed: language, context, persons, metaphors, concepts, goals and methods.55 CAPM is a complementary process model to EVM and prescribes four phases for the adaptation process: formative, adaptation iterations, intervention and measurement adaptation.55 Cancer contextual model of HRQOL (eg, spiritual well-being, depression, anxiety, hopelessness, functional assessment of cancer therapy, family relationship index, burden, fatalism, religiosity, distress and patient’s needs-semistructured interview) are outlined to specify individual, cultural and contextual influences (ie, dyadic relationships and communication with partners) as essential determinants of QOL.58 Drawing from social cognitive (ie, CCST) and existential theory (ie, meaning-centred therapy), the ‘Caregivers-Patients Support to Latinx coping advanced-cancer’ (CASA) intervention is designed to increase the spiritual well-being and self-efficacy in communication between patients with advanced cancer and their informal caregivers.59–64

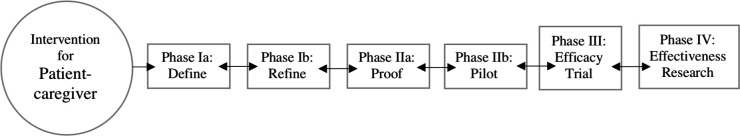

To identify the foundational information necessary to culturally adapt and integrate MCP and CCST to adapt de CASA intervention for Latinx patients and their informal caregivers, we will use a four-phase approach guided by the ORBIT model to the cultural adaptation process: (1a) define, (1b) refine, (2 a) proof-of-concept, (2b) pilot, (3) efficacy trial and (4) effectiveness research. The ORBIT model for behavioural treatment development model provides a progressive, clinically relevant approach to increasing the number of evidence-based behavioural treatments available to prevent and treat chronic diseases.65 The ORBIT model includes a flexible and iterative progressive process, prespecified clinically significant milestones for forward movement, and return to an earlier phase for refinement in the event of suboptimal results; see figure 1.65

Figure 1.

Summary of the ORBIT model,65 applying for the development of the Caregivers-Patients Support to Latinx coping advanced-cancer for forward movement and a return to an earlier phase for refinement in event of other findings.

Phase Ia: define intervention components

The selection of intervention components was defined by the cultural expert (NTB) and a group of mentors (EMC, MJS, RCM, GB and LP) after careful review of the intervention’s selected components. The rationale for selecting the MCP and CCST approaches, out of numerous other psychotherapeutic approaches, is that research indicated that communication skills for couples improves family communication dynamics, especially among Latinx families and are there prior data of the effectiveness of MCP as well as Latinx prior indications of need for meaning making such as the literature around spirituality.59–64 Specifically, there is only one intervention in the adaptation process for Latinx dealing with advanced cancer, the individual MCP.31 32 We decided to optimise and further the development of the adapted MCP for Latinx by incorporating the patient’s reported needs in training for communication skills and the inclusion of other family members. By using the CCST approach, we enhanced the MCP session by adding taught coping skills (eg, how to communicate and listen) as well as how to increase their self-efficacy (ie, confidence) for sharing through behavioural practice, goal setting and monitoring progress.63 64 The CCST approach was adapted for non-spousal patients’ caregivers by eliminating spousal terms (eg, taking care of your partner–spouse) and changing it to general caregiving terms (eg, taking care of your significant other). Overview table 1 presents the MCP and CCST components that will be cultural and linguistic adapted and integrated for the CASA adapted protocol.

Table 1.

Caregivers-Patients Support to Latinx coping advanced-cancer

| MCP components | CCST components | Cultural adaptation | Linguistic adaptation | |

| Treatment goal | X | X | X | X |

| Communication skill: speaker | X | X | X | |

| Communication skill: listen | X | X | X | |

| The will to meaning | X | X | ||

| Freedom of will | X | X | ||

| Life has meaning | X | X | ||

| Homework: encountering life’s limitations | X | X | ||

| Identity | X | X | ||

| Experiential sources of meaning | X | X | ||

| Creative sources of meaning | X | X | ||

| Homework: share your legacy~tell your story and legacy project | X | X | ||

| Homework: connecting with life | X | X | ||

| Four session | X | X | ||

| Other to related to end-of-life care | X | X | X |

CCST, couple communication skills traing; MCP, meaning-centred psychotherapy.

The cultural and linguistic adaptation seven dimensions need to be addressed: language, context, persons, metaphors, concepts, goals and methods.56 Table 2 presents how we addressed seven dimension (1) language: translate the CCST into Spanish and eliminating spousal terms, (2) person: assessing other possible ends of life themes (ie, different ends of life themes), (3) goals: access the integration of communication skills training and MCP goals, (4) metaphors: we will include culturally consonants stories by adapting the communication skills training and meaning-centred components, (5) concepts: integration of culturally consonants MCP concepts and important end-of-life care topics, (6) methods: use of visual aids and simple definitions to describe the content and (7) context: integration of Latino family (caregivers–patients) values, traditions and uniqueness in communication and meaning.

Table 2.

Ecological validity model

| Adaptations | ||

| Language | Culturally appropriate and culturally syntonic | Translate the CCST into Spanish and we also adapted for non-spousal patients’ caregivers by eliminating spousal terms (eg, taking care of your partner–spouse) and changing it to general caregiving terms (eg, taking care of your significant other). |

| Persons | Role of similarities and differences | Assessing other possible ends of life themes (ie, different ends of life themes) |

| Goals | Supportive of adaptive values of culture | Access the integration of Communication skills training and meaning-centred psychotherapy goals. |

| Metaphors | Culturally consonant sayings and stories | We will include culturally consonants stories by adapting the communication skills training and meaning-centred components |

| Concepts | Concepts consonant with culture and context | Integration of culturally consonants meaning-centred psychotherapy concepts and important end-of-life care topics |

| Methods | Strategies consonant with patients’ culture | Use of visual aids and simple definitions to describe the content |

| Context | Consideration of contextual factors | Integration of Latino family (caregivers–patients) values, traditions and uniqueness in communication and meaning |

CCST, couple communication skills traing.

Phase Ib: refine intervention components

With the CASA protocol, we develop an acceptability and feasibility questionnaire and semi-interview of the intervention. The recruitment and administration of the questionnaire (quantitative phase) and the semistructured interviews (qualitative phase) started in September 2020 and are ongoing until recruitment goals are met. Using the Ecological Validity Framework, the cultural expert (NTB) developed a questionnaire and semistructured interview to administer to patients and their informal caregivers. The questionnaire (quantitative phase) and the semistructured interviews (qualitative phase) were designed to gather information from patients and informal caregivers about integrating Latinx families and cultural values (ie, spirituality, familism and fatalism) to the CASA manual. The intervention targets include: patient and caregiver psychosocial needs, caregiving burden and family function (ie, communication, conflict and cohesion)63 64; see table 1.

COVID-19 recruitment phase Ib

Due to social distancing measures during the COVID-19 pandemic, an updated recruitment plan was approved to facilitate ongoing activities and testing. This plan includes (1) using open-access media (ie, Facebook and Ponce Health Science University official webpages) to recruit participants; (2) including possession of a smartphone, tablet or computer/laptop as an eligibility criterion; and (3) providing the option of conducting informed consent, questionnaire and semistructured interview procedures during telehealth visits, ensuring they take place in a private location. Depending on the participant’s access, one of the following platforms will be used: VidyoConnect, Zoom, VSee or Doxy.me.

Sample quantitative phase Ib

Participants will be recruited through the Programa de Apoyo Psicosocial Integrado al Cuidado Oncológico (PAPSI—Integrated Psychosocial Support Program for Cancer Care), a psychosocial support programme integrated into oncology care at Ponce Health Sciences University. Patients with advanced cancer who completed PAPSI’s routine distress screening measure will be screened to assess whether they meet the following inclusion criteria: (1) diagnosed with stage III or IV solid tumours, (2) 21 years or older, (3) self-report being Latinx or Hispanic and (4) fluent in Spanish. With the patient’s permission, their informal caregiver will be invited to participate if they meet the following inclusion criteria: (1) informal caregiver of a patient recruited to the study and identified by the patient as the person he/she gets the most support, (2) 21 years or older, (3) self-report being Latinx or Hispanic and (4) fluent in Spanish.

One hundred and forty patients and their informal caregivers who meet the inclusion criteria will be recruited and participate in the process of informed consent when they agree to enrol in the study. A priori sample size of 114 is selected based on recommendations for exploratory studies of this nature.66 67 Following informed consent, participants will be assigned a subject number. The cultural expert (NTB) will administer the cross-sectional questionnaire (table 3) to assess the acceptability of the goals, concepts of MCP and communication skills training, and the feasibility of the proposed intervention’s goals and therapeutic methods. Participants will complete assessments,68–88 measuring spiritual well-being, depression, anxiety, hopelessness, QOL, family relationship, burden, fatalism, religiosity and distress. Additionally, the survey includes general demographic information (ie, age, education and gender) of the patient and their informal caregiver. The cultural expert (NTB) will administer the questionnaire in an interview-style to accommodate patients and their informal caregivers with limited education and/or literacy. After completing the questionnaire, patients and their informal caregivers will be received US$15 for their study participation.

Table 3.

Description of study scales

| Spiritual well-being scale | The FACIT Spiritual Well-Being Scale is a brief self-report measure designed to assess an individual’s spiritual well-being with two sub-scales: spirituality and meaning/peace,68 69 |

| Depression and anxiety | The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS),70–72 |

| Hopelessness | The Beck Hopelessness Scale (BHS) comprises 20 true/false questions that assess the degree of hopelessness,73 74 |

| Quality of life | The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General (FACT-G) will assess the participants' quality of life,75 |

| Family relationship Family communication |

Family Relationship Index will measure cohesiveness, conflict, and expressiveness among family members,76 Holding Back subscale (HBS) of the Emotional Disclosure Scale is a 10-item measure assessing the degree to which individuals hold back from talking with their partner/caregiver about cancer-related concerns,77–80 |

| Burden | Zarit Burden Interview (ZBI) is a 22 item, 5-point Likert scale (never=0, nearly always=4) used widely to assess caregiver burden81–83 |

| Fatalism | Fatalism will be measured with the Mental Adjustment to Cancer Scale, which assesses cognitive responses to cancer in five dimensions, including fatalism,84 |

| Religiosity | The Age Universal I/E scale will measure intrinsic and extrinsic religiosity,85 86 |

| Distress | NCCN Distress Thermometer and Problem List is a rapid screening tool for assessing psychological distress in people affected by cancer,87 88 |

Sample qualitative phase Ib

Patients (n=15) and their informal caregivers (n=15) who (1) completed the questionnaire package, and (2) scored≥4 in the distress thermometer will be invited to participate in the qualitative phase. A priori sample size of 15 is selected based on recommendations for qualitative studies of this nature.66–70 Scores≥4 suggest significant distress and the need for further psychological evaluation. Among those meeting inclusion criteria, the trained professional (interviewer) will discuss informed consent. The interviewer will be blinded to the quantitative information before the one-session, in-depth semistructured interview, which will be conducted in Spanish and last approximately 1 hour. The interviewer will have an interview guide with the flexibility to ask off-guided questions, which is divided into four sections: (1) exploratory questions regarding participants’ understanding of the MCP concepts, (2) exploratory questions regarding the acceptability and feasibility of the family-based intervention, (3) dyad’s advanced cancer experience, strategies used to cope and caregiving burden and (4) family function (ie, communication, conflict and cohesion). When necessary, the interviewer will use follow-up probing questions to elicit patients’ and informal caregivers' full narratives. The interview will be digitally audio-recorded. After the semistructured interviews, participants (patient and the informal caregiver) will receive a US$30 stipend for their participation.

Phase IIa: proof-of-concept

Phase IIa is planned for the future after phase Ib is completed (questionnaire and semistructured interviews). The formative findings from phase Ib will provide the necessary information to adapt the CASA intervention and further develop the fixed CASA protocol, following the Ecological Validity Framework. With the fixed CASA protocol, we will conduct a prepilot feasibility and acceptability study of using the ORBIT: phase IIa. The hypothesis is that CASA is feasible and acceptable, evidenced by reaching high overall retention (>75%), high satisfaction (>75%) and high overall acceptability (>75%) among patients and families.

Sample phase IIa

Using a single-arm feasibility design, 30 dyads with patients with stage III and IV solid tumour, distressed (distress thermometer>4) will be enrolled from an oncology clinic in the south area of Puerto Rico. A priori sample size of 30 is selected based on recommendations for prepilot studies.66 67 The manualised protocol will be delivered across four 45–60 min videoconference sessions by a clinical psychologist. The data will be recorded with informed consent from participants. Data will be transcribed, coded and analysed for themes and subcategories, paying attention to challenging or incomprehensible material and meaning making and communication skills training approaches given by participants. Participants will receive incentives after each session and assessments.

Procedure phase IIa

CASA consists of four—45–60 min—family sessions. The four sessions are expected to be delivered every week or every 2 weeks over a span of 4–8 weeks. Sessions will be recorded to conduct fidelity checks. The Principal Investigator, who is a licensed clinical psychologist with extensive clinical training in MCP and CCST, practice delivering MCP and CCST with patients with cancer, and research experience adapting CASA, will conduct the sessions. Patient-reported outcomes will be assessed at baseline and post intervention. Participants will be invited to participate in in-depth exit interviews following completion of CASA intervention. The data will be recorded with informed consent from the participants. Data will be transcribed, coded and analysed for themes and subcategories, paying attention to challenging or incomprehensible material and meaning making and communication skills training approaches given by participants. Participants will receive incentives after each session and assessments.

Phase IIb: pilot study

Phase IIb is planned for the future once phase IIa is completed. The prepilot (ORBIT: phase IIb) will provide the necessary information to assess the preliminary efficacy of the CASA versus usual care (behavioural placebo) with quality-of-life and patient-reported outcomes (spiritual well-being and self-efficacy) in 100 Latinx families. We will used usual care that include usual psychotherapy intervention as a comparison condition to measure the effect of the adapted intervention. The hypothesis is that those assigned to CASA will report better outcomes than those assigned to the attention control condition at post intervention.

Sample phase IIb

One hundred Latinx families, from Puerto Rico and New York, will be randomised placed in a two-group pilot design with pretest and repeated post-test measures used to accomplish the study aims. Patients with stage III and IV (N=100) and their caregivers are randomised in one of two intervention conditions with equal allocation: ‘Caregivers-Patients Support to Latinx coping advanced-cancer’ (CASA) or usual care. A priori sample size of 100 is selected based on recommendations for pilot studies.66 67 Randomisation is stratified by age at diagnosis and recruitment site. Both interventions are manualised, of equivalent duration, and delivered by a trained counsellor to the couples jointly over videoconference sessions. Web-based self-report outcome measures are administered to participants at baseline and post intervention.

Procedure phase IIb

CASA consists of four 45–60 min family sessions. The four sessions are expected to be delivered every week or every 2 weeks over a span of 4–8 weeks. Sessions will be recorded to conduct fidelity checks. The PI who is a licensed clinical psychologist with extensive clinical training in MCP and CCST, practice delivering MCP and CCST with patients with cancer, and research experience adapting CASA, will conduct the sessions in the USA or will supervise a trained doctoral level clinical psychologist trainee. In New York, Dr. Rosario Costas (consultant), who is a clinical psychologist trained in MCP and also the principal investigator for the R21 Meaning Centered Psychotherapy-for Latinos study, will conduct the sessions or will supervise a doctoral level clinical psychologist trainee on the conducting of CASA. If a doctoral level clinical psychology trainee is involved in delivering the intervention, he/she will be first trained on conducting CASA and will receive weekly supervision from Dr. Costas, or from Dr. Torres if they are practicing in Puerto Rico, but all trainees will receive supervision from Dr. Torres. Patient-reported outcomes will be assessed at baseline and post intervention. Participants will be invited to participate in in-depth exit interviews following completion of CASA intervention. The data will be recorded with informed consent from the participants. Data will be transcribed, coded and analysed for themes and subcategories, paying attention to challenging or incomprehensible material and meaning making and communication skills training approaches given by participants. Participants will receive incentives after each session and assessments.

Quantitative analysis phase Ib

Descriptive statistics will be conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics V.21 to examine survey responses. The predyadic analyses occur in three steps: (1) bivariate correlations to calculate results between depression, anxiety, meaning, spirituality, hopelessness, QOL and family function, (2) eight bivariate regression models to assess the predictive power of each predictor variable (meaning and spirituality) on each of the four outcomes: hopelessness, QOL, anxiety and depression, (3) multilevel models to analyse data at the dyad level to control for interdependencies.67 The dyadic analysis will be conducted through multivariate outcome models to estimate a possible score for each member of the couple (ie, one for the patient and one for the informal caregiver). It will be controlled for the dependent nature of couple-level data and allowed for examination of both actor and cross-partner effects.67

Quantitative analysis phase IIa

Feasibility and acceptability will be assessed through accrual, session/assessment completion, intervention satisfaction and coping skills usage. Participants completed validated measures of primary outcomes (ie, spiritual well-being and self-efficacy) and acceptability questionnaire at baseline, and post intervention.

Quantitative analysis phase IIb

The primary analysis will examine whether, relative to the usual care intervention, the CASA intervention leads to greater increases in patient and caregivers’ spiritual well-being and self-efficacy in all two post-treatment assessments in a mixed-effects regression model. Pretreatment spiritual well-being and self-efficacy scores and time (categorical) will be included as covariates. Intervention by time interactions will test the intervention effect at each follow-up time. Subject-specific random intercepts will account for within-subject variability. Intervention effects on patient spiritual well-being and self-efficacy at each follow-up are tested using F tests of combined main and interaction effects. Descriptive statistics will be conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics V.21 to examine survey responses. The predyadic and postdyadic analyses occur in three steps: (1) bivariate correlations to calculate results between meaning, spirituality, hopelessness, QOL and family function, (2) eight bivariate regression models to assess the predictive power of each predictor variable (meaning and spirituality) on each of the four outcomes: hopelessness, QOL, anxiety and depression, (3) multilevel models to analyse data at the dyad level to control for interdependencies.67 The dyadic analysis will be conducted through multivariate outcome models to estimate a possible score for each member of the couple (ie, one for the patient and one for the informal caregiver). It will be controlled for the dependent nature of couple-level data and allowed for examination of both actor and cross-partner effects.67

Qualitative analysis phase Ib, IIa and IIb

Data analysis will begin with verbatim transcripts of the 30-digital audio-recorded interviews and imported into Atlas.ti (V.8.1.3; Atlas.ti Scientific Software Development, Berlin, Germany, www.atlasti.com).89 The team will follow a published qualitative data preparation and transcription protocol to ensure the transcriptions’ accuracy and fidelity.90–93 Observational notes taken by the interviewer will be typed and attached to the transcription documents. During the transcription, all data will be deidentified by replacing names with aliases to ensure anonymity.

Atlas.ti will be used to analyse the transcription of semistructured interviews. Two triangulated methods will be used to improve qualitative accuracy and validity: methods and analyst triangulation.91–95 Method triangulation will be achieved by determining the consistency of the data generated by both the survey and the semistructured interviews. Analyst triangulation will be attained using multiple analysts (raters) to review and evaluate the qualitative data. Once transcribed, the text will be analysed in two steps: (1) inductive followed by (2) deductive content analysis. Each step has three phases: preparation, organising and reporting.96–99 Two bilingual raters will conduct the content analysis. The analyses, integration and interpretation will be in Spanish.

Inductive content analysis will examine how families (patients with advanced cancer and their informal caregivers) define CASA and communication skills training concepts. During the preparation phase, raters will familiarise themselves with the text. The data will be organised through open coding, creating categories, abstractions and identifying the concepts’ boundaries for inductive analysis. Categories will be generated from open coding and grouped under higher-order headings. Descriptions using content-characteristic words will be created for the abstraction. The data will be reviewed for deductive content analysis using a structured categorisation matrix based on the MCP and communication skill model. All data will be reviewed for content and coded for correspondence, exemplifying the categories’ categorisation matrix.

Integration phase

In cultural adaptation, the source text is rewritten in the target language to convey the concepts and achieve the aims of the source text, while accounting for both language and cultural considerations.100 The cultural adaptation not only renders the text of written materials into another language but also infuses culturally relevant context and themes.100–102 The cultural expert (NTB), group of mentors (EMC, MJS, RCM, GB and LP), and collaborators (CZ, MC and WB) will conduct the integration of the quantitative and qualitative findings to develop the CASA fixed protocol (table 1). The text will be independently reviewed, followed by ‘consensus meetings’ to discuss every session of the intervention, provide feedback and discuss further modifications until a consensus is reached. Dr. Guillermo Bernal will then review the text to ensure the adaptation considers the dimensions of the EVM. The adaptations will be highlighted, and comments will be kept in the margin. Fidelity of ‘Caregivers-Patients Support to Latinx coping advanced-cancer’ concepts, goals and theoretical model will be preserved during the adaptation process to ensure language, metaphor, strategy, cultural context and value acceptability by Latinx families.

As shown with the transcreation of CASA intervention for Latinx, we will include information of Latinx living in Puerto Rico and New York, the adaptation plan for Latinx families will also include content modification, family congruence through metaphors and assignments, and cultural adaptation notes with findings from the cultural adaptation process guidelines about the delivery of the intervention to the dyad.

Summary

Once the fixed protocol of CASA is acceptable, feasible and effective, we will finalise the development process with an efficacy trial (ORBIT: phase III) and later effectiveness research trial (ORBIT: phase IV). This process will facilitate the development of culturally sensitive intervention and mitigate the cost of developing effective and durable behavioural treatment. All the identified phases currently bring the needed elements to go from ideas to efficacy trial with a well-defined pathway for doing it. Specifically, the proposed behavioural intervention framework pushes the identified need to sight on the chain of evidence needed to support the progressive programme of intervention development. Finally, the recognised framework is flexible in both the design and methodologies for treatment development, which facilitates development.65

Strengths and weaknesses/limitations of the study

The first limitation is that the qualitative interviews are the main source of information for the adaptation. Thus, we will include observation of sessions in the next phases of adaptation process (phase IIa: proof-of-concept and phase IIb: pilot study). Second, patients were predominantly recruited from Puerto Rico. Thus, the results may not generalise to all Latinx, and future studies will include samples from different geographical locations. Third, the selection of patients was not homogeneous in terms of diagnosis and stages, and patients with stages III and IV cancer will be invited to participate. The cancer experience of patients and caregivers at different disease stages with different prognoses could vary significantly. In future studies, analyses should be stratified by stage and prognosis. The final identified limitation is the access to technology. Thus, we will include the possibility of conducting the questionnaire and intervention in person.

Public involvement statement

The public, specifically Latinx patients with advanced cancer and their informal caregivers, are at the core of the implementation plan. The study’s objective is to develop the first psychosocial patient–caregiver intervention that supports Latinx patients with advanced cancer and their informal caregivers to cope with cancer. The study design mentioned above will constantly include the consultation of patients’ and their informal caregivers’ perceptions, experiences and opinions to refine a successful final version of ‘Caregivers-Patients Support to Latinx coping advanced-cancer’ (CASA). The intent is to involve the patients and their informal caregivers (the public), who will be the target user in the development and cultural adaptation of the patient–caregiver psychological intervention (ORBIT: phase IIa: proof-of-concept and phase IIb: pilot study). Further, the proposed project will directly (1) impact the Latinx community, (2) contribute to the development of culturally adapted psychosocial interventions, (3) be used in the healthcare field and (4) reduce disparities in access to psychosocial interventions for Latinx patients with advanced cancer.

Ethics and dissemination

This project is the first development of a culturally and linguistically adapted intervention for Latinx families coping with advanced cancer. The results of this adaptation plan will guide the specific dyadic intervention for patients with advanced cancer and caregivers. It will advance the field of cultural adaptation of psychosocial interventions in the medical field to reduce health inequalities. Furthermore, it will result in peer-reviewed publications, conference presentations and reports. The information will also be shared with non-academic community members involved in outreach activities; that is, ‘Hablemos de Cáncer’, El Puente (The Bridge), newsletters and social media; that is, ‘Yo Puedo’, of the Support Group of American Cancer Society in Puerto Rico.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: Study conception and design: NTB, EMC, RCM, LP, MJS, WB and GB. Acquisition of data: NTB, MC and RCM. Analysis and interpretation of data: NTB and RCM. Drafting of manuscript: all authors. Critical revision: NTB, EMC, CZ and RCM.

Funding: We would like to acknowledge the contribution (2U54CA163071 and 2U54CA163068) and the National Institute of Minority Health and Health Disparities (5G12MD007579, 5R25MD007607, R21MD013674 and 5U54MS007579-35); National Cancer Institute R21CA180831-02 (Cultural Adaptation of Meaning-Centered Psychotherapy for Latinos), 1R25CA190169-01A1(Meaning-Centered Psychotherapy Training for Cancer Care Providers), 1R01CA229425-0A1 (Couple Communication Skills Training for Advanced Cancer Patients), 3R01CA201179-04S1 (Couple Communication in Cancer: A Multi-Method Examination), 5K07CA207580-04 (Culturally Competent Communication Intervention to Improve Latinos’ Engagement in Advanced Care Planning), 5R21CA224874-02 (A communication-based intervention for advanced cancer patient-caregivers dyads to increase engagement in advance care planning and reduce caregivers burden), 5K08CA234397 (Adaptation and Pilot Feasibility of a Psychotherapy Intervention for Latinos with Advanced Cancer); and the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center grant (P30CA008748). Supported in part by 133798-PF-19-120-01-CPPB from the American Cancer Society.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Consent obtained directly from patient(s)

References

- 1.Northouse L, Williams A-L, Given B, et al. Psychosocial care for family caregivers of patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:1227–34. 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.5798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blum K, Sherman DW. Understanding the experience of caregivers: a focus on transitions. InSeminars in oncology nursing 2010 nov 1 (Vol. 26, No. 4, pp. 243-258). WB Saunders. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Peppercorn JM, Smith TJ, Helft PR, et al. American Society of clinical oncology statement: toward individualized care for patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol 2011;29:755–60. 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.1744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Given B, Wyatt G, Given C, et al. Burden and depression among caregivers of patients with cancer at the end-of-life. InOncology nursing forum 2004 nov 16 (Vol. 31, no. 6, P. 1105). NIH public access. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Reinhard SC, Given B, Petlick NH. Supporting family caregivers in providing care. patient safety and quality: an evidence-based Handbook for nurses, 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harding R, Higginson IJ. What is the best way to help caregivers in cancer and palliative care? A systematic literature review of interventions and their effectiveness. Palliat Med 2003;17:63–74. 10.1191/0269216303pm667oa [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McCorkle R, Siefert ML, Dowd MF, et al. Effects of advanced practice nursing on patient and spouse depressive symptoms, sexual function, and marital interaction after radical prostatectomy. Urol Nurs 2007;27:65–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Northouse LL, Mood D, Templin T, et al. Couples' patterns of adjustment to colon cancer. Soc Sci Med 2000;50:271–84. 10.1016/S0277-9536(99)00281-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McCorkle R, Siefert ML, Dowd MFE, et al. Effects of advanced practice nursing on patient and spouse depressive symptoms, sexual function, and marital interaction after radical prostatectomy. Urol Nurs 2007;27:65–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Northouse LL, Mood D, Templin T, et al. Couples' patterns of adjustment to colon cancer. Soc Sci Med 2000;50:271–84. 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00281-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lau DT, Berman R, Halpern L, et al. Exploring factors that influence informal caregiving in medication management for home hospice patients. J Palliat Med 2010;13:1085–90. 10.1089/jpm.2010.0082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lim SM, Kim HC, Lee S. Psychosocial impact of cancer patients on their family members. Cancer research and treatment: official journal of Korean Cancer Association 2013;45:226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Geng H-M, Chuang D-M, Yang F, et al. Prevalence and determinants of depression in caregivers of cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine 2018;97:e11863. 10.1097/MD.0000000000011863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim Y, Carver CS. Unmet needs of family cancer caregivers predict quality of life in long-term cancer survivorship. J Cancer Surviv 2019;13:749–58. 10.1007/s11764-019-00794-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim Y, Carver CS, Ting A, et al. Passages of cancer caregivers' unmet needs across 8 years. Cancer 2020;126:4593–601. 10.1002/cncr.33053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Williams A-L, Tisch AJH, Dixon J, et al. Factors associated with depressive symptoms in cancer family caregivers of patients receiving chemotherapy. Support Care Cancer 2013;21:2387–94. 10.1007/s00520-013-1802-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Magaña SM, Ramírez García JI, Hernández MG, et al. Psychological distress among Latino family caregivers of adults with schizophrenia: the roles of burden and stigma. Psychiatr Serv 2007;58:378–84. 10.1176/ps.2007.58.3.378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Badger TA, Sikorskii A, Segrin C. Contextual and cultural influences on caregivers of Hispanic cancer survivors. InSeminars in oncology nursing 2019 AUG 1 (Vol. 35, no. 4, pp. 359-362). WB Saunders. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Luckett T, Goldstein D, Butow PN, et al. Psychological morbidity and quality of life of ethnic minority patients with cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol 2011;12:1240–8. 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70212-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Karapetyan L, Dawani O, Laird-Fick HS. End-Of-Life care for an undocumented Mexican immigrant: resident perspective. J Palliat Care 2018;33:63–4. 10.1177/0825859718759818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnson KS, Kuchibhatla M, Payne R, et al. Race and residence: intercounty variation in black-white differences in hospice use. J Pain Symptom Manage 2013;46:681–90. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2012.12.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carr D. Racial differences in end-of-life planning: why don't Blacks and Latinos prepare for the inevitable? Omega 2011;63:1–20. 10.2190/OM.63.1.a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carr D. Racial and ethnic differences in advance care planning: identifying subgroup patterns and obstacles. J Aging Health 2012;24:923–47. 10.1177/0898264312449185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith AK, McCarthy EP, Paulk E, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in advance care planning among patients with cancer: impact of terminal illness acknowledgment, religiousness, and treatment preferences. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:4131–7. 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.8452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Loggers ET, Maciejewski PK, Jimenez R, et al. Predictors of intensive end-of-life and hospice care in Latino and white advanced cancer patients. J Palliat Med 2013;16:1249–54. 10.1089/jpm.2013.0164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fischer SM, Sauaia A, Min S-J, et al. Advance Directive discussions: lost in translation or lost opportunities? J Palliat Med 2012;15:86–92. 10.1089/jpm.2011.0328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jiménez J, Ramos A, Ramos-Rivera FE, et al. Community engagement for identifying cancer education needs in Puerto Rico. J Cancer Educ 2018;33:12–20. 10.1007/s13187-016-1111-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Castro-Figueroa EM, Torres-Blasco N, Rosal MC, et al. Preferences, use of and satisfaction with mental health services among a sample of Puerto Rican cancer patients. PLoS One 2019;14:e0216127. 10.1371/journal.pone.0216127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Castro EM, Jiménez JC, Quinn G, et al. Identifying clinical and support service resources and network practices for cancer patients and survivors in southern Puerto Rico. Support Care Cancer 2015;23:967–75. 10.1007/s00520-014-2451-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Castro-Figueroa EM, Torres-Blasco N, Rosal MC, et al. Brief report: Hispanic patients' trajectory of cancer symptom burden, depression, anxiety, and quality of life. Nurs Rep 2021;11:475–83. 10.3390/nursrep11020044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Costas-Muñiz R, Torres-Blasco N, Castro-Figueroa EM, et al. Meaning-Centered psychotherapy for Latino patients with advanced cancer: cultural adaptation process. J Palliat Med 2020;23:489–97. 10.1089/jpm.2019.0423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Torres-Blasco N, Castro E, Crespo-Martín I, et al. Comprehension and acceptance of the Meaning-Centered psychotherapy with a Puerto Rican patient diagnosed with advanced cancer: a case study. Palliat Support Care 2020;18:103–9. 10.1017/S1478951519000567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ting A, Lucette A, Carver CS, et al. Preloss spirituality predicts postloss distress of bereaved cancer caregivers. Ann Behav Med 2019;53:150–7. 10.1093/abm/kay024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Segrin C, Badger TA, Sikorskii A. A dyadic analysis of loneliness and health-related quality of life in Latinas with breast cancer and their informal caregivers. J Psychosoc Oncol 2019;37:213–27. 10.1080/07347332.2018.1520778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shen MJ, Gonzalez C, Leach B, et al. An examination of Latino advanced cancer patients' and their informal caregivers' preferences for communication about advance care planning: a qualitative study. Palliat Support Care 2020;18:277–84. 10.1017/S1478951519000890 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Badger TA, Segrin C, Sikorskii A, et al. Randomized controlled trial of supportive care interventions to manage psychological distress and symptoms in Latinas with breast cancer and their informal caregivers. Psychol Health 2020;35:87–106. 10.1080/08870446.2019.1626395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kwak J, Haley WE. Current research findings on end-of-life decision making among racially or ethnically diverse groups. Gerontologist 2005;45:634–41. 10.1093/geront/45.5.634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.AARP . Caregivers in US. research report, 2020. Available: https://www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/ppi/2020/05/full-report-caregiving-in-the-united-states.doi.10.26419-2Fppi.00103.001.pdf

- 39.Kim Y, Given BA. Quality of life of family caregivers of cancer survivors: across the trajectory of the illness. Cancer 2008;112:2556–68. 10.1002/cncr.23449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Given BA, Given CW, Kozachik S. Family support in advanced cancer. CA Cancer J Clin 2001;51:213–31. 10.3322/canjclin.51.4.213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lambert S, Girgis A, Descallar J, et al. Trajectories of mental and physical functioning among spouse caregivers of cancer survivors over the first five years following the diagnosis. Patient Educ Couns 2017;100:1213–21. 10.1016/j.pec.2016.12.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Portenoy RK, Thaler HT, Kornblith AB, et al. The Memorial symptom assessment scale: an instrument for the evaluation of symptom prevalence, characteristics and distress. Eur J Cancer 1994;30A:1326–36. 10.1016/0959-8049(94)90182-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Carlson LE, Angen M, Cullum J, et al. High levels of untreated distress and fatigue in cancer patients. Br J Cancer 2004;90:2297–304. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Carlson LE, Bultz BD. Benefits of psychosocial oncology care: improved quality of life and medical cost offset. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes 2003;1:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Panzini RG, Mosqueiro BP, Zimpel RR, et al. Quality-Of-Life and spirituality. Int Rev Psychiatry 2017;29:263–82. 10.1080/09540261.2017.1285553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Samuel CA, Mbah OM, Elkins W, et al. Calidad de Vida: a systematic review of quality of life in Latino cancer survivors in the USA. Qual Life Res 2020;29:2615–30. 10.1007/s11136-020-02527-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Aguado Loi CX, Baldwin JA, McDermott RJ, et al. Risk factors associated with increased depressive symptoms among Latinas diagnosed with breast cancer within 5 years of survivorship. Psychooncology 2013;22:2779–88. 10.1002/pon.3357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lee MS, Tyson DM, Gonzalez BD, et al. Anxiety and depression in S panish‐speaking L atina cancer patients prior to starting chemotherapy. Psycho‐oncology 2018;27:333–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Griner D, Smith TB. Culturally adapted mental health intervention: a meta-analytic review. Psychotherapy 2006;43:531. 10.1037/0033-3204.43.4.531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hall GCN, Ibaraki AY, Huang ER, et al. A meta-analysis of cultural adaptations of psychological interventions. Behav Ther 2016;47:993–1014. 10.1016/j.beth.2016.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Benish SG, Quintana S, Wampold BE. Culturally adapted psychotherapy and the legitimacy of myth: a direct-comparison meta-analysis. J Couns Psychol 2011;58:279. 10.1037/a0023626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Smith T, Domenech Rodríguez MM, Bernal G. Culture. Journal of Clinical Psychology – In Session 2011;67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Breitbart W, Rosenfeld B, Gibson C, et al. Meaning-centered group psychotherapy for patients with advanced cancer: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Psychooncology 2010;19:21–8. 10.1002/pon.1556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Villatoro AP, Morales ES, Mays VM. Family culture in mental health help-seeking and utilization in a nationally representative sample of Latinos in the United States: the NLAAS. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 2014;84:353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bernal GE, Domenech Rodríguez MM. Cultural adaptations: tools for evidence-based practice with diverse populations. American Psychological Association, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bernal G, Bonilla J, Bellido C. Ecological validity and cultural sensitivity for outcome research: issues for the cultural adaptation and development of psychosocial treatments with Hispanics. J Abnorm Child Psychol 1995;23:67–82. 10.1007/BF01447045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bernal G, Sáez-Santiago E. Culturally centered psychosocial interventions. J Community Psychol 2006;34:121–32. 10.1002/jcop.20096 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Domenech-Rodríguez M, Wieling E, appropriate Dculturally. Evidence-Based treatments for interventions with ethnic minority populations. Voices of color: First person accounts of ethnic minority therapists 2004;23:313–33. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ashing-Giwa KT. The contextual model of HRQoL: a paradigm for expanding the HRQoL framework. Qual Life Res 2005;14:297–307. 10.1007/s11136-004-0729-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Berg CA, Upchurch R. A developmental-contextual model of couples coping with chronic illness across the adult life span. Psychol Bull 2007;133:920. 10.1037/0033-2909.133.6.920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Costas-Muñiz R, Garduño-Ortega O, González J. Cultural and linguistic adaptation of meaning-centered psychotherapy for Spanish-speaking Latino cancer patients. Meaning-centered psychotherapy in the cancer setting: finding meaning and hope in the face of suffering. 134, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Applebaum AJ, Kulikowski JR, Breitbart W. Meaning-centered psychotherapy for cancer caregivers (MCP-C): rationale and overview. Palliat Support Care 2015;13:1631–41. 10.1017/S1478951515000450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Porter LS, Fish L, Steinhauser K. Themes addressed by couples with advanced cancer during a communication skills training intervention. J Pain Symptom Manage 2018;56:252–8. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2018.04.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Porter LS, Keefe FJ, Baucom DH, et al. A randomized pilot trial of a videoconference couples communication intervention for advanced Gi cancer. Psychooncology 2017;26:1027–35. 10.1002/pon.4121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Czajkowski SM, Powell LH, Adler N, et al. From ideas to efficacy: the orbit model for developing behavioral treatments for chronic diseases. Health Psychol 2015;34:971. 10.1037/hea0000161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zheng M. Conceptualization of cross-sectional mixed methods studies in health science: a methodological review. International Journal of Quantitative and Qualitative Research Methods 2015;3:66–87. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kenny DA, Kashy DA, Cook WL. Dyadic data analysis. Guilford Publications, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Peterman AH, Fitchett G, Brady MJ, et al. Measuring spiritual well-being in people with cancer: the functional assessment of chronic illness therapy--Spiritual Well-being Scale (FACIT-Sp). Ann Behav Med 2002;24:49–58. 10.1207/S15324796ABM2401_06 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.McClain CS, Rosenfeld B, Breitbart W. Effect of spiritual well-being on end-of-life despair in terminally-ill cancer patients. Lancet 2003;361:1603–7. 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13310-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1983;67:361–70. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Carroll BT, Kathol RG, Noyes R, et al. Screening for depression and anxiety in cancer patients using the hospital anxiety and depression scale. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 1993;15:69–74. 10.1016/0163-8343(93)90099-a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mitchell AJ, Meader N, Symonds P. Diagnostic validity of the hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS) in cancer and palliative settings: a meta-analysis. J Affect Disord 2010;126:335–48. 10.1016/j.jad.2010.01.067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dozois DJ, Covin R. The Beck depression Inventory-II (BDI-II), Beck Hopelessness scale (BHS) and Beck scale for suicide ideation (BSS).

- 74.Nissim R, Flora DB, Cribbie RA, et al. Factor structure of the Beck Hopelessness scale in individuals with advanced cancer. Psychooncology 2010;19:255–63. 10.1002/pon.1540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Cella DF, Tulsky DS, Gray G, et al. The functional assessment of cancer therapy scale: development and validation of the general measure. J Clin Oncol 1993;11:570–9. 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.3.570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Moos RH. Family environment scale manual: development, applications, research. Consulting Psychologists Press, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Porter LS, Keefe FJ, Hurwitz H, et al. Disclosure between patients with gastrointestinal cancer and their spouses. Psychooncology 2005;14:1030–42. 10.1002/pon.915 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Porter LS, Keefe FJ, Baucom DH, et al. Partner-assisted emotional disclosure for patients with gastrointestinal cancer: results from a randomized controlled trial. Cancer 2009;115:4326–38. 10.1002/cncr.24578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Manne S, Badr H, Zaider T, et al. Cancer-Related communication, relationship intimacy, and psychological distress among couples coping with localized prostate cancer. J Cancer Surviv 2010;4:74–85. 10.1007/s11764-009-0109-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Figueiredo MI, Fries E, Ingram KM. The role of disclosure patterns and unsupportive social interactions in the well-being of breast cancer patients. Psychooncology 2004;13:96–105. 10.1002/pon.717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Zarit SH, Reever KE, Bach-Peterson J. Relatives of the impaired elderly: correlates of feelings of burden. Gerontologist 1980;20:649–55. 10.1093/geront/20.6.649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Zarit S, Orr NK, Zarit JM. The hidden victims of Alzheimer’s disease: Families under stress. NYU press, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Galindo-Vazquez O, Benjet C, Cruz-Nieto MH, et al. Psychometric properties of the Zarit burden interview in Mexican caregivers of cancer patients. Psychooncology 2015;24:612–5. 10.1002/pon.3686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Watson M, Greer S, Young J, et al. Development of a questionnaire measure of adjustment to cancer: the MAC scale. Psychol Med 1988;18:203–9. 10.1017/s0033291700002026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Gorsuch RL, McPherson SE. Intrinsic/extrinsic measurement: I/E-revised and single-item scales. J Sci Study Relig 1989;28:348–54. 10.2307/1386745 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Rivera-Ledesma A, Zavala-Jiménez S, Montero-López Lena M, et al. Validation of the age universal IE scale in Mexican subjects. Universitas Psychologica 2016;15:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 87.National Comprehensive Cancer Network . Distress management. clinical practice guidelines. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2003;1:344–74. 10.6004/jnccn.2003.0031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Mitchell AJ. Short screening tools for cancer-related distress: a review and diagnostic validity meta-analysis. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2010;8:487–94. 10.6004/jnccn.2010.0035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Friese S. Qualitative data analysis with atlas. Ti. SAGE, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Glaser BG, Holton J. Discovery of grounded theory. strategies for qualitative research. Mill Valley, Calif, USA: Sociology Press, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Schreier M. Ways of doing qualitative content analysis: disentangling terms and terminologies. InForum qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum: qualitative social research, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lewis S. Qualitative inquiry and research design: choosing among five approaches. Health Promot Pract 2015;16:473–5. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Dierckx de Casterlé B, Gastmans C, Bryon E, et al. QUAGOL: a guide for qualitative data analysis. Int J Nurs Stud 2012;49:360–71. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2011.09.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Dey I. Qualitative data analysis: a user friendly guide for social scientists. Routledge, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Downe-Wamboldt B. Content analysis: method, applications, and issues. Health Care Women Int 1992;13:313–21. 10.1080/07399339209516006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Elo S, Kyngäs H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs 2008;62:107–15. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Elo S, Kääriäinen M, Kanste O, et al. Qualitative content analysis: a focus on trustworthiness. SAGE open 2014;4:2158244014522633. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Attride-Stirling J. Thematic networks: an analytic tool for qualitative research. Qualitative Research 2001;1:385–405. 10.1177/146879410100100307 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Anfara VA, Brown KM, Mangione TL. Qualitative analysis on stage: making the research process more public. Educational Researcher 2002;31:28–38. 10.3102/0013189X031007028 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Glaser BG, Strauss AL. Discovery of grounded theory: strategies for qualitative research. Routledge, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Mayring P. Qualitative content analysis. A companion to qualitative research 2004;1:159–76. [Google Scholar]

- 102.Lewis S. Qualitative inquiry and research design: choosing among five approaches. Health Promot Pract 2015;16:473–5. 10.1177/1524839915580941 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.